TL;DR#

Many computational tasks rely on first-order optimization (FOO) algorithms, but their convergence often requires numerous sequential iterations, hindering efficiency. Current parallel computing approaches primarily focus on reducing computational time per iteration instead of decreasing the number of iterations needed. This limitation motivates the need for innovative methods that enhance FOO’s optimization efficiency.

The paper proposes OptEx, a new framework leveraging parallel computing to directly address this issue. OptEx utilizes a kernelized gradient estimation technique to predict future gradients, enabling the approximate parallelization of iterations. The framework provides theoretical guarantees for reduced iteration complexity and showcases significant efficiency gains through experiments on various datasets, encompassing synthetic functions, reinforcement learning, and neural network training. This approach offers potential improvement in deep learning and other optimization-heavy applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents OptEx, a novel framework for accelerating first-order optimization algorithms by approximately parallelizing iterations. This addresses a critical limitation of traditional methods and has potential applications across diverse computational domains, impacting research trends in reinforcement learning and deep learning. It opens avenues for further research into parallel optimization techniques and related theoretical analyses.

Visual Insights#

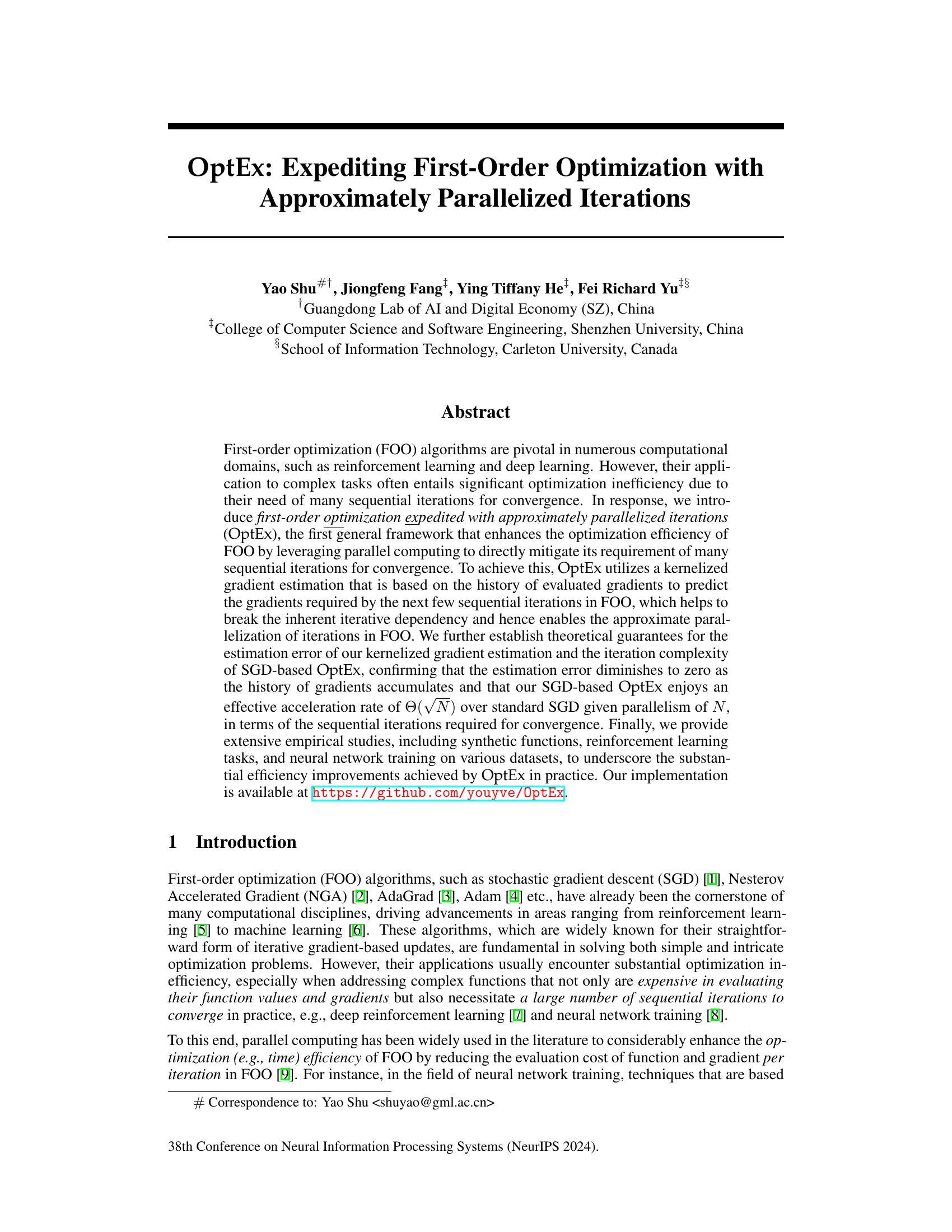

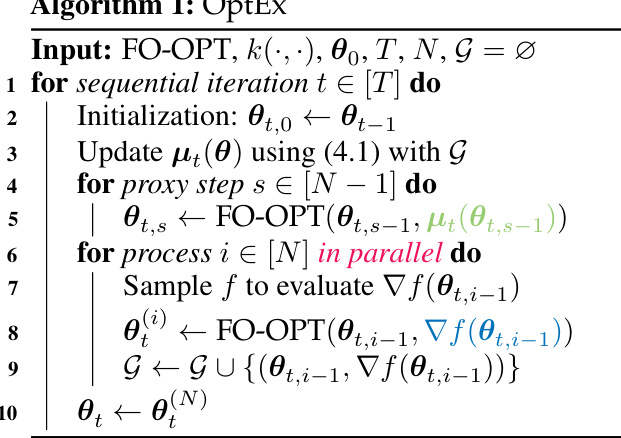

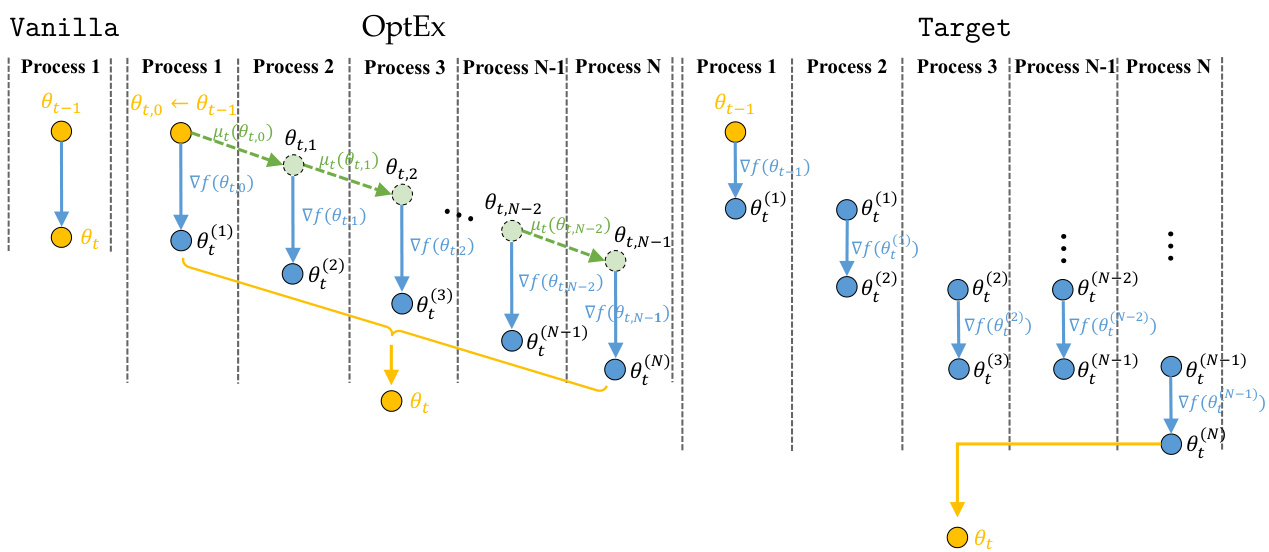

🔼 This figure illustrates the OptEx framework at a given iteration t. It shows the parallel processes involved in approximating the gradients using the kernelized gradient estimation and subsequently using these gradients to execute the standard FOO algorithms in parallel. Process 1 begins with the previous iteration’s result (θt-1). Each process involves using the kernelized gradient estimation, applying the FO-OPT algorithm, sampling f to evaluate the gradient, and updating the history of gradients. The output of the last process in the parallel loop is taken to be the input for the next iteration.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of OptEx at iteration t.

In-depth insights#

OptEx Framework#

The OptEx framework presents a novel approach to accelerate first-order optimization (FOO) by enabling approximate parallelization of iterations. Its core innovation lies in kernelized gradient estimation, using historical gradient data to predict future gradients, thereby breaking the inherent sequential dependency in FOO algorithms. This allows for multiple iterations to be computed concurrently, significantly speeding up convergence. Theoretical analysis provides bounds on the estimation error and iteration complexity, showing a potential acceleration rate proportional to the square root of the number of parallel processes. Empirical results across synthetic functions, reinforcement learning, and neural network training demonstrate substantial efficiency improvements compared to standard FOO methods. While promising, limitations include the computational cost of kernelized estimation and the assumption of gradient data following a specific Gaussian process. Further investigation could explore alternative gradient estimation techniques and relax these assumptions to broaden the applicability of OptEx.

Kernel Estimation#

Kernel estimation, in the context of a research paper likely focusing on machine learning or a related field, would involve a discussion of methods used to estimate probability density functions or regression functions using kernel functions. A key aspect is the choice of kernel, which impacts smoothness and computational cost. Bandwidth selection, a crucial parameter in kernel density estimation, affects the level of detail captured. The paper might delve into the bias-variance tradeoff, showing how different kernels and bandwidths lead to varying degrees of overfitting or underfitting. Theoretical properties of kernel estimators, such as consistency and convergence rates, would be of interest. Furthermore, the research might address computational efficiency and scalability in applying these methods to large datasets, possibly comparing different kernel estimation techniques in terms of computational complexity and accuracy. Applications of kernel estimation within the broader research topic would also be detailed, highlighting its practical uses. The overall goal is to present a clear understanding of kernel estimation techniques, their properties, and their relevance to the paper’s central research question.

Parallel Iterations#

The concept of “Parallel Iterations” in optimization algorithms represents a significant advancement, aiming to overcome the inherent sequential nature of many methods. Traditional iterative algorithms process each iteration before starting the next, creating a bottleneck. Parallel iterations seek to bypass this dependency by simultaneously executing multiple iterations. This can be achieved using techniques like kernelized gradient estimation that predict future gradients, enabling approximate parallelization. However, challenges remain. Accurate gradient estimation is crucial for the validity of parallel iterations, and the approach’s effectiveness depends heavily on the specific problem and the choice of parallelization strategy. Furthermore, computational overhead associated with gradient prediction and parallel execution needs careful consideration, as it could offset the benefits of parallelization. Future work should explore ways to balance accuracy, efficiency, and scalability to maximize the impact of parallel iterations across various optimization domains.

Theoretical Bounds#

A section on “Theoretical Bounds” in a research paper would ideally present rigorous mathematical analyses to quantify the performance guarantees of proposed methods. It would likely involve deriving upper and lower bounds on key metrics, such as error rates or convergence times, under specific assumptions. These bounds would provide a theoretical understanding of the algorithm’s efficiency and robustness, independent of empirical results. The derivation of these bounds is crucial for establishing the algorithm’s theoretical properties and comparing it to existing methods. A strong theoretical analysis is vital for building confidence in the proposed algorithm’s efficacy and providing insights into its limitations. The assumptions made during the derivation of the bounds should be clearly stated and their implications discussed. The presence of both upper and lower bounds is particularly important; tight bounds provide a more precise characterization of the algorithm’s behavior. A high-quality section should clearly explain the significance of the bounds in the context of the larger research goals, thus enabling a more meaningful evaluation of its contribution.

Future of OptEx#

The future of OptEx hinges on addressing its current limitations and expanding its capabilities. Improving the efficiency of the kernelized gradient estimation is crucial, perhaps through exploring more sophisticated kernel functions or leveraging advanced machine learning techniques for gradient prediction. Reducing the computational and memory overhead, especially for high-dimensional problems, is another key area. Extending OptEx to handle a broader range of optimization problems, beyond those currently tested, including non-convex and constrained optimization, would significantly increase its practical value. Furthermore, integrating OptEx with other optimization techniques could yield hybrid approaches with enhanced performance. Finally, thorough investigation of the optimal parallelisation strategy and its interaction with other algorithmic parameters will be essential to maximize the efficiency gains. Ultimately, the success of OptEx will depend on its ability to deliver significant speedups in real-world applications, demonstrating its value over existing, well-established methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the OptEx framework at iteration t. It shows how, unlike standard first-order optimization methods, OptEx uses a kernelized gradient estimation to predict gradients for multiple iterations. This enables parallel processing of these iterations (represented by the parallel processes 1 through N). The output of each parallel process is used to refine the gradient estimation and inform the next set of parallel iterations. The ultimate outcome is a final parameter update θt at the end of iteration t. This approach improves efficiency by approximating parallelization of inherently sequential steps.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of OptEx at iteration t.

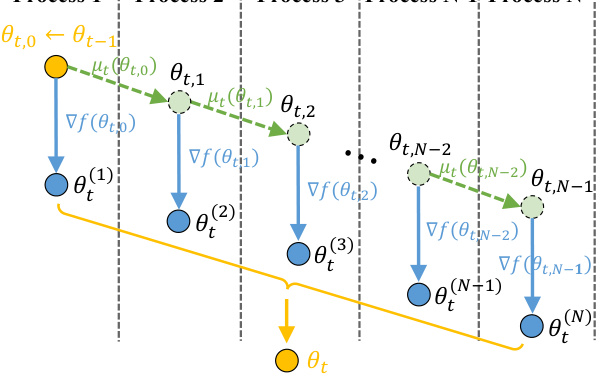

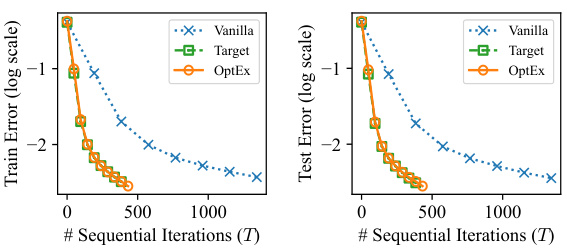

🔼 This figure compares the number of sequential iterations needed to achieve a certain optimality gap for four different synthetic functions using three different optimization methods: Vanilla (standard FOO), Target (idealized parallelized FOO), and OptEx (the proposed method). The x-axis represents the number of sequential iterations, and the y-axis shows the optimality gap. The parallelism (N) is set to 5 for all methods. Each data point is the average of 5 independent runs. The figure demonstrates that OptEx significantly reduces the number of iterations compared to the Vanilla method, approaching the performance of the idealized Target method.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the number of sequential iterations T (x-axis) required by different methods to achieve the same optimality gap F(θ) – infθ F(θ) (y-axis) for various synthetic functions. The parallelism N is set to 5 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 independent runs.

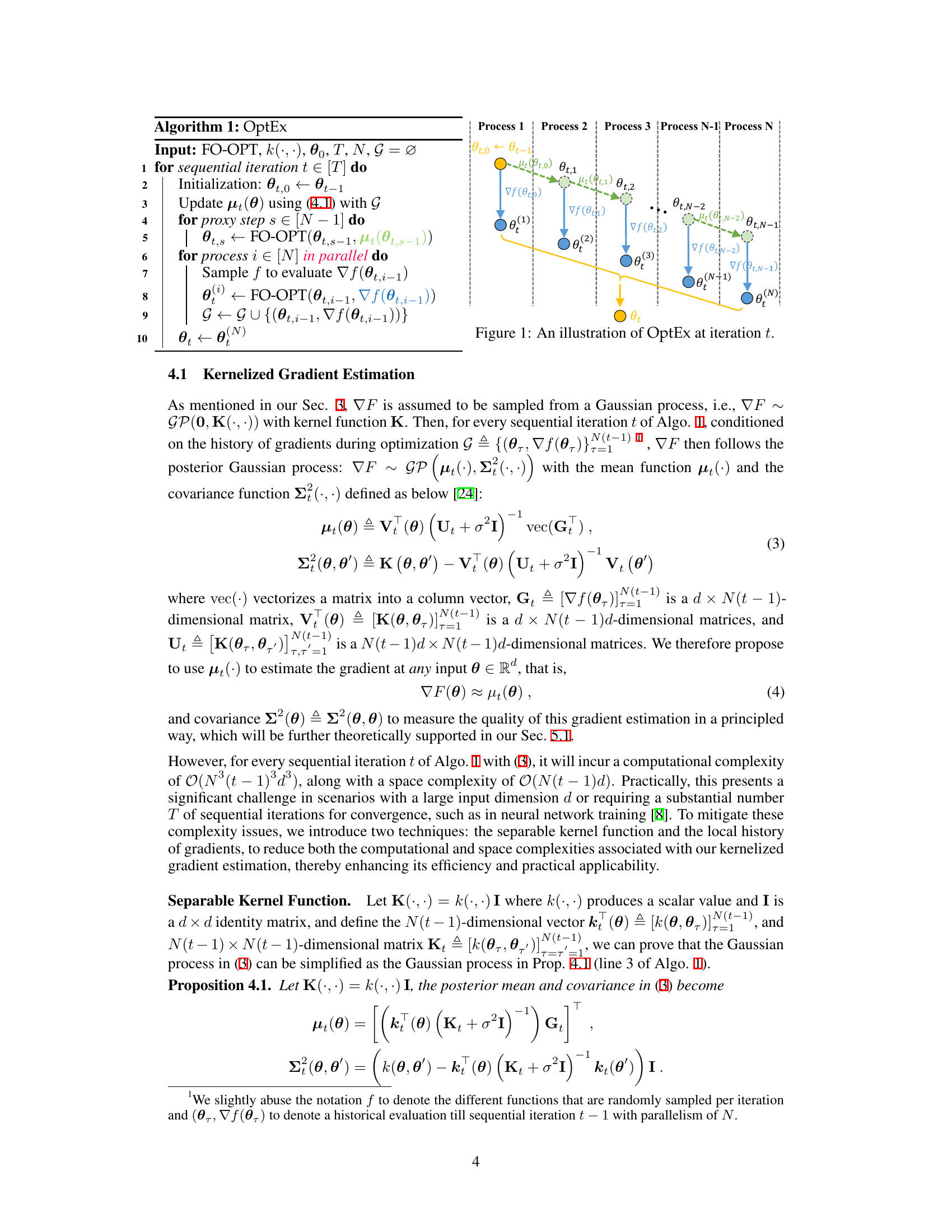

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Vanilla, Target, and OptEx in training Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) on four different reinforcement learning tasks from the OpenAI Gym suite. The y-axis represents the cumulative average reward, while the x-axis shows the number of sequential iterations (episodes). Each task has a different parameter dimension (d), indicated in the title of each subplot. The parallelism (N) is fixed at 4 for all methods, and each data point is the mean reward over 3 independent runs. OptEx consistently outperforms Vanilla and performs comparably to Target (which has access to perfect gradient information, but is unrealistic in a real-world setting). This demonstrates OptEx’s ability to improve the efficiency of reinforcement learning.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of the cumulative average reward (y-axis) achieved by different methods to train DQN on RL tasks under various parameter dimension d and a varying number of sequential episodes T (x-axis). The parallelism N is set to 4 and each curve denotes the mean from 3 independent runs.

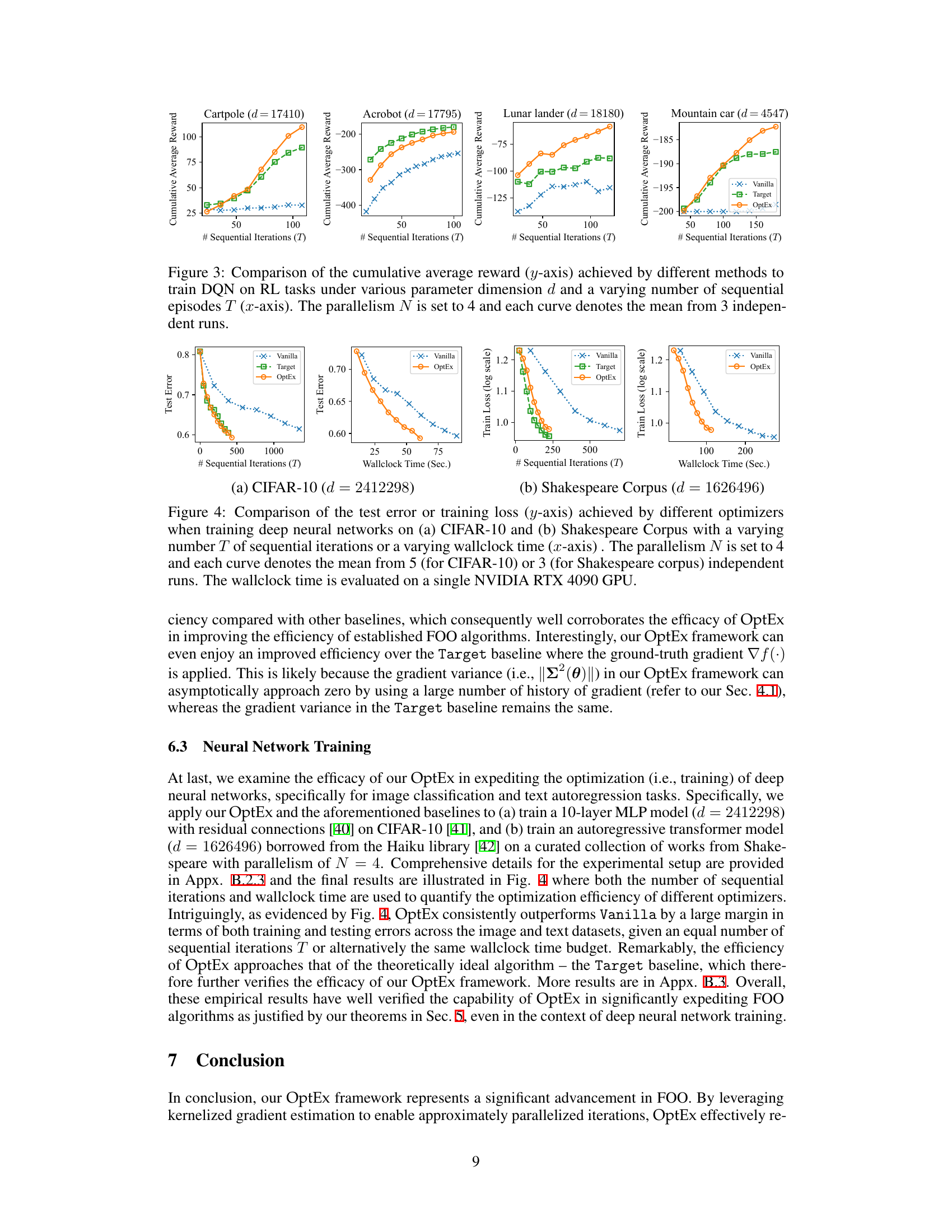

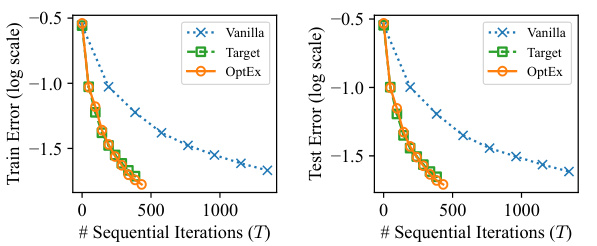

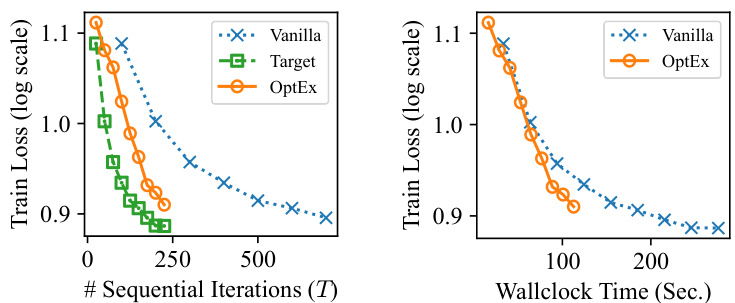

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Vanilla, Target, and OptEx optimizers on CIFAR-10 and Shakespeare Corpus datasets. It shows test error and training loss (log scale) against sequential iterations and wall-clock time. Parallelism (N) is fixed at 4. The results highlight OptEx’s efficiency in reducing the number of iterations needed for convergence compared to Vanilla, performing comparably to the ideal Target method.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of the test error or training loss (y-axis) achieved by different optimizers when training deep neural networks on (a) CIFAR-10 and (b) Shakespeare Corpus with a varying number T of sequential iterations or a varying wallclock time (x-axis). The parallelism N is set to 4 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 (for CIFAR-10) or 3 (for Shakespeare corpus) independent runs. The wallclock time is evaluated on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

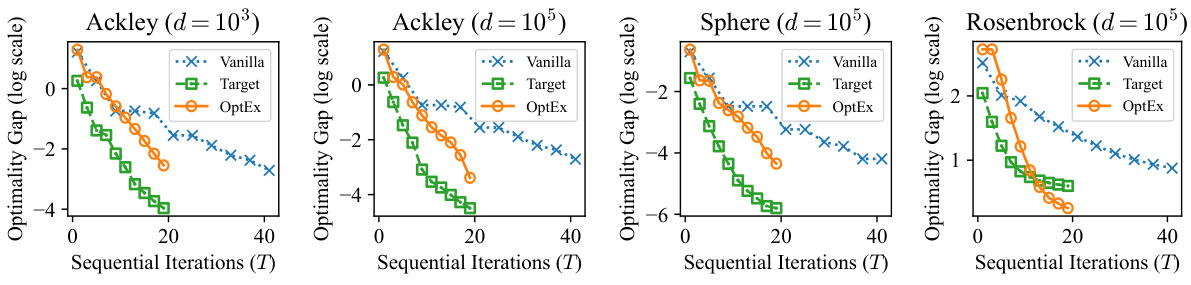

🔼 This figure illustrates the OptEx framework at a given iteration t. It compares three approaches: Vanilla, OptEx, and Target. Vanilla represents the standard sequential first-order optimization. OptEx introduces approximate parallelization by using a kernelized gradient estimation to predict future gradients, allowing parallel computation of multiple steps. The Target approach is an ideal (but impractical) version where perfectly parallel updates are possible using true gradients. The figure shows how OptEx aims to bridge the gap between the efficiency of perfectly parallel updates (Target) and the efficiency of standard, sequential optimization (Vanilla).

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of OptEx at iteration t.

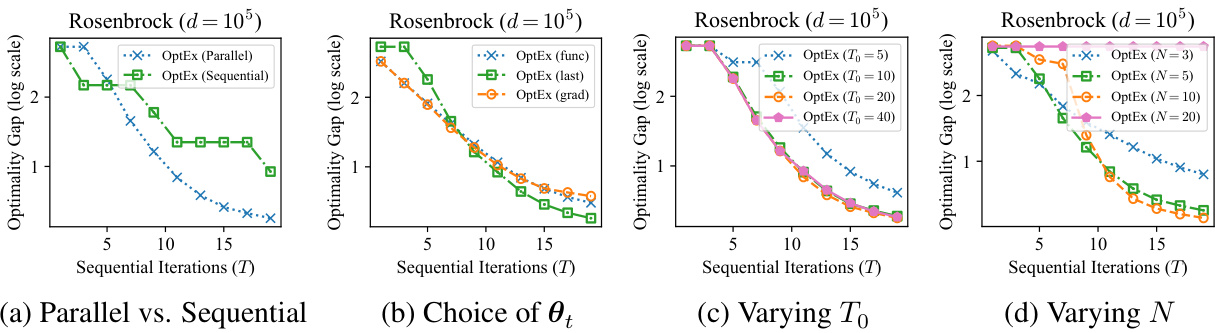

🔼 This figure presents four ablation studies on the Rosenbrock synthetic function. (a) compares the parallel and sequential versions of OptEx, demonstrating the effect of parallel processing. (b) illustrates how different methods of selecting the next input (θt) impact performance. (c) shows the sensitivity of OptEx to the length of the local gradient history (To), and (d) explores the effect of varying the level of parallelism (N). Each subplot shows the optimality gap (y-axis) plotted against the number of sequential iterations (T) required to achieve that gap.

read the caption

Figure 6: Ablation studies on the Rosenbrock synthetic function.

🔼 This figure compares the number of sequential iterations needed by Vanilla, Target, and OptEx methods to reach the same level of optimality for various synthetic functions. The x-axis represents the number of sequential iterations (T), and the y-axis represents the optimality gap (F(θ) - info F(θ)). OptEx consistently requires fewer iterations than Vanilla, demonstrating its improved efficiency, although it does not quite reach the ideal performance of the Target method which leverages perfect gradient information.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the number of sequential iterations T (x-axis) required by different methods to achieve the same optimality gap F(θ) – info F(θ) (y-axis) for various synthetic functions. The parallelism N is set to 5 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 independent runs.

🔼 This figure compares the number of sequential iterations needed by Vanilla, Target, and OptEx methods to reach the same optimality gap for four different synthetic functions (Ackley, Ackley (higher dimension), Sphere, and Rosenbrock). The x-axis represents the number of sequential iterations (T), and the y-axis represents the optimality gap. OptEx consistently requires fewer iterations than Vanilla, demonstrating its improved efficiency. The parallelism (N) is fixed at 5 for all experiments. Each data point is an average across 5 independent runs.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the number of sequential iterations T (x-axis) required by different methods to achieve the same optimality gap F(θ) – infθ F(θ) (y-axis) for various synthetic functions. The parallelism N is set to 5 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 independent runs.

🔼 This figure compares the number of sequential iterations needed by different optimization methods (Vanilla, Target, and OptEx) to achieve a similar optimality gap on various synthetic functions. OptEx significantly reduces the number of iterations compared to Vanilla, showcasing its efficiency. The Target line represents an ideal scenario with perfect parallelization, providing an upper bound for OptEx’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the number of sequential iterations T (x-axis) required by different methods to achieve the same optimality gap F(θ) – info F(θ) (y-axis) for various synthetic functions. The parallelism N is set to 5 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 independent runs.

🔼 This figure compares the number of sequential iterations needed by Vanilla, Target, and OptEx to reach a specific optimality gap for four different synthetic functions (Ackley, Ackley with higher dimensions, Sphere, and Rosenbrock). OptEx consistently requires fewer iterations than Vanilla, demonstrating its efficiency improvement. Although OptEx doesn’t quite match the ideal Target (which uses perfect gradient information), it achieves a significant reduction in iterations, supporting the claims of approximate parallelization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the number of sequential iterations T (x-axis) required by different methods to achieve the same optimality gap F(θ) – info F(θ) (y-axis) for various synthetic functions. The parallelism N is set to 5 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 independent runs.

🔼 This figure presents ablation studies conducted on the Rosenbrock synthetic function to analyze different aspects of the OptEx algorithm. Panel (a) compares the performance of OptEx using parallel vs. sequential iterations. Panel (b) investigates the impact of different selection methods for choosing proxy updates. Panel (c) explores the effect of varying the size of the local gradient history (To). Panel (d) examines the influence of varying the level of parallelism (N). The results help demonstrate the effectiveness of using intermediate gradient calculations and illustrate the optimal settings of certain parameters in the algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 6: Ablation studies on the Rosenbrock synthetic function.

🔼 This figure compares the number of sequential iterations needed by Vanilla, Target, and OptEx to achieve a similar optimality gap on four different synthetic functions. OptEx consistently requires fewer iterations, demonstrating its efficiency improvement. The parallelism (N) was set to 5.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the number of sequential iterations T (x-axis) required by different methods to achieve the same optimality gap F(θ) – info F(θ) (y-axis) for various synthetic functions. The parallelism N is set to 5 and each curve denotes the mean from 5 independent runs.

Full paper#