TL;DR#

Generative Flow Networks (GFlowNets) offer an efficient way to sample from complex distributions, crucial in various machine learning applications. However, training them using traditional divergence measures proved ineffective due to high gradient variance. Current training relies on minimizing the difference between proposal and target distributions, which can be less efficient.

This research paper tackles the limitations of current GFlowNet training. It introduces innovative variance-reduction techniques, using control variates, that substantially improve gradient estimation. The researchers also formally establish the connection between GFlowNets and HVI for broader distribution types, paving the way for new algorithmic improvements.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with generative models and variational inference. It bridges the gap between GFlowNet training and HVI, offering new training algorithms and variance reduction techniques that enhance efficiency and stability. This opens up avenues for advancements in diverse applications leveraging generative models.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates how the choice of the α parameter in Renyi-α and Tsallis-α divergences affects the learning dynamics of GFlowNets. Specifically, it shows early-stage training results for sampling from a homogeneous mixture of Gaussian distributions. When α is large and negative (α = -2), the GFlowNet covers the target distribution’s modes broadly. Conversely, a large positive α (α = 2) causes the model to focus on a single high-probability region. An intermediate value of α = 0.5 achieves the most accurate approximation of the target distribution.

read the caption

Figure 1: Mode-seeking (α = 2) versus mass-covering (α = -2) behaviour in α-divergences.

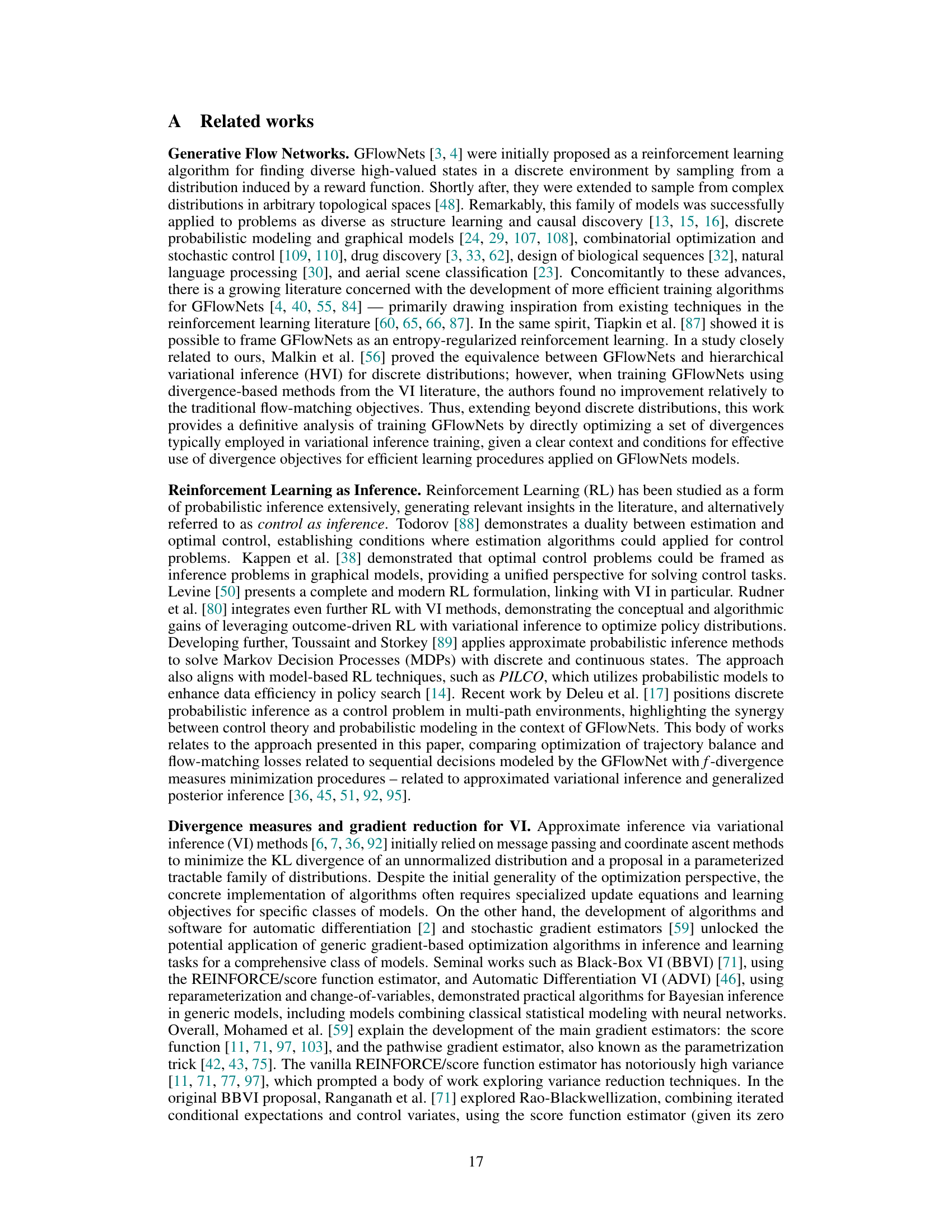

🔼 This table presents the average L1 error for each of the five generative tasks (Bayesian phylogenetic inference, sequence generation, set generation, Gaussian mixtures, and banana-shaped distribution) using different loss functions (TB, Reverse KL, Forward KL, Renyi-alpha, and Tsallis-alpha). The results show that minimizing divergence-based objectives often achieves similar or better accuracy than minimizing the trajectory balance (TB) loss, a commonly used method in GFlowNet training.

read the caption

Table 1: Divergence minimization achieves better than or similar accuracy compared to enforcing TB.

In-depth insights#

GFlowNet Training#

GFlowNet training presents unique challenges due to the intractability of the target distribution. Traditional divergence minimization methods often fail, highlighting the need for alternative approaches. The paper explores the relationship between GFlowNets and hierarchical variational inference (HVI), extending this connection to more general spaces. A key contribution is the development of variance-reducing control variates to improve the efficiency of gradient estimation for divergence-based training objectives. Experiments demonstrate that divergence-based training, especially when coupled with control variates, can be more efficient than existing methods in many cases, indicating a promising direction for future research in GFlowNet development. The effectiveness of different divergence measures is also empirically investigated, showing the importance of considering the properties of the target distribution when choosing an objective function. The results highlight the potential for algorithmic advancements inspired by the divergence minimization perspective.

Divergence Measures#

The section on Divergence Measures would explore various metrics for quantifying the difference between probability distributions, crucial for training generative models. It would likely delve into classic divergences like Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, examining their properties and suitability for the specific generative model. Beyond KL divergence, the discussion might extend to other families like f-divergences, encompassing Renyi and Tsallis divergences, highlighting their flexibility and potential advantages over KL divergence. A key aspect would be the computational challenges associated with these measures, particularly in high-dimensional spaces, and how these challenges are addressed. Furthermore, the section would likely involve empirical comparisons of various divergence measures. This would involve analyzing training convergence speed and the quality of generated samples under different divergence measures, providing valuable insights into the practical effectiveness of each. The choice of divergence would be shown to impact the trade-off between mode-seeking and mass-covering behavior. Finally, the discussion would tie the selected divergences to the theoretical underpinnings of variational inference, illustrating a crucial connection between the training methodology and its theoretical foundation.

Variance Reduction#

The concept of variance reduction is crucial for efficient training of machine learning models, particularly in settings with high-variance gradient estimates, such as those encountered when training generative flow networks (GFlowNets). The authors address this challenge by developing and implementing control variates (CVs) for variance reduction in gradient estimation, focusing on the REINFORCE leave-one-out estimator. Their approach leverages the correlation between the target function and a control variate to reduce the variance of the estimator without introducing bias. The use of CVs significantly improves the stability and speed of convergence during training, as demonstrated empirically. This is especially important in the context of GFlowNets, where the gradient estimates often exhibit high variance due to the nature of stochastic gradient-based training. The proposed control variates offer a practical and effective approach for enhancing the efficiency and reliability of GFlowNet training, bridging a gap between theoretical advancements and real-world application.

Topological Spaces#

Extending the analysis of generative flow networks (GFlowNets) to topological spaces offers significant theoretical advantages. It moves beyond the limitations of discrete, finite settings, allowing for the modeling of continuous distributions and more complex structures. This generalization provides a more robust framework for understanding the relationship between GFlowNets and hierarchical variational inference (HVI), a key connection that underpins the training methodology. The use of topological spaces allows for a deeper exploration of the underlying mathematical structures of GFlowNets, providing a more rigorous foundation for further algorithmic development and potentially opening new avenues for applications in various fields. The ability to work with continuous state spaces also has significant practical implications, as many real-world problems involve continuous data and distributions. This generalization enhances the applicability and versatility of GFlowNets for diverse machine learning tasks. Formalizing the connection between GFlowNets and HVI in this broader context strengthens the theoretical underpinnings of the training process, enabling the development of more efficient and robust algorithms. Furthermore, the expansion into topological spaces facilitates the utilization of advanced mathematical tools and techniques, which can lead to deeper insights and improved model performance.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore variance reduction techniques beyond those presented, potentially leveraging advanced methods from control variates or other variance reduction strategies to further enhance the efficiency and stability of GFlowNet training. Investigating alternative divergence measures, such as those based on Rényi-α or Tsallis-α divergences, could reveal new insights into training dynamics and model performance. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass continuous and hybrid spaces would broaden the applicability of GFlowNets. Furthermore, developing novel applications in complex domains like natural language processing or drug discovery would showcase the power of GFlowNets, necessitating more robust and efficient training methods. Finally, a focus on improved evaluation metrics for assessing the quality of samples generated by GFlowNets is needed to fully evaluate the effectiveness of new training techniques and model architectures.

More visual insights#

More on figures

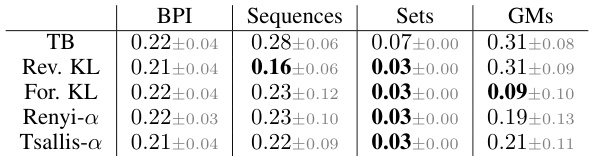

🔼 This figure shows how the variance of estimated gradients changes with the batch size of trajectories used in training GFlowNets. The results compare gradient estimation with and without the use of control variates (CVs). It demonstrates that incorporating CVs significantly reduces the variance, especially noticeable in smaller batch sizes, leading to more stable and efficient training.

read the caption

Figure 2: Variance of the estimated gradients as a function of the trajectories' batch size. Our control variates greatly reduce the estimator's variance, even for relatively small batch sizes.

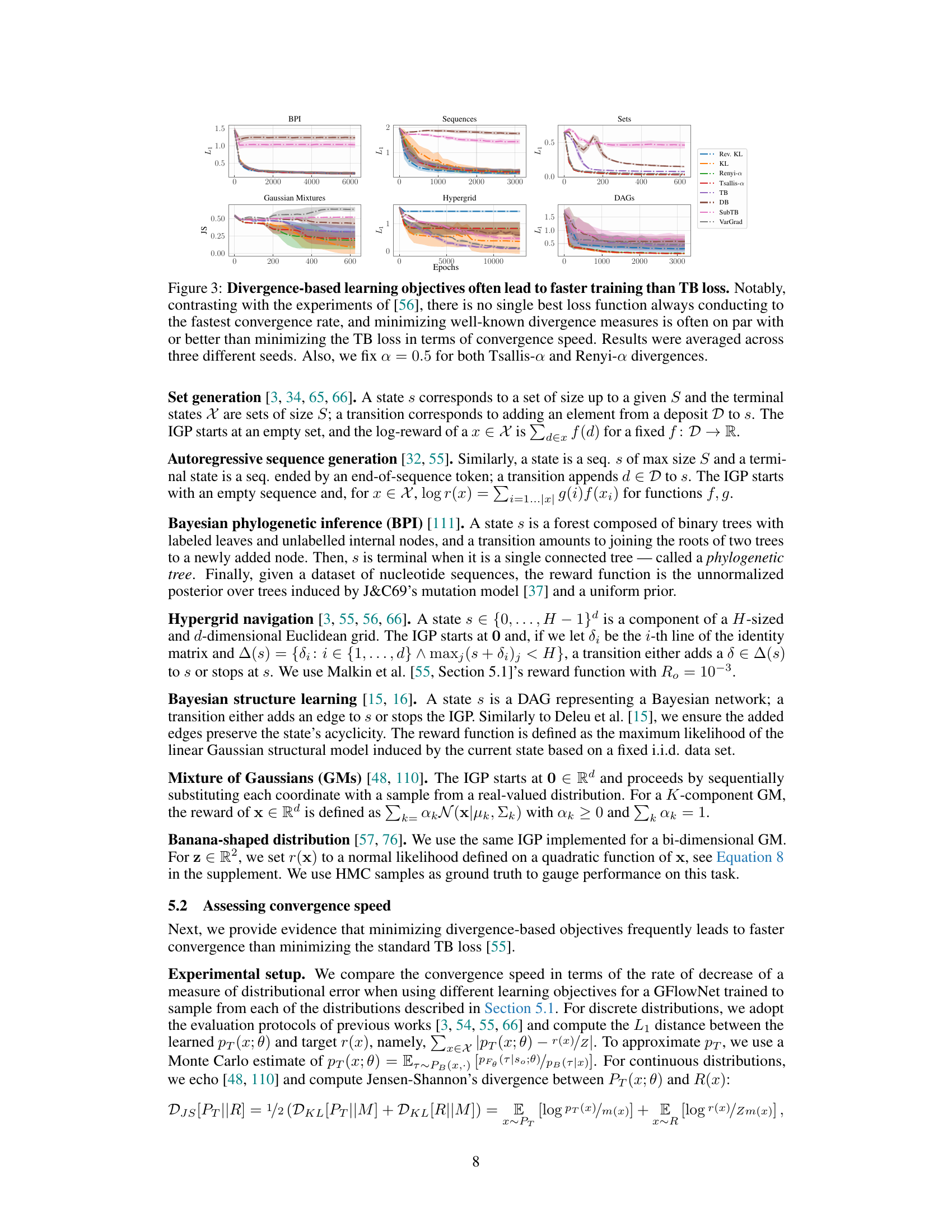

🔼 This figure compares the convergence speed of different divergence-based learning objectives against the trajectory balance (TB) loss for training GFlowNets on various generative tasks. The results show that while there isn’t a single best-performing loss function across all tasks, divergence-based methods frequently achieve comparable or faster convergence compared to the TB loss. The average results across multiple random seeds are presented for each task and loss function, with α fixed at 0.5 for Tsallis-α and Renyi-α divergences.

read the caption

Figure 3: Divergence-based learning objectives often lead to faster training than TB loss. Notably, contrasting with the experiments of [56], there is no single best loss function always conducting to the fastest convergence rate, and minimizing well-known divergence measures is often on par with or better than minimizing the TB loss in terms of convergence speed. Results were averaged across three different seeds. Also, we fix α = 0.5 for both Tsallis-α and Renyi-α divergences.

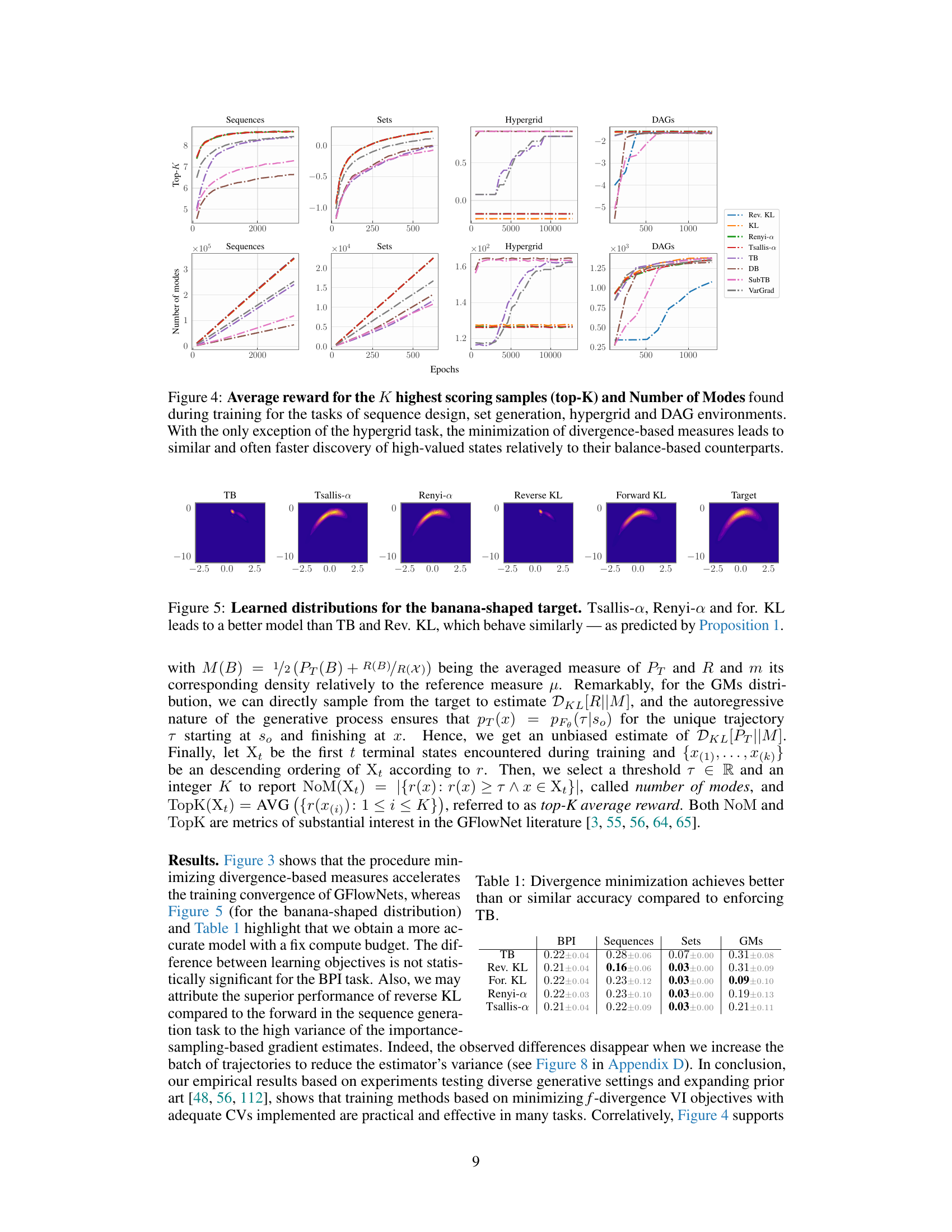

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different loss functions (divergence-based vs balance-based) in four different generative tasks: sequence generation, set generation, hypergrid navigation and directed acyclic graph (DAG) generation. It plots two key metrics: the average reward of the top K samples and the number of modes discovered during training. The results show that divergence-based losses generally lead to faster discovery of high-reward states and a larger number of modes, except in the hypergrid task.

read the caption

Figure 4: Average reward for the K highest scoring samples (top-K) and Number of Modes found during training for the tasks of sequence design, set generation, hypergrid and DAG environments. With the only exception of the hypergrid task, the minimization of divergence-based measures leads to similar and often faster discovery of high-valued states relatively to their balance-based counterparts.

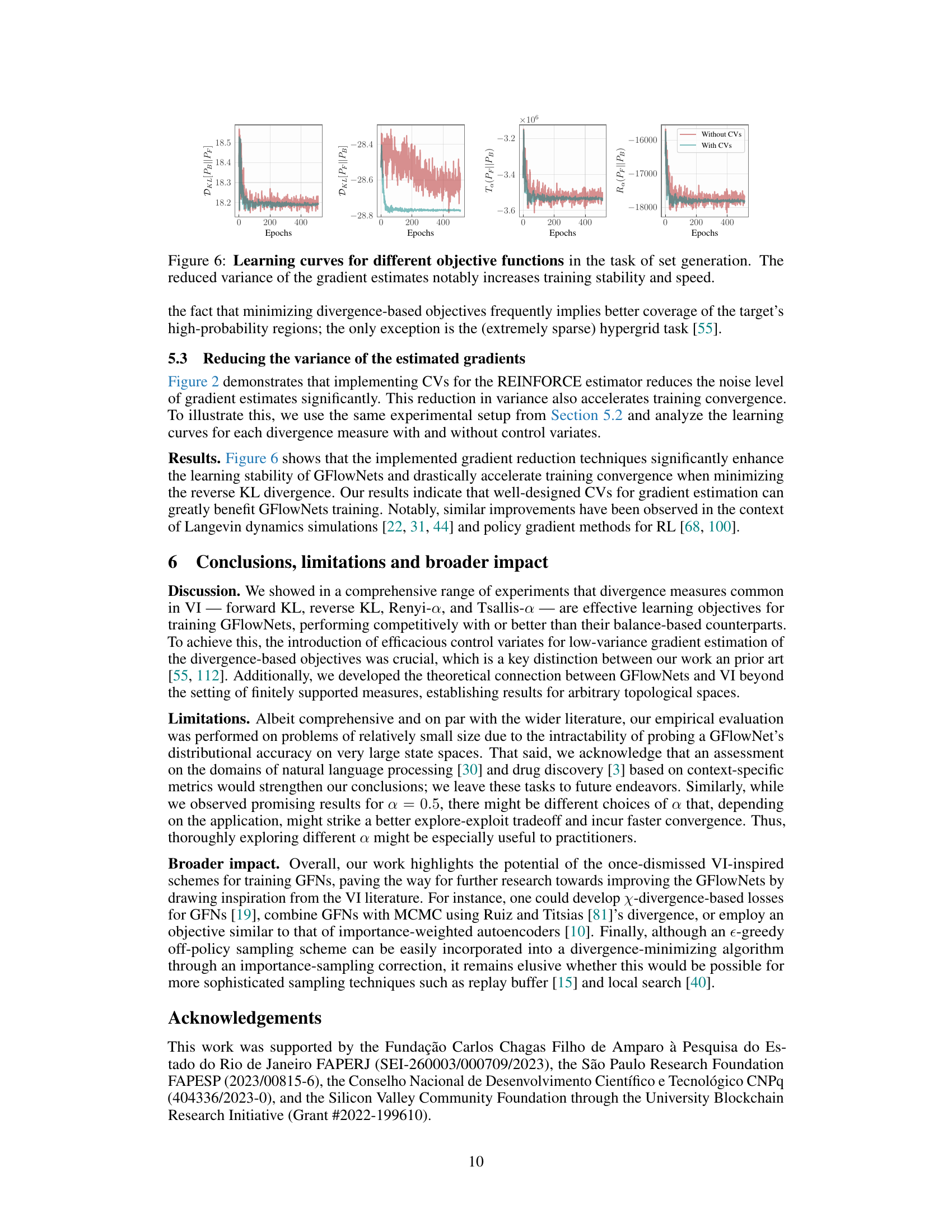

🔼 This figure compares the learned distributions for different divergence measures (TB, Tsallis-α, Renyi-α, Reverse KL, Forward KL) against the target banana-shaped distribution. The heatmaps visually represent the probability density of the learned distributions. It shows that Tsallis-α, Renyi-α, and Forward KL yield better approximations compared to TB and Reverse KL, aligning with the theoretical prediction of Proposition 1.

read the caption

Figure 5: Learned distributions for the banana-shaped target. Tsallis-a, Renyi-a and for. KL leads to a better model than TB and Rev. KL, which behave similarly - as predicted by Proposition 1.

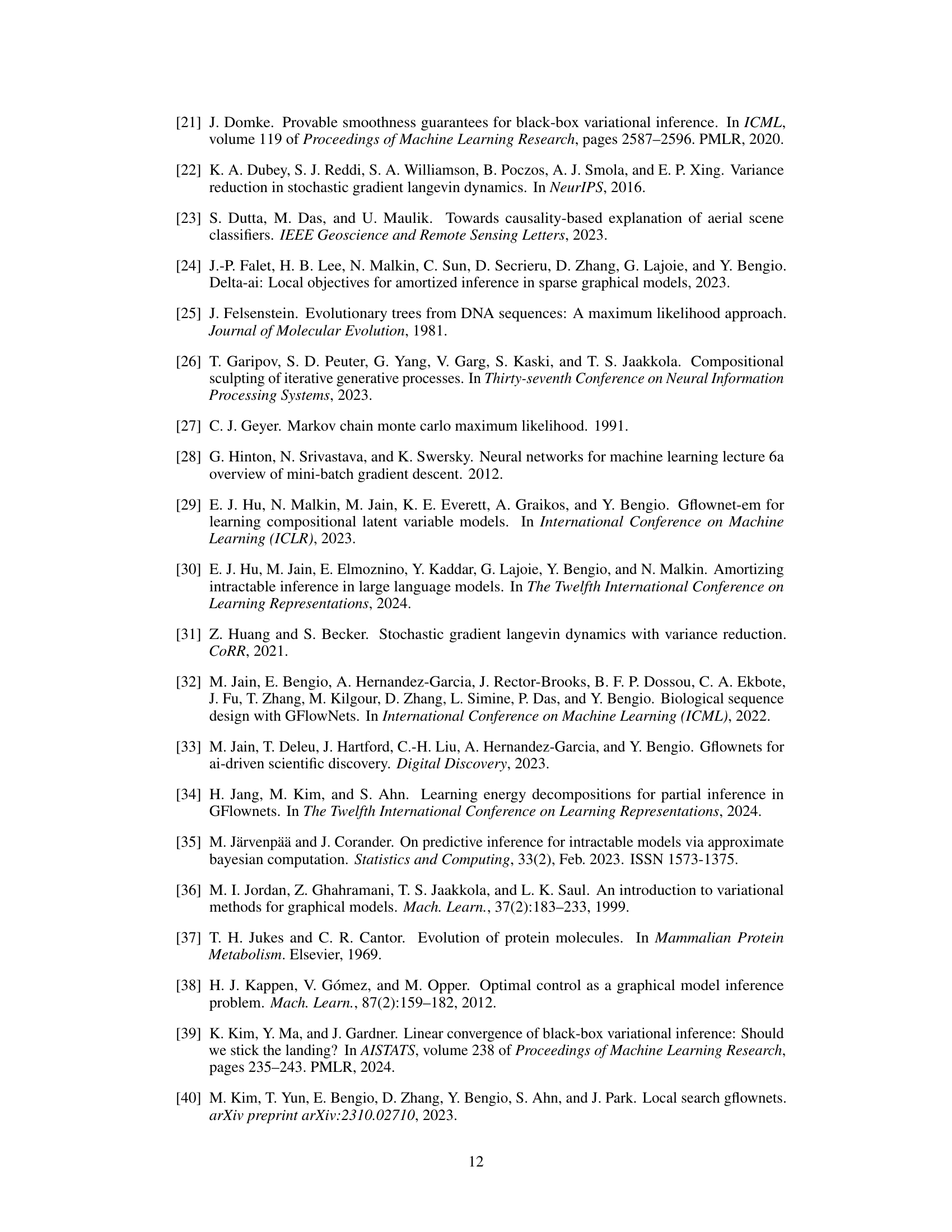

🔼 This figure compares the learning curves for different divergence measures (forward KL, reverse KL, Renyi-a, Tsallis-a) with and without control variates (CVs) in the set generation task. It demonstrates that using CVs significantly reduces the variance of gradient estimates, leading to more stable and faster training convergence for all divergence measures.

read the caption

Figure 6: Learning curves for different objective functions in the task of set generation. The reduced variance of the gradient estimates notably increases training stability and speed.

🔼 This figure compares the convergence speed of different divergence-based learning objectives against the trajectory balance (TB) loss for training GFlowNets. The results show that while there’s no single best objective, divergence-based methods generally converge faster or comparably to TB loss across various generative tasks. The average results over multiple runs are plotted for each objective and task.

read the caption

Figure 3: Divergence-based learning objectives often lead to faster training than TB loss. Notably, contrasting with the experiments of [56], there is no single best loss function always conducting to the fastest convergence rate, and minimizing well-known divergence measures is often on par with or better than minimizing the TB loss in terms of convergence speed. Results were averaged across three different seeds. Also, we fix a = 0.5 for both Tsallis-a and Renyi-a divergences.

🔼 This figure illustrates how the choice of the α parameter in Renyi-α and Tsallis-α divergences affects the learning dynamics of GFlowNets. The figure shows heatmaps representing learned distributions for different α values (-2, -1, 0.5, 2) alongside the target distribution. A large negative α causes the model to broadly cover the target distribution’s mass, while a large positive α results in the model focusing on a single high-probability mode. An intermediate value (α=0.5) provides the most accurate approximation of the target.

read the caption

Figure 1: Mode-seeking (α = 2) versus mass-covering (α = -2) behaviour in α-divergences.

🔼 This figure compares the training speed of GFlowNets using different loss functions: reverse KL divergence, KL divergence, Renyi-α divergence, Tsallis-α divergence, trajectory balance (TB) loss, and detailed balance (DB) loss. The results show that divergence-based losses often lead to faster convergence than TB loss, although there’s no single best loss function for all tasks. The results were averaged across multiple trials to account for variability.

read the caption

Figure 3: Divergence-based learning objectives often lead to faster training than TB loss. Notably, contrasting with the experiments of [56], there is no single best loss function always conducting to the fastest convergence rate, and minimizing well-known divergence measures is often on par with or better than minimizing the TB loss in terms of convergence speed. Results were averaged across three different seeds. Also, we fix α = 0.5 for both Tsallis-α and Renyi-α divergences.

Full paper#