↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Adapting robots to new tasks and bodies is a major hurdle. Current methods either excel at specific tasks or single bodies but not both. This limits their use in dynamic, real-world settings. The paper tackles this challenge by developing a generalizable approach.

The proposed solution uses a novel architecture; a joint-level input/output representation unifying state and action spaces across various robots, and a structure-motion state encoder to handle embodiment-specific and shared knowledge. A matching-based network then generates an adaptive policy using only a few demonstrations, proving to be robust and superior to current techniques on a range of continuous control tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel framework for few-shot imitation learning that addresses the challenge of generalizing to unseen robot embodiments and tasks. This is a significant advancement in robotics research and will help to improve the versatility and adaptability of robots in real-world applications. It also opens up new avenues for further research, such as developing more efficient and robust policy adaptation mechanisms and investigating the application of this method in more diverse domains.

Visual Insights#

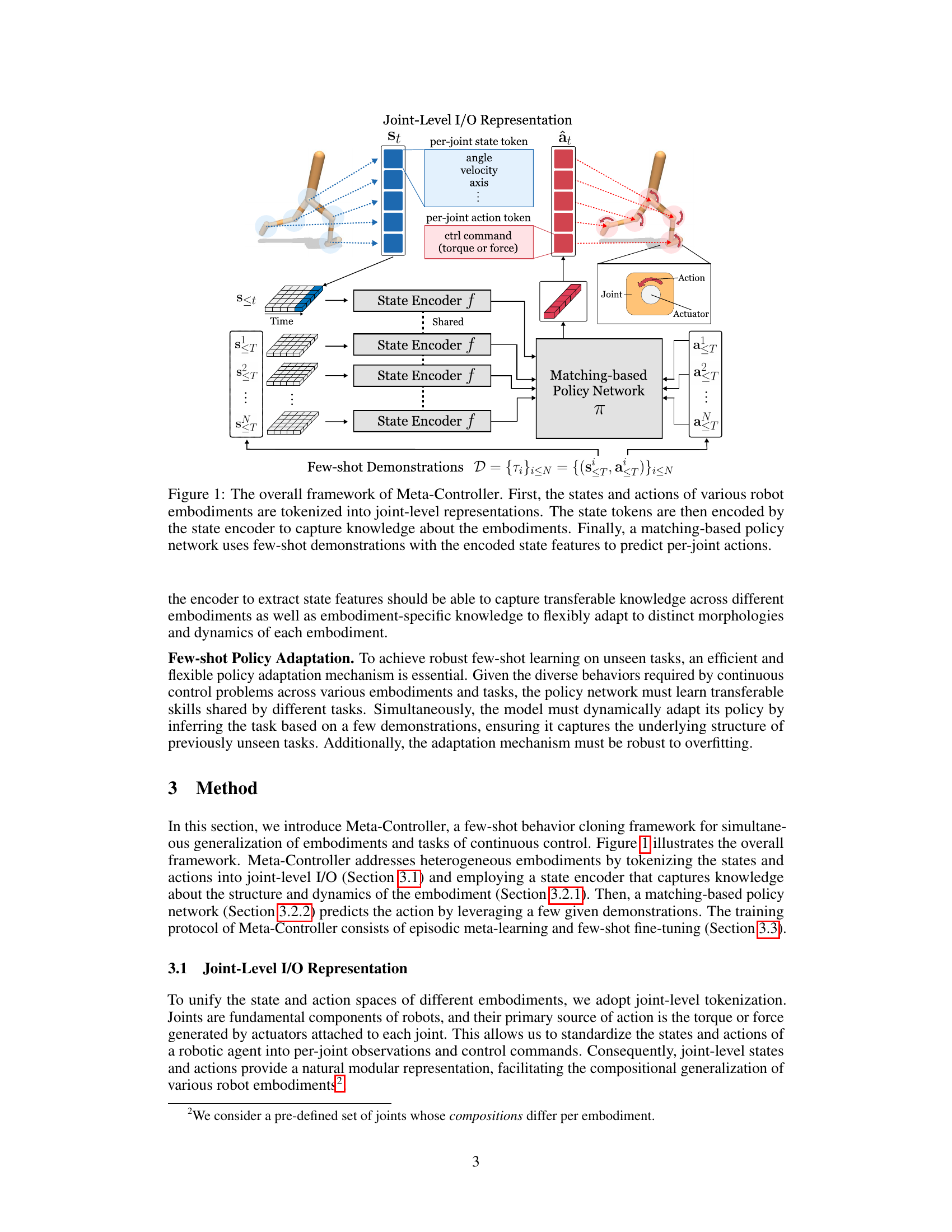

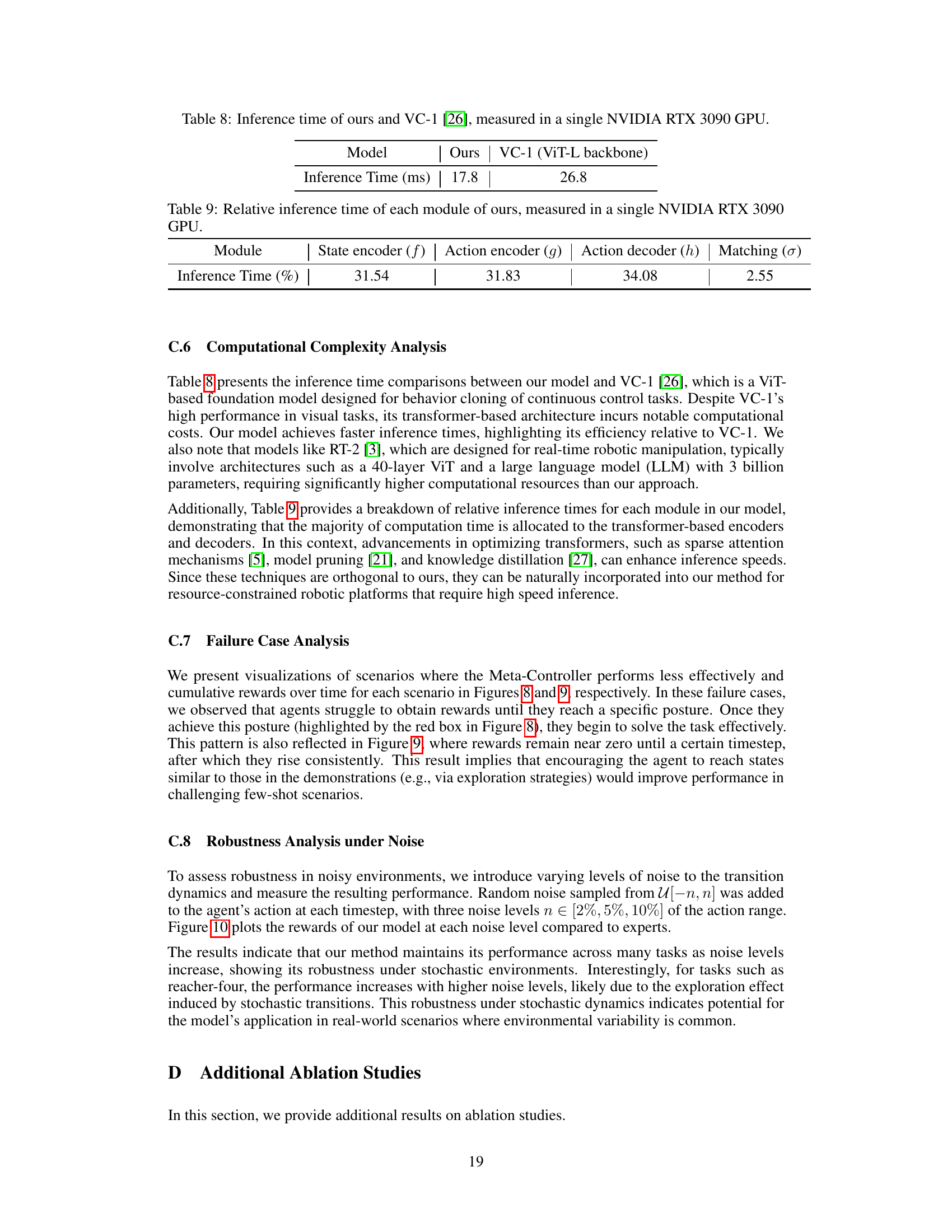

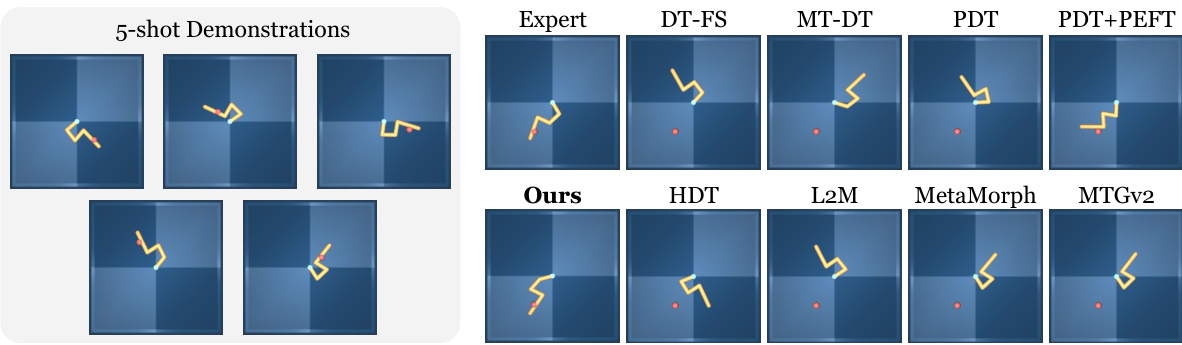

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller framework. The process begins with the robot’s states and actions, which are converted into joint-level representations. These are then fed into a state encoder, which extracts features that capture both shared and embodiment-specific knowledge. This information is used by a matching-based policy network, which learns to predict the robot’s actions using a small number of demonstrations. The output of the network are actions for each joint.

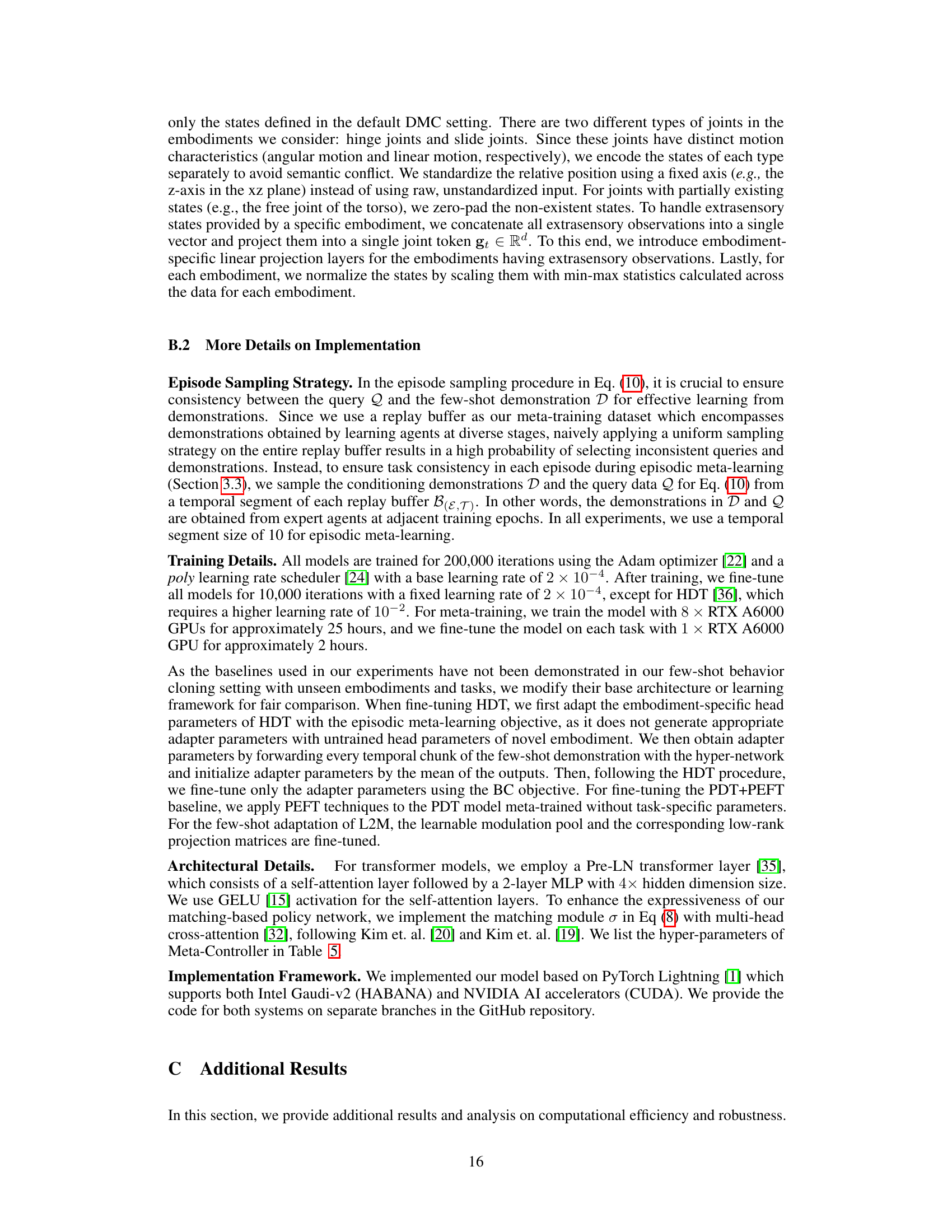

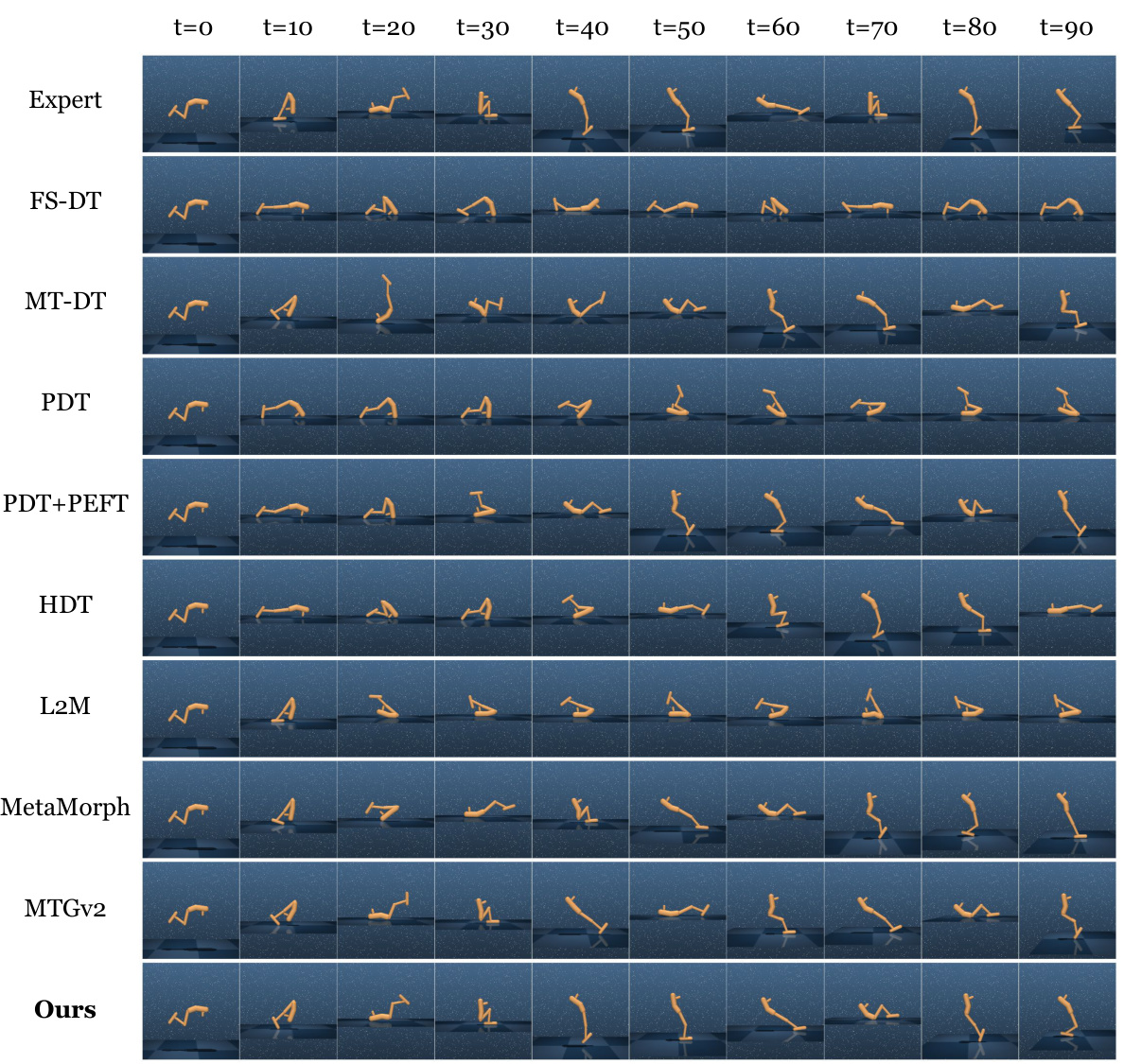

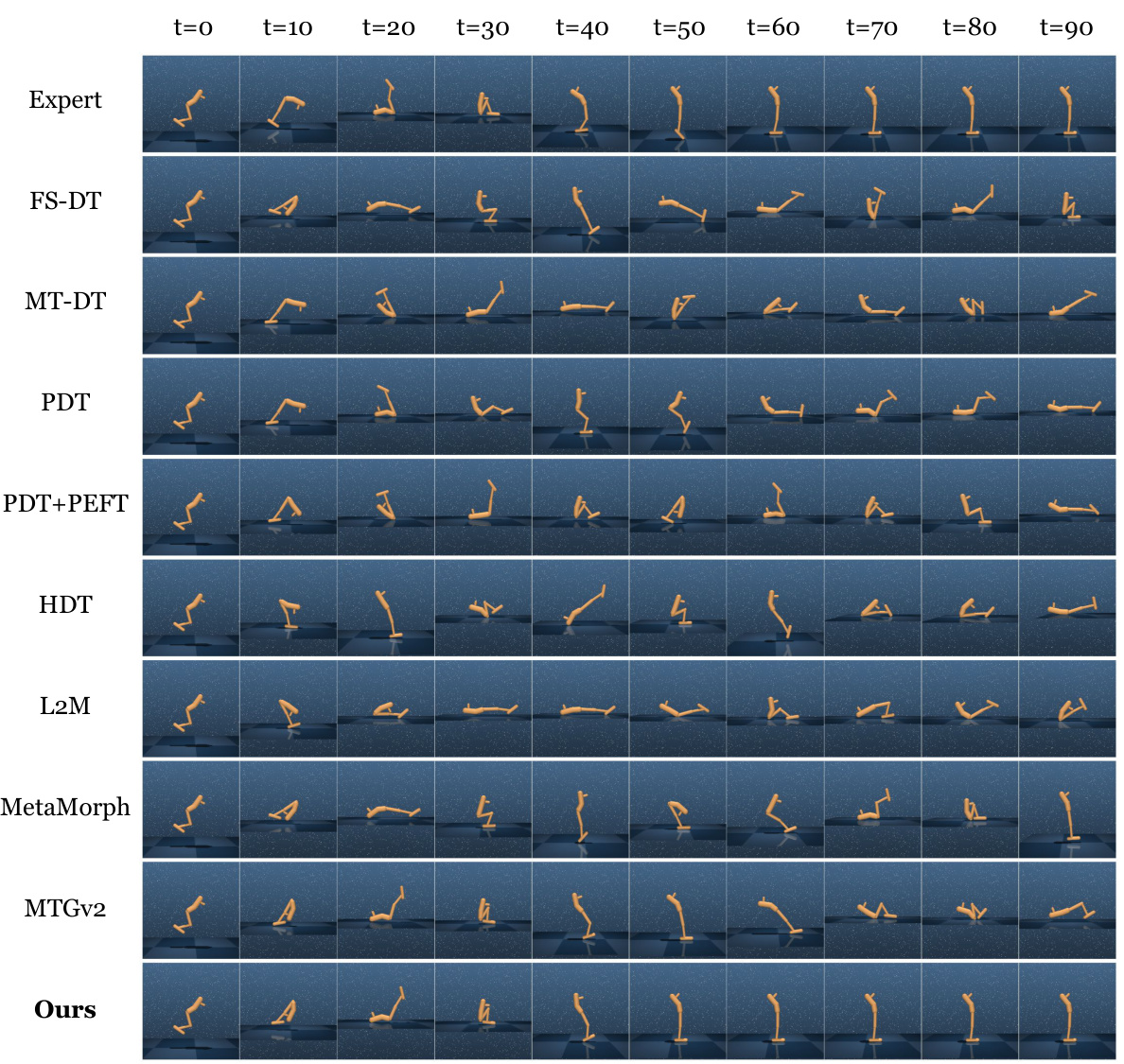

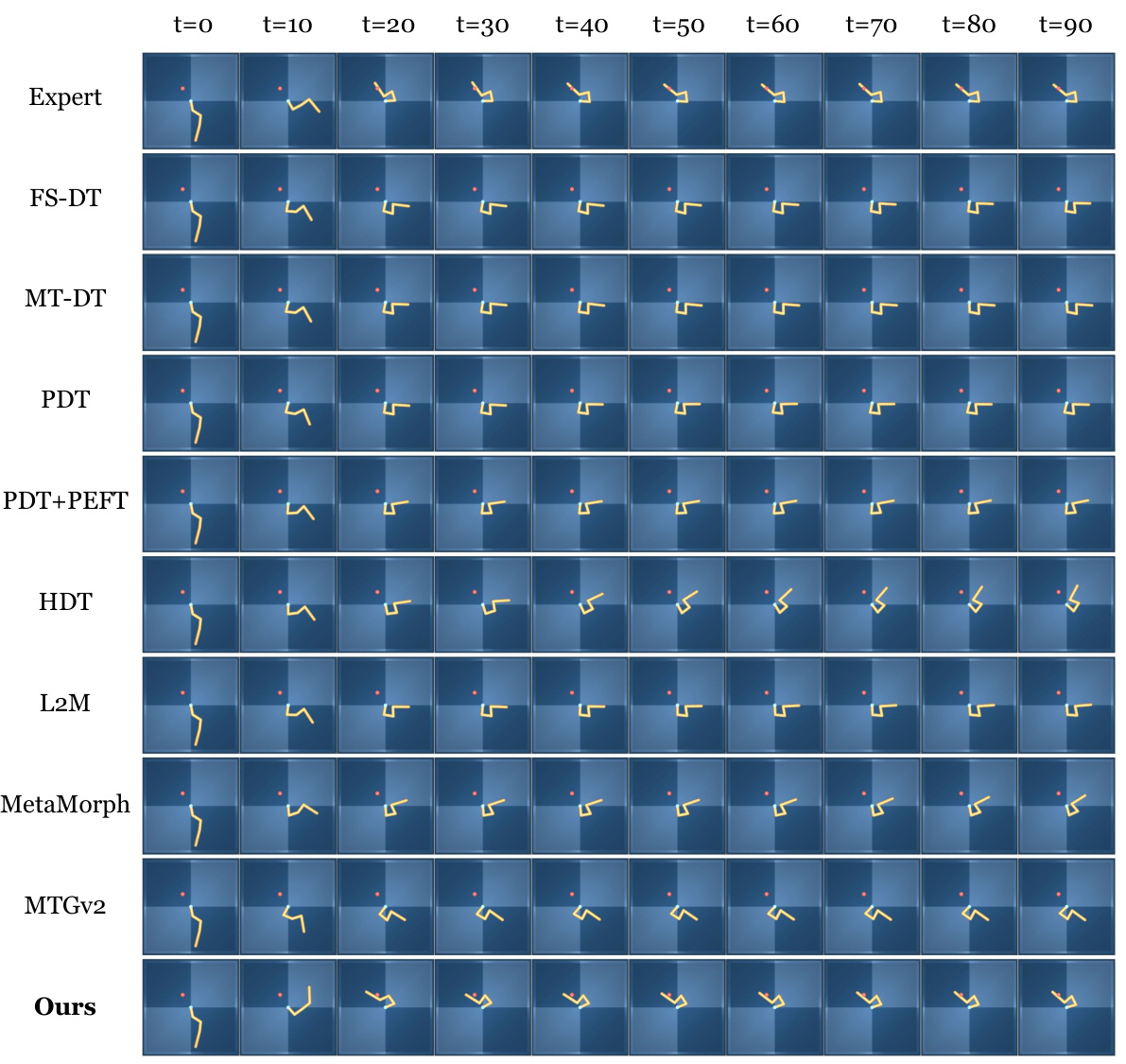

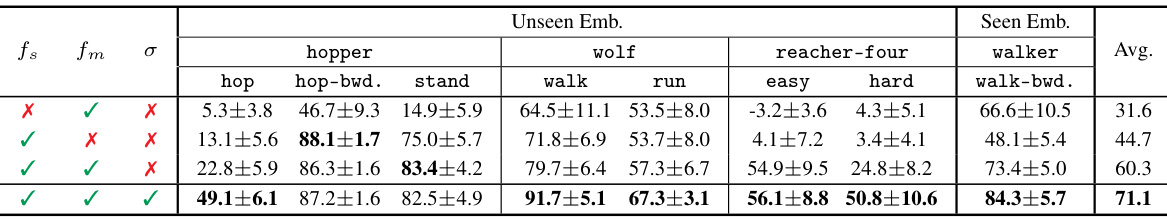

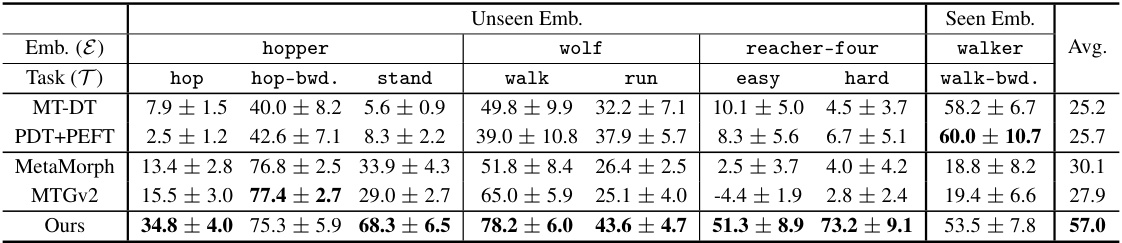

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller method against several baseline methods (FS-DT, MT-DT, PDT, PDT+PEFT, HDT, L2M, MetaMorph, MTGv2) across various tasks and unseen robot embodiments. The results are reported as the normalized average score (mean ± standard error) over 20 different initial states for each task and embodiment. The table highlights the superior performance of Meta-Controller in few-shot generalization across both unseen embodiments and tasks.

In-depth insights#

Few-Shot Adaptation#

Few-shot adaptation in machine learning focuses on training models that can rapidly learn new tasks or adapt to new environments using only a small number of examples. This is particularly crucial in robotics, where training a robot for every task from scratch is inefficient and impractical. The core challenge lies in finding efficient mechanisms to transfer knowledge from limited demonstrations to novel situations. This involves carefully designing network architectures, such as using modular components, which allow for generalization across various tasks and embodiments, and incorporating effective learning strategies. Key considerations often include handling heterogeneous embodiments with diverse morphologies and dynamics and ensuring robustness to overfitting with limited data, often using techniques like meta-learning or regularization methods. Ultimately, successful few-shot adaptation hinges on achieving a balance between the ability to learn task-specific details and leverage generalizable knowledge from previous experiences.

Joint-Level Tokens#

The concept of “Joint-Level Tokens” presents a powerful approach to handling the heterogeneity of robot embodiments in a unified manner. By representing robot states and actions at the level of individual joints, this method elegantly sidesteps the challenges posed by differing morphologies and degrees of freedom across various robots. This approach promotes compositionality, enabling generalization across different robot designs because the fundamental building blocks (joints) remain consistent. The use of tokens allows for a consistent input/output representation, regardless of the specific number of joints or the dimensionality of the state and action spaces associated with each embodiment. This abstraction facilitates efficient learning and generalization, allowing a single model to learn control policies applicable to a diverse range of robots with minimal retraining. Furthermore, it enables modular policy learning, which offers advantages in terms of both efficiency and transferability. However, the success of this method relies heavily on the quality of the joint-level representation and the ability of the subsequent models to leverage the tokenized information effectively. Challenges include defining appropriate joint-level features that capture both embodiment-specific and task-relevant information and designing models capable of handling variable-length token sequences effectively. Despite these challenges, the Joint-Level Tokens approach offers a significant advance in tackling the problem of robot embodiment generalization in robotic control.

Meta-Controller#

The concept of a ‘Meta-Controller’ in a robotics research paper suggests a system capable of controlling diverse robot embodiments and tasks with minimal training data. This implies a high degree of adaptability and generalizability, a crucial step towards creating truly versatile robots. The core innovation likely lies in the architecture of the Meta-Controller, possibly involving modular designs, advanced state representation methods, and efficient transfer learning techniques. This architecture would allow the controller to learn common control principles applicable across different morphologies and subsequently adapt to new tasks rapidly through few-shot learning. Key challenges addressed would involve handling the heterogeneous nature of robot states and actions, possibly through joint-level tokenization and encoding that abstracts away embodiment-specific details, and designing a policy network that facilitates effective generalization and rapid task adaptation. The success of such a system would be demonstrated through experiments showcasing impressive performance on unseen robots and tasks using limited demonstrations, potentially comparing favorably against traditional reinforcement learning and imitation learning approaches. The research emphasizes the use of reward-free demonstrations and potentially relies on techniques like meta-learning to enable efficient learning and transfer across multiple embodiments and tasks. The framework presented would likely include evaluations comparing the Meta-Controller’s performance to existing state-of-the-art methods. The overall aim is to advance the field towards more robust, adaptable, and data-efficient robot control systems.

Embodiment Generalization#

Embodiment generalization, in the context of robotics, focuses on creating control policies that transfer effectively across diverse robot morphologies. This is a significant challenge because robots can vary widely in their physical characteristics (number of joints, shapes, sizes, etc.) and dynamic properties (motor gear ratios, inertia, friction, etc.). A successful embodiment generalization approach must abstract away from these specific details, learning transferable skills and representations that generalize to unseen robots. This often involves using modular architectures, which decompose the control policy into reusable components, or joint-level representations, which focus on the individual joints and their interactions. Another critical aspect is data efficiency, which means generalizing effectively from a small number of demonstrations, ideally across a wide range of tasks. The efficacy of these methods is often evaluated in simulation environments offering diverse robot models and task scenarios. Successful methods usually incorporate some form of meta-learning or transfer learning to acquire the ability to quickly adapt to new robots, effectively leveraging shared knowledge across multiple embodiments.

Future Directions#

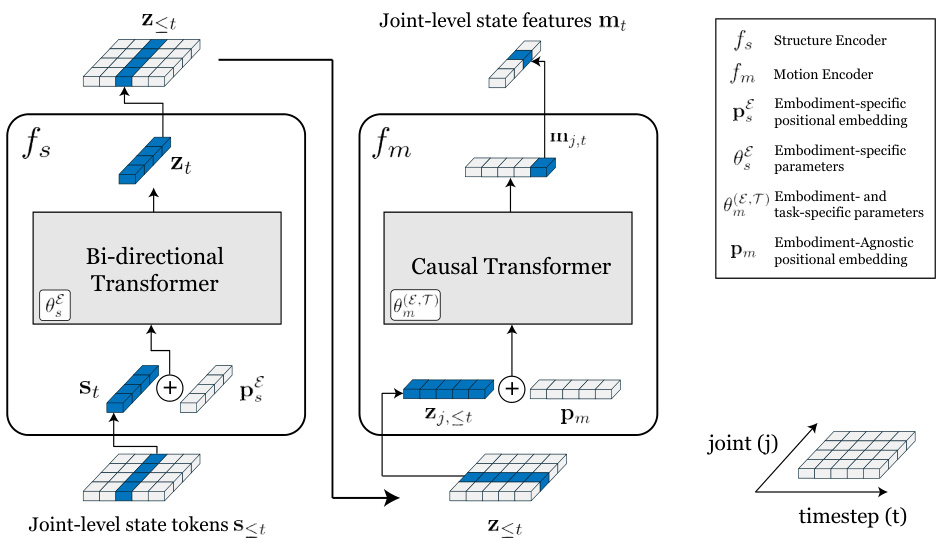

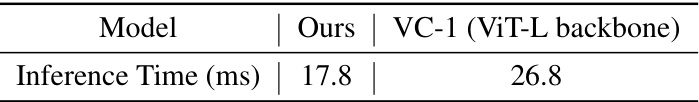

Future research could explore more complex and realistic environments beyond the DeepMind Control Suite, bridging the gap between simulation and real-world robotics. Investigating different reward functions beyond reward-free demonstrations could lead to more efficient and robust learning. Furthermore, exploring alternative architectures and modularity strategies beyond joint-level tokenization would enhance generalizability to diverse robotic morphologies. Finally, addressing the computational limitations of transformers to facilitate real-time applications in resource-constrained settings is crucial. A deeper analysis of the interaction between embodiment-specific and task-specific knowledge within the proposed framework could lead to improved adaptation strategies. Incorporating uncertainty into the learning process would enable robots to operate safely in uncertain environments. Developing a better understanding of the relationship between task complexity and the number of demonstrations required for successful few-shot imitation learning is an important goal. Integrating advanced sensor modalities beyond proprioception could allow for handling more complex perception challenges. The ethical implications of highly adaptable robots necessitate further exploration and careful consideration.

More visual insights#

More on figures

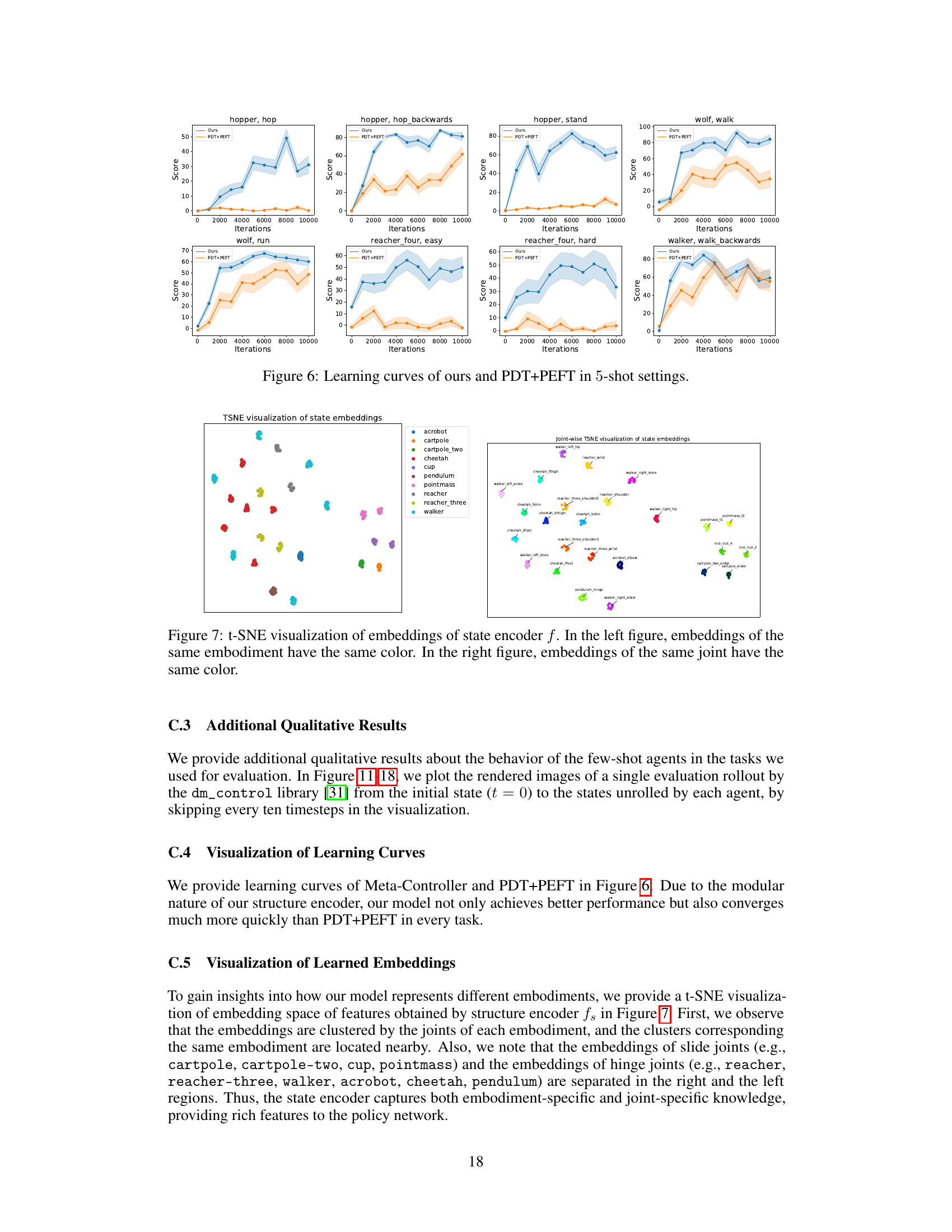

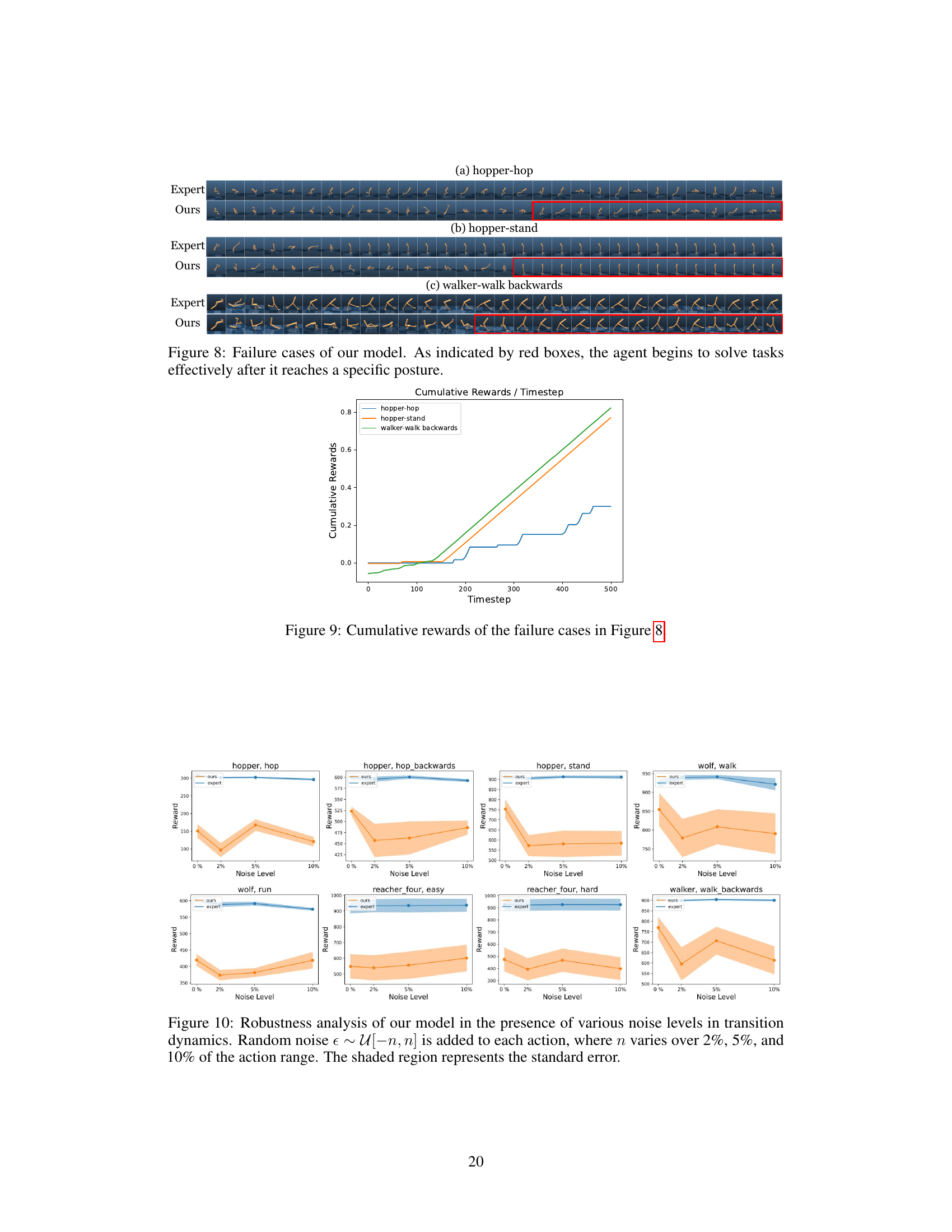

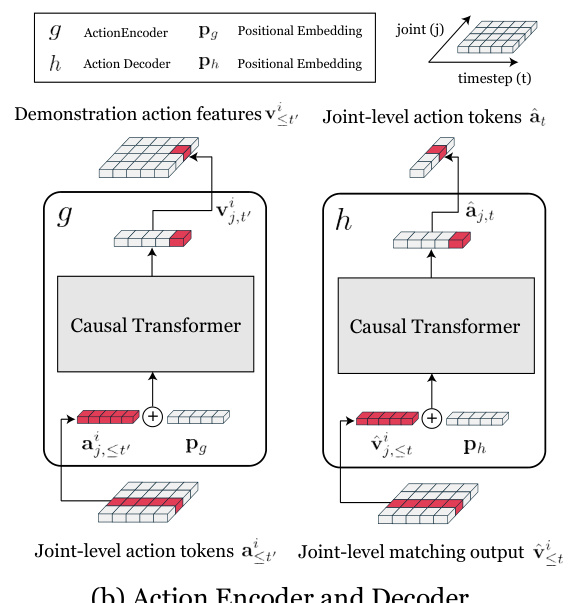

This figure shows the architecture of the state encoder, a crucial component of the Meta-Controller framework. The state encoder takes joint-level state tokens as input and processes them through two transformer networks: a structure encoder (fs) and a motion encoder (fm). The structure encoder captures the relationships between joints within an embodiment, adapting to specific morphologies via positional embeddings and embodiment-specific parameters. The output of the structure encoder is then fed into the motion encoder, which considers the temporal dynamics of joint movements. The motion encoder utilizes causal self-attention to process the sequential data and includes parameters specific to both the embodiment and task, further enhancing adaptability. The final output (mt) represents the encoded state features, incorporating both structural and dynamic information.

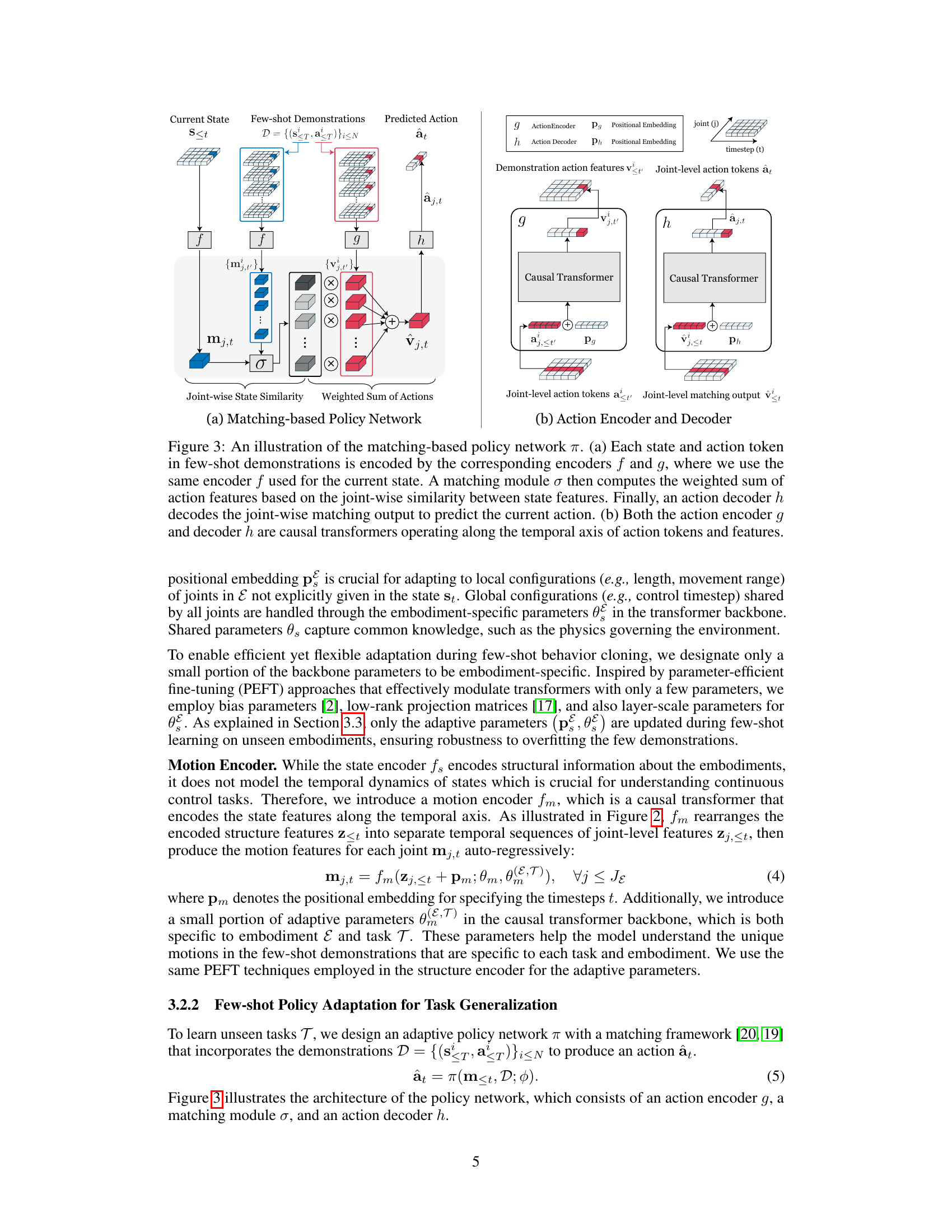

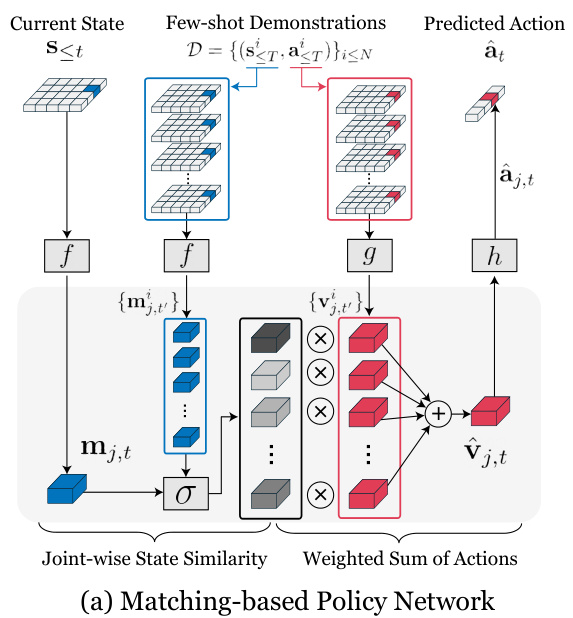

This figure illustrates the Meta-Controller’s matching-based policy network. It shows how the network uses joint-level representations of states and actions from few-shot demonstrations to predict actions for a new, unseen task. The process involves encoding states and actions using encoders (f and g), calculating joint-wise similarity between the current state and demonstrations, weighting demonstration actions based on this similarity, and finally decoding the weighted sum to produce the predicted action.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the matching-based policy network (π) used in the Meta-Controller framework. It shows how the network takes joint-level state and action tokens (from both the current state and demonstrations) as input, processes them through encoders and decoders (f, g, h), and employs a matching module (σ) to combine information for action prediction. The encoders and decoders are causal transformers operating on temporal sequences.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller framework. It begins by tokenizing the states and actions of different robots into a joint-level representation. These tokens are then input to a state encoder which extracts features to represent the robot’s embodiment. Finally, a matching-based policy network uses this information, along with a small number of demonstrations, to predict the actions at the joint level. This allows for generalization to unseen embodiments and tasks.

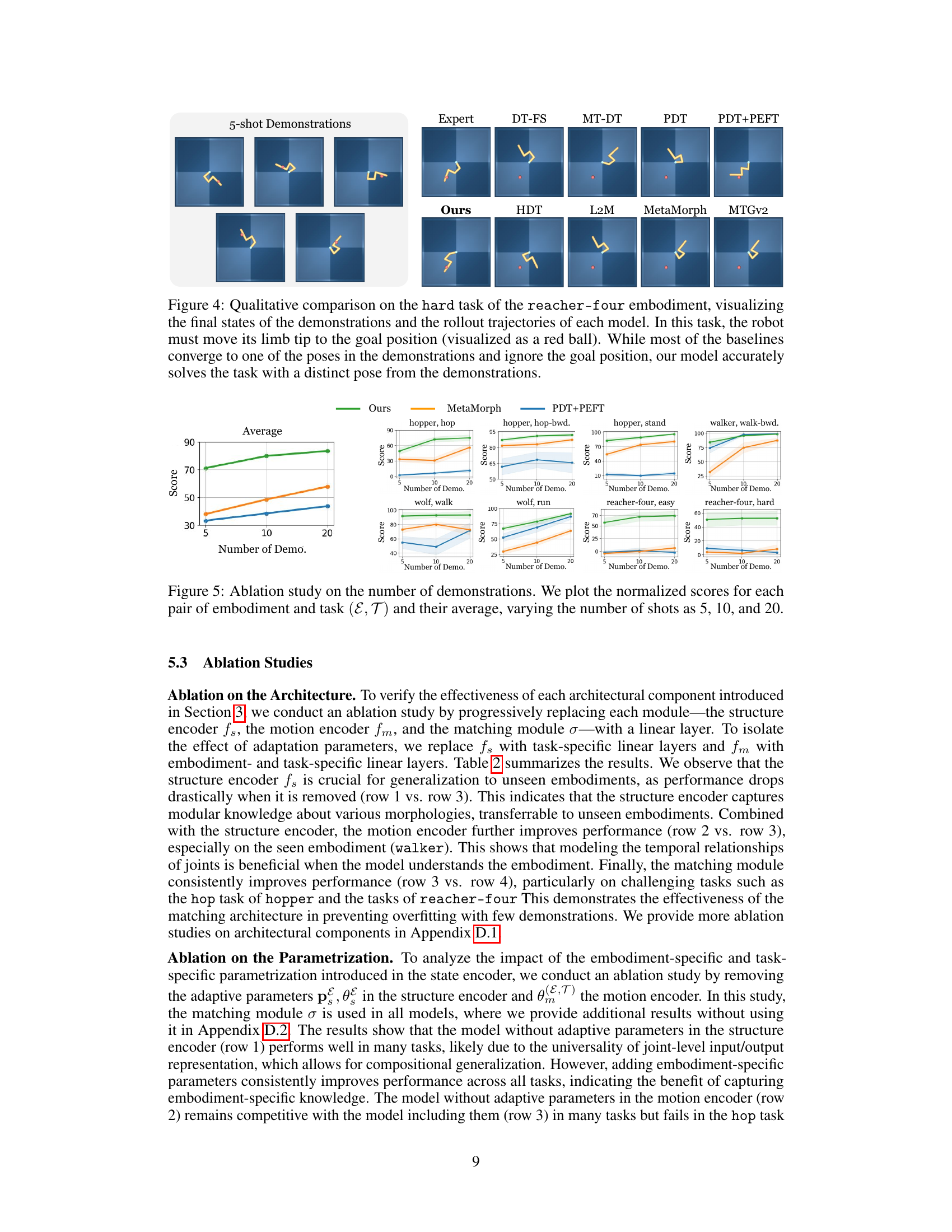

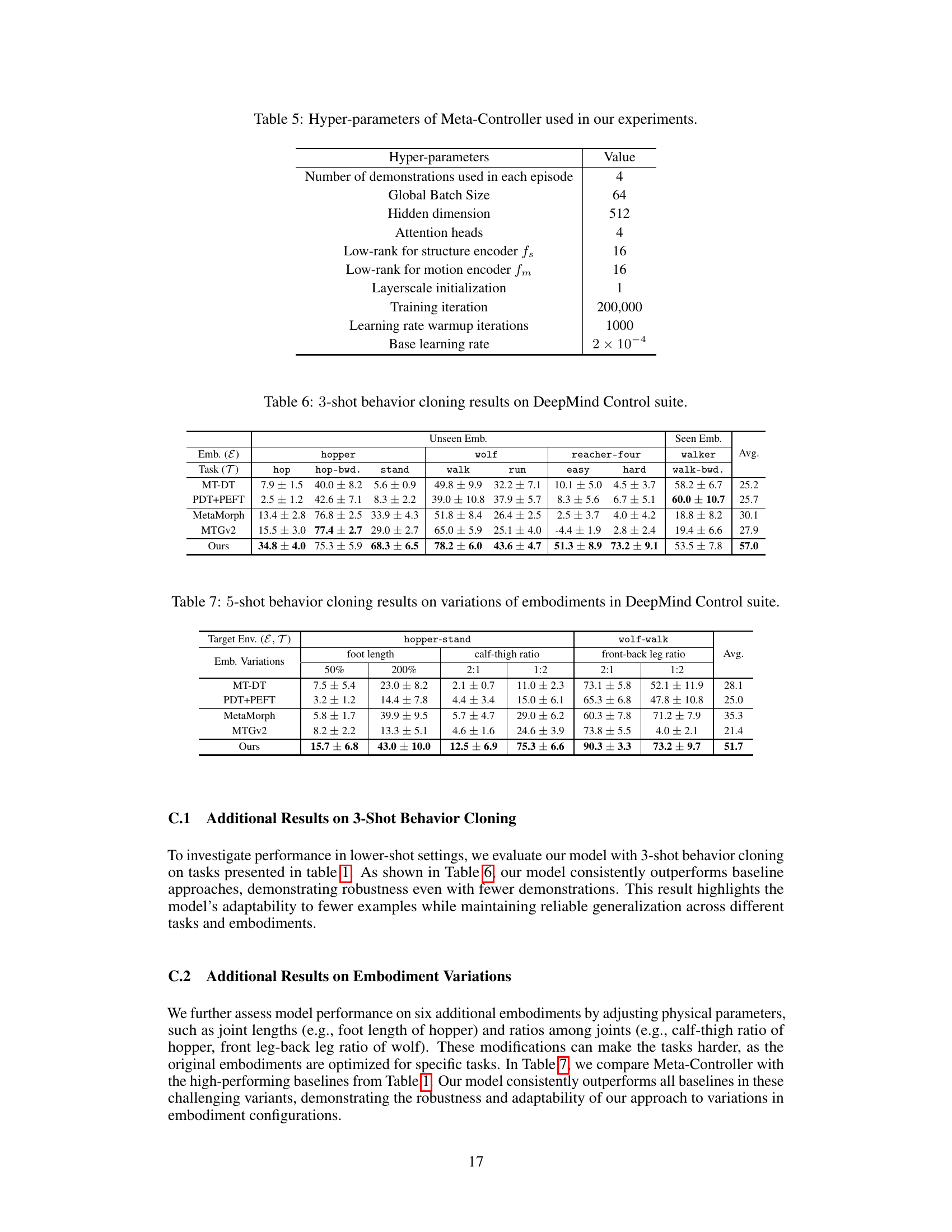

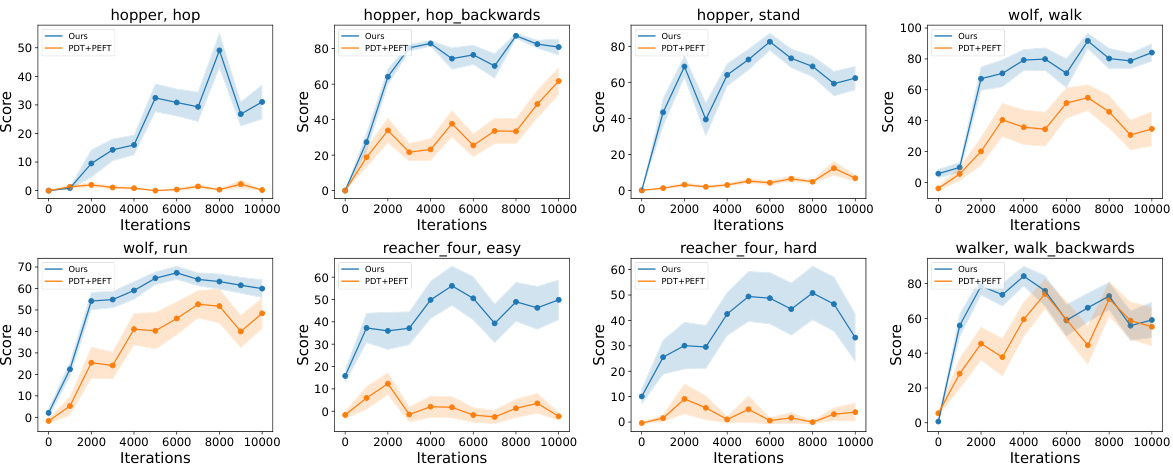

This ablation study evaluates the impact of the number of demonstrations on the model’s performance. The figure displays normalized scores for various continuous control tasks across different robot embodiments. The number of demonstrations used (5, 10, and 20) is varied to show how performance improves with more data. The average performance across all tasks and embodiments is also shown.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller model. The input consists of states and actions from various robot embodiments. These are tokenized into joint-level representations before being processed by a state encoder which identifies embodiment-specific knowledge and shared knowledge. A matching-based policy network then generates actions based on the encoded states and a small number of demonstrations.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller model. It shows how the input states and actions from diverse robotic embodiments are first converted into joint-level representations. These representations are then fed into a state encoder, which extracts features capturing both shared physics and embodiment-specific characteristics. Finally, a matching-based policy network uses a few demonstrations to predict appropriate actions for new tasks and unseen embodiments.

This figure shows a schematic of the Meta-Controller framework. It illustrates how the states and actions of robots are tokenized into joint-level representations, which are then encoded by a state encoder to capture both embodiment-specific and shared knowledge. The encoded states, along with few-shot demonstrations, are used by a matching-based policy network to predict actions at the joint level. This approach allows for generalization to unseen embodiments and tasks.

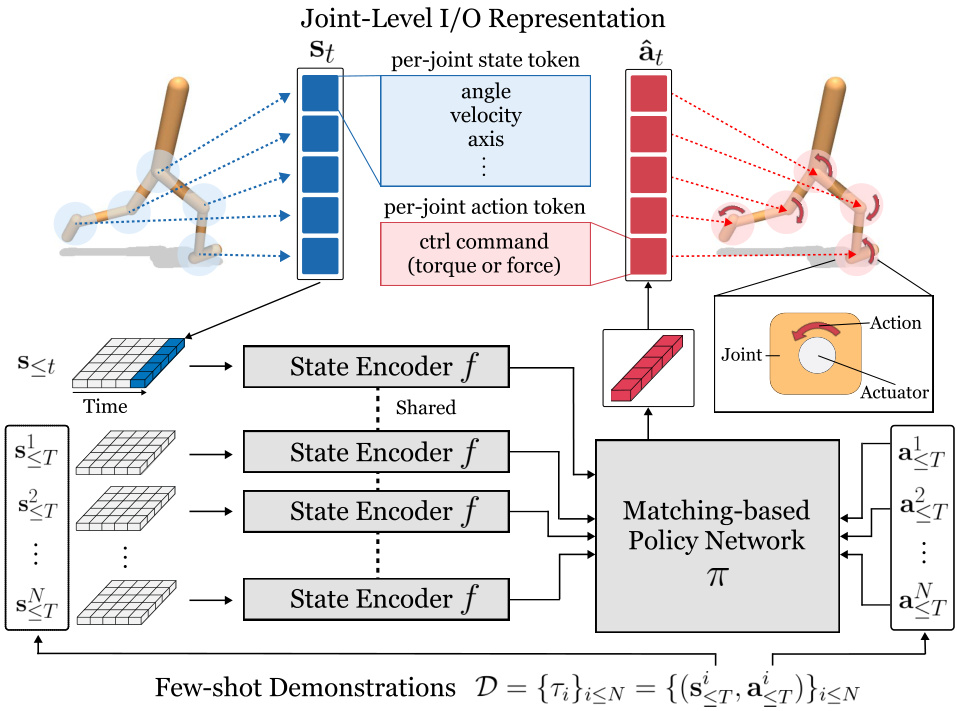

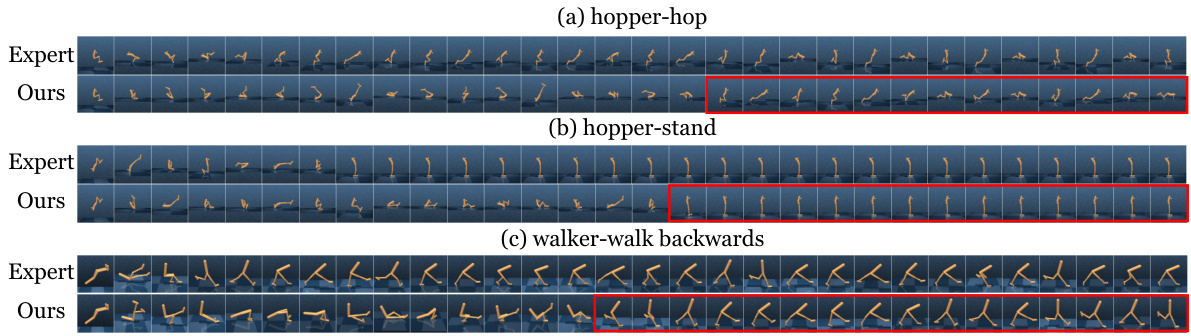

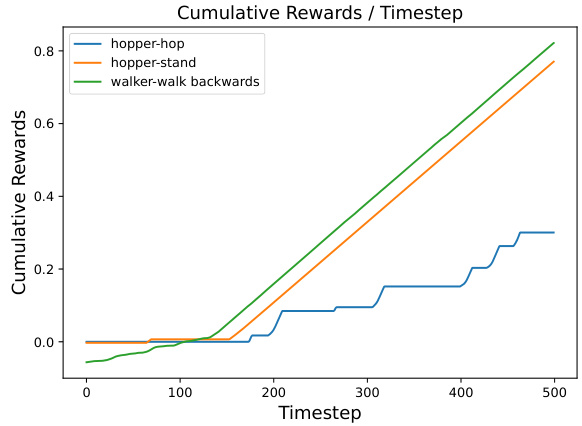

This figure shows the cumulative rewards over time for the failure cases illustrated in Figure 8. It provides a visual representation of the agent’s performance in scenarios where it struggled initially but eventually achieved success. The plot helps in analyzing the agent’s learning curve and identifying potential areas for improvement.

This figure shows a schematic of the Meta-Controller framework. It starts by tokenizing the states and actions from various robot embodiments into a joint-level representation. These tokens are fed into a state encoder, which extracts features capturing both embodiment-specific and shared knowledge. Finally, a matching-based policy network predicts actions based on these encoded features and a few demonstration examples.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller framework. It shows how the states and actions of robots are tokenized at the joint level, then encoded to capture both shared and embodiment-specific knowledge, and finally used by a matching-based policy network to predict actions from a few demonstrations.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller, a framework designed for few-shot imitation learning. It takes as input the states and actions of a robot, which are first converted into joint-level representations. A state encoder processes these representations to capture both shared and embodiment-specific knowledge, which is then used by a matching-based policy network to predict actions based on a small number of demonstrations. This modular approach enables the framework to generalize effectively to unseen embodiments and tasks.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the Meta-Controller, a novel framework for few-shot imitation learning. The framework begins by representing robot states and actions at the joint level, creating a unified representation regardless of the robot’s specific morphology. A state encoder then processes these joint-level states, capturing both general physical principles and robot-specific characteristics. Finally, a matching-based policy network utilizes a small number of demonstrations to predict actions based on these encoded states. This allows for generalization to unseen embodiments and tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of the Meta-Controller, a few-shot behavior cloning framework. It consists of three main components: joint-level tokenization of states and actions, a state encoder to extract features that capture knowledge about the robot embodiments, and a matching-based policy network that predicts actions based on a few demonstrations. The framework aims to generalize to unseen robot embodiments and tasks using a few demonstrations.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the Meta-Controller model. It shows how the model processes the input (states and actions of a robot) through tokenization, encoding, and a matching-based policy network to produce output (actions). The joint-level representation and state encoder are highlighted as key components for generalization across different robot embodiments.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller, a novel framework for few-shot behavior cloning that generalizes to unseen embodiments and tasks. It shows a three-stage process: First, the states and actions of different robots are converted into a unified joint-level representation. Then, a state encoder processes this representation to extract features capturing both embodiment-specific and shared knowledge. Finally, a matching-based policy network utilizes these features and a small number of demonstrations to predict the robot’s actions in a new, unseen situation.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Meta-Controller model. The model takes in joint-level state and action representations as inputs. A state encoder processes the state information to capture both shared and embodiment-specific knowledge. A matching-based policy network then uses few-shot demonstrations to predict the actions at the joint level.

This figure shows a schematic of the Meta-Controller framework, illustrating the process of how it handles different robot embodiments and tasks for few-shot imitation learning. First, the robot’s state and actions are broken down into joint-level representations which are then encoded to capture both shared and embodiment-specific knowledge. A matching-based policy network then uses this information to predict actions based on a few demonstrations.

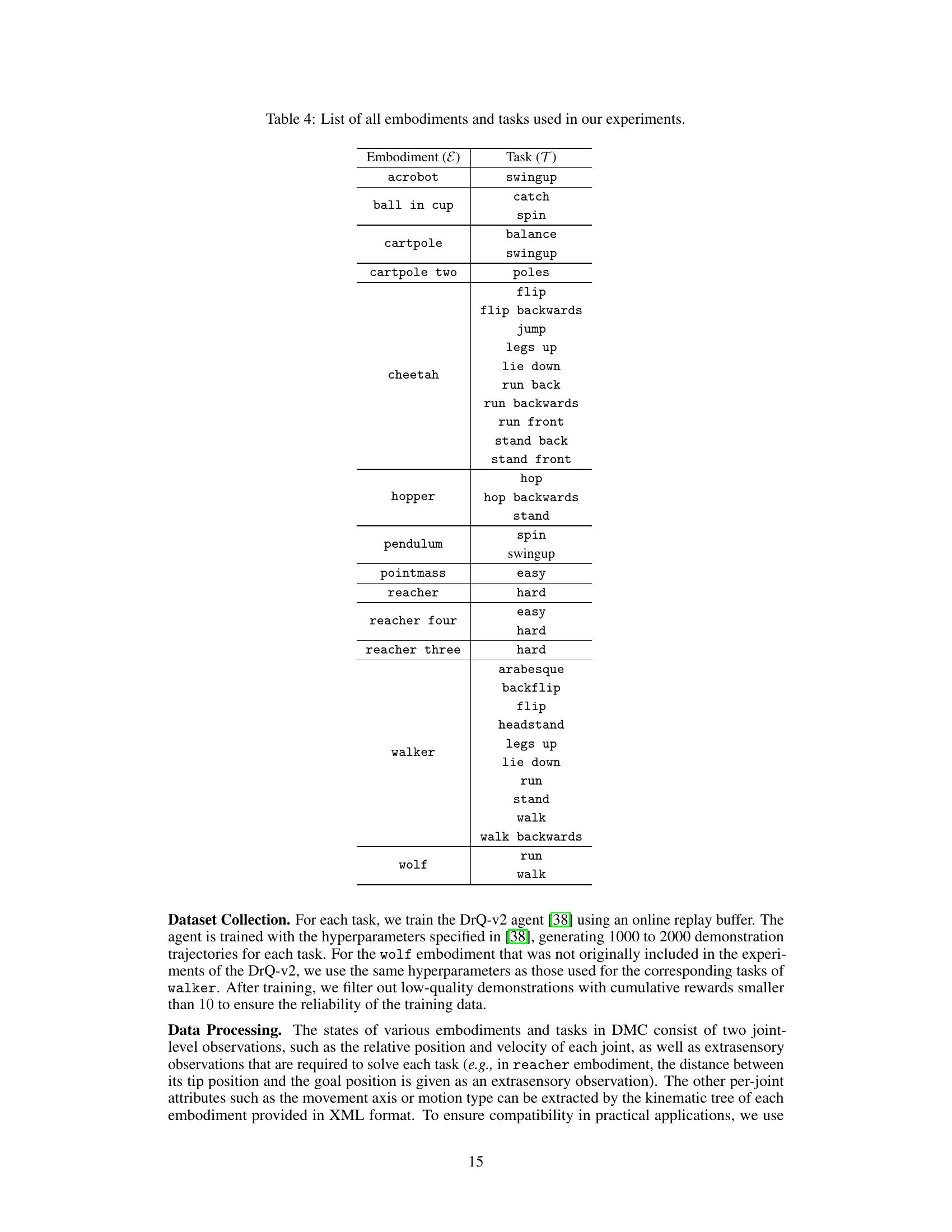

More on tables

This table presents the results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baselines across various continuous control tasks with unseen and seen robot embodiments. The table shows the normalized scores (a higher score indicates better performance) for each model on different tasks and embodiments, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the few-shot generalization capabilities.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. The table compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baselines across various tasks and embodiments, both seen and unseen during training. The results are presented as normalized scores (mean ± standard error), reflecting the average cumulative rewards achieved by each model on each task and embodiment. The table highlights the superior performance of the Meta-Controller in achieving few-shot generalization across heterogeneous embodiments and tasks.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baseline methods across various tasks and embodiments. The results are shown as the normalized average score (with standard error) for each task and embodiment combination, allowing for a direct comparison of the model’s performance relative to different baselines.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baseline methods (FS-DT, MT-DT, PDT, PDT+PEFT, HDT, L2M, MetaMorph, MTGv2) across various continuous control tasks and robot embodiments. The results are organized by embodiment (e.g., hopper, wolf, reacher-four, walker) and task (e.g., hop, run, walk). The average performance across all tasks and embodiments is also reported. The table highlights the superior performance of the Meta-Controller model in few-shot behavior cloning scenarios, particularly in generalizing to unseen embodiments and tasks.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller method against several baselines across various tasks and unseen robot embodiments. The metrics used are the average normalized scores for each task, calculated considering 20 different initial states. The table allows for a direct comparison of the Meta-Controller’s few-shot generalization capabilities against state-of-the-art methods in handling unseen robots and tasks.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baselines across various continuous control tasks involving different robot embodiments (both seen and unseen during training). The results are presented as normalized scores (mean ± standard error) for each task and embodiment, allowing for a comparison of generalization capabilities across different robot morphologies and task types. The average score across all tasks is also provided for each model and embodiment.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baselines across various tasks and embodiments. The table shows the average normalized scores (with standard errors) for each model on different tasks and embodiments, including both seen and unseen ones. This allows for a direct comparison of the generalization capabilities of each method in a few-shot learning setting. The embodiments are categorized as unseen or seen, and tasks are categorized by difficulty (easy or hard).

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baseline methods across various tasks and unseen robot embodiments. The table shows the average normalized score (higher is better) for each model on a set of tasks grouped by robot embodiment (seen vs. unseen). The results demonstrate the superior performance of the Meta-Controller in few-shot generalization to both unseen embodiments and tasks.

This table presents the quantitative results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted using the DeepMind Control (DMC) suite. It compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller method against several baseline methods across various tasks and robot embodiments. The table shows the average normalized scores (with standard errors) for each method, broken down by embodiment (hopper, wolf, reacher-four, walker) and task (hop, hop-bwd, stand, walk, run, easy, hard, walk-bwd). Higher scores indicate better performance.

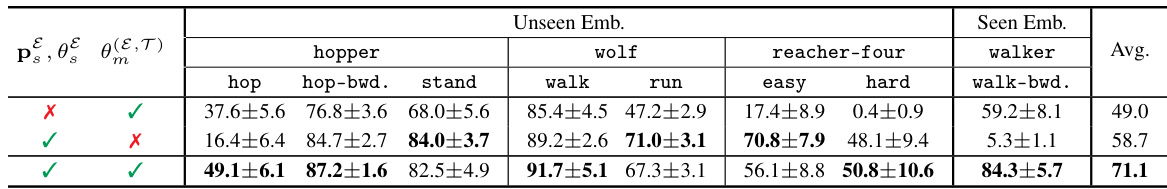

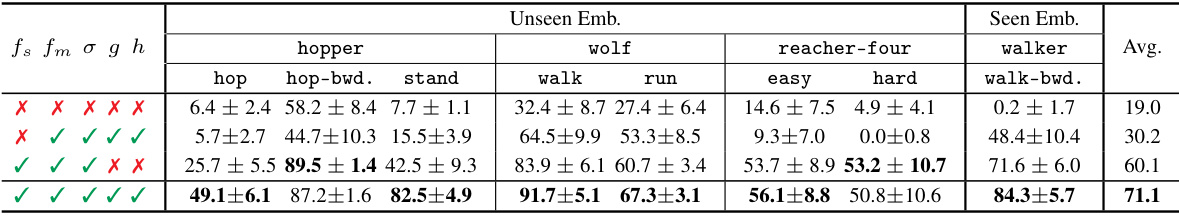

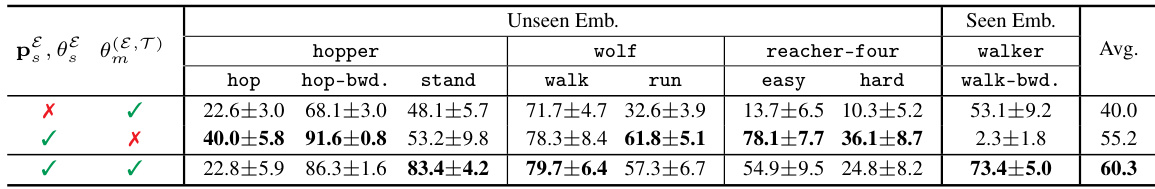

This table presents the ablation study results on the architectural components of the Meta-Controller model. It shows the performance of different model variants when key components such as the structure encoder (fs), motion encoder (fm), action encoder (g), action decoder (h), and matching module (σ) are removed or replaced with linear layers. The results demonstrate the importance of each component for generalization to unseen embodiments and tasks.

This table presents the results of 5-shot behavior cloning experiments conducted on the DeepMind Control suite. The table compares the performance of the proposed Meta-Controller model against several baselines across various continuous control tasks and robot embodiments. Performance is measured using a normalized score, considering both seen and unseen embodiments and tasks. The results highlight the superior few-shot generalization capabilities of the Meta-Controller.

Full paper#