↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are prone to generating false information, known as ‘hallucinations’. Existing detection methods often require multiple model responses or extensive external knowledge bases, limiting their real-time applicability. This is a significant problem for using LLMs in practical applications where accuracy is vital.

This research introduces LLM-Check, a novel approach to detect hallucinations within a single LLM response by analyzing internal model representations (hidden states and attention maps). LLM-Check is significantly faster than existing methods (up to 450x speedup) and achieves improved accuracy, even without external knowledge. This is achieved by analyzing internal representations, making it suitable for real-time applications. The method is tested across various datasets and settings (zero-resource, multiple responses, and retrieval-augmented generation), showing consistently strong performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with LLMs because it introduces a novel, efficient method for detecting hallucinations. Its compute efficiency and applicability across diverse datasets make it highly relevant to the current challenges in real-world LLM deployment, opening up new research directions in hallucination mitigation and improving LLM reliability.

Visual Insights#

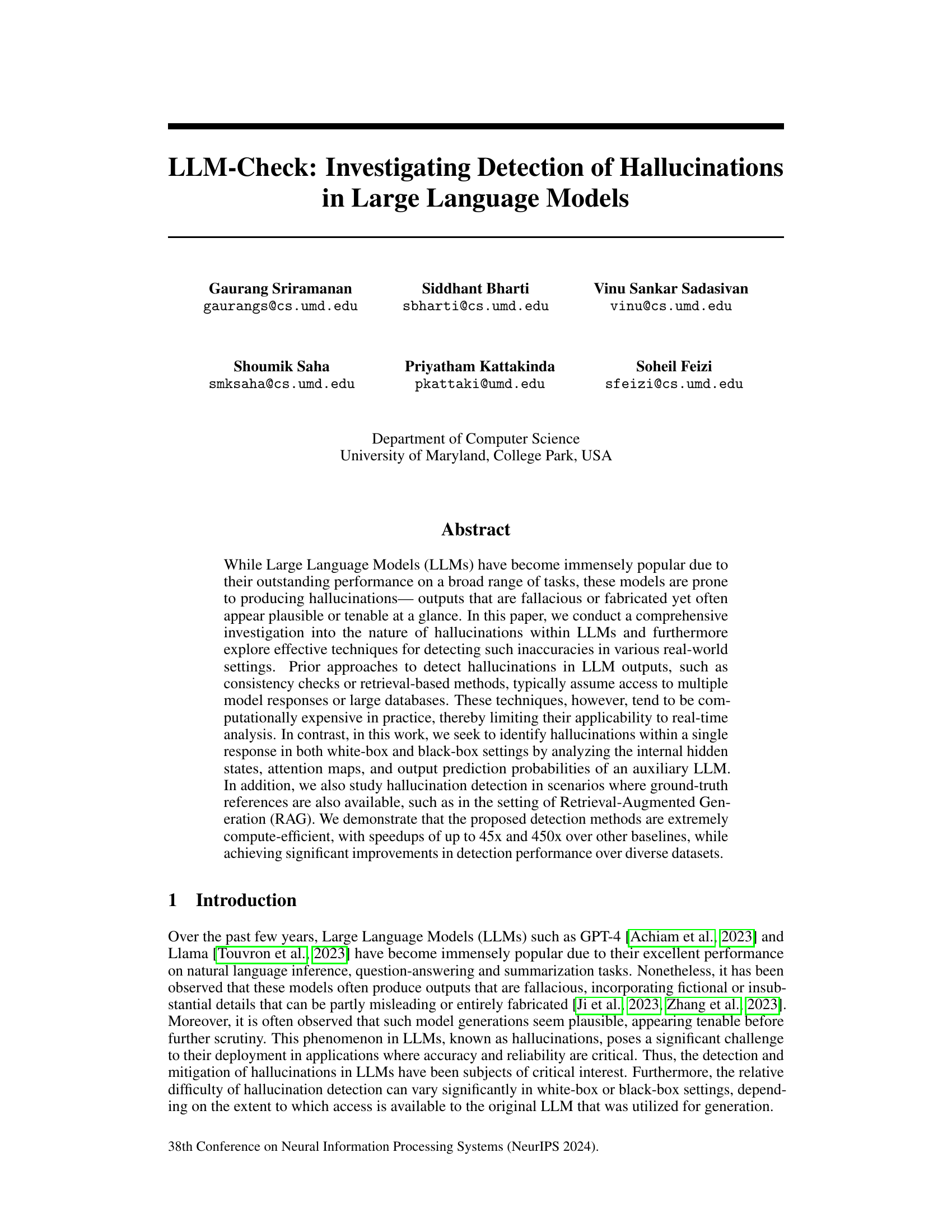

This figure presents a taxonomy of hallucination detection settings, categorized by whether external references are available and whether multiple model responses are needed. It shows the different datasets and data splits used in the paper to evaluate these settings. The main categories are: No External References (with Single Model Response or Multiple Model Responses), and With External References (White-box and Black-box settings). Each category is then further sub-categorized based on the available datasets and how they were used for analysis. The figure visually represents the relationships between different settings and the data used for evaluation within each scenario.

This table compares several hallucination detection methods (FAVA, SelfCheckGPT, INSIDE, RAGTruth, and LLM-Check) across various criteria. It highlights whether each method requires model training, multiple responses, is computationally efficient, performs sample-specific or population-level detection, and relies on external retrieval databases.

In-depth insights#

LLM Hallucination#

Large language models (LLMs) are prone to producing hallucinations—outputs that are factually incorrect yet convincingly plausible. This phenomenon significantly hinders the reliability and trustworthiness of LLMs, particularly in applications demanding accuracy. Understanding the root causes of LLM hallucinations is crucial; factors like biases in training data, limitations in the model’s architecture, and the inherent stochasticity of generation processes are all implicated. Effective detection methods are essential to mitigate the impact of these inaccuracies, but challenges remain in balancing computational efficiency with detection accuracy, especially in real-time scenarios. Research exploring different detection techniques, from analyzing internal model representations to leveraging external knowledge sources, is vital to address this challenge. The development of robust and efficient hallucination detection methods is a critical step in harnessing the full potential of LLMs while mitigating their inherent risks.

Single-Response Check#

The concept of a ‘Single-Response Check’ for hallucination detection in LLMs presents a significant advancement. Traditional methods often rely on multiple model outputs or external knowledge bases, increasing computational costs and latency. A single-response approach directly addresses this limitation by focusing on analyzing the internal workings of the model – its hidden states, attention mechanisms, and output probabilities – from a single generation. This allows for faster, more efficient hallucination detection suitable for real-time applications. However, the effectiveness hinges on the richness and reliability of the internal representations themselves, which can vary significantly across models and training datasets. White-box access (ability to examine internal model states) significantly improves detection accuracy compared to black-box scenarios, where only the output is available. While computationally efficient, the challenge lies in creating robust and generalizable scoring metrics that effectively capture the subtle signals indicative of hallucinations within a single response. Future research should concentrate on developing more sophisticated scoring metrics and exploring ways to enhance performance in black-box settings. The ultimate success of single-response checks rests on finding the right balance between computational efficiency and accurate, reliable identification of LLM hallucinations.

Eigenvalue Analysis#

Eigenvalue analysis, in the context of a research paper on detecting hallucinations in large language models, likely involves using the eigenvalues of matrices derived from the model’s internal representations (e.g., hidden states, attention maps). Eigenvalues capture the magnitude of influence of different components, revealing information about the model’s internal workings. By analyzing these eigenvalues, researchers can identify patterns associated with truthful versus hallucinated outputs. Significant differences in eigenvalue distributions between truthful and hallucinated responses could serve as a strong indicator for a detection method. The computational efficiency of this approach is crucial, particularly for real-time applications, as calculating eigenvalues can be computationally expensive for large matrices. Therefore, any proposed method would need to carefully balance accuracy with speed. The effectiveness ultimately depends on whether the underlying patterns in the model’s internal representations, reflected in the eigenvalues, reliably distinguish factual from fabricated outputs. This approach leverages a white-box view of the LLM, accessing its internal mechanisms to analyze the signal, making it potentially more powerful but less broadly applicable than black-box alternatives.

Efficiency & Speed#

The research paper emphasizes the computational efficiency of its proposed hallucination detection method. A key contribution is achieving significant speedups (up to 45x and 450x) compared to existing baselines. This efficiency is primarily due to the method’s reliance on analyzing internal LLM representations from a single forward pass, eliminating the need for multiple model generations or extensive external databases. The approach is designed for real-time analysis, which is a critical improvement over previous methods that are computationally expensive and lack practical applicability. The paper highlights the compute-efficient nature of its core techniques: eigenvalue analysis of internal representations and output token uncertainty quantification, both scalable and rapid. This focus on efficiency is a substantial advantage, allowing the method to be deployed in practical real-world applications where speed and resource constraints are significant factors.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section hints at several promising research directions. Improving hallucination detection performance is a primary goal, aiming for higher accuracy and reliability, especially at low false positive rates. Mitigating hallucinations directly within LLMs, perhaps by incorporating the proposed scoring metrics into reinforcement learning, is another key area. The authors also suggest more principled integration of external references through retrieval augmented generation (RAG), where hallucination detection could act as a pre-screening step before querying external knowledge bases. Finally, exploring combinations of different detection techniques might further improve the overall system’s robustness and efficiency. This suggests a future focus on combining the eigenvalue analysis of internal LLM representations with other methods to develop a more comprehensive hallucination detection framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

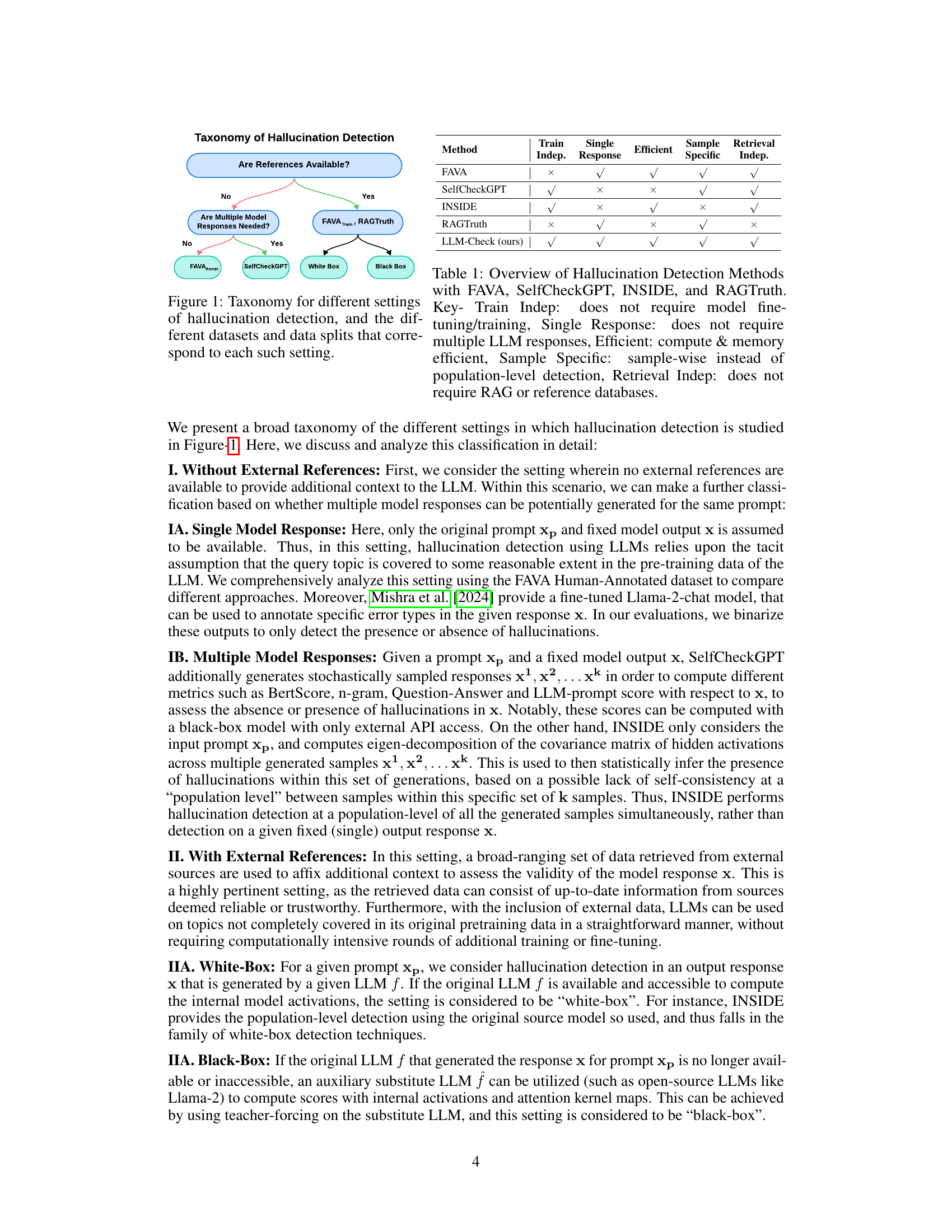

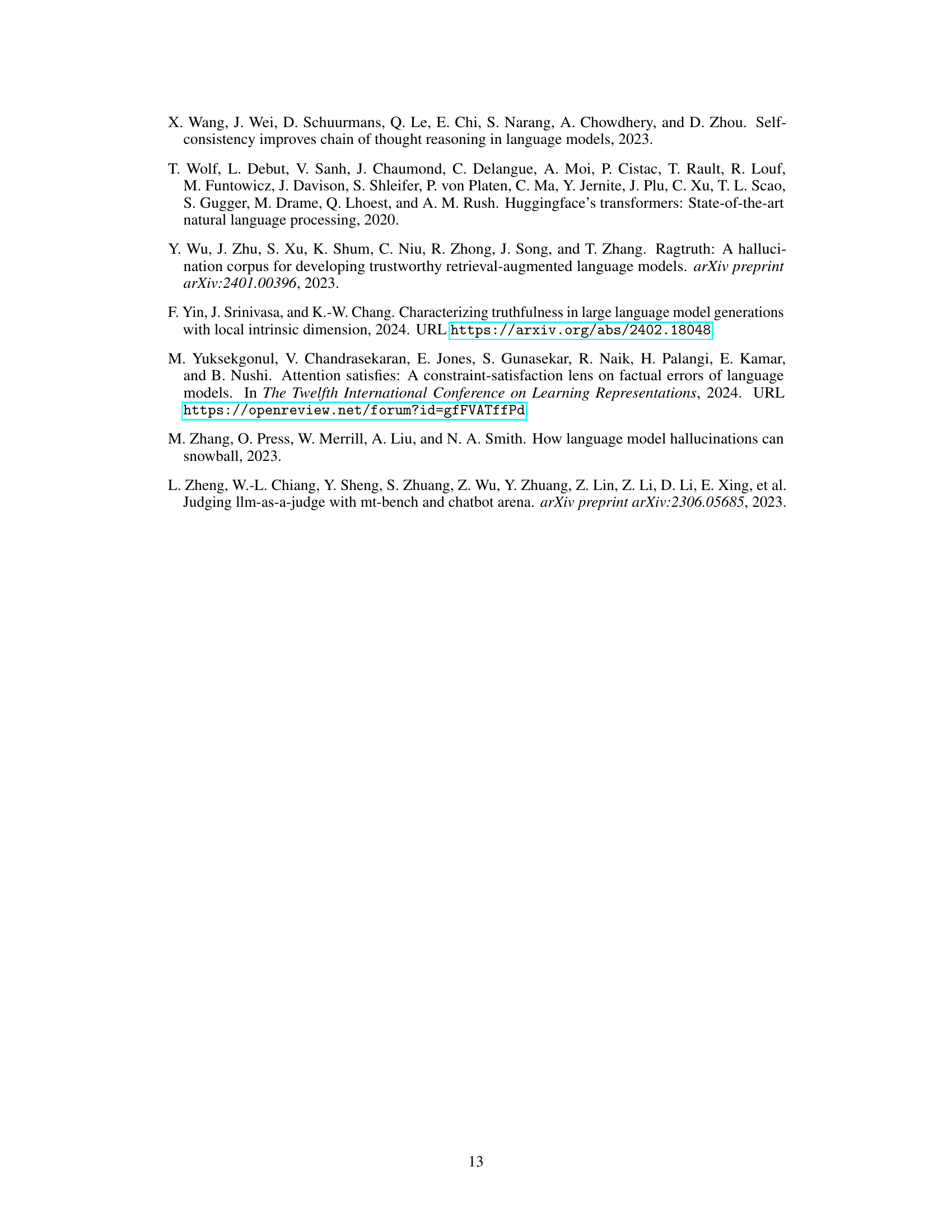

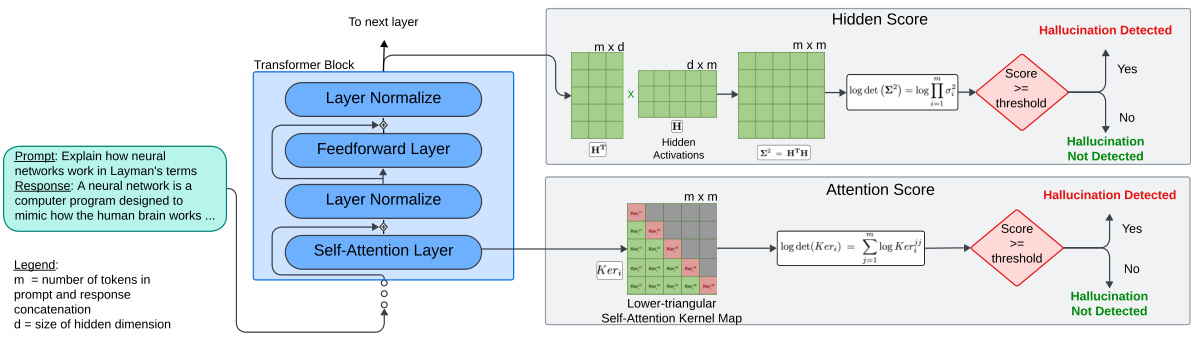

This figure shows a schematic of the proposed LLM-Check method for hallucination detection. It illustrates the process of analyzing internal LLM representations (hidden activations and attention kernel maps) to identify potential hallucinations. The input is a prompt and the LLM’s response. The hidden activations and attention kernel maps are extracted from the LLM’s internal layers. Then, eigenvalue analysis is performed on these representations to generate scores (Hidden Score and Attention Score). These scores are then compared to a threshold. If the score exceeds the threshold, a hallucination is detected; otherwise, it is not detected.

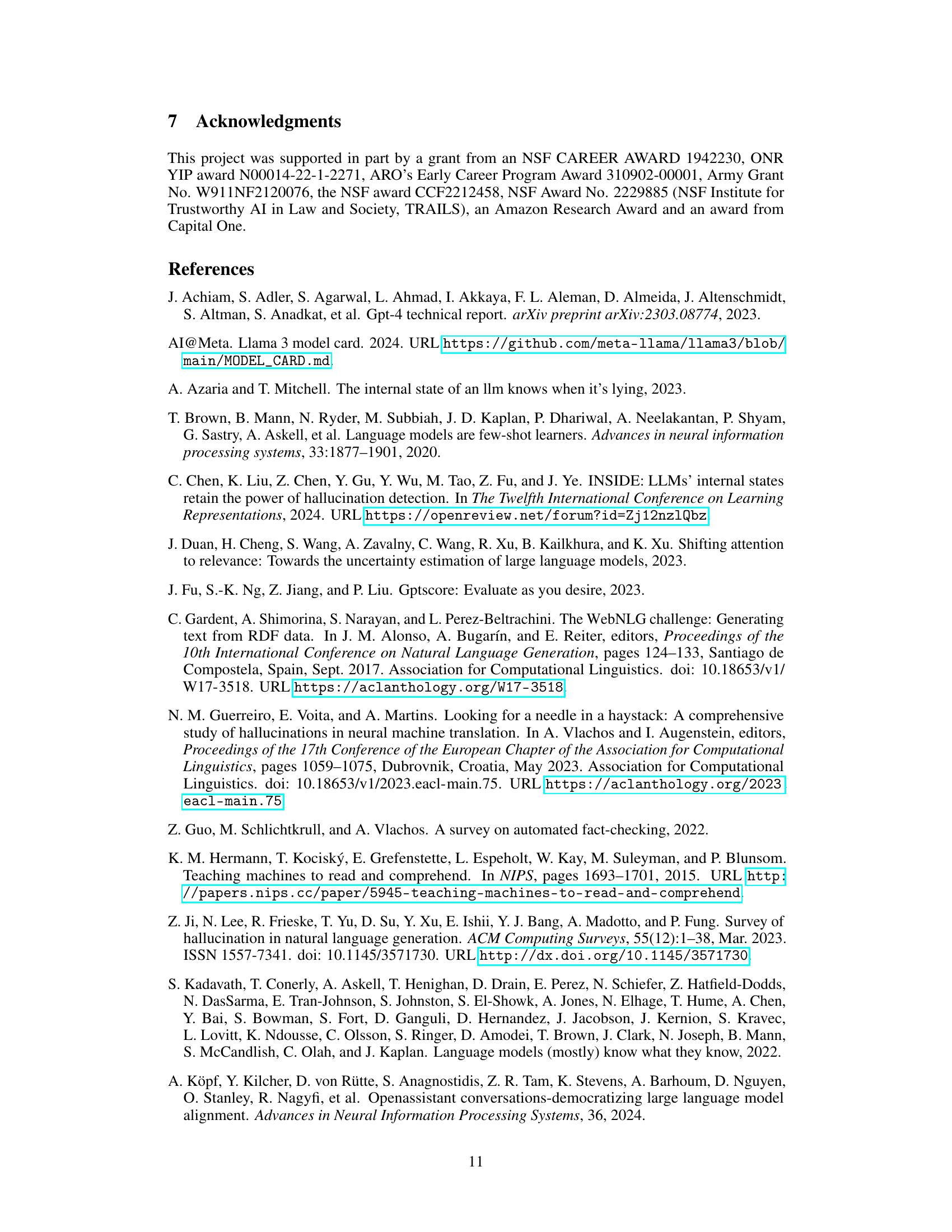

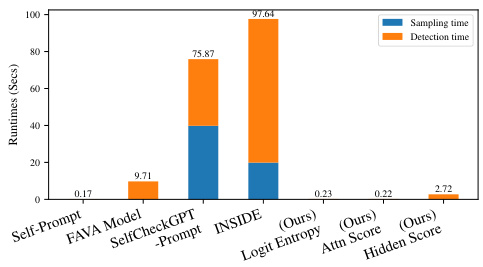

This figure compares the runtimes of different hallucination detection methods. It shows that the proposed LLM-Check method (using Logit Entropy, Attention Score, and Hidden Score) is significantly faster than other baselines such as Self-Prompt, FAVA Model, SelfCheckGPT-Prompt, and INSIDE. The LLM-Check methods achieve speedups of up to 45x and 450x over the other baselines. The speed advantage is mainly due to LLM-Check’s ability to detect hallucinations using a single forward pass of the LLM, without needing multiple responses or extensive external databases. The figure breaks down the time into sampling time (generating multiple responses in some methods) and detection time (the time the method needs to analyze the results and make a decision).

This figure shows a schematic of the hallucination detection pipeline using eigenvalue analysis of internal LLM representations. It illustrates the process starting from the input prompt and response concatenation, which goes through different layers of a transformer block, self-attention layer, feedforward layer, and layer normalization. The hidden activations and attention scores are extracted from the intermediate layers. Eigenvalue analysis is then performed on the hidden activations and the attention kernel map separately to compute two scores: Hidden Score and Attention Score. These scores are then compared to a threshold. If the score exceeds the threshold, hallucination is detected; otherwise, it is not detected. The figure visually represents how the internal representations of the model are analyzed to detect the presence of hallucinations in the LLM response.

This figure shows a schematic of the LLM-Check hallucination detection pipeline. It details the process, starting with the prompt and response being concatenated and fed into a transformer block. The hidden activations and the self-attention kernel map are extracted. Then, eigenvalue analysis is performed on these matrices, resulting in a Hidden Score and Attention Score, respectively. These scores are then compared to thresholds to determine if a hallucination is detected.

This figure shows a schematic of the hallucination detection pipeline proposed in the paper. The pipeline uses eigenvalue analysis of internal LLM representations, such as hidden activations and attention maps, to identify hallucinations. The input is a prompt and response from an LLM. The pipeline then analyzes the internal representations of the LLM to compute scores such as Hidden Score and Attention Score. These scores are then used to determine whether the response contains hallucinations.

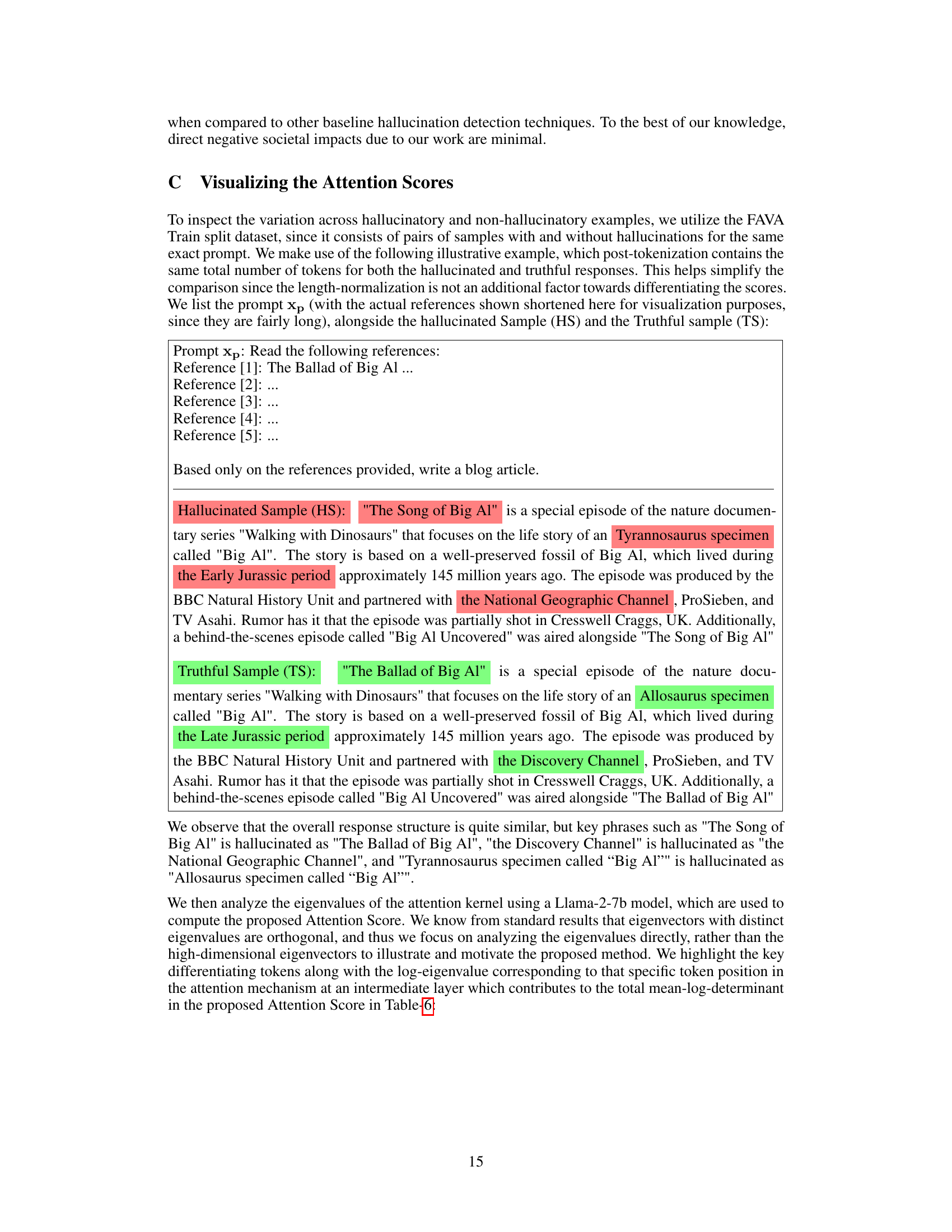

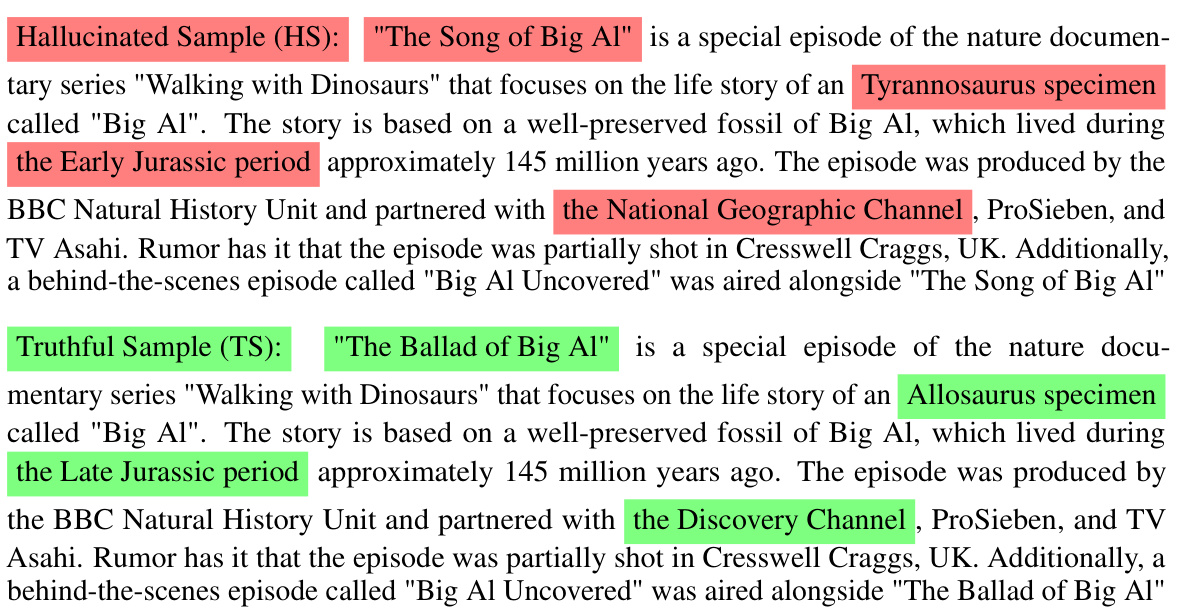

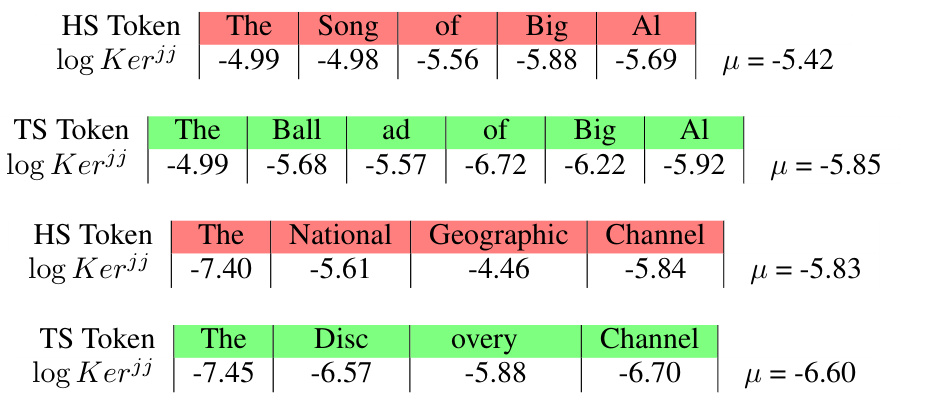

This figure visualizes the cumulative difference in log-eigenvalues between the hallucinated and truthful responses across token positions. It shows that, while not entirely monotonic, the cumulative sum of log-eigenvalues for the hallucinated response consistently remains higher than that of the truthful response across the entire token sequence. This supports the paper’s claim that the differences in log-eigenvalues can effectively distinguish between hallucinated and truthful responses.

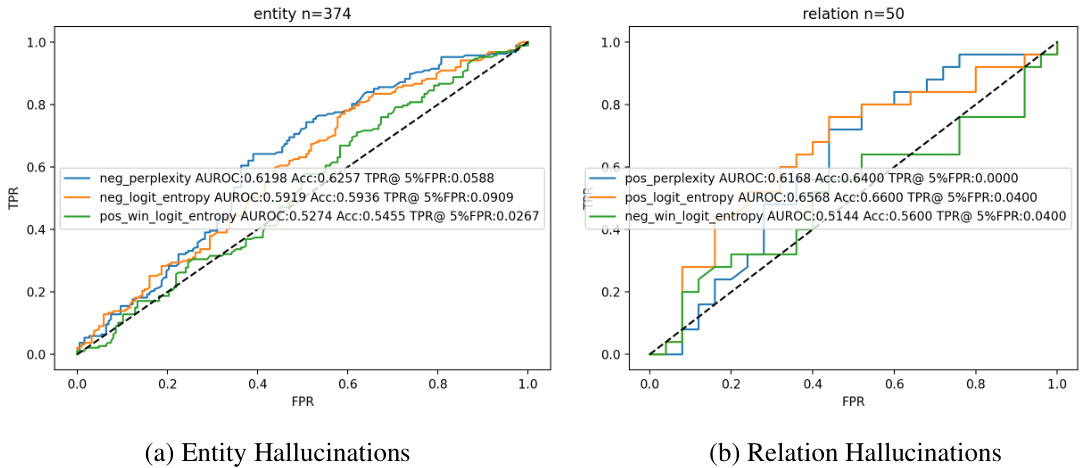

This figure shows Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for logit-based hallucination detection methods on the FAVA dataset. Two subfigures are presented: one for entity hallucinations and one for relation hallucinations. Each subfigure displays ROC curves for different logit-based metrics (negative perplexity, negative logit entropy, positive logit entropy, etc.). The results indicate that considering both positive and negative detection scores improves the performance of the hallucination detection.

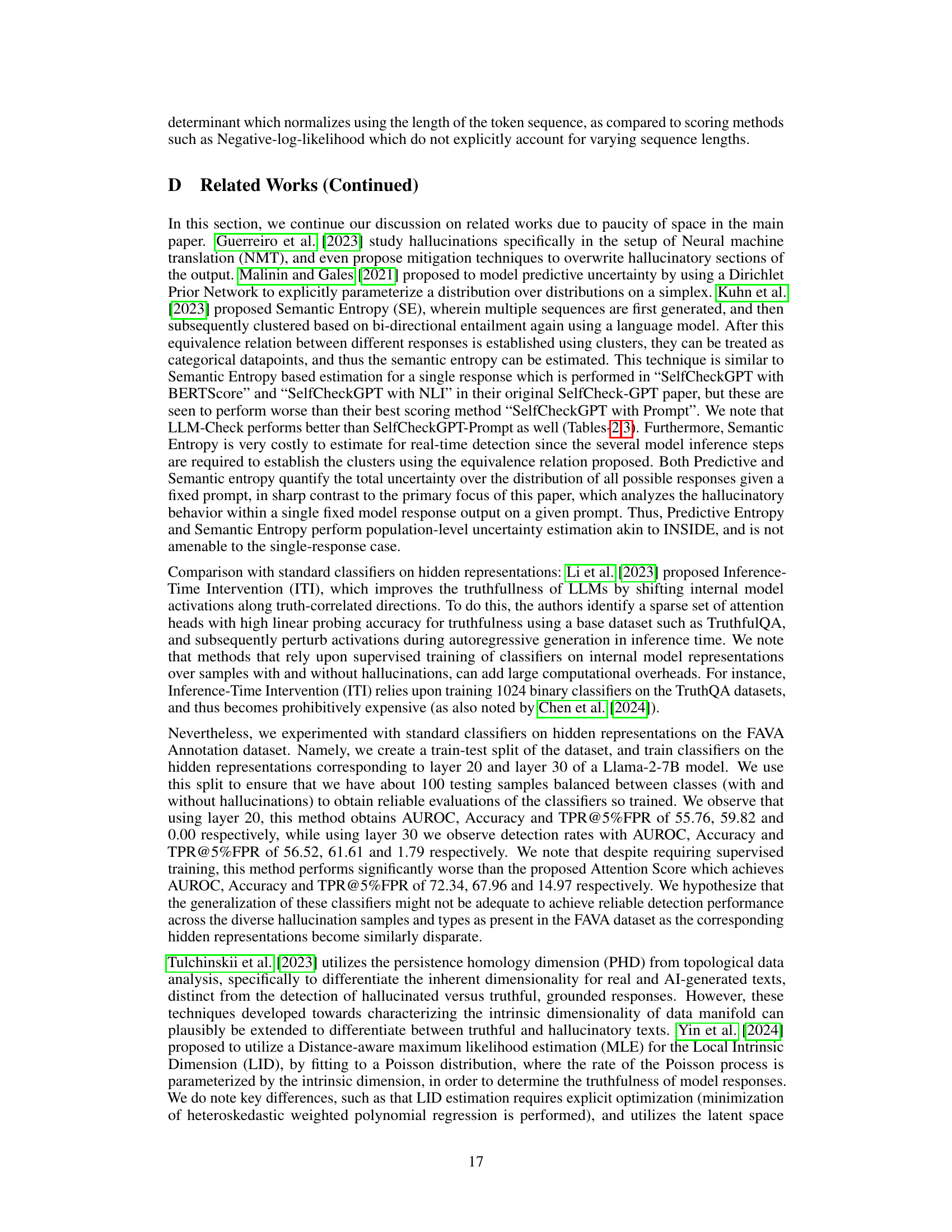

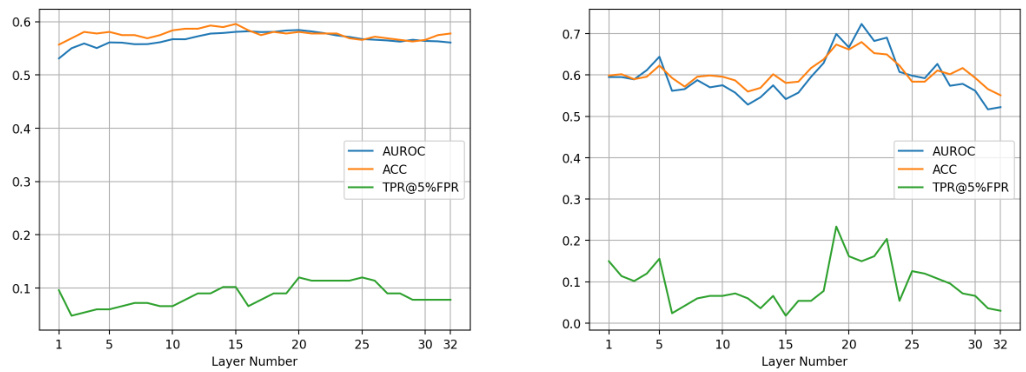

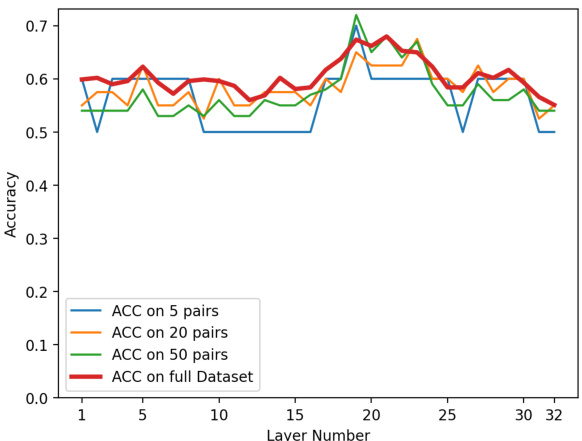

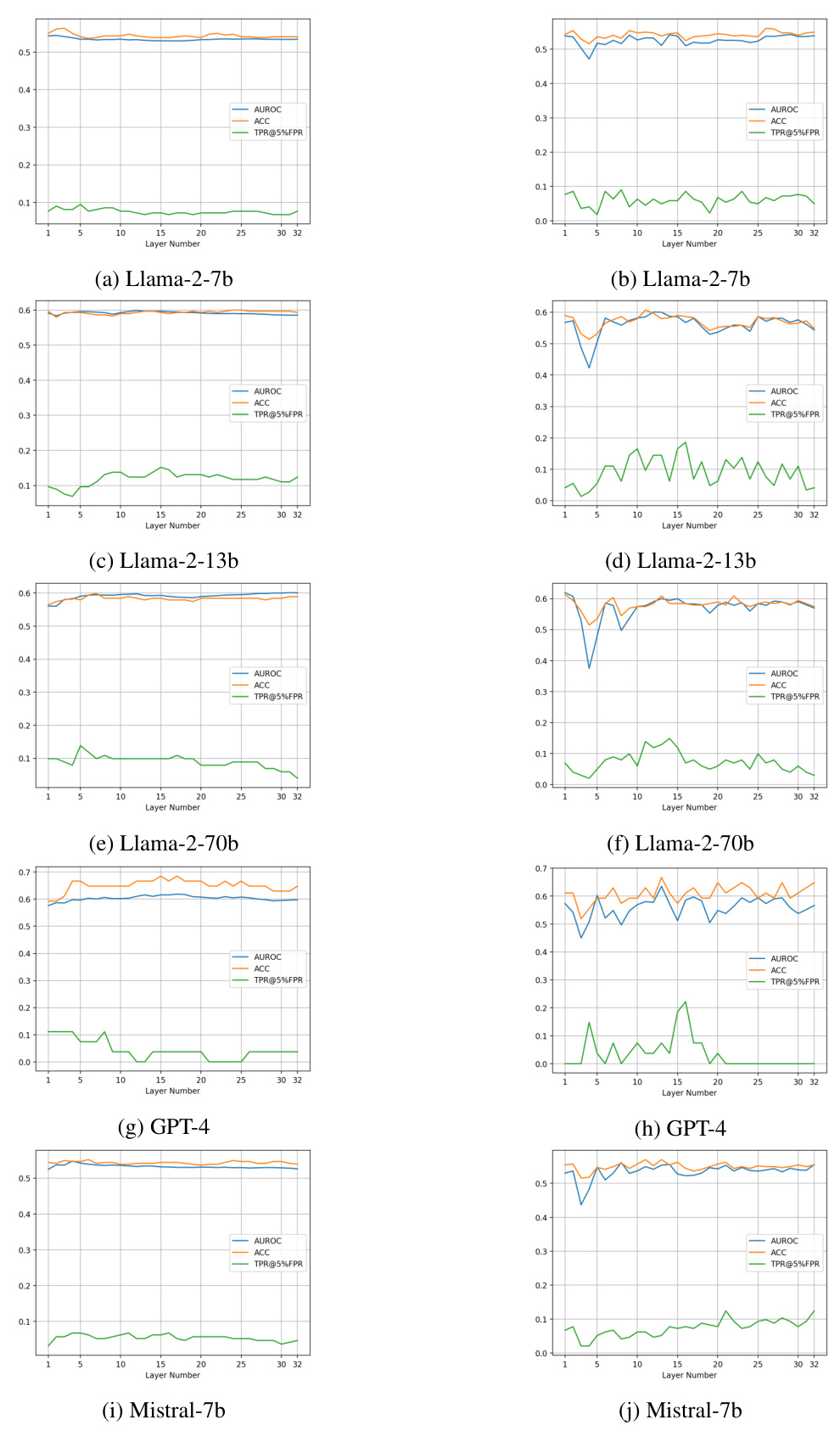

This figure shows the performance of the proposed hallucination detection method across different layers of a Llama-2-7B language model. The results are shown for different subset sizes of the dataset (5, 20, and 50 pairs of samples, as well as the full dataset). The plots illustrate the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC), Accuracy, and True Positive Rate at 5% False Positive Rate (TPR@5%FPR) for each layer. The consistency of the trends across different subset sizes suggests that a suitable layer for optimal performance can be efficiently selected using only a small subset of the data.

This figure shows the accuracy of hallucination detection across different layers of the Llama-2-7B language model using various sample sizes. The results demonstrate that consistent trends in performance emerge even with small sample sizes (5, 20, and 50 pairs). This suggests an efficient method for selecting the optimal layer for hallucination detection.

This figure shows a schematic of the proposed hallucination detection pipeline. It uses an LLM’s internal representations (hidden activations and attention kernel maps) to identify hallucinations. The process involves three steps: 1) obtaining hidden activations and attention maps from a single forward pass of the LLM; 2) performing eigenvalue analysis on these representations to calculate Hidden and Attention scores; 3) comparing the scores against a threshold to determine whether hallucinations are present. This approach avoids the need for multiple model responses or extensive external databases, making it efficient for real-time analysis.

More on tables

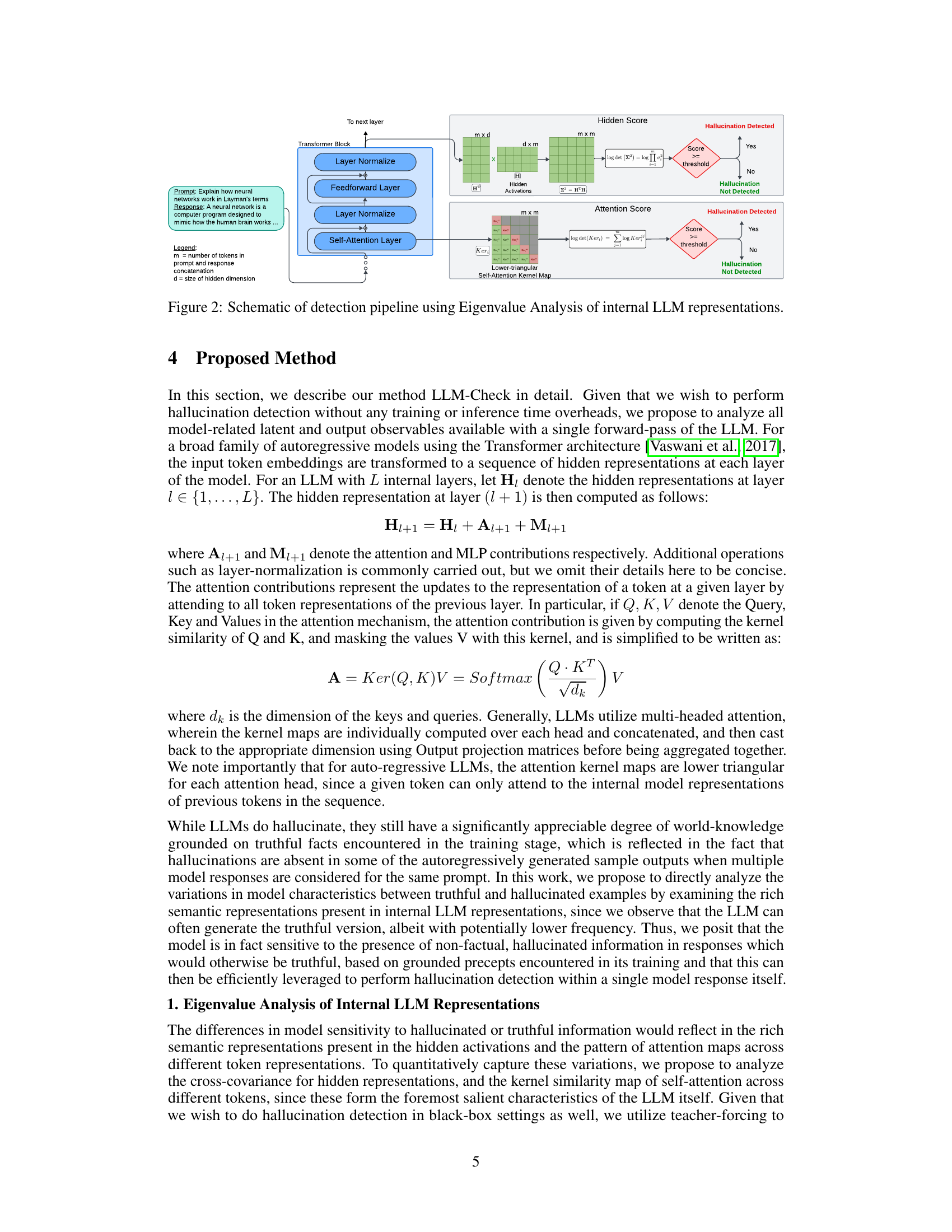

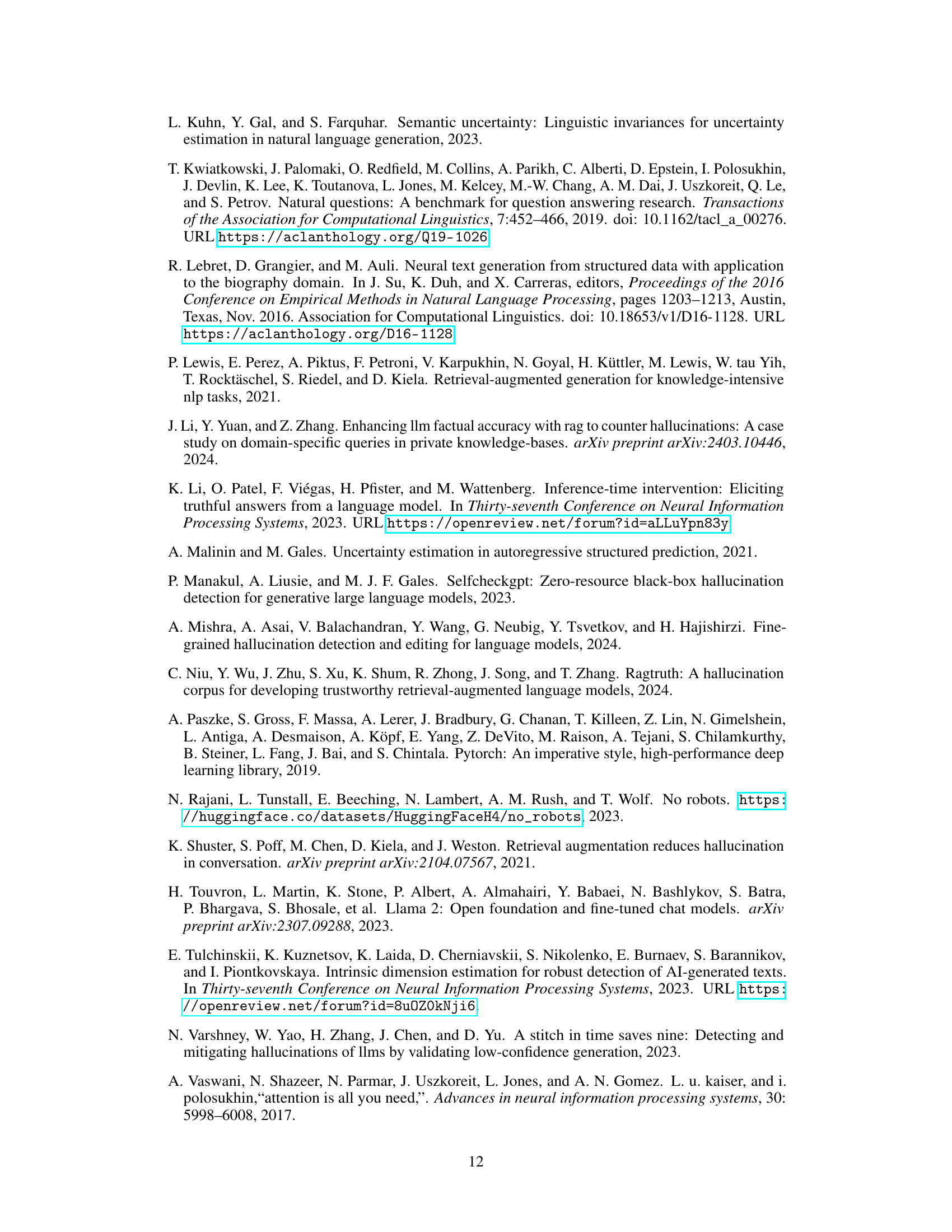

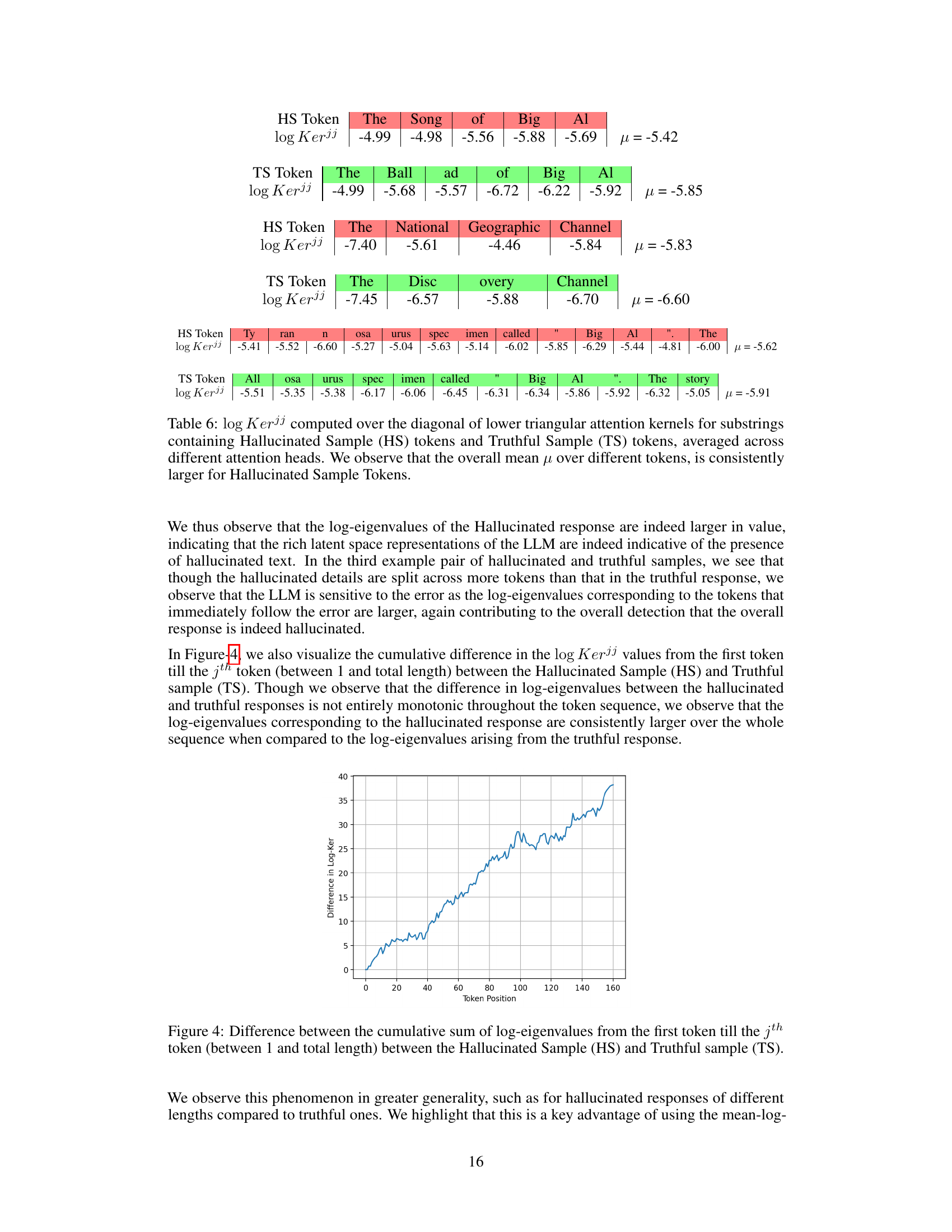

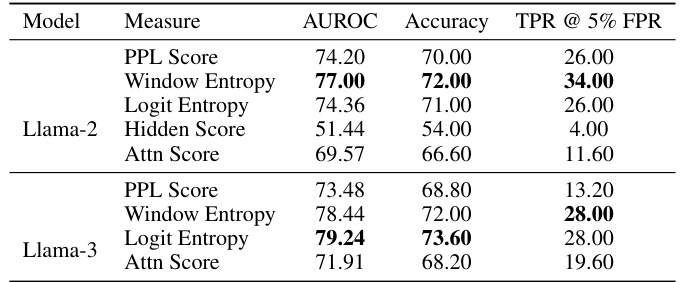

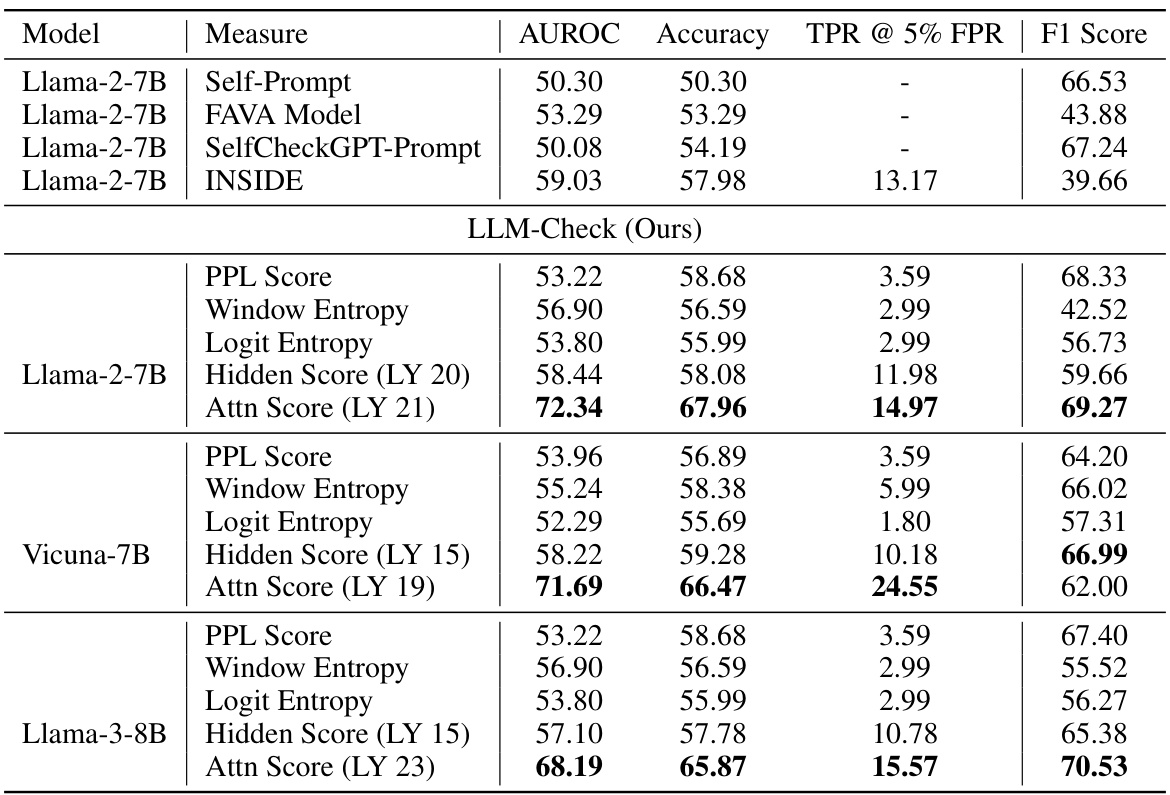

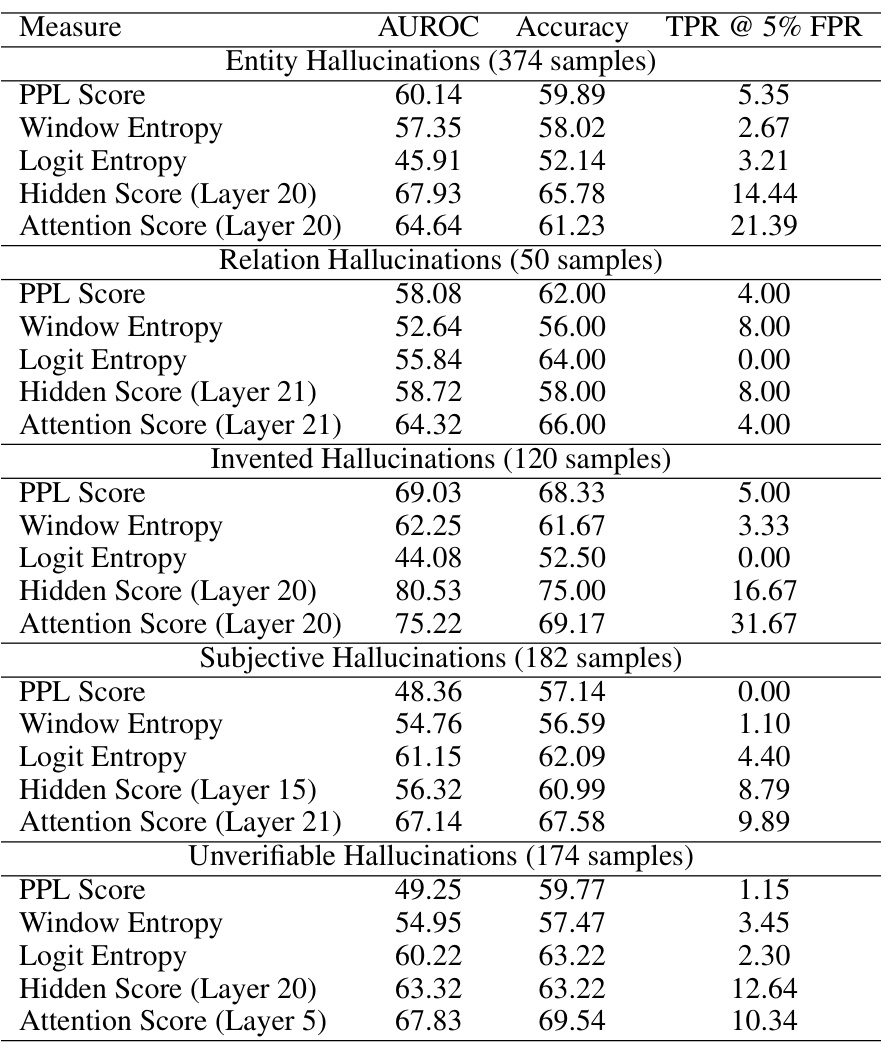

This table presents the results of hallucination detection experiments on the FAVA-Annotation dataset, focusing on scenarios without external references. It compares the performance of several methods, including the proposed LLM-Check and baselines such as Self-Prompt, FAVA Model, SelfCheckGPT-Prompt, and INSIDE, across different metrics: AUROC, Accuracy, TPR@5% FPR, and F1 Score. Note that for the baselines INSIDE and SelfCheckGPT-Prompt, multiple model responses generated by GPT-3 were used.

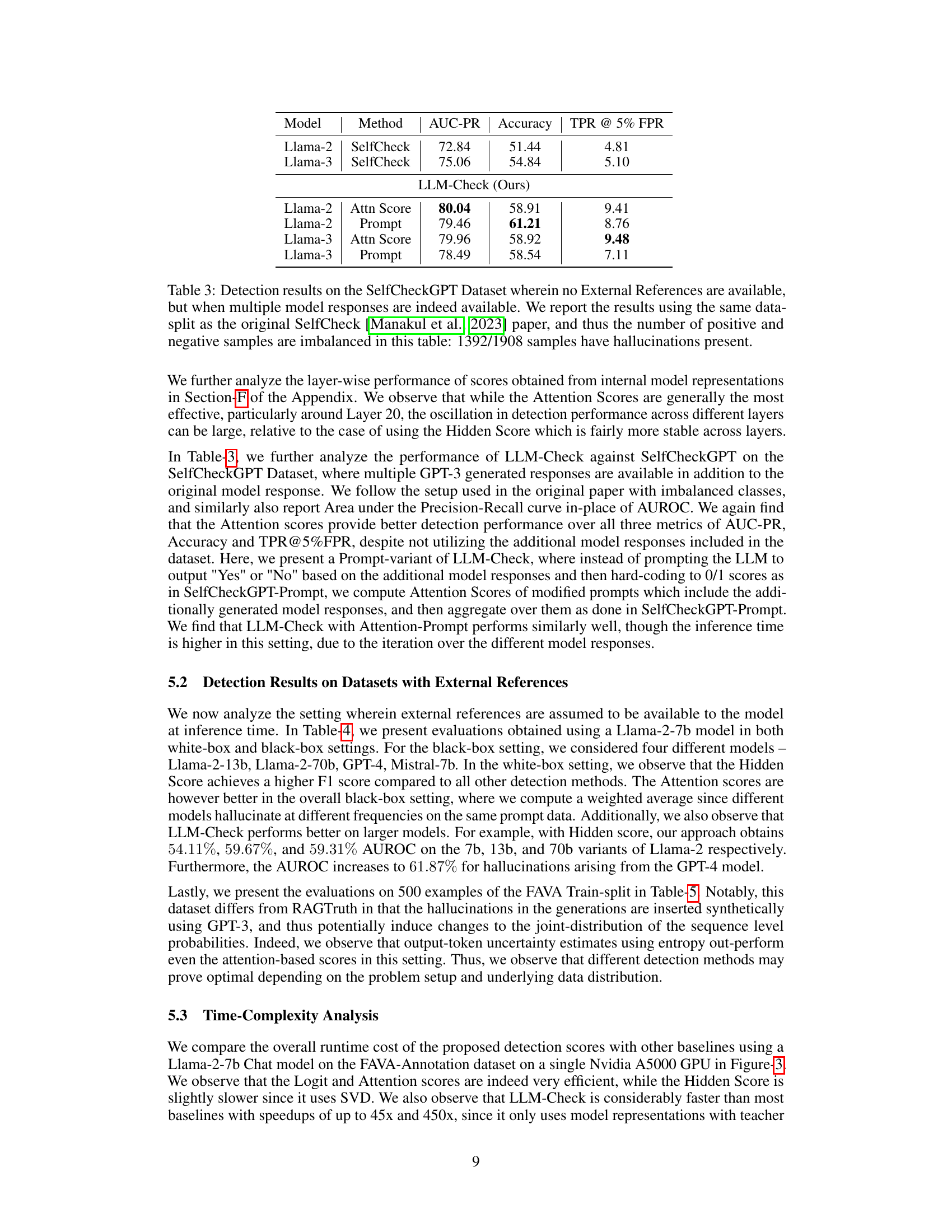

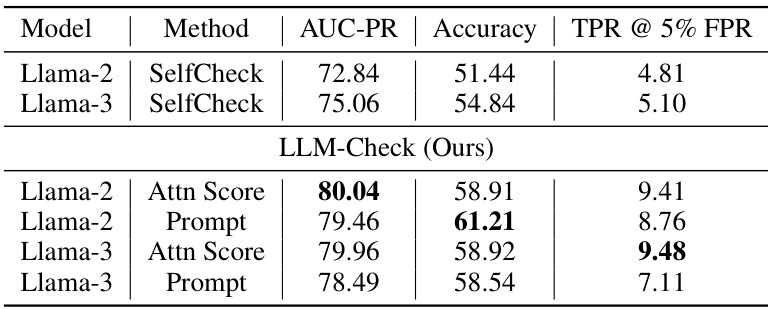

This table presents the results of hallucination detection experiments using the SelfCheckGPT dataset. Unlike previous tables, this experiment includes multiple model responses for each prompt, making it a different setting than the zero-resource settings of previous tables. The table shows that LLM-Check (the proposed method) performs very well compared to other baselines, despite the imbalanced dataset.

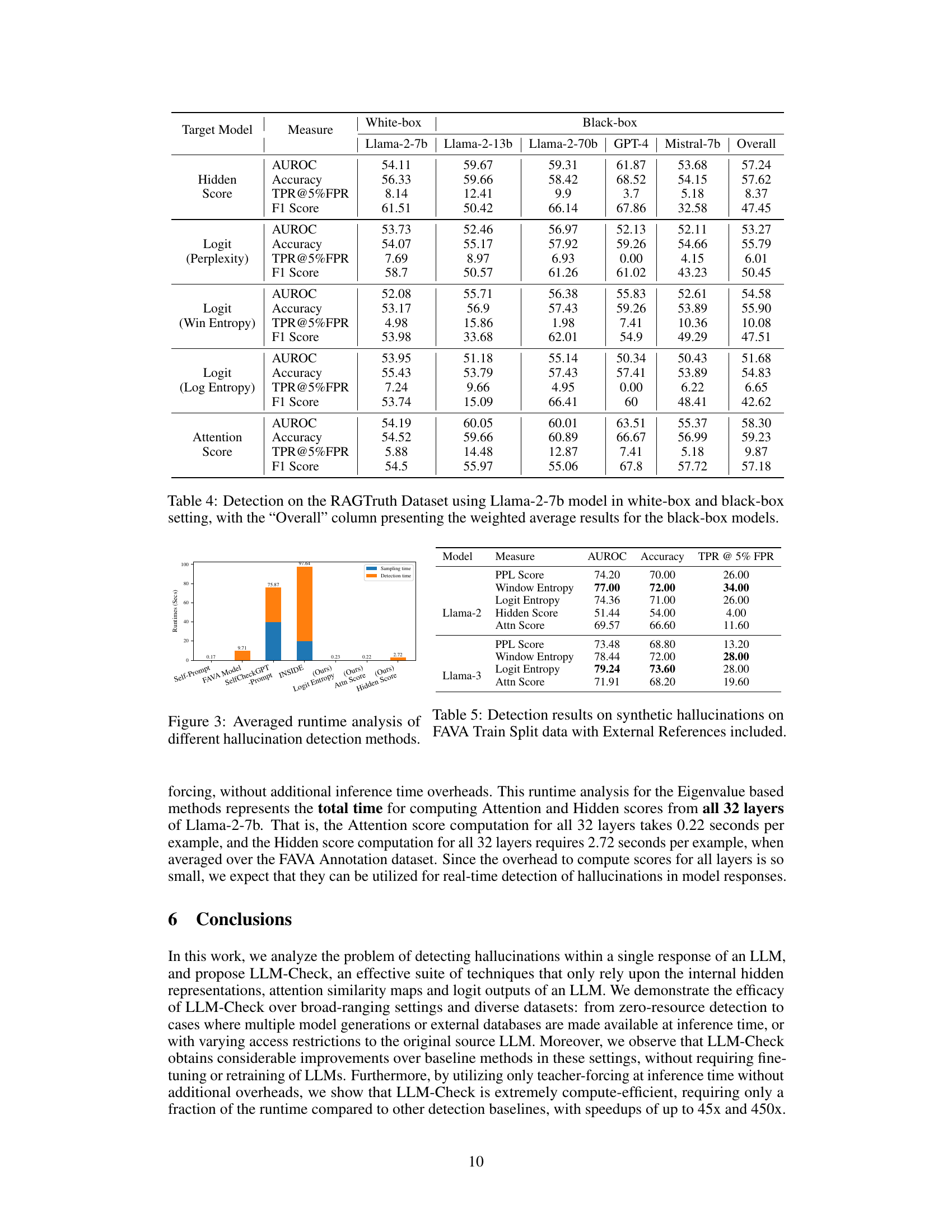

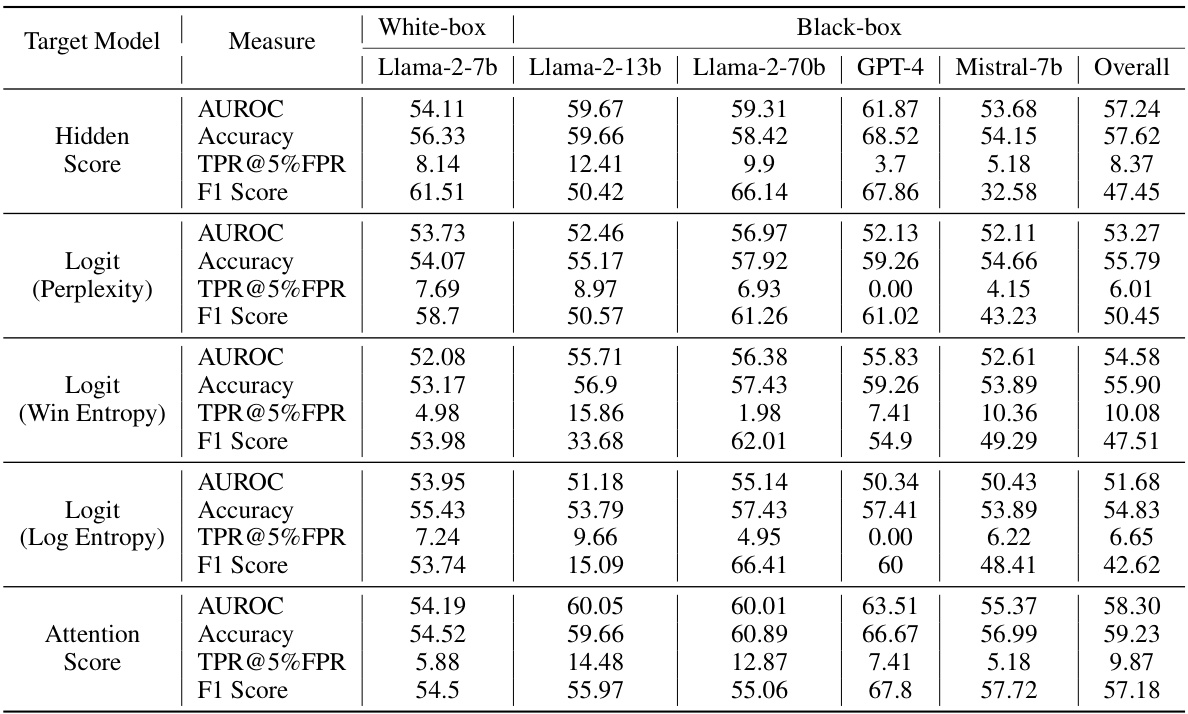

This table presents the results of hallucination detection experiments on the RAGTruth dataset using a Llama-2-7b model in both white-box (access to the internal model activations) and black-box (no access to internal model activations) settings. Several other LLMs were used for the black-box experiments (Llama-2-13b, Llama-2-70b, GPT-4, Mistral-7b). The table shows the AUROC, accuracy, TPR@5%FPR, and F1 score for different hallucination detection methods (Hidden Score, Logit (Perplexity), Logit (Win Entropy), Logit (Log Entropy), and Attention Score). The ‘Overall’ column provides the weighted average of the black-box model results.

This table presents the results of hallucination detection experiments conducted on the FAVA-Annotation dataset. The key characteristic of this dataset is the absence of external references. Several methods were tested, including the proposed LLM-Check and baseline techniques like SelfCheckGPT and INSIDE. For the baseline methods that use multiple model responses, the authors used multiple responses from GPT-3. The table shows AUROC, accuracy, True Positive Rate at 5% False Positive Rate (TPR@5%FPR), and F1 score for different models and metrics.

Full paper#