TL;DR#

Current demand-driven navigation (DDN) research often simplifies real-world scenarios by focusing on single-object searches and ignoring individual preferences. This limitation restricts the development of more realistic and versatile embodied AI systems. The paper addresses this gap by introducing a new benchmark, MO-DDN, which incorporates multi-object search and user-specific preferences. This enhanced benchmark better mirrors the complexity of human needs and behaviors.

To tackle the challenges in MO-DDN, the researchers propose a novel modular method called C2FAgent that employs a coarse-to-fine attribute-based exploration strategy. Their experiments show that this approach significantly improves performance compared to simpler methods. The modular design effectively leverages the benefits of attributes at multiple decision-making stages, resulting in superior navigation efficiency and a more human-like robot behavior. This work significantly advances the field of embodied AI task planning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a new benchmark, MO-DDN, addressing limitations of existing datasets in demand-driven navigation. It proposes a novel coarse-to-fine exploration agent, improving efficiency and reflecting real-world scenarios better. This opens avenues for researching more complex and nuanced task planning in embodied AI.

Visual Insights#

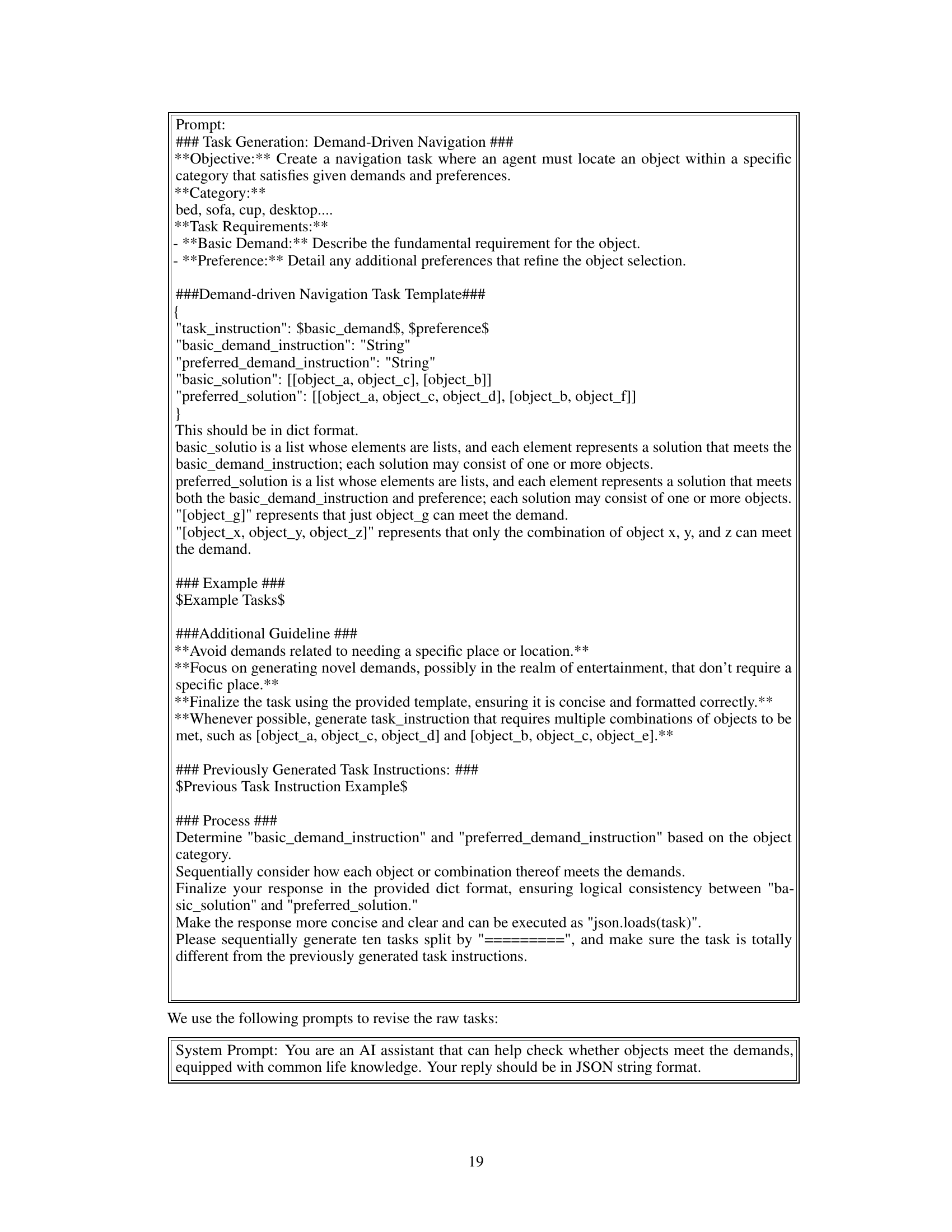

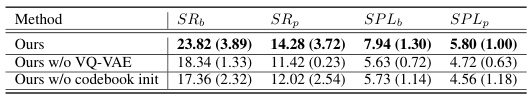

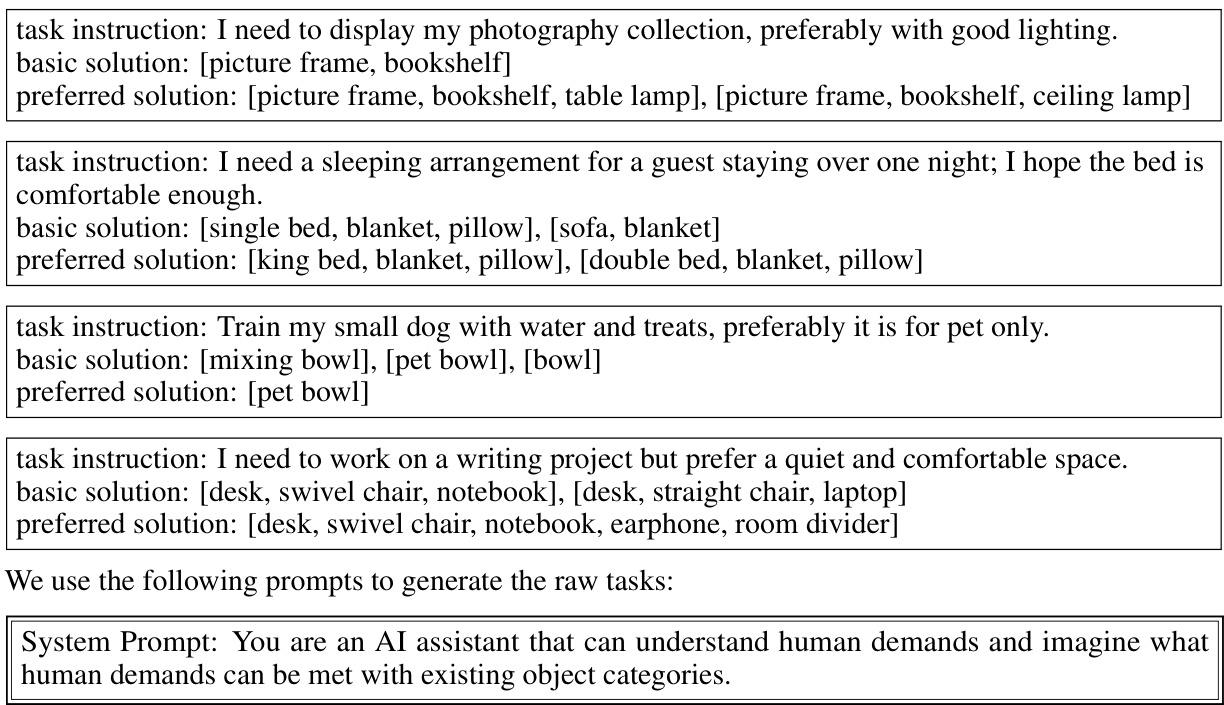

🔼 This figure illustrates an example of a multi-object demand-driven navigation scenario. A user is planning a party and has several demands, including basic needs (e.g., food, seating) and individual preferences (e.g., type of food). The agent must locate multiple objects to fulfill these demands. The visualization shows the house layout, object locations, user demands, and the agent’s trajectory as it collects the required items. The example highlights that while the agent may not satisfy all preferences, it can still successfully address the fundamental demands of the situation.

read the caption

Figure 1: An Example of Multi-object Demand-driven Navigation. A user plans to host a party at his new house and outlines some basic demands (highlighted in orange), along with specific preferences for different individuals (highlighted in red). The agent parses these demands and locates multiple objects in various locations in the scene to fulfill them. Despite not meeting the preferred 'ice cream' demand, the agent successfully addresses basic demands, such as organizing lunch.

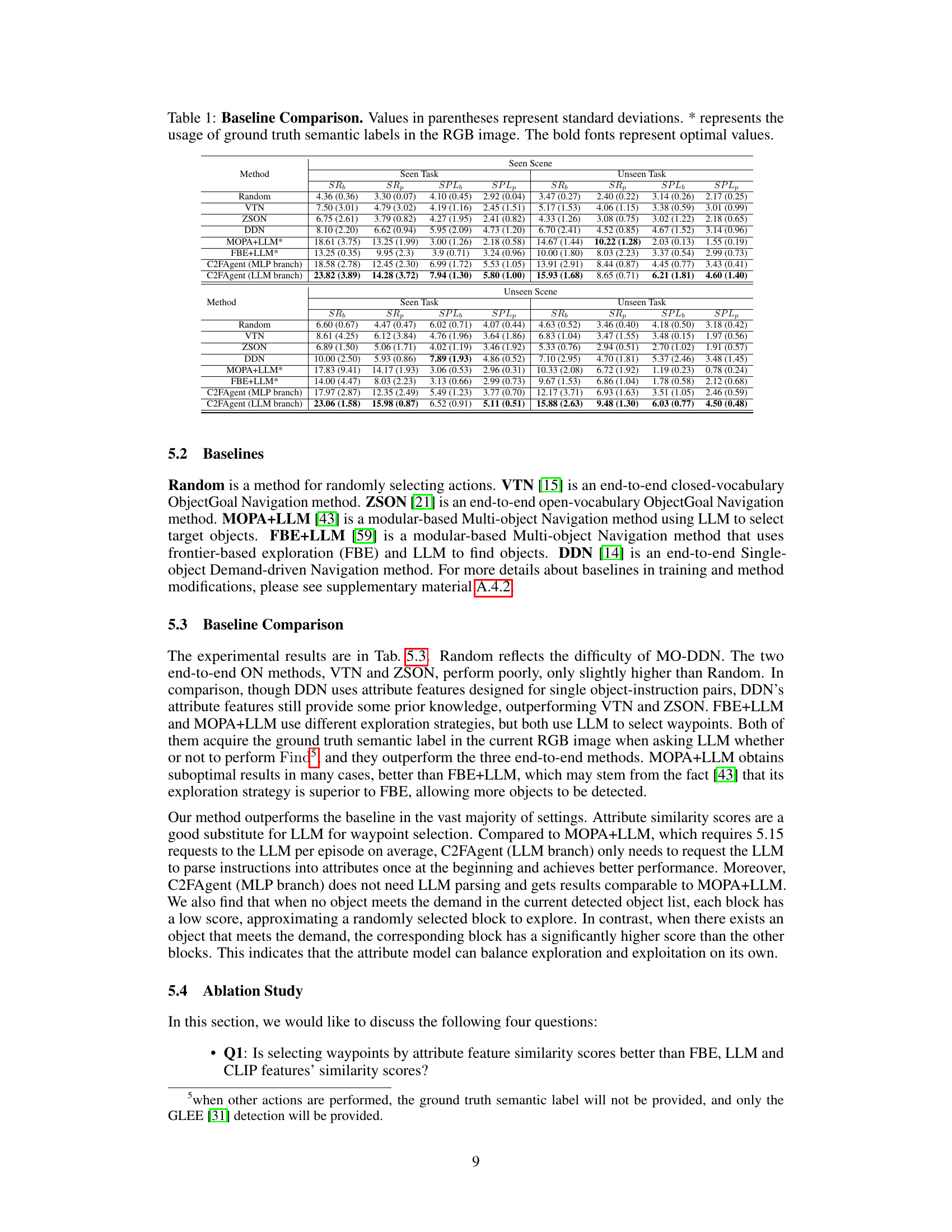

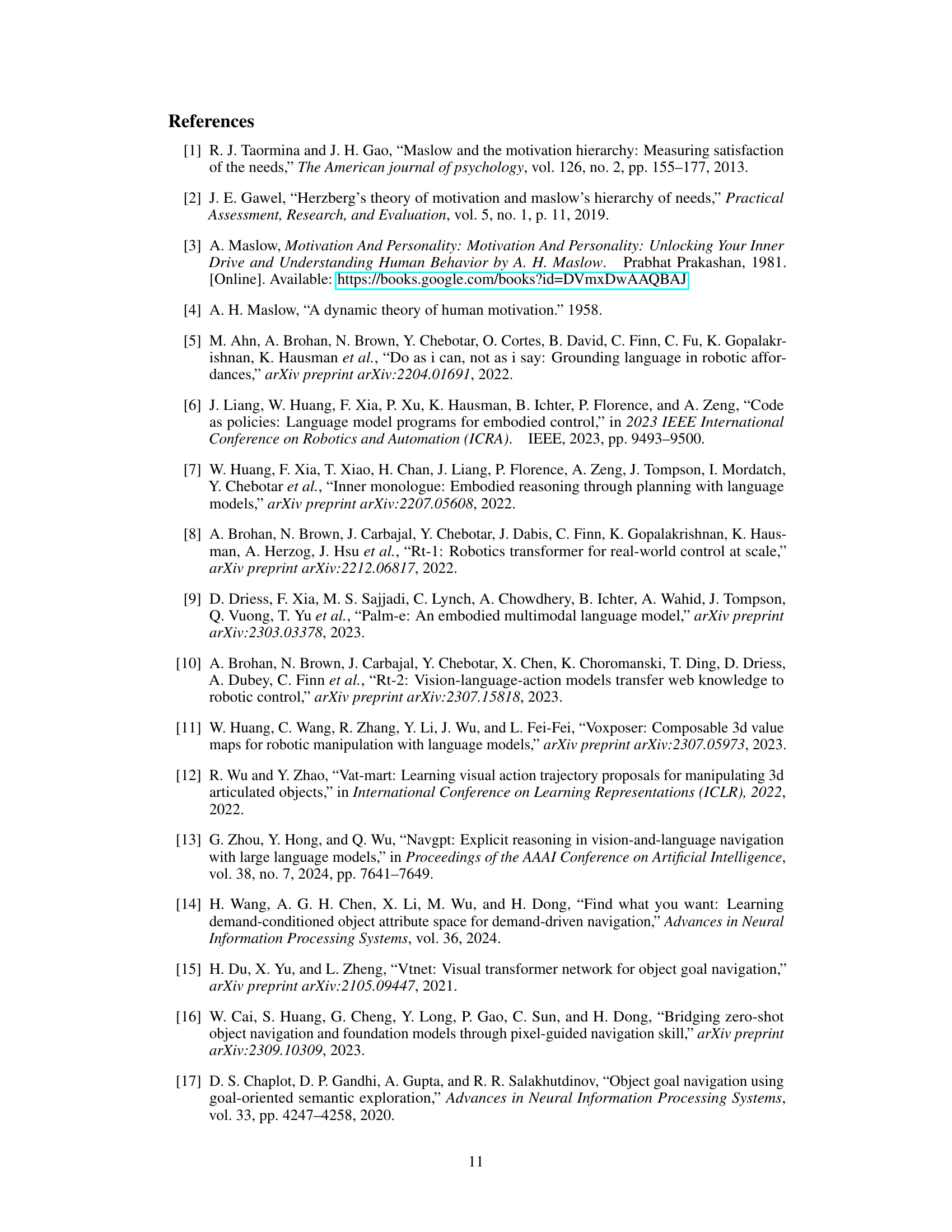

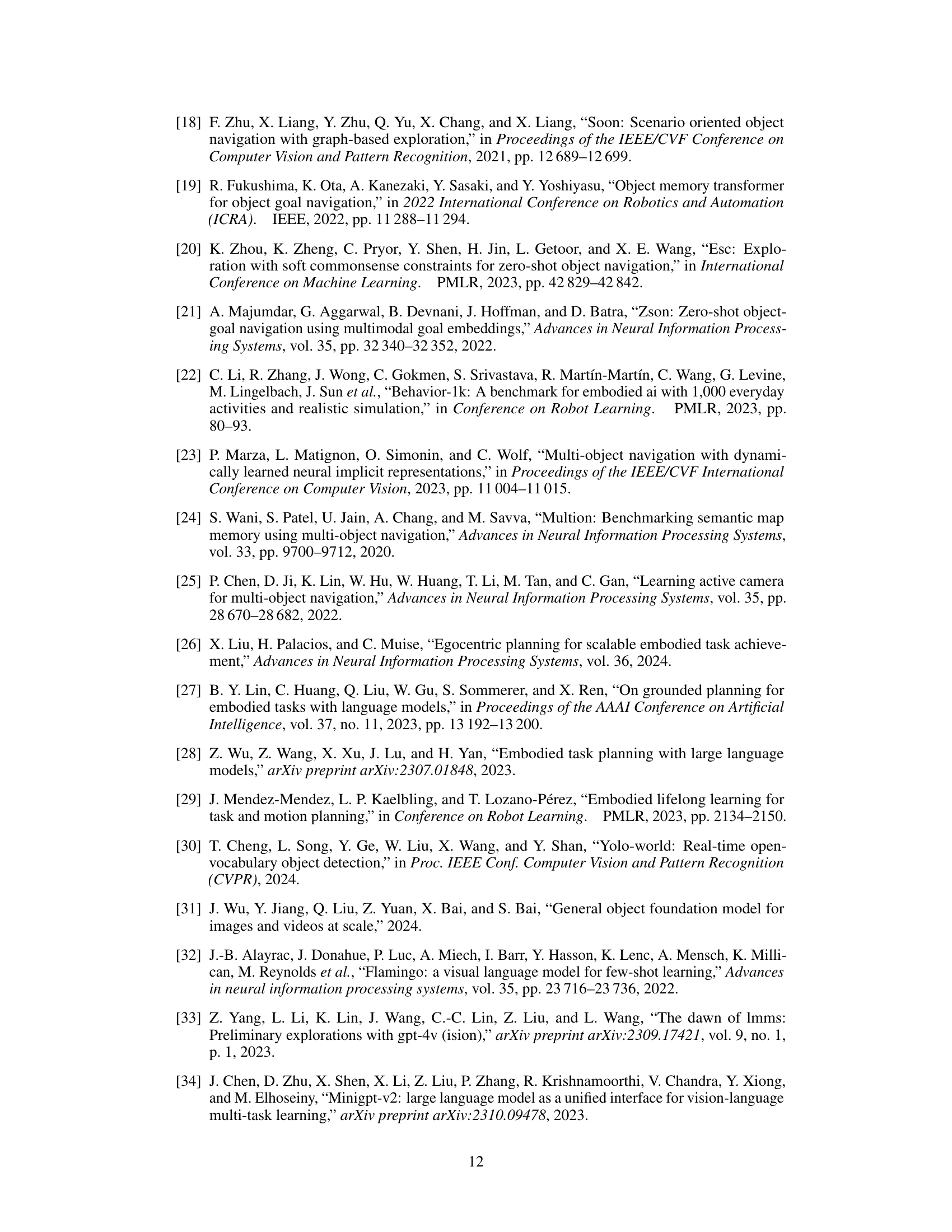

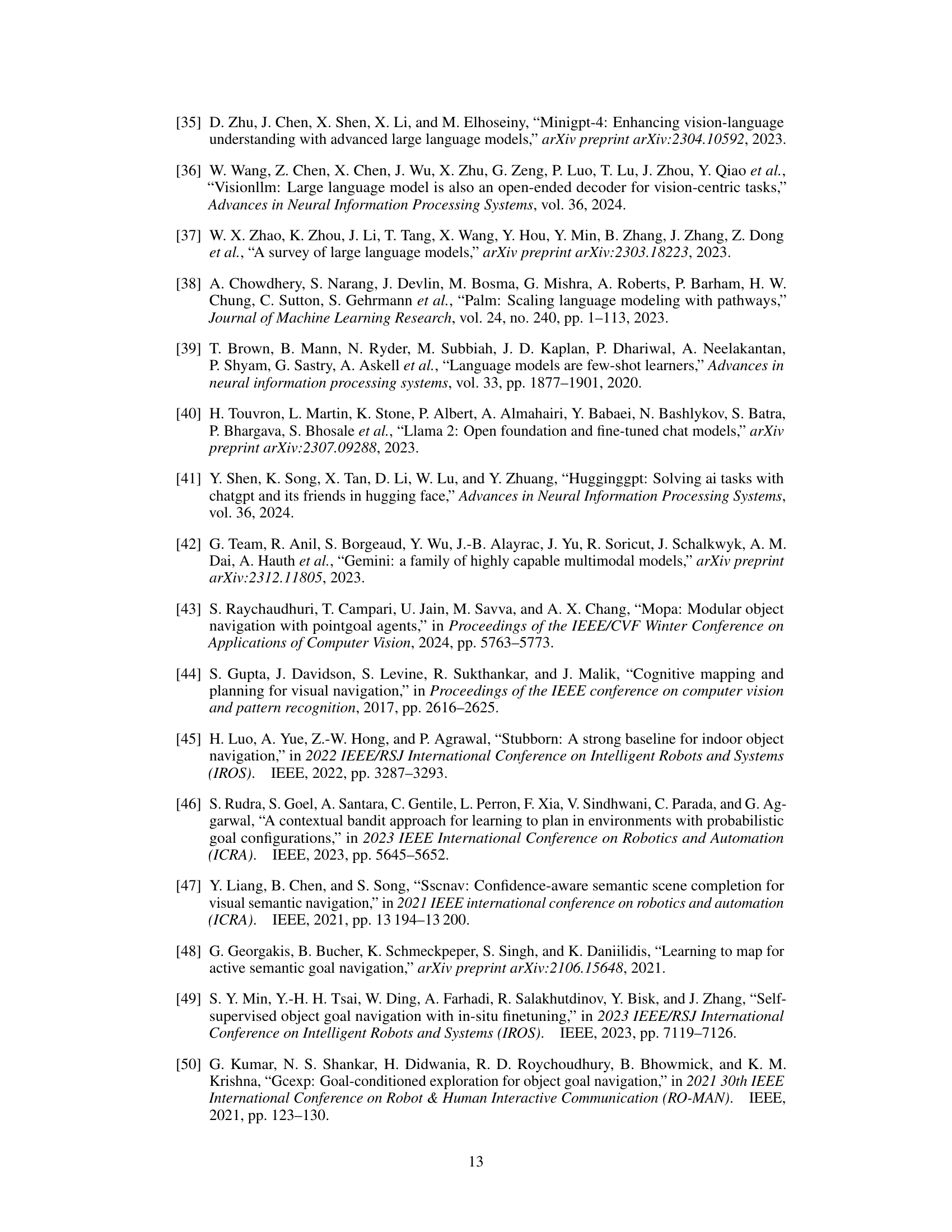

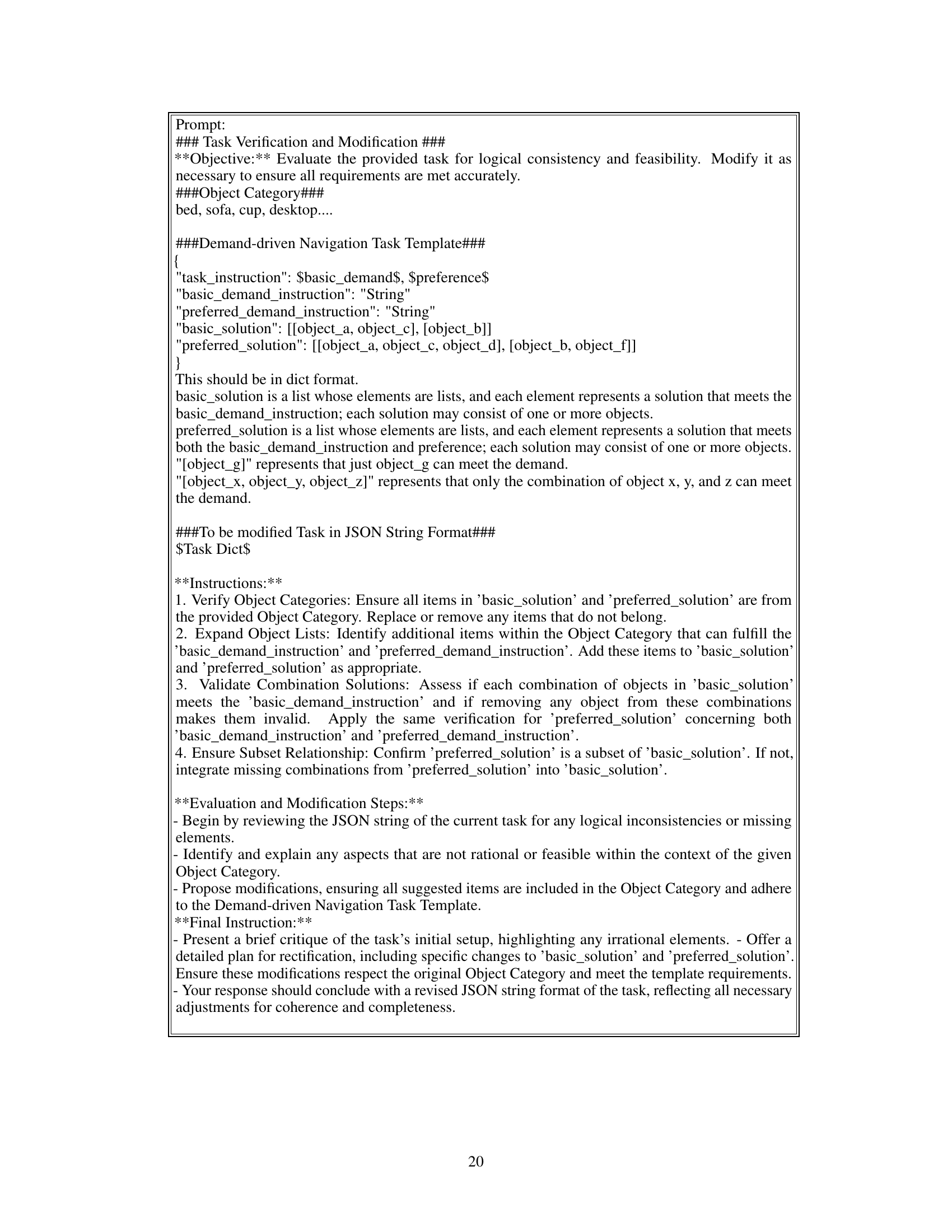

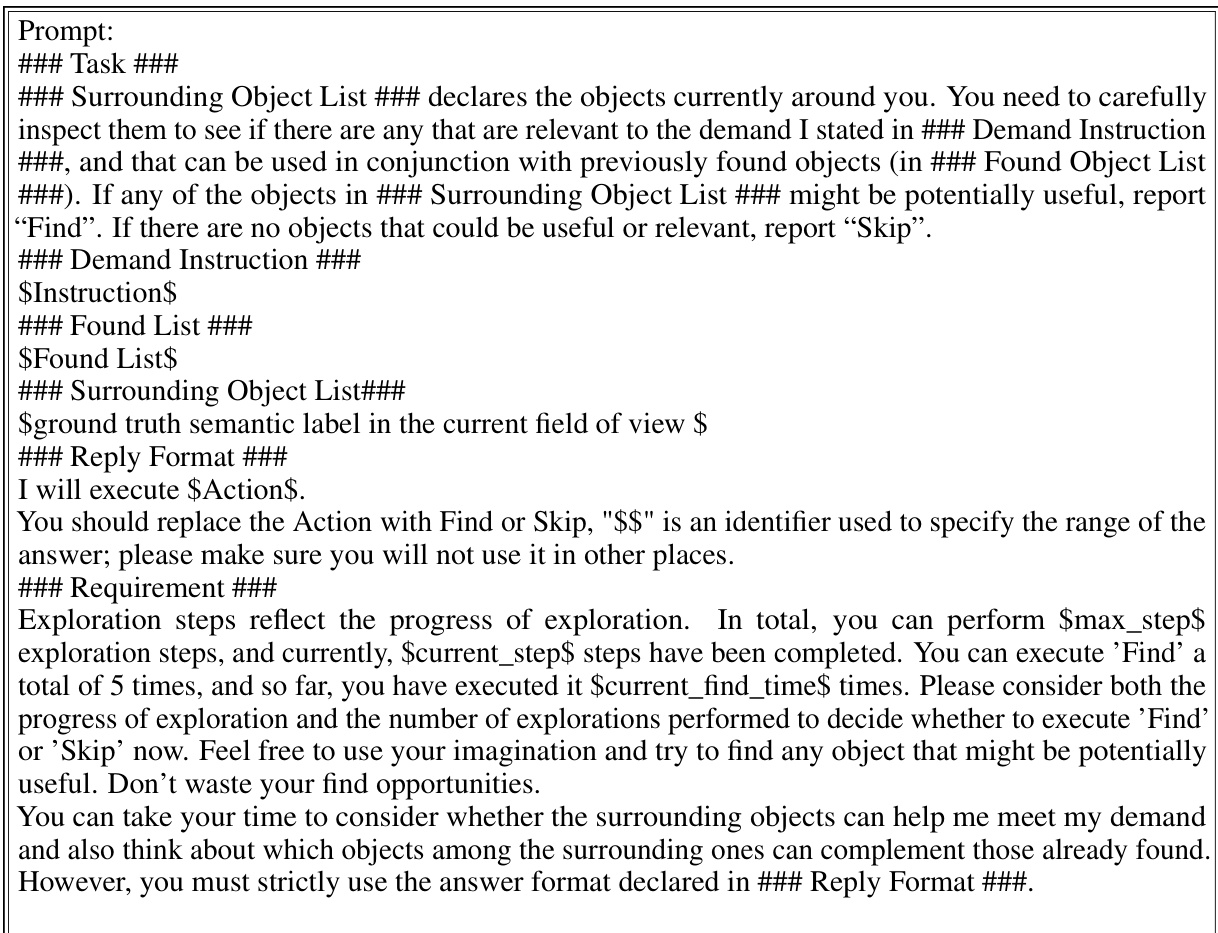

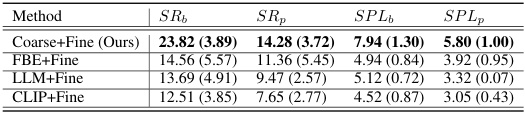

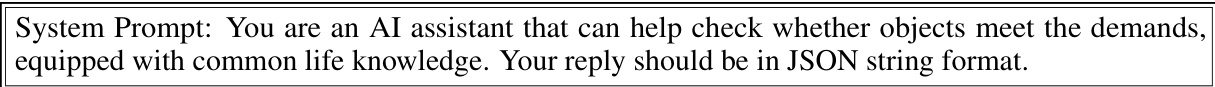

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The performance metrics include success rate for basic (SRb) and preferred (SRp) demands, and the success rate penalized by path length (SPLb and SPLp). The results are shown for both seen and unseen tasks and scenes, highlighting the model’s robustness and ability to handle different scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

In-depth insights#

MO-DDN Benchmark#

The proposed MO-DDN benchmark represents a significant advancement in embodied AI, addressing limitations of existing Demand-Driven Navigation (DDN) tasks. Its core innovation lies in incorporating multi-object scenarios and user preferences, moving beyond the single-object assumption of previous DDN benchmarks. This increased complexity makes MO-DDN a more realistic and challenging assessment of an agent’s ability to satisfy complex, nuanced human demands. The inclusion of personal preferences adds a further layer of difficulty, requiring agents to prioritize objectives based on user-specified priorities. The benchmark’s design promotes a more holistic evaluation of an agent’s decision-making capabilities in dynamic, real-world contexts. By addressing the gaps of previous DDN benchmarks, MO-DDN pushes the field towards the development of more robust and adaptable embodied AI agents, capable of handling the complexities of daily human interactions.

C2FAgent Design#

The C2FAgent design is a modular, coarse-to-fine approach to multi-object demand-driven navigation. It leverages attributes to bridge symbolic reasoning with embodied AI, unlike purely end-to-end methods. The coarse phase utilizes a depth camera and object detection to identify objects and their spatial context, creating a high-level representation. This allows the agent to prioritize promising areas by assessing attribute similarity between objects and the user demand. The fine phase utilizes an end-to-end exploration module trained via imitation learning, enabling granular object identification to fulfill the demand instruction. Modularity makes this design robust and flexible, allowing incorporation of different object detection models and path planning algorithms. The weighted sum of basic and preferred demand similarities provides a flexible approach to handle varying user preferences, making C2FAgent more adaptable to real-world scenarios than previous approaches that focus only on single-object demands.

Attribute-Based Exploration#

Attribute-based exploration, in the context of embodied AI navigation, offers a powerful paradigm shift from traditional methods. Instead of relying solely on raw sensory data or predefined maps, it leverages the semantic understanding of objects through their attributes. This allows agents to make more informed decisions during navigation, prioritizing objects relevant to a given task or goal. Attributes act as high-level features; for example, instead of simply locating a ‘red object’, an attribute-based system might search for something ‘drinkable’ or ’edible’, which then helps to locate a relevant object like a water bottle or an apple. This approach is particularly beneficial in complex or partially known environments where reasoning about object properties becomes crucial. The modularity of attribute-based exploration is an added advantage, allowing for easier integration of other AI components, such as language processing modules which translate user requests into desired attribute specifications. However, challenges remain in defining relevant attributes and handling attribute ambiguity, and also the computational cost associated with complex attribute reasoning must be addressed.

Multi-Object Challenges#

Multi-object scenarios present significant challenges compared to single-object tasks. Increased complexity in planning and decision-making arises from the need to coordinate multiple objects, considering their interactions, dependencies, and potential conflicts. Reasoning about object relationships becomes crucial; an agent must understand which objects are relevant to a given task and how they work together to form a solution. Uncertainty in object location and availability also increases the difficulty, requiring robust exploration and search strategies. Furthermore, handling diverse user preferences adds another layer of complexity, demanding the ability to adapt to individual needs and priorities. Addressing these challenges requires advances in reasoning, planning, and execution capabilities for AI agents.

Future of MO-DDN#

The future of MO-DDN (Multi-object Demand-Driven Navigation) is bright, with potential advancements in several key areas. Improved robustness is crucial; current systems struggle with diverse environments and unexpected situations. Future work should focus on developing more flexible and adaptable agents capable of handling varied user preferences and complex scenarios. Enhanced reasoning capabilities are also needed, enabling agents to understand nuanced instructions and coordinate multiple object interactions effectively. The integration of advanced language understanding models and more sophisticated planning algorithms will enable agents to generate more robust and efficient plans for fulfilling multi-object demands. Finally, incorporating real-world constraints, such as object manipulation and human-robot interaction, will be critical in moving MO-DDN from a research benchmark towards practical application in areas like smart home assistance and service robotics.

More visual insights#

More on figures

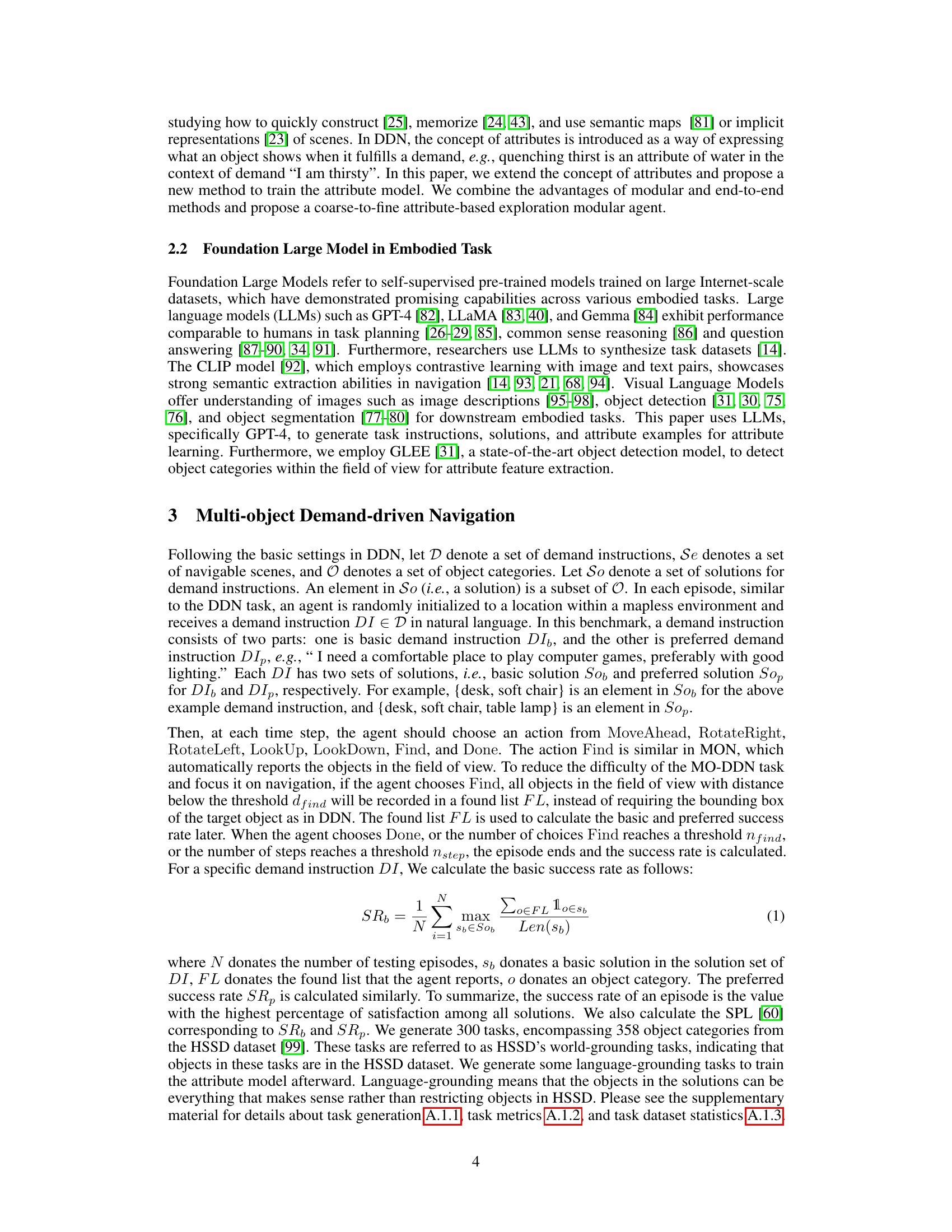

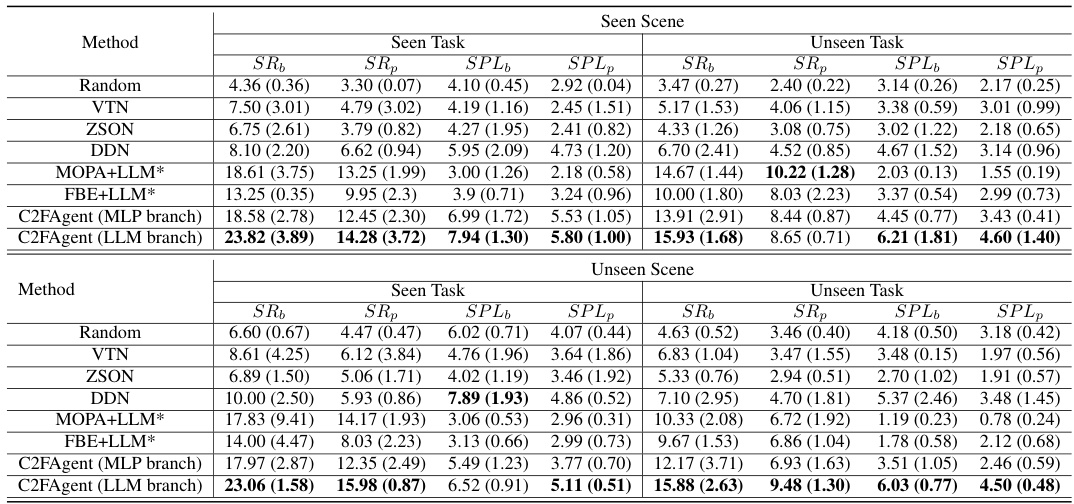

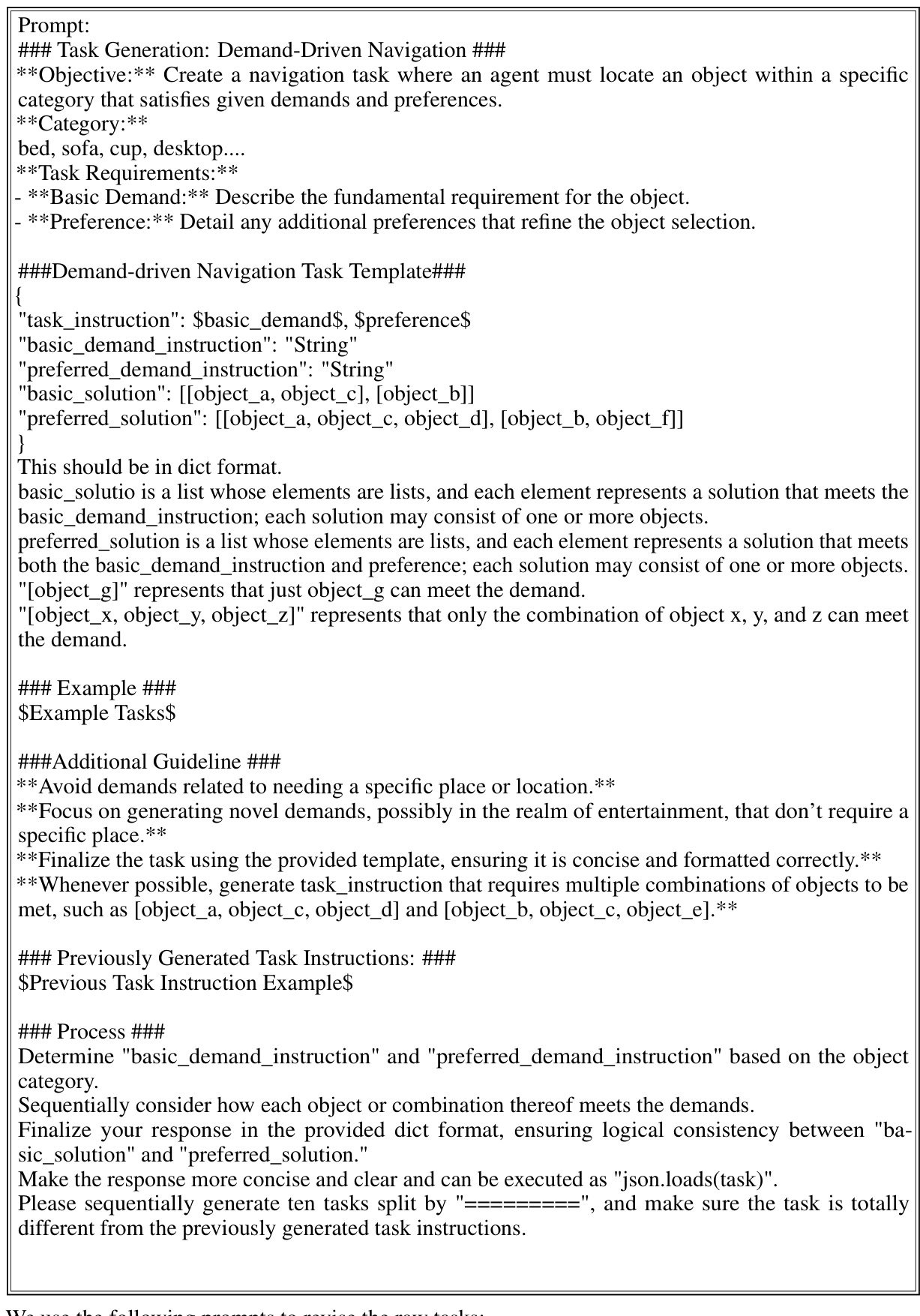

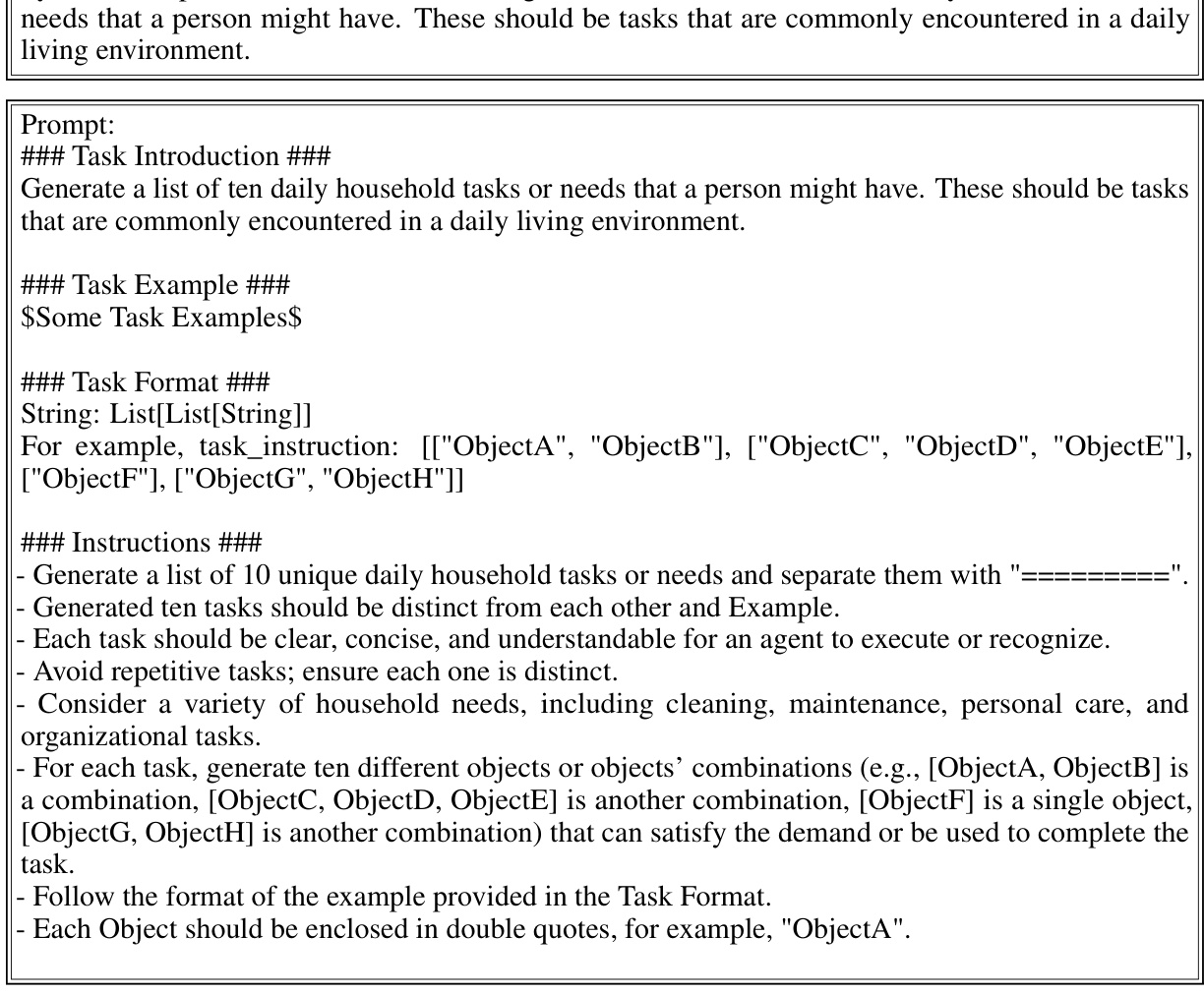

🔼 This figure presents the architecture of the attribute model used in the MO-DDN system. The model processes both instructions and object information through a shared pathway to generate attribute features. It uses a CLIP model (frozen) for initial feature extraction, then an MLP encoder to generate the attribute features. These features are then quantized using a codebook (the parameters of which are shared between the instruction and object processing branches). An MLP decoder reconstructs the features, and several loss functions compare the original features with the reconstructed and quantized features, as well as matching instructions with objects. The diagram highlights that only specific parts of the model (those in red) are trained during the process.

read the caption

Figure 2: Attribute Model. This figure shows the architecture of the attribute model. Instructions and objects share the same model architecture. Instructions and items share the same model architecture. For parameters, they share only the parameters of the shared codebook, while the parameters of the MLP Encoder and Decoder are independent. Only the red with flames modules in the figure will be trained while the blue with snowflakes CLIP model parameters will be frozen.

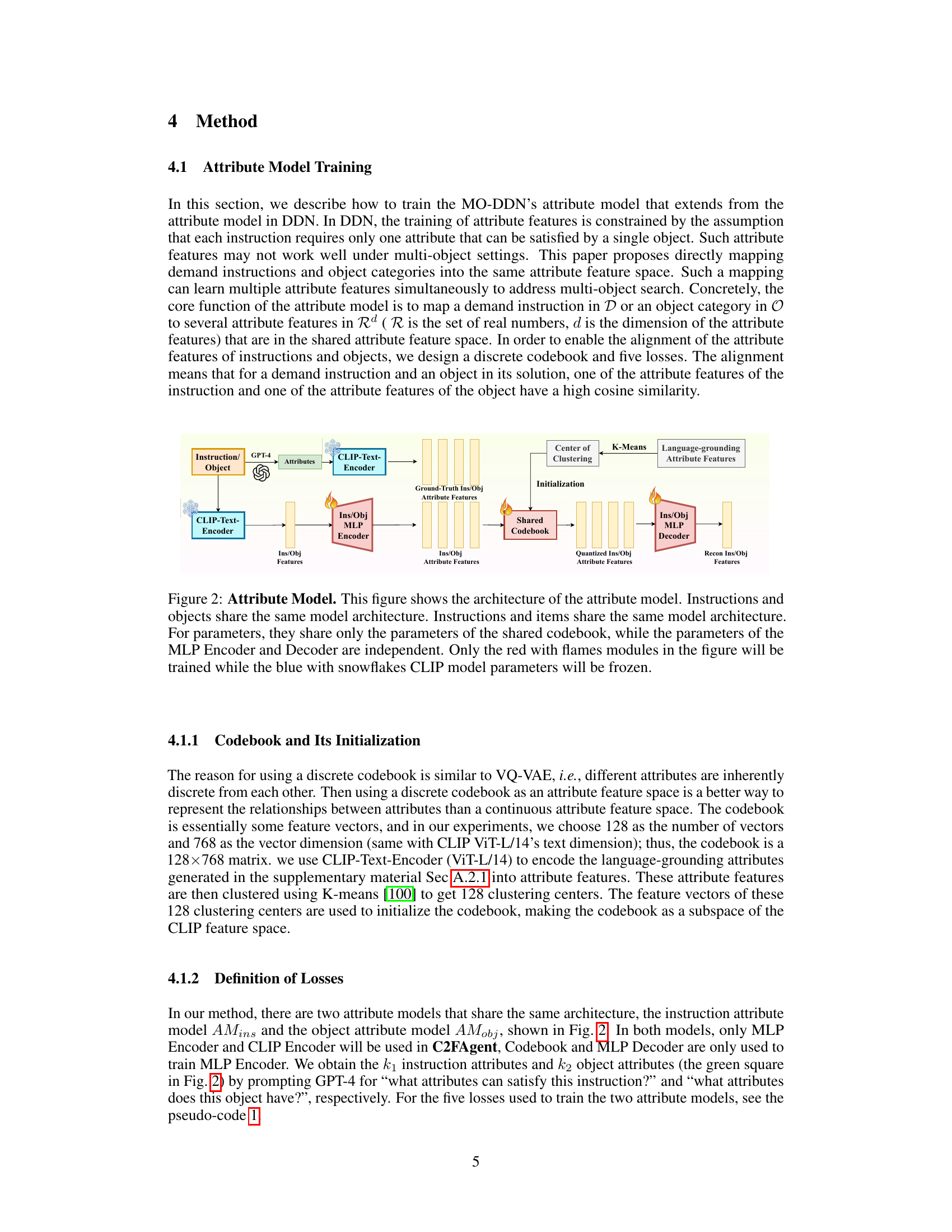

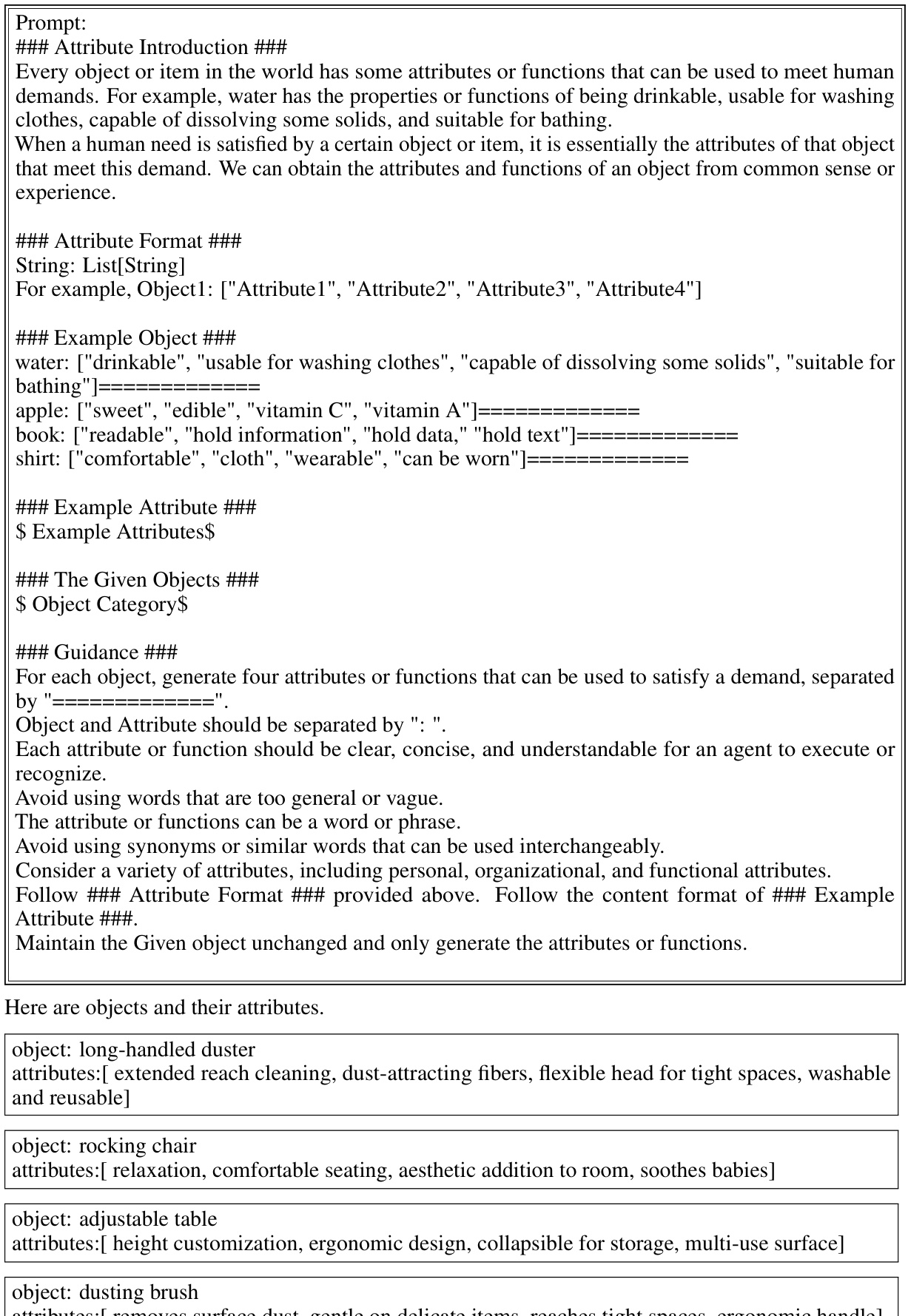

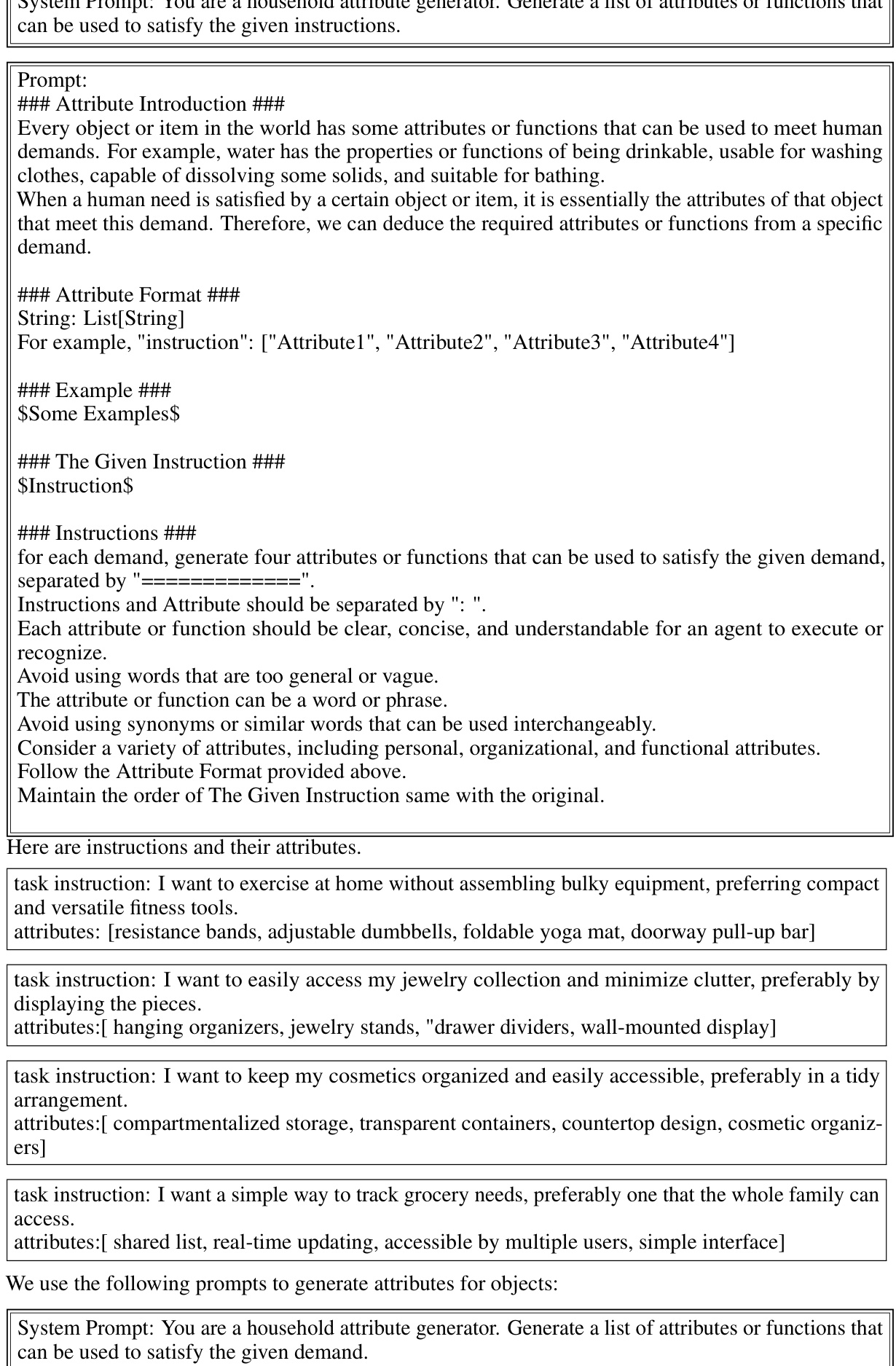

🔼 This figure illustrates the navigation policy of the proposed agent, showing how it alternates between coarse and fine exploration phases. The coarse phase involves segmenting the environment into blocks and using attribute features to select promising waypoints. The fine phase then utilizes an end-to-end module for precise object identification. The process continues until either a solution is found or a predefined number of steps or Find actions are reached.

read the caption

Figure 3: Navigation Policy. The agent continuously switches between a coarse exploration phase and a fine exploration phase until the Find count limit nfind is reached or the total number of steps Nstep is reached. See Sec. 4.2.1 and Sec. 4.2.2 for details about the two phases. In each timestep, the GLEE model is used to identify and label objects in the RGB and project them to the point cloud.

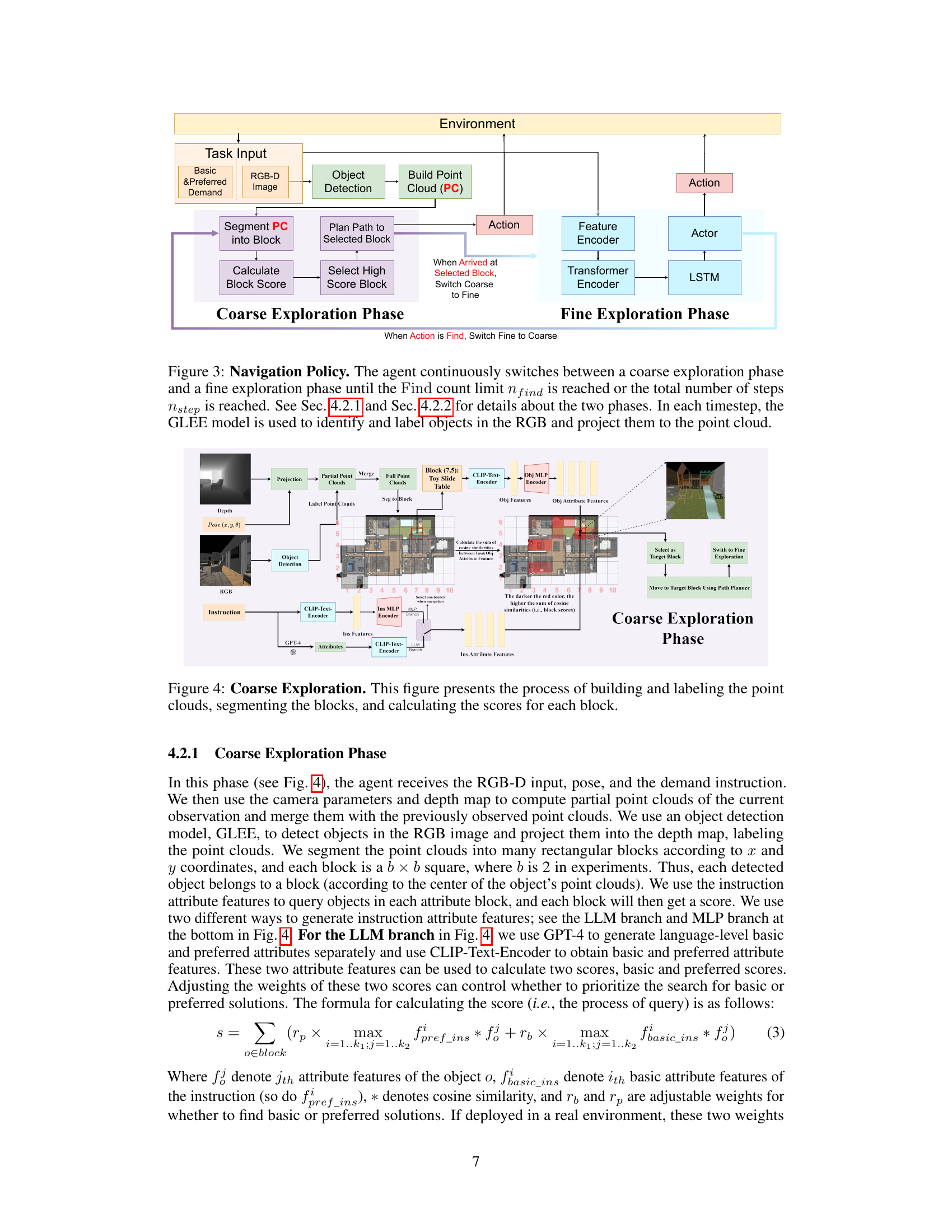

🔼 This figure shows the process of the coarse exploration phase in the MO-DDN navigation task. It starts with the RGB-D image and depth map as inputs, and these are used to generate a point cloud representation of the environment. The point cloud is then segmented into blocks. For each block, the similarity between object features and instruction attributes is calculated to generate a block score. These block scores are used to select the next waypoint for the agent. The LLM branch and the MLP branch are described in the figure to show two different approaches for generating instruction attribute features. Blocks with higher scores are indicated by darker shades of red in the image.

read the caption

Figure 4: Coarse Exploration. This figure presents the process of building and labeling the point clouds, segmenting the blocks, and calculating the scores for each block.

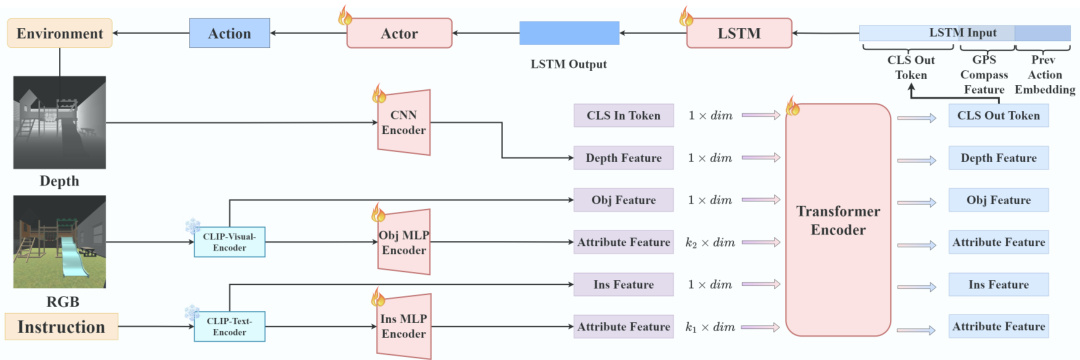

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the fine exploration phase in the MO-DDN model. It takes several inputs including RGB images, depth information, GPS/compass data, previous actions, and instruction attributes. These are processed by various encoders (CNN, CLIP Visual/Text, Obj MLP, Ins MLP), combined in a transformer, and passed through an LSTM to generate actions for the navigation agent. This fine-tuning phase uses imitation learning and relies on the attribute model trained earlier in the process.

read the caption

Figure 5: Fine Exploration. We employ imitation learning to train an end-to-end module in this phase. This module loads the Ins MLP Encoder and Obj MLP Encoder's parameters as initialization from attribute training, along with a Transformer Encoder to integrate features. The output feature corresponding to the CLS token is combined with GPS+Compass features and a previous action embedding and passed through an LSTM to generate actions by an actor.

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall navigation policy used by the agent. The agent alternates between a coarse exploration phase and a fine exploration phase. The coarse phase involves segmenting the environment into blocks and selecting a waypoint using attribute features, and the fine phase uses an end-to-end model to locate the target object within the chosen block. The process continues until a solution is found or the limits on the number of Find operations or steps are reached.

read the caption

Figure 3: Navigation Policy. The agent continuously switches between a coarse exploration phase and a fine exploration phase until the Find count limit nfind is reached or the total number of steps Nstep is reached. See Sec. 4.2.1 and Sec. 4.2.2 for details about the two phases. In each timestep, the GLEE model is used to identify and label objects in the RGB and project them to the point cloud.

🔼 This figure illustrates the navigation policy used in the MO-DDN task. The agent alternates between a coarse exploration phase, where it segments the environment into blocks and scores them based on attributes, and a fine exploration phase, where an end-to-end module refines object identification. This cycle continues until a solution is found or time constraints are met. The GLEE model plays a key role in object detection and labeling during both phases.

read the caption

Figure 3: Navigation Policy. The agent continuously switches between a coarse exploration phase and a fine exploration phase until the Find count limit nfind is reached or the total number of steps Nstep is reached. See Sec. 4.2.1 and Sec. 4.2.2 for details about the two phases. In each timestep, the GLEE model is used to identify and label objects in the RGB and project them to the point cloud.

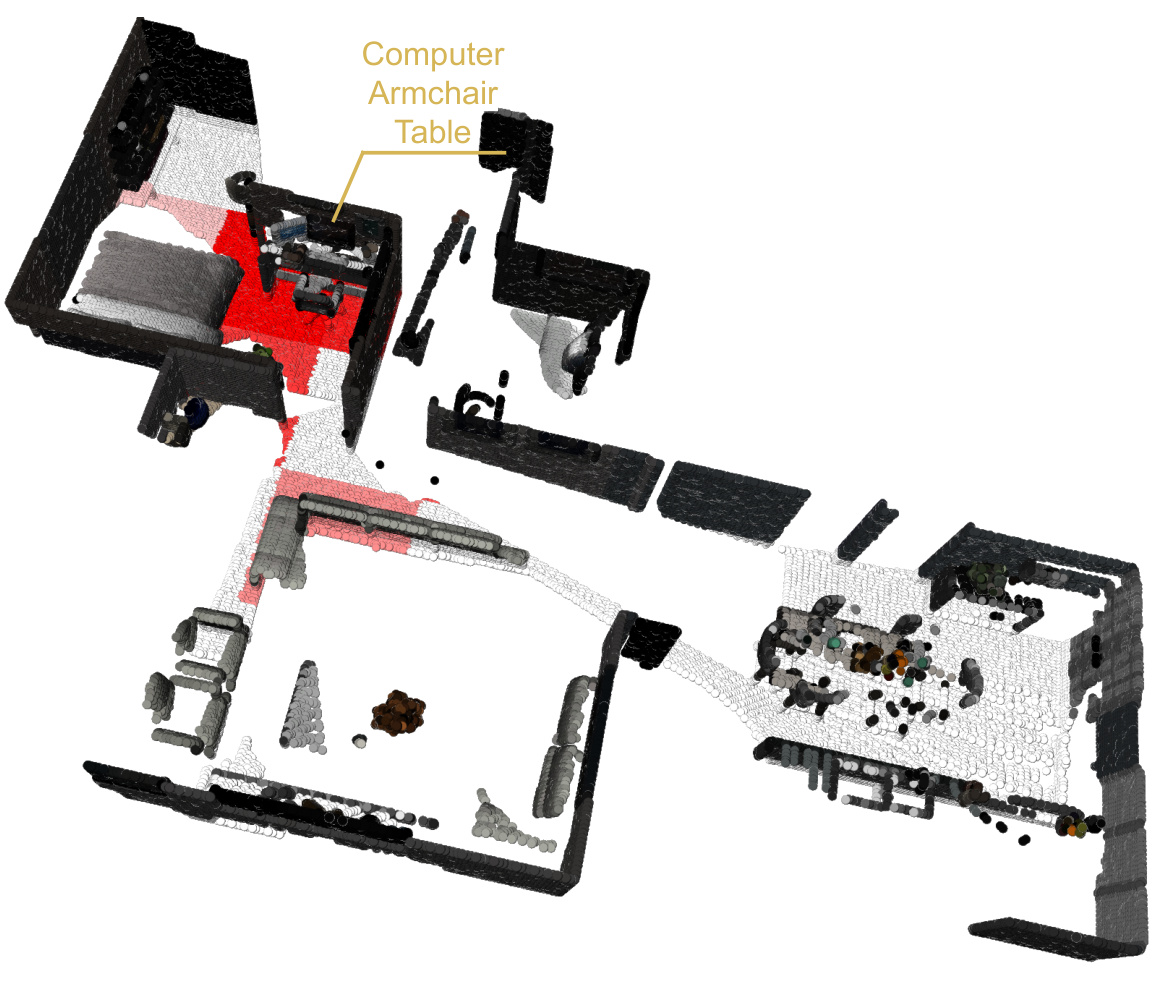

🔼 This figure visualizes the point cloud of a scene segmented into blocks. The instruction is to find a place to take quick notes during a meeting, ideally with a digital note-taking device. The solution shown consists of the Computer, Armchair, and Table, which suggests these items are located within a high-scoring block based on their attributes and relevance to the given instruction. The red region highlights the area where the selected objects, relevant to the given instruction, are located.

read the caption

Figure 6: Block Visualizations. Instruction: I need to take quick notes during a meeting, preferably with a device that saves them digitally. Solution: Computer, Armchair, Table.

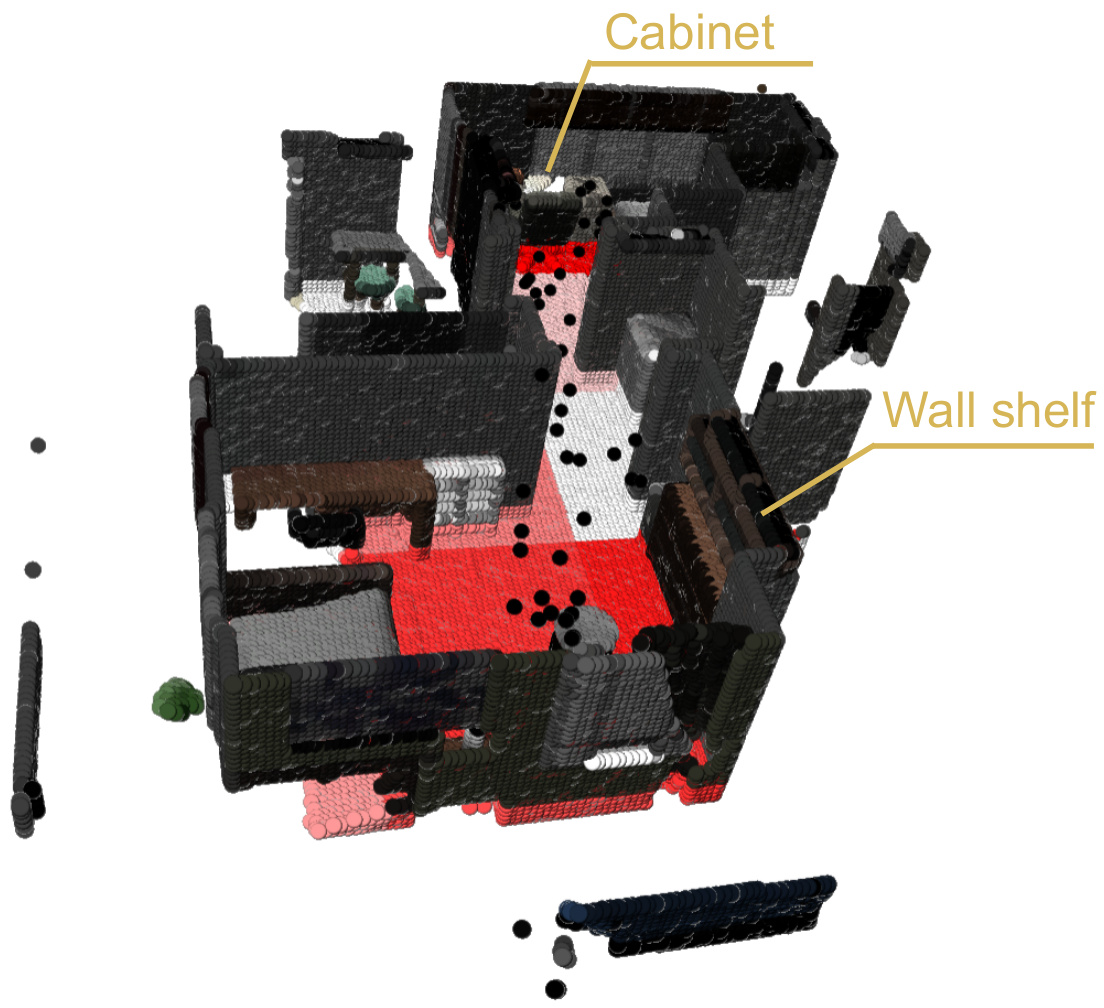

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of the coarse exploration phase of the MO-DDN agent. The agent is given the instruction to find a place to store fine china, preferably in an elegant way. The figure shows the point cloud representation of the environment, segmented into blocks. The color intensity of each block indicates its score, calculated based on the similarity between the block’s object attributes and the instruction attributes. Darker blocks have higher scores and higher probabilities of containing the target object(s). In this case, the blocks containing the wall shelf and cabinet are highlighted, indicating that these objects are predicted as the most suitable locations to store the fine china.

read the caption

Figure 7: Block Visualizations. Instruction: I need to store a collection of fine china, preferably in a way that displays them elegantly. Solution: Wall shelf, Cabinet.

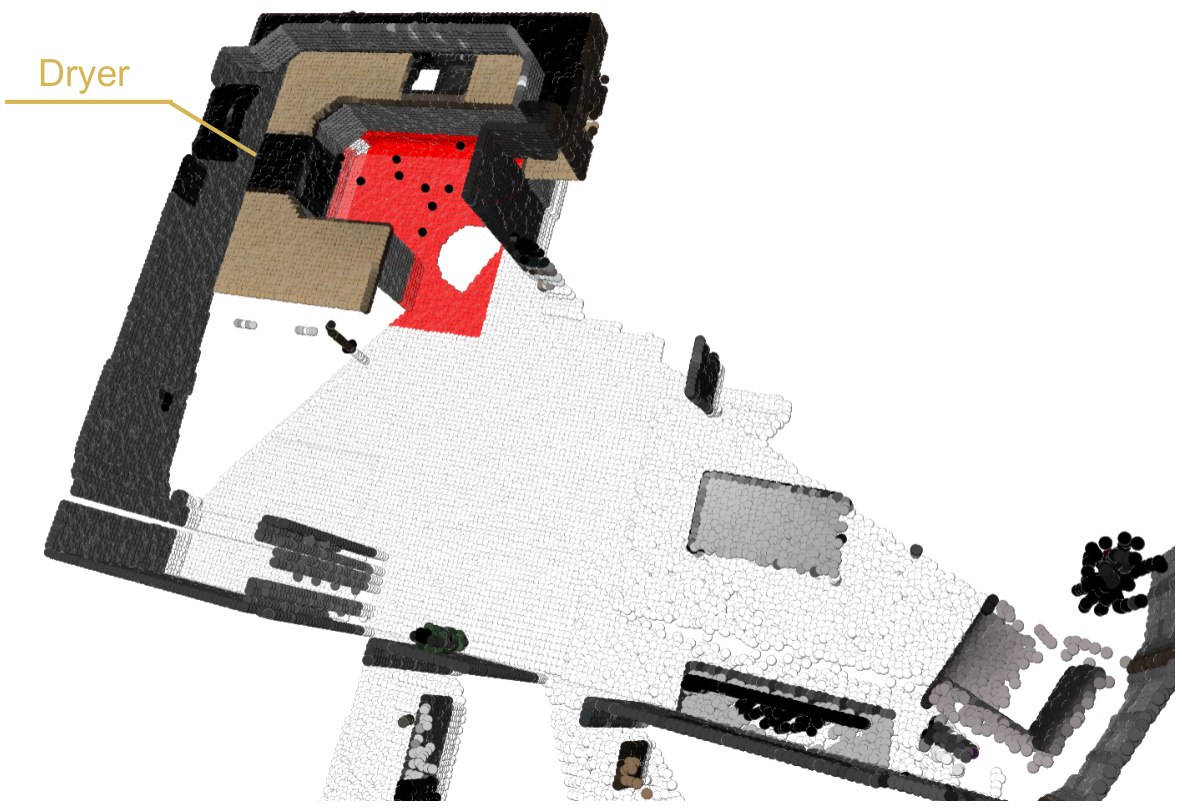

🔼 This figure shows the point cloud representation of a scene with objects detected and labeled. The instruction given to the agent was to find a way to quickly dry laundry, and the agent identified the dryer as the most suitable solution. The red highlighted area indicates the location of the dryer within the scene.

read the caption

Figure 8: Block Visualizations. Instruction: I need to quickly dry a batch of laundry, but I prefer an fast and energy-efficient method. Solution: Dryer.

🔼 This figure shows a point cloud representation of a scene in a house. The red highlighted areas indicate areas with high scores based on an attribute-based exploration method used in the MO-DDN (Multi-object Demand-driven Navigation) task. The task given to the agent was to find a comfortable place to read with good lighting. The agent successfully identified a sofa, side table, and ceiling lamp as suitable objects that meet this demand. The darker the red color, the higher the score for the corresponding block.

read the caption

Figure 9: Block Visualizations. Instruction: I need to find a comfortable place to read for my study group, preferable with good lighting. Solution: Sofa, Side table, Ceiling lamp.

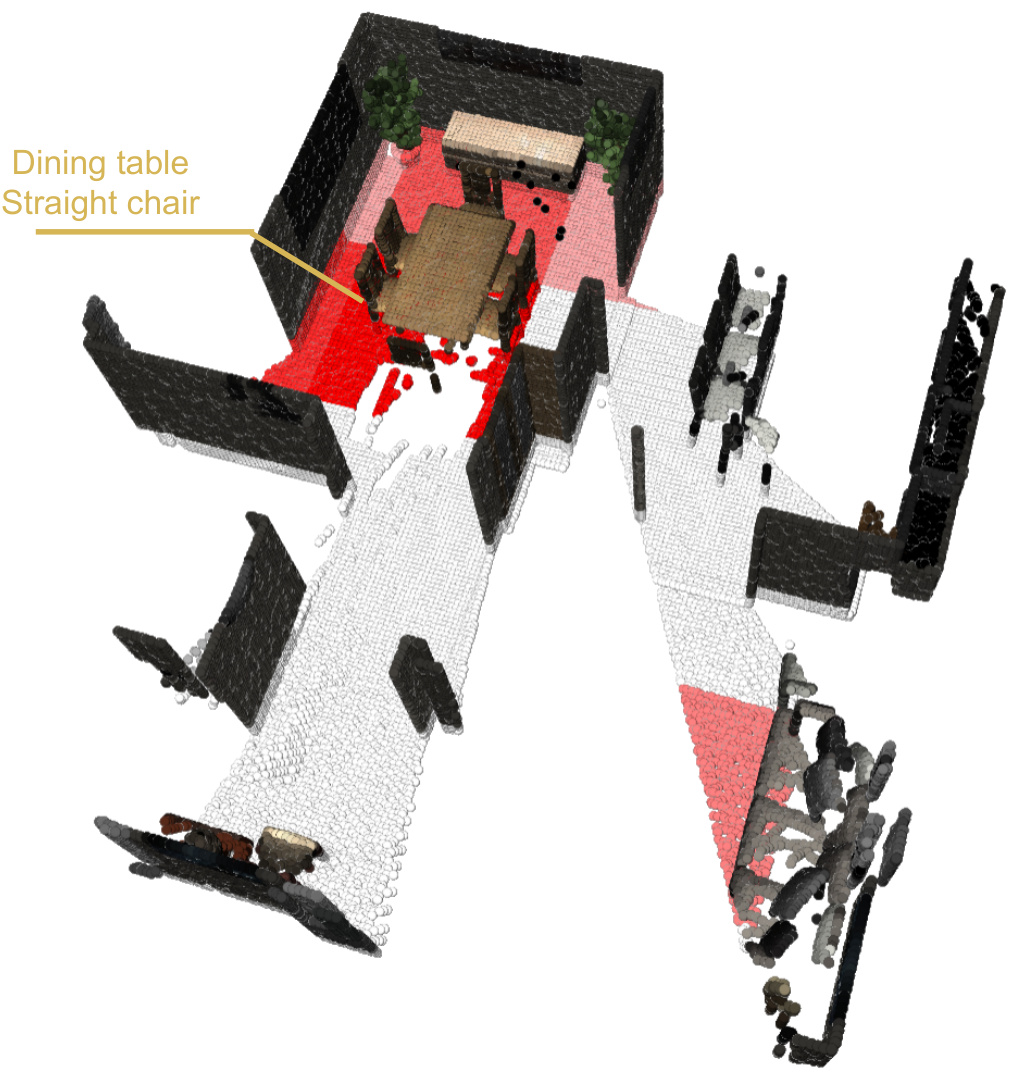

🔼 This figure shows a point cloud representation of a scene, segmented into blocks. The darker red blocks indicate a higher probability of containing objects relevant to the user’s request: to organize a small evening gathering without real candles. The caption highlights the specific instruction and the solution identified by the model (dining table and straight chair).

read the caption

Figure 10: Block Visualizations. Instruction: I need to organize a small evening gathering but want to avoid any accidents with real candles. Solution: Dining table, Straight chair.

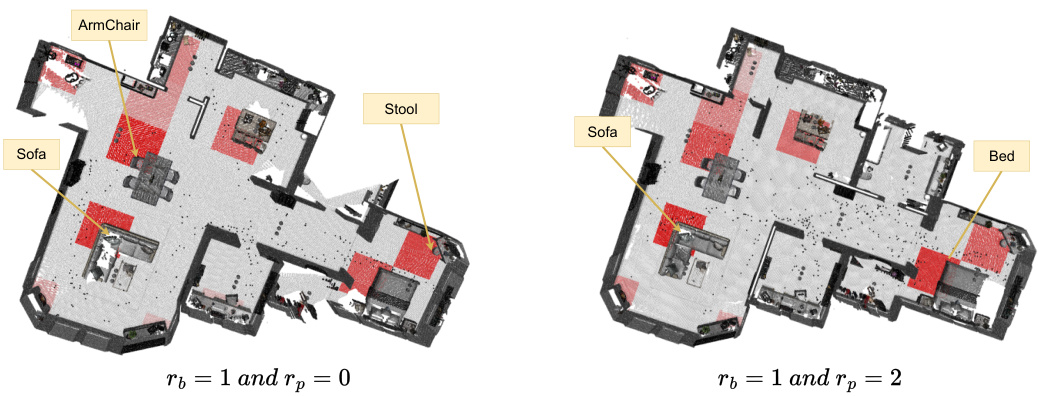

🔼 This figure shows how adjusting the weights (rb and rp) for basic and preferred demand similarity scores impacts block selection in the coarse exploration phase. The darker the red shading of a block, the higher its score. The left image shows a scenario where the basic demand weight (rb) is prioritized, resulting in multiple seating options being highlighted. The right image shows a scenario where the preferred demand weight (rp) is prioritized, resulting in only the most comfortable seating options (Sofa and Bed) being strongly highlighted.

read the caption

Figure 11: The Effect of rb and rp. This is an example used only to demonstrate scoring blocks. The darker the color in the figure, the higher the block score. When the task is “Find a place to sit, prefering a comfortable and soft place”, lowering rp (left) ignores preferences, so ArmChair, Sofa and Stool can get a high score (dark red); raising rp (right) focuses on preferences, so Sofa and Bed can get a high score.

🔼 This figure illustrates the navigation policy employed by the agent. It shows a continuous switching between a coarse exploration phase (where the agent explores larger areas of the environment, selecting waypoints based on attribute similarity) and a fine exploration phase (where the agent explores a smaller region around a selected waypoint, using an end-to-end attribute exploration module to identify the target objects). This process continues until either a predefined number of object searches (‘Find’ actions) is reached, or a maximum number of navigation steps is exceeded. The figure highlights the key components involved in each phase: point cloud generation and segmentation, object detection (GLEE model), and waypoint selection and path planning.

read the caption

Figure 3: Navigation Policy. The agent continuously switches between a coarse exploration phase and a fine exploration phase until the Find count limit nfind is reached or the total number of steps Nstep is reached. See Sec. 4.2.1 and Sec. 4.2.2 for details about the two phases. In each timestep, the GLEE model is used to identify and label objects in the RGB and project them to the point cloud.

More on tables

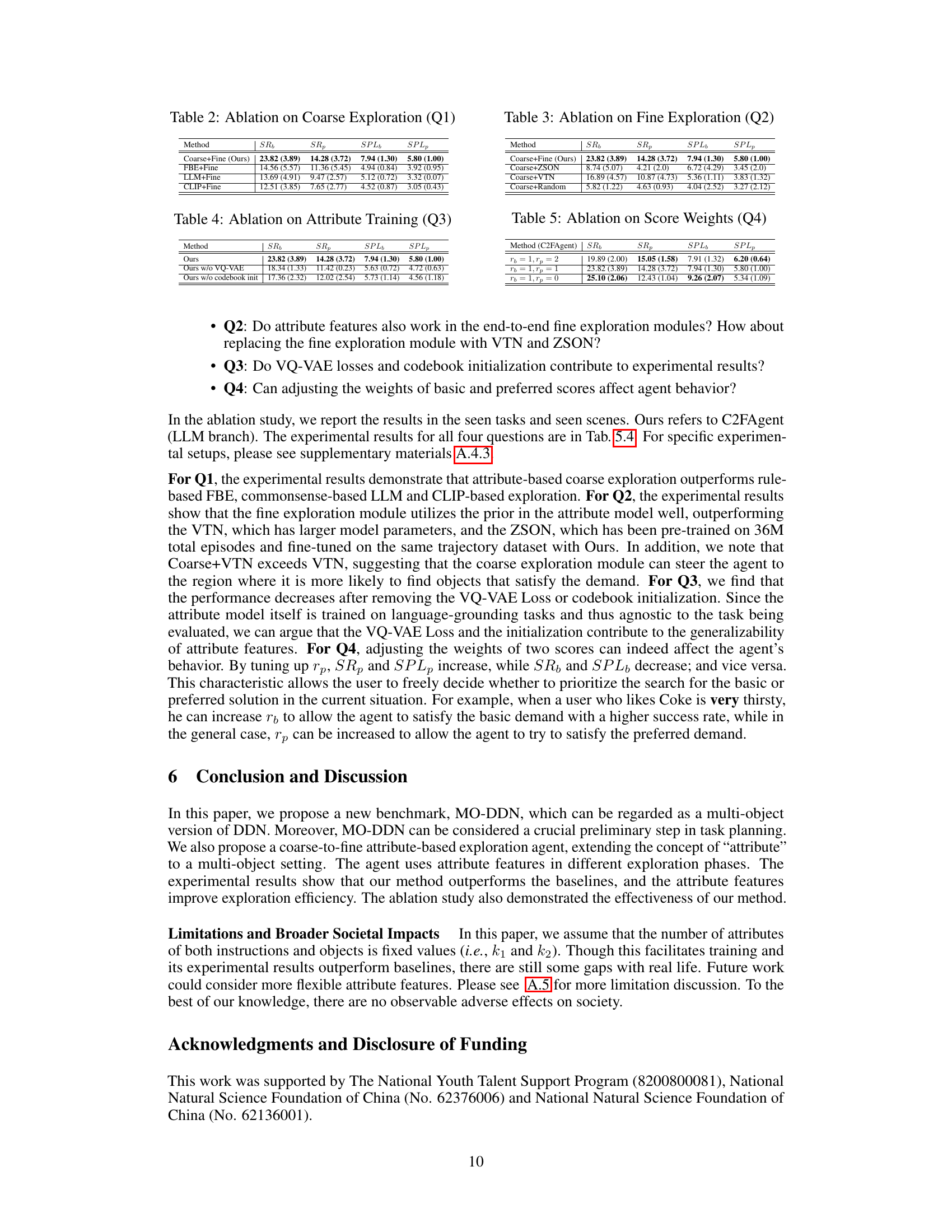

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the coarse exploration phase. It compares the performance of the proposed coarse-to-fine exploration method against several baselines: FBE+Fine, LLM+Fine, and CLIP+Fine. Each baseline replaces the proposed coarse exploration module with a different waypoint selection strategy. The results show the success rates (SRb and SRp) and Success Path Lengths (SPLb and SPLp) for both basic and preferred solutions. This allows for an assessment of how effectively different methods utilize attribute features to improve exploration efficiency.

read the caption

Table 2: Ablation on Coarse Exploration (Q1)

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The results are shown for both seen and unseen scenes, and for seen and unseen tasks. Metrics include Success Rate (SR) for basic and preferred demands, and Success Rate Path Length (SPL) for basic and preferred demands. The table highlights the superior performance of the C2FAgent model, particularly the LLM branch, compared to other methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in navigating multi-object scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

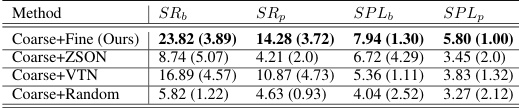

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the attribute training process. It shows the impact of removing the VQ-VAE losses and the codebook initialization on the model’s performance, measured by SRb, SRp, SPLb, and SPLp. The results help to understand the contribution of each component to the overall attribute model training.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation on Attribute Training (Q3)

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the effect of score weights (basic and preferred) on the performance of the C2FAgent in the MO-DDN benchmark. It shows the success rate (SR) for basic and preferred demands, and the success rate penalized by path length (SPL) for basic and preferred demands, for different weightings of the basic (rb) and preferred (rp) scores. The results indicate how adjusting these weights influences the agent’s prioritization of basic versus preferred demands, affecting overall performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation on Score Weights (Q4)

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The metrics used are Success Rate (SR) for basic and preferred demands, and Success Rate Path Length (SPL) for basic and preferred demands. The results are shown separately for seen and unseen tasks, and for seen and unseen scenes, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s generalization capabilities. The baseline methods include Random, VTN, ZSON, DDN, MOPA+LLM*, and FBE+LLM*. The asterisk (*) indicates that the methods used ground truth semantic labels.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The baseline methods include Random (random action selection), VTN (end-to-end ObjectGoal Navigation), ZSON (end-to-end ObjectGoal Navigation), DDN (Demand-driven Navigation), MOPA+LLM* (modular Multi-object Navigation using LLMs), and FBE+LLM* (modular Multi-object Navigation using frontier-based exploration and LLMs). The results are shown for both seen and unseen tasks and scenes, and metrics include success rates (SRb and SRp for basic and preferred demands respectively) and success path lengths (SPLb and SPLp for basic and preferred demands respectively). The asterisk (*) indicates that the method used ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold values represent the best performance across all methods for each metric.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

🔼 This table compares the MO-DDN and DDN benchmarks across several key features. It highlights the differences in handling user preferences (Preference), the complexity of the navigation task (Multi-object), the number of object categories considered, the average length of the instructions, the number of solutions for each demand instruction and the average number of objects per solution. The use of the slash (/) indicates that some metrics are given separately for basic and preferred aspects of the task.

read the caption

Table 6: A Comparison Between MO-DDN and DDN. The slash symbol '/' distinguishes between basic and preferred data. The left side of the slash indicates basic, and the right side indicates preferred.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The results are shown for both seen and unseen tasks and scenes. Metrics include Success Rate (SR) for basic and preferred demands, and Success Rate Path Length (SPL) for basic and preferred demands. The table highlights the superior performance of C2FAgent, particularly when considering both basic and preferred demands. The impact of using ground truth semantic labels is also demonstrated.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The results are reported in terms of Success Rate (basic and preferred), and Success Rate Path Length (basic and preferred). The baselines include Random, VTN, ZSON, DDN, MOPA+LLM*, and FBE+LLM*. The * indicates methods that use ground truth semantic labels. The table shows superior performance of C2FAgent over all baselines, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed coarse-to-fine attribute-based exploration strategy.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The performance metrics include Success Rate (SR) for both basic and preferred demands (SRb and SRp respectively), and Success Rate Path Length (SPL) for both basic and preferred demands (SPLb and SPLp respectively). The results are shown for both seen and unseen tasks and scenes. The baseline methods are Random, VTN, ZSON, DDN, MOPA+LLM*, and FBE+LLM*. The asterisk (*) indicates methods using ground truth semantic labels. The table highlights the superior performance of the C2FAgent model across various metrics.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed C2FAgent model against several baseline methods on the MO-DDN benchmark. The metrics used for comparison include Success Rate (basic and preferred), and Success Rate Path Length (basic and preferred). Results are shown for both seen and unseen tasks, and seen and unseen scenes, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the different approaches’ ability to handle multi-object demand-driven navigation with varying levels of complexity.

read the caption

Table 1: Baseline Comparison. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. * represents the usage of ground truth semantic labels in the RGB image. The bold fonts represent optimal values.

Full paper#