TL;DR#

Many real-world applications rely on graph-based semi-supervised learning for node-level prediction tasks. However, obtaining labeled data is often expensive and time-consuming, leading to challenges in efficiently training accurate models. Existing active learning approaches often focus on online settings, requiring immediate feedback from human annotators, which can be impractical in real-world scenarios. Additionally, these methods rarely consider the presence of noise in node-level information and network structure.

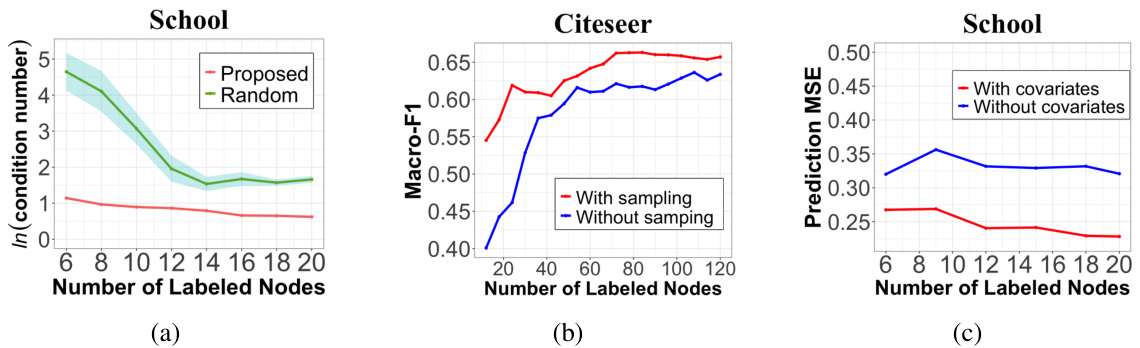

This paper presents a novel offline active learning method that addresses these issues. The method incorporates information from both the network structure and node covariates to select informative and representative nodes for labeling. It utilizes a two-stage biased sampling strategy that balances informativeness and representativeness, considering the trade-off between these two factors. The researchers have established a theoretical relationship between generalization error and the number of selected nodes, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method. Numerical experiments show that the proposed method significantly outperforms existing approaches, especially when dealing with noisy data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on graph-based semi-supervised learning, particularly those dealing with noisy data and high labeling costs. It offers a novel offline active learning method with theoretical guarantees, addressing limitations of existing online methods. This research opens new avenues for improving the efficiency and robustness of node-level prediction tasks in various real-world applications.

Visual Insights#

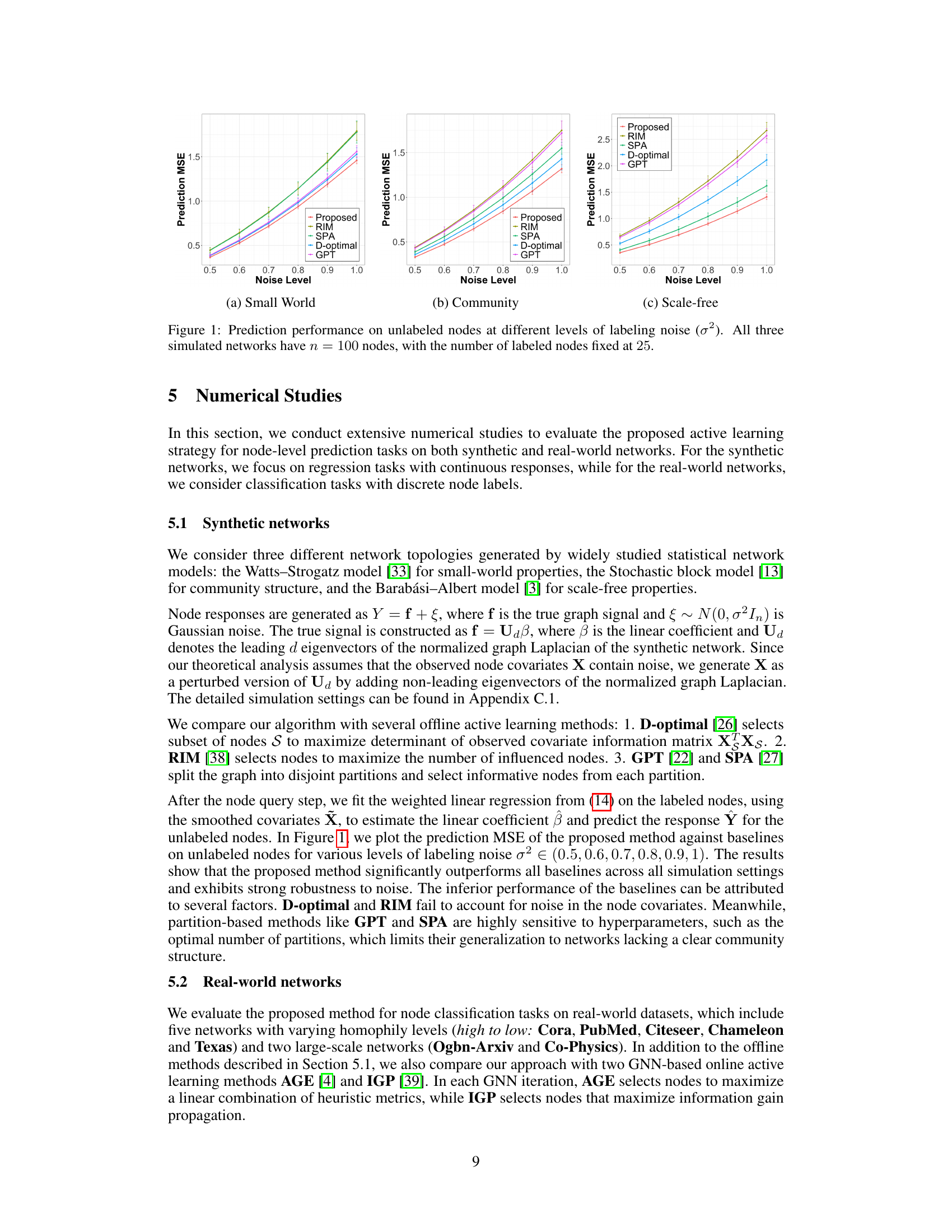

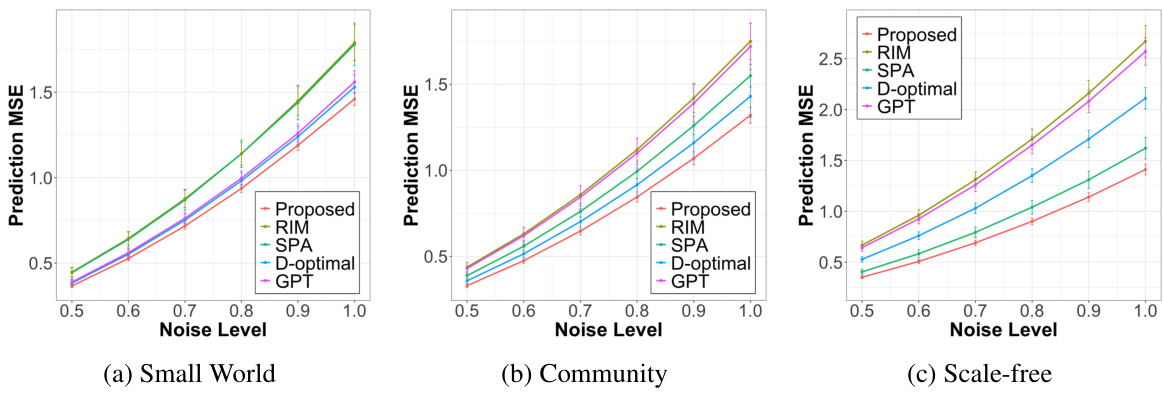

🔼 This figure displays the prediction performance (measured by Mean Squared Error or MSE) of different active learning methods on three different types of simulated networks (small-world, community, and scale-free) under varying levels of noise in the node labels. The x-axis represents the level of noise, and the y-axis represents the prediction MSE. Each line represents a different active learning method, including the proposed method and several baselines (RIM, SPA, D-optimal, and GPT). The plot shows the MSE on unlabeled nodes, demonstrating the effectiveness and robustness of each method in handling noisy data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction performance on unlabeled nodes at different levels of labeling noise (σ²). All three simulated networks have n = 100 nodes, with the number of labeled nodes fixed at 25.

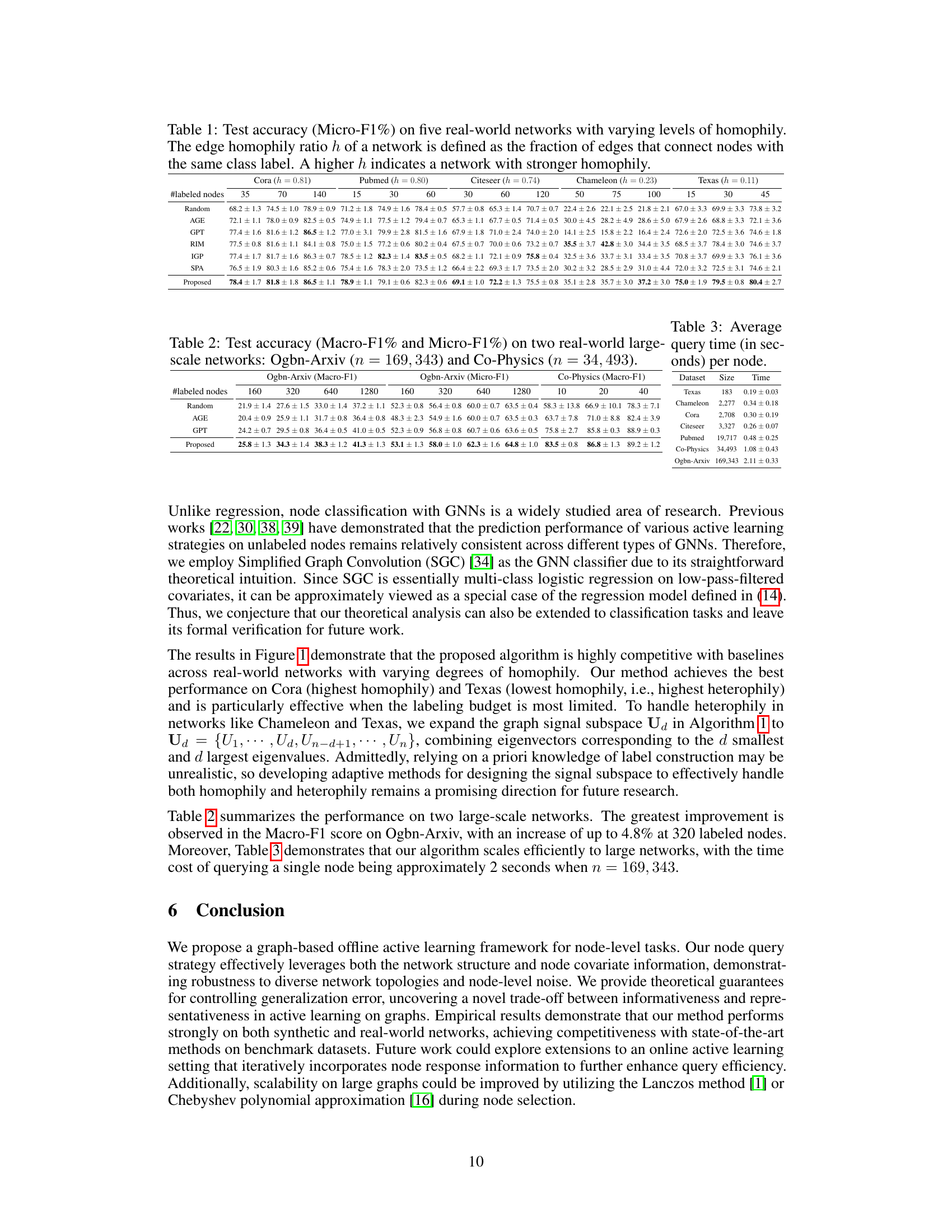

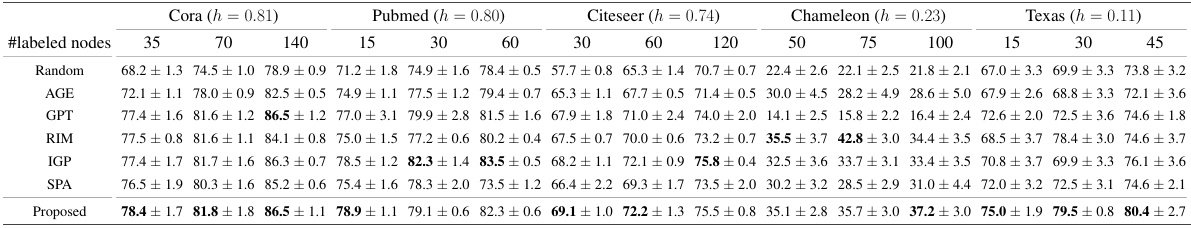

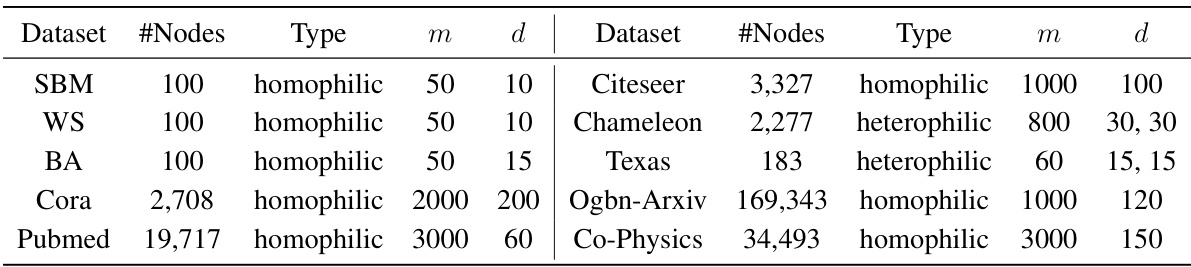

🔼 This table presents the Micro-F1 scores (%) achieved by different active learning methods (Random, AGE, GPT, RIM, IGP, SPA, and the proposed method) on five real-world networks (Cora, Pubmed, Citeseer, Chameleon, and Texas) with varying levels of homophily (edge homophily ratio ‘h’). The results are shown for different numbers of labeled nodes. Higher homophily indicates a stronger tendency for connected nodes to share the same class label.

read the caption

Table 1: Test accuracy (Micro-F1%) on five real-world networks with varying levels of homophily.

In-depth insights#

Graph Active Learning#

Graph active learning tackles the challenge of efficiently labeling nodes in large graphs, a crucial problem in numerous applications. The core idea is to strategically select a small subset of nodes for labeling, maximizing the information gained per label. Unlike passive learning which randomly samples nodes, active learning leverages graph structure (connectivity, community) and node attributes to guide the selection process. Effective algorithms balance informativeness (how much a node’s label reveals about others) and representativeness (how well the labeled nodes generalize to the unlabeled). This often involves iterative querying, where initially labeled nodes inform the selection of subsequent nodes. Theoretical analysis typically focuses on sample complexity (how many labels are needed) and generalization error bounds, often considering noisy labels and various graph topologies. Recent approaches increasingly integrate graph neural networks (GNNs), using GNN predictions to estimate informativeness and uncertainty. Key challenges remain in handling noisy data, scaling to massive graphs, and developing robust theoretical guarantees for complex network structures.

Offline Query Strategy#

An offline query strategy in active learning on graphs is crucial for scenarios where acquiring labels is expensive and iterative online feedback is infeasible. The core challenge is to strategically select a subset of nodes for labeling before any model training commences, maximizing the information gained from the limited labeling budget. Effective offline strategies must explicitly leverage both network structure and node covariates, going beyond simple heuristics based solely on node degree or centrality. A robust offline approach should account for potential noise in both network data and node labels, and ideally provide theoretical guarantees on the sample complexity and generalization error of the resulting model. Achieving this requires sophisticated methods that balance representativeness (ensuring the selected nodes are representative of the entire graph) and informativeness (choosing nodes that provide maximum information gain). Techniques such as graph signal processing, specifically graph spectral analysis, are valuable tools to model signal complexity and inform query selection. A greedy approach, iteratively selecting nodes that maximize an appropriate information gain metric (e.g., bandwidth frequency increase), is often employed, but needs to be carefully designed to ensure both representativeness and informativeness are considered. The development of a strong theoretical framework to analyze the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed offline query strategy is essential for its practical deployment and validation.

Informativeness/Representiveness#

The core of the proposed active learning method hinges on a novel trade-off between informativeness and representativeness. Informativeness focuses on selecting nodes that maximize the information gain about the underlying graph signal, prioritizing nodes that contribute to resolving complex signal patterns. This is achieved by leveraging graph spectral theory to quantify signal complexity and smoothness. The representativeness aspect addresses the robustness of model predictions against noisy data, aiming to select nodes that comprehensively represent the overall feature space and generalize well to unseen data. This is tackled via a biased sequential sampling strategy that employs spectral sparsification techniques, ensuring a well-conditioned covariance matrix and a lower bound on the generalization error. The interplay between these two factors is crucial: high informativeness alone can lead to overfitting to noisy data, while high representativeness without sufficient informativeness can result in poor signal recovery. The method’s strength lies in strategically balancing these competing criteria, leading to a more robust and efficient active learning approach.

Noise Robustness#

The concept of ‘Noise Robustness’ in the context of a graph-based active learning algorithm is crucial. The paper likely investigates how well the algorithm performs when dealing with noisy data, which is essential for real-world applications. Noisy data can manifest in various ways: noisy node labels (incorrect annotations), noisy node features (inaccuracies in measured attributes), or even noisy graph structure (missing or misrepresented connections). The algorithm’s robustness is evaluated by assessing its performance under varying levels of noise. Key aspects would include the selection strategy for nodes to label: does it prioritize informative nodes that are less sensitive to noise, and how does the algorithm handle the uncertainties introduced by noisy data during its learning process? The analysis likely includes a theoretical investigation (e.g., error bounds, generalization error analysis) and experimental results demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to maintain accuracy even with significant noise levels. The theoretical work would possibly use techniques from robust statistics or learning theory to provide guarantees about its performance. The experimental results would likely show its competitive performance against other active learning methods in noisy settings, providing quantitative evidence of the algorithm’s noise robustness.

Scalability Challenges#

Scalability is a critical concern in graph-based active learning, particularly when dealing with massive real-world networks. Computational costs associated with selecting informative nodes, such as calculating information gain metrics or performing spectral analysis, grow rapidly with the number of nodes and edges. Memory constraints become significant when handling large graph representations and feature vectors. Data storage and access present additional challenges, particularly when dealing with distributed or heterogeneous data sources. Algorithmic complexity of existing methods, often reliant on iterative or computationally expensive operations, becomes a major bottleneck for large-scale datasets. Parallel and distributed computing techniques are vital to mitigate these issues, but require careful design and implementation to avoid communication overheads and ensure efficiency. Approximation and sampling strategies may be necessary to make the problem tractable, but these introduce trade-offs between accuracy and scalability. Therefore, addressing scalability demands innovative approaches in algorithm design, data management, and computational infrastructure.

More visual insights#

More on figures

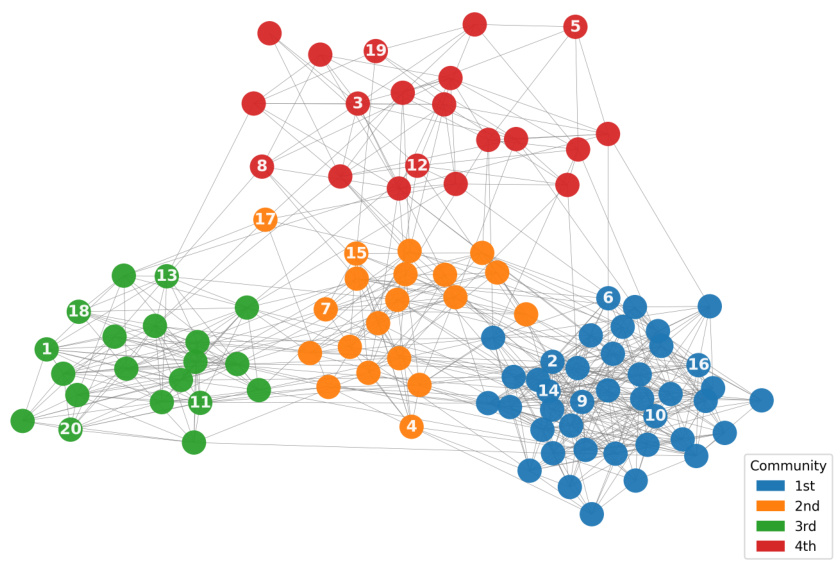

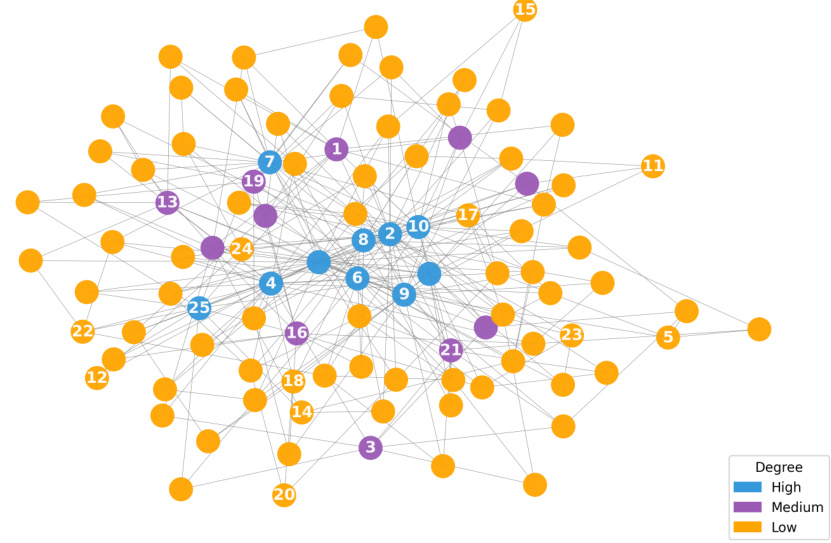

🔼 This figure visualizes the node query process on two synthetic networks generated using the Stochastic Block Model (SBM) and the Barabási-Albert model (BA). In (a), nodes in the SBM network are color-coded by their community assignments. In (b), nodes in the BA network are color-coded by their degree. In both subfigures, each node is labeled with the order in which it was selected by the proposed active learning algorithm. This illustrates how the algorithm’s query selection adapts to the different network structures.

read the caption

Figure 2: For (a) SBM, nodes are grouped by the assigned community; for (b) BA, nodes are grouped by degree. The integer i on each node represents the ith node queried by the proposed algorithm in one replication.

🔼 This figure visualizes the node query process on two synthetic networks generated using the Stochastic Block Model (SBM) and the Barabási-Albert model (BA). In SBM, nodes are grouped by community, while in BA, nodes are grouped by degree. The integer on each node represents the order in which the node was selected by the proposed algorithm during a single replication. This helps visualize how the algorithm selects nodes based on community structure (SBM) or degree (BA).

read the caption

Figure 2: For (a) SBM, nodes are grouped by the assigned community; for (b) BA, nodes are grouped by degree. The integer i on each node represents the ith node queried by the proposed algorithm in one replication.

🔼 This figure shows the prediction performance (measured by Mean Squared Error or MSE) of different active learning methods on three different types of synthetic networks (small-world, community, and scale-free) under varying levels of noise in the node labels. The noise level (σ²) is shown on the x-axis, ranging from 0.5 to 1.0. The y-axis represents the prediction MSE. The methods being compared include the proposed method and four other existing methods (RIM, SPA, D-optimal, and GPT). The results show that the proposed method generally outperforms the other methods, especially as the noise level increases. The fact that the performance is relatively consistent across different network types further demonstrates the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed method.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction performance on unlabeled nodes at different levels of labeling noise (σ²). All three simulated networks have n = 100 nodes, with the number of labeled nodes fixed at 25.

More on tables

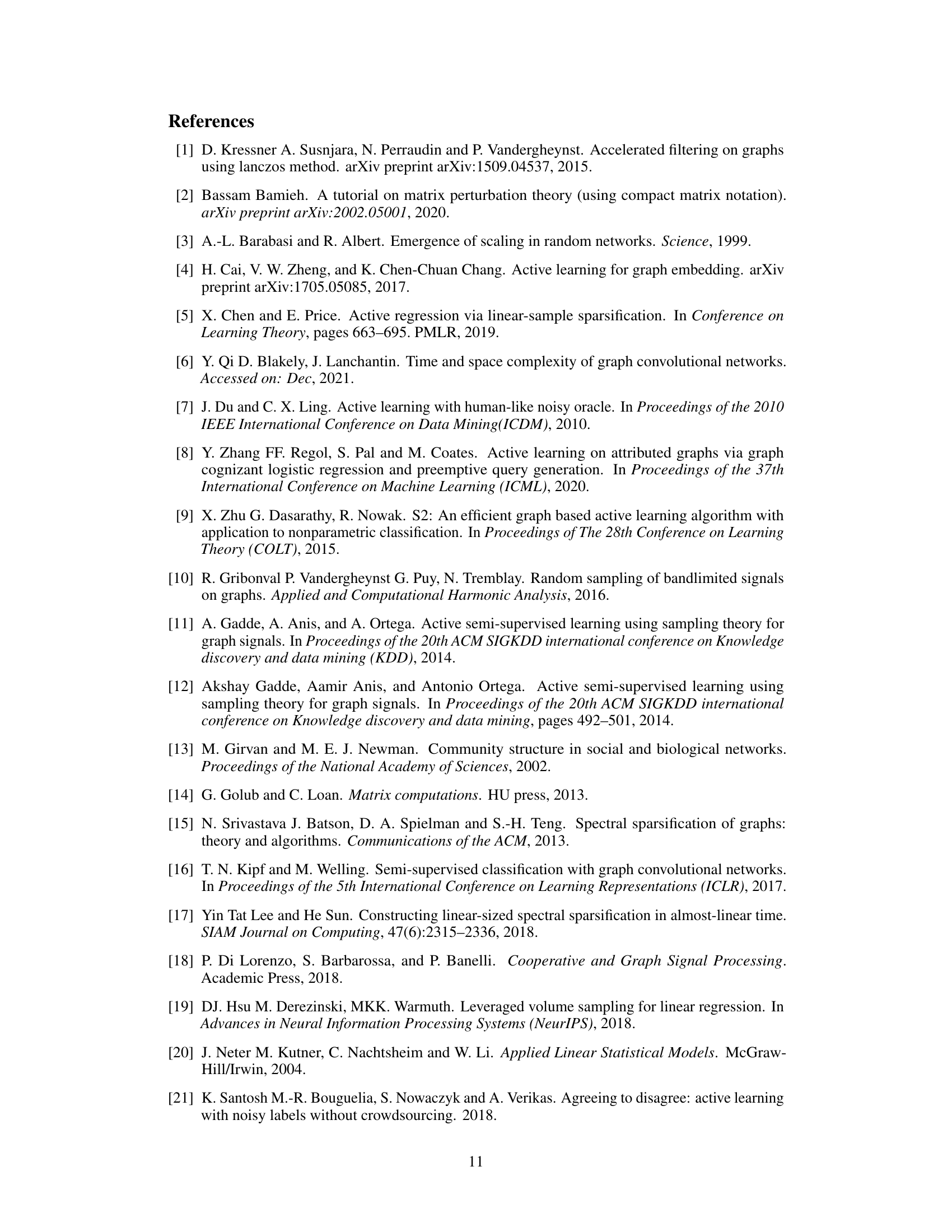

🔼 This table presents the Macro-F1 and Micro-F1 scores achieved by four different node selection methods (Random, AGE, GPT, and the proposed method) on two large real-world networks (Ogbn-Arxiv and Co-Physics) for a node classification task. The results are shown for different numbers of labeled nodes, demonstrating the performance of each method under varying data scarcity.

read the caption

Table 2: Test accuracy (Macro-F1% and Micro-F1%) on two real-world large-scale networks: Ogbn-Arxiv (n = 169, 343) and Co-Physics (n = 34, 493).

🔼 This table presents the test accuracy (in terms of Micro-F1 scores) achieved by different active learning methods on five real-world networks with varying levels of homophily. Homophily refers to the tendency of nodes with the same label to be connected. The table shows the performance for different numbers of labeled nodes and allows comparison of several methods, including the proposed one, across different network structures.

read the caption

Table 1: Test accuracy (Micro-F1%) on five real-world networks with varying levels of homophily. The edge homophily ratio h of a network is defined as the fraction of edges that connect nodes with the same class label. A higher h indicates a network with stronger homophily.

Full paper#