↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Emergent communication, where AI agents learn to communicate to solve tasks, often produces opaque protocols. This research explores whether these protocols reflect meaningful communication, focusing on two common objectives: discrimination and reconstruction. Existing empirical results show that discrimination-based methods, while effective for task completion, can lead to counter-intuitive, almost random communication strategies. This raises crucial questions about the quality and interpretability of emergent communication.

This study introduces formal definitions of semantic consistency (messages should have similar meanings across different instances) and spatial meaningfulness (similar messages are close in the message space). Through theoretical analysis, the authors show that reconstruction-based objectives inherently encourage semantic consistency and spatial meaningfulness, while discrimination-based objectives do not. Experiments on two datasets validate the theoretical findings, demonstrating the superior quality of communication protocols induced by reconstruction objectives. This research thus offers a crucial framework for understanding and improving the quality and human-like properties of emergent communication.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is vital because it introduces novel definitions for semantic consistency and spatial meaningfulness in emergent communication, bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and empirical observations. It challenges existing assumptions about the optimization objectives in this field, opening new avenues for designing more human-like communication protocols and improving the interpretability of emergent languages.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure shows a schematic of the two main tasks used in the emergent communication experiments: reconstruction and discrimination. In the reconstruction task (a), the sender receives an input (e.g., a number ‘2’) and produces a message. The receiver then uses only the message to try to reconstruct the original input. The loss is the distance between the reconstructed input and the original input. In the discrimination task (b), the sender also produces a message from an input. The receiver receives the message and a set of candidate inputs, one of which is the original input. The receiver must then choose the original input among the candidate inputs. The loss in this task is negative log-likelihood, representing the probability of the receiver correctly identifying the original input.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the reconstruction and discrimination tasks. The discrimination receiver is given the candidates in addition to the message.

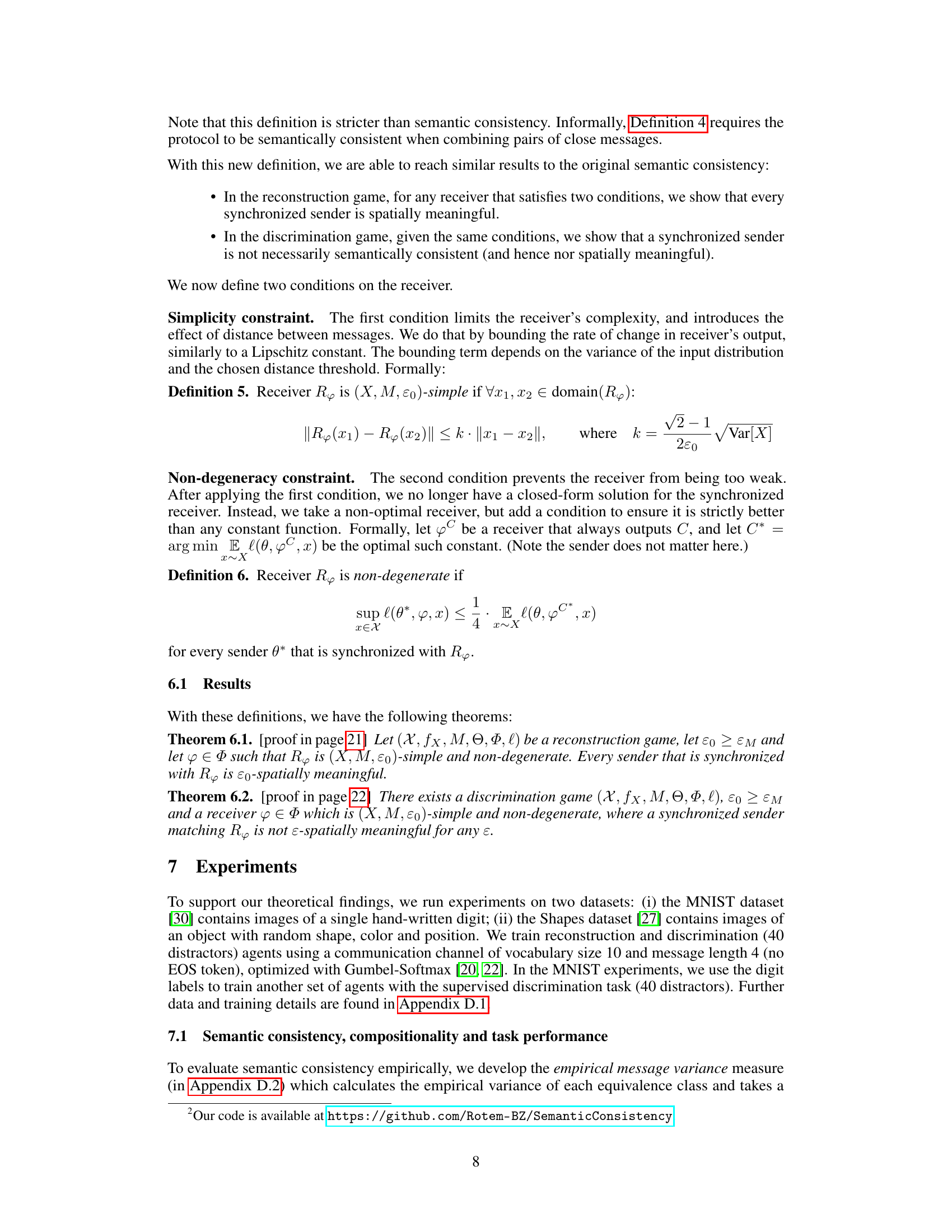

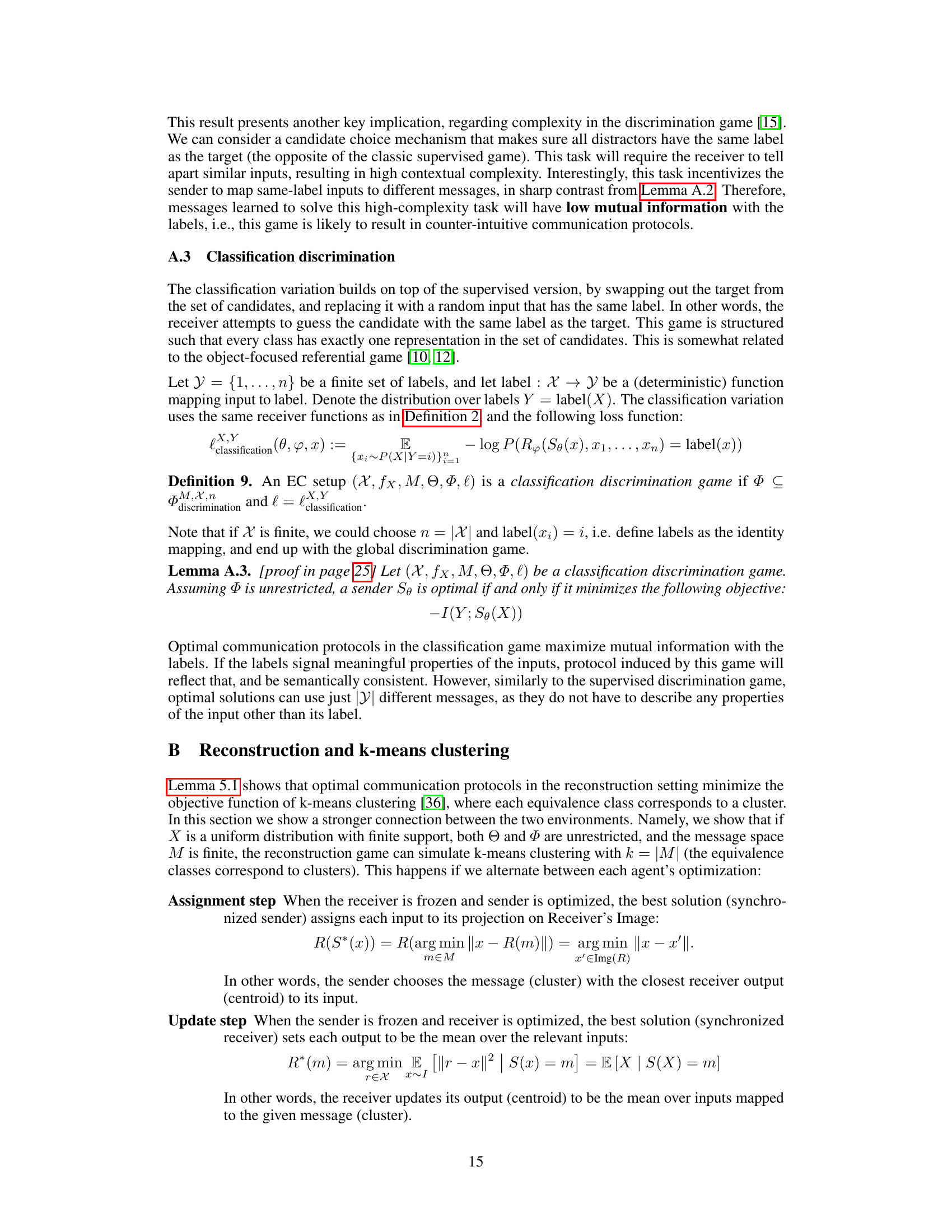

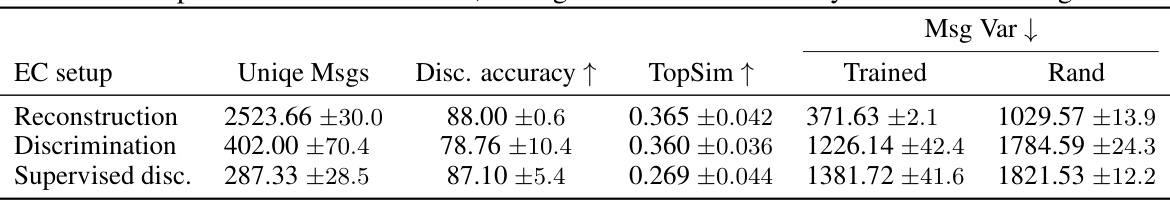

🔼 This table presents the empirical results obtained from experiments conducted on the Shapes dataset. Five different training runs were initialized randomly, and the results are averaged across these runs. The table shows the number of unique messages generated, the discrimination accuracy achieved (higher is better), the topographic similarity (TopSim) score (higher indicates more compositionality), and the message variance (lower is better, indicating more semantic consistency). The results are compared for both the reconstruction and discrimination tasks. A random baseline is also included (Rand) for comparison, showing the message variance for randomly generated messages to the same number of unique messages as the trained models.

read the caption

Table 1: Empirical results on Shapes, averaged over five randomly initialized training runs.

In-depth insights#

Emergent Comms#

Emergent communication (EC) studies how communication protocols arise in multi-agent systems without explicit instruction. The core idea is that agents, through interaction and shared goals, spontaneously develop ways to exchange information. Researchers explore different objective functions, such as reconstruction (where the receiver reconstructs the sender’s input) and discrimination (where the receiver identifies the correct input from a set of options), to analyze their impact on the resulting communication protocols. A key focus is understanding how the choice of objective influences the properties of the emergent language, including its semantic consistency (whether similar inputs are consistently mapped to the same messages) and compositionality (whether complex meanings can be built from simpler ones). This field is particularly interesting because of the potential to provide insights into the origins of human language and to design more effective communication systems for artificial agents. However, research has also shown that simple EC protocols can exhibit counter-intuitive behaviors, sometimes achieving high task performance despite lacking properties generally associated with meaningful communication. Therefore, a critical area of research is developing objective functions that promote more natural and interpretable communication.

Semantic Consistency#

The concept of “Semantic Consistency” in the context of emergent communication is crucial. It posits that messages should convey similar meanings across different instances. This is goal-agnostic, meaning it applies irrespective of the specific task the agents are trying to perform. The authors contrast this with the common EC objectives of discrimination and reconstruction. The core argument is that while discrimination tasks may not always produce semantically consistent protocols (as optimal solutions might involve arbitrary mappings between inputs and messages), reconstruction tasks intrinsically encourage semantic consistency. This is because the reconstruction objective necessitates that inputs mapped to the same message possess similar properties, directly addressing the core principle of semantic consistency. This is further reinforced by a stricter notion of spatial meaningfulness, which adds the consideration of distances between messages. Therefore, the research highlights a clear advantage for reconstruction-based communication goals, offering a more intuitive and natural pathway toward the development of human-like communication systems. Ultimately, this notion provides a valuable theoretical framework for evaluating and improving the design of emergent communication environments.

Spatial Meaning#

The concept of “Spatial Meaning” in the context of emergent communication explores how the geometric relationships between messages in a communication protocol relate to the meaning conveyed. This concept goes beyond simply considering whether messages are semantically consistent (i.e., if similar inputs map to the same message). Spatial meaningfulness emphasizes the importance of the distance between messages, arguing that similar messages should also have similar meanings, mirroring the structure of human language where related words or concepts are often lexically close. This addition improves upon the semantic consistency definition by acknowledging the spatial aspect, which the previous definition lacked. This nuance is crucial because while a protocol might achieve semantic consistency, it could still map similar messages to vastly different semantic regions, failing to capture the intuitive spatial organization of meaning found in human language. Therefore, spatial meaningfulness provides a more stringent, insightful measure for evaluating the quality of emergent communication protocols, potentially leading to the development of more human-like systems capable of nuanced communication.

Experimental Setup#

A well-defined experimental setup is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It needs to describe the datasets used, including their characteristics and preprocessing steps, ensuring reproducibility. The choice of datasets is particularly important, as it dictates the generalizability of the findings. The paper should detail the algorithms and models employed, their hyperparameters and the rationale behind their selection. The training process needs to be thoroughly explained, including the optimization methods, evaluation metrics, and any specific training techniques like data augmentation or regularization. The paper must also specify the hardware and software environments, providing information on the computational resources used and the code versions. This level of detail guarantees that other researchers can reproduce the experiments, confirming the robustness and validity of the results presented. In addition to clarity and completeness of description, a robust setup anticipates potential sources of bias and addresses them appropriately, ensuring the reliability of the study.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several avenues. Expanding the theoretical framework to account for realistic agent limitations (e.g., limited capacity, imperfect optimization) is crucial. Investigating alternative discrimination game formulations, such as those using latent similarity, could reveal if semantic consistency emerges under different conditions. Empirically, testing the proposed metrics on more diverse datasets and across various communication tasks will further validate the findings. A promising direction is to incorporate spatial meaningfulness more directly into the objective function during training. Furthermore, studying how different communication objectives influence emergent language properties beyond semantic consistency (e.g., compositionality, efficiency) is key to bridging the gap between emergent communication and natural language. Finally, examining how different aspects of the environment (e.g., input distribution, channel capacity) influence the emergent communication protocol would provide deeper insights into the mechanisms driving the evolution of communication.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows a schematic representation of the notation used in the paper for the emergent communication setup. It outlines the input distribution, message space, agent parameters (sender and receiver), and the objective function used in the training process. The arrow indicates the training process that leads to optimal solutions for the sender and receiver parameters.

read the caption

Figure 2: Notation for the emergent communication (EC) setup.

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of semantic consistency in emergent communication. Panel (a) shows the input space with three distinct types of objects (triangles, circles, and squares) visually separated into clusters. Panel (b) depicts a semantically consistent mapping, where the objects mapped to the same message (m1, m2, m3) share similar properties and are clustered together. In contrast, panel (c) shows a semantically inconsistent mapping, where objects with dissimilar properties are grouped together under the same message, thus lacking semantic consistency.

read the caption

Figure 3: A message describes a set of inputs. Note: the shapes and colors are not part of the input.

🔼 This figure compares the average message purity achieved by trained models against random baselines across three different experimental setups: reconstruction, discrimination, and supervised discrimination. Message purity measures the percentage of images within an equivalence class (set of inputs mapped to the same message) that share the majority attribute value. Higher purity suggests better semantic consistency and more meaningful communication. The results show that the reconstruction setup achieves significantly higher purity than the other two setups, indicating its stronger capacity for encoding meaningful information in generated messages.

read the caption

Figure 4: Average message purity, comparing trained models to random baselines.

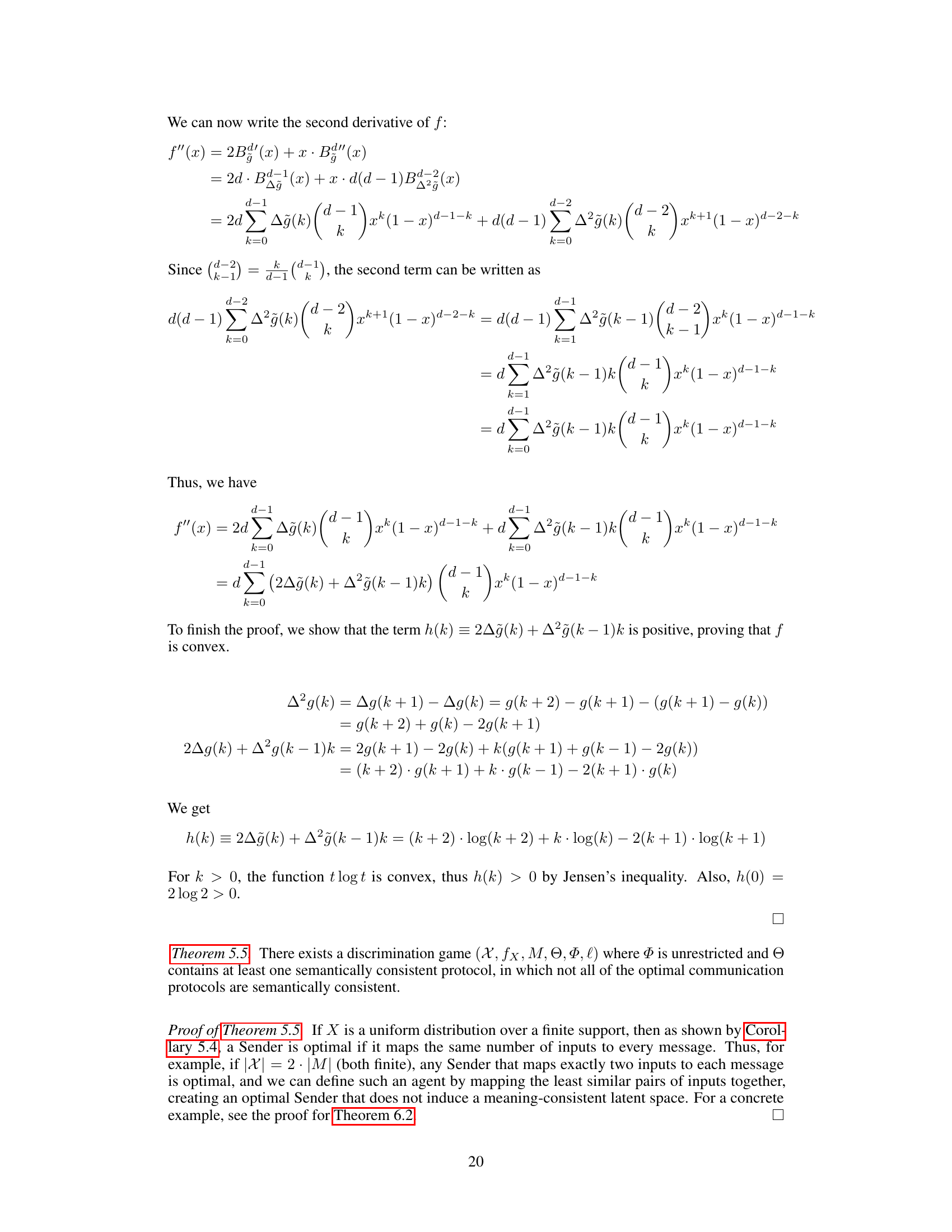

🔼 This figure shows the architectures of the encoder and decoder used in the Shapes dataset experiments. The encoder takes an image as input and outputs a latent vector, while the decoder takes a latent vector as input and outputs a reconstructed image. Both encoder and decoder consist of multiple convolutional and transposed convolutional layers, batch normalization layers, and LeakyReLU activation functions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Encoder and Decoder architectures used on Shapes.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main tasks in emergent communication: reconstruction and discrimination. The reconstruction task involves the sender generating a message based on an input, and the receiver reconstructing the original input from the message. The discrimination task is similar, but the receiver also receives a set of candidate inputs and must choose the correct one based on the message. The figure visually depicts these processes, highlighting the differences between the two tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the reconstruction and discrimination tasks. The discrimination receiver is given the candidates in addition to the message.

🔼 This figure shows examples of the reconstruction and discrimination tasks performed on the Shapes dataset. The top half displays reconstruction results. For each example, the original image is shown alongside the image reconstructed by the receiver based solely on the message generated by the sender. The bottom half shows the discrimination task, where the receiver selects the correct image from a set of candidates. For each example, the input image is shown alongside the candidates. The receiver’s prediction and associated score are also provided.

read the caption

Figure 7: Reconstruction (top) and discrimination (bottom) examples on Shapes

🔼 This figure shows examples of the reconstruction and discrimination tasks on the MNIST dataset. The top row displays the original MNIST digit image alongside the reconstructed image generated by the model from a message. The bottom row shows the input digit image used for generating a message and the scores the model produces for each of the presented candidates, highlighting how well the model identifies the original input digit image among other candidates.

read the caption

Figure 8: Reconstruction (top) and discrimination (bottom) examples on MNIST

🔼 This figure shows the purity of messages for different attributes (color, shape, and maximum purity across all attributes) in reconstruction and discrimination games. The results show that the reconstruction game generally produces higher purity, indicating that messages are more semantically consistent and informative in this setting, compared to the discrimination game.

read the caption

Figure 9: Message purity per attribute and game type.

More on tables

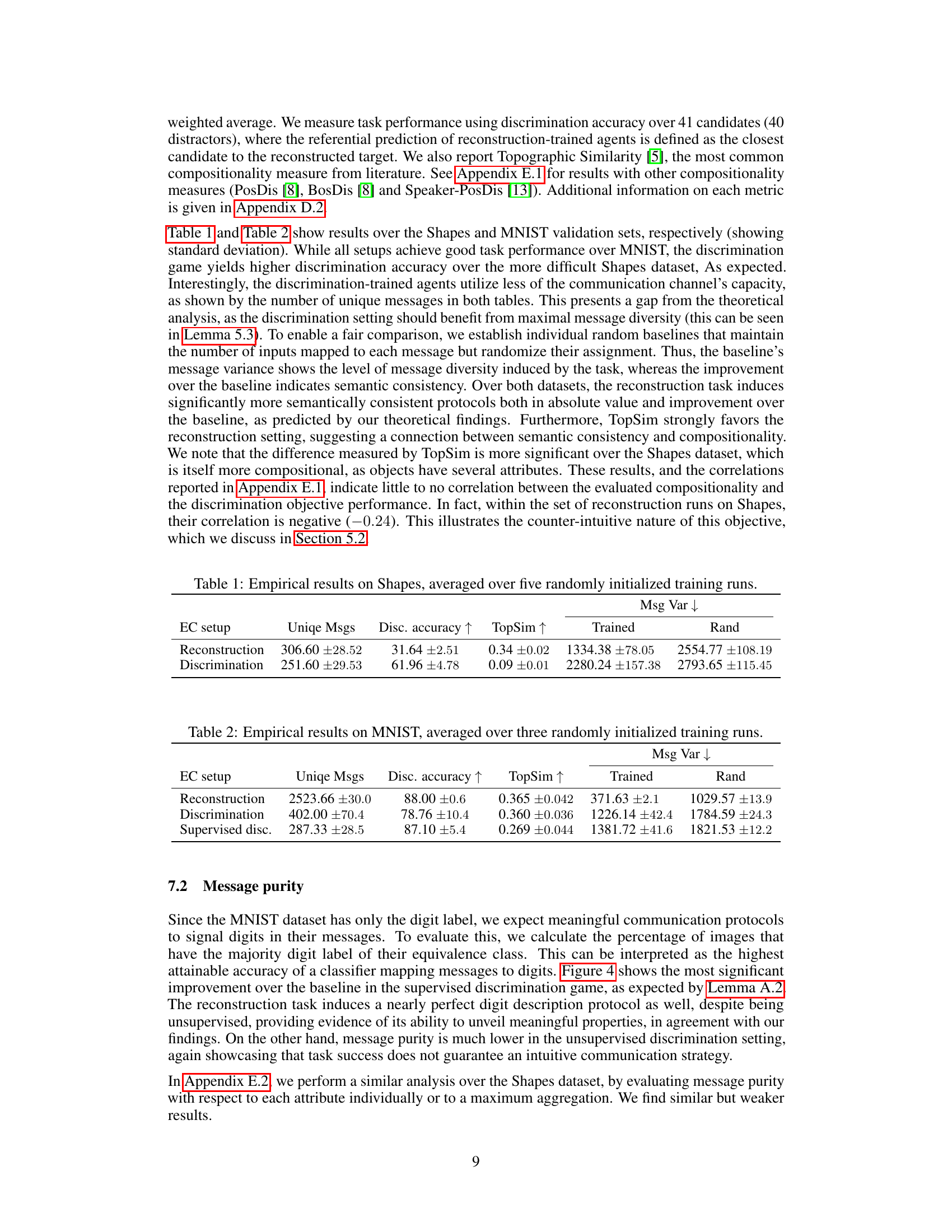

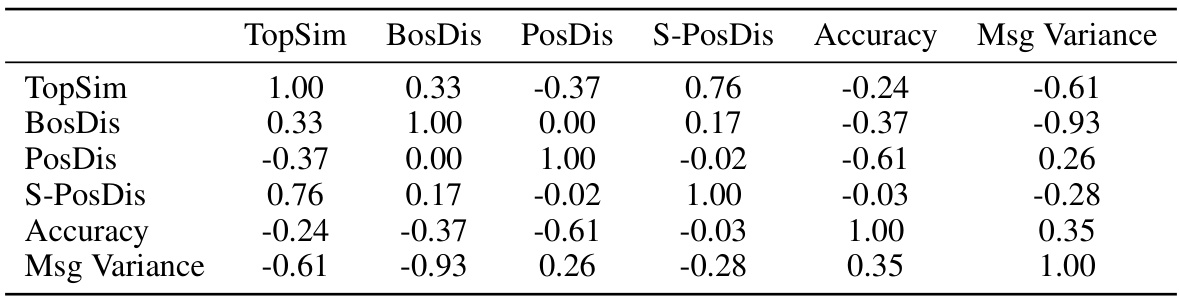

🔼 This table presents the empirical results on the MNIST dataset. It shows the performance of three different emergent communication setups (Reconstruction, Discrimination, and Supervised Discrimination) across multiple metrics. These metrics include the number of unique messages used, discrimination accuracy, topographic similarity (TopSim), and message variance. The results are averaged over three separate training runs, each initialized randomly, and error bars (standard deviation) are provided to indicate variability. The ‘Trained’ column shows the results for models trained on the full dataset, whereas the ‘Rand’ column represents a baseline established by randomizing message assignment while keeping the number of inputs per message constant.

read the caption

Table 2: Empirical results on MNIST, averaged over three randomly initialized training runs.

🔼 This table presents the empirical results obtained from experiments conducted on the Shapes dataset. Five different training runs were initialized randomly, and the results were averaged. The table shows the number of unique messages generated, the discrimination accuracy (higher is better), the TopSim score (a measure of compositionality, higher is better), and the message variance (lower is better, indicating more semantic consistency). Results are shown for both the reconstruction and discrimination tasks, providing a comparison between the two common objective functions used in emergent communication research.

read the caption

Table 1: Empirical results on Shapes, averaged over five randomly initialized training runs.

🔼 This table presents the empirical results obtained using various compositionality measures (TopSim, BosDis, PosDis, and S-PosDis) alongside discrimination accuracy and message variance for both reconstruction and discrimination game settings. The results are averaged over five (Shapes) or three (MNIST) independent training runs. The standard deviations are included. It aims to show the relationship between different compositionality measures, performance on the discrimination task, and the semantic consistency captured by message variance.

read the caption

Table 3: Empirical results with compositionality measures from literature.

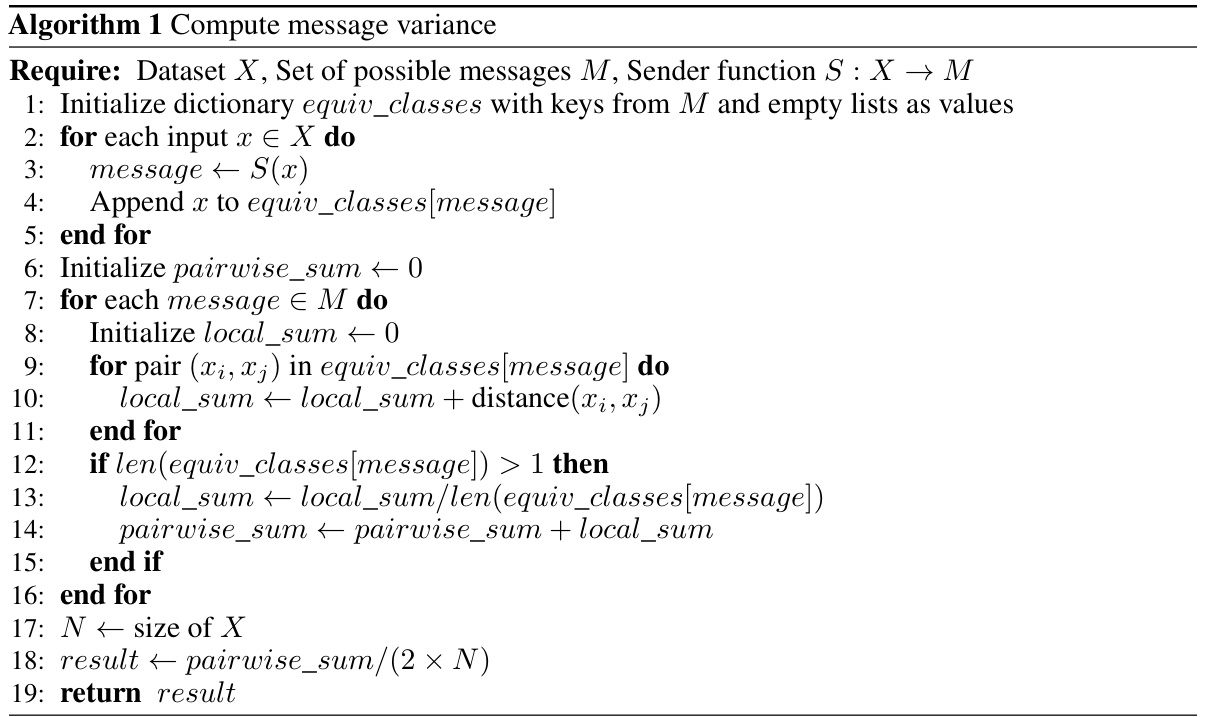

🔼 This table presents the correlation matrices for six different metrics: TopSim, BosDis, PosDis, S-PosDis, Accuracy, and Msg Variance. The correlations are calculated for three different groups of data: all data, reconstruction data only, and discrimination data only. This allows for an analysis of how the relationships between these metrics change depending on the experimental setup (reconstruction vs. discrimination). High positive correlations suggest that two metrics tend to move together, whereas high negative correlations indicate an inverse relationship.

read the caption

Table 4: Correlation Matrices for All Data, Reconstruction, and Discrimination Groups

🔼 This table presents the correlation matrices for the compositionality and semantic consistency measures against accuracy and message variance. The correlations are shown for three different sets of results: all data, reconstruction results only, and discrimination results only. The purpose is to investigate the relationships between these metrics and understand how these relationships differ across the two primary experimental setups.

read the caption

Table 4: Correlation Matrices for All Data, Reconstruction, and Discrimination Groups

🔼 This table presents correlation matrices for different metrics calculated from experimental results. The correlations are shown for the entire dataset, and also separately for reconstruction and discrimination game results. Metrics include TopSim (topographic similarity), BosDis (bag-of-symbols disentanglement), PosDis (positional disentanglement), S-PosDis (speaker-centered topographic similarity), accuracy, and message variance. The table helps to understand the relationships between these different measures and how they relate to the different experimental conditions.

read the caption

Table 4: Correlation Matrices for All Data, Reconstruction, and Discrimination Groups

🔼 The table presents the purity results for three different purity measures (Purity-Max, Purity-Color, and Purity-Shape) for both reconstruction and discrimination game settings, along with their corresponding random baselines. Purity measures how well the messages convey information about specific attributes (color and shape). Higher purity values indicate that the messages contain more semantic information for the corresponding attribute.

read the caption

Table 5: Purity measures compared with random baselines.

🔼 This table presents empirical results obtained from experiments conducted on the Shapes dataset. Five different training runs were initialized randomly, and the results are averaged across those runs. The table shows the number of unique messages used, the discrimination accuracy (a measure of performance in the discrimination task), the topographic similarity (TopSim, a measure of compositionality), and the message variance (a measure of semantic consistency). Reconstruction and discrimination EC setups are compared, showing the performance metrics for each.

read the caption

Table 6: Empirical results on Shapes, averaged over five randomly initialized training runs.

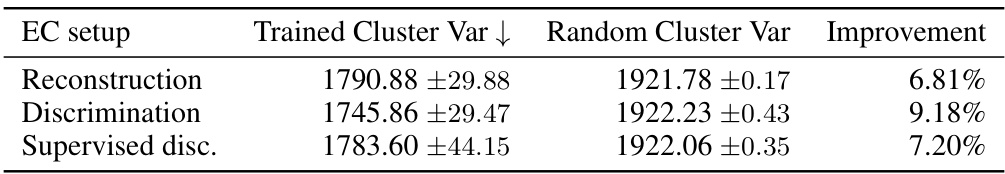

🔼 This table presents the results of the cluster variance experiment on the MNIST dataset. It shows the trained cluster variance, random cluster variance, and the improvement achieved by the trained models over the random baseline for three different experimental setups: Reconstruction, Discrimination, and Supervised discrimination. The lower the cluster variance, the more spatially meaningful the resulting messages. The improvement percentage indicates how much better the trained model performs compared to a random assignment of messages.

read the caption

Table 7: Cluster Variance on MNIST.

Full paper#