TL;DR#

Federated Learning (FL) enables collaborative model training without sharing private data. However, in cross-silo FL (organizations engaging in business activities), self-interest and competition among participants pose significant challenges, leading to issues like free-riding (benefitting from others’ contributions without contributing) and conflicts of interest. Existing FL solutions often fail to address these intertwined challenges.

This paper introduces FedEgoists, a novel framework to tackle these issues. FedEgoists introduces two principles: 1) ensuring that participants benefit only if they contribute to the ecosystem and 2) preventing contributions to competitors or their allies. Using graph theory and efficient algorithms, it groups participants into optimal coalitions where they share the same interests. Experimental results show FedEgoists’ superior performance, creating efficient collaborative networks even in complex, competitive cross-silo FL settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses critical issues in cross-silo federated learning, a rapidly growing field. By proposing a novel solution that handles self-interest and competition among participants, it opens new avenues for research on efficient and robust collaboration strategies in decentralized machine learning. The findings are valuable for researchers working on real-world FL applications and provide insights into optimal coalition formation in competitive settings. Its rigorous theoretical analysis and empirical validation on benchmark datasets make it a significant contribution to the field.

Visual Insights#

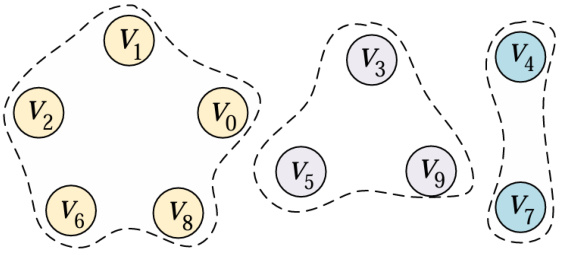

🔼 This figure illustrates the main motivation and results of the paper. In cross-silo federated learning (FL) within the business sector, companies are self-interested and often compete. The challenge lies in forming collaborations that prevent free-riding (where some companies benefit without contributing) and conflicts of interest. This paper proposes a solution, FedEgoists, which addresses these challenges by ensuring that a company benefits from FL only if it also benefits the ecosystem and avoiding collaborations with competitors or their allies. The figure visually depicts this process: companies initially compete (top left), but FedEgoists organizes them into optimized coalitions (right), avoiding free riders and conflicts, while a central FL Manager oversees the process.

read the caption

Figure 1: An overview of the main motivation and results of this paper.

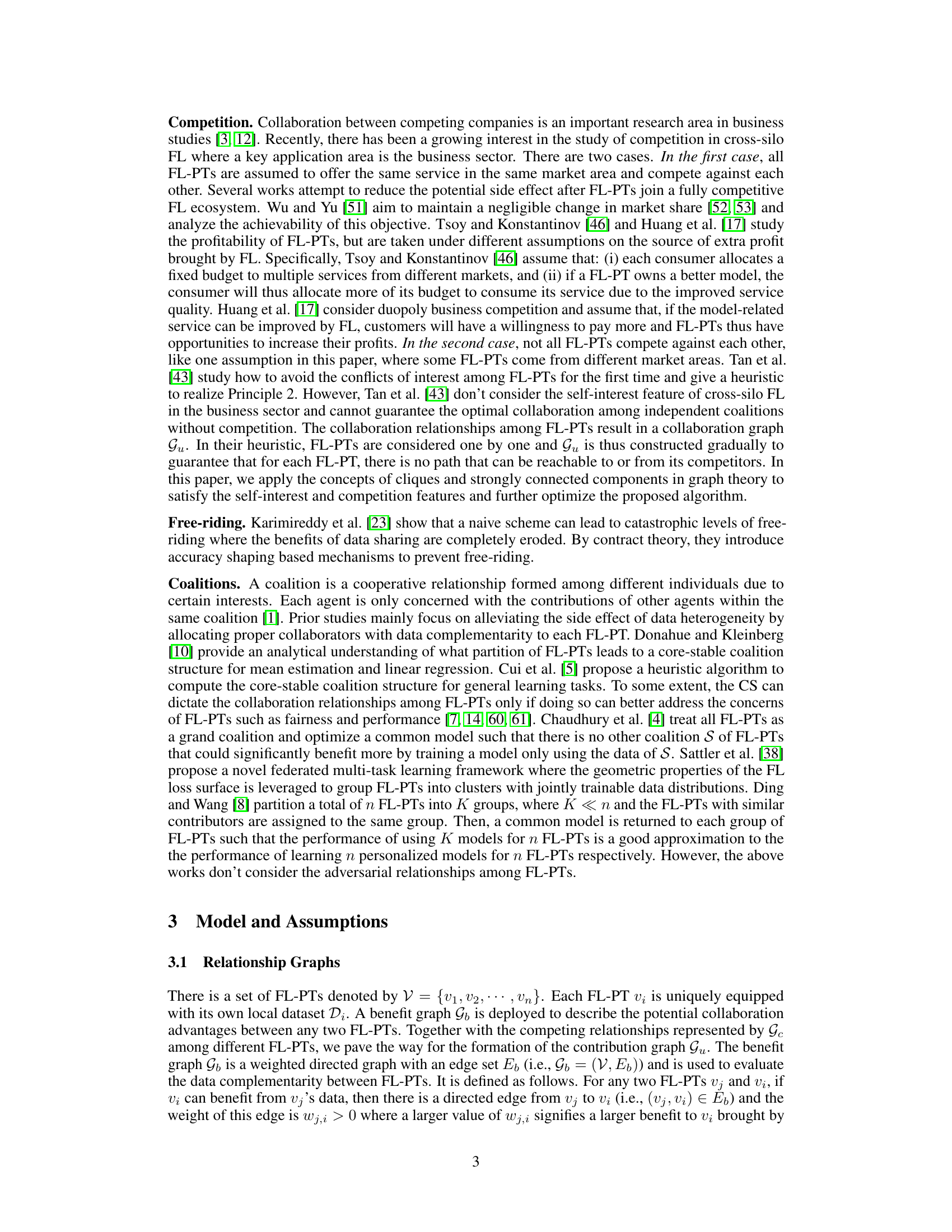

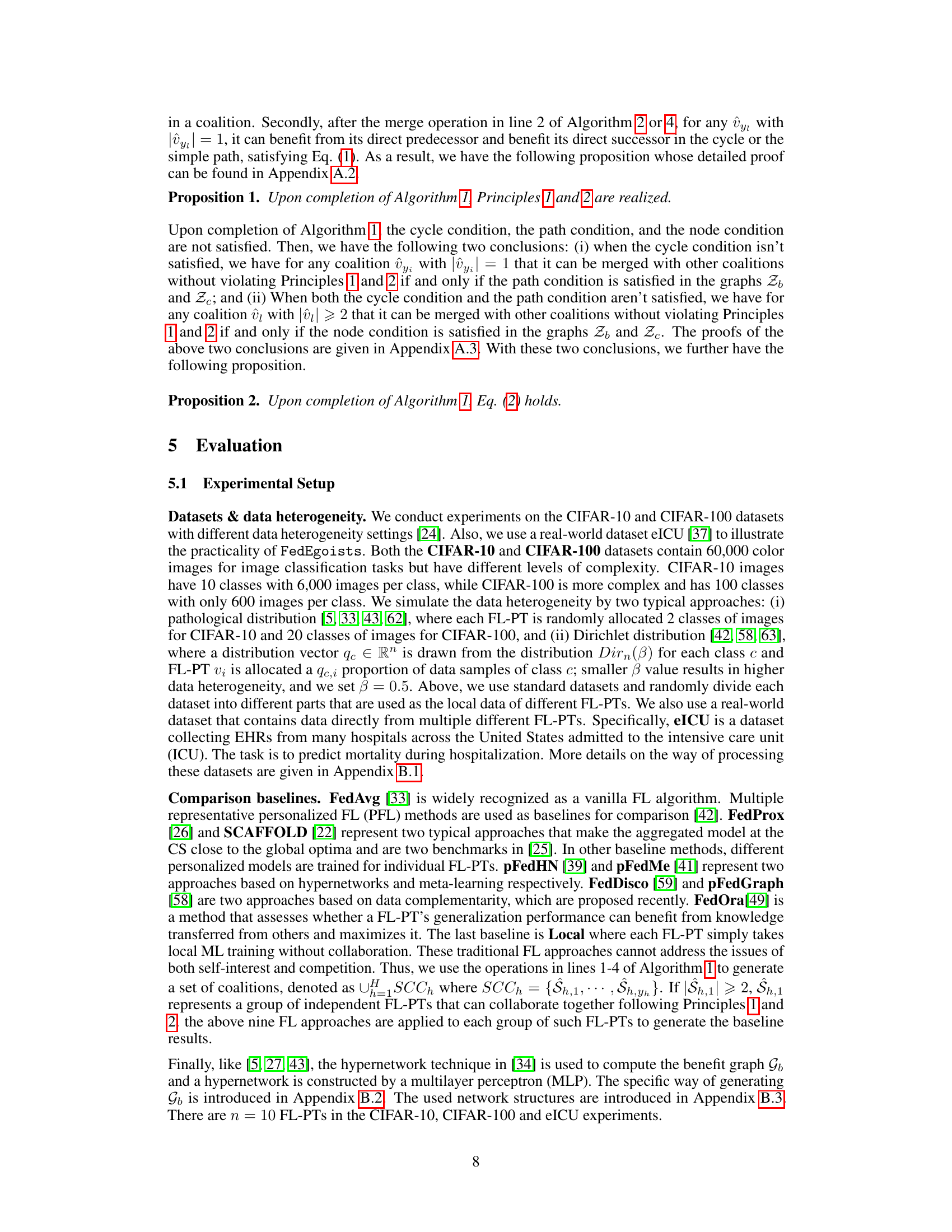

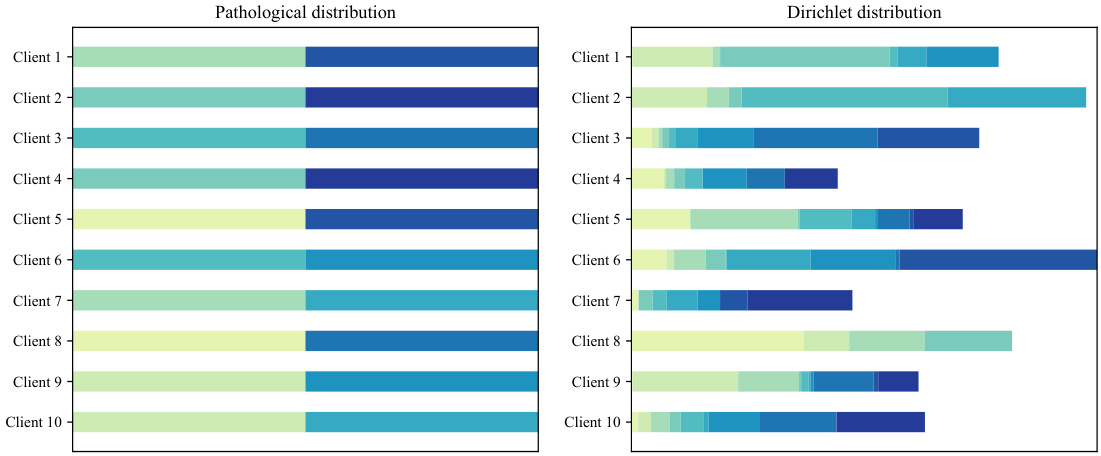

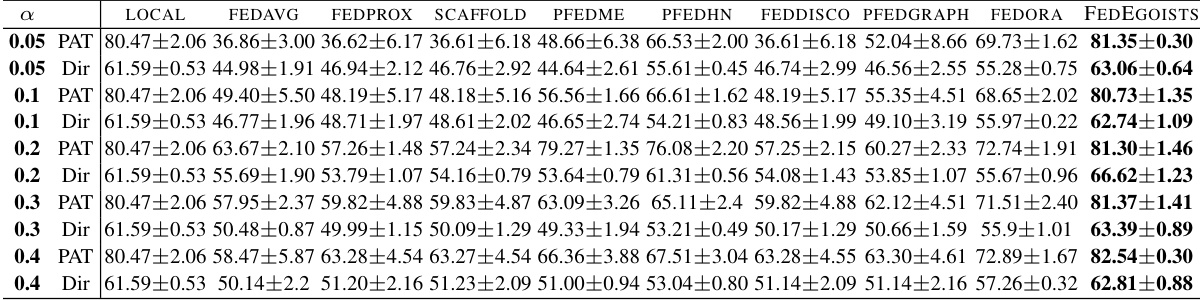

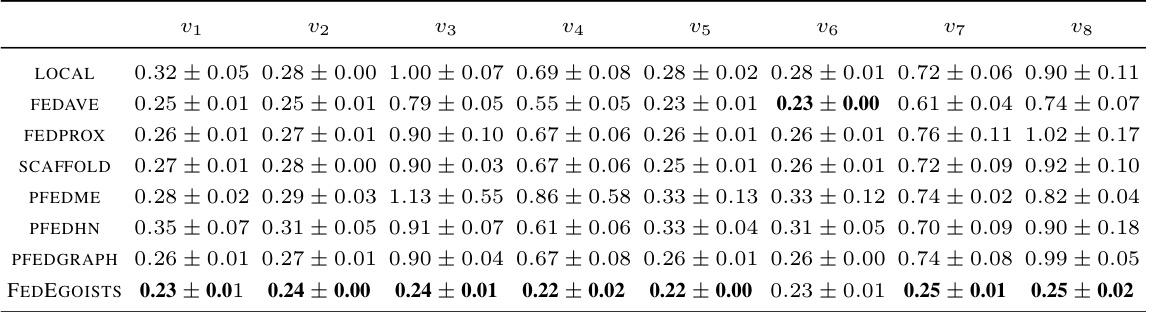

🔼 This table presents the mean test accuracy (MTA) achieved by different federated learning algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset under varying levels of competition (α). It compares the performance of FedEgoists against nine baseline methods across different data heterogeneity settings (pathological and Dirichlet distributions). The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation, allowing for the assessment of algorithm performance under different competitive scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy comparisons (MTA) under different α on CIFAR10.

In-depth insights#

FedEgoists Strategy#

The proposed “FedEgoists” strategy for cross-silo federated learning tackles the challenges of free-riders and conflicts of interest among competing organizations. It cleverly addresses these issues by forming optimal coalitions of participants who share the same interests. The strategy’s strength lies in its theoretical grounding, proving the optimality of the coalitions formed, ensuring no improvement is possible through further collaboration. This approach guarantees that only mutually beneficial collaborations are formed, mitigating free-riding while preventing contributions to competitors. The effectiveness of FedEgoists is demonstrated through extensive experiments and comparison to state-of-the-art baselines, highlighting its capability to establish efficient collaborative networks in the complex cross-silo setting.

Cross-Silo FL#

Cross-silo federated learning (FL) presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities in the realm of decentralized machine learning. Unlike cross-device FL, which involves numerous resource-constrained devices, cross-silo FL focuses on collaboration between organizations, often competitors, who each possess substantial datasets. This setting introduces complexities stemming from self-interest, where individual organizations prioritize their own gain, and competition, where organizations might be reluctant to share data beneficial to their rivals. Therefore, effective cross-silo FL strategies must incentivize collaboration while mitigating the risks of free-riding and data exploitation. Trust and robust mechanisms to ensure fairness and prevent information leakage are crucial. The optimal balance between collaborative gains and individual benefits remains a key research focus. Successfully navigating these challenges requires novel incentive schemes and careful consideration of the competitive landscape to enable the realization of cross-silo FL’s potential benefits.

Coalition Formation#

Coalition formation in federated learning (FL) addresses the challenge of efficiently leveraging the diverse data held by multiple participants. Optimal coalition structures are crucial for maximizing model accuracy and ensuring fairness among participants. The process involves carefully selecting participants to form groups that complement each other’s data while avoiding conflicts of interest and the problem of free-riders. Algorithmic approaches are key in determining the best coalition configurations. Efficient algorithms are needed to handle the computational complexity involved in considering all possible combinations. Theoretical analysis of these algorithms helps establish optimality guarantees and helps understand their efficiency. Evaluating the performance of coalition formation methods requires considering both the model’s accuracy and the fairness of the resulting collaborations. The impact of data heterogeneity on coalition formation is also a critical consideration, affecting the strategy for selecting complementary members.

Benchmark Results#

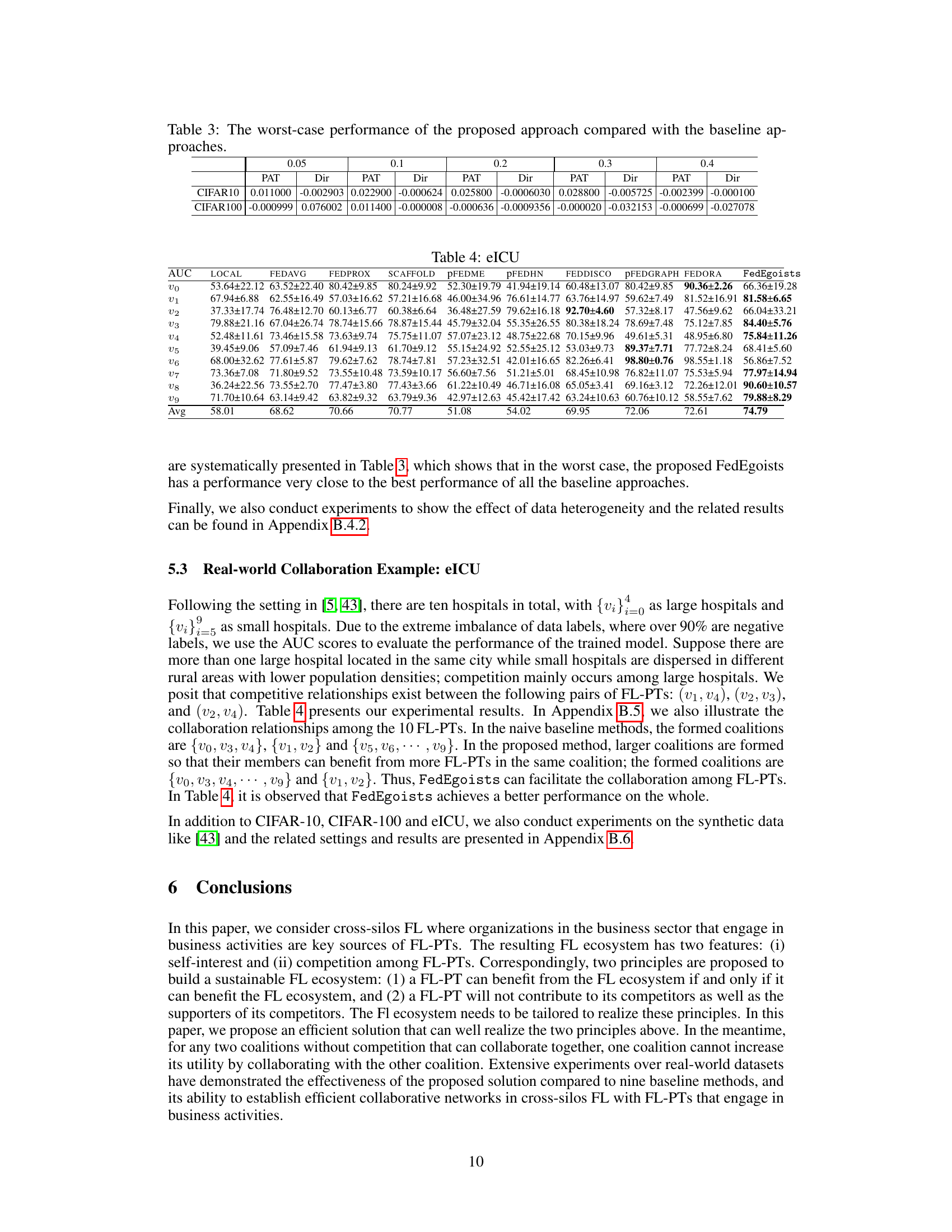

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed method, FedEgoists, against existing state-of-the-art techniques. This would involve presenting key performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, AUC, MSE) across various datasets and experimental conditions, likely showing FedEgoists’ superiority. Visualizations like tables and graphs are crucial for clear comparison. The discussion should extend beyond simple metric reporting; it needs to analyze the results in the context of data heterogeneity (e.g., effect of different data distributions) and competition intensity, highlighting FedEgoists’ robustness and advantages under various scenarios. Statistical significance testing (e.g., p-values) is necessary to ensure the observed performance differences are not due to random chance. Furthermore, the section must provide sufficient detail to enable reproducibility, including hyperparameters and training setup. A thoughtful analysis of why FedEgoists outperforms other methods is crucial, potentially linking the results to the algorithm’s design choices and theoretical underpinnings. Finally, mentioning any limitations in the benchmark setup or results and providing context for future research would enhance the section’s comprehensiveness and credibility.

Future of FL#

The future of federated learning (FL) is promising, yet faces significant challenges. Data heterogeneity remains a key hurdle, demanding innovative solutions beyond simple averaging. Privacy-preserving techniques will continue to evolve, likely incorporating advanced cryptographic methods and differential privacy enhancements. Incentivizing participation among diverse, potentially competing entities, will require sophisticated economic models and robust mechanisms. Model fairness and robustness must be addressed, accounting for biases in heterogeneous datasets and mitigating adversarial attacks. Scalability and efficiency are paramount; research into efficient communication protocols and decentralized aggregation strategies are essential. Finally, regulatory considerations concerning data governance and accountability must shape the future development and adoption of FL to ensure ethical and responsible use.

More visual insights#

More on figures

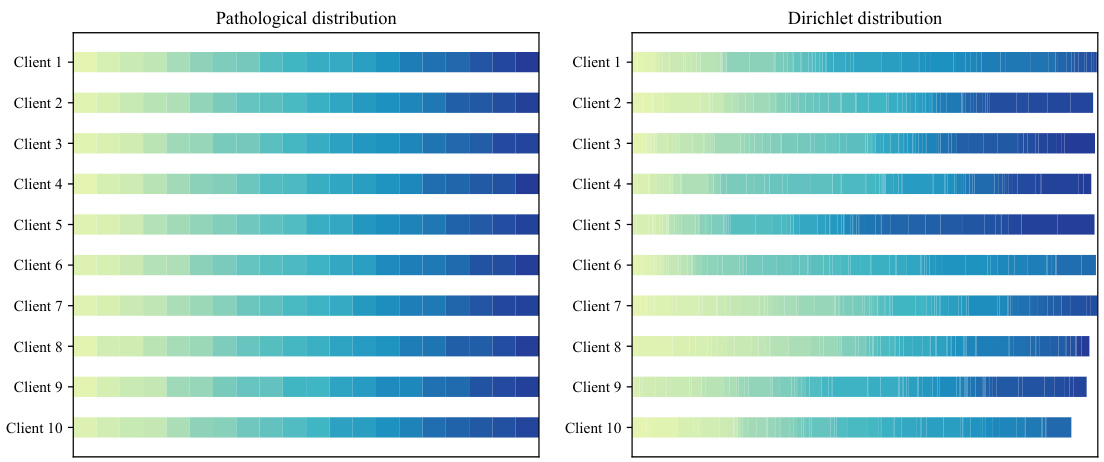

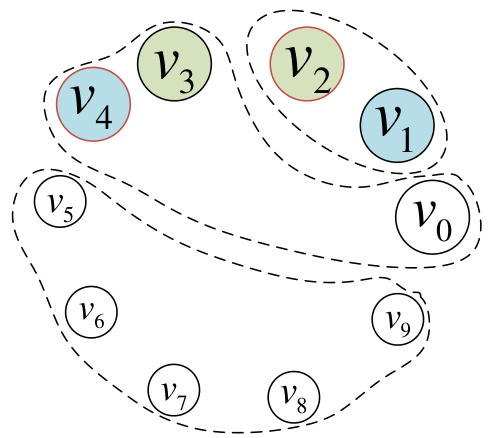

🔼 This figure illustrates Algorithm 1, which is used for forming conflict-free coalitions without free riders in a federated learning setting. Panel (a) shows an example with two strongly connected components (SCCs) from the benefit graph Gb (Sh). Panel (b) depicts the resulting set of coalitions (π) after applying Algorithm 1, showing how the algorithm merges coalitions based on benefit and competition relationships to satisfy specific principles (absence of free riders and avoiding conflicts of interest). The algorithm iteratively checks for cycles and paths in the coalition relationships, merging coalitions that meet certain conditions to improve overall utility while adhering to the principles.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of Algorithm 1.

🔼 This figure illustrates Algorithm 1, which focuses on forming conflict-free coalitions without free riders in federated learning. Panel (a) shows an example with two strongly connected components (SCCs), denoted as SCC1 and SCC2. Panel (b) depicts the resulting coalitions (π) after the algorithm has been applied to these components. Panel (b) shows how these coalitions are merged using different rules within the algorithm until the final optimal set of coalitions is obtained. The algorithm incorporates the concepts of benefit and competition graphs to optimize coalition formation while avoiding both free riders and conflicts of interest.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of Algorithm 1.

🔼 This figure illustrates Algorithm 1, which is a conflict-free coalition formation algorithm. It shows how the algorithm constructs coalitions (groups of FL-PTs) considering both the benefit graph (representing collaboration advantages) and the competing graph (representing competition relationships among FL-PTs) . The figure illustrates that Algorithm 1 partitions FL-PTs into strongly connected components (SCCs) within coalitions and it merges coalitions if merging improves utility without violating the principles of self-interest and avoiding conflict of interest. Panel (a) shows a sample of initial strongly connected components (SCCs). Panel (b) presents the set of coalitions π for the benefit and competing relationships among FL-PTs. Finally panel (c) presents the final set of coalitions after merging of Algorithm 1.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of Algorithm 1.

🔼 This figure illustrates the main motivation and results of the paper. It shows a scenario in the business sector where organizations (FL-PTs) are self-interested and compete with each other. The challenge is to form optimal collaborations among these organizations while avoiding free riders and conflicts of interest. The figure highlights how the proposed solution, FedEgoists, addresses these challenges by ensuring that each FL-PT benefits from the collaboration if and only if it benefits the overall ecosystem, and that no FL-PT will contribute to its competitors.

read the caption

Figure 1: An overview of the main motivation and results of this paper.

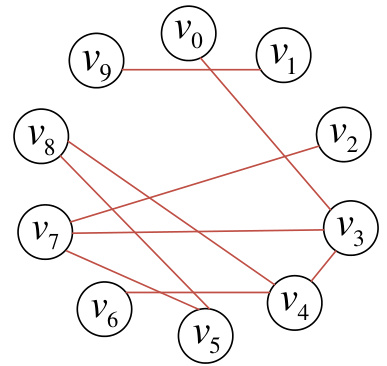

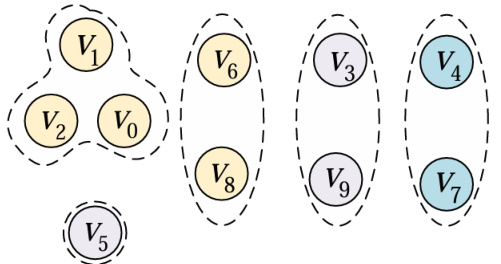

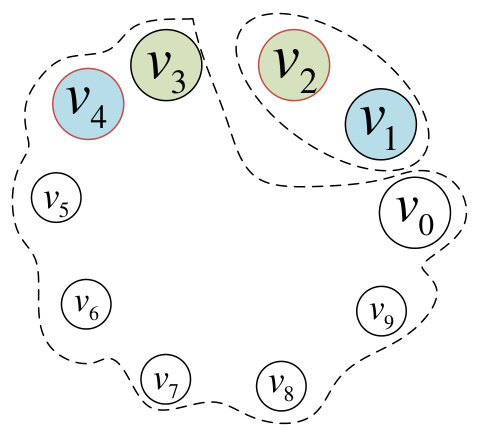

🔼 This figure visually represents different coalition formations under the CIFAR-100 dataset, comparing baseline methods with the proposed FedEgoists algorithm. It shows how FedEgoists groups the FL-PTs (represented by circles) into coalitions (represented by dashed ovals) in a way that considers both self-interest and competition among the companies. Panel (a) depicts the competition graph, while (b) and (c) illustrate coalitions formed by the baseline algorithms and FedEgoists respectively. The differences highlight how FedEgoists creates more efficient and conflict-free collaborations.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustration of Coalitions under CIFAR-100

🔼 This figure illustrates the coalition formation results under the CIFAR-100 dataset using three different approaches: (a) shows the competing graph Gc where edges represent competition between FL-PTs; (b) shows the coalitions formed by baseline algorithms; (c) shows the coalitions formed by FedEgoists, demonstrating the differences in coalition structures and the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in forming optimal collaborations.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustration of Coalitions under CIFAR-100

🔼 This figure illustrates the main motivation and results of the paper. It shows that in cross-silo federated learning, where companies are involved, there are two major issues: self-interest and competition. The goal of the paper is to develop a strategy that can form optimal coalitions among companies, avoiding free-riders and conflicts of interest while ensuring that the FL ecosystem benefits.

read the caption

Figure 1: An overview of the main motivation and results of this paper.

🔼 This figure illustrates the main idea and contribution of the paper. In cross-silo federated learning, organizations in the business sector are key sources of FL participants. This ecosystem has two features: self-interest and competition among FL participants. The figure shows how the proposed solution, FedEgoists, addresses these issues by forming optimal coalitions among FL participants, avoiding free-riders and conflict of interest. The FL manager ensures the absence of free-riders and avoids conflicts of interest by establishing optimal coalitions.

read the caption

Figure 1: An overview of the main motivation and results of this paper.

🔼 This figure illustrates the main idea and results of the paper. In cross-silo federated learning (FL) in business sectors, companies (FL-PTs) are self-interested and compete with each other. The goal is to form optimal collaborations that avoid free-riders and conflicts of interest while satisfying these constraints. The figure contrasts a naive approach which results in free riders and conflicts, with the proposed FedEgoists approach which achieves the desired optimal collaboration.

read the caption

Figure 1: An overview of the main motivation and results of this paper.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the mean test accuracy (MTA) achieved by FedEgoists and nine other baseline methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset under various levels of competition (α). Different data heterogeneity methods (pathological and Dirichlet distributions) are used. The results show the average performance across five independent trials.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy comparisons (MTA) under different α on CIFAR10.

🔼 This table presents the mean test accuracy (MTA) achieved by different federated learning algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset under varying levels of competition (α). Two different data heterogeneity settings are used: Pathological (PAT) and Dirichlet (Dir). The algorithms compared include FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, pFedMe, pFedHN, FedDisco, pFedGraph, FedOra, and the proposed FedEgoists algorithm. The results show the performance of each algorithm under different levels of competition and data heterogeneity.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy comparisons (MTA) under different α on CIFAR10.

🔼 This table presents the mean test accuracy (MTA) achieved by different federated learning (FL) approaches on the CIFAR-10 dataset under varying levels of competition (α). The results are shown for two different data heterogeneity methods: Pathological (PAT) and Dirichlet (Dir). Each row represents a different α value, and each column shows the performance of a different FL algorithm, including FedEgoists, the proposed method. The table allows for a comparison of FedEgoists against state-of-the-art baselines in terms of accuracy across different competitive scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy comparisons (MTA) under different α on CIFAR10.

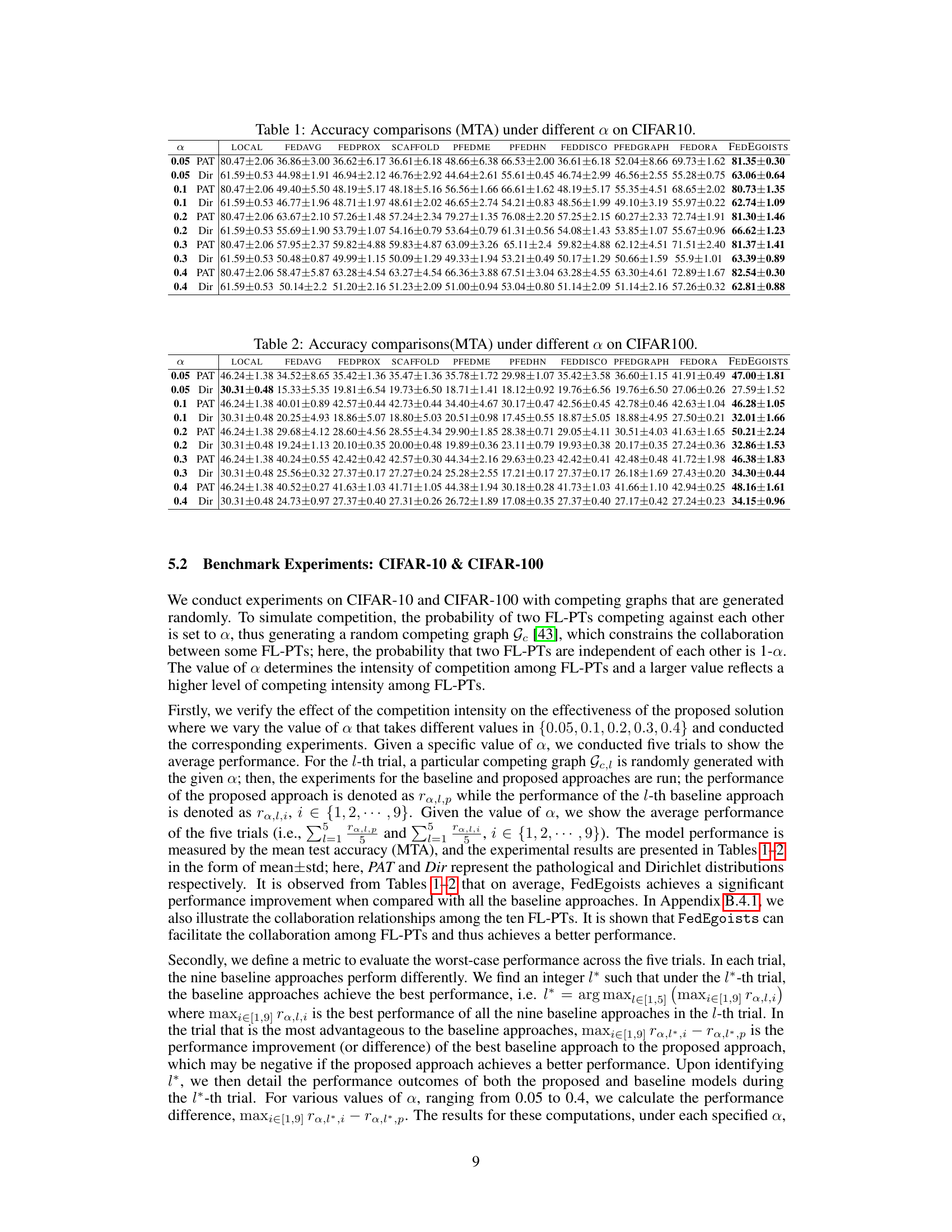

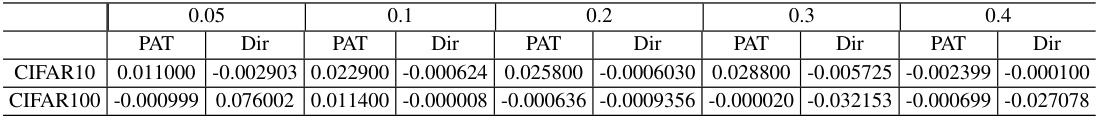

🔼 This table presents the worst-case performance comparison between the proposed FedEgoists algorithm and nine baseline methods across different competition intensities (α) and data heterogeneity settings (Pathological and Dirichlet distributions) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. For each setting, five trials were conducted, and the worst-case performance for the baseline methods (the best performance across the five trials) is compared to the performance of FedEgoists. The values show the performance difference between the best-performing baseline method and FedEgoists in the worst-case scenario.

read the caption

Table 3: The worst-case performance of the proposed approach compared with the baseline approaches.

🔼 This table presents the mean test accuracy (MTA) achieved by different federated learning algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset under varying levels of competition (α). It compares the performance of FedEgoists against nine other state-of-the-art methods, showing accuracy results across two data heterogeneity scenarios (pathological and Dirichlet distributions) and four different competition levels (α = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4). The results highlight FedEgoists’ effectiveness in achieving higher accuracy compared to baseline approaches across various settings.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy comparisons (MTA) under different α on CIFAR10.

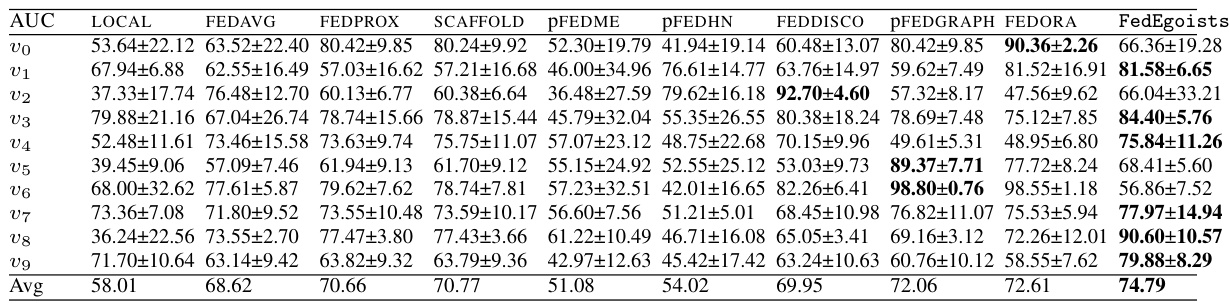

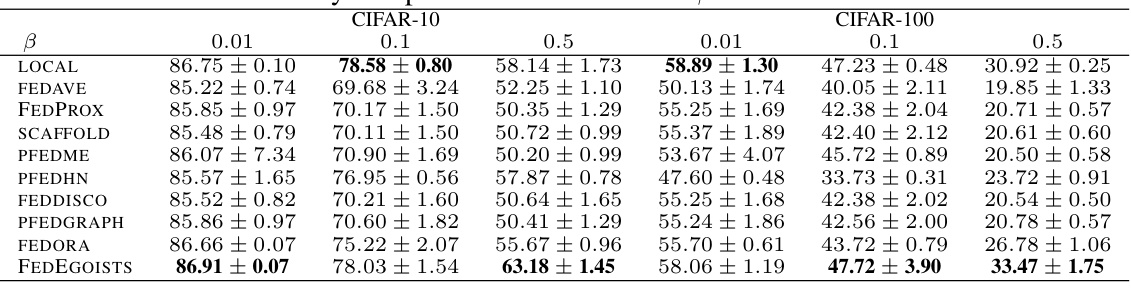

🔼 This table presents the mean test accuracy (MTA) achieved by various federated learning algorithms across different data heterogeneity levels (β values) using the Dirichlet distribution. The algorithms compared include Local, FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, pFedMe, pFedHN, FedDisco, pFedGraph, FedOra, and FedEgoists. Different β values represent varying degrees of data heterogeneity, with smaller β values indicating higher heterogeneity. The results show the average accuracy and standard deviation across multiple trials for each algorithm and heterogeneity level. This allows for a comparison of algorithm performance under different conditions and data distributions.

read the caption

Table 5: Accuracy comparisons under different β of Dirichlet distribution

🔼 This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) results for different federated learning algorithms on synthetic data with a weakly non-IID setting and fixed competing graphs. The weakly non-IID setting introduces a skew in the amount of data available to each participating FL-PT (some have 2000 samples, others have only 100), and the competing graph defines competition relationships between FL-PTs. The table shows the MSE for each algorithm across eight FL-PTs (v1 to v8). Lower MSE values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 6: Experimental results (MSE) with synthetic data under fixed competing graphs: The weakly non-IID setting

🔼 This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) results of different federated learning algorithms on synthetic data with a weakly non-IID setting and fixed competing graphs. The results are shown for various algorithms including LOCAL, FEDAVE, FEDPROX, SCAFFOLD, PFEDME, PFEDHN, PFEDGRAPH and FEDEGOISTS. The ‘weakly non-IID’ designation indicates that there’s a significant difference in the sample quantities across different federated learning participants (FL-PTs), creating a data imbalance. Each algorithm’s performance is evaluated across eight different FL-PTs (v1 through v8).

read the caption

Table 6: Experimental results (MSE) with synthetic data under fixed competing graphs: The weakly non-IID setting

Full paper#