↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) models often lack interpretability, hindering their real-world application. Existing methods for extracting decision trees (DTs) from DRL policies often lack performance guarantees, especially in multi-agent settings. Furthermore, most prior attempts to design DT policies in multi-agent scenarios rely on heuristics without providing any quantitative guarantees.

This paper introduces a novel Return-Gap-Minimizing Decision Tree (RGMDT) algorithm. RGMDT recasts the DT extraction problem as a non-Euclidean clustering problem, leveraging the action-value function to obtain a closed-form guarantee on the return gap between the oracle policy and the extracted DT policy. The algorithm and its theoretical guarantees are extended to multi-agent settings via an iteratively-grow-DT procedure, which ensures the global optimality of the resulting joint return. Experiments demonstrate that RGMDT significantly outperforms existing methods on various tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in interpretable reinforcement learning and multi-agent systems. It addresses the critical need for explainable AI by providing a novel method to extract interpretable decision trees from complex deep reinforcement learning policies. This method offers theoretical guarantees on the performance, opening up new avenues for research in both single-agent and multi-agent scenarios.

Visual Insights#

This figure displays the results of experiments conducted on maze tasks with varying complexities. The bar chart (a-c) shows that RGMDT outperforms other methods by completing the tasks in fewer steps, especially in more complex scenarios. The line chart (d-f) shows that RGMDT achieves higher average episode rewards compared to baselines across all complexities, demonstrating its effectiveness in minimizing the return gap.

This table presents the results of the RGMDT algorithm, compared to CART, RF, and ET baselines on the Hopper task from the D4RL dataset. The results are shown for different training sample sizes (80,000 and 800,000) and DT node counts (40 and 64). The table demonstrates that RGMDT consistently outperforms the baselines, achieving higher rewards, especially with smaller sample sizes and fewer nodes. This highlights the efficiency of RGMDT in learning concise, effective decision trees even with limited data.

In-depth insights#

Return Gap Bound#

The concept of a ‘Return Gap Bound’ in reinforcement learning is crucial for evaluating the performance of approximate policies, especially those generated from complex models like deep reinforcement learning agents. A return gap bound quantifies the difference between the expected return of an optimal policy and that of an approximation, providing a guarantee on the suboptimality of the approximation. Establishing such a bound is essential because directly comparing the performance of a learned policy to an optimal one can be computationally infeasible. The tightness of this bound also matters as a loose bound will not provide meaningful insights. The existence of a return gap bound allows researchers to evaluate the performance of their method. This is particularly important in applications where it is essential to have confidence in the expected performance of the method and the decision-making process.

Non-Euclidean Clustering#

The concept of Non-Euclidean Clustering, as applied in this research paper, presents a novel approach to extracting interpretable decision trees (DTs) from complex, black-box reinforcement learning (RL) models. Traditional clustering methods often rely on Euclidean distance metrics, which are not always suitable for high-dimensional or non-linear data spaces commonly found in RL. This paper overcomes this limitation by introducing a non-Euclidean metric, likely based on the cosine similarity between action-value vectors. This choice is motivated by the underlying structure of the RL problem, where the goal is to map observations to actions, and the cosine similarity captures the relationships between the action-value vectors in a way that Euclidean distance cannot. By recasting the DT extraction problem as a non-Euclidean clustering problem, the authors effectively leverage the inherent structure of the RL data. The non-Euclidean distance measure allows for the identification of clusters that are semantically similar based on their action values, leading to a more interpretable and accurate DT representation. The algorithm’s effectiveness stems from its ability to capture non-linear relationships and to optimize the clustering process based on a meaningful distance metric tailored to the RL setting. This leads to improved accuracy and interpretability of the resulting DTs compared to traditional approaches.

Iterative DT Growth#

The concept of ‘Iterative DT Growth’ in the context of decision tree extraction from reinforcement learning policies suggests a dynamic and adaptive approach to building the decision tree. Instead of a single-pass construction, this method iteratively refines the tree structure. Each iteration likely involves evaluating the current tree’s performance, identifying areas for improvement (e.g., high return gap regions), and growing the tree by adding new nodes or branches in those areas. This incremental process allows for a more nuanced representation of the policy, potentially reducing the overall return gap between the learned decision tree and the original policy. The iterative nature enables the algorithm to handle complex policies more effectively, rather than relying on a single, potentially suboptimal, decision tree structure. The method also suggests a mechanism for integrating feedback and learning from the environment during the tree construction. A key aspect would be a formal definition of the stopping criteria to avoid overfitting. Efficiency is crucial, as each iteration adds to the computational cost; thus, efficient methods for tree evaluation and refinement are essential for practical applicability.

Multi-Agent Extension#

Extending single-agent decision tree (DT) methods to multi-agent scenarios presents unique challenges. Decentralized decision-making necessitates that each agent’s DT considers the actions and potential DTs of other agents, leading to a complex interdependence. A naive approach of independently training DTs for each agent would likely yield suboptimal results due to the lack of coordination. Therefore, a method for iterative DT construction is crucial, where each agent’s DT is updated based on the current DTs of others. This iterative process ensures that agents’ decisions are coordinated to maximize overall performance. A theoretical framework for analyzing the return gap in multi-agent settings must also be established, allowing for a quantitative measure of the DT policy’s suboptimality. This framework could be based on an upper bound of the expected return gap, potentially taking into account factors like the number of agents and the complexity of each agent’s DT. Finally, algorithms for efficiently constructing and updating decentralized DTs need to be developed, balancing computational cost with accuracy and interpretability. This could involve employing techniques such as non-Euclidean clustering or other specialized clustering methods to group observations and actions appropriately for DT generation.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this Return-Gap-Minimizing Decision Tree (RGMDT) framework could explore several promising avenues. Extending RGMDT to handle continuous state and action spaces is crucial for broader applicability. This might involve adapting the non-Euclidean clustering to continuous domains, perhaps using kernel methods or other techniques for measuring similarity between action-value vectors. Investigating alternative clustering algorithms beyond SVM, such as those with better scalability or inherent robustness to noise, could improve RGMDT’s efficiency and performance. A thorough theoretical analysis of the algorithm’s convergence properties and its sensitivity to hyperparameters would further solidify its foundation. Finally, empirical evaluations on a wider range of multi-agent tasks, including those with more complex reward structures and varying degrees of cooperation and competition, are needed to fully assess the generalizability and practical impact of RGMDT.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the performance comparison between RGMDT and several baselines on three maze tasks with increasing complexity. The bar charts (a-c) illustrate the number of steps to complete each task, showing RGMDT’s superior efficiency. The line charts (d-f) display the mean episode rewards, demonstrating RGMDT’s ability to achieve higher rewards even in complex scenarios, thus minimizing the return gap.

This figure displays the results of experiments conducted on maze tasks with varying difficulty levels. The bar charts (a-c) compare the number of steps taken by RGMDT and several baseline algorithms to complete the tasks. The line charts (d-f) show a comparison of the average episode rewards obtained by these algorithms. The results demonstrate that RGMDT consistently outperforms the baselines in both metrics, highlighting its effectiveness in minimizing the return gap, particularly in complex scenarios.

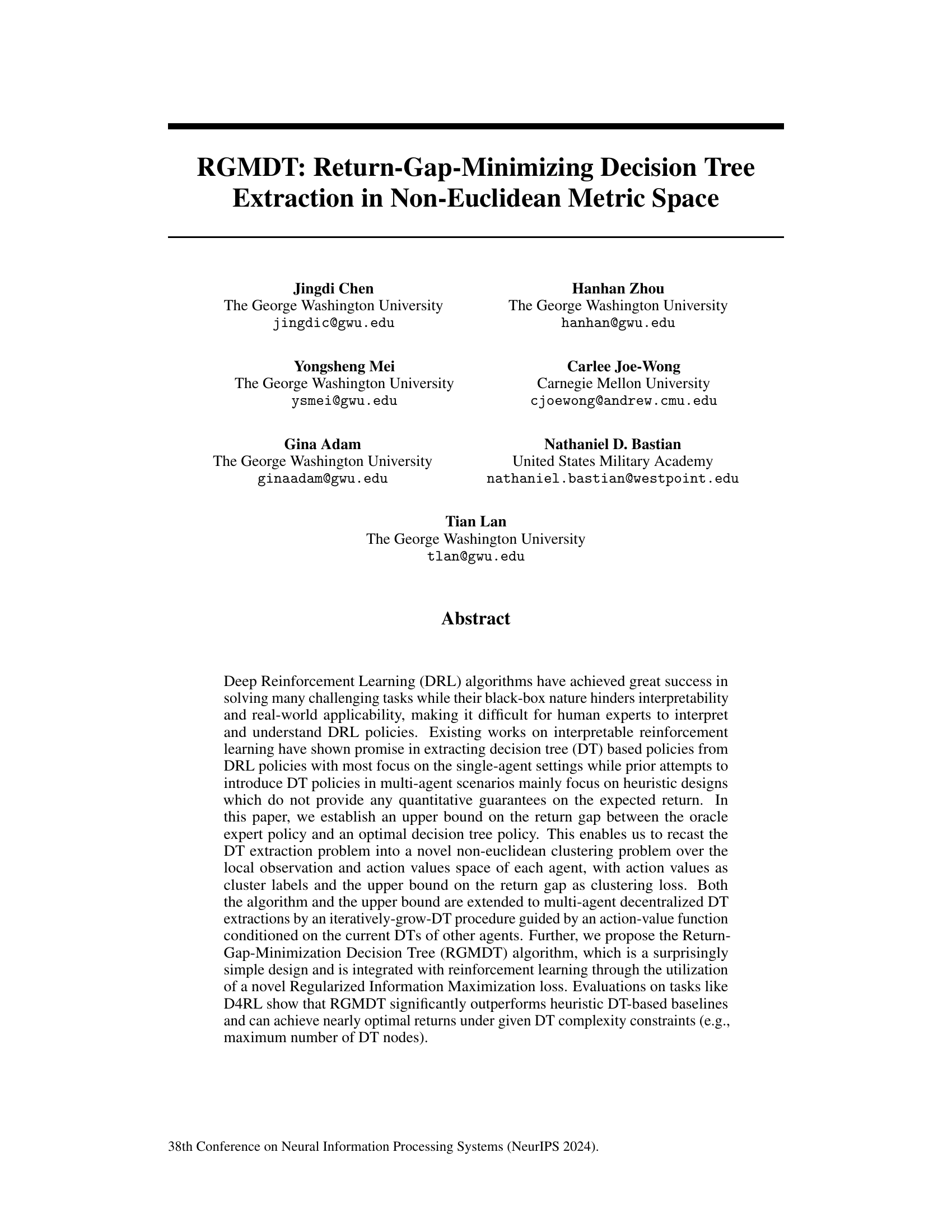

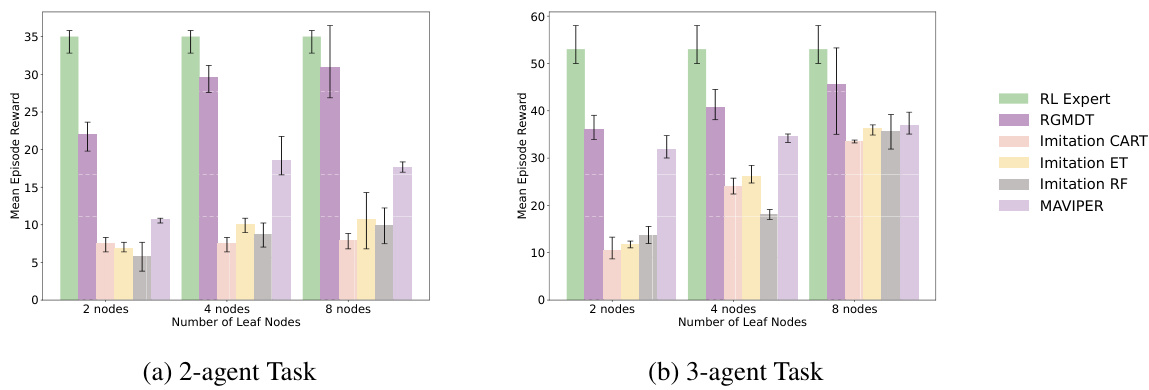

This figure compares the performance of RGMDT against several baselines on multi-agent tasks with varying complexities. The tasks involve 2 or 3 agents and different numbers of leaf nodes in the decision tree. The results demonstrate that RGMDT significantly outperforms the baselines in terms of both speed and final reward, especially when the number of leaf nodes is limited. This showcases RGMDT’s effectiveness in learning complex multi-agent tasks efficiently even under constrained model complexity.

This figure shows the relationship between the return gap and the average cosine distance for different numbers of leaf nodes in a decision tree. The return gap represents the difference in performance between an optimal policy and a decision tree policy. The average cosine distance measures the similarity of action-value vectors within each cluster. The figure demonstrates that a smaller return gap is achieved with a smaller average cosine distance, and that this relationship is improved by increasing the number of leaf nodes in the tree.

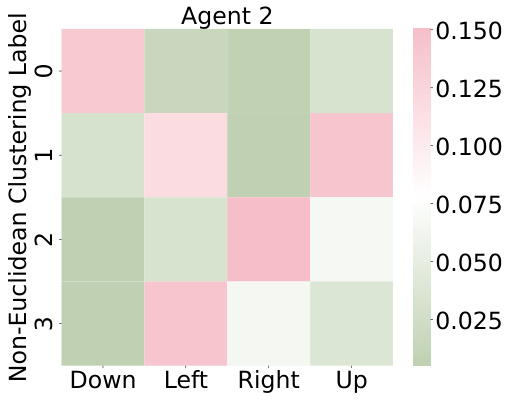

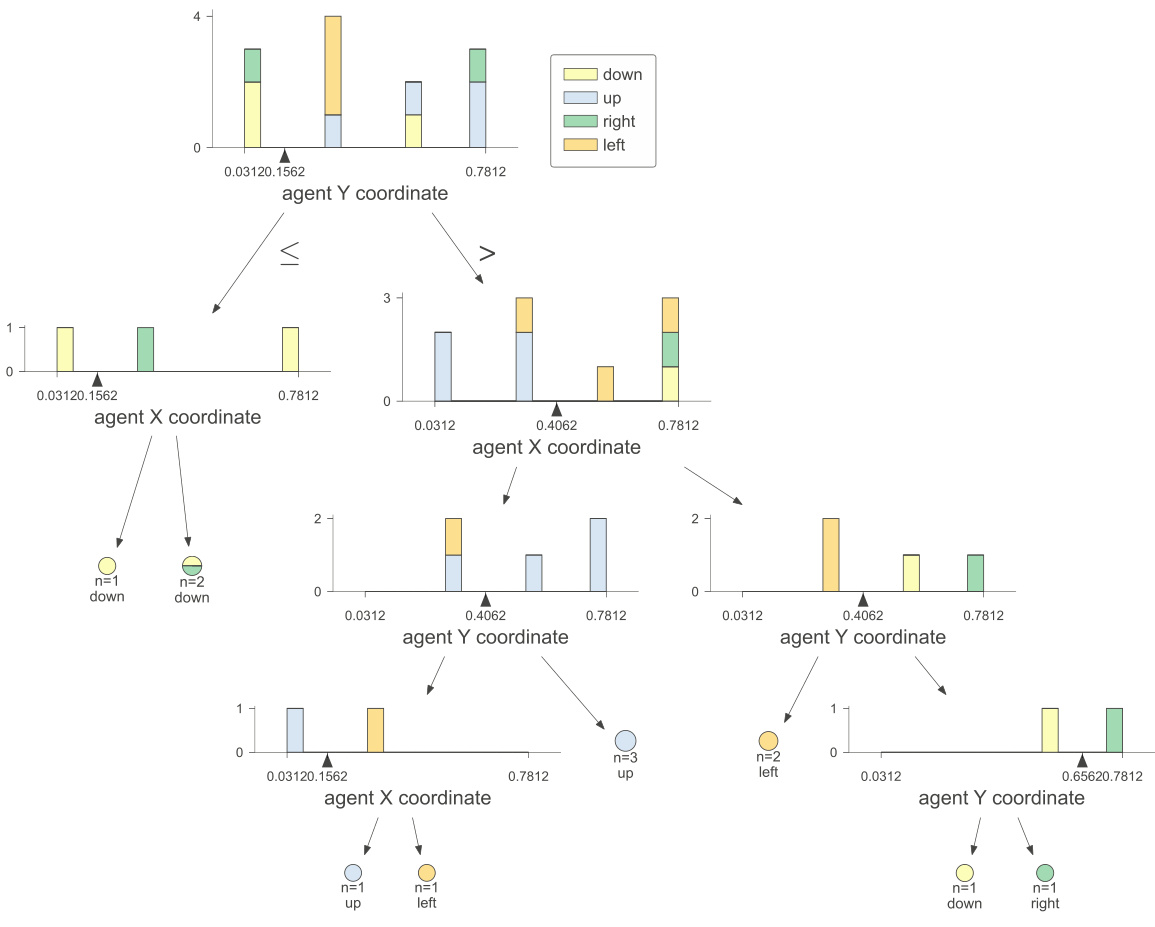

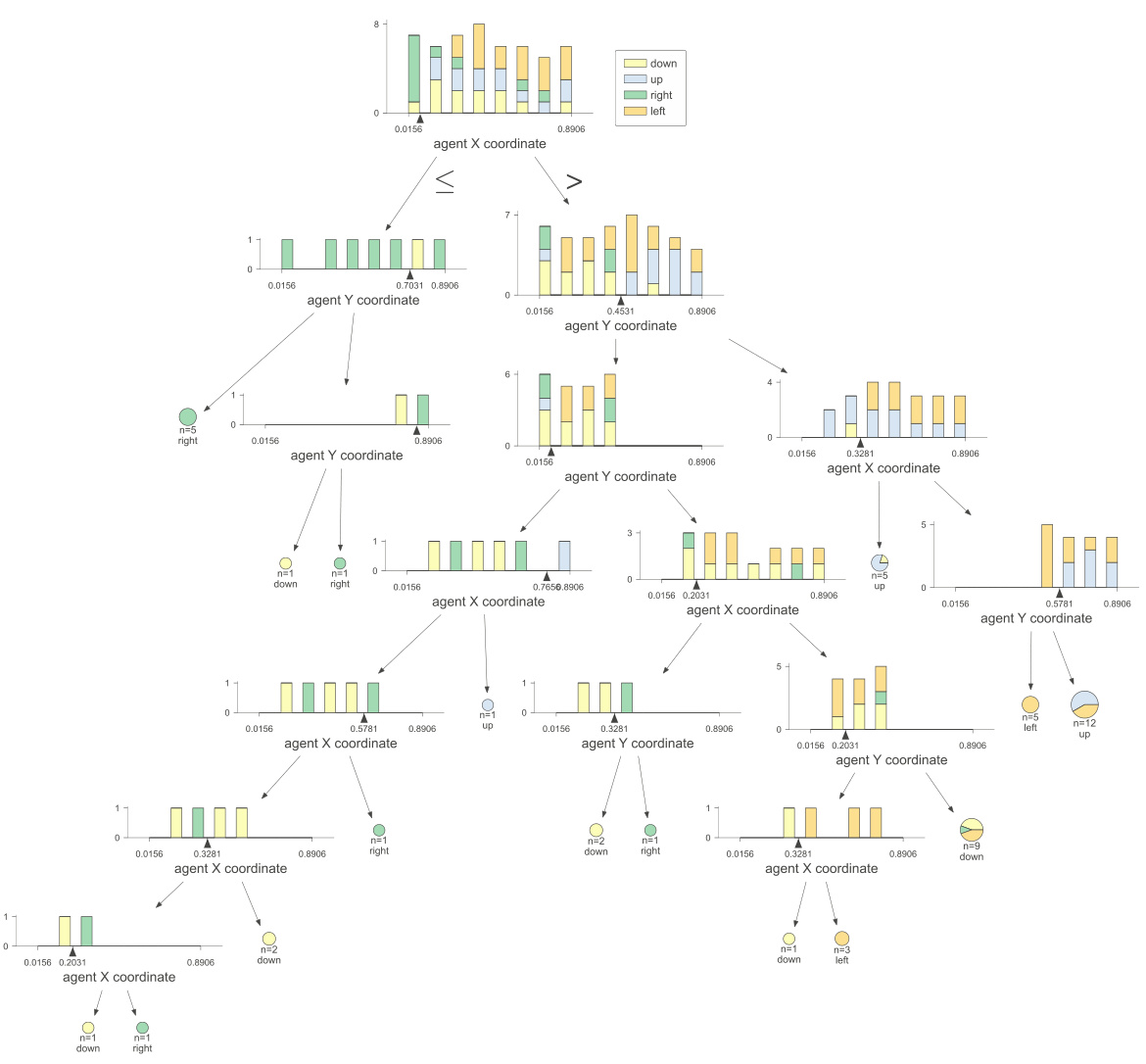

This figure shows the interpretability of the non-Euclidean clustering labels used in RGMDT. Subfigures (a) and (b) illustrate how agent positions during training correlate with these labels. Subfigures (c) and (d) show the relationship between agent actions and the clustering labels. The results indicate that the labels generated by the non-Euclidean clustering effectively capture relevant spatial and action information, making the resulting decision tree more interpretable.

This figure demonstrates the interpretability of the non-Euclidean clustering labels used in RGMDT. The top two subfigures (a) and (b) show the relationship between agent positions in the environment and the assigned cluster label. Agents closer to the higher reward target are more likely to be labeled ‘1’, while agents closer to the lower reward target tend to be labeled ‘2’. The bottom two subfigures (c) and (d) show the relationship between the cluster label and the action taken by the agents. The visualization reveals a clear mapping between labels and actions. For example, label ‘1’ strongly correlates with the ‘up’ action.

This figure shows the interpretability of the non-Euclidean clustering labels used in RGMDT. Subfigures (a) and (b) demonstrate the correlation between agent positions during training and the resulting cluster labels. Agents closer to the higher-reward target tend to be labeled ‘1’, while those near the lower-reward target are labeled ‘2’. Subfigures (c) and (d) illustrate the relationship between agent actions (‘down’, ‘up’, ‘right’, ’left’) and the cluster labels (‘0’, ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’). The heatmaps show the conditional probabilities of taking each action given a specific cluster label.

This figure shows the interpretability of the non-Euclidean clustering labels used in RGMDT. Subfigures (a) and (b) illustrate how agent positions during training correlate with clustering labels. Subfigures (c) and (d) show how the agents take actions conditioned on those labels. This demonstrates that the clustering labels are meaningful and reflect the agents’ behavior in the environment.

This figure shows the relationship between the return gap and the average cosine distance for different numbers of leaf nodes in a decision tree. The return gap represents the difference in performance between an optimal policy and the decision tree policy, while the average cosine distance measures the similarity of action-value vectors within the same cluster. As the number of leaf nodes increases, the average cosine distance decreases, indicating that the action-value vectors within each cluster are more similar. Consequently, the return gap also decreases, showing that the decision tree policy approaches the optimal policy’s performance.

This figure compares the performance of RGMDT against several baselines on multi-agent tasks with varying numbers of agents and leaf nodes. The results demonstrate that RGMDT significantly outperforms the baselines in terms of both speed and final reward, particularly in more challenging scenarios with limited leaf nodes.

This figure shows the relationship between the return gap and the average cosine distance using different numbers of leaf nodes in the decision tree. The return gap, representing the performance difference between the optimal policy and the learned decision tree, decreases as the average cosine distance decreases. This is consistent with the theoretical findings of the paper, demonstrating that using more leaf nodes reduces the return gap by improving the accuracy of the tree’s approximation of the optimal policy.

This figure shows the relationship between the return gap and the average cosine distance for different numbers of leaf nodes in a decision tree. The return gap, representing the difference in performance between an optimal policy and the decision tree policy, is plotted against the average cosine distance, a measure of the dissimilarity between action-value vectors within clusters. The figure demonstrates that as the number of leaf nodes (and thus the complexity of the tree) increases, the average cosine distance decreases, leading to a smaller return gap. This aligns with the theoretical findings in the paper, supporting the claim that RGMDT effectively minimizes the return gap.

More on tables

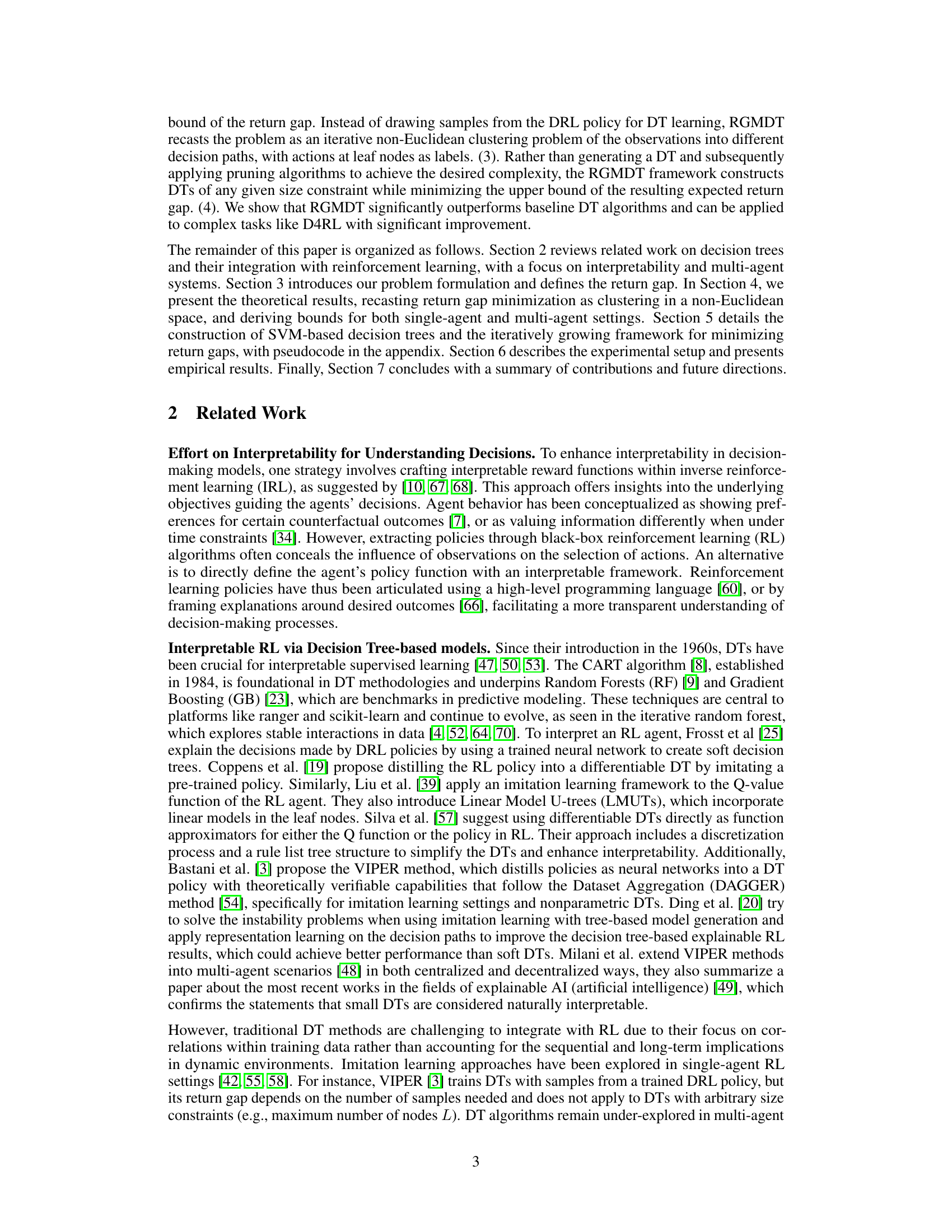

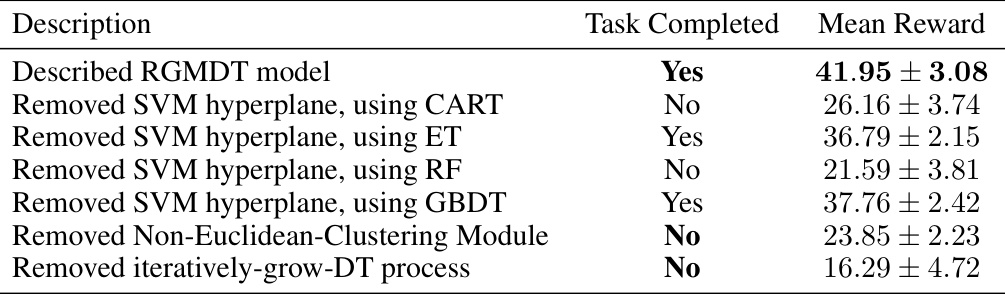

This table presents an ablation study on the RGMDT model, analyzing the impact of different components on its performance. The ‘Described RGMDT model’ row shows the performance of the complete model. Subsequent rows remove key components (SVM hyperplane, Non-Euclidean Clustering Module, iteratively-grow-DT process) one at a time, using different DT algorithms (CART, ET, RF, GBDT) where applicable. The results highlight the crucial roles of the SVM hyperplane, Non-Euclidean clustering, and the iteratively-grow-DT process in achieving the strong performance of the full RGMDT model.

This table compares the performance of RGMDT using non-Euclidean cosine distance with Euclidean and Manhattan distances under various noise levels. It demonstrates RGMDT’s robustness to noise and the superiority of the non-Euclidean approach.

Full paper#