TL;DR#

Autonomous driving relies heavily on accurate lane topology understanding for safe navigation. Existing methods often prioritize perception over reasoning, using simple neural networks that struggle with lane detection inaccuracies and endpoint variations. This leads to unreliable and incomplete lane topology estimations.

TopoLogic addresses these issues with a novel, interpretable approach. It combines geometric distance calculations between lanes, which are robust to endpoint shifts, with a semantic similarity measure based on lane queries. This dual-space approach delivers a more comprehensive understanding of lane connectivity, outperforming existing models significantly on the OpenLane-V2 dataset. The method is also easily integrated into existing systems without extensive retraining, offering a practical solution for improving autonomous driving technology.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves lane topology reasoning, a crucial task in autonomous driving. Its interpretable method and robust performance on a benchmark dataset make it highly relevant to current research trends and open avenues for enhancing autonomous vehicle navigation systems.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the impact of post-processing on lane topology reasoning using TopoNet. Panel (a) shows the ground truth, highlighting the accurate overlap of connected lane endpoints. Panel (b) demonstrates a prediction from TopoNet without post-processing, where endpoints do not overlap. Panel (c) shows the prediction from TopoNet without post-processing, and panel (d) showcases the results of TopoNet with the post-processing, demonstrating improved precision in the lane topology prediction by correcting the endpoint overlap issue.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of results with and without post-processing in TopoNet. We use a post-processing based on geometric distance to improve the lane topology reasoning performance of TopoNet. (a) denotes the ground truth of lane topology reasoning. (b) denotes the endpoints of two connected lanes in prediction do not overlap (marked with yellow circle) as desired in ground truth. (c) denotes the lane topology reasoning result of TopoNet, the arrow denotes lane topology (marked with red arrow). (d) denotes the lane topology reasoning result of TopoNet using post-processing, significantly improves the reasoning precision of lane topology.

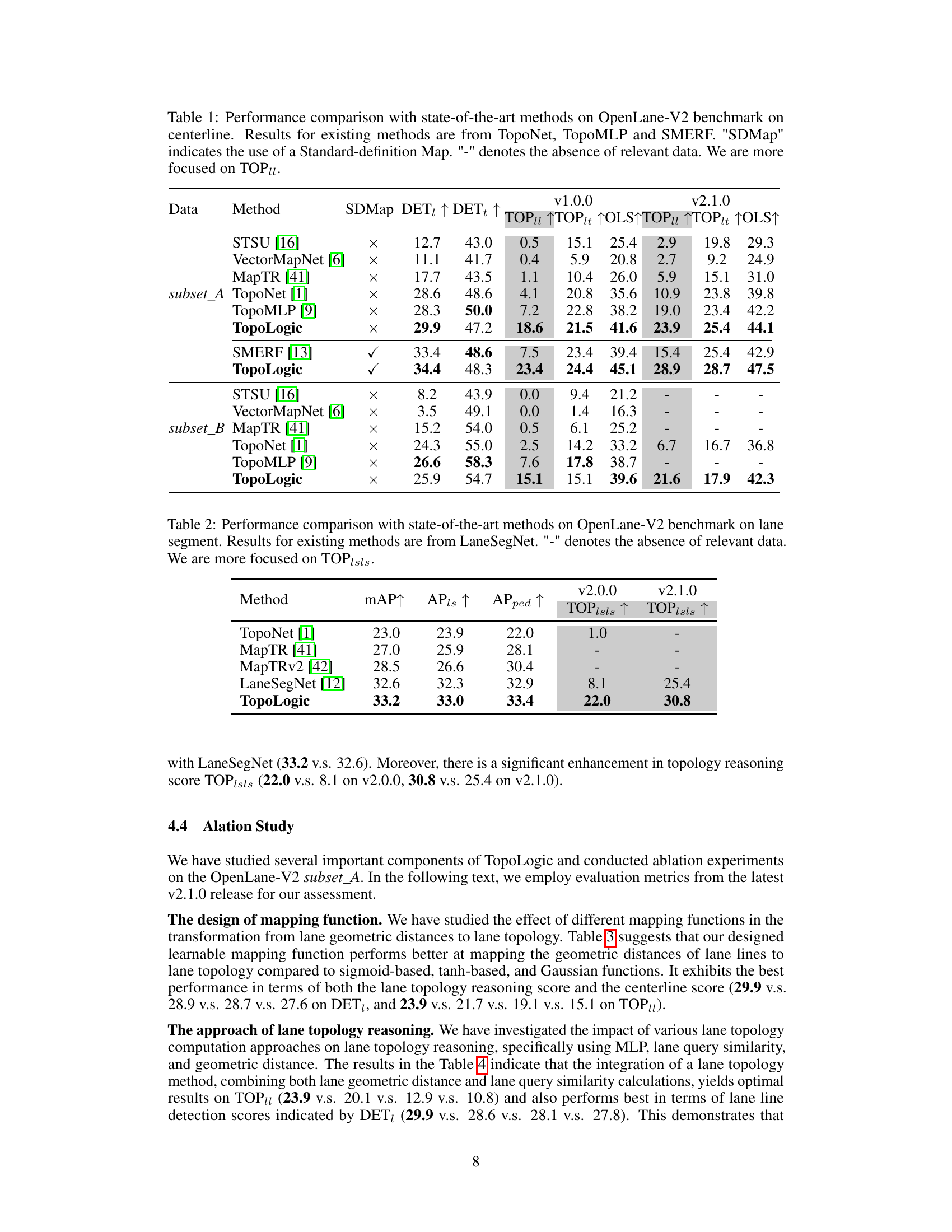

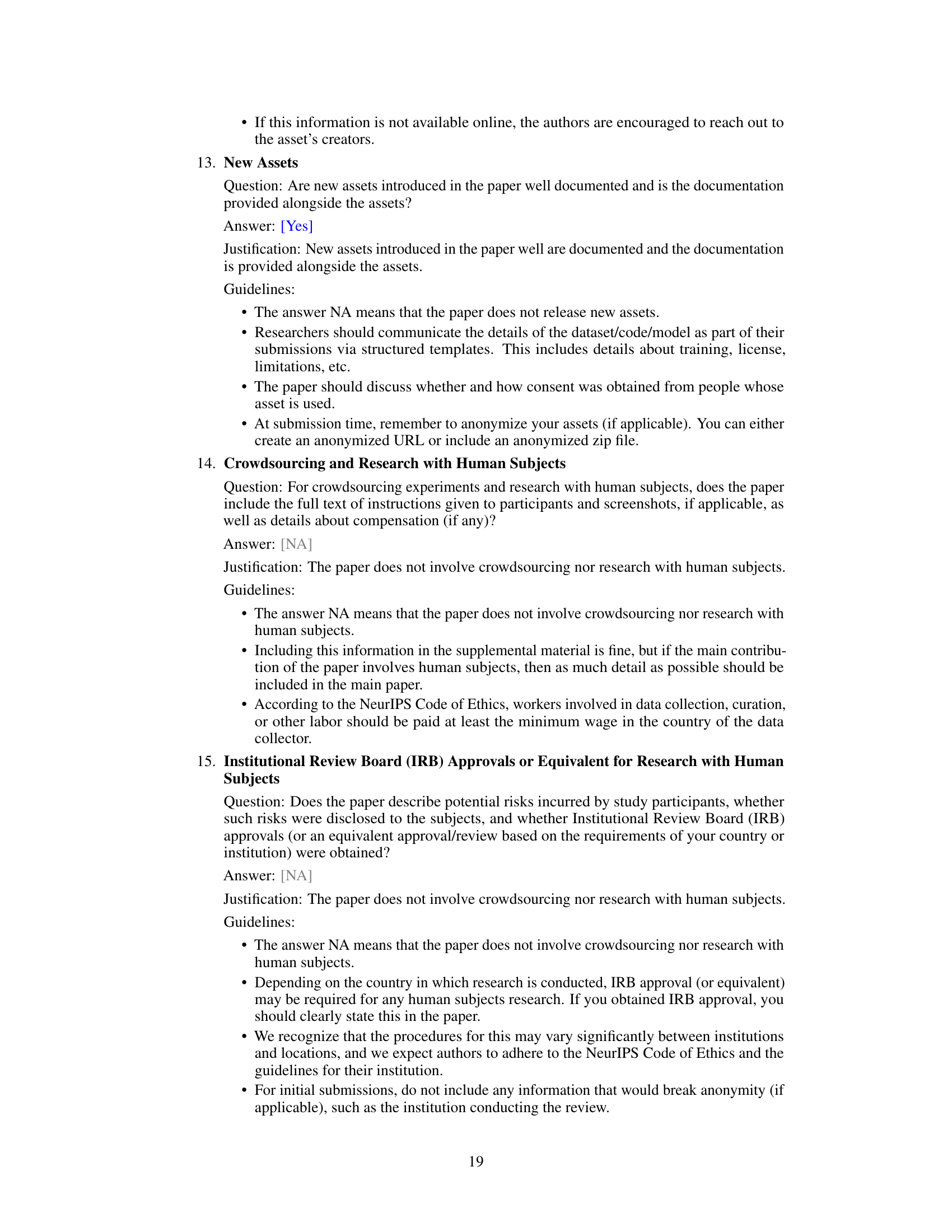

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed TopoLogic method with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for lane centerline detection on the OpenLane-V2 benchmark dataset. It shows various metrics including DET (distance error), TOPu (topology accuracy for lane-lane connections), and OLS (overall score). The use of supplementary Standard-definition Map data (SDMap) is also considered. The table highlights TopoLogic’s superior performance, particularly in terms of topology reasoning accuracy (TOPu).

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with state-of-the-art methods on OpenLane-V2 benchmark on centerline. Results for existing methods are from TopoNet, TopoMLP and SMERF. 'SDMap' indicates the use of a Standard-definition Map. '-' denotes the absence of relevant data. We are more focused on TOPu.

In-depth insights#

Lane Topology Reasoning#

Lane topology reasoning, a crucial aspect of autonomous driving, focuses on understanding the connectivity and relationships between lanes. Accurate lane topology is essential for safe and efficient navigation, enabling vehicles to make informed decisions about lane changes, merging, and path planning. Traditional methods often rely on simple geometric relationships between lane markings, which can be prone to errors due to occlusions or imperfect lane detection. Recent advancements leverage deep learning techniques, incorporating semantic information and graph neural networks to improve robustness and accuracy. Challenges remain in handling complex scenarios with poorly defined lanes or frequent changes in topology. Future research should explore incorporating more sophisticated reasoning models, integrating diverse sensor data, and developing robust techniques to address edge cases and uncertainties to achieve truly reliable and safe autonomous driving systems.

Geometric Distance#

The concept of geometric distance, in the context of lane topology reasoning, offers a robust approach to address the challenge of endpoint shifts in lane detection. By focusing on the geometric distance between lane endpoints, rather than relying solely on the perceived connectivity from lane queries, this method is less sensitive to minor inaccuracies in lane detection. This makes the system more reliable in complex scenarios. The interpretability of this approach is a significant advantage, as the geometric distance directly reflects the spatial relationship between lanes, providing a clear and intuitive understanding of the reasoning process. However, a limitation exists as this approach alone could be insufficient for accurate lane topology determination when lane detection is imprecise. Combining geometric distance with semantic similarity of lane queries enhances robustness and accuracy, mitigating this limitation. This fusion of geometric and semantic information represents a key strength, providing a more comprehensive and reliable method for lane topology reasoning, overcoming limitations encountered with previous methods that primarily focused on perception rather than reasoning. The effectiveness of incorporating geometric distance is further highlighted by its positive impact when used even as post-processing for existing well-trained models.

Interpretable Pipeline#

An interpretable pipeline in the context of a research paper, likely focuses on transparency and explainability of the machine learning model’s inner workings. It suggests a process designed to not only produce accurate results but also offer insights into how those results are derived. This is crucial for building trust and understanding, especially in high-stakes applications like autonomous driving (as suggested by the mention of lane topology in the prompt). The pipeline likely involves modular components, each performing a specific function, with clear connections and data flow between them. Interpretability might be achieved through visualization techniques, feature importance analysis, or the use of inherently interpretable models. The goal is to make the model’s decision-making process accessible, enabling researchers to identify potential biases, debug errors, and gain a deeper understanding of the underlying patterns in the data. The overall aim of the interpretable pipeline is to move beyond a ‘black box’ approach, thereby enhancing both scientific rigor and practical usability.

OpenLane-V2 Results#

The OpenLane-V2 results section would be crucial for evaluating the proposed lane topology reasoning method’s performance. I’d expect to see a comparison against other state-of-the-art methods, using standard metrics like Topology Accuracy (TOP) and Overall Lane Score (OLS). Quantitative results on both the lane centerline and lane segment tasks are essential, potentially broken down by difficulty level or scenario type within OpenLane-V2. A detailed analysis of the interpretability and robustness of the method (particularly its handling of endpoint shifts and noisy lane detection) should be included, ideally supported by visualizations or examples. Finally, a discussion of limitations and potential areas for future work would provide a holistic view of the results and their implications for autonomous driving.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for TopoLogic could involve exploring more sophisticated methods for fusing geometric and semantic lane topology information. Investigating advanced fusion techniques, beyond simple linear combination, such as attention mechanisms or graph neural networks, could significantly improve accuracy and robustness. Another promising area is improving lane detection, as the accuracy of lane topology reasoning is heavily reliant on the quality of input lane data. Advanced lane detection models that incorporate 3D information and handle challenging scenarios (e.g., occlusions, poor lighting conditions) could enhance the system’s overall performance. Finally, extending the approach to handle more complex lane configurations and diverse driving scenarios (e.g., intersections, curved roads) is critical for real-world applications. Research could also focus on developing efficient training strategies to reduce computation time and memory usage. Incorporating uncertainty estimation and out-of-distribution detection would strengthen the system’s reliability, thereby making TopoLogic more robust and suitable for deployment in real-world autonomous driving systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

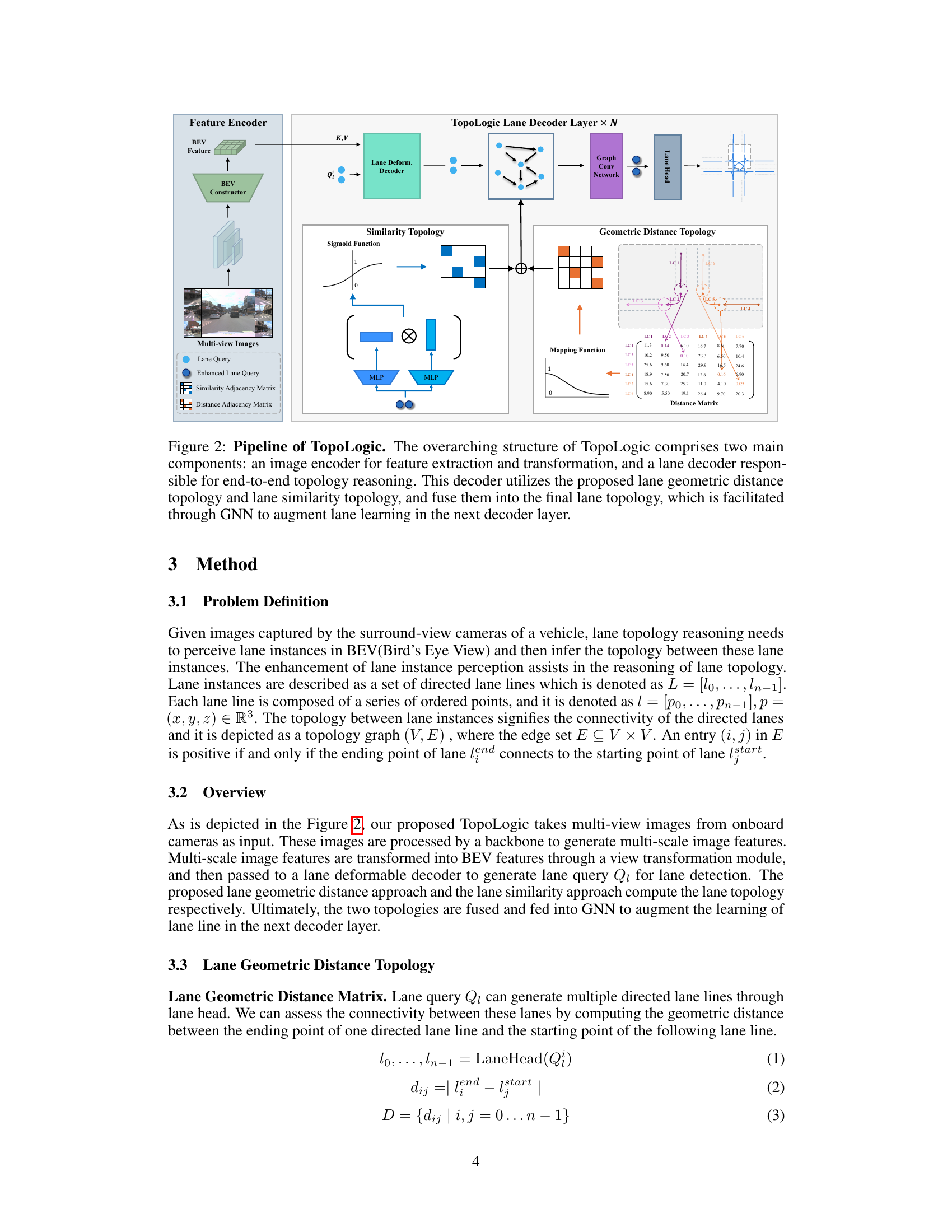

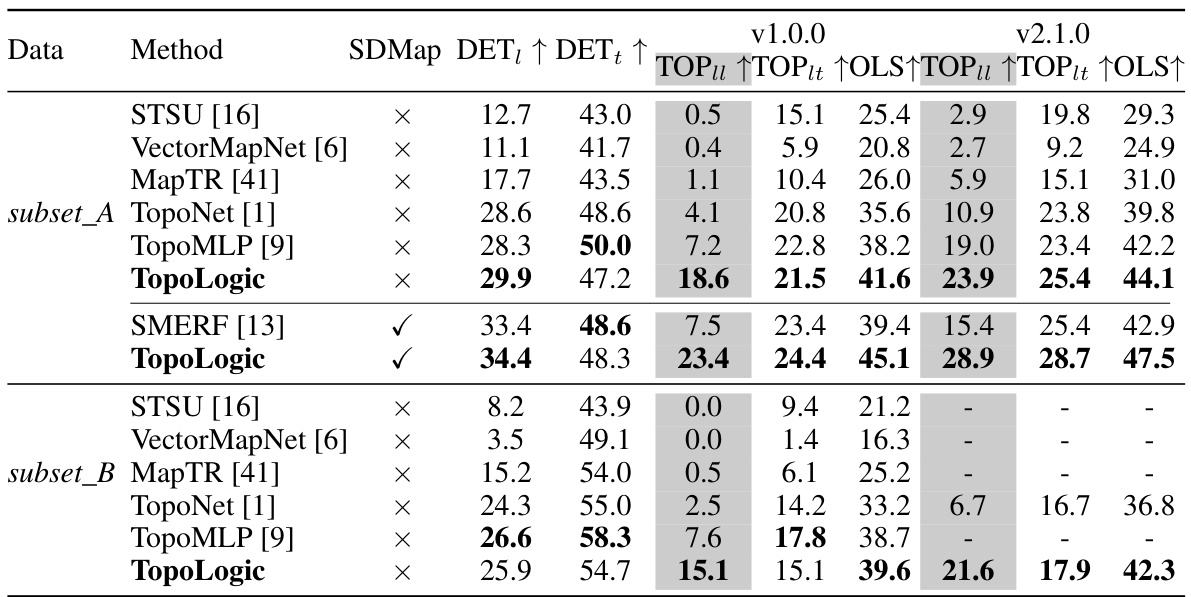

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the TopoLogic model. It shows two main components: an image encoder that processes multi-view images to extract and transform features into a bird’s eye view (BEV) representation, and a lane decoder that performs end-to-end lane topology reasoning. The lane decoder incorporates two parallel branches: one for calculating lane geometric distance topology and another for calculating lane similarity topology. These two topologies are then fused together using a learnable weighting scheme, and the result is fed into a graph convolutional network (GNN) to further enhance lane feature learning and refine the final lane topology output. The figure also illustrates the calculation of geometric distances between lane lines and the use of sigmoid function for mapping lane query similarity scores to topology.

read the caption

Figure 2: Pipeline of TopoLogic. The overarching structure of TopoLogic comprises two main components: an image encoder for feature extraction and transformation, and a lane decoder responsible for end-to-end topology reasoning. This decoder utilizes the proposed lane geometric distance topology and lane similarity topology, and fuse them into the final lane topology, which is facilitated through GNN to augment lane learning in the next decoder layer.

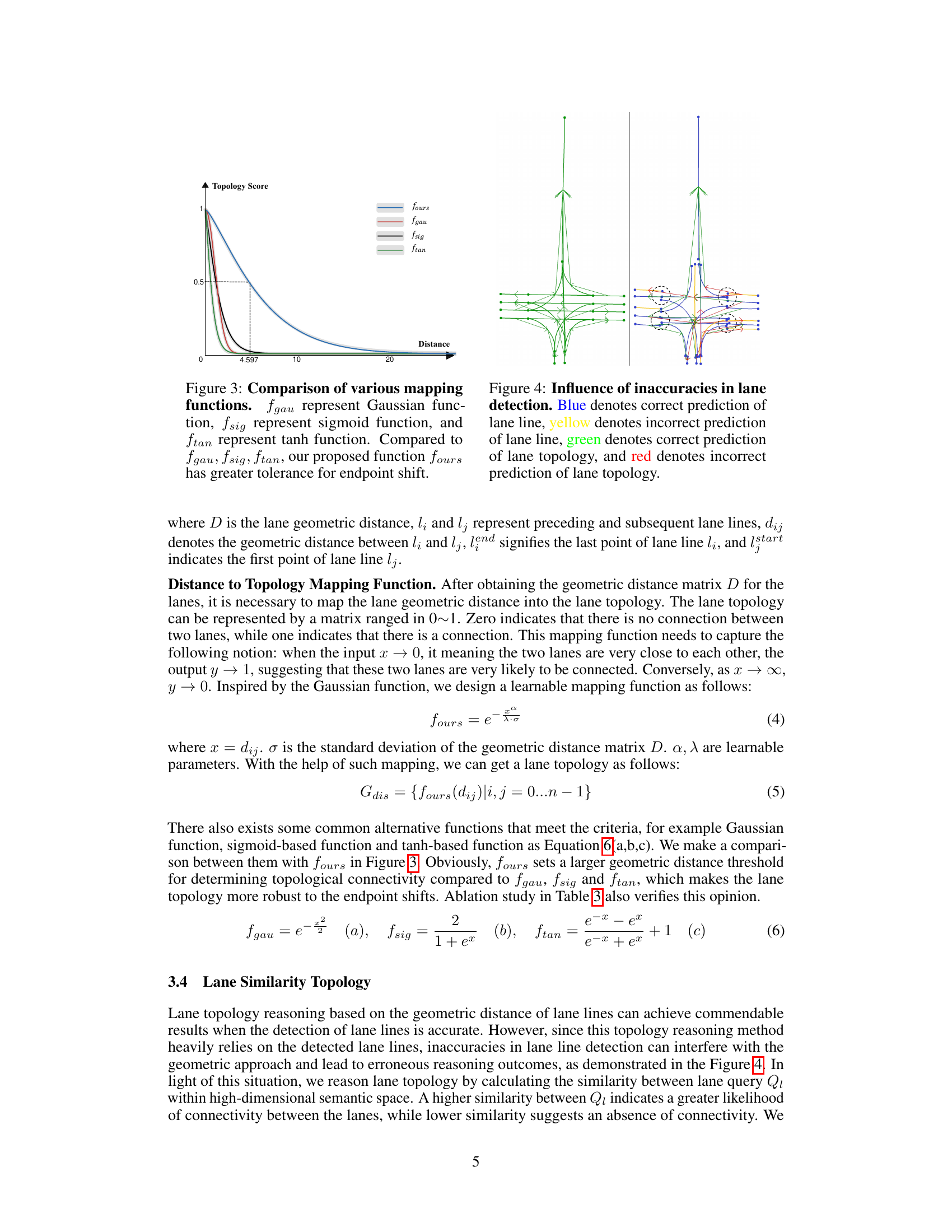

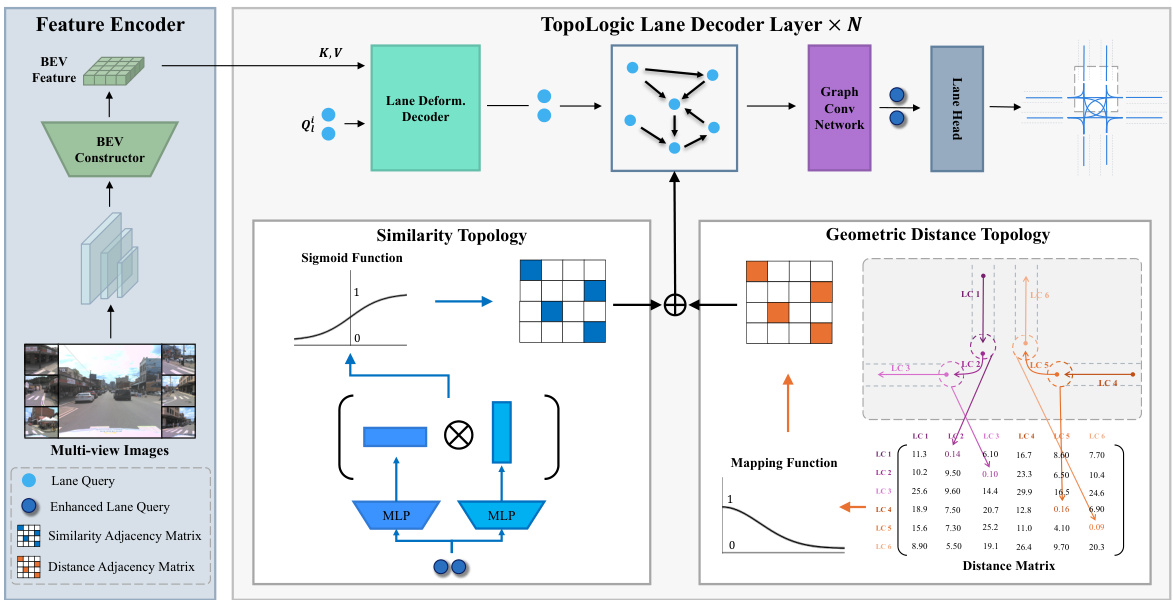

🔼 This figure compares four different mapping functions used to map lane geometric distance to lane topology. The x-axis represents the geometric distance between lane endpoints, and the y-axis represents the resulting topology score (probability of connectivity). The four functions are: Gaussian (fgau), sigmoid (fsig), tanh (ftan), and the authors’ proposed function (fours). The plot shows that the authors’ function, fours, has a wider tolerance for endpoint shift, meaning it is less sensitive to small variations in endpoint position.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of various mapping functions. fgau represent Gaussian function, fsig represent sigmoid function, and ftan represent tanh function. Compared to fgau, fsig, ftan, our proposed function fours has greater tolerance for endpoint shift.

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of lane topology reasoning results between TopoLogic and TopoNet using two example scenes. The top row displays the multi-view images used as input. The middle row presents the lane detection results and topology reasoning, comparing ground truth, TopoLogic’s predictions, and TopoNet’s predictions. The bottom row visualizes the lane topology as a graph, where nodes represent lanes and edges their connections. Green edges indicate correct topology predictions, red edges incorrect predictions, and blue edges missing predictions. This allows for a visual comparison of the accuracy and completeness of TopoLogic’s topology predictions against those of TopoNet.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative result about lane topology reasoning result of TopoNet and our TopoLogic. The first row denotes multi-view inputs. The second row denotes lane detection result and lane topology reasoning result. The third row denotes graph form of lane topology reasoning (node indicates lane line, edge indicates lane topology), where green color indicates the right prediction, while red color indicates the error prediction and blue color indicates missing prediction.

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison between TopoLogic and TopoNet, focusing on lane line detection and topology reasoning. Two scenes are shown with multi-view inputs, lane detection results, and lane topology graphs. The graphs visually represent the connectivity of lane lines, highlighting the superior accuracy and completeness of TopoLogic’s topology prediction compared to TopoNet. Red edges represent incorrect predictions, blue edges indicate missing predictions, and green edges represent correct predictions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative result about lane topology reasoning result of TopoNet and our TopoLogic. The first row denotes multi-view inputs. The second row denotes lane detection result and lane topology reasoning result. The third row denotes graph form of lane topology reasoning (node indicates lane line, edge indicates lane topology), where green color indicates the right prediction, while red color indicates the error prediction and blue color indicates missing prediction.

More on tables

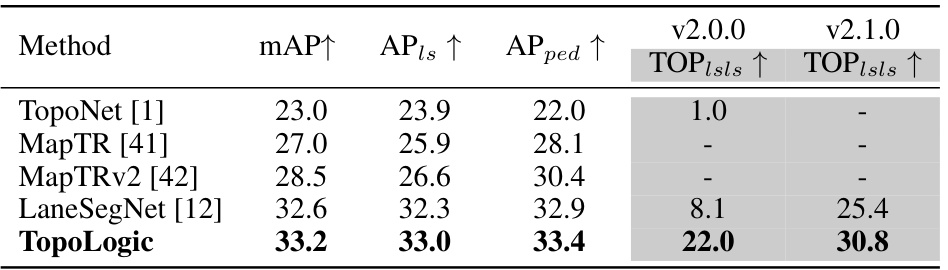

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of TopoLogic against other state-of-the-art methods on the lane segment task within the OpenLane-V2 benchmark. The metrics used include mean Average Precision (mAP), Average Precision for lane instances (APIs), Average Precision for lane pedestrians (APped), and Topology reasoning score for lane segments (TOPlsls). Note that the results for some methods are incomplete, indicated by hyphens. The focus is on the TOPlsls metric, reflecting topology reasoning performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance comparison with state-of-the-art methods on OpenLane-V2 benchmark on lane segment. Results for existing methods are from LaneSegNet. '-' denotes the absence of relevant data. We are more focused on TOPlsls.

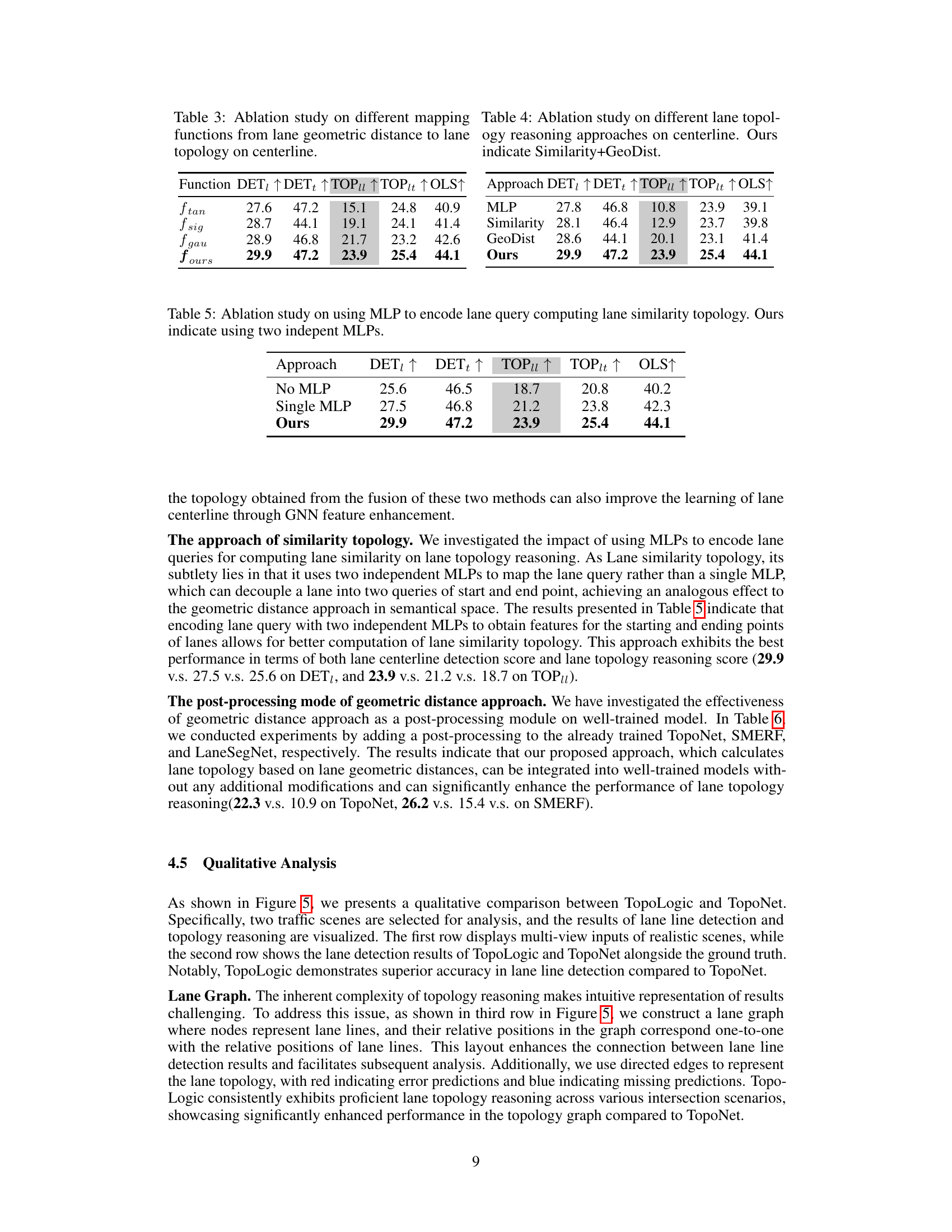

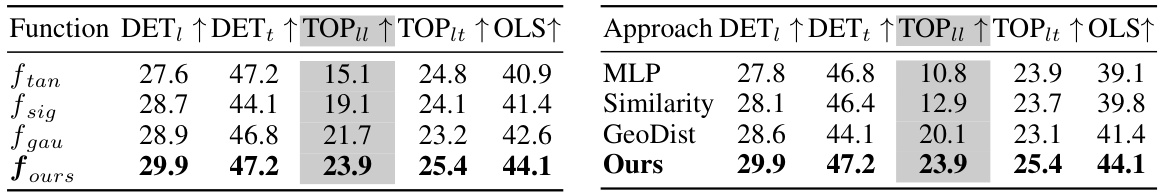

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the performance of different mapping functions used to transform lane geometric distances into lane topology. The study compares four functions:

f_tan,f_sig,f_gau, andf_ours. The table shows the impact of each function on various metrics, including DET₁, DETₜ, TOPᵤ, TOPᵢₜ, and OLS, demonstrating that the custom function (f_ours) yields the best overall performance, indicating a greater robustness to endpoint shifts in lane detection.read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study on different mapping functions from lane geometric distance to lane topology on centerline.

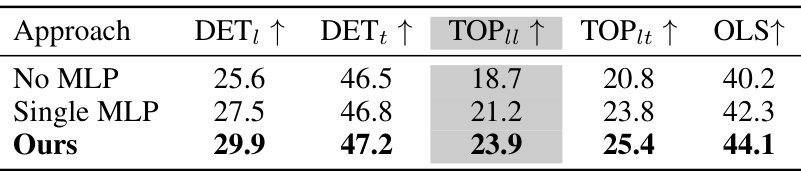

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of using different numbers of MLPs (Multilayer Perceptrons) to encode lane queries for computing lane similarity topology. The table shows that using two independent MLPs (the ‘Ours’ approach) yields superior results compared to using no MLP or a single MLP, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method for enhancing lane topology reasoning.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study on using MLP to encode lane query computing lane similarity topology. Ours indicate using two independent MLPs.

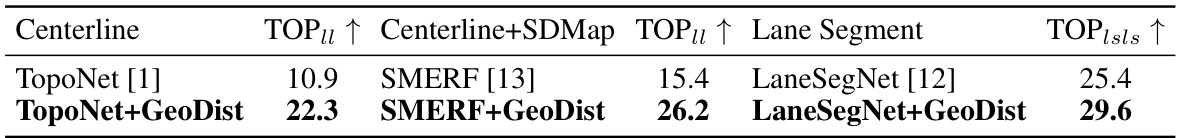

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the effectiveness of incorporating a geometric distance-based post-processing approach into three pre-trained models: TopoNet, SMERF, and LaneSegNet. The study assesses the impact on lane topology reasoning performance across three different tasks: centerline detection, centerline detection with an additional standard-definition map, and lane segment detection. The table shows that adding the geometric distance post-processing significantly improves the TOPu score (for centerline and centerline+SDMap) and the TOPisis score (for lane segment) across all three models.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation study on incorporating lane geometric distance into post-processing for well-trained model under different task settting (centerline / centerline+SDMap / lane segment).

Full paper#