TL;DR#

Sequential memory, crucial for intelligence, faces challenges like catastrophic forgetting and limited capacity. Existing models struggle with representing and generating multiple valid future scenarios from a single context. This paper introduces Predictive Attractor Models (PAM), addressing these issues.

PAM leverages a biologically-inspired framework using Hebbian plasticity and lateral inhibition to learn sequences online, continuously, and without overwriting previous memories. Its attractor model enables stochastic sampling of multiple future possibilities. PAM demonstrates superior performance in terms of capacity, noise robustness, and avoiding catastrophic forgetting compared to existing methods, establishing it as a significant advancement in sequential memory modeling.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in artificial intelligence, neuroscience, and cognitive science as it proposes a novel, biologically plausible model for sequential memory. The model addresses significant challenges in existing sequential memory models, such as catastrophic forgetting and limited capacity. The proposed approach paves the way for developing more efficient and robust AI systems capable of learning and remembering complex sequences in a continuous manner.

Visual Insights#

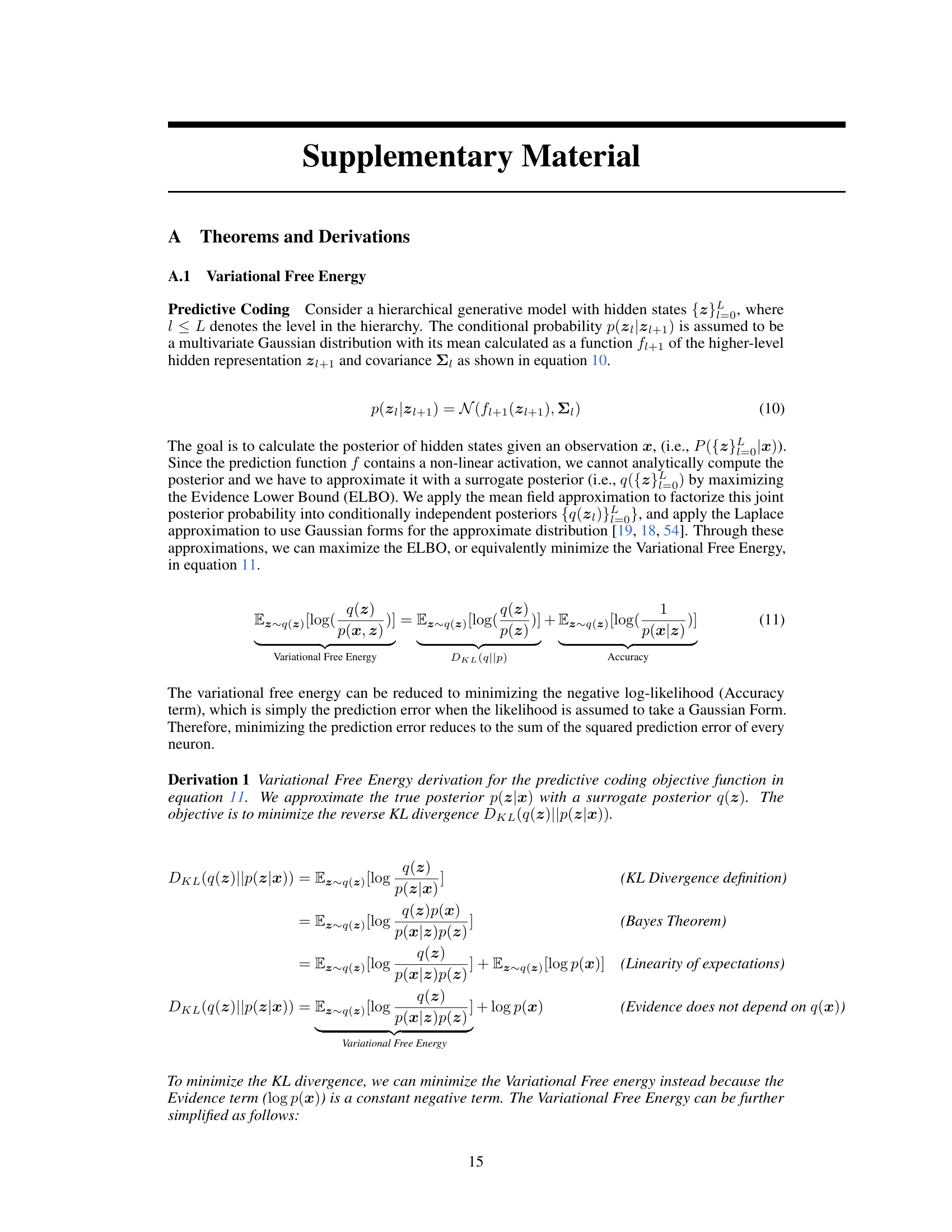

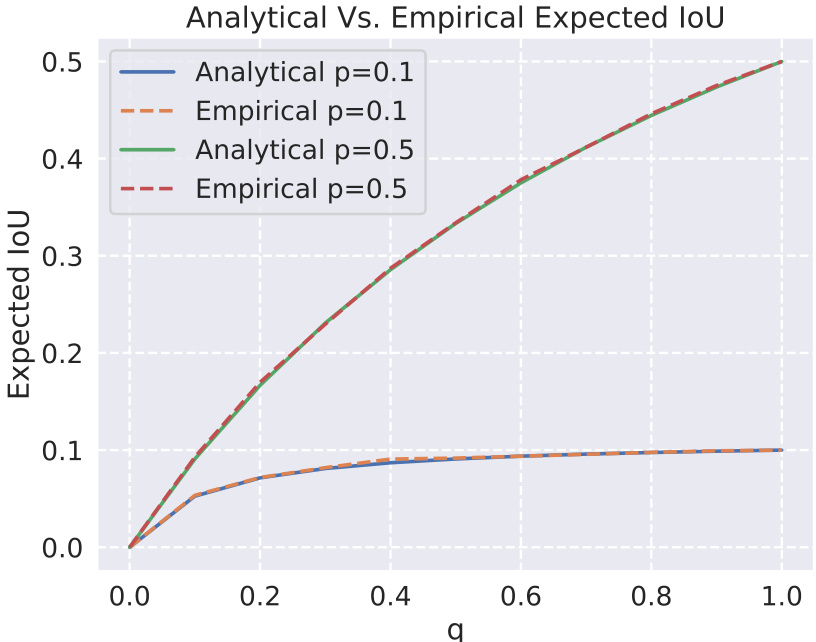

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed Predictive Attractor Model (PAM) as a dynamic system using a Bayesian probabilistic graphical model, specifically a State Space Model (SSM). The left panel shows the SSM as a first-order Markov chain, where latent states (z) transition according to function f and emit observations (x) through function g. The right panel details the Gaussian assumptions for prior and posterior latent states, highlighting the use of a Mixture of Gaussian model to represent the conditional probability of multiple valid future possibilities (p(x|z)) from a single latent state. This illustrates PAM’s ability to handle multiple future possibilities stemming from the same context.

read the caption

Figure 1: State Space Model. (Left): Dynamical system represented by first-order Markov chain of latent states z with transition function f and an emission function g which projects to the observation states x. (Right): Gaussian form assumptions for the prior zˆ and posterior z latent states, and the Mixture of Gaussian model representing the conditional probability of multiple possibilities p(x|z)

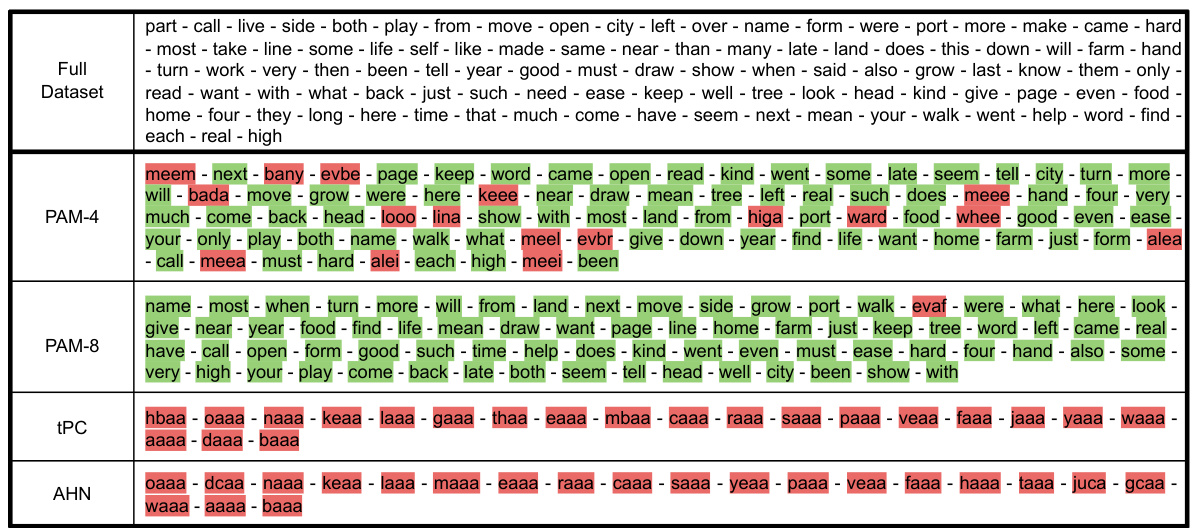

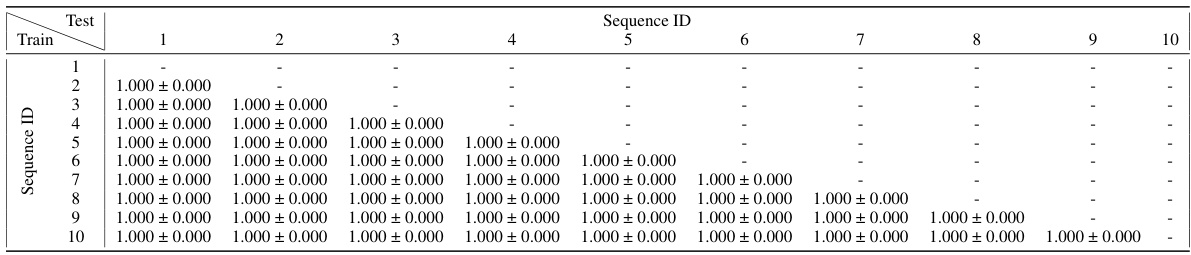

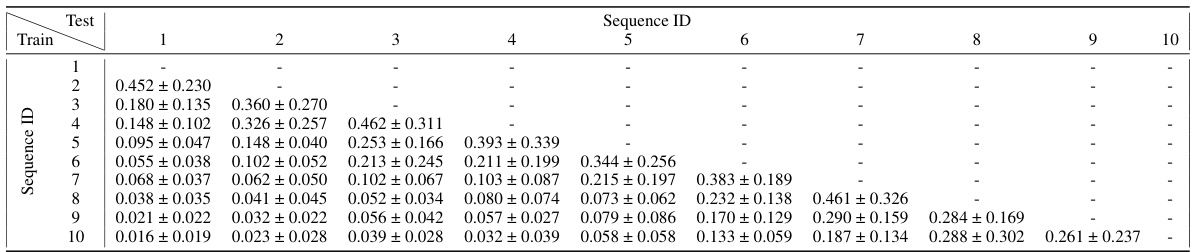

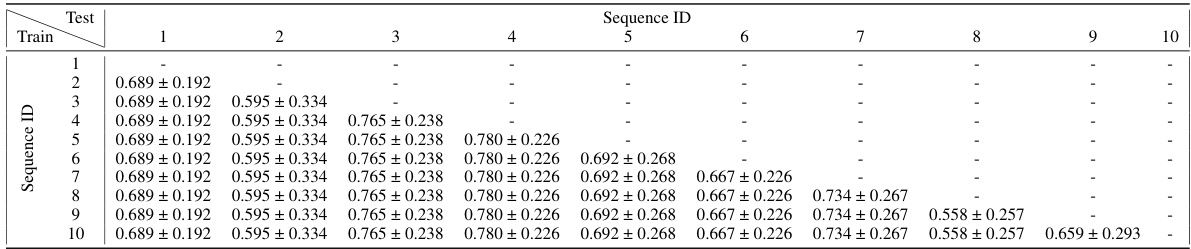

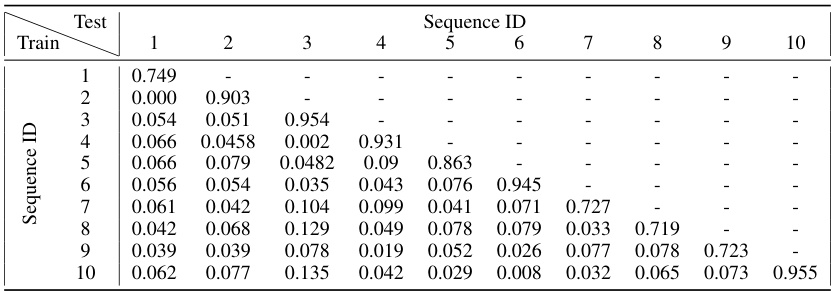

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) with 1 context neuron (Nk=1). Ten sequences were learned sequentially, and after each new sequence was learned, the model’s performance on previously learned sequences was measured using the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the IoU for each previously learned sequence after each new sequence was learned. The Backward Transfer (BWT) metric, which is the average IoU across all previously learned sequences, is also provided.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

In-depth insights#

Predictive Attractor#

Predictive attractor models offer a novel approach to sequential memory by integrating predictive coding with attractor network dynamics. The predictive element allows the model to anticipate future inputs based on learned temporal associations, while the attractor dynamics enable the stable representation and recall of multiple future possibilities stemming from a single context. This combination addresses limitations of existing methods, such as catastrophic forgetting and the inability to generate diverse, valid predictions. The model’s reliance on local computations and Hebbian learning rules enhances its biological plausibility, while its streaming architecture promotes efficiency and scalability. However, challenges remain, such as handling very high-dimensional inputs and establishing a clear theoretical understanding of the model’s capacity and generalization capabilities. Further research is needed to fully explore its potential and address these limitations.

Hebbian Learning#

Hebbian learning, a cornerstone of neural network research, posits that neurons that fire together wire together. This principle elegantly explains associative learning, where the simultaneous activation of two neurons strengthens their synaptic connection, increasing the likelihood of future co-activation. In the context of sequential memory models, Hebbian learning provides a biologically plausible mechanism for learning temporal associations. The repeated co-occurrence of neuronal activations representing consecutive events in a sequence strengthens their connections, thus encoding the temporal order. However, naive Hebbian learning suffers from catastrophic interference, where new learning overwrites existing memories. Therefore, sophisticated modifications of Hebbian rules are necessary, often involving mechanisms like long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) to fine-tune synaptic weights and prevent overwriting. The challenge in designing effective sequential memory models lies in balancing the need for robust associative learning with the avoidance of catastrophic forgetting. Predictive attractor models, in particular, often employ variations of Hebbian plasticity to learn temporal dependencies in a biologically plausible manner. Combining Hebbian rules with mechanisms for context-dependent learning, lateral inhibition, and noise tolerance is crucial for creating effective sequential memory models. This demonstrates how Hebbian learning, although a fundamental principle, requires careful refinement for practical applications.

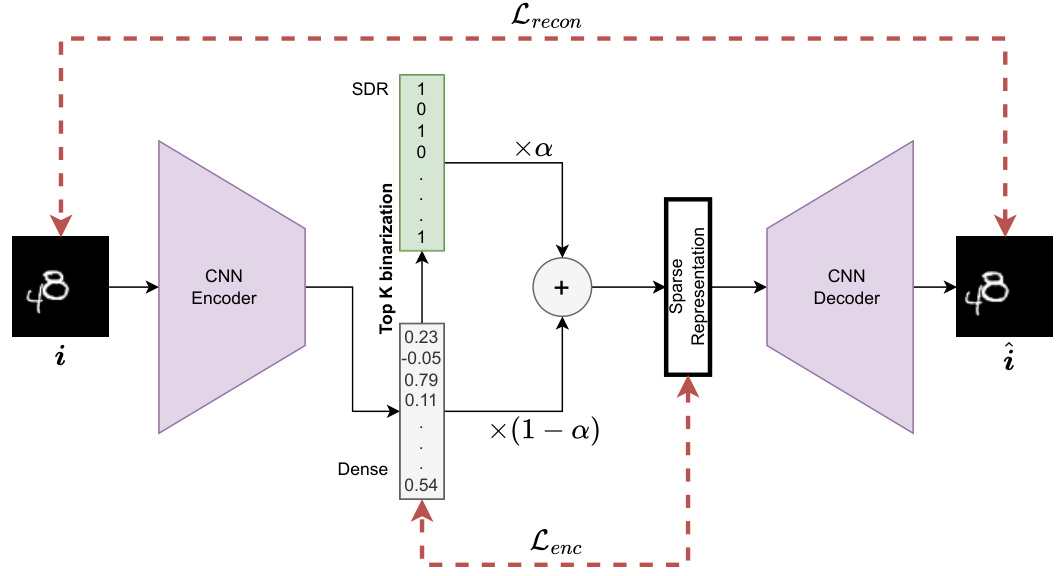

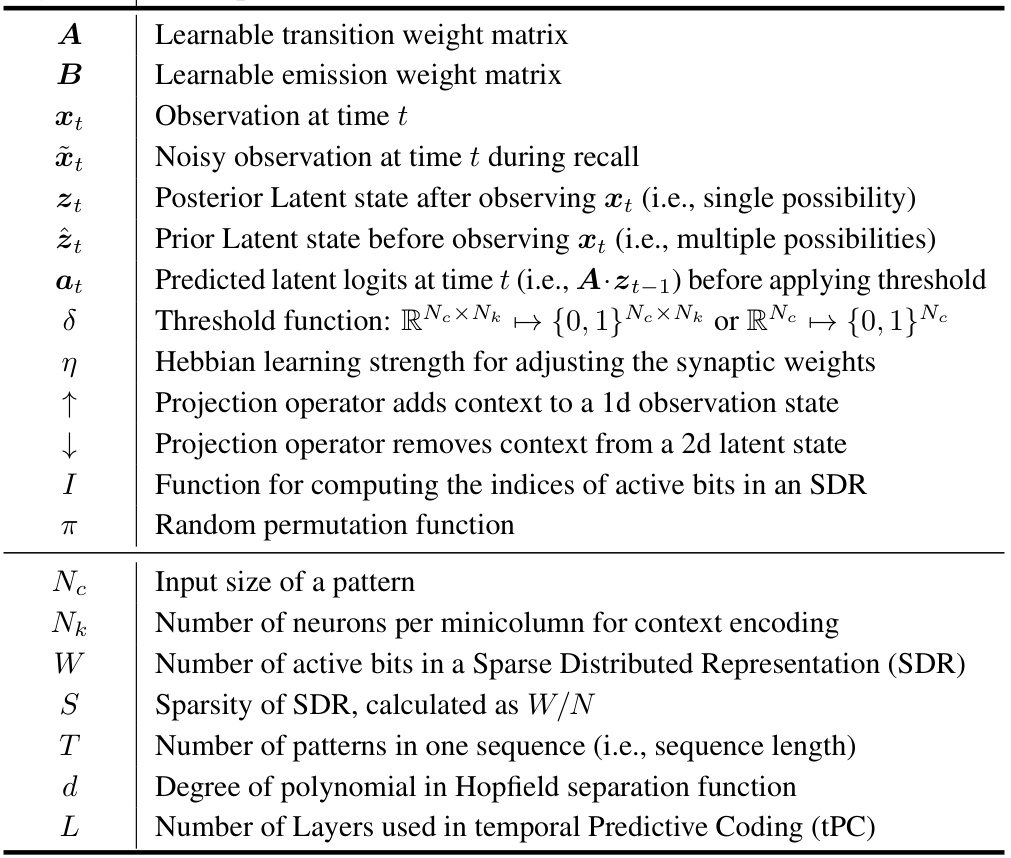

SDR Encoding#

Sparse Distributed Representations (SDRs) are a cornerstone of the Predictive Attractor Models (PAMs) presented in this research. SDRs offer a biologically plausible way to encode information by using high-dimensional, sparse binary vectors. Each SDR only activates a small subset of its neurons (typically 5%), making them computationally efficient and robust to noise. This sparsity is crucial; it prevents catastrophic interference between memories by allowing unique representations for each data point even within a context. By representing context as orthogonal dimensions within the SDR, PAM avoids the catastrophic forgetting problem, a major hurdle for many sequential memory models. Furthermore, the union of SDRs allows PAM to represent multiple valid future possibilities arising from the same context, which is a novel capability of this system. The ability of SDRs to capture high-order Markov dependencies between inputs is another key feature that enables the system’s accurate and efficient sequence prediction.

Continual Learning#

Continual learning, the ability of a model to learn new information without forgetting previously acquired knowledge, is a crucial aspect of artificial intelligence. This paper tackles the challenge of continual learning in the context of sequential memory, a problem where existing methods often suffer from catastrophic forgetting. The proposed solution, Predictive Attractor Models (PAM), addresses catastrophic forgetting by uniquely representing past context through lateral inhibition, preventing new memories from overwriting old ones. This biologically plausible approach uses Hebbian plasticity rules and local computations, enhancing computational efficiency. PAM’s capacity to generate multiple future possibilities from a single context, a feature often lacking in other sequential memory models, is another key contribution. Online learning is incorporated, allowing the model to learn continuously from a stream of data. These features are validated through a series of experiments demonstrating PAM’s superior performance on tasks involving sequence capacity, noise tolerance, and backward transfer, metrics for evaluating catastrophic forgetting. The model’s success highlights the importance of incorporating biologically inspired mechanisms into the design of continual learning systems for improved efficiency and robustness.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of a research paper on Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) would naturally focus on extending the model’s capabilities and addressing its limitations. Expanding PAM to handle hierarchical sensory processing is crucial; this would involve creating a layered architecture where higher-level modules integrate information from lower levels, mirroring the brain’s hierarchical organization. Incorporating higher-order sparse predictive models would enhance the model’s ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies, a significant challenge in sequential memory. Addressing the current limitation of requiring binary sparse representations could involve exploring alternatives that can directly handle rich, high-dimensional data like images or text. Furthermore, future work could explore different ways of optimizing the model’s learning process, potentially using biologically more plausible learning rules. Investigating the model’s robustness to different types of noise is important, as real-world data is inherently noisy. Finally, extensive comparative evaluations against state-of-the-art models on diverse and challenging datasets would solidify the model’s potential and highlight its advantages.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the state space model representation of Predictive Attractor Models (PAM). The left panel shows a graphical model of a first-order Markov chain of latent states with transition and emission functions. The right panel shows the assumed Gaussian distributions for prior and posterior latent states, and uses a Mixture of Gaussians to model the multiple possible observations given a latent state.

read the caption

Figure 1: State Space Model. (Left): Dynamical system represented by first-order Markov chain of latent states z with transition function f and an emission function g which projects to the observation states x. (Right): Gaussian form assumptions for the prior z and posterior z latent states, and the Mixture of Gaussian model representing the conditional probability of multiple possibilities p(x|z)

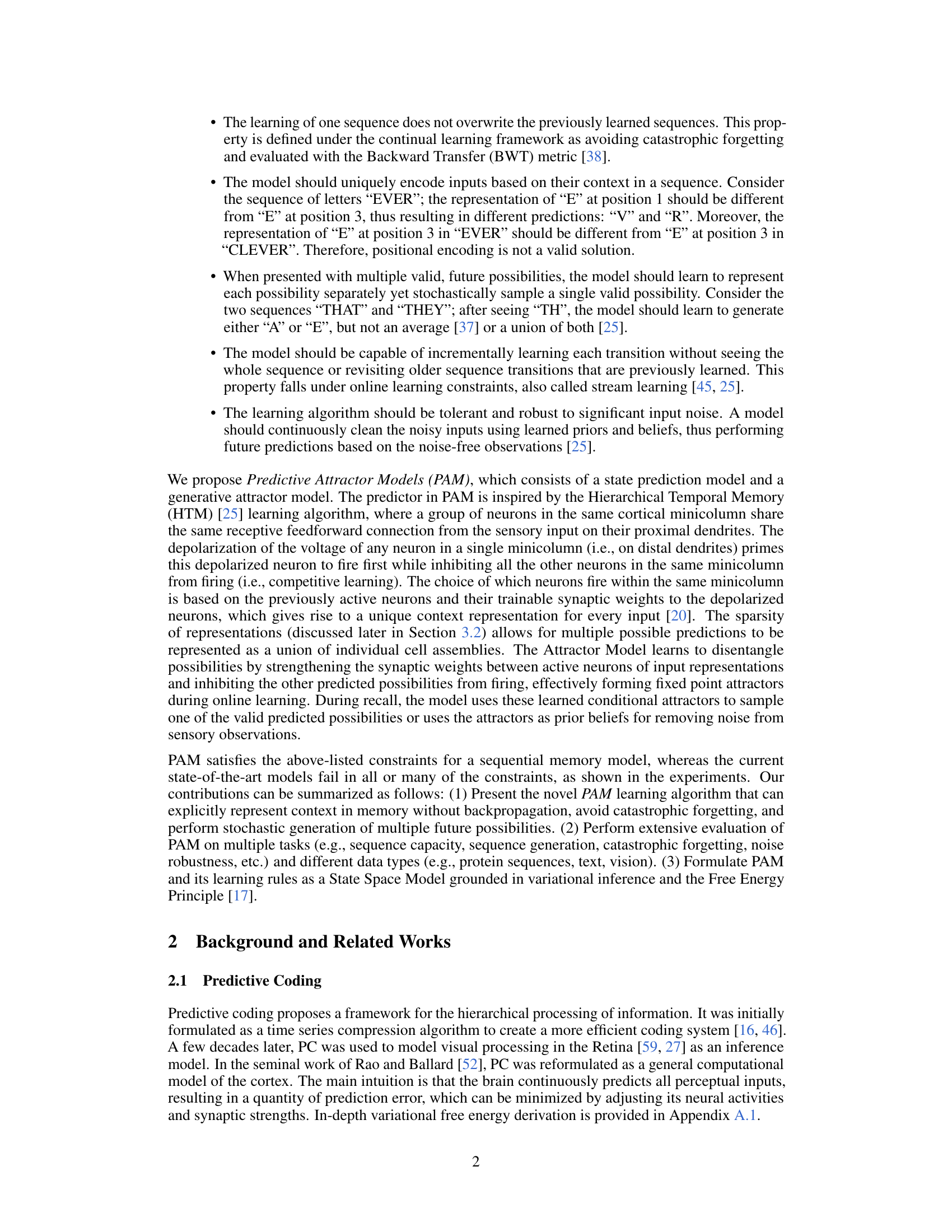

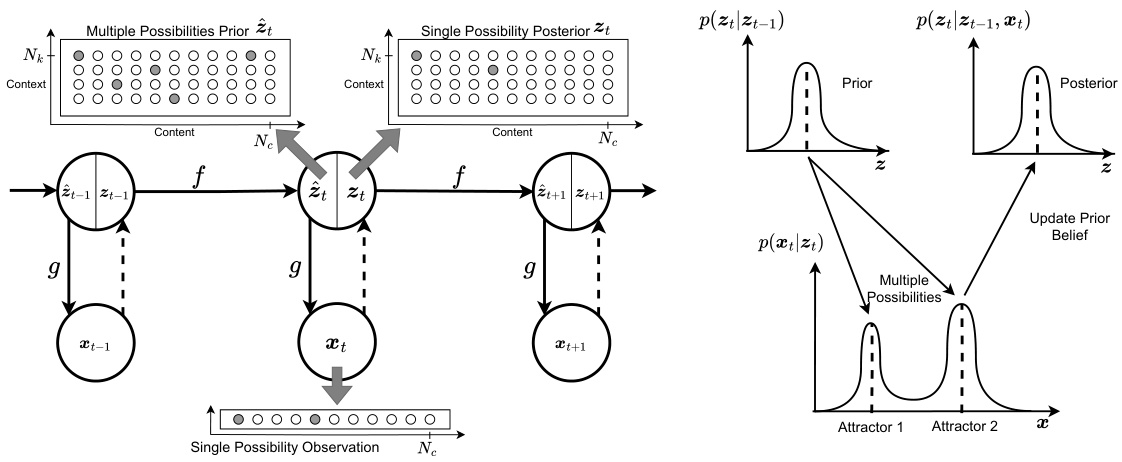

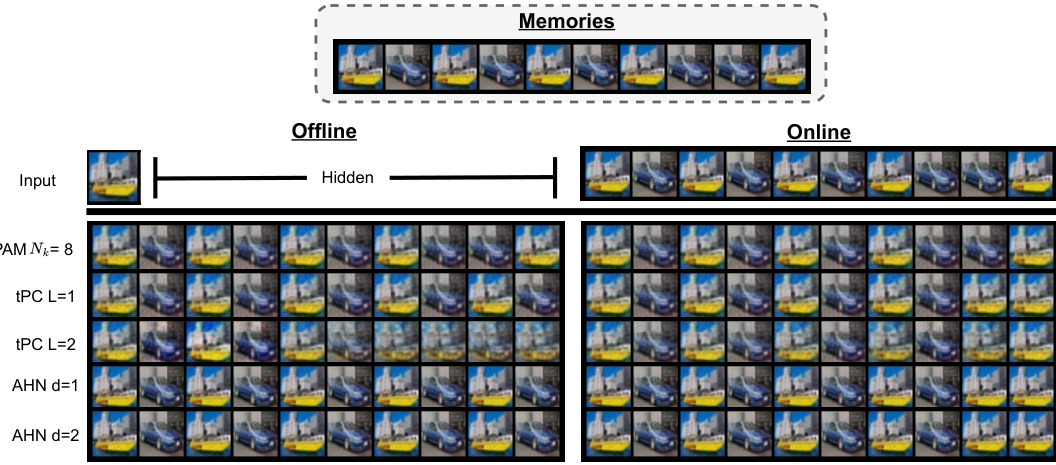

🔼 This figure illustrates the two sequence generation methods used in Predictive Attractor Models (PAM): offline and online generation. Offline generation starts with an initial input and samples a single possibility (attractor) from the set of predicted possibilities to generate the sequence. Online generation receives a noisy input and uses learned prior beliefs to clean the noise before generating the next state. The Markov Blanket concept highlights the separation between the model’s internal state and the external, observable states.

read the caption

Figure 2: Sequence Generation. (Left): Offline generation by sampling a single possibility (i.e., attractor point) from a union of predicted possibilities. (Right): Online generation by removing noise from an observation using the prior beliefs about the observed state. Markov Blanket separates the agent's latent variables from the world's observable states.

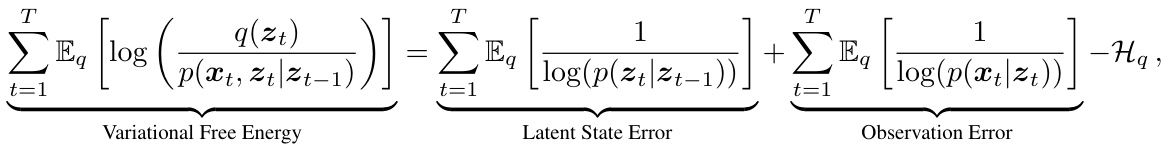

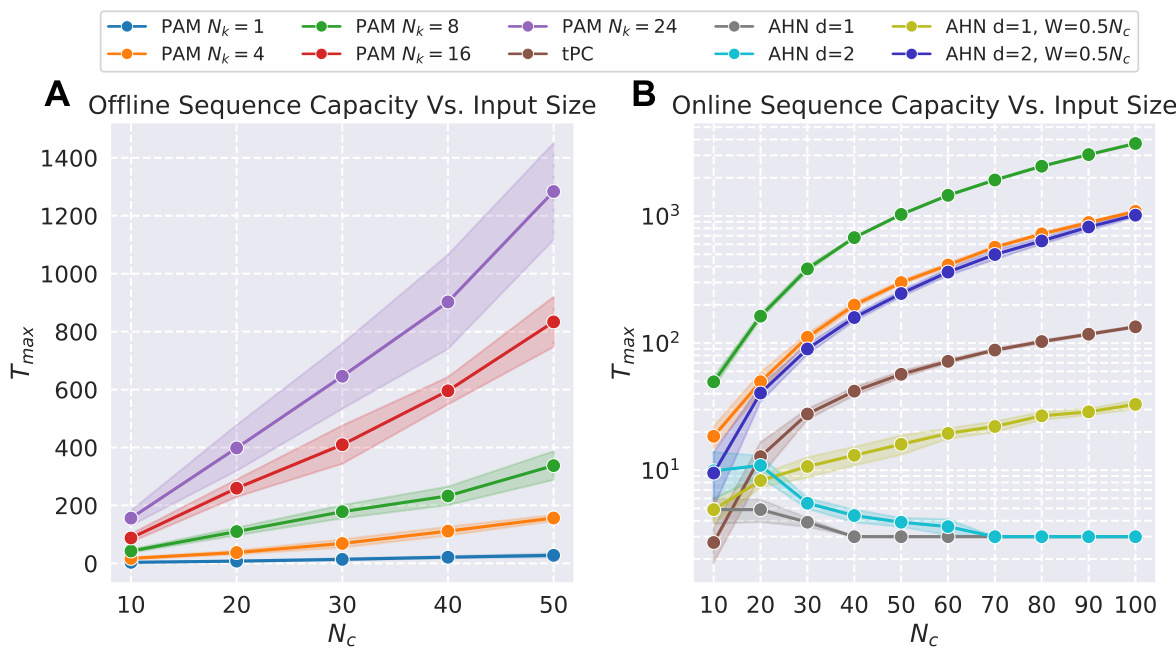

🔼 This figure presents the quantitative and qualitative results of the experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) against other state-of-the-art models in terms of sequence capacity, noise robustness, and time efficiency. The quantitative results include graphs showing the relationship between sequence length and input size, correlation and capacity, noise level and IoU, and time versus sequence length. The qualitative results showcase the performance of the models on a highly correlated CIFAR sequence in both offline and online settings, demonstrating the ability of PAM to accurately predict future possibilities based on the given context, while others struggled to do so.

read the caption

Figure 3: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure presents a comprehensive evaluation of the Predictive Attractor Model (PAM) and other state-of-the-art models across several key aspects. Subfigures (A) and (B) show quantitative results on offline sequence capacity, demonstrating the effects of input size and sequence correlation. Subfigure (C) displays the noise robustness of the models. Subfigure (D) illustrates the learning and recall time efficiency. Subfigures (E) and (F) provide qualitative comparisons using CIFAR sequences to visually showcase the models’ offline and online prediction capabilities, particularly highlighting PAM’s ability to handle long and correlated sequences.

read the caption

Figure 3: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 The figure presents quantitative results of experiments on offline sequence capacity, noise robustness, and the time taken for sequence learning and recall using the PAM model and other existing models. It shows four plots (A-D): sequence capacity vs. input size, capacity vs. correlation, IoU vs. noise, and time vs. sequence length. Additionally, it includes qualitative results comparing PAM and the other methods for highly correlated CIFAR sequences in offline and online settings (E and F). The standard deviation and mean of 10 trials are displayed for all plots.

read the caption

Figure 5: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed Predictive Attractor Model (PAM) as a dynamic Bayesian network. The left panel shows the overall architecture as a first-order Markov chain with latent states (z) and observations (x), connected by transition (f) and emission (g) functions, respectively. The right panel zooms in on the representation of the latent states using Gaussian distributions, highlighting the representation of multiple future possibilities via a mixture model.

read the caption

Figure 1: State Space Model. (Left): Dynamical system represented by first-order Markov chain of latent states z with transition function f and an emission function g which projects to the observation states x. (Right): Gaussian form assumptions for the prior 2 and posterior z latent states, and the Mixture of Gaussian model representing the conditional probability of multiple possibilities p(x|z)

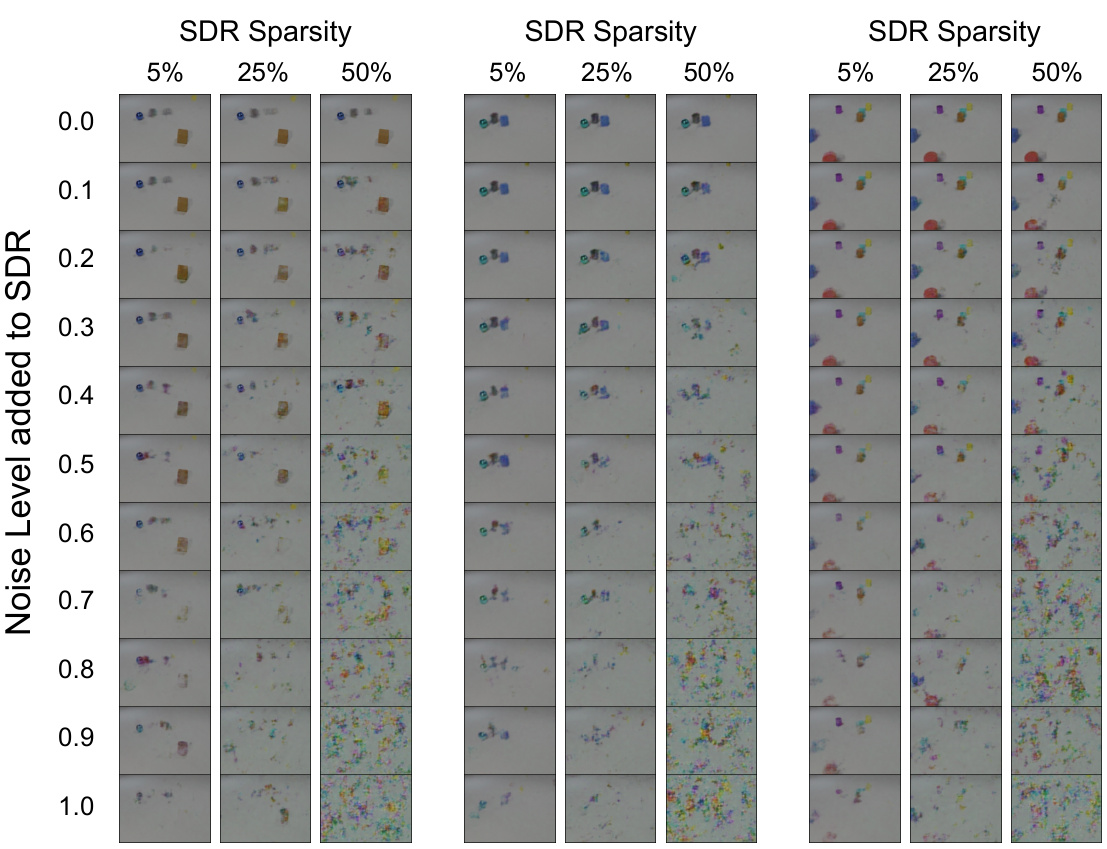

🔼 This figure shows the reconstruction results from the SDR autoencoder for three different datasets: Moving MNIST, CLEVRER, and CIFAR. For each dataset, sample images and their corresponding SDR reconstructions are displayed. The autoencoder is used to convert images into sparse distributed representations (SDRs) and back again. This demonstrates the autoencoder’s ability to effectively capture and reconstruct the visual information present in the images using the SDR format.

read the caption

Figure 7: Examples of Autoencoder reconstructions from SDRs for all three datasets

🔼 This figure presents quantitative and qualitative results evaluating Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) performance against other models on tasks related to offline and online sequence memory. The quantitative analyses assess sequence capacity in relation to input size and correlation, noise robustness, and training/recall time. Qualitative results, using a highly correlated CIFAR sequence, illustrate the models’ performance in offline and online settings. Error bars represent the standard deviation across 10 trials.

read the caption

Figure 3: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two sequence generation methods used in the paper. Offline generation involves sampling a single possibility from the union of predicted possibilities. This is represented on the left side, showcasing the model sampling from multiple attractor basins. Online generation uses noisy observations, removing noise based on prior beliefs about the observed state. This is represented on the right side, showcasing the model utilizing lateral inhibition to achieve this noise reduction. The Markov Blanket, a key concept explained in the paper, is also shown to separate the agent’s latent variables from external observations.

read the caption

Figure 2: Sequence Generation. (Left): Offline generation by sampling a single possibility (i.e., attractor point) from a union of predicted possibilities. (Right): Online generation by removing noise from an observation using the prior beliefs about the observed state. Markov Blanket separates the agent's latent variables from the world's observable states.

🔼 This figure presents the quantitative and qualitative results of the experiments on offline sequence capacity, noise robustness, and time efficiency of the proposed Predictive Attractor Models (PAM). The quantitative results include plots comparing PAM’s performance against other models across different conditions, such as input size, correlation, noise level, and sequence length. The qualitative results showcase the ability of PAM to handle highly correlated sequences by showing the results on a CIFAR sequence in both offline and online settings. The figure highlights PAM’s ability to generate accurate predictions even with noisy inputs, and also emphasizes its efficiency compared to other methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

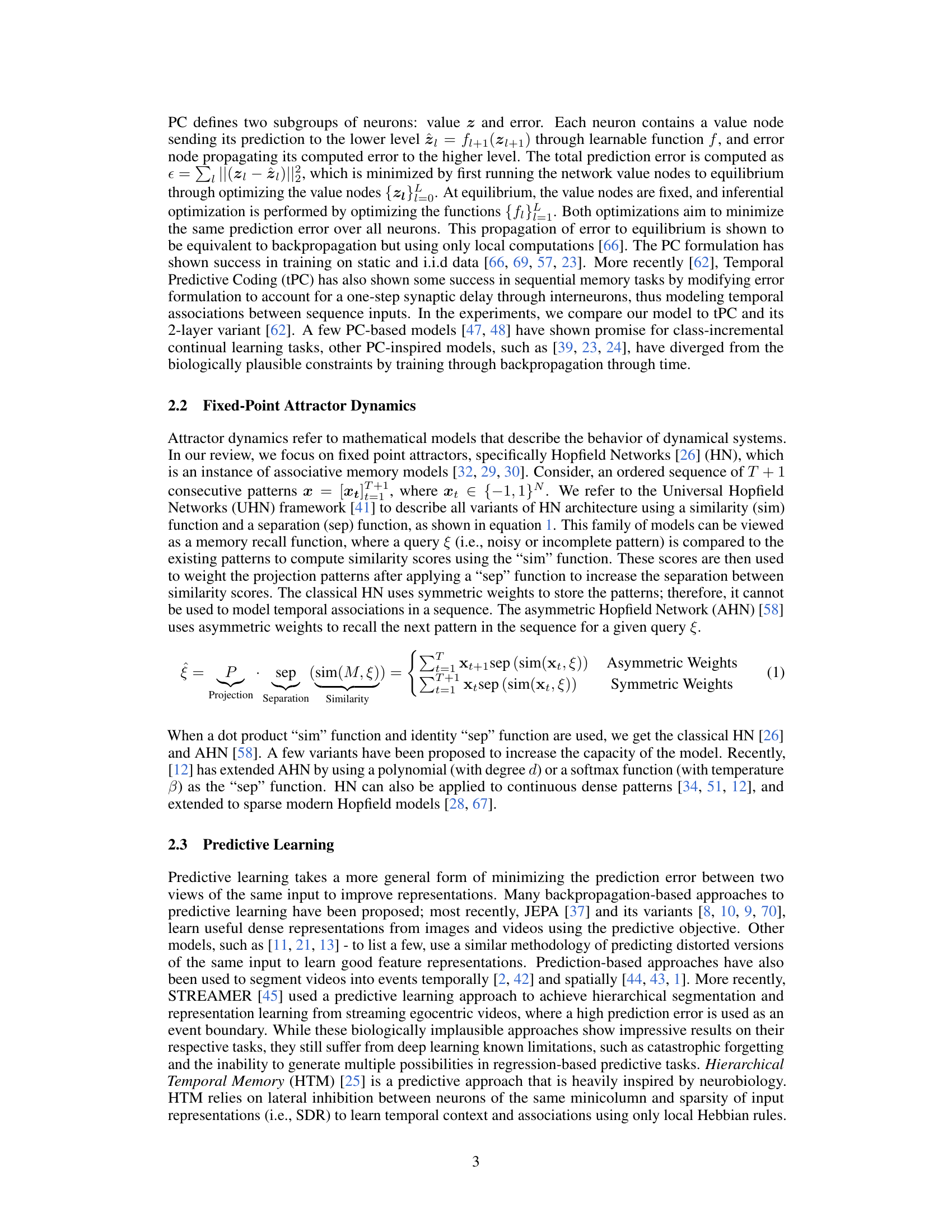

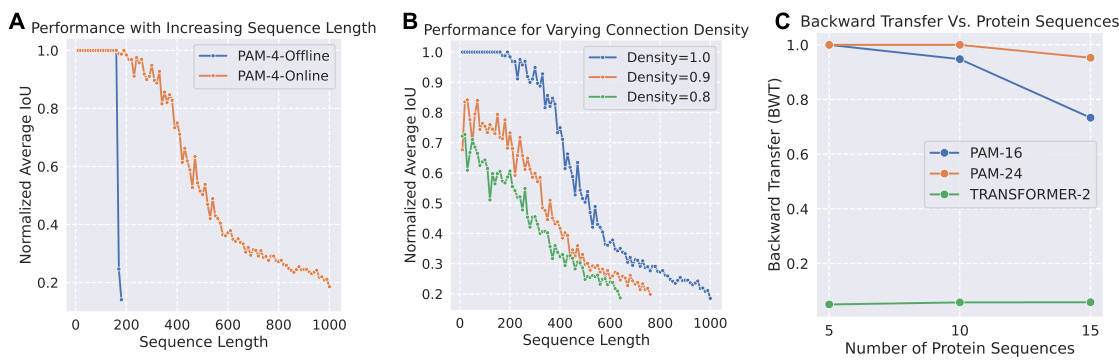

🔼 This figure presents qualitative and quantitative results of the Predictive Attractor Model (PAM) and other models on various sequence tasks. Panel (A) and (B) show the Backward Transfer (BWT) metric which evaluates catastrophic forgetting on synthetic and protein sequences, respectively. (C) and (D) demonstrate the ability of the models to generate multiple future possibilities from text sequences. Panel (E) displays noise robustness on the CLEVRER sequence. Finally, (F) illustrates the catastrophic forgetting performance on the Moving MNIST dataset.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative results on (A) synthetic and (B) protein sequences backward transfer, and (C-D) multiple possibilities generation on text datasets. Qualitative results on (E) noise robustness on CLEVRER sequence, and (F) catastrophic forgetting on Moving MNIST dataset. highlights the first frame with significant error. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two different modes of sequence generation used in the Predictive Attractor Model (PAM). The left panel shows offline generation, where a single possible future state is sampled from the set of all possible future states predicted by the model. The right panel depicts online generation, where a noisy observation is refined using prior knowledge to generate a more accurate prediction. The Markov Blanket highlights the separation between the model’s internal state and the external observations.

read the caption

Figure 2: Sequence Generation. (Left): Offline generation by sampling a single possibility (i.e., attractor point) from a union of predicted possibilities. (Right): Online generation by removing noise from an observation using the prior beliefs about the observed state. Markov Blanket separates the agent's latent variables from the world's observable states.

🔼 This figure presents quantitative and qualitative experimental results. The quantitative results (A-D) show the performance of PAM compared to other models in terms of offline sequence capacity varying input size and correlation, noise robustness, and learning/recall time. The qualitative results (E-F) illustrate the ability of PAM to handle highly correlated CIFAR image sequences in offline and online settings, demonstrating its superior performance compared to alternative models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure shows the qualitative and quantitative results of the experiments conducted to evaluate different aspects of the proposed PAM model. Specifically, it demonstrates the model’s performance regarding (A) avoiding catastrophic forgetting on synthetic and protein sequences, (B) generating multiple future possibilities based on a given context, (C) its robustness to noisy inputs, and (D) handling catastrophic forgetting when learning multiple sequences. The results displayed include the backward transfer metric, IoU (Intersection over Union) score, and mean squared error, along with visual examples to illustrate the model’s behavior and comparison with other models in specific tasks such as recalling sequences.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative results on (A) synthetic and (B) protein sequences backward transfer, and (C-D) multiple possibilities generation on text datasets. Qualitative results on (E) noise robustness on CLEVRER sequence, and (F) catastrophic forgetting on Moving MNIST dataset. highlights the first frame with significant error. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure presents the quantitative and qualitative results of experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed Predictive Attractor Model (PAM) and compare it with other state-of-the-art methods. The quantitative results include offline sequence capacity (A,B), noise robustness (C), and the time required for sequence learning and recall (D). The qualitative results show the performance of PAM and other models on a highly correlated CIFAR image sequence in offline (E) and online (F) settings.

read the caption

Figure 3: Quantitative results on (A-B) Offline sequence capacity, (C) Noise robustness, and (D) Time of sequence learning and recall. Qualitative results on highly correlated CIFAR sequence in (E) offline and (F) online settings. The mean and standard deviation of 10 trials are reported for all plots.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two different sequence generation methods used in the Predictive Attractor Models (PAM): offline and online generation. In offline generation, the model samples a single possibility from a set of possibilities to generate the whole sequence (left panel). In online generation, the model uses noisy observations and its prior beliefs to remove noise and generate the sequence step-by-step (right panel). Markov blanket, a key concept in Bayesian networks, is also shown, separating the model’s internal states from external, observable states.

read the caption

Figure 2: Sequence Generation. (Left): Offline generation by sampling a single possibility (i.e., attractor point) from a union of predicted possibilities. (Right): Online generation by removing noise from an observation using the prior beliefs about the observed state. Markov Blanket separates the agent's latent variables from the world's observable states.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) with a context size of 1. The experiment involved training the model on 10 sequences sequentially. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU) for each previously learned sequence after each new sequence is learned. The Backward Transfer (BWT) metric, which is the average of all IoU values, quantifies the model’s ability to retain previously learned knowledge while learning new sequences. The low BWT values indicate that the model suffers from catastrophic forgetting.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM). Ten sequences were used, and the model’s ability to retain previously learned sequences after learning new ones was evaluated using the Backward Transfer (BWT) metric. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU) for each previously learned sequence, after training on a new sequence. The BWT metric, which is the average of these IoUs, quantifies the extent of catastrophic forgetting.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) with 1 context neuron (Nk=1). Ten sequences were learned sequentially, and after each new sequence was learned, the model’s performance on previously learned sequences was measured using the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the IoU for each previously learned sequence after each new sequence was added, allowing assessment of how well the model retained older memories. The Backward Transfer metric, which is the average of all these IoUs, summarizes the overall catastrophic forgetting performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) with 1 context neuron (Nk=1). Ten sequences were learned sequentially, and after each new sequence was learned, the model’s performance on previously learned sequences was measured using the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the IoU for each previously learned sequence after each new sequence was trained. The ‘Backward Transfer’ metric, which is the average of all the IoUs, provides a summary measure of catastrophic forgetting.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) with 1 context neuron (Nk=1). Ten sequences were learned sequentially, and after each new sequence was learned, the model’s performance on the previously learned sequences was evaluated using the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the IoU for each previously learned sequence after each new sequence was learned. The Backward Transfer (BWT) metric, which is the average of all the IoU values in the lower triangle of the table, summarizes the overall performance of the model in avoiding catastrophic forgetting.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastrophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM). It shows the mean and standard deviation of the Intersection over Union (IoU) for 10 sequences, assessing how well the model retains previously learned sequences after learning new ones. The Backward Transfer (BWT) metric, which is the average of all the IoU values, measures the overall catastrophic forgetting performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

🔼 This table presents the results of a catastrophic forgetting experiment using Predictive Attractor Models (PAM) with 1 context neuron (Nk=1). Ten sequences were learned sequentially, and after each new sequence was learned, the model’s performance on the previously learned sequences was measured using the normalized Intersection over Union (IoU). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the IoU for each previously learned sequence after each new sequence was learned. The ‘Backward Transfer’ metric is the average of all these IoU values, providing a single measure of how well the model retained its knowledge of past sequences after learning new ones.

read the caption

Table 2: Catastrophic forgetting experiment results on 10 sequences for PAM with Nk = 1. The table shows the mean normalized IoU and standard deviation of previous learned sequences after training on new sequences. The Backward Transfer metric is the average of all the shown numbers. Results are averaged over 10 trials.

Full paper#