TL;DR#

Low-shot object counting, estimating object numbers from few or no examples, faces challenges like overgeneralization and inaccurate localization using surrogate losses. Existing approaches either use density estimation lacking explainability, or detection-based methods underperforming in density estimation and prone to false positives due to surrogate losses.

GeCo addresses these issues with a novel unified architecture. It employs a dense object query for robust prototype generalization, avoiding overfitting. A new counting loss directly optimizes detection, enhancing accuracy and eliminating density map biases. GeCo significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods in count accuracy and detection, demonstrating its effectiveness in various low-shot scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in low-shot object counting due to its significant improvement over existing methods. GeCo’s unified architecture and novel loss function offer a new state-of-the-art approach, opening avenues for future research in improving accuracy and robustness in challenging scenarios. Its impact extends to applications needing reliable object detection and counting with limited data, such as environmental monitoring and medical imaging.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure compares the performance of GeCo with two other state-of-the-art low-shot object counters, DAVE and CDETR. It highlights GeCo’s improved ability to accurately detect objects, even in challenging scenarios like densely populated regions or those with ambiguous blob-like structures. The figure uses examples of ants and integrated circuits to illustrate the differences in detection accuracy and the added benefit of segmentation provided by GeCo.

read the caption

Figure 1: DAVE [20] predicts object centers (red dots) biased towards blob-like structures, leading to incorrect partial detections of ants (bottom left), while GeCo(ours) addresses this with the new loss (top left). CDETR [19] fails in densely populated regions (bottom right), while GeCo addresses this with the new dense query formulation by prototype generalization (top right). Exploiting the SAM backbone, GeCo delivers segmentations as well. Exemplars are denoted in blue.

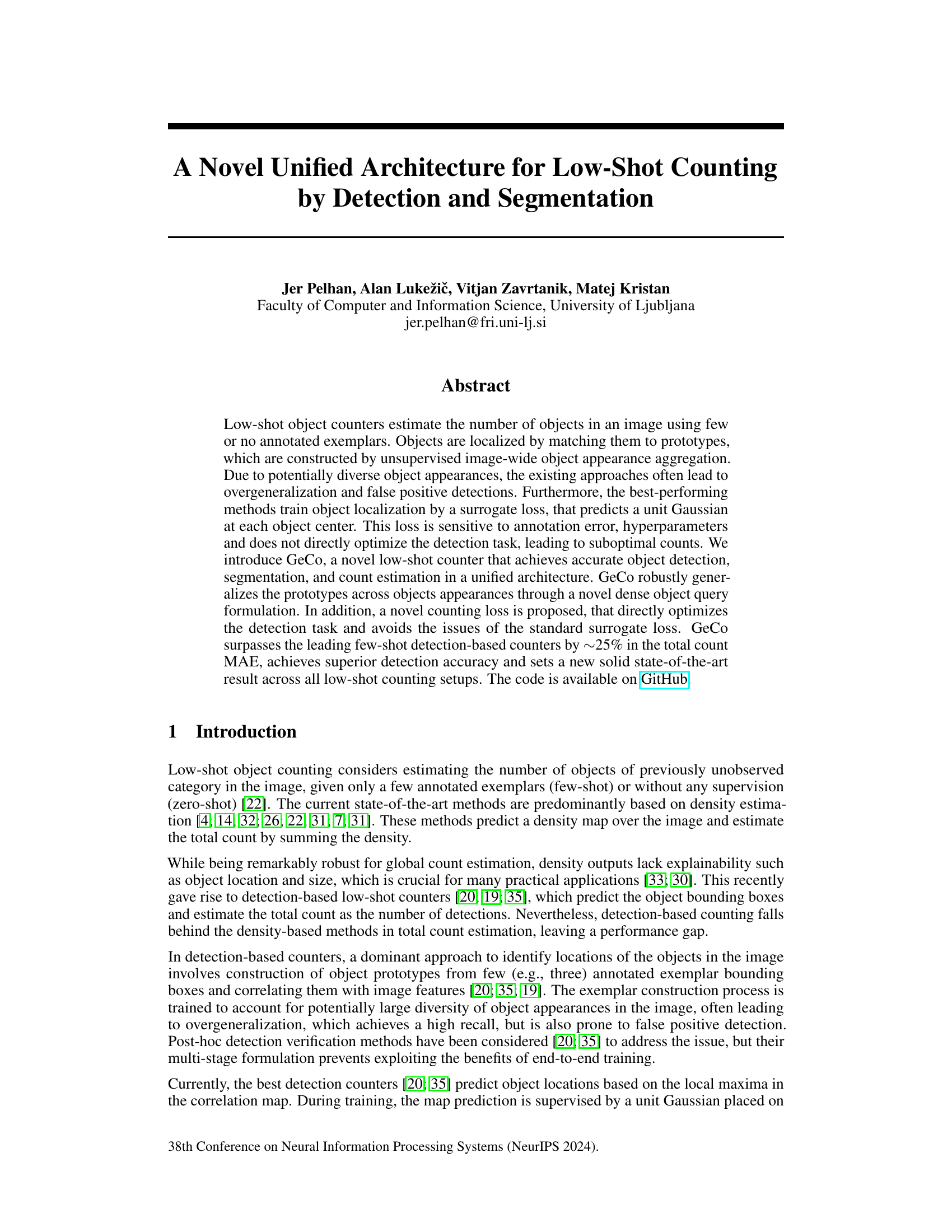

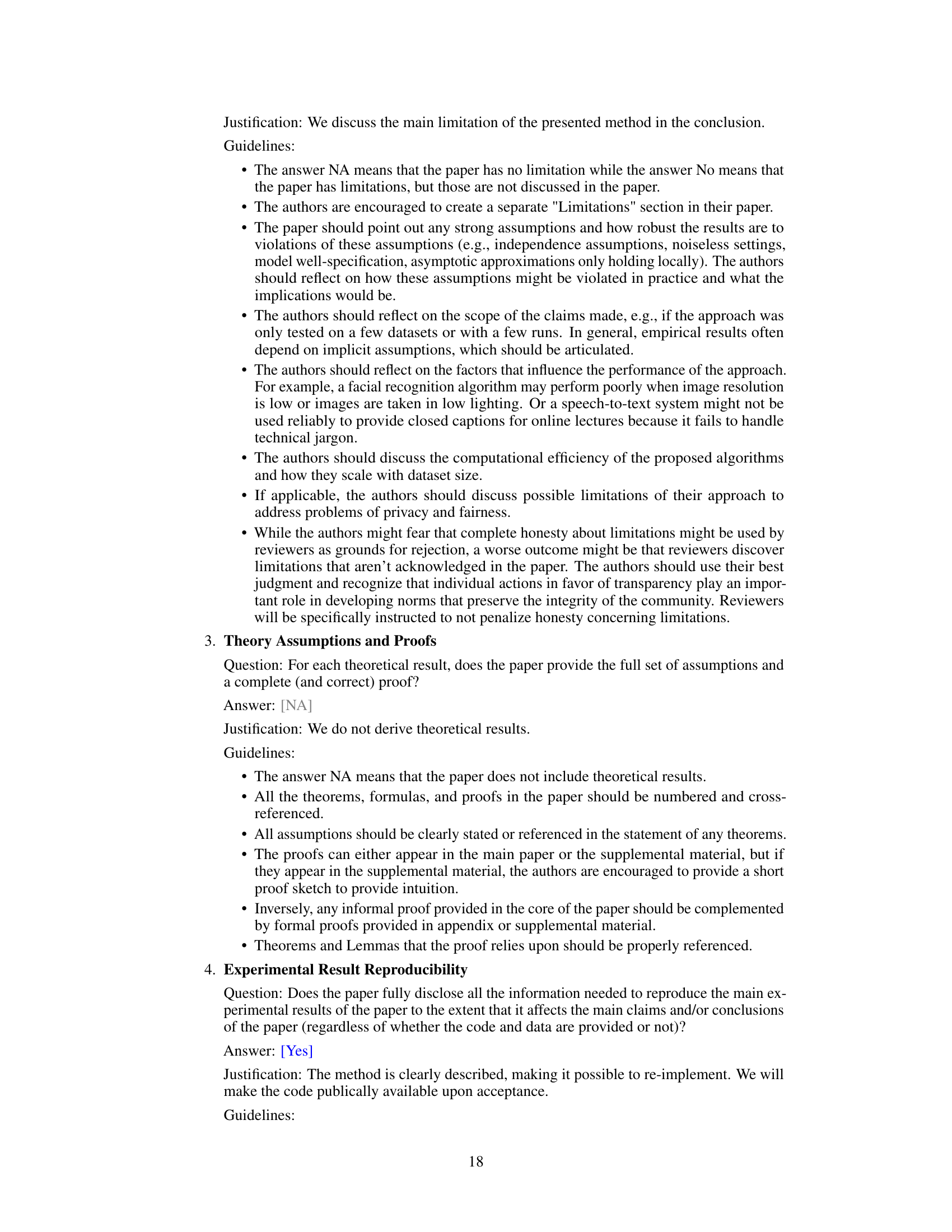

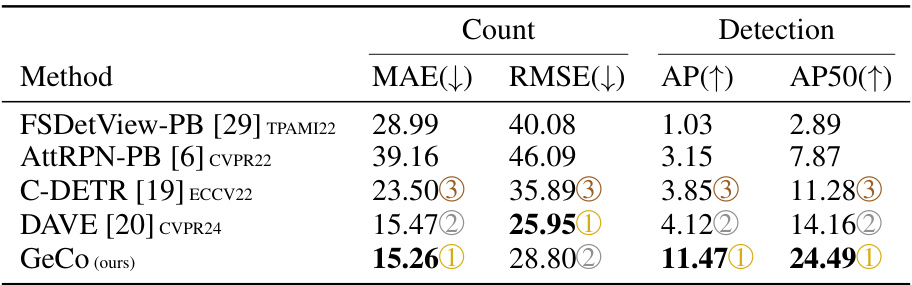

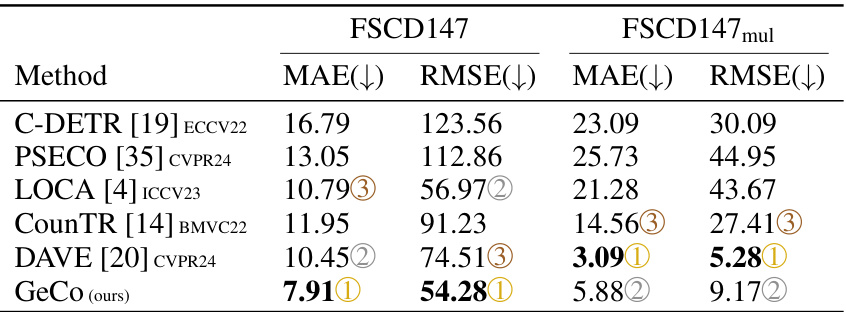

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various low-shot object counting methods on the FSCD147 dataset. It’s divided into density-based methods (which estimate counts from density maps) and detection-based methods (which locate objects and count them). The table shows the performance of each method using several metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Precision (AP), and Average Precision at IoU=50 (AP50). Lower MAE and RMSE values indicate better counting accuracy, while higher AP and AP50 values represent better object detection.

read the caption

Table 1: Few-shot density-based methods (top part) and detection-based methods (bottom part) performances on the FSCD147 [19].

In-depth insights#

Low-Shot Counting#

Low-shot counting tackles the challenge of accurately estimating the number of objects in an image when only a limited number of annotated examples are available. This contrasts with traditional object counting methods that require extensive training data. The core difficulty lies in generalizing object appearance from few examples to unseen instances within diverse scenes. Early approaches often relied on density estimation, predicting a density map and summing the density for a total count. However, these methods lack the explainability of detection-based approaches, which aim to localize objects individually. The paper’s focus is on improving detection-based methods by addressing limitations such as overgeneralization and reliance on surrogate loss functions for localization. A unified architecture that directly optimizes detection, segmentation and counting is proposed as a major contribution, showcasing improved robustness and accuracy compared to existing methods.

GeCo Architecture#

The GeCo architecture is a novel, single-stage design for low-shot object counting that integrates detection and segmentation. Its core innovation lies in a dense object query formulation, moving beyond the traditional use of a limited number of prototypes. This allows GeCo to generalize effectively across diverse object appearances, achieving robust performance in densely populated scenes. The architecture leverages a powerful backbone network like SAM for feature extraction, followed by a dense query encoder that generalizes prototypes image-wide. A dense query decoder then processes these queries to predict object locations and segmentation masks. A key contribution is the novel loss function that directly optimizes the detection task, unlike prior methods that rely on surrogate losses. This leads to more precise detections and ultimately a more accurate count. The integration of SAM allows for high-quality segmentation masks as a byproduct, enhancing the overall explainability of the counting process.

Dense Query Design#

A dense query design in object detection aims to improve the accuracy and efficiency of object localization by generating a large number of queries across the entire image, rather than relying on sparsely distributed anchor boxes or region proposals. This approach enhances the model’s capacity to capture subtle variations in object appearances and better handle dense object scenes. A key advantage lies in its ability to avoid prototype overgeneralization, a common issue in low-shot counting, where prototypes become overly broad, resulting in inaccurate detection. Dense query formulations allow for more precise localization by enabling the model to directly learn from the rich information contained in the image-wide distribution of object features. The trade-off lies in increased computational cost due to handling numerous queries; however, this is offset by gains in accuracy and robustness. This technique is particularly beneficial in scenarios with limited labeled data or significant object variations.

Novel Counting Loss#

A novel counting loss function is a crucial part of improving low-shot object counting. The existing surrogate losses, like those predicting a Gaussian at object centers, suffer from sensitivity to annotation errors and hyperparameter choices. A novel approach would directly optimize the detection task, perhaps by using a loss that directly compares the number of detected objects with the ground truth count. This could involve a loss function sensitive to both the number of detections and their spatial accuracy, mitigating issues from false positives. Incorporating a new loss that leverages bounding box regression or segmentation masks alongside count estimation could further refine detection and localization, contributing to more precise counting results. Such a loss might also handle the inherent challenges of densely packed objects, a common problem in low-shot counting scenarios. The direct optimization of detection and counting, rather than relying on a surrogate task, is key to advancing accuracy and robustness in this domain. The focus should be on a loss that’s less prone to overfitting, allowing for better generalization across various object appearances.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for this low-shot object counting model, GeCo, could significantly improve its capabilities. Addressing the memory limitations that restrict processing of arbitrarily large images is crucial, potentially through techniques like local counting or hierarchical processing. Improving the inference speed is another key area, perhaps by exploring more efficient backbones or optimized inference strategies. Extending GeCo to handle multi-class scenes more effectively is another vital improvement; the current method struggles with complex scenes. Lastly, investigating the model’s robustness to various noise types and challenging conditions (e.g., extreme lighting, occlusion) will provide valuable insights and guide the development of more resilient and adaptable low-shot object counters.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure shows the architecture of the GeCo model, a single-stage low-shot object counter. It starts with an image input that is encoded by a SAM (Segment Anything Model) backbone into feature maps. These features are then used for prototype extraction (using appearance and shape information from exemplars). The prototypes are generalized by a dense object query encoder (DQE) which outputs dense object queries. These queries are decoded by a dense query decoder (DQD) which outputs object detections and a counting result. The final detections are extracted and refined through a post-processing step, providing both bounding boxes and segmentation masks for the detected objects.

read the caption

Figure 2: The architecture of the proposed single-stage low-shot counter GeCo.

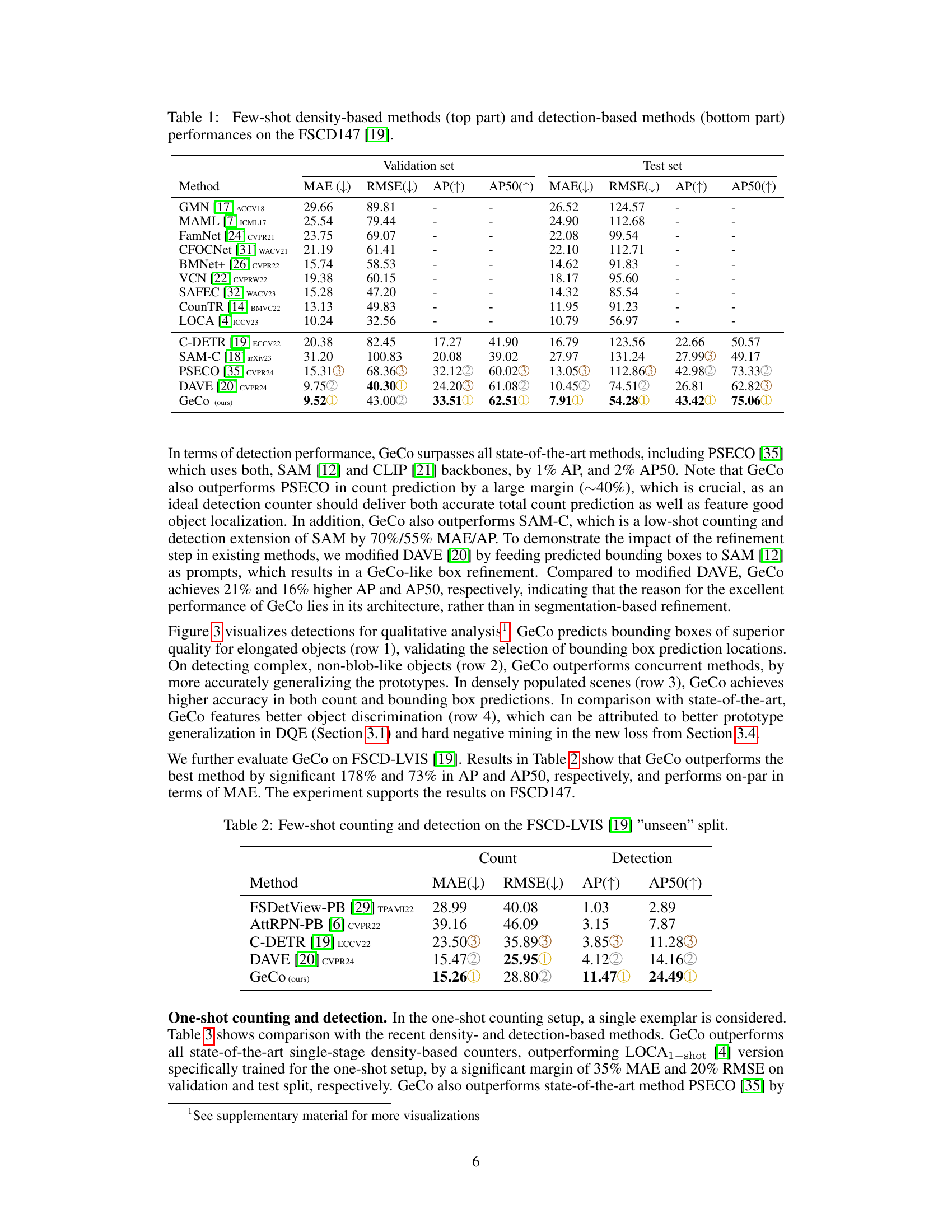

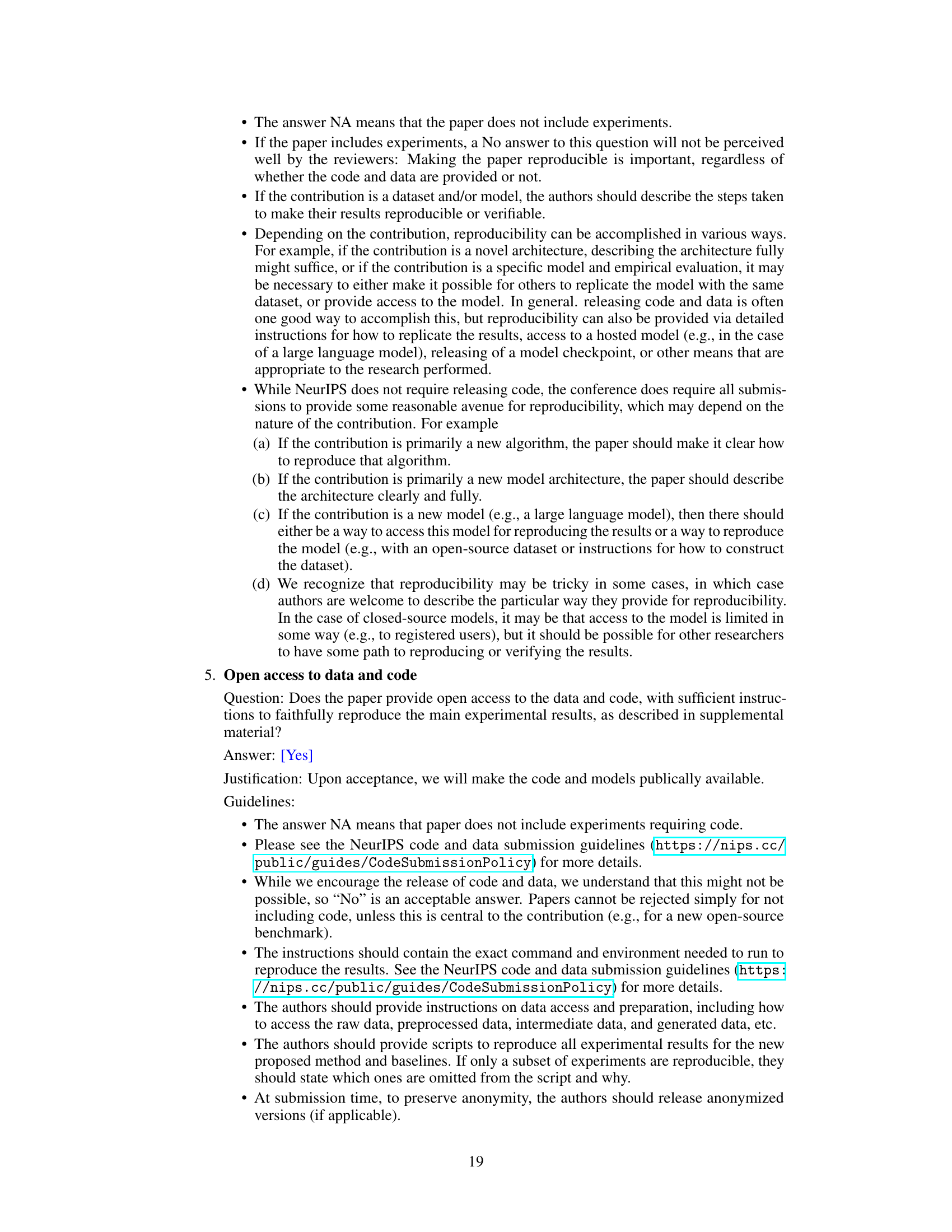

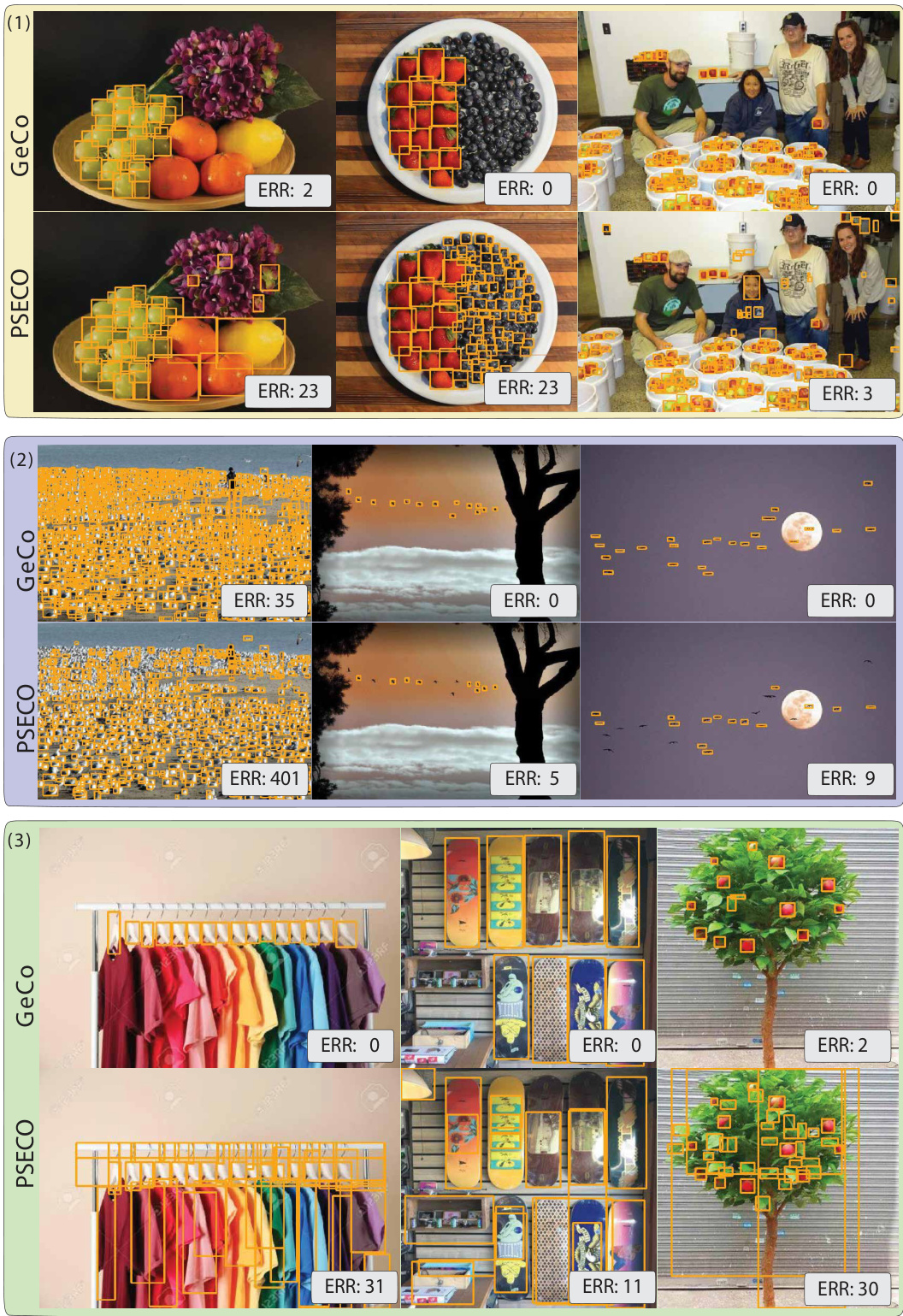

🔼 This figure compares GeCo’s performance against other state-of-the-art few-shot detection-based methods (DAVE, PSECO, CDETR) on various image examples. It highlights GeCo’s superior ability to produce accurate object detections with fewer false positives, resulting in more accurate overall counts. The blue boxes represent the exemplar objects used in the few-shot learning process.

read the caption

Figure 3: Compared with state-of-the-art few-shot detection-based counters DAVE [20], PSECO [35], and C-DETR [19], GeCo delivers more accurate detections with less false positives and better global counts. Exemplars are delineated with blue color, while segmentations are not shown for clarity.

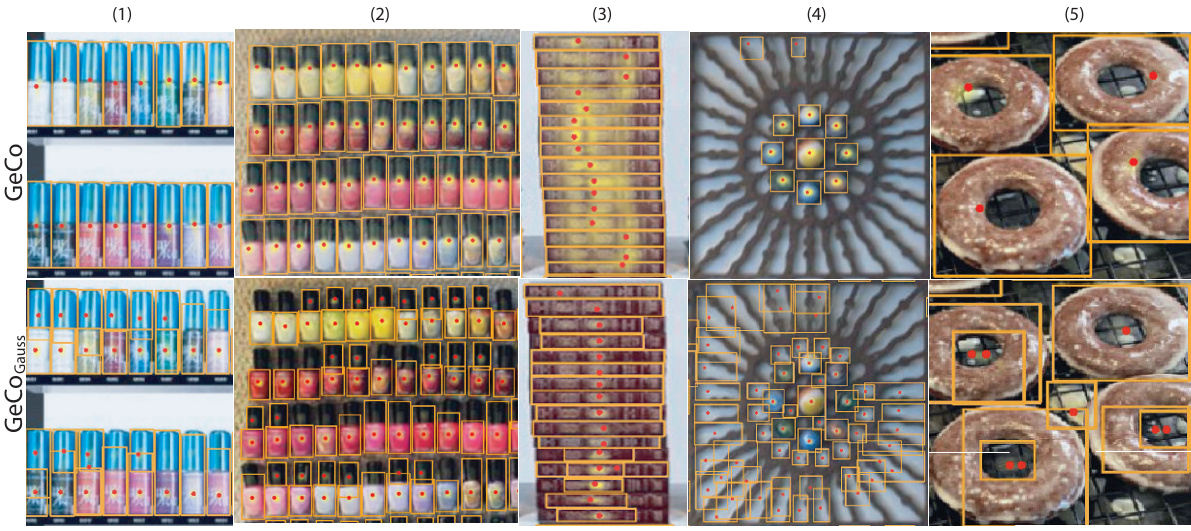

🔼 This figure compares the response maps and bounding box prediction locations of the proposed GeCo model with a baseline model using the standard loss. The top row shows GeCo’s results, highlighting the accurate localization of objects. The bottom row displays the baseline model’s results, demonstrating its tendency toward less precise object localization.

read the caption

Figure 4: Response maps (in yellow), and locations for bounding box predictions (red dots) when using the proposed (first row) and the standard [20; 4; 35] (second row) training loss.

🔼 This figure compares GeCo’s performance against other state-of-the-art few-shot detection-based counting methods (DAVE, PSECO, CDETR) across various examples. It visually demonstrates GeCo’s superiority in terms of accurate object detection, reduction in false positives, and overall more precise global count estimation. The blue boxes in the image highlight the exemplar objects provided to the models during training.

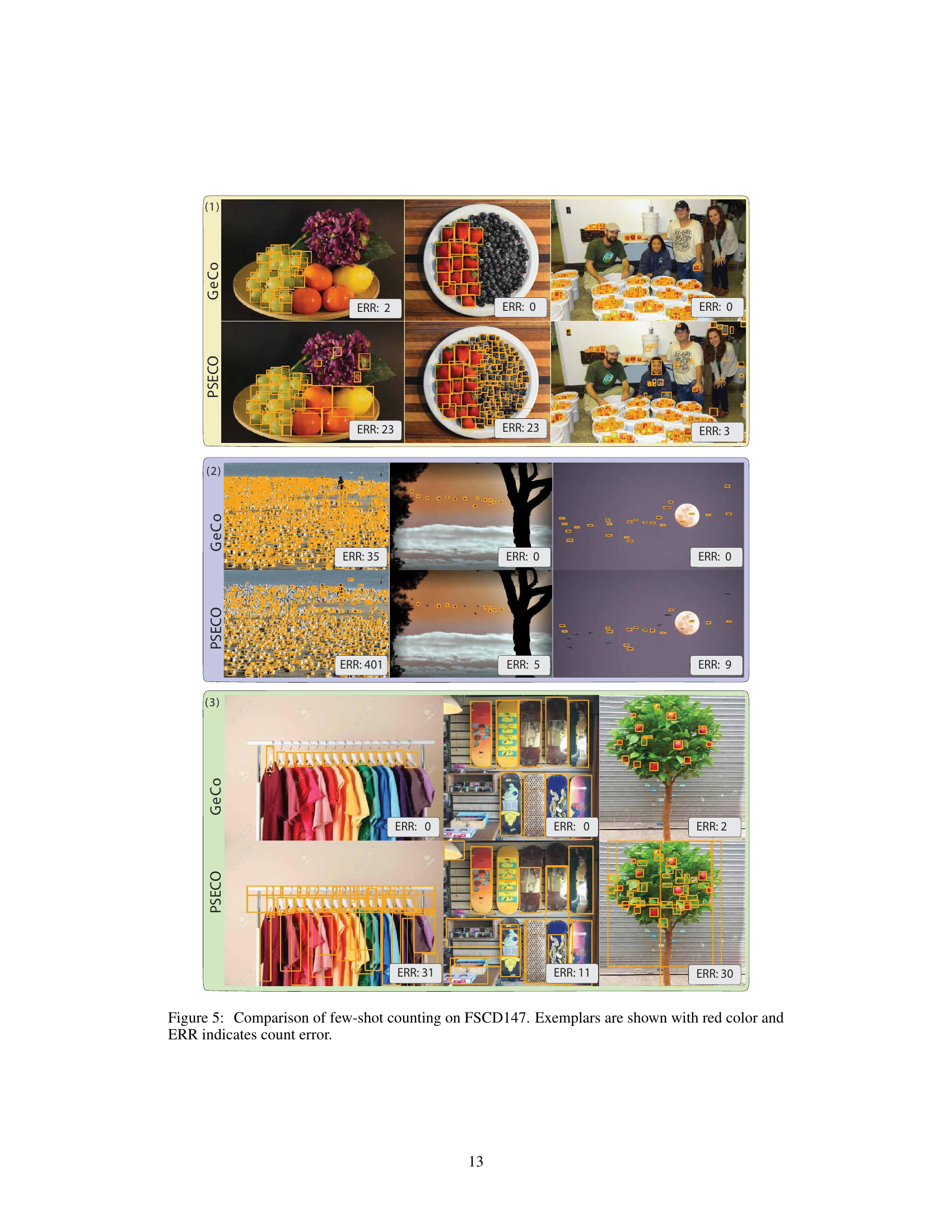

read the caption

Figure 3: Compared with state-of-the-art few-shot detection-based counters DAVE [20], PSECO [35], and C-DETR [19], GeCo delivers more accurate detections with less false positives and better global counts. Exemplars are delineated with blue color, while segmentations are not shown for clarity.

🔼 This figure shows examples of GeCo’s segmentation performance on various objects and scenes. It highlights GeCo’s ability to generate accurate segmentations even in challenging conditions such as images with noise, elongated objects, densely packed objects, and objects with significant intra-class variance (variation within the same object class). The red bounding boxes indicate the exemplar objects used for training.

read the caption

Figure 6: Segmentation quality of GeCo on diverse set of scenes and object types. Exemplars are denoted by red bounding boxes.

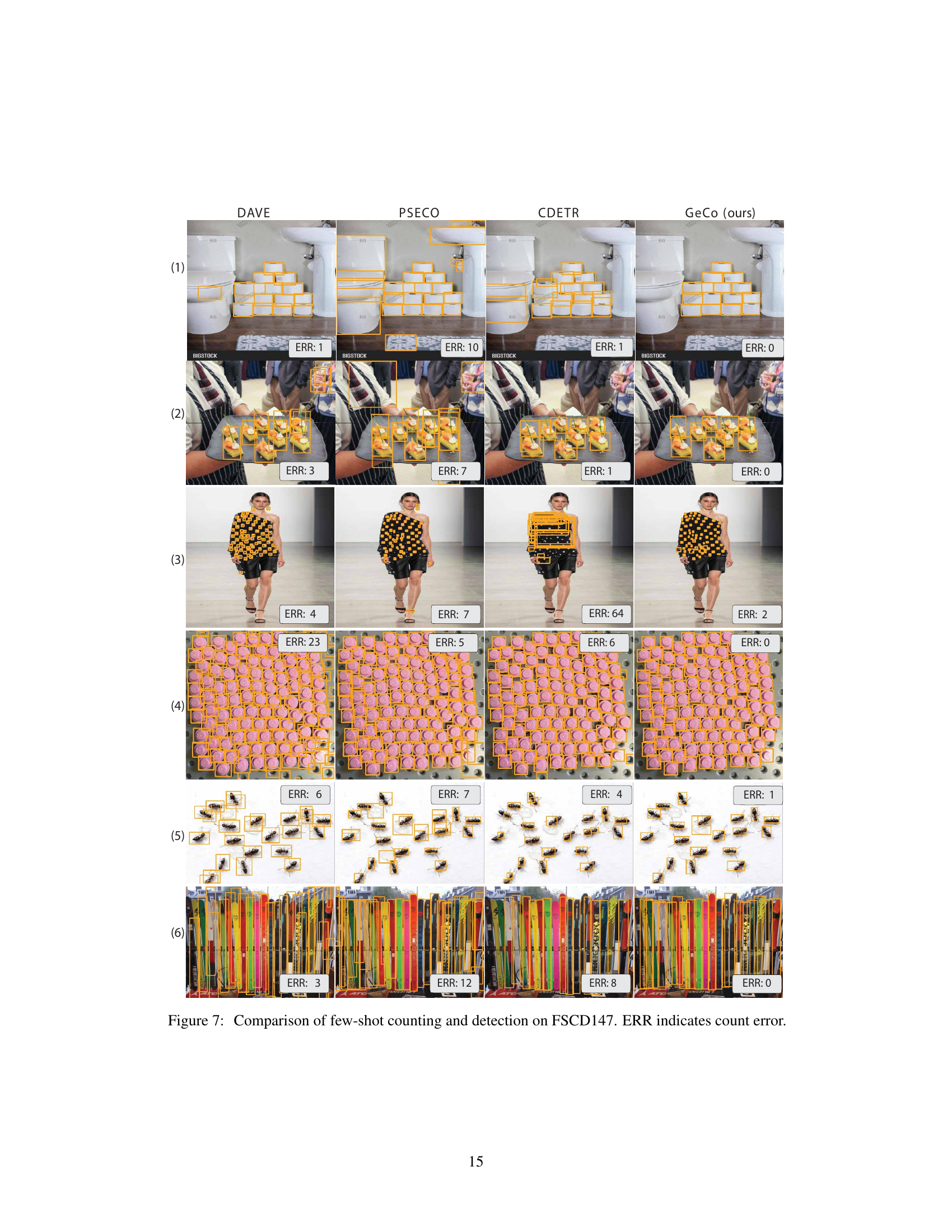

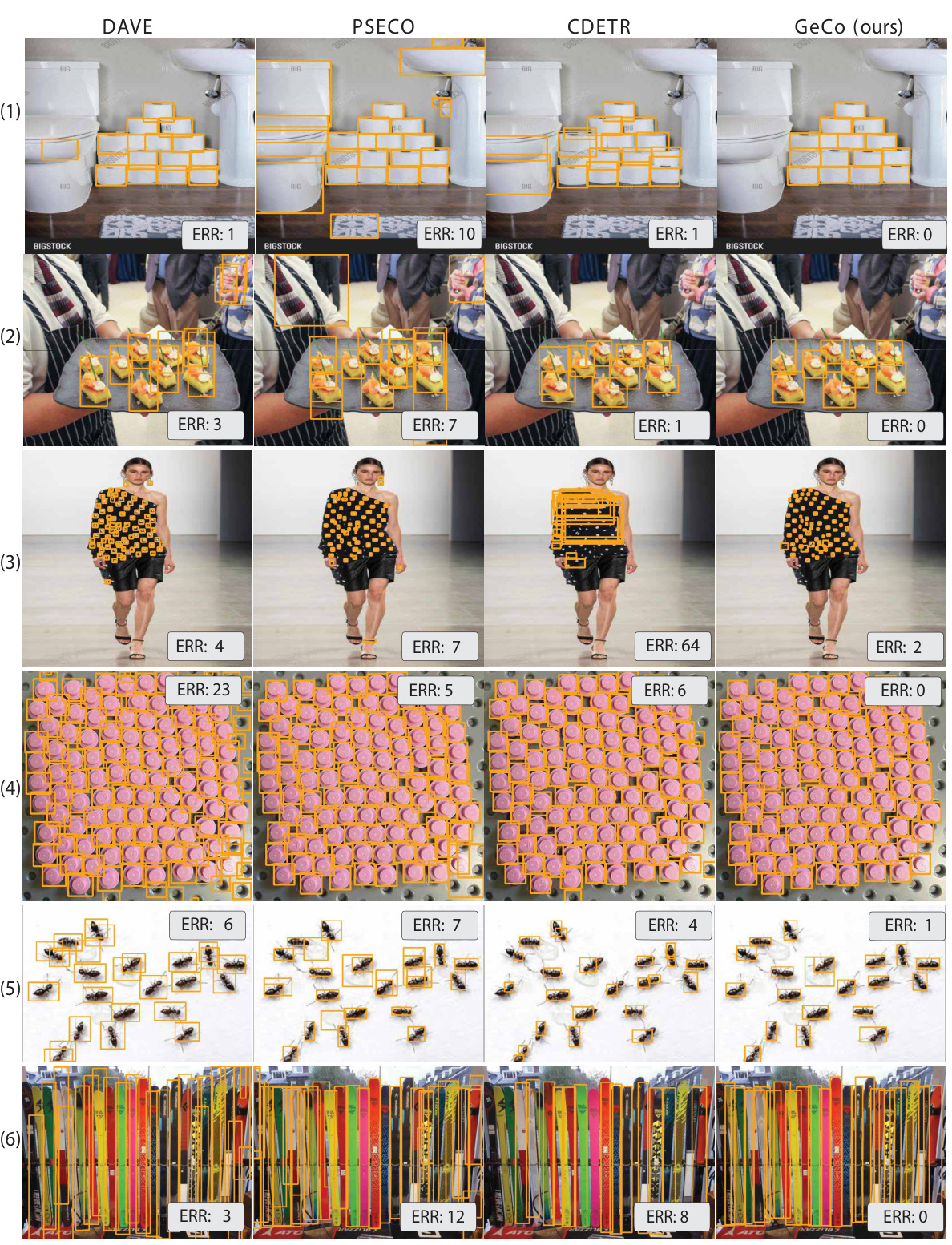

🔼 This figure compares the performance of four different few-shot object counting and detection methods (DAVE, PSECO, CDETR, and GeCo) on six example images from the FSCD147 dataset. Each row shows the same image processed by each of the four methods. The coloured bounding boxes indicate the objects detected by each method. The number following ‘ERR:’ represents the count error for each image and method; a lower number indicates better performance.

read the caption

Figure 7: Comparison of few-shot counting and detection on FSCD147. ERR indicates count error.

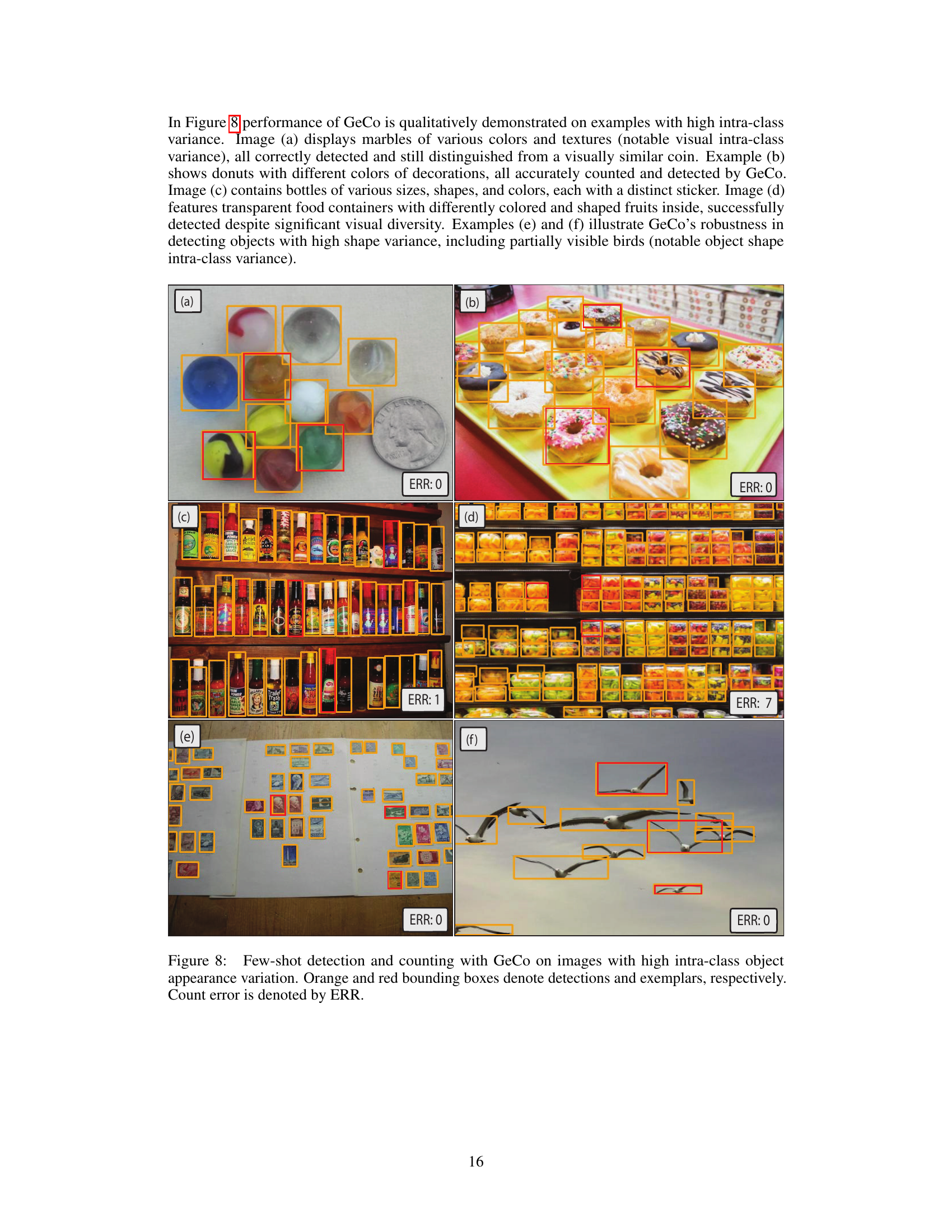

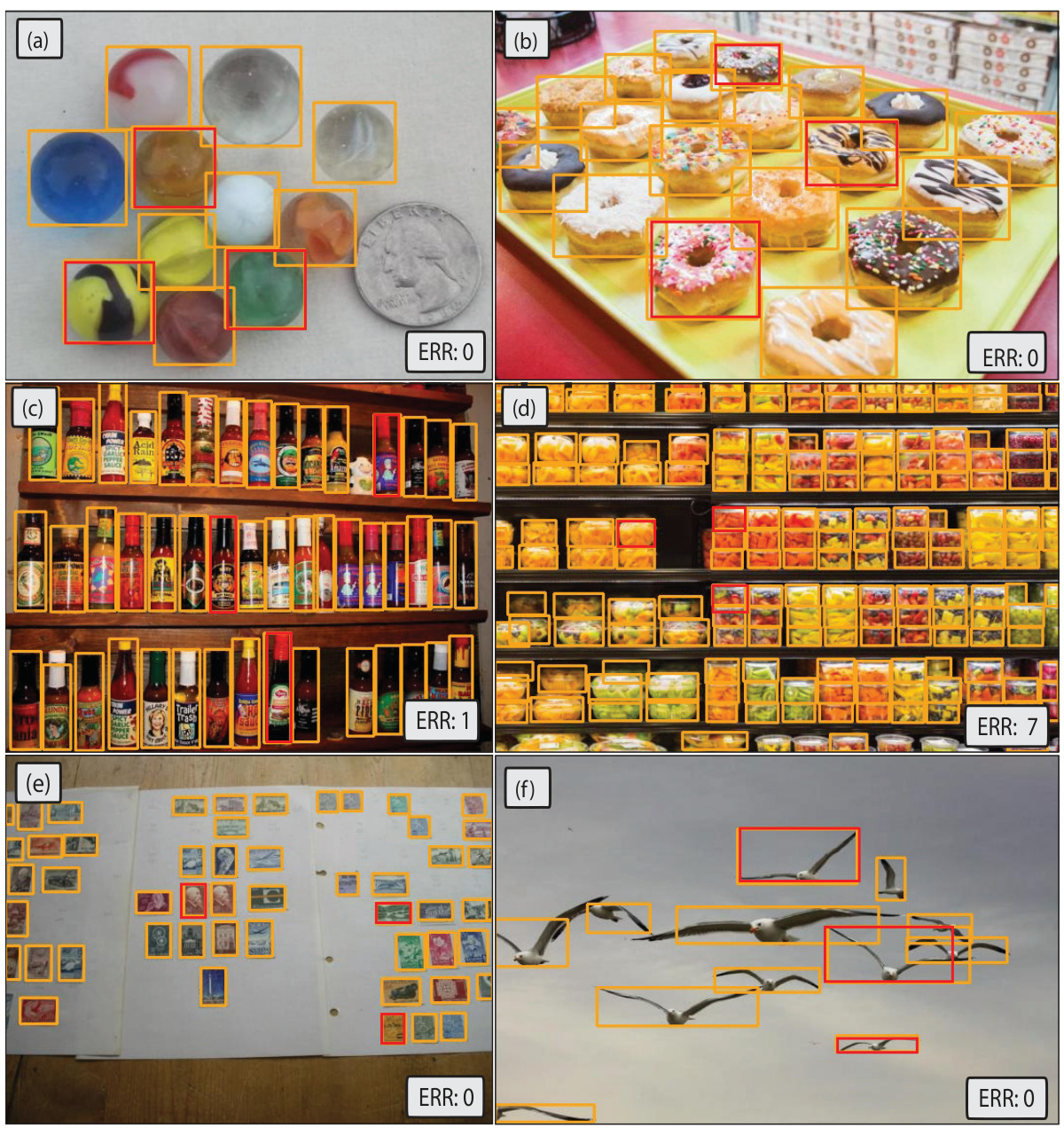

🔼 This figure demonstrates the qualitative performance of the GeCo model on images featuring high intra-class variance (i.e., significant visual similarities within the same class). It showcases GeCo’s ability to correctly detect and count objects with varying colors, textures, shapes, and sizes, even in challenging scenarios. The images include marbles of various colors and textures, donuts with different decorations, bottles with varying sizes and colors, transparent containers with different colored and shaped fruits, and partially visible birds. The results highlight GeCo’s robustness in handling intra-class variations and its accurate object detection and counting performance.

read the caption

Figure 8: Few-shot detection and counting with GeCo on images with high intra-class object appearance variation. Orange and red bounding boxes denote detections and exemplars, respectively. Count error is denoted by ERR.

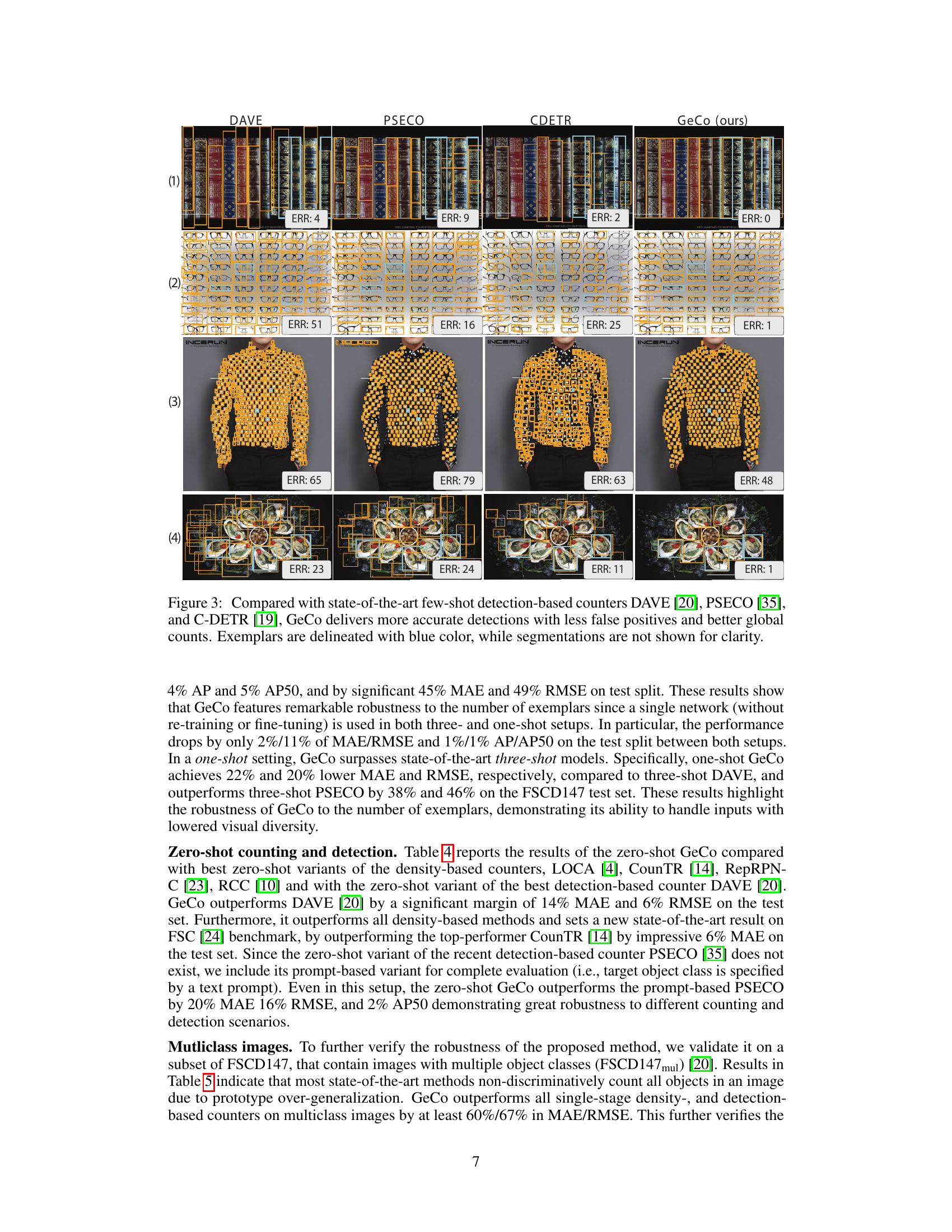

More on tables

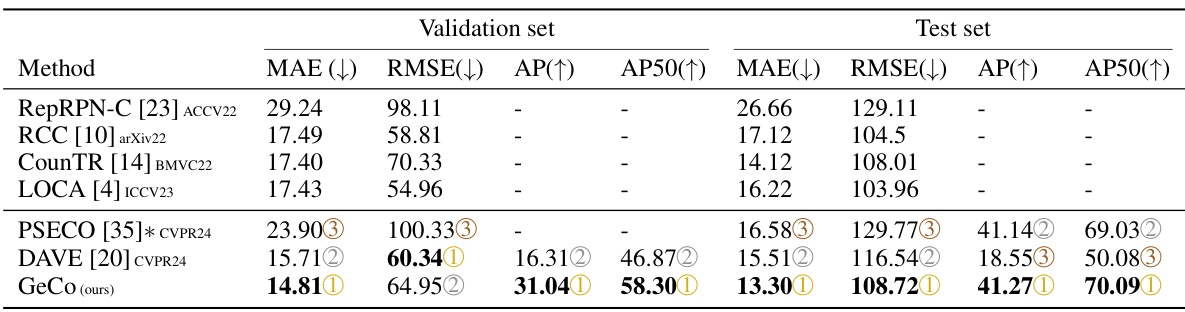

🔼 This table presents the results of few-shot object counting and detection experiments conducted on the FSCD-LVIS dataset’s unseen split. It compares the performance of GeCo against other state-of-the-art methods. The metrics used for evaluation include Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Precision (AP), and Average Precision at IoU=50 (AP50). Lower MAE and RMSE values indicate better counting accuracy, while higher AP and AP50 values reflect improved detection performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Few-shot counting and detection on the FSCD-LVIS [19] 'unseen' split.

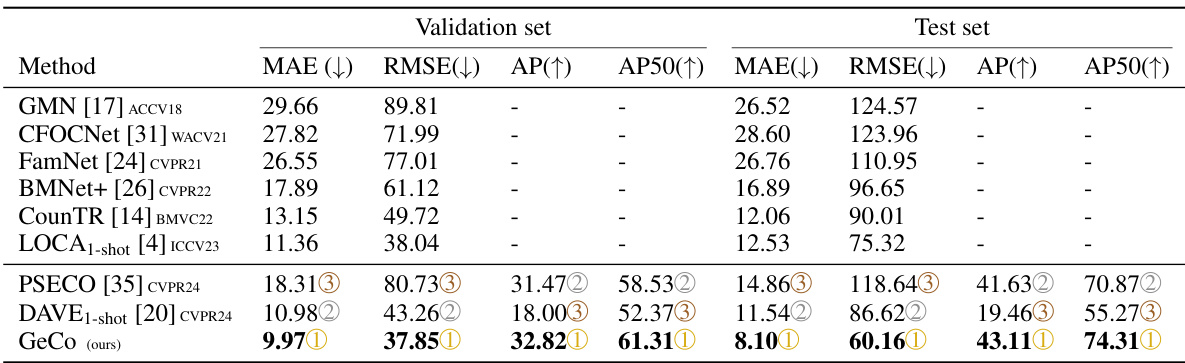

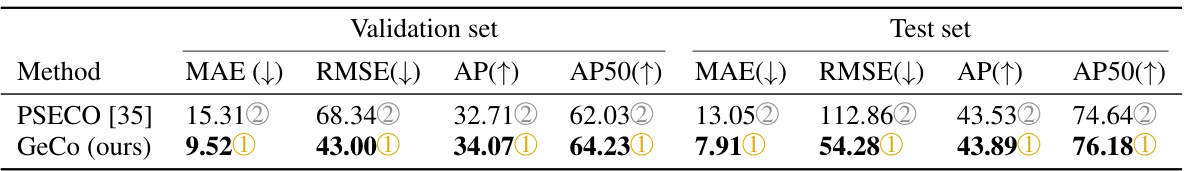

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various low-shot object counting methods on the FSCD147 dataset. It shows the performance of both density-based methods (which estimate the total count without object localization) and detection-based methods (which locate objects and use the number of detections to estimate the count). The metrics used for comparison are Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Precision (AP), and Average Precision at IoU=50 (AP50). The results are broken down for the validation and test sets of the FSCD147 dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: Few-shot density-based methods (top part) and detection-based methods (bottom part) performances on the FSCD147 [19].

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various low-shot object counting methods on the FSCD147 dataset. It’s divided into two sections: density-based methods (which estimate the count from a density map) and detection-based methods (which locate and count objects individually). For each method, the table shows the mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE), average precision (AP), and average precision at IoU=50 (AP50) on both validation and test sets of the dataset. The results illustrate the relative performance of different approaches in terms of both counting accuracy and object localization.

read the caption

Table 1: Few-shot density-based methods (top part) and detection-based methods (bottom part) performances on the FSCD147 [19].

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different low-shot object counting methods on the FSCD147 dataset. It’s divided into two sections: density-based methods and detection-based methods. For each method, it reports the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Precision (AP), and Average Precision at IoU=50 (AP50) on both a validation set and a test set. Lower MAE and RMSE values indicate better counting accuracy, while higher AP and AP50 values indicate better object detection accuracy. The table helps illustrate the relative performance of various techniques in low-shot object counting, highlighting GeCo’s superior performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Few-shot density-based methods (top part) and detection-based methods (bottom part) performances on the FSCD147 [19].

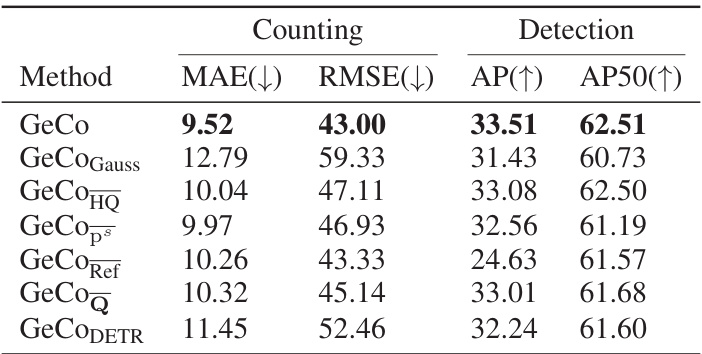

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the FSCD147 dataset’s validation split. The study investigates the impact of various components of the proposed GeCo model on its performance. Different versions of the GeCo model are compared, each with one component removed or altered to assess its contribution. The metrics used for comparison include Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Precision (AP), and Average Precision at 50% Intersection over Union (AP50). Lower MAE and RMSE values indicate better counting accuracy, while higher AP and AP50 values indicate better detection accuracy.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation study on the FSCD147 [19] validation split.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various few-shot object counting methods on the FSCD147 dataset. It compares both density-based methods (which estimate the total count without object localization) and detection-based methods (which predict both object locations and the total count). The metrics used for evaluation include Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Precision (AP), and Average Precision at IoU=50 (AP50). Lower MAE and RMSE values indicate better counting accuracy, while higher AP and AP50 values indicate better object detection accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Few-shot density-based methods (top part) and detection-based methods (bottom part) performances on the FSCD147 [19].

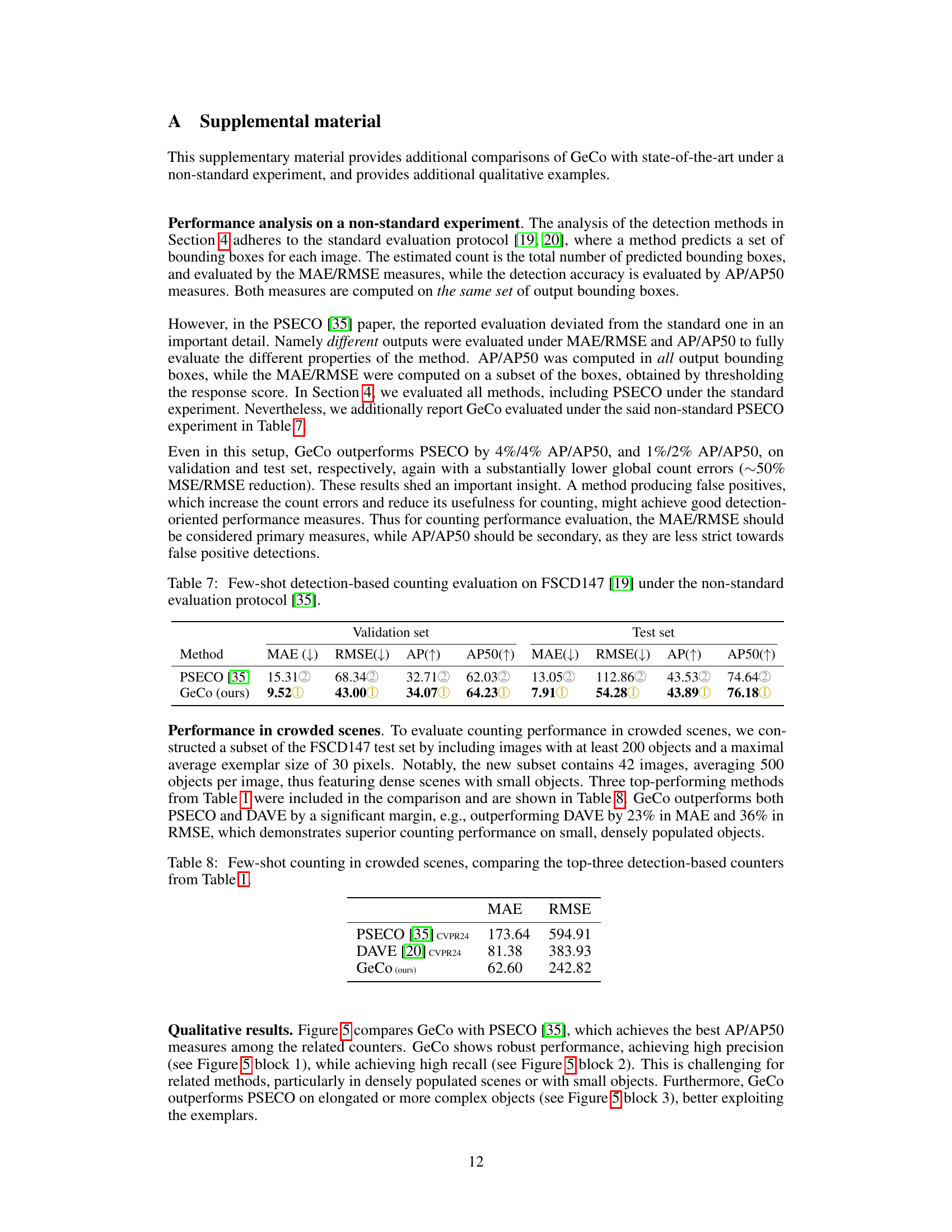

🔼 This table presents a comparison of three top-performing detection-based object counters (PSECO, DAVE, and GeCo) on a subset of the FSCD147 test set containing crowded scenes (at least 200 objects and a maximum average exemplar size of 30 pixels). The evaluation metrics used are Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), demonstrating GeCo’s superior performance in crowded scenes.

read the caption

Table 8: Few-shot counting in crowded scenes, comparing the top-three detection-based counters from Table 1.

Full paper#