TL;DR#

Deep learning’s success hinges on scaling laws, but the underlying reasons for these laws remain unclear, particularly for transformer models. Existing theories often fail to capture real-world observations where data often resides on lower-dimensional manifolds. This gap motivates a deeper understanding of how data geometry influences model behavior.

This research bridges this gap by developing novel statistical estimation and approximation theories for transformer networks trained on intrinsically low-dimensional data. The authors demonstrate a power law relationship between generalization error and both data size and model size, where the exponents depend on the intrinsic dimension. Their theoretical predictions align well with empirical results from large language models. This work not only improves our theoretical understanding but also provides practical guidelines for designing and training more efficient, data-conscious transformer models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with transformer neural networks and large language models. It provides rigorous theoretical foundations for understanding scaling laws, offering practical guidance for model design and training. The findings challenge existing theoretical limits and open new avenues for optimizing LLMs on low-dimensional data, thereby improving efficiency and performance. This work is highly relevant to the current trends in deep learning and could significantly influence future research.

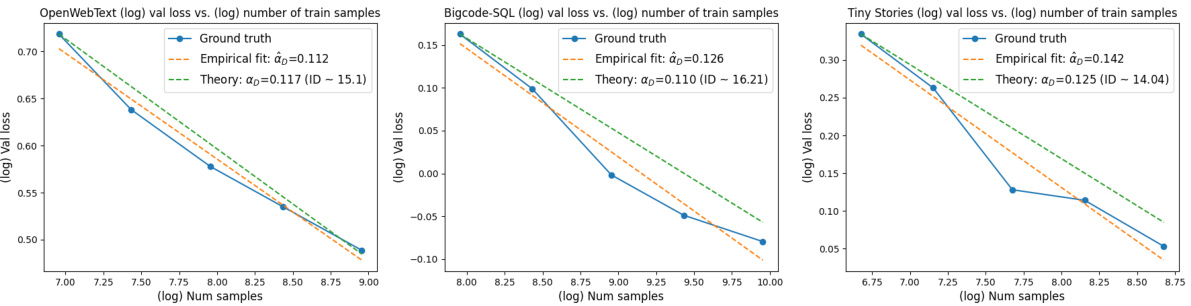

Visual Insights#

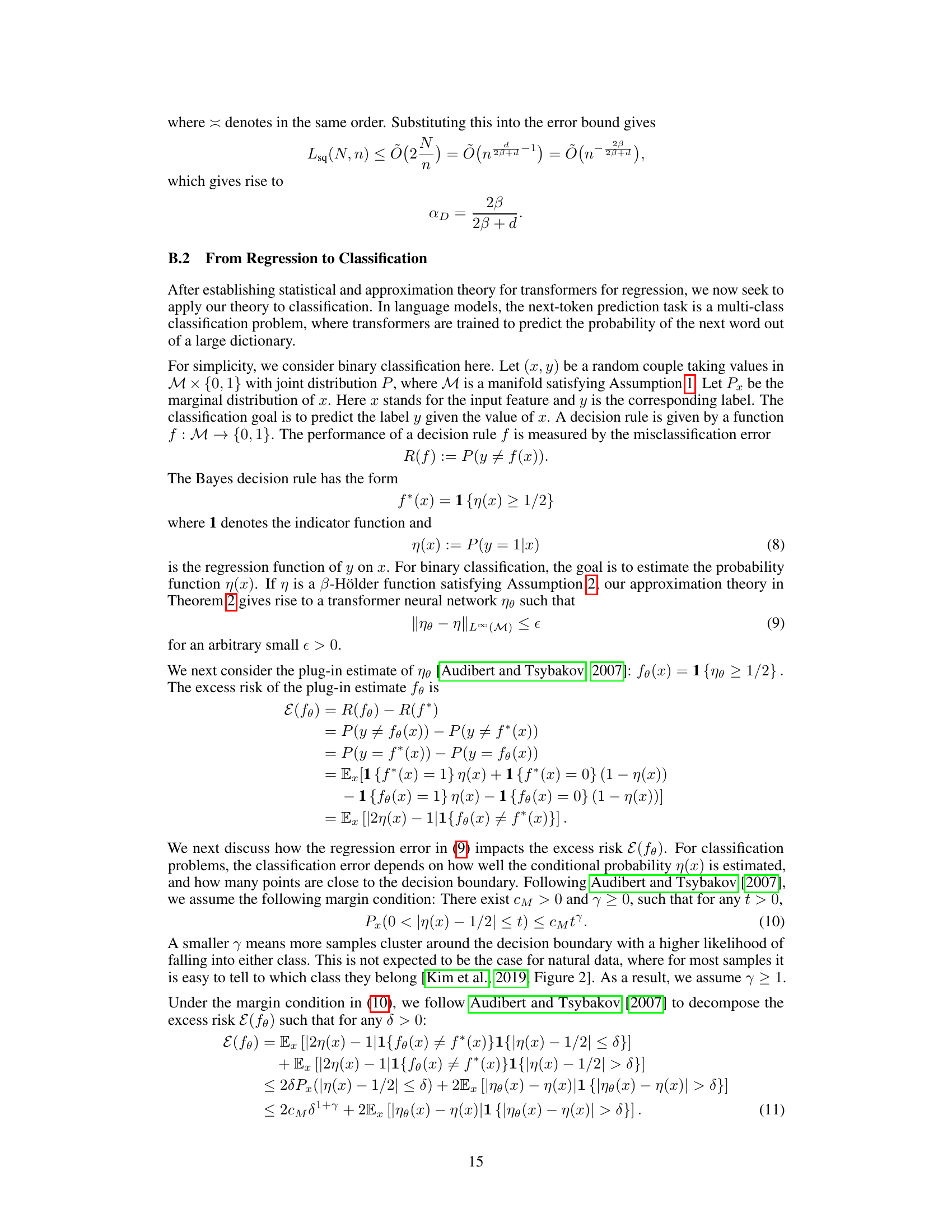

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the transformer network used to approximate a function f on a low-dimensional manifold M. The input x is first embedded and then processed by a series of transformer blocks. The architecture uses a shallow network (logarithmic depth) to leverage the low dimensionality. The process involves projecting the input onto local tangent spaces and approximating the function locally using Taylor polynomials. A separate subnetwork calculates indicator functions that select the relevant local approximations, which are then combined to produce the final approximation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Diagram of the transformer architecture constructed in Theorem 2. T computes approximations of f(x) on each local chart Un ≤ M by first projecting x to the tangent coordinates in Rd via on(x) and then approximating f(x) with local Taylor polynomials. A shallow sub-network computes indicators 1U for each local chart in parallel. The results of the two sub-networks are then multiplied together and summed to produce the final result. Here H₁ denotes the embedding matrix before the ith transformer block Bi.

🔼 This table lists the default hyperparameter settings used for all training jobs in the research. It specifies architectural hyperparameters such as the number of layers, attention heads, embedding dimension, and context length, as well as optimization hyperparameters including the optimizer used (AdamW), learning rate scheduling (linear warmup and cosine decay), and batch size. All training was performed on four NVIDIA RTX 6000 GPUs.

read the caption

Table 2: Default hyperparameters for all training jobs. All training was done on four RTX 6000s.

In-depth insights#

Transformer Scaling Laws#

The concept of “Transformer Scaling Laws” explores the relationship between a transformer model’s performance and its size (number of parameters) and the amount of training data. Empirical observations show power-law relationships, suggesting that increasing model and data size improves performance, but at diminishing returns. This research rigorously investigates this phenomenon using statistical estimation and approximation theories, focusing on intrinsically low-dimensional data. The study’s key contribution is linking the scaling exponents to the intrinsic dimension of the data, thereby providing a theoretical basis for understanding the observed power laws. The findings not only explain existing transformer scaling laws but also offers a framework for predicting future model performance based on intrinsic data dimensionality, offering significant implications for efficient model design and training.

Manifold Hypothesis#

The manifold hypothesis posits that high-dimensional data, while seemingly complex, often resides on or near a lower-dimensional manifold embedded within the higher-dimensional space. This implies that the data’s intrinsic dimensionality is significantly smaller than its ambient dimensionality. This lower-dimensional structure reflects underlying relationships and constraints within the data, simplifying learning tasks by reducing the complexity of the data representation. Exploiting this inherent structure offers substantial advantages in machine learning, potentially leading to improved model efficiency, reduced computational cost, and enhanced generalization performance. However, the manifold hypothesis is not without limitations. Identifying the precise manifold and its intrinsic dimension can be challenging, requiring robust dimensionality reduction techniques. Moreover, the effectiveness of the manifold hypothesis is highly dependent on the data’s properties and its suitability for manifold representation. Real-world data might not perfectly conform to a smooth manifold structure, potentially limiting the applicability of the hypothesis in such cases.

Approximation Theory#

The Approximation Theory section of this research paper is crucial as it rigorously establishes the capability of transformer networks to approximate functions, particularly focusing on functions defined on low-dimensional manifolds. The key finding is that a relatively shallow transformer network (logarithmic depth) can achieve universal approximation, unlike deeper feedforward networks that suffer from the curse of dimensionality. This theoretical result is supported by the construction of a specific transformer architecture optimized for approximation on manifolds. The theory provides an important theoretical foundation for understanding the scaling laws observed in practice, especially how the intrinsic dimension of data influences model performance and generalizability. The impact on the statistical estimation theory is particularly important, showing how the approximation error relates to generalization error and influencing the scaling laws. The mathematical rigor and explicit construction of the approximating network demonstrate significant advancement in understanding the theoretical underpinnings of transformer networks, bridging the gap between theory and empirical observations.

LLM Experiments#

In a hypothetical research paper section titled “LLM Experiments,” I would expect a thorough exploration of large language model (LLM) training and evaluation. This would likely involve pre-training multiple LLMs on diverse datasets, varying parameters like model size, training data size, and compute resources. The experiments should aim to validate the theoretical scaling laws proposed earlier in the paper. This could involve plotting generalization error against these factors in log-log plots to assess the agreement between empirical observations and theoretical predictions. Analysis of intrinsic dimensionality’s effect on the scaling laws would be crucial, potentially comparing LLMs trained on data with differing intrinsic dimensions. The evaluation would also likely extend to downstream tasks to assess the practical implications of the scaling laws, providing insights into optimal resource allocation for LLM training. The results section would need to demonstrate the statistical significance of findings, including a discussion of error bars and confidence intervals. Finally, a detailed breakdown of experimental setup and hyperparameters would be necessary for ensuring reproducibility. A robust experiment design would be essential to draw valid conclusions about the LLM scaling laws and the role of intrinsic dimensionality.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass more complex model architectures, such as those with attention mechanisms, would enhance the model’s applicability and predictive power. Investigating the impact of data heterogeneity on scaling laws is crucial, as real-world data often exhibits diverse characteristics. Furthermore, developing more robust methods for estimating intrinsic dimensionality is needed to improve the accuracy and reliability of predictions. Finally, the connection between scaling laws and other model properties, like generalization ability, remains an important area of study, demanding further investigation. These efforts can help establish a more comprehensive and robust understanding of deep learning scaling laws.

More visual insights#

More on figures

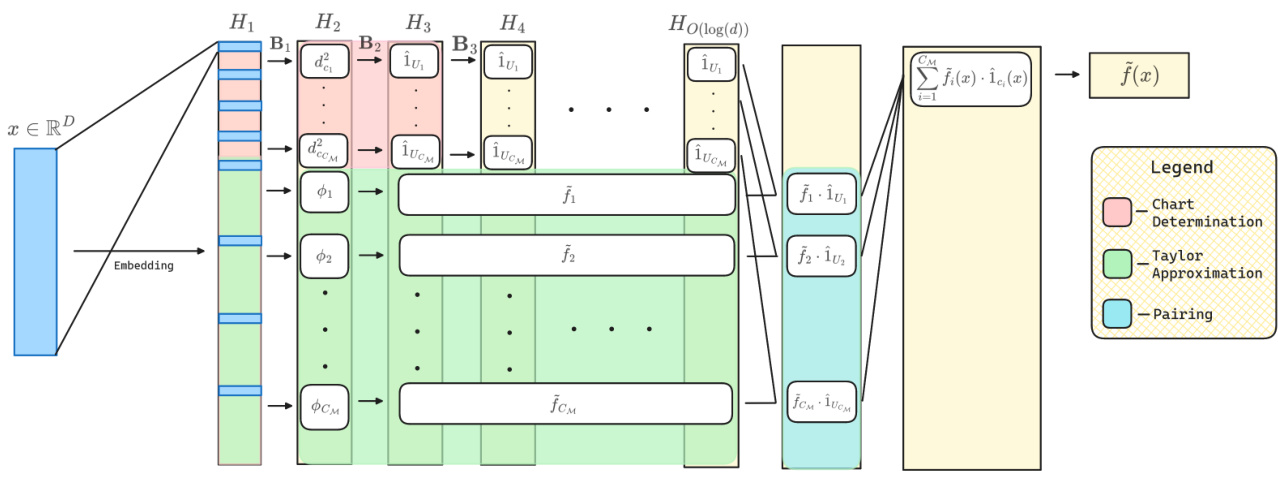

🔼 This figure compares the observed and predicted data scaling laws for three different language model pretraining datasets: OpenWebText, The Stack-SQL, and Tiny Stories. The plots show the validation loss (a measure of generalization error) as a function of the number of training samples, shown on a log-log scale. Each dataset has its own plot, showing the ground truth, an empirical fit of the data, and a theoretical prediction from the authors’ model. The close agreement (±0.02) between the empirical and theoretical exponents supports the authors’ theory that the intrinsic dimension of the data significantly affects the scaling laws. The differences between the datasets highlight varying levels of complexity in the pretraining data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Observed and predicted data scaling laws on OpenWebText, The Stack-SQL, and Tiny Stories pretraining datasets. All estimates are close (±0.02) and appear to reflect varying levels of pretraining data complexity. Note: âp denotes the empirically observed data scaling exponent and AD denotes the theoretically estimated exponent.

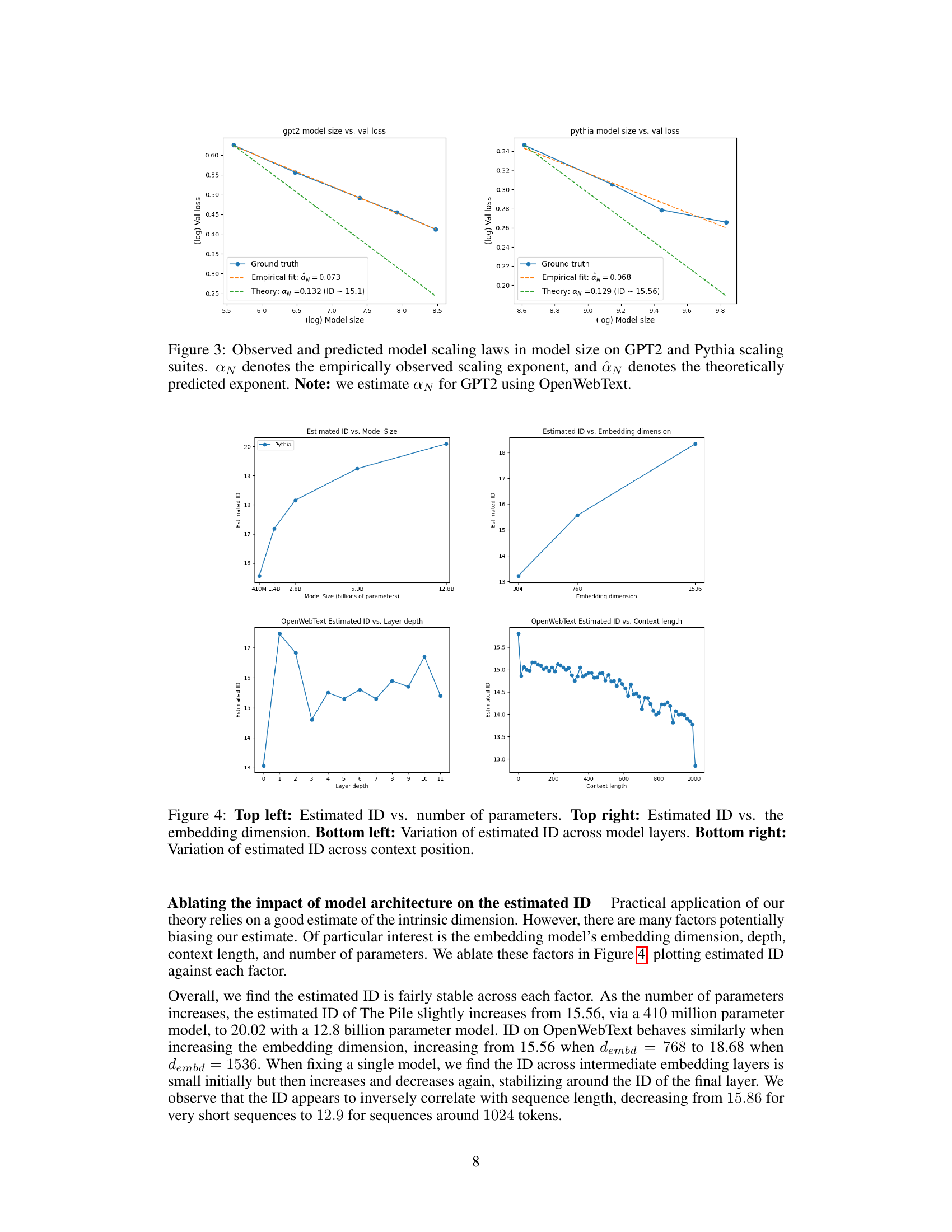

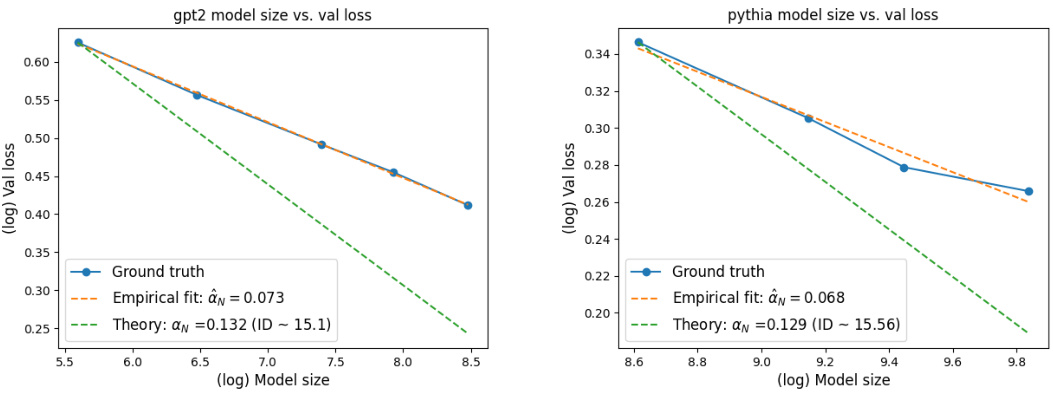

🔼 This figure shows the observed and predicted model scaling laws for GPT-2 and Pythia language models. The observed scaling exponent (α̂N) is derived from empirical data, while the theoretical exponent (αN) is predicted by the authors’ theory, which incorporates the intrinsic dimension of the data. The figure visually compares these two exponents, demonstrating the agreement between the theoretical predictions and empirical observations, at least for GPT-2. The differences are attributed to factors such as undertraining of the largest models and the intrinsic entropy of the data distribution.

read the caption

Figure 3: Observed and predicted model scaling laws in model size on GPT2 and Pythia scaling suites. α̂N denotes the empirically observed scaling exponent, and αN denotes the theoretically predicted exponent. Note: we estimate αN for GPT2 using OpenWebText.

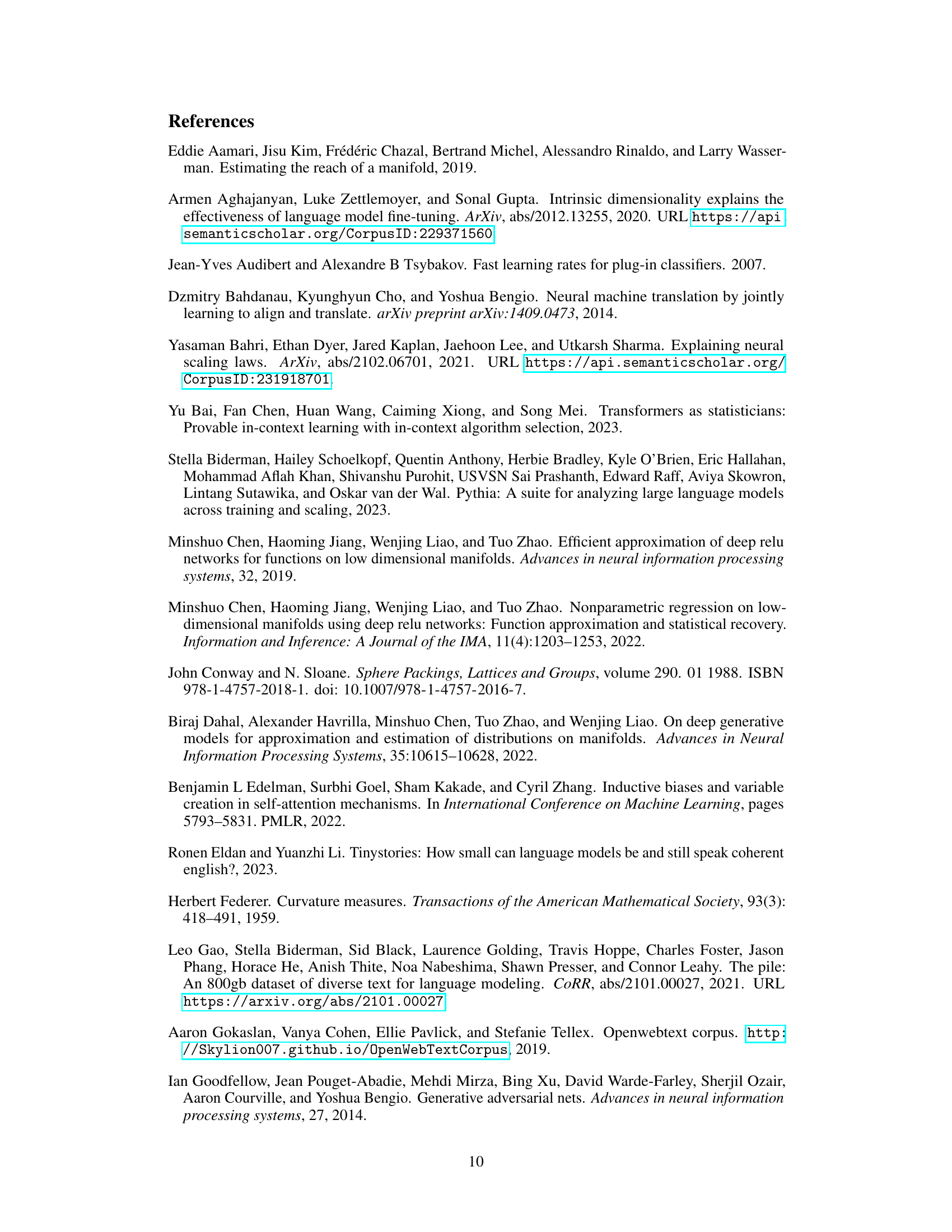

🔼 This figure explores the impact of various model architecture hyperparameters on the estimated intrinsic dimension (ID) of the data. The four subplots show how estimated ID changes with respect to model size (in billions of parameters), embedding dimension, layer depth, and context length, respectively. The results reveal a degree of stability in the estimated ID across these factors, with only minor changes observed in certain ranges.

read the caption

Figure 4: Top left: Estimated ID vs. number of parameters. Top right: Estimated ID vs. the embedding dimension. Bottom left: Variation of estimated ID across model layers. Bottom right: Variation of estimated ID across context position.

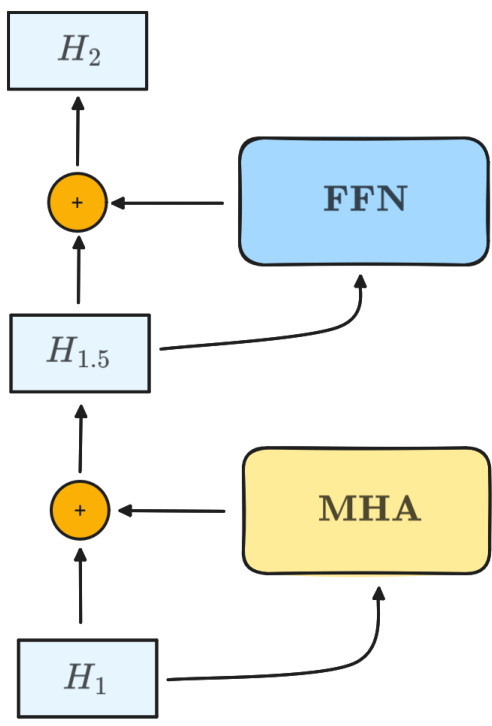

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of a single transformer block. It consists of a multi-head attention (MHA) layer and a feed-forward (FFN) layer. The input to the block is H1. The MHA layer processes H1, and the output of the MHA layer is added to H1. The result is then fed into the FFN layer. The FFN layer’s output is added to the output of the MHA layer to produce the final output of the block, H2.

read the caption

Figure 5: Diagram of transformer block.

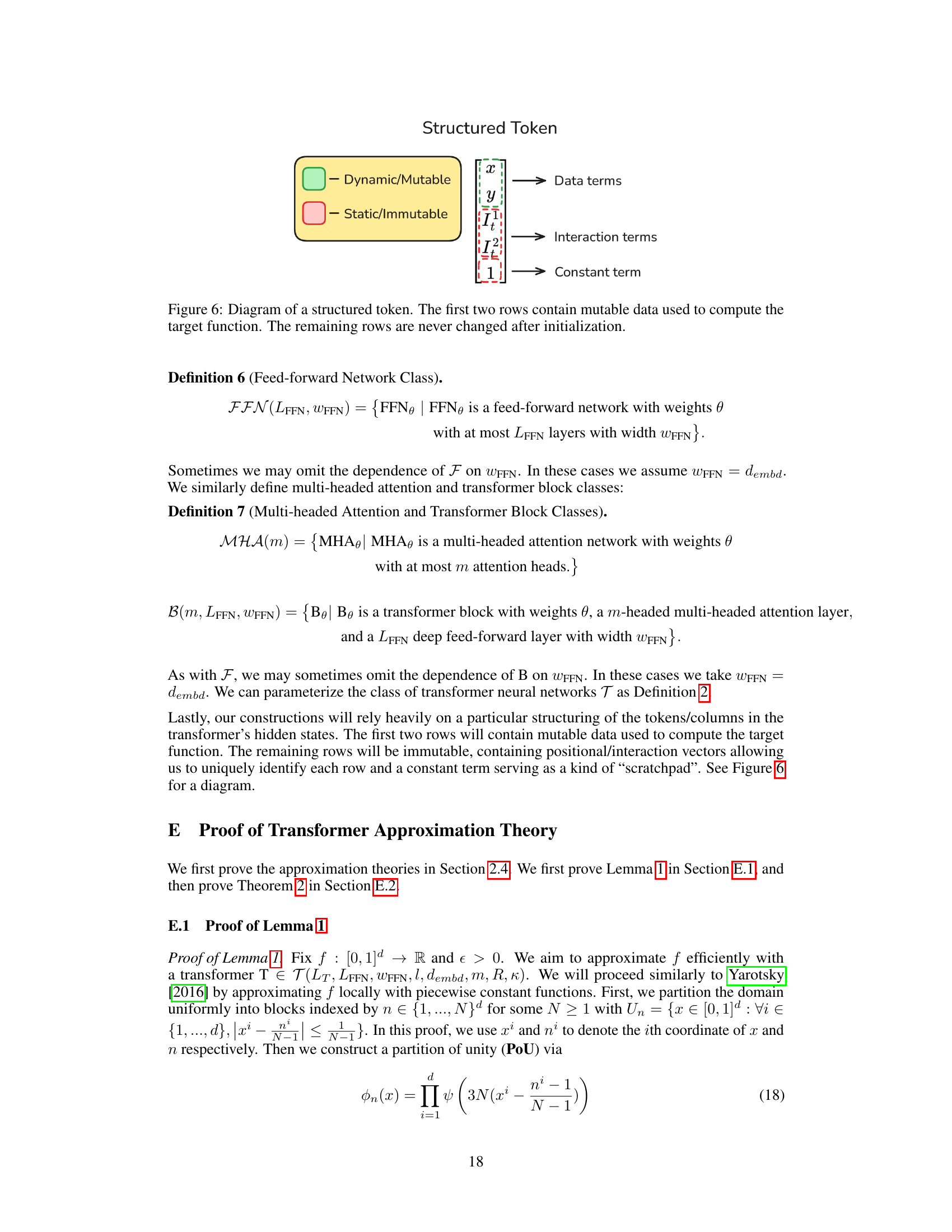

🔼 This figure shows the structure of a structured token used in the transformer neural network. The token is divided into three parts: data terms (dynamic/mutable), interaction terms (static/immutable), and a constant term (static/immutable). The data terms are used to compute the target function, while the interaction and constant terms are used for other purposes. This structure is important for the efficiency of the transformer network.

read the caption

Figure 6: Diagram of a structured token. The first two rows contain mutable data used to compute the target function. The remaining rows are never changed after initialization.

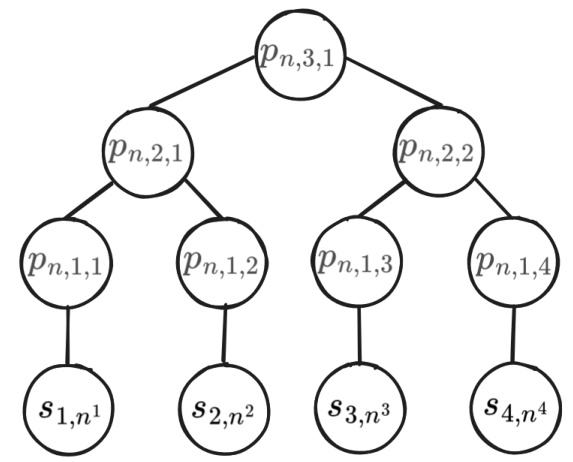

🔼 This figure shows the recursive assembly of partial products from constituent terms. Each node represents a partial product, and the leaves represent the constituent terms (si,ni). The figure illustrates how the partial products are computed recursively, starting from the constituent terms and combining them pairwise at each level of the tree until the final partial product (pn,3,1) is obtained. The structure of the tree reflects the recursive nature of the computation, with each level of the tree corresponding to a step in the process.

read the caption

Figure 7: Recursive assembly of partial products from constituent terms. Formally, Pn,k,i = Pn,k−1,2i−1Pn,k−1,2i With Pn,1,i = Si,ni for n ∈ {1, ..., N}d, 1 ≤ k ≤ log2(d), 1 ≤ i ≤ 2d.

Full paper#