↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing methods for interpreting CLIP’s zero-shot image classification often lack human-friendliness and fail to break down the entangled attributions. This paper introduces a novel approach that interprets CLIP models from the lens of mutual knowledge between vision and language modalities, addressing these limitations. The key idea is to analyze the common concepts learned by both encoders influencing the joint embedding space, revealing which concepts are closer or further apart.

The approach uses textual concept-based explanations, showcasing their effectiveness across various CLIP models with varying architectures, sizes, and pretraining datasets. It analyzes the zero-shot predictions in relation to mutual knowledge between modalities by measuring mutual information dynamics. The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of textual concepts in understanding zero-shot classification, providing a human-friendly way to interpret CLIP’s decision-making processes and revealing relationships between model aspects and mutual knowledge.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on zero-shot image classification and explainable AI (XAI). It offers a novel approach for interpreting complex models like CLIP, advancing the field of XAI and providing valuable insights for improving model transparency and decision-making processes. Furthermore, the method of using mutual information dynamics and textual concepts provides a new avenue for interpreting and analyzing other multi-modal models.

Visual Insights#

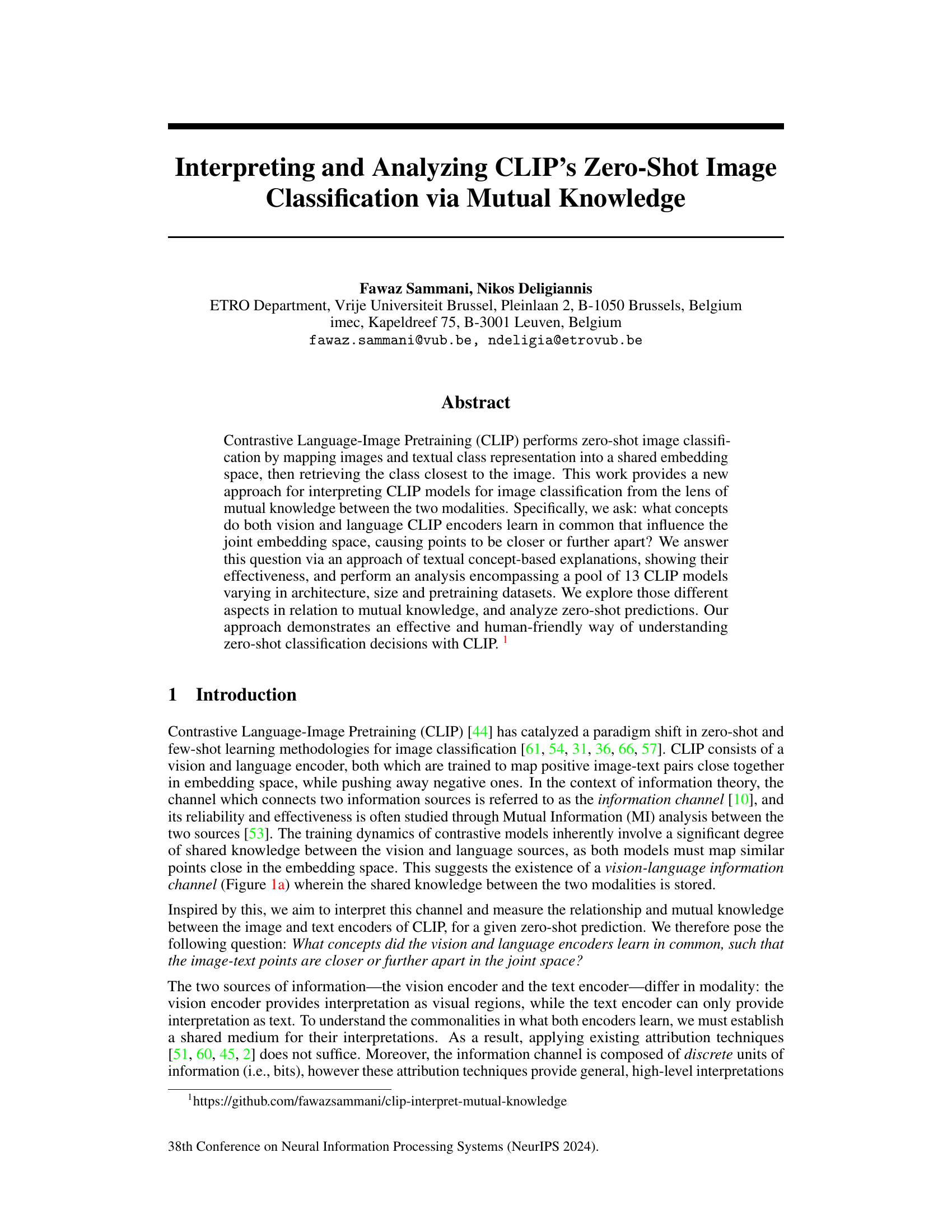

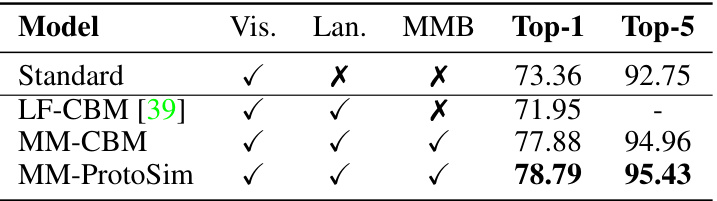

This figure illustrates the process of interpreting CLIP’s zero-shot image classification. It shows how visual and textual inputs are mapped into a shared embedding space. (a) depicts the overall process with a mutual information channel. (b) shows visual features from the vision encoder being represented with multimodal concepts (object parts with textual descriptions). (c) highlights points from the language encoder around the predicted class. Finally, (d) demonstrates how common textual concepts are identified in both encoders, revealing shared knowledge.

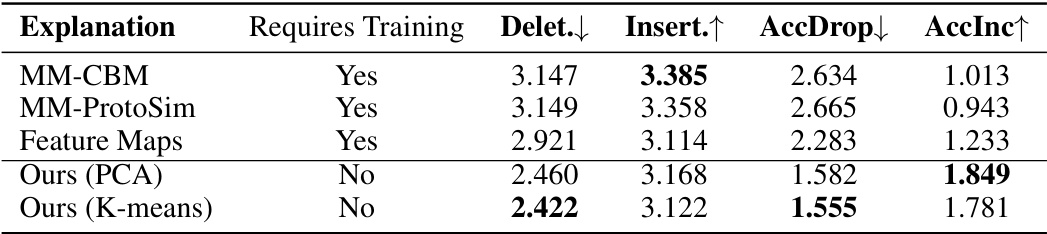

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed multimodal explanation method against three established baselines. The evaluation is based on four metrics: Deletion, Insertion, Accuracy Drop, and Accuracy Increase. These metrics assess the impact of adding or removing concepts on classification accuracy. The table also indicates whether each method requires training. The results show that the proposed method, even without training, achieves comparable or better performance in certain aspects compared to the other methods that require training.

In-depth insights#

Mutual Knowledge#

The concept of ‘Mutual Knowledge’ in the context of a contrastive language-image model like CLIP is explored to understand zero-shot image classification. It posits that the model’s ability to successfully classify images stems from a shared, overlapping understanding between the vision and language encoders. This shared knowledge isn’t simply about recognizing individual features, but instead focuses on higher-level concepts and relationships. The paper investigates how these commonalities influence the model’s embedding space, making semantically similar images and text descriptions cluster together. The researchers propose a novel method to quantify and analyze this mutual knowledge using textual concept-based explanations, providing a human-friendly way to interpret the model’s internal workings. By measuring mutual information between visual and textual concepts, they aim to reveal what aspects of the input data are most critical to the model’s zero-shot performance, shedding light on the model’s implicit reasoning process and improving explainability.

Visual Concept Extraction#

Visual concept extraction is a crucial step in many computer vision tasks, aiming to identify and represent meaningful visual patterns from raw image data. The choice of extraction method significantly impacts downstream tasks’ performance. Approaches vary widely, ranging from simple feature engineering techniques (e.g., SIFT, HOG) to sophisticated deep learning models (e.g., convolutional neural networks, vision transformers). Deep learning methods often excel at automatically learning hierarchical representations of visual concepts, capturing complex relationships between features. A key challenge lies in balancing the complexity of the model with interpretability. Highly complex models can be powerful but difficult to understand; simpler approaches might lack the capacity to capture subtle visual nuances. The choice often depends on the specific task, available data, and computational resources. Another critical aspect is concept granularity. Methods can extract fine-grained concepts (e.g., specific object parts) or coarse-grained concepts (e.g., object categories). The desired granularity depends heavily on the task; fine-grained concepts benefit tasks requiring detailed analysis, while coarse-grained approaches are suitable for higher-level classification. Finally, the evaluation of concept extraction remains an open research problem. Objective metrics for evaluating concept quality and relevance often prove challenging to define and implement, making it difficult to compare and contrast different approaches effectively.

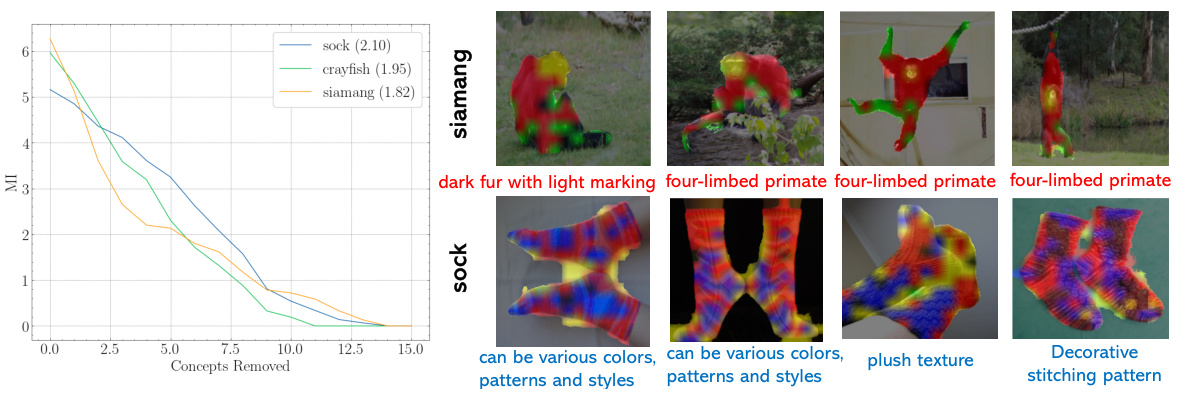

MI Dynamics#

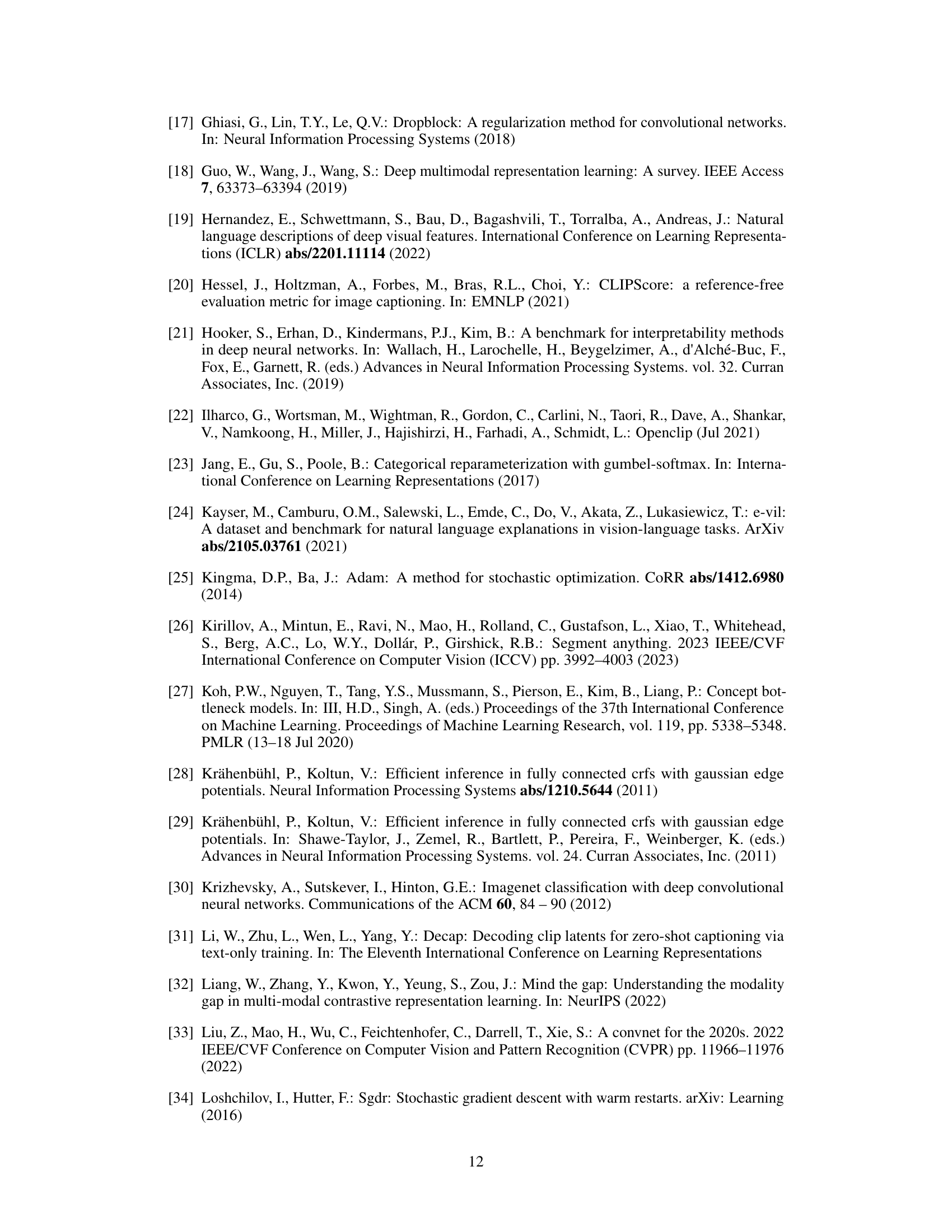

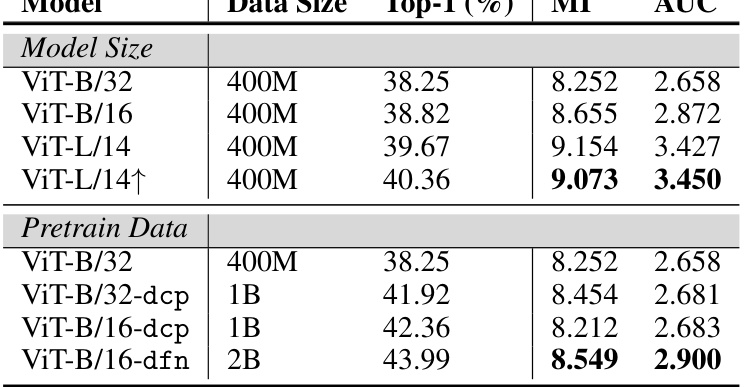

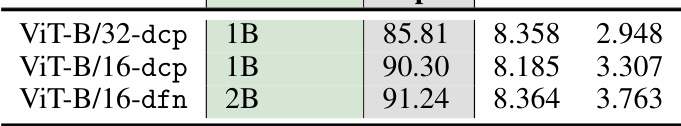

The section on “MI Dynamics” delves into the analysis of mutual information (MI) changes over multiple iterations of removing concepts from the vision encoder, providing a nuanced understanding of shared knowledge between vision and language encoders in CLIP. It innovatively uses Area Under the Curve (AUC) to quantify the strength of this shared knowledge, revealing that a higher AUC, indicating a gradual MI drop, signifies stronger shared knowledge. This approach is crucial because simply comparing raw MI values doesn’t reveal the robustness of the shared knowledge to concept removal. The analysis of MI dynamics demonstrates a strong correlation with zero-shot accuracy and model/dataset characteristics, demonstrating that models with higher AUC show better zero-shot performance. This suggests that a model’s ability to retain knowledge despite removing components is key to effective zero-shot image classification, providing novel insights into CLIP’s inner workings and the factors influencing its performance.

CLIP Model Analysis#

A thorough CLIP model analysis would involve a multifaceted investigation. It would begin by examining the architecture’s impact on performance, exploring variations like ViT-B/16, ViT-L/14, and ResNet-based models. Model size and complexity would be correlated with zero-shot classification accuracy and the strength of mutual knowledge between vision and language encoders. The impact of different pretraining datasets (e.g., WIT, LAION) on model capabilities would also be assessed. Analyzing the information channel’s dynamics through mutual information calculations (MI and AUC) would reveal how strongly the encoders share information. Evaluation metrics beyond accuracy (e.g., Insertion, Deletion, AccDrop, AccInc) would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the model’s performance in various situations. Finally, a qualitative analysis, examining the model’s interpretation of visual features through multimodal concept analysis, would offer valuable insights into model decision-making. This involves looking at the effectiveness of visual concept extraction techniques such as PCA and K-means, and assessing how well these align with textual descriptions of the visual concepts and the prediction made.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on interpreting CLIP’s zero-shot image classification could explore several promising avenues. Extending the multimodal concept analysis to other vision-language models beyond CLIP would validate the generalizability of the proposed methodology and reveal potential architectural influences on shared knowledge. Investigating the impact of different training datasets and model sizes on the mutual information dynamics would offer crucial insights into the relationship between model characteristics and the effectiveness of shared knowledge in zero-shot classification. A key area for future research lies in developing more robust and efficient methods for extracting and representing fine-grained visual concepts. The current reliance on PCA or K-means might limit the expressiveness and capture subtle distinctions within images. Additionally, exploring the application of this approach to diverse downstream tasks such as image retrieval, image captioning, and few-shot learning would demonstrate its broader applicability and reveal how the mutual knowledge influences performance across different tasks. Finally, developing interactive visualization tools that allow users to explore and understand the mutual knowledge between different model components would enable a more intuitive and accessible understanding of zero-shot classification decisions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

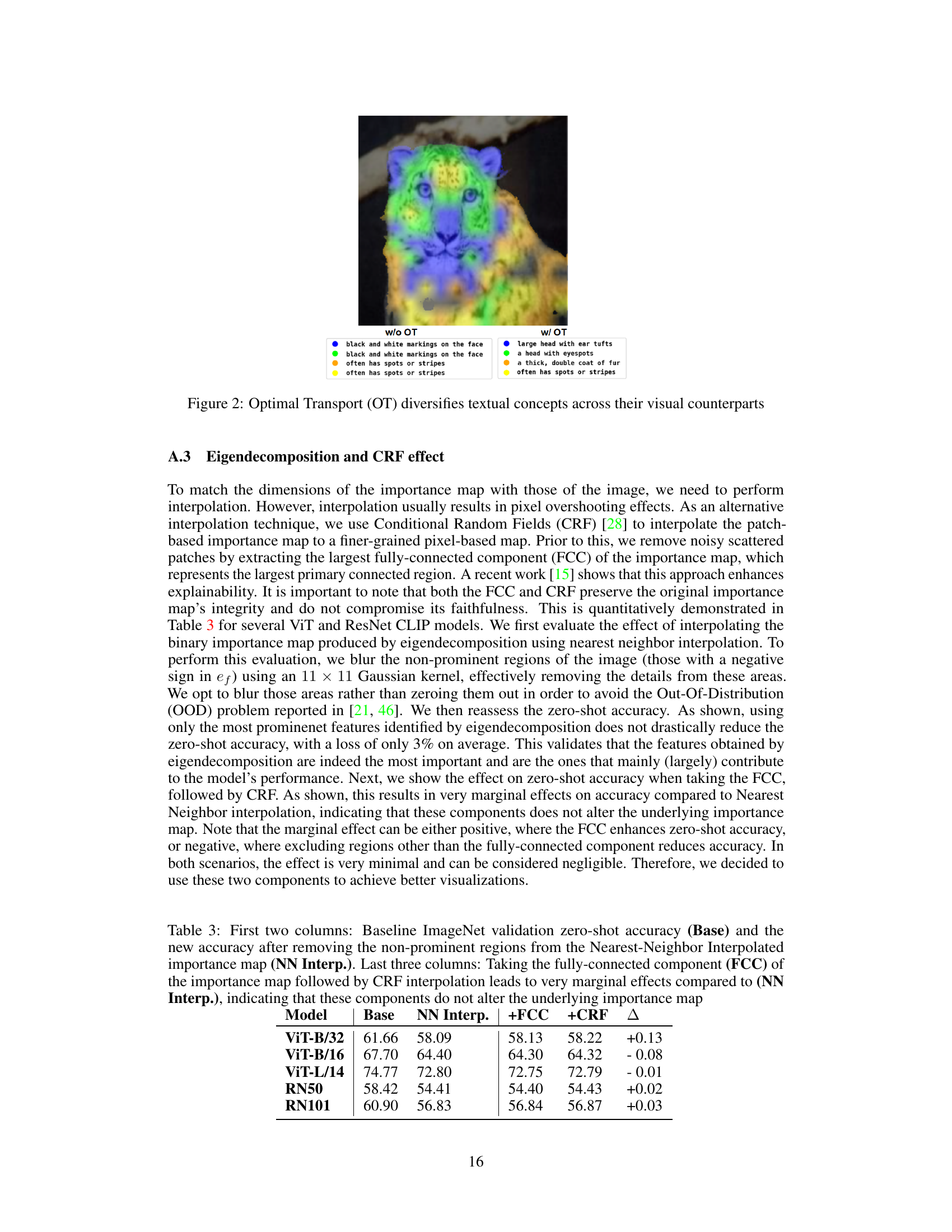

This figure illustrates the process of obtaining multimodal concepts for interpreting CLIP’s zero-shot image classification decisions. It shows three main steps: (a) Deriving visual concepts from the vision encoder by applying eigendecomposition or K-means clustering on the image patches, (b) Querying each visual concept from a textual bank to obtain corresponding textual descriptions, and (c) Deriving textual concepts from the language encoder by identifying points around the zero-shot prediction in the embedding space. The final output is a common space of fine-grained textual concepts from both encoders, enabling the calculation of mutual information.

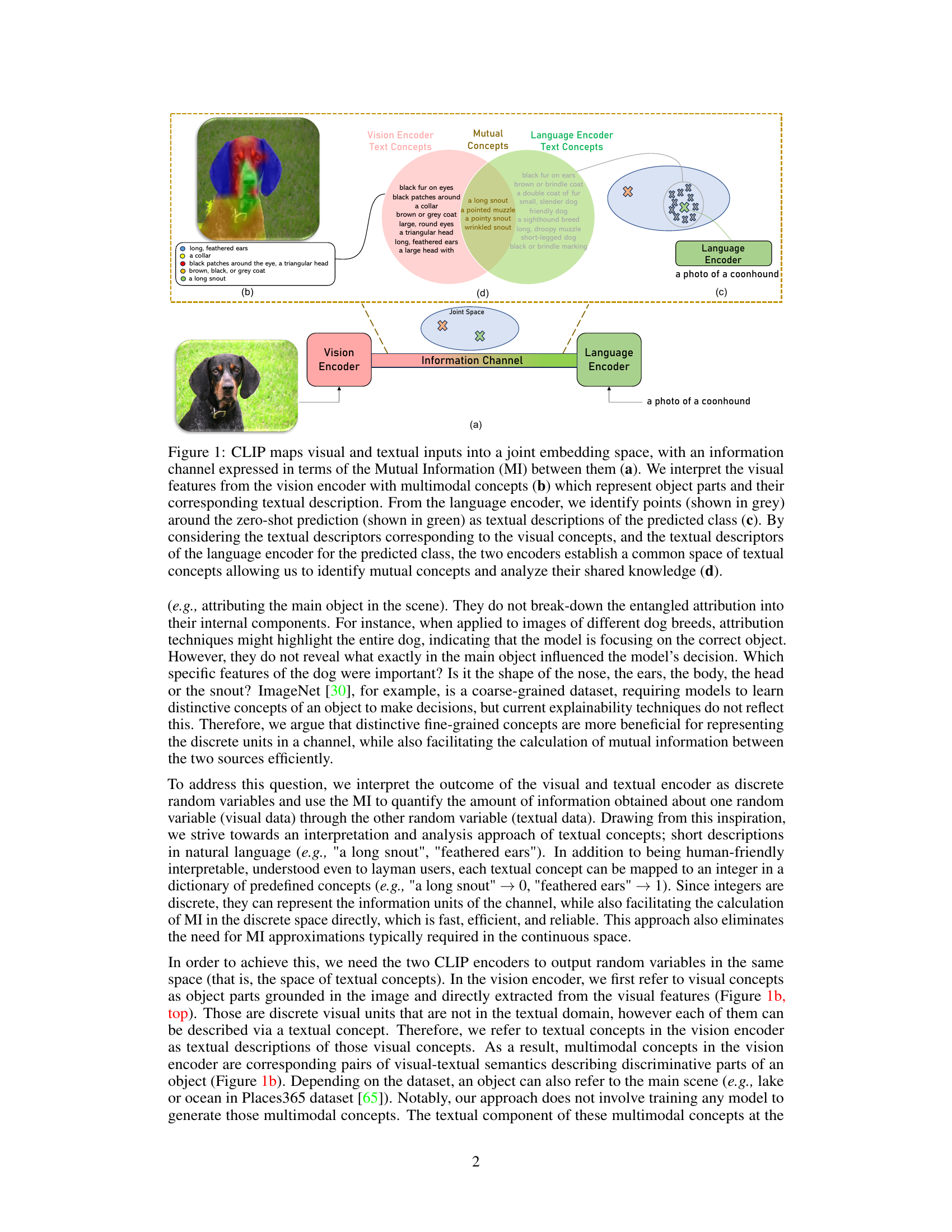

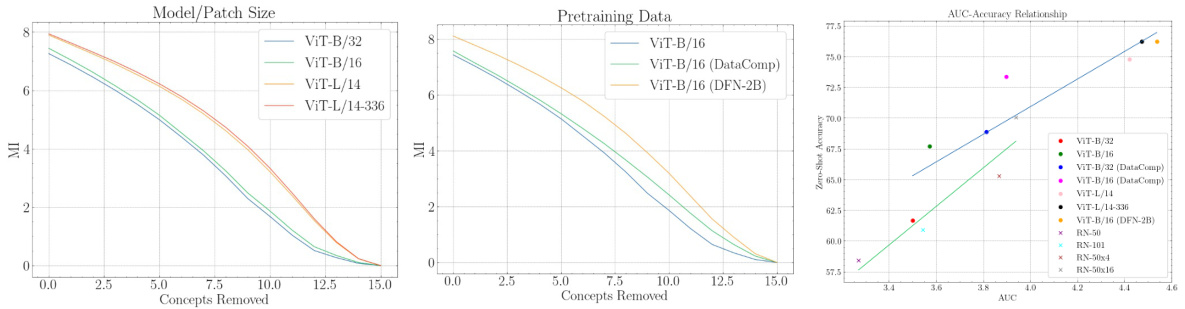

This figure presents three plots that illustrate the relationship between mutual information (MI), area under the curve (AUC), and zero-shot classification accuracy in CLIP models. The left plot shows MI dynamics curves for different ViT model architectures with the same pretraining data. The middle plot shows MI dynamics curves for the ViT-B/16 model trained on different datasets. Finally, the right plot shows the correlation between AUC and zero-shot accuracy for both ViT and ResNet models, demonstrating a positive correlation.

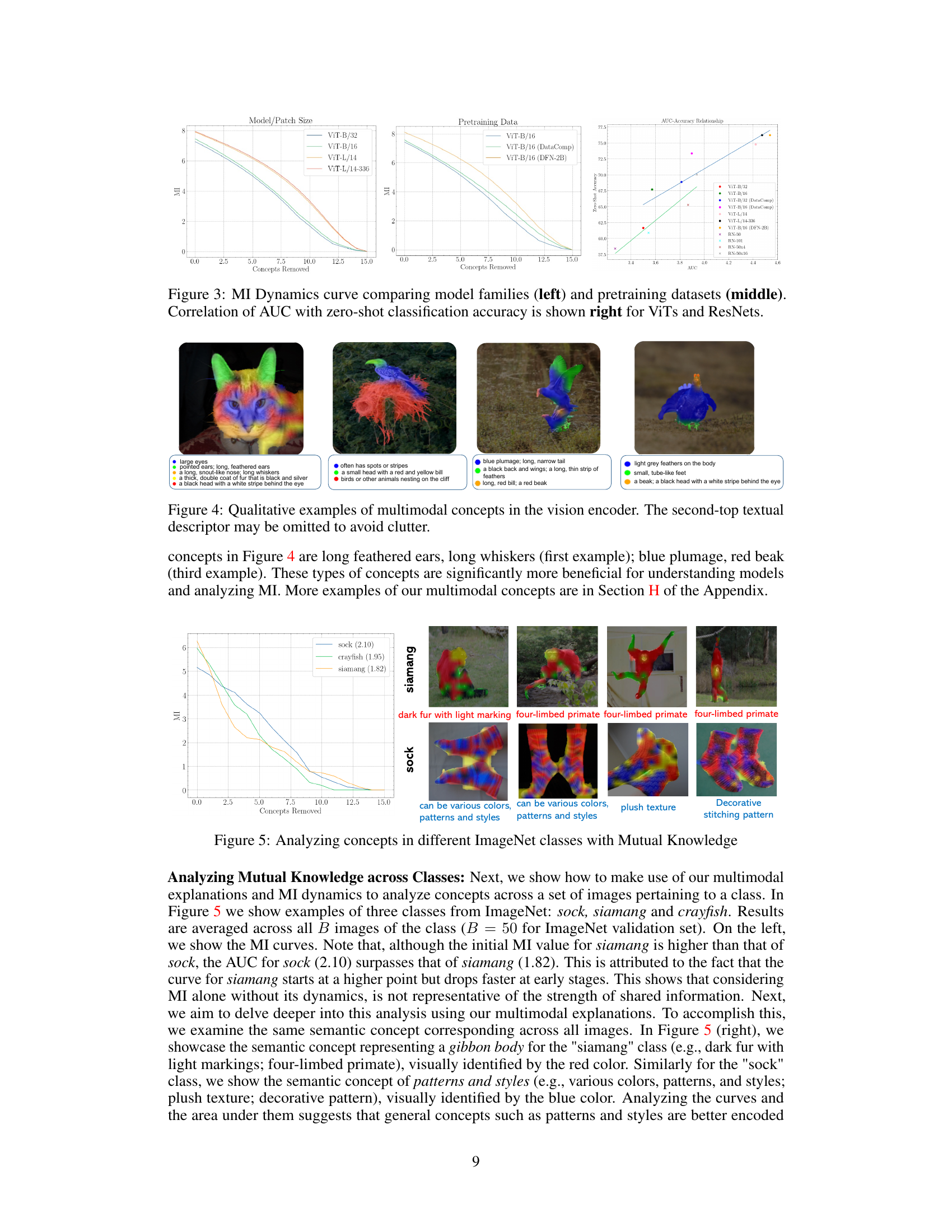

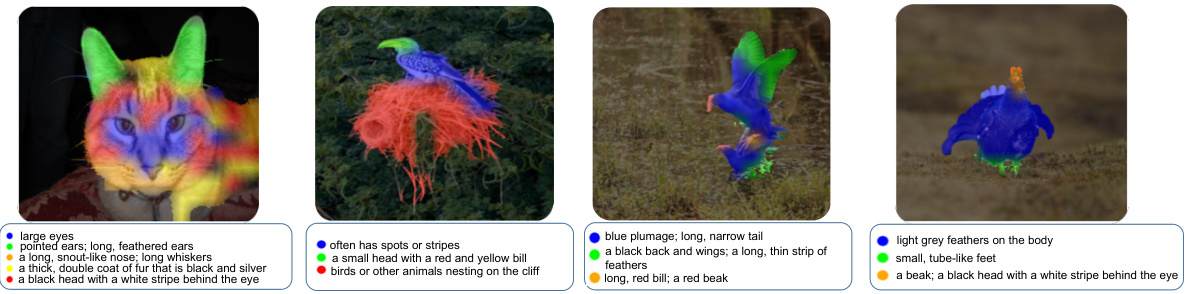

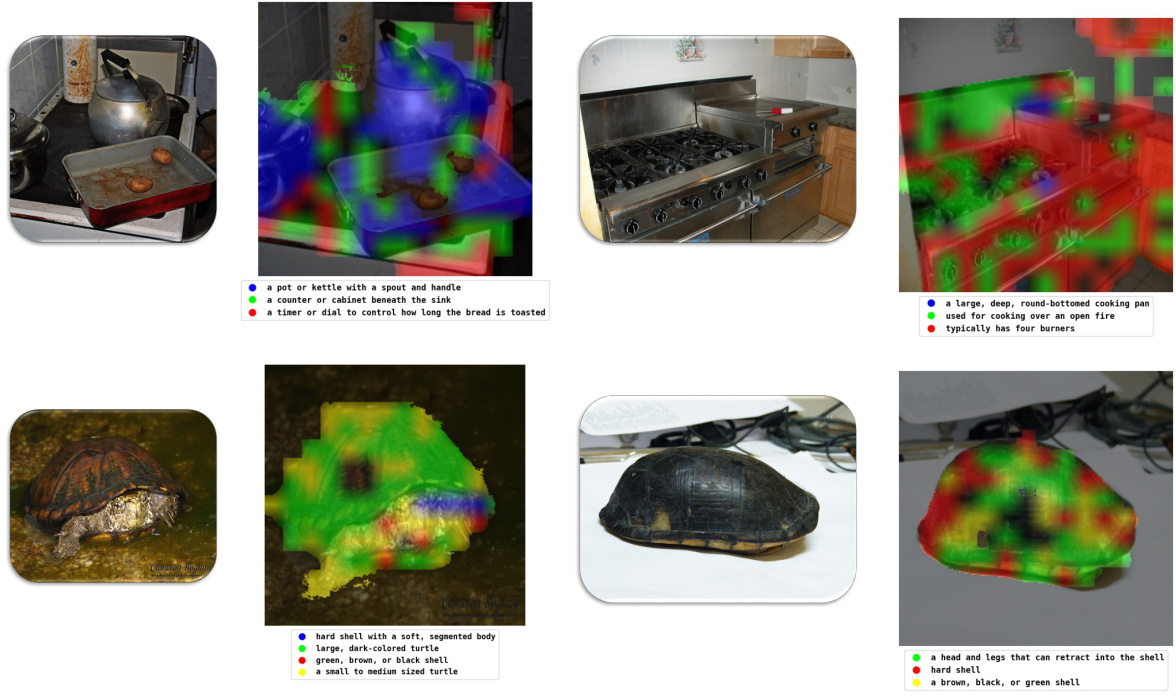

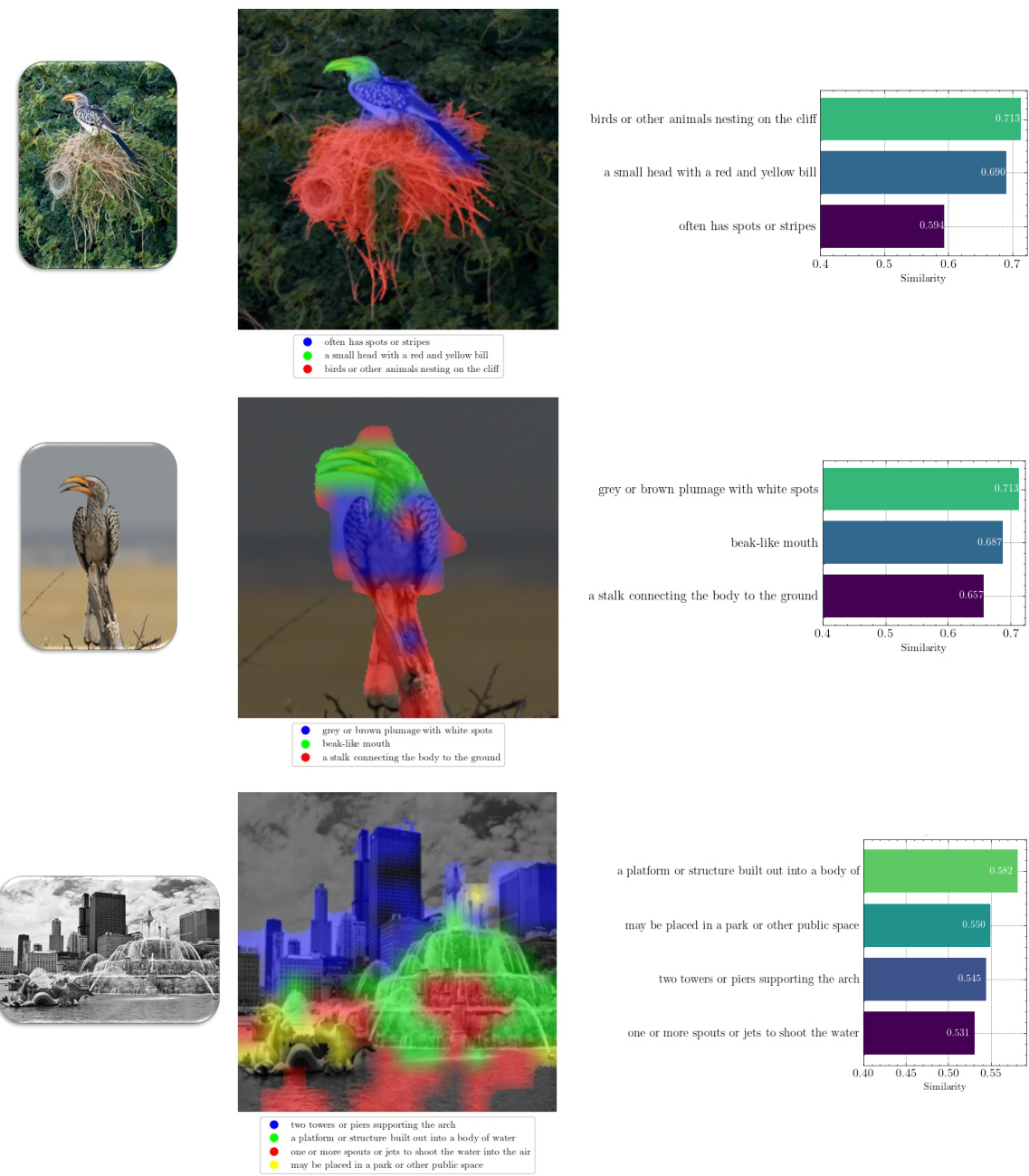

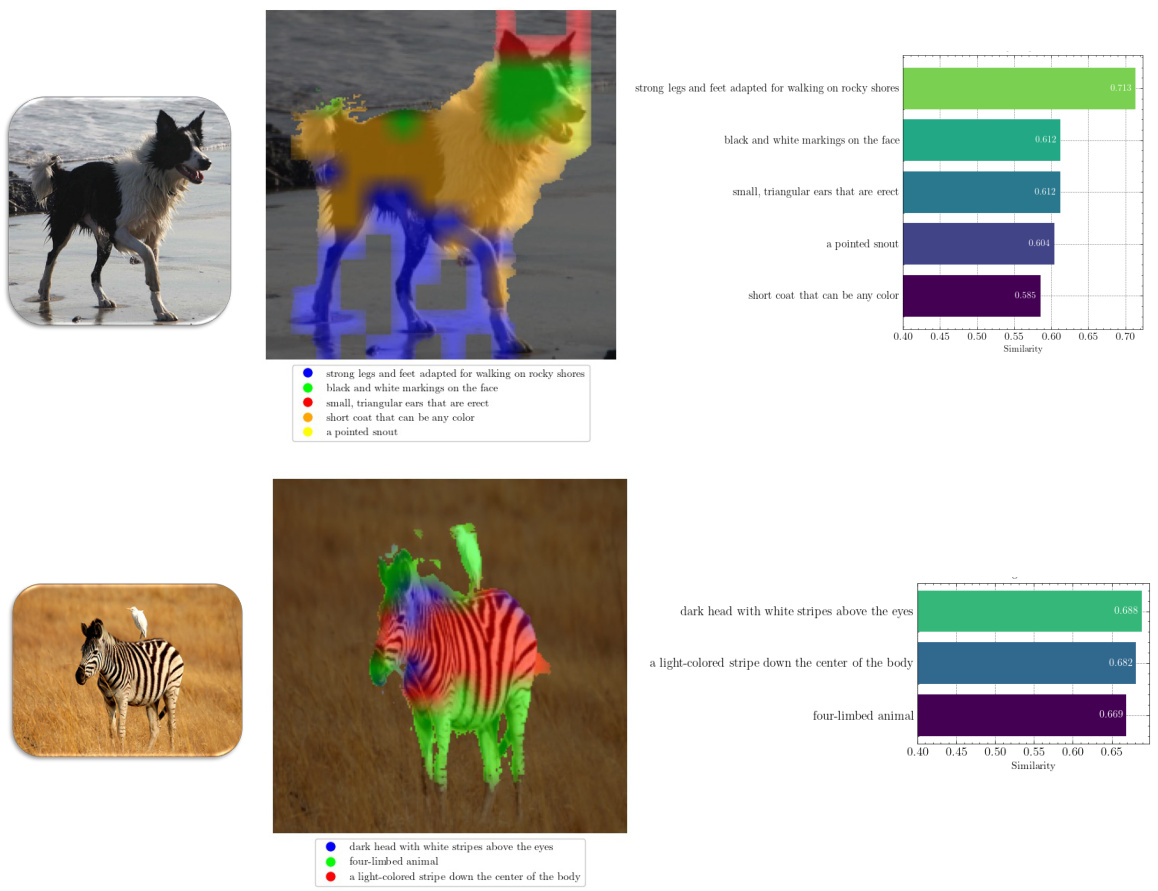

This figure shows four examples of multimodal concepts extracted from the vision encoder. Each example shows an image with different regions highlighted in different colors, each region representing a visual concept. Below each image, there is a list of textual descriptions corresponding to each of the visual concepts. These descriptions are short and concise, making them human-friendly and easily interpretable. The figure aims to showcase how the model extracts and represents fine-grained visual concepts and how these are linked to textual concepts in the vision encoder.

This figure presents three graphs illustrating the relationship between mutual information (MI), area under the curve (AUC), and zero-shot classification accuracy across different CLIP models. The left graph shows MI dynamics across several ViT models with the same pretraining data but varying architecture and patch sizes. The middle graph shows MI dynamics across different ViT models with varying pretraining data but a fixed architecture. The right graph shows a positive correlation between AUC and zero-shot accuracy for both ViT and ResNet models, indicating stronger shared knowledge leads to higher accuracy. This demonstrates how different architectural choices and data size affect model performance.

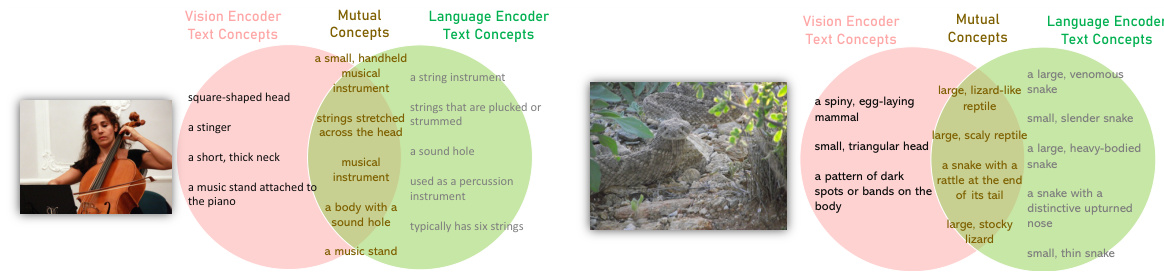

This figure visualizes the mutual concepts learned by both vision and language encoders of CLIP for two examples. In the first example, mutual concepts are shown to be distinctive for the prediction of cello (e.g., handheld musical instrument, strings stretched across the head, a sound hole), indicating effective representation of the image and class in the joint space. The second example shows that language encoder is stronger than visual encoder at encoding the concept of rattle snake, since it provides related concepts, while the mutual concepts are weaker. These visualizations highlight how the two encoders learn in common and influence each other.

This figure illustrates the proposed method for interpreting CLIP’s zero-shot image classification. It shows how visual and textual inputs are mapped into a shared embedding space, and how mutual information between the two modalities is used to understand the model’s decisions. The figure is broken down into four parts: (a) CLIP’s joint embedding space and its information channel. (b) Multimodal concepts extracted from the vision encoder. (c) Textual descriptions identified from the language encoder around the zero-shot prediction. (d) The common space of textual concepts shared by the vision and language encoders, revealing the mutual knowledge learned.

This figure illustrates the methodology used to derive visual and textual concepts to calculate mutual information. Panel (a) shows the process of deriving visual concepts through PCA or k-means clustering on image patches. Panel (b) shows how these visual concepts are described using textual concepts from a pre-defined bank of concepts. Finally, Panel (c) shows how textual concepts are derived from the language encoder to establish a common ground for MI calculation.

This figure shows four examples of how the model identifies and describes visual concepts using multimodal concepts. Each image is divided into regions, each with a distinct color representing a different visual concept. Beneath each image are textual descriptions corresponding to the color-coded regions, providing fine-grained visual and textual descriptions of the object’s parts. These details demonstrate the model’s ability to break down object recognition into fine-grained details, going beyond simple high-level interpretations of an object as a whole.

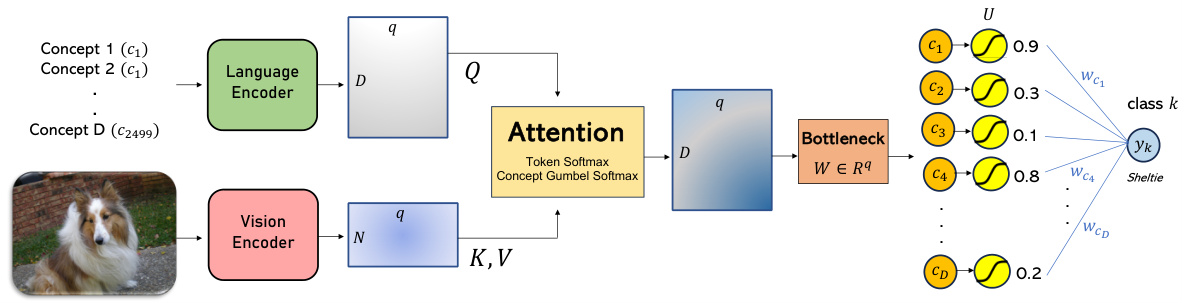

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Multimodal Concept Bottleneck Model (MM-CBM) baseline. The process starts with encoding the set of textual descriptors (D) using CLIP’s language encoder, followed by a linear projection to obtain concept features (Q). These features serve as queries for an attention mechanism. The image (I) is encoded using CLIP’s vision encoder, producing key and value features (K, V). Cross-attention is then applied, followed by a linear layer (W) to create bottleneck output (U). Finally, U is fed to a classifier to predict the class. The visual concepts are obtained by decomposing the prediction into its elements before summation and visual attention is performed on its tokens.

This figure shows the training and concept labeling process for the concept labeler module used as a baseline in the paper. The process involves using the CLIP vision encoder to extract feature activation maps. A DropBlock technique is applied to simulate a feature map labeling scenario. Then, a concept labeling process is performed where these features are used to train a classifier to predict textual concepts. The output is a set of concept labels corresponding to these features.

This figure visualizes feature activation maps from different neurons of a Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16) model. Each image shows a different neuron’s activation map overlaid on the input image. The leftmost image in each row shows the neuron with the highest activation, generally corresponding to the main object in the image. The other neurons within the same row highlight different features or parts of the object, demonstrating that various neurons are specialized for encoding different aspects of the visual input.

This figure shows the deletion and insertion curves generated by successively removing and adding the identified visual concepts in the order of importance. The deletion curve shows the class score decreasing as more concepts are removed, while the insertion curve shows the class score increasing as more concepts are added. The similarity score is multiplied by 2.5.

This figure illustrates the process of interpreting CLIP’s zero-shot image classification from the perspective of mutual knowledge between vision and language modalities. It shows how visual and textual inputs are mapped into a shared embedding space, and how this space is used to interpret the classification decisions. The figure also illustrates how the authors’ approach uses textual concept-based explanations to analyze the shared knowledge and zero-shot predictions.

This figure shows four examples of how the model identifies and extracts multimodal concepts from visual input. Each example visualizes different parts of an object and their corresponding textual concepts. The textual concepts are fine-grained and descriptive, going beyond general labels to highlight specific visual features. This method helps to break down complex visual features into smaller, more manageable units that contribute to the model’s prediction.

This figure visualizes the mutual concepts identified by both vision and language encoders of CLIP for two example zero-shot predictions. The first example shows mutual concepts that are highly relevant to the prediction of a flute (e.g., musical instrument, mouthpiece). The second example depicts mutual concepts that are less specific and relevant to the prediction of a moped (e.g., two-wheeled vehicle, wheels). This illustrates how the strength of mutual knowledge between the two encoders can vary depending on the specific class and the prediction.

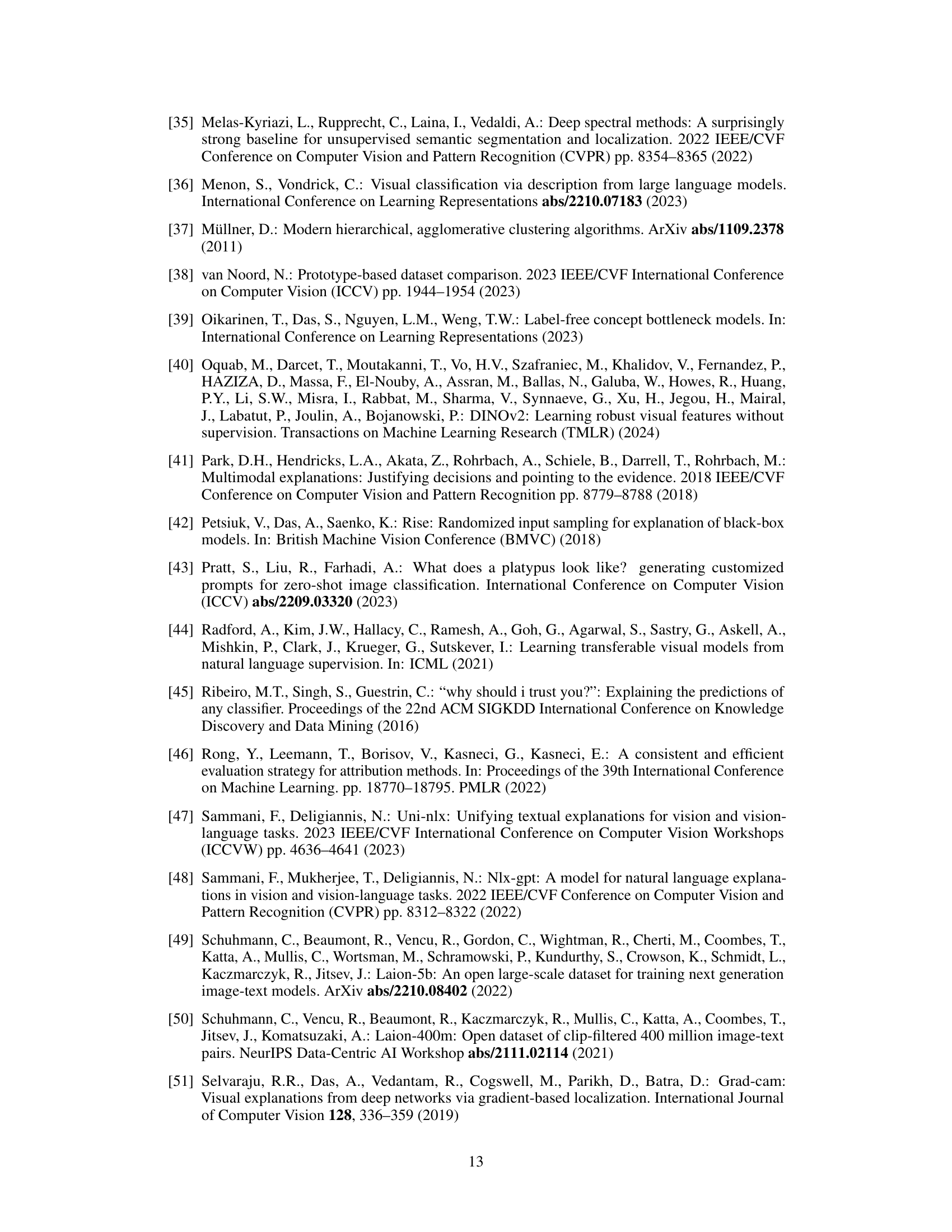

More on tables

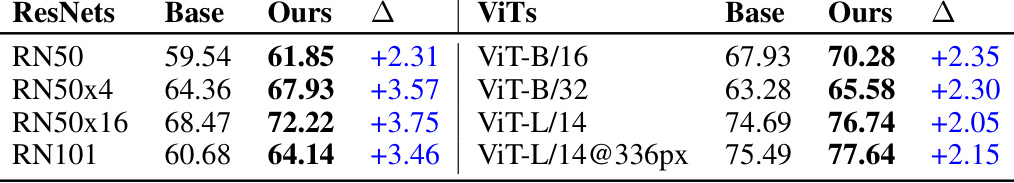

This table presents the zero-shot classification accuracy results on the ImageNet validation set for various CLIP models. It compares the performance of CLIP models using the proposed multimodal concepts against existing baselines. The table shows the baseline accuracy, the accuracy achieved using the authors’ multimodal concepts, and the improvement in accuracy resulting from using the proposed method. Both ResNet and ViT architectures are included in the comparison.

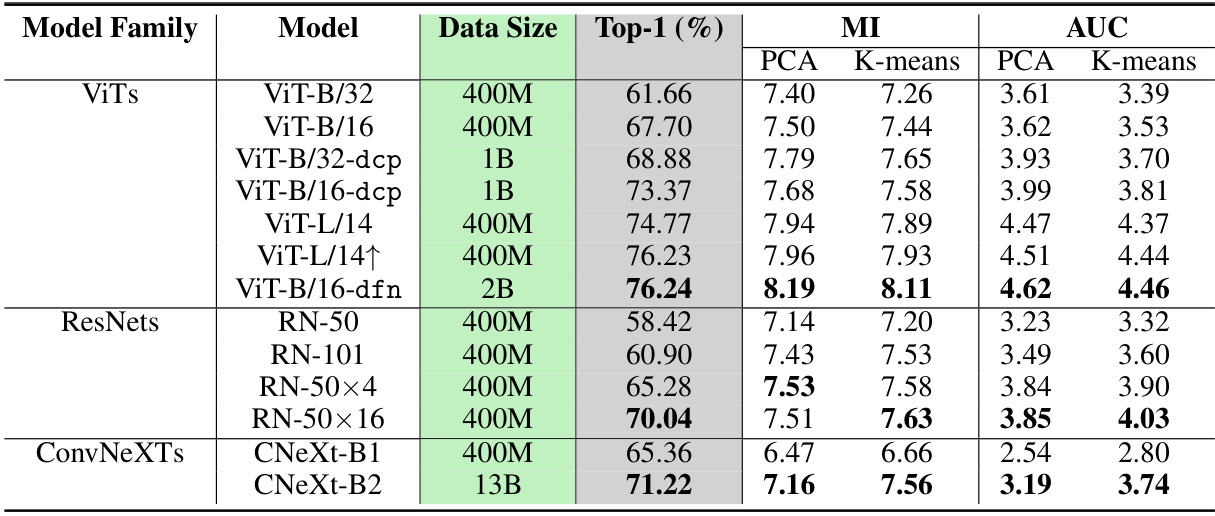

This table presents the Mutual Information (MI) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for thirteen different CLIP models. The models vary in architecture (ViTs, ResNets, ConvNeXTs), size, and pretraining datasets (400M, 1B, 2B). Both PCA and K-means clustering methods were used for feature extraction. The table also includes the Top-1 accuracy for each model on the ImageNet validation set. This data allows for analysis of the relationship between model architecture, size, pretraining data, feature extraction method, and the strength of shared knowledge between the vision and language encoders of CLIP as measured by MI and AUC.

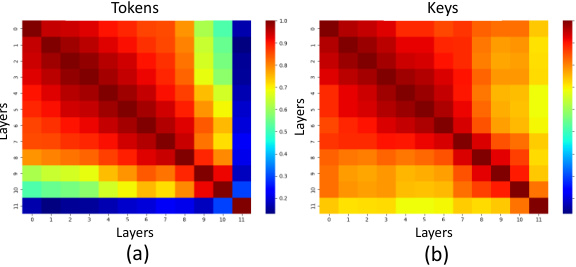

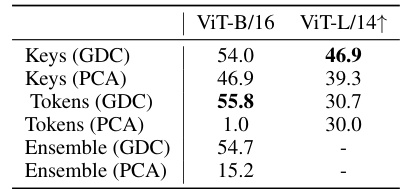

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to determine the best approach for extracting prominent image patches. Three types of visual features were compared: tokens and keys from the last attention layer of the Vision Transformer, and an ensemble of both. Two decomposition methods were used: Graph Decomposition (GDC) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The table shows the CorLoc (Correct Localization) metric for each combination of feature type and decomposition method, indicating the percentage of samples where the identified patch accurately represents the ground truth object. The results highlight the superior performance of GDC, especially when using token features.

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed multimodal concepts in improving the zero-shot classification accuracy of CLIP models. It compares the zero-shot accuracy achieved by using the authors’ multimodal concepts against baseline methods from previous work ([36, 43]). The comparison is done separately for ResNet and ViT architectures, showing the improvement in accuracy provided by the multimodal concepts. The ‘A’ column indicates the increase in accuracy relative to the baseline.

This table presents the Mutual Information (MI) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores obtained for various CLIP models using both PCA and K-means methods. The models are categorized into families (ViTs, ResNets, and ConvNeXts), each with variations in architecture, size, and pretraining datasets. The table also shows the Top-1 accuracy achieved by each model on the ImageNet validation set. The data helps in understanding the relationship between model characteristics (size, architecture, training data), the MI and AUC values which represent shared knowledge between vision and text encoders, and the resulting zero-shot classification accuracy.

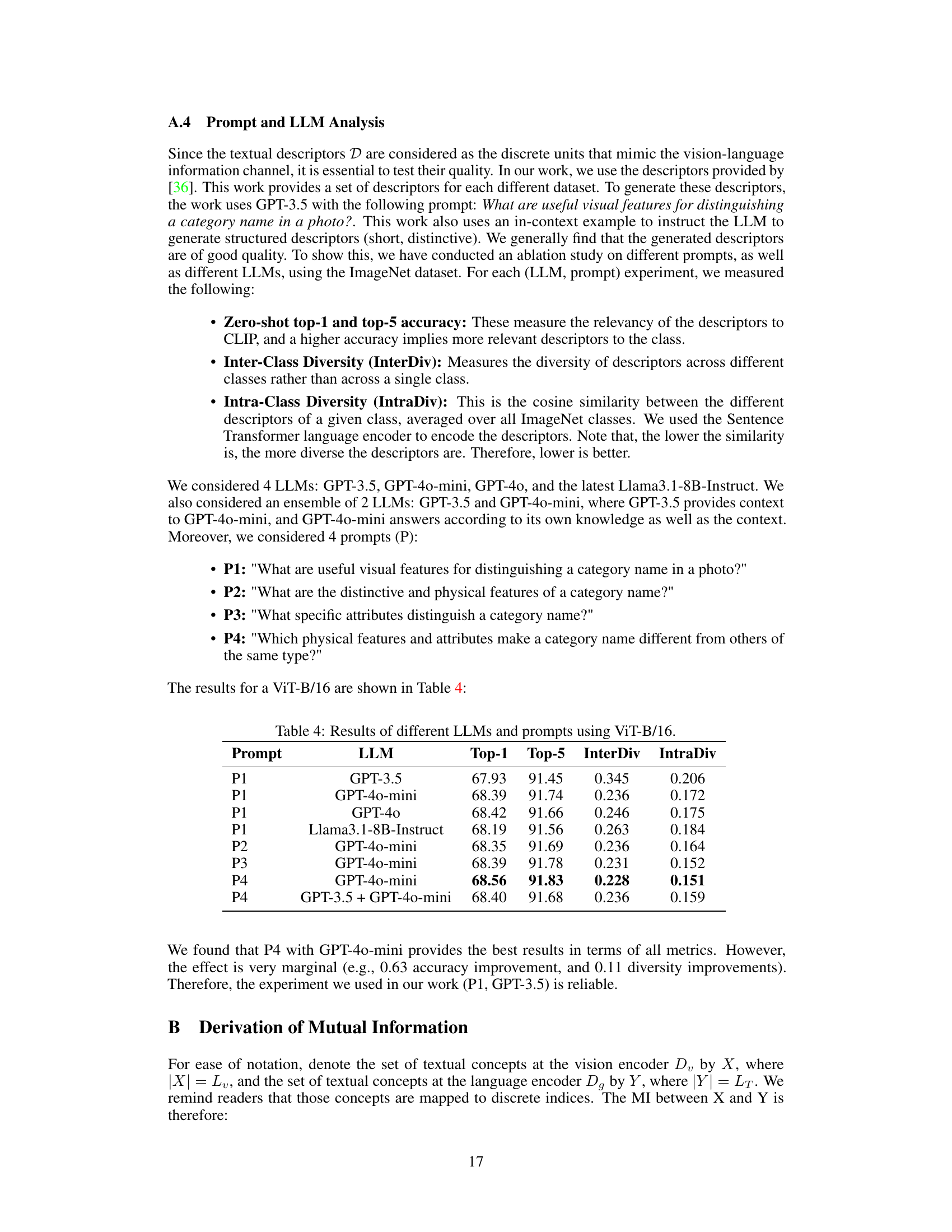

This table presents the ablation study on different prompts and LLMs for generating textual descriptors. Four prompts (P1-P4) and four LLMs (GPT-3.5, GPT-40-mini, GPT-40, Llama3.1-8B-Instruct) along with an ensemble of GPT-3.5 and GPT-40-mini were tested. The table shows the zero-shot top-1 and top-5 accuracy, inter-class diversity (InterDiv), and intra-class diversity (IntraDiv) for each combination. InterDiv measures the diversity of descriptors across classes, while IntraDiv measures the similarity between descriptors within a class (lower is better). The results highlight the impact of prompt engineering and LLM choice on descriptor quality, which affects the downstream image classification performance.

This table presents the performance comparison between the proposed multimodal explanation method and three established baselines (MM-CBM, MM-ProtoSim, Feature Maps) using four evaluation metrics (Deletion, Insertion, AccDrop, AccInc). The baselines require training while the proposed method is training-free. The metrics measure the impact on model accuracy of adding or removing concepts. Higher Insertion and AccInc scores, and lower Deletion and AccDrop scores indicate better explanation performance.

This table presents the mutual information (MI) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) for various ViT models on the Places365 dataset. The models are grouped by size (Model Size section) and pretraining data (Pretrain Data section). For each model, the top-1 accuracy on the dataset is also provided. This allows for a comparison of the MI and AUC scores in relation to model architecture and the size and quality of pretraining data used.

This table presents the Mutual Information (MI) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) for different CLIP models evaluated on the Food-101 dataset. The models vary in size and pretraining dataset size (1B or 2B images). The MI quantifies the shared information between the vision and language encoders. The AUC describes the MI dynamics as concepts are sequentially removed, indicating the robustness of the shared knowledge. Higher AUC values suggest stronger shared knowledge.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed multimodal explanations against three baselines on four evaluation metrics: Deletion, Insertion, Accuracy Drop, and Accuracy Increase. The baselines represent existing single-modality methods adapted to the multimodal setting. The proposed method does not require training, while the baselines do. The metrics assess how well the explanations identify important features for the model’s predictions. Higher Insertion and Accuracy Increase scores are better, while lower Deletion and Accuracy Drop scores are better.

Full paper#