↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep neural networks are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, where imperceptible changes in input data can drastically alter model predictions. Existing approaches to mitigate this vulnerability using vision-language models often suffer from high adaptation costs, suboptimal text supervision, and poor generalization. These issues are particularly pronounced in low-data scenarios like few-shot learning.

This research introduces a novel Few-shot Adversarial Prompt learning (FAP) framework that addresses these limitations. FAP learns adversarially correlated text supervision directly from adversarial examples and uses a new training objective to enhance the consistency of multi-modal features while improving uni-modal distinction. This strategy achieves state-of-the-art zero-shot adversarial robustness with only 1% of training data, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed approach for enhancing the robustness of vision-language models in real-world applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the significant challenge of improving the adversarial robustness of vision-language models using limited data. It introduces a novel few-shot adversarial prompt learning framework, addressing current limitations of heavy adaptation costs and suboptimal supervision. This directly impacts the development of more reliable and secure AI systems in various applications. The proposed method’s superior performance opens exciting new avenues for improving the robustness and generalization capabilities of VLMs and related techniques.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Few-shot Adversarial Prompt Learning (FAP) framework. It highlights that only the prompt tokens and deep projections from image to text are trained, while the rest of the pre-trained CLIP model remains frozen. The framework aims to achieve consistent cross-modal similarity between natural and adversarial examples while also encouraging differences in their unimodal representations. This approach uses adversarially correlated text supervision learned from a small number of adversarial examples to improve the alignment of adversarial features and create robust decision boundaries.

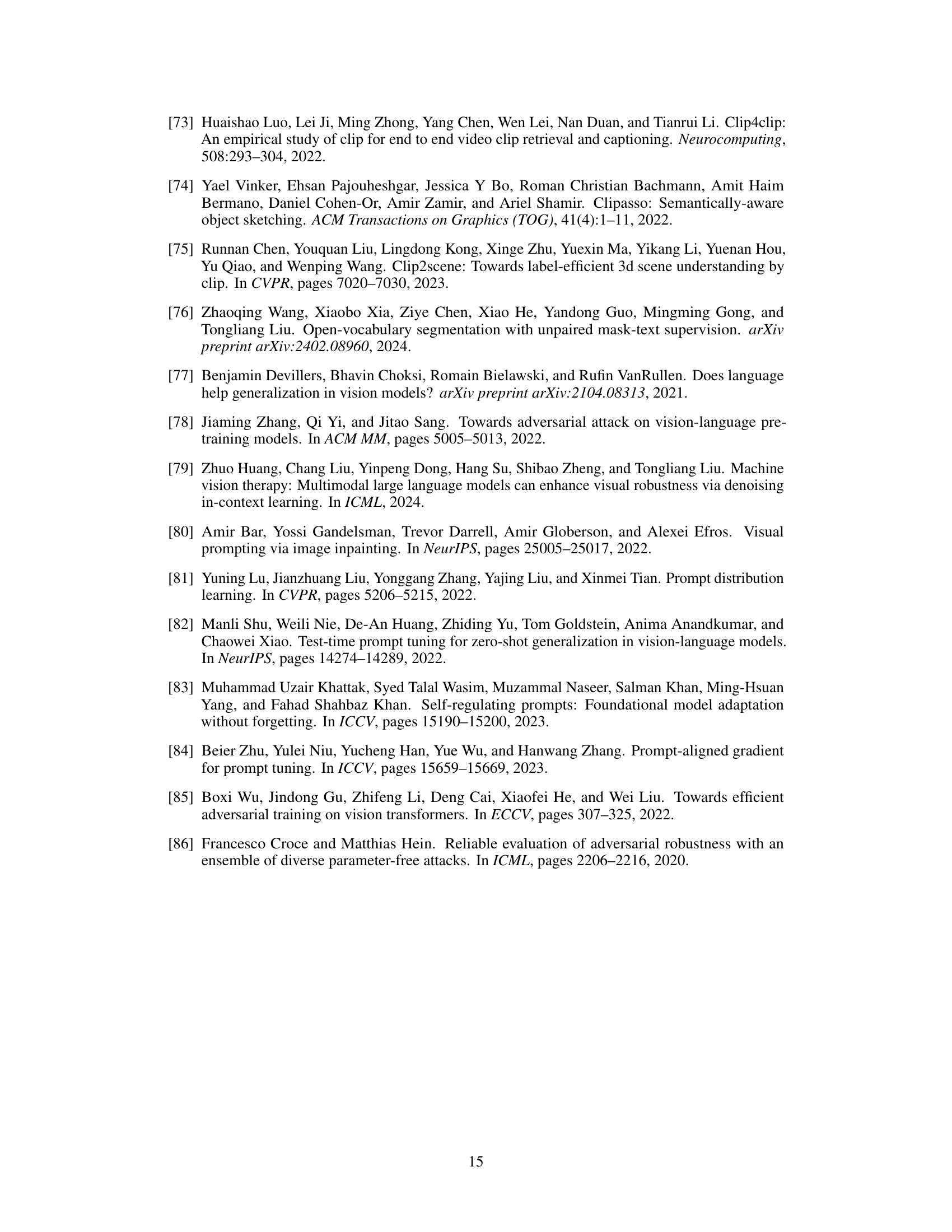

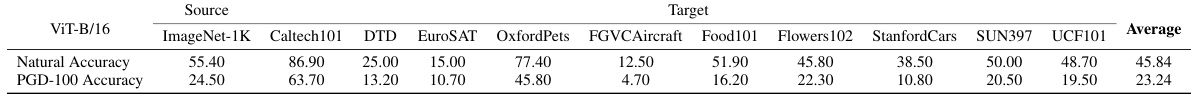

This table presents the results of an adversarial base-to-new generalization experiment. The experiment evaluates the model’s ability to generalize from a limited set of base classes to new, unseen classes, both under normal and adversarial conditions. The table shows the average natural accuracy and adversarial accuracy (using PGD-100 attacks) across 11 different datasets, with separate results for base and new classes. These results help illustrate how well the model generalizes to new data and its robustness to adversarial attacks. Appendix D.10 provides more detailed, dataset-specific results.

In-depth insights#

Adversarial Prompt#

The concept of “Adversarial Prompt” in the context of vision-language models involves crafting prompts specifically designed to probe the robustness of the model against adversarial attacks. Instead of relying on standard, benign prompts, adversarial prompts incorporate subtle perturbations or manipulations aimed at misleading the model’s interpretation. This could involve using semantically similar but visually different images or text, or employing adversarial examples generated using techniques like fast gradient sign method. The effectiveness of an adversarial prompt depends on the ability to create a carefully constructed input that exploits vulnerabilities in the model’s multi-modal understanding. By analyzing how the model responds to adversarial prompts, researchers can gain valuable insights into the model’s limitations and identify areas needing improvement for increased robustness and reliable performance in real-world scenarios. The goal is to evaluate and strengthen the model’s resilience against malicious manipulations and subtle distortions in input data, thereby improving the security and trustworthiness of the overall system.

Few-Shot Learning#

Few-shot learning, a subfield of machine learning, tackles the challenge of training accurate models with minimal data. This is particularly useful when obtaining large labeled datasets is expensive or infeasible. The core idea revolves around enabling models to generalize well from just a few examples per class. The paper focuses on applying few-shot learning in the context of adversarial robustness, a critical area where traditional methods often falter due to data scarcity. By adapting pre-trained vision-language models with limited adversarial examples, the authors create a framework that significantly improves robustness. This approach cleverly leverages the power of large pre-trained models while keeping adaptation costs low. The method is especially pertinent to real-world applications where massive datasets are not always available. A key contribution is the introduction of learnable prompts, dynamically adjusting the model’s input to adapt to adversarial examples instead of relying on fixed templates. The training objective is carefully designed to balance natural and adversarial generalization, avoiding the problem of over-adaptation to adversarial examples at the cost of losing performance on clean data. This ensures a practical system that performs well in both benign and adversarial settings.

CLIP Adaptation#

CLIP Adaptation methods in adversarial robustness research aim to leverage the power of pre-trained vision-language models (VLMs) like CLIP for improved security against adversarial attacks. A key challenge is aligning adversarial examples’ visual features with text descriptions, which is crucial for the model to effectively recognize these perturbed inputs. Zero-shot adaptation, while attractive for its efficiency, often struggles due to suboptimal text supervision and the high cost of adapting on very large datasets. Few-shot techniques are emerging as a more practical solution, requiring significantly less data to achieve comparable results. Learnable prompts are a particularly interesting area of research, providing greater flexibility in adapting the input representations to adversarial examples. An effective adaptation strategy is to use adversarially correlated text supervision, learned end-to-end from adversarial examples, enabling superior cross-modal alignment. Finally, it is vital to address the issue of balancing natural generalization with adversarial robustness during adaptation, as methods solely focused on adversarial examples may sacrifice performance on clean data.

Generalization Limits#

Generalization, the ability of a model to perform well on unseen data, is a critical aspect of machine learning. Limited generalization severely restricts the applicability of a model, especially in adversarial settings where the model’s robustness to unseen attacks is paramount. Several factors can contribute to poor generalization in adversarial machine learning, including the distribution shift between training and test data, the complexity of the model, and the nature of the adversarial attacks themselves. Insufficient training data is a major limitation for learning robust representations that generalize well. Methods that rely heavily on large-scale datasets to establish zero-shot adversarial robustness may not generalize well to different tasks or datasets. The lack of diversity in training examples can limit the model’s ability to adapt to various adversarial perturbations. Moreover, hand-crafted adversarial examples might not cover the full spectrum of possible attacks, leading to poor generalization. Therefore, approaches that learn to generate or adapt to adversarially correlated information with limited data are crucial to overcome these limitations and achieve robust generalization.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of adversarial prompt learning is crucial, especially for resource-constrained settings. This might involve developing more efficient algorithms or leveraging techniques like quantization or pruning to reduce the model’s size and computational cost. Another key area is enhancing the robustness of adversarial prompt learning to different attack strategies. The current work focuses on PGD attacks; exploring defense mechanisms against more sophisticated attacks, like AutoAttack, is essential. Furthermore, investigating the generalization capabilities across diverse datasets and tasks is critical to ensure practical applicability. This includes testing on a wider range of downstream tasks and datasets to validate the method’s robustness. Finally, deeper theoretical understanding of why and how adversarial prompt learning works is needed. This could lead to more effective designs and guide the development of more robust and efficient methods in the future.

More visual insights#

More on figures

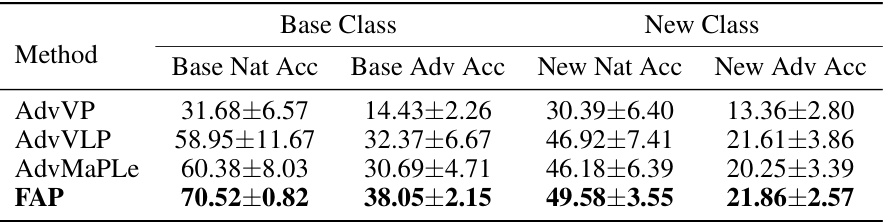

This figure visualizes the impact of the proposed adversarial-aware mechanism on the model’s feature learning. The left subplot (a) shows the uni-modal embeddings learned without the adversarial-aware term, where adversarial embeddings closely resemble natural examples, indicating a lack of distinction between them. The right subplot (b) shows the uni-modal embeddings learned with the adversarial-aware term. Here, the adversarial embeddings are clearly separated from the natural embeddings, demonstrating that the adversarial-aware mechanism successfully distinguishes between natural and adversarial features.

This figure visualizes the effects of the proposed adversarial-aware mechanism on the model’s feature learning. It compares uni-modal embeddings (visual features only) learned with and without the mechanism. The left panel (a) shows that without the mechanism, some adversarial embeddings are very close to natural examples, suggesting the model is taking a shortcut and not truly learning robust features. The right panel (b) shows that with the mechanism, adversarial and natural examples are clearly separated in the visual feature space, indicating more effective adversarial robustness learning. This is because the mechanism encourages the model to distinguish between adversarial and natural features, preventing the shortcut observed in (a).

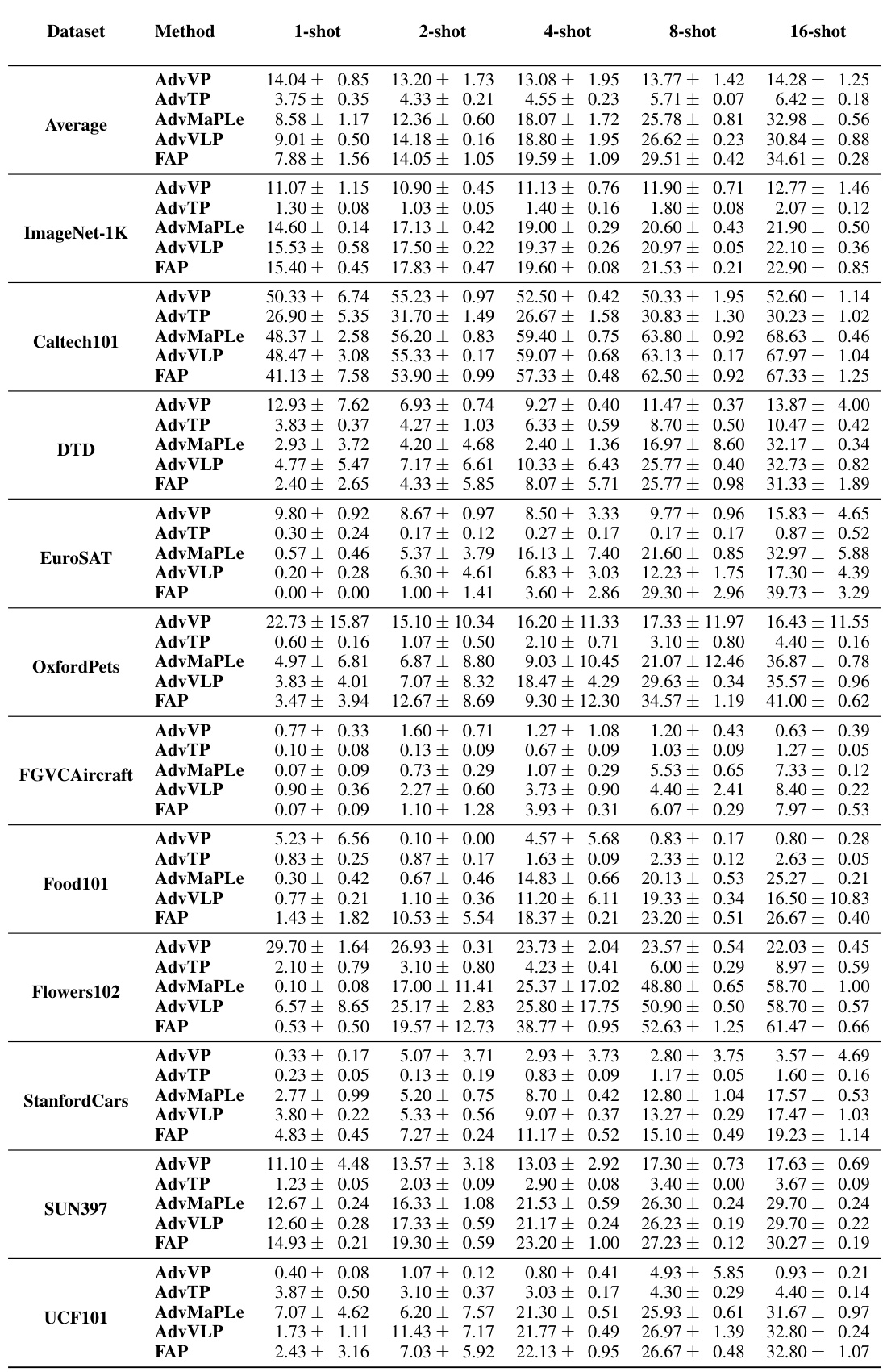

This figure visualizes the performance of adversarial few-shot learning across 11 different datasets. It compares the natural accuracy (without adversarial attacks) and robust accuracy (with adversarial attacks) across varying numbers of training examples (shots per class). The results, averaged across three trials, illustrate the impact of the number of training examples on both natural and robust generalization.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed Few-shot Adversarial Prompt Learning (FAP) framework. It highlights that only the prompt tokens and the image-to-text projections are tuned during training, while the rest of the pre-trained model remains frozen. The framework aims to create a consistent cross-modal similarity between natural and adversarial examples, while simultaneously emphasizing differences in the uni-modal features. This approach allows for better alignment of adversarial features and the creation of robust decision boundaries, even with a limited amount of training data.

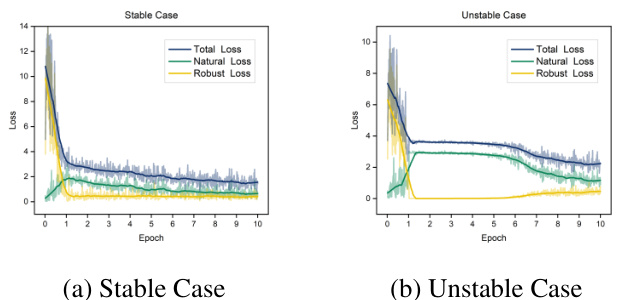

This figure visualizes the potential failure modes of adversarial prompt learning and proposes a solution. The left panel (a) shows training loss curves for two scenarios: a ‘stable case’ where the loss decreases steadily, and an ‘unstable case’ where the robust loss plateaus early. The right panel (b) provides an overview of the failure cases’ characteristics; they are caused by the model’s inability to achieve natural generalization due to its reliance on adversarial examples. To remedy this, the authors propose supplementing adversarial examples with natural examples in the training process. This effectively mitigates the unstable conditions and leads to successful robust learning.

This figure visualizes the potential failure modes and their solutions in few-shot adversarial prompt learning. Subfigure (a) shows the training loss curves for three different loss functions: TeCoA loss in a failure case (unstable training), TeCoA loss in a normal case (stable training), and a proposed two-term loss which aims to balance natural and adversarial generalization. The two-term loss demonstrates better stability and convergence. Subfigure (b) presents a scatter plot showing the relationship between natural accuracy and adversarial accuracy for different training scenarios, including a pre-trained model and models trained using the TeCoA loss under normal and failure conditions (with and without manually improving natural generalization). This subfigure shows that the proposed method, represented by the two-term loss, can achieve both robust adversarial accuracy and good natural accuracy by better balancing the objectives.

This figure shows the performance comparison of different methods for adversarial few-shot learning across 11 datasets. Each subfigure represents a different dataset, displaying the natural accuracy (without adversarial attacks) and robust accuracy (with adversarial attacks) for varying numbers of training examples (shots per class). The lines connect the average accuracy across multiple experimental runs, and the points indicate individual experimental results. The figure demonstrates how the accuracy of different methods varies with the number of training examples and highlights the effectiveness of the proposed FAP method.

This figure visualizes the performance of adversarial few-shot learning across eleven datasets, comparing the natural and robust accuracies at different numbers of training examples (shots per class). The results show how the model’s performance improves with more training data. The plots include the mean accuracy and error bars, representing the average performance across multiple trials and the variability.

This figure visualizes the performance of adversarial few-shot learning across 11 different datasets, comparing the natural and robust accuracy under varying numbers of shots per class. The plots show the average performance across three trials for each dataset and shot number. Dashed lines represent natural accuracy while solid lines depict robust accuracy.

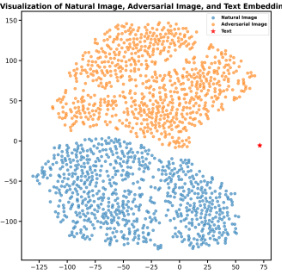

More on tables

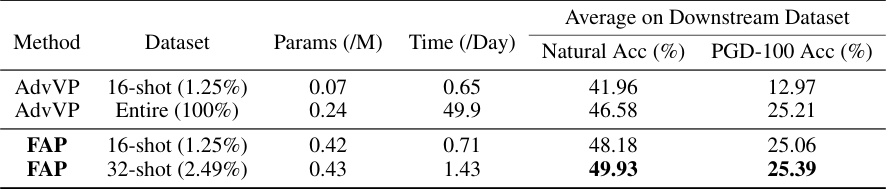

This table compares the performance of the proposed FAP method with the AdvVP method from a previous study. It shows that the FAP method, even with a small fraction (1.25%) of the ImageNet-1K dataset, achieves comparable zero-shot performance to the AdvVP method trained on the entire dataset (100%). The table also reports the training time and model parameters required for each method.

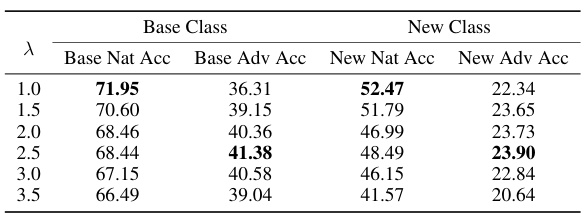

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the trade-off between natural and adversarial robustness in a few-shot adversarial prompt learning setting. The experiment varies a weight parameter (λ) that controls the balance between the natural and adversarial components of the loss function. The table shows the Base Natural Accuracy, Base Adversarial Accuracy, New Natural Accuracy, and New Adversarial Accuracy for different values of λ. The results demonstrate how adjusting λ affects both natural generalization (accuracy on clean examples) and adversarial robustness (accuracy on adversarial examples).

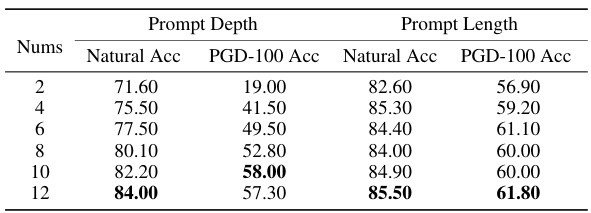

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of prompt depth and length on the performance of the proposed Few-shot Adversarial Prompt learning (FAP) framework. The experiment was conducted on the StanfordCars dataset using a 16-shot setting for adversarial prompt learning. The table shows the natural accuracy and PGD-100 accuracy (robustness) for different numbers of prompt tokens (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). The results are separated into two groups: prompt depth and prompt length. The depth refers to how many transformer layers the prompts are applied to, while the length refers to the number of tokens in the prompt.

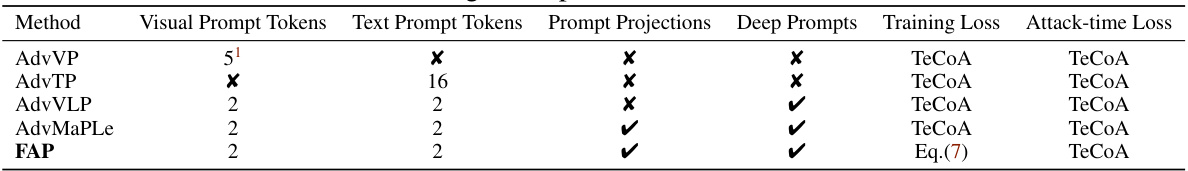

This table summarizes the design choices and loss functions used by the baselines (AdvVP, AdvTP, AdvVLP, and AdvMaPLe) and the proposed method (FAP). It clarifies the differences in prompt designs (visual and text prompt tokens, projection types, presence of deep prompts), loss functions used during training and for attack-time evaluation. The table highlights the key differences in the approach taken by each method to address adversarial robustness in the context of prompt-based learning.

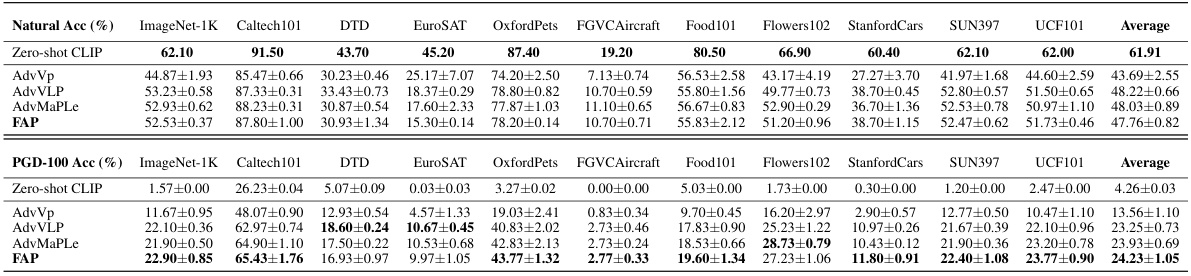

This table presents the results of a cross-dataset generalization experiment. Models were initially trained on ImageNet-1K and then evaluated on 11 diverse downstream datasets without further fine-tuning. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of both natural accuracy and robust accuracy (measured using PGD-100 attacks). The best-performing results for each dataset are highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of a cross-dataset generalization experiment. Models were initially trained on a subset of ImageNet-1K (16 shots per class). The table shows the natural accuracy and robust accuracy (using a PGD-100 attack) across 11 downstream datasets. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation and bolded numbers highlight the best-performing method for each metric.

This table presents an ablation study showing the incremental improvements achieved by the proposed method (FAP) over AdvMaPLe. It breaks down the performance gains into two key aspects: 1) Optimizing the projection direction of the prompt, and 2) Utilizing a novel training objective. The table demonstrates that each improvement contributes positively to the overall performance, with the combination of both leading to a significant enhancement.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of AdvVLP with and without the proposed learning objective (Lfinal) in a few-shot base-to-new generalization setting. It shows the average natural and adversarial accuracy on base and new classes for four different metrics: Base Natural Accuracy, Base Adversarial Accuracy, New Natural Accuracy, and New Adversarial Accuracy. The ‘+ umber’ column indicates the improvement achieved by using Lfinal compared to the baseline AdvVLP.

This table presents the results of a cross-dataset generalization experiment. The model, initially trained on a subset of ImageNet-1K, is evaluated on 10 other image recognition datasets without further fine-tuning. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the natural accuracy (clean images) and robust accuracy (images subjected to PGD-100 attacks) for each dataset. Bolded values indicate state-of-the-art performance.

This table presents the results of an adversarial base-to-new generalization experiment. The model was trained on a subset of data (base classes) and then tested on both that subset (base classes) and a new set of unseen data (new classes). The results show the natural accuracy (without adversarial attacks) and adversarial accuracy (after applying adversarial attacks) for both the base and new classes. The purpose of this experiment was to evaluate the model’s ability to generalize to new, unseen data, as well as its robustness to adversarial attacks in these new settings. The 11 different datasets represent a variety of image recognition tasks.

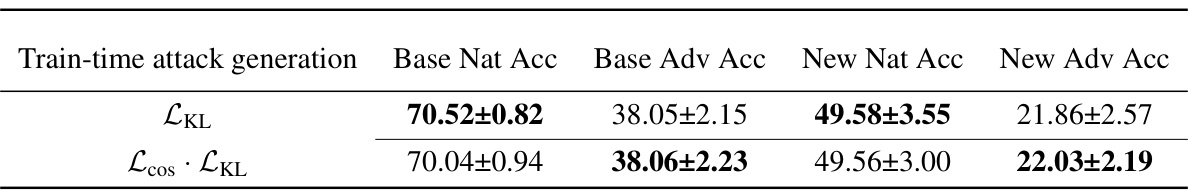

This table compares the performance of two methods for generating adversarial examples during training. The first method uses the KL divergence loss, while the second method adds a cosine similarity constraint to the KL divergence loss. The results show that the performance of both methods is very similar, suggesting that the cosine similarity constraint is not necessary for effective adversarial training.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of the proposed Few-shot Adversarial Prompt learning (FAP) method and several baselines on eleven different image recognition datasets. The results are separated into base classes (used for training) and new classes (used for testing). For each dataset and method, the natural accuracy (without adversarial attacks) and adversarial accuracy (PGD-100 accuracy with adversarial attacks) are reported for both base and new classes, providing a comprehensive assessment of the generalization ability and adversarial robustness of each approach in the base-to-new generalization setting.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of the proposed Few-shot Adversarial Prompt Learning (FAP) framework, as well as several baseline methods, on 11 different image recognition datasets. The evaluation is done in a base-to-new generalization setting, where models are trained on a subset of classes (base classes) and then tested on both the base and unseen classes (new classes). For each dataset and method, the table shows the natural accuracy (without adversarial attacks) and adversarial accuracy (with PGD-100 attacks) for both base and new classes. This allows for a comprehensive assessment of both the natural generalization ability and adversarial robustness of the various methods.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of the proposed Few-shot Adversarial Prompt Learning (FAP) method, along with several baseline methods, on 11 different image recognition datasets. The performance is evaluated in a base-to-new generalization setting, meaning that the models are trained on a subset of the classes (base classes) and then tested on both the training classes and a set of new classes. The table reports both the natural accuracy (standard accuracy) and the adversarial accuracy (accuracy against PGD-100 attacks) for each dataset and class type (base and new). This allows for a comprehensive assessment of the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data while maintaining robustness to adversarial attacks.

Full paper#