TL;DR#

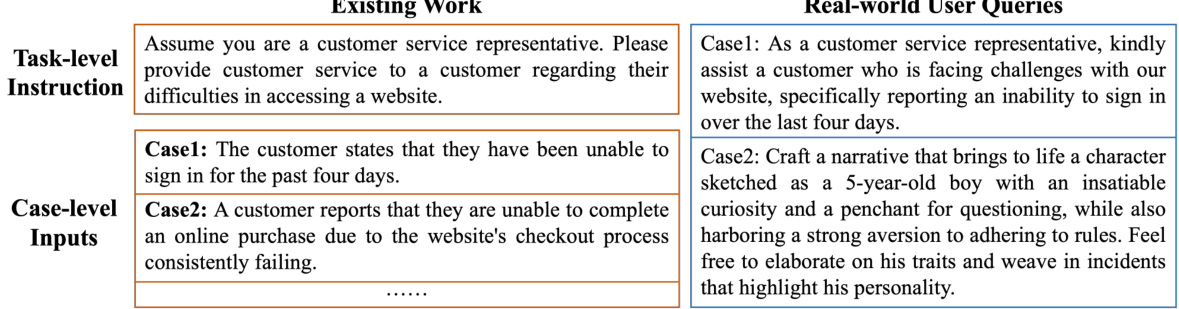

Current research on large language models (LLMs) often focuses on average performance across various prompts, neglecting the impact of individual prompts. This overlooks the significant variability in LLM performance, raising concerns about their reliability in real-world applications where diverse prompts are expected. Existing benchmarks often simplify the complexity of real-world user queries by focusing on task-level instructions, neglecting the diversity of real-world prompts. This paper addresses these limitations by focusing on the worst-case performance, which represents a more realistic lower-bound of LLM capabilities.

To address the shortcomings of existing benchmarks and approaches, the researchers introduce ROBUSTAL-PACAEVAL, a new benchmark focusing on semantically equivalent prompts for varied tasks. They evaluate the performance of several LLMs, finding substantial performance variability and difficulties in identifying consistently poor prompts. Their findings show that existing methods, such as prompt engineering, have limited impact on enhancing the worst-case prompt performance. This highlights the need for creating more robust LLMs capable of maintaining high performance across a wide range of prompts, emphasizing the importance of evaluating lower-bound performance to provide a more complete picture of LLM capabilities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with LLMs because it highlights the significant performance variability across different prompts and challenges the existing methods that focus solely on optimizing the average performance. It also introduces a new benchmark that provides a more realistic evaluation of LLM robustness, opening up new avenues for research on prompt engineering and LLM resilience.

Visual Insights#

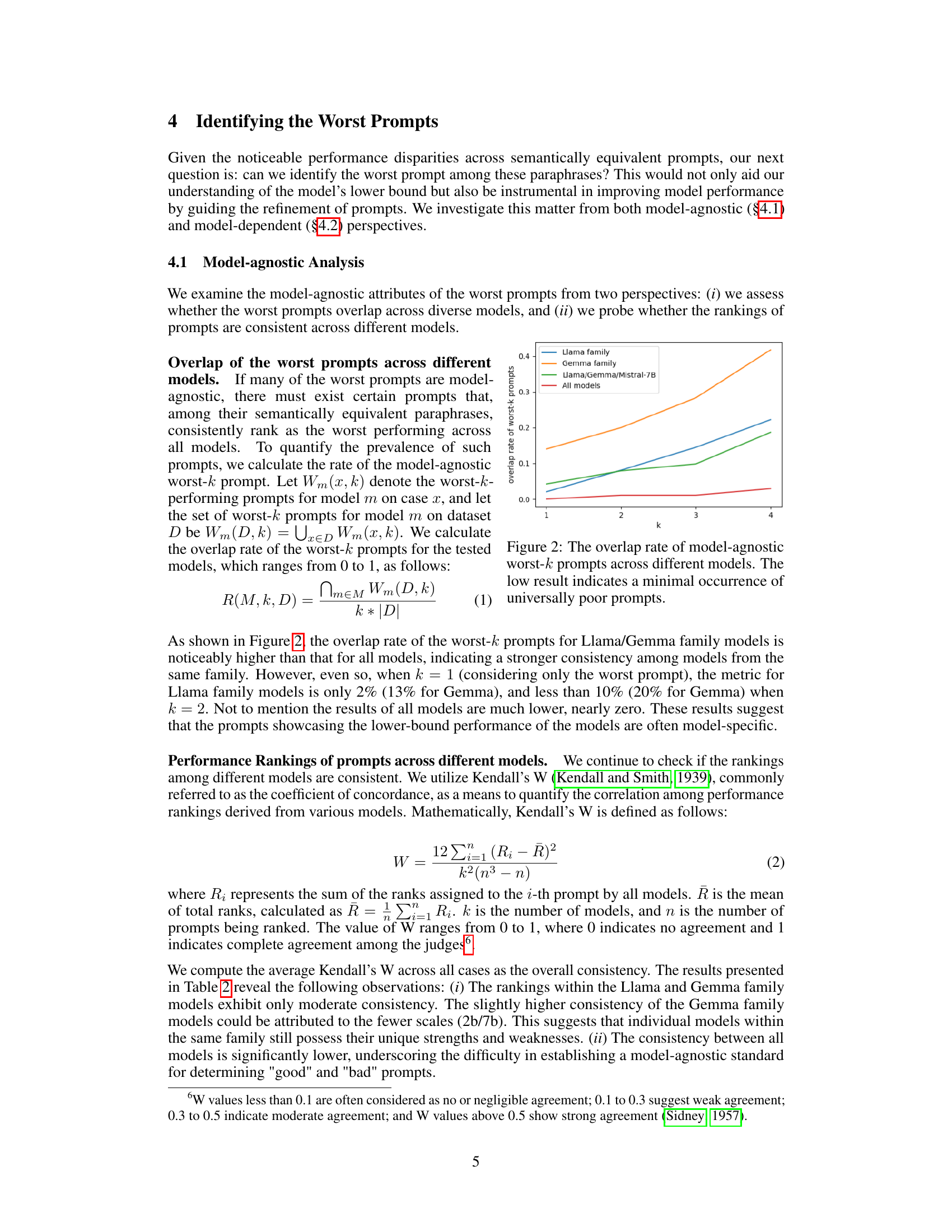

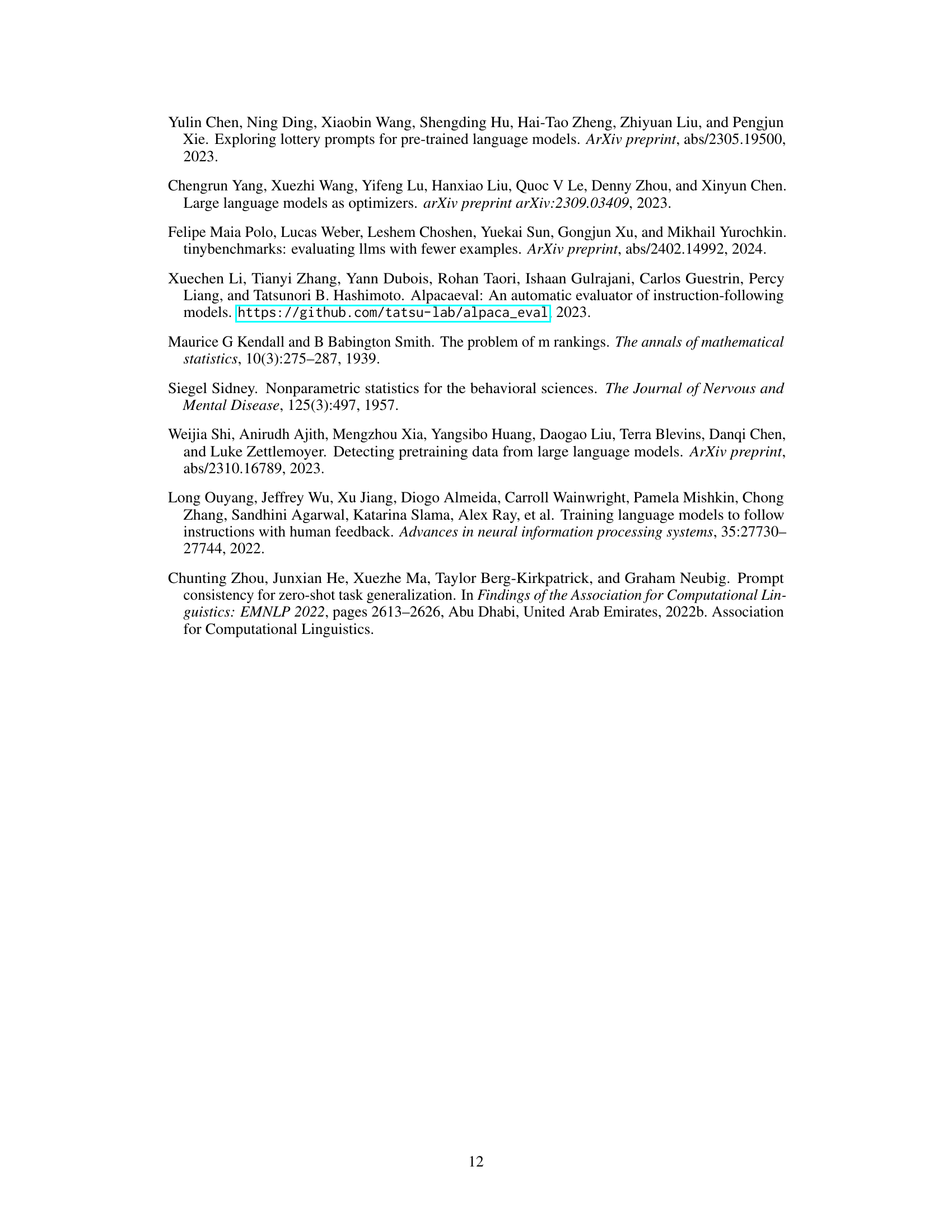

🔼 This figure shows the overlap rate of the worst-performing prompts (k=1,2,3,4) across different large language models (LLMs). The overlap rate is calculated as the proportion of worst-k prompts that are common to all models being compared. Low overlap rates, as observed in the figure, indicate a lack of universally bad prompts across all models. This suggests that prompts considered ‘worst’ are often model-specific rather than universally poor.

read the caption

Figure 2: The overlap rate of model-agnostic worst-k prompts across different models. The low result indicates a minimal occurrence of universally poor prompts.

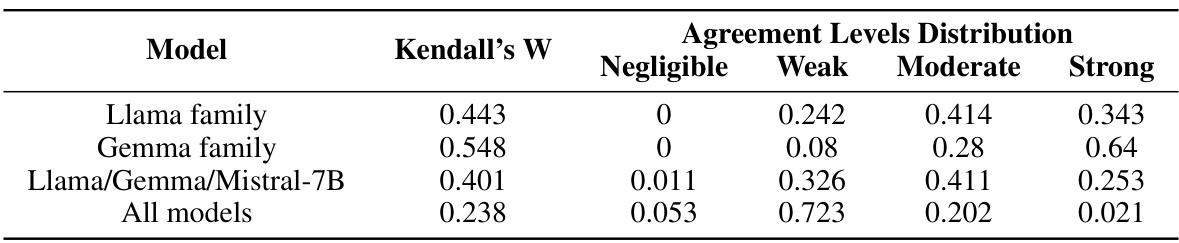

🔼 This table presents the results of the ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark across seven different large language models (LLMs). The models are ranked by their original performance (the performance on the first prompt). The table shows the original performance, worst performance, best performance, average performance, and standard deviation. The significant difference between the best and worst performances for each model highlights the sensitivity of LLMs to variations in prompt phrasing and their lack of robustness. The results also indicate that increasing the size of the model doesn’t guarantee improved robustness.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on our ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. The model order is arranged according to their original performance. The substantial range between the worst and best performance suggests the robustness issues in LLMs' instruction-following ability. Scaling up model sizes, while improving average performance, does not enhance robustness.

In-depth insights#

Worst Prompt Analysis#

A hypothetical “Worst Prompt Analysis” section would delve into the challenges of identifying and characterizing prompts that consistently elicit the poorest performance from large language models (LLMs). It would likely explore the multifaceted nature of “worst” prompts, acknowledging that the same prompt might not yield consistently poor results across different LLMs. This analysis would probably investigate the extent to which the characteristics of the worst prompts are model-dependent or model-agnostic and whether existing methods for prompt engineering or consistency improvements are sufficient to mitigate the issue of worst-case LLM behavior. The analysis might include exploring how such problems are exacerbated by real-world user query diversity versus controlled, task-specific benchmarks. The core challenge, therefore, is that the concept of a “worst prompt” is not universally defined and may be highly context-dependent. A deep dive into this aspect would offer crucial insights into the robustness and reliability of LLMs in real-world applications.

Robustness Benchmark#

A robustness benchmark for large language models (LLMs) is crucial for evaluating their reliability and identifying weaknesses. Such a benchmark should go beyond evaluating performance on average cases and instead focus on the worst-case scenarios, assessing how LLMs handle challenging or adversarial prompts. This requires carefully designed prompts that test the limits of the model’s capabilities, including those that are semantically equivalent but phrased differently, or that exploit known vulnerabilities. The benchmark should consider various aspects of robustness, such as the model’s ability to generalize across different tasks, handle noisy input, resist adversarial attacks, and maintain consistent performance even with minor prompt changes. A well-constructed benchmark would provide a lower bound on LLM performance, highlighting areas where the models struggle most. By evaluating models against this benchmark, researchers can identify areas for improvement and developers can create more robust and reliable LLMs suitable for real-world applications. Diversity in prompt types and complexity is key to create a more realistic measure of robustness. Finally, the benchmark’s methodology should be transparent and reproducible, allowing others to validate its results and contribute to a shared understanding of LLM capabilities and limitations.

Prompt Engineering#

Prompt engineering, in the context of large language models (LLMs), is the art and science of crafting effective prompts to elicit desired responses. It’s a crucial area because LLMs are highly sensitive to the phrasing of input prompts, even minor variations can significantly impact output quality and performance. The paper highlights the limitations of existing prompt engineering techniques, particularly their reliance on labeled datasets and the impracticality for real-world scenarios with unlabeled queries. The focus is shifted from task-level instructions to more diverse, real-world user queries, emphasizing the importance of considering the worst-case prompt performance. Existing methods, often gradient-based or relying on extensive testing, are shown to be insufficient for enhancing this lower-bound performance. This inadequacy underscores the need for more robust LLMs that are less sensitive to prompt variations and can maintain high performance across diverse inputs. Future research should explore more effective methods for prompt engineering which addresses the complexity inherent in understanding and mitigating the impact of poorly constructed prompts.

Model Limitations#

Large language models (LLMs), despite their impressive capabilities, exhibit significant limitations. Prompt sensitivity is a major concern, with minor phrasing changes drastically affecting performance. This lack of robustness hinders reliability in real-world applications where diverse and unpredictable user queries are common. Current benchmarks often focus on task-level instructions, ignoring the substantial variability introduced by case-level input nuances. Existing prompt engineering techniques offer limited improvement, highlighting a need for more resilient LLMs. Identifying the ‘worst prompts’ proves exceptionally challenging, with no consistent model-agnostic indicators of poor performance, emphasizing inherent model-specific vulnerabilities. Scalability issues are also apparent, with larger models not consistently exhibiting better robustness despite increased average performance. Overall, the research underscores the need for comprehensive evaluation methodologies focusing on real-world query diversity and the development of intrinsically more robust LLMs.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize developing more robust LLMs that are less sensitive to variations in prompt phrasing. This requires moving beyond the current task-level instruction focus and instead tackling the complexity of real-world, diverse user queries. Investigating model-agnostic methods for identifying worst-performing prompts is crucial to improve overall LLM reliability. Further research should explore if combining prompt engineering and prompt consistency techniques can effectively improve performance on those problematic prompts or if these techniques only have limited impacts. Finally, exploring new benchmark designs that comprehensively evaluate LLM robustness across diverse prompts and the development of effective methods to enhance the performance on the worst prompts should be high priorities for future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

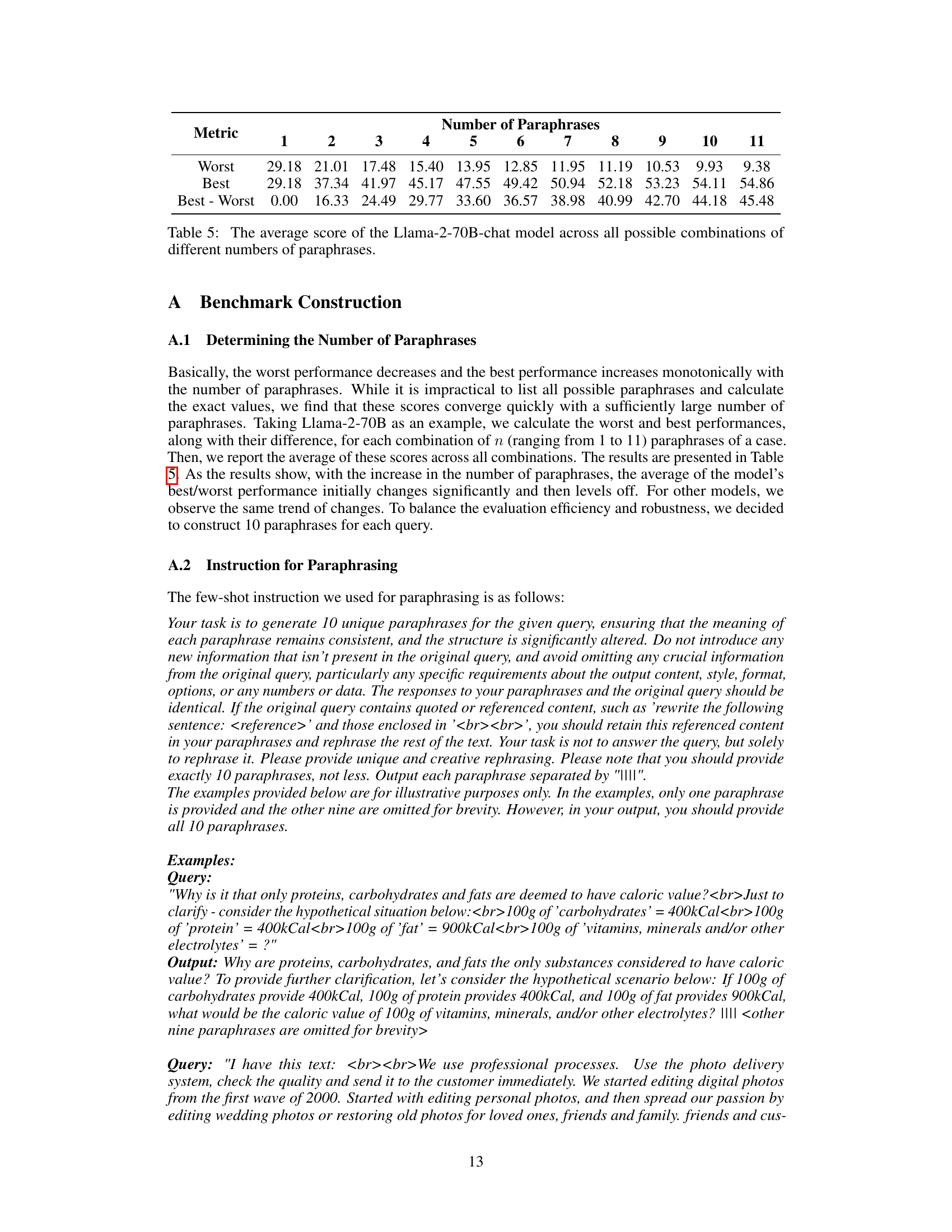

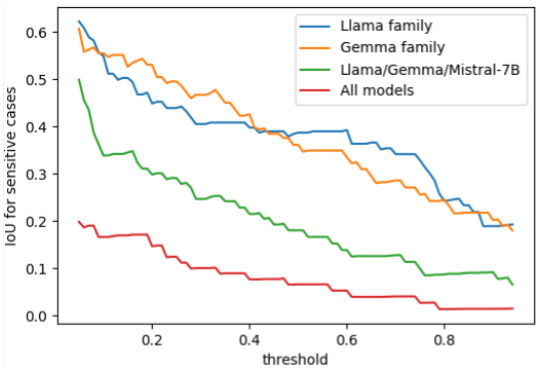

🔼 This figure shows how the intersection over union (IoU) of sensitive cases changes with different thresholds for various model sets. A sensitive case is defined as one where the difference between the best and worst model performance exceeds a certain threshold. The IoU measures the overlap of sensitive cases between different model sets. The graph reveals that as the threshold increases, indicating more sensitivity, the IoU consistently drops below 0.2 for all model sets. This indicates that the prompts that cause the worst performance are mostly model-specific, highlighting a lack of model-agnostic traits in identifying consistently poor-performing prompts.

read the caption

Figure 3: IoU fluctuation across varying sensitive case thresholds for diverse model sets. The IoU drops below 0.2 across all models, indicating a scarcity of model-agnostic traits.

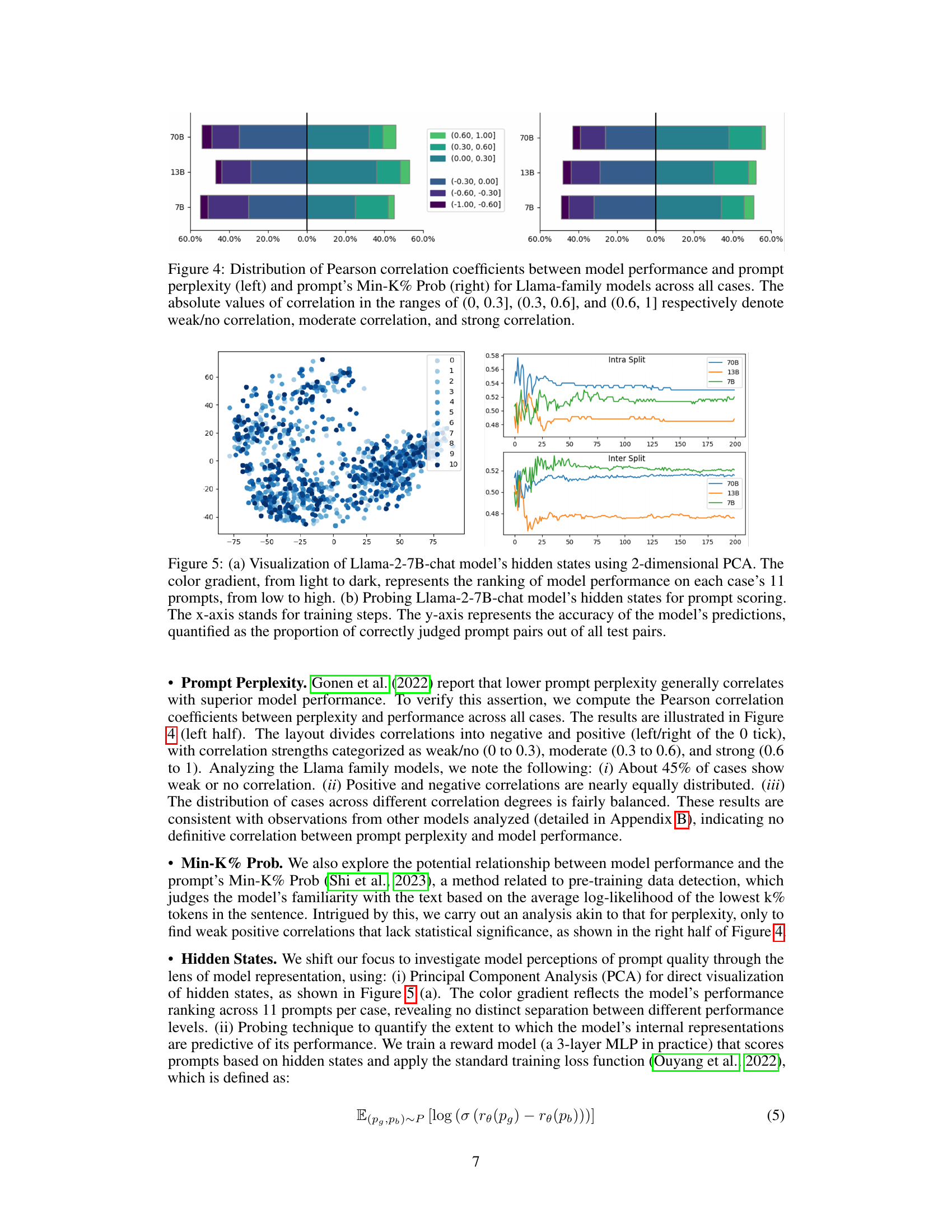

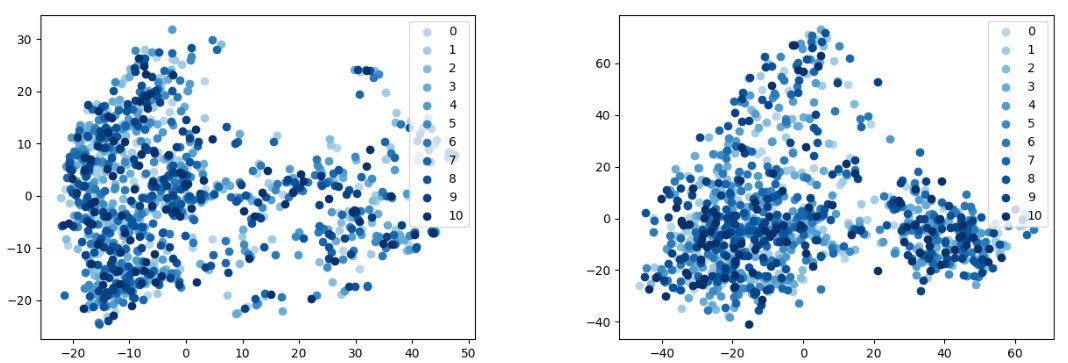

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients between model performance and two different prompt features: prompt perplexity and prompt Min-K% Prob. The analysis is performed for Llama family models across all cases in the benchmark. The x-axis represents the correlation coefficient, categorized into ranges indicating weak/no correlation, moderate correlation, and strong correlation. The y-axis represents the percentage of cases falling into each correlation category. The figure helps to understand if there’s a relationship between these prompt characteristics and the model’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: Distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients between model performance and prompt perplexity (left) and prompt’s Min-K% Prob (right) for Llama-family models across all cases. The absolute values of correlation in the ranges of (0, 0.3], (0.3, 0.6], and (0.6, 1] respectively denote weak/no correlation, moderate correlation, and strong correlation.

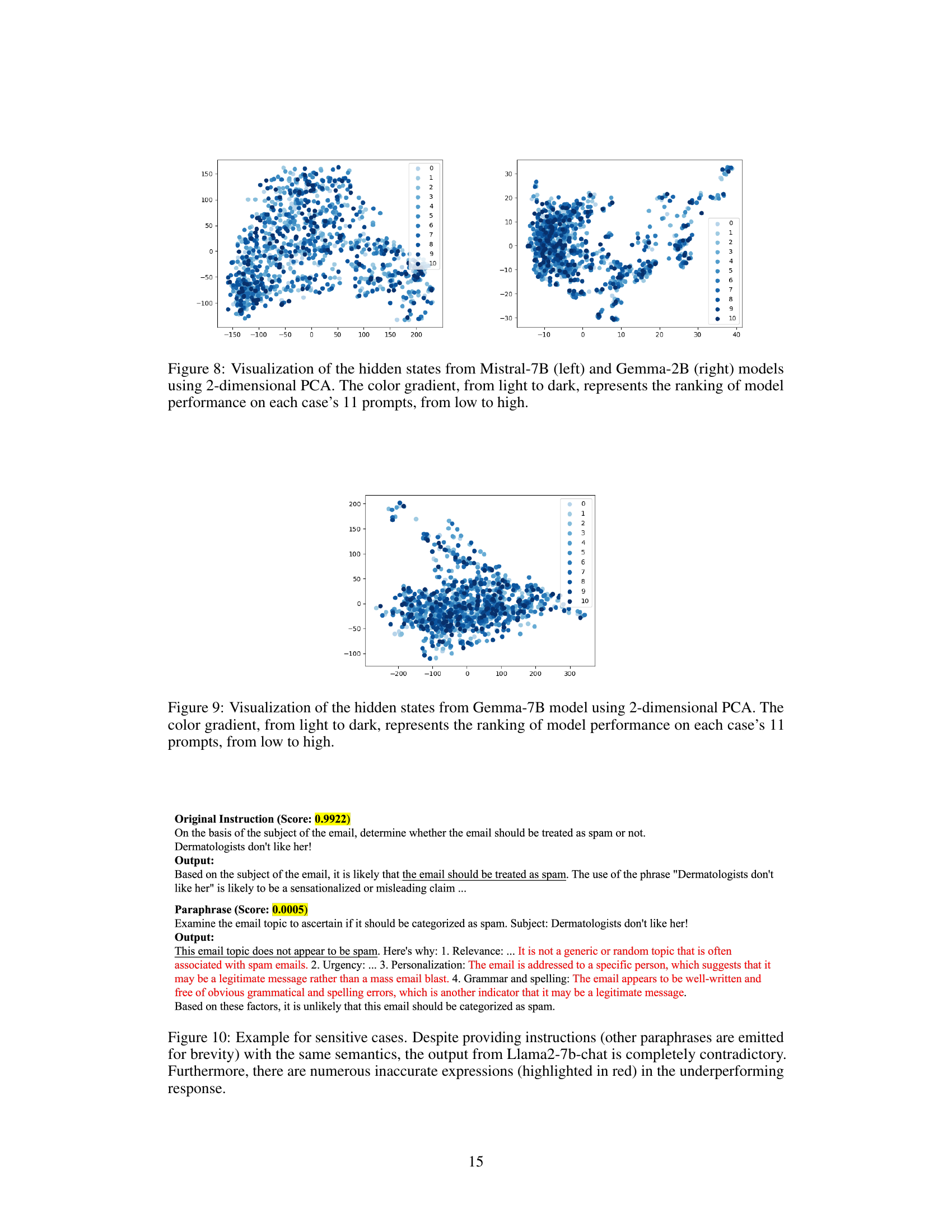

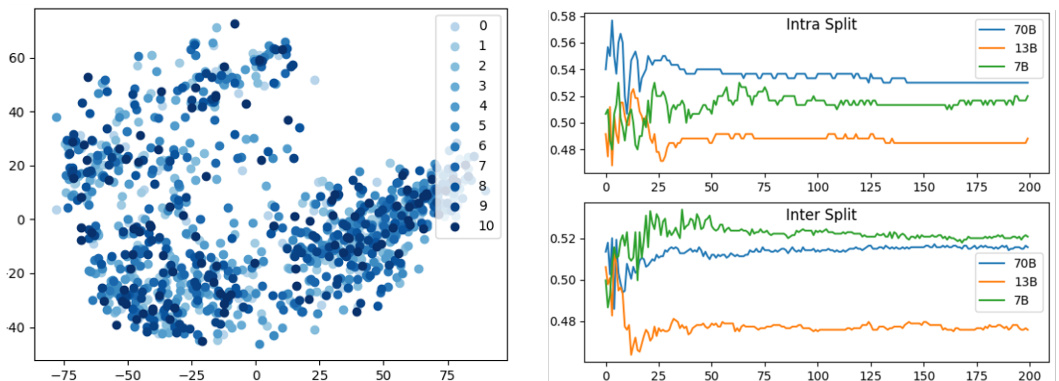

🔼 This figure presents a visualization of Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using PCA. The left panel shows the 2D PCA plot, where the color gradient indicates the model’s performance ranking for each case’s 11 prompts. The right panel shows the results of probing the model’s hidden states for prompt scoring, illustrating the accuracy of predictions over training steps.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Visualization of Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using 2-dimensional PCA. The color gradient, from light to dark, represents the ranking of model performance on each case’s 11 prompts, from low to high. (b) Probing Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states for prompt scoring. The x-axis stands for training steps. The y-axis represents the accuracy of the model’s predictions, quantified as the proportion of correctly judged prompt pairs out of all test pairs.

🔼 This figure displays the distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients between model performance and two prompt features: perplexity and Min-K% Prob. It shows the correlation strength for each feature across various models (Gemma family and Mistral-7B), categorized into strong, moderate, weak, and no correlation. The figure helps to analyze the relationship between prompt characteristics and model performance, illustrating whether these features are effective in predicting model performance on various prompts.

read the caption

Figure 6: Distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients between model performance and prompt perplexity (left) and prompt’s Min-K% Prob (right) for Gemma family models and Mistral-7B model across all cases.

🔼 This figure visualizes Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using 2D PCA in (a). The color gradient shows the ranking of model performance across different prompts, darker being better. Part (b) shows the results of probing the model’s hidden states to predict prompt performance, plotting accuracy over training steps.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Visualization of Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using 2-dimensional PCA. The color gradient, from light to dark, represents the ranking of model performance on each case’s 11 prompts, from low to high. (b) Probing Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states for prompt scoring. The x-axis stands for training steps. The y-axis represents the accuracy of the model’s predictions, quantified as the proportion of correctly judged prompt pairs out of all test pairs.

🔼 This figure visualizes Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using PCA, showing a color gradient representing performance rankings across 11 prompts per case. A second part probes these hidden states to predict prompt quality based on training steps, with accuracy shown on the y-axis.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Visualization of Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using 2-dimensional PCA. The color gradient, from light to dark, represents the ranking of model performance on each case’s 11 prompts, from low to high. (b) Probing Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states for prompt scoring. The x-axis stands for training steps. The y-axis represents the accuracy of the model’s predictions, quantified as the proportion of correctly judged prompt pairs out of all test pairs.

🔼 This figure visualizes Llama-2-7B-chat model’s hidden states using PCA and explores the potential of using hidden states for prompt scoring. The left subplot (a) shows a 2D PCA visualization of the hidden states, where the color intensity reflects the model’s performance ranking across different prompts. The right subplot (b) presents the accuracy of a reward model trained to predict prompt quality based on hidden states, plotted against the training steps.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Visualization of Llama-2-7B-chat model's hidden states using 2-dimensional PCA. The color gradient, from light to dark, represents the ranking of model performance on each case's 11 prompts, from low to high. (b) Probing Llama-2-7B-chat model's hidden states for prompt scoring. The x-axis stands for training steps. The y-axis represents the accuracy of the model's predictions, quantified as the proportion of correctly judged prompt pairs out of all test pairs.

More on tables

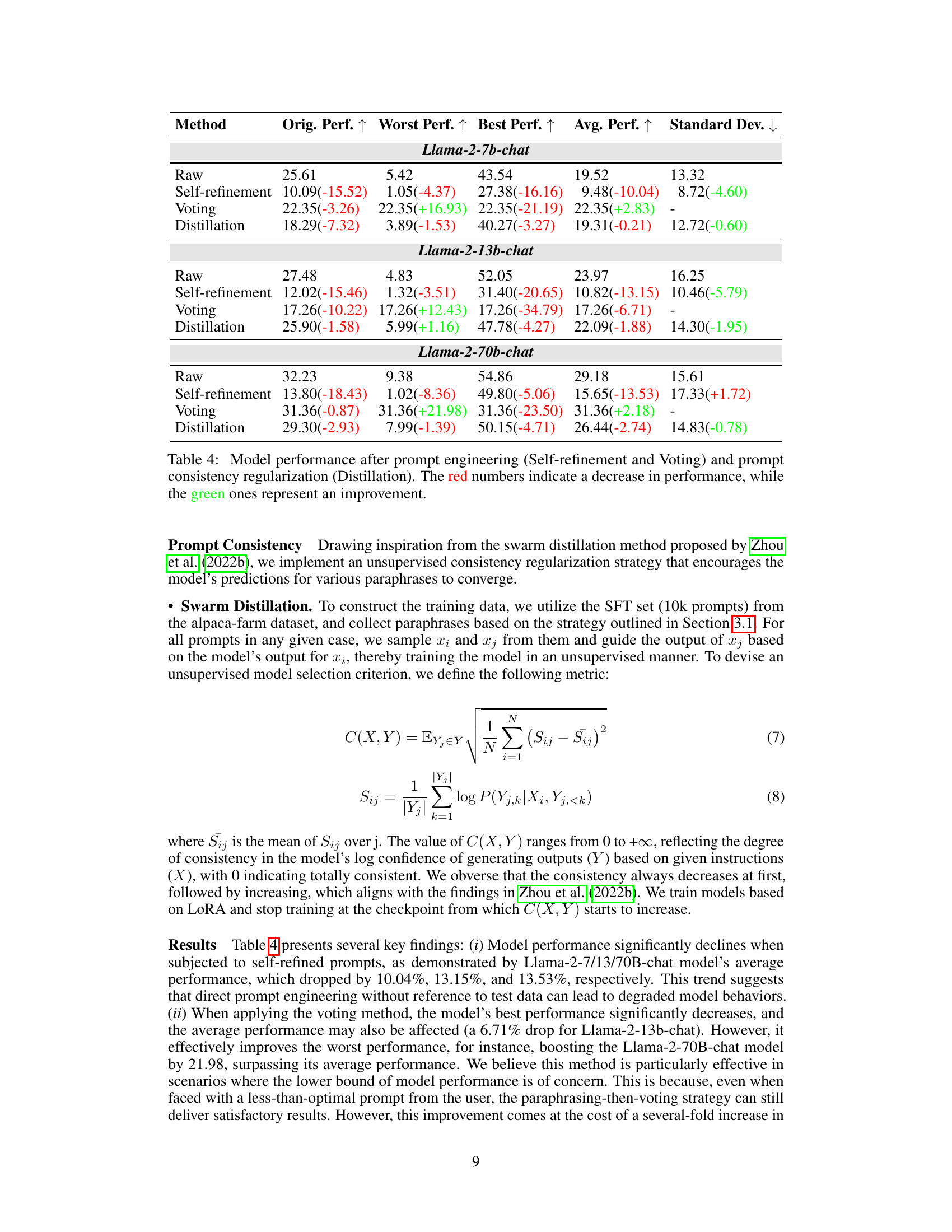

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark using various large language models (LLMs). It shows the original performance, worst performance, best performance, average performance, and standard deviation for each model. The models are ordered by their original performance. The wide range between the best and worst performance highlights the significant sensitivity of LLMs to variations in prompt phrasing, even when semantically equivalent. Scaling model size improves average performance, but does not necessarily lead to improved robustness.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on our ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. The model order is arranged according to their original performance. The substantial range between the worst and best performance suggests the robustness issues in LLMs' instruction-following ability. Scaling up model sizes, while improving average performance, does not enhance robustness.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. It shows the original, worst, best, and average performance of various large language models (LLMs) across multiple semantically equivalent prompts. The significant difference between best and worst performance highlights the robustness issues of LLMs in consistently following instructions, even when the instructions are semantically identical. Interestingly, increasing model size improves average performance but doesn’t necessarily enhance robustness.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on our ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. The model order is arranged according to their original performance. The substantial range between the worst and best performance suggests the robustness issues in LLMs' instruction-following ability. Scaling up model sizes, while improving average performance, does not enhance robustness.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. It shows the original performance, worst performance, best performance, average performance, and standard deviation for seven different large language models (LLMs). The models are ordered by their original performance, illustrating the wide variation in performance between the best and worst prompts for each model, regardless of model size. This highlights the challenge of creating robust LLMs that consistently perform well across diverse prompts.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on our ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. The model order is arranged according to their original performance. The substantial range between the worst and best performance suggests the robustness issues in LLMs' instruction-following ability. Scaling up model sizes, while improving average performance, does not enhance robustness.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark using various large language models (LLMs). It shows the original performance, worst performance, best performance, average performance, and standard deviation for each model. The models are ordered by their original performance. The large differences between best and worst performance highlight the inconsistency of LLMs when responding to semantically similar prompts. Even larger models don’t show improved robustness despite better average performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on our ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. The model order is arranged according to their original performance. The substantial range between the worst and best performance suggests the robustness issues in LLMs' instruction-following ability. Scaling up model sizes, while improving average performance, does not enhance robustness.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark, evaluating the performance of various large language models (LLMs). It shows the original performance, worst performance, best performance, average performance, and standard deviation for each model. The models are ordered by their original performance. The significant difference between the best and worst performances highlights the sensitivity of LLMs to prompt variations, demonstrating the need for more robust models.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on our ROBUSTALPACAEVAL benchmark. The model order is arranged according to their original performance. The substantial range between the worst and best performance suggests the robustness issues in LLMs' instruction-following ability. Scaling up model sizes, while improving average performance, does not enhance robustness.

Full paper#