↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current image editing methods often require precise instructions or careful selection of reference components, limiting user creativity and convenience. This paper presents “imitative editing,” a new paradigm where users provide a reference image illustrating the desired outcome without specifying precise regions. This alleviates the need for complex instructions and enhances user experience.

MimicBrush, the proposed model, uses a self-supervised generative framework that leverages randomly selected video frames to automatically learn the semantic correspondence between source and reference images. It efficiently performs the edits with a feedforward network. Experiments show significant improvements over existing methods on a created benchmark, demonstrating the effectiveness and efficiency of imitative editing across diverse scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to image editing, offering a more intuitive and user-friendly way to achieve complex modifications. Its self-supervised training method is particularly valuable, reducing the need for extensive labeled data. The work also provides a new benchmark for evaluating imitative editing methods, fostering further research and development in this area. The results demonstrate the potential of this approach for various applications such as product design, fashion, and visual effects, making it highly relevant to researchers across multiple disciplines.

Visual Insights#

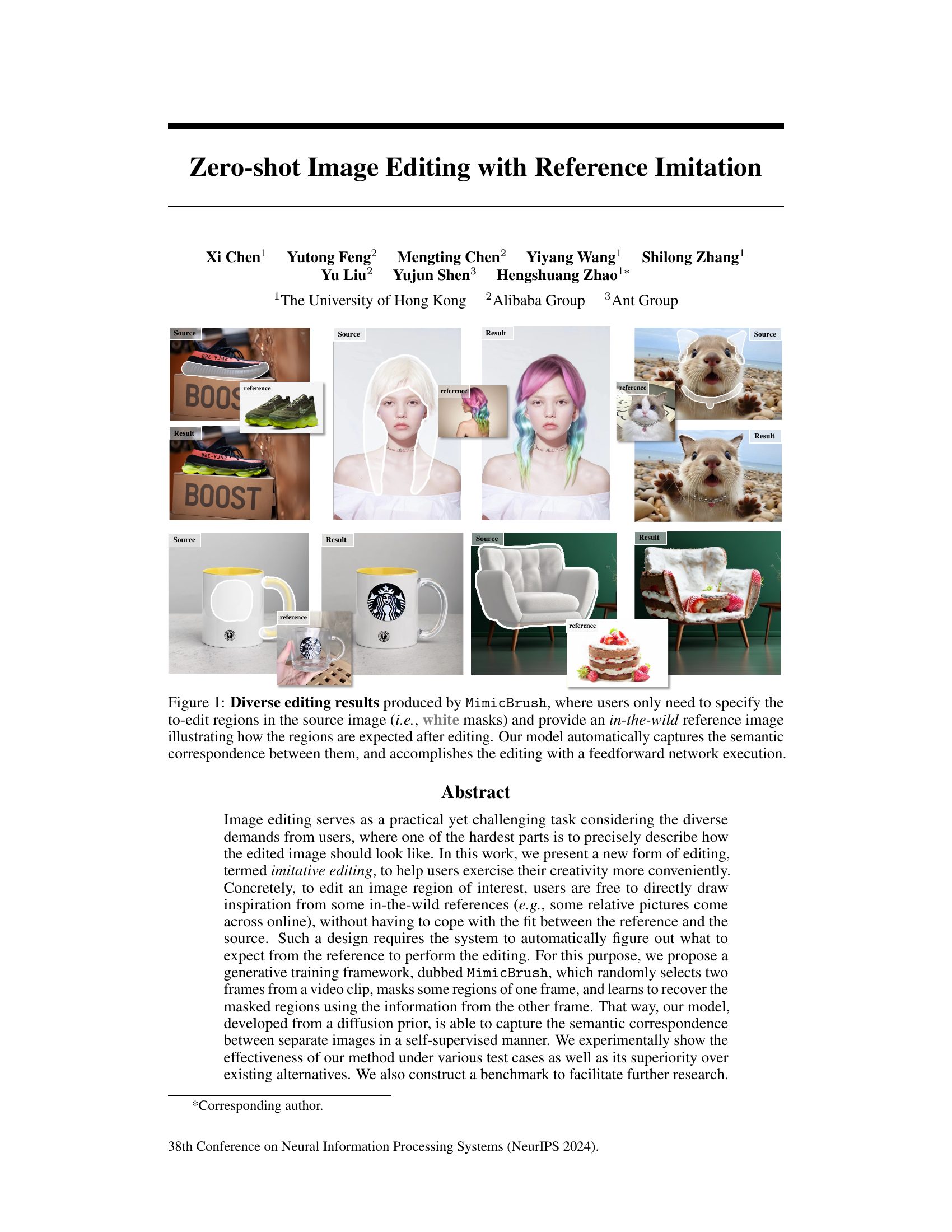

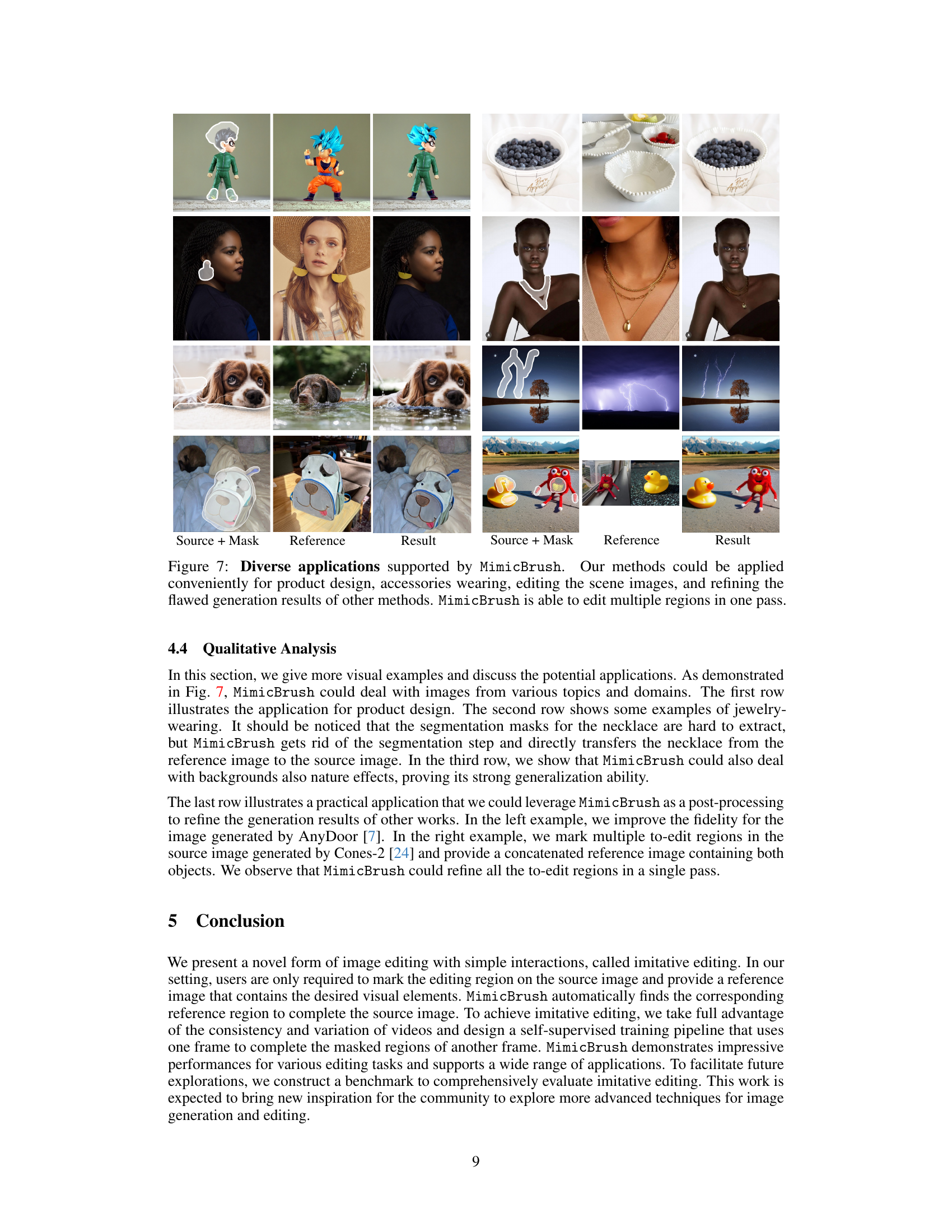

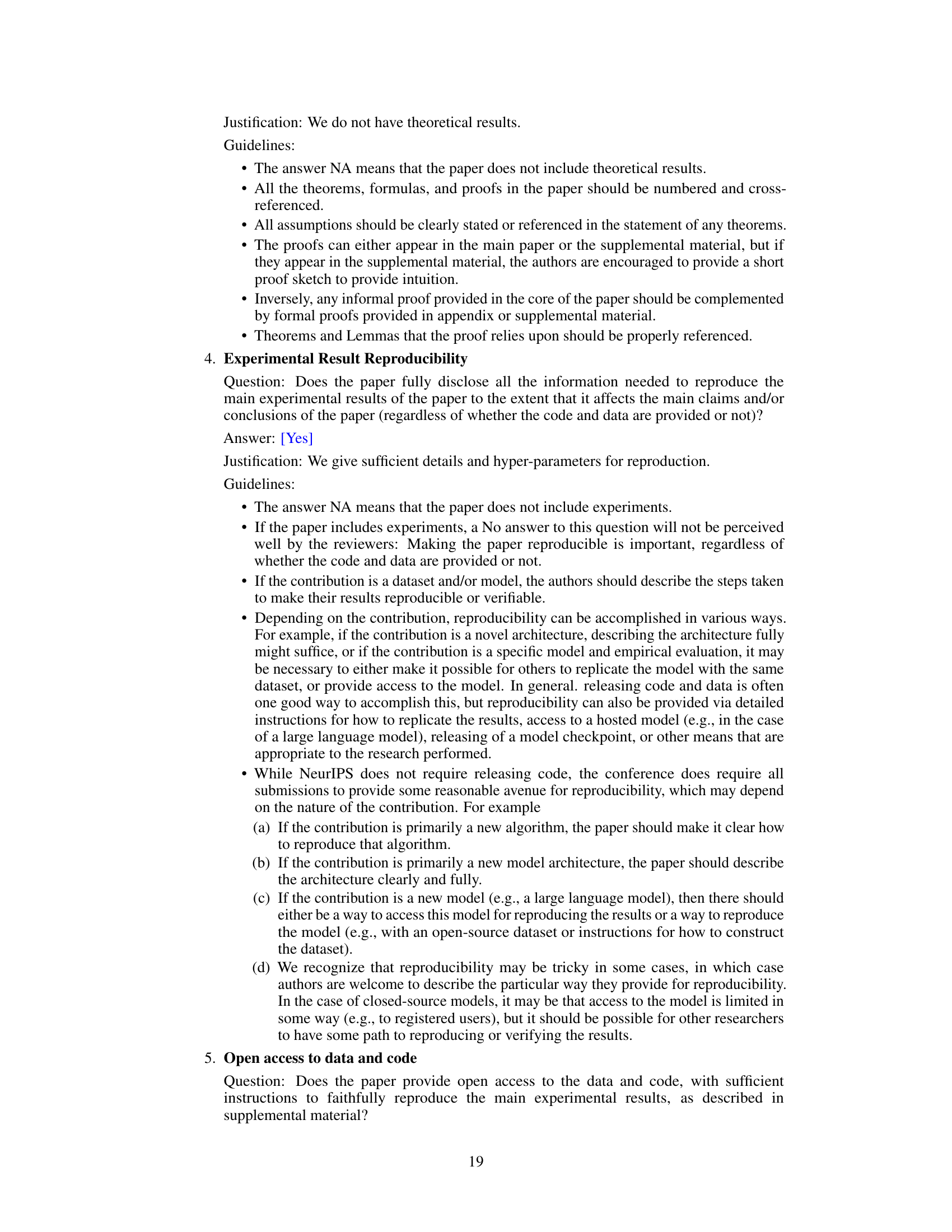

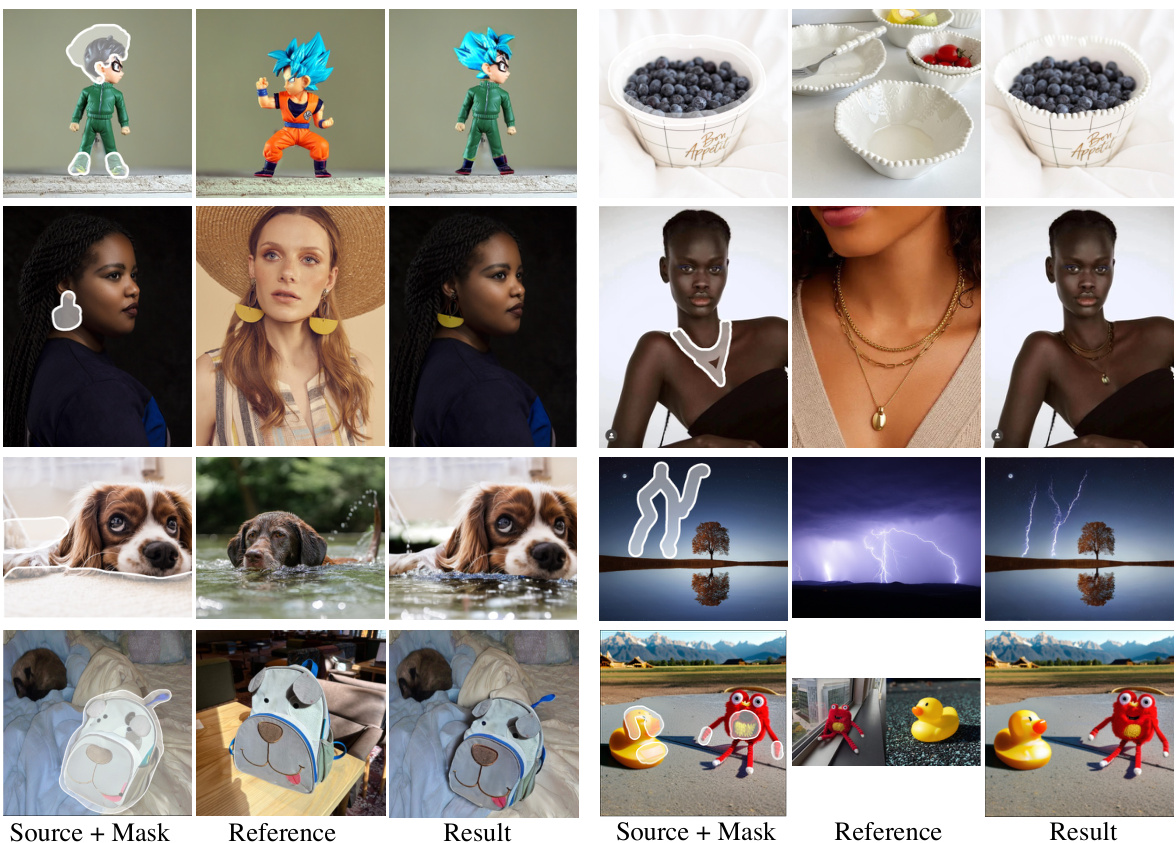

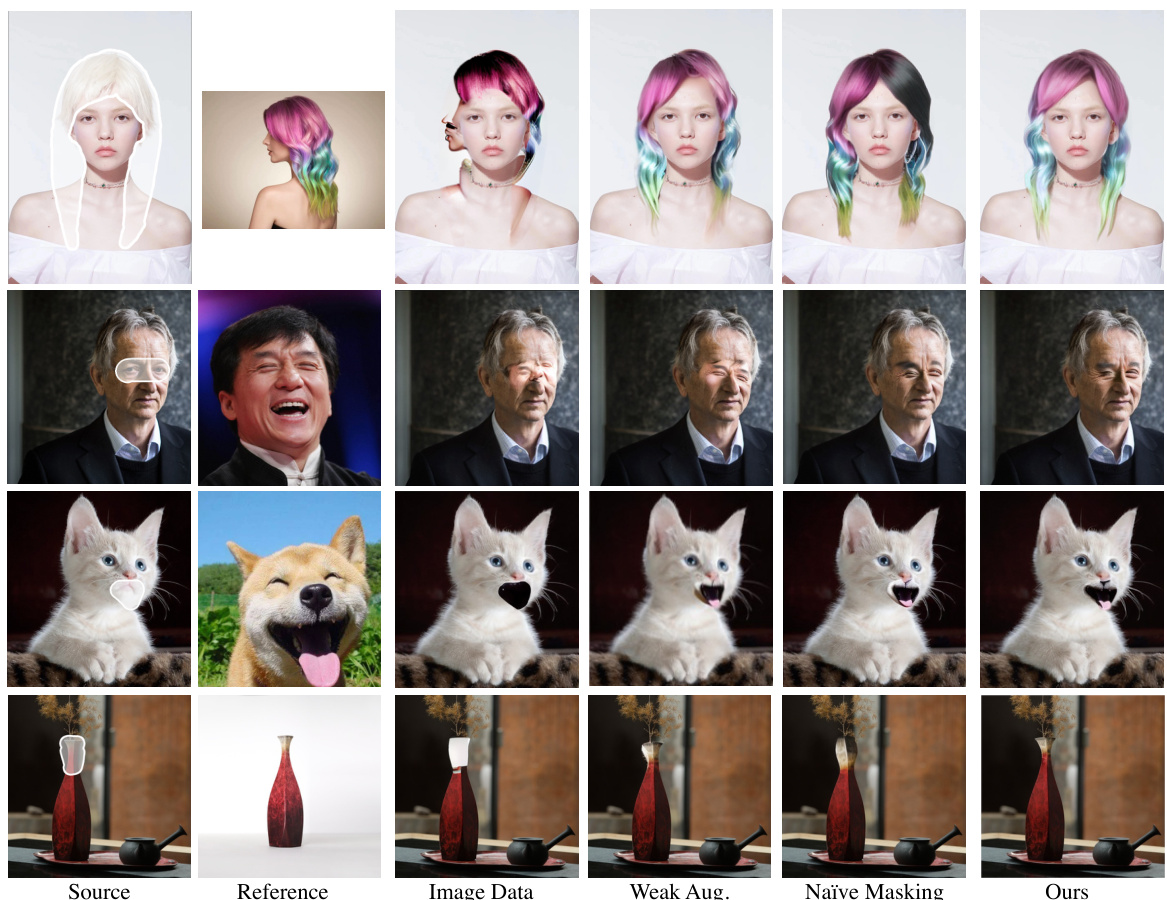

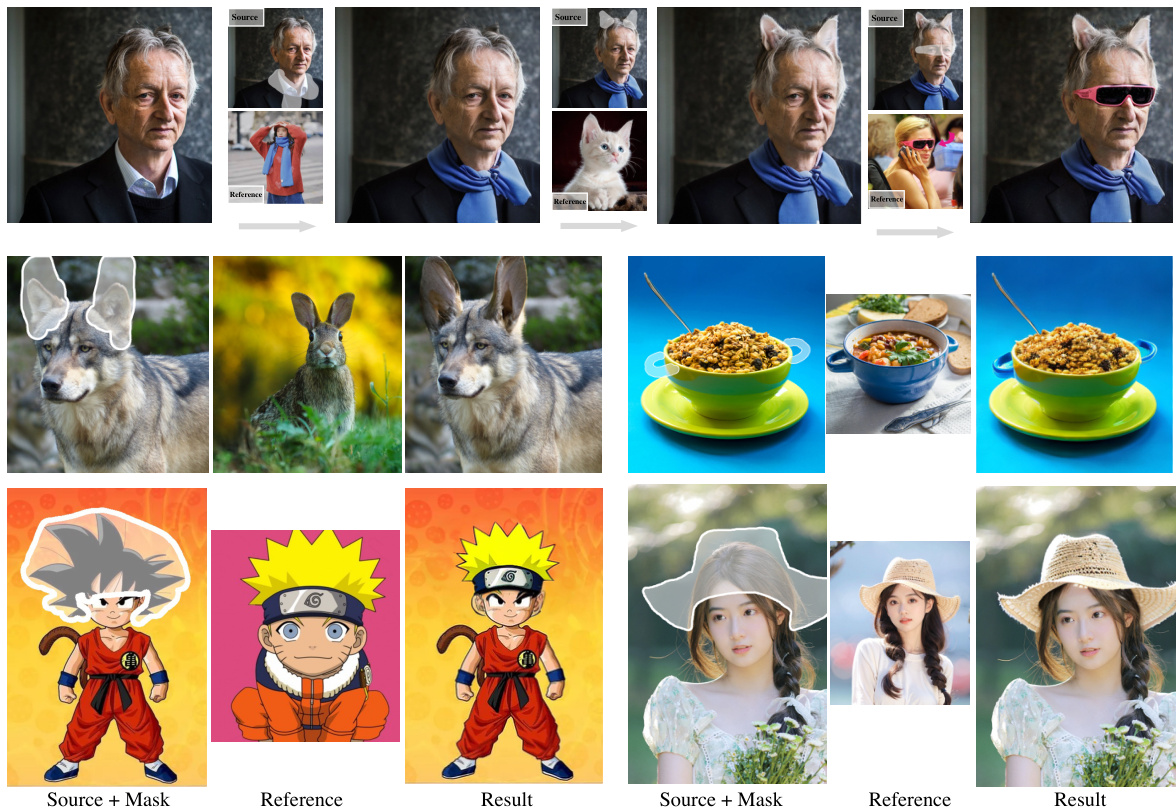

This figure showcases various examples of image editing results achieved using the MimicBrush model. Users simply indicate the areas to be modified (using white masks) and provide a sample reference image. The model automatically identifies the semantic correspondence between the source and reference images and performs the edit in a single forward pass. This demonstrates the model’s capability to handle diverse editing tasks without explicit instructions.

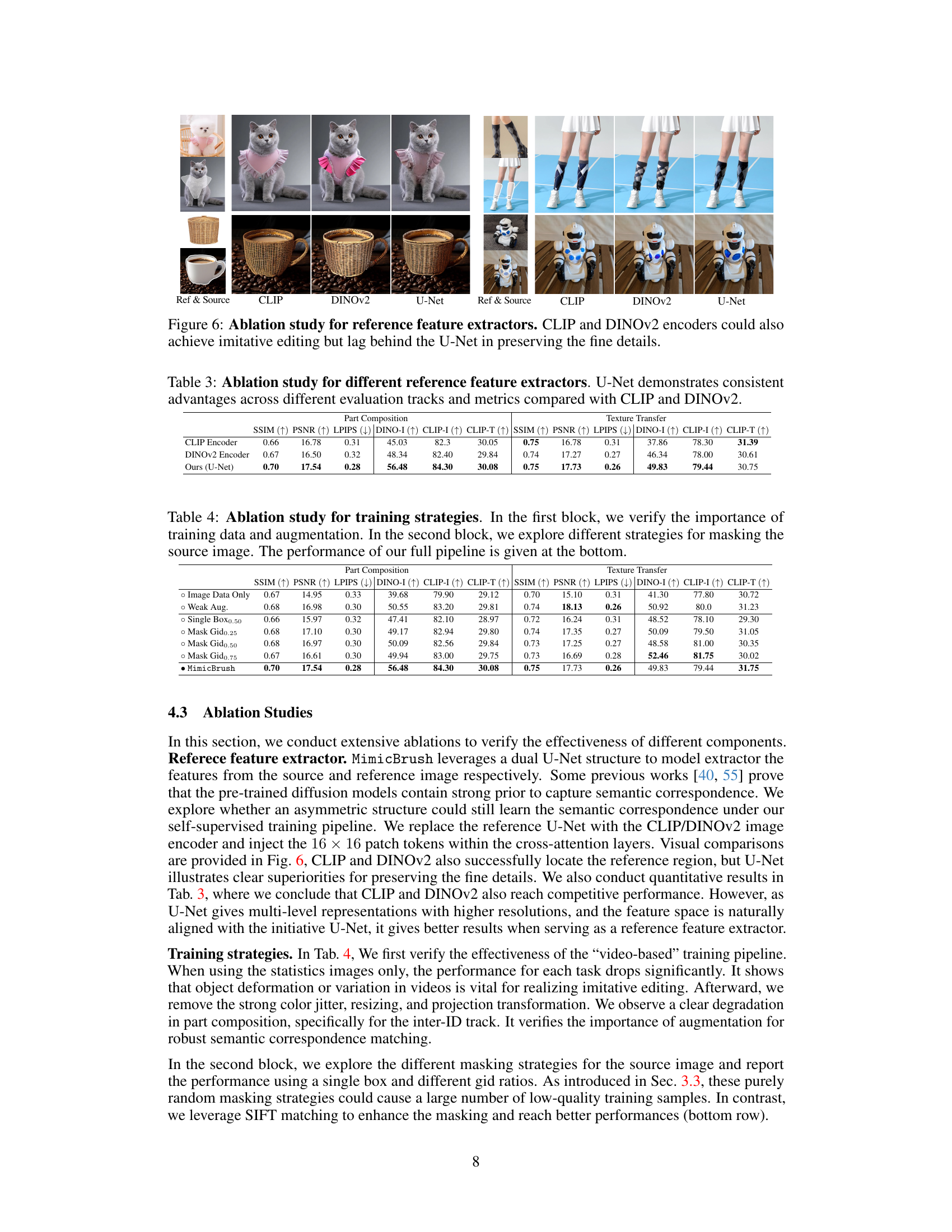

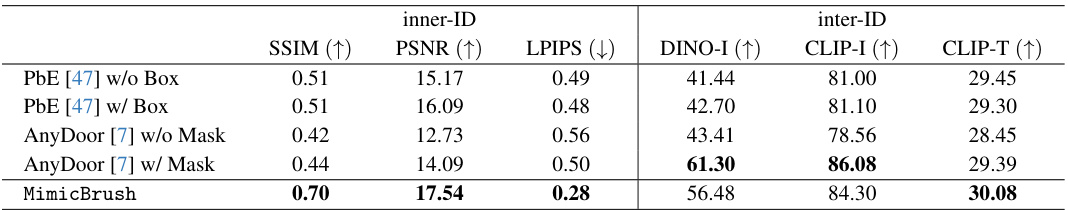

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different image editing methods on a benchmark designed for part composition tasks. The benchmark includes two tracks: inner-ID (using images from the same object) and inter-ID (using images from different objects). The table shows the performance of each method based on SSIM, PSNR, LPIPS scores, and image/text similarity using DINO and CLIP models. MimicBrush outperforms other methods across all metrics on both tracks.

In-depth insights#

Ref. Imitation Edit#

The concept of “Ref. Imitation Edit” in a research paper likely refers to an image editing technique that leverages reference images for guidance. It suggests a system where users provide a source image needing edits and a reference image showing the desired result. The core innovation would be the model’s ability to automatically learn the semantic correspondence between the source and reference, transferring visual characteristics from the reference to the source, even if the objects or scenes are not identical. This implies a self-supervised learning paradigm, where the model learns the mapping between different image states without explicit paired data. A key challenge is robustly handling variations in pose, lighting, and object appearance between the source and reference images. Successful implementation could lead to a more intuitive and user-friendly image editing experience, by eliminating the need for precise textual or mask-based instructions. The focus is likely on achieving high-fidelity results, seamlessly blending edited regions with their surroundings, which is a significant advancement compared to techniques relying solely on text or limited mask information.

MimicBrush Framework#

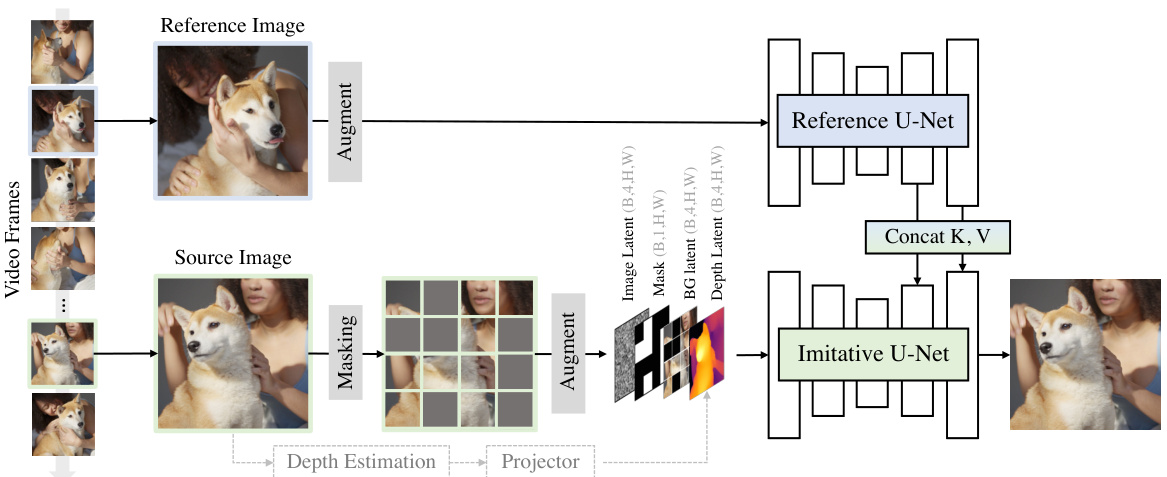

The MimicBrush framework presents a novel approach to zero-shot image editing by leveraging reference imitation. Its core innovation lies in its ability to learn semantic correspondences between a source image and a reference image without explicit masks or text prompts, simplifying user interaction. This is achieved through a self-supervised training process using video clips, where two frames are randomly selected, one masked to serve as the source image and the other as the reference. The dual U-Net architecture within MimicBrush cleverly extracts and integrates features from both images, enabling the model to automatically determine which region of the reference should be copied, allowing for natural-looking blends and contextual understanding. The framework’s self-supervised learning removes the need for manual object segmentation in training, making the process more scalable. Finally, the model integrates depth information for more refined shape control during the editing process. MimicBrush significantly advances zero-shot image editing capabilities by allowing effortless editing based solely on visual reference, thereby expanding creative possibilities and simplifying image manipulation.

Self-Supervised Training#

Self-supervised learning is a powerful technique for training deep learning models, especially when labeled data is scarce or expensive. In the context of image editing, a self-supervised approach can leverage the inherent structure and redundancy within image datasets to learn meaningful representations without explicit human annotations. A common strategy involves creating pretext tasks, such as predicting masked image regions or reconstructing image patches from noisy inputs. These tasks force the model to learn rich feature representations that capture the underlying semantics of the image data. The key advantage is the ability to use large unlabeled datasets for training, resulting in models that are more robust and generalize better than those trained only on limited labeled data. A well-designed pretext task is crucial; it must be sufficiently challenging to encourage the model to learn useful features while being solvable enough to avoid trivial solutions. The model’s success ultimately depends on the effectiveness of the pretext task in extracting meaningful information from the raw image data. The choice of architecture (e.g., convolutional neural networks, transformers) and training strategies (e.g., contrastive learning, generative modeling) also play a significant role in determining the overall performance. Careful evaluation is necessary to ensure the learned representations are indeed useful for the downstream image editing task, avoiding overfitting to the pretext task and ensuring effective transfer to the actual editing task.

Benchmark & Results#

A robust benchmark is crucial for evaluating image editing models. It should encompass diverse scenarios and metrics to thoroughly assess performance. Quantitative metrics, like SSIM, PSNR, and LPIPS, can objectively measure image fidelity, but subjective evaluation is also needed, considering the artistic nature of image editing. A comprehensive benchmark would include both intra- and inter-category comparisons, examining how well the model generalizes across different image types and styles. Qualitative results, including visual examples, are essential for showcasing the model’s capabilities in handling complex editing tasks and its ability to produce aesthetically pleasing outputs. The choice of metrics must align with the task. While quantitative metrics are useful for comparing models, qualitative analysis, perhaps via user studies, is crucial for gauging the perceptual quality and overall user satisfaction with the edited images. Therefore, a solid benchmark provides both objective measures and subjective assessments, offering a complete picture of model performance.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore enhancing MimicBrush’s capabilities to handle more complex editing tasks, such as seamless integration of multiple reference images or editing across drastically different visual styles. Addressing limitations in handling extremely small target regions or ambiguous references remains crucial. Investigating the use of alternative architectures, like transformers, could improve performance and efficiency. A deeper exploration of the model’s underlying semantic understanding, possibly through incorporating explicit knowledge representations, could lead to more robust and controlled editing outcomes. Furthermore, extending the benchmark to encompass a wider variety of editing tasks and datasets is vital to ensure broader applicability and facilitate future comparisons. Finally, research could focus on applying MimicBrush to related domains, such as video editing or 3D model manipulation, to explore its potential for more immersive and interactive content creation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

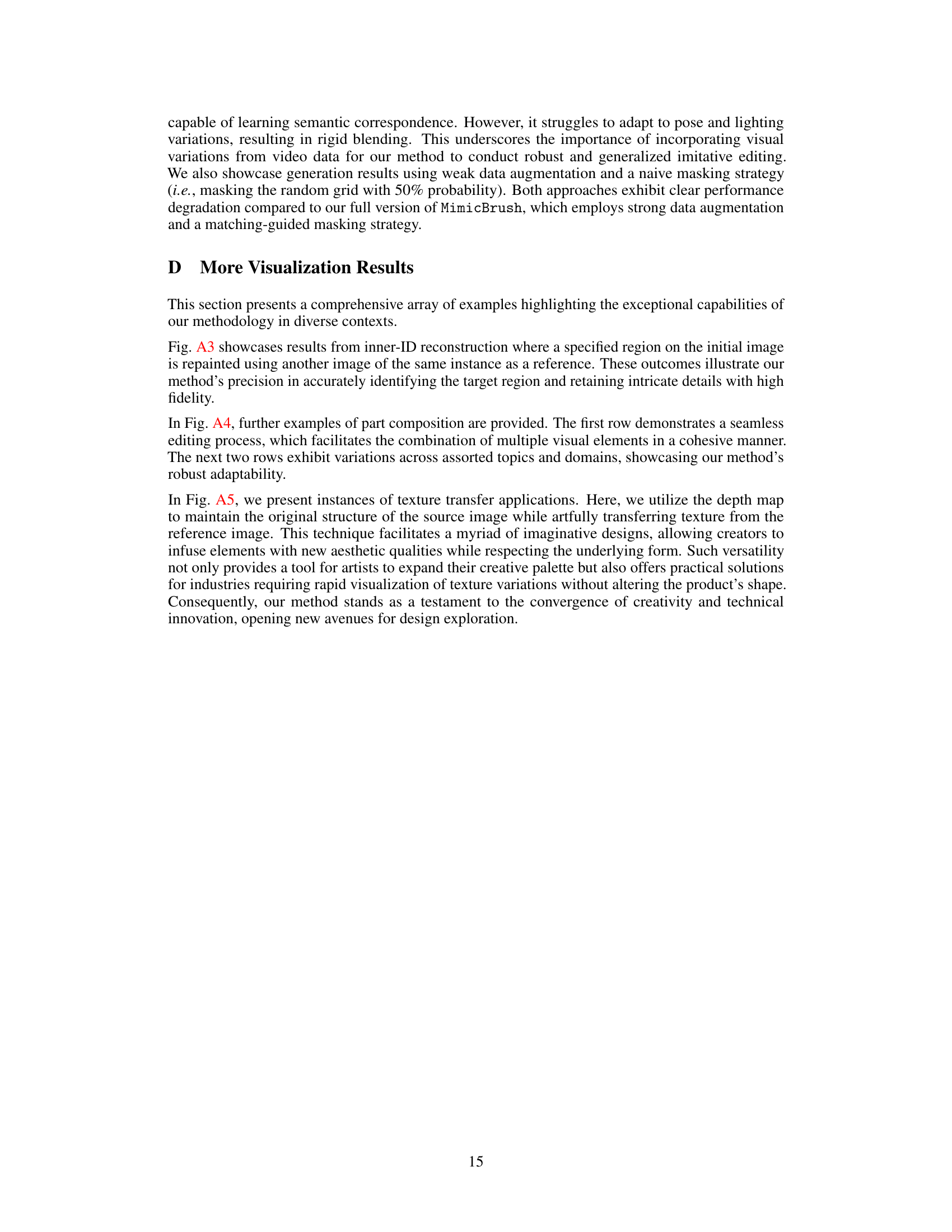

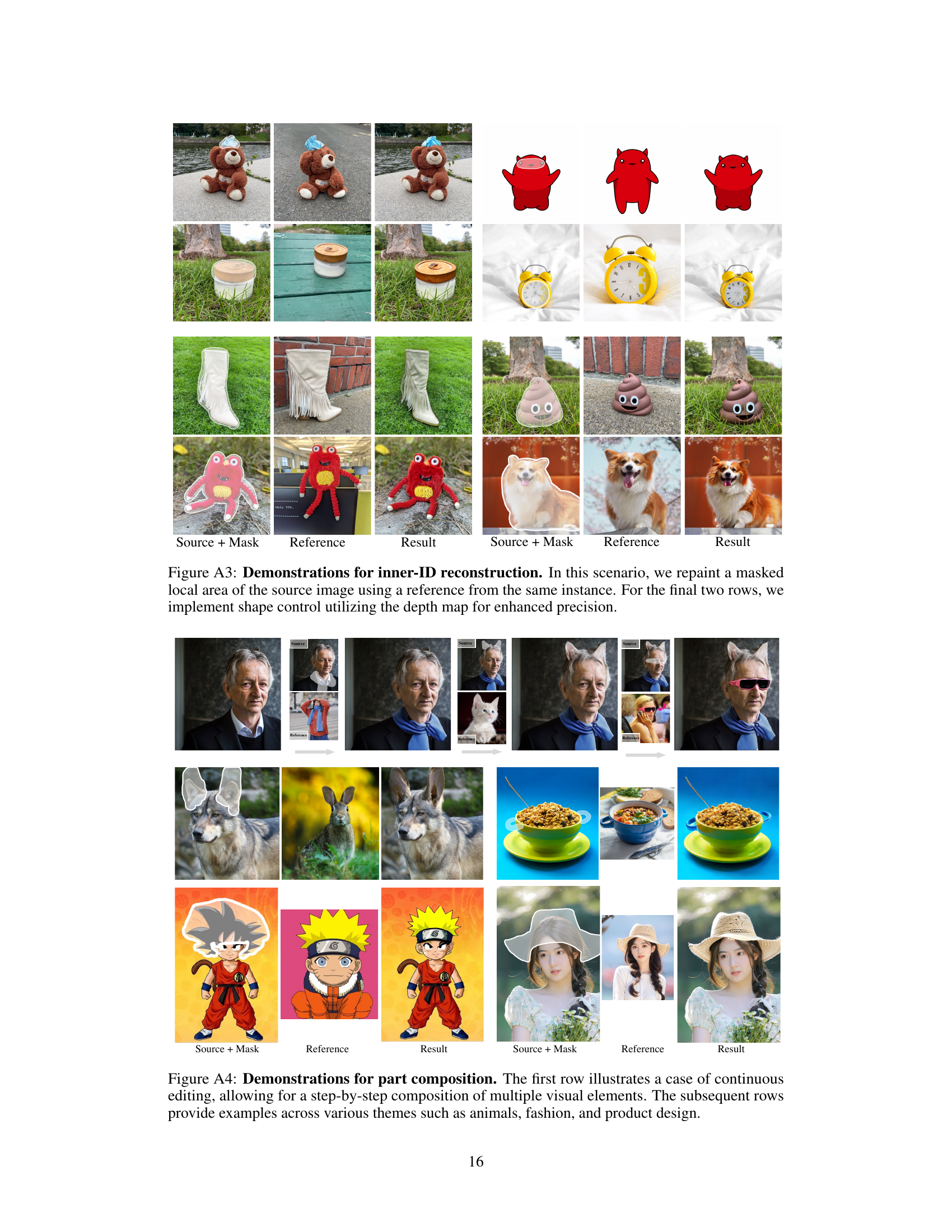

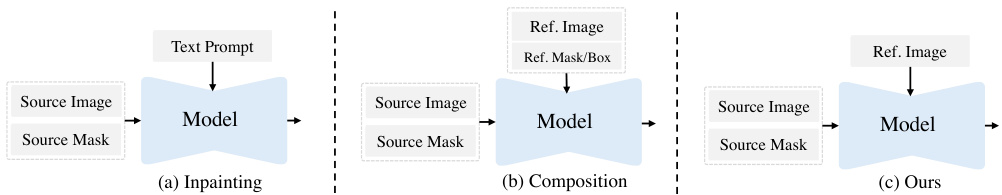

This figure compares three different image editing pipelines: inpainting, composition, and the proposed MimicBrush method. Inpainting uses text prompts and source image masks to guide the generation of edits. Composition methods use a reference image and mask to specify the region for replacement. MimicBrush takes only a reference image and source mask, automatically identifying the corresponding regions and performing the editing.

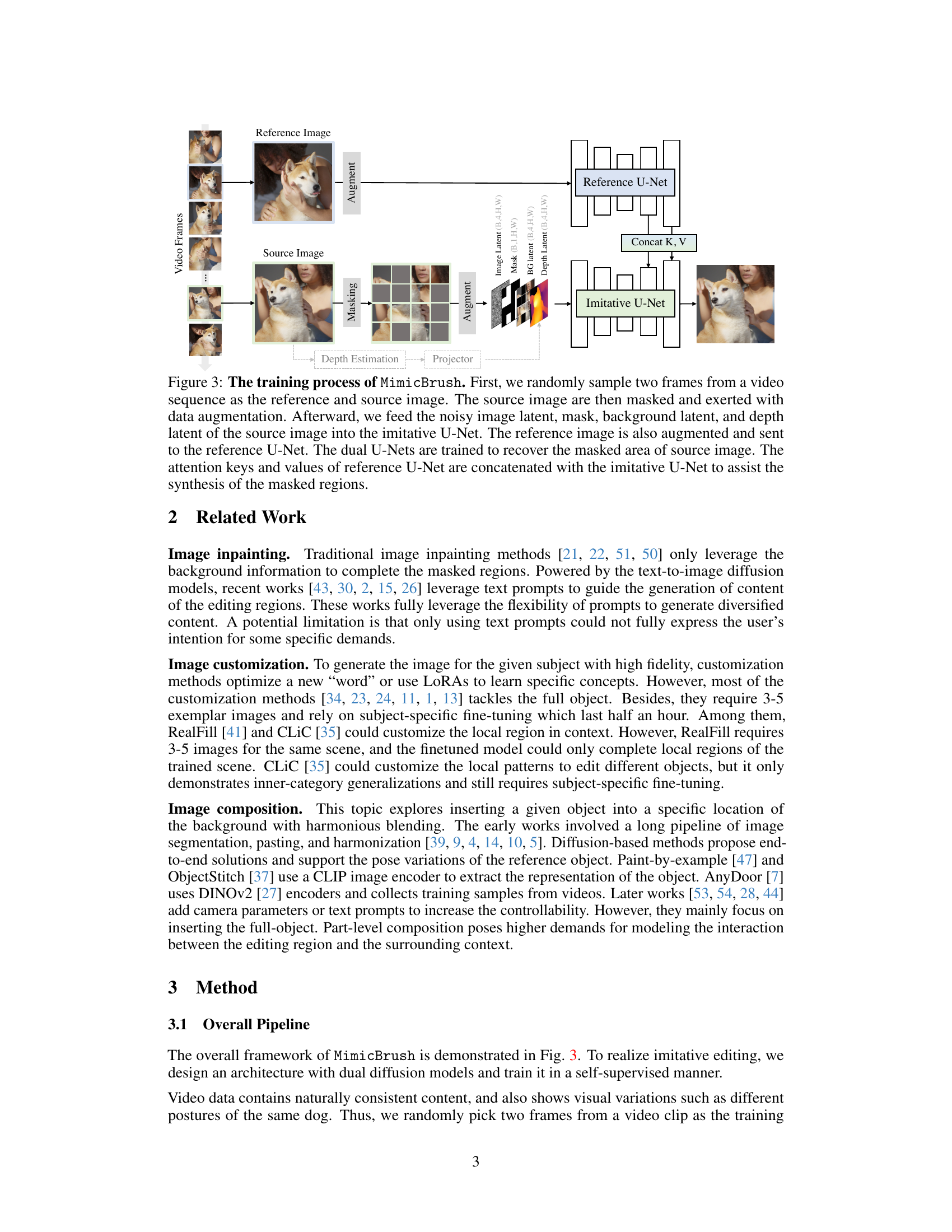

This figure illustrates the training process of the MimicBrush model. It shows how two frames from a video are used: one as a source image (masked and augmented) and the other as a reference image (also augmented). Both images are fed into their respective U-Nets (Imitative and Reference). The keys and values from the Reference U-Net are then concatenated with the Imitative U-Net to help reconstruct the masked region of the source image. Depth estimation is used to improve the accuracy of reconstruction, but is optional.

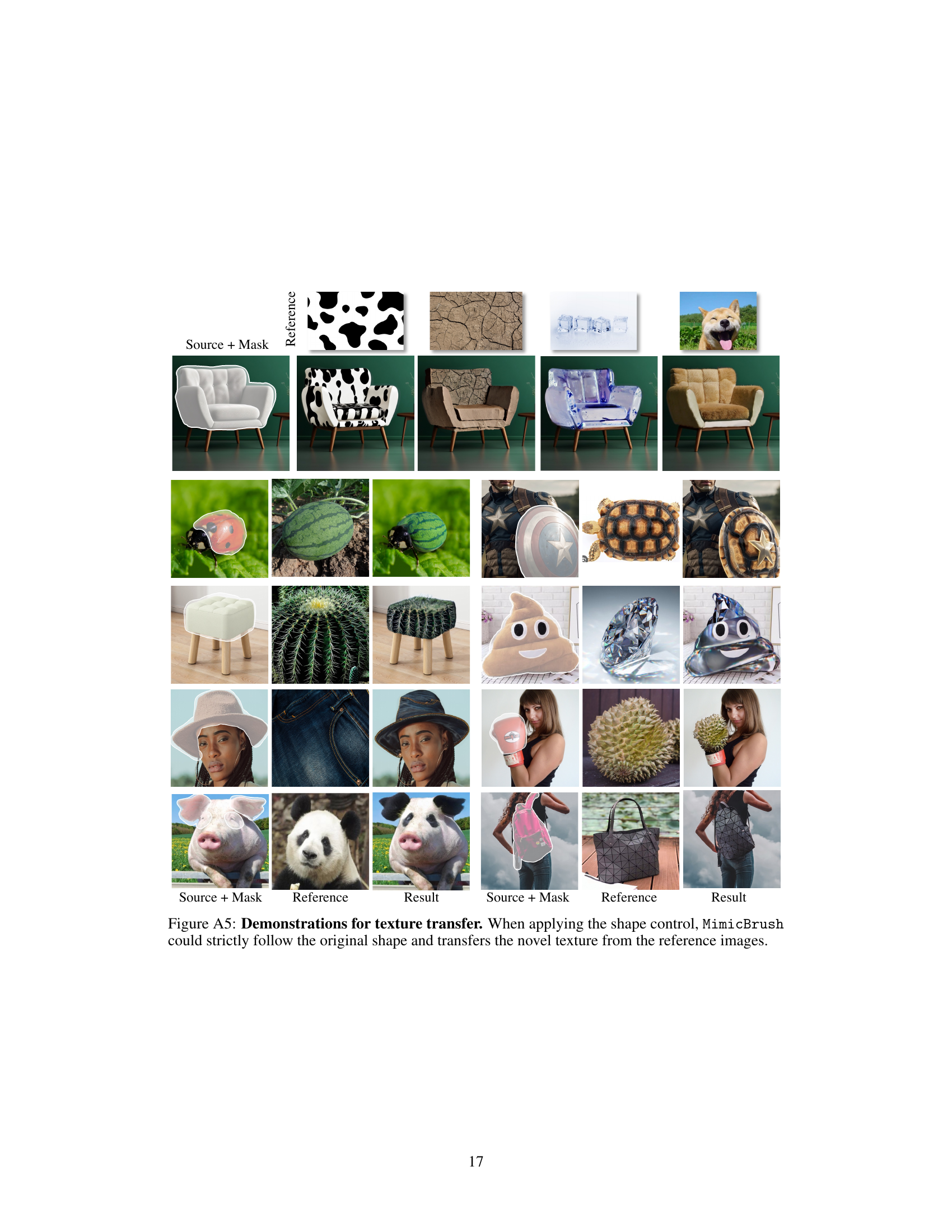

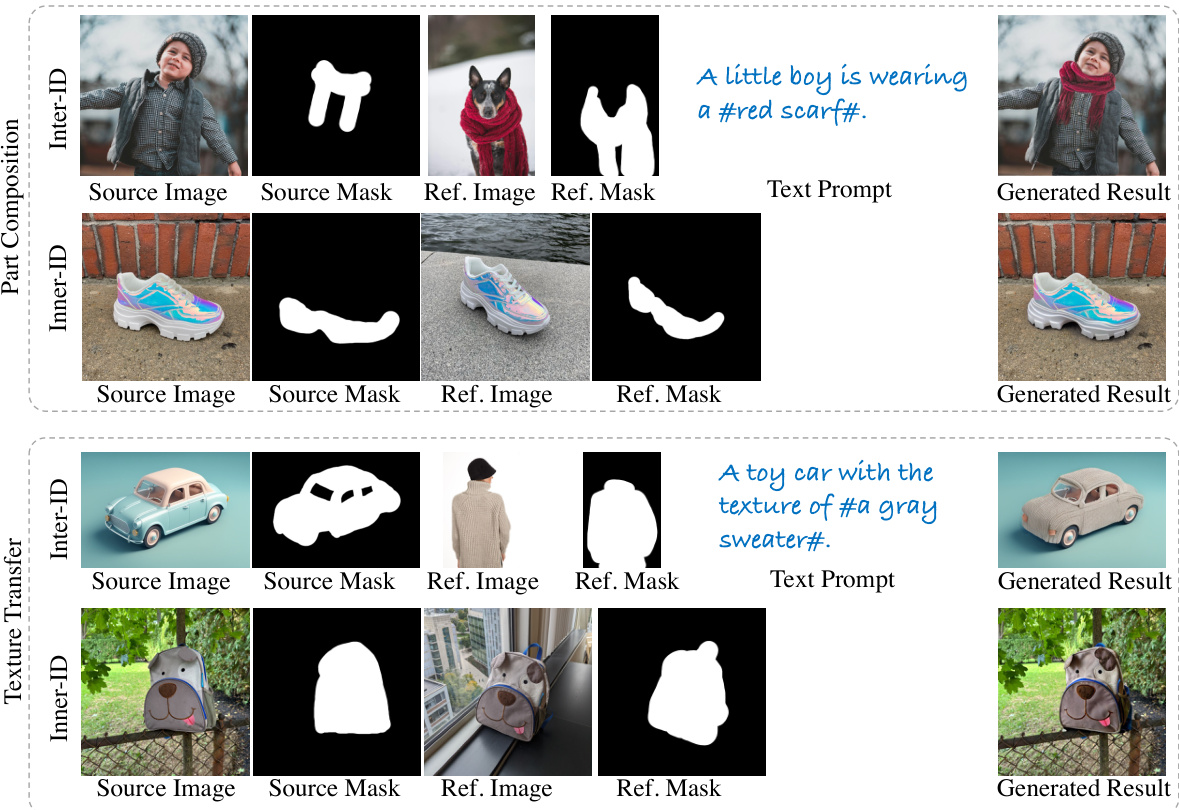

This figure shows example results for the benchmark used to evaluate the MimicBrush model. It illustrates the two main tasks: part composition and texture transfer. Each task is further divided into two tracks: Inter-ID (comparing different objects) and Inner-ID (comparing variations of the same object). The figure displays example source images, reference images, masks, and the metrics used for evaluation (SSIM, PSNR, LPIPS, DINO image similarity, CLIP image similarity, and CLIP text similarity).

This figure presents a qualitative comparison of MimicBrush against other image editing methods (Firefly, Paint-by-Example, and AnyDoor) on several example images. It highlights that MimicBrush achieves superior results in terms of image fidelity and harmony, even though the competing methods require additional user inputs (detailed text prompts or manually defined reference regions).

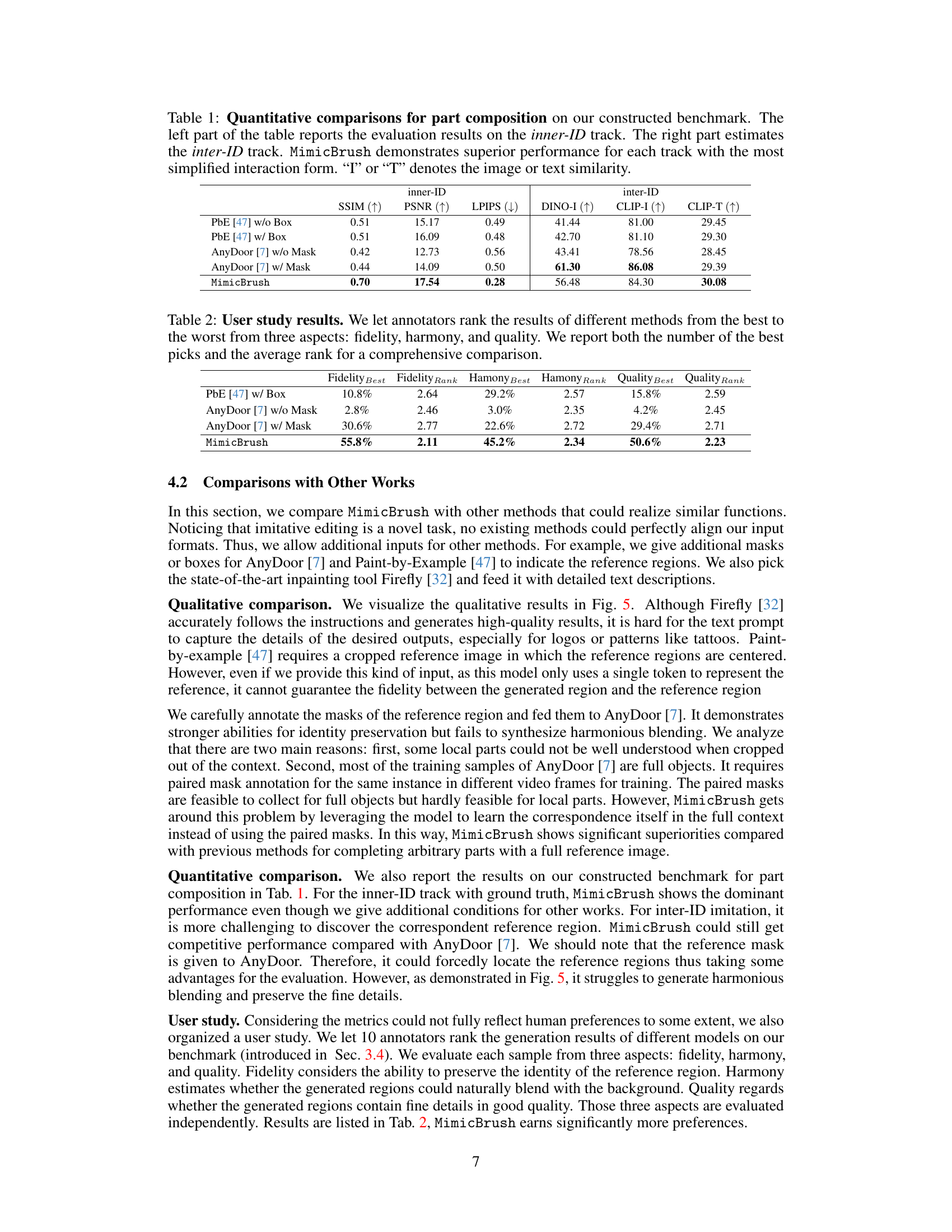

This ablation study compares the performance of three different reference feature extractors: CLIP, DINOv2, and a U-Net, in the task of imitative image editing. The results show that while CLIP and DINOv2 can achieve imitative editing, the U-Net generally produces superior results, particularly in preserving fine details in the edited image regions. The figure visually demonstrates this difference by showing example edits performed using each feature extractor.

This figure showcases the versatility of MimicBrush across various applications. It demonstrates the ability to edit product designs (e.g., replacing textures on shoes), modify accessories in fashion images (e.g., swapping earrings or necklaces), enhance scene images (e.g., changing lighting or adding elements), and correct flaws in other image editing results. Importantly, the model can efficiently edit multiple regions simultaneously.

This figure shows examples of the benchmark datasets used to evaluate the MimicBrush model. It highlights the two main tasks: part composition and texture transfer. Each task is further divided into ‘Inter-ID’ and ‘Inner-ID’ subtasks, representing different levels of difficulty and data characteristics. The figure illustrates the input images (source, reference), masks, and associated text prompts, along with the evaluation metrics (SSIM, PSNR, LPIPS) and whether ground truth was available. This provides a clear overview of how the benchmark is structured and the type of data used to train and test the model.

This figure shows qualitative ablation studies for different training strategies used in the MimicBrush model. The results demonstrate the model’s performance when trained under various conditions: using only image data, applying weak augmentations, and using naive masking. A comparison with the results of the full model is also included, highlighting the positive impact of a robust training strategy that leverages visual variations and well-crafted masking.

This figure shows several examples of image editing results using the MimicBrush model. Users only need to specify the areas to be edited (using white masks) in the source image and provide a reference image showing the desired result. The model automatically identifies the correspondence between the source and reference images and performs the edit in a single feedforward pass. The examples highlight the model’s ability to handle diverse editing tasks and styles.

This figure shows several examples of how MimicBrush can be used for different image editing tasks. The examples demonstrate the versatility of the model across various applications including product design (e.g., changing the color of shoes, adding patterns to mugs), fashion (e.g., changing clothing styles or accessories), scene editing (e.g., altering backgrounds), and refining the outputs of other image editing models. The key takeaway is that MimicBrush is capable of handling multiple editing regions simultaneously within a single processing step.

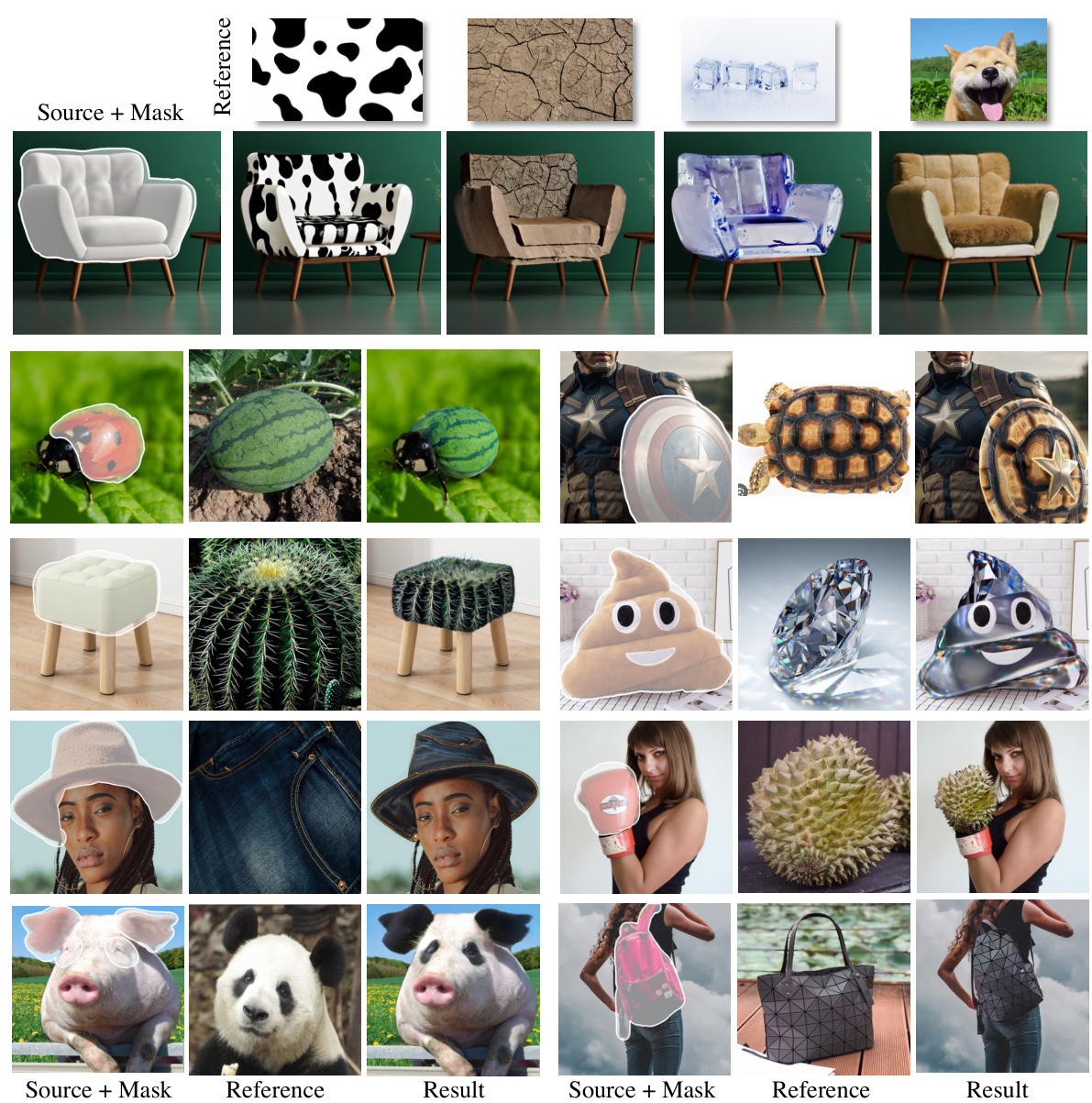

This figure shows several examples of texture transfer using MimicBrush. The method is able to transfer textures from a reference image onto a target image while preserving the original shape of the target object. The examples demonstrate the ability to transfer various types of textures, including patterns (cow print), natural textures (cracked earth, ice), and even textures from images of animals. The depth map is used to maintain the original shape.

More on tables

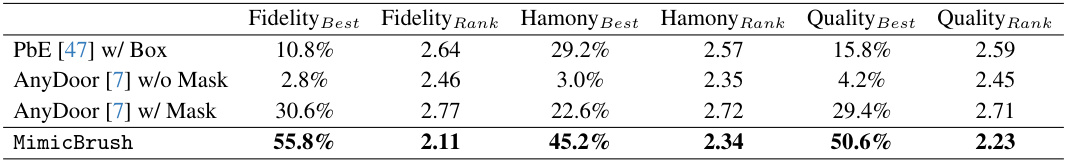

This table presents the results of a user study comparing MimicBrush with other image editing methods. Ten annotators ranked the results of each method based on three criteria: fidelity (how well the edited region matches the reference), harmony (how well the edited region blends with the surrounding image), and quality (the overall visual quality of the edited image). The table shows the percentage of times each method received the highest ranking for each criterion, as well as the average ranking across all annotators. This provides a subjective evaluation of the methods’ performance, complementing the objective metrics presented elsewhere in the paper.

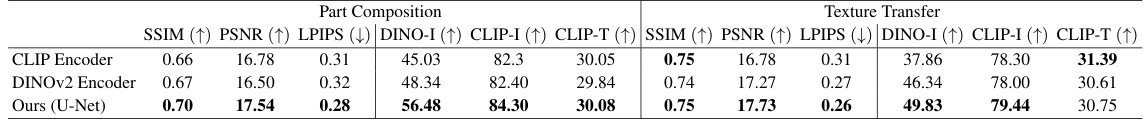

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different methods for extracting features from reference images in the imitative editing task. The study compares using a U-Net, CLIP encoder, and DINOv2 encoder. The performance is evaluated across multiple metrics (SSIM, PSNR, LPIPS, DINO-I, CLIP-I, CLIP-T) and two different tasks (Part Composition and Texture Transfer). The results show that the U-Net consistently outperforms the other methods.

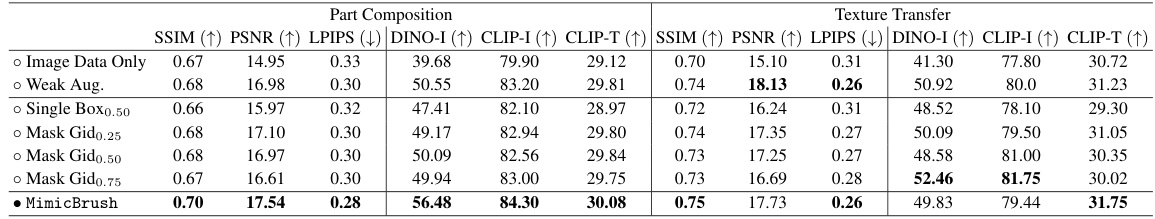

This table presents the results of ablation studies on different training strategies for the proposed image editing method. The first part shows the impact of using only image data versus incorporating video data and augmentations. The second part investigates different masking strategies for the source image, comparing random masking with a method that leverages feature matching to select more informative regions to mask. The bottom row provides the performance of the complete, fully optimized model as a benchmark.

Full paper#