↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly used for automating complex tasks, but their effectiveness is often hindered by limitations in interacting with software applications. Existing methods, such as directly using command-line interfaces or existing software applications, often prove inefficient and error-prone, highlighting the need for specialized interfaces tailored to the capabilities and limitations of LLMs. This research addresses these issues by introducing a novel approach.

The research introduces SWE-agent, a system that uses a custom-designed Agent-Computer Interface (ACI) to significantly improve the performance of LLM agents in software engineering tasks. The ACI simplifies interactions, provides helpful feedback, and includes error prevention mechanisms (guardrails), enhancing the agent’s ability to effectively search, edit, and execute code. SWE-agent achieves state-of-the-art results on two established benchmarks, demonstrating the practical value of the ACI approach. The study also provides valuable design principles for creating effective ACIs for LLM agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers working on code generation and agent-based systems. It introduces a novel concept—the Agent-Computer Interface (ACI)—demonstrating its significant impact on language model (LM) agent performance. The open-sourced codebase and detailed methodology greatly enhance reproducibility and provide a strong foundation for future research into improved human-AI collaboration. Furthermore, the work explores new interactive prompting techniques for complex programming tasks, a burgeoning area of interest in the field.

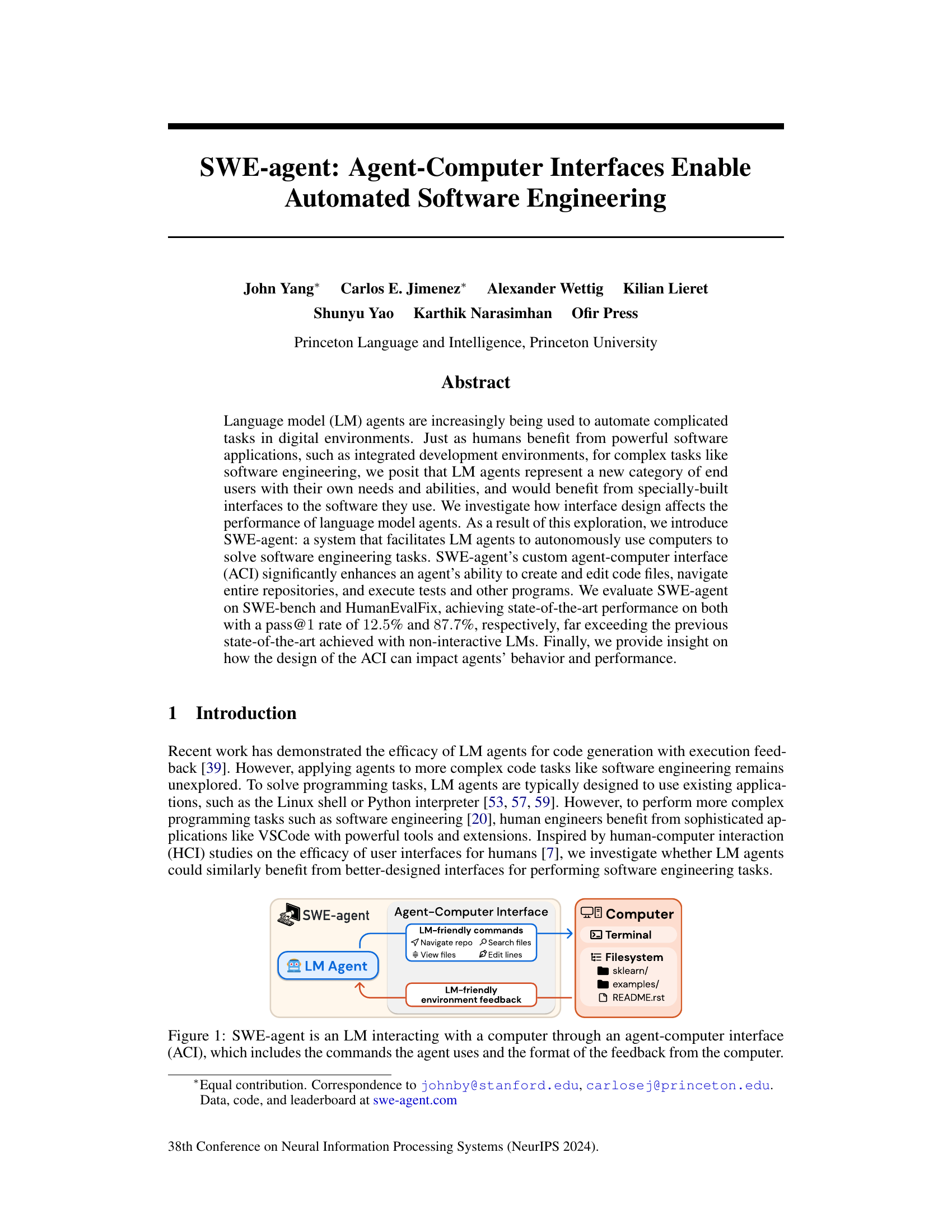

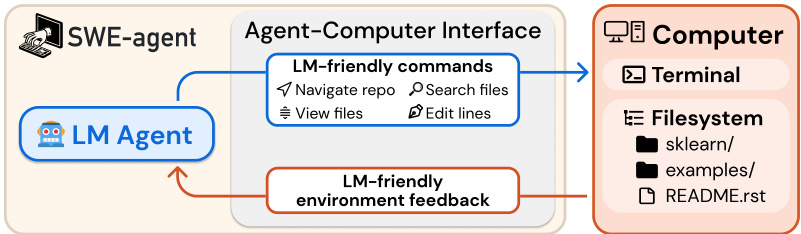

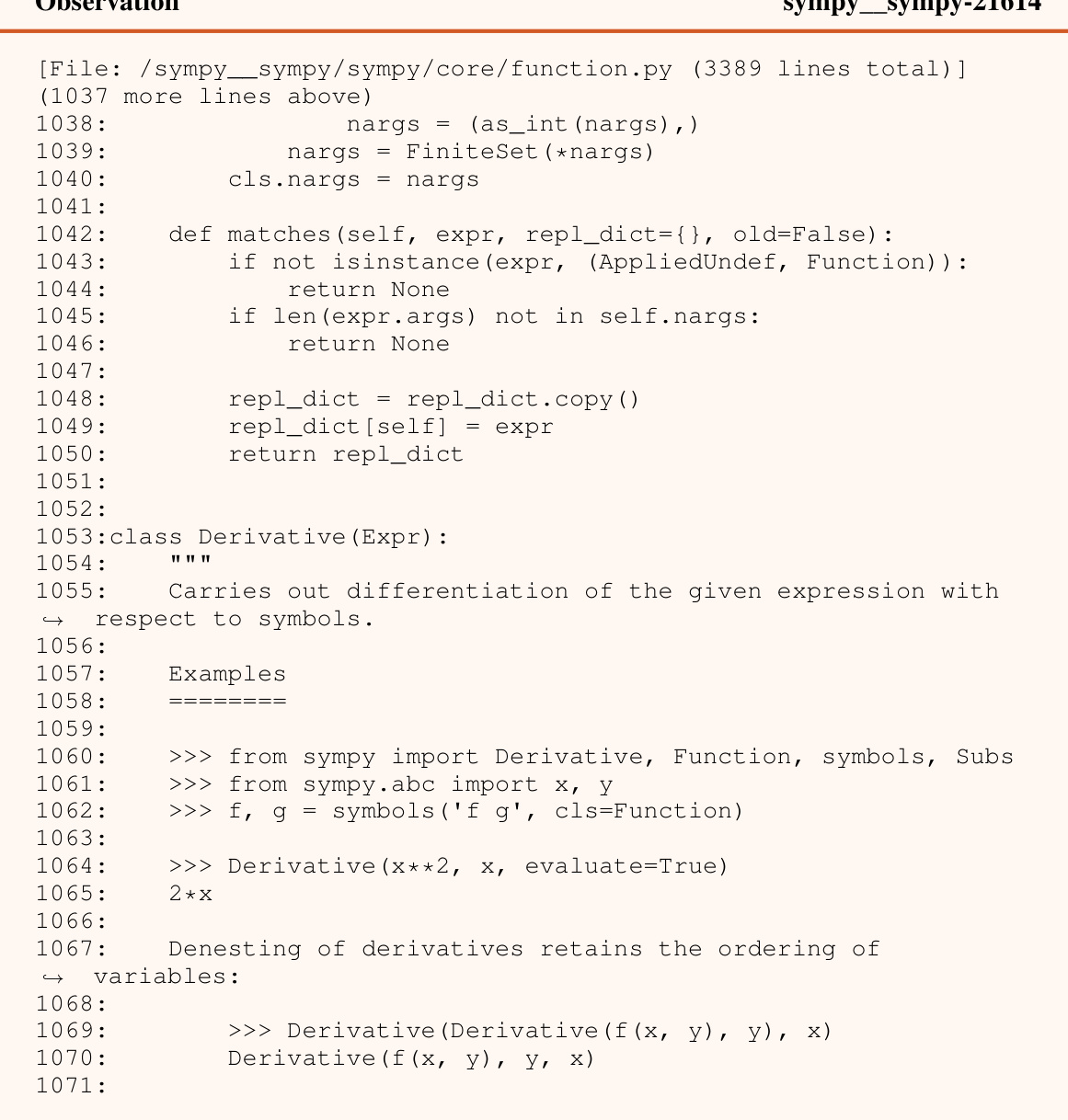

Visual Insights#

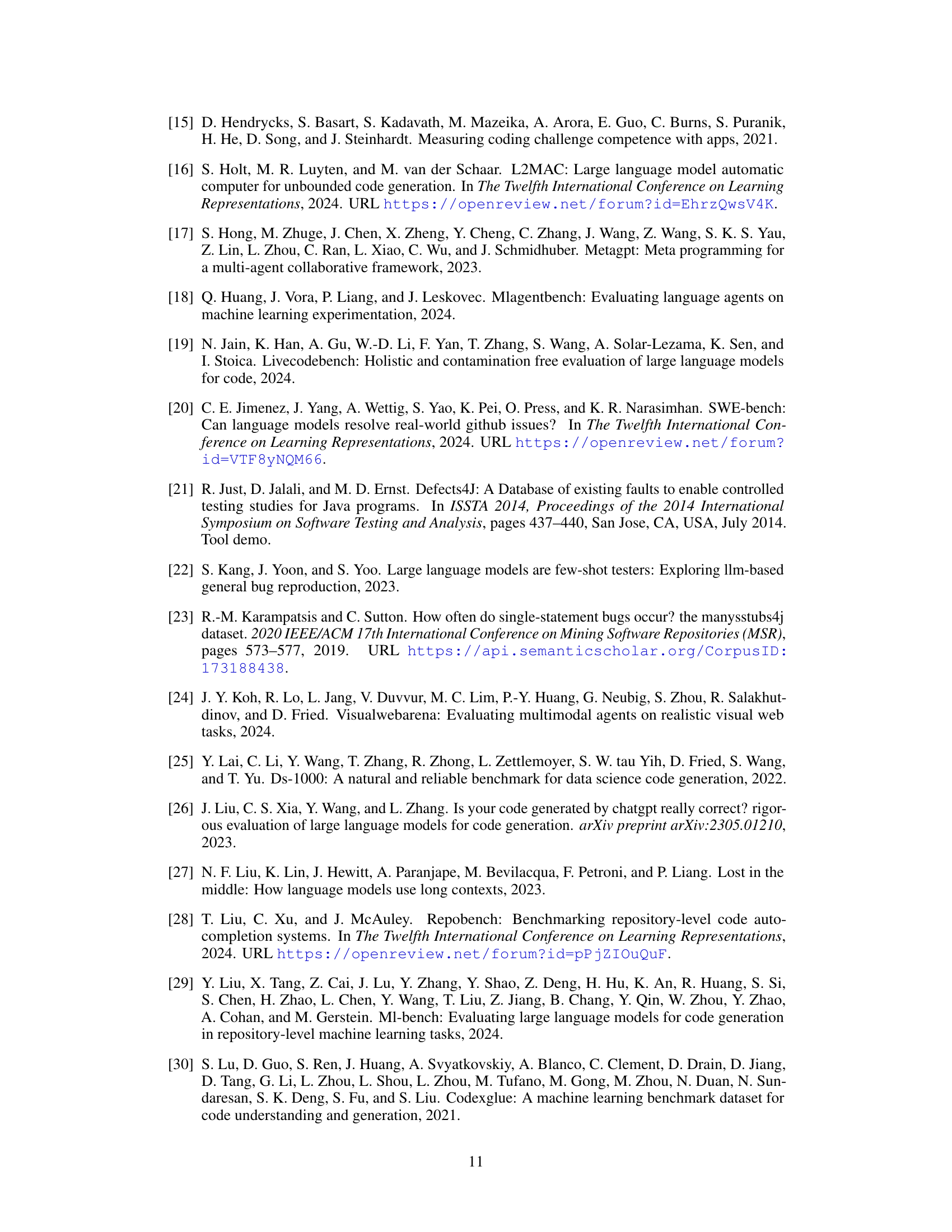

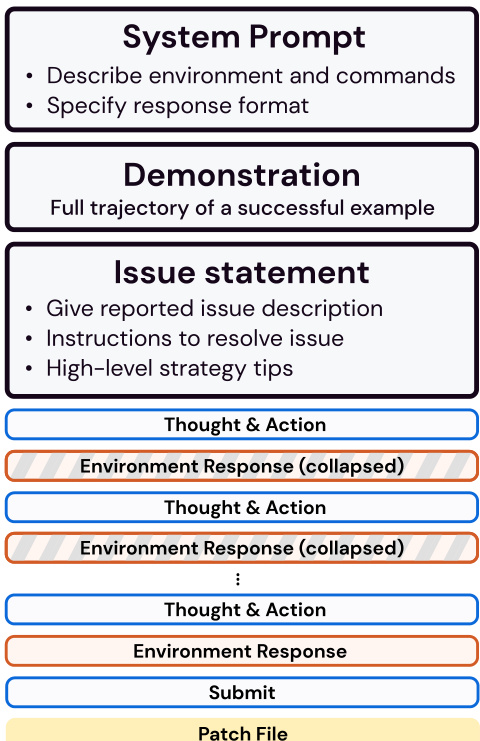

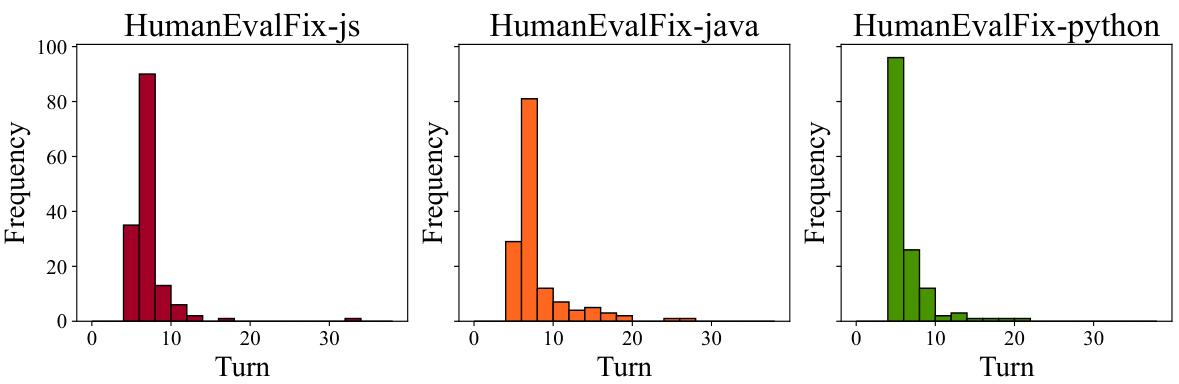

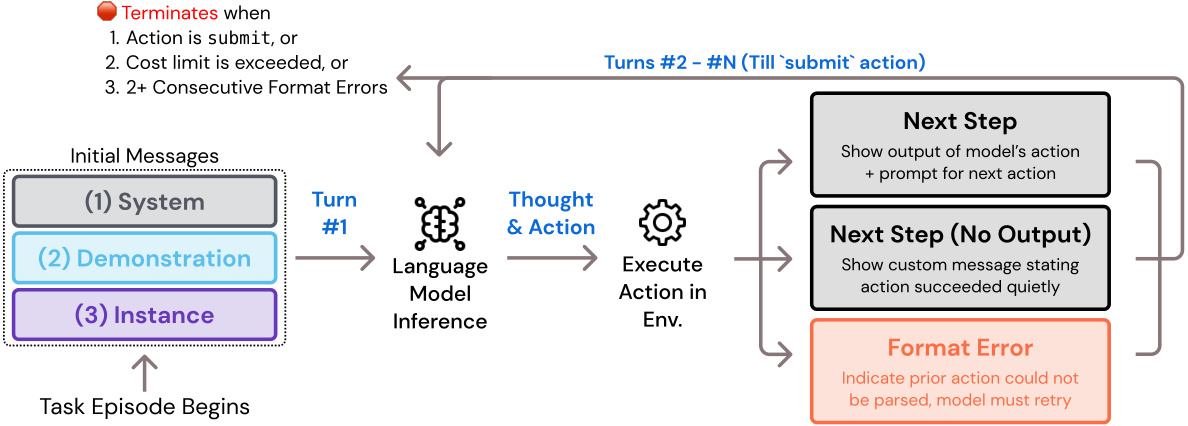

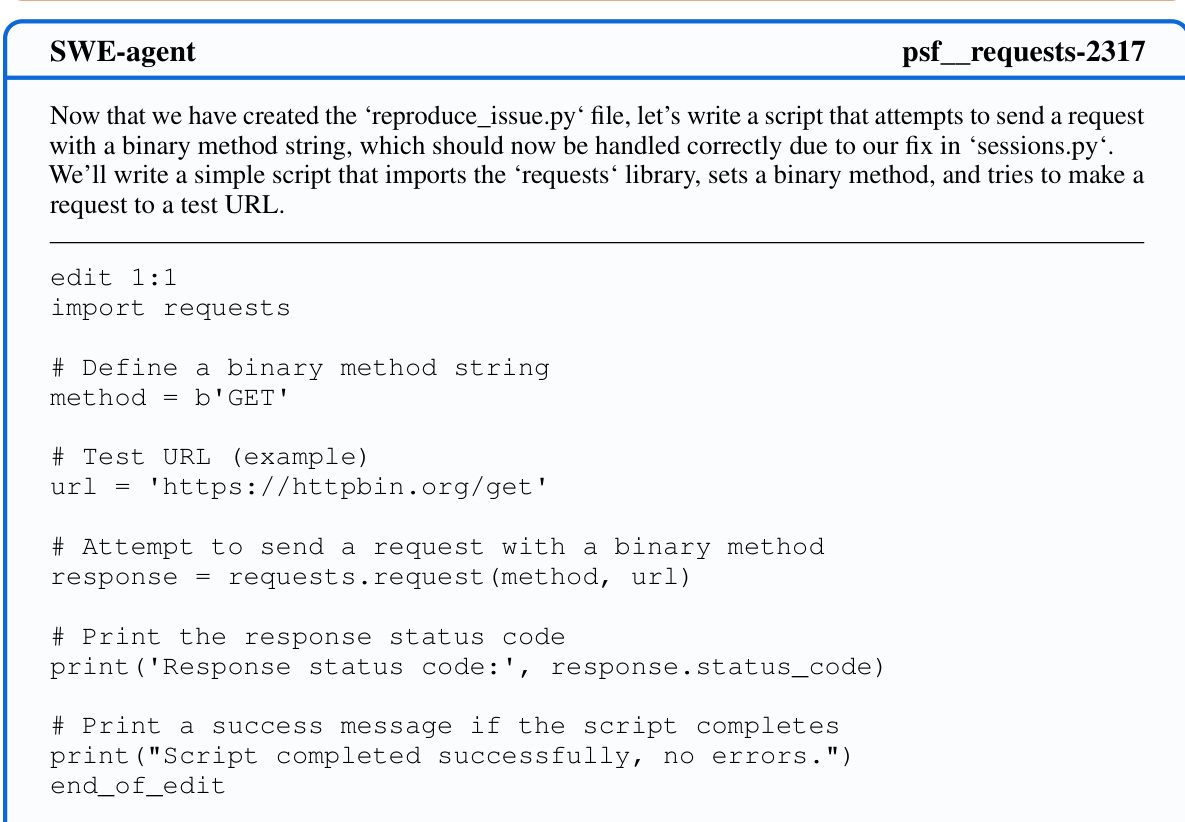

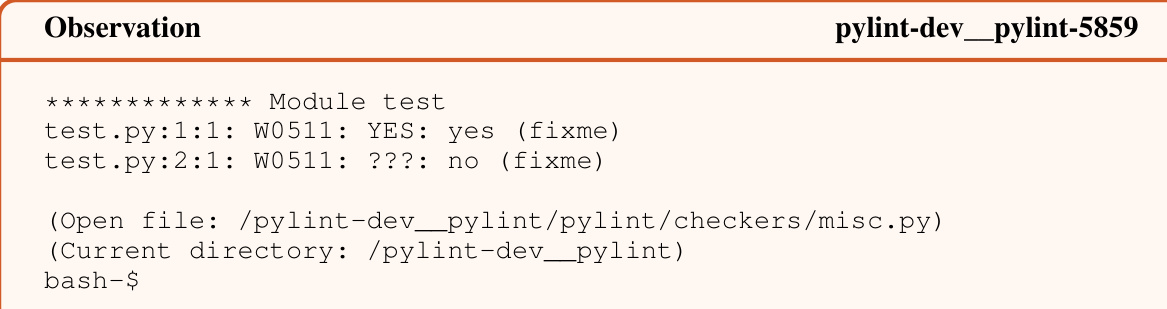

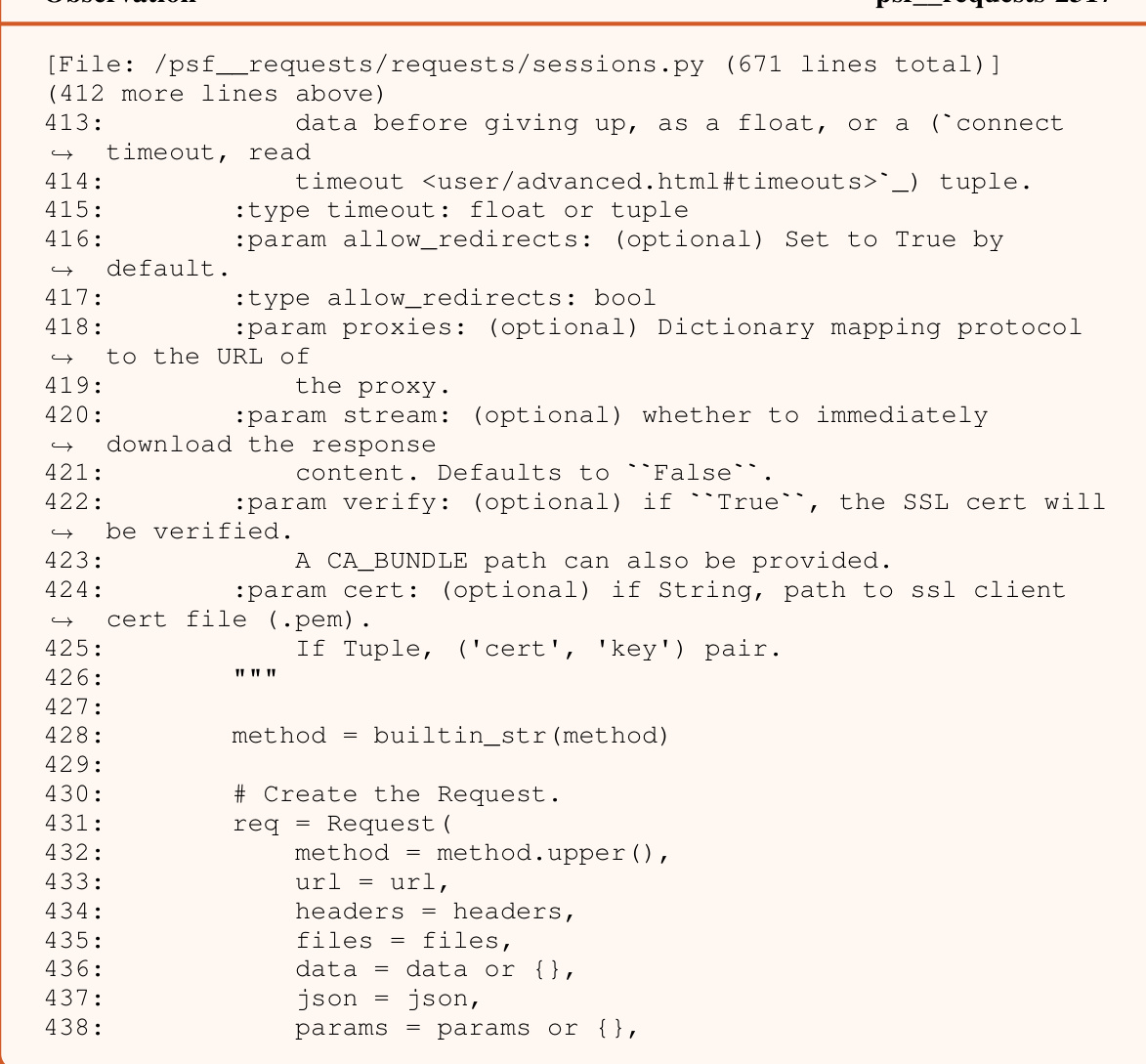

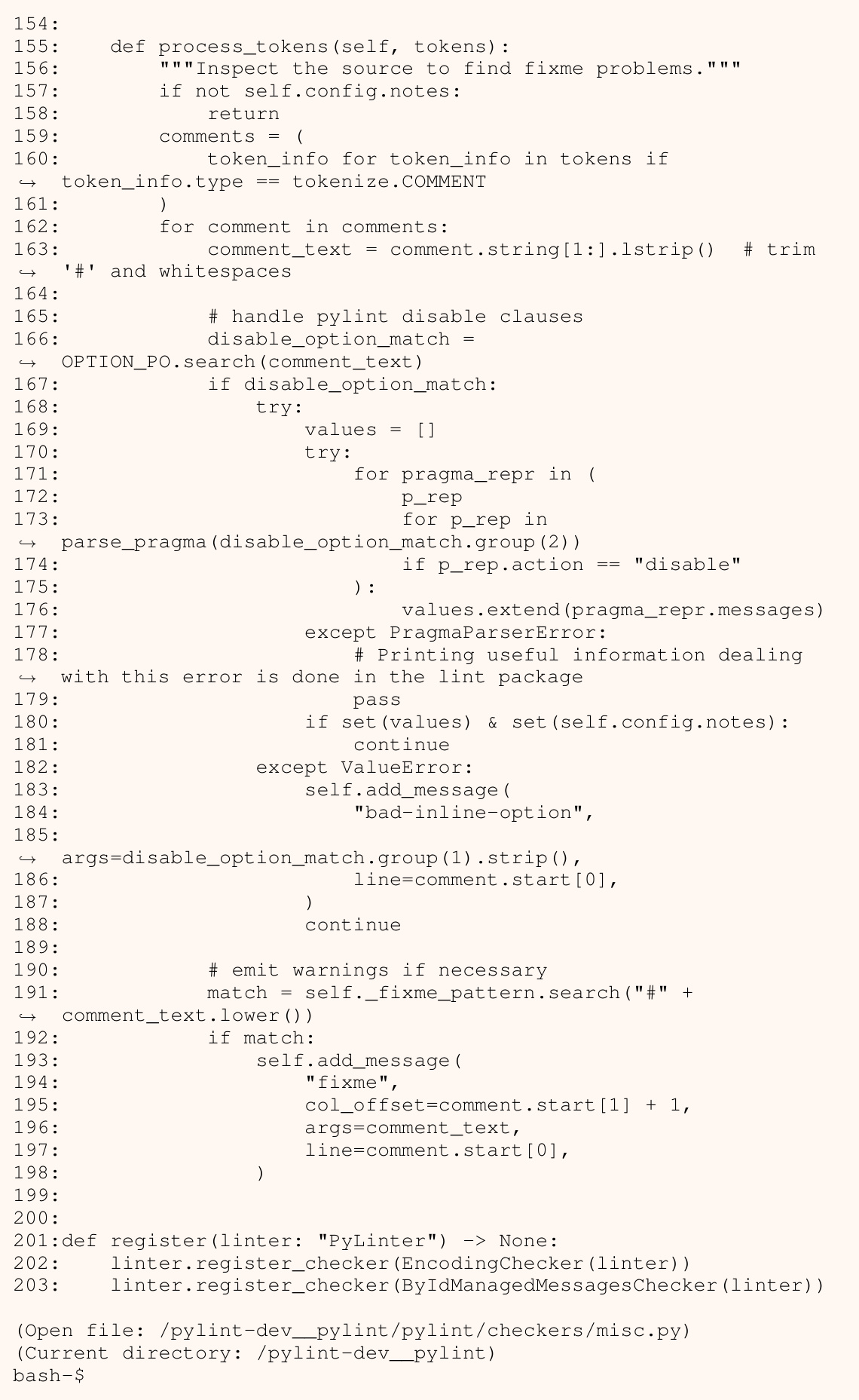

The figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent, which consists of an LM agent, an agent-computer interface (ACI), and a computer. The ACI acts as an abstraction layer between the LM agent and the computer, providing LM-friendly commands and environment feedback. The LM agent uses the ACI to interact with the computer’s terminal and filesystem, allowing it to perform software engineering tasks. The diagram highlights the flow of information between these components.

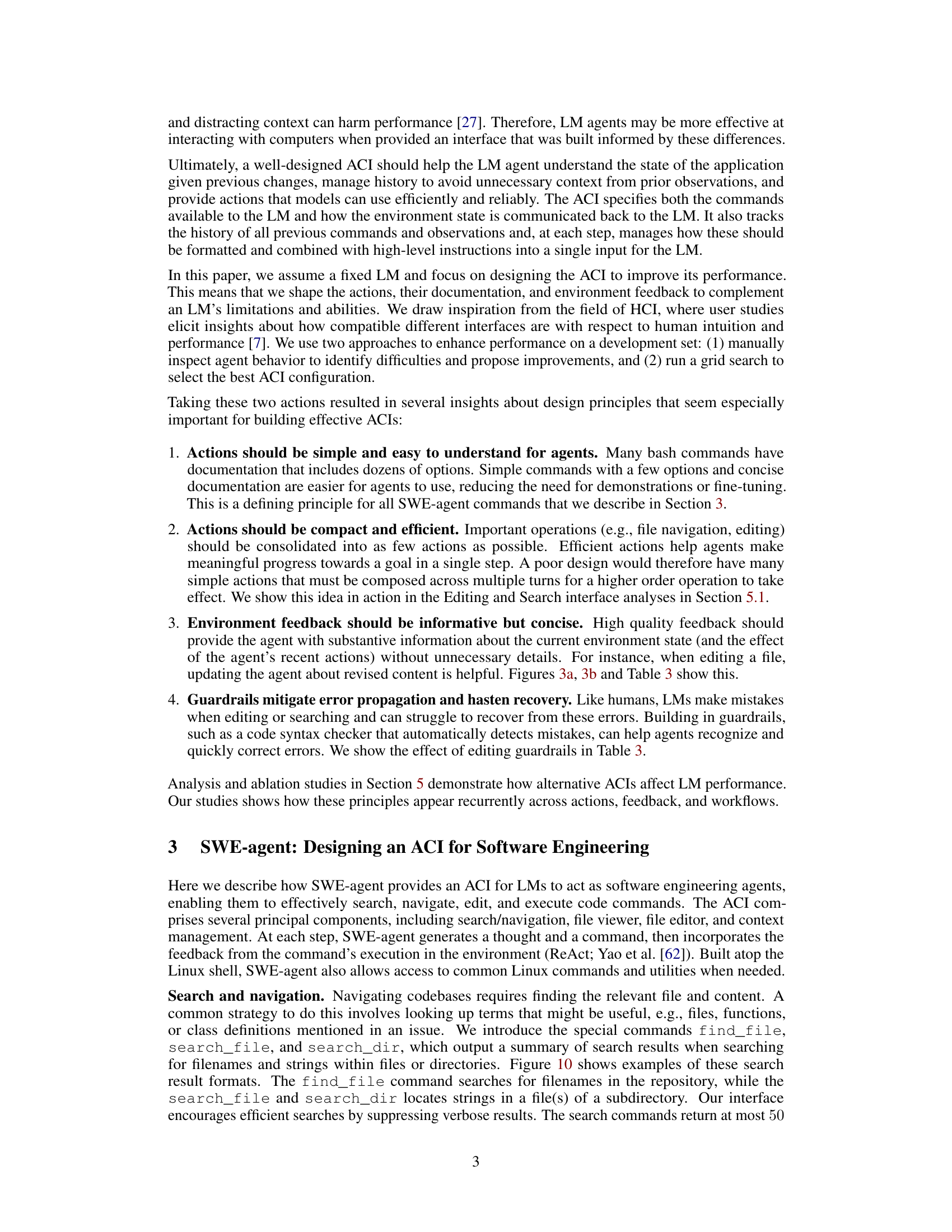

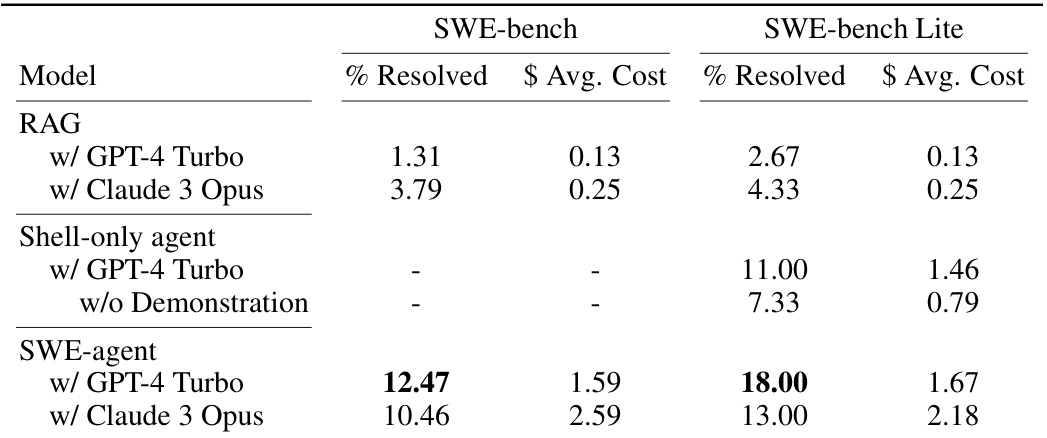

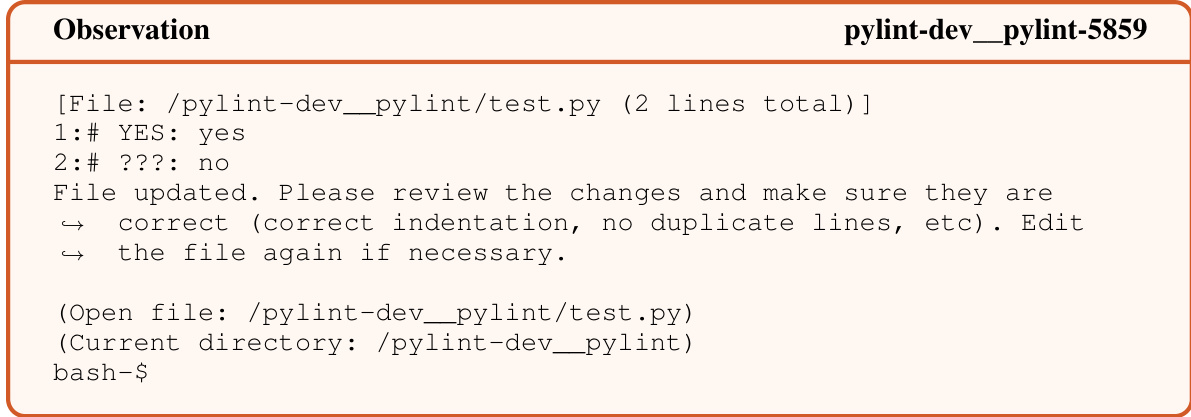

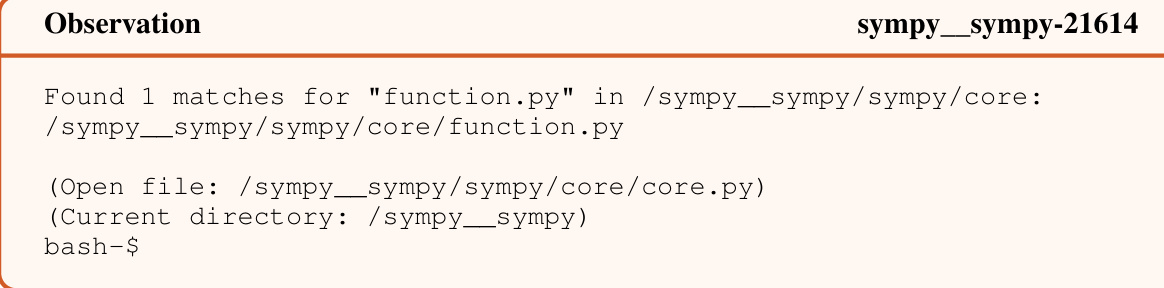

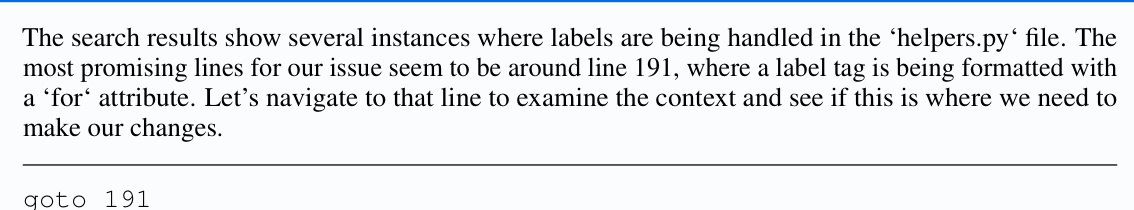

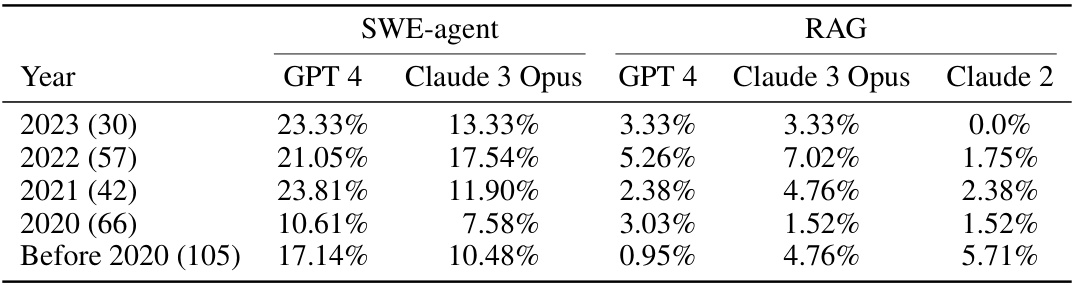

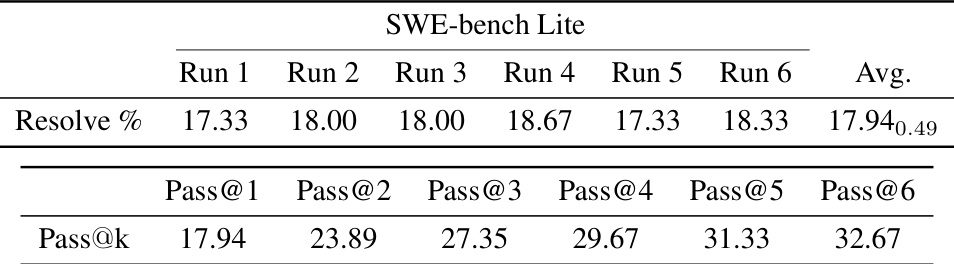

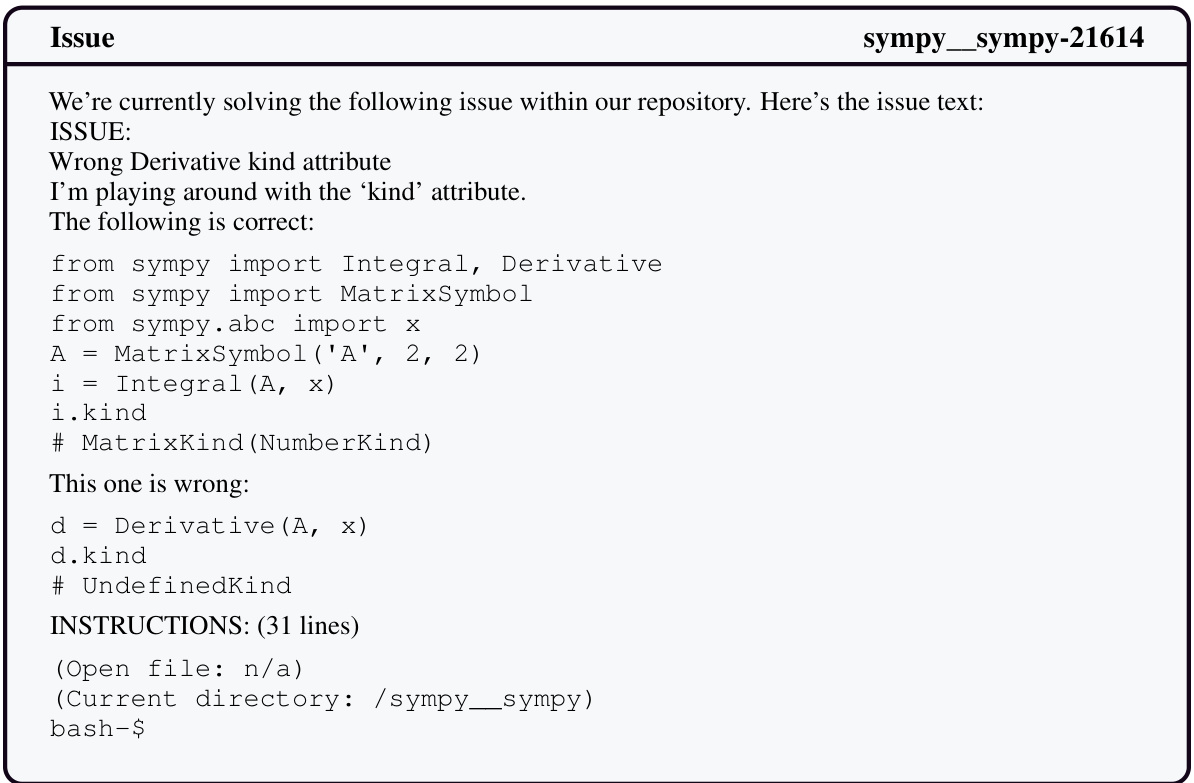

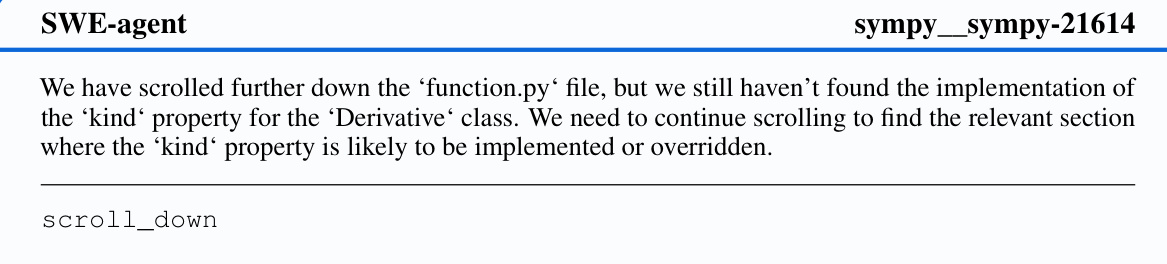

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments, comparing its performance on the SWE-bench dataset with various baseline models. The table is broken down into two sections: the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. For each dataset, the results for three main approaches are reported: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation), the Shell-only agent, and the SWE-agent. For each approach, the percentage of instances resolved and the average cost are listed for both GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus models. The results showcase the improved performance of SWE-agent compared to the baselines, demonstrating the effectiveness of its custom agent-computer interface.

In-depth insights#

LM-Agent Interface#

The effectiveness of large language models (LLMs) in software engineering hinges significantly on the design of their interfaces. A thoughtfully designed LM-agent interface acts as a crucial bridge, translating complex software tasks into LLM-understandable instructions and feedback. Simplicity and clarity are paramount; the interface should avoid overwhelming the LLM with extraneous details, focusing on a concise set of actions relevant to the specific tasks. Context management is crucial to avoid errors; the interface should efficiently track and present relevant information to the LLM without overwhelming its processing capabilities. Error handling is also crucial; a well-designed interface prevents LLM errors from escalating by implementing guardrails, concise feedback mechanisms, and prompt engineering strategies that help the LLM recover from mistakes. Ultimately, a successful LM-agent interface requires a deep understanding of the LLM’s strengths and limitations, translating human-centric design principles into LLM-centric considerations for optimal performance.

ACI Design Choices#

The efficacy of Large Language Model (LLM) agents hinges significantly on the design of their Agent-Computer Interfaces (ACIs). Careful ACI design is crucial because LLMs have unique strengths and weaknesses compared to human users. Simplicity and efficiency in action design are paramount; complex commands overwhelm LLMs, whereas concise, easily understood actions maximize their capabilities. Informative, yet concise feedback is also essential; LLMs struggle with verbose output, requiring carefully crafted responses that provide necessary information without unnecessary detail. Error handling and guardrails are vital to mitigate LLM mistakes and ensure robust performance; features like syntax checking can significantly enhance task completion. The optimal ACI is not simply a translation of existing human-centric interfaces but rather a purpose-built system tailored to the unique cognitive capabilities and limitations of LLMs. The interactive nature of the ACI allows for iterative feedback loops, crucial for handling the complexities of software engineering tasks. Ultimately, successful ACI design requires a deep understanding of LLM behavior to create an interface that facilitates their strengths while mitigating their weaknesses.

SWE-Agent System#

The SWE-Agent system is a novel approach to automated software engineering that leverages the power of large language models (LLMs). Its core innovation is the Agent-Computer Interface (ACI), a custom-designed layer that simplifies the interaction between the LLM and the computer, enhancing the LLM’s ability to perform complex software engineering tasks. The ACI achieves this by providing a simplified set of commands and a concise feedback mechanism, addressing the limitations of LLMs in directly interacting with complex software environments. By abstracting away granular details, the ACI allows the agent to more efficiently and reliably solve problems, and this is evidenced by SWE-Agent achieving state-of-the-art results on multiple benchmarks. Furthermore, the system’s design is modular and extensible. This makes it adaptable to various LMs and software projects, highlighting its potential for broad applicability in the field of automated software engineering. The open-source nature of the system facilitates collaborative research and development, accelerating progress in this emerging area.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on agent-computer interfaces (ACI) for language models (LM) are multifaceted. Improving ACI design is paramount; current methods are manual, highlighting the need for automated techniques that learn from agent behavior and iteratively refine interface components. This includes exploring the use of reinforcement learning to optimize ACI design choices. Expanding the scope of ACIs beyond software engineering tasks is crucial; applying these principles to other digital domains (e.g., web browsing, data analysis) presents rich opportunities. Furthermore, investigating the effect of different LM architectures and prompting strategies on ACI performance is essential. Addressing limitations identified in the study, such as the challenges related to editing and error recovery, is key. Developing more sophisticated context management mechanisms to allow LMs to effectively handle long-range dependencies in complex tasks warrants further investigation. Finally, exploring the ethical implications of increasingly capable LM agents operating in real-world environments and defining robust safety mechanisms are critical to responsible innovation.

Ethical Implications#

Ethical implications of using large language models (LLMs) for automated software engineering are significant. Data privacy is paramount; LLMs trained on code repositories may inadvertently memorize sensitive information. Security is another key concern; malicious code generation is possible, necessitating robust safeguards. Bias and fairness in LLMs are also an issue; biased training data could lead to discriminatory outcomes in the software produced. Transparency is vital; users should understand how the system works and the potential risks. Accountability needs to be established, determining who is responsible when LLM-generated code causes problems. Job displacement due to automation is another potential impact. Access to these technologies should be equitable to avoid exacerbating existing digital divides. Careful consideration of these issues is critical for the responsible development and deployment of LLM-based software engineering tools.

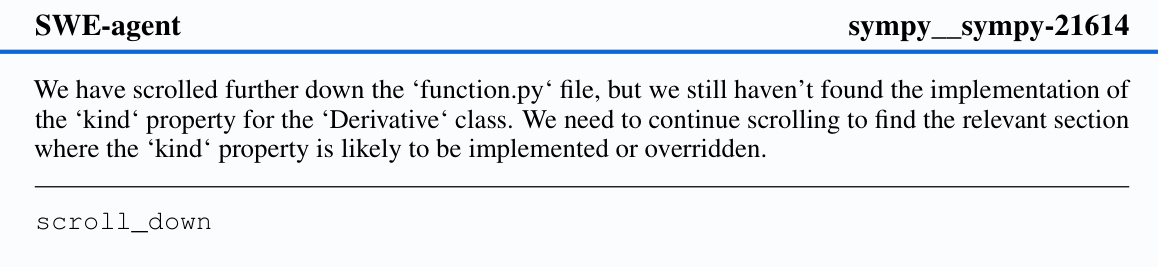

More visual insights#

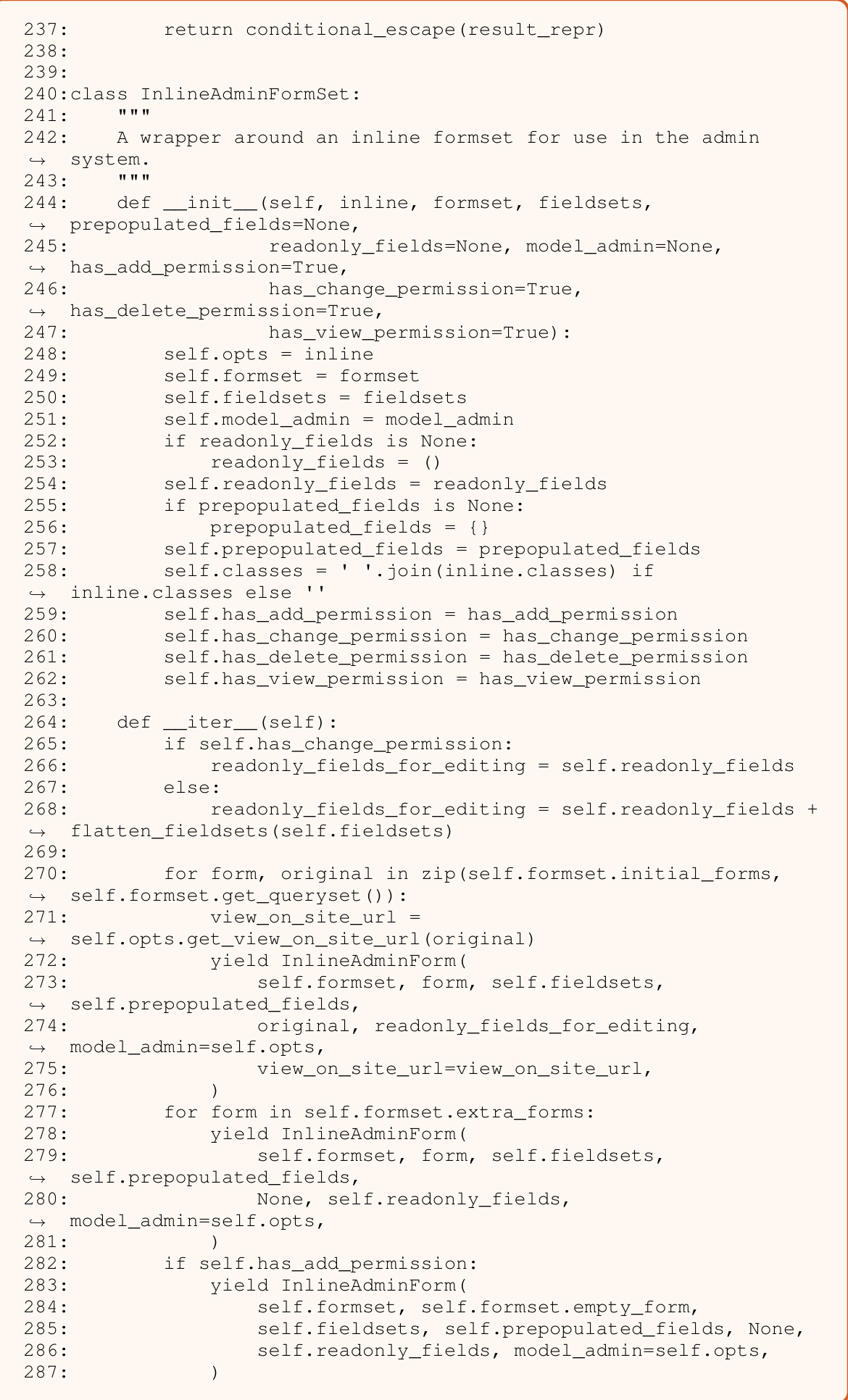

More on figures

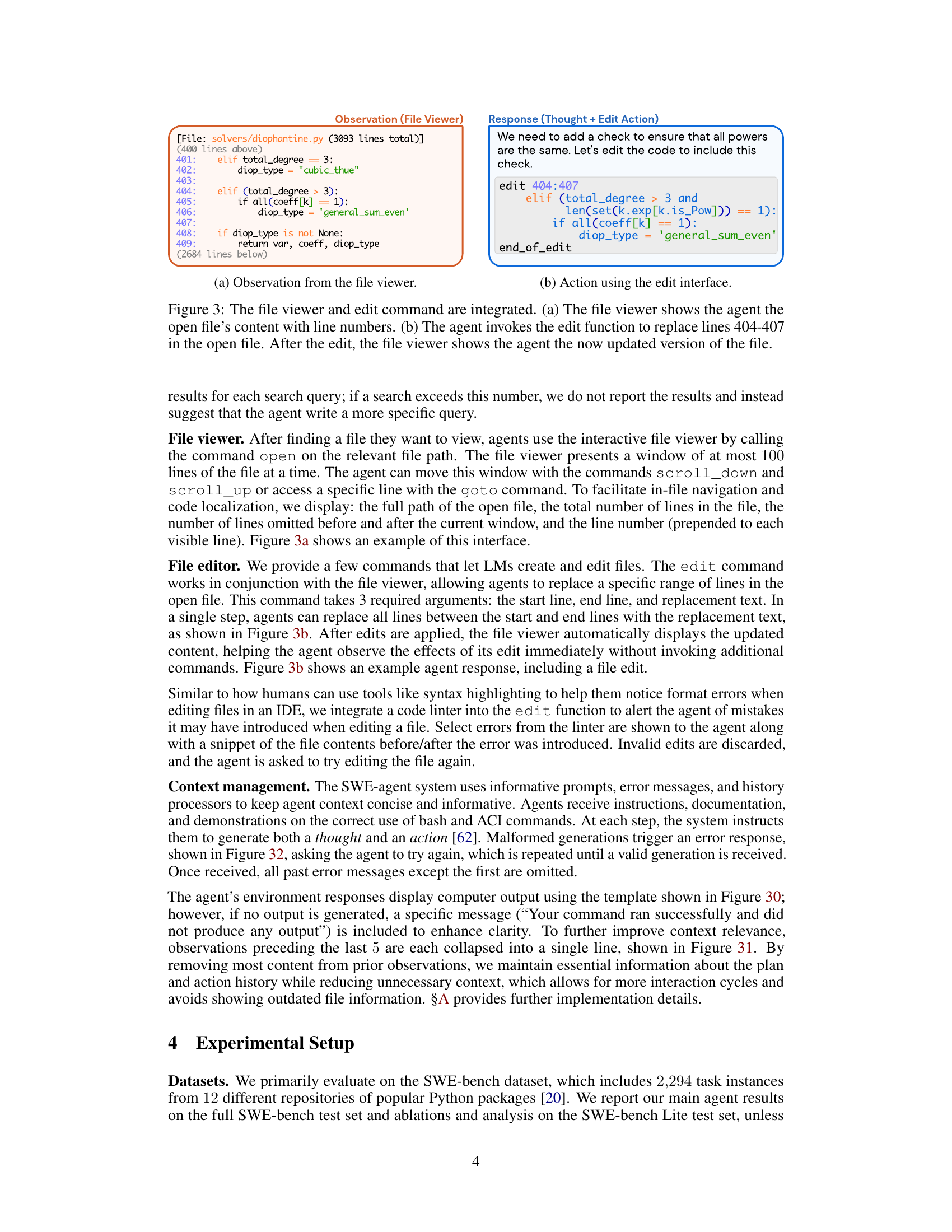

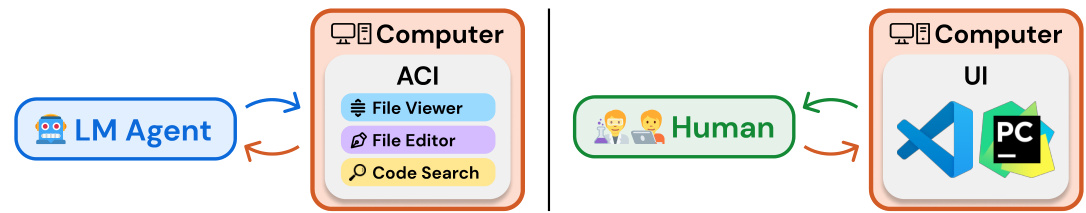

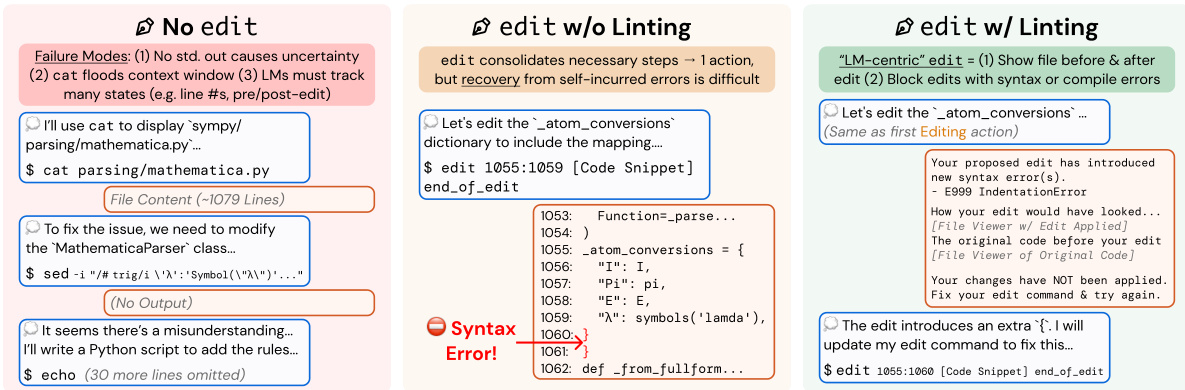

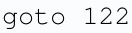

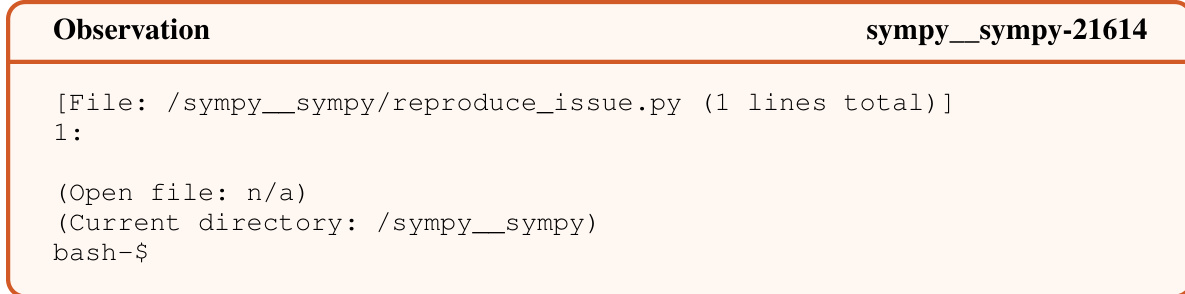

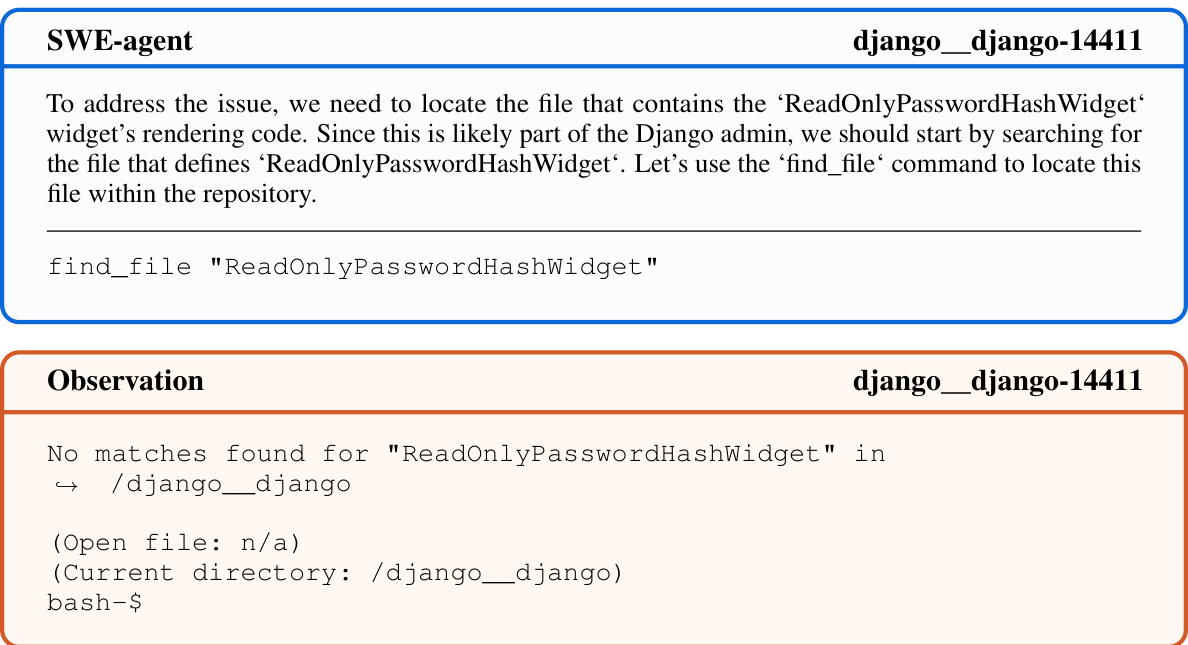

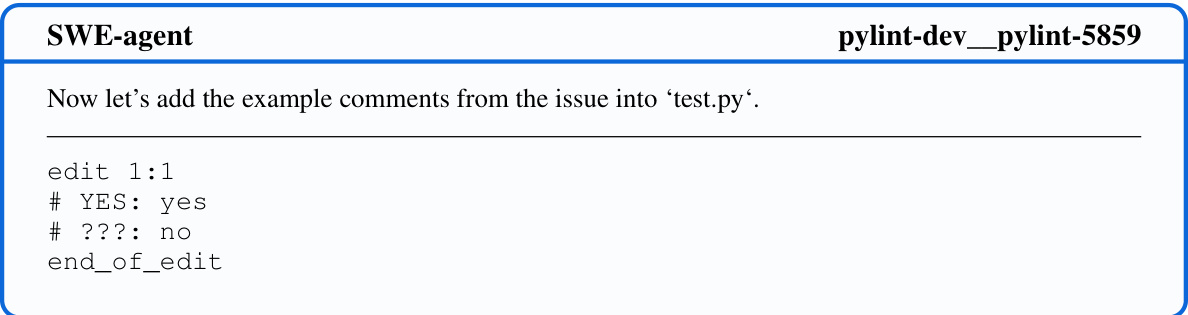

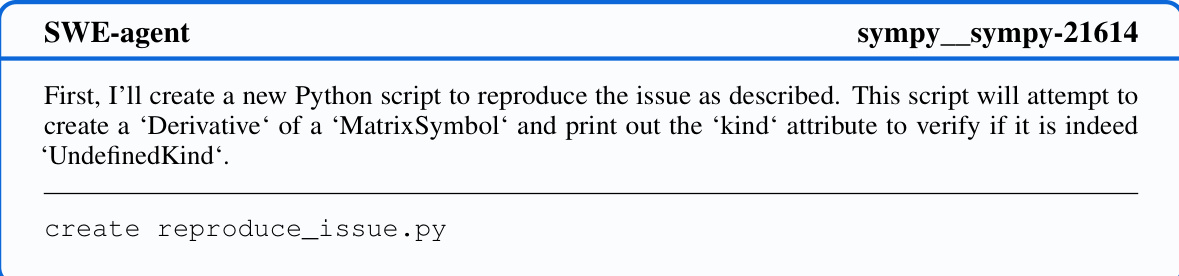

This figure shows a comparison between the human-computer interaction (HCI) and the agent-computer interaction (ACI). The left side shows how a large language model (LLM) agent interacts with a computer via a custom-designed ACI. The ACI provides LLM-friendly commands for navigating repositories, viewing and editing files, and searching for code. The right side illustrates how a human interacts with a computer using a standard User Interface (UI) such as VSCode. The image highlights the key difference in how different users (LLMs vs humans) interact with computers and underscores the need for specialized interfaces tailored to the capabilities and limitations of LLMs.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through an abstraction layer called an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands the agent can use to interact with the computer (e.g., navigate a repository, search for files, view files, edit lines) and specifies the format of feedback from the computer to the agent. This allows the LM agent to execute a series of actions on the computer in response to a task.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly, via an abstraction layer called the Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands the agent can use to interact with the computer and the format of feedback that it receives from the computer. The figure highlights the key components: the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer’s terminal and file system. This interaction setup is crucial to the performance of SWE-agent.

This figure shows the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, translating between LM-friendly commands and the computer’s functionalities. The ACI provides the agent with commands to interact with files (navigate the repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and feedback from the computer in a format the LM can easily understand.

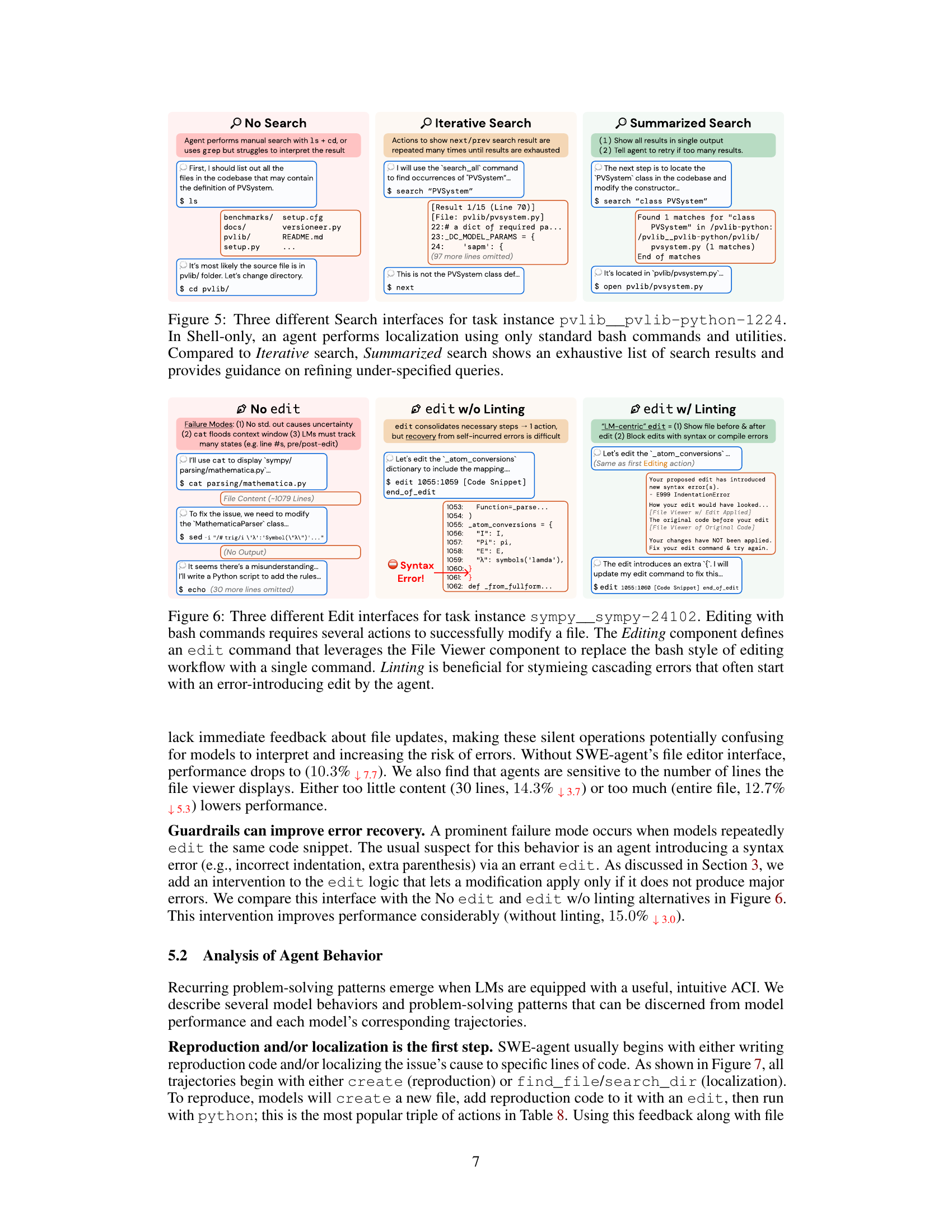

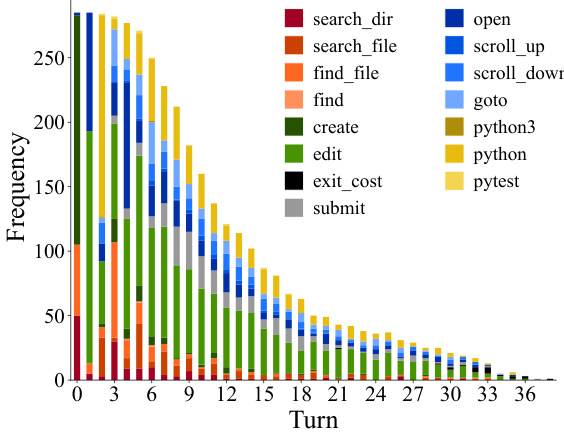

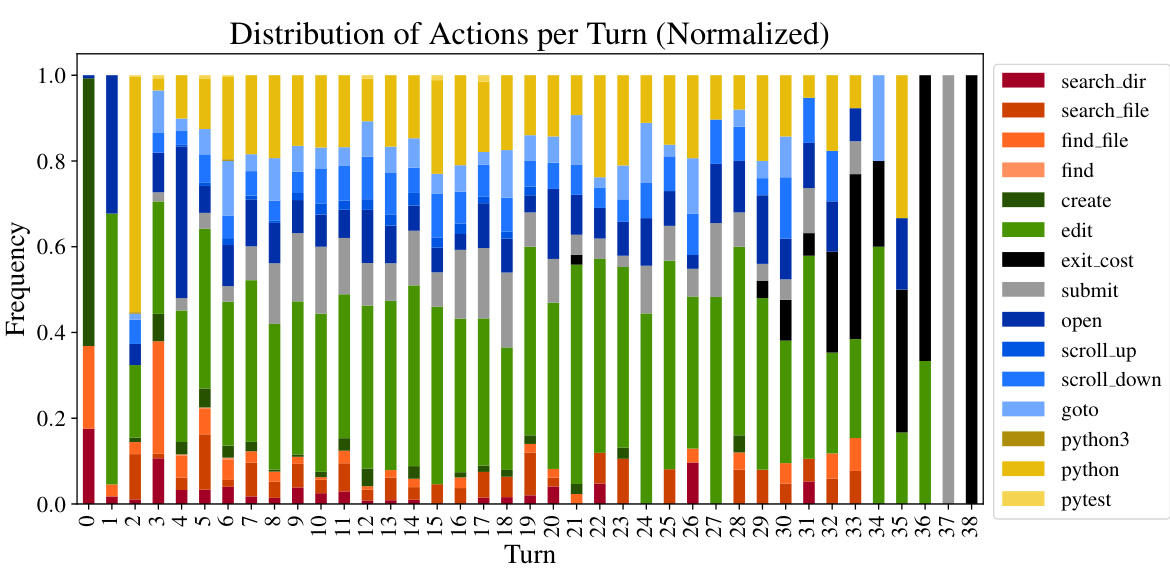

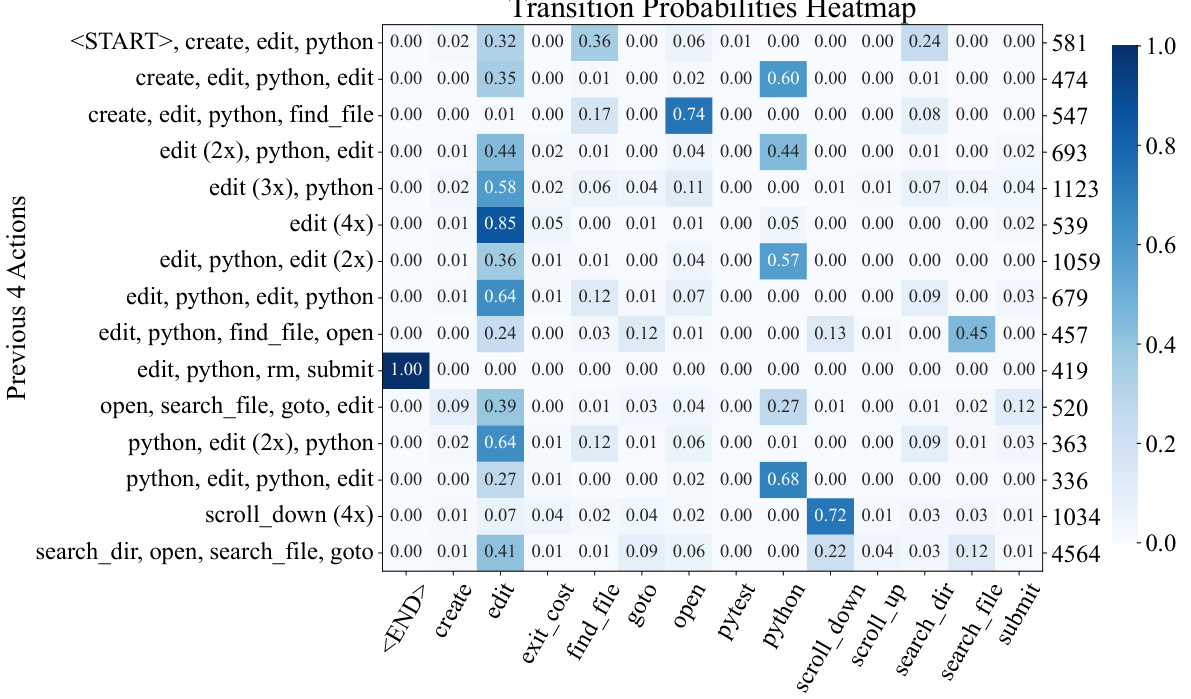

This figure shows the frequency of actions taken at different turns in successful trajectories of SWE-agent. The x-axis represents the turn number and the y-axis represents the frequency of each action. The actions are color-coded to easily visualize which actions are most frequent at which turns. Note that the trajectories are only from those that were successfully resolved.

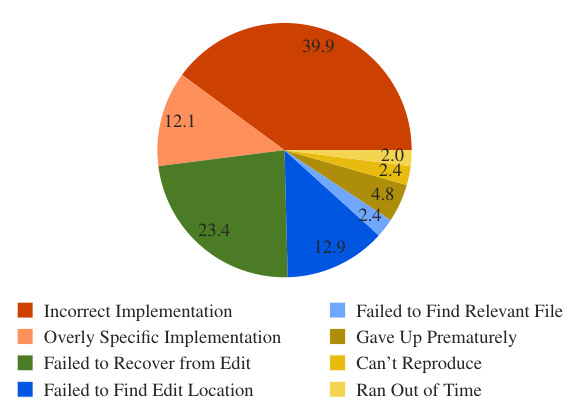

This figure shows a pie chart that breaks down the reasons why SWE-agent failed to solve a problem. The categories are based on a manual analysis of the trajectories, and each slice represents the percentage of failures attributable to a specific reason. The categories and their percentage breakdown are given in the legend.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. SWE-agent uses a language model (LM) to interact with a computer. The interaction is mediated by a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI provides the LM with a set of commands to interact with the computer, such as navigating a repository, searching for files, viewing files, and editing files. The ACI also provides the LM with feedback from the computer in a structured format. This allows the LM to understand the state of the computer and make informed decisions. The feedback includes the commands used by the agent, the results of those commands, and the current state of the computer.

The figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer via a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI is depicted as a layer between the LM agent and the computer system. It shows the flow of LM-friendly commands from the agent to the computer, and the flow of LM-friendly environment feedback from the computer back to the agent. The ACI simplifies interactions for the LM agent compared to a standard terminal interaction. The feedback mechanisms are designed to provide concise and relevant information, which contrasts with the more granular and complex information typically available through standard interfaces. This design helps address challenges encountered when using language models in complex software engineering tasks.

This figure shows a high-level overview of the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI translates between LM-friendly commands (e.g., ’navigate repo’, ’edit lines’) and computer actions, receiving feedback from the computer in a format that is easy for the LM to understand. The ACI acts as an abstraction layer that simplifies interactions, helping the LM agent perform complex software engineering tasks. The figure highlights the key components: the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer system (including the terminal and file system).

The figure shows a schematic of the SWE-agent system. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions the computer can understand and provides the LM with feedback about the results of the actions. The ACI is designed to be more user-friendly for LM agents than existing interfaces like the Linux shell.

This figure shows the overall architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer, but not directly. Instead, there is an abstraction layer called an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI handles commands from the LM agent to the computer, and formats the computer’s responses for the LM. The diagram highlights the flow of information, showing how the LM sends commands, receives feedback, and interacts with the computer’s filesystem and terminal.

This figure shows the SWE-agent architecture, illustrating how a large language model (LM) interacts with a computer using a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction between the LM and the computer’s operating system, file system, and other tools. The figure highlights the flow of LM-friendly commands from the agent to the computer, and the structured feedback provided to the agent, enabling it to effectively perform software engineering tasks.

This figure shows a schematic of the SWE-agent system. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly via an abstraction layer called an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing a set of LM-friendly commands for interacting with the computer’s file system and terminal, and formats the feedback from the computer in a way that is easily understandable by the LM agent. This contrasts with a typical human-computer interaction where a user directly interacts with a complex terminal and file system.

This figure illustrates the architecture of SWE-agent, showing how a large language model (LM) interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an intermediary, translating LM commands into computer-understandable instructions and formatting the computer’s responses back to the LM. The ACI provides LM-friendly commands for interacting with files and the file system, allowing for actions such as navigating repositories, searching for files, viewing files, editing files, and executing commands.

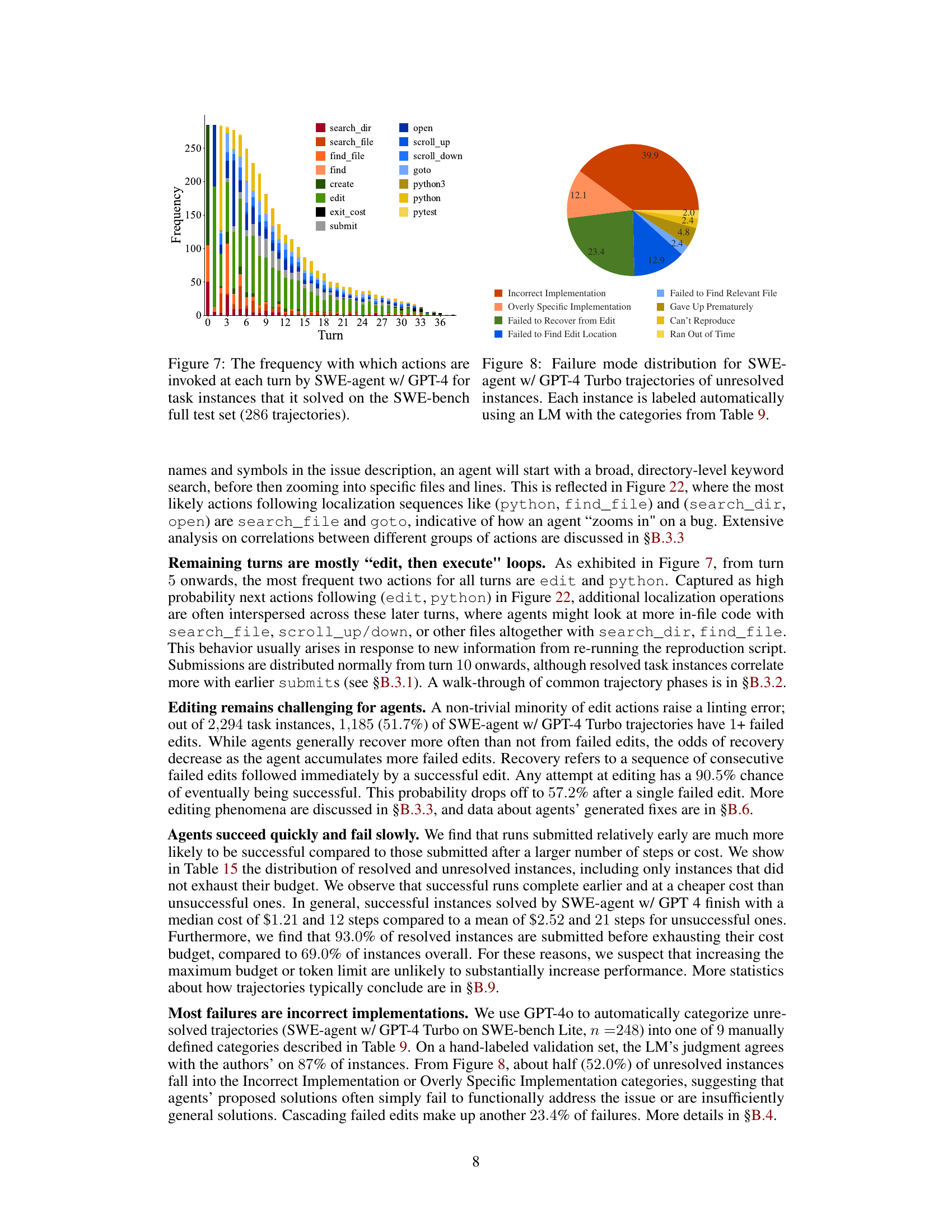

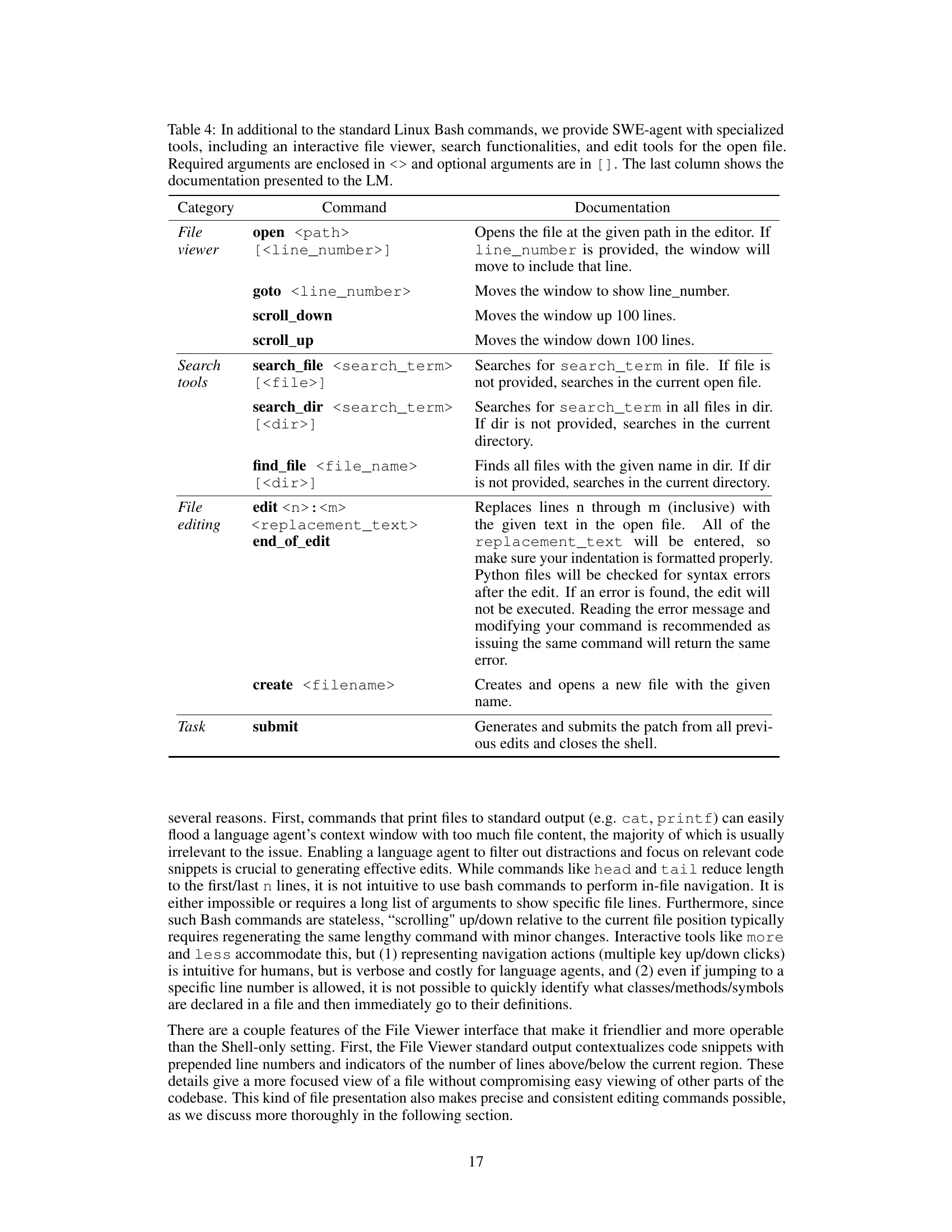

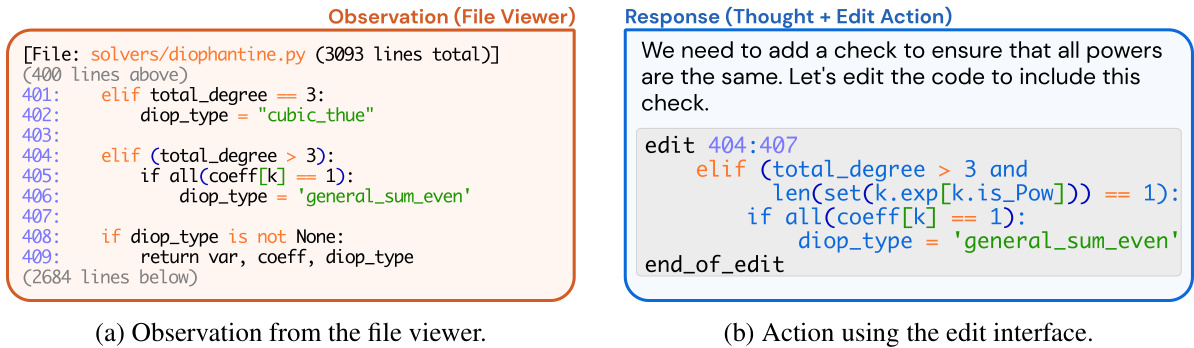

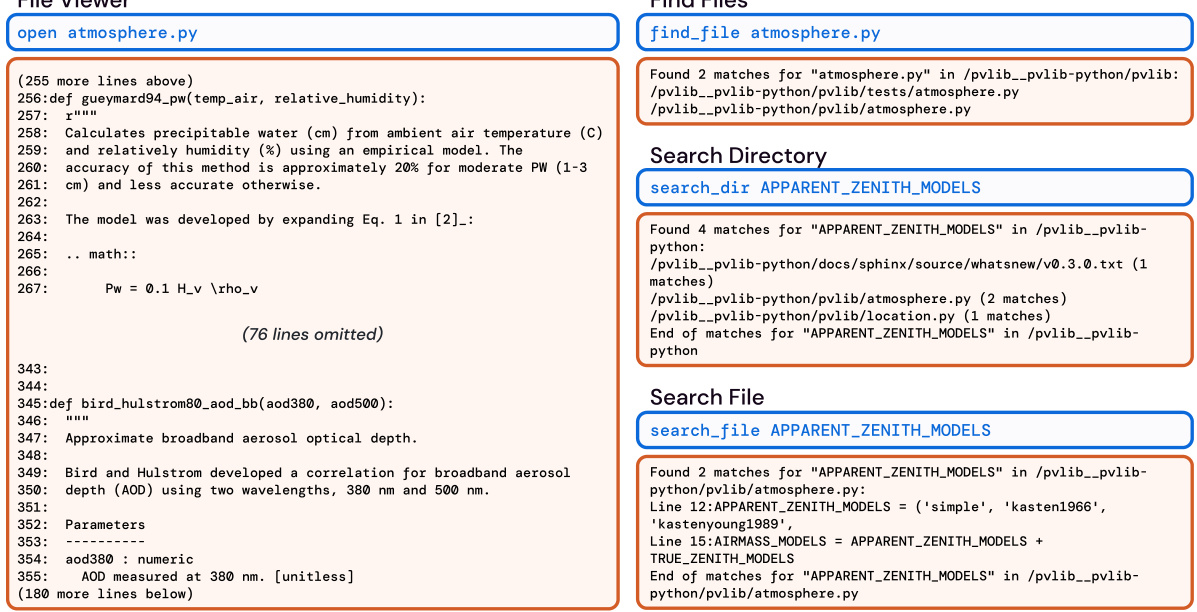

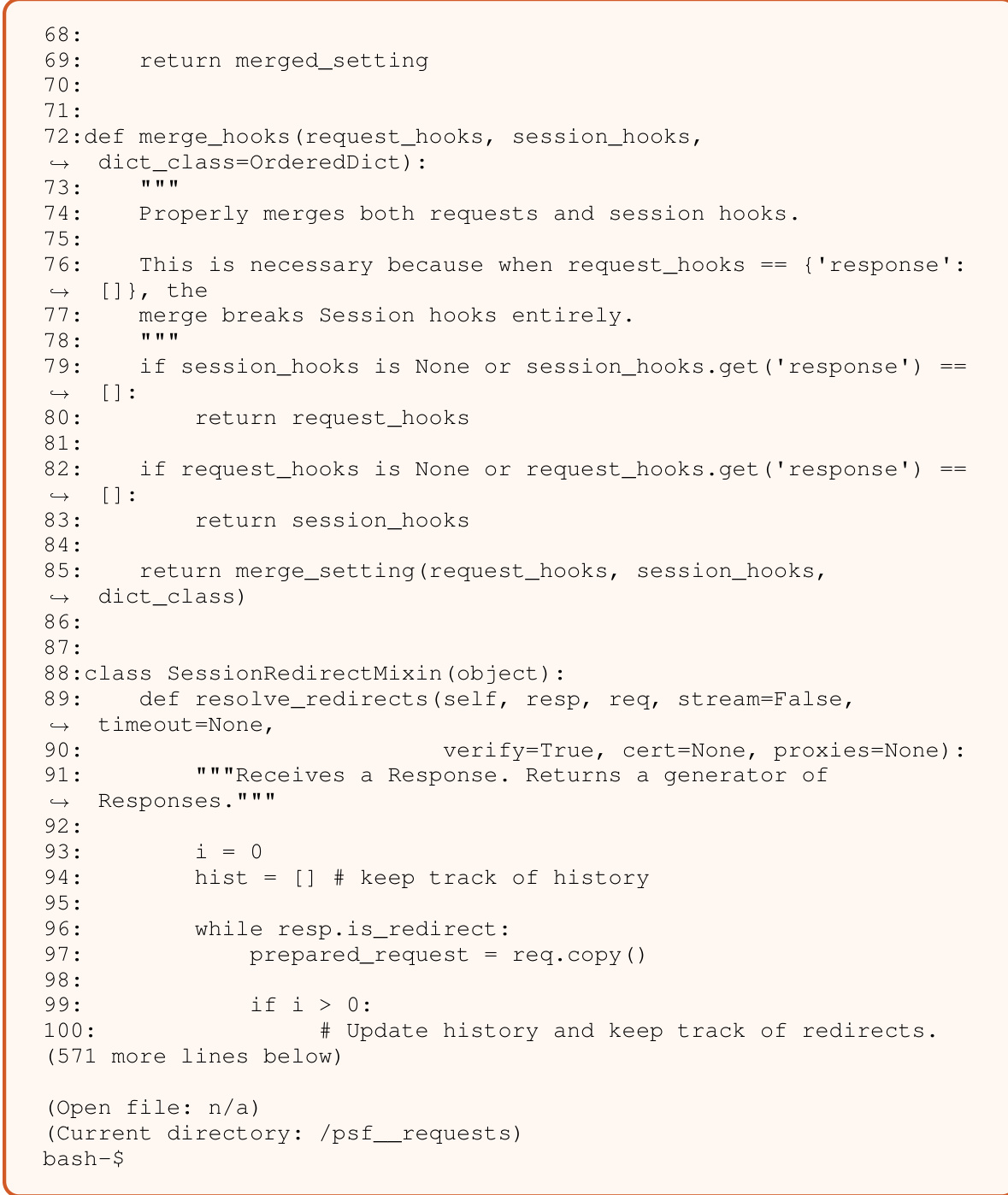

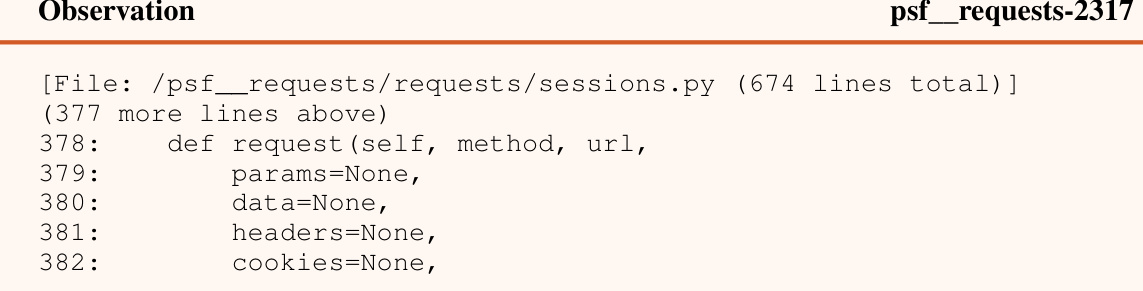

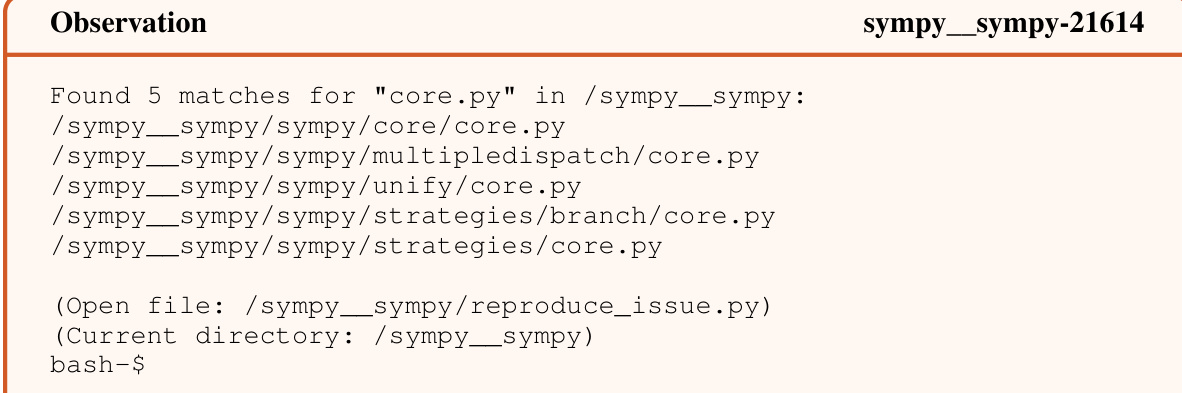

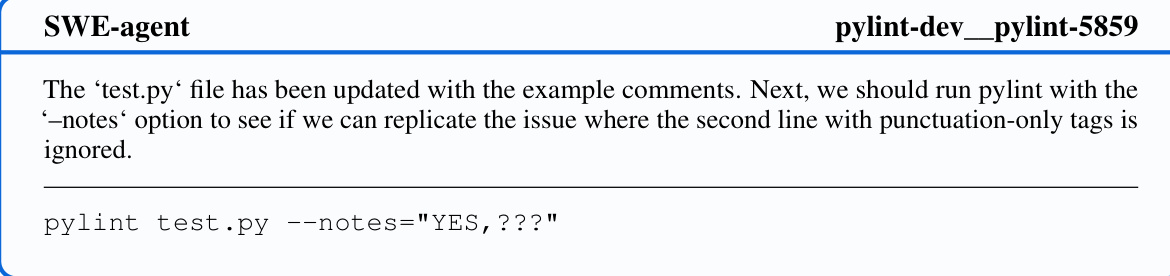

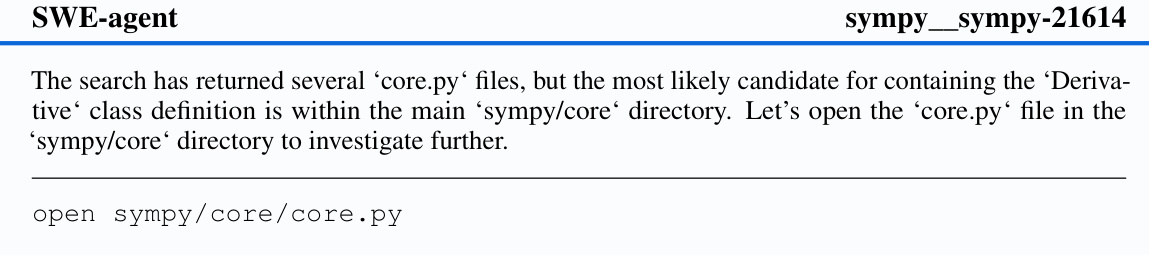

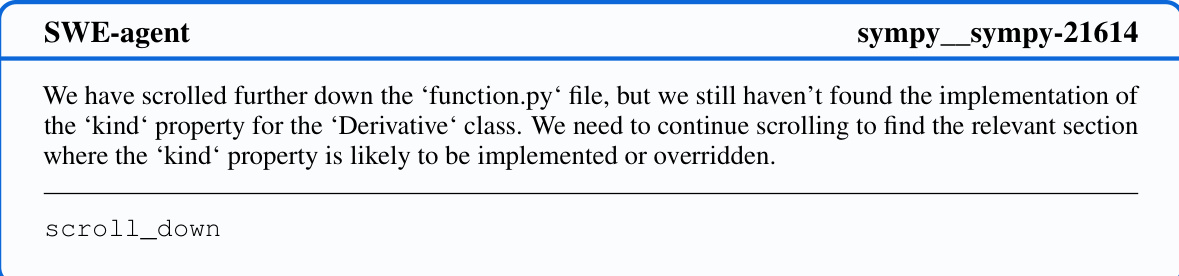

This figure shows two main components of the SWE-agent interface: the File Viewer and the Search tools. The File Viewer is designed to show a small window of a file’s contents at once, allowing the agent to efficiently scan through a file. The search tools are shown on the right. The figure shows examples of using the three commands to search for files and text. The caption also specifies that these are examples of real agent behavior.

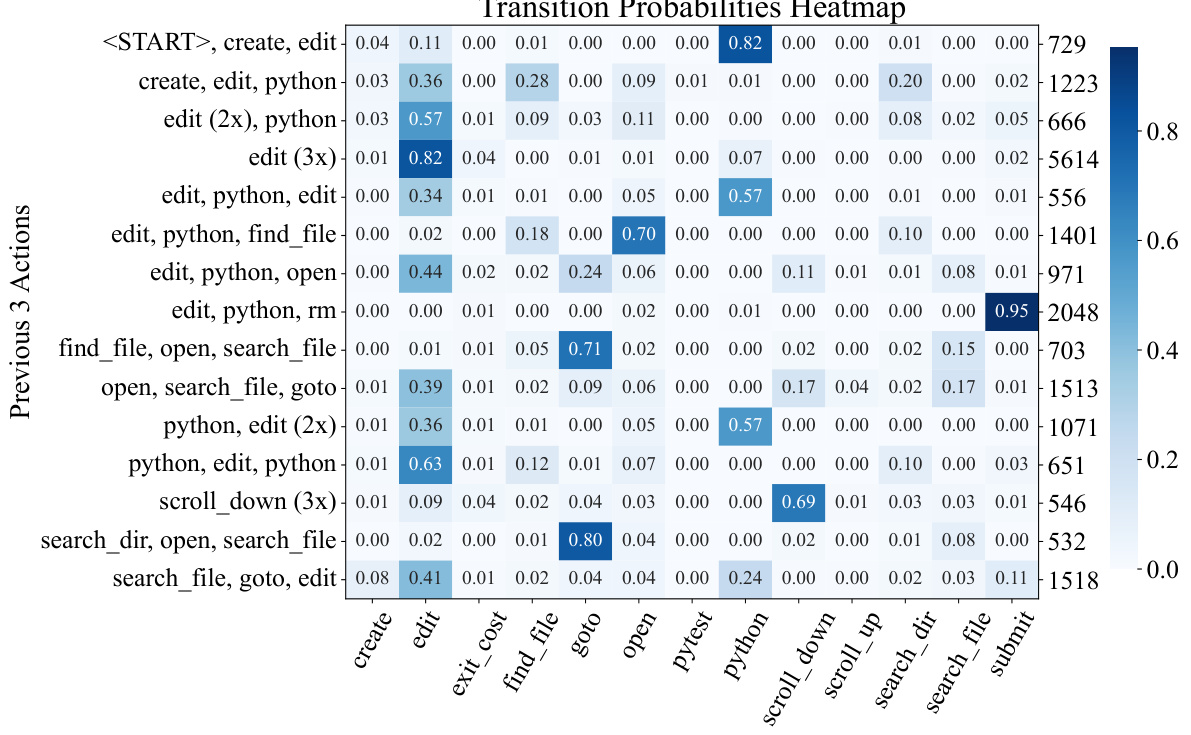

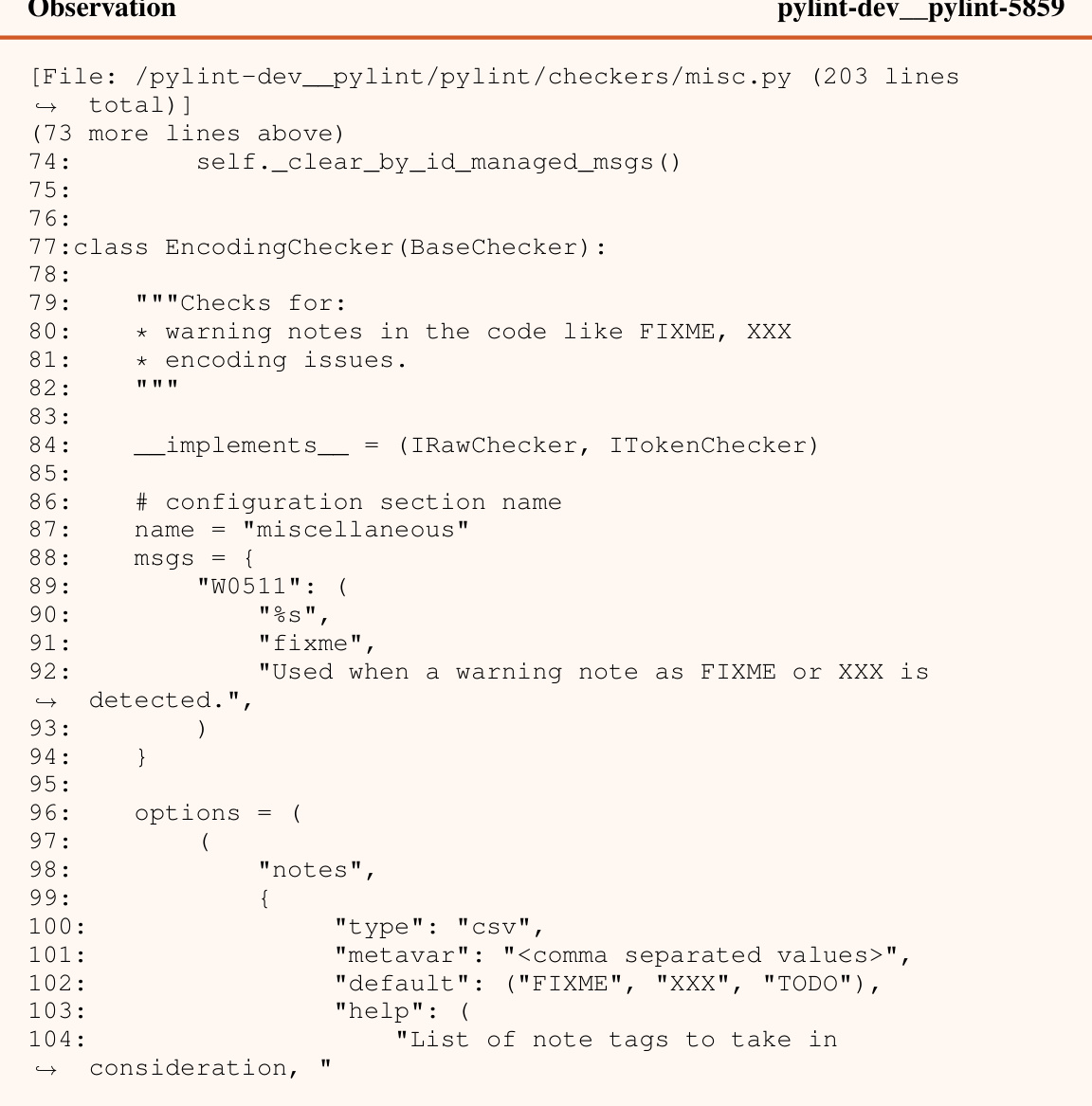

This figure shows a stacked bar chart that visualizes the distribution of action patterns across turns in a trajectory. Each bar represents a sequence of turns (e.g., 1-3 represents the first three turns). The bars are color-coded to represent the different categories of action patterns. The height of each bar shows how frequently those categories of actions are performed during those turns. This gives a visual representation of the relative frequency of each action type at different stages within a successful trajectory. The chart shows that certain action types (like reproduction and localization) are more common at the beginning of a trajectory, while others (like editing and submission) become more frequent later in the trajectory, illustrating the phases of problem solving.

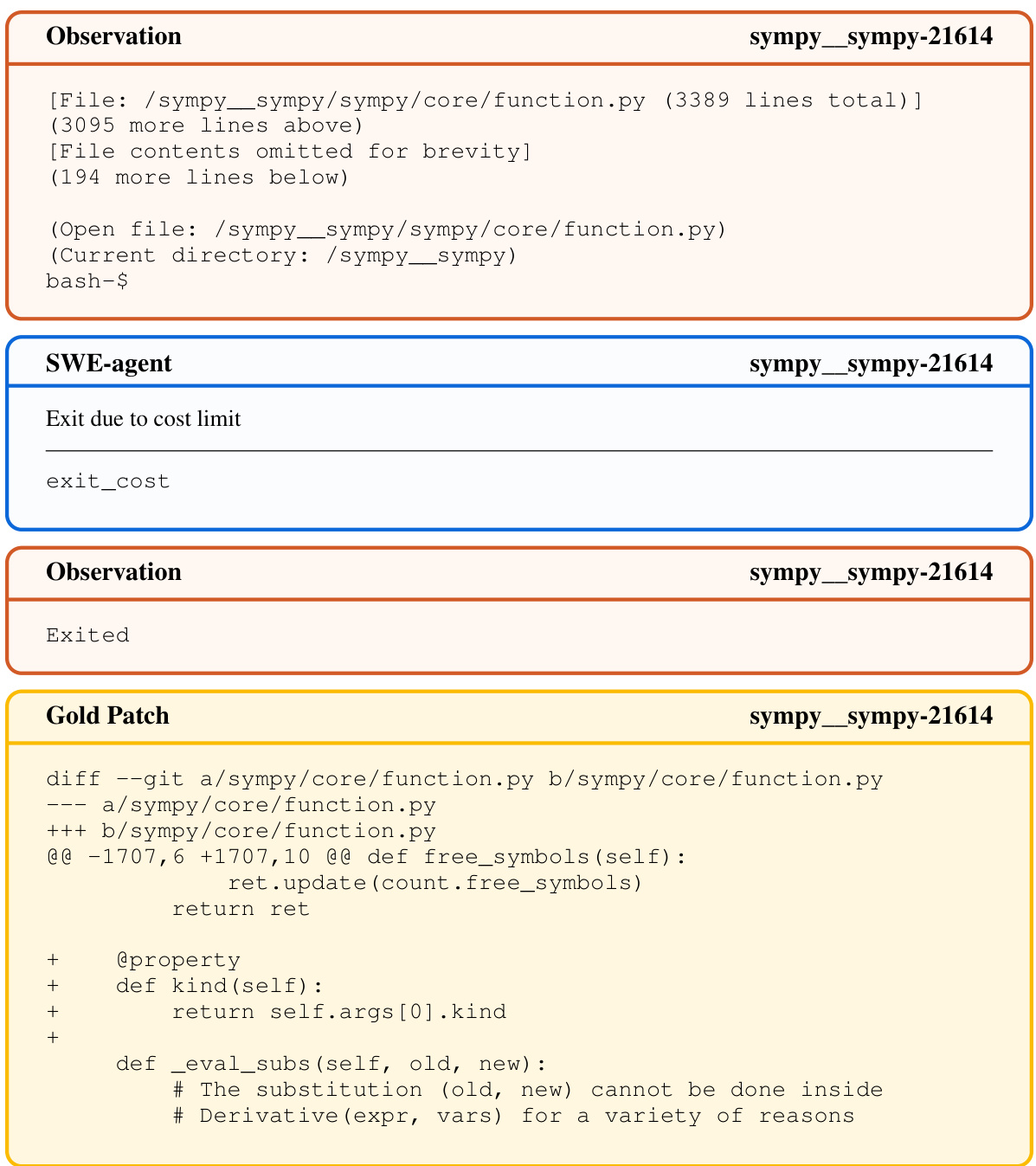

This figure shows the distribution of actions across different turns of a trajectory. The x-axis represents the turn number, and the y-axis represents the density of each action. The actions are color-coded for easy identification. The figure highlights the prevalence of certain actions in different stages of the problem-solving process. The

exit_costcategory represents instances where the token budget was exhausted before the agent could complete the task.

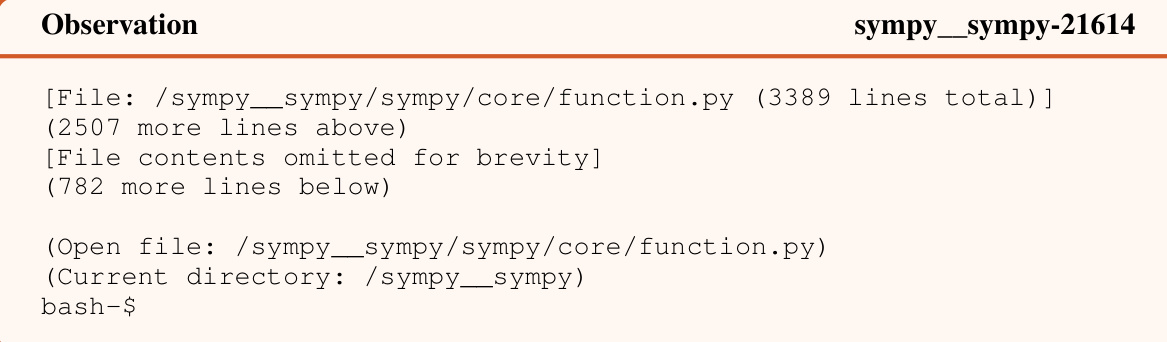

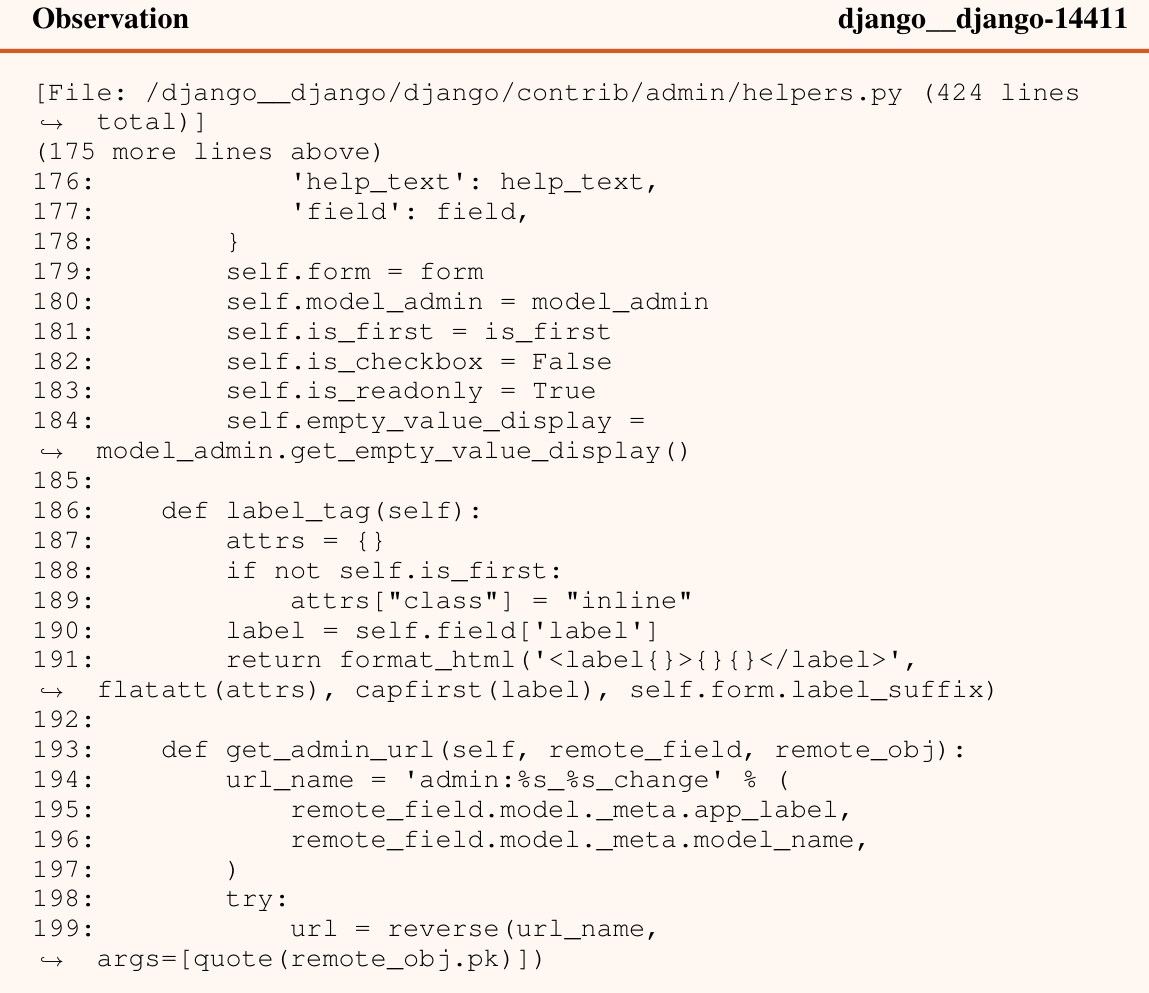

This figure shows the user interface elements of the SWE-agent. It highlights the File Viewer, which presents a limited window of the open file’s content, and three different search commands:

find_file,search_dir, andsearch_file. These commands allow the agent to locate files or specific lines within files, aiding navigation and information retrieval within the codebase. The figure is accompanied by examples of how the commands’ outputs are formatted and displayed to the agent.

This figure shows examples of the File Viewer and Search components in SWE-agent. The File Viewer displays code from an open file with line numbers and context. The search commands (find_file, search_dir, search_file) allow an agent to locate specific files or strings in the repository, with the results displayed concisely.

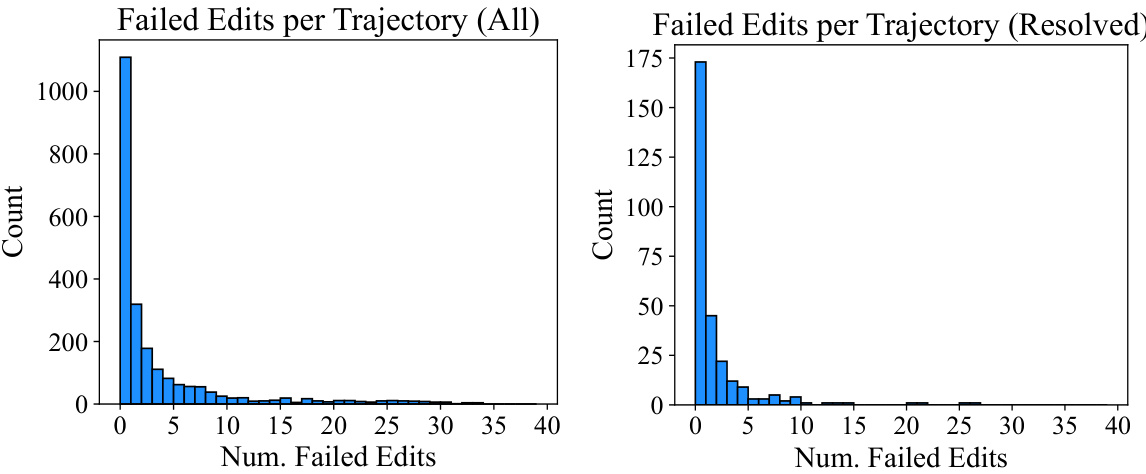

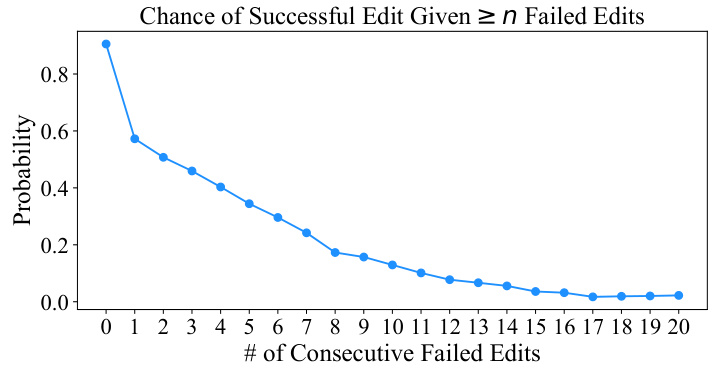

This figure shows the probability of a successful edit given a certain number of consecutive failed edits. The x-axis represents the number of consecutive failed edits, and the y-axis represents the probability of a successful edit following those failed edits. The graph shows a clear trend: the probability of a successful edit decreases as the number of consecutive failed edits increases. This illustrates that after several failed edits, the model has a much lower chance of recovering and performing a successful edit.

The figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture, showing how a Language Model (LM) agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction between the LM agent and the computer’s environment (terminal, file system). The ACI provides the LM agent with LM-friendly commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and a structured format for receiving feedback from the computer’s actions, enabling more effective interaction and improved performance in complex tasks such as software engineering.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom interface called an ACI (Agent-Computer Interface). The ACI defines the commands that the LM agent can use to interact with the computer and the format of the feedback that the computer sends back to the agent. The figure visually depicts the flow of information between the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer. The LM agent receives feedback, generates commands, and interacts with the computer’s file system. This custom design of the ACI enables the LM agent to effectively interact with the computer and solve software engineering tasks.

The figure illustrates the architecture of SWE-agent, showing how a Language Model (LM) agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an intermediary, translating LM commands into actions that the computer can understand, and providing feedback to the LM in a format that it can process. The diagram shows the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer components, with arrows indicating the flow of commands and feedback. This architecture allows the LM agent to effectively interact with the computer and solve software engineering tasks.

This figure shows examples of the File Viewer and Search components of the SWE-agent interface. The File Viewer displays file content with line numbers, allowing for easy navigation within a file. The Search functionality includes commands to search for files, search within files for specific terms, and to search within directories for specific terms. The figure highlights how the ACI provides concise information and feedback, which enhances an LM agent’s ability to perform software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the user interface design of the file viewer and search components within SWE-agent. The file viewer provides a way to interactively view and navigate the contents of code files. The search components allow the agent to efficiently search for relevant files and strings within the codebase using commands like

find_file,search_file, andsearch_dir. The example trajectories are from the pvlib_pvlib-python-1603 task instance, showcasing the agent’s interaction with these interface elements. The use of color coding and clear formatting aims to improve the clarity and efficiency of the information presented to the LM agent.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture, showing how a large language model (LM) interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an intermediary, translating the LM’s commands into actions that the computer can understand, and feeding back the computer’s responses to the LM in a format that is easy for it to process. This design is intended to improve the LM’s ability to perform complex software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-built agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI is designed to be more LM-friendly than standard interfaces (like a command line), providing simplified commands and structured feedback. This improves the agent’s ability to perform software engineering tasks. The diagram illustrates the communication flow between the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer’s file system and terminal.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands the agent can use to interact with the computer (e.g., navigating the file system, searching files, viewing files, editing files) and the format in which the computer provides feedback to the agent. This design is crucial for the agent’s success and allows the agent to solve software engineering tasks efficiently and reliably by filtering out distracting and unnecessary information.

This figure demonstrates the architecture of SWE-agent, showing how a large language model (LM) interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI is designed to simplify the interaction for the LM by providing a set of LM-friendly commands for common software engineering tasks (e.g., navigating a repository, searching and viewing files, editing code). The ACI also controls the format of the feedback from the computer, making it easier for the LM to understand and use in subsequent actions. The architecture consists of three main components: a LM agent, which sends commands through the ACI; the ACI itself, which acts as an abstraction layer simplifying interaction between the LM and the computer; and the computer environment, including the file system and the terminal, from which the agent receives feedback.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent, which uses a Language Model (LM) to interact with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI is designed to make it easier for the LM agent to use the computer to perform software engineering tasks. The ACI provides the LM agent with a set of simple commands that can be used to view, search, and edit files, as well as to navigate a repository and execute tests. The ACI also provides the LM agent with a way to receive feedback from the computer. The figure shows how the LM agent uses the ACI to interact with the computer in order to solve a software engineering task. The figure shows the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer, and highlights the flow of information between them.

This figure shows a diagram of the SWE-agent system architecture. The Language Model (LM) agent interacts with a computer indirectly through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an intermediary, translating the LM’s requests into commands understandable by the computer and vice-versa. The commands available to the agent via the ACI, as well as the format of the feedback the computer sends back to the agent, are crucial elements of the system design.

This figure shows a schematic of the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions understandable by the computer and formats computer responses into a format suitable for the LM. The ACI simplifies complex software engineering tasks into a series of smaller, more manageable actions. The figure highlights the key components of the ACI, such as the commands available to the agent (navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and the feedback mechanisms from the computer (LM-friendly environment feedback).

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly via an agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction by providing the LM agent with high-level commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and receiving structured feedback from the computer’s actions, such as terminal outputs and file system changes. This design makes it easier for the LM agent to perform complex software engineering tasks, as compared to interacting directly with a low-level interface like the Linux shell.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly through a custom-designed abstraction layer called an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands the LM can use to interact with the computer (e.g., file navigation, editing) and how the computer’s responses are formatted and relayed back to the agent. This design enhances the LM agent’s ability to work with computer systems to achieve specific software engineering tasks.

The figure shows a high-level architecture of SWE-agent, where an LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing a set of LM-friendly commands for interacting with the computer’s file system and terminal, and also provides structured feedback to the LM. This allows the LM agent to perform complex software engineering tasks more effectively. The example shows a simple file structure with a

README.rstandexamplesdirectory within asklearndirectory.

This figure shows a diagram illustrating the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer via a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions the computer can understand and provides structured feedback to the agent in a format it can easily process. The ACI acts as an abstraction layer that simplifies the interaction between the LM agent and the complex computer environment, enabling the agent to solve complex software engineering tasks more effectively.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. SWE-agent uses a language model (LM) to interact with a computer. The interaction is mediated by a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions that the computer can understand, and it formats the computer’s responses in a way that the LM can easily process. The ACI includes commands for navigating a repository (searching and viewing files), editing files, and executing tests.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction between the LM agent and the complex computer environment. The ACI defines a set of LM-friendly commands for interacting with the computer (e.g., navigating the repository, searching files, viewing files, editing lines) and specifies the format of the feedback from the computer to the LM agent. This abstraction layer allows the LM agent to efficiently and reliably interact with the computer to solve complex tasks, improving its overall performance.

This figure shows a high-level overview of the SWE-agent architecture. The Language Model (LM) agent interacts with the computer via a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI translates the LM’s commands into actions that can be executed on the computer, and it processes the feedback from the computer into a format that the LM can understand. The ACI also handles the navigation of the file system and the execution of other programs.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent system, which consists of a Language Model (LM) agent interacting with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction between the LM agent and the computer’s functionalities (terminal, file system). It defines the commands the LM can use to interact with the computer and specifies the format of feedback received from the computer.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI handles the communication between the LM and the computer, providing LM-friendly commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and a formatted environment feedback to the agent. The computer’s response (terminal and file system) is also displayed. This highlights the key innovation of the paper: using a custom ACI to facilitate effective interaction between LMs and computers for complex software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. The Language Model (LM) agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI translates high-level commands from the LM agent into low-level system commands, and translates low-level feedback from the computer system back into the LM-friendly format. This allows the LM agent to interact with and control the computer autonomously, unlike traditional LM agents that operate through existing applications such as a terminal or a text editor.

This figure shows a diagram of the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions on the computer (e.g., navigating a repository, editing files), and provides feedback to the LM in a format designed for efficient processing. The ACI is shown as a layer between the LM agent and the computer’s filesystem and terminal.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed interface called ACI. The ACI facilitates interaction by translating LM commands into actions understandable by the computer and transforming computer responses into feedback that is usable by the LM agent. This interaction loop allows the agent to accomplish complex tasks by breaking them down into smaller, manageable steps. The figure highlights the key components involved, including the LM agent, the ACI, the computer (including its terminal and file system), and the flow of commands and feedback between them.

This figure shows a high-level overview of the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer, not directly through a shell, but via a custom abstraction layer called an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands that the LM can use to interact with the computer and the format of the feedback the computer provides to the LM. The diagram visually represents the information flow between the LM agent, ACI, and the computer system (filesystem, terminal).

The figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer using a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI is represented by the two boxes showing the LM-friendly commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) that the agent can use to interact with the computer, and the format of the feedback from the computer. The feedback includes the terminal, file system, and an example file structure. The ACI acts as an intermediary, abstracting away the complexities of the underlying computer system and providing a simplified interface for the LM agent. This simplified interface is key to improving the LM agent’s performance in software engineering tasks.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent system, which consists of a language model (LM) agent interacting with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction between the LM agent and the complex commands and feedback of the computer’s environment. It shows the LM agent sending LM-friendly commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) to the ACI, which translates them into appropriate commands for the computer’s terminal and filesystem. The ACI then relays the computer’s response back to the LM agent in a friendly format.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI translates between LM-friendly commands and the computer’s response. The ACI’s design is crucial to the LM agent’s success. The feedback loop shown is iterative, with the agent repeatedly making requests based on the computer’s responses.

This figure shows a schematic of the SWE-agent system. An LM agent interacts with a computer via a custom-designed Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions the computer can understand, and translates computer responses back into a format that the LM can easily process. This design allows the LM agent to autonomously perform more complex software engineering tasks. The figure highlights the key components: the LM Agent, the ACI, the computer, and its terminal and file system.

This figure illustrates the architecture of SWE-agent, which consists of a language model (LM) agent interacting with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction between the LM and the computer’s functionalities (terminal, file system). The ACI defines the commands the LM agent can use to interact with the computer and specifies the format of the feedback the computer provides to the LM. This simplified interface is designed to improve the LM agent’s ability to perform software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI provides the agent with a simplified set of commands for interacting with the computer’s file system, such as navigating the repository, viewing and editing files, and executing tests. The ACI also controls the format of the feedback that the computer provides to the agent, which includes both commands and environmental responses.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly, via a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer that simplifies the interaction between the LM agent and the computer’s file system and terminal, thereby enhancing the agent’s ability to perform complex software engineering tasks. The ACI defines the commands the LM agent can use (e.g., navigate repository, search files, view files, edit lines) and also specifies how feedback from the computer is formatted to make it easier for the LM agent to understand and process.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI is a layer of abstraction that simplifies the interaction between the LM agent and the underlying computer system. It provides the LM agent with high-level commands to interact with the computer’s file system, execute programs, and receive feedback. This is in contrast to directly interacting with a complex system like a Linux shell, which is challenging for LM agents. The ACI simplifies this complexity and improves the agent’s ability to perform software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing a set of LM-friendly commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and a structured format for the feedback from the computer. This design enhances the agent’s ability to use the computer effectively for software engineering tasks.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer, not directly through the operating system, but via a custom abstraction layer called an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands that the LM can use to interact with the computer (e.g., navigate a repository, search files, view files, edit lines) and the format of the feedback the computer provides to the agent.

This figure shows the SWE-agent system architecture, illustrating how a large language model (LLM) agent interacts with a computer. The interaction is mediated by a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction process by providing a set of LLM-friendly commands for navigating repositories, viewing and editing files, and executing programs. The computer’s responses are also formatted in a way that’s easy for the LLM to understand and process. This design is in contrast to the typical interaction of LLMs with operating systems or shells, which are often much more complex and difficult for LLMs to use effectively.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI is designed to make it easier for the LM agent to interact with the computer, including commands the agent can use and the format of the feedback received from the computer. The ACI simplifies complex interactions and provides guardrails to prevent common errors, improving the performance of the LM agent.

The figure illustrates the SWE-agent system’s architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction for the LM. It provides the agent with LM-friendly commands (repo navigation, file search/view/edit) and receives LM-friendly feedback from the computer (terminal, file system).

This figure shows a diagram of the SWE-agent system architecture. The large language model (LLM) agent interacts with the computer via a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, providing the LLM with simplified commands to interact with the computer’s file system and execute code. The computer sends feedback back to the LLM through the ACI in a structured format. This design is intended to make it easier for LLMs to effectively perform software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an intermediary layer, translating the LM’s commands into actions the computer can understand, and then relaying the results of these actions back to the LM in a way that’s easy for the LM to parse. The figure highlights the key components: the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer’s terminal and file system. The ACI’s role is to simplify interactions for the LM by abstracting away the low-level details of interacting with the computer.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly through a custom-designed abstraction layer called the Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing a set of LM-friendly commands for interacting with the computer’s file system and terminal, as well as a structured feedback mechanism. This design improves the reliability and efficiency of LM agents in performing complex tasks like software engineering, which is the focus of the paper.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. The language model (LM) agent interacts with the computer via a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI translates LM commands into actions the computer can understand (e.g., navigating a repository, viewing files, editing files, executing tests), and translates the computer’s responses back into a format the LM can understand. This interface is crucial for enabling the LM agent to successfully perform complex software engineering tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying the interaction for the LM agent by providing LM-friendly commands (e.g., Navigate repo, Search files, View files, Edit lines) and structured feedback from the computer. The ACI enhances the agent’s ability to work with the computer’s file system and terminal.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. SWE-agent uses a Language Model (LM) agent to interact with a computer. The interaction is mediated by an Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands the LM agent can use to interact with the computer, and the format of the feedback from the computer to the LM agent. This interface is crucial to the system’s functionality, as it allows the LM agent to perform complex software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the overall architecture of SWE-agent, which consists of an LM Agent interacting with a computer through a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer between the LM agent and the computer, providing the LM agent with LM-friendly commands to navigate a repository, search and view files, edit code, and execute tests. The ACI also manages the format of the feedback sent back to the LM agent, which includes both the commands used and the responses from the computer. This allows the LM agent to more effectively interact with the computer and perform software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent, where a large language model (LLM) interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI provides a set of simplified commands to the LLM for interacting with the computer’s file system, and returns formatted feedback to the LLM, showing the effects of the commands. This design helps the LLM to solve complex tasks that require interaction with the computer more effectively. The figure includes a visual representation showing the different components such as the LM agent, ACI, computer, terminal, and file system.

This figure demonstrates the architecture of SWE-agent, which uses a language model (LM) to interact with a computer. The interaction is mediated by a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing a set of LM-friendly commands to navigate the file system, view and edit files, and receive feedback from the computer. This design allows the LM agent to efficiently perform complex software engineering tasks.

This figure shows the architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing a set of LM-friendly commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and a structured format for receiving feedback from the computer. This allows the agent to perform software engineering tasks more effectively.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture, showing how a language model (LM) agent interacts with a computer through a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an intermediary, translating LM commands into actions the computer can understand, and feeding back computer responses in a format the LM can process. This enables the LM agent to perform complex software engineering tasks autonomously.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer via a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies interaction by providing LM-friendly commands for common software engineering tasks (e.g., navigating a repository, searching/viewing files, editing code). The ACI also structures feedback from the computer into a format easily processed by the LM. This design improves the LM’s ability to perform complex software engineering tasks compared to interacting directly with the computer’s operating system.

This figure shows a high-level overview of the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer not directly, but through a custom-designed interface called an ACI (Agent-Computer Interface). The ACI translates between LM-friendly commands and the computer’s operating system. The figure highlights the flow of commands from the agent to the computer and the feedback received by the agent, illustrating the interactive nature of the system.

The figure shows a diagram of the SWE-agent system. An LM agent interacts with a computer using a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI is depicted as a box between the LM agent and the computer. Arrows indicate that LM-friendly commands are sent from the agent to the computer and LM-friendly environment feedback is returned from the computer to the agent. The computer’s components, including the terminal and the file system, are also shown. A specific example of a file in the file system is highlighted (README.rst).

This figure shows the SWE-agent system architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer via a custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI). The ACI defines the commands the agent can use to interact with the computer (e.g., navigate the file system, edit files, run code) and the format of the feedback the computer provides to the agent. The diagram highlights the key components involved in the interaction: the LM agent, the ACI, and the computer’s file system and terminal.

This figure shows the overall architecture of SWE-agent. An LM agent interacts with a computer via a custom-designed agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI simplifies the interaction by providing LM-friendly commands for interacting with the computer’s file system and terminal, and presenting feedback in a structured format that the LM can easily understand. This is in contrast to the more granular and complex interfaces typically used by human users.

This figure illustrates the SWE-agent architecture. An LM agent interacts with a computer indirectly through a custom agent-computer interface (ACI). The ACI acts as an abstraction layer, simplifying interaction by providing the agent with high-level commands (e.g., navigate repo, search files, view files, edit lines) and structured feedback from the computer’s actions. This design improves the agent’s ability to perform complex software engineering tasks compared to direct interaction with a shell or similar environments.

More on tables

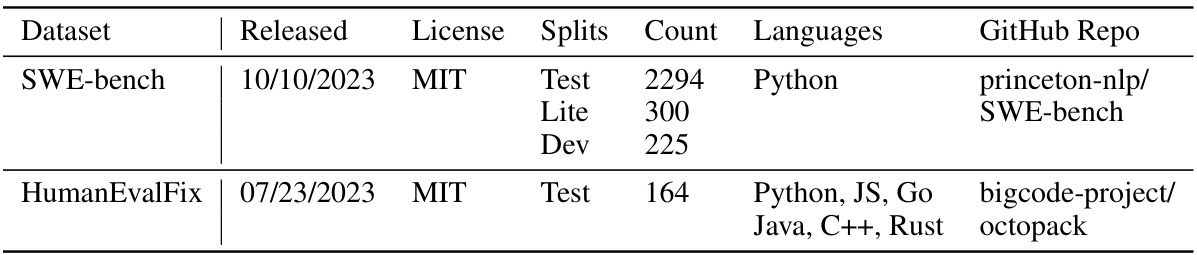

This table presents the pass@1 scores achieved by different language models on the HumanEvalFix benchmark. HumanEvalFix is a code debugging benchmark focusing on short-form code fixes. The pass@1 metric indicates the percentage of test cases where the model’s generated code passes all tests after the fixes are applied. The table shows that SWE-agent, using GPT-4 Turbo, significantly outperforms other models, achieving a pass@1 rate of 87.7% across Python, JavaScript, and Java tasks.

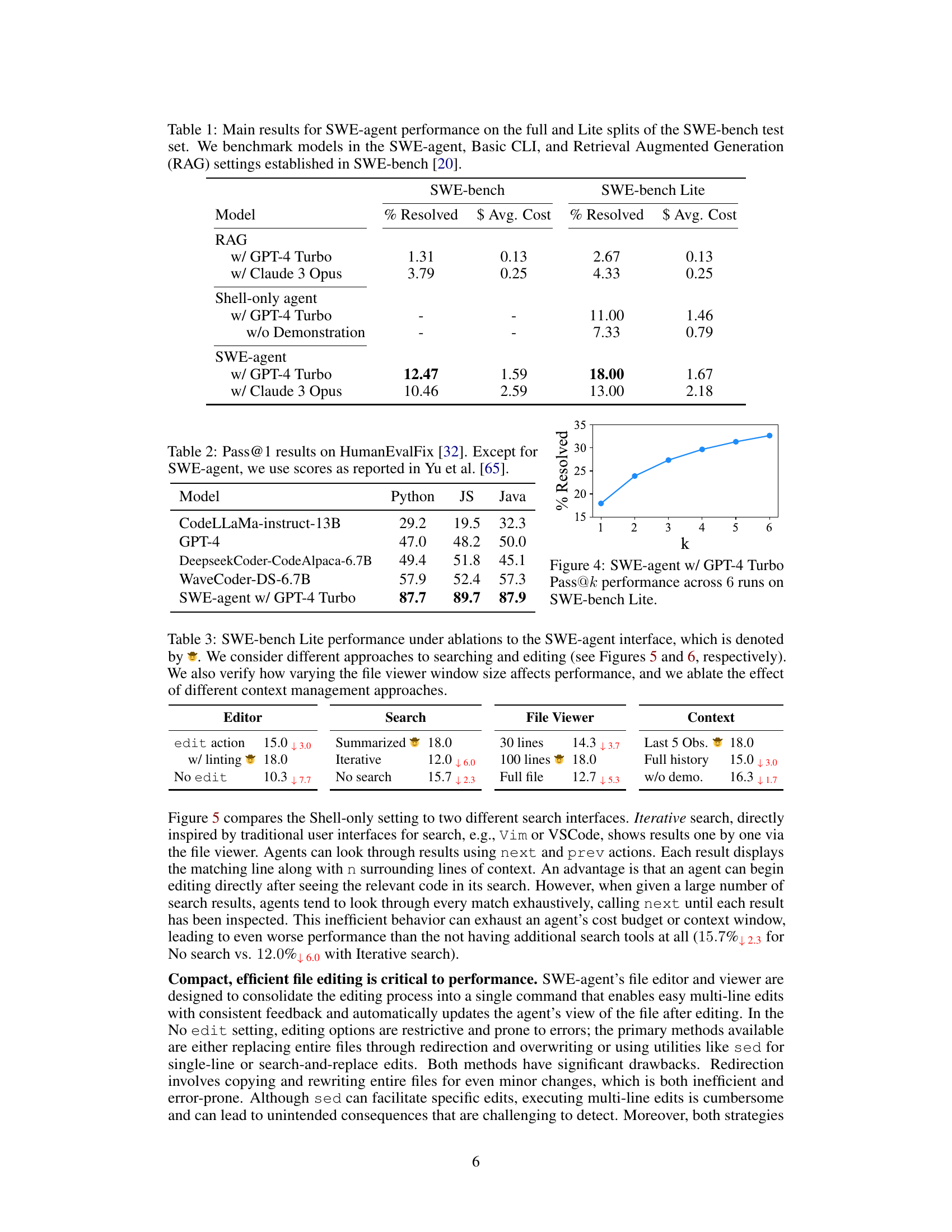

This table presents the results of ablation studies performed on the SWE-agent system, which involved modifying different aspects of the agent-computer interface (ACI) and evaluating its impact on performance. The ablations include modifications to the search interface (summarized, iterative, no search), the file editing interface (edit action w/ linting, no edit), the file viewer (30 lines, 100 lines, full file), and the context management (last 5 obs, full history, w/o demo). The results show the percentage of instances solved under each configuration, highlighting the effect of design choices on the agent’s performance.

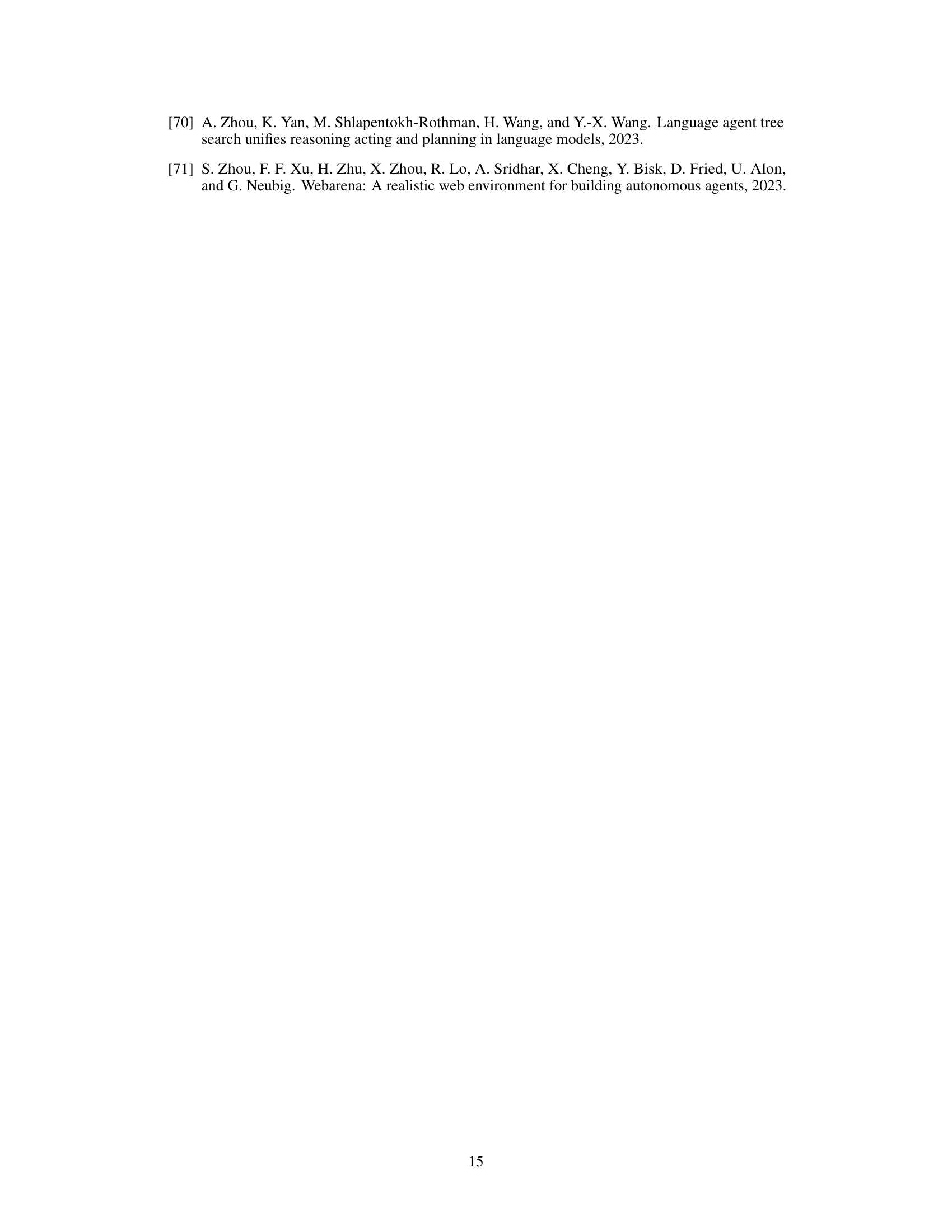

This table lists the commands available to the SWE-agent. It categorizes commands into four groups: File Viewer, Search tools, File editing, and Task. For each command, it provides the command syntax, specifying required and optional arguments, and a description of the command’s function and documentation provided to the language model.

This table presents the results of a hyperparameter sweep conducted on a subset of the SWE-bench development dataset. The sweep involved varying three hyperparameters: temperature, window size, and history length. The table shows the resulting mean % Resolved rate (percentage of instances solved successfully) for each combination of hyperparameter settings across five samples. This helps identify the best performing hyperparameter combination for the model.

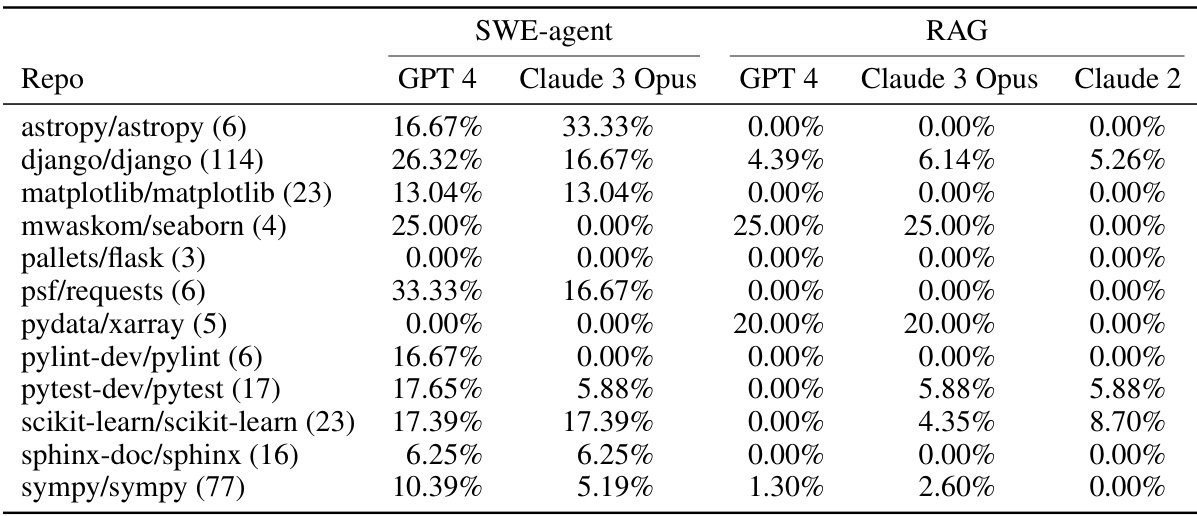

This table shows the performance of SWE-agent and RAG baselines on the SWE-bench Lite dataset, broken down by repository. It shows the percentage of instances successfully resolved for each model and each repository. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of instances from each repository in the dataset. This allows for comparison of model performance across different repositories and provides insight into which repositories are more challenging for the models.

This table shows the success rate of SWE-agent and RAG baselines across 12 different repositories included in SWE-bench Lite. It demonstrates SWE-agent’s improved performance compared to the baselines, especially in repositories where baselines had low success rates. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of instances from each repository.

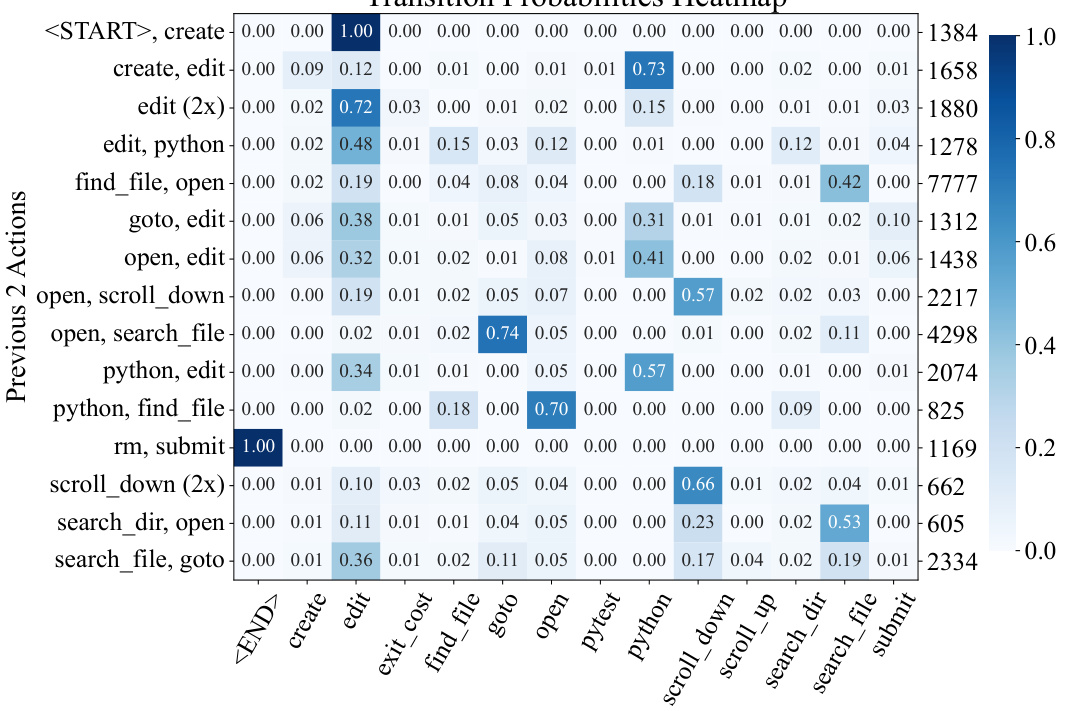

This table shows the frequency of action patterns within resolved trajectories of SWE-agent with GPT-4. Each row shows a sequence of actions (pattern) and its frequency across several consecutive turns. The table also categorizes each pattern to describe the general step in the problem-solving process: Reproduction (reproducing the problem), Localization (File/Line) (identifying the relevant file or code lines), Editing (making changes to the code), and Submission (submitting the solution).

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent model’s performance on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance of SWE-agent against two baseline models: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and Shell-only. The results are shown for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The metrics used to evaluate performance are: the percentage of instances successfully resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost). The table highlights the significant improvement in performance achieved by SWE-agent, particularly when using GPT-4 Turbo as the base language model.

This table shows the percentage of successfully resolved tasks for each of the 12 repositories in the SWE-bench Lite dataset. The performance is broken down by model (SWE-agent with GPT-4 Turbo and SWE-agent with Claude 3 Opus) and includes a comparison to a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) baseline and Claude 2. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of tasks from each repository in the Lite dataset.

This table compares the performance of SWE-agent with different language models on the SWE-bench dataset. It shows the percentage of resolved instances, which represents the successful resolution of software engineering tasks, and the average cost of each run. The table also includes baseline results from RAG and Shell-only agent to showcase the improvement achieved by SWE-agent.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent model’s performance on two versions of the SWE-bench dataset: the full dataset and a smaller ‘Lite’ version. It compares SWE-agent’s performance against two baseline models: a non-interactive retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) model and a model using only the default Linux shell. The table shows the percentage of tasks successfully solved (% Resolved) and the average cost in USD ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and dataset. The results highlight the significant improvement achieved by SWE-agent due to the custom ACI compared to the baselines.

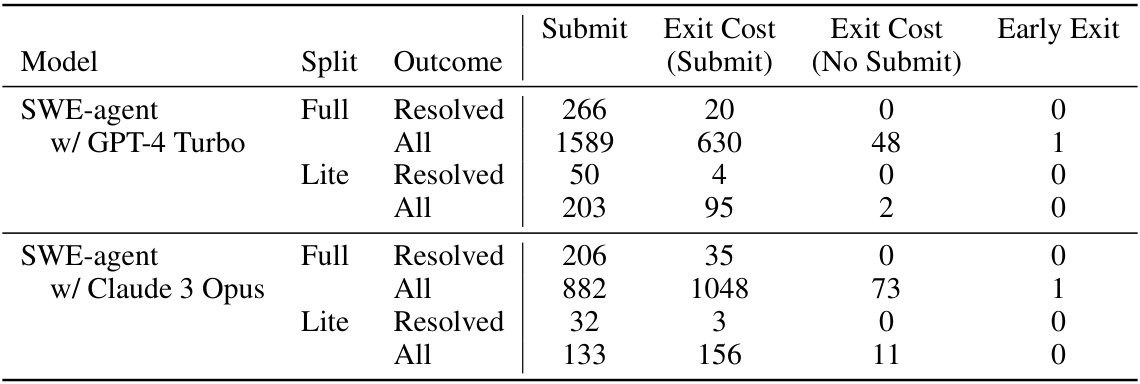

This table shows the number of task instances that ended in each of four ways. These ways represent how the task episode concluded: by a successful submission, by exceeding the cost budget (and submitting or not submitting changes), or by prematurely terminating the run due to too many invalid responses. The data is split between fully resolved trajectories and all trajectories. The numbers are broken down by model (SWE-agent w/ GPT-4 Turbo and SWE-agent w/ Claude 3 Opus) and by dataset split (Full and Lite).

This table presents the performance comparison of SWE-agent with different language models on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares SWE-agent’s performance against two baseline models: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and Shell-only agent. The table shows the percentage of resolved issues (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and setting on both the full SWE-bench and the smaller SWE-bench Lite dataset. It highlights SWE-agent’s superior performance and improved resolve rate, especially when compared to the RAG baseline.

This table presents the performance of different models on the SWE-bench dataset, comparing three different settings: SWE-agent, Basic CLI (Shell-only), and RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation). It shows the percentage of tasks successfully resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The results highlight the improved performance of SWE-agent, particularly when using GPT-4 Turbo, compared to the baseline methods.

This table presents the performance comparison of different models and settings on SWE-bench. It includes SWE-agent with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus, Shell-only agent with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus, and RAG baselines with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus. The metrics used for comparison are % Resolved and average cost. The table provides a detailed breakdown of the performance of each method on both the full SWE-bench test set and a subset of 300 instances from the SWE-bench test set known as SWE-bench Lite. This allows for comparison of the performance in the complete and a representative subset of the benchmark.

This table compares the performance of SWE-agent with different language models (GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) against two baseline methods: Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) and a Shell-only agent. The performance is measured by the percentage of successfully resolved instances (% Resolved) on both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite). The table also shows the average cost ($) for each method. The results demonstrate that SWE-agent significantly outperforms the baseline methods, achieving state-of-the-art results on both datasets.

This table presents the performance of SWE-agent on the SWE-bench dataset, comparing it to two baselines: RAG and Shell-only. The results show the percentage of instances resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. It highlights SWE-agent’s superior performance, particularly when using GPT-4 Turbo as the underlying language model.

This table presents the performance of SWE-agent, along with baselines, on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the percentage of resolved issues (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite) across different model and interface settings (SWE-agent, Basic CLI, and RAG). This helps demonstrate the impact of the custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI) developed for SWE-agent.

This table shows the performance of different models on the SWE-bench dataset. The models are tested using three different settings: SWE-agent, Basic CLI, and RAG. The table shows the percentage of instances that were successfully resolved and the average cost for each setting. SWE-agent shows significantly better results compared to other settings.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments conducted on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance (% Resolved) and average cost of SWE-agent using two different large language models (LLMs), GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus, against two baseline approaches: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a Shell-only agent. The results are shown for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite) focusing on functional bug fixes. The table highlights SWE-agent’s significantly improved performance compared to previous state-of-the-art approaches, particularly using the GPT-4 Turbo LLM.

This table compares the performance of SWE-agent with different language models on the SWE-bench dataset. It shows the percentage of resolved issues (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The table also includes results for two baseline approaches: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a Shell-only agent, which uses only the default Linux shell. The comparison highlights the improvement achieved by SWE-agent’s custom agent-computer interface (ACI) in solving software engineering tasks.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments. It compares the performance of SWE-agent (using GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) against two baselines: a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) approach and a system that only uses the Linux shell. The performance is measured by the percentage of successfully resolved instances in the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite). The table also includes the average cost (in USD) for each system.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments. It compares the performance of SWE-agent with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus against two baseline models: a retrieval augmented generation (RAG) model and a shell-only agent. The comparison is made on two subsets of the SWE-bench dataset: the full test set and a smaller ‘Lite’ subset. The table shows the percentage of instances successfully resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost in USD for each setting.

This table presents the performance of SWE-agent, compared to two baselines (RAG and Shell-only), on the SWE-bench dataset. The performance is measured by the percentage of instances where all tests passed after applying the generated patch (% Resolved) and the average API inference cost. The table shows results for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite) and highlights the performance improvements achieved by SWE-agent’s custom ACI.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent performance evaluation on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the percentage of resolved issues and the average cost for three different settings: SWE-agent (with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus), Basic CLI (Shell-only agent with GPT-4 Turbo and without demonstration), and Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus. The comparison shows SWE-agent’s significant improvement in problem-solving capability compared to the other methods, especially in the SWE-bench Lite subset.

This table presents the results of the SWE-agent model on the SWE-bench dataset, comparing its performance to two baseline models: RAG and Shell-only. The table shows the percentage of tasks successfully solved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset known as SWE-bench Lite. The results highlight the improvement in performance achieved by SWE-agent, particularly when using the GPT-4 Turbo language model.

This table shows the performance of different models on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares three different settings: SWE-agent, Basic CLI (command-line interface only), and RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation). The performance is measured by the percentage of tasks successfully solved (% Resolved) and the average cost (in USD). It breaks down results for the full SWE-bench and the smaller SWE-bench Lite subsets.

This table presents the results of the SWE-agent model’s performance on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance of SWE-agent (using both GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus language models) against two baselines: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a Shell-only agent. The table shows the percentage of resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite). It highlights the significant improvement in performance achieved by SWE-agent using its custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI) compared to the baselines.

This table presents the performance of different models on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance of SWE-agent (with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) against two baselines: a retrieval augmented generation (RAG) approach and a shell-only agent. The results are shown for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The metrics used are the percentage of successfully resolved issues and the average cost.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent model’s performance on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance of SWE-agent using GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus against two baseline models: a non-interactive RAG baseline and a shell-only agent. The results are shown for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The table includes the percentage of resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and setting.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments. It compares the performance of SWE-agent with different Language Models (LMs) on the full and Lite splits of the SWE-bench dataset. It also includes results from two baseline methods: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a shell-only agent. The table shows the percentage of instances successfully resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and setting. The results demonstrate the superior performance of SWE-agent on both splits compared to the baselines, highlighting the impact of the agent-computer interface.

This table presents the results of the SWE-agent model on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance of SWE-agent with different language models (GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) against two baseline models: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a Shell-only agent. The table shows the percentage of successfully resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The results highlight the improved performance of SWE-agent with an LM-friendly ACI compared to the baseline models.

This table presents the performance comparison of different models on the SWE-bench dataset. It shows the percentage of successfully resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model across two settings: the full SWE-bench test set and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. Three types of model setups are compared: Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), a basic command line interface (Basic CLI), and the proposed SWE-agent approach. Results are given for GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus Language Models.

This table shows the performance of different models (SWE-agent with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus, Shell-only agent with GPT-4 Turbo, and RAG with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) on the SWE-bench dataset. The performance is measured by the percentage of instances resolved and the average cost. The table compares the performance of SWE-agent to two baselines: RAG and Shell-only. The SWE-bench dataset contains 2,294 instances for the full test set and 300 instances for the SWE-bench Lite test set.

This table presents the performance of different models on two versions of the SWE-bench dataset: the full dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The models are evaluated using three different approaches: SWE-agent (the proposed method), Basic CLI (interacting directly with the Linux shell), and Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG; a non-interactive method). The table shows the percentage of tasks successfully resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and approach on both datasets. This table highlights the significant improvement in performance achieved by SWE-agent compared to the baseline methods.

This table compares the performance of SWE-agent with different language models on the SWE-bench dataset. It contrasts SWE-agent’s performance against two baselines: a non-interactive retrieval augmented generation (RAG) method and an agent interacting only with the basic command line interface (CLI). The table shows the percentage of successfully resolved issues (’% Resolved’) and the average cost in USD (’$ Avg. Cost’) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. This highlights the impact of the agent-computer interface (ACI) on the performance of language models in complex software engineering tasks.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments on the SWE-bench dataset, comparing its performance to two baselines: RAG and Shell-only. It shows the percentage of successfully resolved issues (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The results are broken down by model (GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) and experimental setup (SWE-agent, Basic CLI, RAG).

This table presents the performance of SWE-agent on the SWE-bench dataset, broken down by different settings (SWE-agent, Basic CLI, RAG) and models (GPT-4 Turbo, Claude 3 Opus). The main metric is the percentage of instances resolved successfully (% Resolved) and the average cost of API calls ($ Avg. Cost). It compares the performance of SWE-agent with different baselines on both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite). The table highlights SWE-agent’s significantly improved performance compared to the baselines.

This table shows the performance of SWE-agent and two baseline models (RAG and Shell-only agent) on the SWE-bench dataset. The results are broken down by dataset split (full SWE-bench and SWE-bench Lite) and model (GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus). For each model and split, the table shows the percentage of instances successfully resolved and the average cost (in USD) per instance.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments on the SWE-bench dataset. It compares the performance of SWE-agent with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus against two baseline methods: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a shell-only agent. The results are shown for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The table shows the percentage of instances successfully resolved (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and setting.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent’s performance on the SWE-bench dataset, broken down by the full and Lite splits. It compares SWE-agent’s performance against two baselines: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and a shell-only agent. The table shows the percentage of resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and setting.

This table shows the performance comparison of different models (SWE-agent with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus, Shell-only agent with GPT-4 Turbo, and RAG with GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) on two splits of the SWE-bench dataset (full and Lite). For each model and dataset split, the table shows the percentage of resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost in USD ($ Avg. Cost). The results demonstrate that SWE-agent significantly outperforms the baseline methods (Shell-only and RAG) in terms of the percentage of resolved instances, although at a higher cost.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments, comparing its performance on the SWE-bench dataset against two baselines: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and Shell-only. It shows the percentage of resolved instances (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost) for each model and setting on both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset called SWE-bench Lite. The results highlight the improved performance of SWE-agent, particularly when using GPT-4 Turbo, demonstrating the effectiveness of the custom agent-computer interface (ACI) in enhancing language model agents’ ability to solve software engineering tasks.

This table shows the performance comparison of different models on the SWE-bench dataset. The dataset is split into ‘full’ and ‘Lite’ versions. The models are evaluated under three settings: SWE-agent, basic CLI, and RAG. For each model and setting, the table shows the percentage of resolved issues (% Resolved) and the average cost ($ Avg. Cost). The results highlight SWE-agent’s superior performance compared to the other settings.

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent experiments on the SWE-bench dataset, comparing its performance against two baseline models: RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and Shell-only. It shows the percentage of instances successfully resolved and the average API cost for both the full SWE-bench dataset and a smaller subset (SWE-bench Lite). The results are broken down by model (GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus) and setting (SWE-agent, Basic CLI, and RAG).

This table presents the main results of the SWE-agent model’s performance on the SWE-bench dataset, broken down by the full and Lite splits. It compares SWE-agent’s performance against two baselines: RAG and Shell-only agent. The metrics used are % Resolved and Average Cost. The table showcases the performance of SWE-agent using two different large language models, GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 Opus, highlighting the improvement achieved by the custom Agent-Computer Interface (ACI).

Full paper#