TL;DR#

Protein optimization, crucial for drug discovery and material science, traditionally relies on computationally expensive methods and evolutionary information (EI) from protein language models (PLMs). However, these PLMs suffer from limitations: EI often includes irrelevant information for specific properties and models tend to overfit experimental conditions. This leads to reduced generalizability.

DePLM tackles these issues by refining EI in PLMs through a diffusion process in the rank space of property values. This denoising process enhances generalization and makes learning dataset-agnostic. Extensive experiments show DePLM outperforms state-of-the-art methods, demonstrating significant improvements in mutation effect prediction accuracy and superior generalization across novel proteins.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for protein engineering researchers due to its significant improvement in mutation effect prediction and strong generalization capabilities. It provides a novel approach to refine evolutionary information in protein language models, directly impacting the efficiency and accuracy of protein optimization. The method is also dataset-agnostic, making it widely applicable to various protein types and properties. It presents a new avenue for research by focusing on denoising evolutionary information through rank-based diffusion processes. This opens up new research avenues, and improves upon previous limitations by eliminating irrelevant information.

Visual Insights#

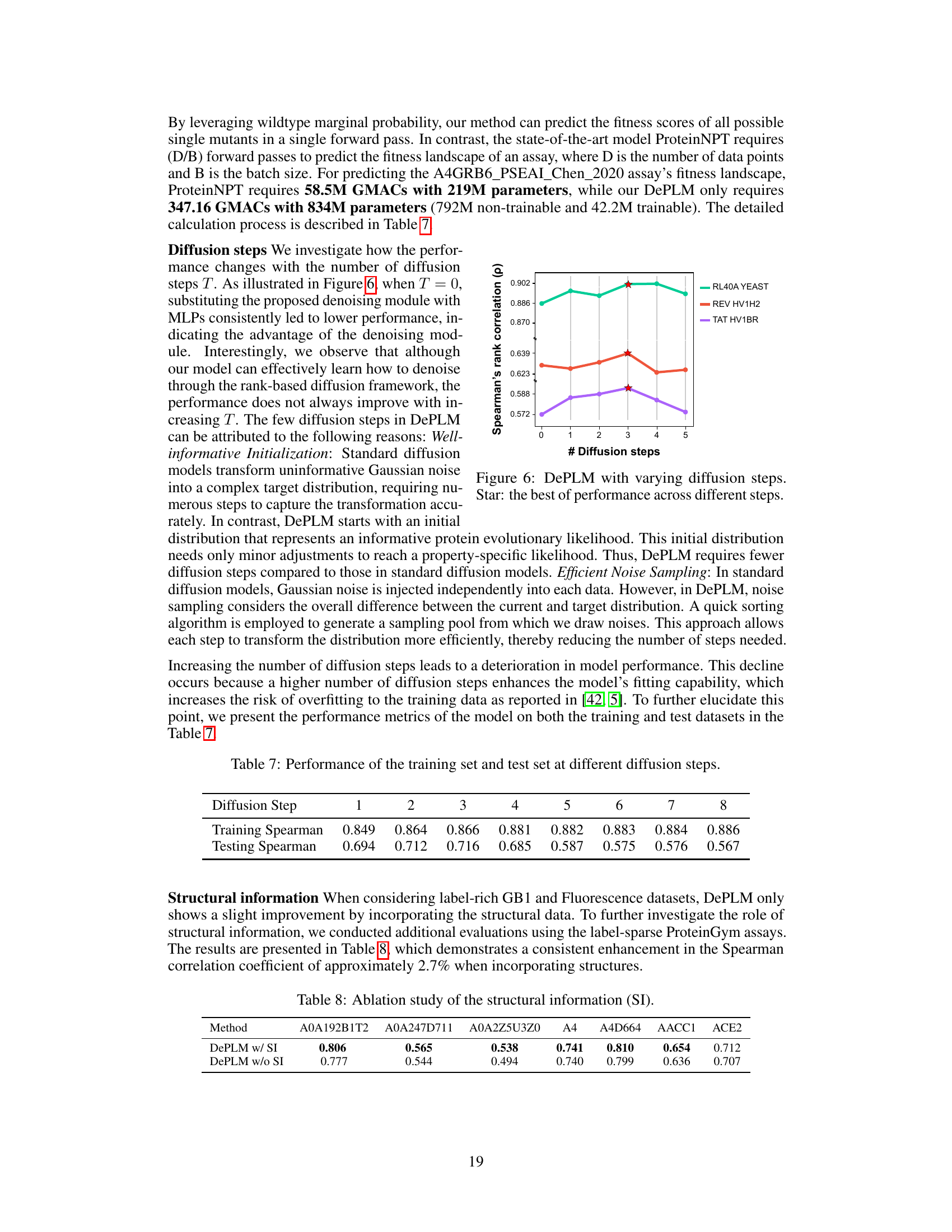

🔼 This figure compares three different methods for predicting protein fitness landscapes: self-supervised methods using only PLMs, supervised methods that fine-tune PLMs with additional data, and the proposed DePLM method. Self-supervised methods use PLMs to predict the likelihood of mutations, while supervised methods add a fitness header to the PLM for more accurate predictions. DePLM enhances the evolutionary information by denoising the likelihoods in the rank space of property values to achieve better generalization. The figure highlights the key differences in approach and the use of correlation metrics in evaluating the models.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of fitness landscape prediction methods. WT: wildtype sequence. MTs: mutant sequences. A2B: Amino acid A in wildtype mutates to B. GT.: groundtruth. Corr.: Correlation.

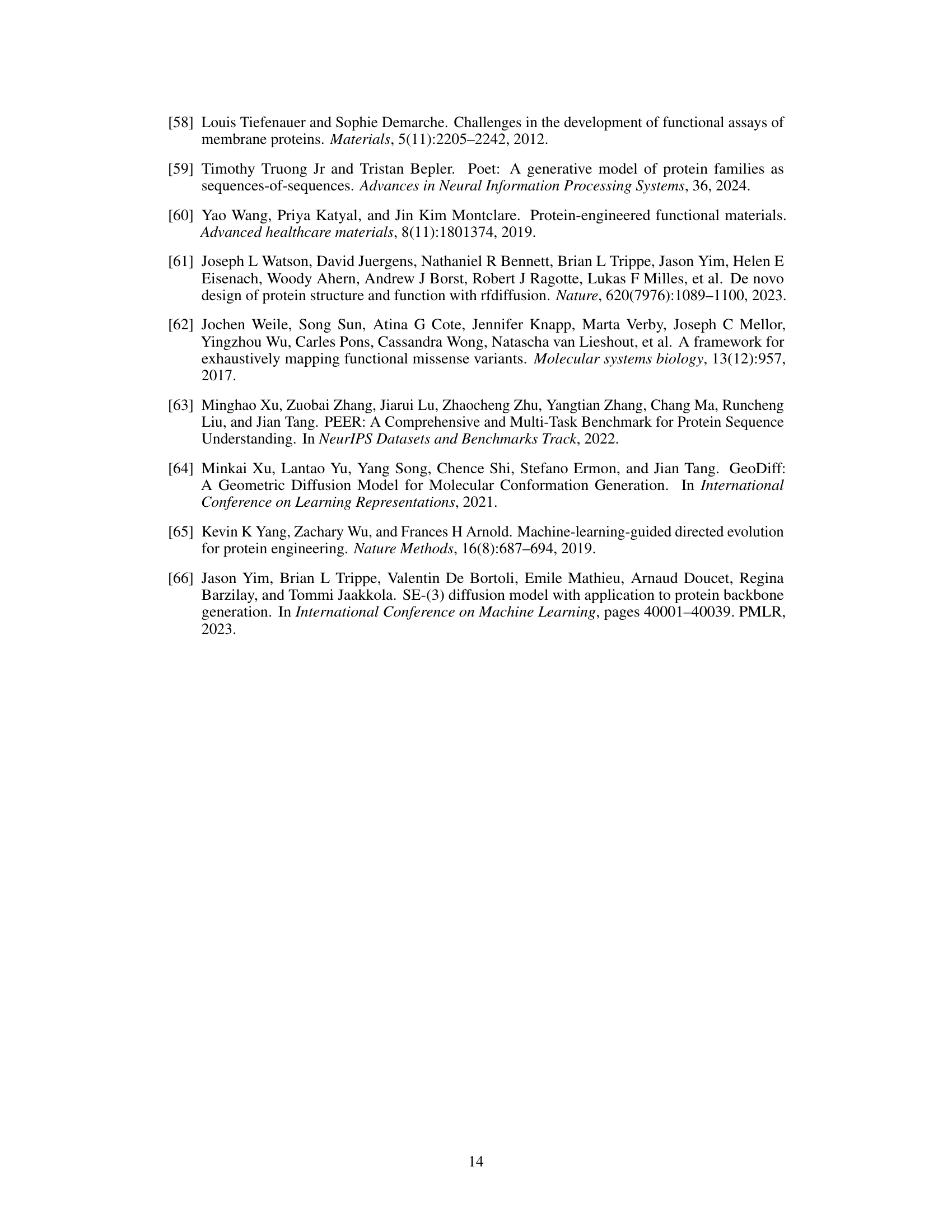

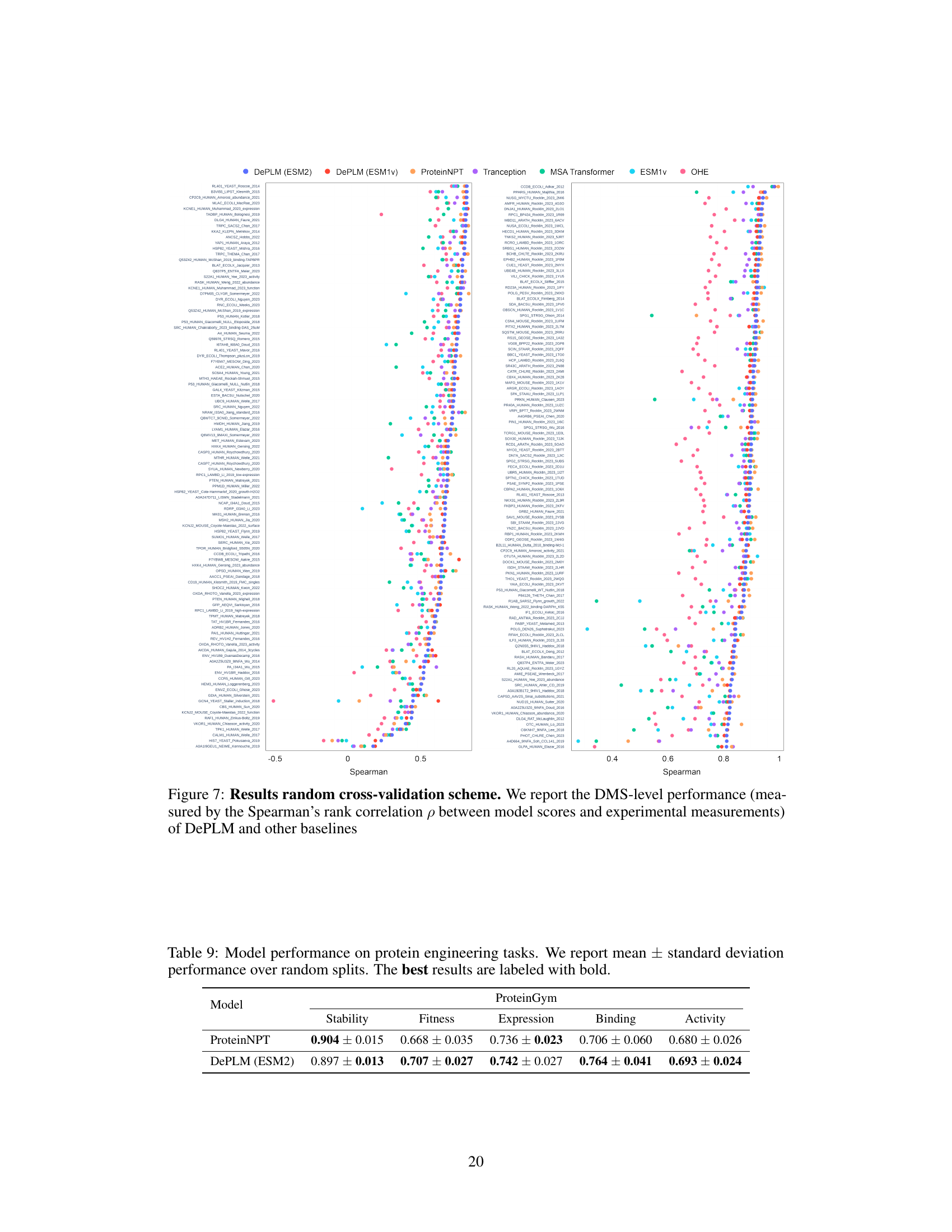

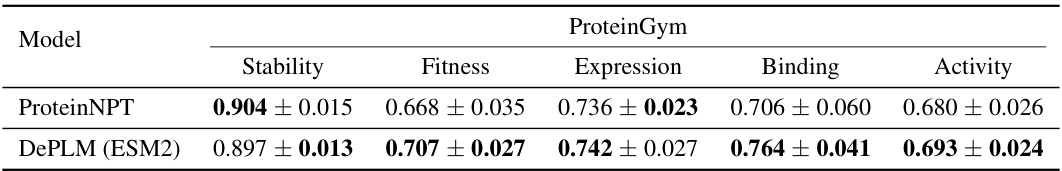

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of DePLM against various baselines across four protein engineering tasks (ProteinGym, B-Lactamase, GB1, and Fluorescence). The metrics used are Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for stability, fitness, expression, binding, and activity. The table highlights DePLM’s superior performance compared to existing methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Model performance on protein engineering tasks. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. ProteinGym results of OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT are borrowed from Notin et al. [46]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments.

In-depth insights#

DePLM: EI Denoising#

The heading ‘DePLM: EI Denoising’ suggests a method within the DePLM framework focused on refining evolutionary information (EI). The core idea is to separate relevant EI from noise; this noise being information not directly pertaining to the desired protein property. The approach likely involves a process, potentially a diffusion process as suggested in the full paper, that filters out this irrelevant EI. This denoising step is crucial because raw EI often encapsulates multiple properties simultaneously, hindering the optimization of any single property. By isolating the property-relevant information, DePLM likely enhances the model’s ability to predict fitness landscapes more accurately and generalizes better to novel proteins, therefore improving the precision and generalizability of protein optimization.

Rank-Based Diffusion#

Rank-based diffusion presents a novel approach to denoising evolutionary information in protein language models. Instead of operating directly on the likelihood values, it leverages the rank ordering of those values, thus making the process less sensitive to dataset-specific numerical variations and promoting better generalization. This approach is particularly powerful for protein optimization where relative fitness rankings often matter more than absolute fitness values. The method introduces a forward diffusion process that gradually introduces noise into the rank space, followed by a reverse process that learns to recover the original rank ordering. This rank-based strategy enhances robustness and improves the ability of the model to generalize to unseen proteins, addressing a key limitation of traditional methods. The use of rank correlation as the learning objective further underscores the focus on relative rankings and dataset-agnostic learning.

Protein Representation#

Effective protein representation is crucial for accurate prediction of protein properties and behavior. This involves capturing both primary sequence information (amino acid order) and higher-order structural features (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure). Strategies for representing proteins range from simple, sequence-based methods (e.g., one-hot encodings) to more complex approaches integrating structural data (e.g., embeddings from language models, structural graphs). Choice of representation significantly impacts model performance, particularly for tasks like mutation effect prediction or protein design where subtle structural changes are relevant. The use of evolutionary information adds another layer, allowing models to learn patterns from natural selection and protein family relationships. Furthermore, methods employing multimodal inputs, incorporating sequence and structure, tend to outperform unimodal methods. Finally, the generalizability of the learned representation, its ability to predict properties for unseen proteins, is a critical aspect for practical applications.

Generalization Ability#

The Generalization Ability section of a research paper would critically evaluate how well a model, trained on a specific dataset, performs when presented with unseen data. A strong emphasis would be placed on demonstrating the model’s ability to generalize beyond the training data, avoiding overfitting. This often involves testing on diverse datasets representing different aspects of the problem domain. The analysis would likely include metrics such as accuracy and precision, providing a quantitative measure of generalization performance. Furthermore, a qualitative discussion would analyze the reasons behind strong or weak generalization, exploring aspects such as model architecture, training techniques, and the characteristics of the datasets employed. A key goal is to show robustness and applicability to real-world scenarios, where encountering unseen instances is inevitable. Discussions of the limitations of generalization observed, and potential strategies to enhance this ability, would also feature prominently within this section.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore enhancing DePLM’s capabilities by incorporating more diverse data sources, including experimental data from various techniques beyond DMS, and integrating information from other modalities like protein structure and function annotations. Improving the efficiency of the rank-based denoising process, perhaps through exploring alternative diffusion models or optimization techniques, is another key area. Investigating the impact of different noise models and exploring approaches to explicitly model property-property interactions within the EI could also lead to significant advancements. Furthermore, extending DePLM to handle multi-mutation effects and more complex protein engineering tasks such as protein design and redesign would be highly valuable. Finally, thorough benchmarking across various datasets and properties would strengthen the model’s generalizability and reveal potential limitations, guiding future development and applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

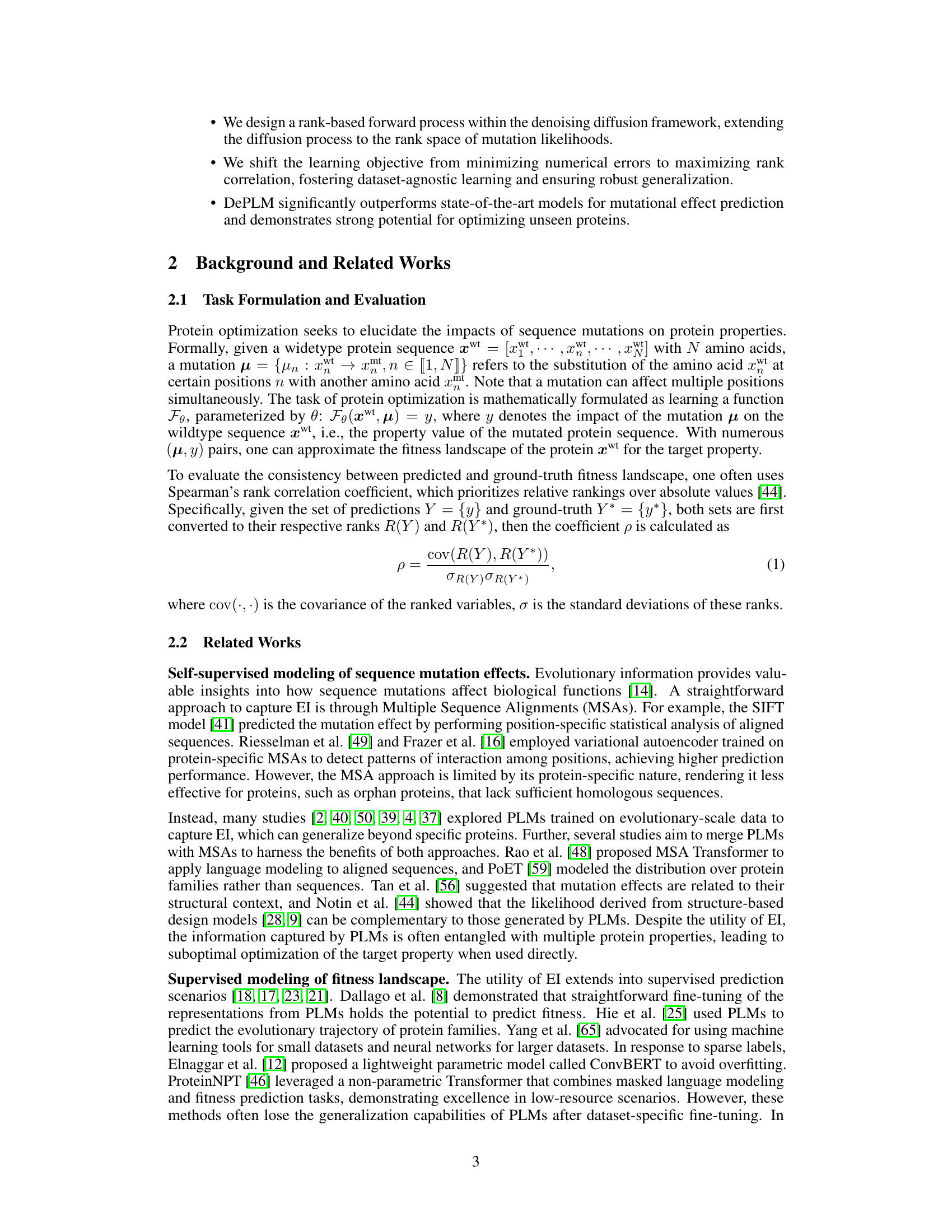

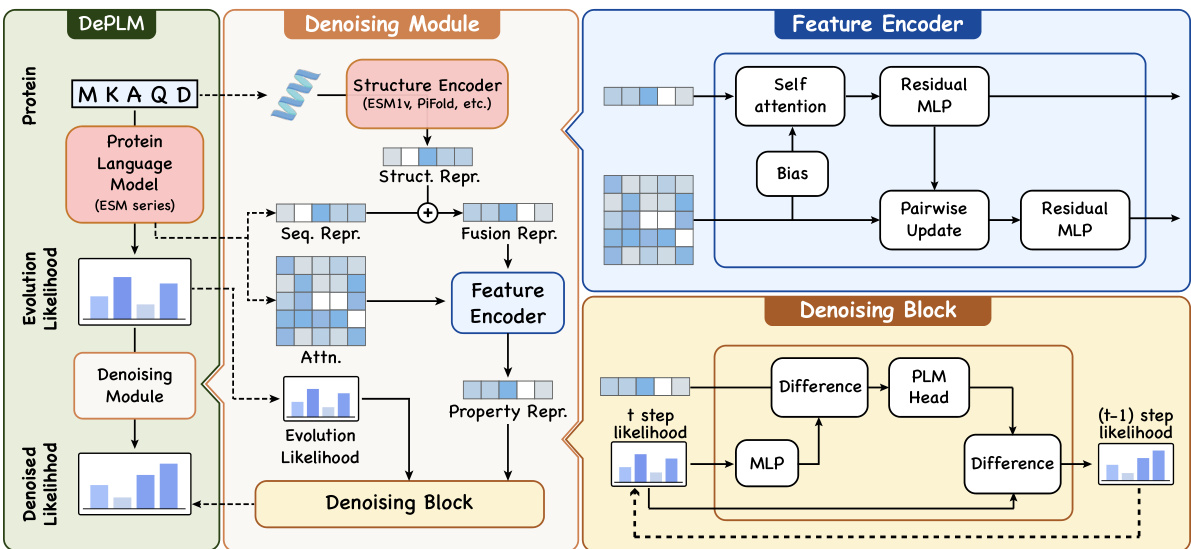

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the DePLM model. The model takes as input protein sequences and evolutionary likelihoods from pre-trained protein language models (PLMs). A feature encoder processes the protein sequences, integrating both primary and tertiary structure information. This information is then used in the denoising module to filter out irrelevant information from the evolutionary likelihoods, generating denoised likelihoods specifically tailored to the target protein properties. The denoising module uses denoising blocks to refine the noisy input to produce property-specific mutation likelihoods.

read the caption

Figure 2: The architecture overview of DePLM. Left: DePLM utilizes evolutionary likelihoods derived from PLMs as input, and generates denoised likelihoods tailored to specific properties for predicting the effects of mutations. Middle & Right: Denoising module utilizes a feature encoder to derive representations of proteins, taking into account both primary and tertiary structures. These representations are then employed to filter out noise from the likelihoods via denoising blocks.

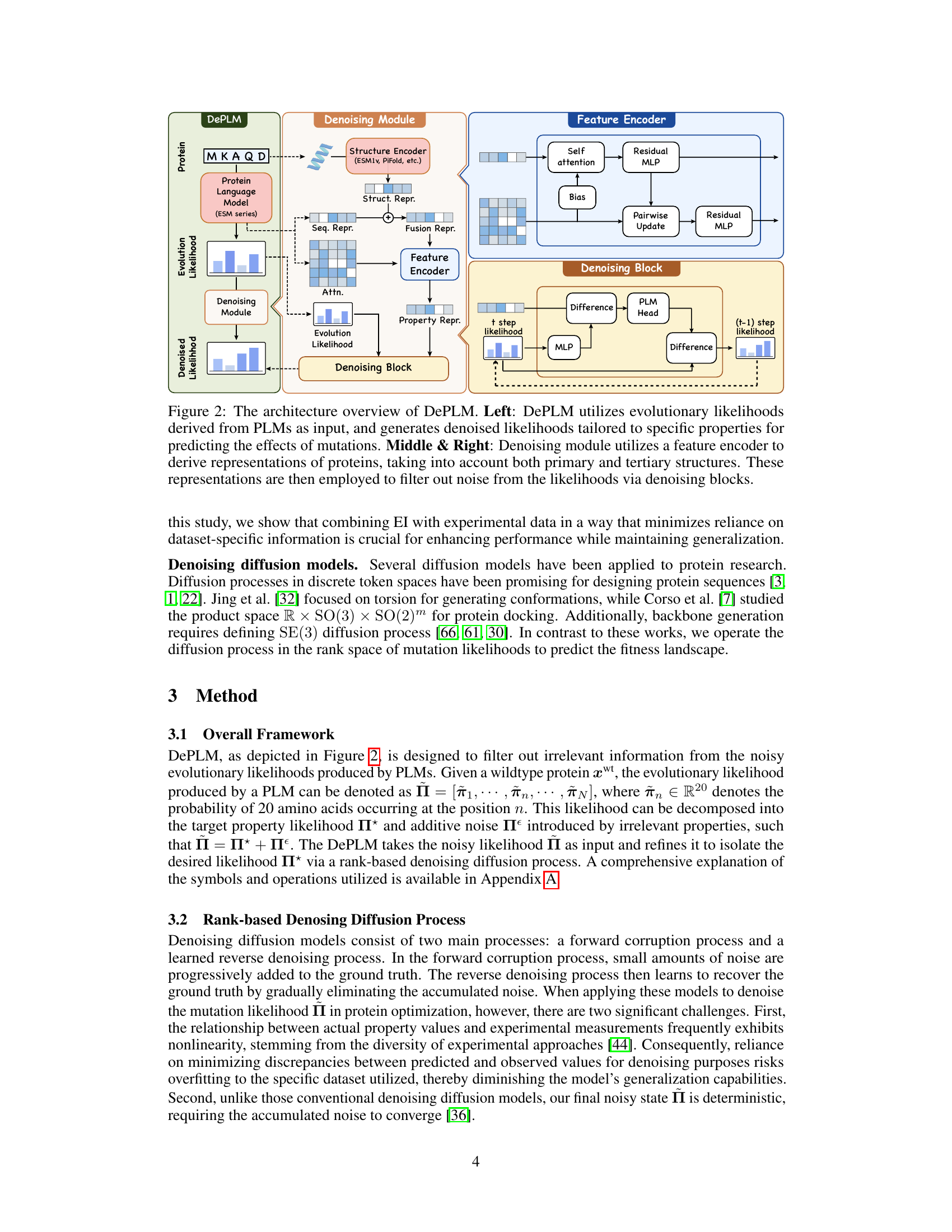

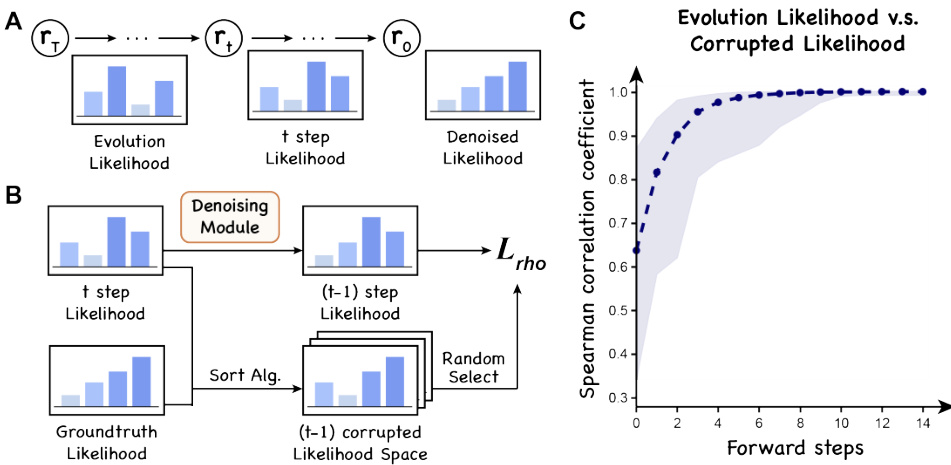

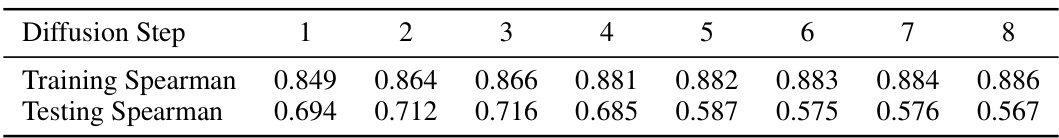

🔼 This figure illustrates the training process of the DePLM model. The left panel shows a schematic of the two main steps: a forward corruption process and a learned denoising backward process. The forward process uses sorting algorithms to create trajectories in rank space, moving from property-specific likelihoods to evolutionary likelihoods. The model is then trained to reverse this process (denoising backward process). The right panel shows a graph illustrating how the Spearman correlation coefficient changes during this transformation from evolutionary to property-specific likelihoods.

read the caption

Figure 3: The training process of DePLM. Left: The training of DePLM involves two main steps: rank-based controlled forward corruption and learned denoising backward processes. In the corruption step, we use sorting algorithms to generate trajectories, shifting from the rank of property-specific likelihood to that of the evolutionary likelihood. DePLM is trained to model the backward process. Right: We illustrate the alteration of the Spearman coefficient during the transformation from evolutionary likelihood to property-specific likelihood via the sorting algorithm.

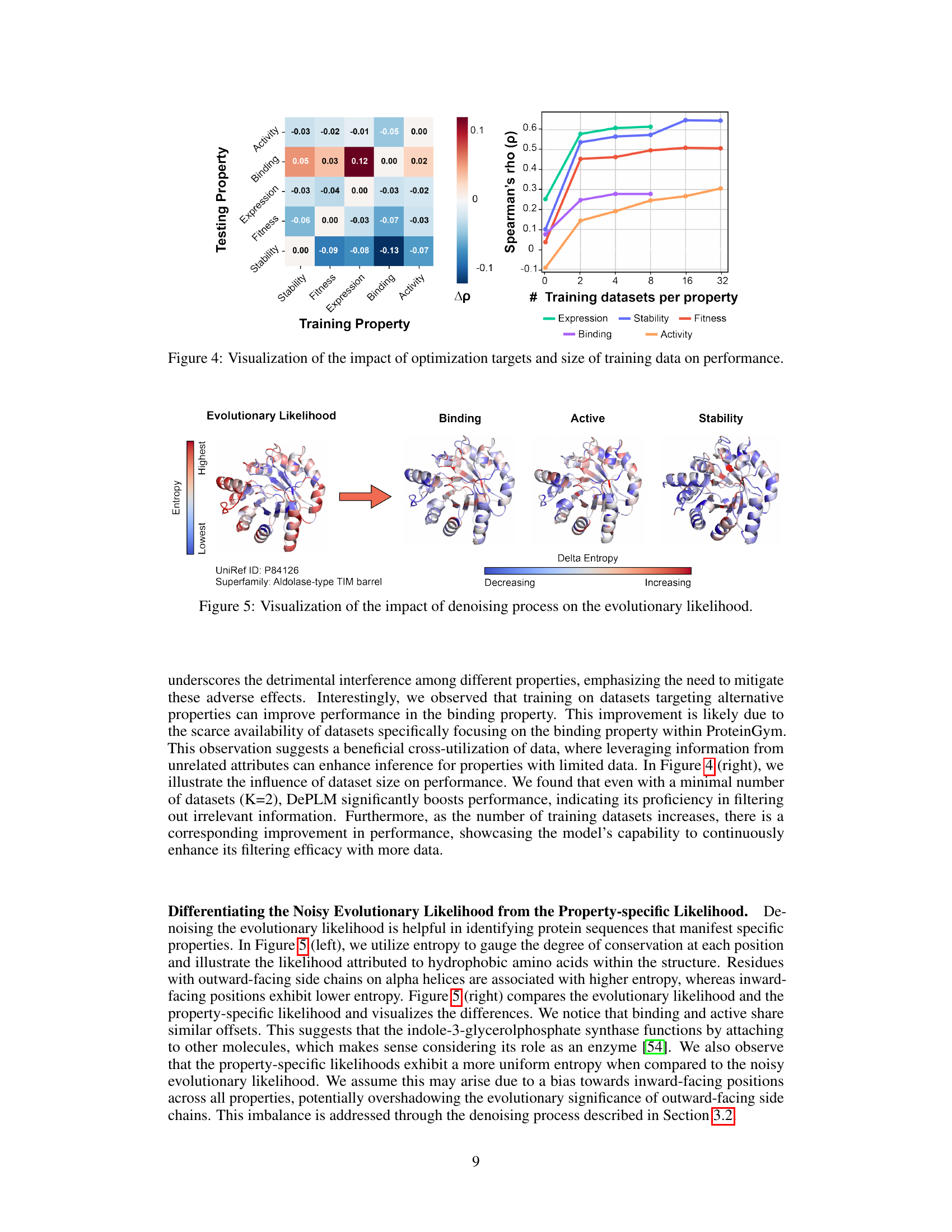

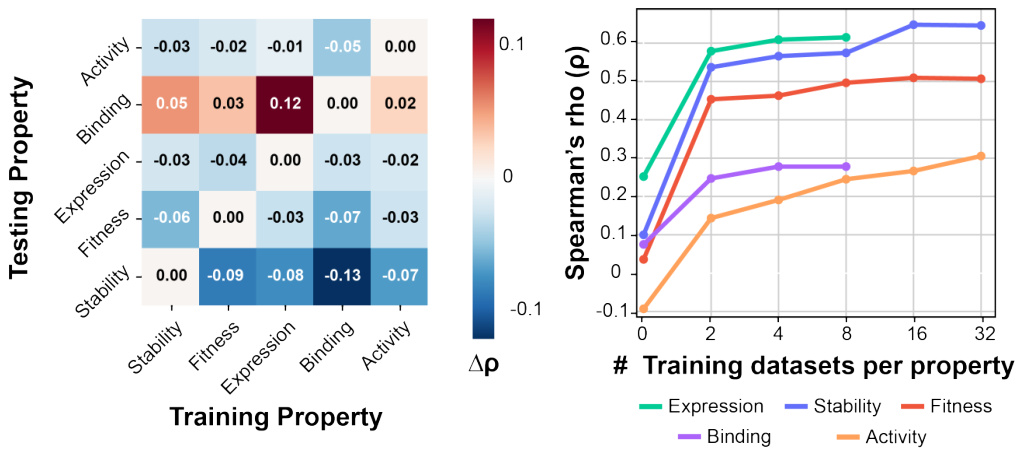

🔼 This figure visualizes the impact of different optimization targets and the size of training datasets on the model’s performance. The left panel is a heatmap showing the Spearman’s rank correlation (Δρ) between the testing and training properties. The right panel shows the Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ) for each property (stability, fitness, expression, binding, activity) as a function of the number of training datasets per property. The heatmap reveals the extent of cross-correlation or interference between different protein properties, while the line graph illustrates how the model’s generalizability increases with more training data for each target property.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of the impact of optimization targets and size of training data on performance.

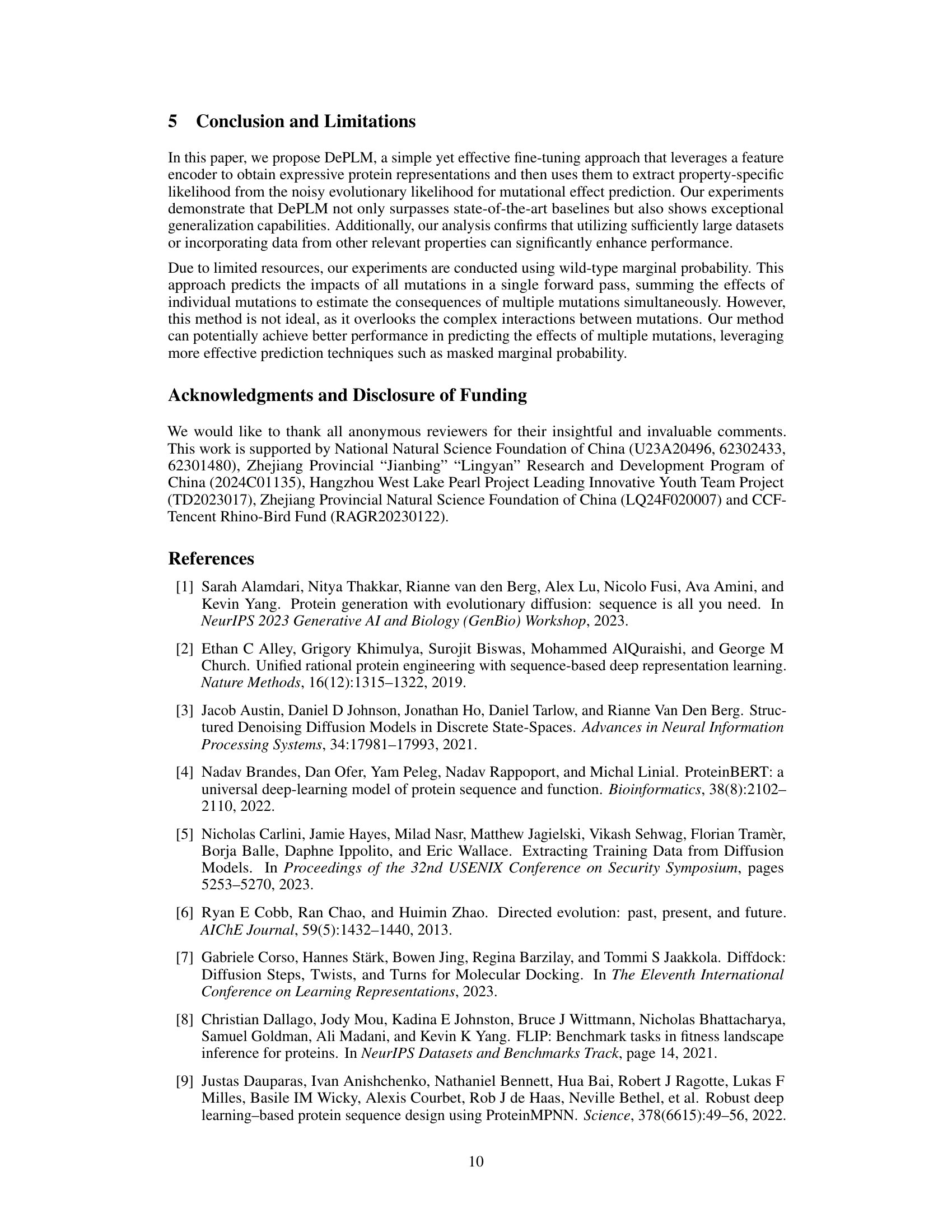

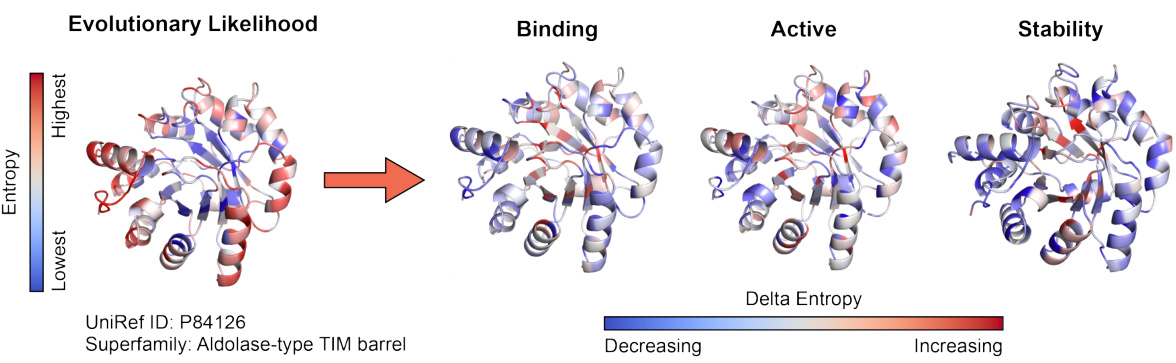

🔼 The figure visualizes how the denoising process in DePLM refines the noisy evolutionary likelihood to isolate property-specific information. It shows the evolutionary likelihood of a protein (UniRef ID: P84126, Aldolase-type TIM barrel) and compares it with property-specific likelihoods for binding, active, and stability. The color gradient represents entropy, ranging from lowest (blue) to highest (red). Differences between evolutionary likelihood and property-specific likelihoods are shown, highlighting how DePLM effectively filters out noise and enhances relevant signals.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization of the impact of denoising process on the evolutionary likelihood.

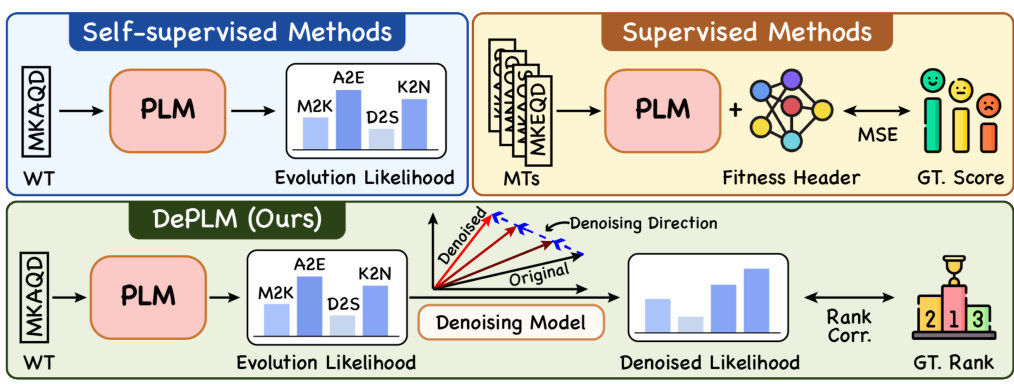

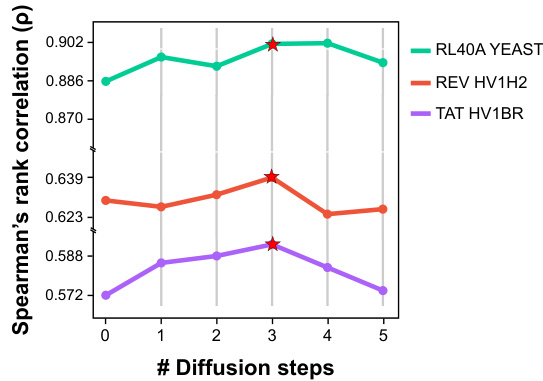

🔼 This figure shows the performance of DePLM model with varying numbers of diffusion steps (0 to 5). The performance is measured by Spearman’s rank correlation. The star indicates the optimal number of diffusion steps for each dataset. The results suggest that a small number of diffusion steps are sufficient for optimal performance of the DePLM model and that increasing the number of steps may lead to overfitting.

read the caption

Figure 6: DePLM with varying diffusion steps. Star: the best of performance across different steps.

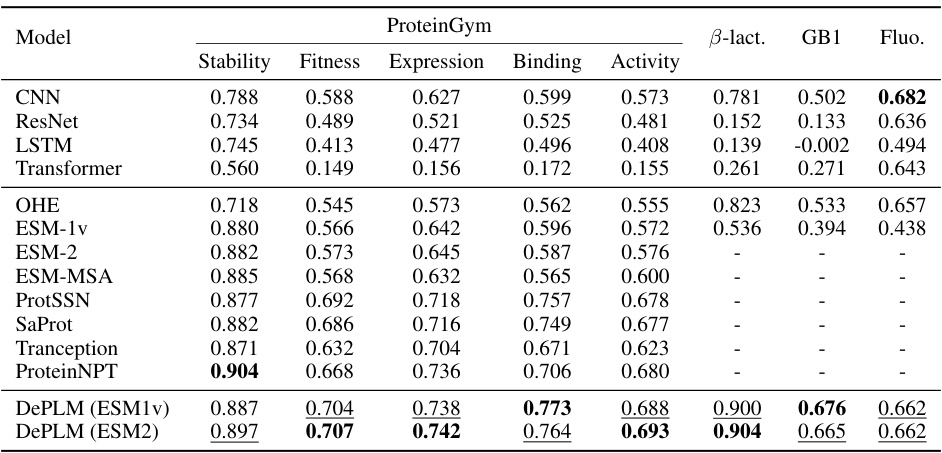

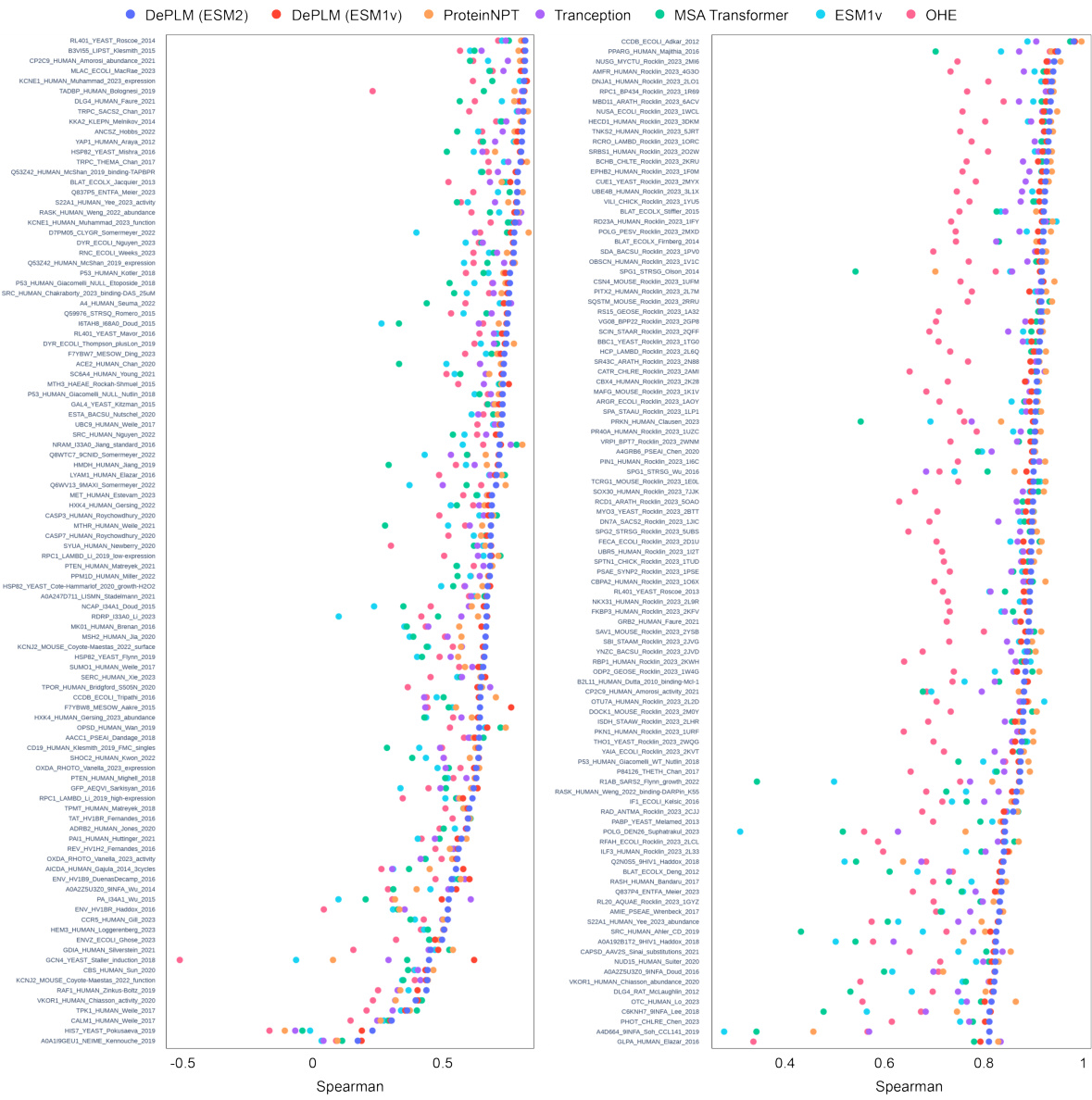

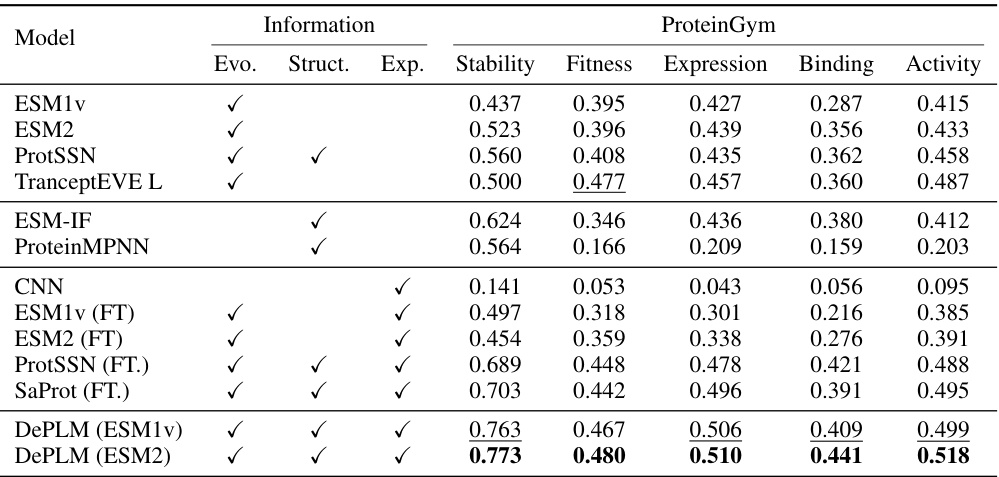

🔼 This figure shows the performance of DePLM and other baselines using the Spearman’s rank correlation. The x-axis represents different datasets, and the y-axis represents the Spearman’s rank correlation between the predicted and experimental measurements. Each point represents a dataset, and the color of the point represents the model. The figure helps in visualizing the performance of DePLM against other baselines across various datasets. The results are from a random cross-validation experiment.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results random cross-validation scheme. We report the DMS-level performance (measured by the Spearman's rank correlation ρ between model scores and experimental measurements) of DePLM and other baselines

🔼 This figure compares different methods for predicting protein fitness landscapes. It highlights the difference between self-supervised and supervised methods, and introduces the proposed DePLM approach. The diagram shows how various methods utilize protein language models (PLMs) and evolutionary information to predict the fitness of mutant protein sequences compared to the wildtype sequence. DePLM’s unique feature is its denoising process conducted in the rank space, enhancing model generalization.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of fitness landscape prediction methods. WT: wildtype sequence. MTs: mutant sequences. A2B: Amino acid A in wildtype mutates to B. GT.: groundtruth. Corr.: Correlation.

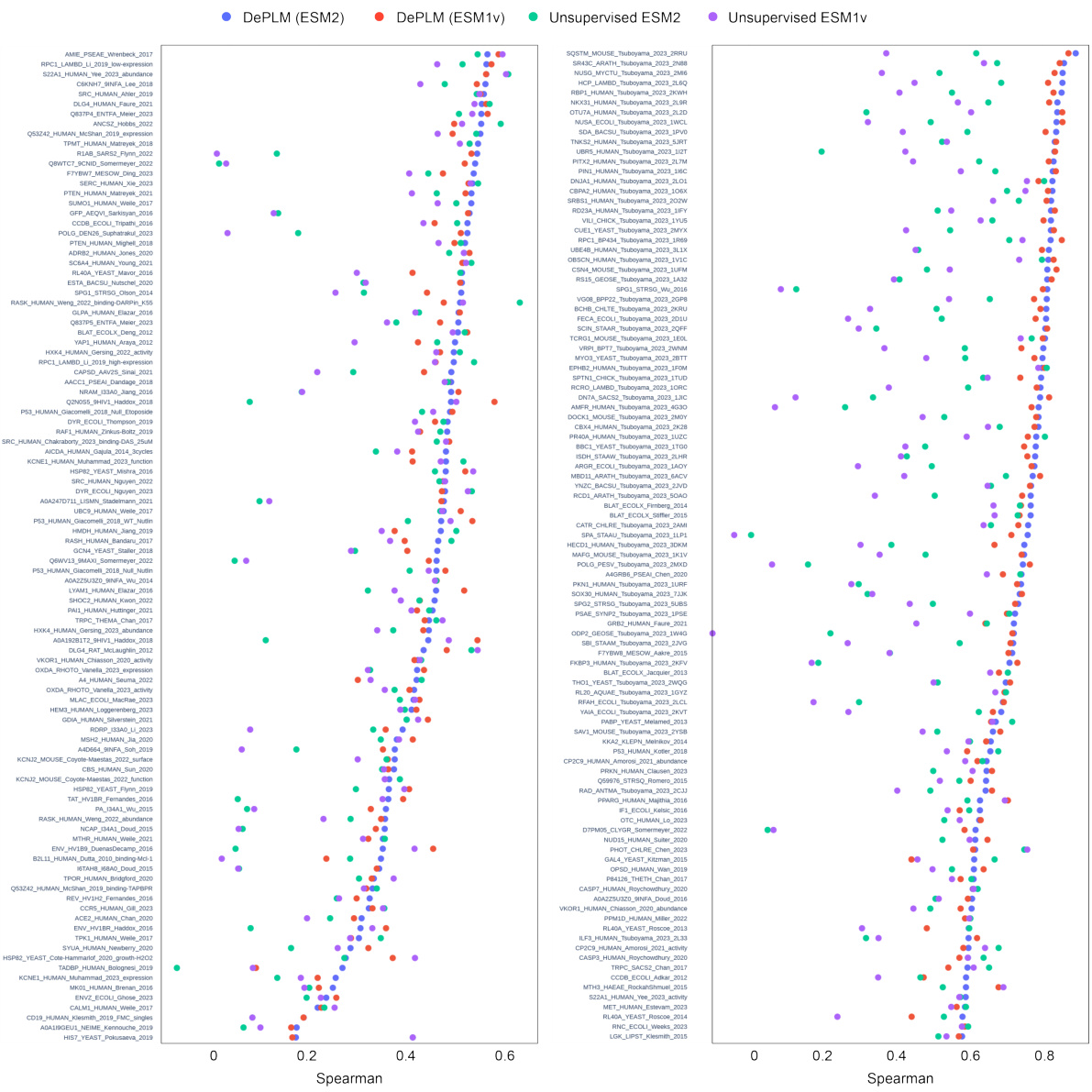

More on tables

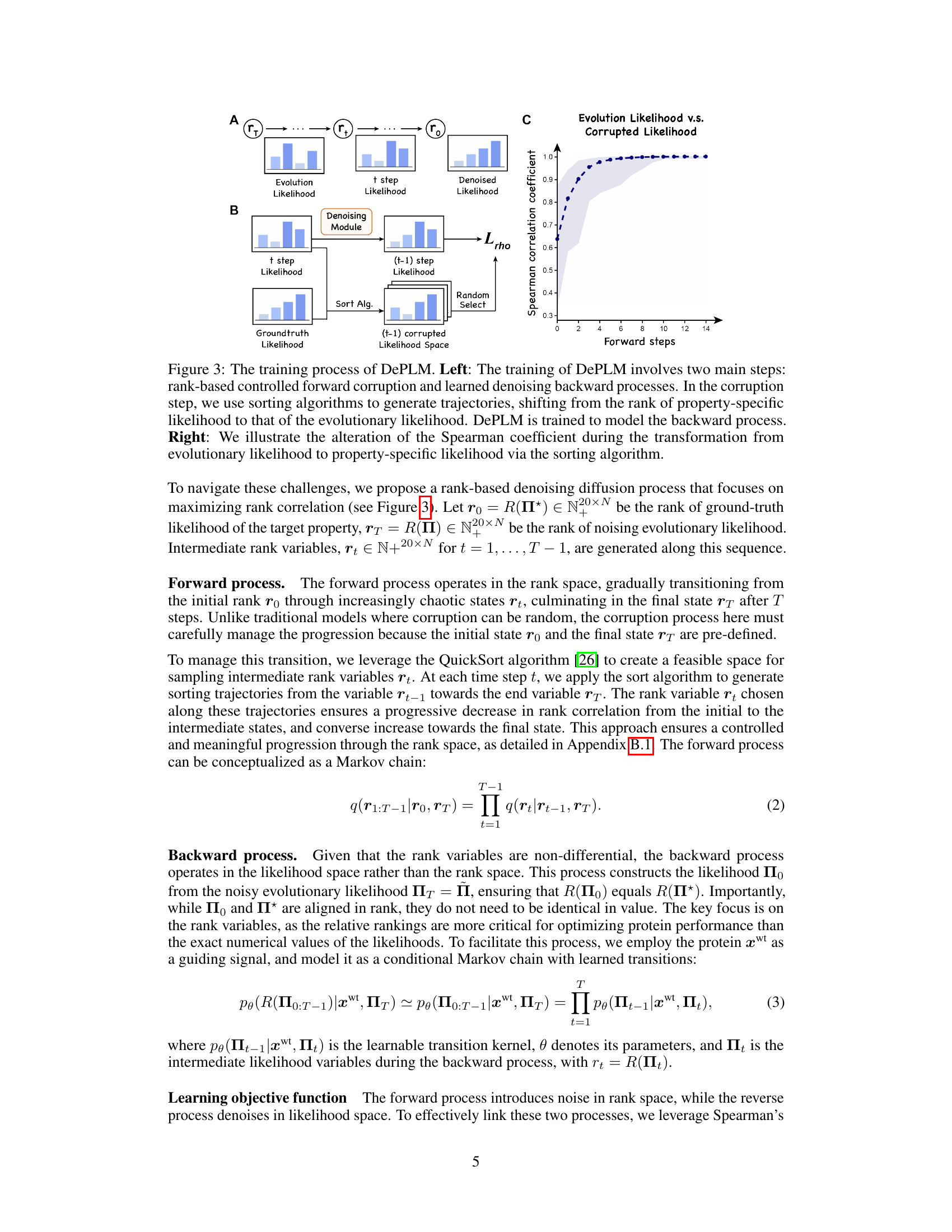

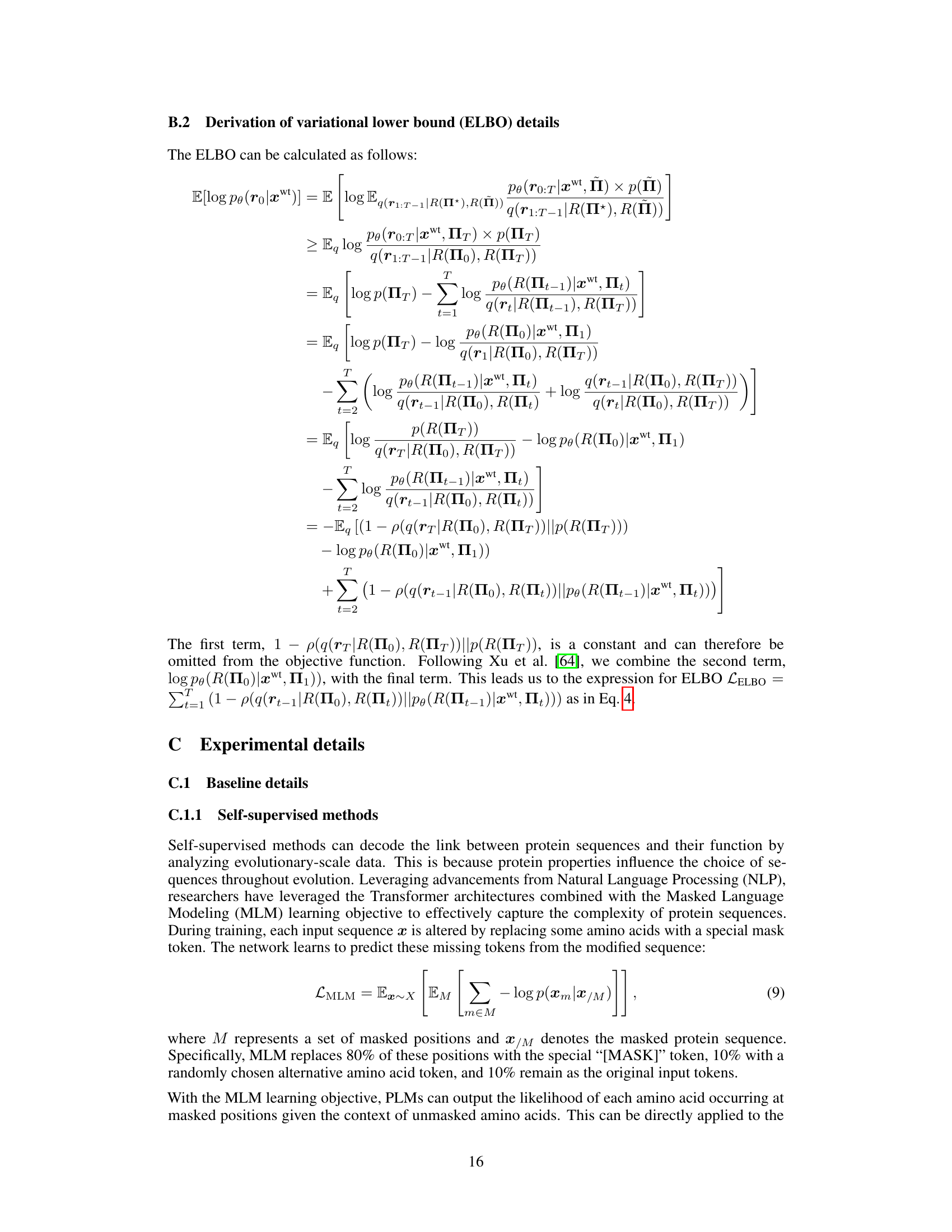

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the generalization ability of different models for protein fitness prediction. The models were tested on datasets from different protein categories. The table shows how well the models generalize to unseen protein sequences, indicating which models are more robust and less prone to overfitting. It also shows the impact of different types of data (evolutionary, structural and experimental) on model performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Generalization ability evaluation. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. The information (evolutionary, structural or experimental) involved in each model is provided. Results of unsupervised methods are borrowed from Notin et al.[43]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments. (FT=Fine-tuned version)

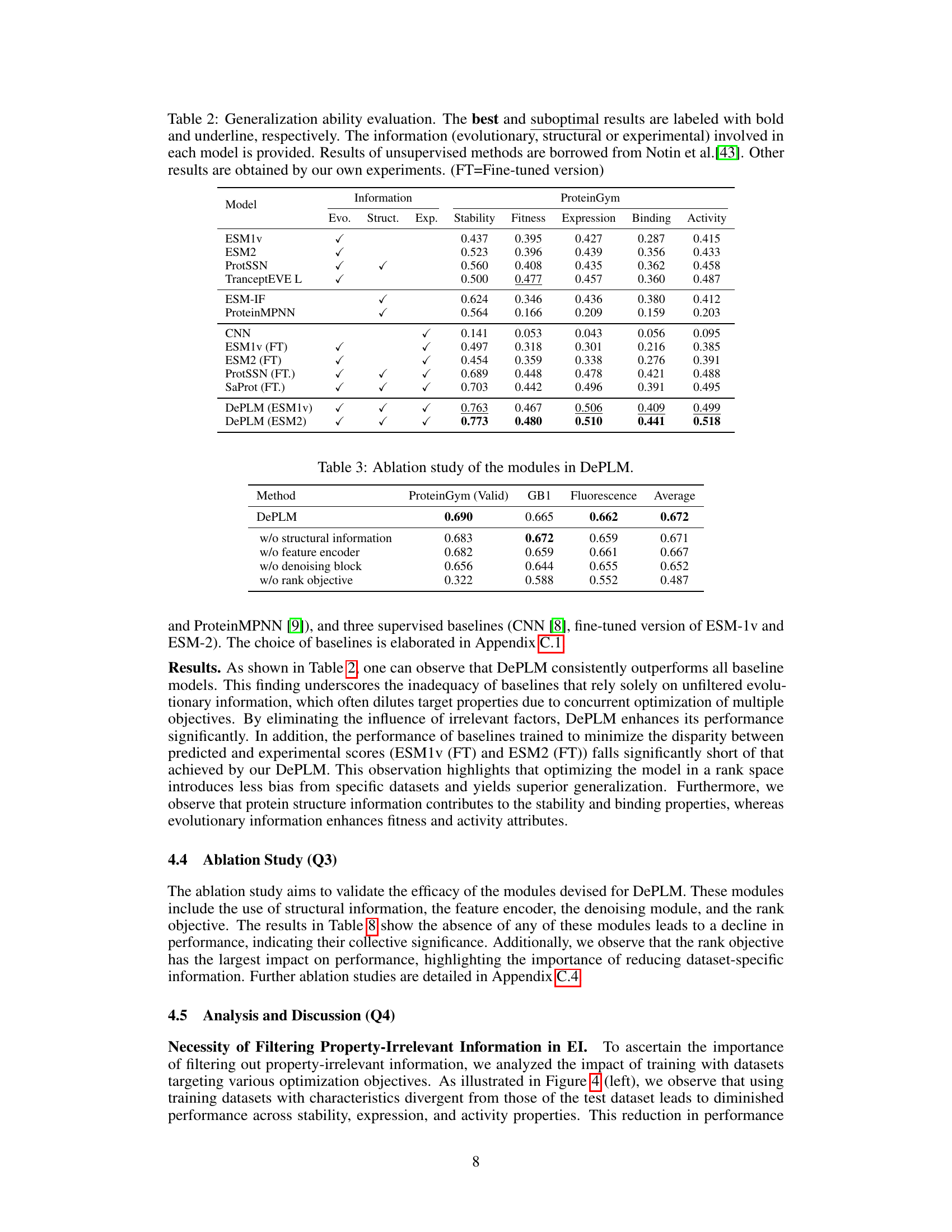

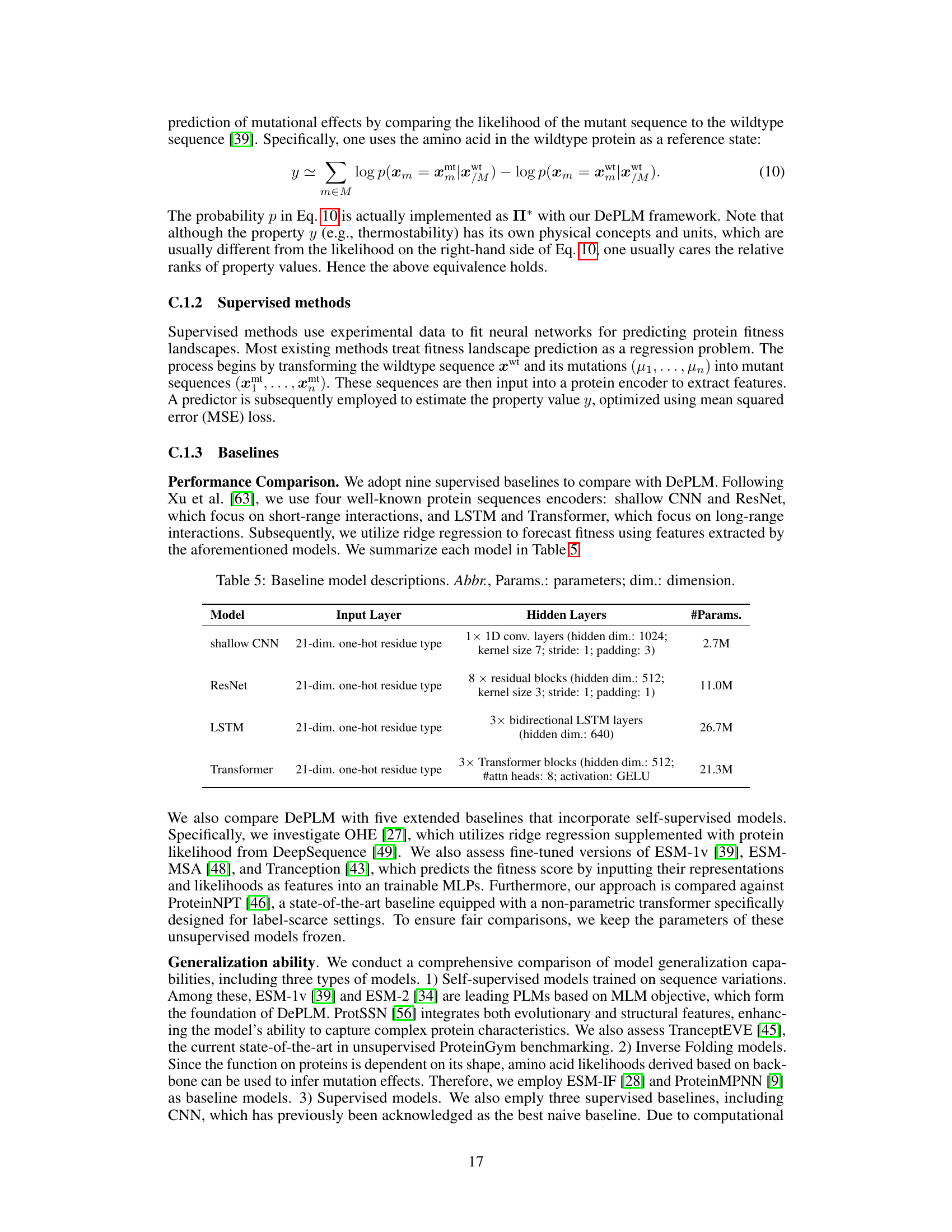

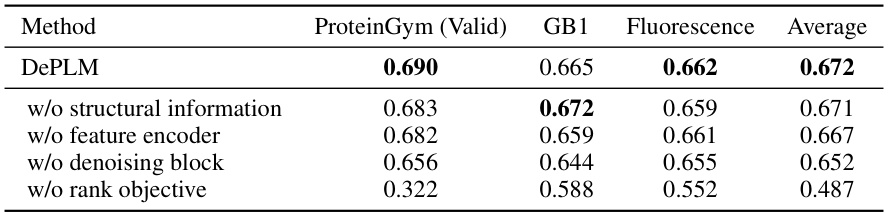

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results for DePLM, showing the impact of removing different modules on the model’s performance. The performance is measured using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient on ProteinGym (valid), GB1, and Fluorescence datasets. The modules evaluated are structural information, feature encoder, denoising block, and rank objective. The results indicate that all components contribute to the model’s performance, particularly the rank objective which significantly impacts performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study of the modules in DePLM.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of DePLM against other state-of-the-art methods on four different protein engineering tasks. The tasks assess different aspects of protein properties (stability, fitness, expression, binding, activity). For each task, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) is reported to evaluate how well the model’s predicted fitness landscape aligns with the ground truth, providing a comprehensive comparison of different approaches.

read the caption

Table 1: Model performance on protein engineering tasks. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. ProteinGym results of OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT are borrowed from Notin et al. [46]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various models’ performance on four protein engineering tasks. The tasks are from the ProteinGym dataset and involve predicting protein properties such as stability, fitness, expression, binding activity. The models compared include several baselines (CNN, ResNet, LSTM, Transformer, OHE, ESM-1v, ESM-2, ESM-MSA, ProtSSN, SaProt, Tranception, ProteinNPT) and the proposed DePLM model using ESM1v and ESM2. The performance metric is Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The best and second best results for each task are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Model performance on protein engineering tasks. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. ProteinGym results of OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT are borrowed from Notin et al. [46]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of DePLM against various baselines across four protein engineering tasks. The tasks are: ProteinGym (a multi-property dataset), B-Lactamase stability, Fluorescence expression, and GB1 binding activity. For each task, the table shows the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient achieved by each model. The best and second-best performing models for each task are highlighted. The results for ProteinGym for four other models (OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT) are taken from a previous study by Notin et al. [46].

read the caption

Table 1: Model performance on protein engineering tasks. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. ProteinGym results of OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT are borrowed from Notin et al. [46]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of various models on four protein engineering tasks: ProteinGym, B-Lactamase, Fluorescence, and GB1. The models are compared using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, a metric that assesses the ranking of model predictions relative to ground truth. The table shows that DePLM outperforms the state-of-the-art models. It includes self-supervised and supervised methods, as well as several baselines trained from scratch for comparison.

read the caption

Table 1: Model performance on protein engineering tasks. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. ProteinGym results of OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT are borrowed from Notin et al. [46]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments.

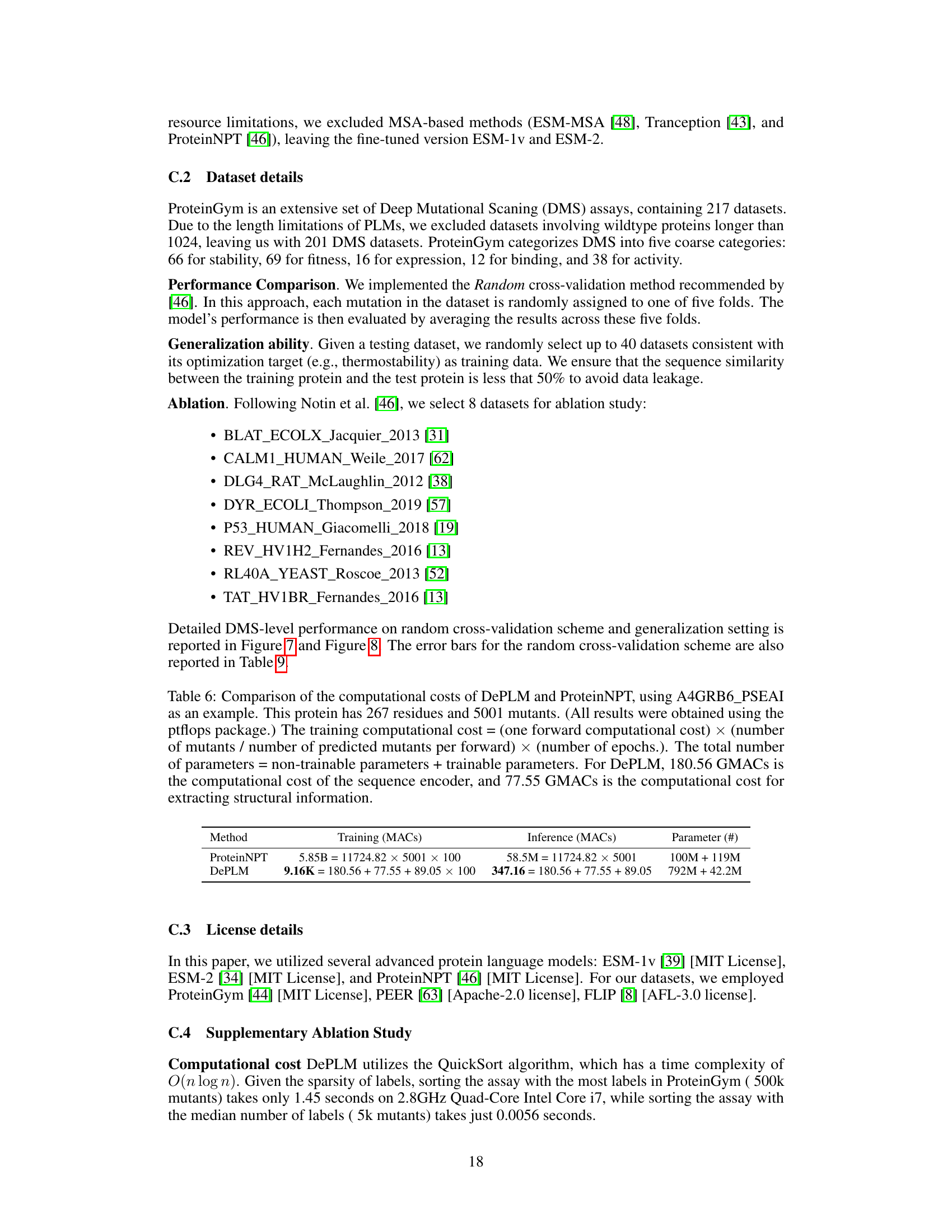

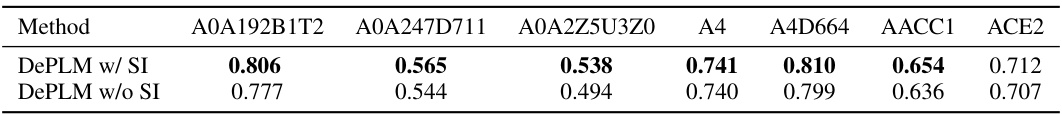

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of incorporating structural information into the DePLM model. It compares the performance of DePLM with and without structural information across different protein datasets. The Spearman correlation coefficient is used as the performance metric. Datasets are categorized by their targeted properties and performance is measured for each.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablation study of the structural information (SI).

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of DePLM against other state-of-the-art models on four protein engineering tasks (ProteinGym, B-Lactamase, Fluorescence, and GB1). The table shows the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, a measure of how well the model’s predictions match the ground truth, for each model and task. The best and second-best performing models are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively. The results for several models (OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, ProteinNPT) are taken from a previous study, while the rest are from the authors’ own experiments.

read the caption

Table 1: Model performance on protein engineering tasks. The best and suboptimal results are labeled with bold and underline, respectively. ProteinGym results of OHE, ESM-MSA, Tranception, and ProteinNPT are borrowed from Notin et al. [46]. Other results are obtained by our own experiments.

Full paper#