TL;DR#

Existing confidence sequences (CSs) for Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) are far from ideal, often lacking tightness and being specific to certain GLM types. This significantly hinders their applications in areas like bandits that require estimating uncertainty from noisy observations. Furthermore, prior optimistic algorithms for GLMs often suffer from poly(S) factors in their regret bounds, which is computationally expensive and less efficient. These issues significantly impede practical applications of GLMs in areas like contextual bandits.

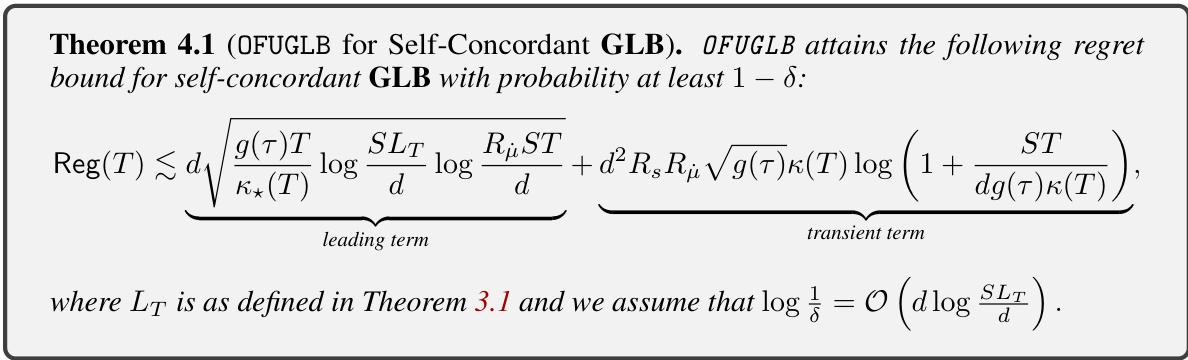

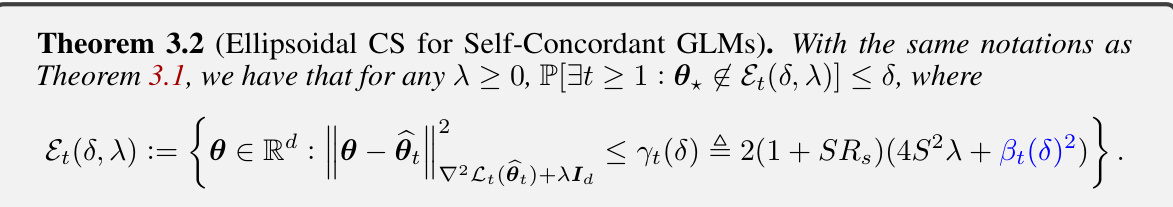

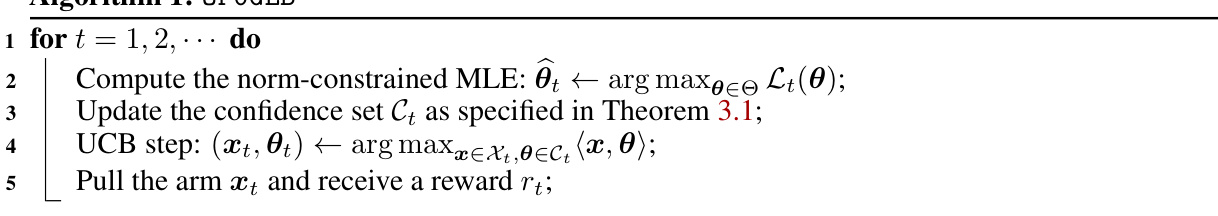

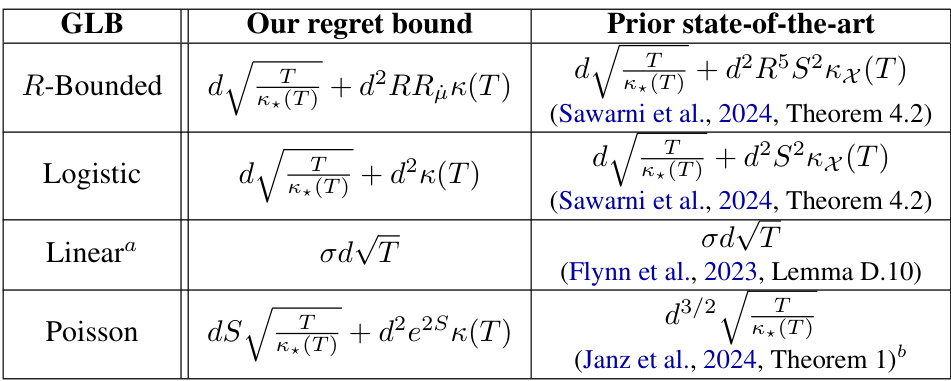

This paper introduces a unified likelihood ratio-based CS construction applicable to any convex GLM. It leverages a time-uniform PAC-Bayesian bound with uniform priors, unlike most prior works. The resulting CS is both numerically tight and on par or better than existing CSs for various GLMs, particularly Bernoulli for which it achieves a poly(S)-free radius. This CS directly leads to a novel optimistic algorithm, OFUGLB, for GLBs. The authors prove that OFUGLB attains state-of-the-art regret bounds for various self-concordant GLBs, and even poly(S)-free for bounded GLBs, such as logistic bandits. This was achieved by introducing a novel proof technique that avoids previously widely-used approaches, which often yield regret bounds with poly(S) factors.

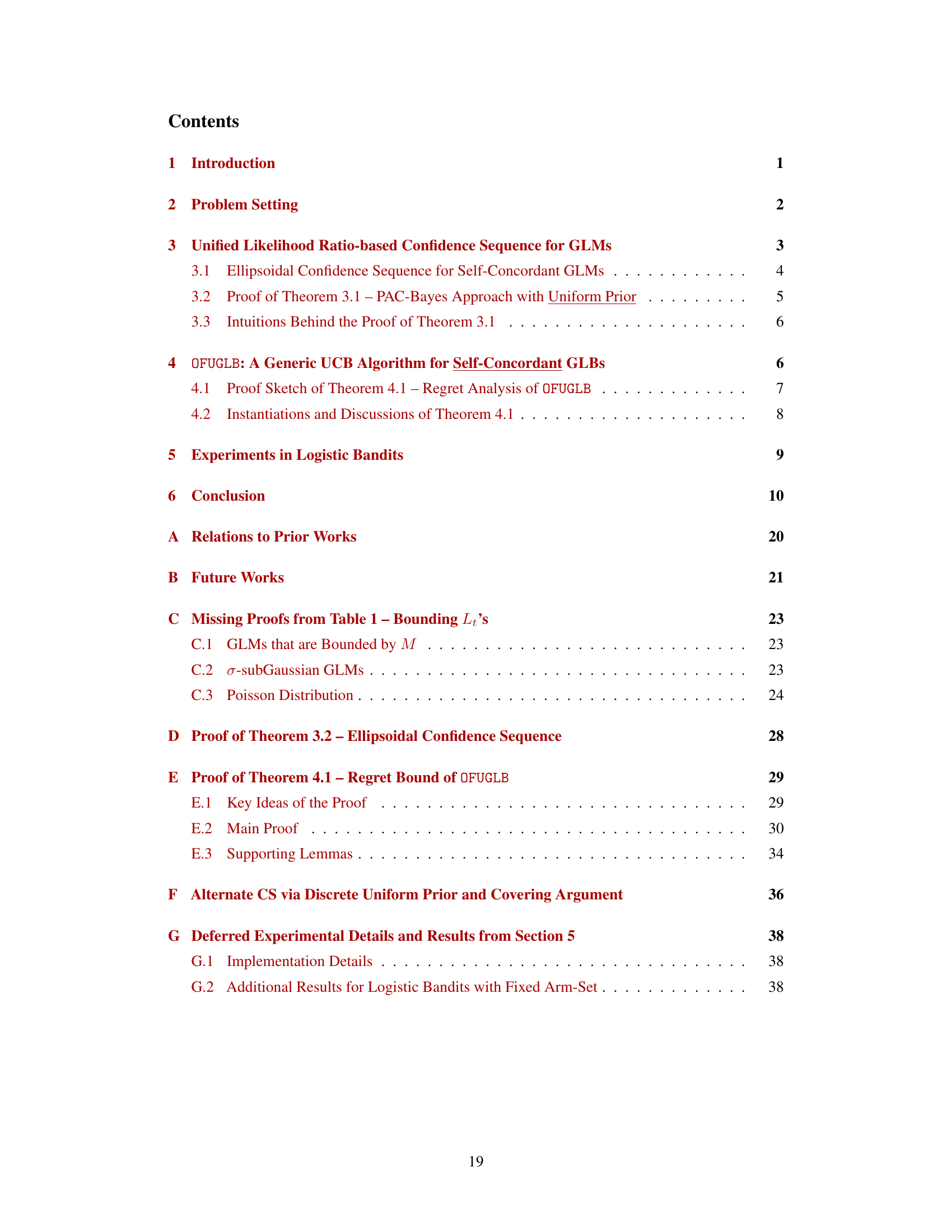

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on generalized linear bandits and confidence sequences. It offers a unified framework, improving upon existing methods and providing a foundation for future research in safe and efficient machine learning algorithms. The poly(S)-free regret bound for logistic bandits is a significant advancement, opening avenues for new algorithms and applications.

Visual Insights#

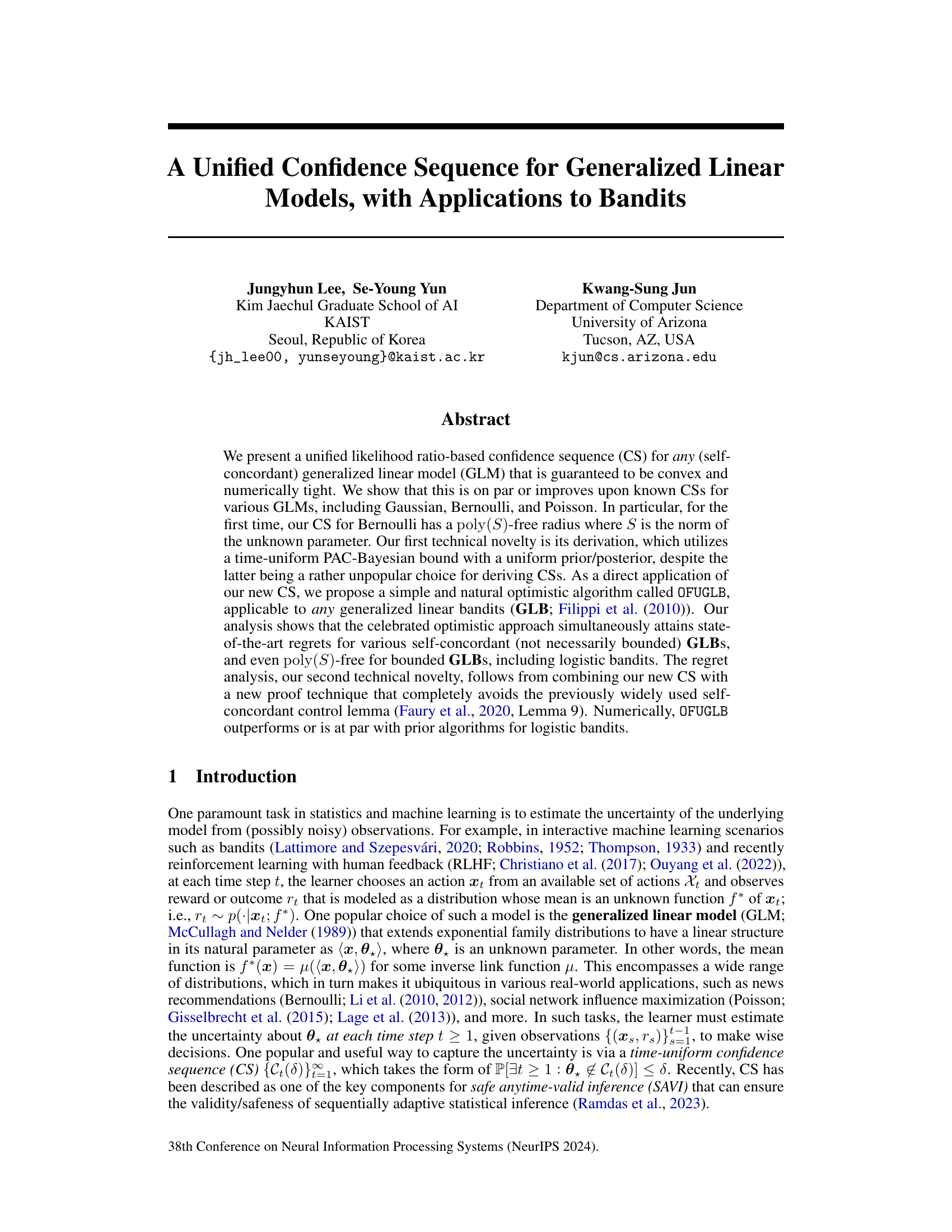

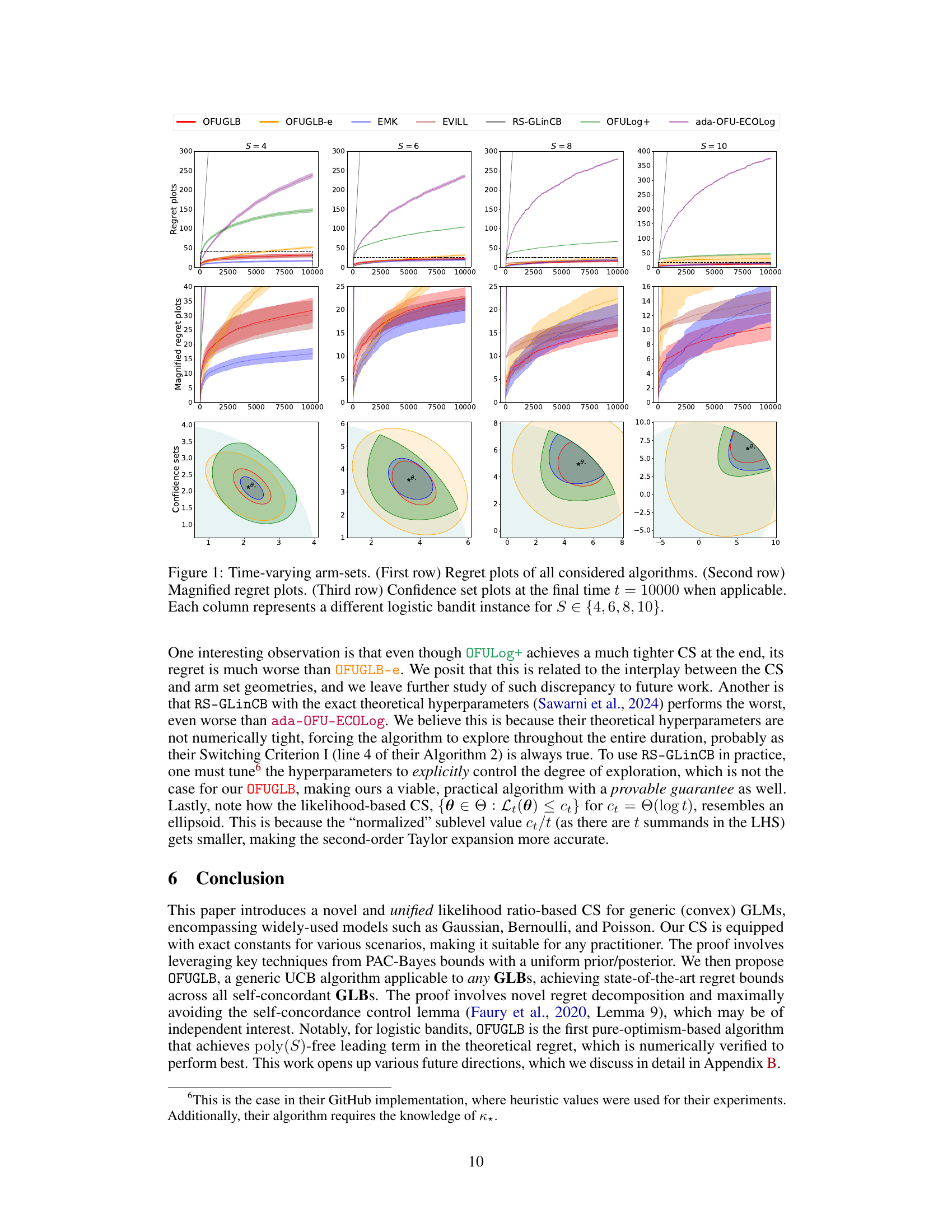

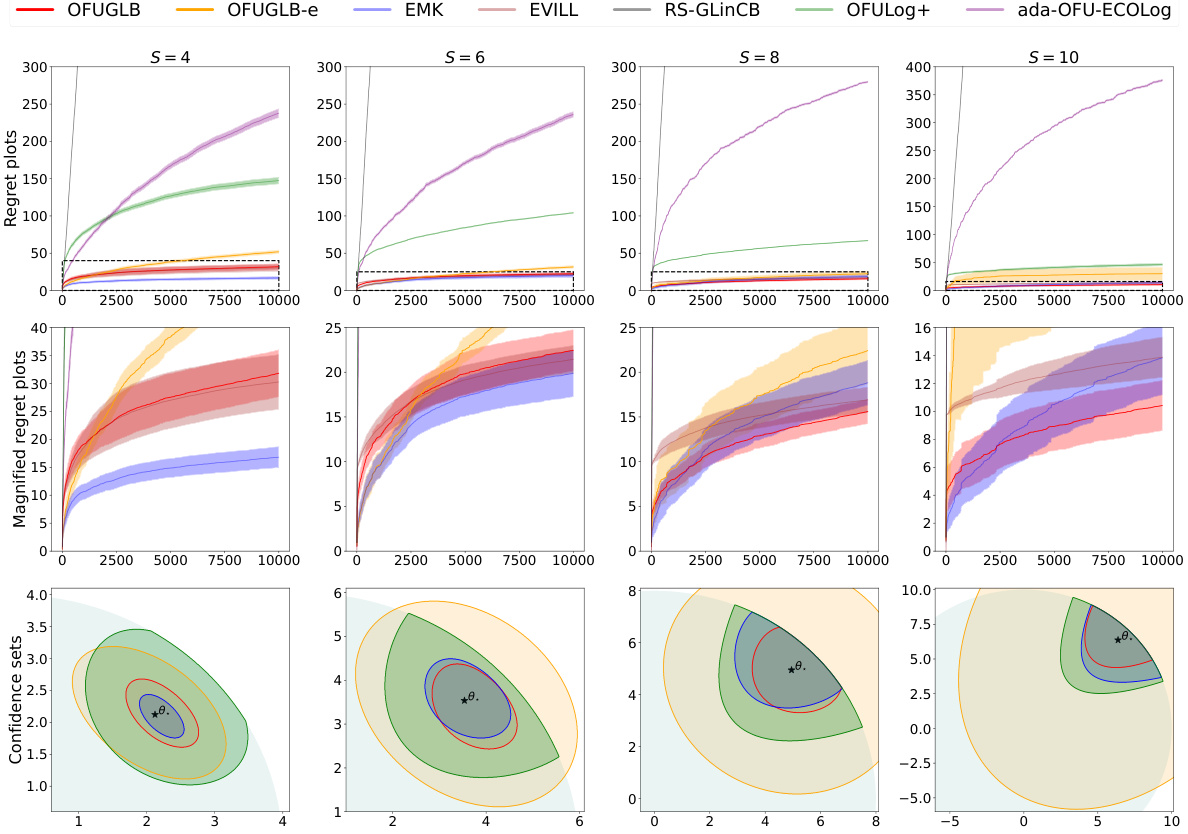

🔼 The figure shows the results of experiments conducted on logistic bandits with time-varying arm-sets. The first row displays the regret of various algorithms across different settings (S values). The second row provides a magnified view of the regret plots for better visualization of differences between algorithms, particularly during the initial phases. The third row illustrates the confidence sets at the final timestep (t=10000). Each column corresponds to a unique logistic bandit experiment with a different value for the parameter S.

read the caption

Figure 1: Time-varying arm-sets. (First row) Regret plots of all considered algorithms. (Second row) Magnified regret plots. (Third row) Confidence set plots at the final time t = 10000 when applicable. Each column represents a different logistic bandit instance for S ∈ {4, 6, 8, 10}.

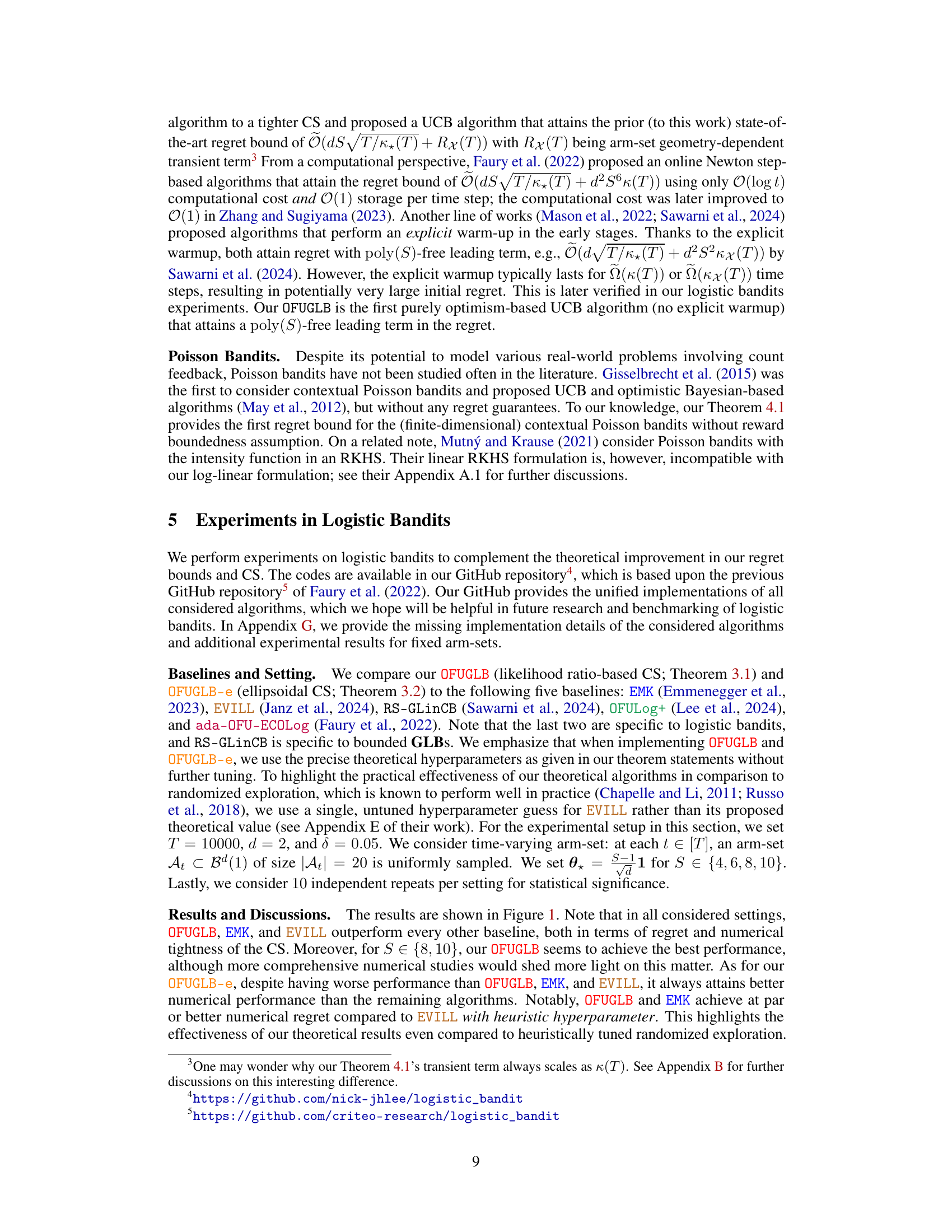

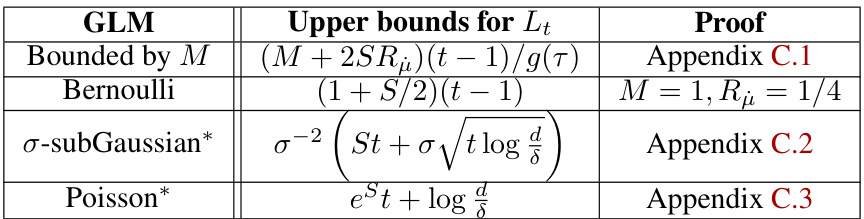

🔼 This table presents upper bounds for Lt for various GLMs (Generalized Linear Models). Lt is a term in the calculation of a likelihood ratio-based confidence sequence. The table shows bounds for GLMs that are bounded by M, Bernoulli, σ-subGaussian, and Poisson distributions. The table also provides the location in the paper where the proof for each bound can be found.

read the caption

Table 1: Instantiations of Lt's for various GLMs. “Bounded by M

In-depth insights#

Unified Confidence#

The concept of “Unified Confidence” in the context of a research paper likely refers to a method for constructing confidence intervals or regions that applies broadly to various statistical models. A unified approach would aim to overcome limitations of existing methods that are often model-specific, computationally expensive, or lack theoretical guarantees. The core of a unified confidence framework would probably be a general theoretical result that provides a principled way to estimate uncertainty regardless of the underlying model’s distributional assumptions. This would involve carefully analyzing the properties of the models to identify shared characteristics and leveraging these to produce a single, universally applicable method. A key advantage would be improved efficiency and broader applicability, allowing researchers to estimate uncertainty across a wider range of models and settings with a consistent and reliable technique. Robustness to violations of model assumptions would also be a significant goal, increasing the practical usefulness of the method and making it more relevant to real-world applications. The resulting unified confidence method would likely represent a significant advancement in statistical inference.

GLM Bandit Regret#

Generalized Linear Model (GLM) bandits are a powerful framework for sequential decision-making under uncertainty, extending the classic multi-armed bandit problem to scenarios with more complex reward distributions. GLM bandit regret quantifies the performance of a learning algorithm in such a setting, measuring the cumulative difference between the rewards obtained and the rewards that could have been obtained with perfect knowledge of the optimal action for each context. Analyzing GLM bandit regret involves understanding the trade-off between exploration (learning about the reward distributions) and exploitation (choosing the seemingly best action given current knowledge). Key factors influencing regret include the dimensionality of the problem, the complexity of the GLM, and the algorithm’s ability to efficiently balance exploration and exploitation. Optimistic algorithms, which maintain confidence intervals around the estimated parameters and select actions that maximize their upper confidence bounds, are commonly employed. However, achieving low regret often requires sophisticated analysis techniques to address the inherent challenges of non-linearity and uncertainty within the GLM framework. Research in this area focuses on developing algorithms that have provable regret bounds and adapting them to various GLM settings such as logistic regression, Poisson distributions, or other exponential families. The design and analysis of algorithms with low regret for GLM bandits is an active area of research, particularly in settings with high dimensionality, limited data, and complex reward structures.

Optimistic Algorithm#

Optimistic algorithms are a class of online learning algorithms that leverage uncertainty estimates to make decisions. They work by maintaining confidence intervals around model parameters and selecting actions that are optimistic, assuming the best-case scenario within these bounds. This approach balances exploration and exploitation by allowing for potentially suboptimal actions early on to reduce uncertainty and improve future performance. The key challenge in designing optimistic algorithms lies in balancing optimism with the need for accurate uncertainty quantification, which is problem-specific. For example, in bandit settings, choosing the action with the highest upper confidence bound directly impacts the algorithm’s regret (the difference between the performance of the algorithm and an optimal strategy). Tight confidence bounds and computationally efficient methods for updating them are crucial for developing efficient and effective optimistic algorithms. Further research may focus on extending optimistic algorithms to handle various settings, such as non-convex objectives, partial observability, and complex uncertainty structures. The development of novel uncertainty quantification techniques and efficient optimization strategies is vital to further improving the efficacy and scope of optimistic algorithms.

PAC-Bayes Approach#

The PAC-Bayes approach, a cornerstone of the paper’s theoretical foundation, offers a powerful framework for deriving tight, data-dependent confidence sequences. By leveraging a time-uniform PAC-Bayesian bound with a uniform prior/posterior, the authors circumvent the limitations of traditional methods. This unconventional choice simplifies the analysis, yielding a poly(S)-free radius for Bernoulli GLMs. The analysis elegantly combines a martingale argument with Donsker-Varadhan’s variational representation of KL divergence and Ville’s inequality, establishing a high-probability bound on the likelihood ratio. The result is a unified and numerically efficient confidence sequence suitable for a wide array of GLMs, surpassing prior works in tightness and applicability. The choice of uniform prior/posterior, while unconventional in the context of confidence sequences, is inspired by portfolio theory and fast rates in statistical learning, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of the approach and its potential for broader impact in statistical inference. This rigorous methodology underpins the paper’s subsequent results on optimistic algorithms for generalized linear bandits, demonstrating its profound effectiveness beyond the scope of confidence sequence construction alone.

Future Research#

The paper’s ‘Future Research’ section would benefit from exploring several avenues. Extending the confidence sequence (CS) framework to reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces (RKHS) would significantly broaden its applicability to complex, high-dimensional problems. Investigating the optimality of the CS radius is crucial to understand its theoretical limitations and potential improvements. Addressing the open question of a regret lower bound for generalized linear bandits (GLBs) will solidify the understanding of the algorithm’s performance limits. Finally, a deeper investigation into arm-set geometry-dependent regret analysis would enhance the algorithm’s adaptability and provide a more nuanced understanding of its performance across diverse problem scenarios. This would involve delving into the interplay between the CS and the specific characteristics of the arm sets, ultimately leading to more refined and accurate regret bounds.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments on logistic bandits with time-varying arm-sets. The first row displays the regret (cumulative difference between the optimal and chosen actions) of several algorithms across different problem difficulties (S). The second row provides a magnified view of the regret for a clearer comparison during the initial stages. The third row shows the confidence sets for the parameter estimates at the end of the experiment (t=10000), which represent the uncertainty around the estimated parameter.

read the caption

Figure 1: Time-varying arm-sets. (First row) Regret plots of all considered algorithms. (Second row) Magnified regret plots. (Third row) Confidence set plots at the final time t = 10000 when applicable. Each column represents a different logistic bandit instance for S ∈ {4, 6, 8, 10}.

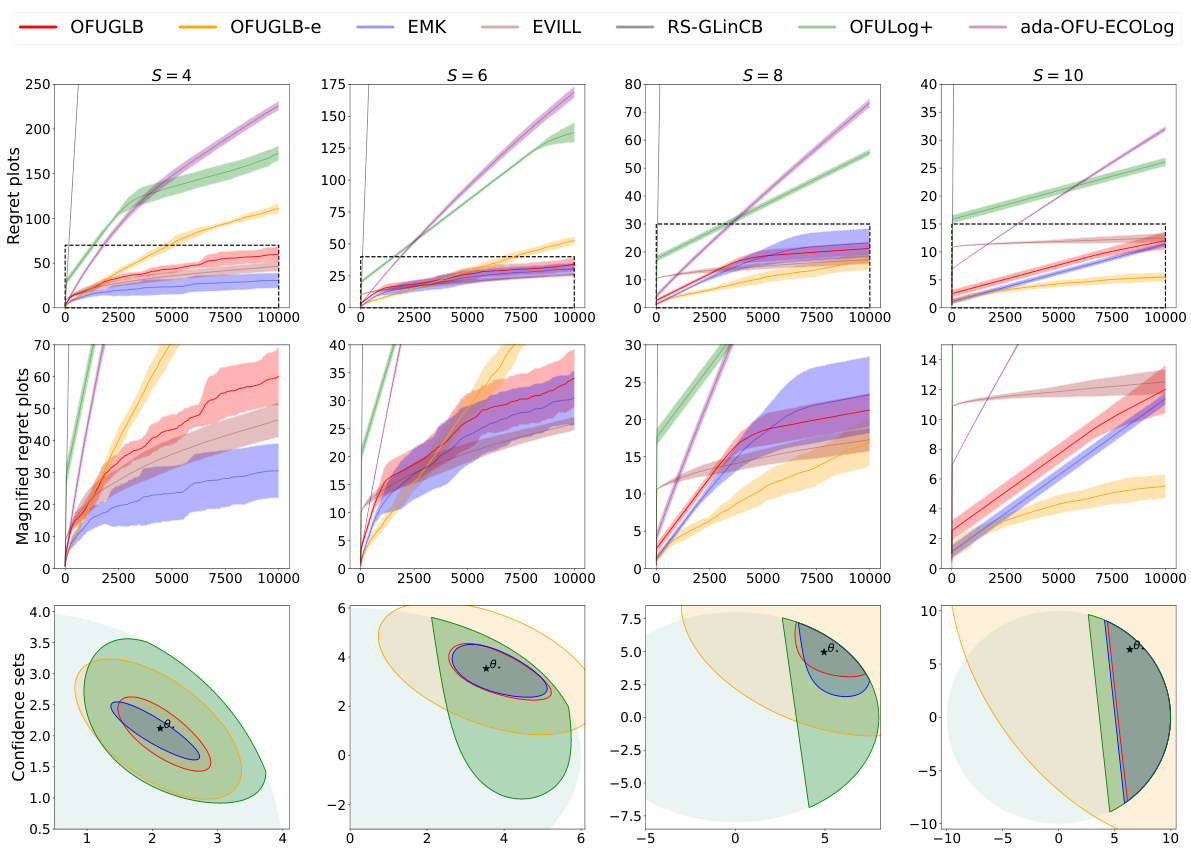

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments on logistic bandits with time-varying arm-sets. The top row shows the regret (cumulative difference between the optimal reward and the algorithm’s reward) for each algorithm across different values of S (a parameter related to the problem’s complexity). The middle row provides a magnified view of the regret, focusing on the early stages of the learning process. The bottom row visualizes the confidence sets (regions containing the true parameter with high probability) generated by the algorithms at the end of the learning process (time step 10000). Each column represents a separate experimental instance with a different problem setting.

read the caption

Figure 1: Time-varying arm-sets. (First row) Regret plots of all considered algorithms. (Second row) Magnified regret plots. (Third row) Confidence set plots at the final time t = 10000 when applicable. Each column represents a different logistic bandit instance for S ∈ {4, 6, 8, 10}.

More on tables

🔼 This table shows upper bounds for the Lipschitz constant Lt for different generalized linear models (GLMs). The GLMs considered are Bernoulli, σ-subGaussian, and Poisson. For each GLM, the table provides an upper bound for Lt, taking into account whether the GLM is bounded by a constant M or not. The presence of a bound M affects the form of the upper bound. The final column indicates which appendix contains the proof for that particular upper bound.

read the caption

Table 1: Instantiations of Lt's for various GLMs. “Bounded by M

🔼 This table presents upper bounds for Lt (the Lipschitz constant of the negative log-likelihood function) for various generalized linear models (GLMs), including Bernoulli, Gaussian, and Poisson. The bounds are categorized by whether or not the GLM is bounded by a constant M. It includes the relevant proofs and relevant parameters in calculating the bounds. The table provides closed-form upper bounds (up to absolute constants) that practitioners can directly implement without additional difficulty.

read the caption

Table 1: Instantiations of Lt's for various GLMs. “Bounded by M

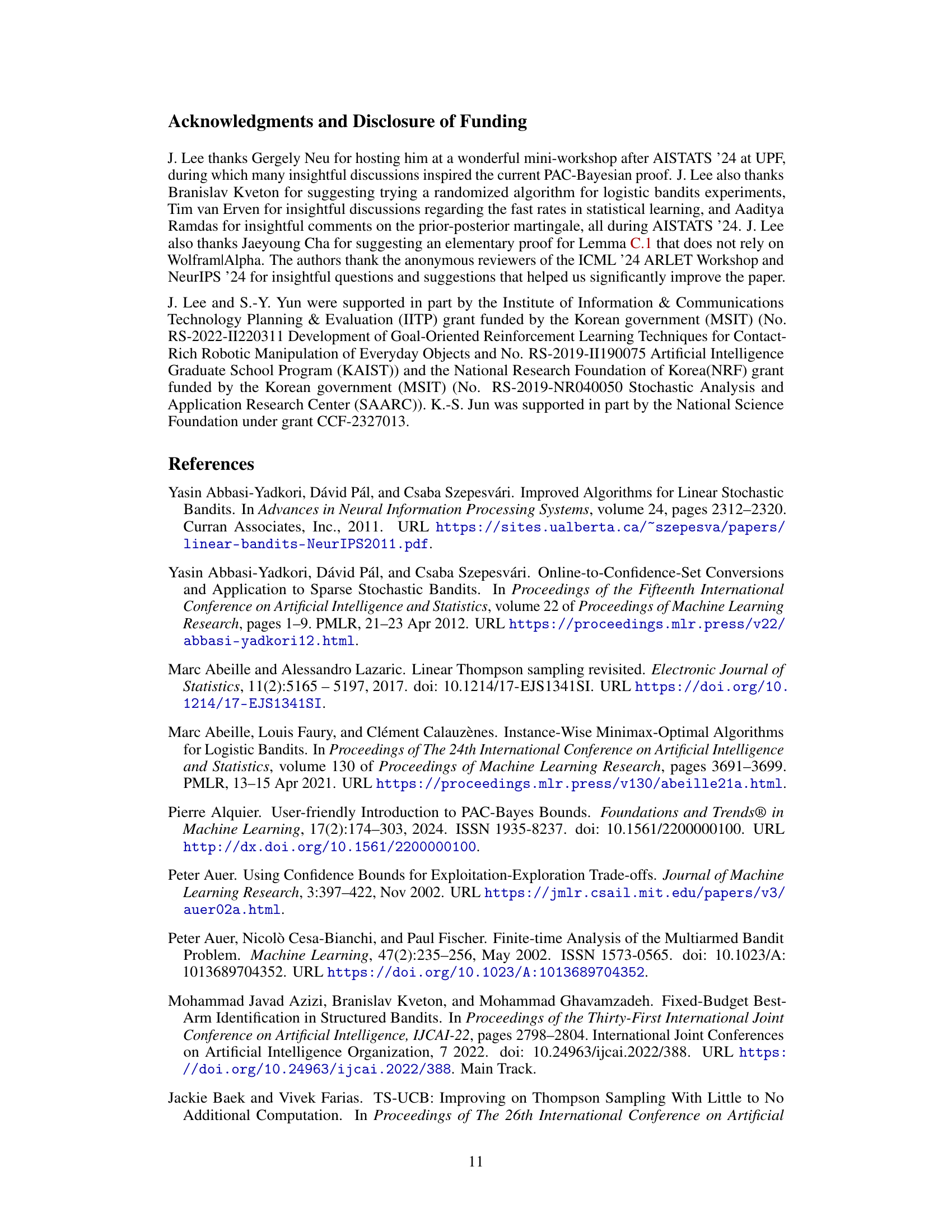

🔼 This table presents the regret bounds achieved by the Optimism in the Face of Uncertainty for Generalized Linear Bandits (OFUGLB) algorithm for various self-concordant generalized linear bandits (GLBs). It compares OFUGLB’s regret bounds to the state-of-the-art results from prior research. The table includes bounds for R-Bounded, Logistic, Linear, and Poisson GLBs. Logarithmic factors are omitted for clarity. The notation kx(T) represents the maximum slope of the inverse link function μ. The ‘R-Bounded’ case signifies that the reward is almost surely bounded by R.

read the caption

Table 2: Regret bounds of OFUGLB for various self-concordant GLBs. Logarithmic factors are omitted to avoid a cognitive overload. Let kx(T) := max∈υ1ε μ((2,0)) (2.0)) and g(t) = O(1). Here, “R-Bounded

Full paper#