↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

This research investigated the effectiveness of using active learning to improve human abilities in validating autonomous systems using formal specifications, particularly Signal Temporal Logic (STL). The study revealed a critical gap: despite the common belief that formal methods enhance human understanding, empirical results demonstrated that humans struggle to accurately validate even simple robot behaviors using STL, with overall accuracy around 65%. This emphasizes the need for user-centered design of formal methods for improved human interpretability in autonomous systems.

The research employed a novel game-based platform (ManeuverGame) to assess the impact of different active learning approaches on validation accuracy. The experiment compared active learning with and without feedback. Results revealed no statistically significant difference in accuracy across the various active learning approaches. This finding challenges the common belief that active learning significantly improves human interpretability and provides valuable insights into the challenges of human-in-the-loop validation of autonomous systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common assumption that formal methods inherently improve human interpretability in autonomous systems, a critical issue for the safe and reliable deployment of AI. It highlights the need for further research to bridge the gap between formal specifications and human understanding, potentially leading to improved system validation techniques and more human-centered AI design. The findings underscore the need for more nuanced evaluation methods and could influence the development of more effective tools and processes for ensuring that humans can validate the behavior of autonomous systems.

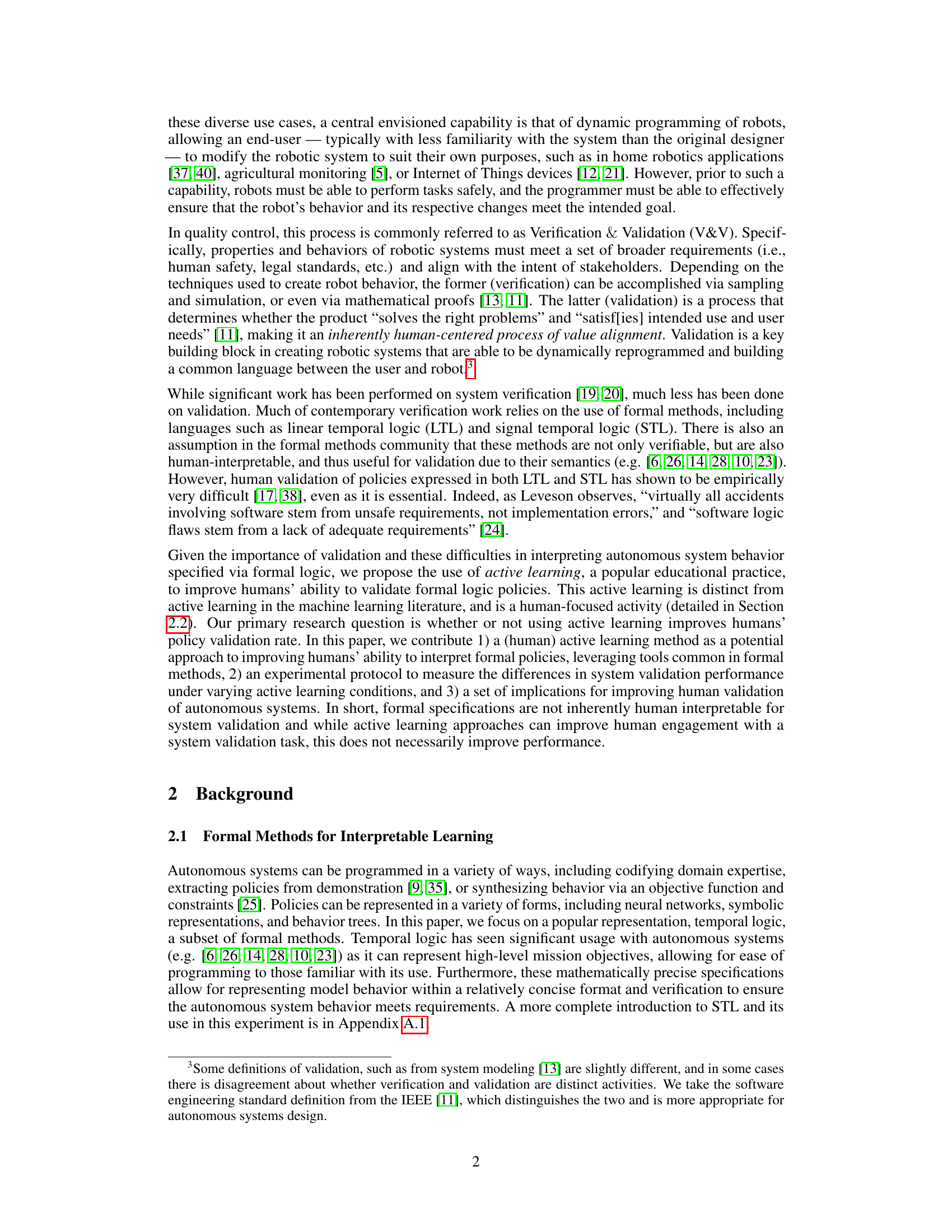

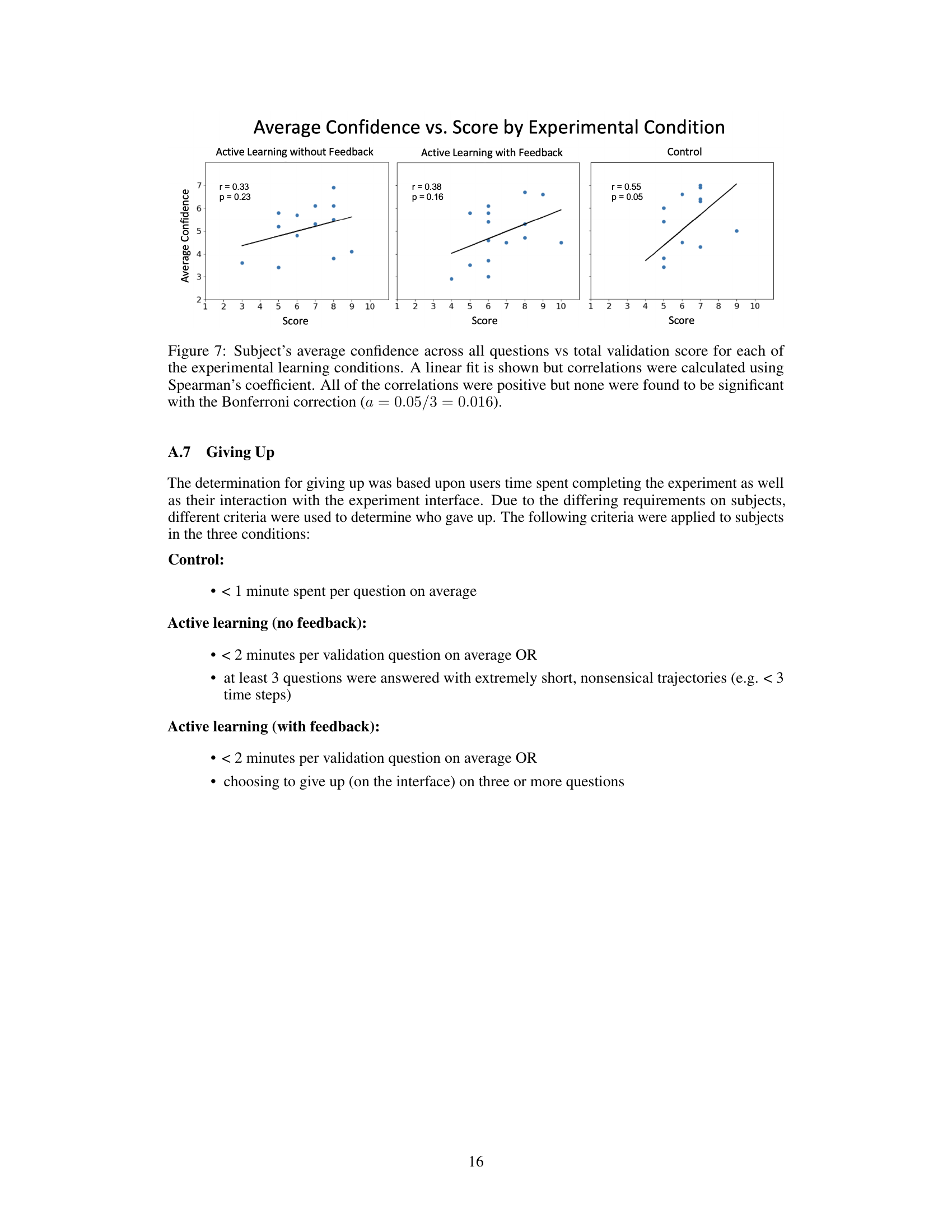

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates how Bloom’s taxonomy of learning is applied to the ManeuverGame experiment. It shows how the process of understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating specifications within the game’s context involves different cognitive levels and leads to refining understanding of policies by iterating through the process multiple times.

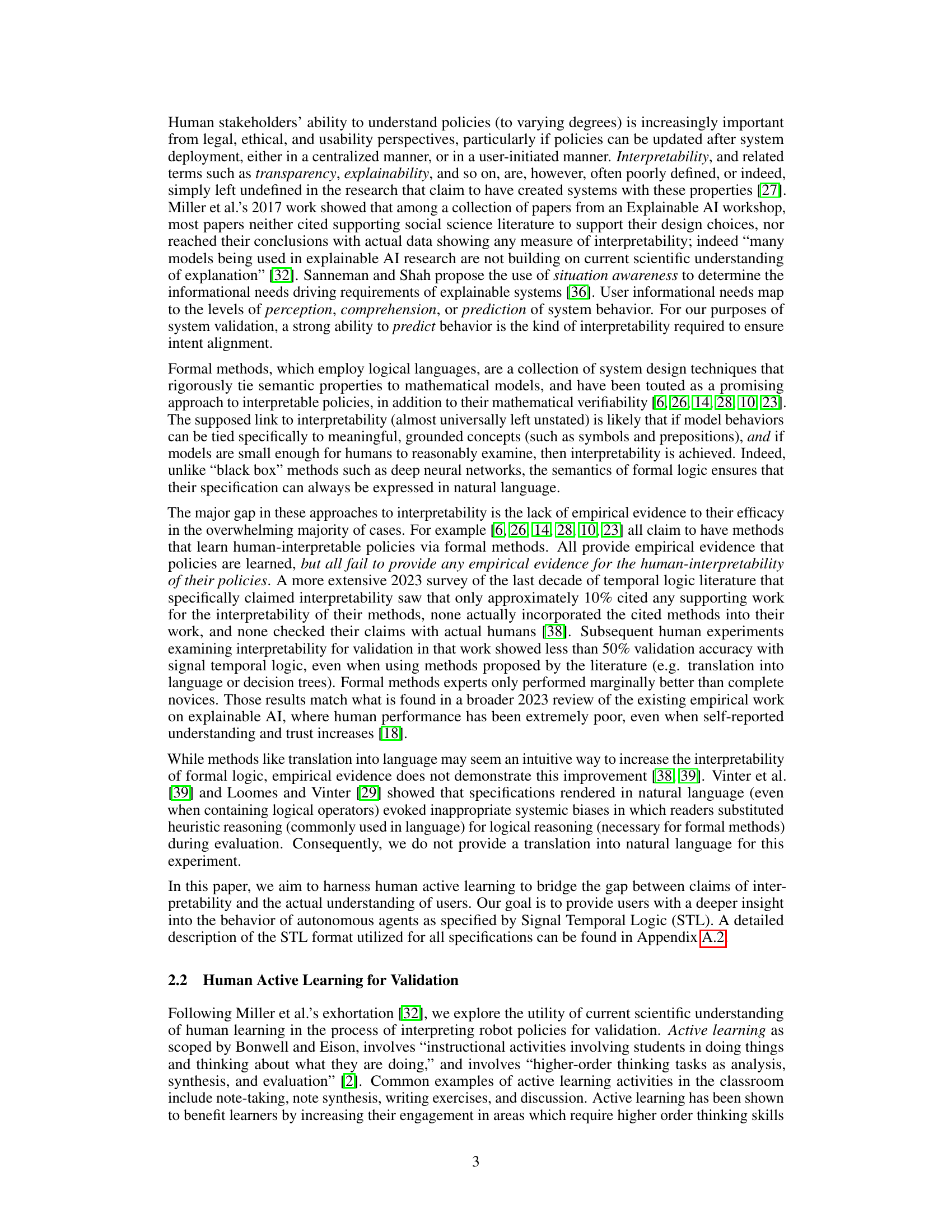

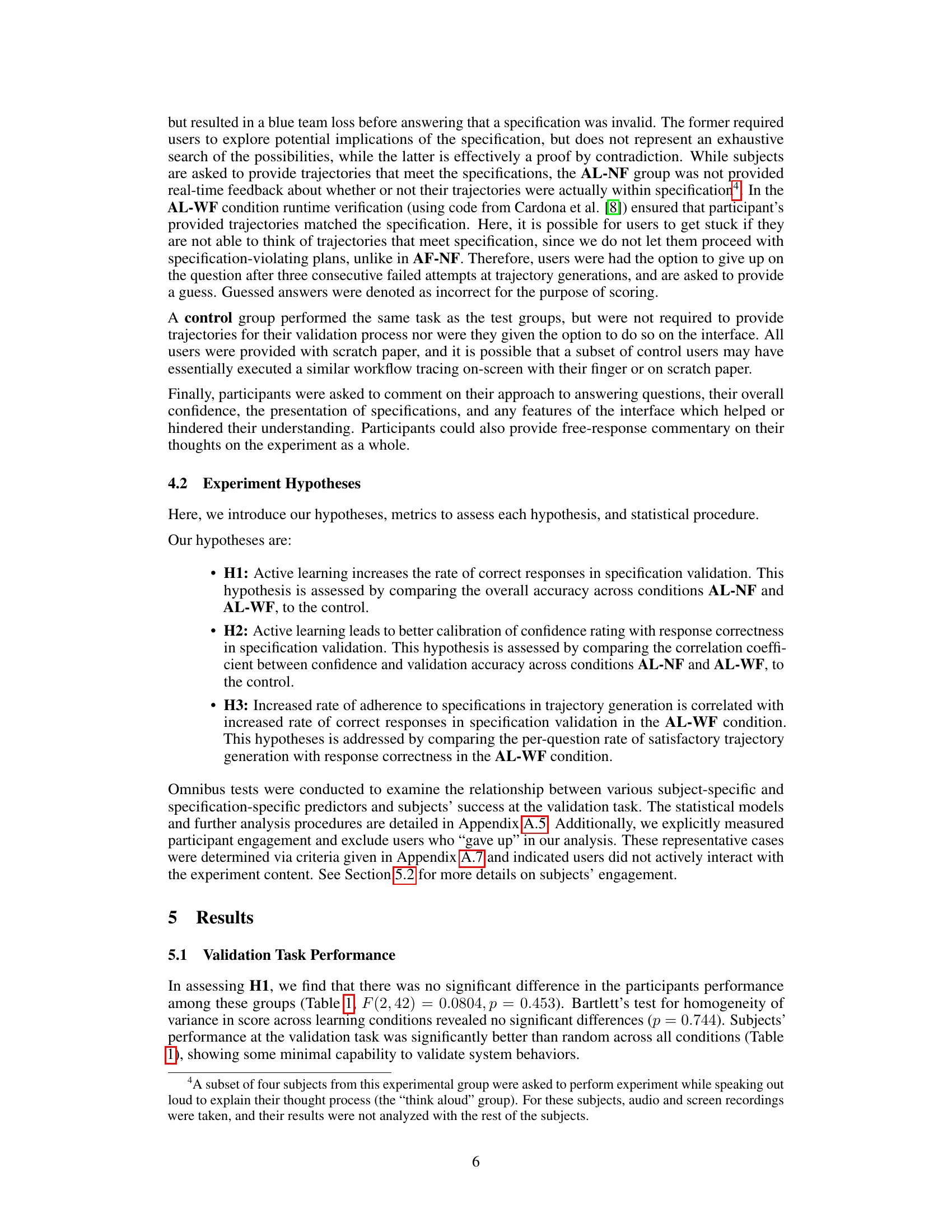

This table presents the overall accuracy of three different groups in a system validation task. The groups are: AL-NF (active learning with no feedback), AL-WF (active learning with feedback), and Control (no active learning). The table shows the mean accuracy, standard deviation, p-value (statistical significance), and effect size (Cohen’s d) for each group. The overall accuracy across all groups was 65% ± 15%.

In-depth insights#

Human STL Validation#

The concept of ‘Human STL Validation’ explores the crucial intersection of formal methods and human understanding in the context of autonomous systems. It investigates the extent to which humans can effectively interpret and validate system behavior described using Signal Temporal Logic (STL), a formal specification language. The core challenge is bridging the gap between the precise, mathematical nature of STL and the inherent limitations of human cognitive abilities in processing complex logical structures. Research in this area highlights the difficulty humans face in correctly assessing STL specifications, even for relatively simple robot behaviors. This underscores the need for innovative approaches beyond simple translation of formal logic into natural language, which has proven insufficient. Active learning strategies, drawing upon pedagogical techniques, offer a promising avenue to improve human performance in STL validation. However, results show that even with active learning, validation accuracy remains limited, suggesting that deeper understanding of human cognitive processes and the design of more intuitive interfaces for interacting with formal specifications are necessary for effective human-in-the-loop system validation. Ultimately, the success of human STL validation depends on finding ways to make formal methods more accessible and comprehensible to non-experts, a critical step towards enabling broader human oversight and trust in increasingly autonomous systems. Future research should focus on tailored human-centered interfaces, improved pedagogical methods and further exploration of interactive validation tools.

Active Learning’s Role#

The study explores active learning as a pedagogical method to enhance human comprehension and validation of robot policies expressed in Signal Temporal Logic (STL). The core hypothesis is that active learning, by engaging users in a more interactive and iterative process, improves human understanding of STL specifications and consequently, accuracy in policy validation. Two active learning conditions were compared: one with feedback on the correctness of generated trajectories and one without. A control group performed standard policy validation without active learning. Results surprisingly revealed no significant difference in validation accuracy among the three groups. This challenges the assumption that formal specifications inherently guarantee human interpretability and highlights the complexity of bridging the gap between formal methods and human cognition. The lack of a significant performance boost with active learning, despite increased user engagement, suggests that simply providing interaction and feedback is insufficient to overcome inherent challenges in understanding and interpreting formal logic. The study’s findings underscore the need for further research into novel techniques to facilitate human interpretation of formal specifications for autonomous systems and underscores the importance of carefully considering usability and interpretability aspects in the design of AI systems for broader application.

ManeuverGame Design#

The design of ManeuverGame is crucial to the paper’s methodology. It’s a purpose-built grid-world game enabling controlled experimentation on human validation of robot policies expressed in Signal Temporal Logic (STL). The game’s simplicity is key—its clear objectives and easily-observable agent behaviors allow for a focused assessment of human understanding of formal specifications. By manipulating game parameters, the researchers can systematically test how different types of specifications impact a human’s ability to validate them. This controlled environment eliminates the complexities of real-world scenarios allowing for a more precise analysis of active learning’s impact on human validation performance. The integration of runtime verification further enhances the experiment’s utility and allows for immediate feedback to participants, potentially improving learning and accuracy. While the simplicity may limit generalizability, it’s essential for isolating the effects of active learning and formal specifications on human understanding in a rigorous manner.

Interpretability Gap#

The concept of “Interpretability Gap” in the context of AI, particularly concerning autonomous systems, highlights a critical disconnect between the formal mathematical specifications used to design systems and human understanding. Formal methods, while offering rigorous verification, often fail to translate meaningfully into human-interpretable explanations of system behavior. This gap undermines the core goal of validation, where humans must verify that a system operates as intended. The paper’s exploration of active learning techniques, though showing modest improvements in validation accuracy, underscores the complexity of this challenge. The inherent difficulty in bridging the gap lies not just in the technical aspects of formal logic but also in the cognitive processes of humans, who are prone to biases and limitations in interpreting symbolic representations. Simply translating formal specifications into natural language does not solve the problem; instead, it can introduce additional layers of complexity and misunderstanding. Therefore, future work should focus on more user-centered design methodologies that account for human cognitive limitations and incorporate feedback mechanisms to refine both the formal specifications and the validation processes themselves, thus narrowing the Interpretability Gap.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work are multifaceted. Firstly, a more in-depth investigation into the cognitive processes involved in human validation of formal specifications is crucial. This includes exploring the influence of various factors like specification complexity, presentation style, and prior experience with formal methods. Secondly, the development and testing of novel pedagogical approaches, beyond active learning, are needed to improve human interpretability. Thirdly, the limitations of using formal methods for human-interpretable validation should be acknowledged, and research should focus on alternative methods or augmentations that improve human engagement and understanding. Finally, expanding the validation scenarios beyond simplified games to real-world robot applications is necessary to evaluate the practical implications of these findings. This would also require exploring the incorporation of more nuanced stakeholder intents and constraints to better represent realistic validation challenges.

More visual insights#

More on figures

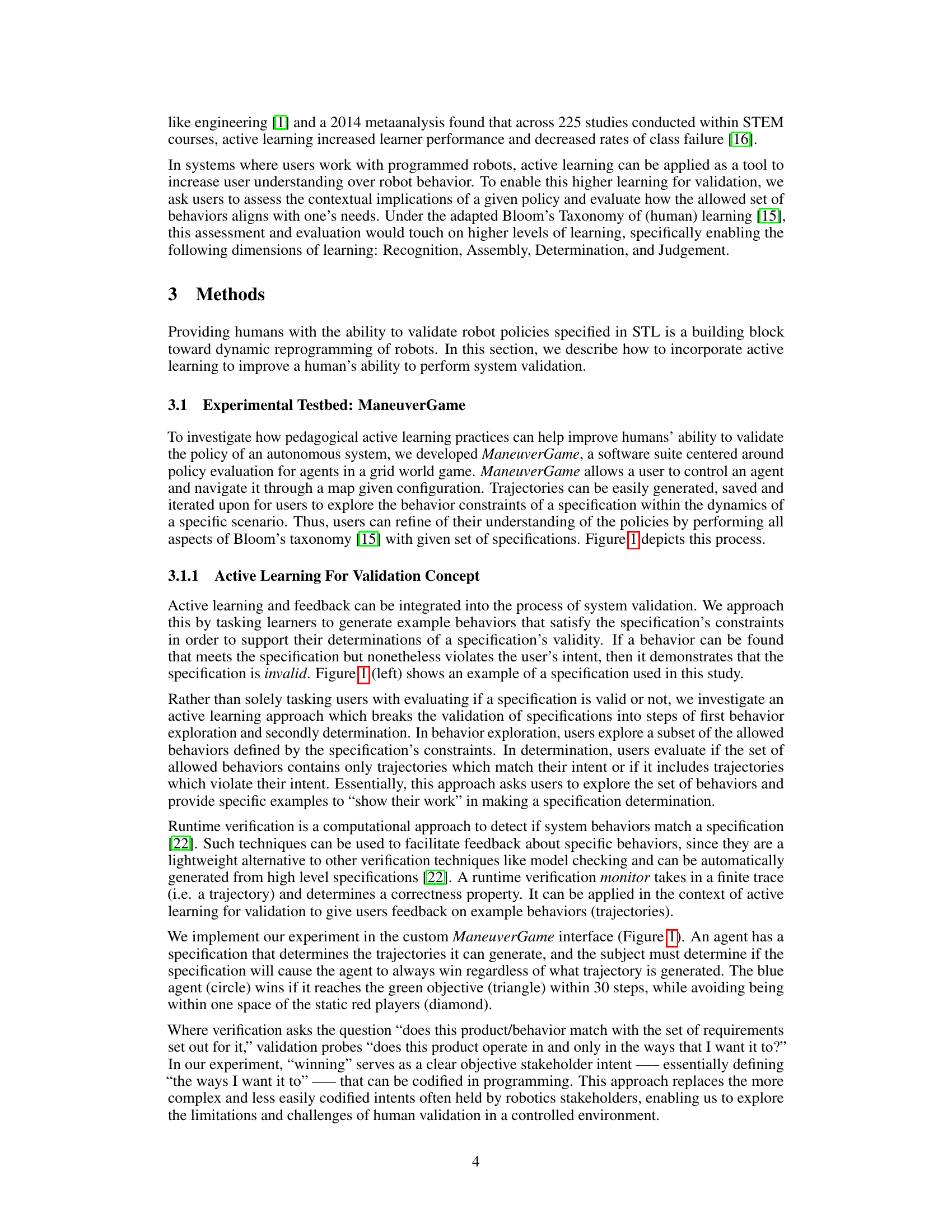

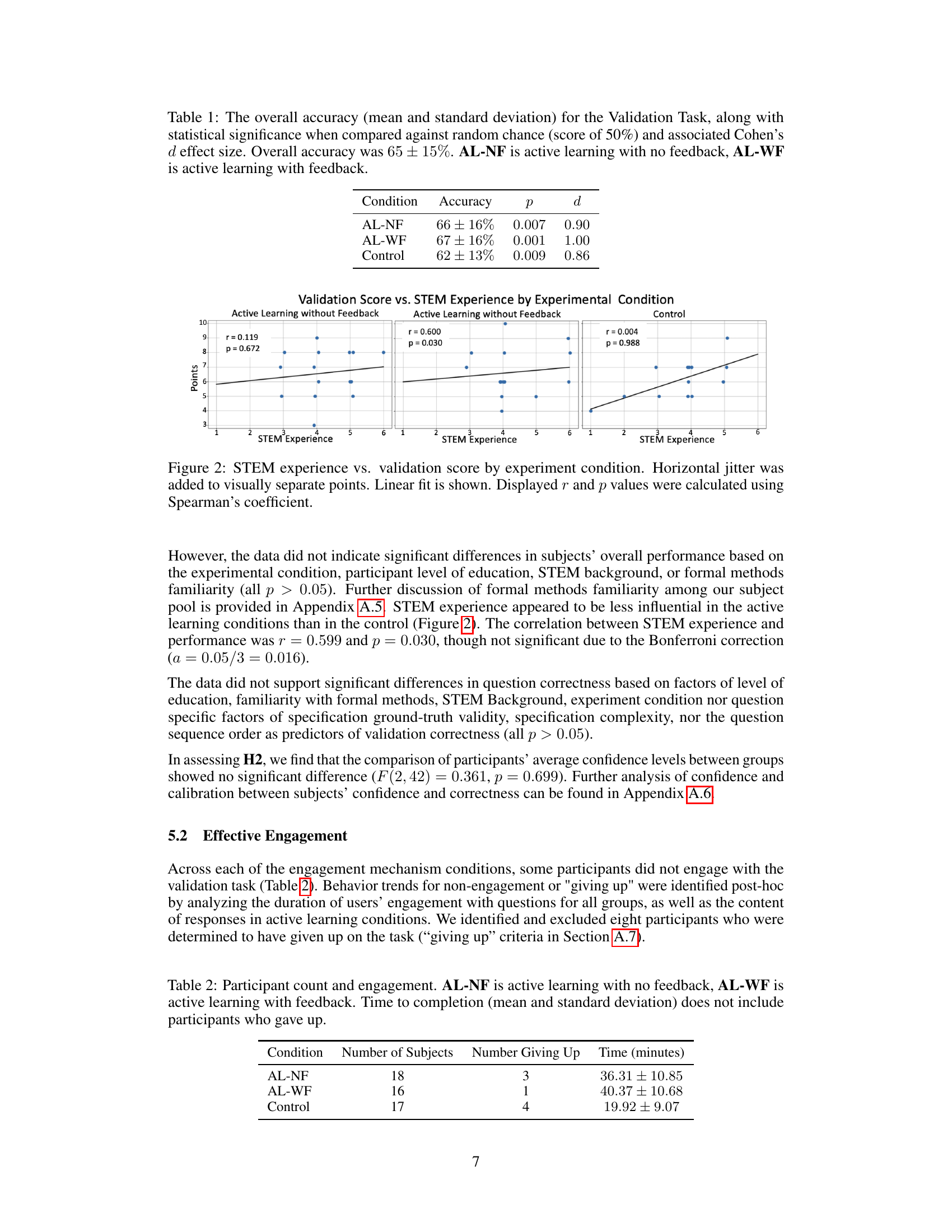

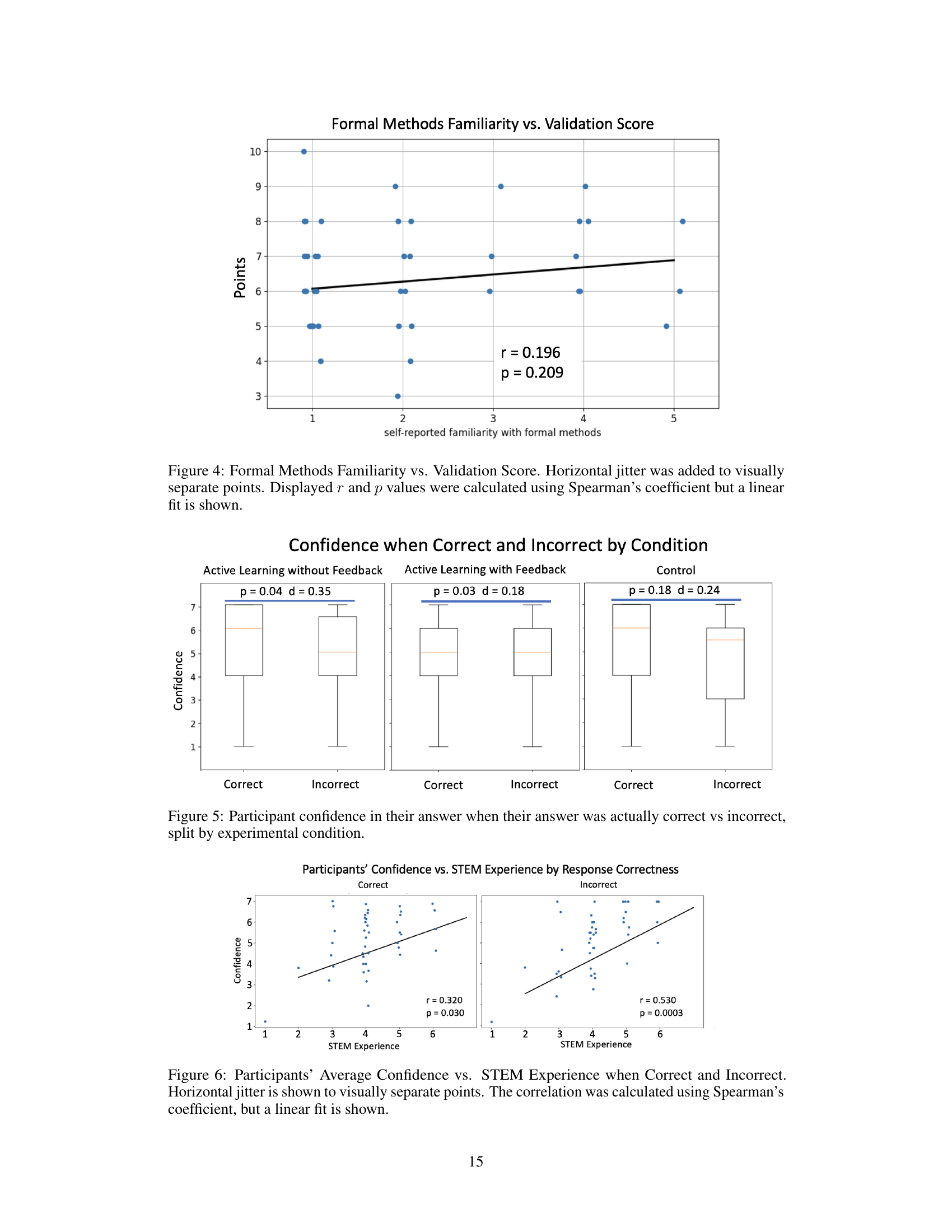

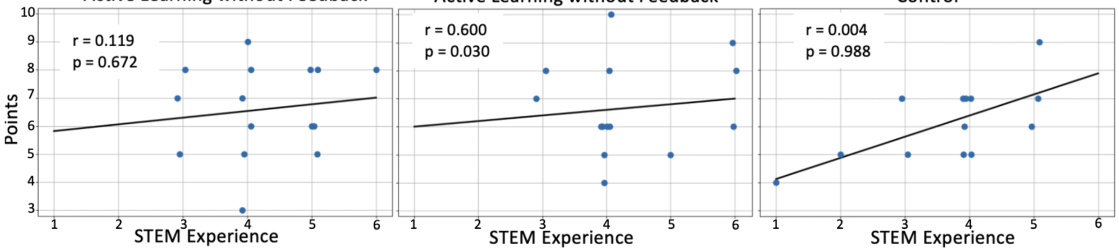

This figure displays the correlation between STEM experience and validation scores across three experimental conditions: Active Learning without Feedback, Active Learning with Feedback, and Control. The x-axis represents STEM experience, and the y-axis represents validation scores (points). Each point represents a participant. Horizontal jitter has been applied to spread out points with overlapping x-values for better visualization. A line of best fit is displayed for each condition, along with the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) and its associated p-value. The results indicate varying degrees of correlation between STEM experience and validation performance across different experimental setups.

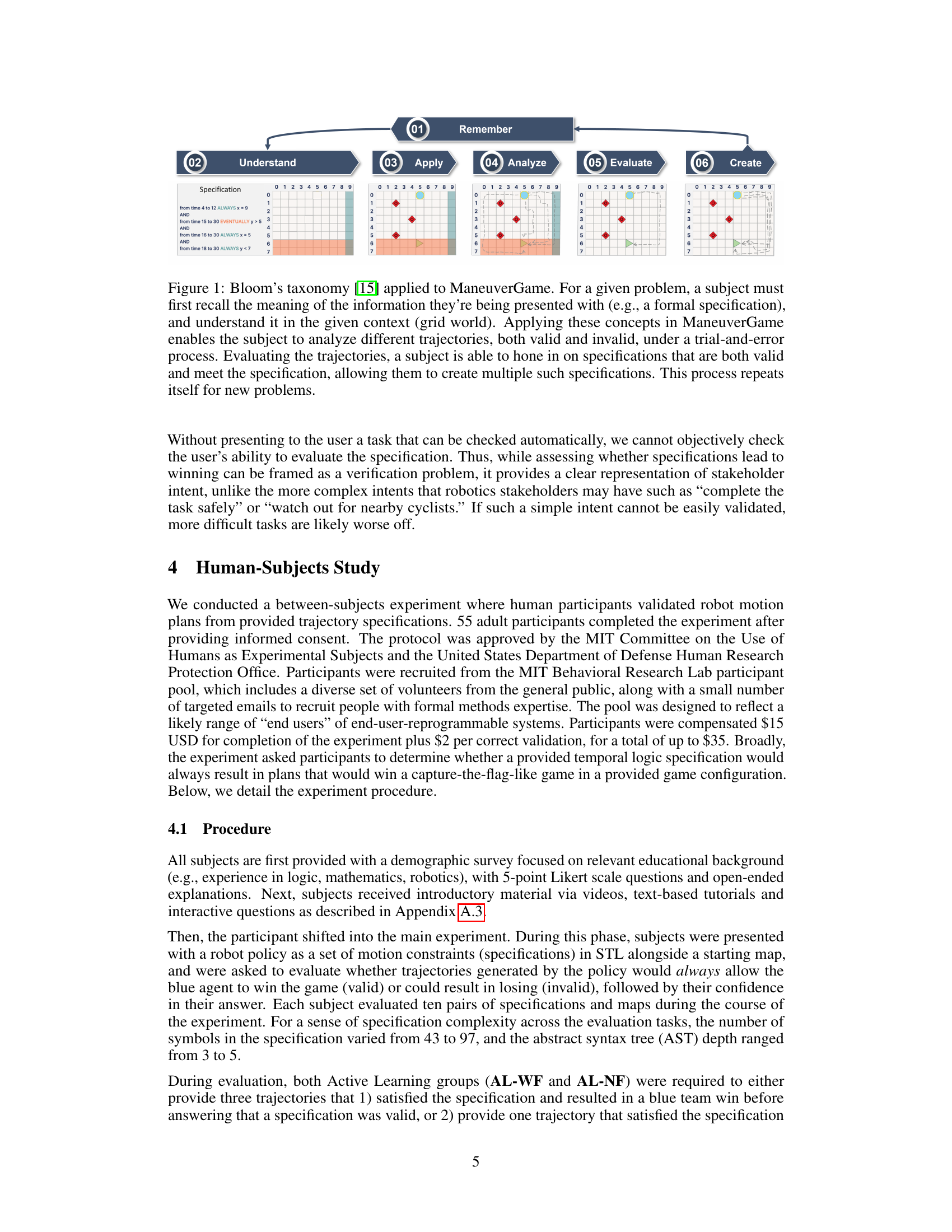

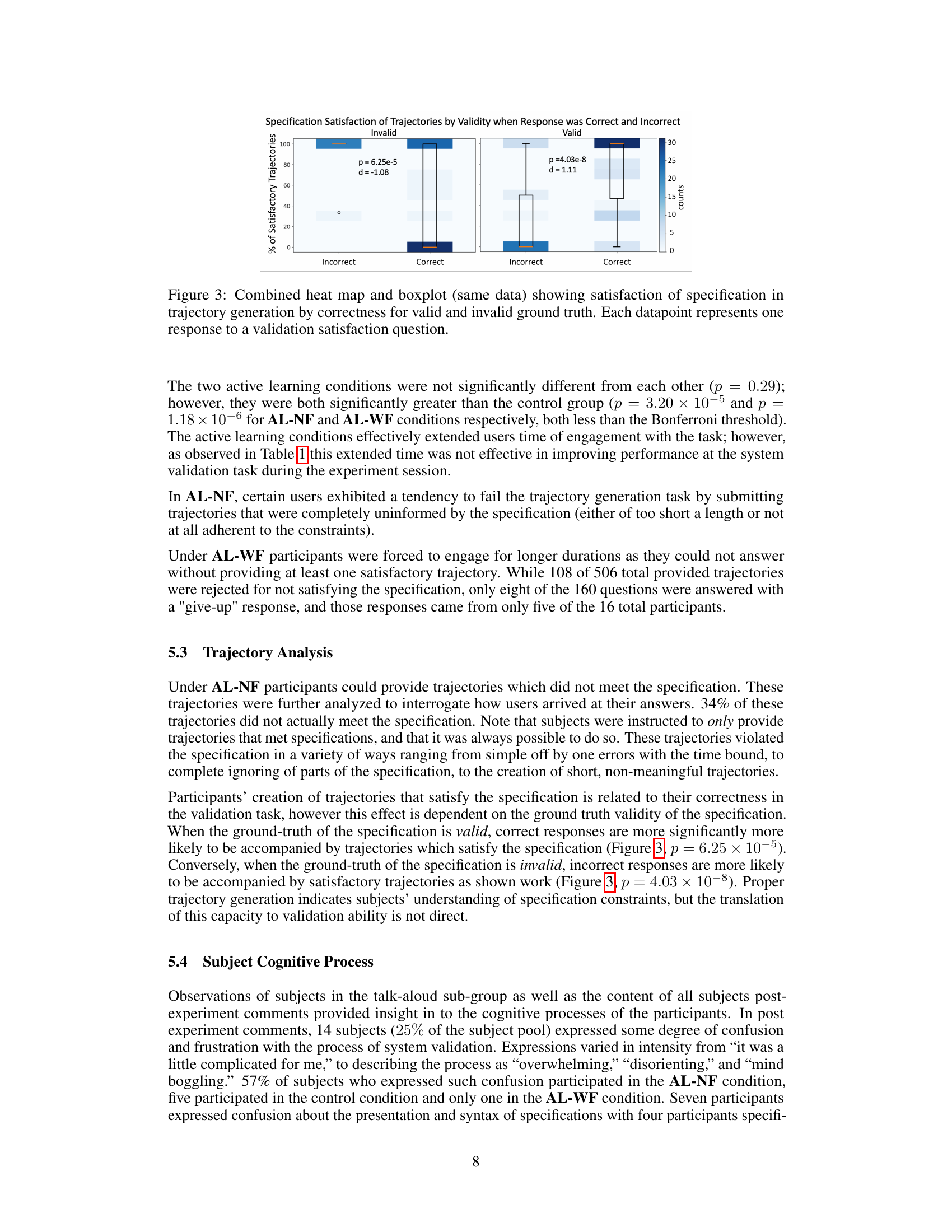

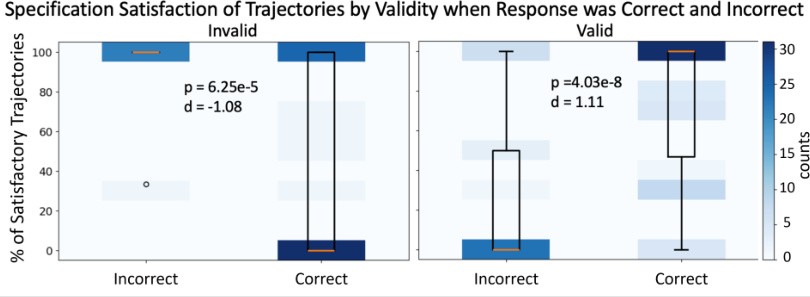

This figure shows the relationship between the correctness of participants’ responses and whether the generated trajectories satisfied the specification. It’s broken down by whether the specification was valid or invalid. The heatmap shows the distribution of counts for each combination of response correctness (correct/incorrect) and trajectory satisfaction (satisfied/not satisfied) and the boxplots show the percentage of satisfactory trajectories for each combination.

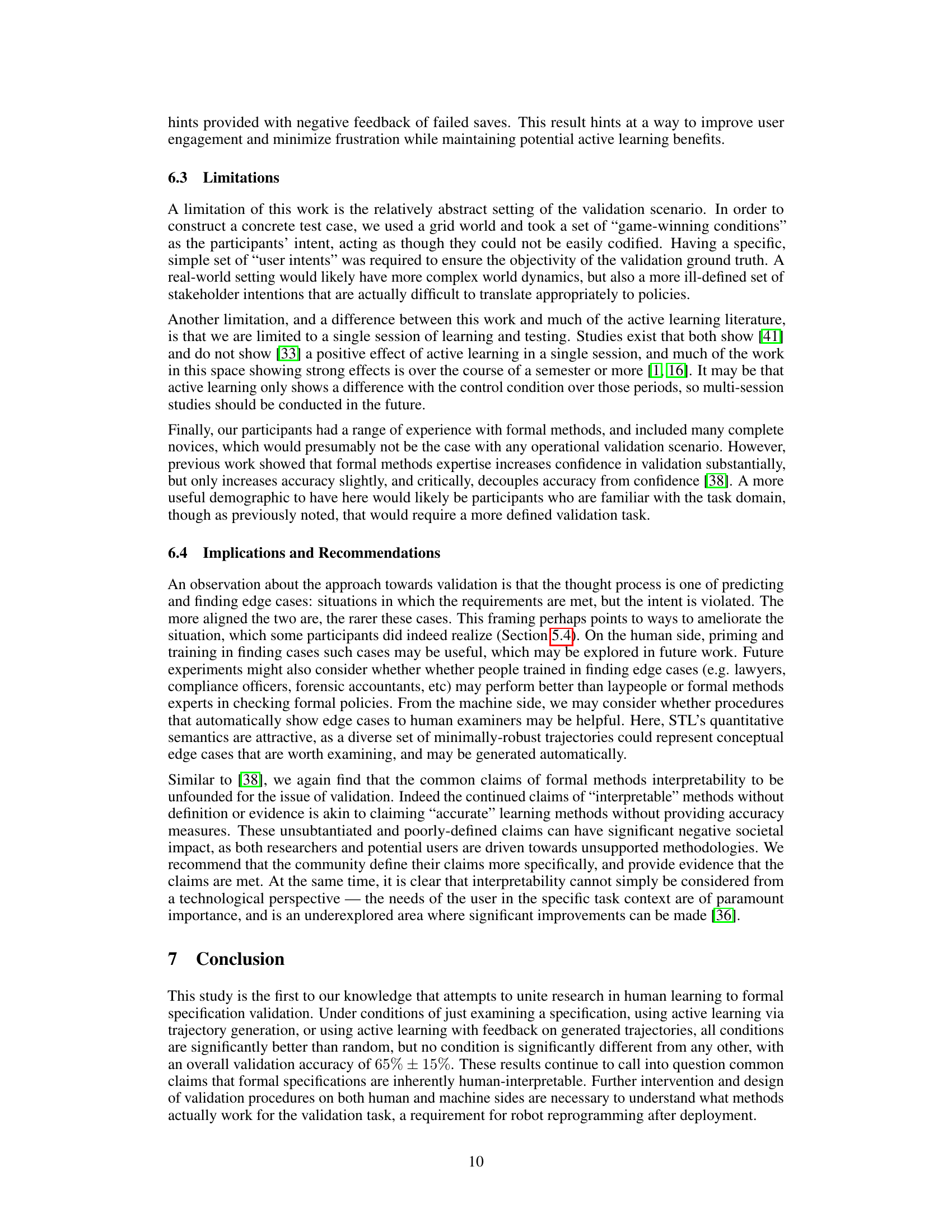

This figure shows the correlation between participants’ self-reported familiarity with formal methods and their performance on the validation task. The horizontal jitter helps to visualize individual data points more clearly, and the low r value (0.196) and high p-value (0.209) indicate that there is no statistically significant correlation between formal methods familiarity and validation performance.

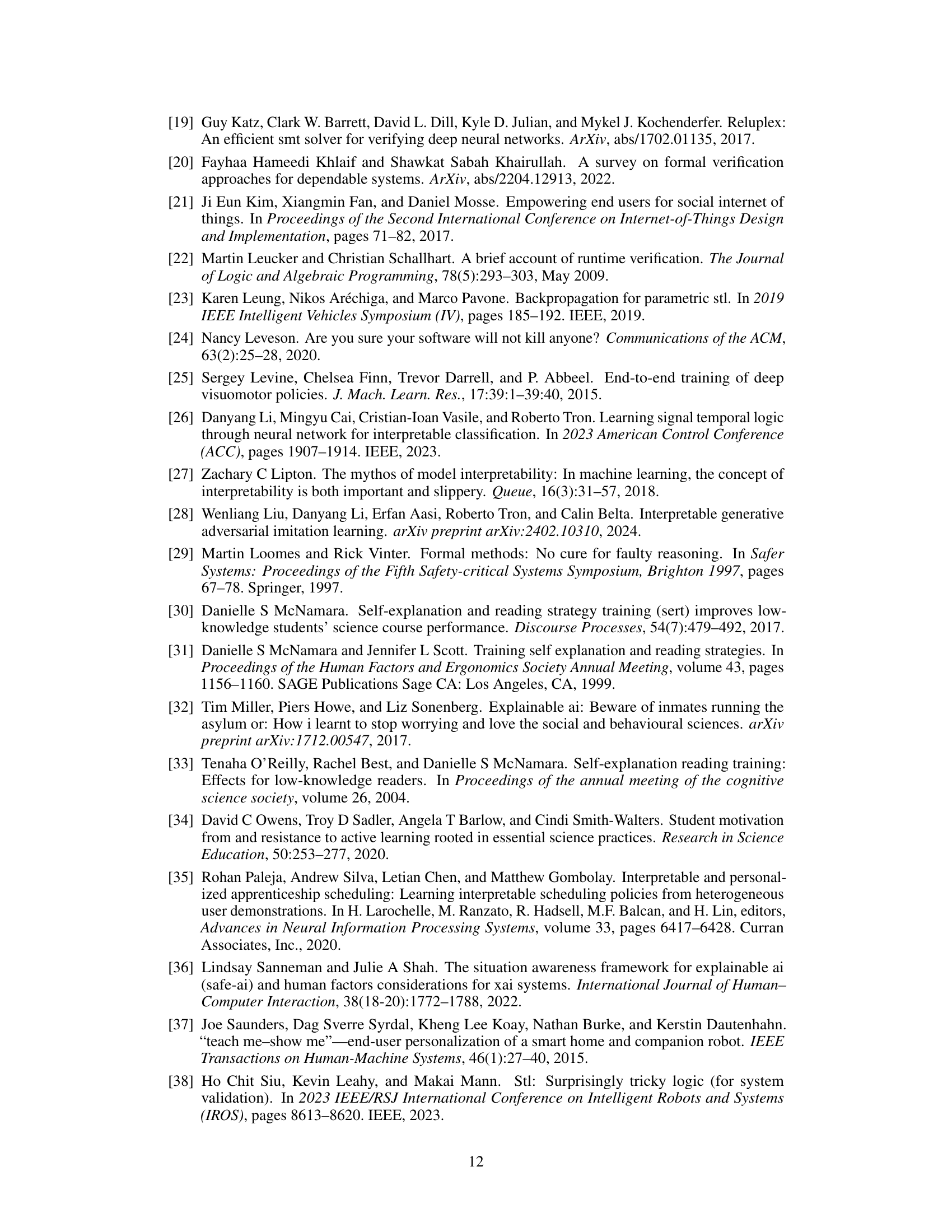

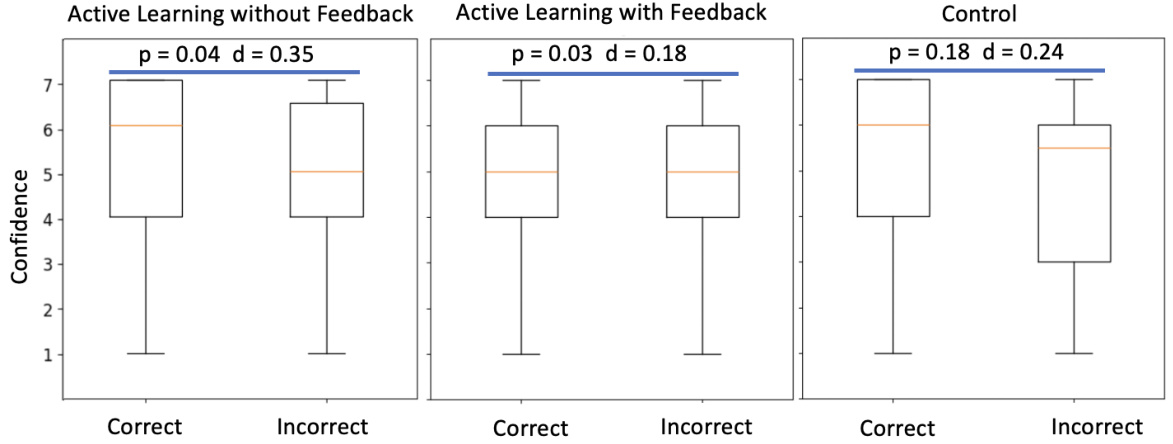

This figure shows box plots illustrating the level of confidence participants reported for their answers, categorized by whether their answers were correct or incorrect. The data is further broken down by the three experimental conditions: Active Learning without Feedback, Active Learning with Feedback, and Control. The p-values and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are displayed above each group of box plots, showing the statistical significance of the differences in confidence between correct and incorrect responses within each condition.

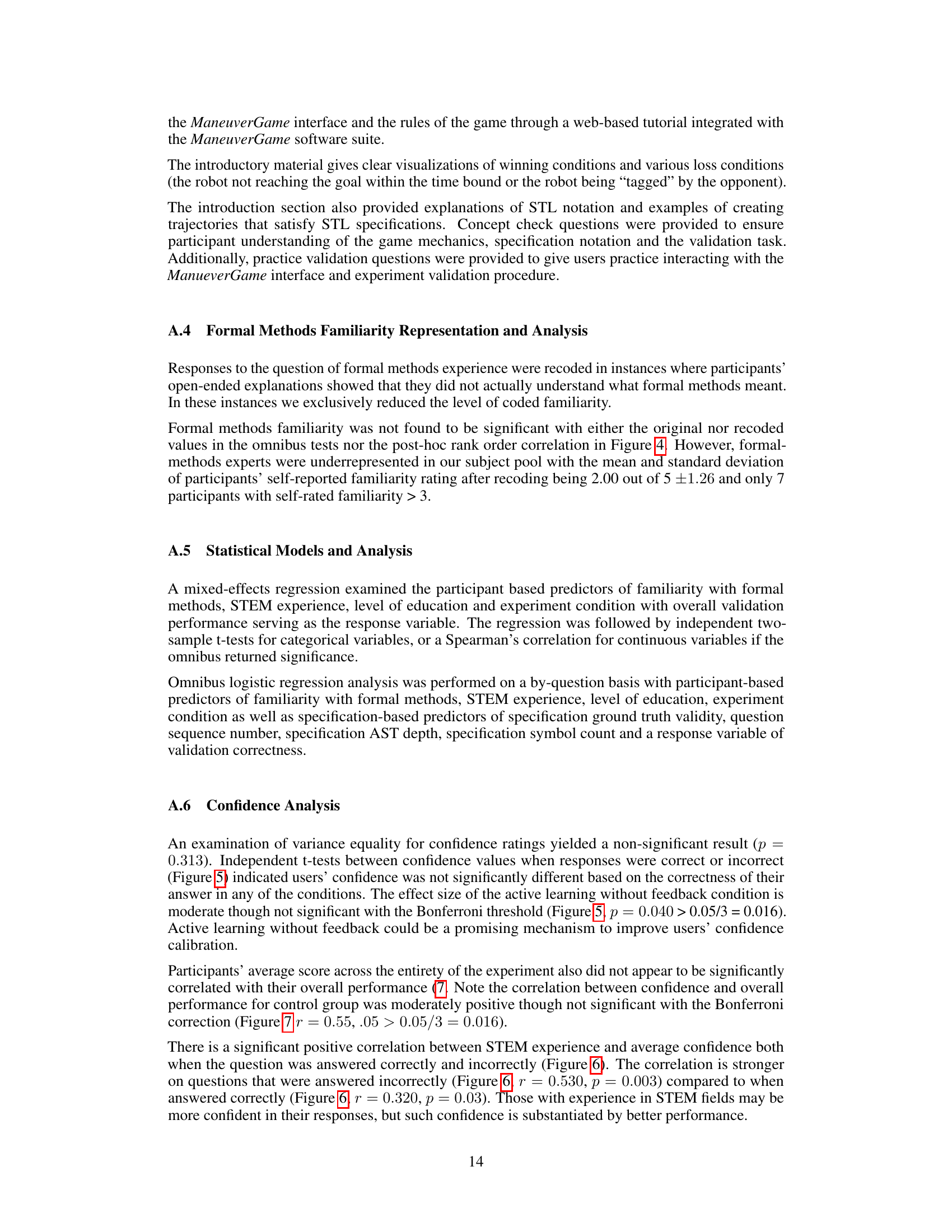

This figure shows two scatter plots, one for correct answers and one for incorrect answers, depicting the relationship between participants’ average confidence and their STEM experience. The x-axis represents STEM experience, and the y-axis represents average confidence. A linear regression line is plotted for each dataset. The correlation coefficient (r) and p-value are displayed for each plot to show the statistical strength of the correlation. The plot suggests that those with more STEM experience tend to exhibit higher confidence, especially when giving incorrect answers.

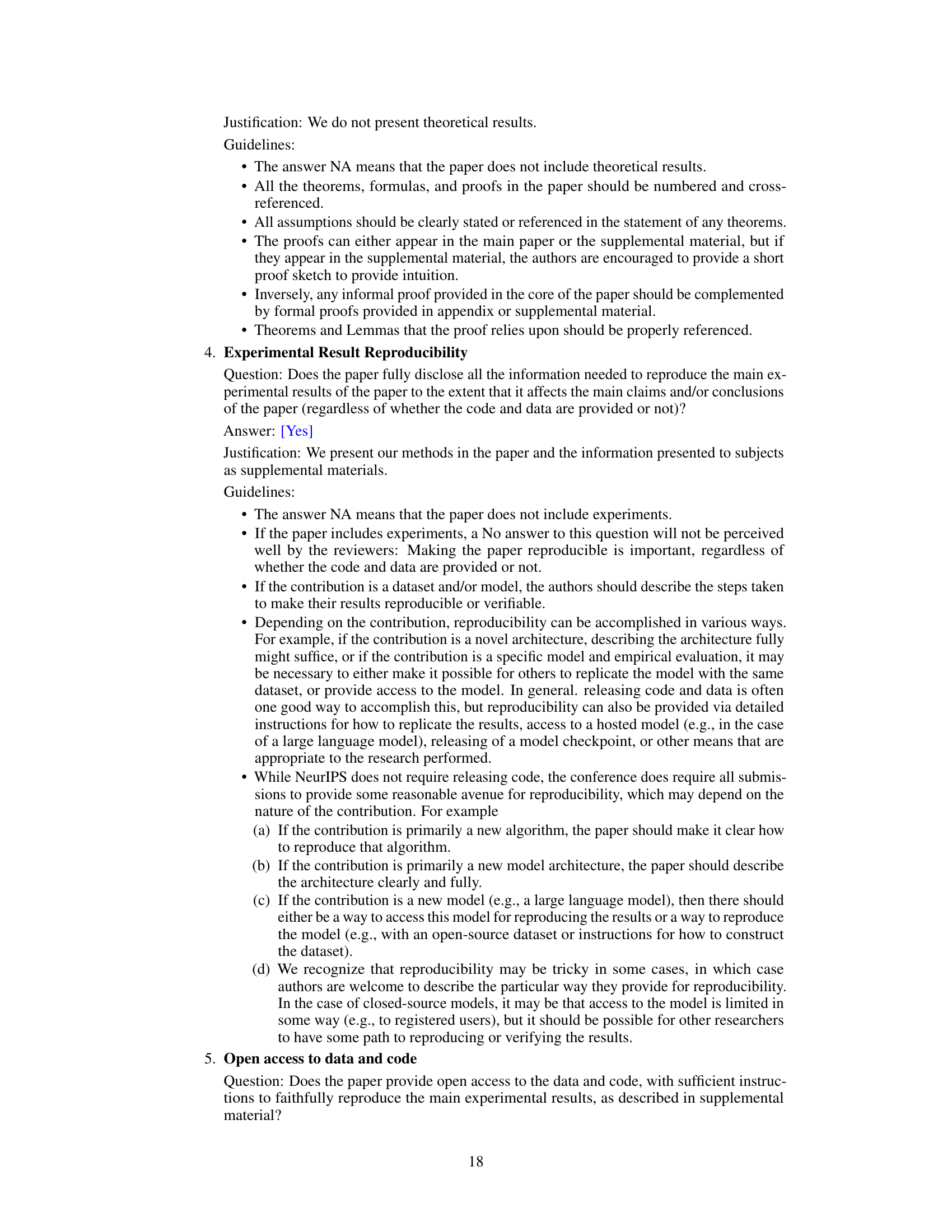

This figure displays the correlation between the average confidence levels and the total validation score achieved by participants across different experimental conditions (active learning with and without feedback, and control). A linear fit is shown for visualization purposes, but statistical significance was determined using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, and the Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons. The results indicate a positive correlation in all conditions, suggesting higher average confidence is generally associated with higher scores; however, none of these correlations reach statistical significance.

Full paper#