TL;DR#

Traditional methods for relational inference in multi-agent systems rely on fixed datasets and struggle to adapt to dynamic environments. This significantly limits their real-world applications, particularly in situations where system parameters or interactions change over time. The challenge lies in adapting the model to these changes without sacrificing accuracy or computational efficiency.

The proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) framework tackles this challenge by using online backpropagation and an innovative learning technique (AdaRelation). This allows ORI to adapt in real-time to changes in the data, making it effective for evolving systems. ORI’s performance is demonstrated on both synthetic and real-world datasets, showing significant improvements over existing methods. This framework’s model-agnostic nature makes it easily integrated into existing neural relational inference architectures, highlighting its adaptability and potential for use in a wide range of complex systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on multi-agent systems, online learning, and relational inference. It provides a novel framework, ORI, that addresses the limitations of existing offline methods by enabling real-time adaptation to evolving environments. ORI’s model-agnostic nature and its innovative learning rate adjustment strategy make it highly versatile and applicable across diverse scenarios. This opens avenues for developing more adaptable and robust AI systems in various domains.

Visual Insights#

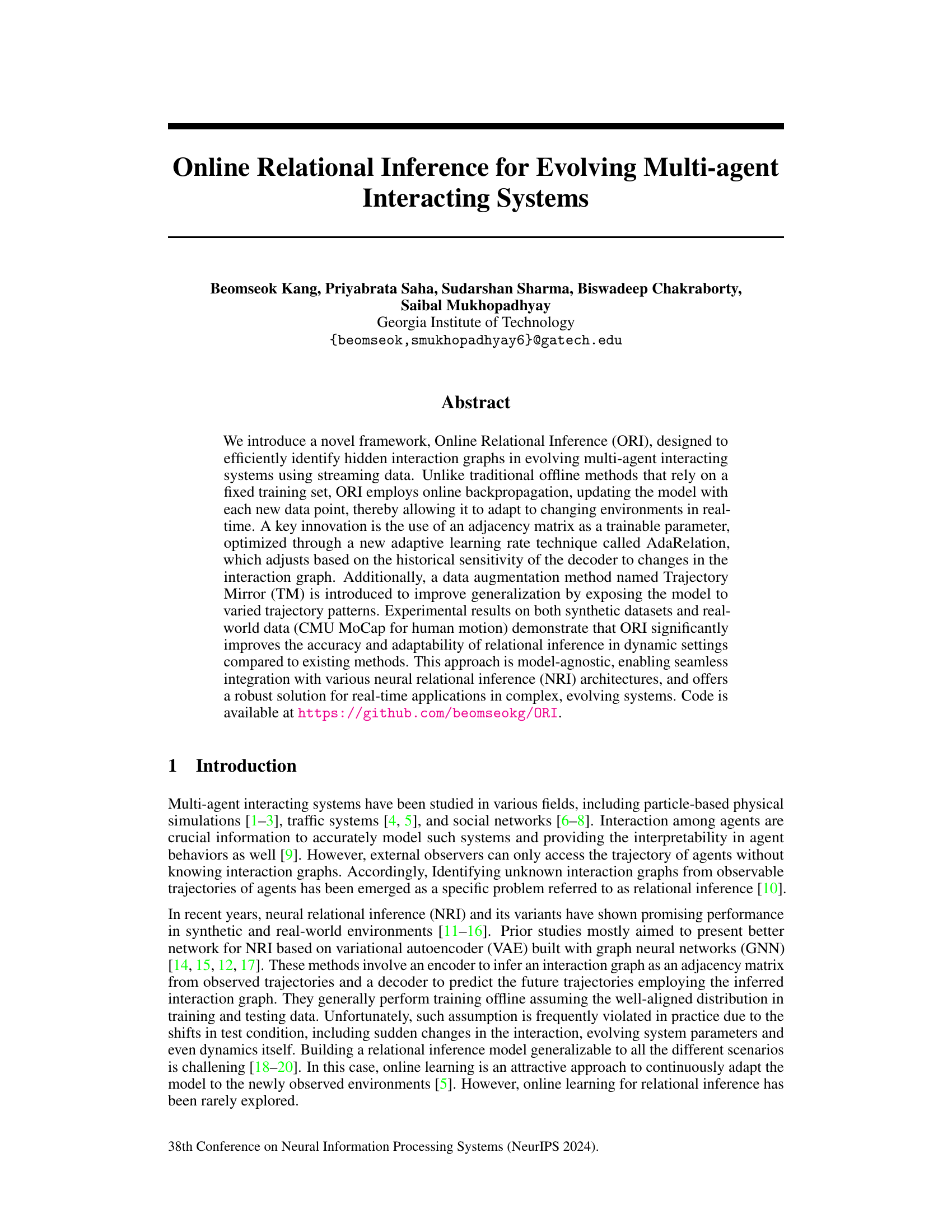

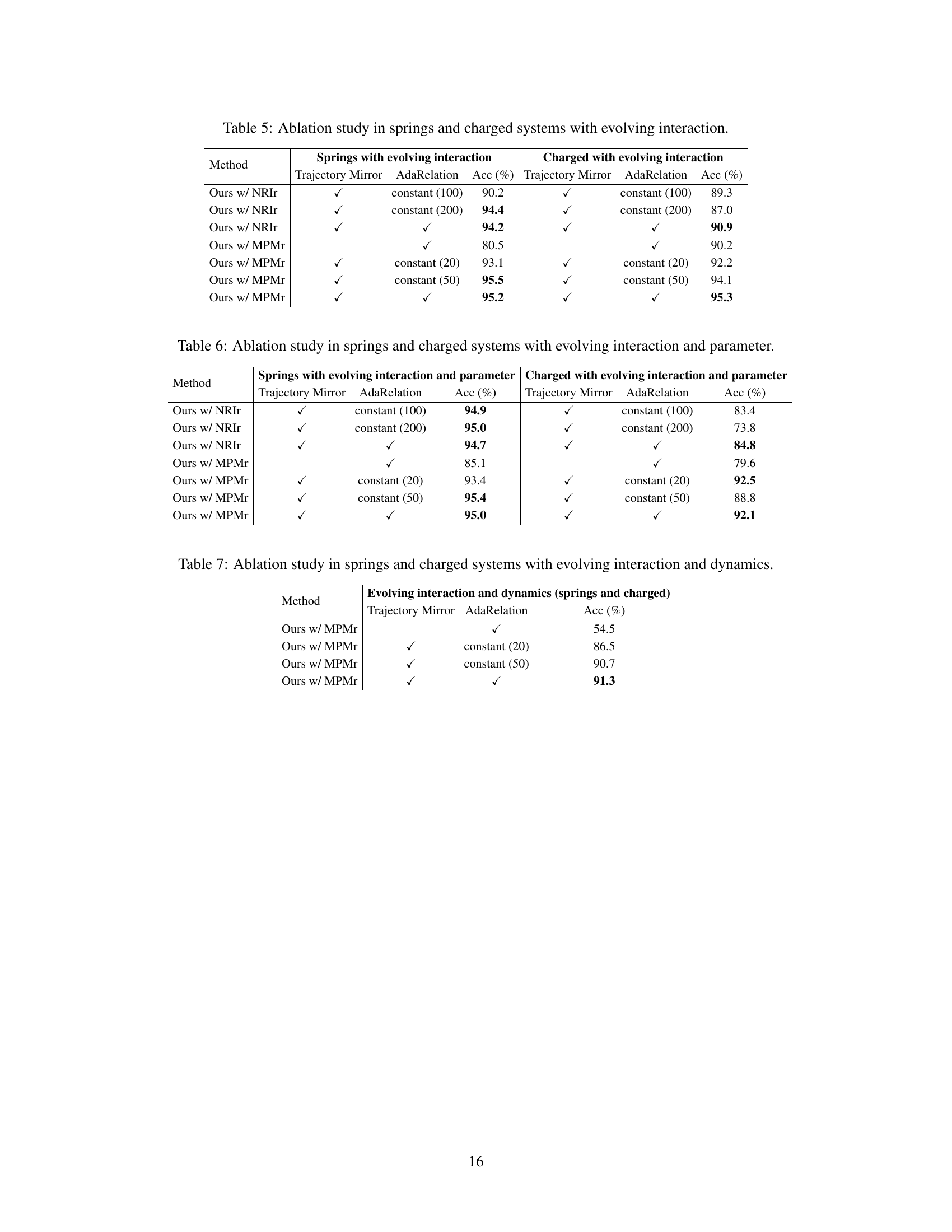

🔼 The figure illustrates the Online Relational Inference (ORI) framework. It shows how the model processes streaming trajectory data to infer interaction graphs in real-time. The process includes a trajectory mirror for data augmentation, a model-agnostic GNN for processing trajectories and predicting future states, and AdaRelation for adaptively adjusting the learning rate of the adjacency matrix based on the evolution of the system. The framework uses online backpropagation to update the model with each new data point, allowing it to adapt to changing environments.

read the caption

Figure 1: A brief illustration of the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) framework.

🔼 This table compares the key features of existing offline and online relational inference methods with the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) method. It highlights differences in backpropagation techniques (offline vs. online), model agnosticism, whether or not the interaction parameters or dynamics are considered to be evolving, and finally the accuracy (Acc) and mean squared error (MSE) achieved by each method. This provides context for understanding ORI’s unique contributions and improvements.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of key features between prior works and this work.

In-depth insights#

ORI Framework#

The Online Relational Inference (ORI) framework presents a novel approach to relational inference in dynamic multi-agent systems. Its core innovation lies in treating the adjacency matrix, representing agent interactions, as a trainable parameter directly optimized via online backpropagation. This contrasts with traditional methods relying on separate encoder-decoder architectures, offering greater efficiency and adaptability. AdaRelation, an adaptive learning rate mechanism, dynamically adjusts the learning rate based on decoder sensitivity, enhancing model stability and convergence speed in evolving environments. Furthermore, the Trajectory Mirror data augmentation technique improves generalization by exposing the model to varied trajectory patterns. The model-agnostic nature of ORI allows for seamless integration with existing neural relational inference architectures. Overall, ORI offers a robust, real-time solution for relational inference in complex scenarios where system dynamics and interactions change constantly, showcasing its potential for significant applications in various fields.

Adaptive Learning#

Adaptive learning, in the context of relational inference for evolving multi-agent systems, is crucial for handling dynamic environments. The core idea is to dynamically adjust model parameters, such as learning rates, based on the observed changes in the system’s behavior. This contrasts with traditional static learning rates that remain constant throughout the training process. A key aspect is identifying a suitable metric to track system dynamics; this metric informs the adjustment of the learning process. For instance, changes in the adjacency matrix representing agent interactions might trigger an increase in the learning rate to accelerate adaptation to a new system state. Conversely, stability considerations dictate a decrease in the learning rate to prevent overfitting and oscillation when the system is relatively stable. The effectiveness of such an approach hinges on the proper balancing of adaptation speed and stability. Too much sensitivity risks instability, while insufficient sensitivity could lead to slow convergence or failure to adapt to changes. The ultimate goal is a robust model capable of responding effectively to various evolving scenarios while maintaining accuracy.

Trajectory Mirror#

The proposed data augmentation technique, “Trajectory Mirror,” addresses potential biases in training data by systematically flipping the axes of observed trajectories. This clever approach ensures the model is exposed to a more diverse range of trajectory patterns, improving generalization and reducing the risk of overfitting to specific orientations. By creating mirrored versions of the existing data, Trajectory Mirror effectively doubles the dataset size, enhancing model robustness and improving performance, especially in scenarios where the orientation of trajectories may influence the model’s accuracy. This augmentation method is particularly valuable for online learning scenarios because it helps to continuously diversify the training data, a critical aspect for adapting to evolving environments in real time.

Evolving Systems#

The concept of ’evolving systems’ in the context of multi-agent interaction presents a significant challenge, as traditional methods often assume static environments. Online learning is crucial for addressing this dynamism, where models must adapt in real-time to changing interaction patterns. The research highlights the limitations of existing offline approaches that struggle to generalize to new scenarios. Adaptability and accuracy are key factors that need to be balanced: a model that adapts too quickly might become unstable, while one that adapts too slowly might lag behind the changes in the system. Data augmentation, using techniques like Trajectory Mirror, proves beneficial for improving model robustness and generalization. The use of an adjacency matrix as a trainable parameter allows for direct optimization of the interactions, accelerating the learning process compared to methods relying solely on an encoder-decoder architecture. The exploration of synthetic datasets and real-world data (like CMU MoCap) provides valuable insights into the efficacy of the proposed methods, demonstrating improvements in handling both gradual and sudden changes within the system dynamics.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Extending the model to handle dynamic changes in the number of agents is crucial for real-world applicability. This involves developing mechanisms for seamlessly adding or removing agents from the interaction graph, maintaining model accuracy and efficiency. Investigating the model’s robustness under noisy or incomplete data is another critical area, focusing on developing strategies for handling missing data points and mitigating the impact of sensor noise or errors on inference accuracy. Exploring different model architectures beyond those tested in the paper could lead to significant performance improvements. Comparing and contrasting the efficiency and effectiveness of various deep learning frameworks would yield important insights into optimal design choices. Furthermore, the application of this relational inference framework to more complex real-world systems needs to be explored, such as traffic management, social networks, or biological systems, to demonstrate broad applicability and practical utility. Finally, a comprehensive analysis of the trade-offs between accuracy, computational efficiency, and model complexity would provide a clearer picture of the framework’s capabilities and limitations in various application settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

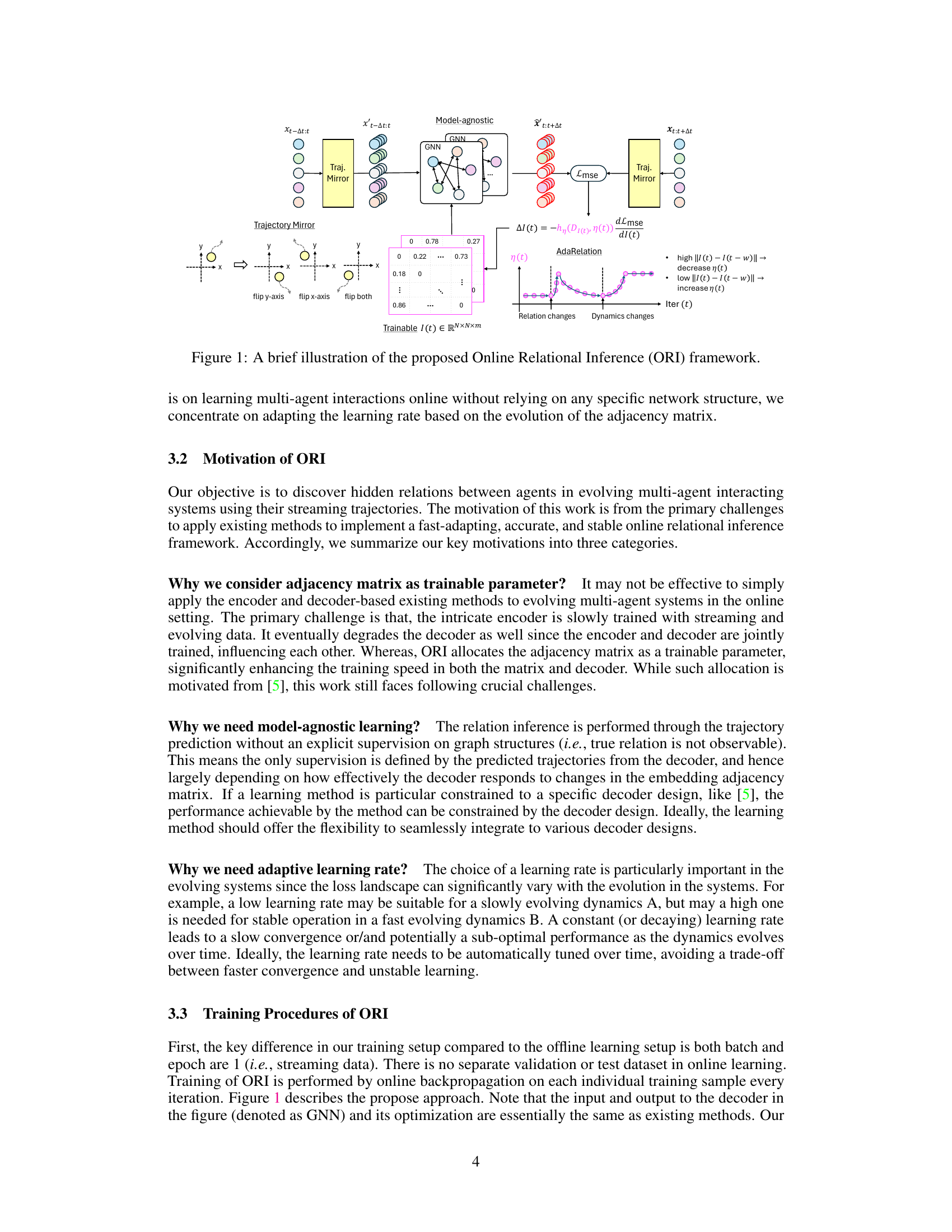

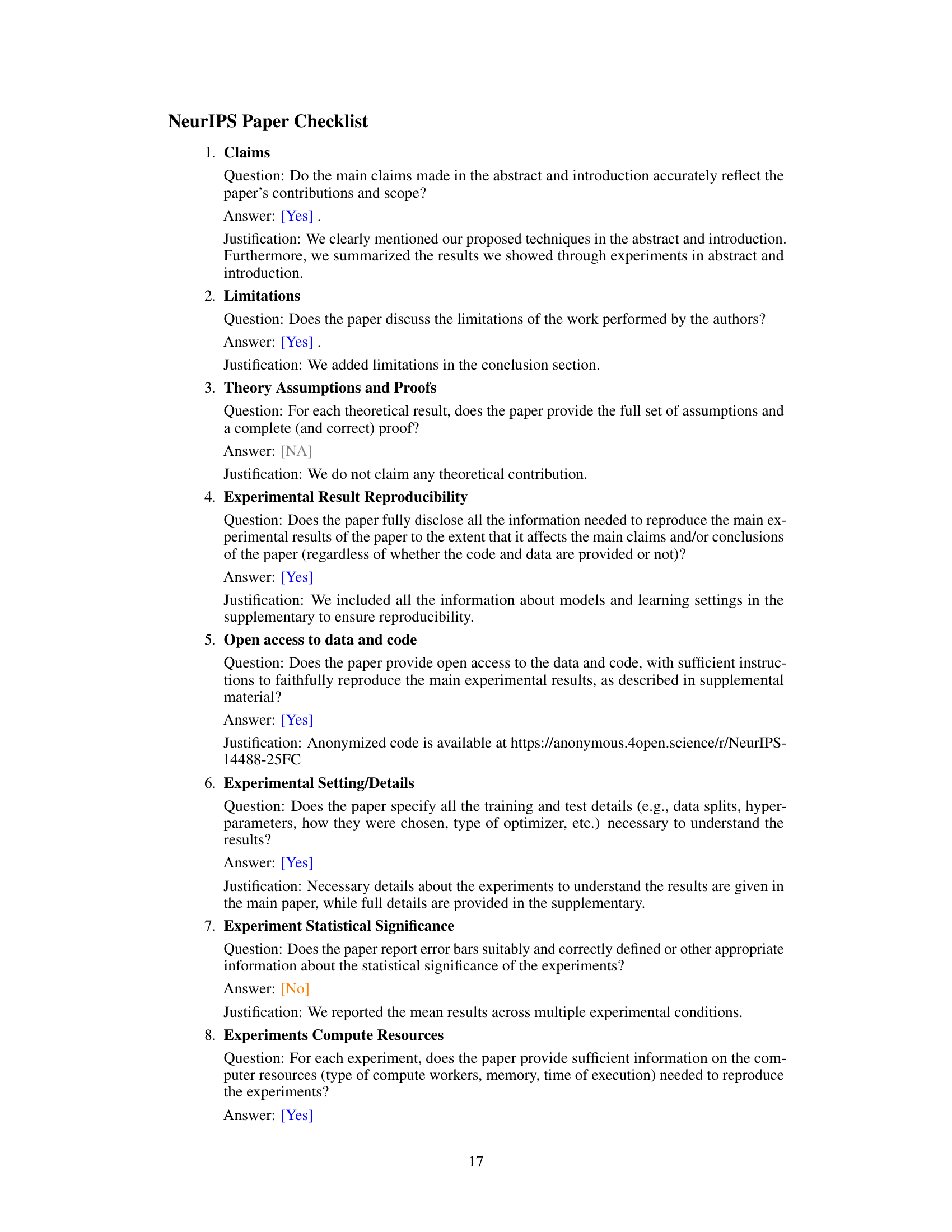

🔼 This figure shows the comparison between the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) method and the baseline method (MPM) in a spring system where the interaction graph evolves every 3000 iterations. The top panel of (a) presents the relation accuracy over training iterations, demonstrating ORI’s superior performance in adapting to the evolving graph. The bottom panel of (a) visualizes the target and predicted adjacency matrices at different time points, illustrating ORI’s ability to accurately infer the interaction graph. Panel (b) displays the target and predicted trajectories at specific iterations (15k and 18k-1), further showcasing ORI’s accurate trajectory prediction.

read the caption

Figure 2: Prediction results of ORI with MPMr decoder and the baseline MPM in the springs system. (a) the relation accuracy in the two models throughout the training (top) and visualization of the target and predicted adjacency matrix in our model (bottom). (b) target and predicted trajectories in our model.

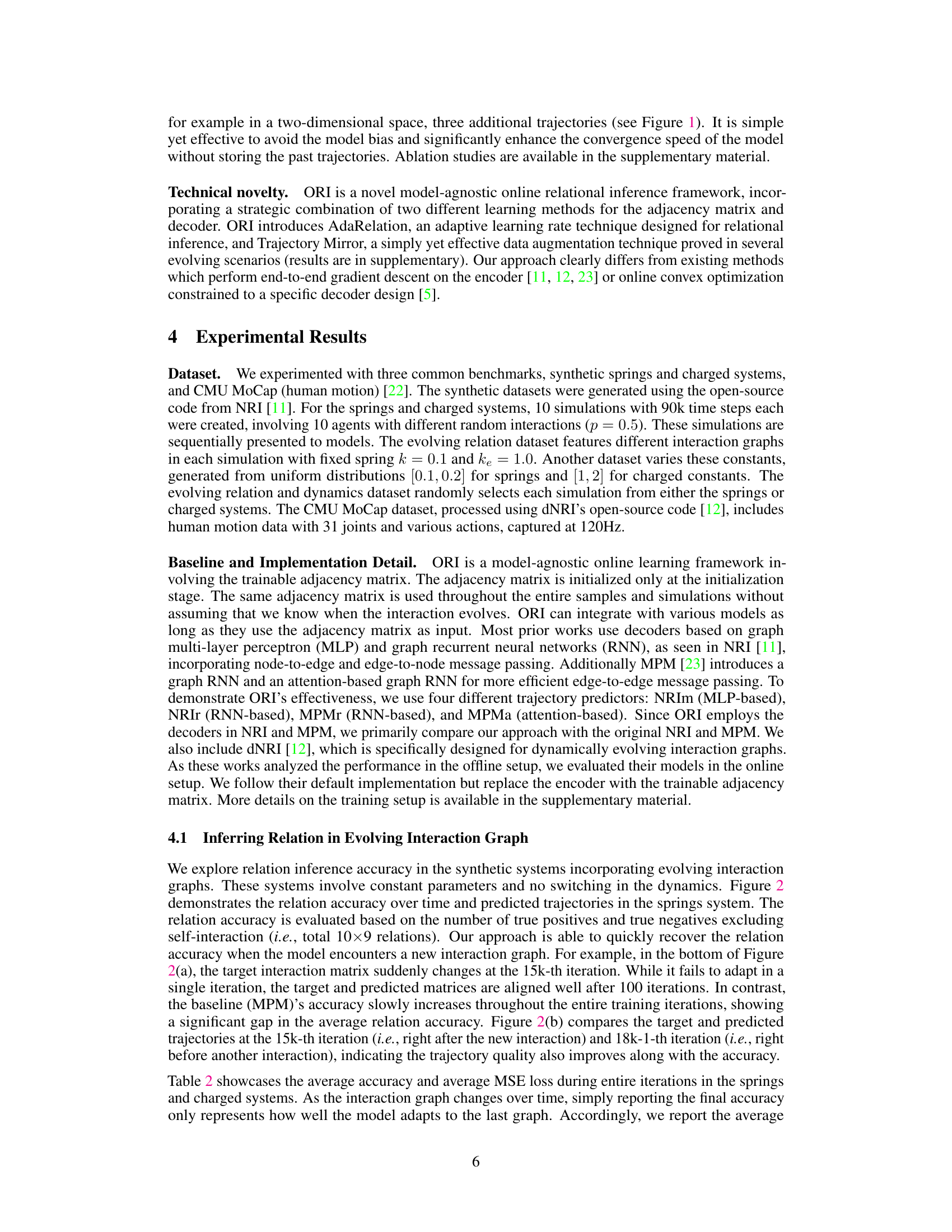

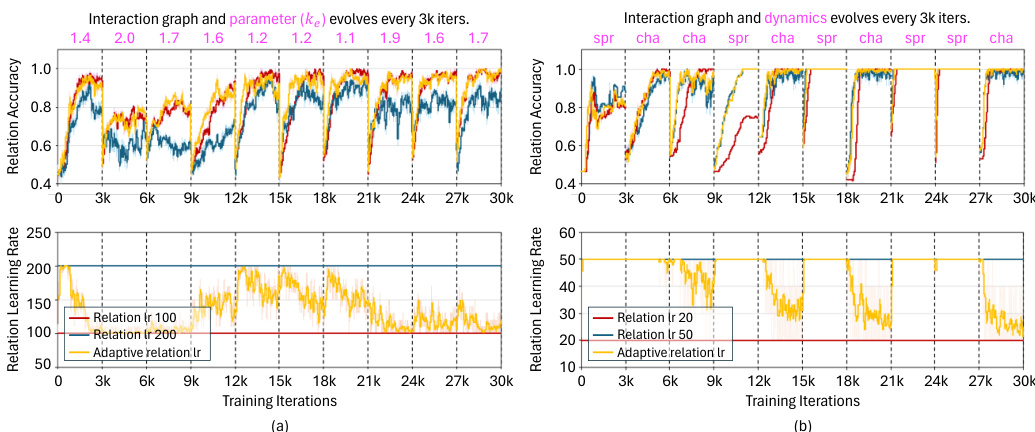

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of ORI in scenarios with evolving interaction graphs and dynamics. Subfigure (a) shows results for a charged system where both the interaction graph and parameters change every 3000 iterations. Subfigure (b) shows results for both spring and charged systems where both the interaction graph and the dynamics change every 3000 iterations. The top row of each subfigure displays the relation accuracy over time for ORI using different learning rate strategies: a constant learning rate, and the proposed adaptive learning rate (AdaRelation). The bottom row shows how the relation learning rate changes over time. The results illustrate AdaRelation’s effectiveness in adapting to these dynamic scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 3: Prediction results of ORI with NRIr decoder in the charged system with evolving interaction and parameters (a) and ORI with MPMr decoder in the springs and charged systems with evolving interaction and dynamics (b). 1-st row compares the relation accuracy between constant learning rates and AdaRelation. 2-nd row shows changes in the relation learning rate throughout the training.

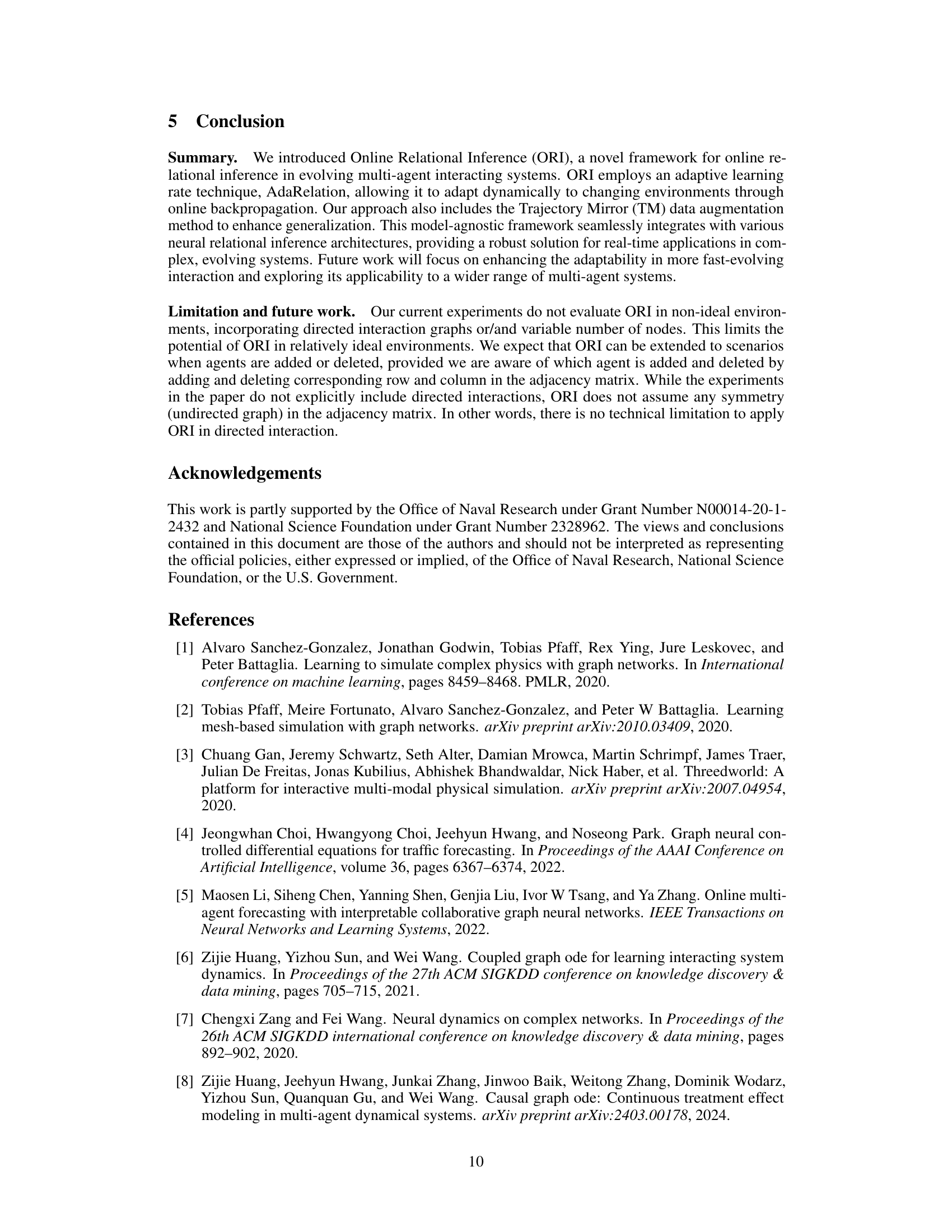

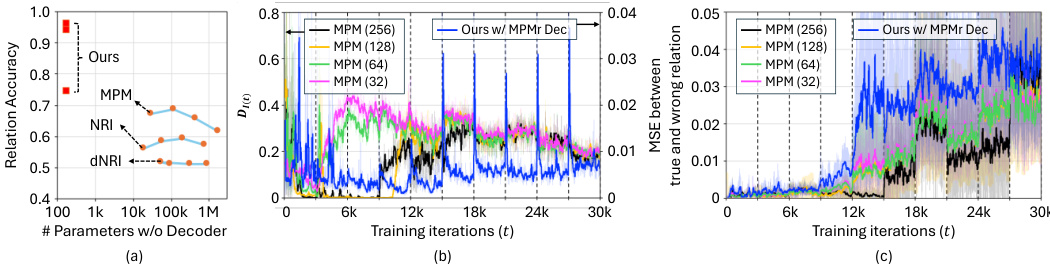

🔼 This figure compares ORI’s performance against existing methods (MPM with varying encoder sizes and NRI, dNRI) across three key metrics: relation accuracy, variance in the adjacency matrix, and variance in the predicted trajectory. Subfigure (a) shows that ORI achieves high relation accuracy with significantly fewer parameters than the other methods. Subfigure (b) demonstrates the stability of ORI’s adjacency matrix updates compared to the others, which experience fluctuations. Finally, subfigure (c) highlights that ORI’s trajectory predictions are highly sensitive to correct interaction information, further showcasing its robustness.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison between ORI and existing methods with respect to the relation accuracy (a), variance in the adjacency matrix (b), and variance in the predicted trajectory (c) depending on encoder complexity. The number in the MPM (·) represents the dimension of hidden states in the encoder.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Online Relational Inference (ORI) and the baseline method (MPM) on the CMU MoCap dataset, focusing on a walking motion. The top row shows a 3D visualization of the predicted and actual trajectories from both methods, highlighting the similarity between ORI’s prediction and the ground truth. The middle and bottom rows provide a detailed view of the top 30 strongest inferred interactions (edges) between skeletal joints, visualized as lines connecting the joints. The comparison shows that ORI focuses its attention on the foot behind during the walking motion, whereas MPM emphasizes the front foot. This suggests that ORI yields more nuanced and potentially more accurate estimations of the interactions in the human body during movement.

read the caption

Figure 5: Prediction results of ORI with MPMr decoder and MPM in CMU MoCap dataset. 1-st row represents the last frame in the predicted and target trajectory from ORI. 2-nd and 3-rd rows visualize the top-30 strongest interaction edges in the corresponding frame from ORI and MPM. Note that MPM allocate higher relation strengths in the front foot while ORI focuses on the foot behind.

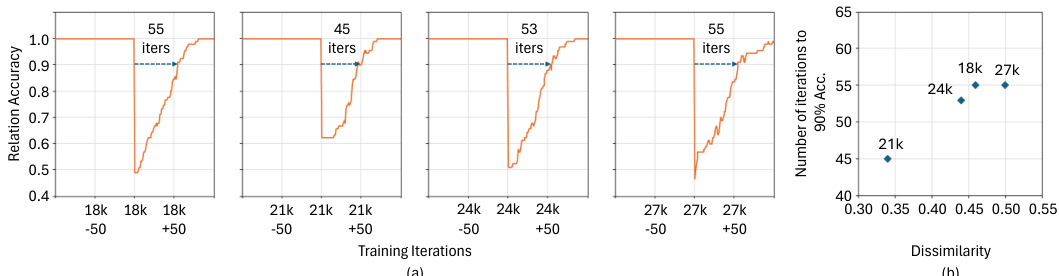

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between the dissimilarity of interaction graphs and the number of iterations needed to achieve 90% accuracy in the springs system using the ORI model with the MPMr decoder. The dissimilarity measures how different two interaction graphs are. The plots (a) demonstrate that for similar graphs, convergence is faster, while for dissimilar graphs, it takes more iterations to reach 90% accuracy. Plot (b) displays this correlation using a scatter plot, illustrating the relationship between dissimilarity and the number of iterations.

read the caption

Figure 6: Correlation between the dissimilarity and the number of iterations required to reach 90% accuracy since the interaction graph evolves in ORI with MPMr decoder in the springs system.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of the ORI model with MPMr decoder in five different scenarios with irregular evolution in interactions. Each scenario has a different pattern of interaction graph changes at varying intervals (1k, 2k, or 3k iterations). The x-axis represents the training iterations, and the y-axis represents the relation accuracy. The graph demonstrates how well the ORI model adapts to these different irregular interaction changes, showing that the model is able to quickly adapt and maintain high accuracy despite the irregular timing of changes. This highlights the model’s robustness and ability to handle dynamic environments.

read the caption

Figure 7: ORI with MPMr decoder in five different cases with irregular evolution in interaction. The system is based on springs system with 10 agents and consists of three 1k iterations, four 2k iterations, and three 3k iterations.

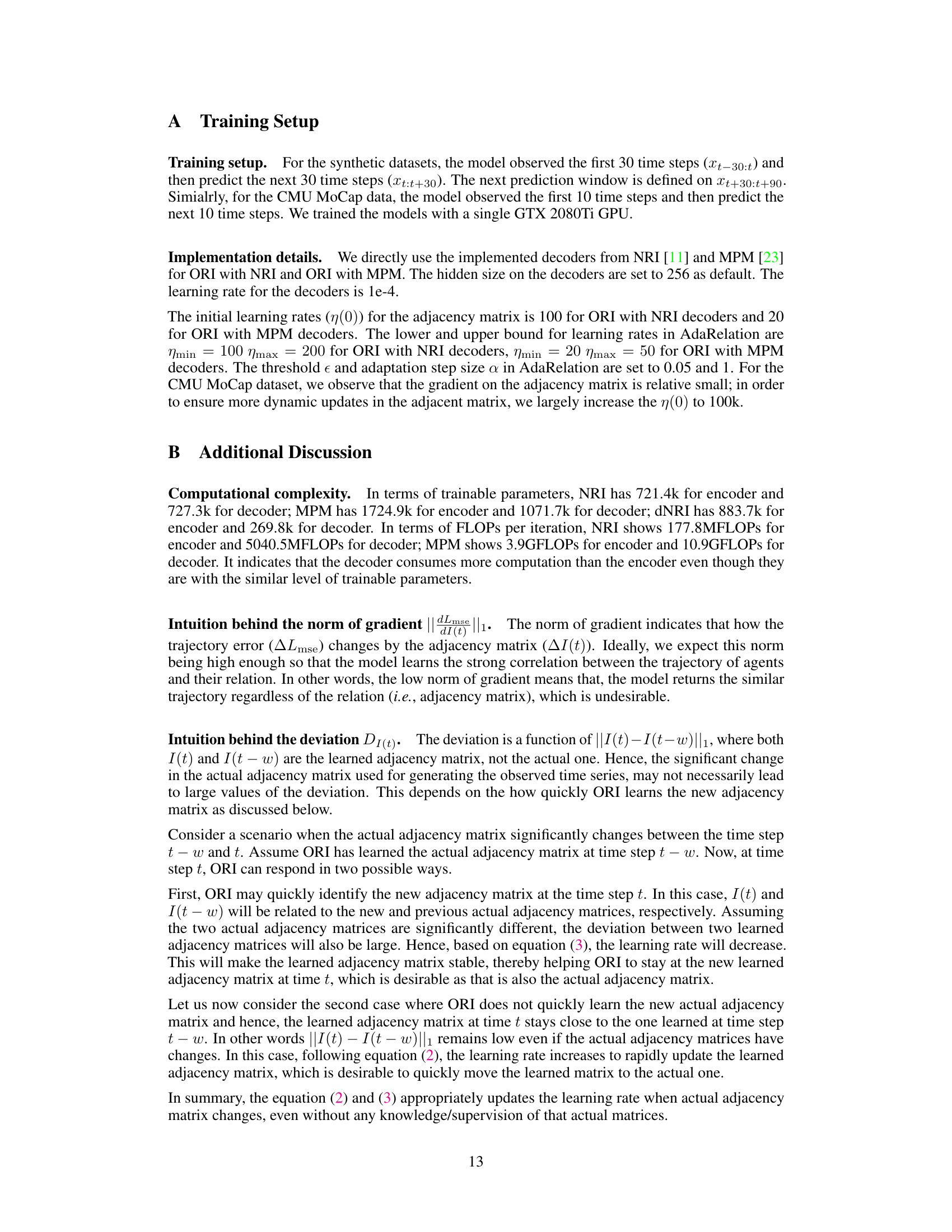

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) method with existing offline methods (dNRI, NRI, MPM) on two synthetic datasets: springs and charged systems. The evaluation metrics include relation accuracy (Acc) and mean squared error (MSE) of the predicted trajectories at different time steps (mse 1, mse 10, mse 20, mse 30). The results demonstrate ORI’s superior accuracy and adaptability in dynamic settings.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with offline learning models in springs and charged systems with evolving interactions. Acc and mse stand for the relation accuracy and mse on the predicted trajectory averaged over the entire training iterations. The number following mse (e.g., mse 10) denotes the mse at the 10-th prediction time step.

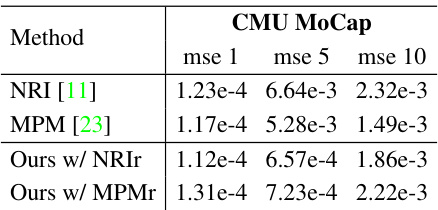

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss for trajectory prediction on the CMU Motion Capture (MoCap) dataset. It shows the MSE values at different prediction time steps (1, 5, and 10) for four different methods: NRI, MPM, and two variations of the proposed ORI method (using NRIr and MPMr decoders). The results show how the proposed ORI method compares to existing methods in terms of trajectory prediction accuracy on real-world human motion data.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of MSE loss on the predicted trajectory in the CMU MoCap dataset.

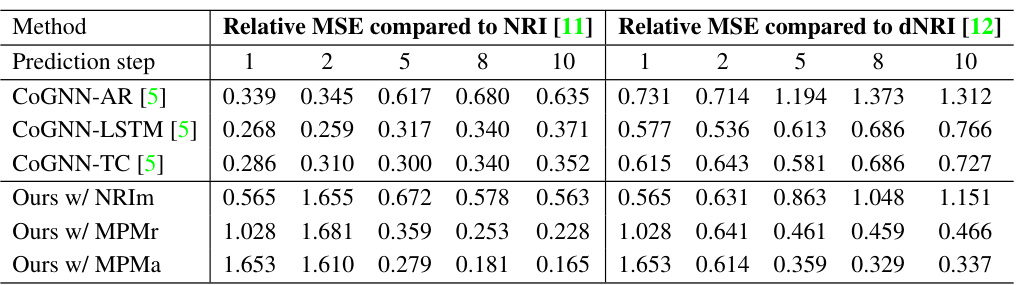

🔼 This table compares the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) method with a prior online learning method (COGNN) for relational inference in spring systems with 20 agents. The comparison is based on relative Mean Squared Error (MSE) compared to the results of two existing offline methods (NRI and dNRI). Lower relative MSE values indicate better performance. The table shows the relative MSE for different prediction steps (1, 2, 5, 8, 10), demonstrating how the methods perform over time.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison with prior online learning method in springs systems with 20 agents.

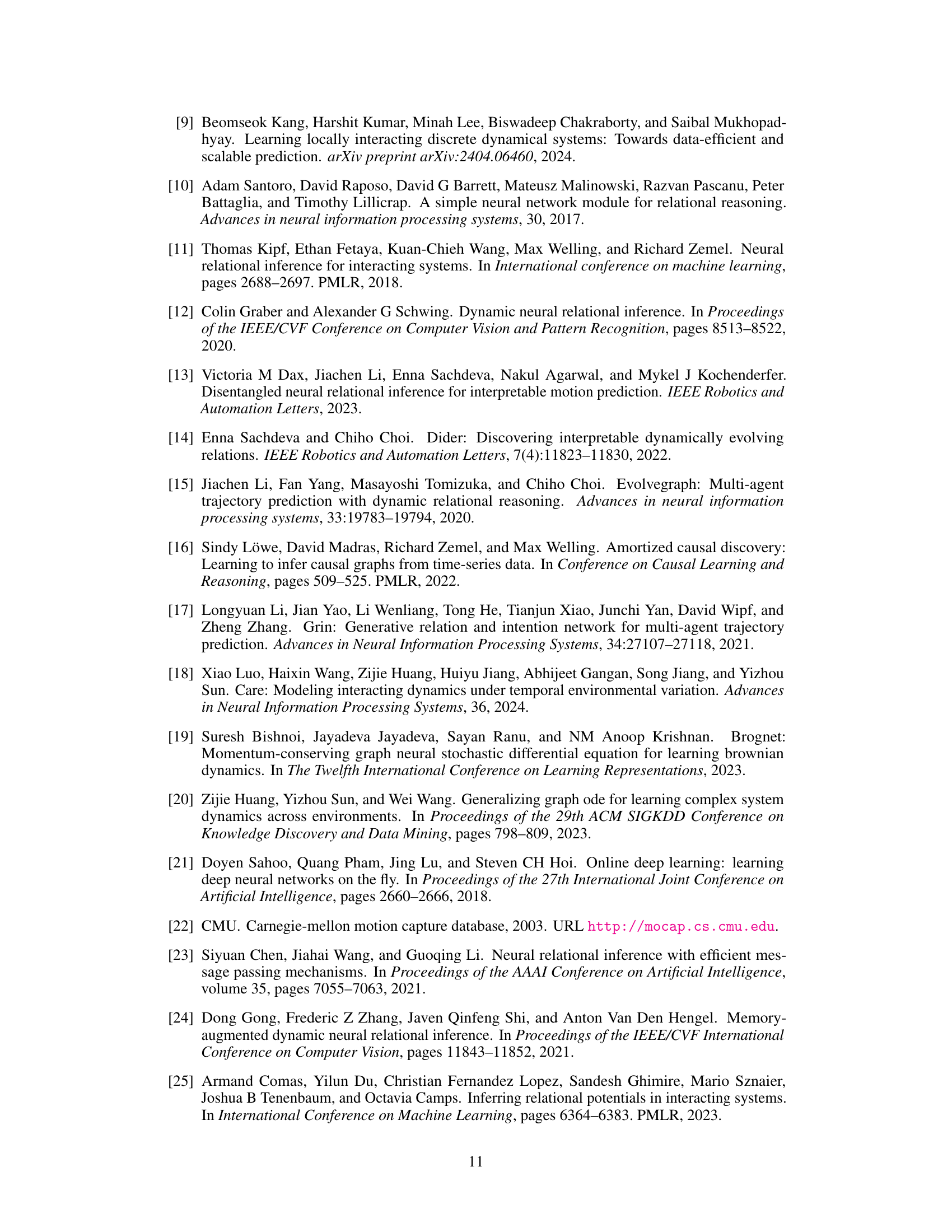

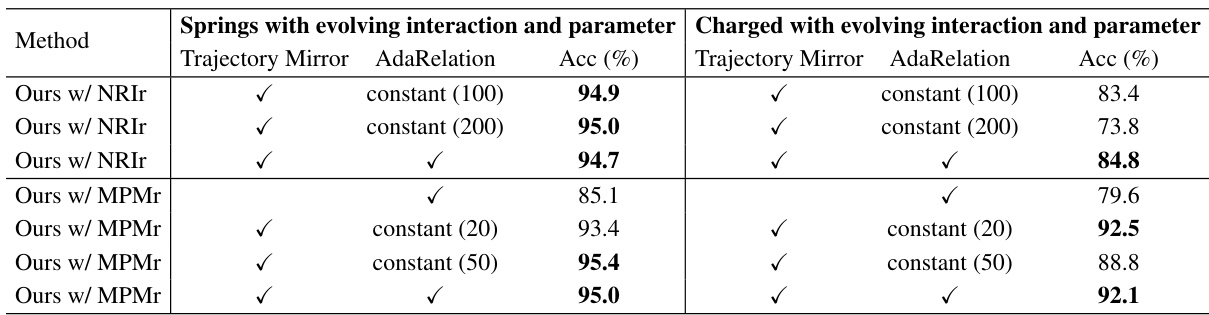

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the impact of Trajectory Mirror and AdaRelation on the accuracy of relational inference in systems with evolving interactions. It compares the accuracy achieved with different combinations of these two techniques (enabled/disabled) across both spring and charged systems. The results demonstrate the relative contribution of each technique in improving the accuracy of relational inference.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study in springs and charged systems with evolving interaction.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results, comparing the performance of the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) method with different configurations of Trajectory Mirror and AdaRelation in springs and charged systems with evolving interactions and parameters. It demonstrates the impact of these techniques on the accuracy of relational inference.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation study in springs and charged systems with evolving interaction and parameter.

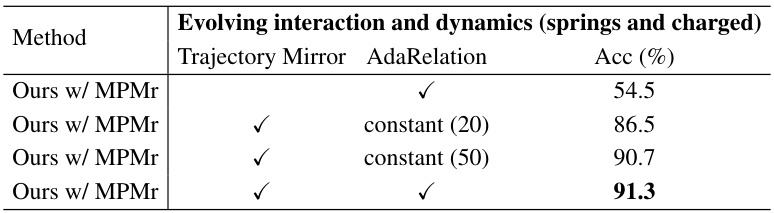

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results for the proposed Online Relational Inference (ORI) method on spring and charged systems with evolving interactions and dynamics. It shows the impact of Trajectory Mirror and AdaRelation techniques on the accuracy (Acc (%)) of relational inference. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of these techniques in improving the accuracy of ORI.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation study in springs and charged systems with evolving interaction and dynamics.

Full paper#