↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many brain functions involve perception-action loops. Stochastic optimal control theory offers a mathematical framework for understanding these loops, but existing methods struggle to model realistic sensorimotor noise, especially internal noise. The seminal work of Todorov(2005) proposes a commonly used algorithm but has some critical flaws.

This paper addresses these limitations by proposing a new, efficient algorithm that minimizes cost-to-go while only requiring control law linearity. It demonstrates significantly lower overall costs than state-of-the-art methods, particularly in the presence of internal noise. The authors provide both numerical and analytical solutions, thereby offering broader applicability. This enhanced algorithm offers a refined approach for understanding how the brain’s sensorimotor system efficiently operates under noisy conditions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in optimal control theory and motor control, offering improved algorithms for handling realistic noise models in sensorimotor systems. It addresses limitations in existing methods, providing more accurate and efficient solutions that are particularly relevant for understanding behavioral data in neuroscience. The developed analytical approach opens new avenues for investigating optimal control in complex systems.

Visual Insights#

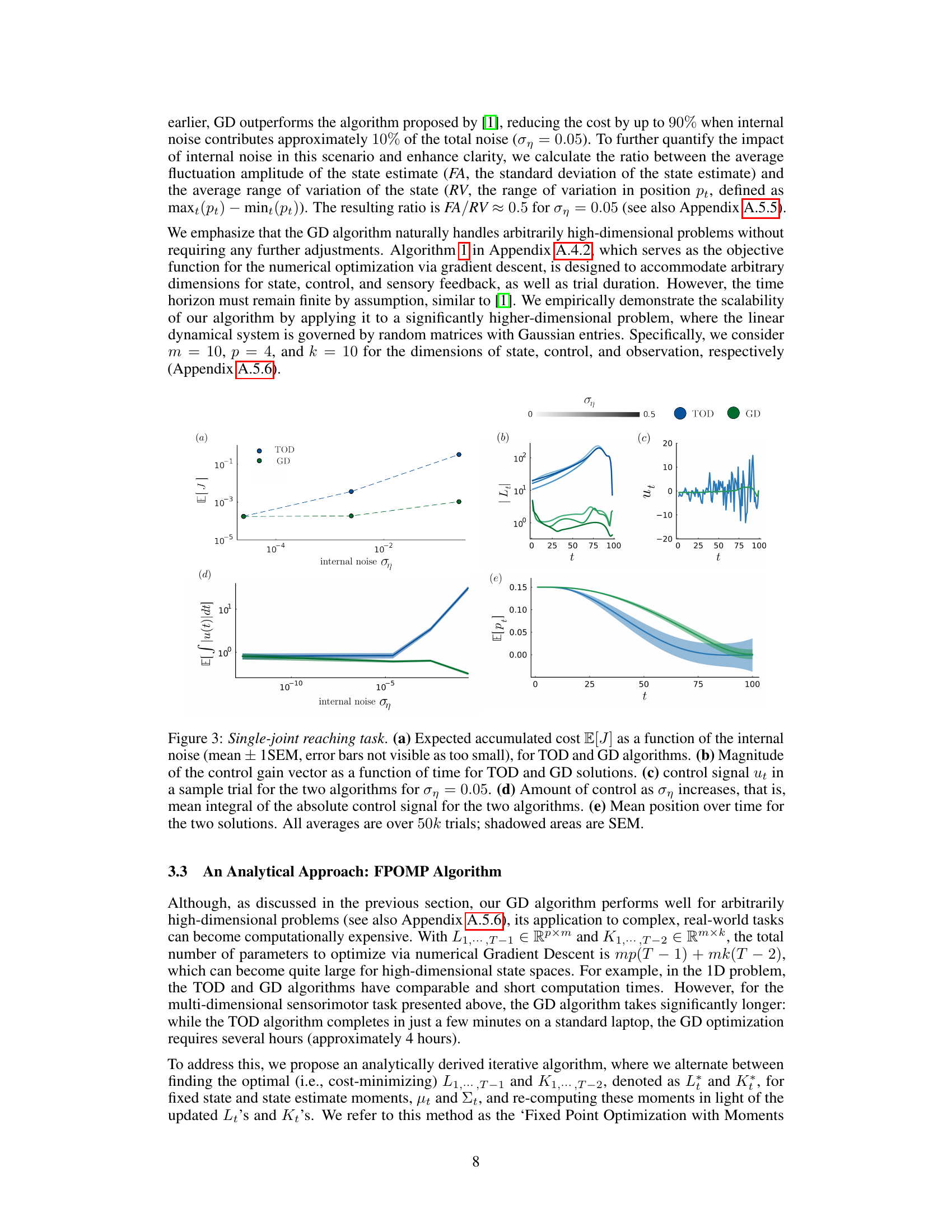

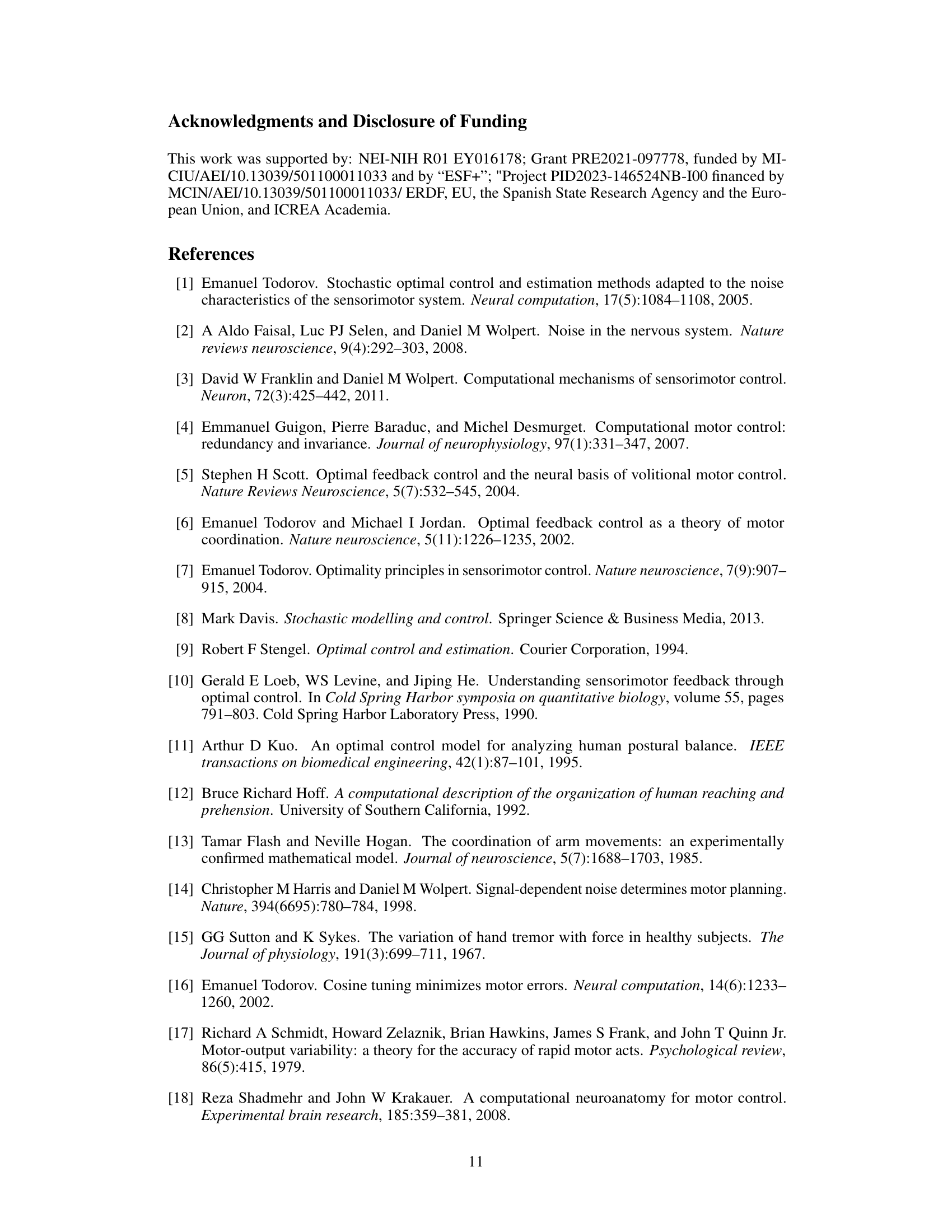

This figure demonstrates the bias in state estimation when internal noise is present. Panel (a) shows a simple example where internal noise causes the estimated state (red line) to deviate significantly from the true state (black line), resulting in a biased estimate. Panels (b) and (c) quantify this bias by plotting the conditional expectation of the true state given the estimated state for different levels of internal noise. The deviation from the identity line (gray line) indicates the magnitude of the bias, which is more pronounced with higher internal noise.

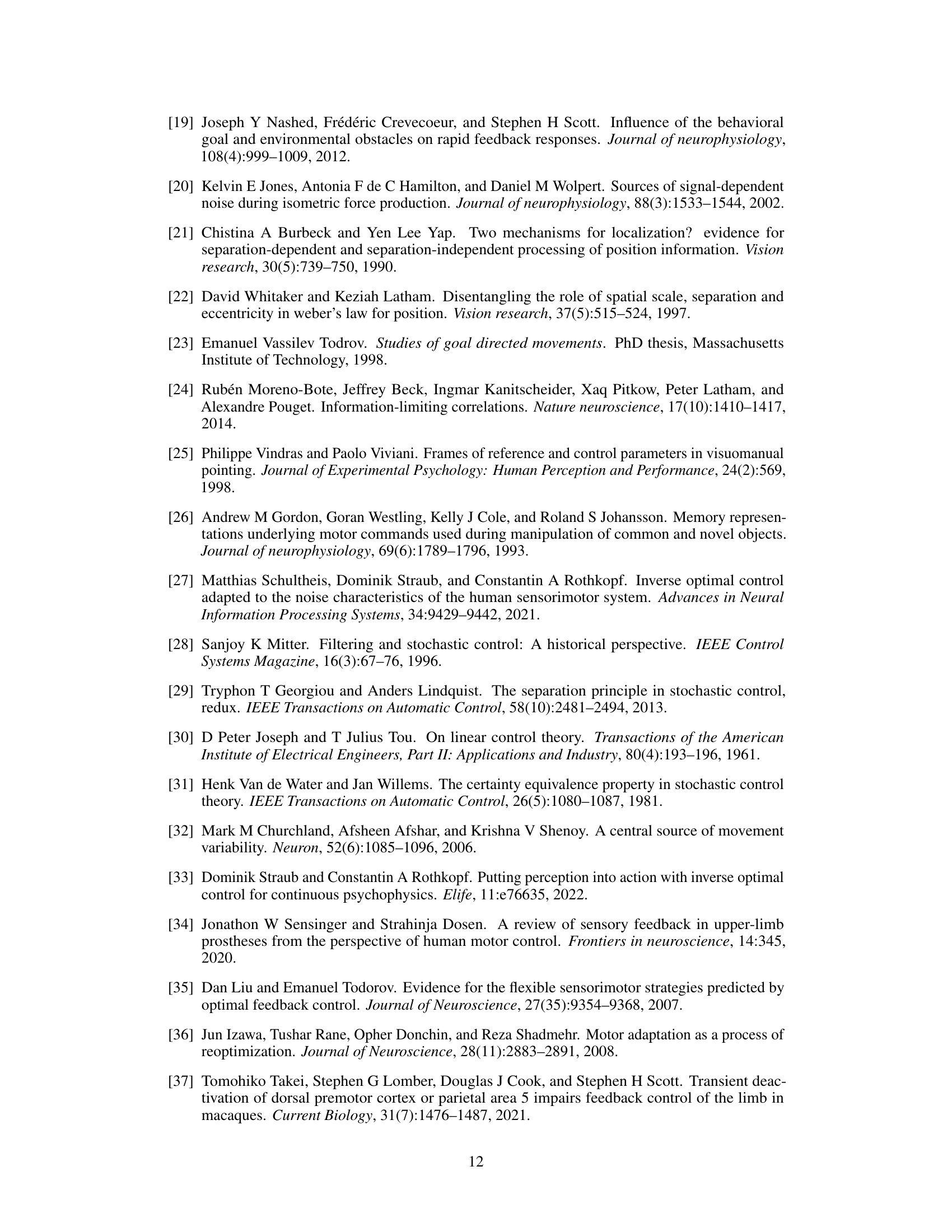

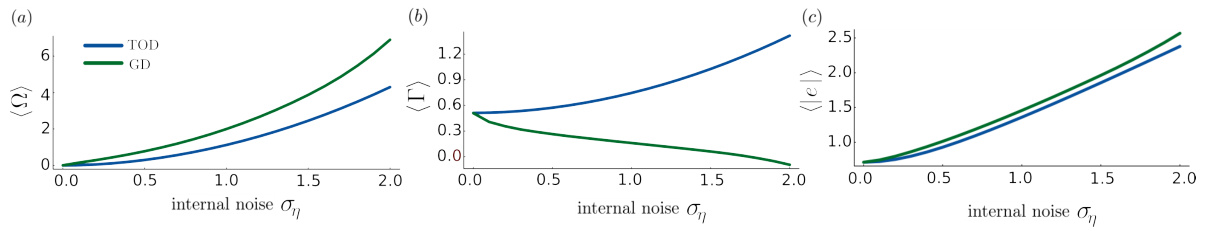

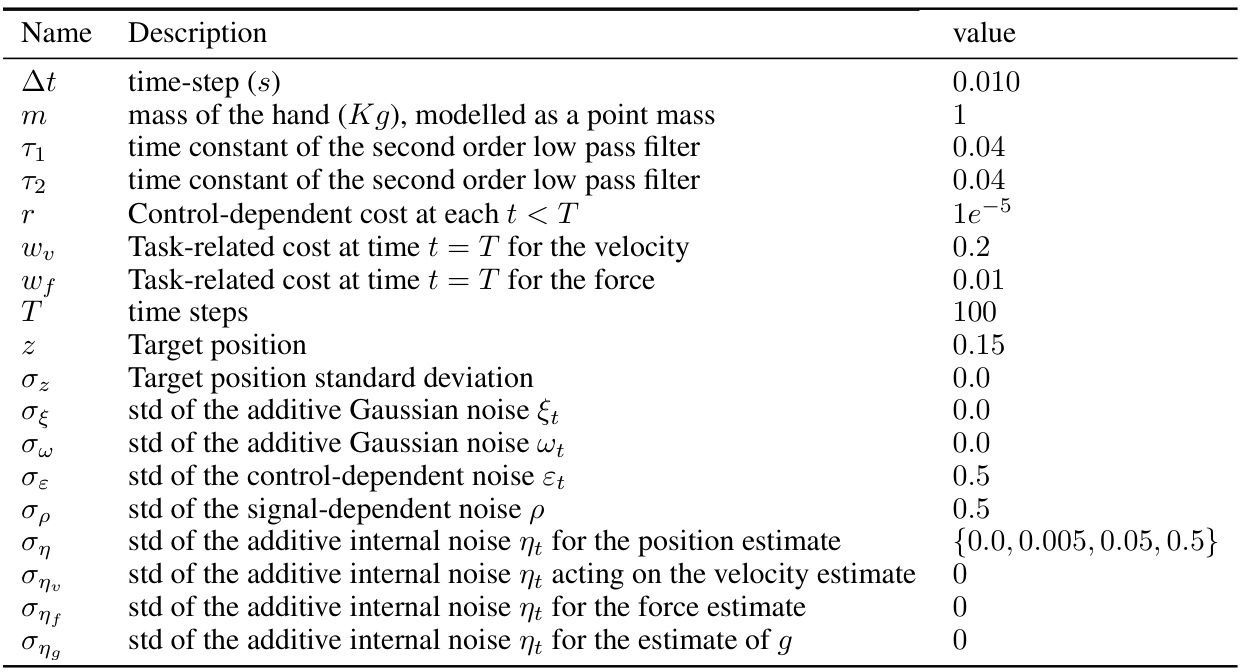

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the three algorithms discussed in the paper: GD (Gradient Descent), FPOMP (Fixed Point Optimization with Moments Propagation), and TOD (Todorov’s algorithm). It shows the number of iterations each algorithm uses for its respective optimization procedures.

In-depth insights#

LQMG Noise Model#

The Linear-Quadratic-Multiplicative-Gaussian (LQMG) noise model offers a more realistic representation of sensorimotor processes compared to the traditional Linear-Quadratic-Gaussian (LQG) model. It incorporates multiplicative noise, reflecting the fact that noise levels are often dependent on the magnitude of the signal, such as greater muscle force leading to greater noise in motor outputs or visual sensory noise increasing with distance from the fovea. The LQMG model also includes additive internal noise, representing internal neural fluctuations or inaccuracies in estimation. This extension significantly enhances the model’s ability to explain behavioral data, such as observed bell-shaped velocity profiles and speed-accuracy trade-offs in reaching movements, phenomena not well-captured by the simpler LQG model. However, the increased complexity of the LQMG model necessitates more sophisticated solution methods, as analytical solutions become intractable. The paper addresses this challenge and proposes a novel algorithm to efficiently solve optimal control problems under the LQMG framework. The key improvement lies in the removal of the inaccurate assumption of unbiased estimators, which is often made in traditional derivations and leads to suboptimal performance, especially in the presence of internal noise.

Optimal Control Law#

The concept of an optimal control law is central to the research paper, representing the core algorithmic solution for achieving desired control objectives in a noisy sensorimotor system. The study focuses on improving the derivation and implementation of this law, particularly addressing shortcomings in existing methods. The proposed improvements involve an efficient gradient descent optimization, minimizing the cost-to-go while imposing only linearity of the control. This shift offers a more accurate and effective approach, especially when dealing with significant internal noise. Crucially, the research highlights that unbiased estimation is not a valid assumption in this context, which previous methods erroneously relied on. The resulting optimal control law is shown to be superior, providing significantly lower overall costs and exhibiting better performance in the presence of realistic sensorimotor noise.

Bias in Estimation#

The concept of ‘Bias in Estimation’ within the context of stochastic optimal control is crucial. Unbiased estimators are commonly assumed, simplifying calculations but often unrealistic in real-world systems. The authors highlight that the seminal algorithm in [1] erroneously assumes unbiased estimation, leading to suboptimal performance, especially in the presence of internal noise. This bias stems from the failure of the orthogonality principle, typically guaranteed in the ideal Linear-Quadratic-Additive-Gaussian (LQAG) setting but violated in the more realistic Linear-Quadratic-Multiplicative-Gaussian (LQMG) model with internal noise. The unbiasedness assumption does not hold for the optimal Kalman filter in the LQMG framework with non-zero internal noise, impacting the overall control strategy and resulting in an inaccurate estimation. The paper’s major contribution lies in addressing this crucial issue, proposing an improved algorithm that accurately accounts for this inherent estimation bias, leading to significantly improved overall cost and more robust control performance.

Gradient Descent#

In the context of optimizing a cost function within a stochastic optimal control framework, gradient descent methods offer a powerful approach to iteratively refine control and filter parameters. The core idea is to calculate the gradient of the cost function with respect to these parameters and then update them in the opposite direction of the gradient. This ensures that the cost function is progressively minimized with each iteration. However, the choice of learning rate (step size) is crucial. A small learning rate results in slow convergence, while a large learning rate might lead to oscillations or even divergence. Adaptive learning rate schemes can mitigate this issue by dynamically adjusting the step size based on the optimization landscape. Furthermore, the computational cost associated with gradient calculations becomes a significant factor for high-dimensional problems, motivating exploration of efficient approximation methods or alternative optimization algorithms like the proposed analytical solution. The effectiveness of gradient descent ultimately hinges on the smoothness and convexity of the cost function. Non-convexity can trap the optimization process in local minima, necessitating advanced techniques such as simulated annealing or multiple restarts from randomized initializations. Therefore, a careful analysis of the cost function’s properties and a strategic selection of gradient descent implementation details are paramount to ensure efficient and effective parameter optimization within stochastic optimal control problems.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore relaxing the linearity assumption in the control law, potentially employing techniques like the Koopman operator to handle nonlinear systems. Investigating the impact of non-Gaussian noise models would also be valuable, moving beyond the Gaussian assumptions. A significant extension would involve developing and testing the algorithm’s performance in real-world scenarios. This includes tasks beyond the simulated reaching tasks, such as grasping or locomotion. Finally, further exploration of the relationship between the optimal control law and biologically plausible learning rules could provide a deeper understanding of the brain’s control mechanisms and inspire more biologically realistic computational models. This might also involve integrating the theoretical advancements with experiments, providing a bridge between theory and empirical observation. Such rigorous experimental testing would solidify the applicability and scope of the proposed solutions and yield novel insights into the intricate workings of sensorimotor systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

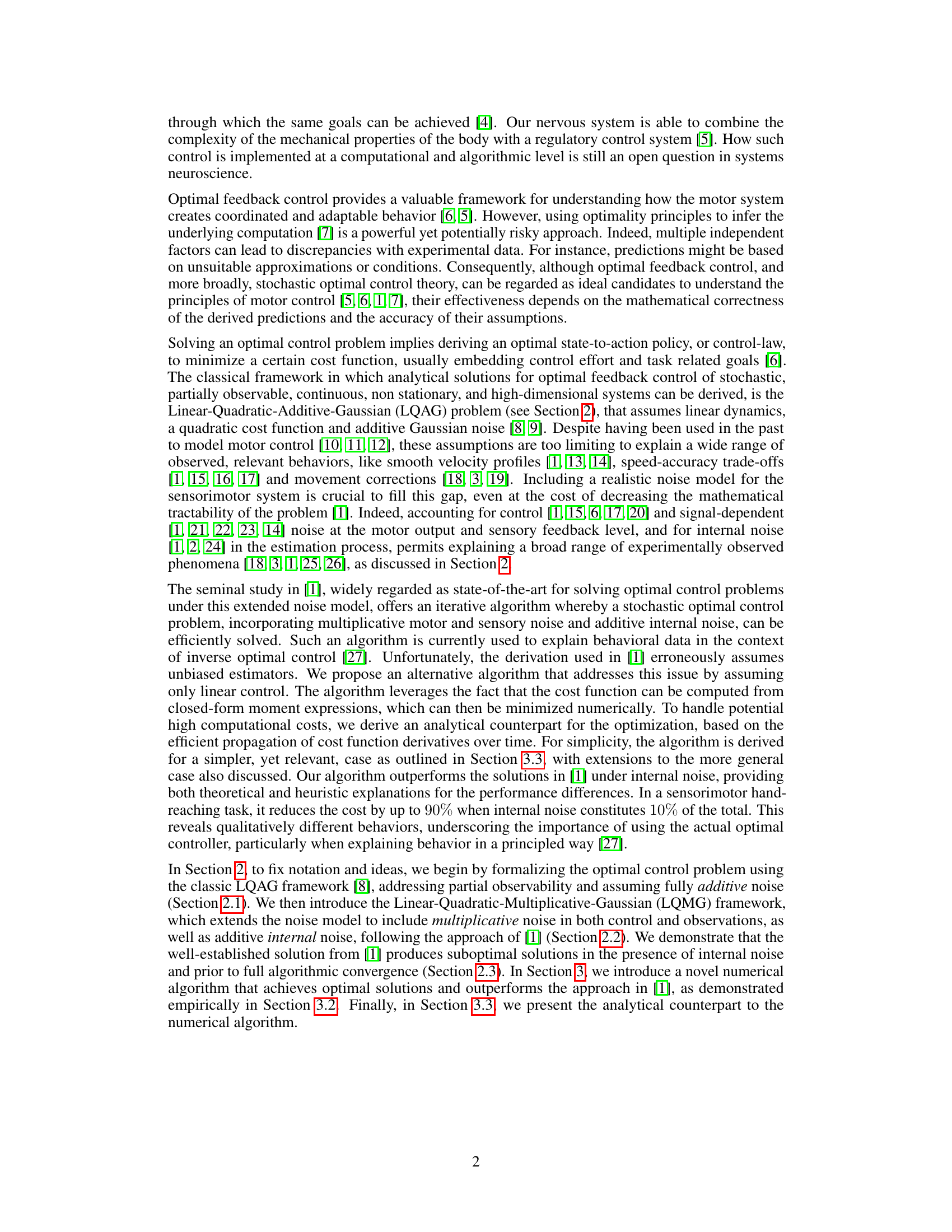

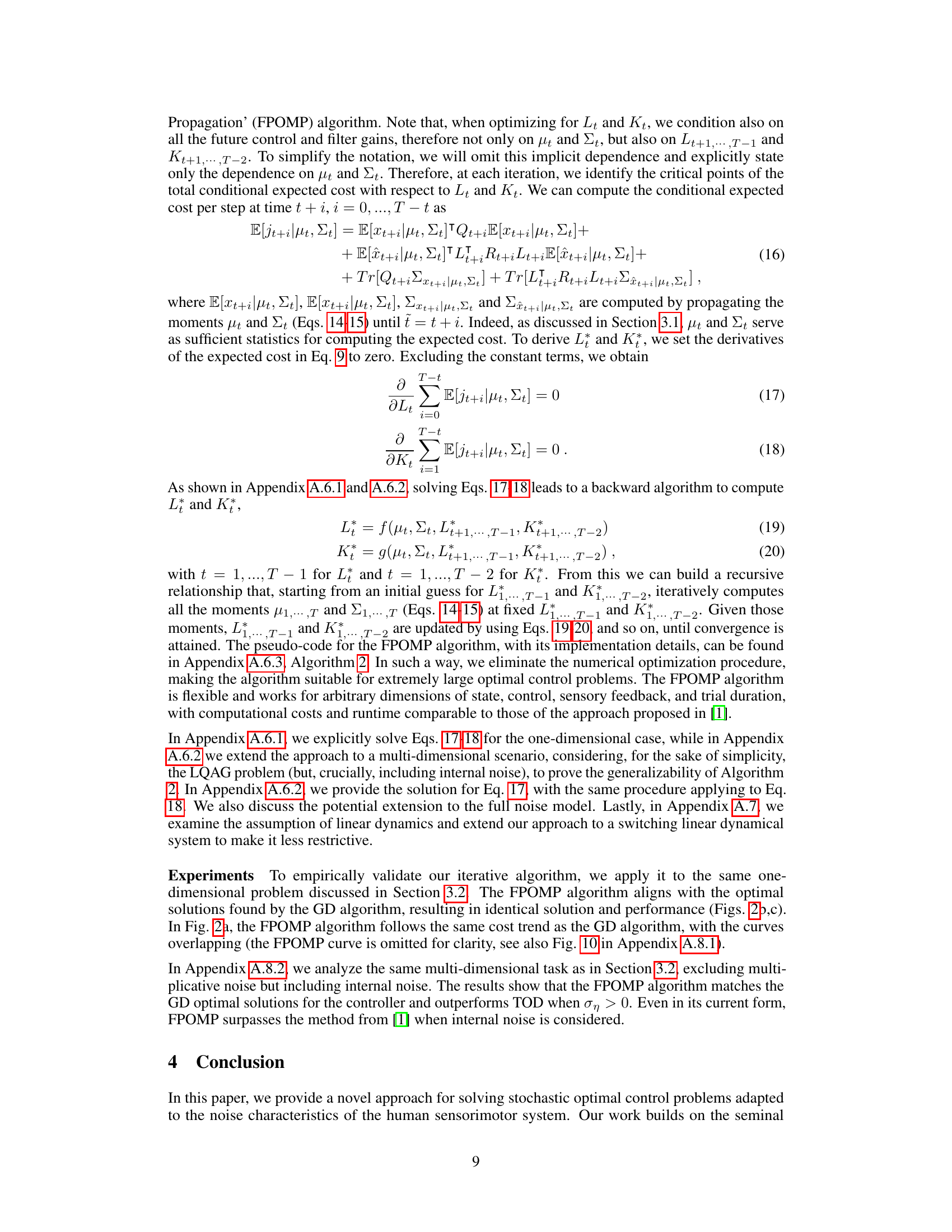

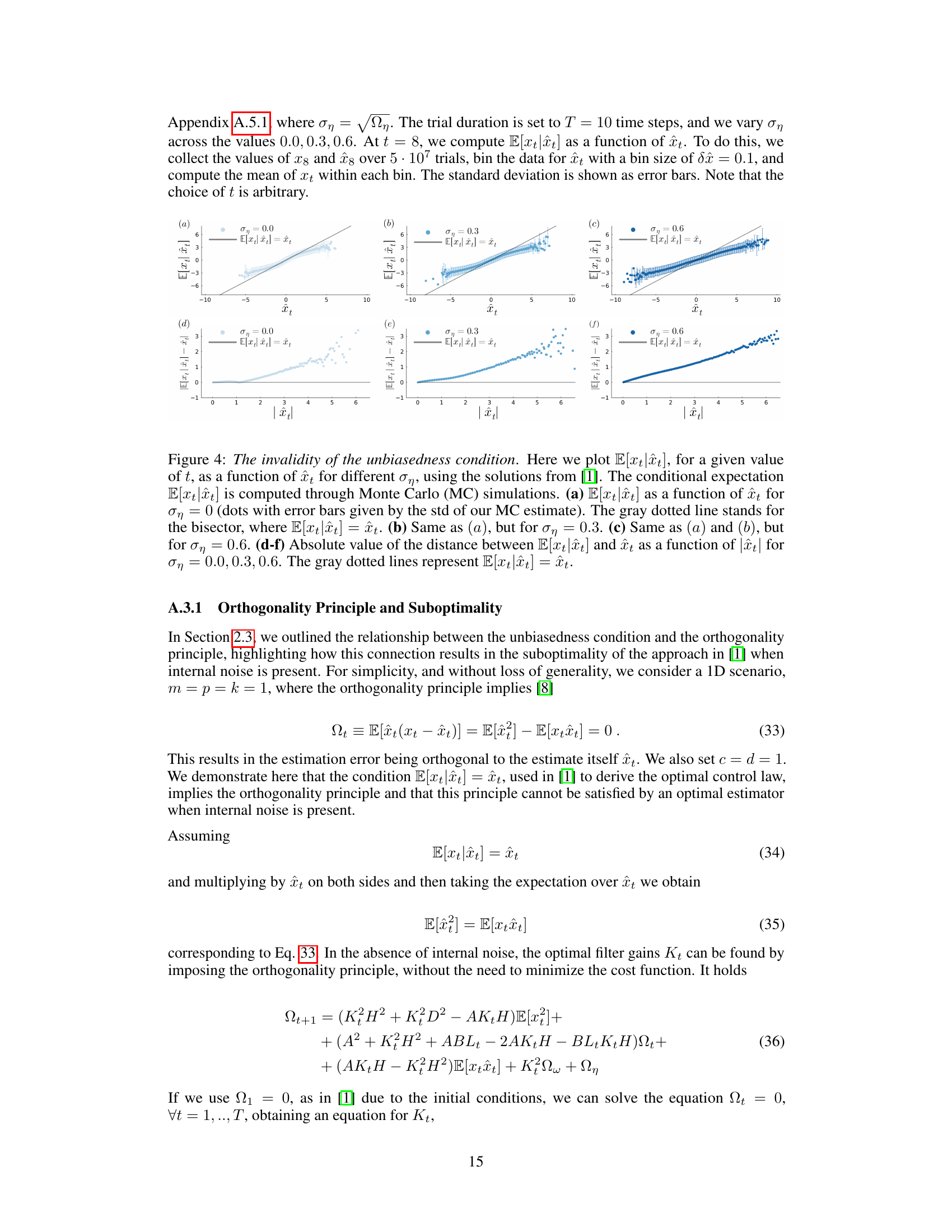

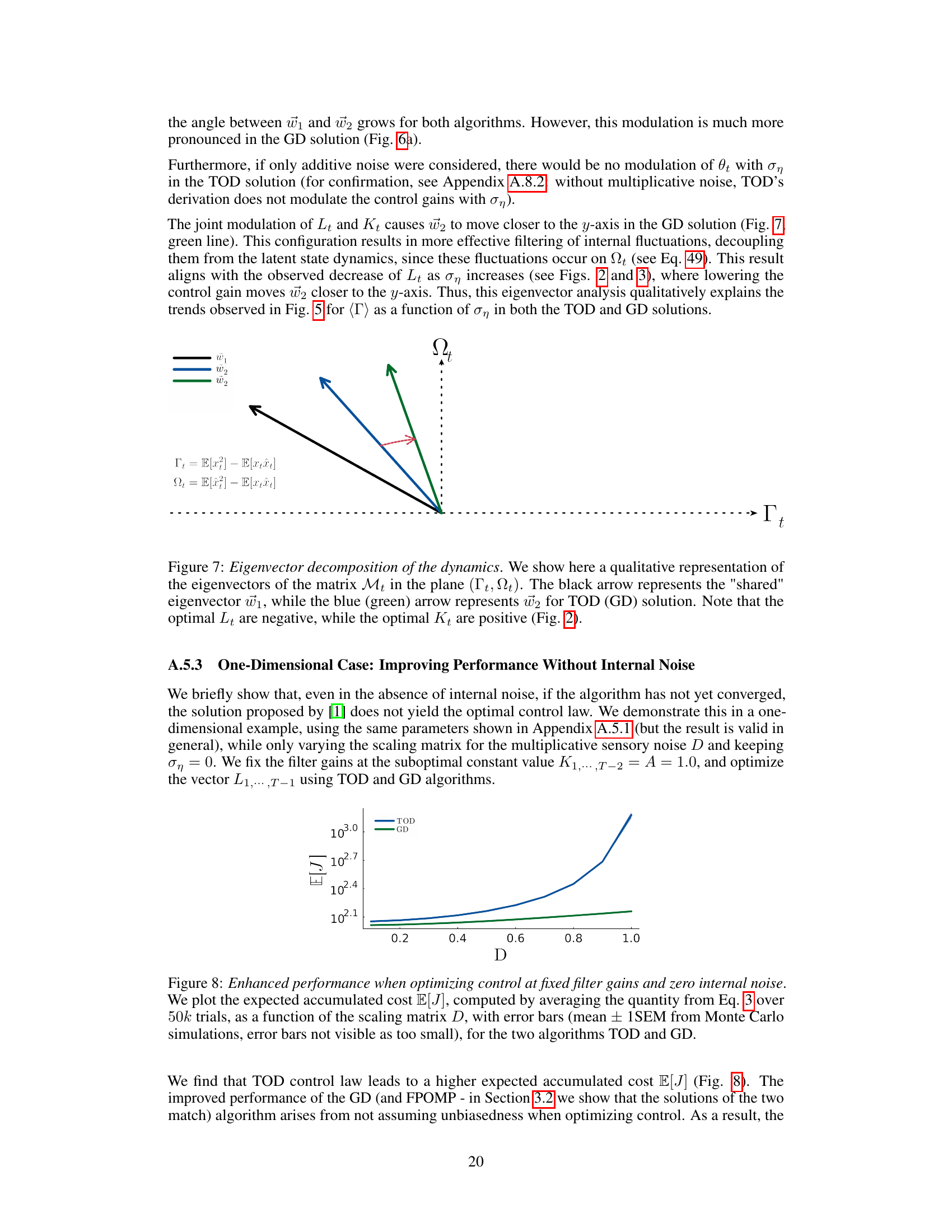

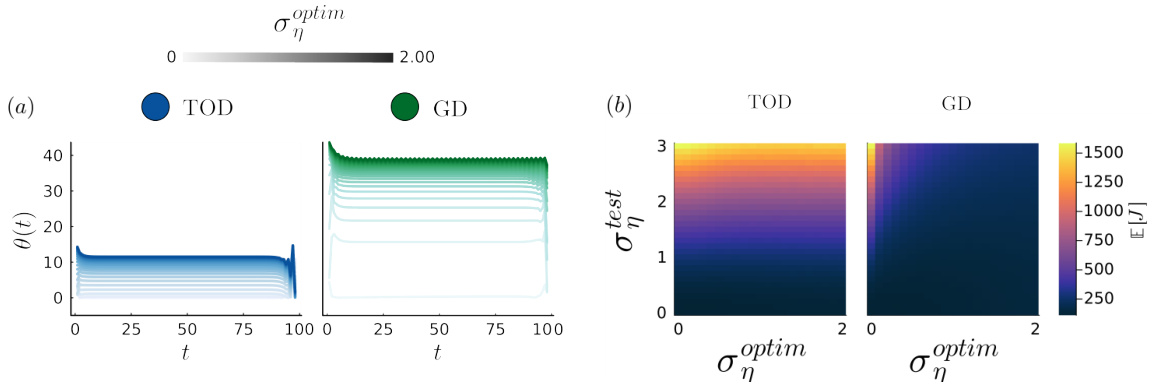

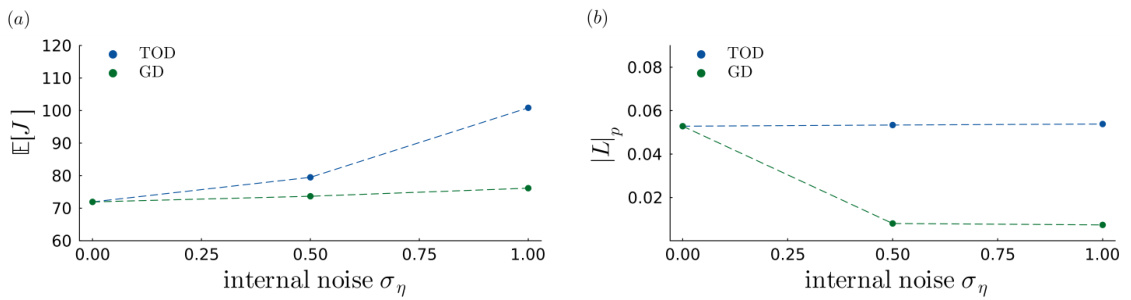

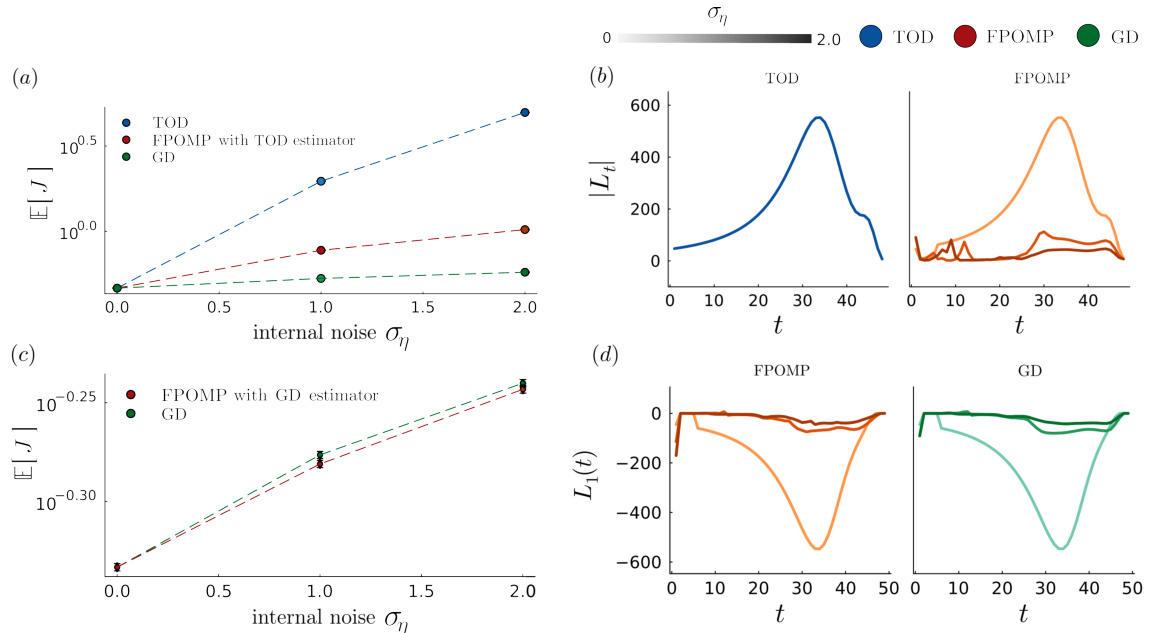

This figure compares the performance of three algorithms (TOD, GD, and FPOMP) for solving an optimal control problem with internal noise. Panel (a) shows the expected accumulated cost as a function of internal noise strength for each algorithm, demonstrating GD’s superiority. Panels (b) and (c) display the optimal control and filter gains (Lt and Kt) over time for each algorithm, highlighting the differences in their gain modulation strategies with varying internal noise levels. The results illustrate that the GD algorithm achieves lower costs by adapting its gains more effectively to internal noise compared to TOD.

This figure compares the performance of the TOD and GD algorithms in a one-dimensional reaching task with varying levels of internal noise. Panel (a) shows the accumulated cost for both algorithms, demonstrating that GD significantly outperforms TOD, especially with higher internal noise. Panels (b) and (c) illustrate how the optimal control and filter gains (Lt and Kt) change as internal noise increases, revealing differences in how the two algorithms adapt. The inclusion of FPOMP results further validates the GD algorithm’s accuracy.

This figure demonstrates the issue of unbiasedness in the estimation process when internal noise is present. Panel (a) shows a toy example illustrating how internal noise can bias the state estimate. Panels (b) and (c) show the conditional expectation E[xt|ît] as a function of the state estimate ît for different levels of internal noise (ση = 0.0 and ση = 0.6). The results show that the unbiasedness condition E[xt|ît] = ît does not hold in the presence of internal noise.

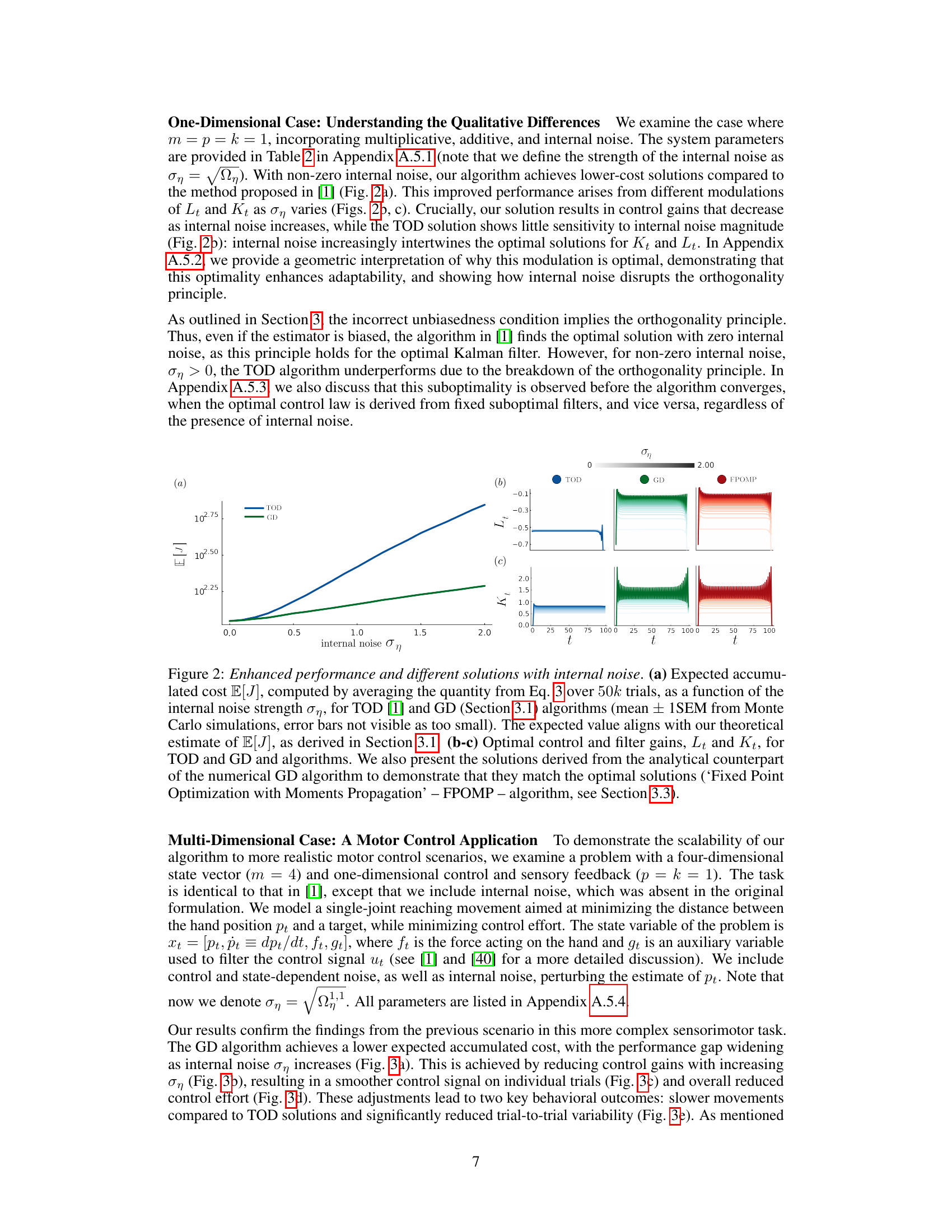

This figure compares the performance of the TOD and GD algorithms in solving the Linear-Quadratic-Multiplicative-Gaussian (LQMG) optimal control problem with internal noise. Panel (a) shows that the GD algorithm consistently achieves a lower expected accumulated cost than the TOD algorithm across different levels of internal noise. Panels (b) and (c) illustrate how the optimal control (Lt) and filter (Kt) gains vary as a function of internal noise for both algorithms, revealing distinct modulation patterns. The inclusion of FPOMP results demonstrates the numerical GD and analytical methods produce near-identical results.

This figure compares the performance of the TOD and GD algorithms in terms of accumulated cost and control/filter gains across different levels of internal noise. The results indicate a substantial performance improvement of GD algorithm compared to the TOD, particularly with higher internal noise, while providing optimal control and filter gain modulations.

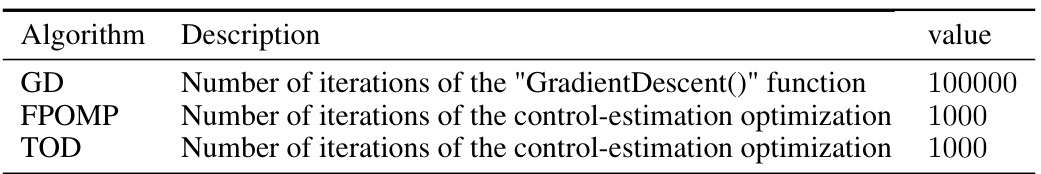

This figure shows a qualitative representation of the eigenvectors of the matrix Mt in the plane (Γt, Ωt). The eigenvectors’ angles are used to explain how the optimal control and filter gains modulate with internal noise (ση) in the GD algorithm, leading to better noise filtering and generalization compared to the TOD algorithm. The black arrow represents the ‘shared’ eigenvector, while blue and green arrows represent the second eigenvector for the TOD and GD algorithms, respectively. Note that the optimal Lt are negative, and Kt are positive.

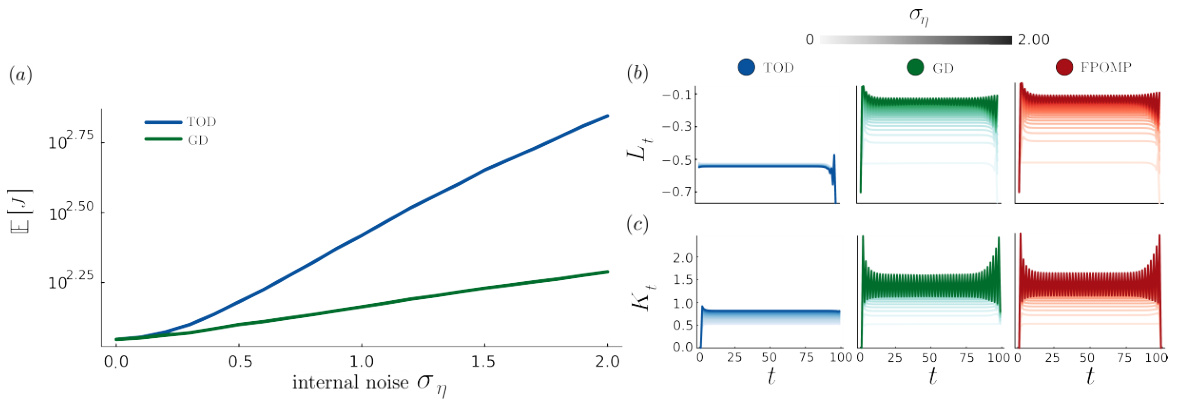

The figure shows the expected accumulated cost (E[J]) as a function of the scaling matrix D for two different algorithms: TOD and GD. The results demonstrate that GD outperforms TOD, especially when the filter gains are held constant at suboptimal values. This highlights the importance of the unbiasedness condition for accurate cost estimation and control.

This figure shows the results of a high-dimensional experiment (m=10, p=4, k=10) comparing the performance of the proposed GD algorithm to the TOD algorithm from [1], in terms of accumulated cost (a) and control gain magnitude (b), as a function of internal noise (ση). The GD algorithm demonstrates consistently lower costs and a more nuanced modulation of control gains in response to varying internal noise levels.

This figure compares the accumulated costs obtained from the Gradient Descent (GD) and Fixed Point Optimization with Moments Propagation (FPOMP) algorithms across various levels of internal noise (ση). The difference in accumulated costs (E[JGD - JFPOMP]) is plotted against the internal noise levels. The shaded area represents the standard error of the mean (SEM). The plot demonstrates that the two algorithms yield very similar results in terms of accumulated cost.

This figure compares the performance of three algorithms (TOD, GD, and FPOMP) in solving an optimal control problem with internal noise. Panel (a) shows the expected accumulated cost as a function of internal noise strength for each algorithm. Panels (b) and (c) show the optimal control and filter gains, respectively, as a function of internal noise strength for each algorithm. The figure demonstrates that the GD and FPOMP algorithms significantly outperform the TOD algorithm, especially in the presence of internal noise.

More on tables

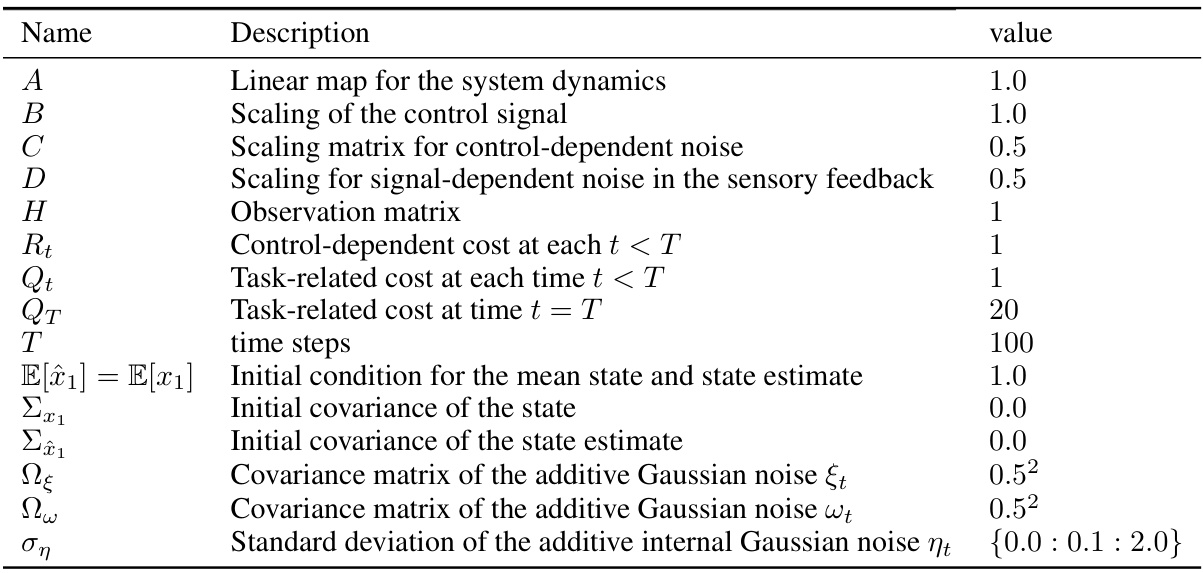

This table lists the parameters used in the one-dimensional problem used to illustrate the invalidity of the unbiasedness condition. It includes parameters related to the system dynamics (A, B, C, D, H), cost function (R, Q, QT), noise covariances (Ωε, Ωω, ση), and initial conditions (E[x1], Σx1, Σî1). Understanding these parameters is crucial for interpreting the results presented in figures showing the impact of internal noise.

This table lists the parameters used in the multi-dimensional sensorimotor task simulation. It includes parameters related to the physical model (mass, time constants), cost function parameters, noise levels (additive, multiplicative, and internal), and initial conditions. These parameters define the specific characteristics of the simulated reaching task and are crucial in determining the optimal control and filter gains.

This table lists the parameters used in the simulation of a single-joint reaching task. These parameters define aspects of the hand’s physical properties (mass, time constants of filters), costs associated with control effort and deviations from the target, noise levels, and the initial conditions for the task. The parameters are used to test the performance of various optimal control algorithms described in the paper, enabling a comparison of their effectiveness under different conditions of noise and task requirements.

Full paper#