TL;DR#

Deep learning models, valuable assets, are vulnerable to model extraction attacks which copy the model’s parameters. Previous attacks were slow and inefficient for larger models. This paper addresses the challenges associated with extracting parameters from deep learning models trained on standard benchmark datasets.

The authors optimized extraction strategies, focusing on sign extraction. They identified and addressed methodological shortcomings in previous studies, proposing robust benchmarking techniques. Their improvements include unified codebase for systematic evaluation, identifying “easy” and “hard” neurons to optimize extraction, and identifying weight, not weight signs, as the bottleneck. These optimizations resulted in significant speed improvements of up to 14.8 times. This work challenges established understanding of model extraction, offering new and efficient methods, and proposes robust benchmarking strategies for future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it significantly accelerates the process of high-fidelity model extraction, a critical concern in protecting intellectual property and data security. By identifying and addressing previous methodological limitations and optimizing extraction strategies, it opens new avenues for research in robust model protection and attack methodologies. Its findings directly challenge existing assumptions about extraction bottlenecks, prompting reevaluation and advancement of current research on model security.

Visual Insights#

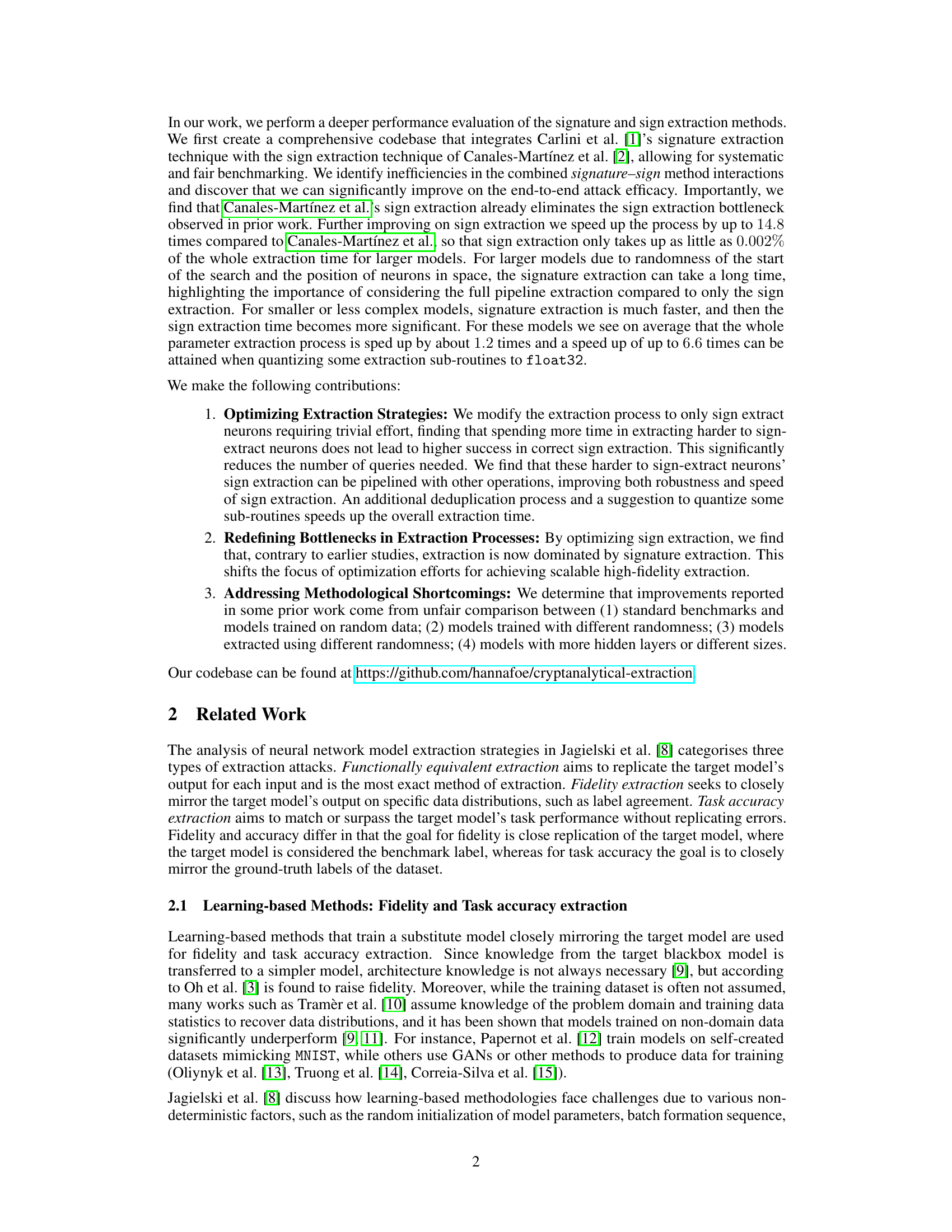

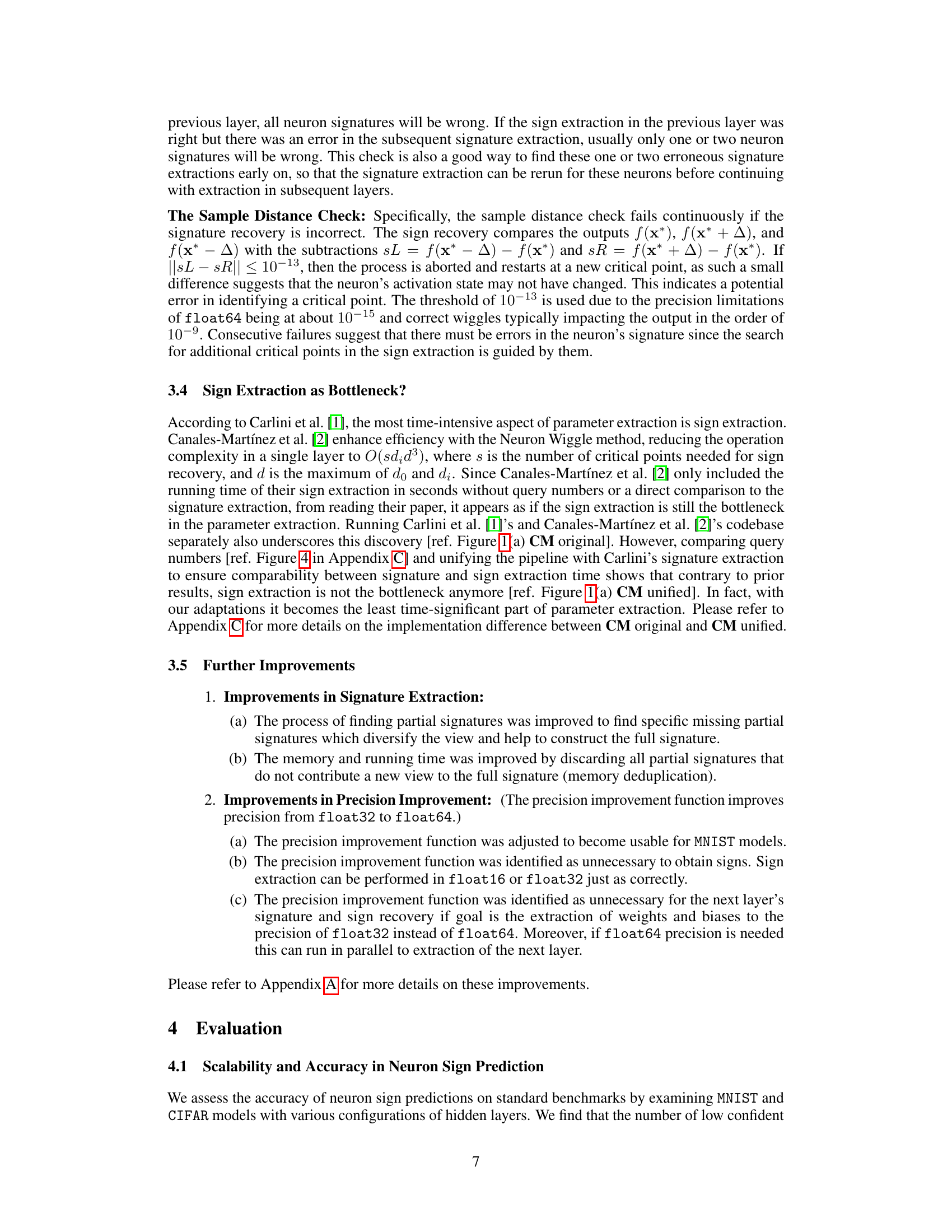

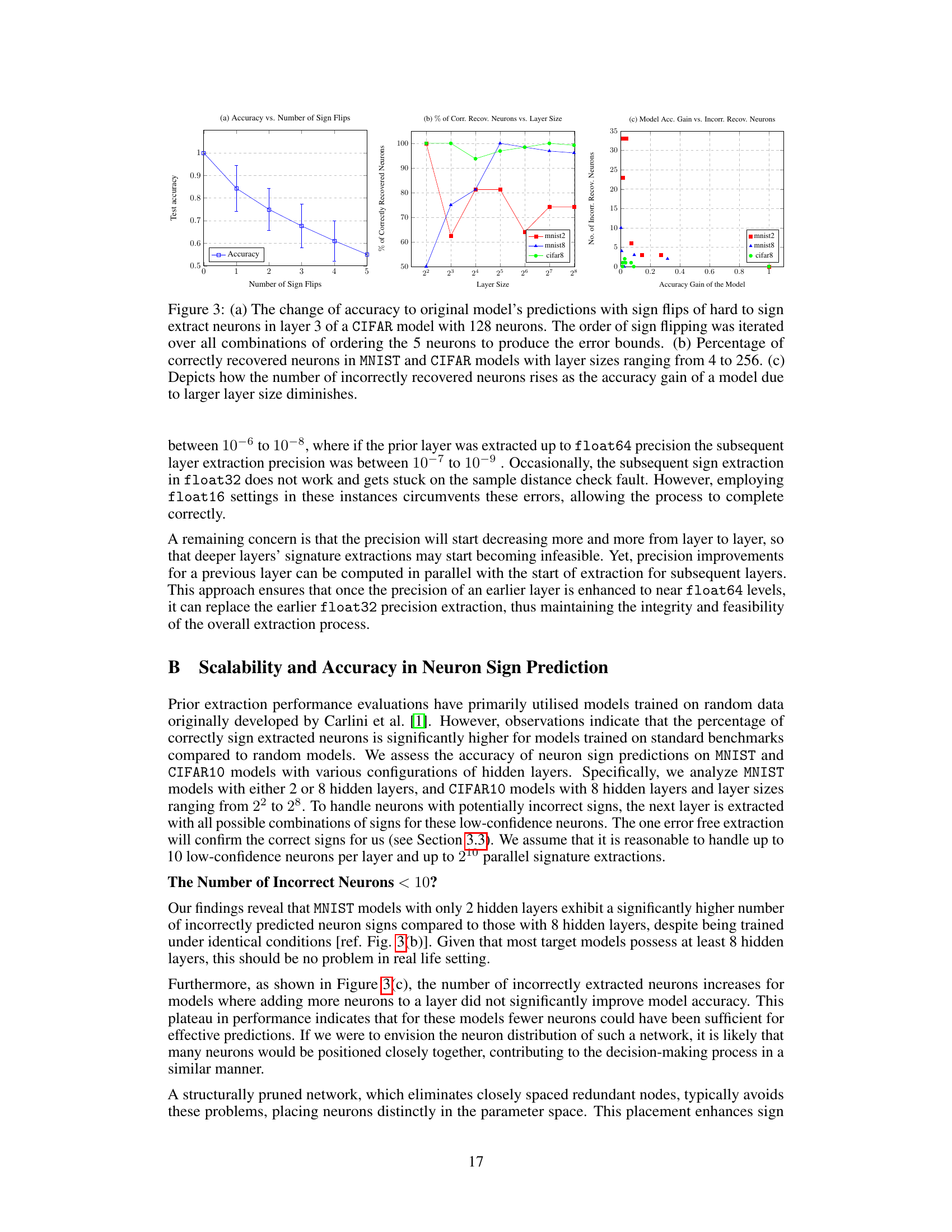

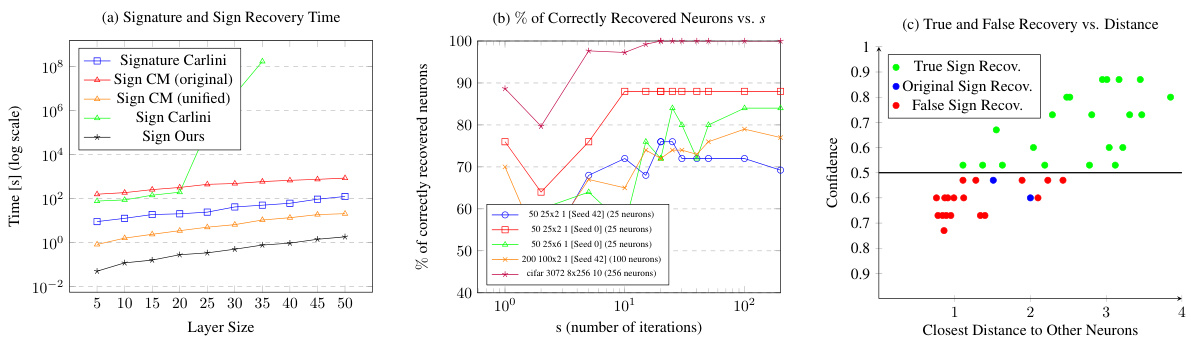

🔼 This figure compares the time and accuracy of different sign extraction methods. (a) shows the running time of signature and sign extraction methods. (b) shows the percentage of correctly recovered neurons as a function of the number of sign extractions. (c) shows the confidence of sign recovery as a function of the distance to other neurons.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) Compares the running times for Carlini's signature extraction versus Carlini's sign extraction, Canales-Martinez (CM)'s sign extraction with s = 200 setting in the original implementation and in the unified implementation and Our sign extraction with s = 15 setting. The tests are across ten models with increasing layer sizes from 10 -5 -5 -1 to 100 – 50 – 50 – 1, detailing times for a single layer's extraction in a non-parallelised setting. (b) Depicts how the average percentage of correctly recovered neurons in a layer changes when the number of sign extractions s changes. Raising the number of sign extractions s to more than 15 does not significantly raise the number of correctly recovered neurons. (c) Graph showing confidences of sign recovery when a hard neuron's euclidean distance to its neighbours is manipulated. These results are on hard to sign extract neurons 25 and 26 of an MNIST trained 784-32x8-1 model extracted with seed 42. The confidence metric scales from 1 to 0.5 first on the confidence of false sign recovery, which is equivalent to 0 to 0.5 of confidence in true sign recovery and then from 0.5 to 1 on the confidence of true sign recovery, resulting in the scale going from 1 0.5-1.

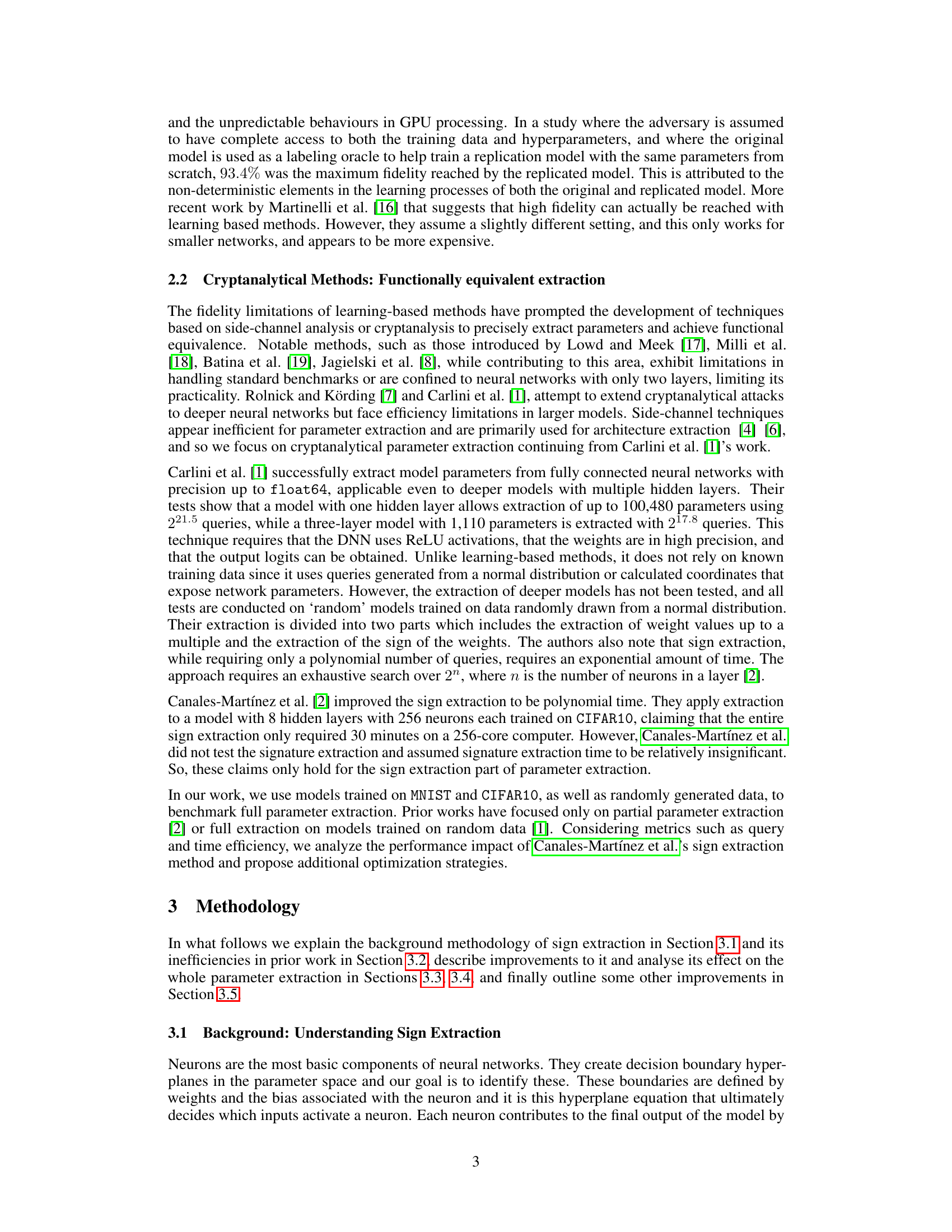

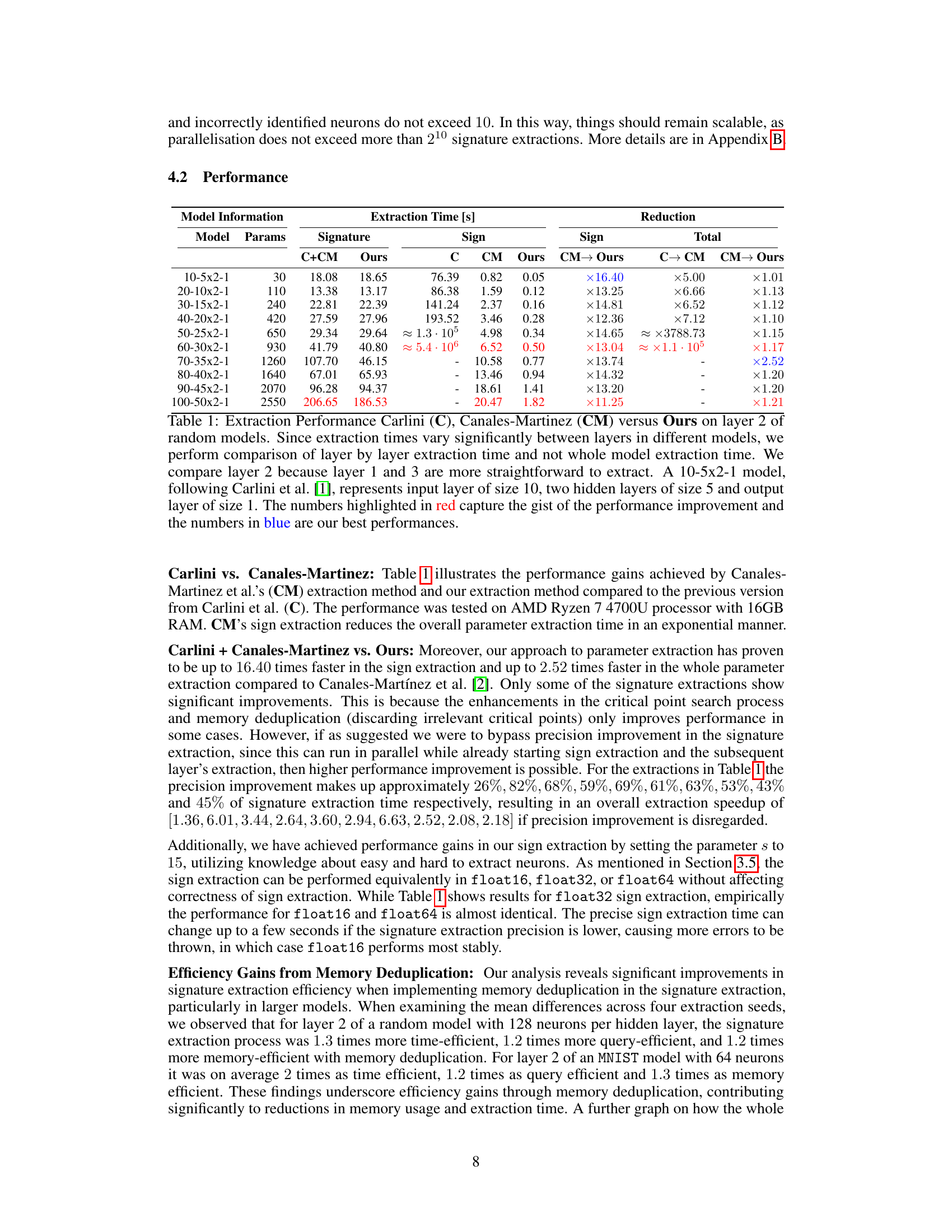

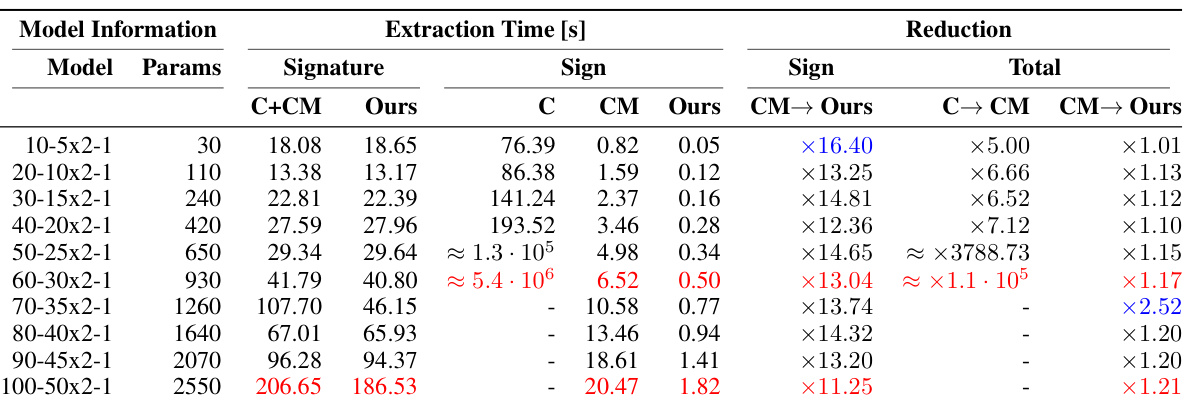

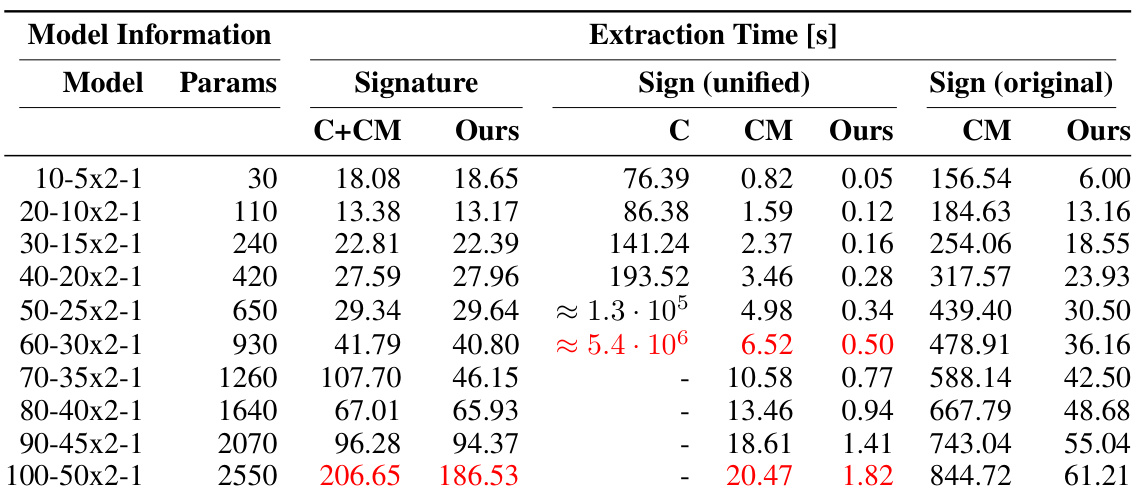

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different methods for extracting model parameters: Carlini’s method, Canales-Martinez’s method, and the authors’ improved method. It shows the extraction time for each method on layer 2 of several random models with varying sizes. The results demonstrate the significant speedup achieved by the authors’ method in terms of both signature and sign extraction.

read the caption

Table 1: Extraction Performance Carlini (C), Canales-Martinez (CM) versus Ours on layer 2 of random models. Since extraction times vary significantly between layers in different models, we perform comparison of layer by layer extraction time and not whole model extraction time. We compare layer 2 because layer 1 and 3 are more straightforward to extract. A 10-5x2-1 model, following Carlini et al. [1], represents input layer of size 10, two hidden layers of size 5 and output layer of size 1. The numbers highlighted in red capture the gist of the performance improvement and the numbers in blue are our best performances.

In-depth insights#

High-Fidelity Extraction#

High-fidelity model extraction poses a significant threat to the confidentiality of deep learning models. This technique aims to precisely replicate a target model’s functionality, often by cleverly querying it and analyzing the responses. The core challenge lies in balancing the need for sufficient data to accurately reconstruct the model’s internal parameters with the inherent limitations and vulnerabilities introduced by querying mechanisms. Cryptanalytic approaches, while precise, often face computational bottlenecks, especially when dealing with larger, deeper models. Optimizing extraction strategies and identifying the actual bottlenecks, such as weight extraction rather than just sign extraction, are critical for improving efficiency. This requires sophisticated algorithmic enhancements, like the Neuron Wiggle method, along with clever resource management and parallelization techniques. Methodological rigor is crucial, as demonstrated by the need for robust benchmarking, which addresses unfair comparisons due to factors like dataset randomness or model architecture. Future advancements in high-fidelity extraction are likely to focus on overcoming these challenges through enhanced algorithmic efficiency, addressing the issue of computationally complex sign extractions, and exploring novel query strategies that are less prone to exploitation. Ultimately, research in this area must consider ethical implications and potential misuse of this potent technology.

Sign Extraction Speedup#

Sign extraction, a critical step in high-fidelity model extraction, has been significantly sped up. The core innovation involves strategically focusing on neurons that are easier to extract, significantly reducing computational effort. This optimization, coupled with algorithmic improvements and efficient parallelization, achieves up to a 14.8x speedup compared to prior methods. While prior assumptions considered weight sign extraction the bottleneck, this work reveals that weight extraction itself is actually the primary limiting factor. The findings highlight that carefully optimizing extraction strategies across all phases of the process, rather than solely focusing on a single component (sign extraction), leads to the most substantial improvements. The overall efficiency gains impact various model sizes and architectures, demonstrating the scalability and robustness of this refined approach for extracting complex deep learning models.

Bottleneck Redefined#

The concept of a ‘Bottleneck Redefined’ in the context of a model extraction research paper likely refers to a significant shift in understanding the critical limitations of the process. Previous work may have identified a specific stage, such as sign extraction, as the primary bottleneck, implying it was the most time-consuming and difficult part. However, this section would argue that new optimizations or algorithmic improvements have rendered the previously identified bottleneck less critical. This could be due to novel approaches substantially accelerating that step. The new bottleneck then shifts to another, previously less significant, stage in the model extraction pipeline, such as signature extraction or other aspects of the cryptanalytic method. This redefinition is crucial because it alters the focus of future research efforts. Instead of concentrating resources on improving the formerly limiting phase, researchers would now concentrate on overcoming the newly identified bottleneck to further enhance the efficacy of model extraction attacks. This revised perspective potentially necessitates the exploration of different computational tools, strategies, and theoretical frameworks to overcome this newly revealed limitation and achieve higher fidelity and efficiency in future model extraction research.

Robust Benchmarking#

Robust benchmarking in model extraction research is crucial for ensuring reliable and meaningful comparisons between different methods. A robust benchmark should carefully consider various factors that can influence the performance of extraction attacks. These factors include dataset characteristics (e.g., data distribution, size, complexity), model architecture (e.g., depth, width, activation functions), training methods (e.g., hyperparameters, optimization algorithms), and attack parameters (e.g., number of queries, computational resources). A good benchmark should also address methodological inconsistencies found in prior research, such as differences in model training procedures, evaluation metrics, and experimental setup, leading to unfair comparisons. Standardizing evaluation metrics and ensuring a fair comparison across different techniques are critical to advancing the field. Additionally, transparency in benchmark design is essential; including details of data preprocessing, model training, and attack implementation is crucial for reproducibility. This will aid future research in creating more reliable comparisons and improving the robustness of model extraction techniques.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore improving the efficiency of signature extraction, perhaps by developing more sophisticated methods for identifying and isolating critical points or by utilizing advanced machine learning techniques to accelerate the process. Another avenue would involve investigating the robustness of model extraction techniques against various defenses, including adversarial training, differential privacy, and other techniques designed to protect model confidentiality. The development of more effective and efficient countermeasures against model extraction attacks would be highly valuable. Furthermore, research into model extraction attacks on more complex models with various architectures and training procedures would be beneficial, enabling a broader understanding of the vulnerabilities and limitations of current defense mechanisms. Finally, a holistic evaluation framework for comparing model extraction attacks and defenses is needed to provide a comprehensive understanding of their strengths and weaknesses in different settings and to accelerate progress in this important field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

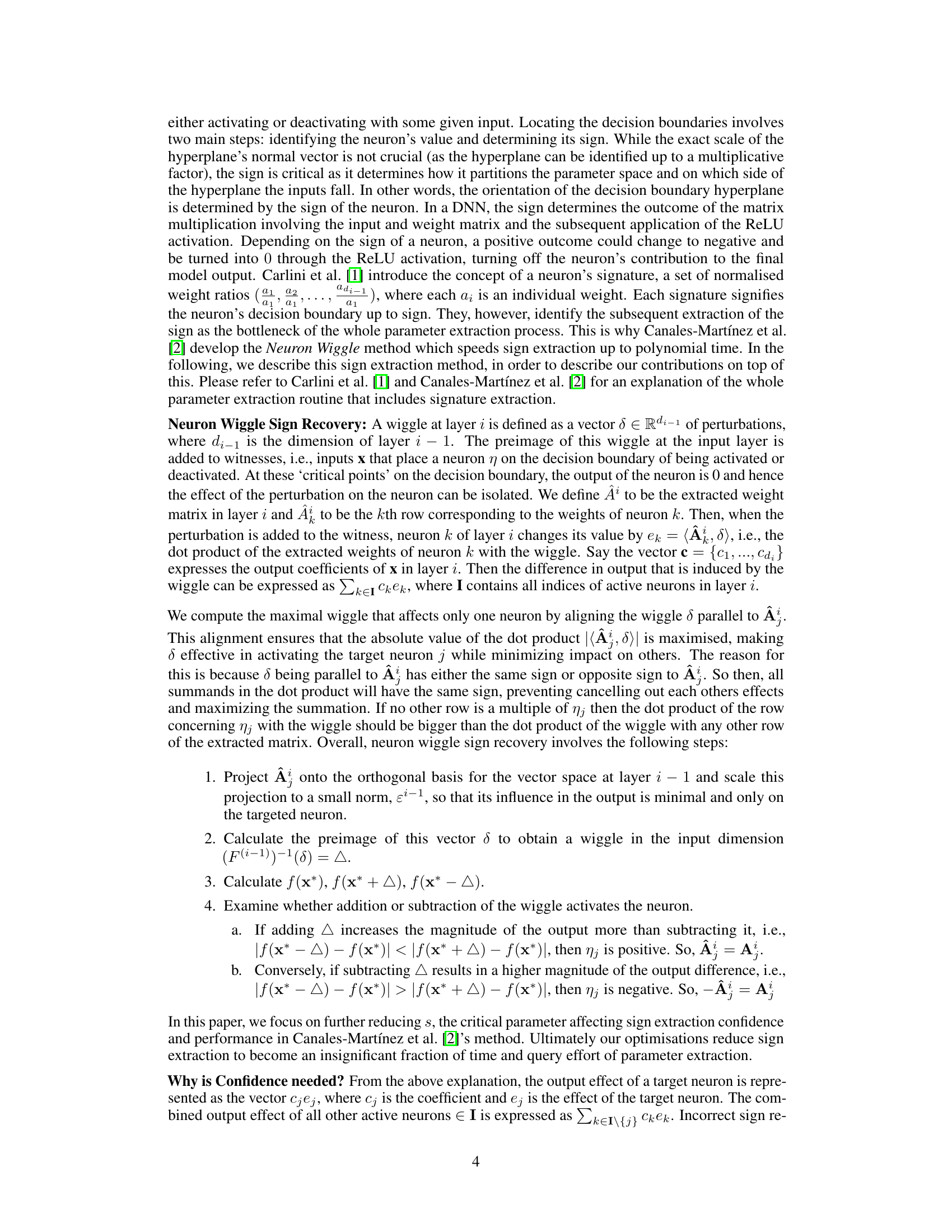

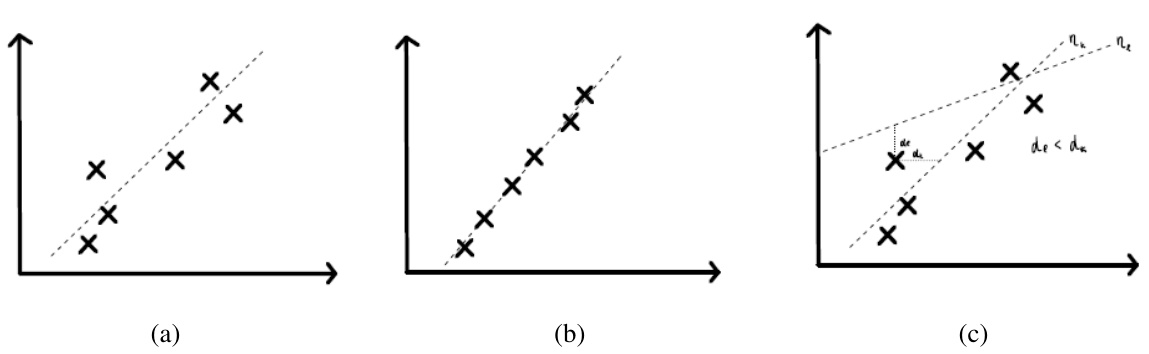

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of precision improvement in the signature extraction process. (a) shows the initial state with imprecise critical points. (b) shows the improved state after precision improvement, where the critical points are more accurate. (c) shows an example of when the precision improvement process fails, resulting in a critical point being assigned to the wrong neuron.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) Neuron and Critical Points before Precision Improvement (b) Neuron and Critical Points after Precision Improvement (c) An Example of When Precision Improvement Fails. Neuron ηι is close to the critical point than η and so this critical point is converted to a critical point for η instead of for nk.

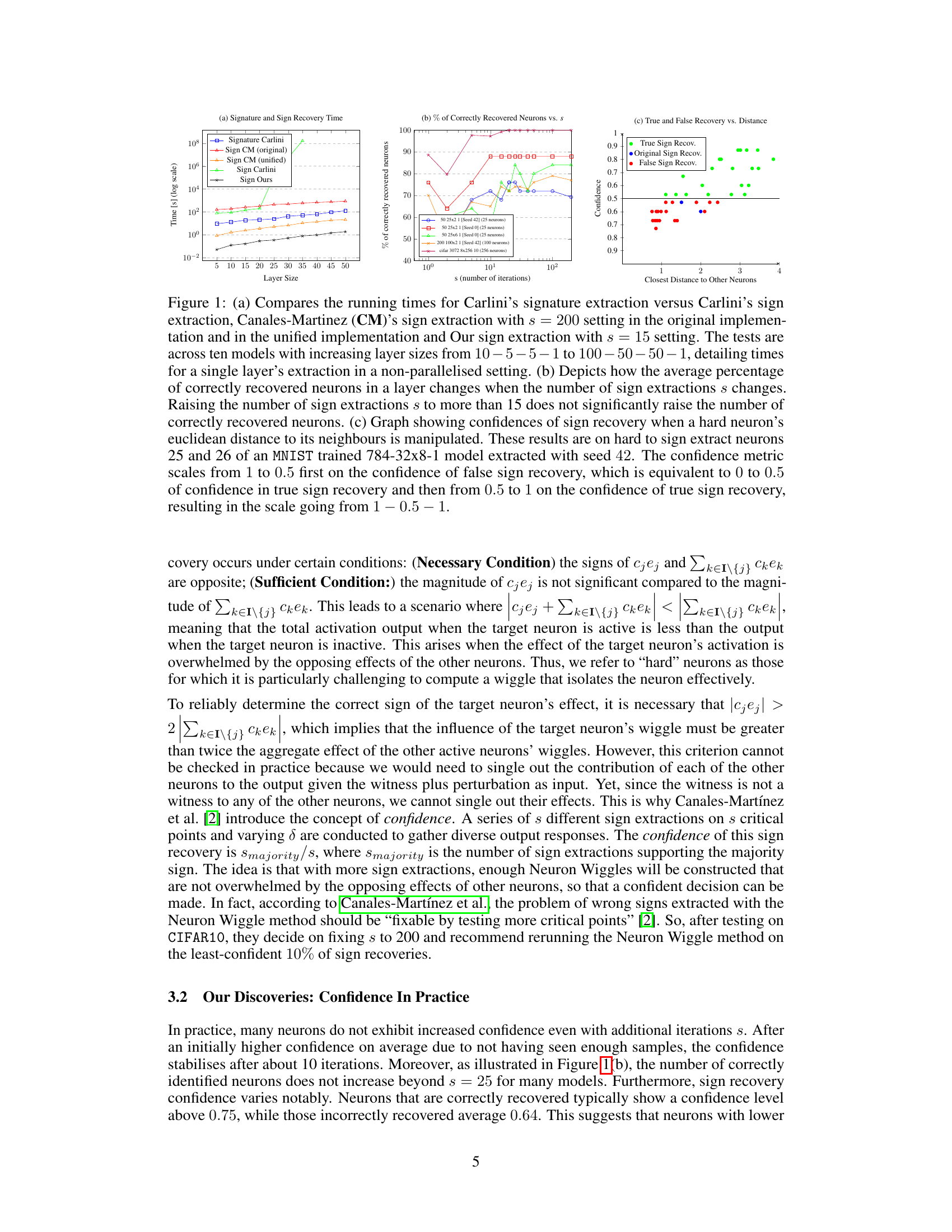

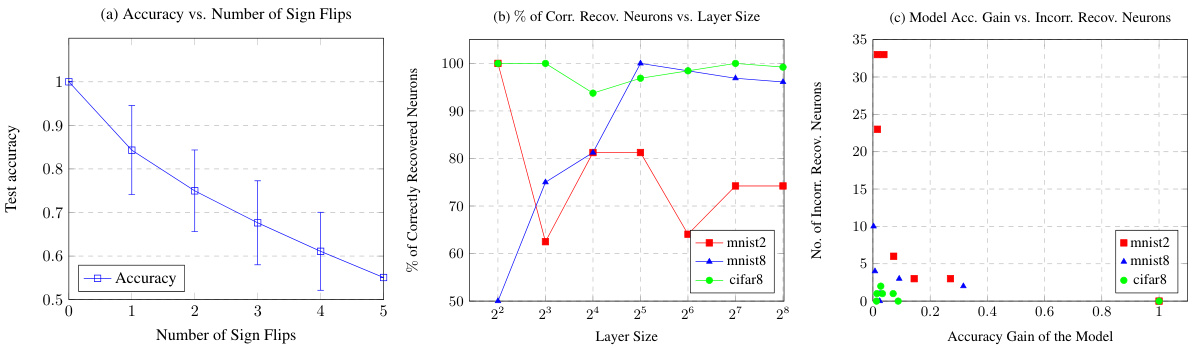

🔼 This figure shows three graphs that analyze the impact of incorrect neuron sign recovery. Graph (a) demonstrates how flipping the signs of hard-to-extract neurons in a CIFAR model affects the test accuracy. (b) compares the percentage of correctly recovered neurons in MNIST and CIFAR models with varying layer sizes. Finally, (c) illustrates the relationship between the accuracy gain achieved by increasing layer size and the number of incorrectly recovered neurons. This figure helps to understand the impact of extraction errors and the scalability of the extraction method.

read the caption

Figure 3: (a) The change of accuracy to original model's predictions with sign flips of hard to sign extract neurons in layer 3 of a CIFAR model with 128 neurons. The order of sign flipping was iterated over all combinations of ordering the 5 neurons to produce the error bounds. (b) Percentage of correctly recovered neurons in MNIST and CIFAR models with layer sizes ranging from 4 to 256. (c) Depicts how the number of incorrectly recovered neurons rises as the accuracy gain of a model due to larger layer size diminishes.

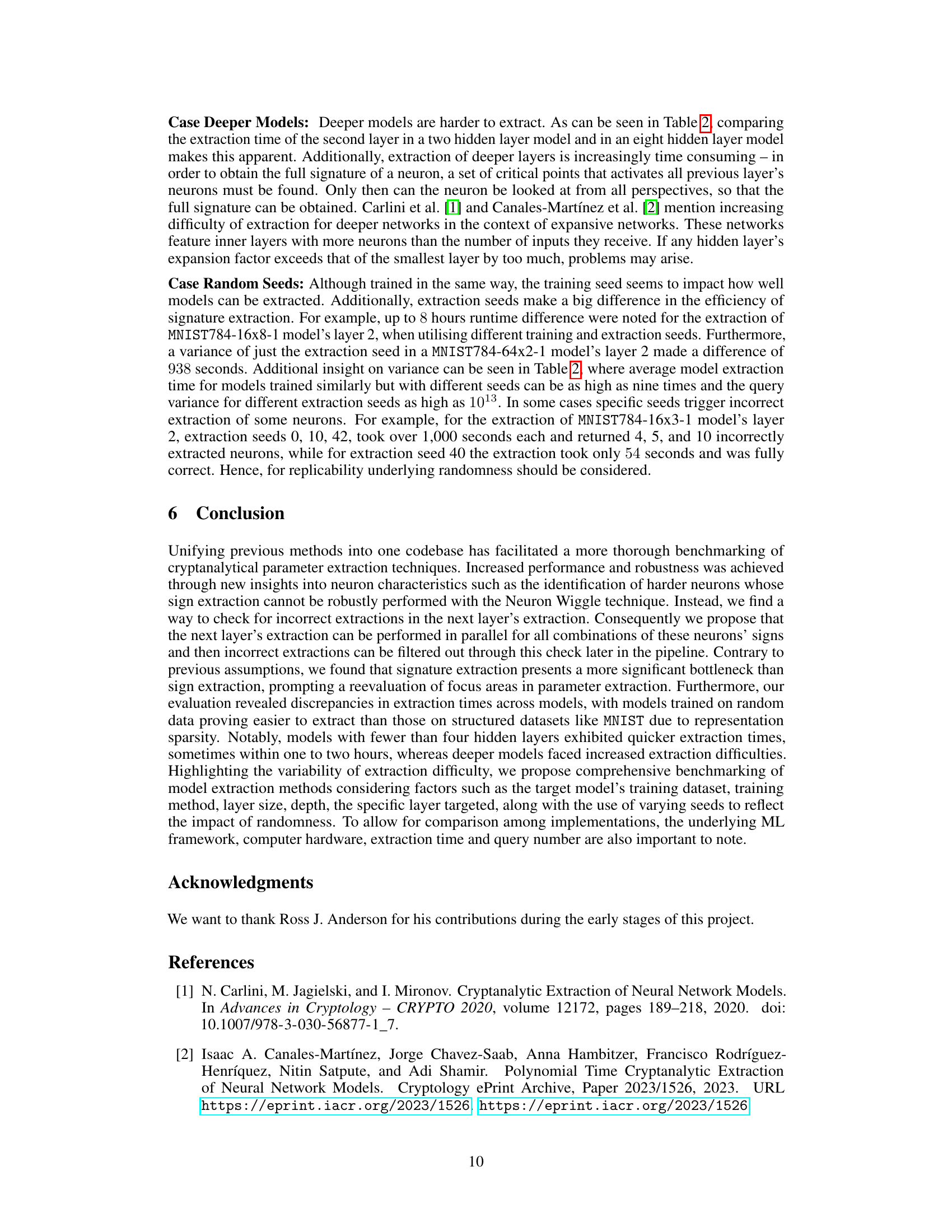

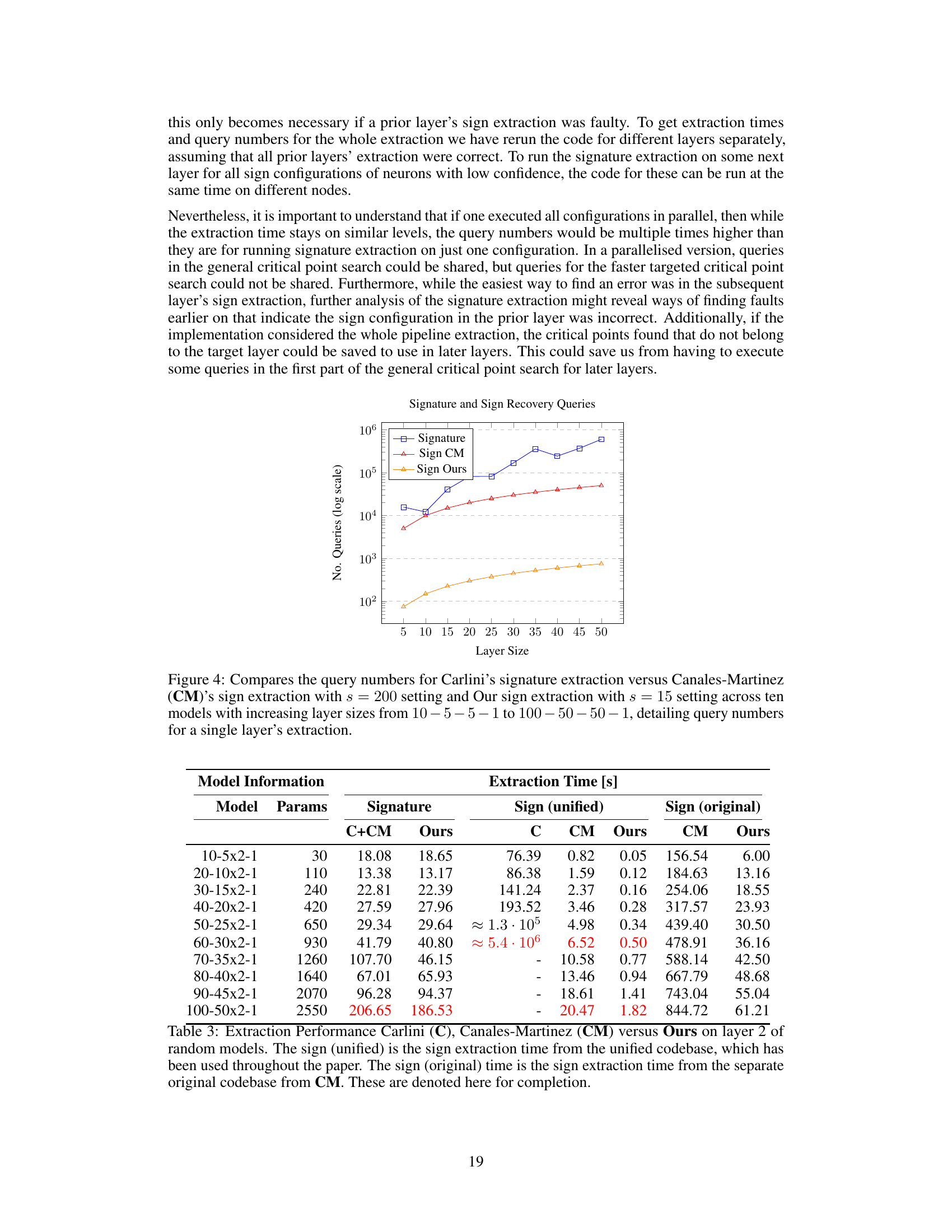

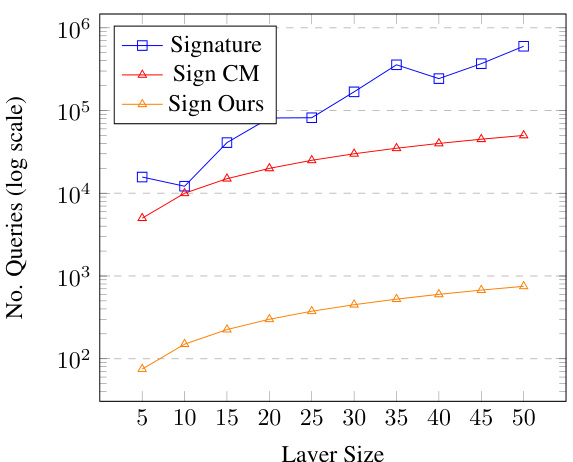

🔼 The figure compares the number of queries required for signature and sign extraction methods across different model sizes. It shows the query counts for Carlini’s original signature extraction method, Canales-Martinez’s sign extraction (with parameter s=200), and the authors’ improved sign extraction method (with s=15). The x-axis represents the size of a single layer in the model, and the y-axis shows the number of queries (on a logarithmic scale). The results demonstrate the significant reduction in queries achieved by the authors’ optimized approach compared to previous methods, particularly for larger model sizes.

read the caption

Figure 4: Compares the query numbers for Carlini’s signature extraction versus Canales-Martinez (CM)’s sign extraction with s = 200 setting and Our sign extraction with s = 15 setting across ten models with increasing layer sizes from 10 - 5 - 5 - 1 to 100 – 50 – 50 – 1, detailing query numbers for a single layer’s extraction.

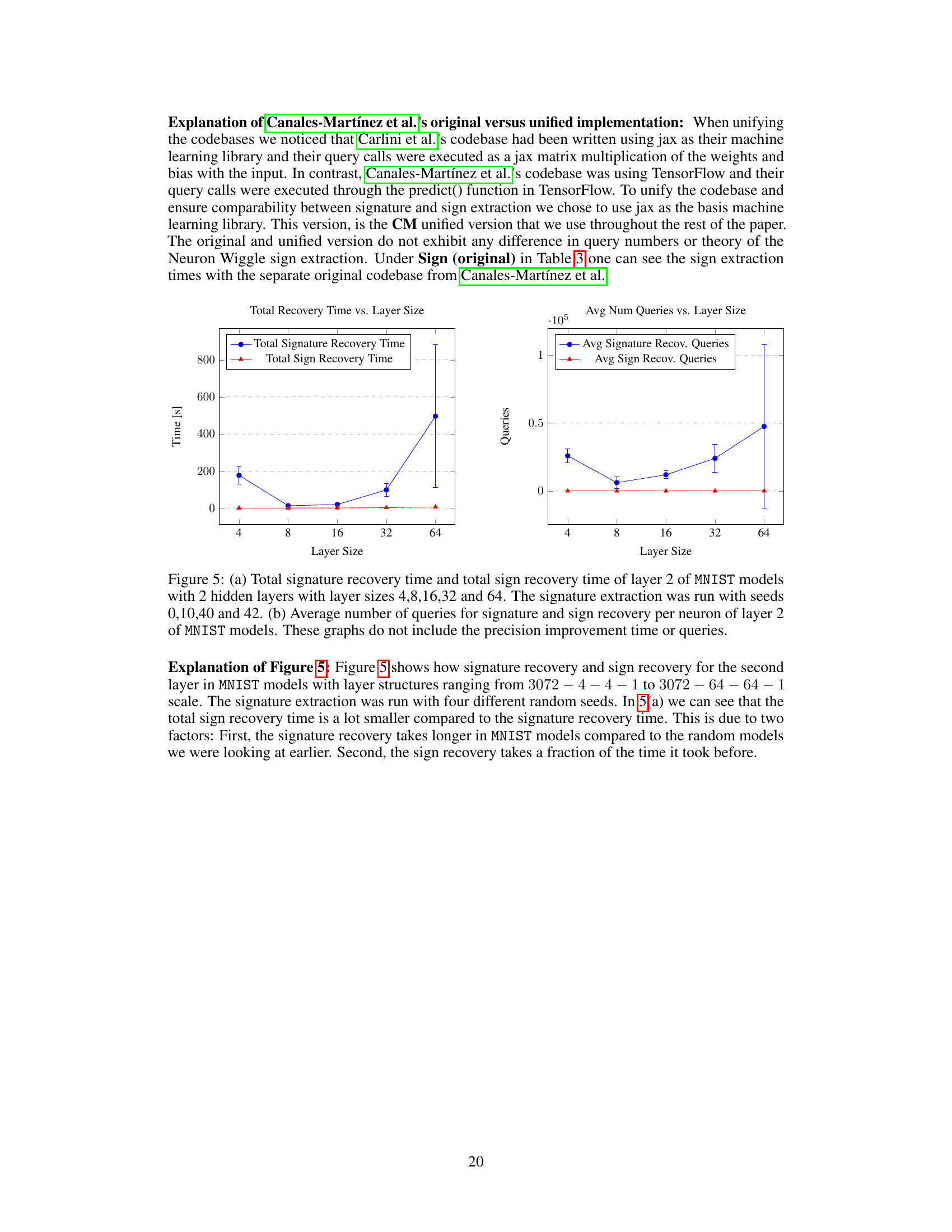

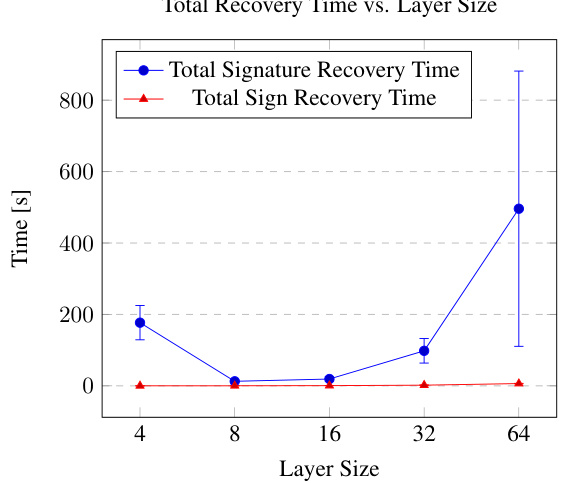

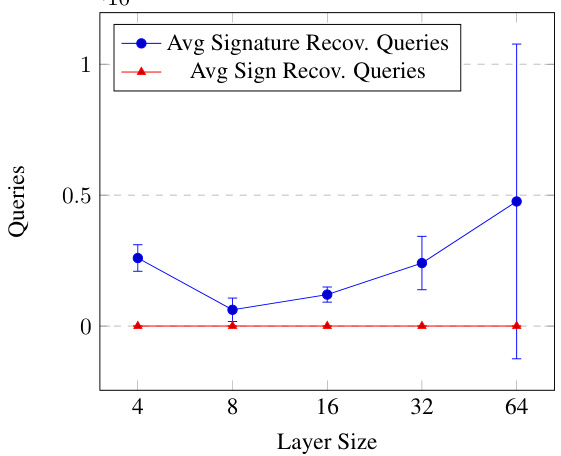

🔼 This figure compares the total time and query numbers used for signature and sign recovery in MNIST models with varying layer sizes. Part (a) shows that sign recovery time is significantly less than signature recovery time, particularly as the layer size increases. Part (b) shows that the average number of queries for both sign and signature recovery increase with layer size, but the increase for sign recovery is more gradual.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Total signature recovery time and total sign recovery time of layer 2 of MNIST models with 2 hidden layers with layer sizes 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64. The signature extraction was run with seeds 0, 10, 40 and 42. (b) Average number of queries for signature and sign recovery per neuron of layer 2 of MNIST models. These graphs do not include the precision improvement time or queries.

🔼 This figure compares the total time and number of queries required for signature and sign recovery in layer 2 of MNIST models. The models have two hidden layers with varying sizes (4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 neurons). The signature recovery time is significantly longer than sign recovery time. The number of queries for signature recovery also increases much more rapidly than the queries needed for sign recovery as the layer size increases.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Total signature recovery time and total sign recovery time of layer 2 of MNIST models with 2 hidden layers with layer sizes 4,8,16,32 and 64. The signature extraction was run with seeds 0,10,40 and 42. (b) Average number of queries for signature and sign recovery per neuron of layer 2 of MNIST models. These graphs do not include the precision improvement time or queries.

More on tables

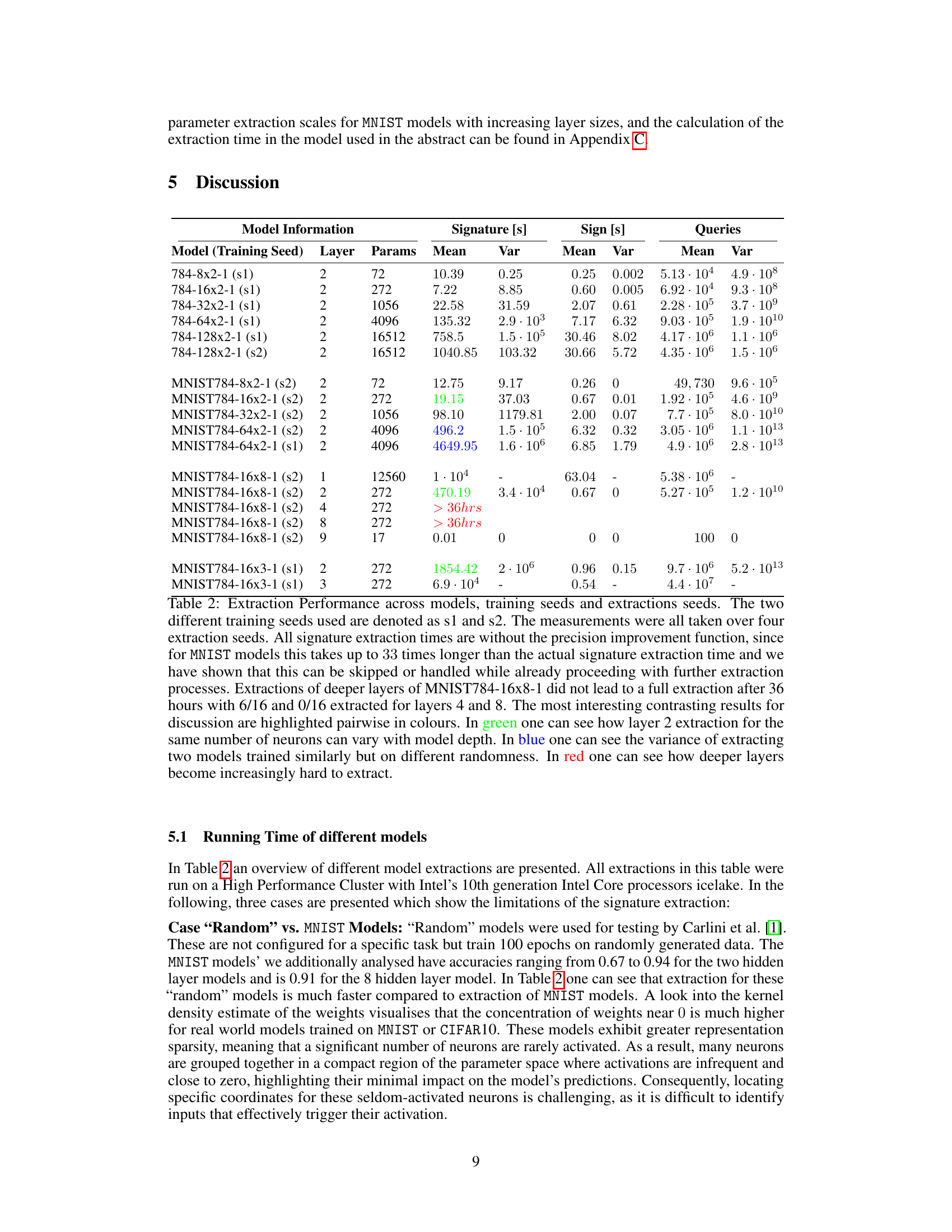

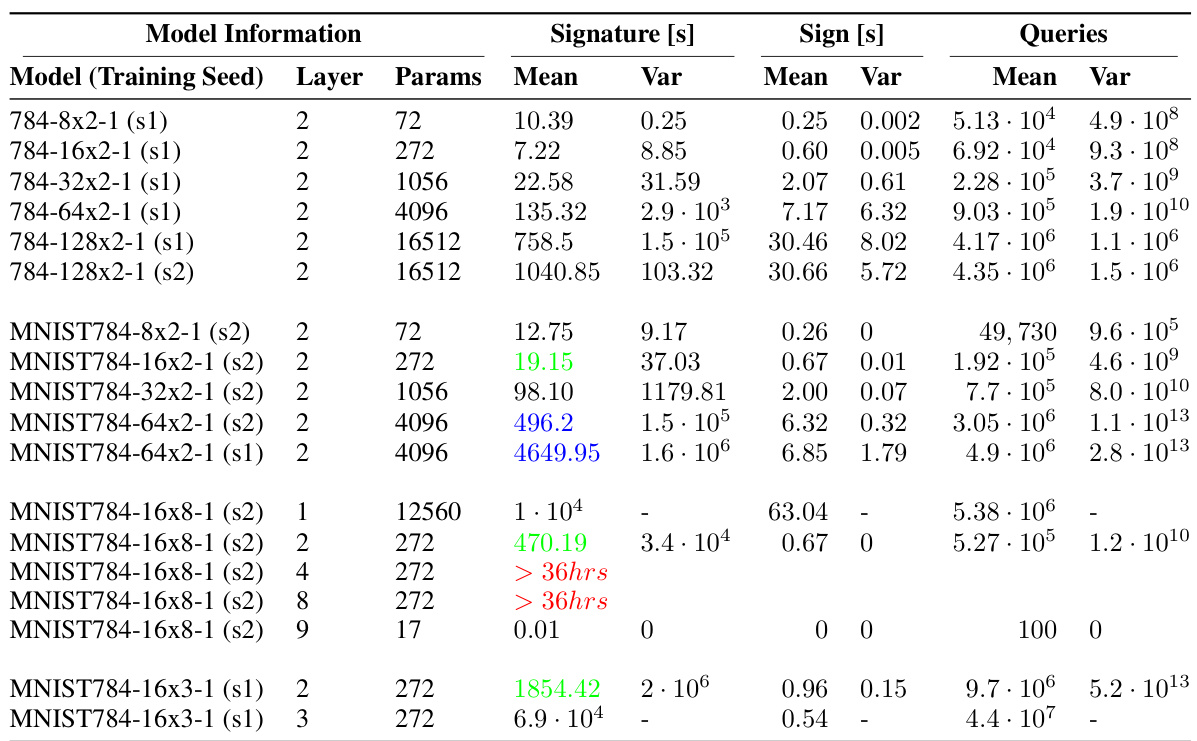

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive performance evaluation of the model extraction process across various models, training seeds, and extraction seeds. It highlights the impact of different factors, such as model architecture (layer depth and size), randomness in training and extraction, on the efficiency and success of the extraction. The table contrasts extraction times and query numbers for different layer configurations, showing variations in performance based on these factors. Key performance aspects are shown, including the mean and variance of signature and sign extraction times and queries.

read the caption

Table 2: Extraction Performance across models, training seeds and extractions seeds. The two different training seeds used are denoted as s1 and s2. The measurements were all taken over four extraction seeds. All signature extraction times are without the precision improvement function, since for MNIST models this takes up to 33 times longer than the actual signature extraction time and we have shown that this can be skipped or handled while already proceeding with further extraction processes. Extractions of deeper layers of MNIST784-16x8-1 did not lead to a full extraction after 36 hours with 6/16 and 0/16 extracted for layers 4 and 8. The most interesting contrasting results for discussion are highlighted pairwise in colours. In green one can see how layer 2 extraction for the same number of neurons can vary with model depth. In blue one can see the variance of extracting two models trained similarly but on different randomness. In red one can see how deeper layers become increasingly hard to extract.

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different model extraction methods: the original method by Carlini et al. [1], the improved method by Canales-Martinez et al. [2], and the authors’ new method. The comparison focuses on layer 2 of random models with varying sizes. Extraction time for signature, sign (unified), and sign (original) are shown and compared. Highlighted values denote significant improvements. The table also describes the model structure using a notation that specifies the input and output layer sizes, and the number of hidden layers and their sizes.

read the caption

Table 1: Extraction Performance Carlini (C), Canales-Martinez (CM) versus Ours on layer 2 of random models. Since extraction times vary significantly between layers in different models, we perform comparison of layer by layer extraction time and not whole model extraction time. We compare layer 2 because layer 1 and 3 are more straightforward to extract. A 10-5x2-1 model, following Carlini et al. [1], represents input layer of size 10, two hidden layers of size 5 and output layer of size 1. The numbers highlighted in red capture the gist of the performance improvement and the numbers in blue are our best performances.

Full paper#