↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) produce powerful but opaque text embeddings. This creates challenges in fields like neuroscience, where model interpretability is crucial for understanding brain activity. Existing interpretable methods often sacrifice accuracy for interpretability. This paper aims to bridge this gap.

The paper proposes a new method called “question-answering embeddings” (QA-Emb). QA-Emb generates embeddings by prompting an LLM with a series of yes/no questions about the input text. The answer to each question forms a feature in the embedding. The researchers demonstrate that QA-Emb outperforms existing methods in predicting fMRI responses to language stimuli, while maintaining high interpretability. They also show that QA-Emb can be efficiently approximated by a distilled model, making it more computationally feasible.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it presents QA-Emb, a novel method for creating interpretable text embeddings. This addresses a critical need in fields like neuroscience and social sciences where understanding the model’s decision-making process is paramount. It offers a flexible and efficient way to generate interpretable models, surpassing existing methods in accuracy while requiring fewer resources. Further research can build on QA-Emb to improve interpretability across various NLP tasks and deepen our understanding of complex brain representations.

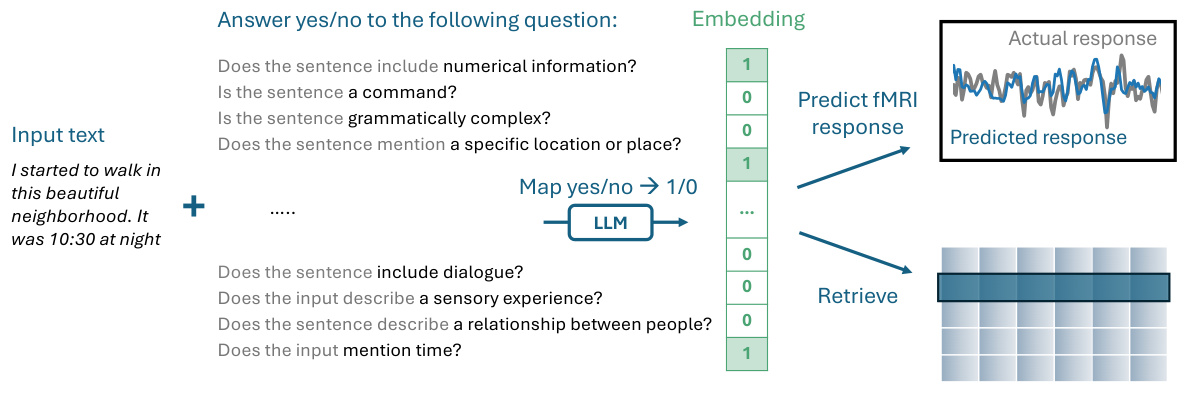

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the QA-Emb method. An input text is fed into a Large Language Model (LLM). The LLM is prompted with a series of yes/no questions about the input text. The answers (1 for yes, 0 for no) to these questions form the embedding vector. This embedding vector is then used for downstream tasks such as predicting fMRI responses to the text or for information retrieval.

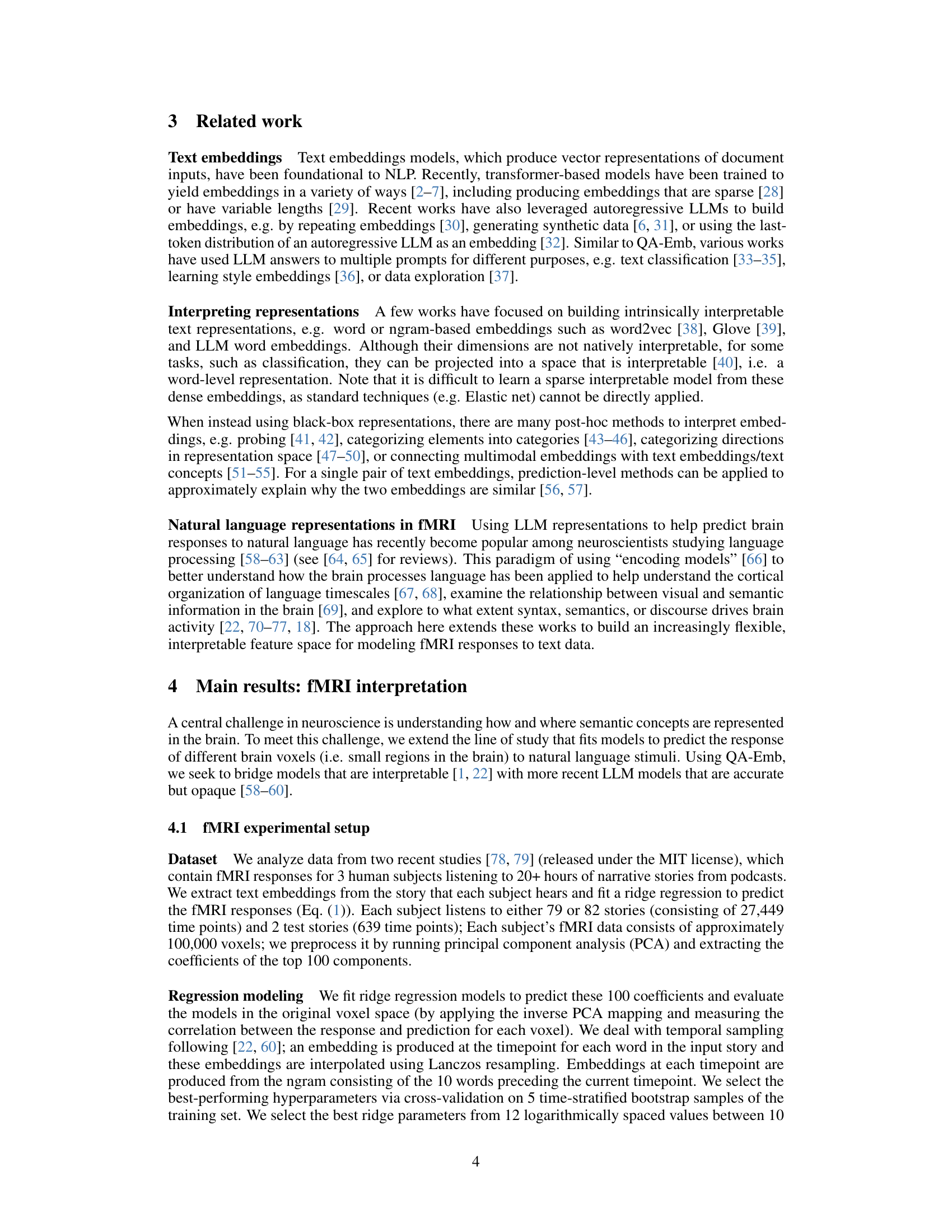

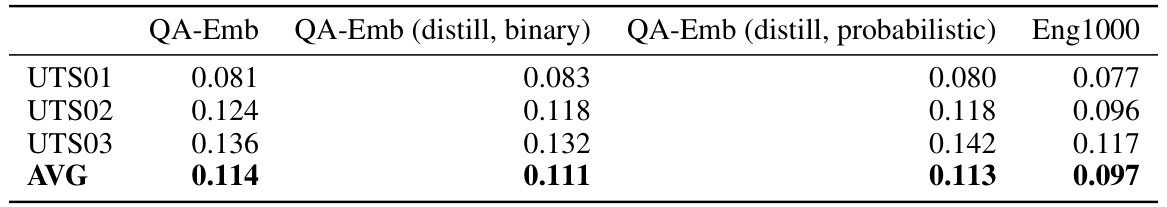

This table compares the mean test correlation achieved by the original QA-Emb method (using multiple LLM calls) against two distilled versions: one producing binary embeddings and another producing probabilistic embeddings. It also includes the performance of the Eng1000 baseline for comparison. The results show that distilling the QA-Emb model does not significantly reduce its predictive performance on the fMRI dataset.

In-depth insights#

LLM-based Embeddings#

LLM-based embeddings represent a significant advancement in natural language processing, leveraging the power of large language models (LLMs) to generate high-dimensional vector representations of text. These embeddings capture semantic nuances and contextual information far beyond traditional methods like bag-of-words. However, this power comes at the cost of interpretability; LLMs are often considered “black boxes.” The challenge lies in bridging the gap between the rich semantic information encoded in LLM embeddings and the need for human-understandable representations. Researchers are actively exploring techniques to enhance the interpretability of LLM embeddings, such as through probing classifiers, attention mechanisms analysis, or generating embeddings based on LLM responses to specific, interpretable prompts. Successfully achieving interpretable LLM embeddings is crucial for deploying them in high-stakes applications such as healthcare or finance, where trust and transparency are paramount. Future research directions include developing more efficient methods for generating and interpreting LLM embeddings, as well as exploring their potential in various other scientific domains.

Interpretable fMRI#

Interpretable fMRI aims to bridge the gap between the accuracy of complex models like LLMs and the need for transparent, understandable analyses in neuroscience. The core challenge lies in making the ‘black box’ nature of these models interpretable, so that researchers can understand how brain activity relates to language processing. This paper tackles this challenge by introducing QA-Emb, a novel method that generates interpretable embeddings by querying LLMs. QA-Emb achieves significant improvements over existing interpretable baselines, even outperforming some opaque methods in fMRI prediction accuracy. The key to interpretability is the use of natural language questions, thus transforming complex model outputs into human-understandable feature spaces. The approach’s effectiveness is shown by its ability to predict fMRI voxel responses to language stimuli, offering valuable insights into semantic brain representations. While computationally expensive initially, the method’s computational cost is reduced by model distillation, demonstrating its practical applicability. Despite limitations in LLM accuracy and computational cost, the approach offers a significant advancement for building flexible and interpretable feature spaces to study the brain.

QA-Emb: Method#

The proposed QA-Emb method offers a novel approach to generating interpretable text embeddings by leveraging LLMs. Instead of relying on complex, opaque model architectures, QA-Emb frames the problem as question selection. This fundamentally alters the learning process; instead of training model weights, it focuses on identifying a set of yes/no questions whose answers, when concatenated, form the embedding. This approach provides intrinsic interpretability because each embedding dimension directly corresponds to a human-understandable question, offering insights into the model’s internal representations. The efficacy of this method hinges on carefully selecting the questions, a task potentially optimized via iterative LLM prompting or guided by domain expertise, as explored in the fMRI prediction task. This innovative approach offers a powerful alternative to traditional black-box embeddings, particularly valuable in scientific domains demanding transparent models. It also raises questions regarding the potential biases introduced by question selection and the effectiveness of LLMs in consistently answering nuanced yes/no questions.

Computational Limits#

A research paper’s section on “Computational Limits” would explore the boundaries of the proposed method or model. This might involve discussing the scaling of computational cost with respect to data size or model complexity. For example, a computationally intensive method might be impractical for very large datasets or complex models. The analysis should also address the trade-off between computational cost and performance. A more sophisticated model may achieve better accuracy, but the increased computational requirements may outweigh the benefit, especially if resources are limited. Furthermore, the discussion should address the availability of computational resources. The paper should indicate whether specialized hardware or software is needed, and if so, whether this is readily available or prohibitively expensive. It also needs to examine the practical implications of computational limits, suggesting alternative strategies or approximations for scenarios where the full method becomes too computationally expensive. Overall, this section needs to present a balanced perspective: highlighting both the capabilities and limitations, and offering solutions for mitigating computational challenges.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore refining question selection methods for QA-Emb. Instead of heuristic approaches, directly optimizing the set of questions for specific downstream tasks would significantly improve performance. This might involve advanced discrete optimization techniques or iterative methods where LLMs suggest new questions based on model performance. Investigating the generalizability of QA-Emb across diverse datasets and tasks beyond fMRI prediction and simple NLP tasks is crucial. Evaluating the impact of different LLMs and the sensitivity of QA-Emb to LLM inaccuracies needs further exploration. A comprehensive analysis comparing QA-Emb’s computational cost and accuracy trade-offs against existing methods could also offer valuable insights. Further work should assess the extent to which the interpretability offered by QA-Emb enhances trust and reliability in high-stakes applications, such as medicine. Finally, exploring how QA-Emb can be integrated within more complex NLP architectures and workflows is important for real-world impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

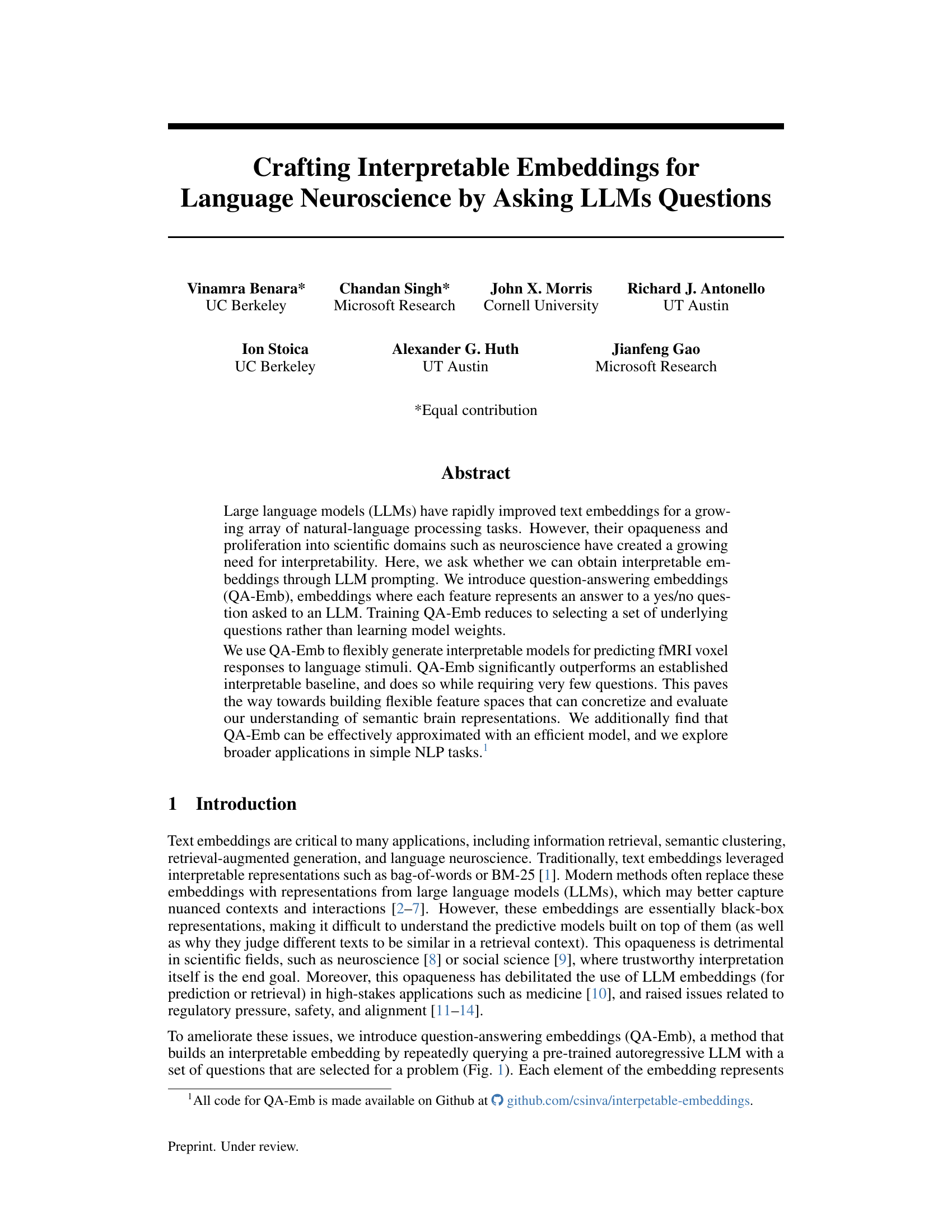

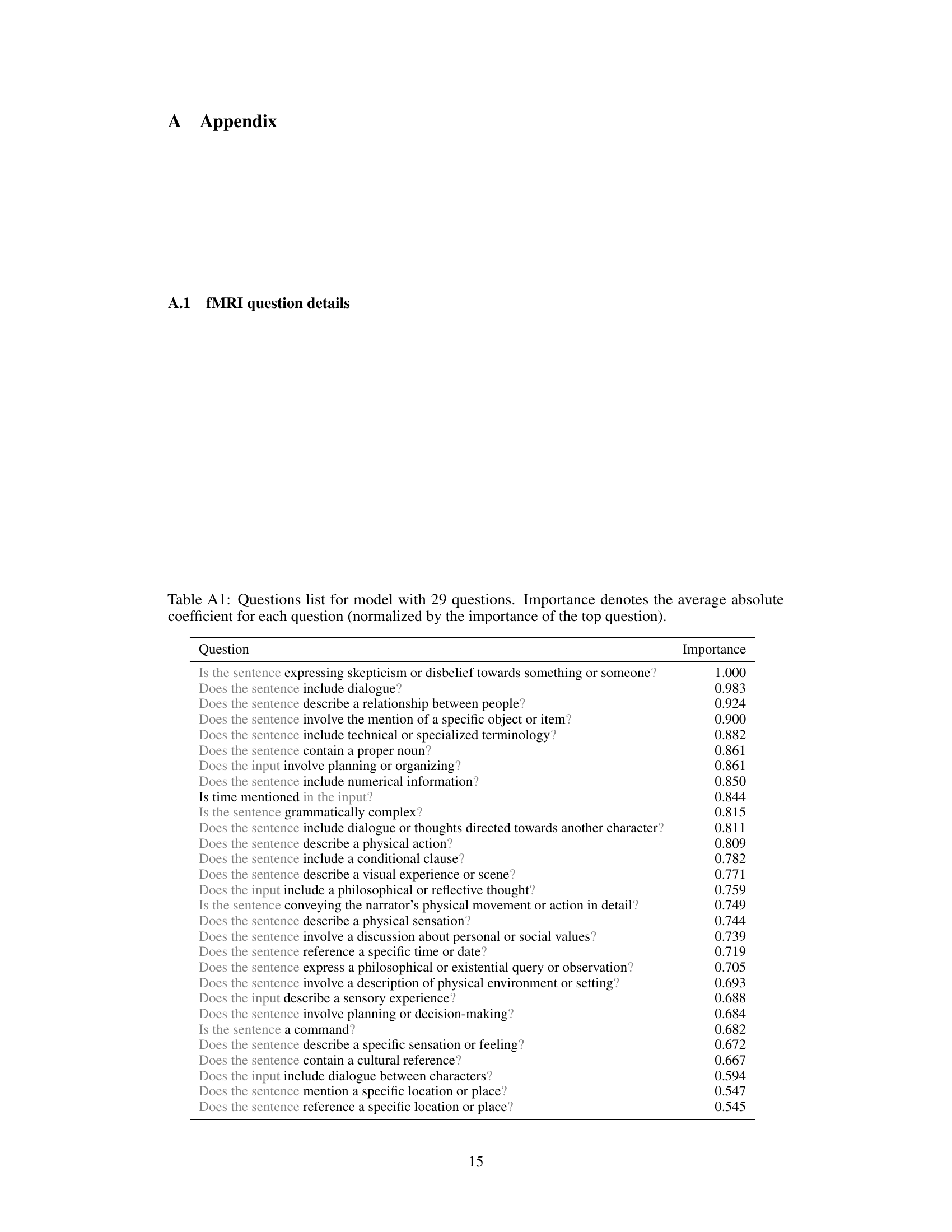

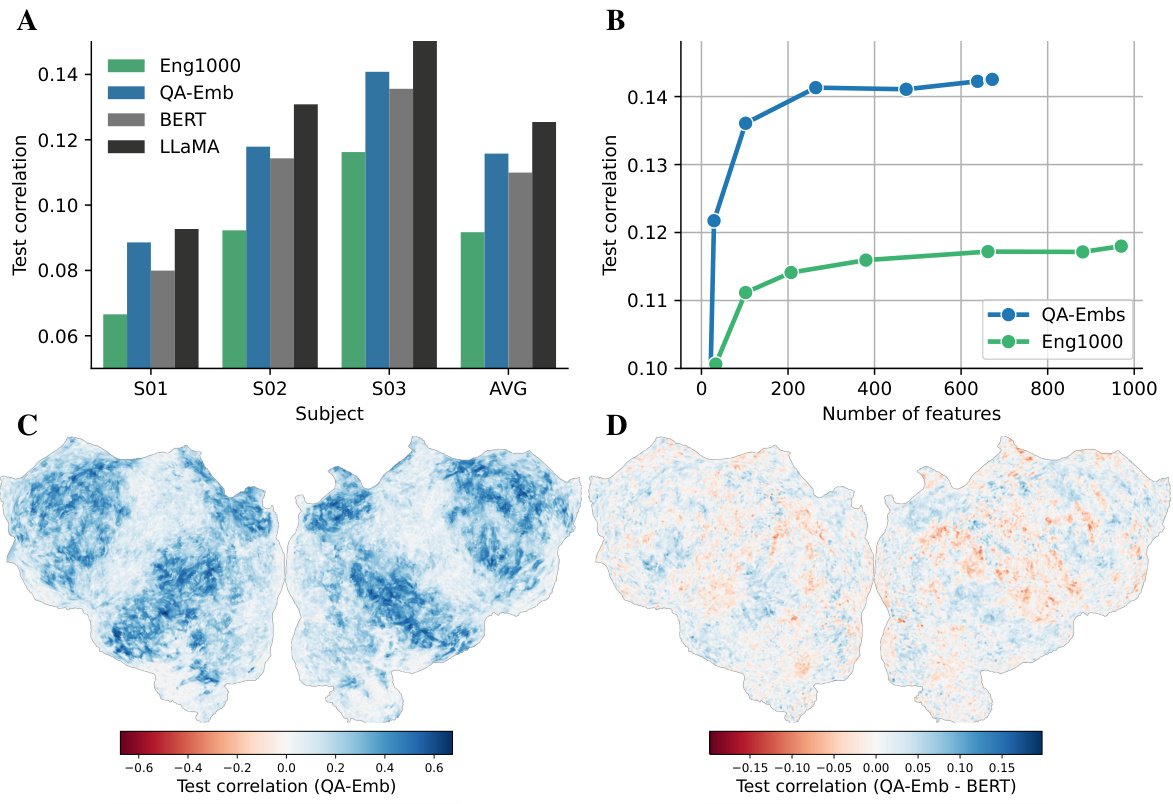

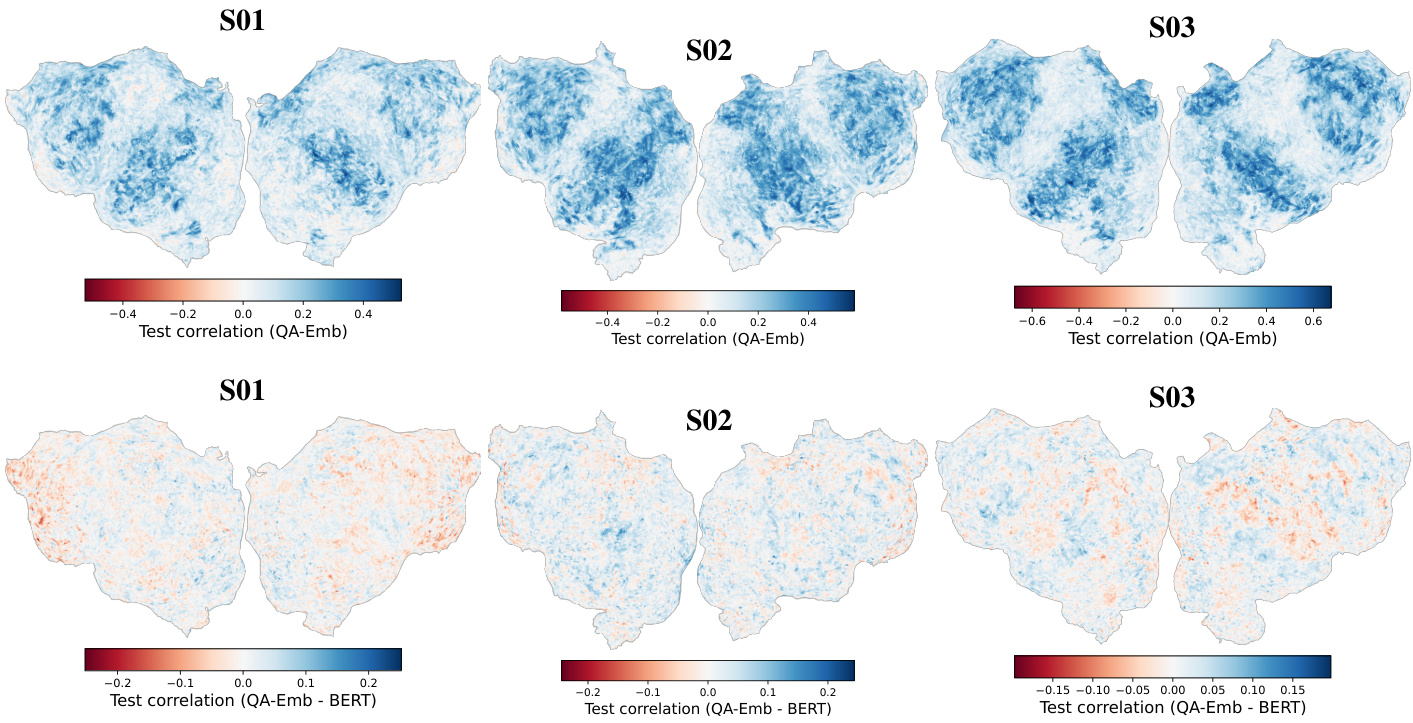

This figure presents the results of comparing QA-Emb’s predictive performance against three baselines: Eng1000, BERT, and LLaMA. Panel A shows a bar chart comparing the test correlation for each method across three subjects and on average. Panel B shows a line graph illustrating how QA-Emb’s performance improves as more questions are added to the model (i.e., more features). Panel C displays a heatmap visualizing test correlation per voxel for QA-Emb in subject S03, showcasing its ability to predict fMRI responses at the voxel level. Finally, panel D presents another heatmap comparing the differences in test correlation between QA-Emb and BERT in subject S03, highlighting the brain regions where QA-Emb shows improved prediction compared to BERT.

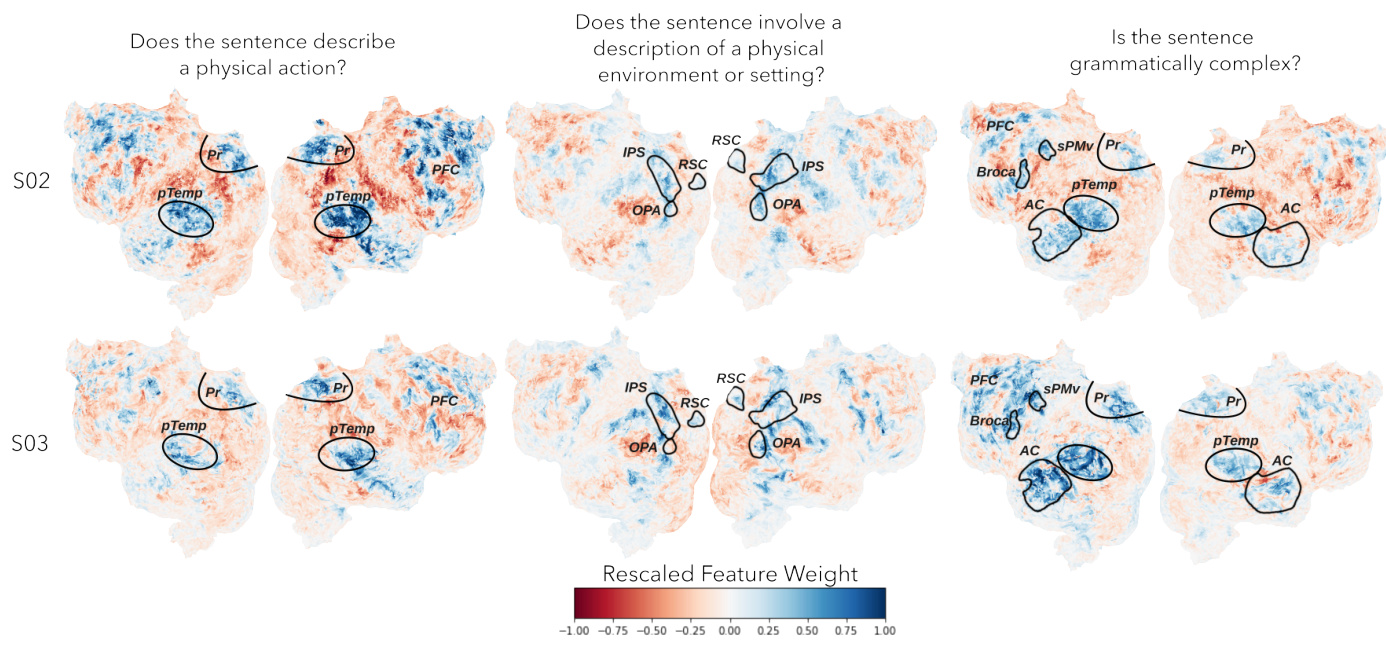

This figure visualizes the learned regression weights for three example questions from the QA-Emb model across two subjects (S02 and S03). The weights are displayed as flatmaps, showing the distribution of weights across the brain’s cortical surface. Each question’s weights highlight specific brain regions associated with the semantic content of the question, demonstrating consistent activation patterns across subjects. For instance, the question about physical environment activates known place-selective areas like the retrosplenial cortex and occipital place area.

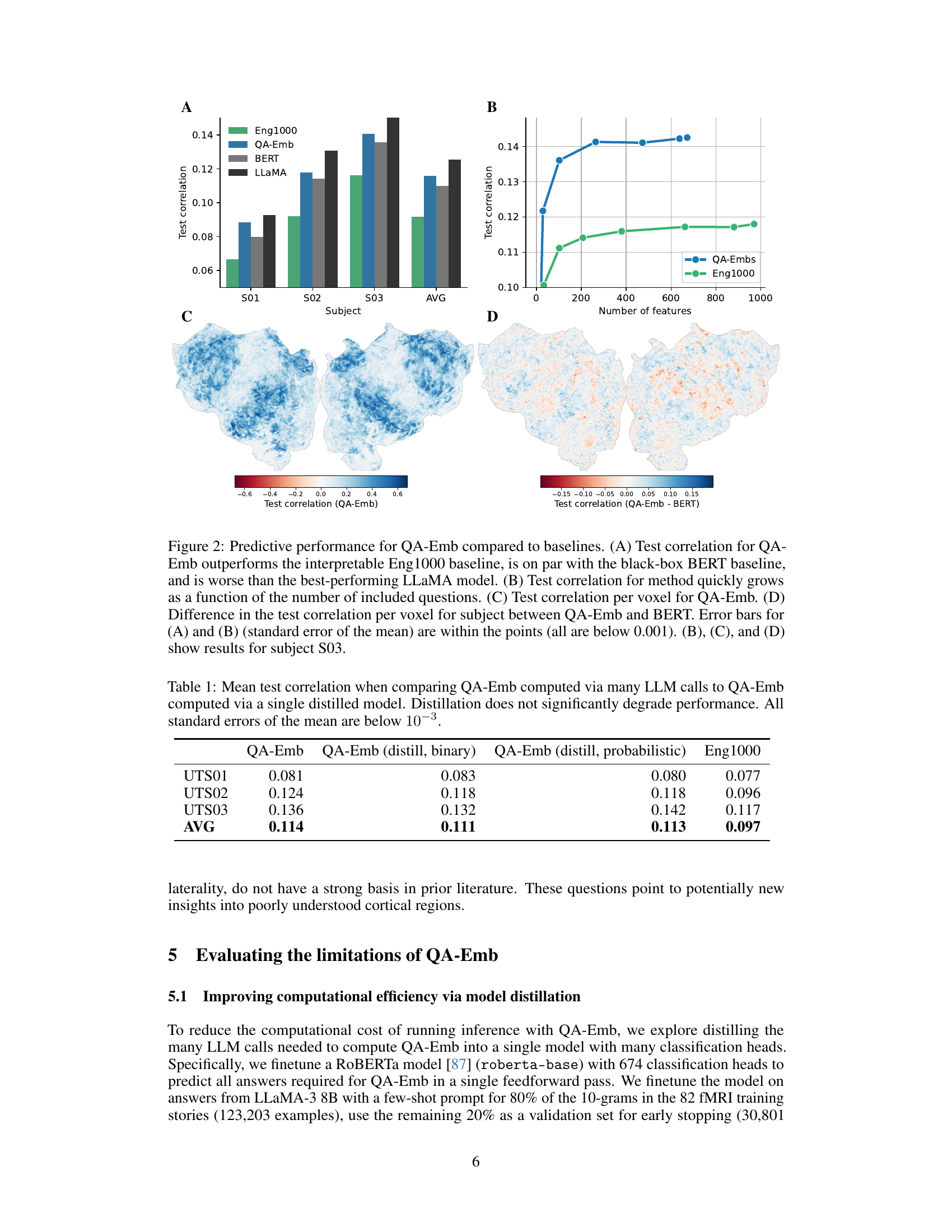

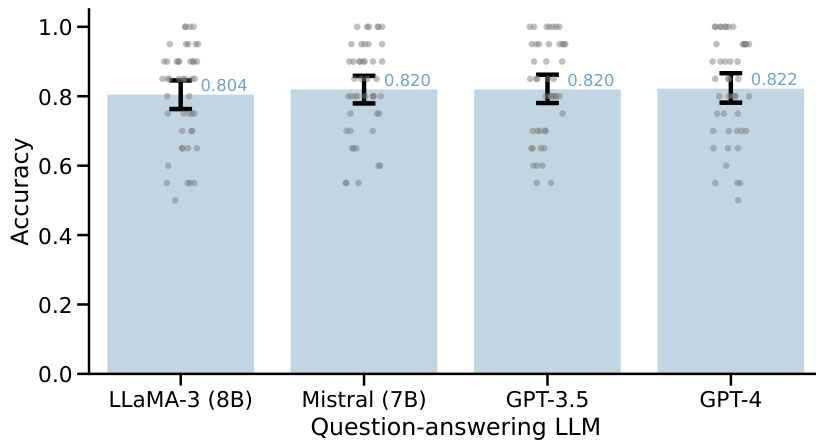

This figure demonstrates the performance of four different Large Language Models (LLMs) in answering yes/no questions from the D3 collection of binary classification datasets. Each data point represents the accuracy of a single LLM on a specific dataset, and the error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The figure visually compares the overall accuracy of each LLM across the various datasets. It helps to assess the reliability and capability of these LLMs in answering a diverse range of yes/no questions.

This figure compares the performance of QA-Emb against several baselines for fMRI response prediction. Panel A shows that QA-Emb outperforms the interpretable Eng1000 model and performs similarly to BERT, while slightly underperforming the best-performing LLaMA model. Panel B illustrates the improvement in test correlation with an increasing number of questions used for QA-Emb. Panels C and D visualize the performance and difference in performance against BERT for a particular subject across different brain voxels.

More on tables

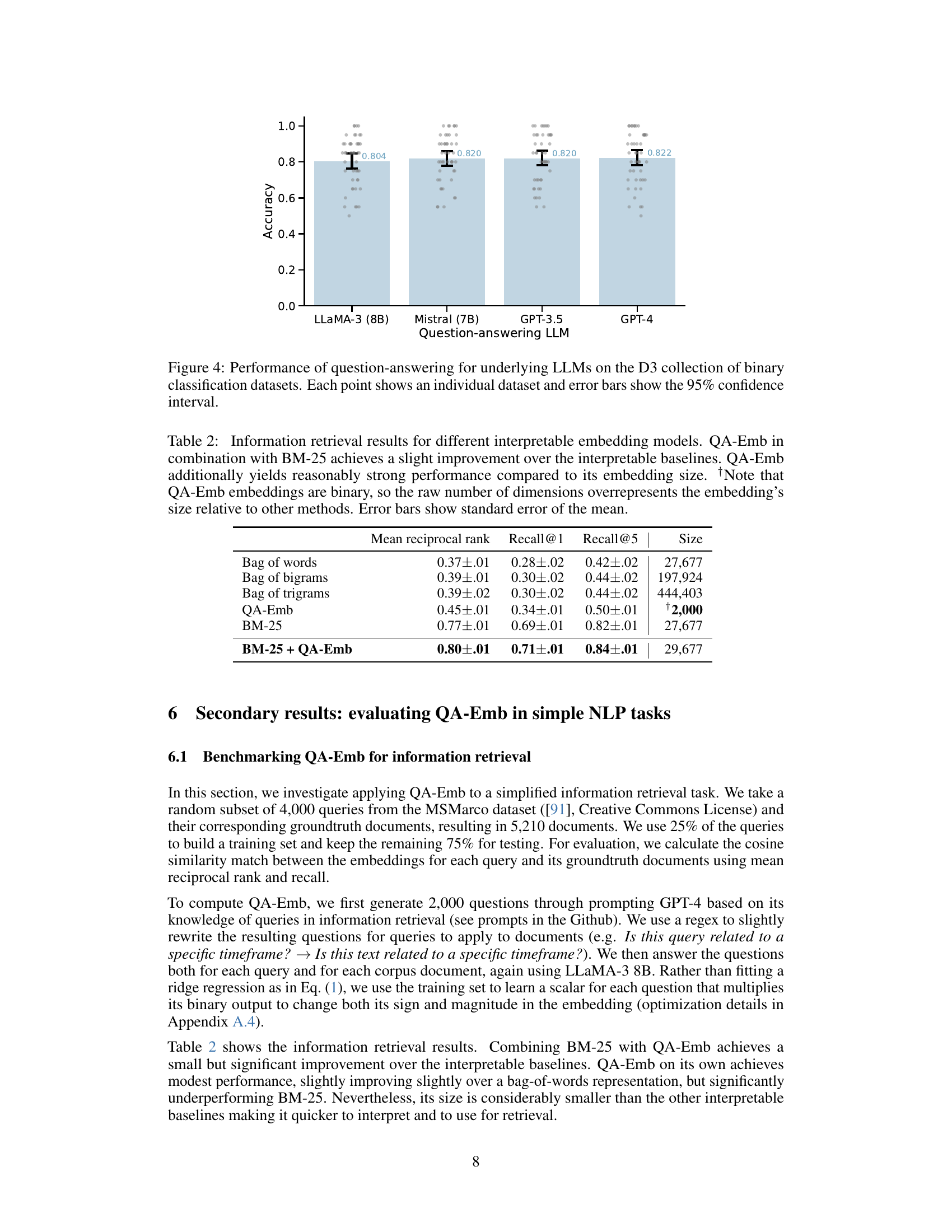

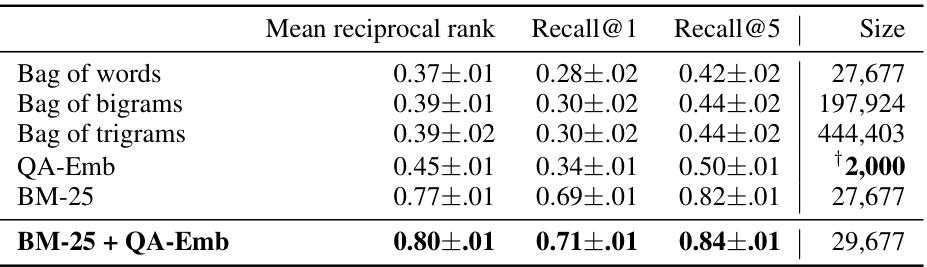

This table presents the performance comparison of several interpretable embedding models in an information retrieval task. The models include bag-of-words (unigrams, bigrams, and trigrams), QA-Emb, and BM-25. The performance metrics are mean reciprocal rank, recall@1, and recall@5. The table also shows the size (dimensionality) of each embedding. QA-Emb, when combined with BM-25, shows a slight improvement over the baseline models, while demonstrating relatively high performance considering its relatively low dimensionality.

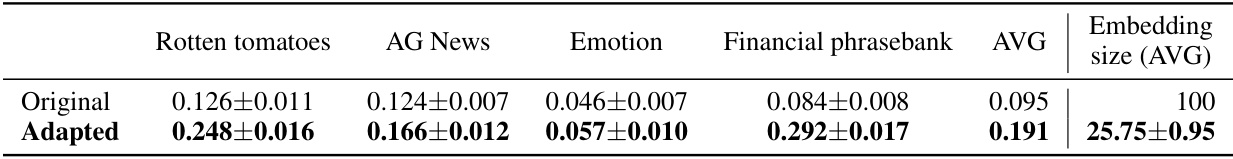

This table presents the clustering scores for four different text classification datasets (Rotten tomatoes, AG News, Emotion, Financial phrasebank) before and after a zero-shot adaptation using QA-Emb. The ‘Original’ row shows the clustering performance using embeddings generated with general questions, while the ‘Adapted’ row shows the performance after adapting the questions to be dataset-specific via LLM prompting. Higher scores indicate better clustering performance (i.e., data points within the same class are closer together in the embedding space, and data points from different classes are further apart). The average embedding size is also shown for both the original and adapted embeddings. The zero-shot adaptation significantly improves the clustering scores across all datasets, demonstrating the flexibility and adaptability of QA-Emb.

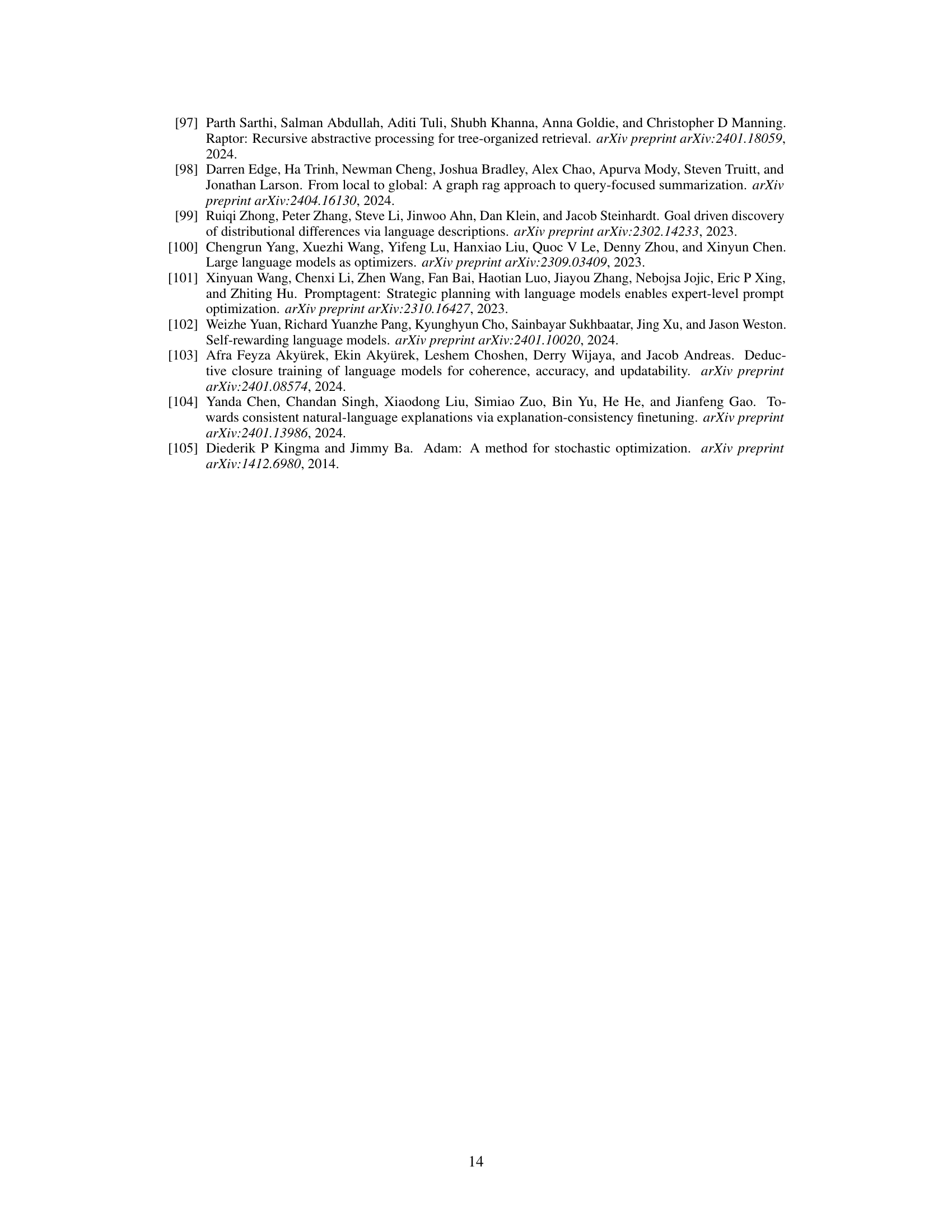

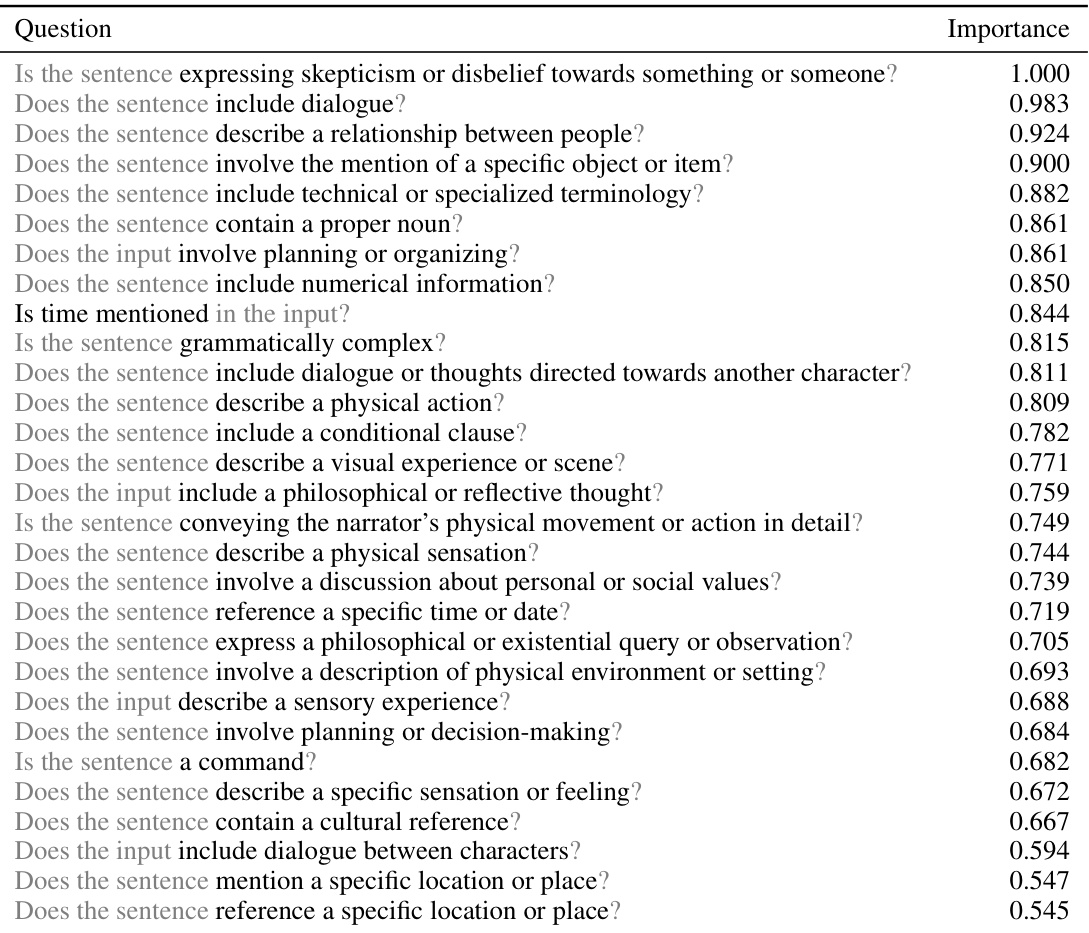

This table lists 29 yes/no questions used in the QA-Emb model, along with their importance scores. The importance score for each question represents its average absolute coefficient in the final model, normalized by the highest coefficient. This indicates the relative contribution of each question in predicting fMRI responses. A higher score suggests greater importance in the model’s predictions.

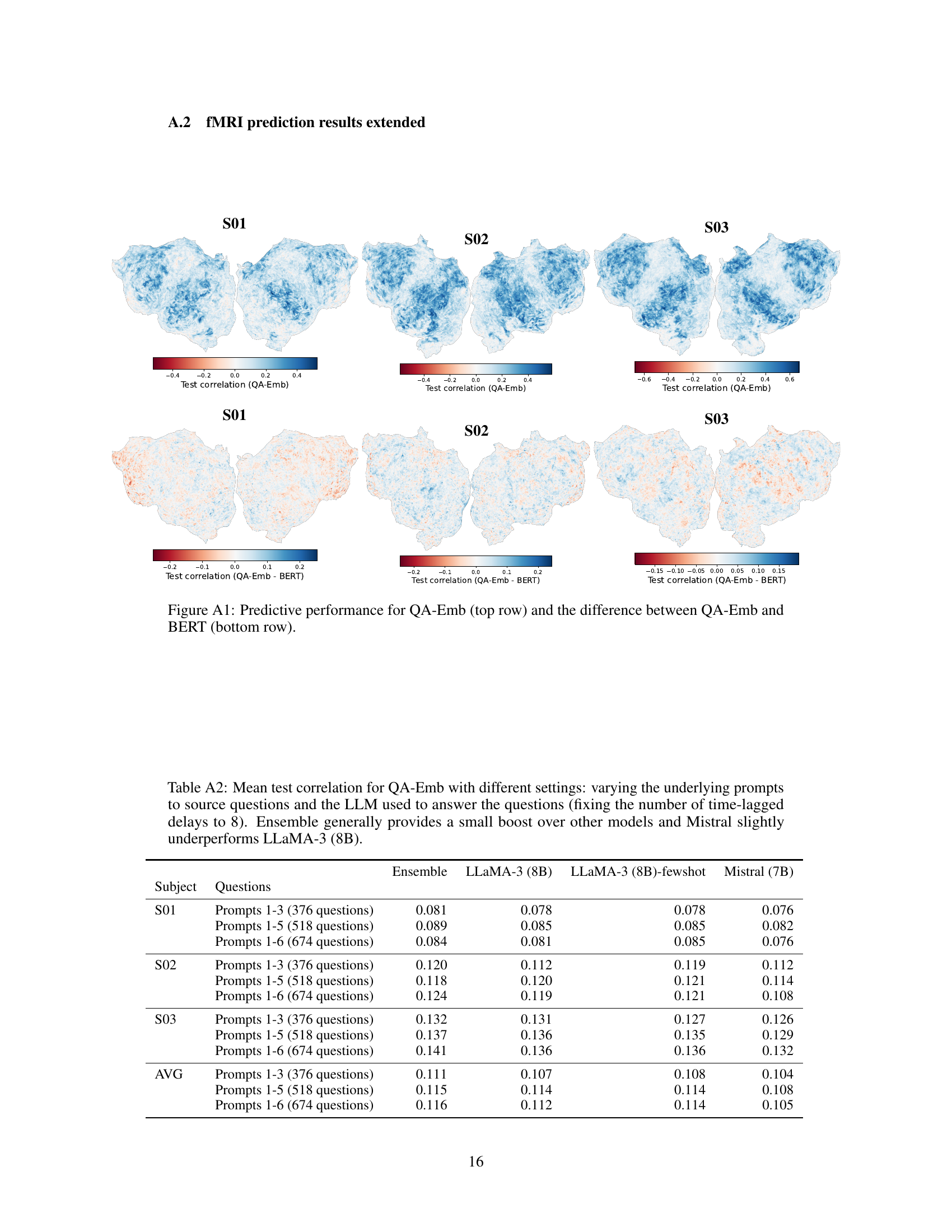

This table presents the mean test correlation achieved by the QA-Emb model under different experimental conditions. Specifically, it shows how the performance varies depending on the set of prompts used to generate questions (Prompts 1-3, 1-5, 1-6) and the large language model (LLM) employed to answer these questions (Ensemble, LLaMA-3 (8B), LLaMA-3 (8B)-fewshot, Mistral (7B)). The number of time-lagged delays was kept constant at 8 for all experiments. The results indicate that using an ensemble of LLMs generally leads to slightly better performance, while the Mistral model shows slightly lower accuracy than LLaMA-3 (8B).

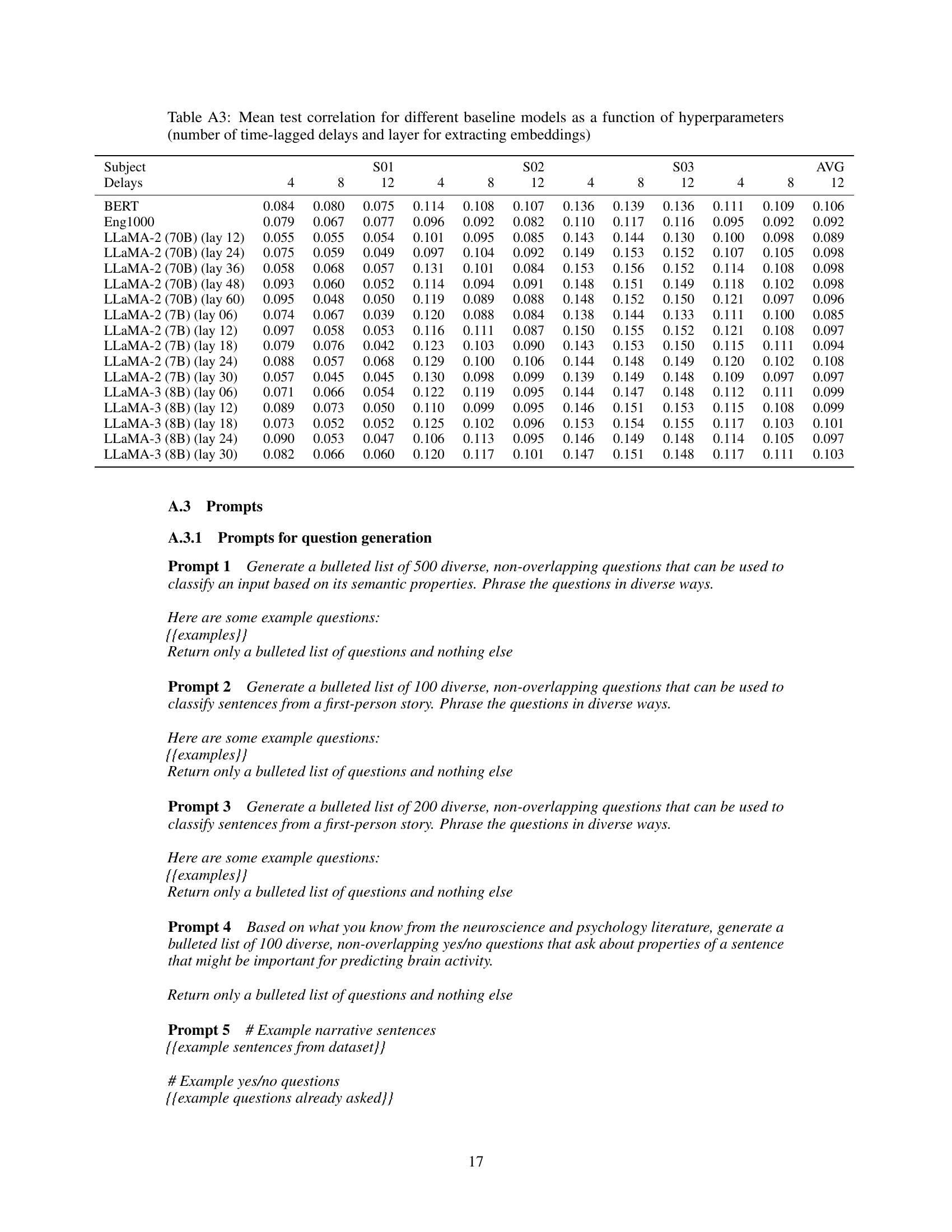

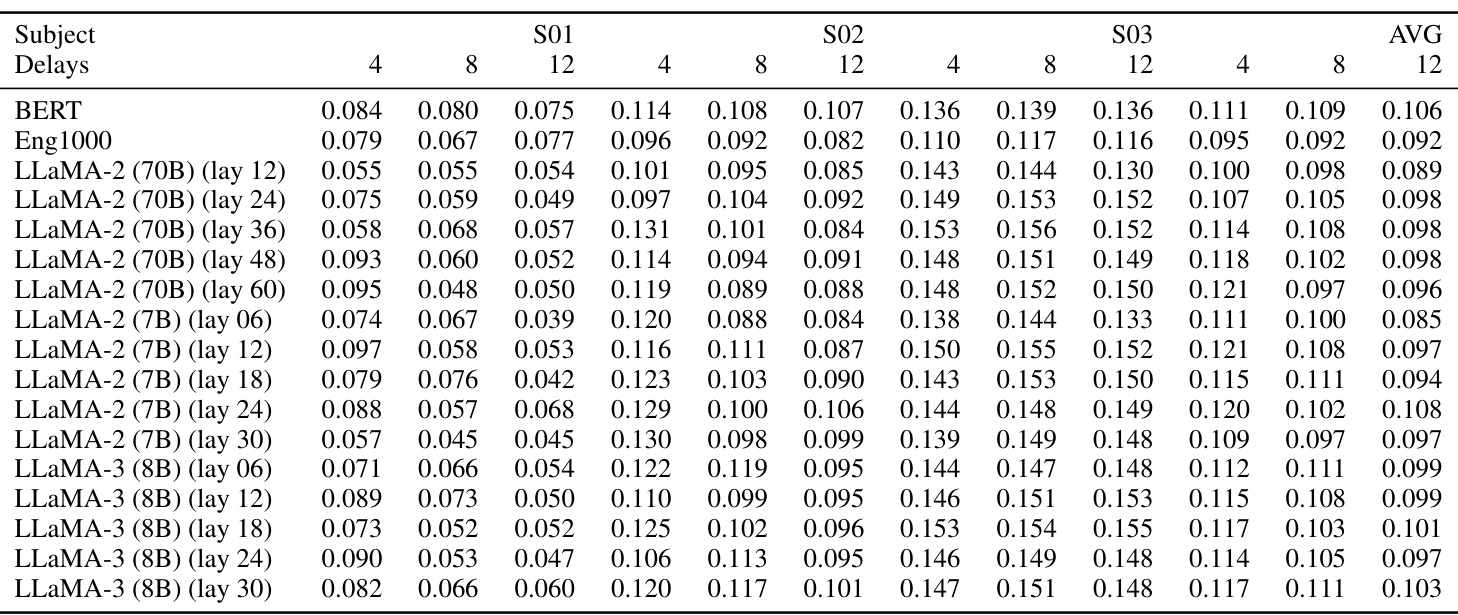

This table presents the mean test correlation results for various baseline models (BERT, Eng1000, and different LLaMA models) in predicting fMRI responses. It explores the impact of two hyperparameters on prediction accuracy: the number of time-lagged delays included as features and the layer from which embeddings are extracted from the LLMs. The results are shown separately for each subject (S01, S02, S03) and on average across subjects.

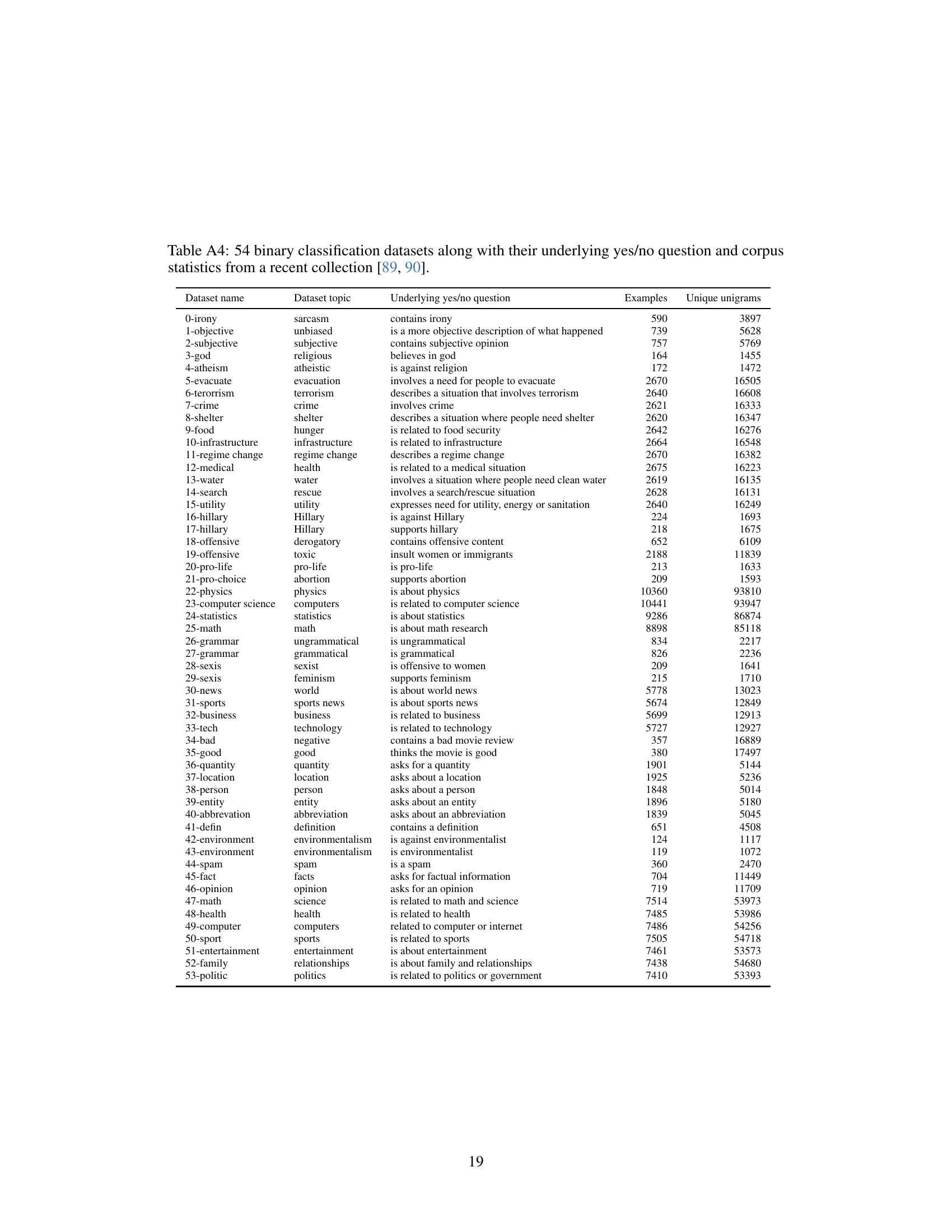

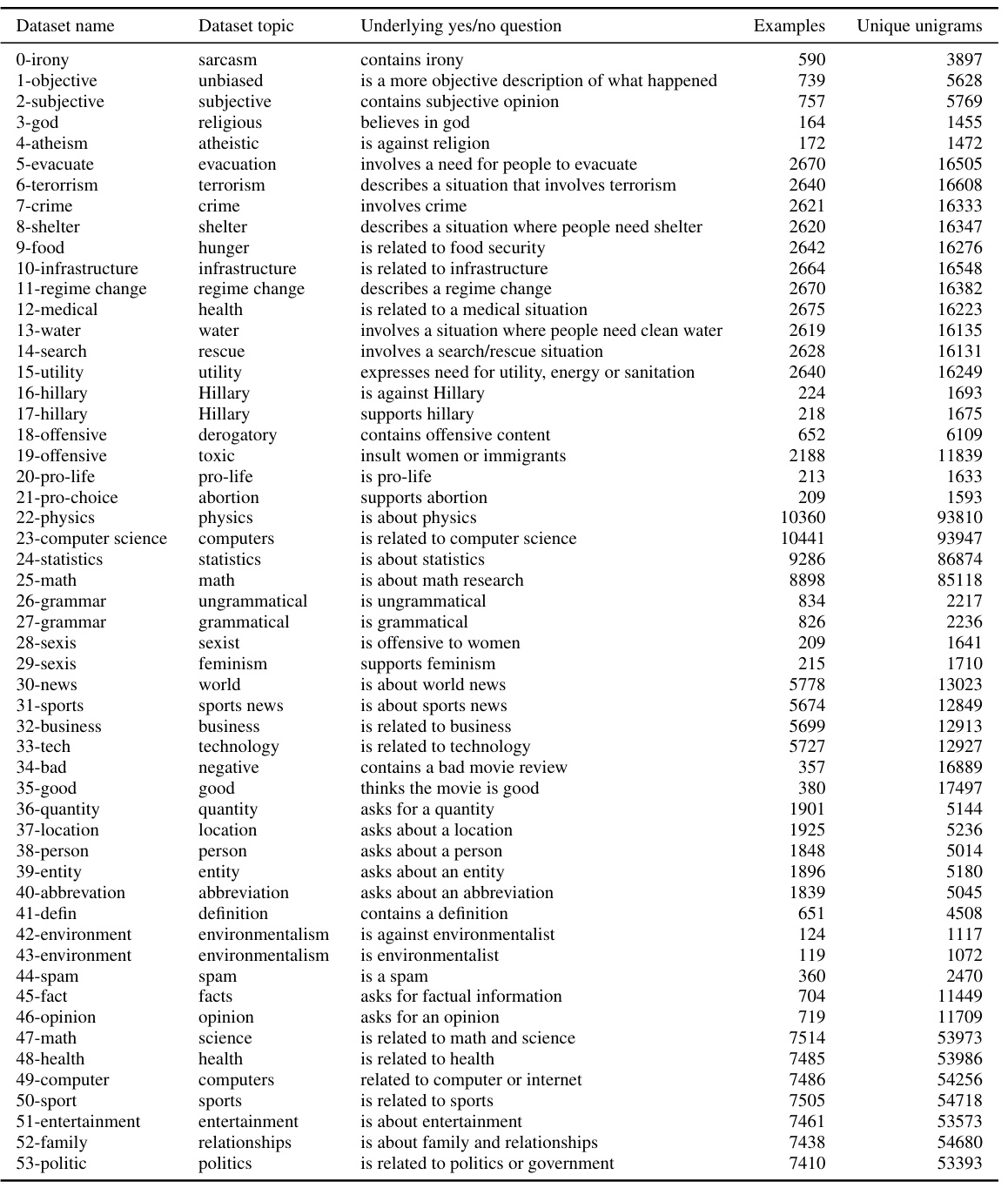

This table lists 54 binary classification datasets used to evaluate the question-answering accuracy of LLMs. For each dataset, it provides the dataset’s name and topic, the underlying yes/no question used for classification, and corpus statistics including the number of examples and unique unigrams.

Full paper#