↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many AI systems use explainability methods to provide insights into their decision-making processes. However, a recent study reveals that some explanation methods suffer from a phenomenon called “encoding.” Encoding occurs when an explanation’s predictive power comes not only from the values of the selected features but also from the act of selecting those features, causing these methods to produce seemingly accurate yet deceptive explanations. This is problematic because it can lead researchers to incorrect conclusions.

To address this issue, the researchers introduce a novel metric called STRIPE-X. STRIPE-X provides a more robust way to evaluate explanations, effectively identifying cases of encoding. They demonstrate this through theoretical analysis and experiments using simulated data and real-world examples like sentiment analysis from movie reviews. STRIPE-X offers a significant advance in interpretability research, helping to build more reliable and transparent AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on explainable AI and model interpretability. It identifies and addresses the problem of encoding in explanations, a significant issue that can lead to misleading interpretations. The proposed STRIPE-X evaluation method is a valuable tool for assessing the quality of explanations and developing more reliable and transparent AI systems.

Visual Insights#

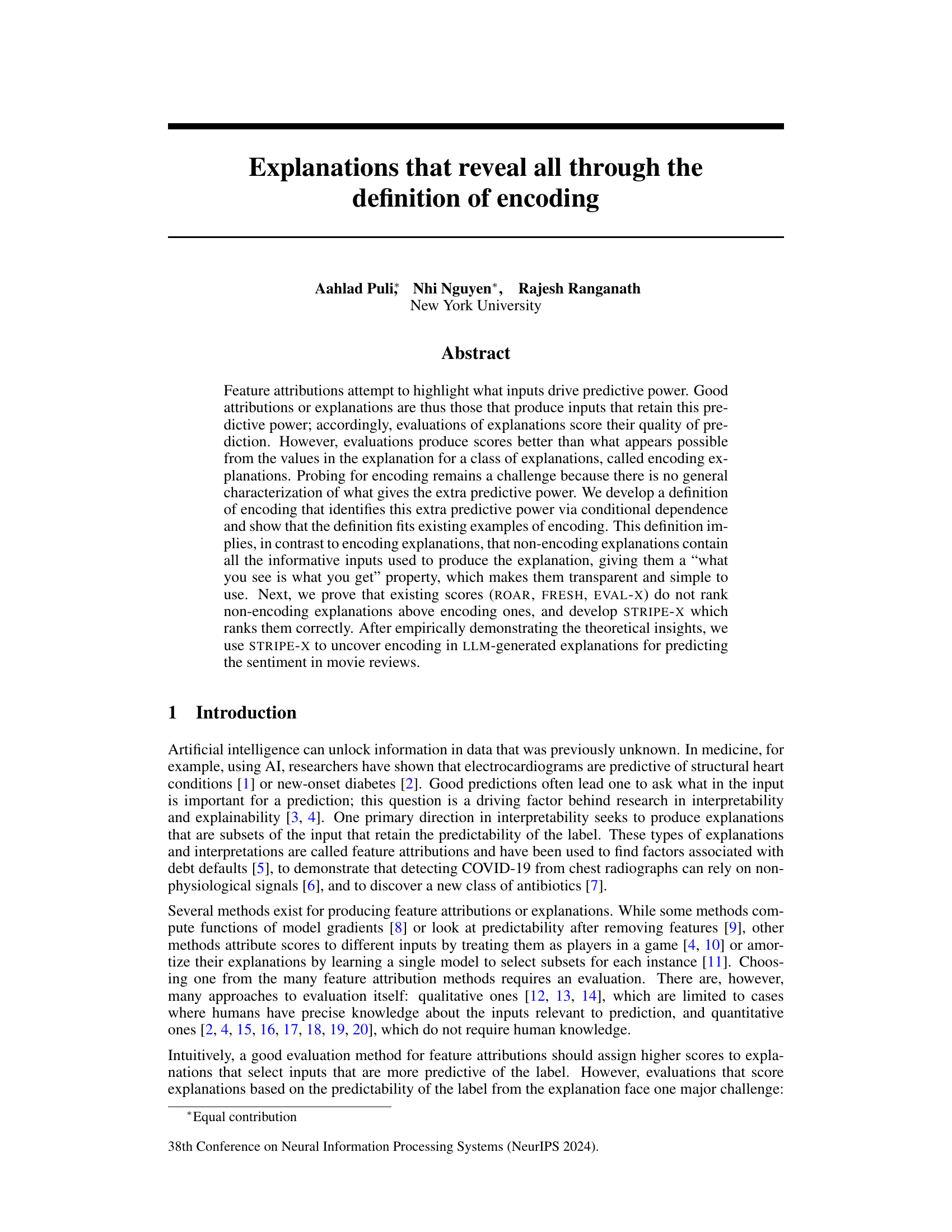

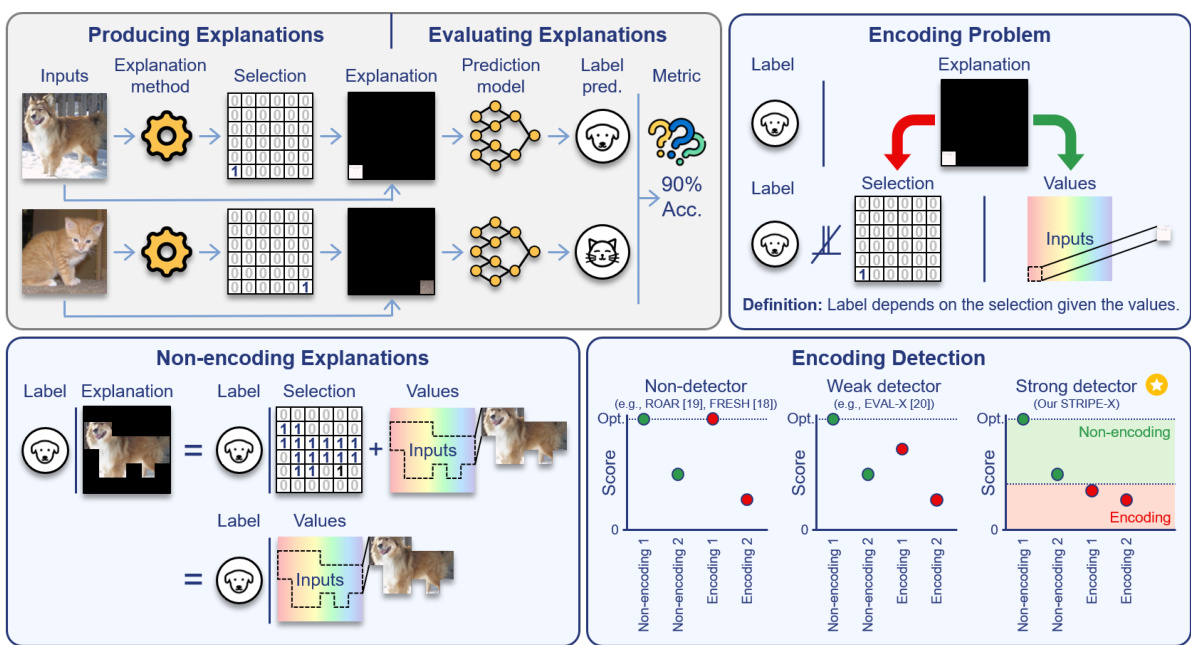

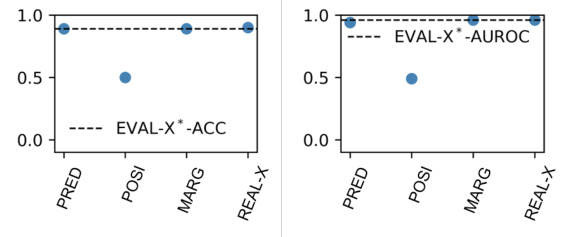

This figure provides a visual overview of the paper’s main contributions. It illustrates the process of producing and evaluating explanations, highlighting the problem of encoding where explanations predict labels better than expected based solely on their values. It introduces three types of explanation evaluation methods: non-detectors, weak detectors, and strong detectors. It highlights the role of STRIPE-X, a newly developed strong detector for identifying encoding.

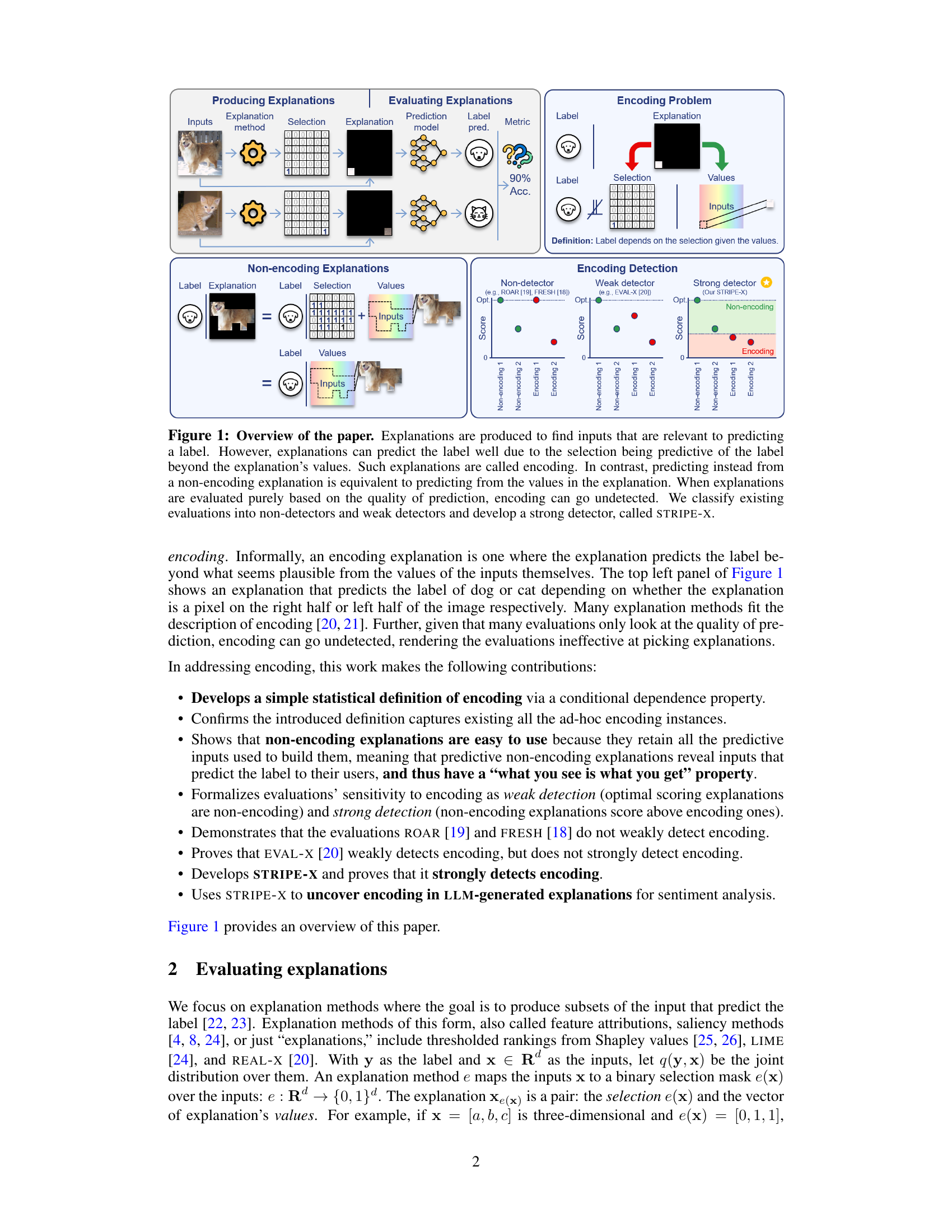

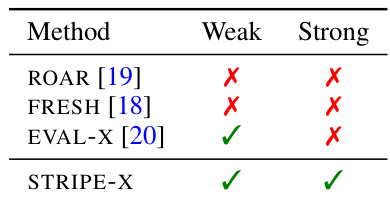

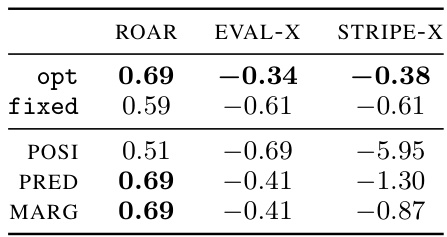

This table summarizes the ability of different explanation evaluation methods to detect encoding. A ‘weak detector’ correctly identifies non-encoding explanations as optimal. A ‘strong detector’ ranks non-encoding explanations higher than encoding explanations. The table shows that ROAR and FRESH fail at weak detection and therefore also at strong detection. EVAL-X manages weak detection but fails at strong detection. Only STRIPE-X achieves both.

In-depth insights#

Encoding’s Pitfalls#

The concept of “Encoding’s Pitfalls” in the context of explainable AI highlights the crucial challenge of evaluating explanations based solely on predictive performance. Standard evaluation metrics often fail to distinguish between explanations that genuinely capture the model’s decision-making process and those that achieve high scores through spurious correlations, a phenomenon termed “encoding.” Encoding exploits statistical dependencies between the selected features and the label, exceeding the predictive power inherent in the feature values themselves. This leads to explanations that seem highly accurate but offer little true insight into the model, obscuring important predictive features not included in the explanation. Therefore, a robust evaluation method needs to move beyond predictive accuracy and explicitly account for this “encoding” effect, ensuring that explanations are not only predictive but also transparent, providing a clear and faithful representation of the model’s reasoning. Developing such evaluation methods is a critical step towards building truly reliable and insightful explainable AI systems.

STRIPE-X: Strong Test#

The heading ‘STRIPE-X: Strong Test’ suggests a section dedicated to evaluating the performance of STRIPE-X, a novel method proposed in the research paper. A strong test in this context likely means a rigorous evaluation designed to demonstrate STRIPE-X’s ability to accurately identify encoding in explanations, a key challenge addressed by the paper. This section would likely involve comparing STRIPE-X’s performance against existing methods, using diverse datasets and types of explanations. Key aspects of the evaluation may include assessing the sensitivity and specificity of STRIPE-X, ensuring it correctly flags encoding explanations while avoiding false positives. The results of this strong test would be crucial to validating the effectiveness and reliability of STRIPE-X in real-world applications. The results would likely demonstrate that STRIPE-X outperforms existing methods in identifying encoded explanations.

Encoding in LLMs#

The section on “Encoding in LLMs” would explore how large language models (LLMs) can generate explanations that exhibit encoding, a phenomenon where the information about a label in the explanation exceeds what’s available from the explanation’s values alone. This would involve analyzing LLM-generated explanations for signs of encoding, using techniques like those described in the paper (such as STRIPE-X). The analysis would likely show that LLMs, despite instructions to be transparent, frequently produce explanations that conceal crucial predictive information, making them less useful for human understanding. A key finding might be that LLM explanations often exploit relationships between input features that are not readily apparent from the chosen subset alone, resulting in high predictive accuracy but limited interpretability. The discussion would likely conclude with suggestions for prompting strategies, LLM training methods, or evaluation metrics that might mitigate the problem of encoding in LLM explanations, promoting more trustworthy and transparent AI systems.

Evaluation Methods#

The effectiveness of feature attribution methods hinges on robust evaluation methods. Existing approaches, such as those based on prediction accuracy, often fall short because they don’t account for a phenomenon called encoding. Encoding occurs when an explanation’s predictive power stems from information not explicitly present in its values, essentially hiding crucial predictive factors from the user. The paper highlights the shortcomings of standard evaluation metrics like ROAR and FRESH which fail to detect encoding, leading to misleading conclusions. A novel definition of encoding is proposed, clarifying the hidden dependence that characterizes it, and consequently enabling better evaluations. This leads to the development of a new metric, STRIPE-X, which effectively distinguishes between encoding and non-encoding explanations, providing a more reliable means to assess the quality of feature attributions and ensure that interpretations of AI models are genuinely informative and transparent.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the definition of encoding to encompass label leakage and faithfulness would provide a more unified framework for explanation evaluation. Investigating the impact of model misestimation on the effectiveness of encoding detection is crucial, particularly concerning the reliability of existing methods and the development of more robust techniques. Developing methods to build non-encoding explanations using LLMs, potentially through prompt engineering or model fine-tuning guided by STRIPE-X scores, is another key area. Furthermore, research is needed to explore the intersection of encoding and human understanding of explanations. Are humans sensitive to encoding in the same way that STRIPE-X is? Finally, analyzing how encoding manifests across different explanation methods and model architectures is vital to generalize the findings and make them widely applicable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

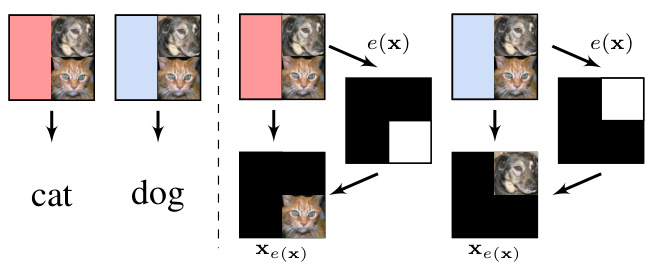

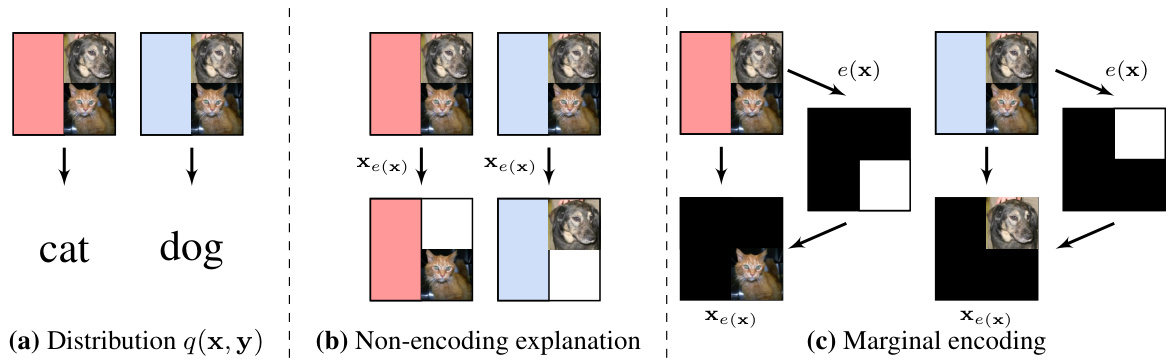

The figure illustrates the paper’s main contributions. It shows how explanations are generated (producing explanations), evaluated (evaluating explanations), and how the concept of ’encoding’ in explanations arises when a selection of inputs is predictive of the label beyond the values of the selected inputs themselves. The figure also categorizes existing explanation evaluation methods as non-detectors or weak detectors of encoding, highlighting the novelty of the proposed STRIPE-X method, which is a strong detector of encoding.

The figure provides a visual overview of the paper’s main contributions. It illustrates the process of producing explanations, evaluating their quality, and the challenge of encoding. The left side shows the process of generating explanations (producing explanations) from inputs, focusing on the difference between encoding and non-encoding explanations. The middle section illustrates how explanations are evaluated (evaluating explanations), highlighting the limitations of existing methods (non-detector and weak detector). The right side focuses on the paper’s key contribution: a novel strong detector called STRIPE-X designed to correctly identify and classify explanations.

This figure gives a high-level overview of the paper. It illustrates the process of producing and evaluating explanations for machine learning models. The key concept is ’encoding,’ where an explanation predicts the label better than expected based solely on the input values it includes. The figure contrasts encoding and non-encoding explanations, and highlights how existing evaluation methods fail to detect encoding, leading to the development of a new method called STRIPE-X.

The figure illustrates the paper’s main idea: identifying and addressing the ’encoding’ problem in explanations. Encoding explanations achieve high predictive power not from the values of their selected features, but from a hidden dependency between the selection and the label. The figure shows how explanations are generated, evaluated (using existing methods and a new method STRIPE-X), and how STRIPE-X can detect encoding, which is undetectable by other methods.

This figure gives a high-level overview of the paper. It illustrates the process of producing and evaluating explanations, highlighting the problem of ’encoding’ where an explanation predicts the label better than expected from its values alone. The figure contrasts encoding and non-encoding explanations and classifies existing explanation evaluation methods into three categories: non-detectors, weak detectors, and strong detectors. Finally, it introduces the paper’s main contribution: STRIPE-X, a strong detector for encoding explanations.

This figure provides a visual overview of the paper’s contributions. It illustrates the process of producing explanations, evaluating their quality, and identifying the phenomenon of ’encoding.’ Encoding explanations achieve high predictive power not solely from their input values but also from the selection process itself, creating a disconnect between the explanation’s apparent and actual informativeness. The figure highlights the development of STRIPE-X, a novel strong detector designed to identify and resolve encoding issues, classifying existing evaluation methods as non-detectors, weak detectors, and strong detectors to illustrate its novelty.

More on tables

This table presents the results of evaluating different explanation methods (ROAR, EVAL-X, and STRIPE-X) on an image recognition task. The methods are evaluated based on their ability to correctly identify encoding explanations. The results show that STRIPE-X outperforms the other methods in detecting encoding explanations, while ROAR fails to detect encoding and EVAL-X only weakly detects it.

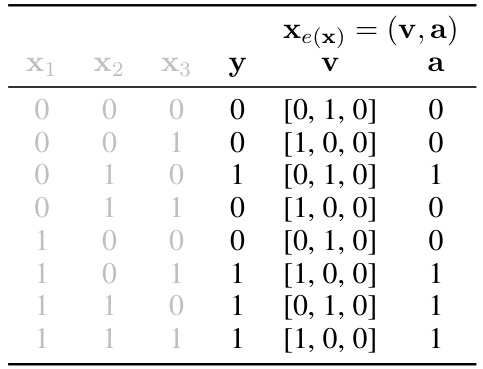

This table shows all possible values of inputs (X1, X2, X3), label (y), selection (v), and explanation values (a) for the DGP in equation (24) described in section B.2 of the paper. It illustrates how an encoding explanation can conceal the control flow input (x3) that determines which of the first two features predicts the label, highlighting the problem of encoding in explanations.

This table shows the probability distribution of the label (y) given different combinations of inputs (x1, x2, x3) for the data generating process (DGP) defined in equation (3) of the paper. The key feature is that the probability of y=1 is dependent on the value of x3; if x3=1, the probability is influenced by x1, and if x3=0, it’s influenced by x2. This illustrates the encoding phenomenon where the selection (x3) affects the values (x1, x2) of what predicts the label.

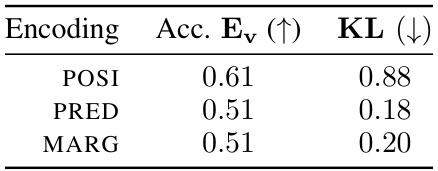

This table presents results from an experiment evaluating three types of encoding explanations: position-based (POSI), prediction-based (PRED), and marginal (MARG). For each encoding type, the accuracy of predicting the selection (Ev) given the values (xv) is shown (Acc.), along with the increase in the predictability of y given xv and Ev (Ev ↑), and the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the distributions q(y|xv, Ev=1) and q(y|xv, Ev=0), which measures the information gain from knowing Ev. Lower KL values indicate that Ev provides less additional information about y given xv, therefore suggesting non-encoding. The results demonstrate that all three encoding types exhibit characteristics of encoding, as indicated by Acc. < 1 and KL > 0, aligning with Lemma 1 in the paper.

Full paper#