↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Multi-label active learning (MLAL) faces challenges with large, sparse label spaces and limited labeling resources. Existing methods struggle to efficiently capture label correlations and quantify uncertainty, hindering the effectiveness of active learning. This often leads to suboptimal selection of data points for labeling, wasting valuable resources.

The paper introduces Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM), which uses a mixture of Bernoulli models to efficiently represent the label space and combines this with evidential learning to predict weight coefficients. This innovative approach provides fine-grained uncertainty information, allowing for better active sample selection. EMM incorporates a novel multi-source uncertainty metric which considers both predicted label embedding covariances and evidential uncertainty, leading to improved performance. Experimental results demonstrate that EMM outperforms existing MLAL methods on both synthetic and real-world datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multi-label active learning due to its novel approach of using evidential learning to improve prediction accuracy and uncertainty quantification, particularly in scenarios with large and sparse label spaces. It opens doors for more effective and efficient handling of data, especially in applications with limited labeling resources, such as healthcare and environmental science. The proposed model, EMM, provides a significant advancement over existing methods, offering opportunities for further investigation into uncertainty-aware model building and advanced data sampling techniques.

Visual Insights#

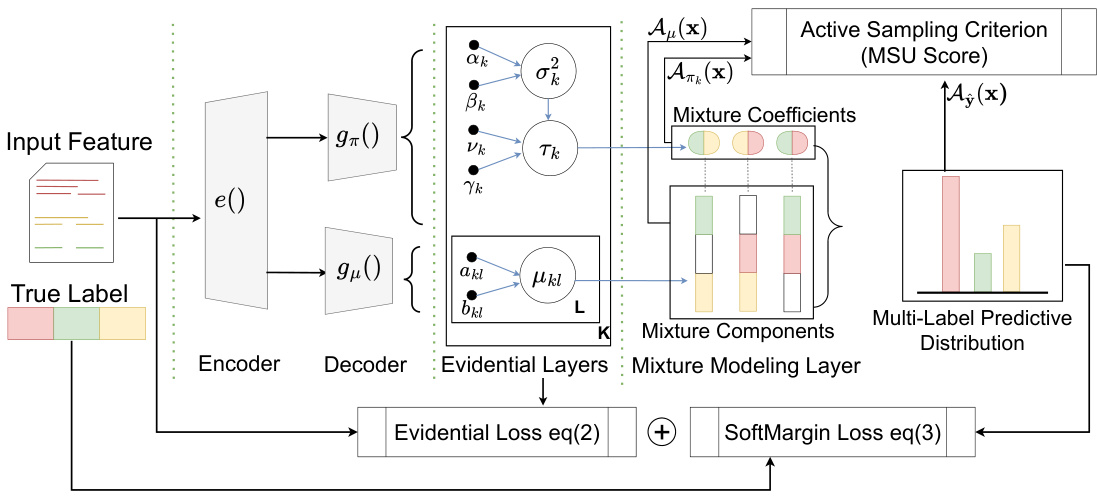

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM) model proposed in the paper. The model consists of an encoder that processes input features, and two decoders that predict mixture coefficients and mixture components, respectively. The mixture coefficients are predicted using an evidential regression model, which provides uncertainty information. The mixture components model the correlations between labels. The model combines evidential uncertainty with predicted label embedding covariances for active sample selection. The entire model is trained by minimizing an evidential loss and a soft margin loss.

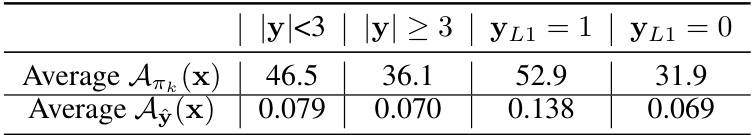

This table presents a statistical analysis of the relationship between three key aspects of the data: average uncertainty scores (from the weight coefficient and label prediction branches of the EMM model), label cardinality (the number of labels associated with each data instance), and the presence of rare labels (specifically, label L1). It quantifies how these factors correlate with each other. For instance, it shows that data instances with a lower number of labels tend to have higher average uncertainty scores, and those containing rare labels also have significantly higher uncertainty scores.

In-depth insights#

EMM: Core Idea#

The core idea behind Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM) is to effectively model multi-label correlations within a large and often sparse label space, particularly crucial for active learning scenarios with limited labeling resources. Unlike traditional methods that treat labels independently, EMM leverages mixture components derived from unsupervised learning to capture inherent relationships between labels. Evidential learning is then applied to predict the weight coefficients of these components, providing an uncertainty-aware mechanism that significantly improves prediction accuracy. This uncertainty is further enhanced by combining it with the predicted label embedding covariances, leading to a more informative uncertainty metric for active sample selection. The key is the ability to capture both global label clusters and instance-specific adjustments, resulting in more reliable predictions, particularly for infrequent labels. This framework allows EMM to significantly outperform existing multi-label active learning methods.

Synthetic Data#

Synthetic data generation is crucial for evaluating the proposed Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM) model, especially in the context of multi-label active learning. The paper uses synthetic data to demonstrate EMM’s ability to capture complex label correlations and its effectiveness in handling scenarios with rare labels. By controlling the underlying data generation process, researchers can create datasets with specific characteristics, allowing for a more targeted evaluation of EMM’s performance. The use of synthetic data allows for a rigorous assessment of EMM’s strengths and weaknesses in various settings, and helps understand how well the model can generalize to real-world datasets. Furthermore, synthetic datasets aid in evaluating the model’s uncertainty quantification mechanisms, a key aspect of active learning, which is critical to ensure informative sample selection. Overall, the careful design and utilization of synthetic datasets contributes significantly to the paper’s validation of EMM as a robust multi-label active learning approach.

Real-World Tests#

A dedicated ‘Real-World Tests’ section would significantly strengthen this research paper. It should present results on diverse, publicly available multi-label datasets, going beyond the synthetic data used for initial validation. Benchmarking against existing state-of-the-art multi-label active learning methods is crucial, showing a clear improvement in metrics like AUC and average precision. The analysis should consider the impact of label scarcity and imbalanced class distributions, key challenges in real-world scenarios. Specific attention to performance on rare labels is vital, as the paper emphasizes the handling of these. A detailed breakdown of performance across different datasets, highlighting strengths and weaknesses, would offer valuable insights. Finally, an in-depth discussion on practical implications and limitations, considering computational cost and data requirements for different scales of real-world problems, is essential for assessing the actual applicability and broader impact of the proposed EMM model.

Uncertainty Metrics#

The concept of “Uncertainty Metrics” in the context of multi-label active learning is crucial for effective sample selection. A well-designed metric should quantify the model’s uncertainty about its predictions, guiding the selection of the most informative samples for labeling. This involves not just considering the overall uncertainty, but also potentially decomposing it into aleatoric (data-inherent) and epistemic (knowledge-based) components. An effective approach might incorporate the predicted label covariances to capture the relationships among labels. Evidential learning, as exemplified by the use of Normal Inverse Gamma (NIG) distributions, offers a principled way to obtain fine-grained uncertainty estimates. The integration of multiple uncertainty sources (weight coefficients, proxy pseudo counts, final label predictions) into a unified metric, like the proposed Multi-Source Uncertainty score, allows for a more comprehensive assessment of information gain, leading to improved active learning performance.

Future Work#

The authors mention several promising avenues for future research. Extending the model to handle extremely large datasets and real-time applications is crucial, as the current model’s complexity may limit scalability. Developing a more adaptive model with a dynamic number of clusters (K) would improve flexibility and efficiency. Investigating more lightweight training and adaptation processes is needed to address computational cost. Additionally, exploring alternative active learning strategies and uncertainty quantification methods is a priority. Integrating AUC-based loss regularization into the training would also be a valuable enhancement. Finally, applying EMM to various domains beyond those studied in this paper will showcase its broad applicability and effectiveness.

More visual insights#

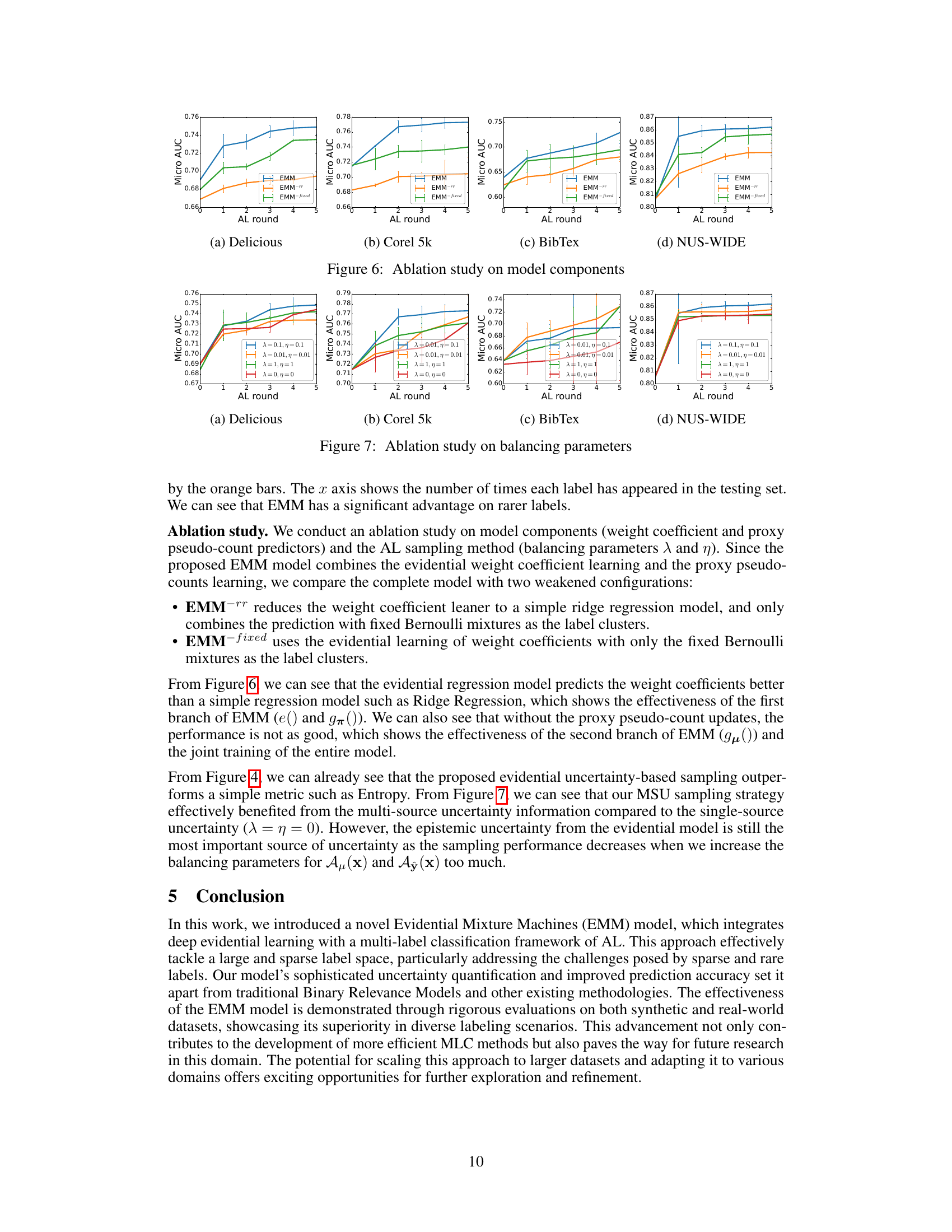

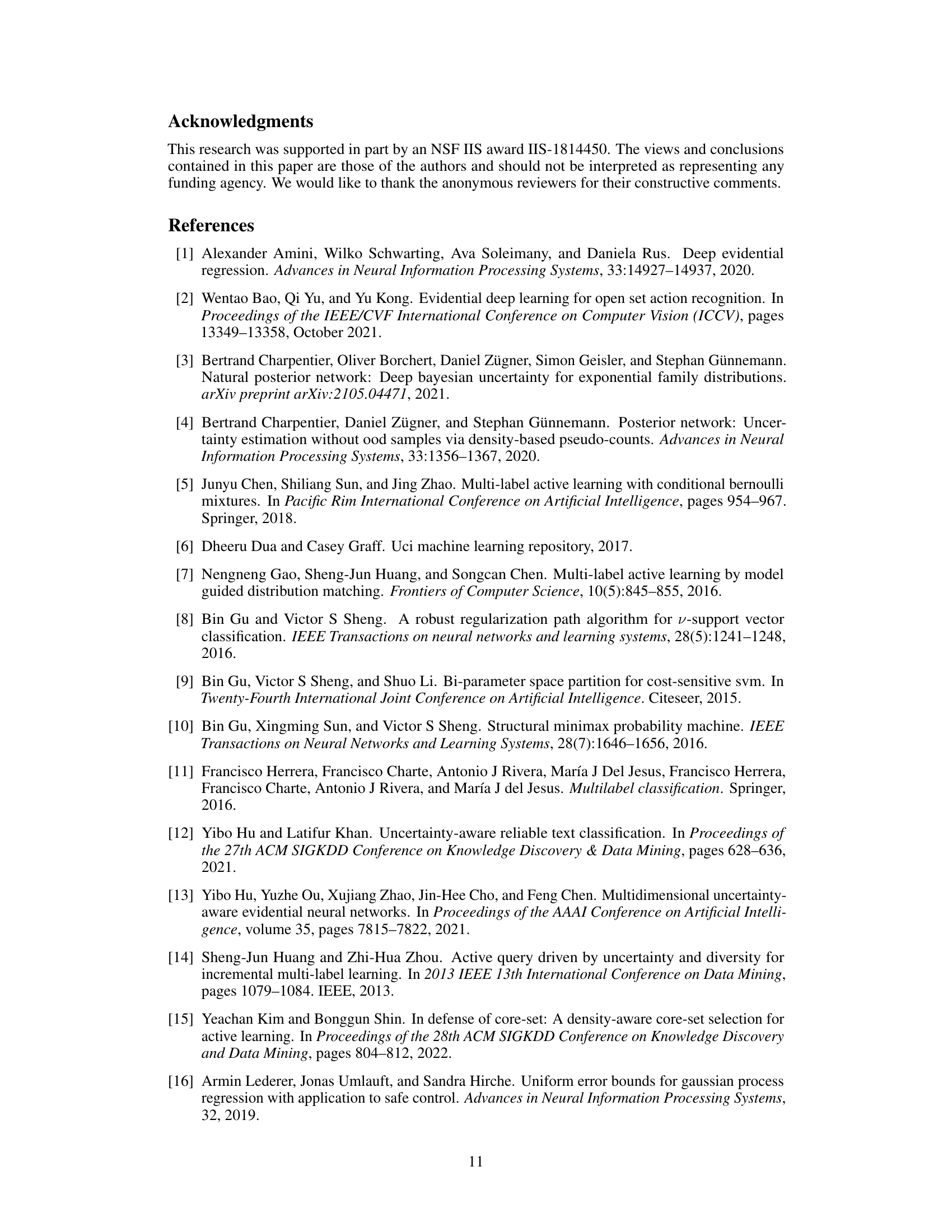

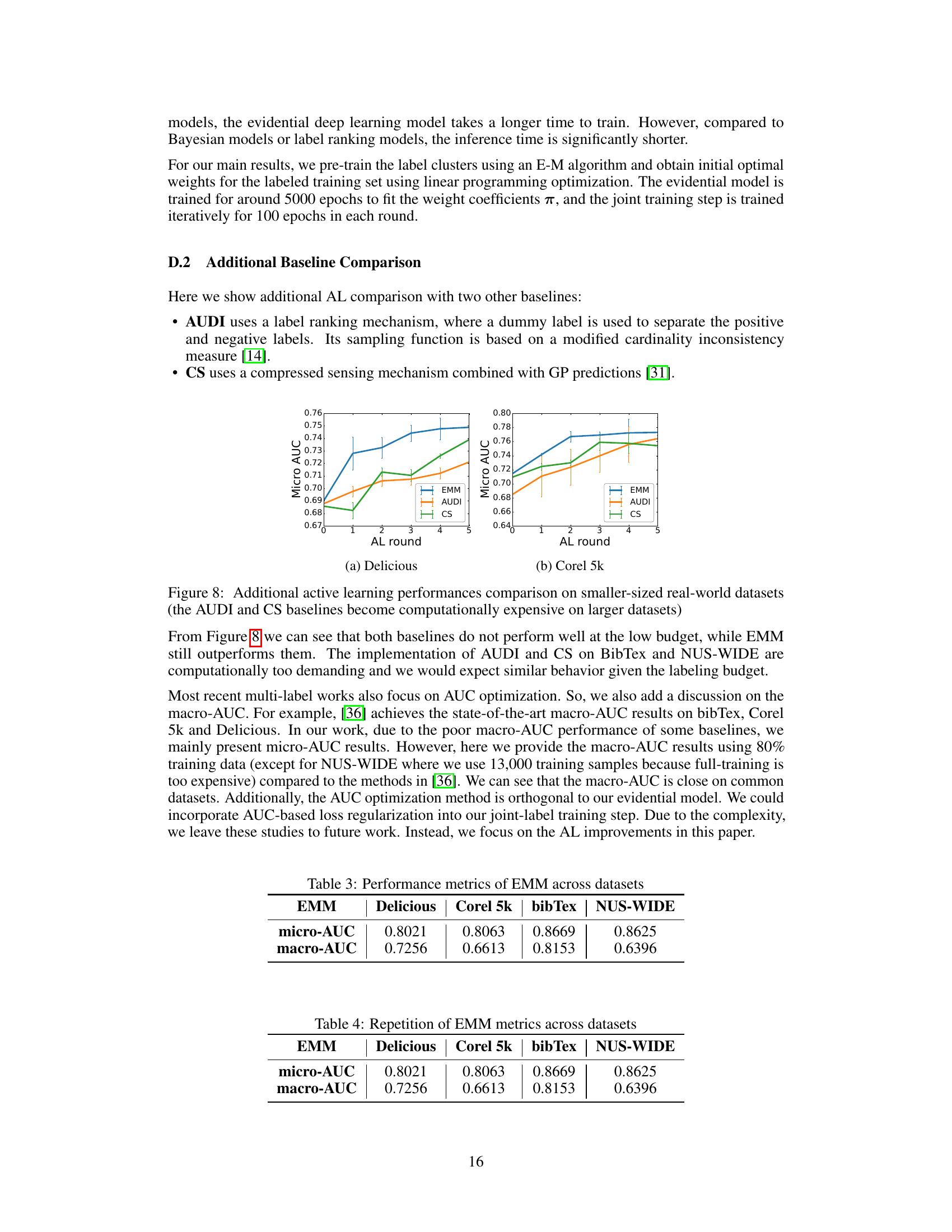

More on figures

This figure visualizes the composition of labels in a synthetic dataset used for experiments. The dataset features input data points clustered in a high-dimensional feature space, represented here in a simplified 2D view. The labels are categorized into geometric-based labels (reflecting cluster membership), non-geometric labels (independent of cluster structure), and labels of interest. The labels of interest include a rare label (L1, present in only 5% of samples), highly correlated labels (L2 and L3, sharing similar features and often co-occurring), and a label (L4) derived from the logical combination of L2 and L3 (L4 = L2 ∪ L3). This controlled dataset allows for testing of the EMM model’s ability to capture correlations between different types of labels.

This figure visualizes the label clusters learned by the EMM model. Subfigure (a) shows clusters related to labels L2, L3, and L4, highlighting their correlations. Subfigure (b) focuses on label L1 (a rare label), comparing the original cluster with updated clusters after incorporating proxy pseudo-counts. The ‘updated’ cluster demonstrates the model’s adaptation to new data, while the ‘irrelevant’ cluster shows how the model adjusts when a cluster is less relevant to a specific data point.

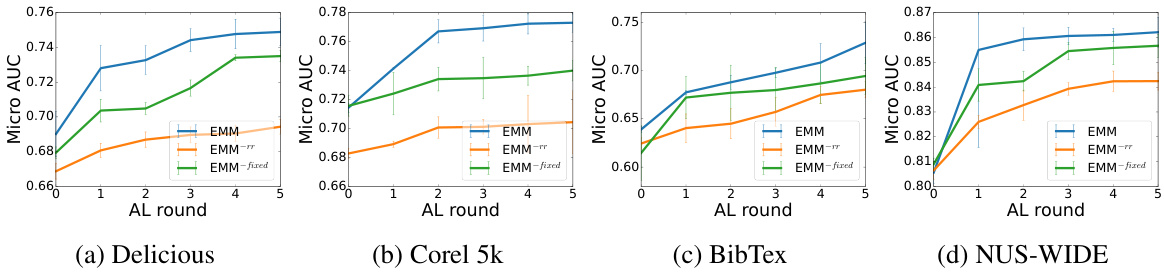

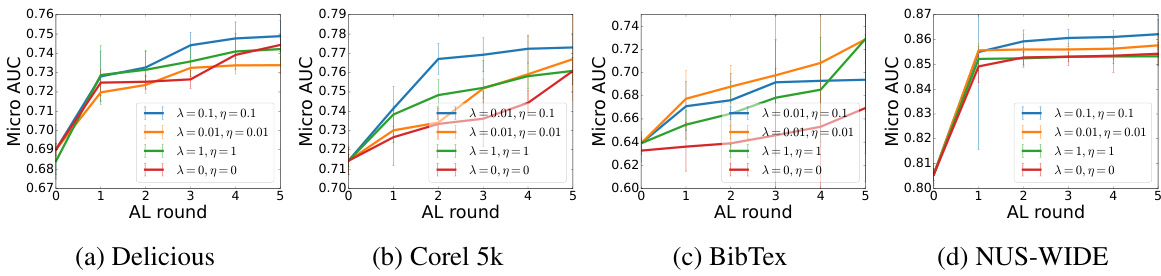

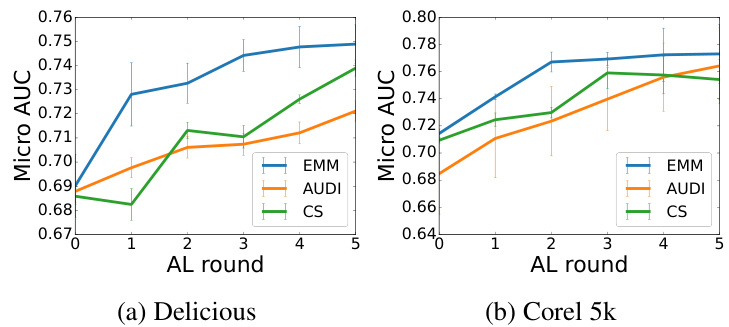

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on four real-world multi-label datasets (Delicious, Corel 5k, BibTex, and NUS-WIDE) to evaluate the performance of the proposed Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM) model against several baseline methods in an active learning setting. The x-axis represents the active learning rounds (5 rounds with 100 samples added in each round), and the y-axis displays the micro-AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve), a common metric for evaluating multi-label classification performance. Each line in the graph represents a different method: EMM (the proposed model), GP-B2M, MMC, Adaptive, CVIRS, and EMM-entropy (a variant of EMM using a simple entropy-based sampling strategy). The results show how the AU-ROC of each model improves over the 5 rounds of active learning, indicating the effectiveness of active learning and the comparative performance of the EMM model. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the results across multiple runs.

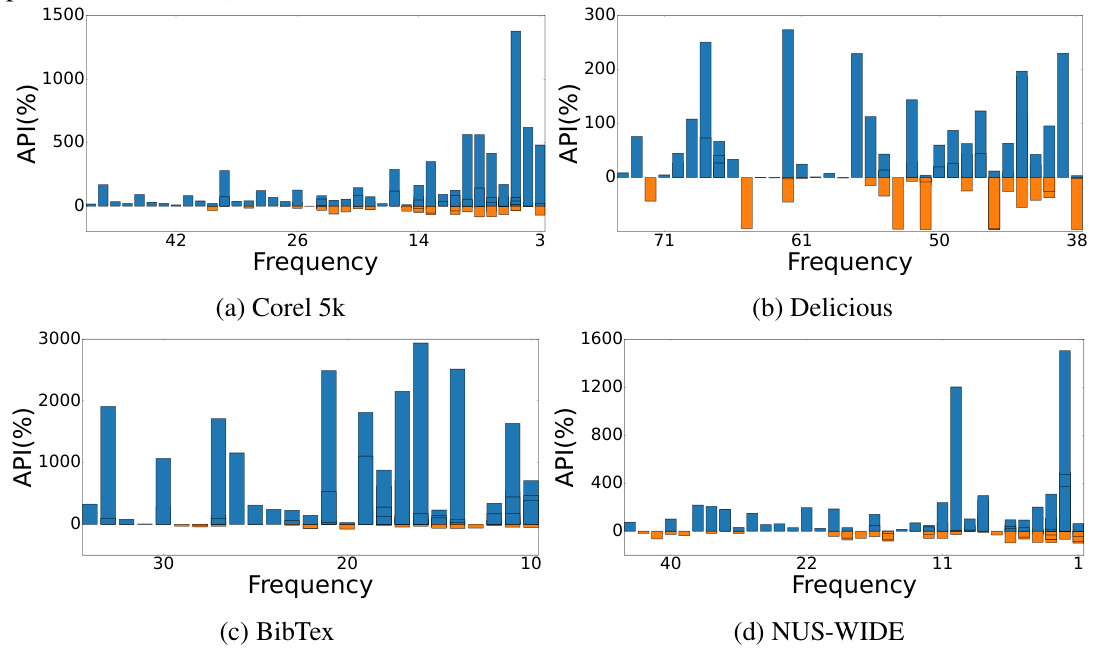

This figure shows the average precision improvement (API) for the 50 rarest labels in four real-world multi-label datasets: Corel5k, Delicious, BibTex, and NUS-WIDE. The x-axis represents the frequency of each label, and the y-axis shows the API, which is calculated as the percentage increase in average precision for the rare labels using the proposed EMM model compared to a baseline GP-B2M model. Positive API values indicate improvement by EMM, while negative values indicate worse performance. The bars represent the API for each label, with error bars showing variability. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of EMM in improving the prediction of rare labels across different datasets, particularly those with lower frequencies.

This figure displays the performance comparison of EMM against other state-of-the-art multi-label active learning methods (GP-B2M, MMC, Adaptive, CVIRS) on four real-world datasets: Delicious, Corel5k, Bibtex, and NUS-WIDE. The x-axis represents the number of AL rounds (5 rounds total, with 100 samples added per round). The y-axis shows the micro-averaged AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve), a common metric for evaluating the performance of multi-label classifiers. Each line represents a different algorithm, showing its AUC performance as more labeled samples are added via the active learning process. The results demonstrate EMM’s improved performance compared to the baselines across various datasets.

This figure displays the performance of the EMM model and several baseline methods across four real-world multi-label datasets: Delicious, Corel 5k, BibTex, and NUS-WIDE. The y-axis represents the AU-ROC score, a measure of the model’s performance. The x-axis indicates the number of active learning rounds, with 100 samples added in each round. The lines represent different models: EMM, GP-B2M, MMC, Adaptive, CVIRS, and EMM-entropy (EMM using entropy-based sampling). The results show that EMM consistently outperforms the other methods across all four datasets. The error bars indicate standard deviation, suggesting the statistical significance of the findings.

This figure presents the results of the active learning experiments on four real-world multi-label datasets (Delicious, Corel 5k, BibTex, and NUS-WIDE). The AU-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) is plotted for each dataset across five rounds of active learning, with 100 samples selected in each round. The graph shows the performance of the proposed EMM model compared to several baselines (GP-B2M, MMC, Adaptive, CVIRS, EMM-entropy). The AU-ROC is used as a performance measure, showing how well the model classifies instances after each round of additional label acquisition. Higher values indicate better performance. The EMM model consistently performs competitively with or better than the other methods.

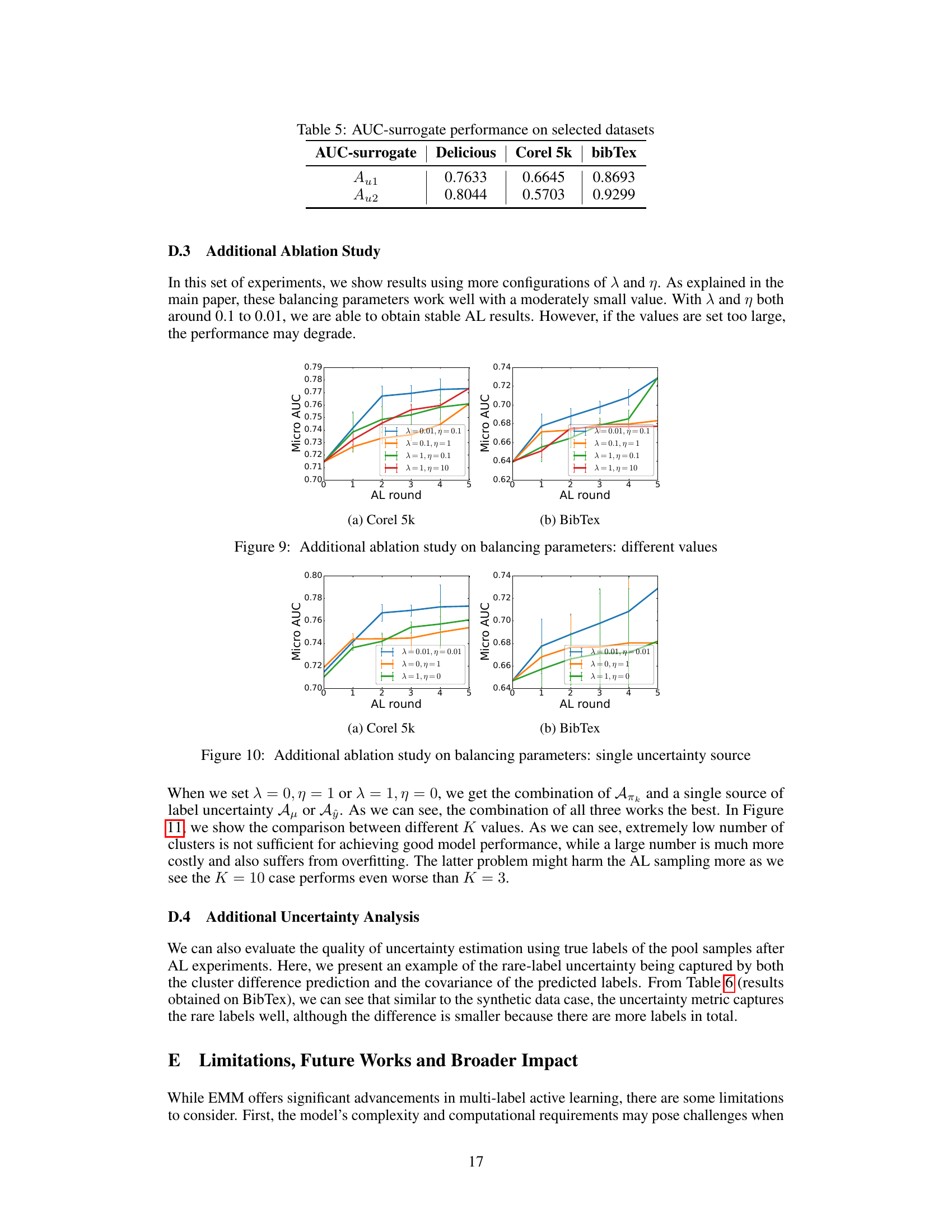

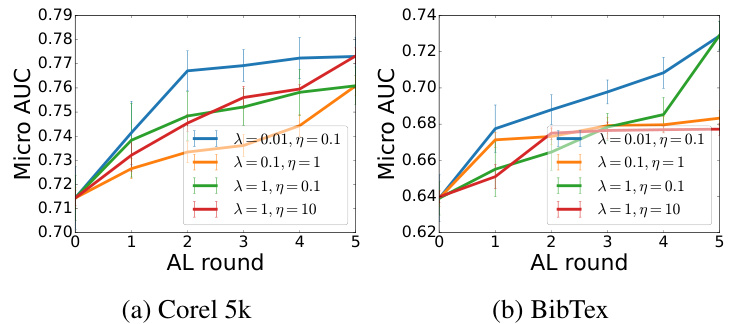

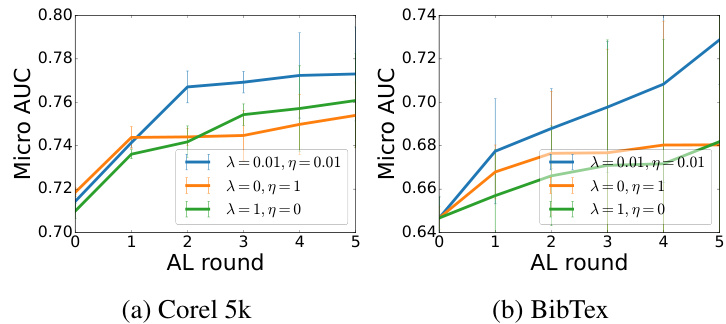

This figure presents ablation studies on the balancing parameters (λ and η) used in the multi-source uncertainty-based sample selection strategy. Different combinations of λ and η are tested to determine their impact on the active learning performance. λ weights the uncertainty from the weight coefficient predictor, and η weights the uncertainty from the label prediction and proxy pseudo-count predictor. The results, presented as micro-AUC across several active learning rounds, illustrate how the choice of these parameters influences the overall active learning performance. The graph shows that a balance needs to be struck; excessively high values of λ and η lead to a drop in performance.

This figure displays the results of an ablation study on the balancing parameters (λ and η) used in the active learning strategy of the EMM model. It shows the micro-AUC scores across multiple rounds of active learning for two datasets (Corel 5k and BibTex). Different lines represent different combinations of λ and η values, demonstrating how the choice of these parameters impacts the model’s performance.

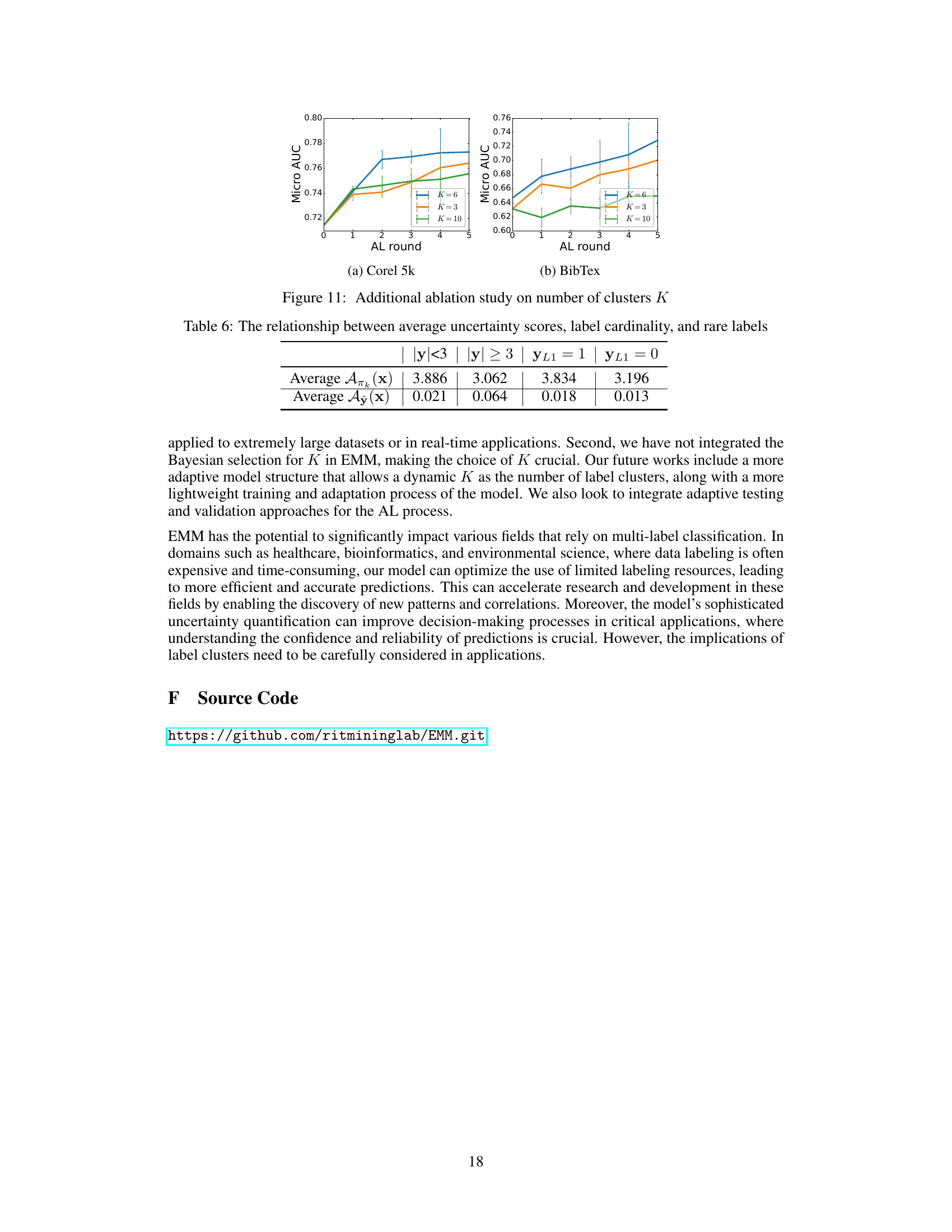

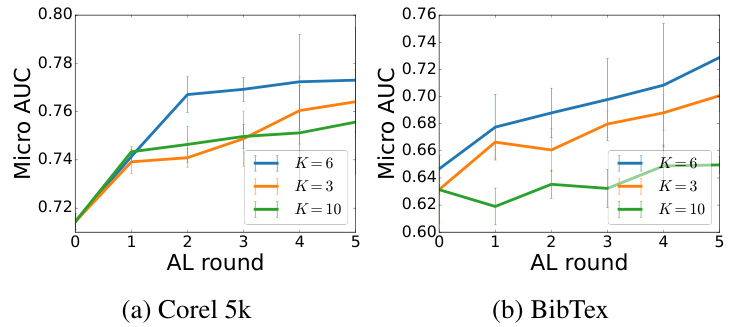

This figure displays the results of an ablation study on the impact of varying the number of clusters (K) in the EMM model. The micro-AUC metric is plotted against the number of active learning rounds for different values of K (3, 6, and 10). The plots show the performance on the Corel 5k and BibTex datasets, illustrating how the choice of K affects the model’s performance in active learning scenarios. Error bars are included to indicate variability.

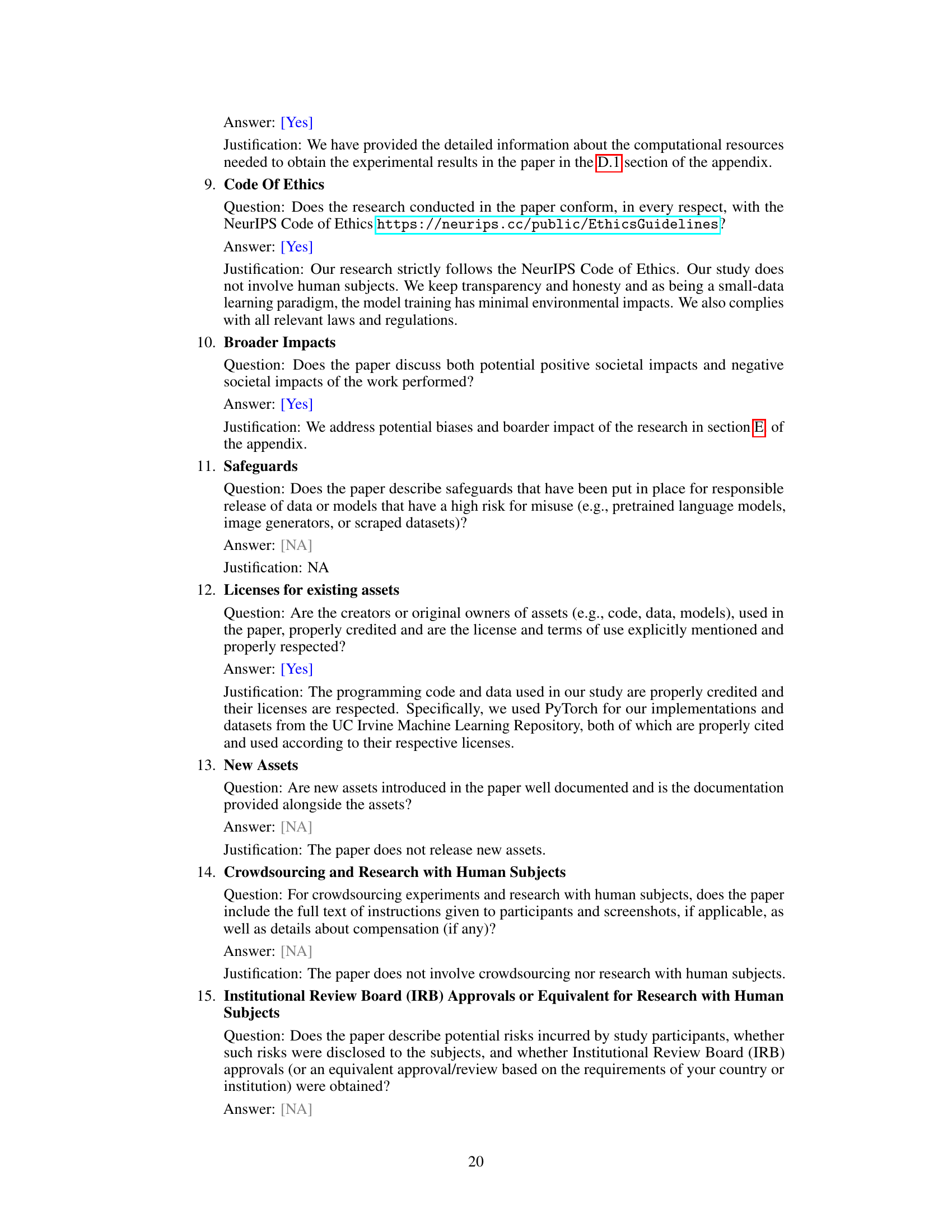

More on tables

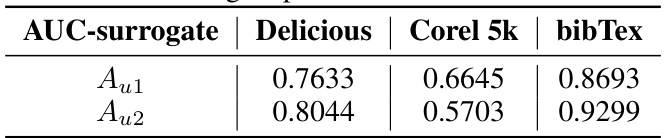

This table presents a statistical analysis of the correlation between three key aspects of the data samples: average uncertainty scores (Απκ(x) and Aŷ(x)), label cardinality (number of labels assigned to a sample), and the presence of rare labels (YL1 = 1 indicating the presence of a rare label, and YL1 = 0 indicating its absence). The table shows the average uncertainty scores for different combinations of label cardinality and the presence/absence of rare labels, providing insights into how these factors influence uncertainty estimations. This analysis helps to understand the model’s behavior with respect to rare labels and how effectively it captures uncertainty in various scenarios.

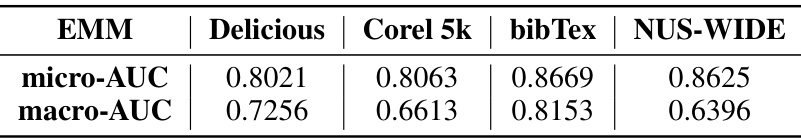

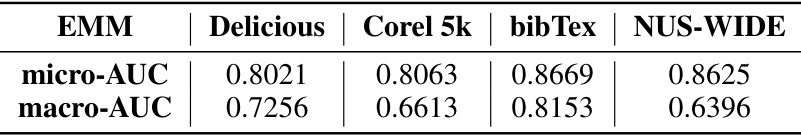

This table presents the performance of the Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM) model on four real-world multi-label datasets: Delicious, Corel5k, BibTex, and NUS-WIDE. The performance is measured using two metrics: micro-AUC and macro-AUC. Micro-AUC calculates the average AUC across all labels, while macro-AUC calculates the average AUC for each label and then averages these values. Higher values indicate better performance. The table summarizes the model’s performance on each dataset, showcasing its ability to achieve high accuracy and handle diverse, complex label spaces.

This table presents the micro-AUC and macro-AUC scores achieved by the Evidential Mixture Machines (EMM) model on four real-world multi-label datasets: Delicious, Corel5k, BibTex, and NUS-WIDE. Micro-AUC and macro-AUC are common evaluation metrics for multi-label classification, measuring the model’s overall performance across all labels. The results show the performance of EMM on each dataset, allowing for a comparison of its effectiveness across different data characteristics and label distributions.

This table shows the correlation between the average uncertainty scores (Απκ (x) and Aŷ (x)), label cardinality (number of labels per instance), and the presence of rare labels (YL1=1 or YL1=0). It helps analyze how the uncertainty scores relate to the number of labels in an instance and whether a rare label is present, providing insights into the model’s behavior for different data characteristics. Higher average uncertainty scores are observed for samples with fewer labels and those containing rare labels.

This table shows the correlation between three uncertainty metrics (average Απκ (x), average Aŷ (x)), the number of labels in a sample (label cardinality), and the presence of rare labels. It helps to understand how uncertainty is related to the characteristics of samples, particularly regarding the presence of rare labels.

Full paper#