↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many large datasets have an unordered structure (e.g. sets, graphs). Existing compression methods like complete joint shuffle coding are slow or too costly for large unordered data, especially when dealing with a single object. This significantly limits their use in practice, especially for one-shot compression scenarios.

This paper introduces two novel variants of shuffle coding: incomplete and autoregressive coding, aiming to address these limitations. Incomplete shuffle coding speeds up the process by approximating object symmetries, whereas autoregressive shuffle coding improves efficiency in one-shot scenarios by progressively decoding the order. The results show that this novel approach significantly improves speeds compared to existing methods, while maintaining high compression rates and working effectively for extremely large graphs with a billion edges.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly significant for researchers working on data compression and graph algorithms. It presents a novel, high-performance method for lossless compression of unordered data structures, pushing the boundaries of what’s achievable for large-scale datasets like social networks and random graphs with billions of edges. Its practicality and speed improvements open up new avenues of research in big data management and analysis.

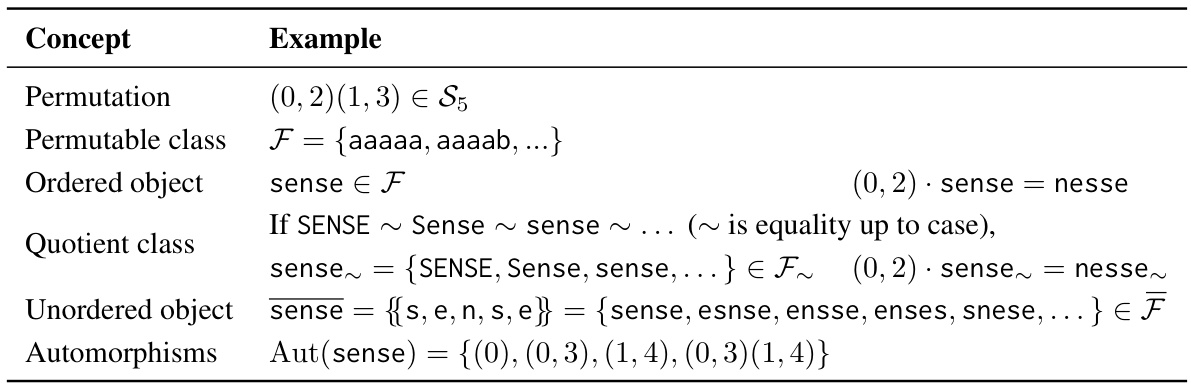

Visual Insights#

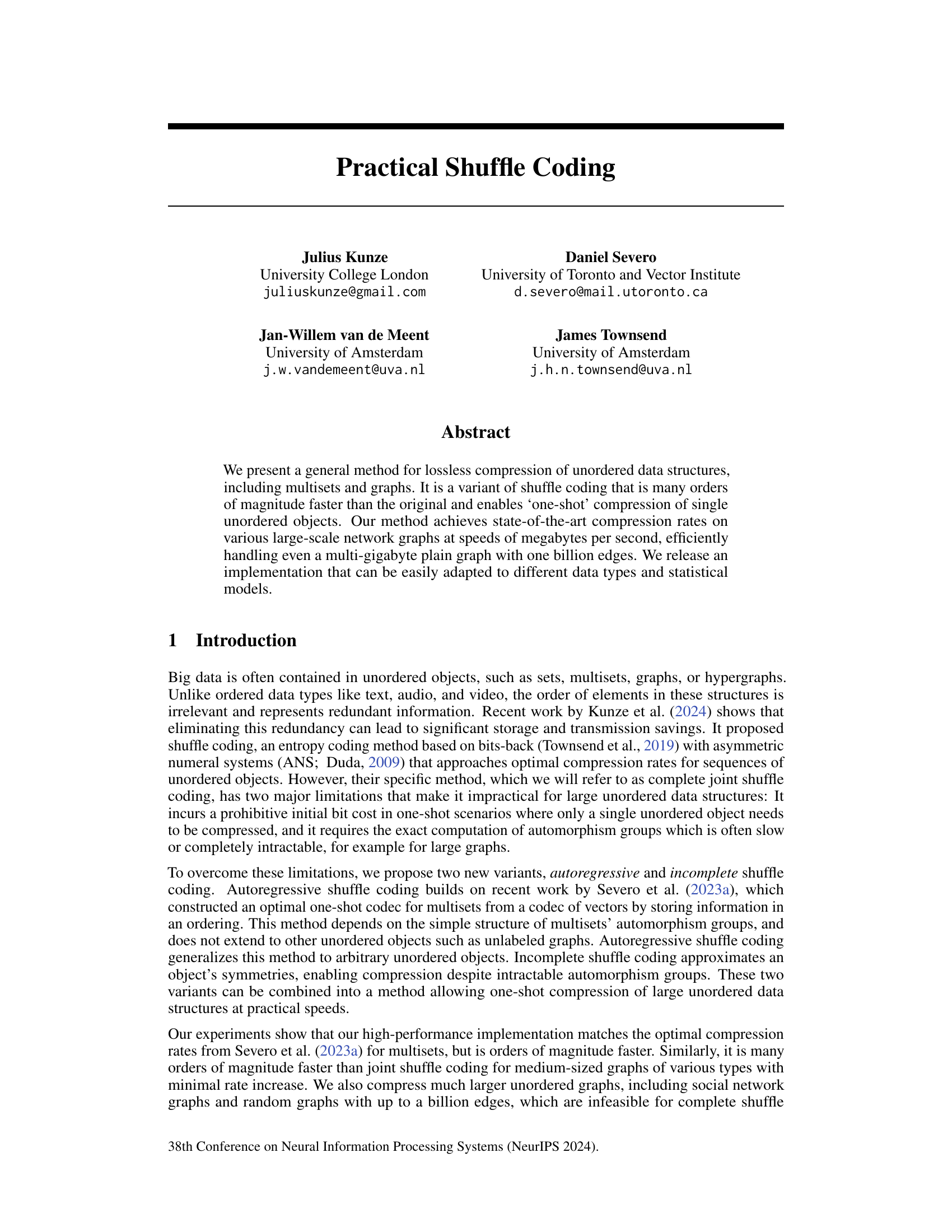

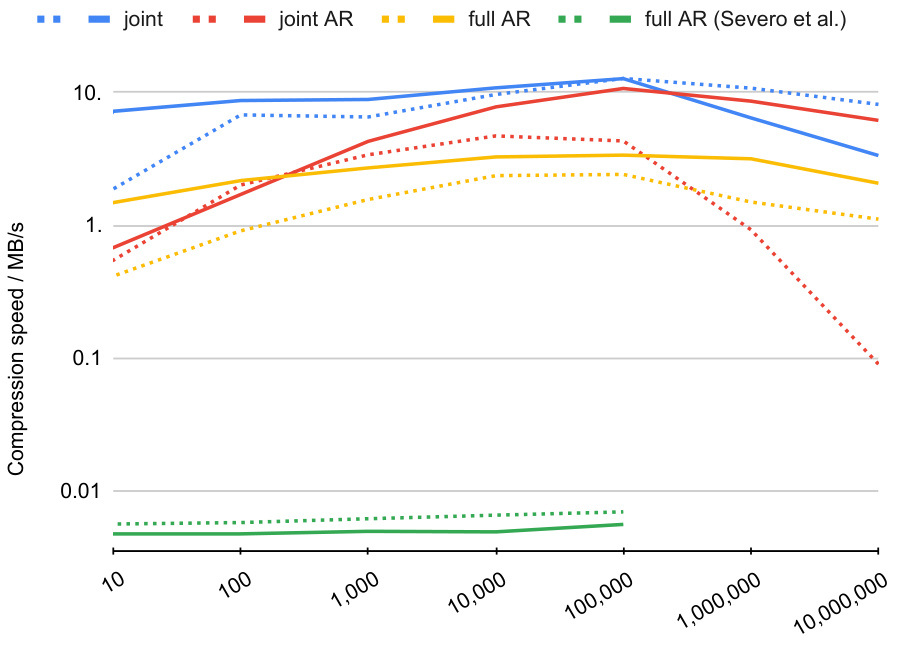

This figure illustrates the autoregressive shuffle coding process for both multisets and graphs. The dotted lines represent the deletion of information as the algorithm proceeds. In both cases, an element is ‘pinned’ (selected) and then ‘popped’ (removed and encoded), iteratively processing the remaining structure until all elements are handled.

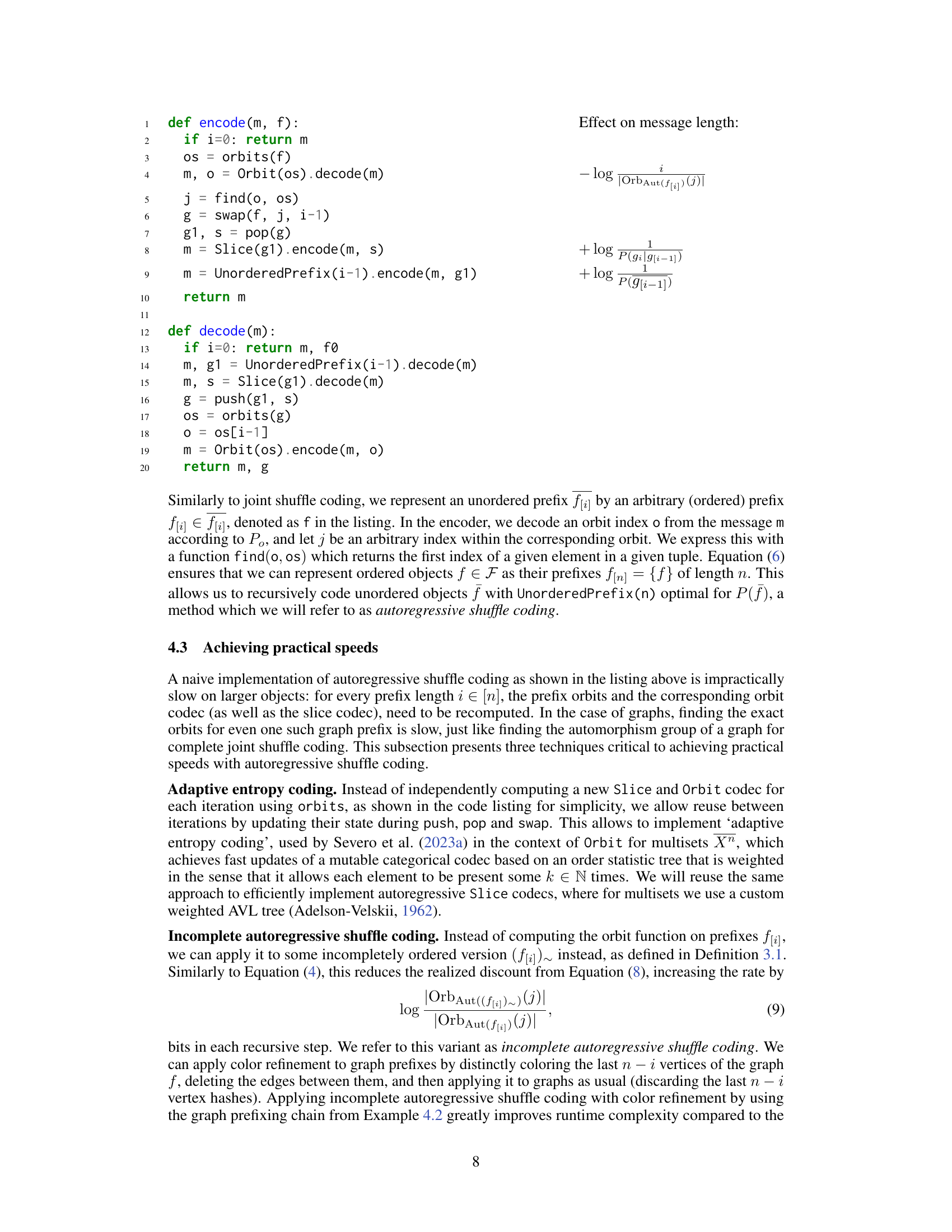

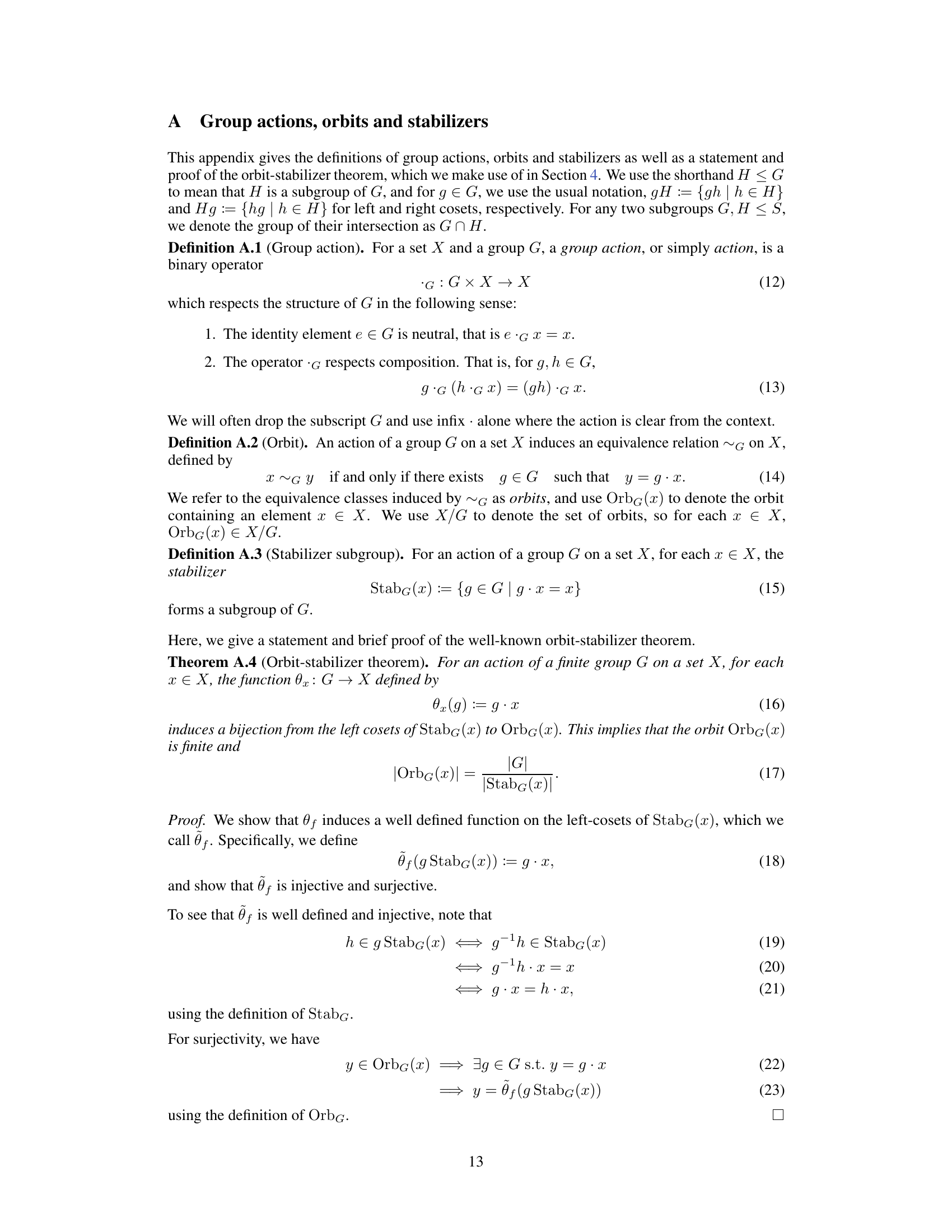

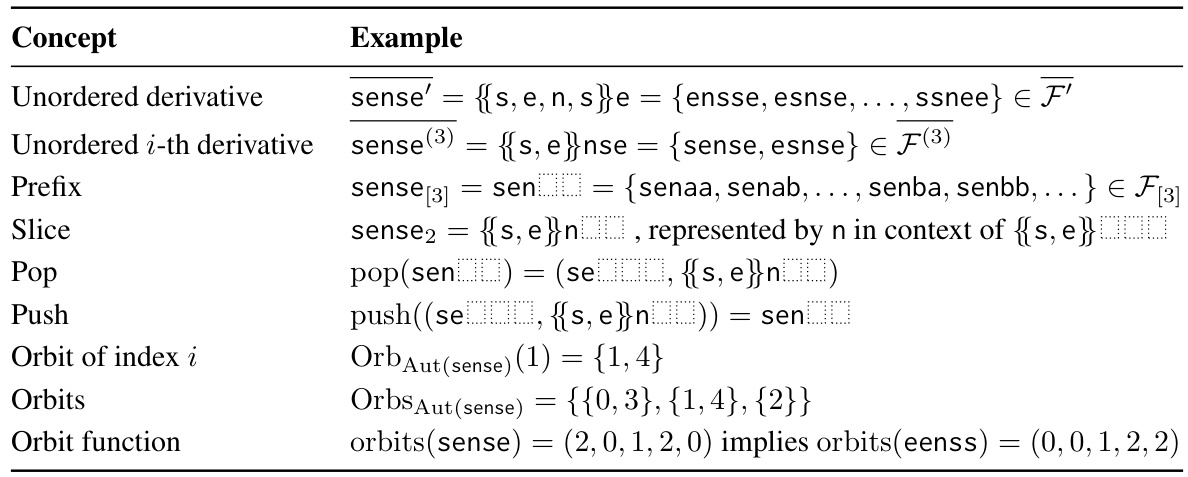

This table provides examples to illustrate key concepts introduced in Section 2 of the paper, specifically focusing on the permutable class F which consists of ASCII strings of length 5. It demonstrates the concepts of permutation, permutable class, ordered object, quotient class, unordered object, and automorphisms using the example string ‘sense’. The use of cycle notation for permutations and the representation of a multiset using curly braces are also shown.

In-depth insights#

Shuffle Code Variants#

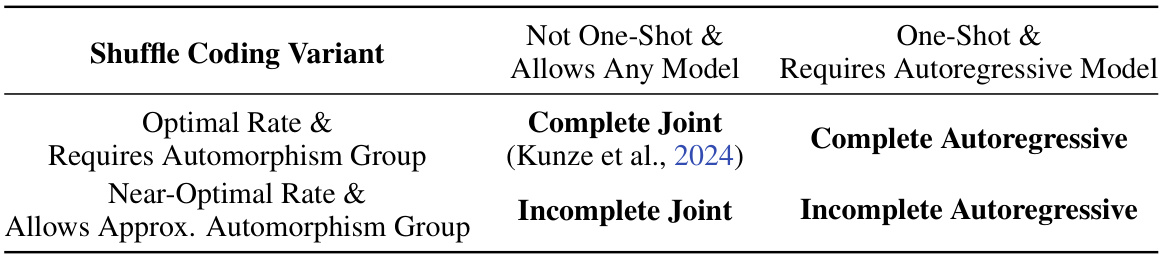

The concept of ‘Shuffle Code Variants’ in lossless data compression is intriguing. It suggests an evolution of the core shuffle coding technique, adapting it to different data structures and computational constraints. Complete joint shuffle coding, while achieving optimal compression, suffers from high computational cost due to automorphism group calculation. Therefore, autoregressive shuffle coding emerges as a more practical alternative, trading off some compression for significantly improved speed by sequentially processing elements. Incomplete shuffle coding represents another approach, sacrificing some compression rate to achieve faster processing by approximating object symmetries. The effectiveness of each variant depends on the specific data type and available resources. The choice between variants involves a trade-off between compression ratio and computational speed, making it crucial to select the appropriate method based on the specific application’s requirements.

Incomplete Shuffle#

The concept of ‘Incomplete Shuffle Coding’ addresses a critical limitation of traditional shuffle coding methods: the computational cost associated with calculating automorphism groups, especially for large graphs. The core idea is to trade-off some compression efficiency for a significant speed gain by approximating an object’s symmetries rather than computing them exactly. This approximation is achieved through techniques like color refinement, which iteratively refines vertex hashes based on local graph structure. By creating a coarser-grained representation of the object’s symmetries, the algorithm dramatically reduces the computational burden, making it feasible to compress even massive graphs at practical speeds. Although not achieving the optimal compression rates of its complete counterpart, incomplete shuffle coding still offers a substantial improvement in rate over existing alternatives, showcasing its practical value. The trade-off between compression rate and speed makes it a highly attractive solution for large-scale data compression tasks where time efficiency is paramount.

Autoregressive Gains#

The concept of “Autoregressive Gains” in the context of data compression, particularly for unordered data structures, suggests that an autoregressive approach can significantly improve compression performance. Autoregressive methods model the probability of the next data element conditional on the preceding elements, thus leveraging the inherent dependencies within the data. This contrasts with traditional approaches that often treat each element independently. In the context of unordered data, this gain is particularly important because it enables the exploitation of sequential dependencies by imposing a sequential structure. By effectively ordering the data, even temporarily, autoregressive methods can capture contextual information that would be lost if the data were treated as a completely unordered set. The gains might be realized through improved compression ratios and/or faster encoding/decoding speeds compared to non-autoregressive counterparts. However, the effectiveness of this approach is also dependent on the choice of autoregressive model and its ability to accurately capture underlying data patterns. The trade-off involves balancing the gains from exploiting sequential information against the overhead of establishing an appropriate sequential structure. This may involve specific ordering strategies or additional computational costs to achieve the best results. Therefore, the practical implications of autoregressive gains heavily rely on careful model selection and parameter tuning, alongside optimization strategies to minimize the potential computational overhead

Practical Speedups#

The concept of “Practical Speedups” in the context of a research paper likely refers to methods implemented to enhance the efficiency and practicality of an algorithm or model. This could involve several key aspects. Optimization techniques: such as algorithm design choices, data structure selections, and parallelization strategies, are crucial for reducing runtime and resource consumption. Approximation strategies: balancing accuracy with speed can be vital, particularly when dealing with large datasets; approximations allow faster processing but might sacrifice some precision. Hardware acceleration: utilizing specialized hardware like GPUs could significantly boost performance but requires careful integration and potentially specific code adaptations. Software engineering: the overall design of the codebase and implementation details significantly impact the execution speed; choices like efficient data representation, modularity, and memory management greatly influence runtime. Scalability: the approach should handle increases in data volume and complexity gracefully, demonstrating its usefulness in real-world scenarios. A thorough analysis of “Practical Speedups” would entail assessing each of these aspects and their contributions toward achieving efficient and usable performance.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of a research paper on shuffle coding would ideally explore several promising avenues. Extending shuffle coding to handle diverse data types beyond graphs and multisets is crucial, encompassing complex structures like hypergraphs and tensors. The current work provides a foundation, but generalizing the algorithms and theoretical analysis to these richer representations would significantly broaden its applicability. Improving the efficiency of the autoregressive approach is another key area. While the authors achieve significant speed gains, further optimizations, particularly in handling large graphs, are still needed. This could involve exploring alternative data structures, leveraging parallelization more effectively, or developing more sophisticated models for approximating automorphism groups. Investigating the interplay between different shuffle coding variants is important. The paper introduces autoregressive and incomplete shuffle coding, and comparing their strengths and weaknesses in various scenarios, including their combination for hybrid approaches, would enhance the understanding of their practical utility. Finally, exploring the theoretical limits of shuffle coding and developing tighter bounds on the achievable compression rates under different assumptions about data distributions would provide a valuable contribution to the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

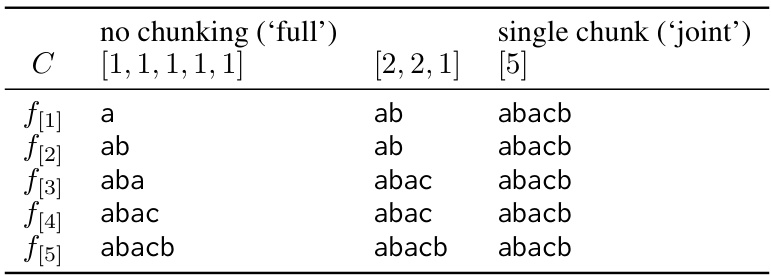

This figure visualizes the expected information content (in bits) of each slice (fi) in a sequence of ordered objects, as a function of the slice index (i). Panel (a) shows the uniform distribution of information content across slices for independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) strings, reflecting the equal probability of each character in the string. Panel (b) illustrates a linearly decreasing information content for slices of simple Erdős-Rényi graphs. This is because the number of edges represented by each slice decreases linearly as the index (i) increases. This difference in information distribution across slices has implications for the efficiency of autoregressive shuffle coding, especially concerning the initial bit cost.

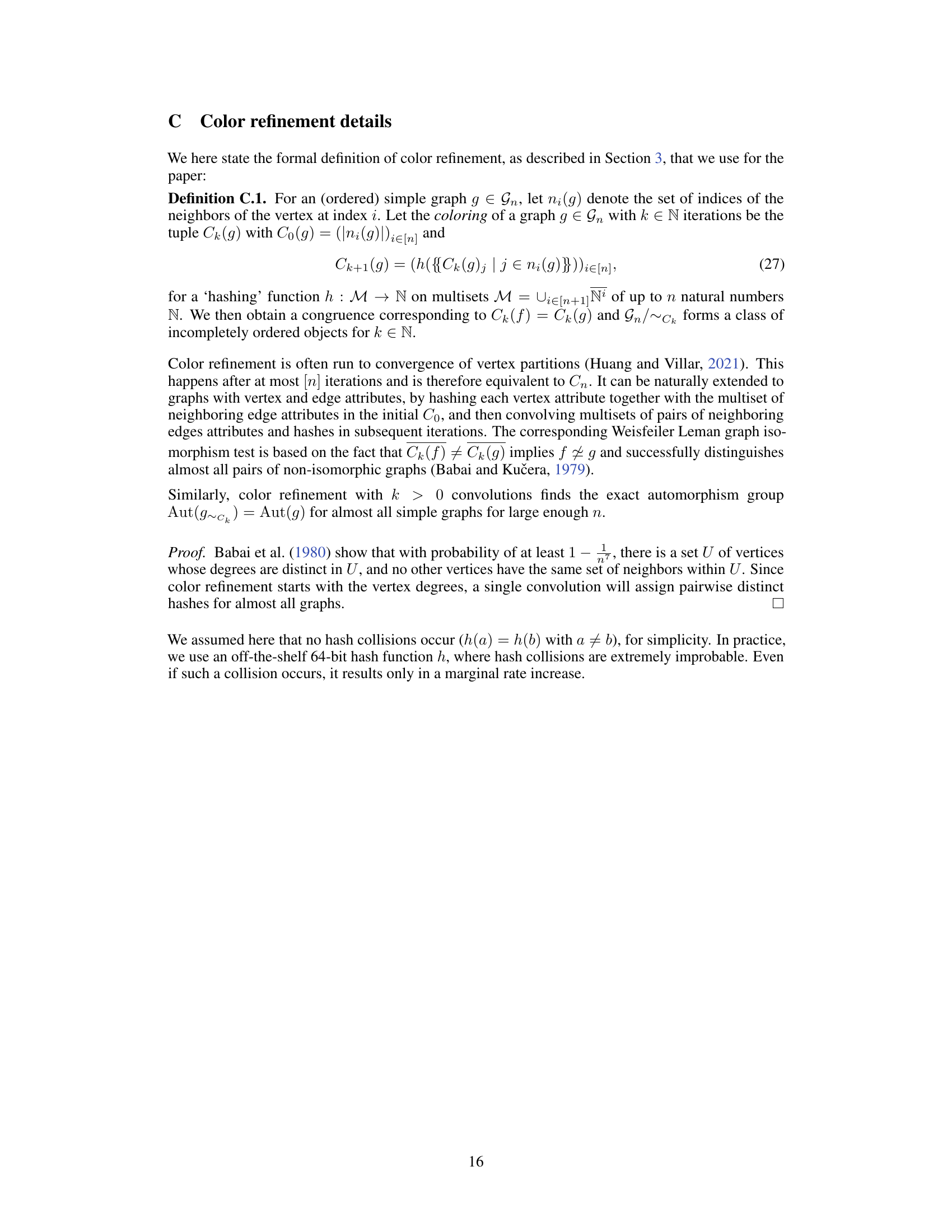

This figure compares the compression and decompression speeds of different shuffle coding methods (joint, joint autoregressive, full autoregressive) on multisets of varying sizes. It demonstrates that the authors’ implementations are significantly faster than a previous state-of-the-art method while achieving comparable compression ratios. The speed improvements are particularly noticeable for larger multisets.

This figure shows how the rate increases as the number of convolutions increases for incomplete shuffle coding. The x-axis represents the number of convolutions used in the color refinement process, and the y-axis shows the relative increase in rate compared to the optimal discount achievable with complete shuffle coding. Each line represents a different graph from the SZIP dataset. The key takeaway is that a small number of convolutions is sufficient to achieve near-optimal compression rates, while significantly improving the runtime compared to the computationally expensive complete method.

This figure displays the results of incomplete autoregressive shuffle coding applied to SZIP graphs. Three plots show the effect of varying the number of chunks used in the algorithm. The top plot shows the relative increase in the net rate (accounting for the initial bits cost) compared to the optimal rate, highlighting how the unrealized discount changes with the number of chunks. The middle plot displays the relative increase in the rate compared to the optimal rate. The bottom plot illustrates the compression and decompression speeds for different chunk sizes. Each line represents a different graph from the dataset.

More on tables

This table exemplifies the color refinement process for plain graphs with 0 and 1 convolutions. It showcases how color refinement, a technique used to approximate a graph’s automorphism group, works in practice. The incompletely ordered graphs resulting from the process are displayed, along with the corresponding vertex hashes. The example highlights the difference between using only degree information (C₀) and including neighbor information (C₁), illustrating how more information leads to a more accurate representation of the graph’s symmetries.

This table provides examples to illustrate core concepts introduced in Section 2 of the paper, specifically focusing on the permutable class F (ASCII strings of length 5). It demonstrates permutations, permutable classes, ordered objects, quotient classes, unordered objects, and automorphisms using the example string ‘sense’. The use of cycle notation for permutations and multiset notation ({{…}}) are also shown.

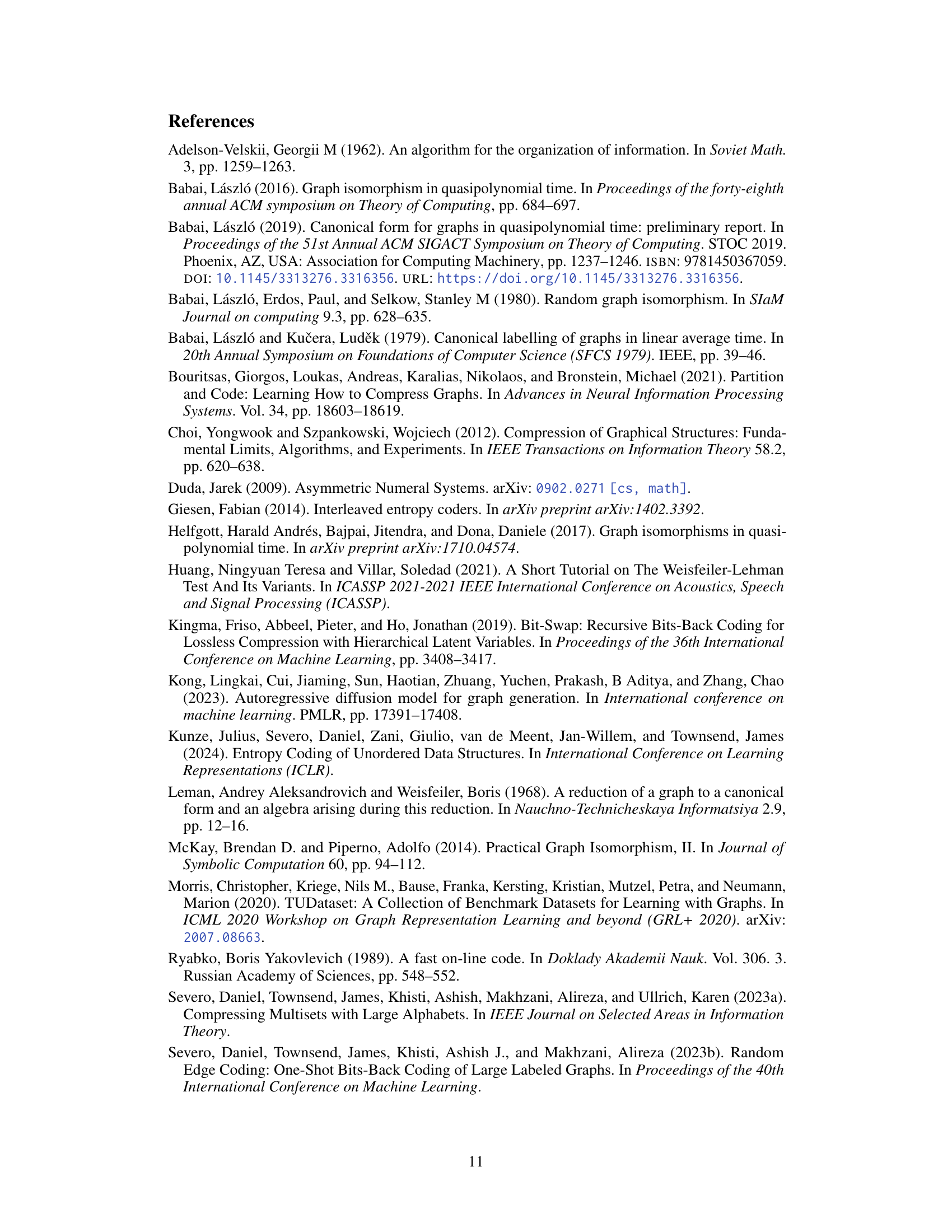

This table summarizes four variants of shuffle coding, categorized by whether they require computation of the automorphism group, whether they allow for one-shot compression of a single unordered object, and whether they utilize an autoregressive model. It shows that complete joint shuffle coding requires the automorphism group and is not one-shot, while complete autoregressive shuffle coding is one-shot and uses an autoregressive model. Similarly, incomplete joint and incomplete autoregressive methods offer near-optimal rates, with the latter employing an autoregressive model and allowing one-shot compression.

This table demonstrates how prefixes of a string are formed using different chunking strategies in autoregressive shuffle coding. It shows how the prefixes change based on different chunk sizes, illustrating the impact of chunking on the information decoded at each step. The ‘full’ approach represents decoding one character at a time, while the ‘joint’ approach decodes larger chunks of characters.

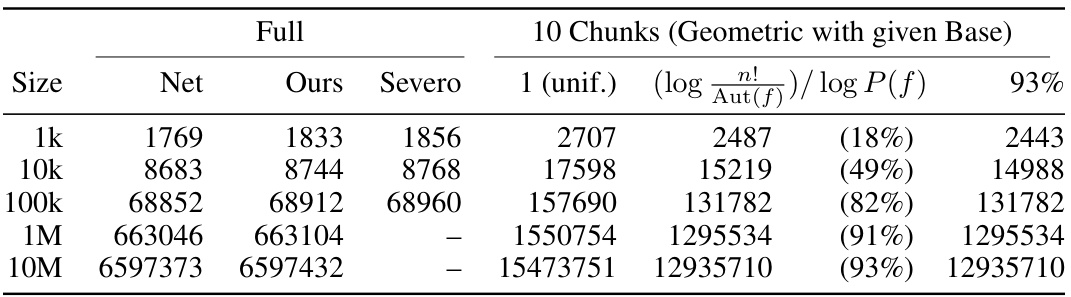

This table compares the compression rates achieved by the authors’ full autoregressive shuffle coding method with those reported by Severo et al. (2023a) for multisets of varying sizes. It also shows the optimal compression rates (net rates) and the rates obtained when using 10 chunks with geometrically increasing sizes. The last column shows the relative discount from Equation (28) for each graph size used as a base for the geometric series.

This table compares the performance of incomplete and complete joint shuffle coding methods on various graph datasets from the TUDatasets collection. The incomplete method, which uses color refinement, is significantly faster than the complete method, with only a small increase in compression rate. The table highlights the speed improvements achieved by the incomplete method, particularly for larger datasets where the complete method was too slow to complete.

This table compares the performance of incomplete and complete joint shuffle coding methods on the SZIP graph dataset. It shows the net compression rate (additional cost given existing compressed data), and compression/decompression speeds using 8 threads. The autoregressive Pólya urn model is used for both methods. Note that incomplete coding is significantly faster.

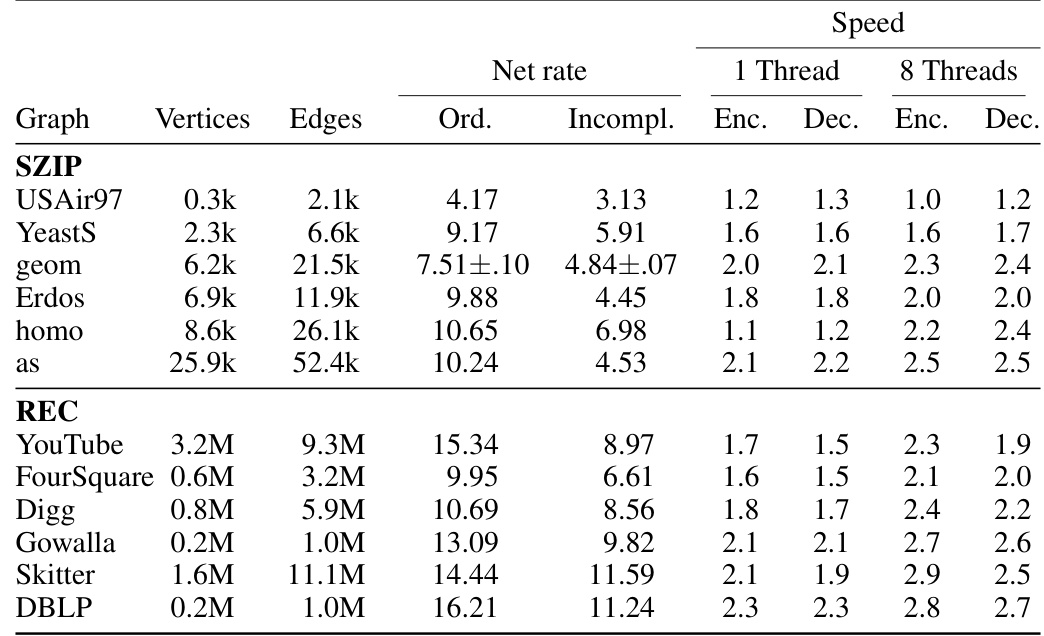

This table compares the performance of incomplete joint shuffle coding using the autoregressive Pólya urn model against the performance of just using the ordered Pólya urn model. It presents net rates (bits per edge), and compression/decompression speeds (MB/s) for both single-threaded and multi-threaded executions on two different graph datasets: SZIP and REC. The table also highlights the mean net rates with standard deviations.

This table compares the performance of incomplete autoregressive shuffle coding with different chunk sizes (16 and 200) against the SZIP algorithm. It shows compression rates (bits per edge) and speeds (kB/s) for various graphs, using both Erdős-Rényi (ER) and autoregressive Pólya urn (AP) models. The results highlight the trade-off between compression rate and speed, and the effect of model choice. The standard deviations are also provided indicating the stability of the results. The data was compressed using 8 threads.

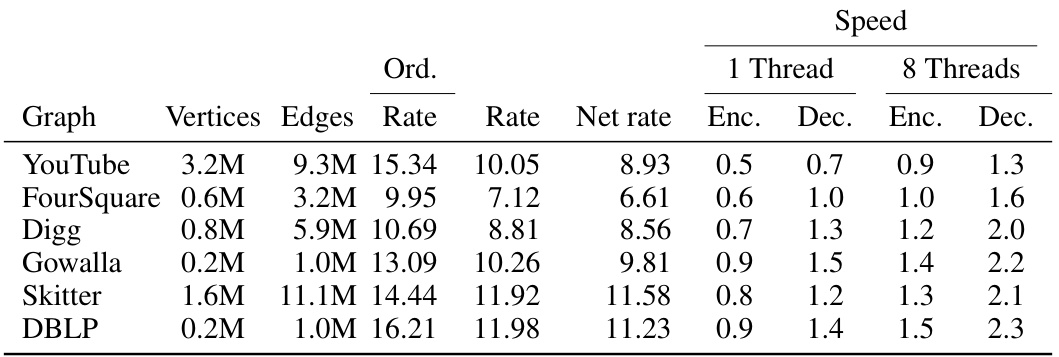

This table compares the performance of incomplete joint shuffle coding using the autoregressive Pólya urn model (AP) against a baseline of just using the ordered AP model. The data used are SZIP and REC graphs. The table presents mean net rates (bits per edge) and compression speeds (MB/s) for both single and multi-threaded processing. Standard deviations are included, showing low variability in the results.

This table presents the results of applying incomplete autoregressive shuffle coding to large Erdős-Rényi random graphs with up to one billion edges. It compares the compression rates (bits per edge) and speeds (MB/s) achieved with this method to the uncompressed size of the graphs. The results showcase the effectiveness of the method on massive graph datasets.

Full paper#