TL;DR#

Sign language translation (SLT) struggles with limited data and narrow domains, hindering progress. Existing methods often fall short in open-domain scenarios, making translation across numerous sign and spoken languages especially challenging. This limitation stems from the scarcity of high-quality SLT data and the cross-modality challenges of translating video input to text output.

This research tackled these issues by employing a large-scale SLT pretraining approach. The method involves using a unified encoder-decoder framework, incorporating different data sources like noisy multilingual YouTube data, parallel text corpora, and SLT data augmented by off-the-shelf machine translation. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of this scaling approach across various SLT benchmarks, significantly surpassing previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) results. This achievement highlights the potential of data and model scaling for improving SLT, and opens new opportunities for future research in cross-lingual transfer and handling noisy, real-world data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in sign language translation (SLT) due to its significant advancements in addressing the field’s limitations. It demonstrates how scaling data, model size, and the number of languages can drastically improve SLT performance, exceeding previous state-of-the-art results by a wide margin. This opens new avenues for research into large-scale multilingual SLT and cross-modal transfer learning, particularly focusing on improving low-resource languages and handling the challenges of noisy, open-domain data. The paper’s findings directly contribute to current efforts in bridging the modality gap between video and text by leveraging massive data and large language models, providing a crucial benchmark for future research.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure compares the BLEU scores achieved by the proposed model and the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on various sign language translation benchmarks. The benchmarks include How2Sign ASL, Elementary23 GSS, WMT23 LIS-CH, WMT23 LSF-CH, and WMT23 DSGS (both SRF and SS splits). The radar chart visually represents the performance of both the proposed model and the SOTA on each benchmark. The significantly higher scores of the proposed model in the blue line compared to the previous SOTA in red show substantial improvements in translation quality across all benchmarks. The absence of BLEURT scores is noted, as not all prior studies reported them.

read the caption

Figure 1: BLEU scores on different benchmarks: our model sets new SOTA results across benchmarks and sign languages. Note we didn't show BLEURT because not all previous studies report BLEURT.

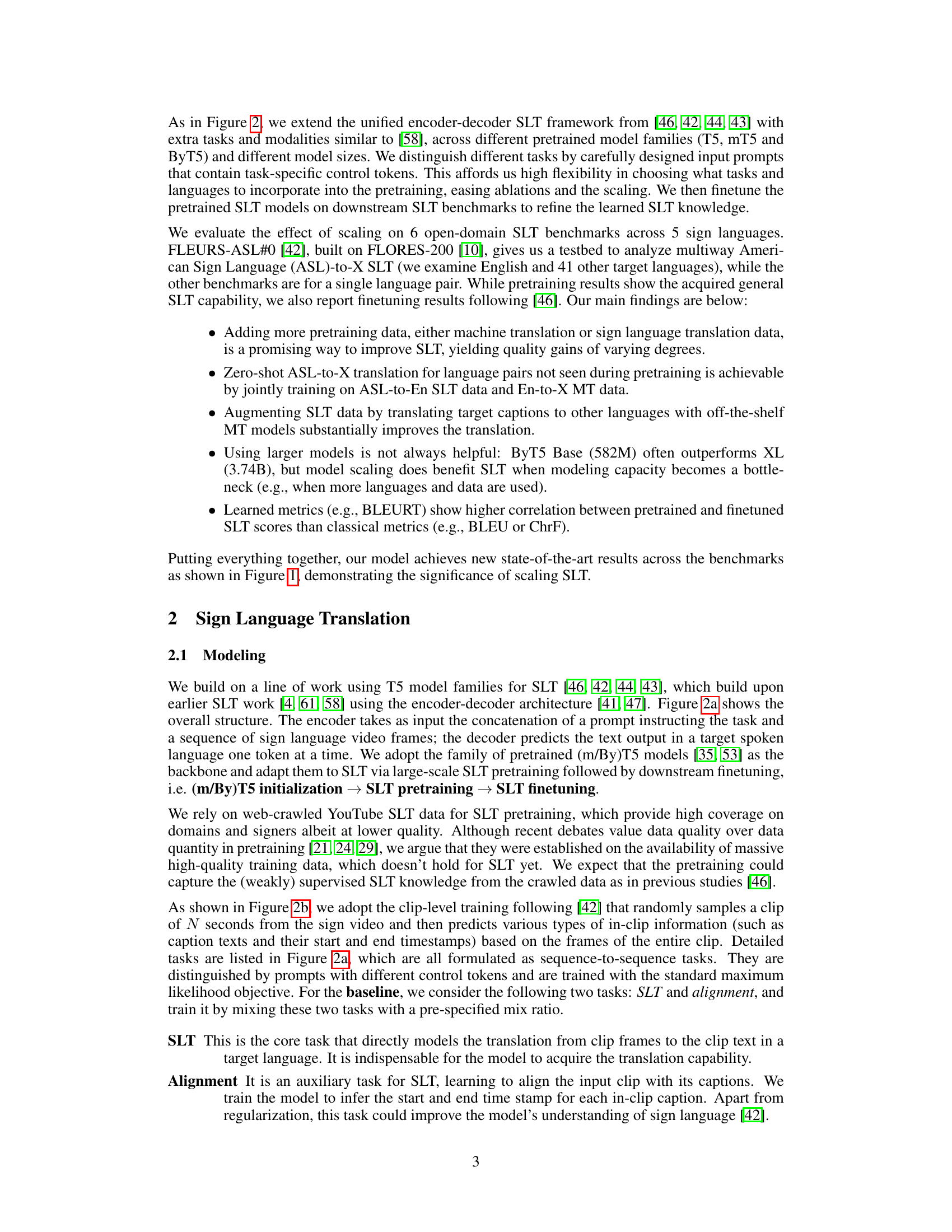

🔼 This table presents a summary of six open-domain sign language translation (SLT) benchmarks used to evaluate the model’s performance. Each benchmark is described by the sign language, the target spoken language, and the number of training, development, and testing examples. It highlights the datasets’ characteristics: pre-segmented and aligned data at the sentence level, and the specific sign languages involved (ASL, GSS, LIS-CH, LSF-CH, DSGS).

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of downstream SLT benchmarks. '#Train/#Dev/#Test': the number of examples in the train, dev and test split. Note the sign language video and the target text in these benchmarks are often pre-segmented and aligned at sentence level. 'DGS/ASL/GSS': German/American/Greek Sign Language; 'En/De/Fr/It': English/German/French/Italian; “LIS-CH': Italian Sign Language of Switzerland; 'LSF-CH': French Sign Language of Switzerland; 'DSGS': Swiss German Sign Language.

In-depth insights#

SLT Scaling#

The concept of ‘SLT Scaling’ in the context of sign language translation (SLT) research points towards a significant paradigm shift. It involves systematically expanding various aspects of the SLT process to improve performance and capabilities. This scaling encompasses several key dimensions: Firstly, data scaling which focuses on leveraging larger and more diverse datasets, including noisy web-crawled data and augmented SLT data generated through machine translation. Secondly, model scaling involves utilizing larger neural network architectures, enabling the models to capture more intricate patterns and relationships within the data. Finally, language scaling aims to extend SLT capabilities beyond a few sign languages to encompass a broader range, promoting cross-lingual knowledge transfer and facilitating zero-shot translation to new languages. The successful implementation of SLT scaling relies heavily on the integration of these three factors. ByT5 models were employed to demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach, achieving state-of-the-art results across multiple benchmarks. The research emphasizes the feasibility of zero-shot SLT by pretraining models on a wide array of data, including machine translation data. While the study demonstrates remarkable progress in SLT, it also acknowledges the limitations associated with data quality and model size.

Multimodal Pretraining#

Multimodal pretraining, in the context of sign language translation (SLT), is a powerful technique that leverages the strengths of both visual and textual data to improve model performance. Instead of training separate models for visual feature extraction and text processing, multimodal pretraining integrates these modalities. By jointly training on large-scale datasets combining sign language videos and their corresponding text transcriptions, the model learns richer representations that capture complex relationships between visual gestures and linguistic meaning. This approach addresses the challenges posed by the inherent cross-modal nature of SLT. The advantages of multimodal pretraining are significant: it allows the model to learn more robust features, handle noise in the data more effectively, and potentially generalize to unseen sign languages or domains with improved zero-shot capabilities. Furthermore, it enables cross-lingual transfer learning, where knowledge gained from one language pair can be leveraged to improve performance on others, particularly beneficial for low-resource languages. However, effective multimodal pretraining necessitates substantial computational resources and carefully curated datasets, potentially presenting significant challenges in terms of data acquisition and model training.

Zero-Shot SLT#

Zero-shot sign language translation (SLT) is a fascinating area of research focusing on a model’s ability to translate between sign languages and spoken languages it has never seen before. This capability is highly desirable as it reduces the need for extensive, paired training data for each new language pair, which is often scarce and costly to obtain. The paper explores the potential of large-scale pre-training to enable zero-shot SLT. By training a model on a diverse range of sign and spoken languages, with various tasks, the model learns cross-lingual and cross-modal representations that can generalize to unseen language pairings. The use of task-specific prompts in the pre-training phase further enables the model to adapt to different translation scenarios. However, the results of zero-shot SLT are not perfect and often lower in quality than models fine-tuned on specific language pairs, indicating that the model’s capacity for generalization has limitations. Future research directions may involve improving the scalability and efficiency of pretraining, focusing on methods that facilitate better cross-lingual transfer and enhance the model’s ability to handle the unique challenges of sign language processing, such as the multimodal nature of sign and the challenges in obtaining well-aligned data across different languages. Ultimately, the successful implementation of zero-shot SLT has the potential to significantly improve accessibility of information for the Deaf community by making translation technology more readily available across a wider range of languages.

Model Scaling Effects#

The analysis of model scaling effects reveals a complex relationship between model size and performance in sign language translation (SLT). While larger models often offer increased capacity, results show that the simple increase in model size does not guarantee better performance in SLT; in fact, smaller models sometimes outperform larger ones. This unexpected finding highlights the unique challenges of SLT which involve handling the cross-modal nature of video and text data, unlike standard text-based machine translation tasks. The optimal model size seems contingent on other factors, such as the amount of training data and the number of languages considered. For instance, when dealing with more languages and/or more data, larger models start to show their advantage by enabling effective knowledge transfer across languages. The study emphasizes the importance of a holistic approach to SLT scaling, where data and language diversity play as crucial a role as model size in achieving improved accuracy and efficiency. Further research could delve deeper into these interactions to provide more specific guidance on model selection for SLT.

Future of SLT#

The future of Sign Language Translation (SLT) is bright, driven by several key factors. Scaling up data is crucial, moving beyond limited datasets to leverage the vast resources available on platforms like YouTube. Multi-lingual and cross-modal approaches, training models on multiple sign and spoken languages simultaneously, are essential for broader accessibility. Improved model architectures are needed, potentially surpassing the current encoder-decoder paradigm for more sophisticated semantic understanding. Better evaluation metrics than current BLEU scores will facilitate progress, accurately reflecting the nuanced nature of SLT. Finally, ethical considerations must be central: ensuring fairness, addressing biases in existing data, and promoting the development of inclusive, equitable SLT systems for diverse Deaf communities worldwide.

More visual insights#

More on figures

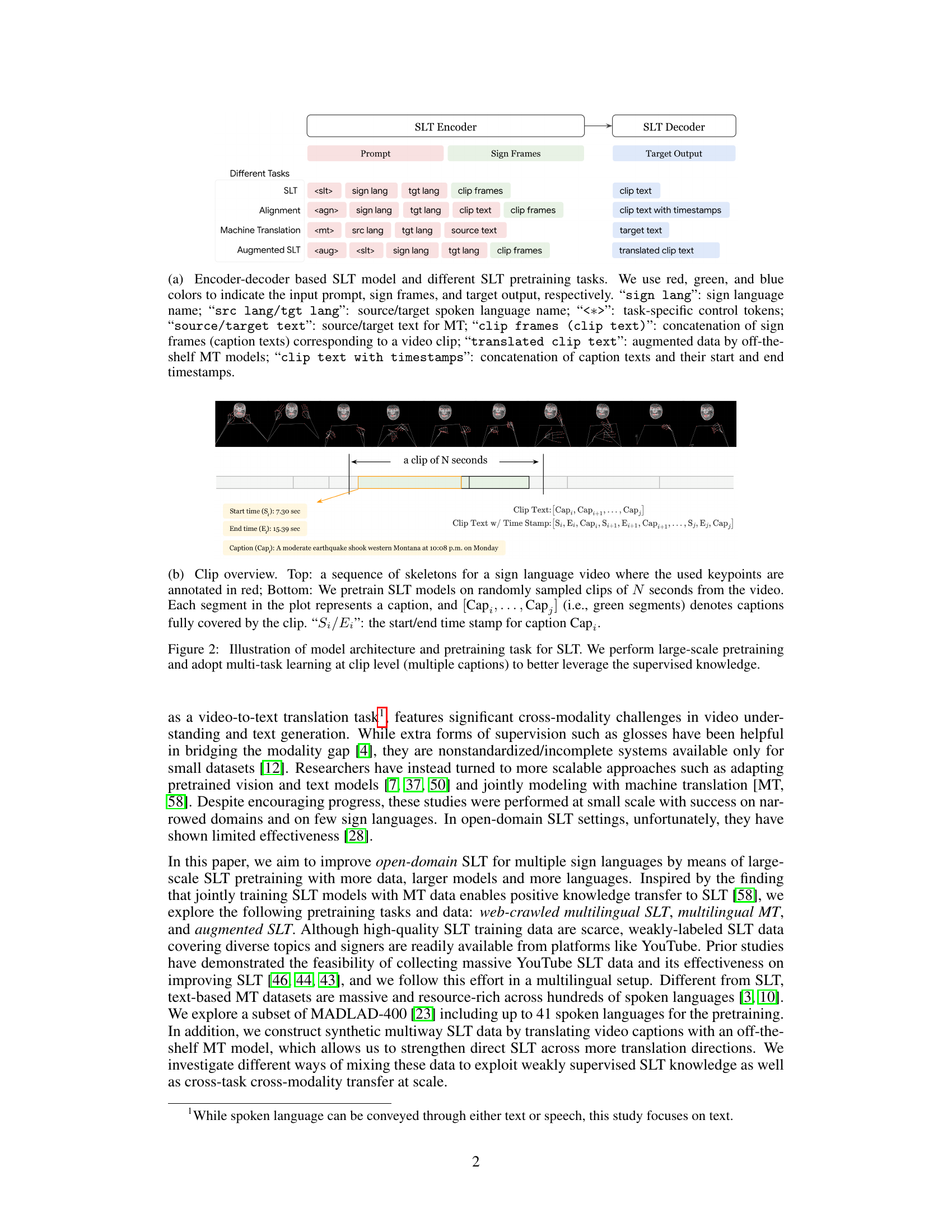

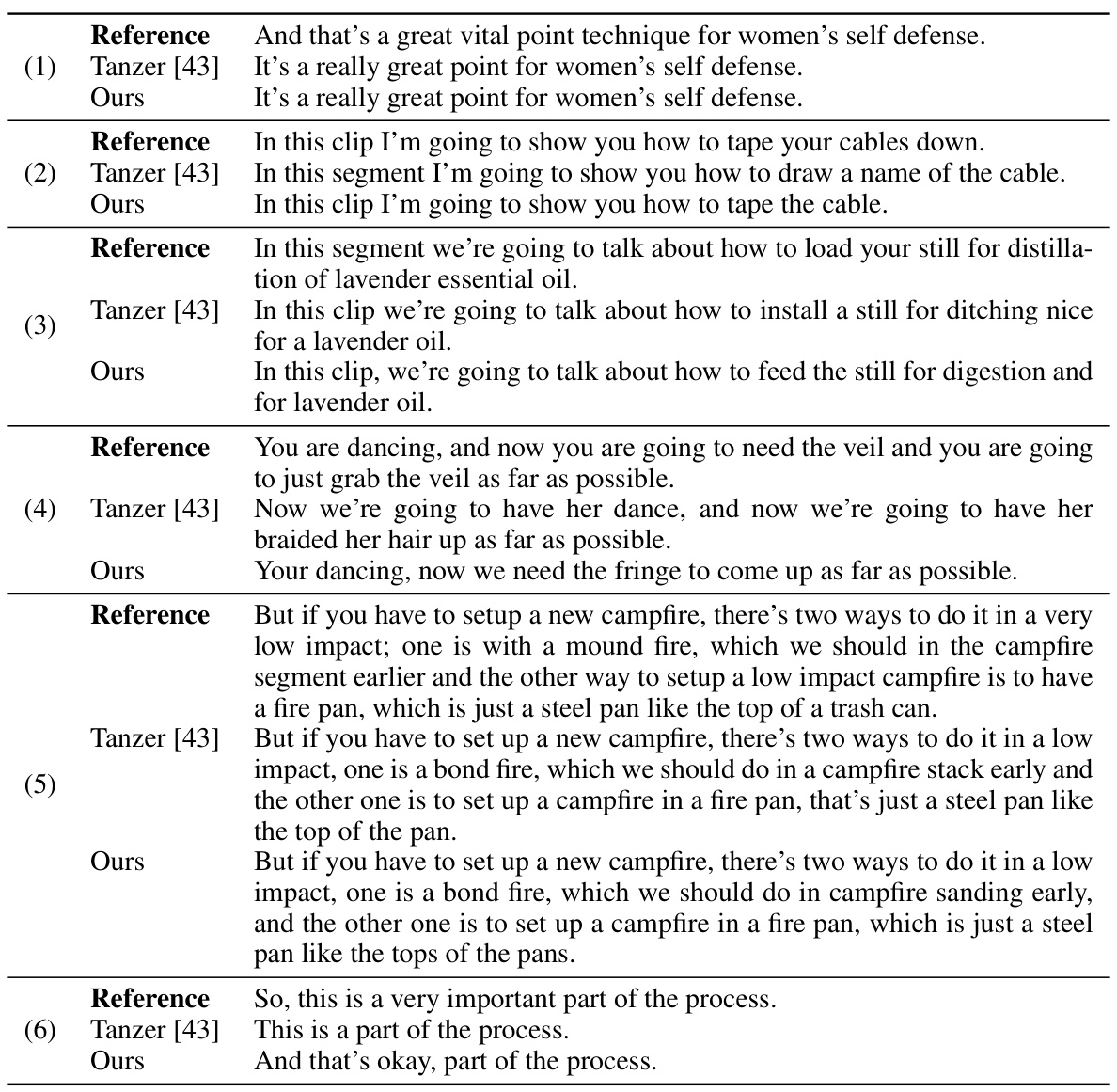

🔼 This figure illustrates the encoder-decoder architecture used for sign language translation (SLT). It highlights the different input components for various tasks during pretraining: SLT (sign language translation), alignment (aligning video clips with captions), machine translation (MT), and augmented SLT (data augmentation via off-the-shelf machine translation). Each task utilizes task-specific prompts, sign frames, and produces corresponding target outputs. The multi-task learning approach at the clip level (multiple captions) enhances the model’s learning by leveraging supervised knowledge from various sources. The figure shows how the model takes as input the sign frames and a prompt specifying the task, and outputs the translated text. The diagram shows the different data types used in the pretraining phase, which include sign language video frames, captions, and machine-translated text from other languages.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of model architecture and pretraining task for SLT. We perform large-scale pretraining and adopt multi-task learning at clip level (multiple captions) to better leverage the supervised knowledge.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the encoder-decoder based sign language translation (SLT) model and the different pretraining tasks used. The encoder takes as input sign frames and a prompt specifying the task (SLT, Machine Translation (MT), Alignment, or Augmented SLT). The decoder outputs the target text. The figure also shows how video clips are segmented for training, focusing on using multiple captions per clip and their timestamps for more effective training.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of model architecture and pretraining task for SLT. We perform large-scale pretraining and adopt multi-task learning at clip level (multiple captions) to better leverage the supervised knowledge.

🔼 This figure compares the BLEU scores achieved by the proposed model and the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several sign language translation benchmarks. The benchmarks cover different sign languages (LIS-CH, LSF-CH, DSGS, ASL) and target languages. The results demonstrate that the proposed model significantly outperforms the SOTA on all benchmarks.

read the caption

Figure 1: BLEU scores on different benchmarks: our model sets new SOTA results across benchmarks and sign languages. Note we didn't show BLEURT because not all previous studies report BLEURT.

🔼 This figure presents a bar chart comparing the BLEU scores achieved by the proposed model against the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) across various sign language translation benchmarks (WMT23 LIS-CH, Elementary23 GSS, WMT23 LSF-CH, How2Sign ASL, WMT23 DSGS (SRF), WMT23 DSGS (SS)). The chart visually demonstrates that the proposed model significantly outperforms the SOTA on all benchmarks, showcasing substantial improvements in sign language translation quality. The absence of BLEURT scores is noted due to inconsistent reporting in prior research.

read the caption

Figure 1: BLEU scores on different benchmarks: our model sets new SOTA results across benchmarks and sign languages. Note we didn't show BLEURT because not all previous studies report BLEURT.

🔼 This figure presents the BLEU scores achieved by the proposed model and the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several sign language translation (SLT) benchmarks. Each bar represents a different benchmark dataset, and the height of the bar shows the BLEU score. The results demonstrate that the new model significantly outperforms the SOTA models on all benchmarks across different sign languages. BLEURT scores were not included because not all previous studies reported them.

read the caption

Figure 1: BLEU scores on different benchmarks: our model sets new SOTA results across benchmarks and sign languages. Note we didn't show BLEURT because not all previous studies report BLEURT.

🔼 This figure compares the BLEU scores achieved by the proposed model against the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several benchmark datasets for sign language translation. Each bar represents a different benchmark dataset, and the height of the bar indicates the BLEU score. The model significantly outperforms SOTA across all benchmarks. The figure highlights the substantial improvements achieved by the proposed approach, particularly in achieving new SOTA results on several benchmark datasets.

read the caption

Figure 1: BLEU scores on different benchmarks: our model sets new SOTA results across benchmarks and sign languages. Note we didn't show BLEURT because not all previous studies report BLEURT.

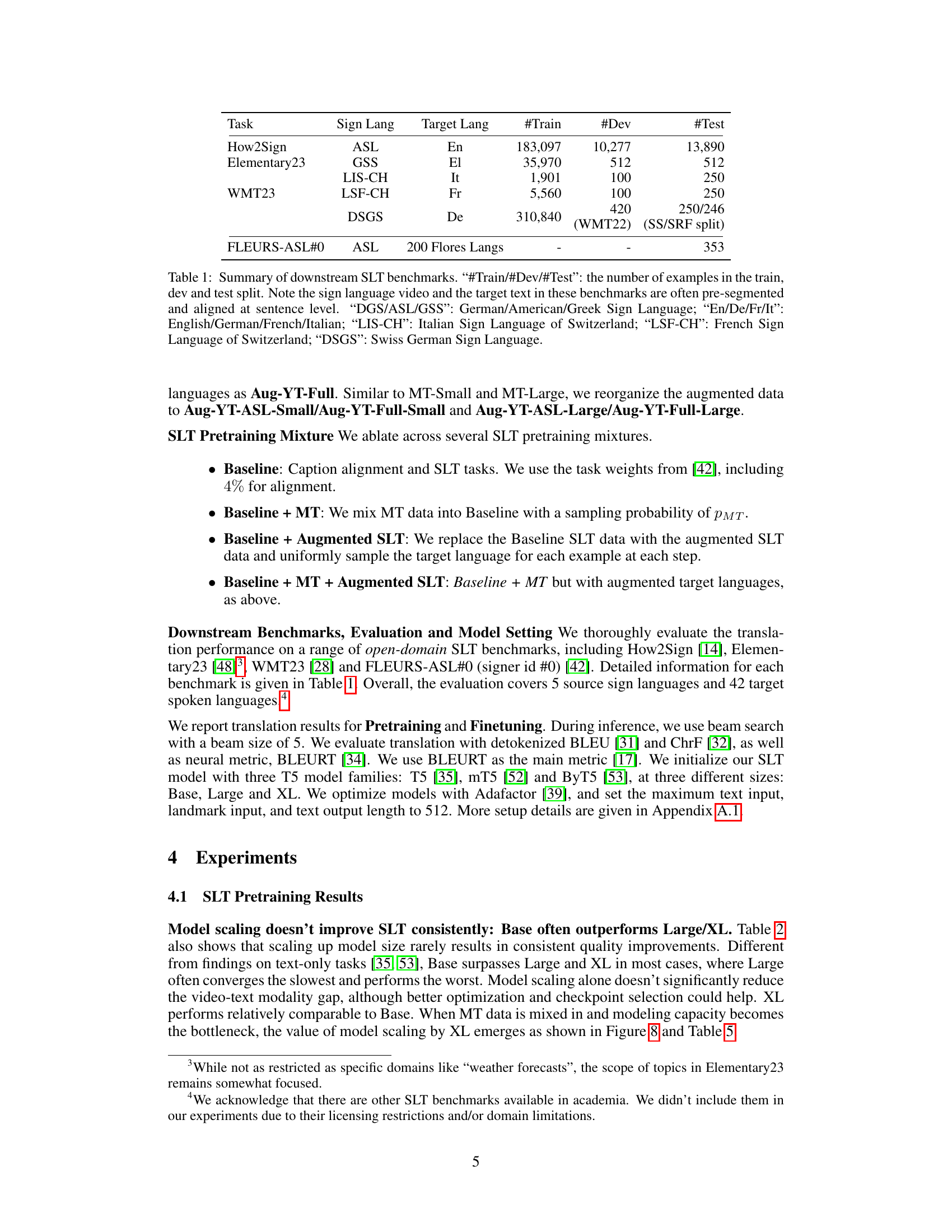

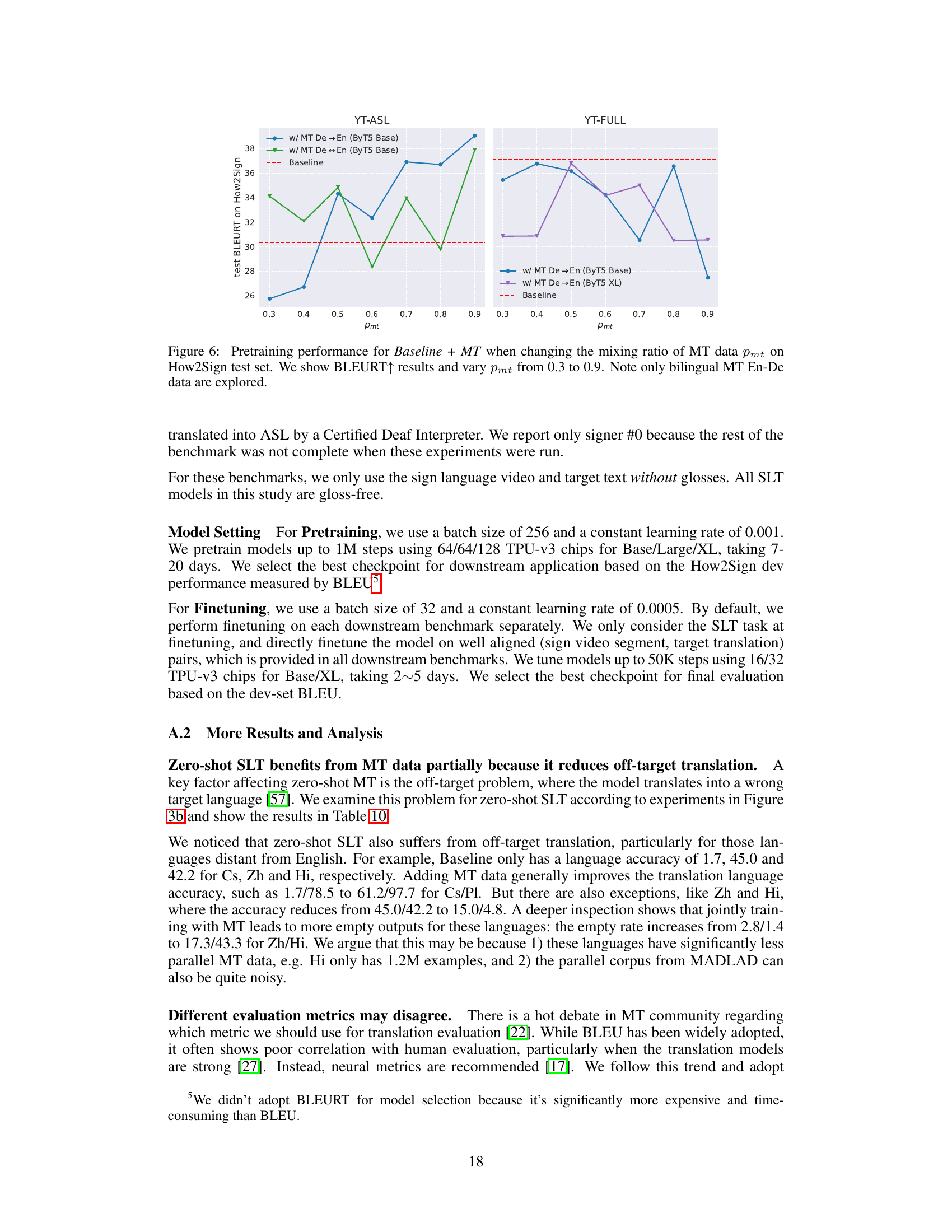

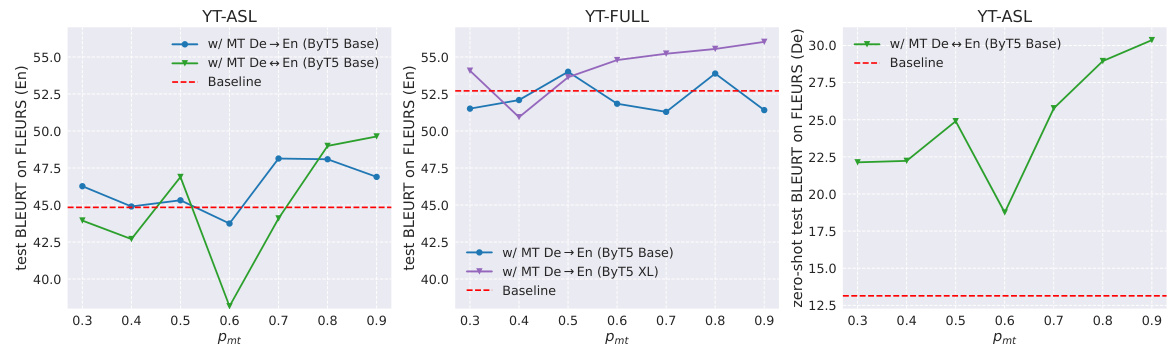

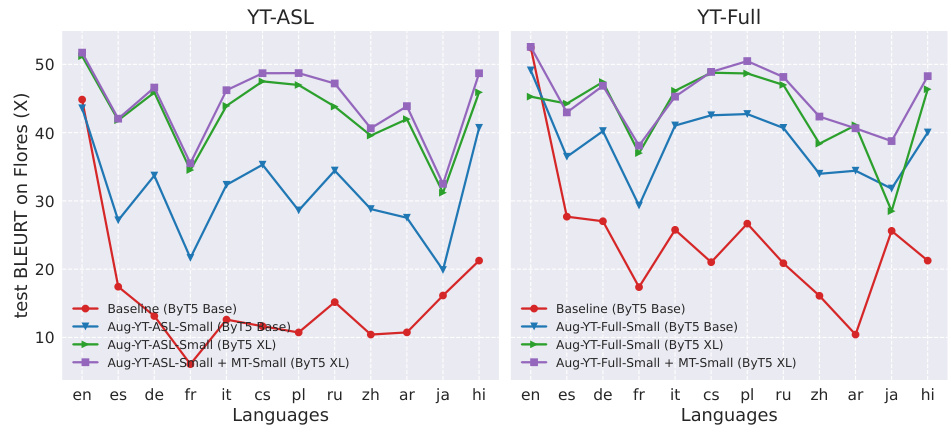

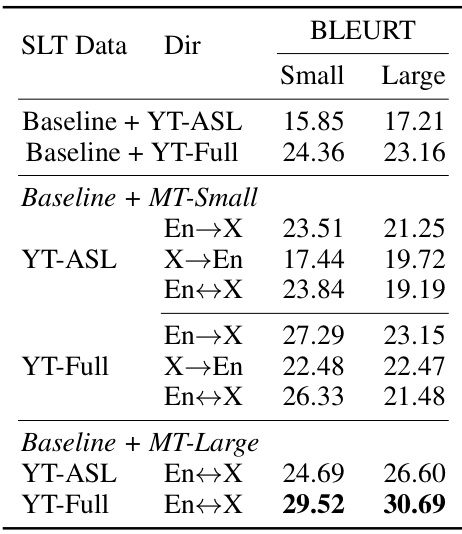

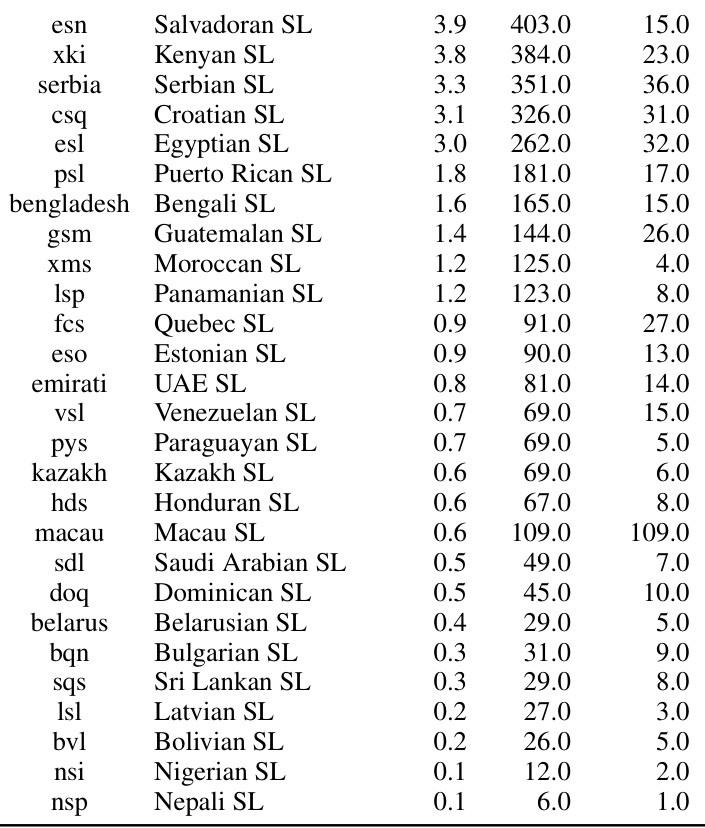

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments that investigate the impact of adding different Machine Translation (MT) languages to the Baseline model during the pretraining phase. The experiments utilize the BLEURT metric to measure the performance of the model on the FLEURS-ASL#0 benchmark. The parameter pmt is set to 0.5, indicating that the SLT and MT tasks are given equal weight. Two scenarios are explored: 1. Adding MT data that translates only into English (X→En). 2. Adding MT data that translates both into and from English (X↔En). The results are presented for each MT language individually, alongside the average across languages. The order of MT languages shown on the x-axis is determined by the amount of training data used. The figure clearly demonstrates how different MT languages impact the performance of the SLT model, and how the directionality of MT data (X→En versus X↔En) influences the results.

read the caption

Figure 3: Pretraining performance for Baseline + MT when varying MT languages. We show BLEURT↑ results on FLEURS-ASL#0, and set pmt = 0.5. Note MT languages are added separately instead of jointly. Results are for ByT5 Base. 'X→En': MT data for translation into English; 'X↔En': MT data for both translation directions; “Avg”: average performance over languages. MT languages are arranged in descending order from left to right based on their training data quantity.

🔼 This figure displays the impact of adding various machine translation (MT) languages on the performance of a sign language translation (SLT) model. Two experiments are shown: one translating to English only and the other performing zero-shot translation to multiple languages. The y-axis represents the BLEURT score (higher is better), while the x-axis lists the MT languages included, ordered by the amount of training data. The results demonstrate the effects of including multilingual MT data on SLT performance, highlighting that even adding a small amount of data from certain languages (e.g. Ja→En) results in significant quality improvements.

read the caption

Figure 3: Pretraining performance for Baseline + MT when varying MT languages. We show BLEURT↑ results on FLEURS-ASL#0, and set pmt = 0.5. Note MT languages are added separately instead of jointly. Results are for ByT5 Base. 'X→En': MT data for translation into English; 'X↔En': MT data for both translation directions; “Avg”: average performance over languages. MT languages are arranged in descending order from left to right based on their training data quantity.

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments evaluating the impact of incorporating machine translation (MT) data from various languages into a sign language translation (SLT) pretraining process. The results are measured using the BLEURT metric (higher is better). Two main scenarios are considered: MT data for translation into English only (X→En) and MT data for translation in both directions (X↔En). The figure shows that adding more MT languages generally improves the performance of the SLT model, although the effect varies by language. The average performance across all added MT languages is also shown.

read the caption

Figure 3: Pretraining performance for Baseline + MT when varying MT languages. We show BLEURT↑ results on FLEURS-ASL#0, and set pmt = 0.5. Note MT languages are added separately instead of jointly. Results are for ByT5 Base. 'X→En': MT data for translation into English; 'X↔En': MT data for both translation directions; “Avg”: average performance over languages. MT languages are arranged in descending order from left to right based on their training data quantity.

🔼 This figure displays the impact of adding Machine Translation (MT) data from various languages on the quality of sign language translation (SLT). It shows BLEURT scores (a metric assessing translation quality) for two scenarios: adding MT data only translating to English (X→En) and adding MT data for both translations to and from English (X↔En). The chart illustrates that adding more MT data generally improves SLT performance, although the effect varies across languages. The languages on the x-axis are ordered by the amount of training data available for them.

read the caption

Figure 3: Pretraining performance for Baseline + MT when varying MT languages. We show BLEURT↑ results on FLEURS-ASL#0, and set pmt = 0.5. Note MT languages are added separately instead of jointly. Results are for ByT5 Base. 'X→En': MT data for translation into English; 'X↔En': MT data for both translation directions; “Avg”: average performance over languages. MT languages are arranged in descending order from left to right based on their training data quantity.

More on tables

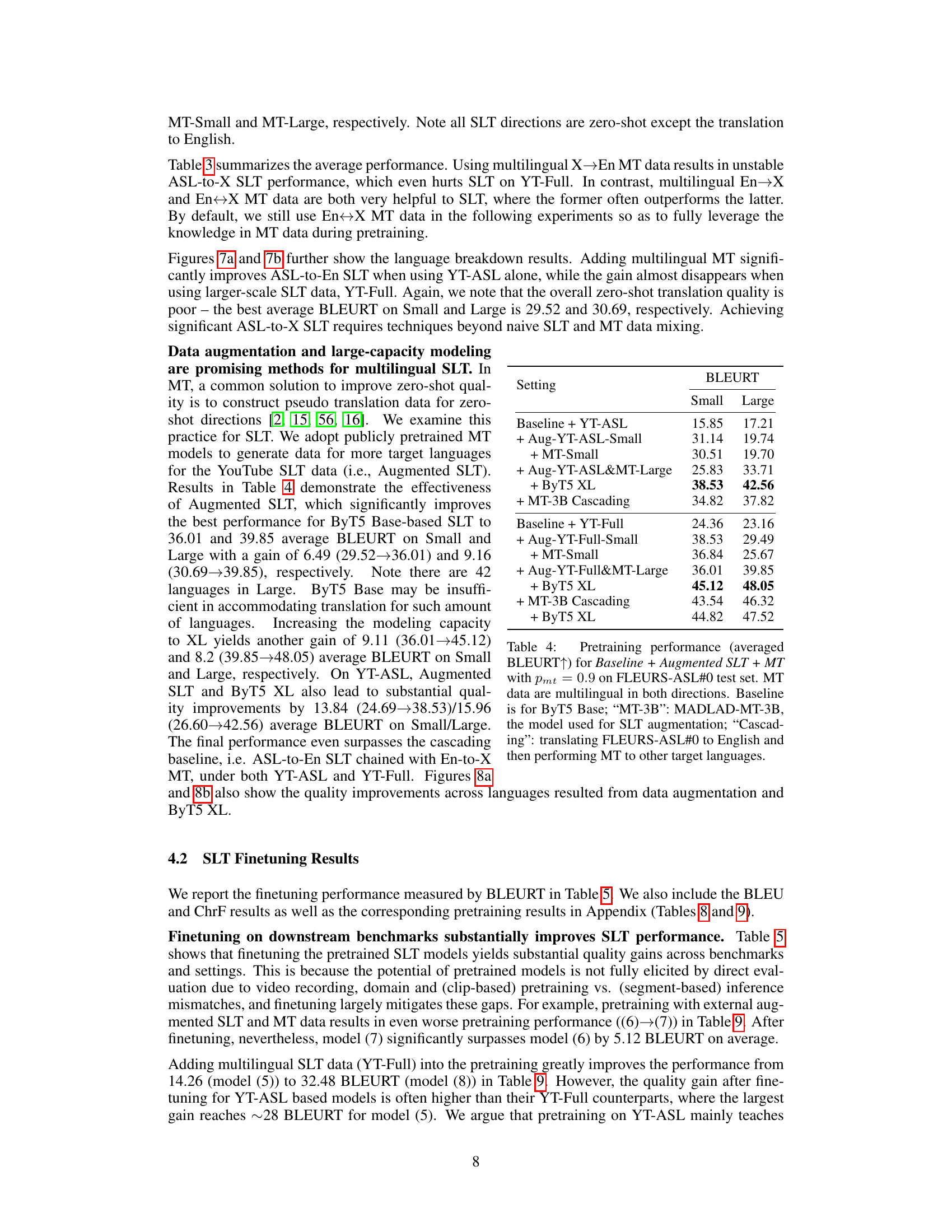

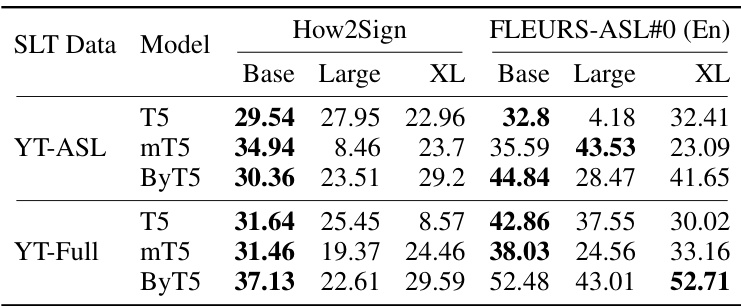

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved by different sized T5 model families (T5, mT5, and ByT5) after pretraining on two different datasets: YT-ASL and YT-Full. The evaluation is performed on two benchmarks: How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (with English as the target language). The best performing model for each family is highlighted in bold, showcasing the impact of model size and training data on performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Pretraining performance (BLEURT ↑) for different sized (By/m)T5 models when pretrained on YT-ASL and YT-Full. Results are reported on the test set of How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (→En, i.e. English as the target). Best results for each model family are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved by different sized ByT5 and mT5 models after pretraining on two datasets: YT-ASL and YT-Full. The evaluation was performed on the How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 benchmark datasets, with English as the target language. The best performing model within each family (ByT5 and mT5) is highlighted in bold. It demonstrates the impact of model size and data quantity on the pretraining performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Pretraining performance (BLEURT ↑) for different sized (By/m)T5 models when pretrained on YT-ASL and YT-Full. Results are reported on the test set of How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (→En, i.e. English as the target). Best results for each model family are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This table shows the BLEURT scores achieved by different sized models (T5, mT5, ByT5) pretrained on two different datasets (YT-ASL and YT-Full). The evaluation is performed on the How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 test sets, with English as the target language. The best results for each model family are highlighted in bold, indicating the optimal model size for each dataset and model type.

read the caption

Table 2: Pretraining performance (BLEURT ↑) for different sized (By/m)T5 models when pretrained on YT-ASL and YT-Full. Results are reported on the test set of How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (→En, i.e. English as the target). Best results for each model family are highlighted in bold.

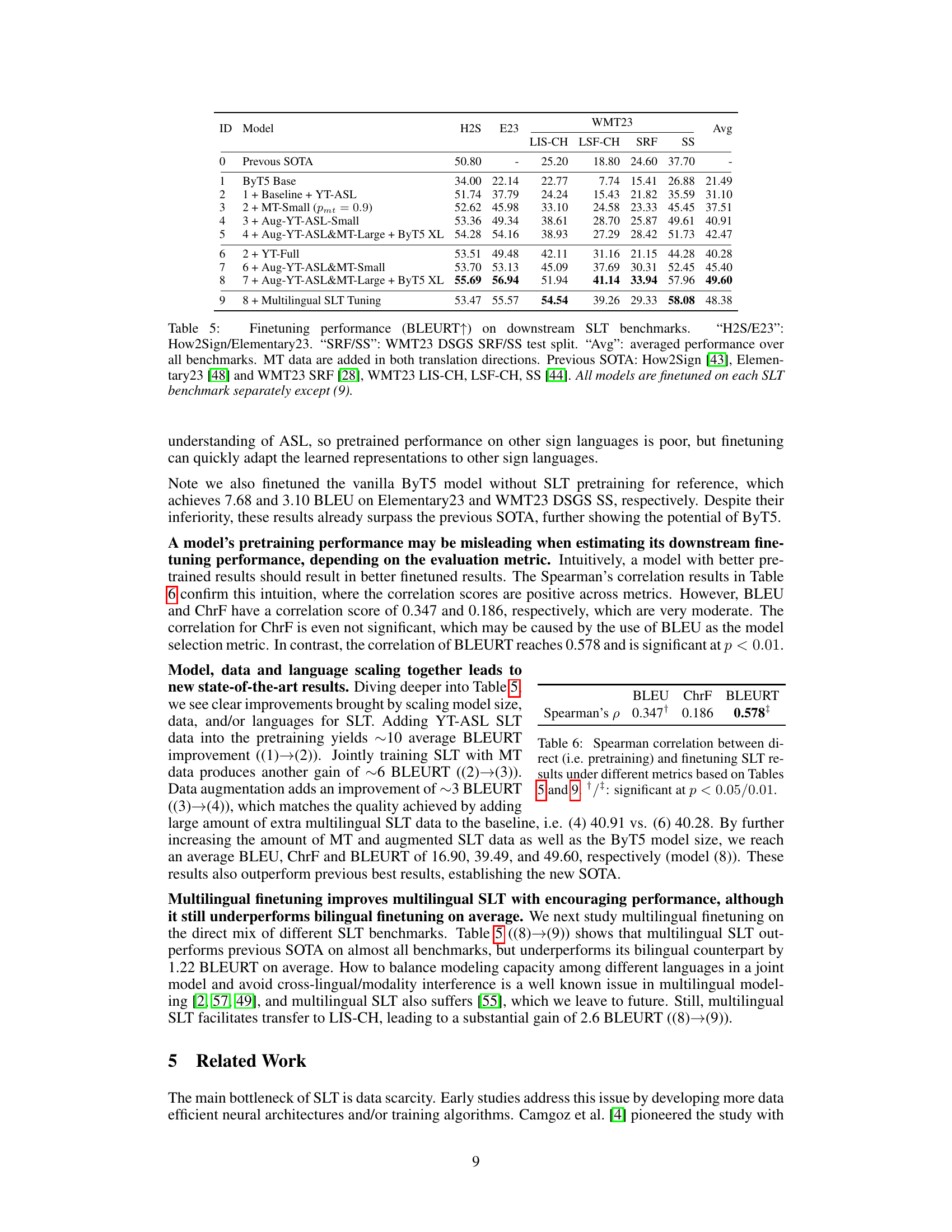

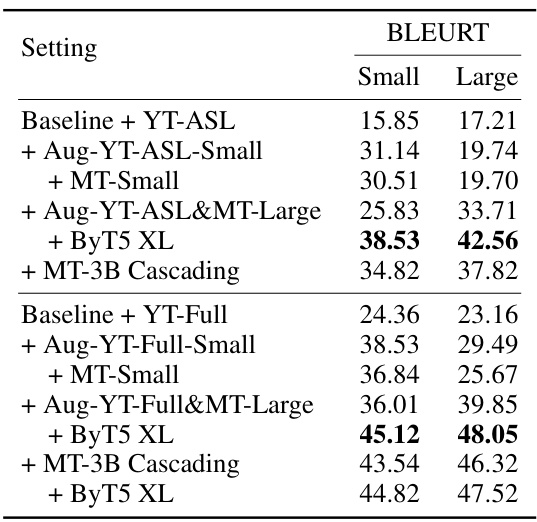

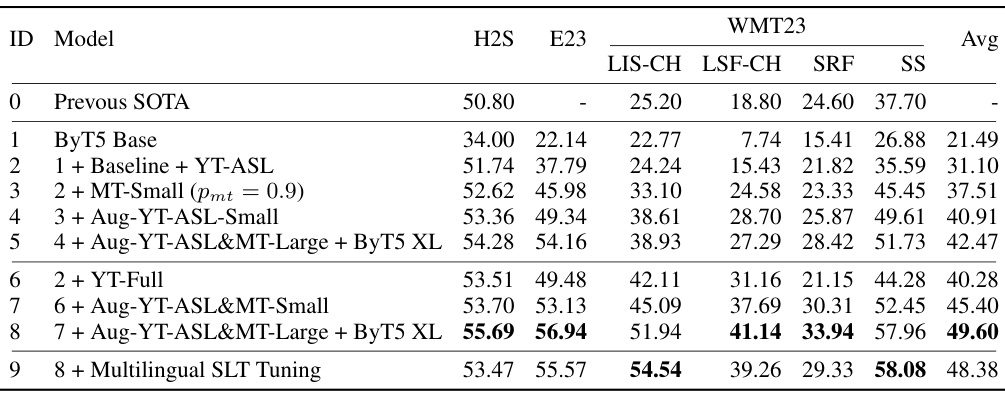

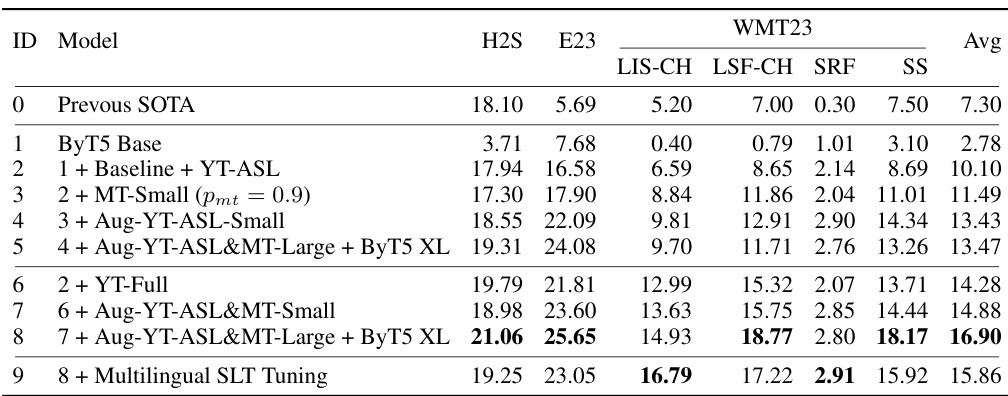

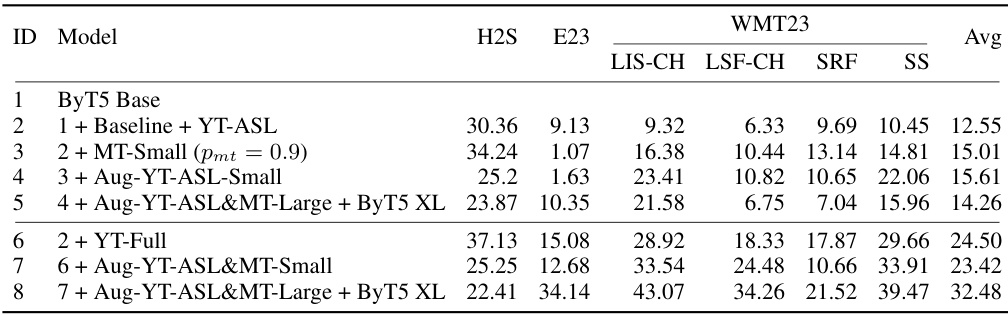

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved after fine-tuning various SLT models on six different downstream benchmarks. It compares the performance of different model configurations (ByT5 base model, with YT-ASL data, with MT data, etc.) against the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA). The benchmarks cover five different sign languages and include several different test set splits for evaluation. The final row shows that multilingual finetuning was also performed.

read the caption

Table 5: Finetuning performance (BLEURT↑) on downstream SLT benchmarks. 'H2S/E23': How2Sign/Elementary23. 'SRF/SS': WMT23 DSGS SRF/SS test split. 'Avg': averaged performance over all benchmarks. MT data are added in both translation directions. Previous SOTA: How2Sign [43], Elementary23 [48] and WMT23 SRF [28], WMT23 LIS-CH, LSF-CH, SS [44]. All models are finetuned on each SLT benchmark separately except (9).

🔼 This table presents the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between the pretraining and finetuning results for Sign Language Translation (SLT) using three different evaluation metrics: BLEU, ChrF, and BLEURT. The correlation coefficients indicate the strength of the relationship between the performance of the models in the pretraining phase and their performance after finetuning. The significance levels (p-values) are also provided, showing the statistical significance of the correlations. A high correlation suggests that the pretraining results are a good indicator of finetuned performance. The table helps to evaluate the effectiveness of the pretraining strategy for SLT and assess the predictive power of different evaluation metrics.

read the caption

Table 6: Spearman correlation between direct (i.e., pretraining) and finetuned SLT results under different metrics based on Tables 5 and 9. */* : significant at p < 0.05/0.01.

🔼 This table summarizes the six open-domain sign language translation (SLT) benchmarks used in the paper’s experiments. It provides details on the number of training, development, and test examples for each benchmark, indicating the sign language and target spoken language involved. Abbreviations for sign languages and their corresponding spoken languages are also included for clarity.

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of downstream SLT benchmarks. '#Train/#Dev/#Test': the number of examples in the train, dev and test split. Note the sign language video and the target text in these benchmarks are often pre-segmented and aligned at sentence level. 'DGS/ASL/GSS': German/American/Greek Sign Language; 'En/De/Fr/It': English/German/French/Italian; “LIS-CH': Italian Sign Language of Switzerland; 'LSF-CH': French Sign Language of Switzerland; 'DSGS': Swiss German Sign Language.

🔼 This table summarizes six open-domain sign language translation (SLT) benchmarks used in the paper to evaluate the performance of their proposed SLT model. It lists the sign language and target spoken language for each benchmark, along with the number of training, development, and test examples. The table also provides abbreviations for the sign languages (DGS, ASL, GSS) and spoken languages (En, De, Fr, It).

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of downstream SLT benchmarks. '#Train/#Dev/#Test': the number of examples in the train, dev and test split. Note the sign language video and the target text in these benchmarks are often pre-segmented and aligned at sentence level. 'DGS/ASL/GSS': German/American/Greek Sign Language; 'En/De/Fr/It': English/German/French/Italian; “LIS-CH': Italian Sign Language of Switzerland; 'LSF-CH': French Sign Language of Switzerland; 'DSGS': Swiss German Sign Language.

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved after fine-tuning various SLT models on six different benchmarks (How2Sign, Elementary23, and four WMT23 tasks). It compares the performance of the proposed model against previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) results. The table showcases the impact of different pretraining techniques (adding YT-ASL, MT data, Augmented SLT data, and using larger ByT5 models) on the final finetuned model’s performance. The final row demonstrates the impact of multilingual SLT tuning on the model’s performance across multiple sign and spoken languages.

read the caption

Table 5: Finetuning performance (BLEURT↑) on downstream SLT benchmarks. 'H2S/E23': How2Sign/Elementary23. 'SRF/SS': WMT23 DSGS SRF/SS test split. 'Avg': averaged performance over all benchmarks. MT data are added in both translation directions. Previous SOTA: How2Sign [43], Elementary23 [48] and WMT23 SRF [28], WMT23 LIS-CH, LSF-CH, SS [44]. All models are finetuned on each SLT benchmark separately except (9).

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved after finetuning various SLT models on six different downstream benchmarks. It shows the performance improvements gained by incorporating different pretraining techniques (e.g., adding YouTube data, multilingual machine translation data, augmented SLT data) and using larger models. The table also includes a comparison to the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) results, highlighting the substantial improvements achieved by the proposed method. Note that the last row shows the performance when multilingual tuning is applied.

read the caption

Table 5: Finetuning performance (BLEURT↑) on downstream SLT benchmarks. 'H2S/E23': How2Sign/Elementary23. 'SRF/SS': WMT23 DSGS SRF/SS test split. 'Avg': averaged performance over all benchmarks. MT data are added in both translation directions. Previous SOTA: How2Sign [43], Elementary23 [48] and WMT23 SRF [28], WMT23 LIS-CH, LSF-CH, SS [44]. All models are finetuned on each SLT benchmark separately except (9).

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved after fine-tuning various SLT models on six different benchmarks. It shows a comparison of performance improvements obtained by incorporating different pretraining data (YT-ASL, YT-Full, MT-Small, MT-Large, augmented SLT data), model sizes (ByT5 Base, ByT5 XL), and multilingual SLT tuning. The table highlights the significant improvement in performance achieved by the proposed model compared to previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) results.

read the caption

Table 5: Finetuning performance (BLEURT↑) on downstream SLT benchmarks. 'H2S/E23': How2Sign/Elementary23. 'SRF/SS': WMT23 DSGS SRF/SS test split. 'Avg': averaged performance over all benchmarks. MT data are added in both translation directions. Previous SOTA: How2Sign [43], Elementary23 [48] and WMT23 SRF [28], WMT23 LIS-CH, LSF-CH, SS [44]. All models are finetuned on each SLT benchmark separately except (9).

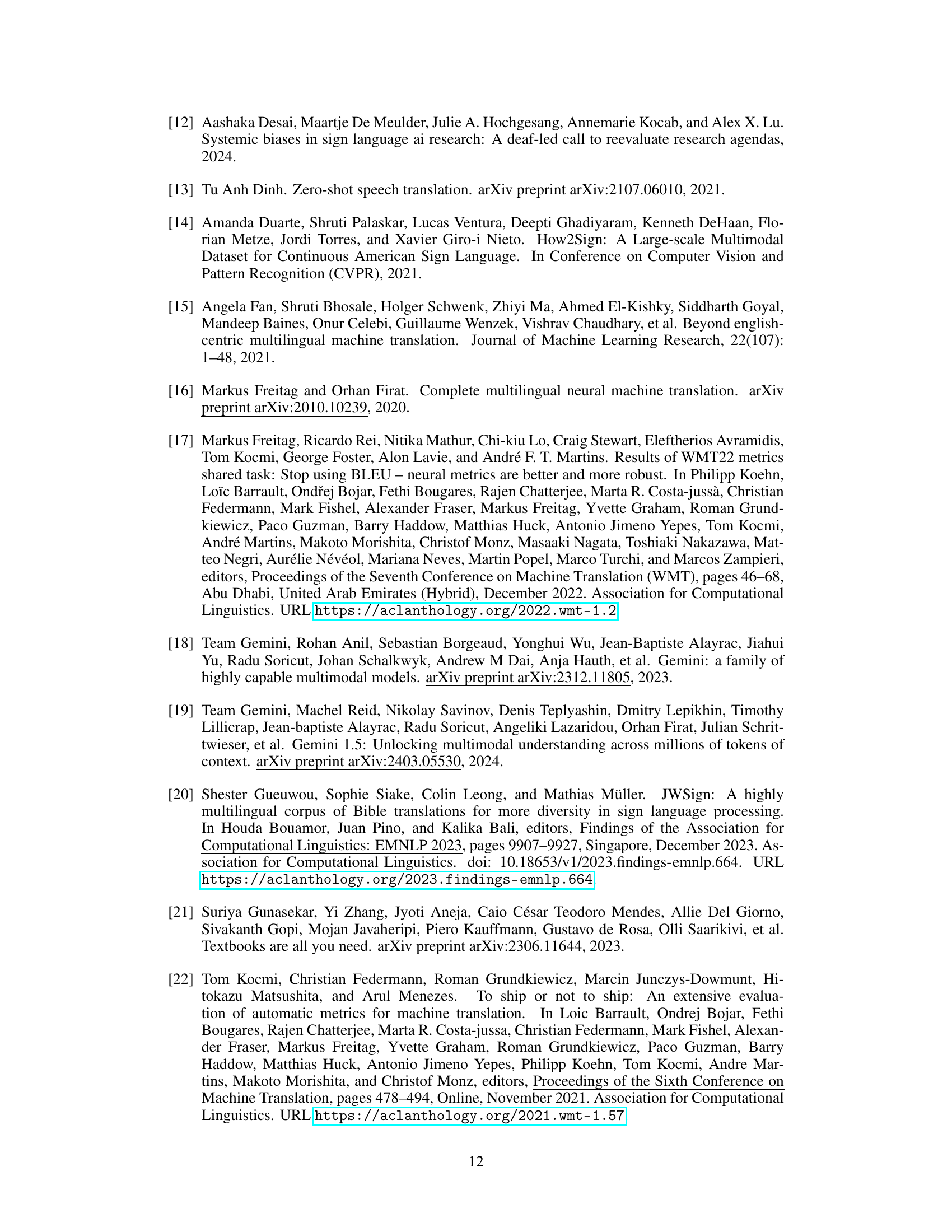

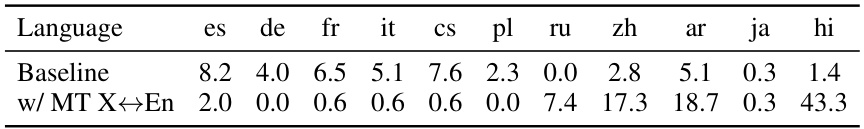

🔼 This table presents the results of the pretraining phase of the Sign Language Translation (SLT) experiments. It shows the BLEU, ChrF, and BLEURT scores for various models across different benchmarks, namely How2Sign (H2S), Elementary23 (E23), and WMT23. The models evaluated include a ByT5 Base model and several variations with added data (YT-ASL, YT-Full, MT-Small), data augmentation (Aug-YT-ASL-Small), and larger model sizes (ByT5 XL). The table allows a comparison of performance across different model configurations and datasets to determine the impact of these factors on SLT pretraining.

read the caption

Table 9: Pretraining performance on downstream SLT benchmarks.

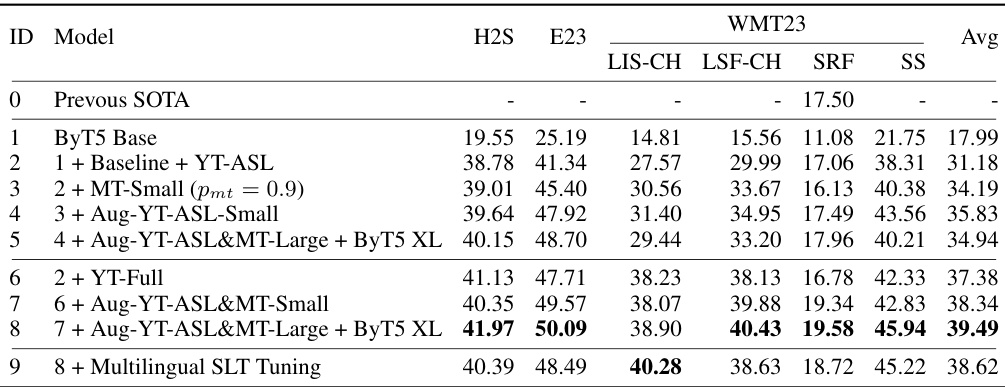

🔼 This table presents the BLEU, chrF, and BLEURT scores achieved by different models on several downstream SLT benchmarks. The models are trained using varying configurations of pretraining data, model sizes, and language scaling techniques. The results show substantial improvements over previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) models, particularly after finetuning. Note that the model achieves new SOTA after multilingual SLT tuning.

read the caption

Table 8: Finetuning performance on downstream SLT benchmarks. 'H2S/E23': How2Sign/Elementary23. 'SRF/SS': WMT23 DSGS SRF/SS test split. 'Avg': averaged performance over all benchmarks. MT data are added in both translation directions. Previous SOTA: How2Sign [43], Elementary23 [48] and WMT23 SRF [28], WMT23 LIS-CH, LSF-CH, SS [44]. Scaling SLT reaches new SOTA across benchmarks. All models are finetuned on each SLT benchmark separately except (9).

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved by different sized T5, mT5, and ByT5 models after pretraining on two different datasets: YT-ASL and YT-Full. The evaluation is performed on the How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 benchmarks, with English as the target language. The best performing model for each family is highlighted.

read the caption

Table 2: Pretraining performance (BLEURT ↑) for different sized (By/m)T5 models when pretrained on YT-ASL and YT-Full. Results are reported on the test set of How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (→En, i.e. English as the target). Best results for each model family are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved by different sized ByT5 and mT5 models after pretraining on two different datasets: YT-ASL and YT-Full. The evaluation is performed on the How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 test sets, with English as the target language. The bold values indicate the best performance within each model family.

read the caption

Table 2: Pretraining performance (BLEURT ↑) for different sized (By/m)T5 models when pretrained on YT-ASL and YT-Full. Results are reported on the test set of How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (→En, i.e. English as the target). Best results for each model family are highlighted in bold.

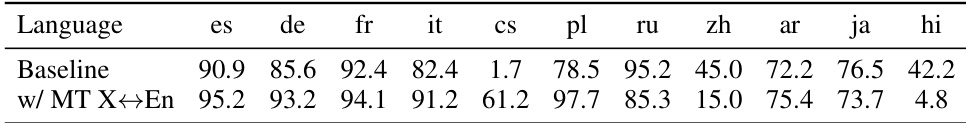

🔼 This table shows the language accuracy and empty rate for zero-shot SLT (Sign Language Translation) with and without multilingual machine translation (MT) data. The results are broken down by target language and show that adding MT data generally improves the translation language accuracy, particularly for languages geographically close to English. However, there are also exceptions, particularly for languages with limited parallel MT data, such as Hindi and Chinese.

read the caption

Table 10: Analysis for zero-shot SLT in Figure 3b. Higher language accuracy indicates less off-target translation, thus better quality; lower empty rate is better.

🔼 This table presents the BLEURT scores achieved by different sized T5, mT5, and ByT5 models after being pretrained on two different datasets, YT-ASL and YT-Full. The evaluation is performed on the How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 benchmarks, with English as the target language. Bold values indicate the best performance for each model family.

read the caption

Table 2: Pretraining performance (BLEURT ↑) for different sized (By/m)T5 models when pretrained on YT-ASL and YT-Full. Results are reported on the test set of How2Sign and FLEURS-ASL#0 (→En, i.e. English as the target). Best results for each model family are highlighted in bold.

Full paper#