TL;DR#

Differential privacy (DP) is crucial for protecting data, but existing methods for managing privacy loss over multiple operations (privacy accounting) are often loose. Amplification by subsampling, a technique to enhance privacy by using random subsets of data, also suffers from loose, mechanism-agnostic guarantees. This limits the precision of privacy accounting and reduces the utility of DP in applications such as machine learning.

This research introduces a new framework for tighter, mechanism-specific amplification using subsampling and optimal transport theory. This method leverages additional information about the mechanism to derive tighter privacy bounds than previous mechanism-agnostic approaches. It unifies privacy accounting across different DP definitions (approximate DP, Rényi DP, dominating pairs), leading to more accurate privacy calculations and improved utility. The framework is applied to analyzing group privacy under subsampling, resulting in considerably tighter bounds than what is possible with traditional methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper significantly advances differential privacy research by introducing a novel framework for mechanism-specific amplification. Its unified approach simplifies privacy accounting across various DP definitions, improving accuracy and efficiency. This offers researchers more precise control over privacy and enhanced utility in machine learning applications. The work opens new avenues for exploring tight mechanism-specific bounds and refining group privacy analysis, enhancing the practical applicability of differential privacy.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of group privacy amplification under subsampling. Three users (x1, x2, x3) may independently choose to contribute data to a dataset. The dataset is then subsampled before applying a differentially private mechanism. The probabilities of subsampling show that it is unlikely for a large fraction of the group’s data to simultaneously appear in a batch. Thus, analyzing group privacy and subsampling jointly can yield stronger privacy guarantees than analyzing them separately.

read the caption

Figure 1: Group members x1, x2 contribute to a dataset, while group member x3 does not. For small subsampling rates r, it is unlikely to access a single (Pr = 2r(1 - r)) or even both (Pr = r²) inserted elements when applying a base mechanism B to a subsampled batch (e.g., the yellow one). This further obfuscates which data was contributed by members of group {x1, x2, x3}.

In-depth insights#

Unified Amplification#

The concept of “Unified Amplification” in the context of differential privacy suggests a framework that consolidates various amplification techniques under a single, unified theory. This contrasts with traditional, mechanism-agnostic approaches that provide broader, less precise bounds, while mechanism-specific approaches, while tighter, are often tailored to individual mechanisms. A unified framework offers several key advantages: improved accuracy of privacy guarantees, particularly for complex scenarios such as group privacy and composition; simplification of privacy accounting, making it easier to track privacy loss across multiple steps; and enhanced applicability to diverse mechanisms, leading to more widely applicable privacy tools and techniques. The core idea is leveraging additional information, beyond basic privacy parameters, to create tighter bounds that are more specific to the mechanisms and their use cases. This advancement is critical for developing more reliable and practical privacy-preserving machine learning algorithms. Optimal transport theory, or a similar technique, could be the core mathematical tool underpinning this unification, enabling the derivation of tighter bounds than those currently achievable with mechanism-agnostic methods. The proposed framework is likely to have significant practical implications given the increasing complexity of privacy-sensitive applications in machine learning and data analysis.

Optimal Transport#

Optimal transport (OT) is a powerful mathematical framework used to find the most efficient way to transform one probability distribution into another. In the context of differential privacy, OT provides a principled way to analyze and quantify the privacy loss incurred by differentially private mechanisms. The core idea is to leverage the cost of transforming one dataset into another to bound the privacy loss. The use of OT in this setting is particularly useful for analyzing situations where the data distributions are complex or the mechanisms are not easily characterized by traditional privacy metrics (such as epsilon and delta). The paper showcases that mechanism-specific guarantees outperforms the mechanism-agnostic ones. The research particularly focuses on mechanism-specific amplification by subsampling. It proposes a novel framework based on conditional optimal transport, allowing the derivation of tighter privacy bounds by incorporating additional information about the mechanism’s properties and the data. This approach is shown to effectively address limitations of previous frameworks that only provide mechanism-agnostic bounds, particularly in scenarios involving group privacy and complex composition of mechanisms. By using conditional optimal transport, the framework accounts for dependencies between batches of data, resulting in more accurate and efficient privacy analysis.

Group Privacy#

The concept of ‘Group Privacy’ in the context of differential privacy mechanisms focuses on providing privacy guarantees not just for individual data subjects but also for groups of individuals. A key challenge is that the composition of privacy loss from multiple individuals can dramatically weaken the overall privacy guarantees. This is especially relevant in scenarios where individuals’ data are linked or correlated, such as in social networks or collaborative projects. The paper addresses this by investigating how subsampling techniques impact the privacy amplification for groups. The findings reveal that the traditional approach of applying group privacy properties after subsampling can be quite loose, and propose a unified framework for deriving tighter, mechanism-specific bounds that leverage additional information to more accurately capture the privacy amplification effect. This framework, based on conditional optimal transport, enables more precise privacy accounting for groups of users, improving upon both existing mechanism-agnostic bounds and classic group privacy results. The practical implications are significant as they allow for more effective privacy protection in applications processing grouped data, demonstrating the importance of tightly analyzing subsampling and group privacy jointly.

Mechanism-Specific#

The concept of ‘mechanism-specific’ in the context of differential privacy (DP) research signifies a crucial shift from traditional mechanism-agnostic approaches. Mechanism-agnostic methods provide privacy guarantees based solely on the mechanism’s input and output without considering its internal workings. In contrast, mechanism-specific analysis leverages the details of a mechanism’s operation—for instance, its internal randomization or data-dependent behavior—to derive tighter privacy bounds. This results in more precise privacy accounting, especially crucial in iterative processes like those encountered in machine learning. The analysis of subsampling, a core DP technique, benefits greatly from this focus. Mechanism-specific analysis of subsampling allows researchers to move beyond worst-case scenarios, providing stronger privacy guarantees for the specific mechanism under consideration and the way it interacts with subsampling. This yields more accurate privacy calculations and tighter bounds compared to the looser guarantees offered by mechanism-agnostic approaches. Ultimately, mechanism-specific approaches pave the way for a more nuanced and effective handling of privacy in practical DP applications, where the details of a mechanism significantly impact the resulting privacy profile.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle more complex subsampling schemes, such as adaptive or correlated subsampling, would be highly valuable. This would enhance the applicability of the framework to a broader range of machine learning settings. Investigating the interaction between differential privacy and other crucial properties of machine learning models (like fairness, robustness, and explainability) is crucial, as this intersection is largely unexplored. The current focus on tight bounds could also be extended by exploring asymptotic bounds for various privacy notions and specific mechanisms, providing a high-level understanding of the behavior under different conditions. Finally, developing practical algorithms and tools that leverage the framework’s theoretical insights would significantly aid the adoption of mechanism-specific amplification in real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

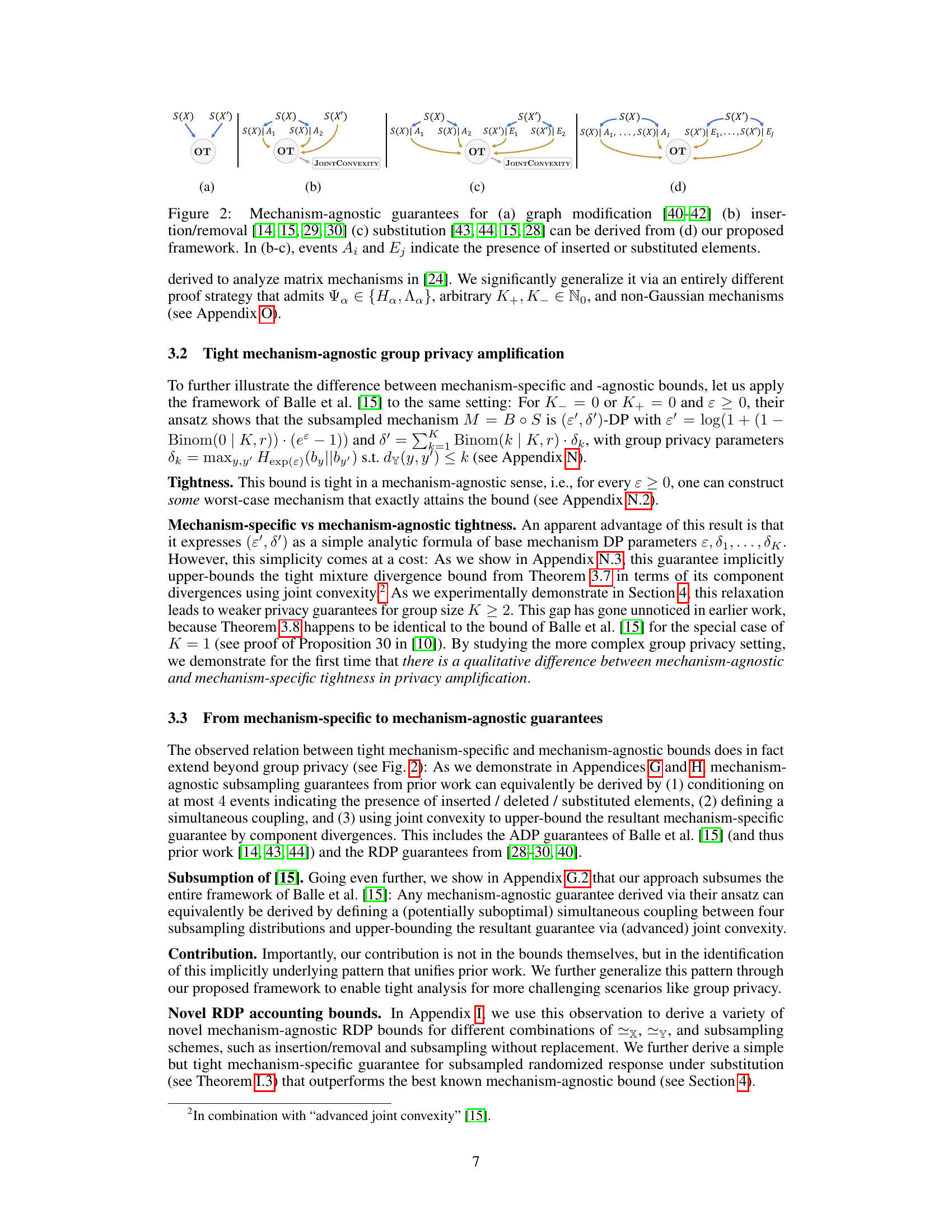

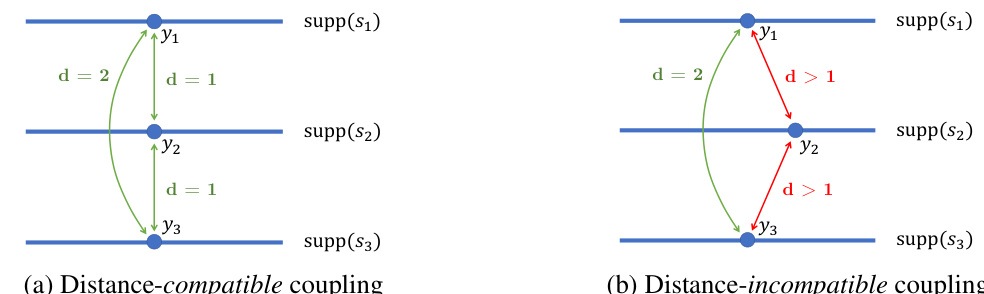

🔼 This figure illustrates how the mechanism-agnostic guarantees for different types of neighboring relations (graph modification, insertion/removal, and substitution) can be derived using the proposed framework, which utilizes optimal transport to derive mechanism-specific guarantees. It shows how the mechanism-agnostic guarantees are obtained by simplifying the calculations using joint convexity (indicated by ‘JOINT CONVEXITY’), which results in less tight bounds compared to mechanism-specific ones. The figure uses simplified notation with events A1 and Ej representing the presence of inserted or substituted elements in the subsampled batches.

read the caption

Figure 2: Mechanism-agnostic guarantees for (a) graph modification [40–42] (b) insertion/removal [14, 15, 29, 30] (c) substitution [43, 44, 15, 28] can be derived from (d) our proposed framework. In (b–c), events A₁ and Ej indicate the presence of inserted or substituted elements.

🔼 This figure compares mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic RDP guarantees for randomized response with subsampling without replacement (WOR). The x-axis represents the RDP order α, and the y-axis represents the RDP parameter ρ(α). Different lines correspond to different true response probabilities (θ). The figure shows that the mechanism-specific guarantees (solid lines) are significantly tighter than the mechanism-agnostic guarantees (dashed lines) across a wide range of α values and θ values.

read the caption

Figure 3: Randomized response with WOR subsampling (q / N = 0.001), group size 1, and varying true response probability θ.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic bounds for randomized response with subsampling without replacement. The x-axis represents the Rényi divergence parameter α, and the y-axis represents the RDP parameter ρ(α). Different lines represent different values of the true response probability θ. The figure demonstrates that the mechanism-specific bounds achieve much lower ρ values across a range of α compared to the mechanism-agnostic bounds.

read the caption

Figure 3: Randomized response with WOR subsampling (q / N = 0.001), group size 1, and varying true response probability θ.

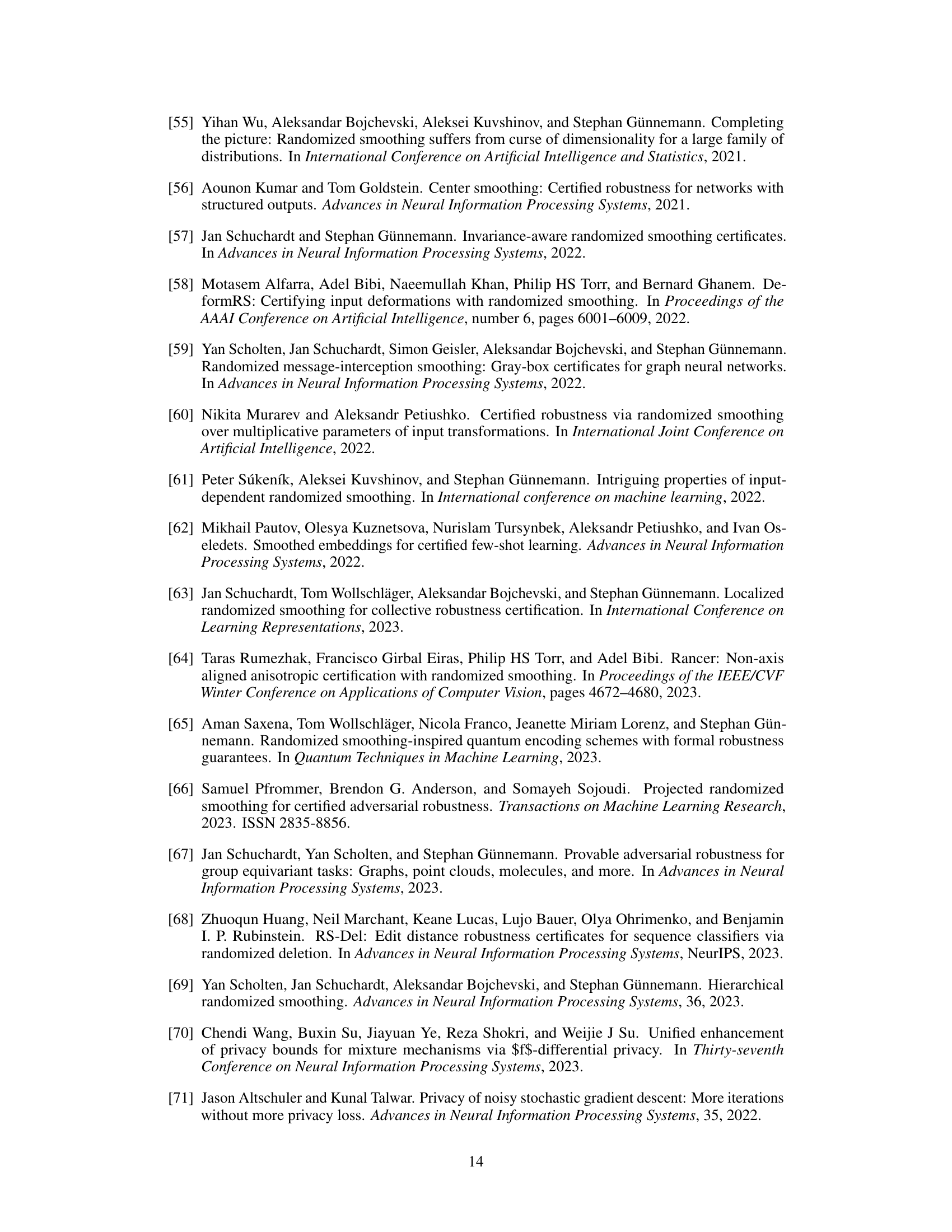

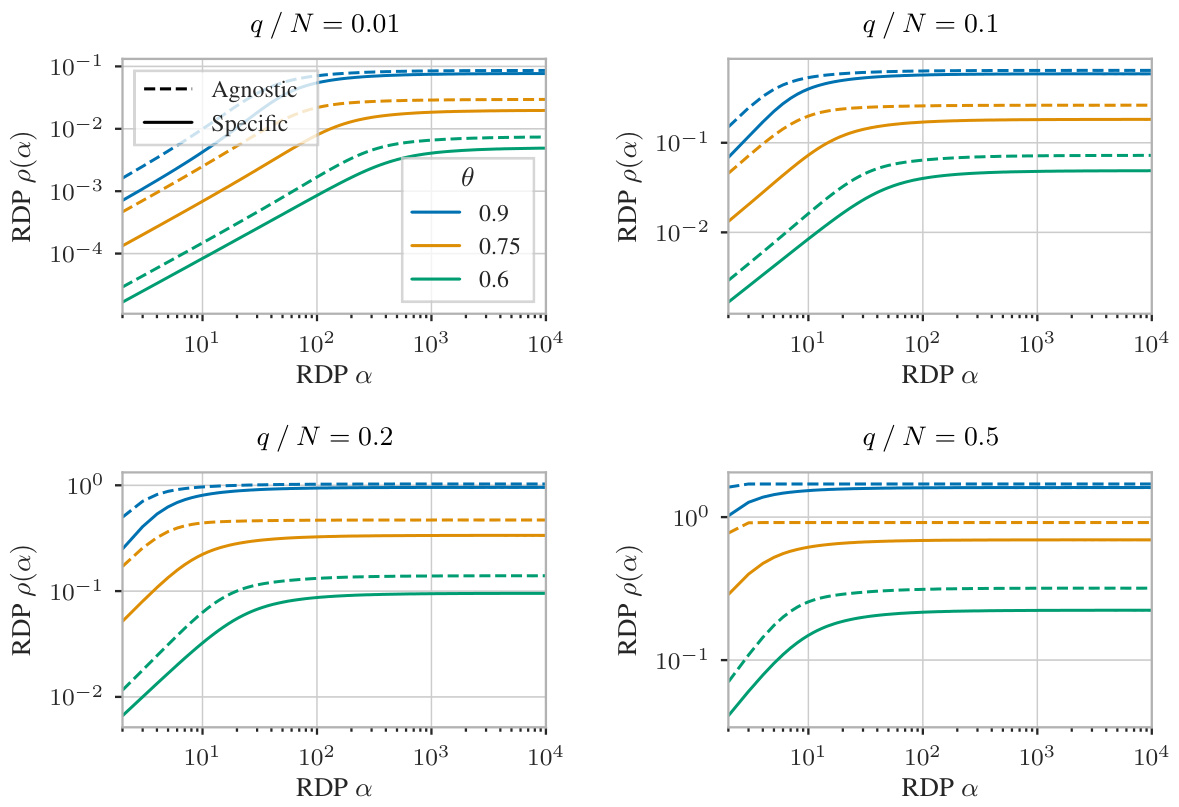

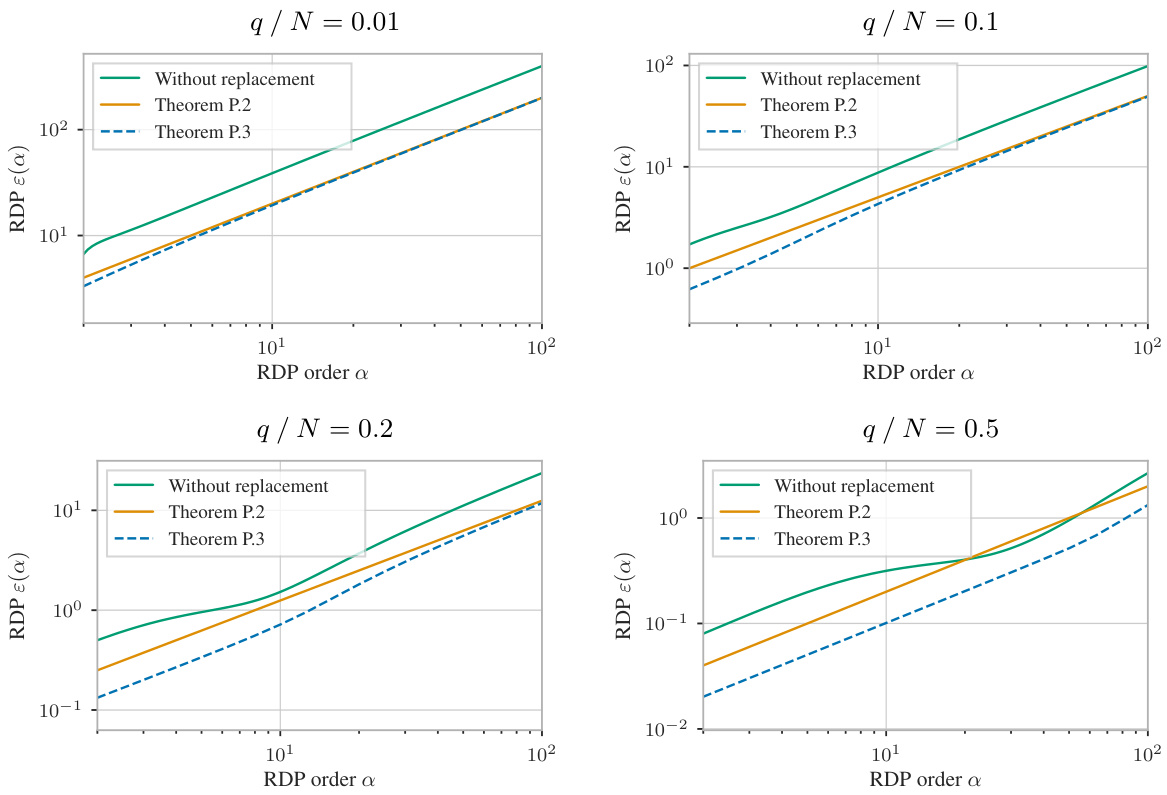

🔼 This figure compares the mechanism-specific RDP guarantees from Theorem I.3 with the mechanism-agnostic RDP guarantees from Wang et al. [28] for randomized response under subsampling without replacement. The results demonstrate that mechanism-specific analysis can lead to much stronger privacy guarantees. The improvements are more significant for smaller ratios of batch size to dataset size and across a wide range of Rényi divergence parameter α.

read the caption

Figure 7: Randomized response under subsampling without replacement, with varying true response probability θ and batch-to-dataset ratio q / N. Theorem I.3 significantly improves upon the baseline for a wide range of α.

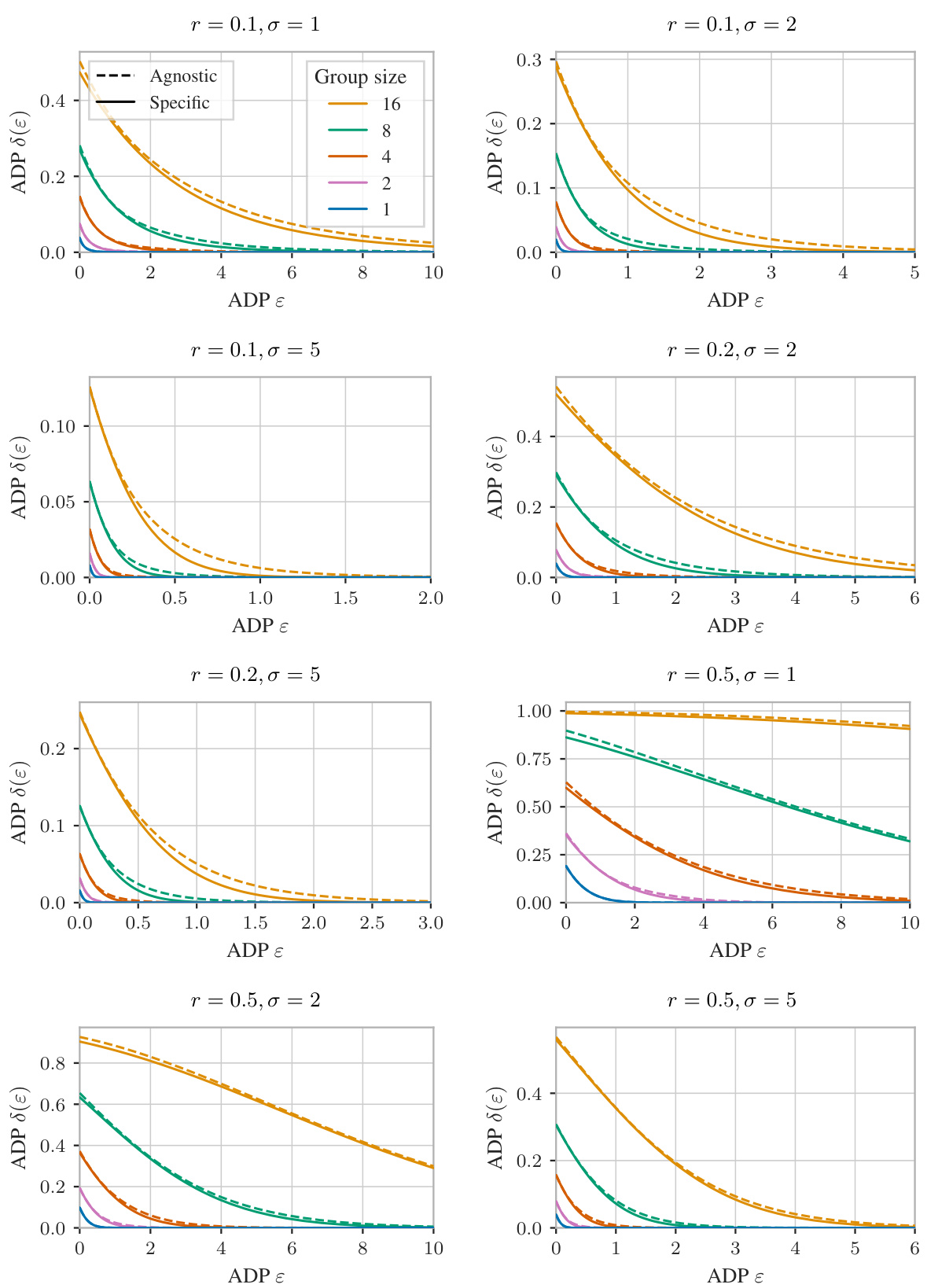

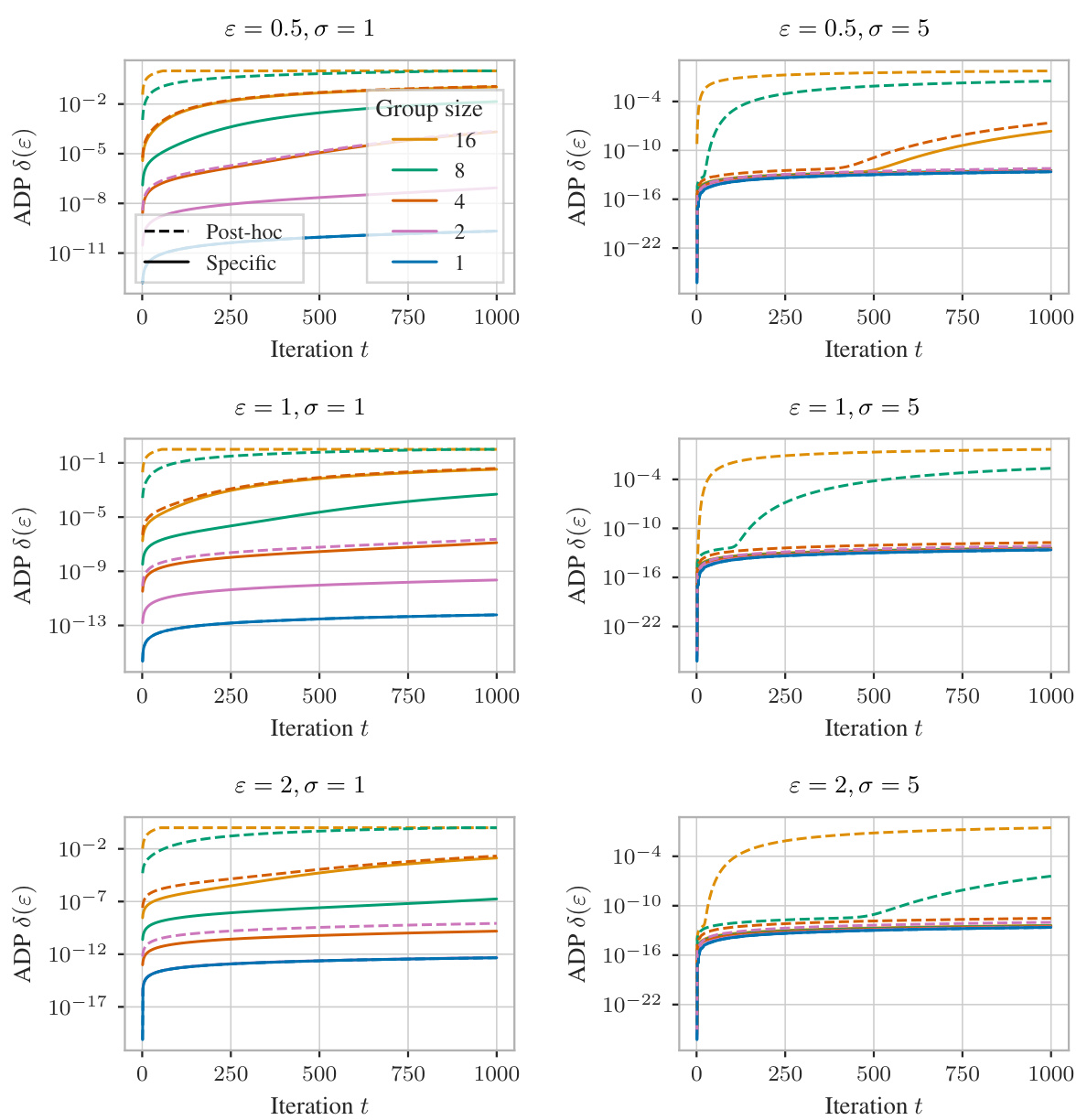

🔼 This figure compares the performance of tight mechanism-specific and tight mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification bounds under different settings. It shows how the privacy guarantees (ADP δ(ε)) change with varying standard deviations (σ), subsampling rates (r), and group sizes. The results demonstrate that mechanism-specific bounds provide stronger privacy guarantees, particularly when group sizes are larger and subsampling rates are smaller.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of tight mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification bounds for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. It shows how the privacy guarantees (measured by ADP δ(ε)) change with different standard deviations (σ), subsampling rates (r), and group sizes. The results demonstrate that mechanism-specific bounds provide significantly stronger privacy guarantees, especially when the group size is large and the subsampling rate is small. This highlights the value of the mechanism-specific analysis proposed in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

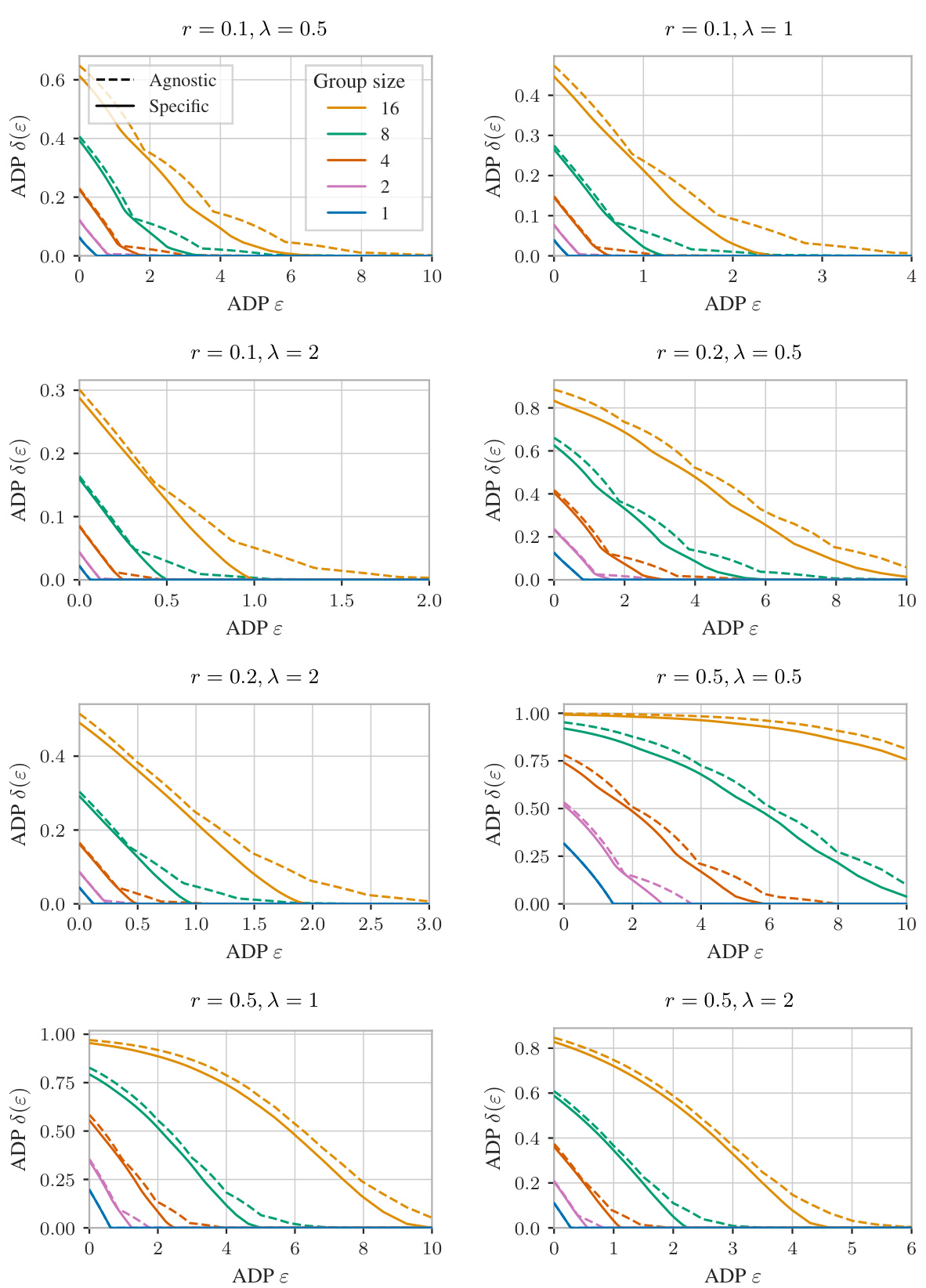

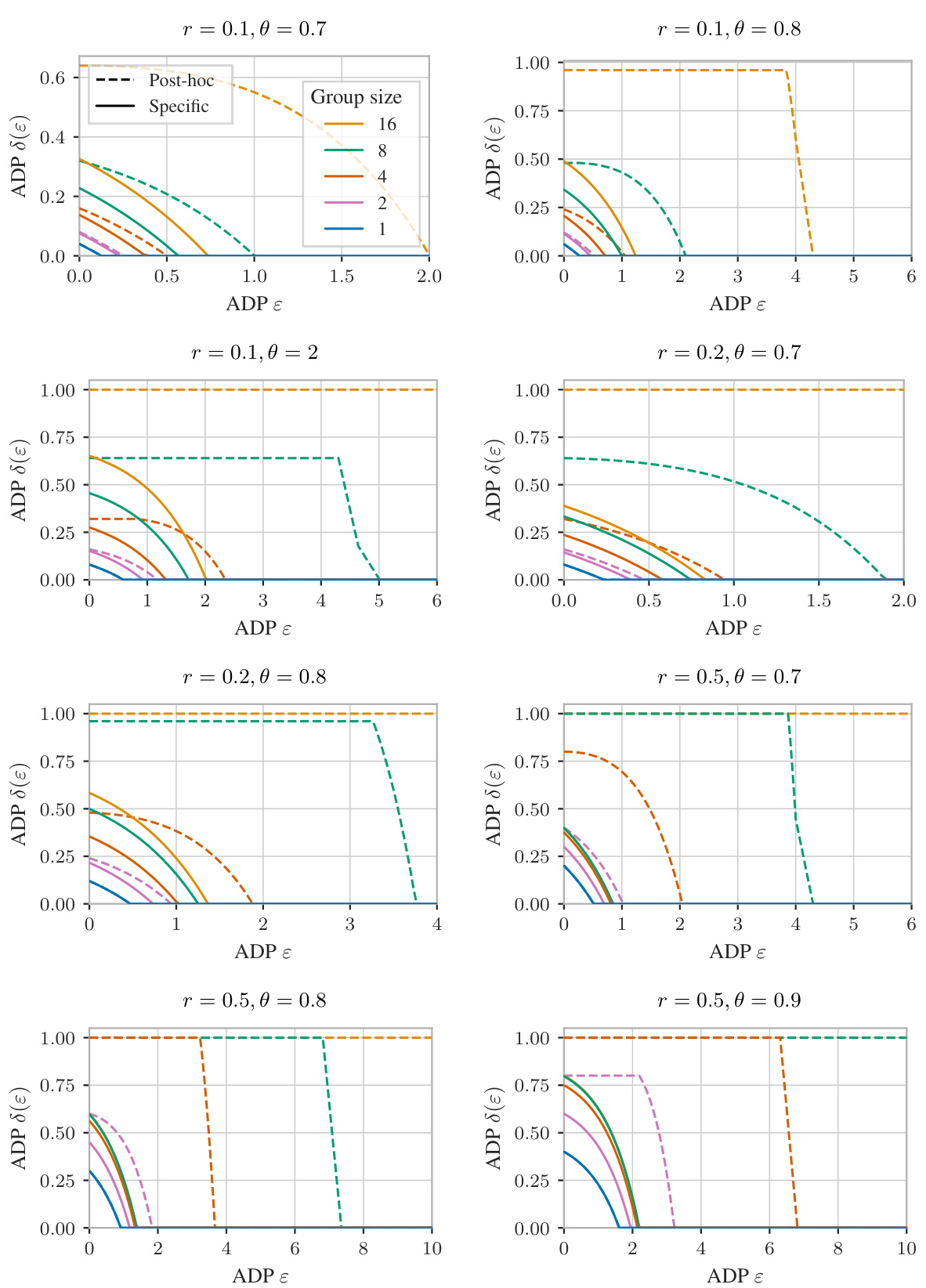

🔼 This figure compares the mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic guarantees for randomized response under Poisson subsampling with different group sizes, true response probabilities, and subsampling rates. The results show that a joint analysis of group privacy and subsampling leads to tighter bounds compared to the post-hoc application of group privacy to individually obtained subsampling guarantees.

read the caption

Figure 10: Randomized response under Poisson subsampling, with varying true response probability θ, subsampling rate r, and group size. Analyzing group privacy and subsampling jointly instead of in a post-hoc manner often yields stronger guarantees.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of tight mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification bounds for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. The x-axis represents the privacy parameter (epsilon) and the y-axis represents the privacy loss (delta). Different lines represent different group sizes and subsampling rates, while the standard deviation is constant within each subplot. The results demonstrate that mechanism-specific guarantees provide stronger privacy protection compared to mechanism-agnostic ones, particularly when dealing with larger group sizes and lower subsampling rates.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

🔼 This figure compares RDP guarantees obtained from three different methods: (1) the mechanism-agnostic guarantee from Wang et al. [28], (2) the post-hoc application of group privacy to our mechanism-specific guarantee for a single user, and (3) our proposed mechanism-specific guarantee (Proposition H.7, Theorem 3.3). For all considered dataset size N, batch size q, and group sizes, our proposed method outperforms the baselines. In some settings, it offers considerably stronger privacy guarantees.

read the caption

Figure 12: Proposition H.7 derived from Theorem 3.3 applied to Gaussian mechanism (σ = 5.0) under sampling without replacement for varying dataset size N, batch size q, and group size. Optimal transport without conditioning does not always improve upon the baseline.

🔼 This figure compares the mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic guarantees for randomized response with subsampling without replacement. The x-axis represents the Rényi-DP parameter α, and the y-axis represents the RDP parameter ρ(α). Multiple lines are shown for different true response probabilities θ. The figure demonstrates that the mechanism-specific guarantees (the solid lines) are significantly tighter than the mechanism-agnostic guarantees (the dashed lines), especially for larger values of α. This highlights the benefit of using mechanism-specific amplification analysis to obtain tighter privacy guarantees.

read the caption

Figure 3: Randomized response with WOR subsampling (q/N = 0.001), group size 1, and varying true response probability θ.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of tight mechanism-specific and tight mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification bounds for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. The x-axis represents the privacy parameter ε (epsilon), and the y-axis represents the privacy parameter δ (delta). Different lines represent different group sizes and subsampling rates (r). The results show that the mechanism-specific bounds consistently outperform the mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates (r). This highlights the benefit of using mechanism-specific analysis instead of relying on mechanism-agnostic bounds when analyzing group privacy under subsampling.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

🔼 This figure compares the mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification bounds for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. The x-axis represents the privacy parameter epsilon (ADP) and the y-axis represents the privacy parameter delta (ADP). Different lines represent different group sizes (1, 2, 4, 8, 16). Each subplot represents a different combination of subsampling rate r (0.1, 0.2, 0.5) and standard deviation σ (1, 2, 5). The results show that the mechanism-specific bounds provide stronger privacy guarantees, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates. This highlights the impact of leveraging additional information beyond the mechanism’s privacy parameters to more tightly characterize the subsampled mechanism’s privacy.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of tight mechanism-specific and tight mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification guarantees for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. The x-axis represents the ADP parameter epsilon (ε), and the y-axis represents the ADP parameter delta (δ). Different lines represent different group sizes (1, 2, 4, 8, 16) and different values for the subsampling rate (r) and the standard deviation (σ). The results demonstrate that mechanism-specific bounds provide significantly stronger privacy guarantees, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of tight mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification guarantees for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. The results are presented for various standard deviations (σ), subsampling rates (r), and group sizes. The key finding is that mechanism-specific guarantees provide stronger privacy protection, particularly for larger group sizes and lower subsampling rates. The difference in performance between the two types of guarantees increases as the group size grows and the subsampling rate decreases.

read the caption

Figure 8: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. The tight mechanism-specific guarantees are stronger than the tight mechanism-agnostic bounds, especially for larger group sizes and smaller subsampling rates.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic RDP guarantees for randomized response under subsampling without replacement (WOR) with a batch-to-dataset ratio of 0.001 and group size 1. The x-axis represents the Rényi-DP parameter α, while the y-axis shows the RDP parameter ρ(α). Different lines represent different values of the true response probability θ (0.6, 0.75, and 0.9). The figure demonstrates that the mechanism-specific guarantees achieve significantly tighter bounds than the mechanism-agnostic ones, especially for larger values of α.

read the caption

Figure 3: Randomized response with WOR subsampling (q / N = 0.001), group size 1, and varying true response probability θ.

🔼 This figure shows the comparison of RDP guarantees obtained using mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic analysis for randomized response with subsampling without replacement. The x-axis represents the Rényi divergence parameter α, while the y-axis shows the RDP parameter ρ(α). Different lines represent different values of the true response probability θ. The figure demonstrates that the mechanism-specific analysis provides significantly tighter bounds compared to the mechanism-agnostic approach.

read the caption

Figure 3: Randomized response with WOR subsampling (q/N = 0.001), group size 1, and varying true response probability θ.

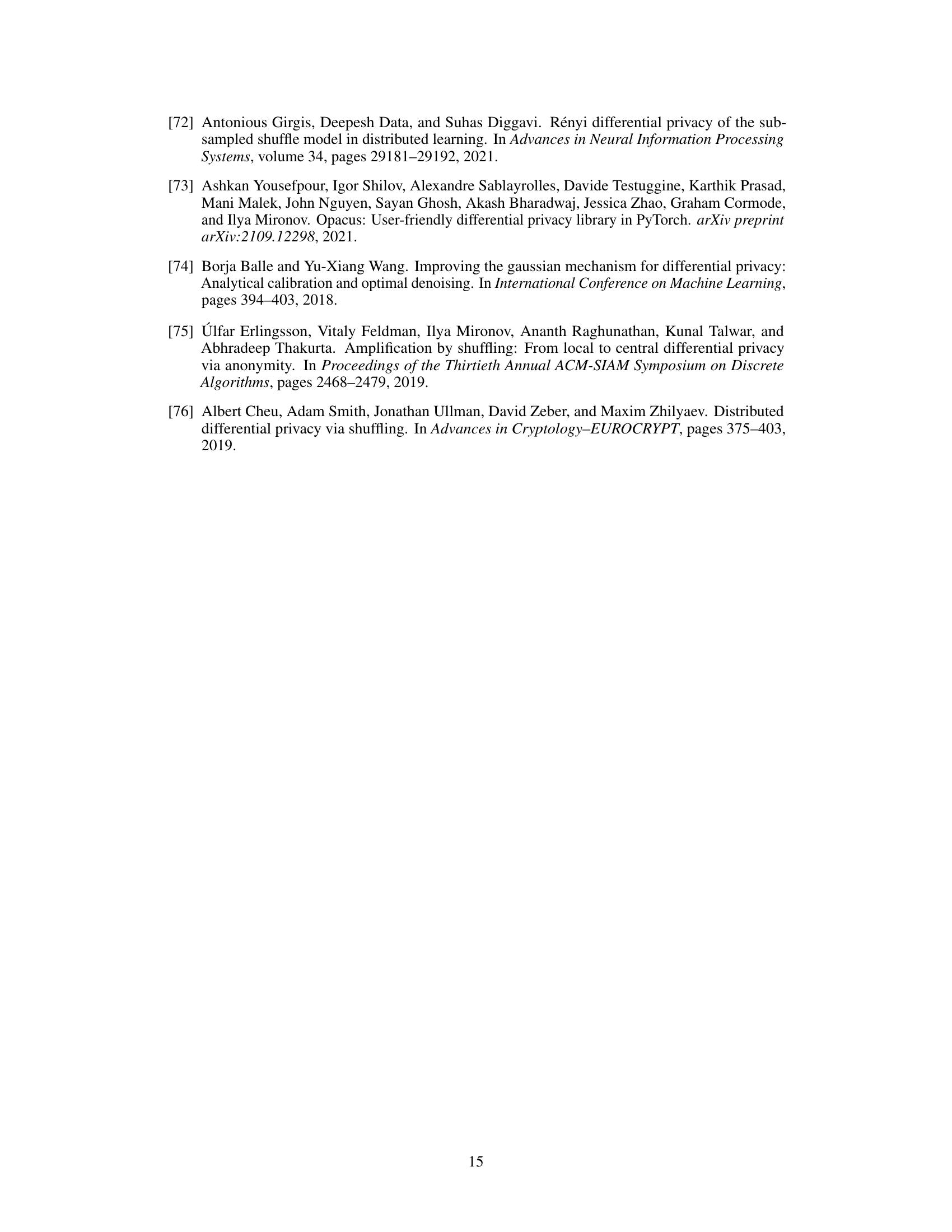

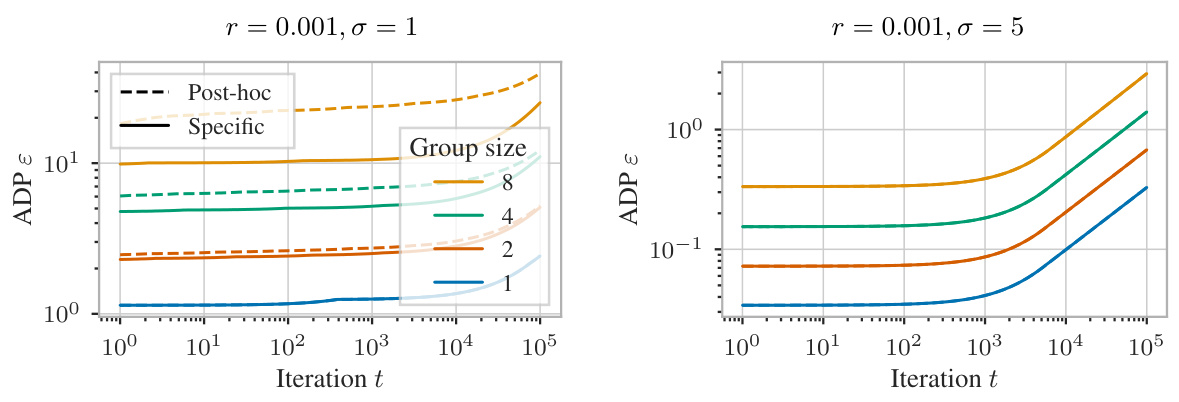

🔼 This figure compares the performance of mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic bounds for Laplace mechanisms under Poisson subsampling with varying group sizes. The mechanism-specific bounds, derived using the authors’ proposed framework, provide tighter privacy guarantees than the mechanism-agnostic bounds, particularly for larger group sizes. The ‘post-hoc’ approach represents applying the group privacy property to individual privacy guarantees. The results demonstrate the advantage of the mechanism-specific approach, especially as the group size increases.

read the caption

Figure 4: Laplace mechanisms with scale λ = 1, Poisson subsampling (r = 0.2), and varying group size.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic group privacy amplification bounds for Laplace mechanisms under Poisson subsampling with a scale of 1 and a subsampling rate of 0.2. The results are shown for varying group sizes. Mechanism-specific bounds, derived using the proposed framework, are shown to provide tighter privacy guarantees compared to mechanism-agnostic bounds for group sizes greater than 1. The post-hoc application of the group privacy property to mechanism-specific bounds for a group size of 1 is also presented as a baseline. The figure highlights the quantitative difference between mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic tightness in privacy amplification.

read the caption

Figure 4: Laplace mechanisms with scale λ = 1, Poisson subsampling (r = 0.2), and varying group size.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of mechanism-specific group privacy amplification and post-hoc group privacy analysis for Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling. The x-axis represents the privacy parameter epsilon (ε) and the y-axis represents the privacy parameter delta (δ) in approximate differential privacy. Multiple lines are shown for different group sizes and different subsampling rates (r) and standard deviations (σ) of the Gaussian mechanism. The plot demonstrates that jointly analyzing group privacy and subsampling (the ‘Specific’ lines) provides tighter privacy guarantees than applying the group privacy property post-hoc to mechanism-specific bounds for individual privacy (the ‘Post-hoc’ lines). Specifically, the mechanism-specific analysis provides stronger guarantees especially for larger group sizes and lower subsampling rates.

read the caption

Figure 14: Gaussian mechanisms under Poisson subsampling, with varying standard deviation σ, subsampling rate r, and group size. Analyzing group privacy and subsampling jointly instead of in a post-hoc manner offers stronger guarantees.

🔼 This figure compares mechanism-specific and mechanism-agnostic RDP guarantees for randomized response under subsampling without replacement. The x-axis represents the RDP order α, and the y-axis represents the RDP parameter ρ(α). Different curves represent different values of the true response probability θ. The figure demonstrates that mechanism-specific guarantees are significantly tighter than mechanism-agnostic bounds for a wide range of α values, particularly for smaller values of θ. This highlights the benefits of using mechanism-specific analysis for privacy accounting when using randomized response mechanisms.

read the caption

Figure 3: Randomized response with WOR subsampling (q/N = 0.001), group size 1, and varying true response probability θ.

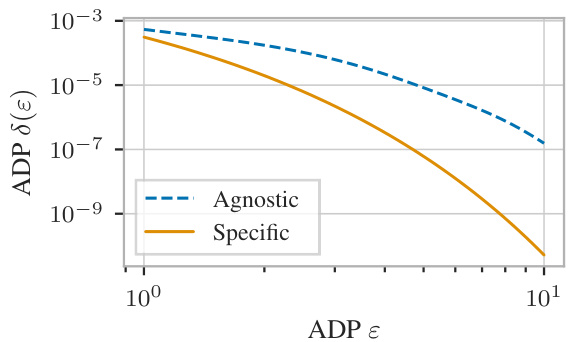

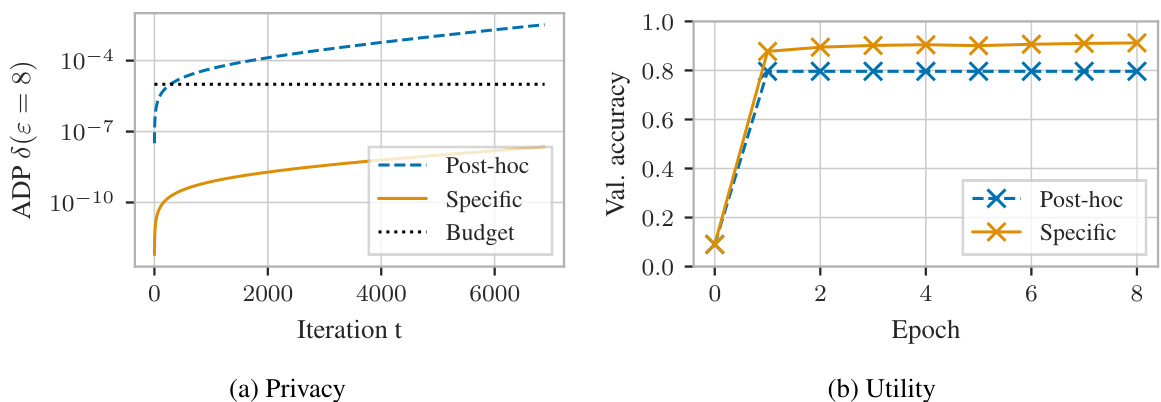

🔼 This figure shows the results of a differentially private training of a convolutional neural network on the MNIST dataset. The experiment compares two methods of privacy accounting: a post-hoc approach, which applies group privacy to single-user privacy bounds, and the authors’ tight mechanism-specific approach. The left panel displays the privacy leakage (ADP δ) over the number of iterations. The right panel illustrates the resulting validation accuracy of the models trained using each method. The mechanism-specific approach allows for more training iterations resulting in higher validation accuracy with similar or less privacy leakage.

read the caption

Figure 24: Differentially private training of a 2-layer convolutional network on MNIST with PLD accounting for group size 2. Our tight mechanism-specific analysis allows us to train for significantly more epochs or to terminate training after 8 epochs with less privacy leakage and higher accuracy.

🔼 This figure shows how mechanism-agnostic guarantees for different data modification types (graph modification, insertion/removal, and substitution) can be derived using the proposed framework. Specifically, it highlights that these existing guarantees are implicitly derived using a pessimistic upper bound based on joint convexity and a coupling of multiple subsampling distributions (similar to what is achieved by recursively applying Lemma 3.1 in Theorem 3.3). The figure uses events A₁ and Ej to illustrate how the presence of inserted or substituted elements relates to these guarantees.

read the caption

Figure 2: Mechanism-agnostic guarantees for (a) graph modification [40–42] (b) insertion/removal [14, 15, 29, 30] (c) substitution [43, 44, 15, 28] can be derived from (d) our proposed framework. In (b–c), events A₁ and Ej indicate the presence of inserted or substituted elements.

🔼 This figure shows how mechanism-agnostic guarantees for different neighboring relations can be derived from the proposed framework. It illustrates the relationship between the proposed framework and previous work by showing how prior work implicitly uses the concept of joint convexity and optimal transport, albeit with limitations. The figure contrasts the mechanism-agnostic approach (a, b, c) with the mechanism-specific approach (d) showing the progression from mechanism-agnostic bounds derived from simpler, less-informative relations to a more comprehensive, tighter mechanism-specific guarantee. The use of events A₁ and Ej highlights the importance of considering additional information beyond basic privacy parameters to derive stronger guarantees.

read the caption

Figure 2: Mechanism-agnostic guarantees for (a) graph modification [40-42] (b) insertion/removal [14, 15, 29, 30] (c) substitution [43, 44, 15, 28] can be derived from (d) our proposed framework. In (b-c), events A₁ and Ej indicate the presence of inserted or substituted elements.

🔼 This figure shows how mechanism-agnostic guarantees for graph modification, insertion/removal, and substitution can be derived using the proposed framework. It highlights that mechanism-agnostic guarantees are obtained by (1) partitioning the subsampling distributions, (2) applying advanced joint convexity, (3) applying joint convexity, and (4) defining couplings involving only two distributions. The figure uses events A1 and Ej, which represent the presence of inserted or substituted elements, to show that mechanism-agnostic approaches might not fully capture the details of mechanism-specific behavior.

read the caption

Figure 2: Mechanism-agnostic guarantees for (a) graph modification [40–42] (b) insertion/removal [14, 15, 29, 30] (c) substitution [43, 44, 15, 28] can be derived from (d) our proposed framework. In (b–c), events A₁ and Ej indicate the presence of inserted or substituted elements.

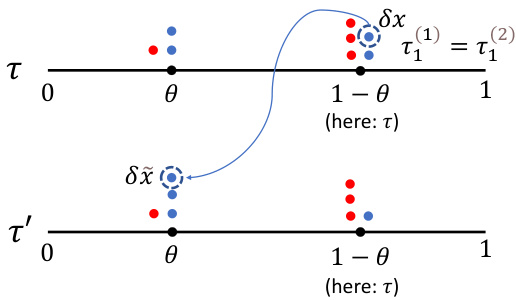

🔼 This figure compares three different methods for calculating Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) guarantees for a two-step subsampling process: permute-and-partition with and without conditioning, and subsampling without replacement. The base mechanism used is a Gaussian mechanism with varying standard deviations (σ). The plot shows that the method using optimal transport with conditioning (Theorem P.3) generally provides stronger privacy guarantees, especially for smaller values of σ. As σ increases, the results from Theorem P.3 and subsampling without replacement become more similar.

read the caption

Figure 28: Comparison of our epoch-level permute-and-partition guarantees with (Theorem P.3) and without (Theorem P.2) conditioning, as well as subsampling without replacement, for 2-fold non-adaptive composition. The base mechanism is a Gaussian mechanism with f : Y → {0,1} and varying standard deviations σ. With increasing σ, Theorem P.3 and subsampling without replacement become more similar, while Theorem P.3 consistently yields stronger guarantees.

Full paper#