TL;DR#

Safe reinforcement learning (RL) struggles with incorporating complex, real-world constraints, especially when expressed in natural language. Existing methods often require manual design of cost functions for each constraint, limiting flexibility and scalability. This problem is exacerbated by sparse cost issues in trajectory-level constraints, where penalties are only applied at the end of a sequence of actions, making learning difficult. This limits the applicability of safe RL to more complex and dynamic real-world problems.

The paper introduces Trajectory-level Textual Constraints Translator (TTCT), which addresses these limitations. TTCT uses a dual role for text, employing it as both a constraint and a training signal. This is achieved through a contrastive learning approach that aligns trajectory embeddings with textual constraint representations. A cost assignment component further refines this, providing more granular feedback on individual actions, resolving the sparse cost issue. Experiments show TTCT achieves lower violation rates and displays zero-shot transfer capabilities across different scenarios, demonstrating robustness and potential for real-world deployment.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical challenge in safe reinforcement learning: handling complex constraints expressed in natural language. It introduces a novel approach that is more flexible and generalizable than existing methods, opening new avenues for research in safe AI. The zero-shot transfer capability is a particularly significant contribution, paving the way for broader application of safe RL in real-world scenarios.

Visual Insights#

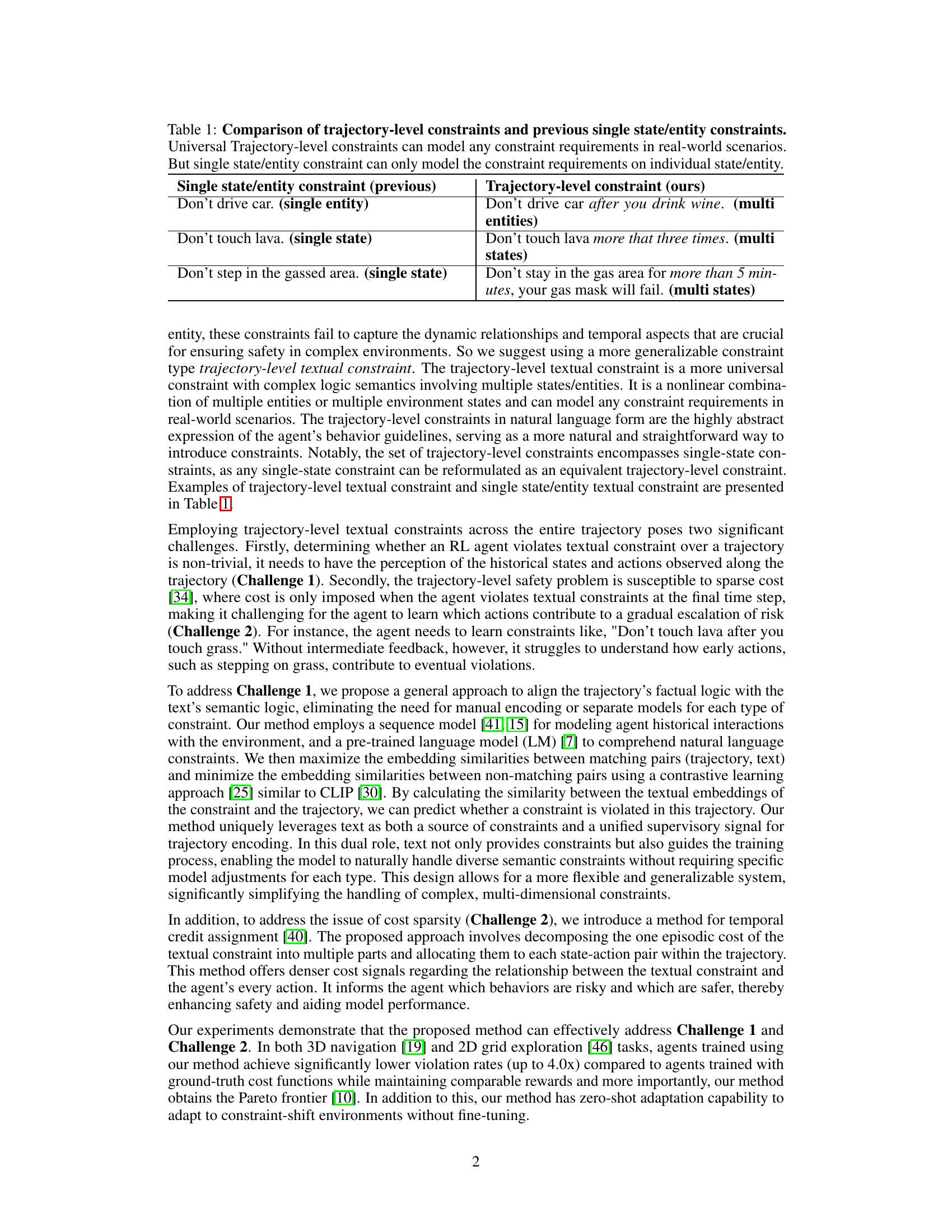

🔼 This figure provides a high-level overview of the Trajectory-level Textual Constraints Translator (TTCT) framework. It shows the two main components: the text-trajectory alignment component and the cost assignment component. The text-trajectory alignment component uses a multimodal architecture to connect trajectories and text, predicting whether a trajectory violates a given constraint. The cost assignment component assigns a cost to each state-action pair based on its impact on constraint satisfaction. During RL policy training, these components work together; the alignment component predicts violations, and the assignment component provides a cost signal for training the policy.

read the caption

Figure 1: TTCT overview. TTCT consists of two training components: (1) the text-trajectory alignment component connects trajectory to text with multimodal architecture, and (2) the cost assignment component assigns a cost value to each state-action based on its impact on satisfying the constraint. When training RL policy, the text-trajectory alignment component is used to predict whether a trajectory violates a given constraint and the cost assignment component is used to assign non-violation cost.

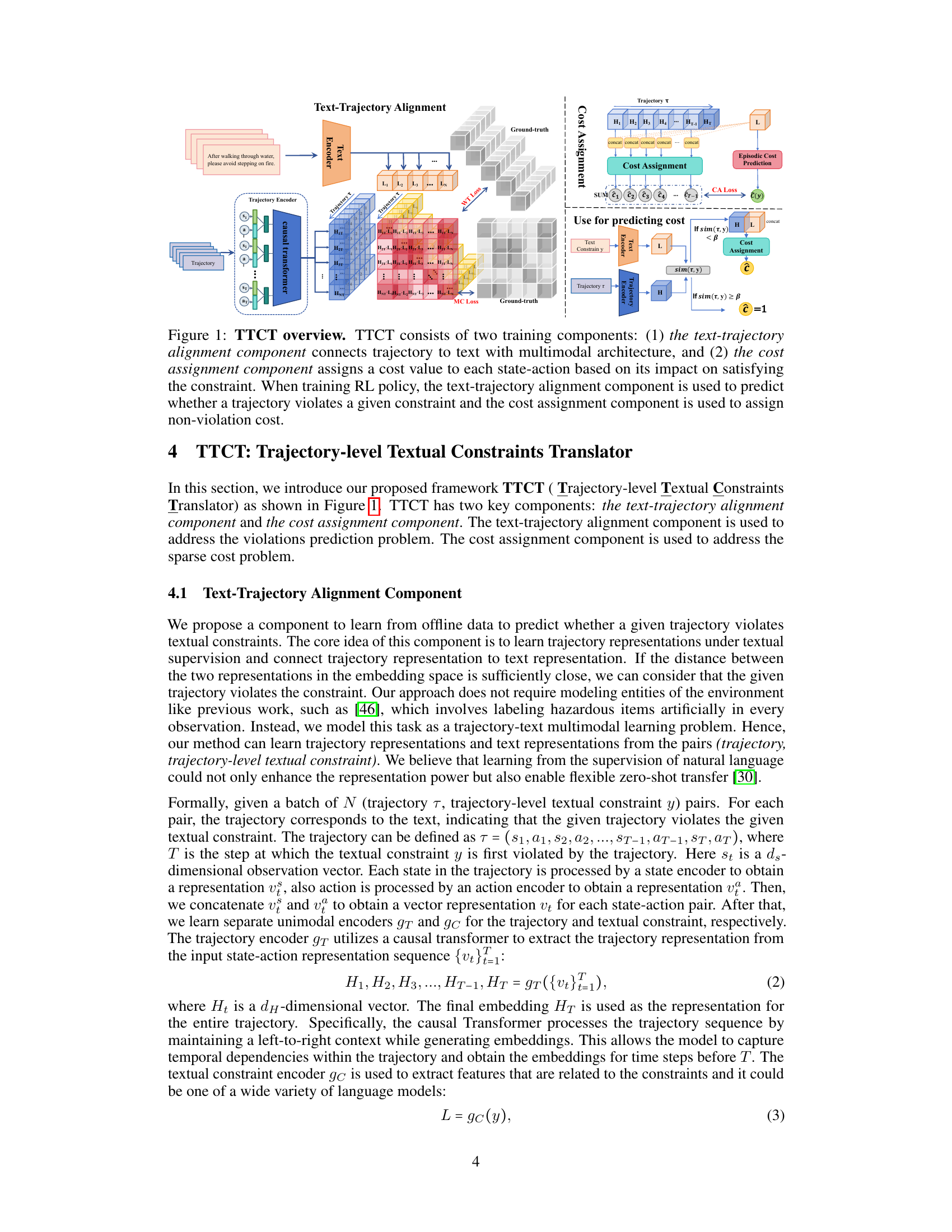

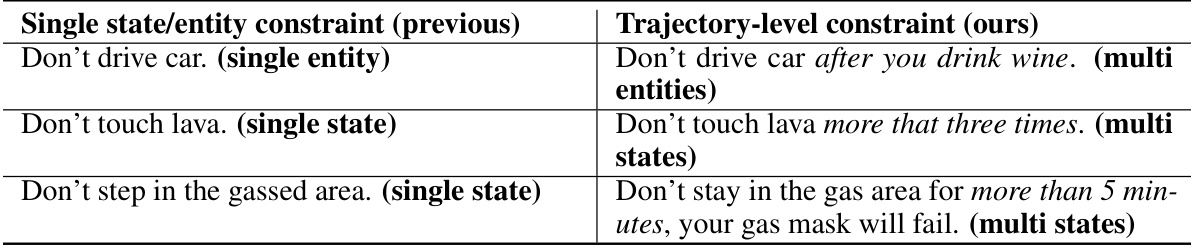

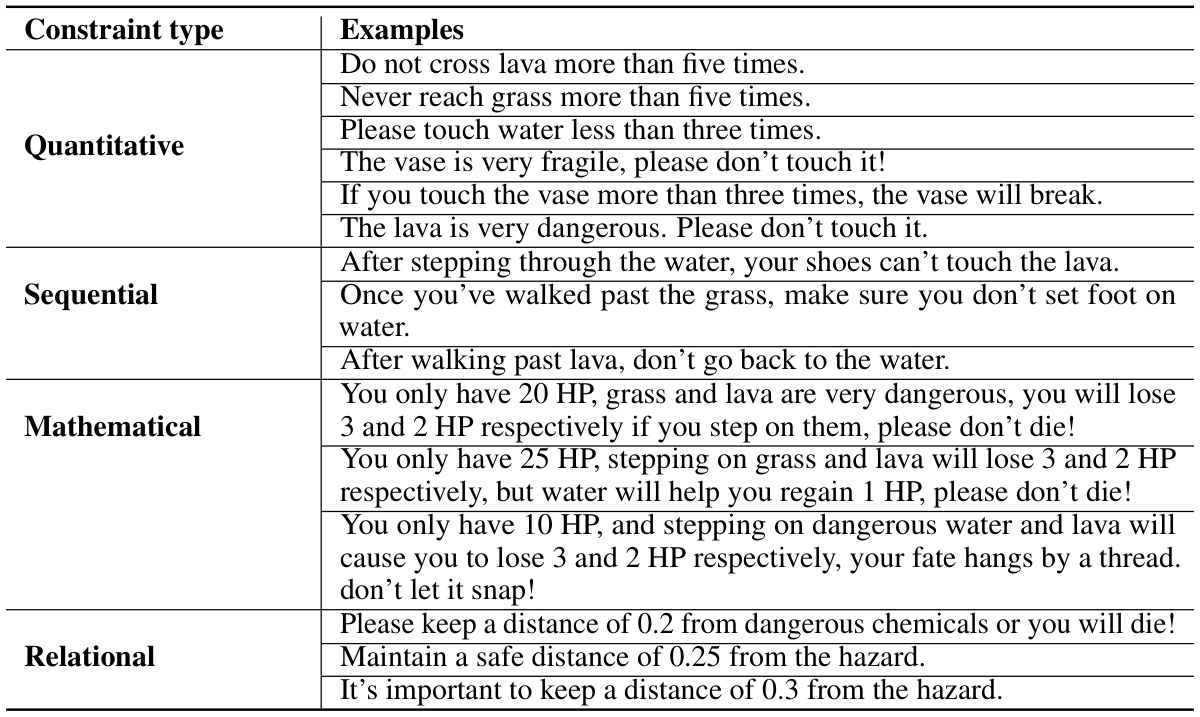

🔼 This table compares trajectory-level constraints with the previously used single state/entity constraints. It highlights the difference in their capabilities to model complex real-world scenarios. Trajectory-level constraints, as proposed in this paper, can represent more complex and dynamic relationships between multiple entities and states over time, unlike single state/entity constraints which focus solely on individual states or entities. Examples are given to illustrate the difference.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of trajectory-level constraints and previous single state/entity constraints.

In-depth insights#

Text to Trajectory#

The concept of “Text to Trajectory” in the context of a research paper likely explores the translation of natural language instructions into actionable robot trajectories. This involves bridging the gap between high-level human commands (text) and low-level control signals required for robot navigation and manipulation. A core challenge lies in interpreting the nuanced semantics of natural language, which can be ambiguous and context-dependent. The paper likely investigates methods to parse textual commands, extract relevant information regarding the environment and goal, and translate this understanding into a sequence of actions that form a safe and efficient trajectory. Key components could include natural language processing (NLP) techniques to understand the text, environment modeling to interpret spatial relationships mentioned in the text, and trajectory planning algorithms that generate feasible and safe plans that satisfy the given constraints. The effectiveness of the proposed approach would likely be evaluated through simulations in various environments, comparing its performance against other trajectory generation methods in terms of accuracy, safety, and efficiency. The research might also delve into handling ambiguous instructions, incorporating uncertainty, and adapting to dynamic environments.

Constraint Decomp#

The heading ‘Constraint Decomp,’ likely refers to a method for decomposing complex constraints into simpler, manageable parts within a Reinforcement Learning (RL) framework. This is crucial because real-world problems rarely involve single, easily-defined constraints. A decomposition approach could address this by breaking down a high-level constraint, potentially expressed in natural language, into a set of lower-level constraints that are easier for an RL agent to understand and learn. This decomposition might involve temporal or logical subdivisions of the original constraint, allowing the agent to receive more frequent feedback during training. Effective decomposition is essential for achieving safety and efficiency. By tackling simpler, more frequent constraints, the agent avoids the sparsity problem often associated with complex, high-level constraints, improving learning and reducing the risk of catastrophic violations. The method likely employs some form of hierarchy or modularity, potentially using intermediate reward signals or cost functions based on the decomposed constraints. The success of such an approach hinges on creating a meaningful decomposition that captures the essence of the original constraint while remaining computationally feasible and easily interpretable by the learning algorithm. Different decomposition strategies might exist, each with its own set of advantages and disadvantages, for instance, some methods could focus on temporal decomposition, breaking down constraints over time, while others might use logical decomposition separating the various components involved.

TTCT Framework#

The TTCT (Trajectory-level Textual Constraints Translator) framework is a novel approach to safe reinforcement learning (RL) that addresses the limitations of existing methods. It leverages natural language descriptions of constraints, not only as input but also as a training signal. This dual role of text is key to TTCT’s ability to handle complex, dynamic constraints. The framework is composed of two main components: a text-trajectory alignment component and a cost assignment component. The alignment component uses a contrastive learning approach to learn a joint embedding space for trajectories and textual constraints, enabling it to effectively assess whether a trajectory violates given constraints. Critically, the cost assignment component tackles the sparsity problem often present in trajectory-level constraints by decomposing the episodic cost into per-state-action costs, providing a denser training signal. This innovative approach allows for more effective learning and zero-shot transfer to unseen constraint scenarios. Overall, the TTCT framework demonstrates a significant advance in safe RL by enabling the use of flexible and expressive natural language constraints, ultimately leading to safer and more robust RL agents.

Zero-Shot Transfer#

Zero-shot transfer, in the context of this research paper, explores the model’s ability to generalize to unseen environments or tasks without any fine-tuning. The core idea is to leverage a pre-trained model to quickly adapt to new constraints, essentially enabling the model to handle scenarios it wasn’t explicitly trained for. Success in zero-shot transfer is critical for real-world applications, where adapting to new constraints or situations rapidly is essential. This paper demonstrates that their proposed method exhibits this crucial ability, adapting effectively without additional training. The success of zero-shot transfer is strongly tied to the quality of the model’s representation learning. By effectively capturing meaningful relationships between text descriptions and trajectory features, the model can accurately determine whether a constraint is violated and assign costs accordingly, even for novel tasks. This ability showcases the model’s capacity to extrapolate beyond its training data, which highlights the system’s efficiency and resilience. However, the limitations of zero-shot transfer need to be further studied. While the results are promising, the challenges of handling complex, highly dynamic real-world scenarios remain, where perfect generalization might still be elusive.

Future of Safe RL#

The future of safe reinforcement learning (RL) hinges on addressing its current limitations to enable reliable deployment in real-world applications. Bridging the gap between theoretical guarantees and practical robustness is paramount. This involves developing more sophisticated methods for specifying and enforcing constraints, moving beyond simple mathematical formulations to incorporate natural language descriptions and complex logical relationships. Further research into robust reward shaping and credit assignment techniques is crucial for addressing sparse and delayed rewards, especially in complex scenarios. Improved safety verification and validation methods are needed to increase trust and confidence in learned policies. Finally, the development of generalizable and transferable safe RL algorithms that can adapt to diverse environments and unforeseen situations is essential to translate research advancements into practical, real-world impact. Focus should shift to incorporating human expertise and preferences into the learning process through techniques like human-in-the-loop RL, preference learning, and inverse reinforcement learning. This will not only improve the safety and reliability of RL systems but also ensure alignment with human values and goals.

More visual insights#

More on figures

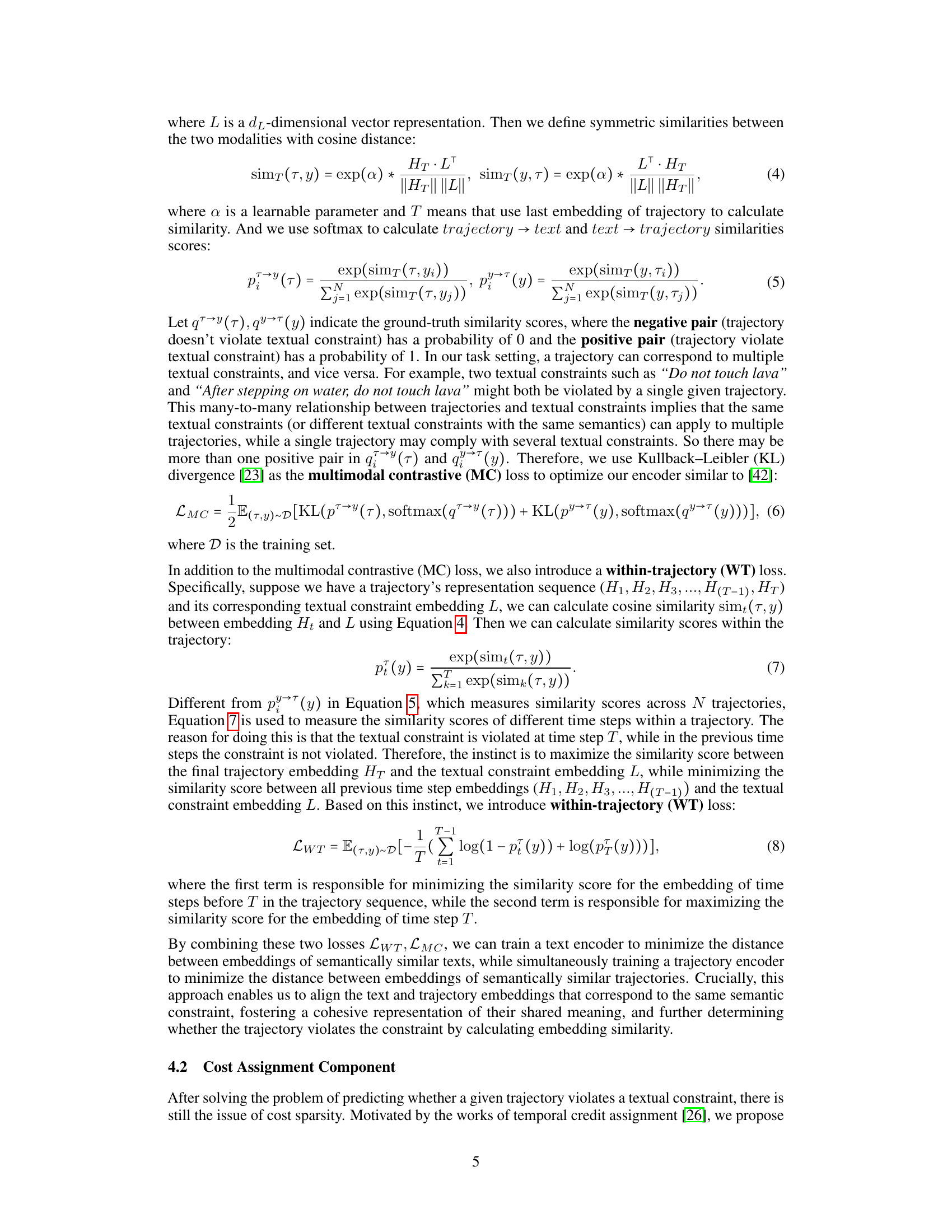

🔼 This figure shows three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: Hazard-World-Grid, SafetyGoal, and LavaWall. Each environment presents a unique challenge for the RL agent, requiring it to navigate while adhering to specified textual constraints. The image provides a visual representation of the task layouts, highlighting obstacles (lava, water, hazards) and the agent’s goal.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) One layout in Hazard-World-Grid [46], where orange tiles are lava, blue tiles are water and green tiles are grass. Agents need to collect reward objects in the grid while avoiding violating our designed textual constraint for the entire episode. (b) Robot navigation task Safety Goal that is built in Safety-Gymnasium [19], where there are multiple types of objects in the environment. Agents need to reach the goal while avoiding violating our designed textual constraint for the entire episode. (c) LavaWall [5], a task has the same goal but different hazard objects compared to Hazard-World-Grid.

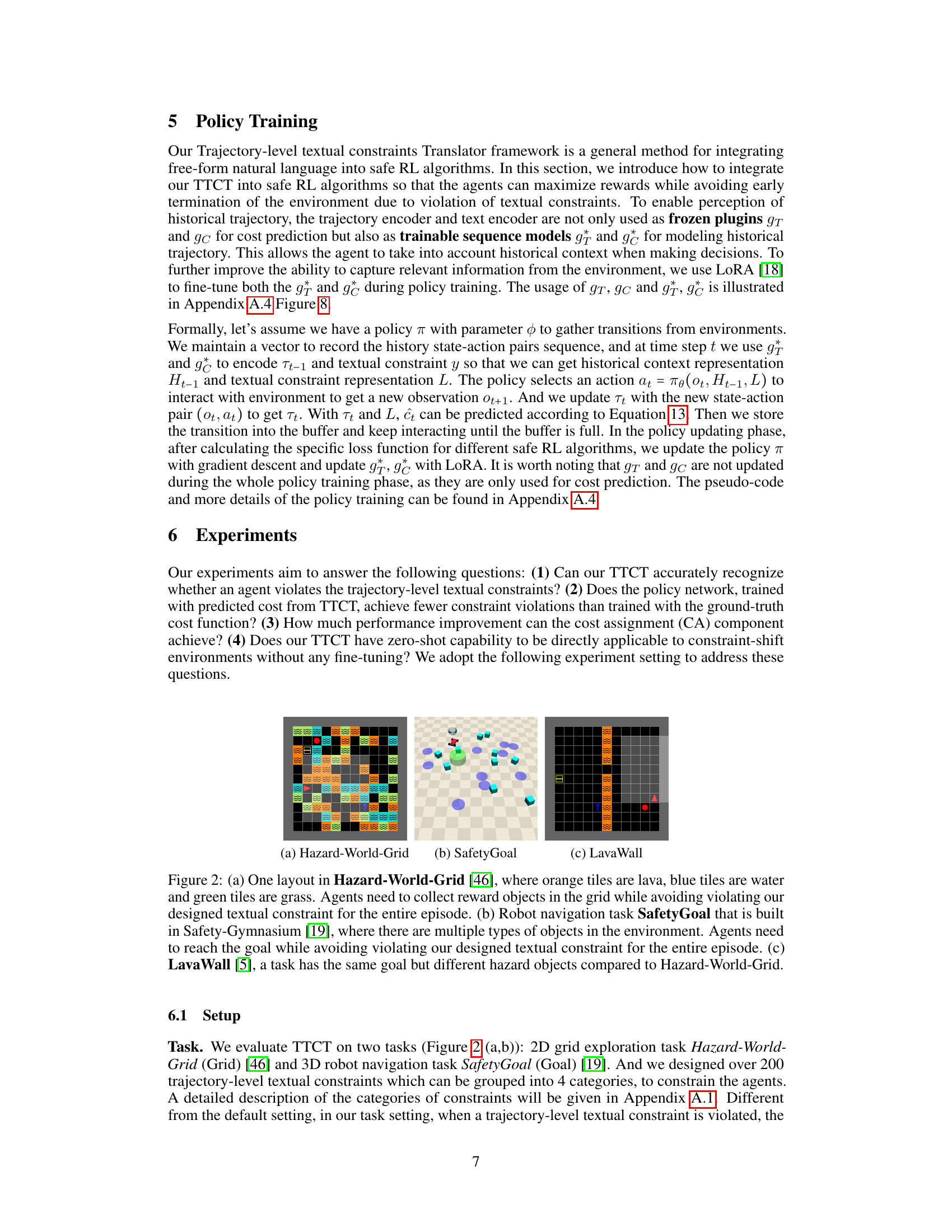

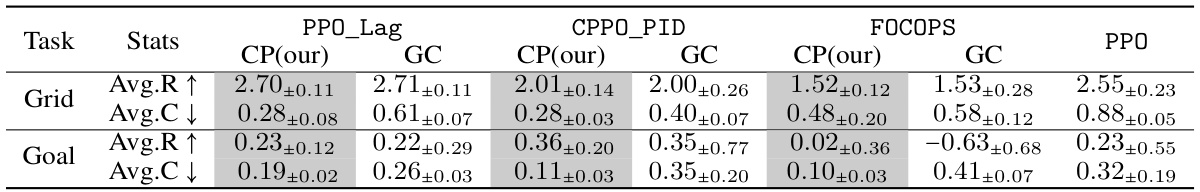

🔼 This figure presents the comparison of the proposed TTCT method with other baselines on two tasks: Hazard-World-Grid and SafetyGoal. The performance metrics shown are average reward and average cost. The blue bars represent the performance of TTCT using the predicted cost, the orange bars show the performance using ground truth cost, and the black dashed lines show the performance of the standard PPO algorithm (without constraints). The results demonstrate that TTCT achieves comparable or better performance compared to baselines on both tasks while maintaining fewer constraint violations.

read the caption

Figure 3: Evaluation results of our proposed method TTCT. The blue bars are our proposed cost prediction (CP) mode performance and the orange bars are the ground-truth cost (GC) mode performance. The black dashed lines are PPO performance. (a) Results on Hazard-World-Grid task. (b) Results on SafetyGoal task.

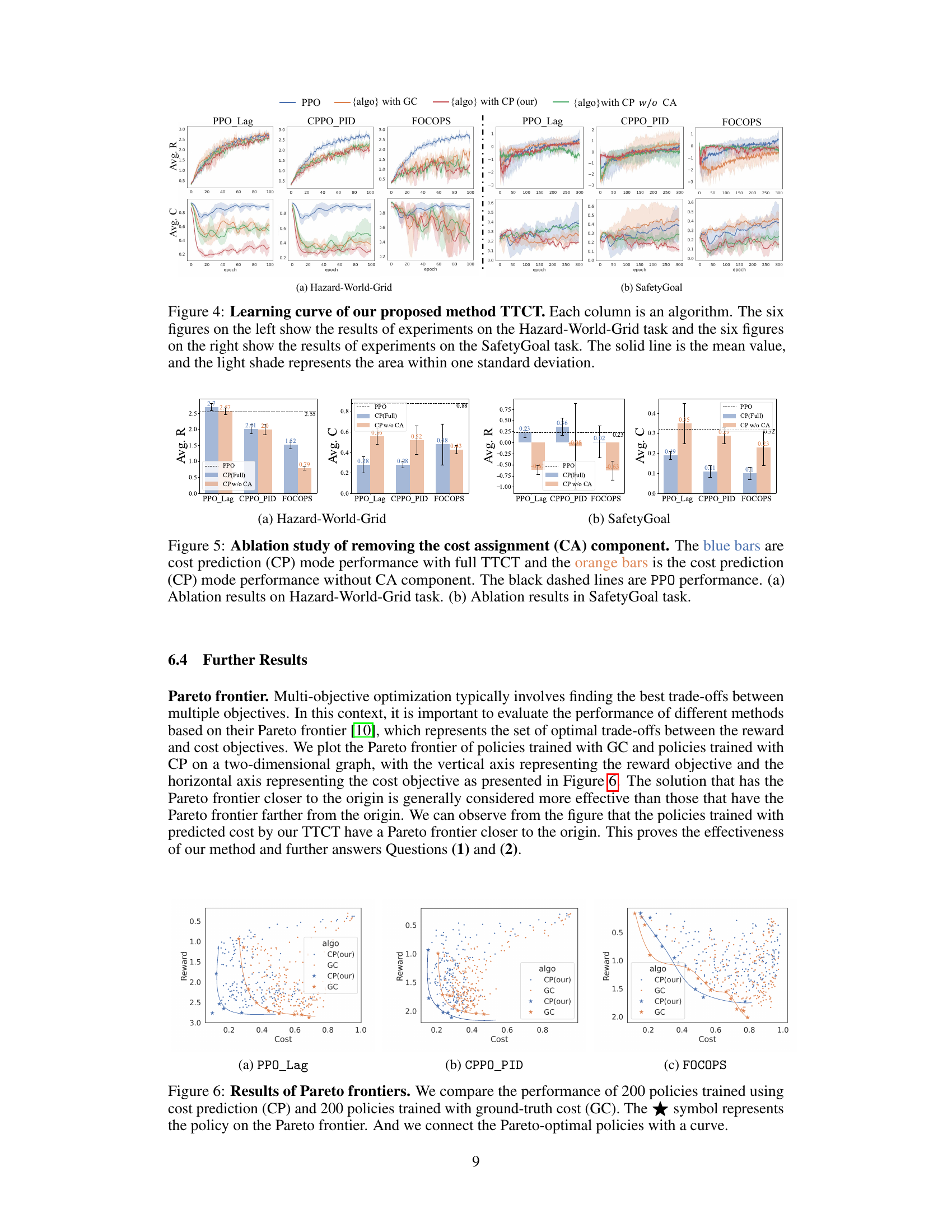

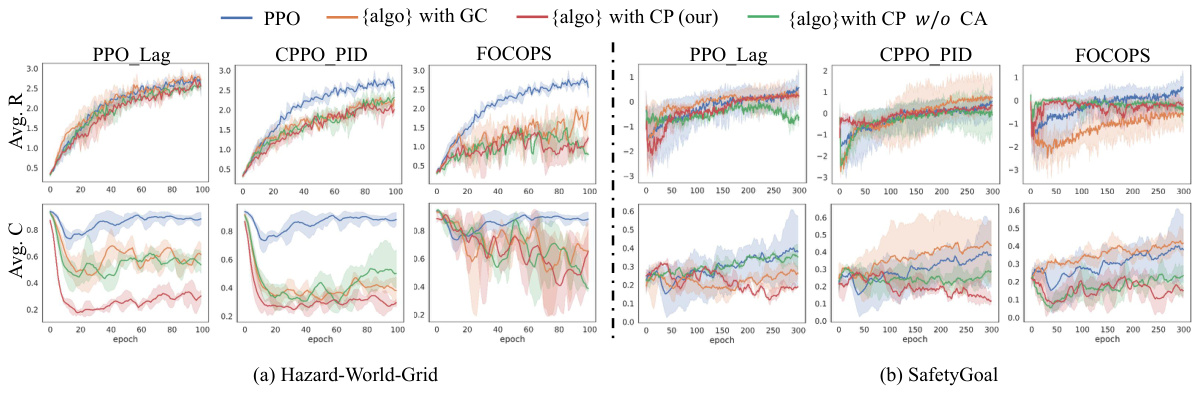

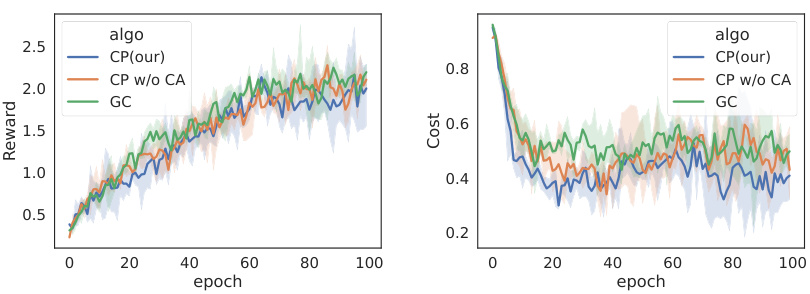

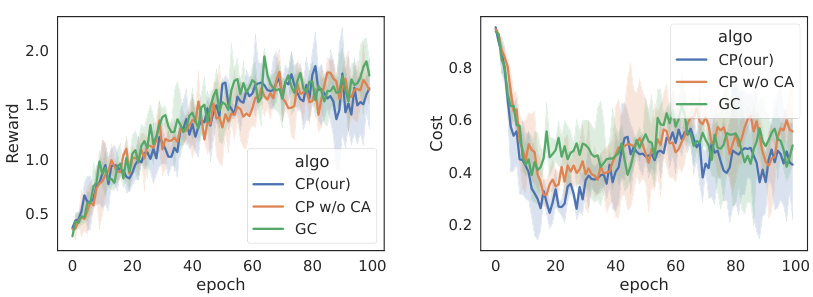

🔼 This figure presents the learning curves for different reinforcement learning algorithms applied to two different tasks: Hazard-World-Grid and SafetyGoal. The algorithms were trained using either ground-truth cost functions (GC) or predicted costs from the proposed TTCT method (CP), along with a version of CP without the cost assignment component (CP w/o CA) for ablation. The plots show the average reward and cost over training epochs, providing insights into the learning progress and performance of the algorithms under different cost calculation methods.

read the caption

Figure 4: Learning curve of our proposed method TTCT. Each column is an algorithm. The six figures on the left show the results of experiments on the Hazard-World-Grid task and the six figures on the right show the results of experiments on the SafetyGoal task. The solid line is the mean value, and the light shade represents the area within one standard deviation.

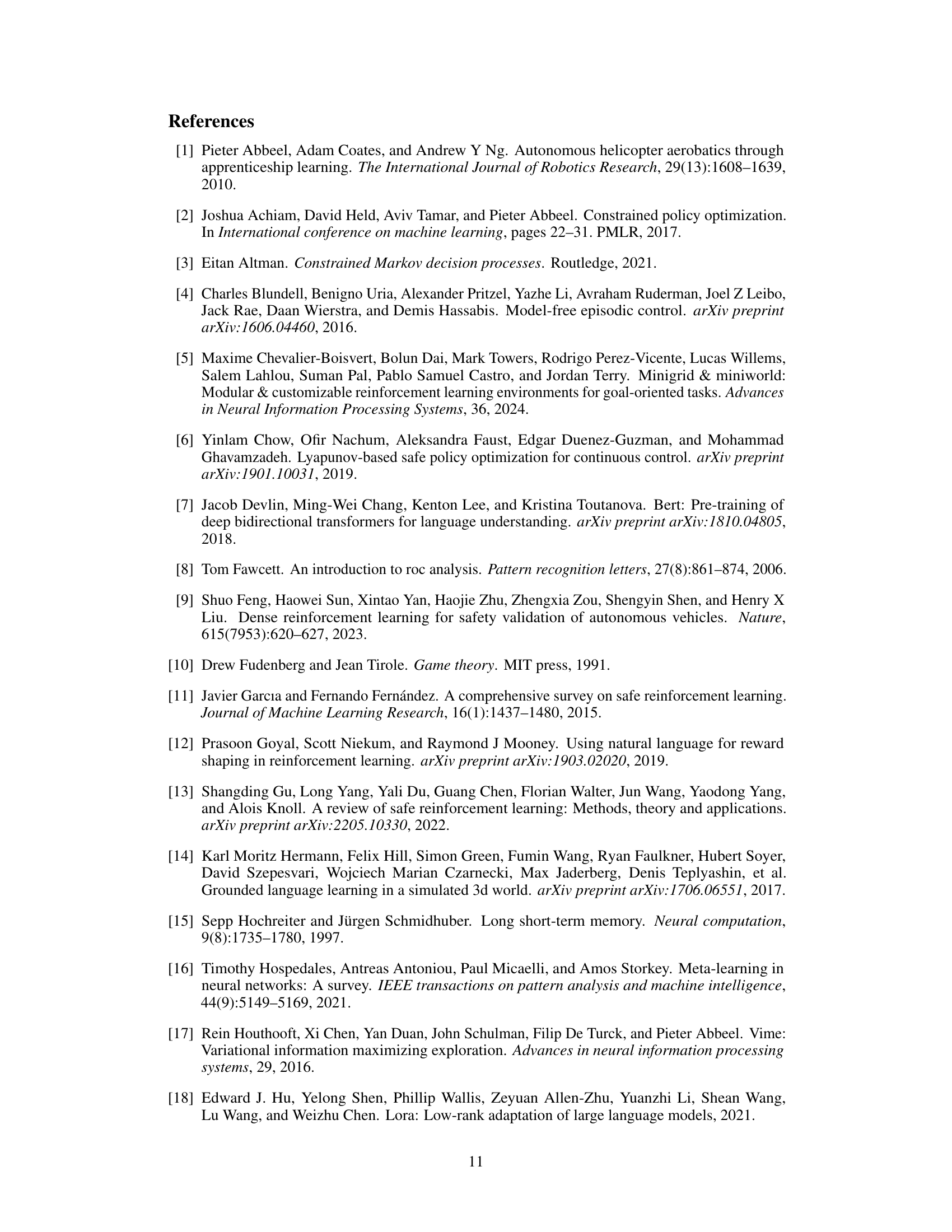

🔼 This figure presents the performance comparison between the proposed method (TTCT) and several baselines on two tasks: Hazard-World-Grid and SafetyGoal. It shows the average episodic reward (Avg. R) and average episodic cost (Avg. C) for each method. The blue bars represent the performance using the predicted cost from TTCT, while the orange bars represent performance using the ground truth cost. The black dashed lines represent the performance of the PPO baseline, which does not use constraints. The results demonstrate TTCT’s effectiveness in achieving lower violation rates (Avg. C) while maintaining comparable rewards (Avg. R) to baselines using ground truth cost.

read the caption

Figure 3: Evaluation results of our proposed method TTCT. The blue bars are our proposed cost prediction (CP) mode performance and the orange bars are the ground-truth cost (GC) mode performance. The black dashed lines are PPO performance. (a) Results on Hazard-World-Grid task. (b) Results on SafetyGoal task.

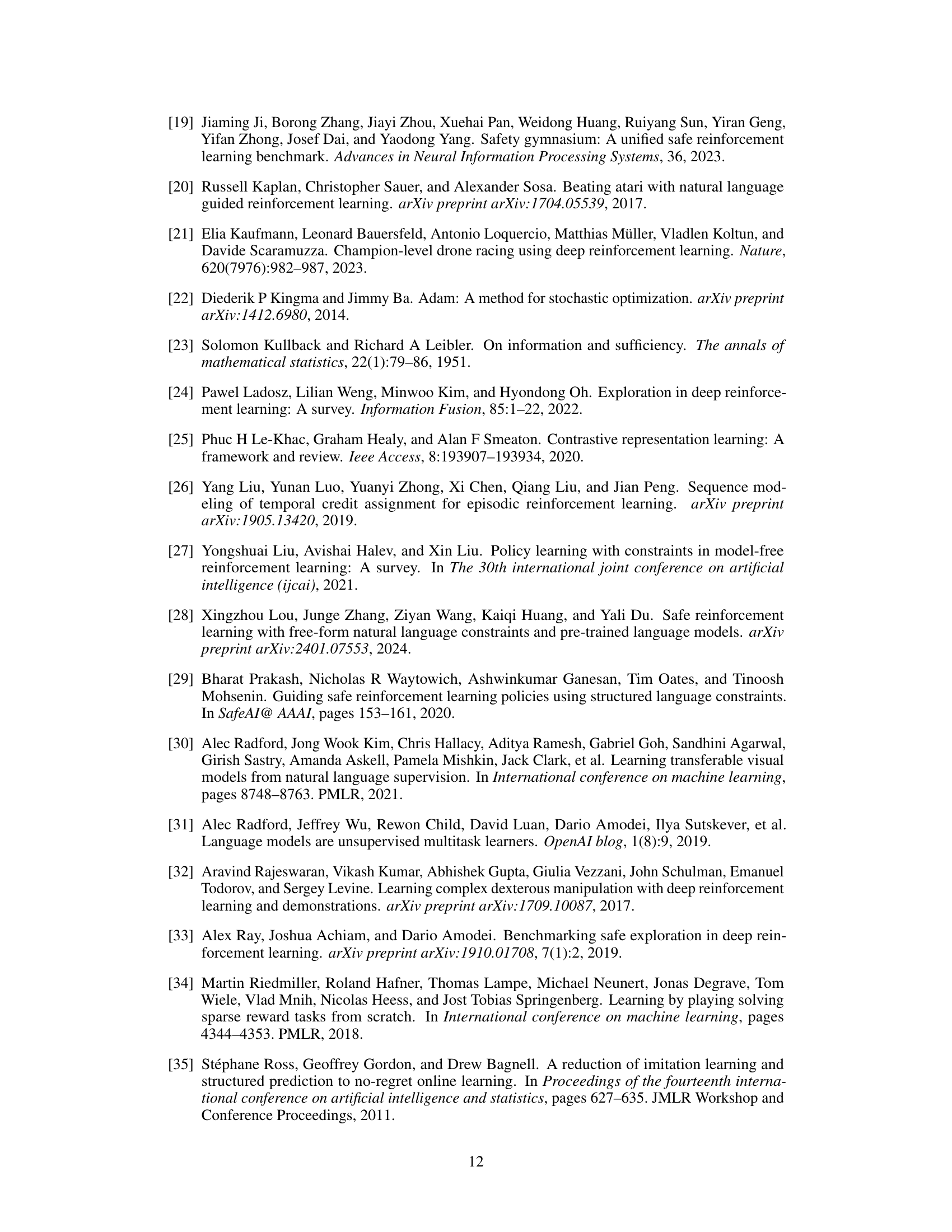

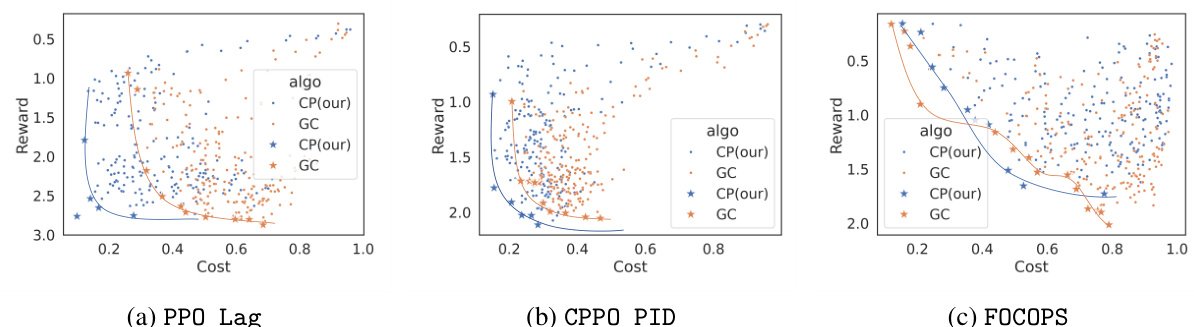

🔼 This figure compares the performance of policies trained using cost prediction (CP) and ground truth cost (GC) in terms of reward and cost. The Pareto frontier is plotted to showcase the optimal trade-offs between these two objectives. Policies trained with CP are shown to be closer to the ideal point (high reward, low cost) on the Pareto frontier, indicating better overall performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: Results of Pareto frontiers. We compare the performance of 200 policies trained using cost prediction (CP) and 200 policies trained with ground-truth cost (GC). The ★ symbol represents the policy on the Pareto frontier. And we connect the Pareto-optimal policies with a curve.

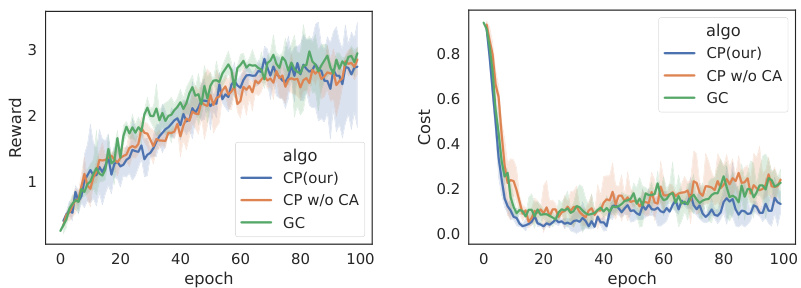

🔼 This figure presents the results of a zero-shot transfer experiment using the TTCT model. The model, trained on the Hazard-World-Grid environment, was directly applied to a new environment, LavaWall, without any fine-tuning. The left subplot shows the average reward obtained over training epochs, while the right subplot displays the average cost (violation rate). This demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to unseen environments.

read the caption

Figure 7: Zero-shot adaptation capability of TTCT on LavaWall task. The left figure shows the average reward and the right figure shows the average cost.

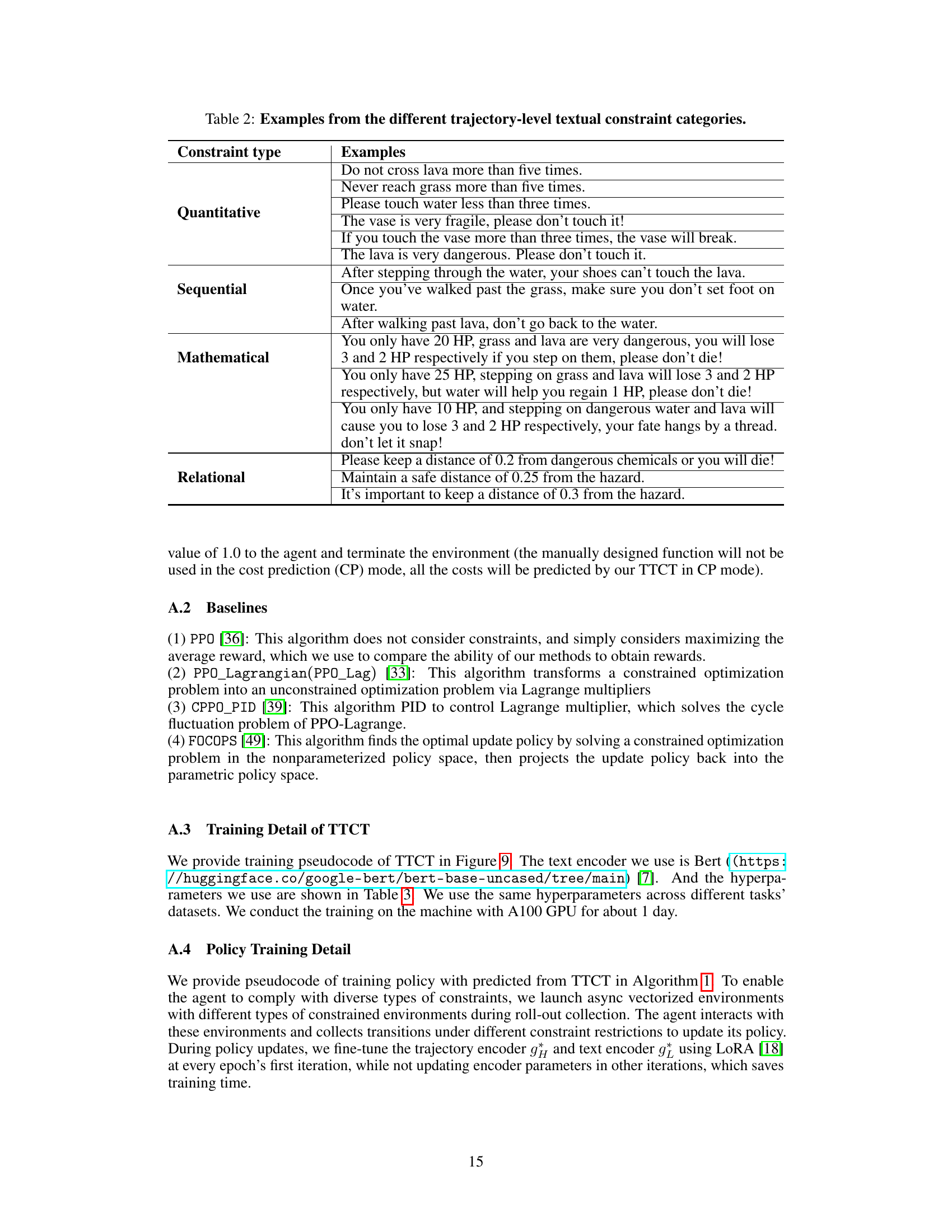

🔼 This figure provides a detailed overview of the Trajectory-level Textual Constraints Translator (TTCT) framework. It illustrates the two main components of TTCT: the text-trajectory alignment component and the cost assignment component. The text-trajectory alignment component uses a multimodal architecture to connect trajectory and text data, enabling the prediction of whether a trajectory violates a given constraint. The cost assignment component then assigns a cost value to each state-action pair based on its impact on constraint satisfaction. This dual-component structure is crucial for both predicting constraint violations and addressing the issue of sparse costs in safe reinforcement learning.

read the caption

Figure 1: TTCT overview. TTCT consists of two training components: (1) the text-trajectory alignment component connects trajectory to text with multimodal architecture, and (2) the cost assignment component assigns a cost value to each state-action based on its impact on satisfying the constraint. When training RL policy, the text-trajectory alignment component is used to predict whether a trajectory violates a given constraint and the cost assignment component is used to assign non-violation cost.

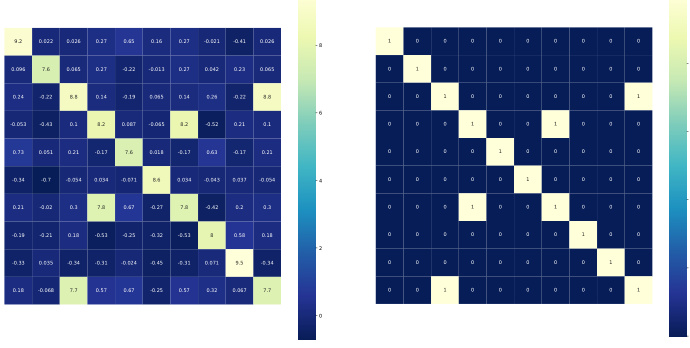

🔼 This figure shows two heatmaps visualizing the cosine similarity between trajectory and text embeddings. The left heatmap displays the cosine similarity after scaling, while the right heatmap shows the ground truth similarity. The color intensity in each heatmap represents the strength of the similarity, with lighter colors indicating higher similarity and darker colors indicating lower similarity. This visualization is used to evaluate the performance of the text-trajectory alignment component in accurately capturing the relationship between trajectory and text representations.

read the caption

Figure 10: Heatmap of cosine similarity between trajectory and text embeddings.

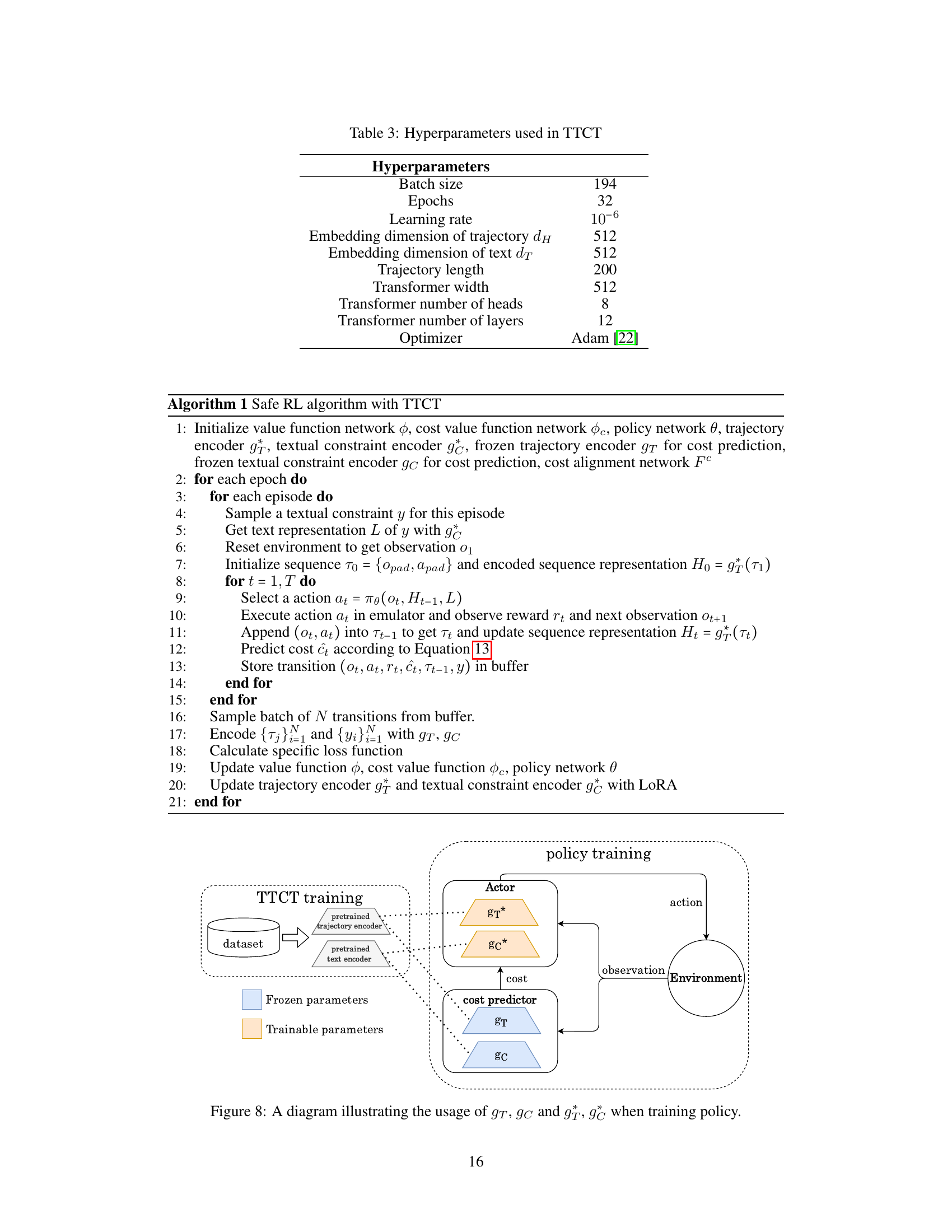

🔼 This ROC curve demonstrates the performance of the text-trajectory alignment component in predicting whether a trajectory violates a given textual constraint. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) of 0.98 indicates high accuracy in distinguishing between violating and non-violating trajectories.

read the caption

Figure 11: ROC curve of text-trajectory alignment component. The x-axis represents the false positive rate, and the y-axis represents the true positive rate. The closer the AUC value is to 1, the better the performance of the model; conversely, the closer the AUC value is to 0, the worse the performance of the model.

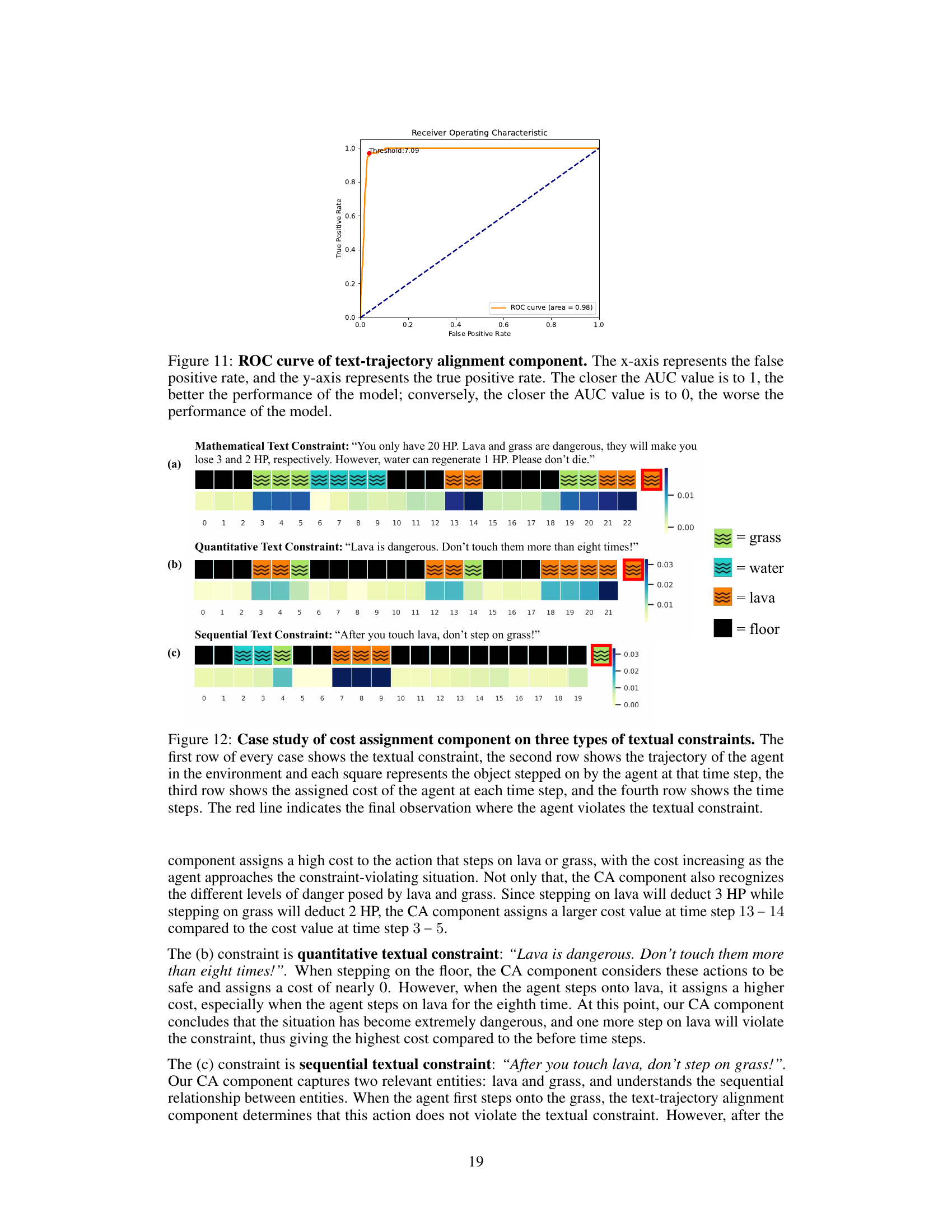

🔼 This figure presents a case study of the cost assignment component of the TTCT model. It showcases how the model assigns costs to state-action pairs based on three different types of textual constraints: quantitative, sequential, and mathematical. Each row represents a different type of constraint, with the agent’s trajectory displayed in the second row, the cost assigned by the model in the third row and the time step at the bottom. The red line in the second row highlights the point in the trajectory where the textual constraint was violated. This case study helps to visualize and understand how the cost assignment component works in practice.

read the caption

Figure 12: Case study of cost assignment component on three types of textual constraints. The first row of every case shows the textual constraint, the second row shows the trajectory of the agent in the environment and each square represents the object stepped on by the agent at that time step, the third row shows the assigned cost of the agent at each time step, and the fourth row shows the time steps. The red line indicates the final observation where the agent violates the textual constraint.

🔼 This figure displays the learning curves for the proposed TTCT method and several baseline algorithms across two different tasks: Hazard-World-Grid and SafetyGoal. The plots show the average reward and cost over training epochs for each algorithm. Shaded regions indicate the standard deviation, providing insight into the variability of the performance. The figure helps to illustrate the effectiveness of the TTCT model in comparison to baselines.

read the caption

Figure 4: Learning curve of our proposed method TTCT. Each column is an algorithm. The six figures on the left show the results of experiments on the Hazard-World-Grid task and the six figures on the right show the results of experiments on the SafetyGoal task. The solid line is the mean value, and the light shade represents the area within one standard deviation.

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves for different RL algorithms (PPO, PPO-Lagrangian, CPPO-PID, FOCOPS) trained with both ground-truth cost (GC) and predicted cost (CP) using the TTCT method. The left half shows the results from the Hazard-World-Grid environment, and the right half from SafetyGoal. It displays average reward and cost over training epochs, illustrating the performance of TTCT in reducing cost while maintaining reward.

read the caption

Figure 4: Learning curve of our proposed method TTCT. Each column is an algorithm. The six figures on the left show the results of experiments on the Hazard-World-Grid task and the six figures on the right show the results of experiments on the SafetyGoal task. The solid line is the mean value, and the light shade represents the area within one standard deviation.

🔼 This figure shows the training curves for different reinforcement learning algorithms applied to two different tasks (Hazard-World-Grid and SafetyGoal). For each algorithm, two versions are presented: one trained with ground-truth cost functions (GC) and another trained with the predicted costs generated by the proposed TTCT method (CP). The figure visually compares the performance of the proposed method and baselines across both tasks, showing reward and violation rate over the course of training. The shaded area represents standard deviation. This plot helps evaluate the effectiveness and stability of TTCT’s cost prediction.

read the caption

Figure 4: Learning curve of our proposed method TTCT. Each column is an algorithm. The six figures on the left show the results of experiments on the Hazard-World-Grid task and the six figures on the right show the results of experiments on the SafetyGoal task. The solid line is the mean value, and the light shade represents the area within one standard deviation.

🔼 The figure shows the inference time of the TTCT model for different trajectory lengths on the Hazard-World-Grid environment. The inference time is measured using a V100-32G GPU with a batch size of 64. The x-axis represents the trajectory length, and the y-axis represents the inference time in seconds. The graph shows a roughly linear increase in inference time as trajectory length increases, indicating that longer trajectories require more processing time from the model. This information is relevant to understanding the computational efficiency and scalability of the TTCT approach.

read the caption

Figure 14: Inference time of different trajectory lengths for Hazard-World-Grid on the V100-32G hardware device. Batch size is 64.

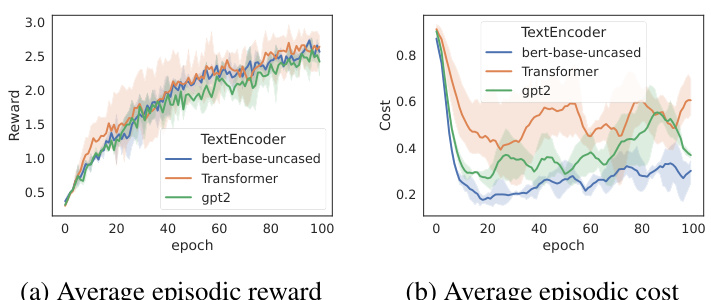

🔼 This figure displays the results of an empirical analysis conducted on the Hazard-World-Grid environment using three different text encoders: transformer-25M, gpt2-137M, and bert-base-uncased-110M. The analysis likely involves training reinforcement learning agents with these encoders and evaluating their performance across various metrics. The chart probably shows the average episodic reward and cost over training epochs for each encoder, allowing for a comparison of their effectiveness in achieving high rewards while minimizing costs.

read the caption

Figure 15: Empirical analyses on Hazard-World-Grid with varying text encoders. We choose three different models, transformer-25M [41], gpt2-137M [31], and bert-base-uncased-110M [7].

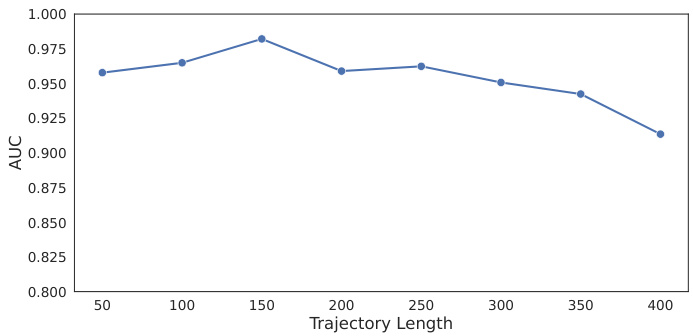

🔼 This figure shows the performance of the text-trajectory alignment component on the Hazard-World-Grid task with varying trajectory lengths. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) is plotted against the length of the trajectories. The results show that the performance improves initially with increasing trajectory length, but then begins to decline after a certain point. This suggests that the model’s ability to capture the relationships between the trajectory and the textual constraint is limited for very long trajectories. The limitations are thought to stem from the transformer’s encoding capacity.

read the caption

Figure 16: Evaluation results of different trajectory lengths for Hazard-World-Grid. Sets of trajectories with varying lengths shared the same set of textual constraints.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares trajectory-level constraints (proposed by the authors) with previous single state/entity constraints. Trajectory-level constraints offer greater flexibility and generality by modeling complex interactions among multiple entities and states across time, unlike single state/entity constraints which only consider individual states or entities. The table provides examples to highlight the difference in expressiveness and complexity between these two types of constraints.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of trajectory-level constraints and previous single state/entity constraints.

🔼 This table compares trajectory-level constraints (used in the proposed method) with the previous single state/entity constraints. It highlights the limitations of single state/entity constraints in modeling complex real-world scenarios involving multiple entities and states over time. Trajectory-level constraints offer a more universal approach to represent complex safety requirements and facilitate better generalization.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of trajectory-level constraints and previous single state/entity constraints.

🔼 This table presents the performance of the text-trajectory alignment component in predicting violations of textual constraints. It shows the accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score achieved by the component in classifying trajectories as either violating or not violating a given constraint.

read the caption

Table 4: Violations prediction results of text-trajectory alignment component.

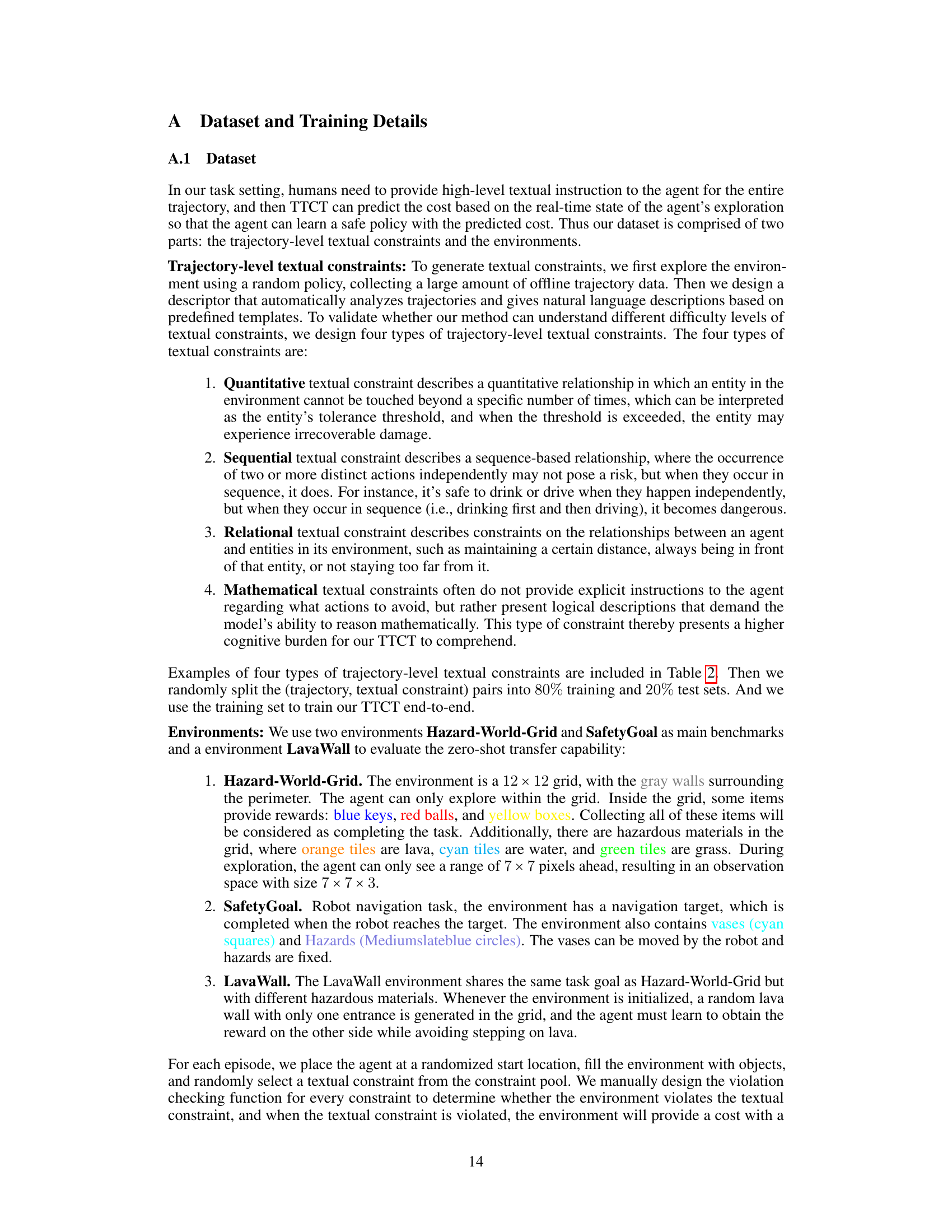

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used in the Trajectory-level Textual Constraints Translator (TTCT) model. These include parameters related to the training process (batch size, epochs, learning rate), the embedding dimensions of both trajectories and text, and characteristics of the transformer architecture used within the model (width, number of heads, number of layers). The optimizer used is also specified.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameters used in TTCT

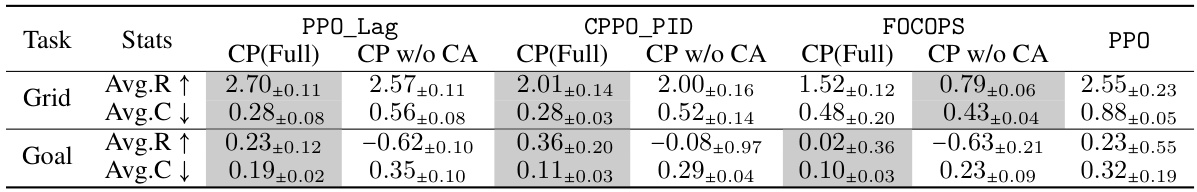

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results by removing the cost assignment component from the full TTCT model. It compares the average episodic reward (Avg.R) and average episodic cost (Avg.C) for different algorithms (PPO, PPO_Lag, CPPO_PID, FOCOPS) with and without the cost assignment component, as well as with the ground truth cost. The results are presented separately for the Hazard-World-Grid and SafetyGoal tasks. Higher Avg.R and lower Avg.C indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation study of removing the cost assignment (CA) component. ↑ means the higher the reward, the better the performance. ↓ means the lower the cost, the better the performance. Each value is reported as mean ± standard deviation and we shade the safest agents with the lowest averaged cost violation values for every algorithm.

Full paper#