TL;DR#

This research explores how deep neural networks learn language structure from data, addressing the ‘poverty of the stimulus’ argument in linguistics. It investigates the relationship between the amount of training data and the ability of the network to capture increasingly complex hierarchical structures within the language. The challenge lies in understanding how much data is needed for effective language acquisition by these models, particularly regarding the depth of hierarchical representations learned.

The study utilizes a probabilistic context-free grammar to generate synthetic datasets, allowing for analytical investigation of the token-token correlations. Researchers demonstrate that these correlations decay with distance, and a finite training set effectively limits the usable range. This leads to a series of ‘steps’ in model performance, with each step representing the emergence of a deeper hierarchical level. This theory was empirically validated in both synthetic and real language datasets (Shakespeare’s works, Wikipedia), demonstrating the connection between training data size, correlation range, and the depth of hierarchical representations learned. This research offers a new theoretical explanation for empirical phenomena such as the scaling of test loss with dataset size in deep learning models, advancing our understanding of language acquisition by these models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep learning and linguistics because it provides a novel theoretical framework to understand how language structure is learned by deep neural networks. It bridges the gap between formal language theory and statistical learning, offering insights into the scaling laws of language models and the emergence of hierarchical representations. The findings challenge existing assumptions about language acquisition and open new avenues for improving model training and design.

Visual Insights#

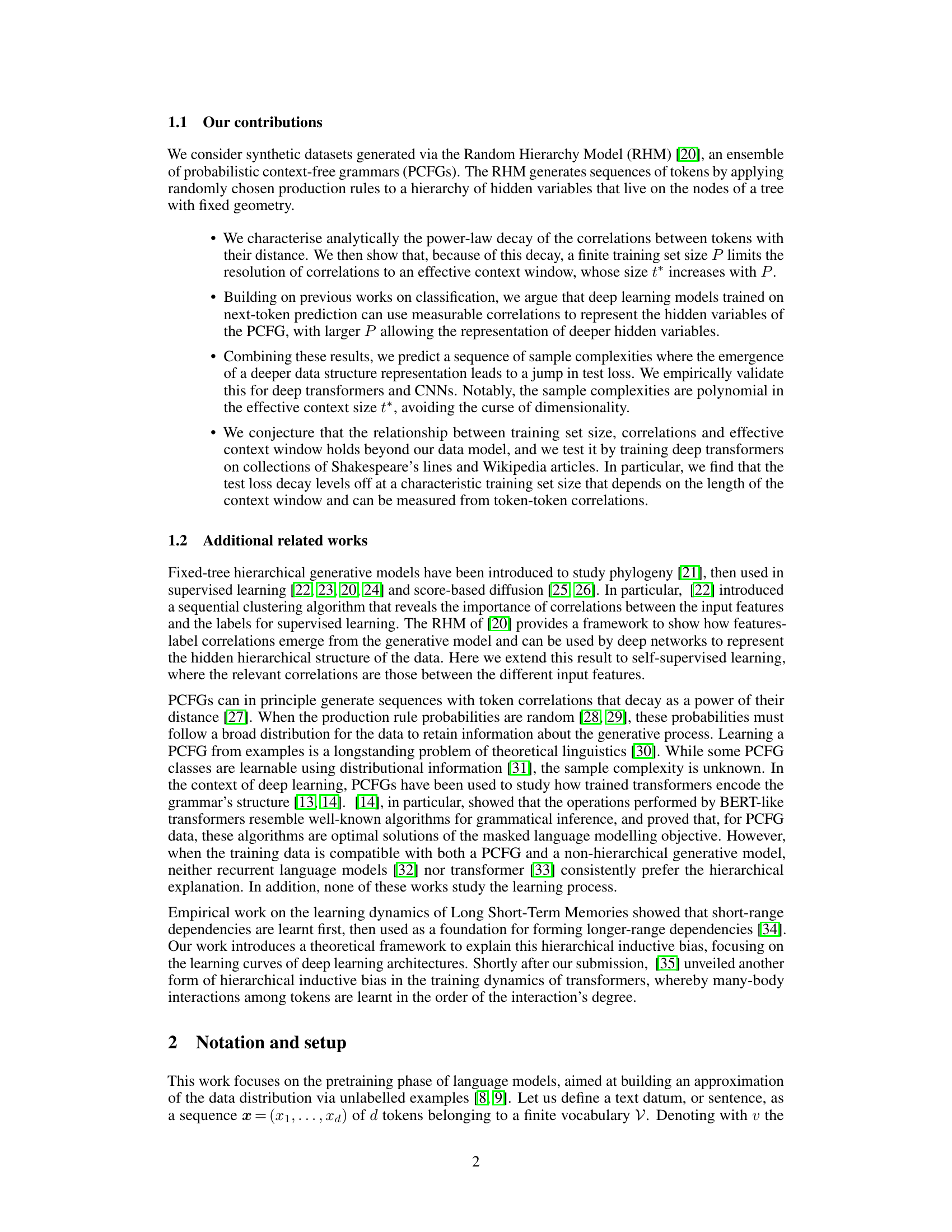

🔼 The figure shows an example of data generation using the Random Hierarchy Model (RHM) and the correlation functions of RHM data. The left panel illustrates the hierarchical tree structure of the RHM, where each node represents a hidden variable and the leaves represent observable tokens. The right panel compares the empirical and analytical correlation functions, demonstrating how the correlation between tokens decays stepwise with distance, mirroring the hierarchical structure. A finite training set limits the effective range of measurable correlations, which is shown by the saturation of the empirical estimates at a certain distance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Left: Example of data generation according to the RHM, with depth L = 3 and branching factor s = 2. Starting from the root with l = 3 and following the arrows, each level-l symbol is replaced with a pair of lower-level symbols, down to the leaves with l = 0. Right: Empirical (coloured) and analytical (black dashed) correlation functions of RHM data, with L = 3, s = 2, v = 32 and m = 8. The stepwise decay mirrors the tree structure of the generative model. Empirical estimates obtained from P examples initially follow the true correlation function, but then saturate due to the sampling noise (coloured dashed). As a result, a finite training set only allows for measuring correlations with the tokens up to a certain distance t*(P). Graphically, t*(P) corresponds to the highest value of t where the empirical estimate matches the true correlation (e.g. 1 for the orange and green curves, 3 for the red curve).

In-depth insights#

Language Acquisition#

The study of language acquisition in deep neural networks is a complex and multifaceted field. The paper explores how the architecture of a model, the amount of training data, and the nature of the data itself all play crucial roles in the model’s ability to learn and represent linguistic structure. The emergence of hierarchical representations is a key finding, as models trained on larger datasets develop a deeper understanding of language’s hierarchical nature, from short-range to long-range dependencies. The relationship between training set size and the effective context window is particularly significant. A limited training set constrains the model’s ability to learn long-range relationships, leading to a saturation in performance improvements. The paper proposes that this relationship extends beyond synthetic datasets and provides empirical evidence supporting this claim. Analytical characterizations of correlation decay, mirrored by a stepwise behavior in model training, further supports the model’s incremental learning process. While the paper focuses on self-supervised learning via next-token prediction, the insights gleaned from this work offer valuable contributions to our broader understanding of how deep learning models learn and process language, and how we might improve training paradigms. Further investigation into the impact of model architecture and the generalizability of the observed relationships to more complex natural language scenarios are key areas of future research.

RHM Data Analysis#

An analysis of data generated by the Random Hierarchy Model (RHM) would likely focus on the hierarchical structure inherent in the data. Key aspects would include examining the power-law decay of correlations between tokens as a function of distance, a signature of the RHM’s hierarchical generative process. The analysis would investigate how the effective range of these correlations scales with the size of the training dataset, revealing insights into how deep learning models learn hierarchical representations. A comparison of empirical findings to theoretical predictions derived from the RHM’s structure is crucial, and the emergence of deeper levels of representation, marked by discontinuities in the learning curves, would be a significant area of focus. The impact of context window size on model performance, and the theoretical relationship between training set size, correlation range, and the effective context window are also of great interest. Finally, the study would likely explore the generality of these findings beyond synthetic RHM data, evaluating their applicability to real-world linguistic datasets like Shakespeare’s works or Wikipedia articles, assessing the robustness of the observations.

Transformer Training#

Transformer training, in the context of language modeling, involves using massive datasets to teach transformer networks to predict the next word in a sequence. This process is computationally expensive, requiring significant hardware and energy. The effectiveness of training is highly dependent on several factors, including the size of the training dataset, the model architecture’s capacity, and the training optimization techniques. Larger models generally exhibit better performance on downstream tasks but necessitate substantially more resources. Hyperparameter tuning also significantly affects the model’s final performance. The optimal settings often need extensive experimentation and are highly dependent on specific datasets. Furthermore, training stability and preventing overfitting are critical challenges; techniques like dropout, regularization, and early stopping are vital for mitigating these issues. Research in this field constantly explores improvements in training efficiency and scalability, including novel architectures, optimization algorithms, and data augmentation strategies.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the study’s claims using real-world data or controlled experiments. It would involve designing specific tests to directly assess hypotheses, selecting appropriate datasets, choosing relevant evaluation metrics and ensuring statistical rigor to minimize bias. Detailed descriptions of the datasets, including their size, sources, and characteristics, are crucial for reproducibility. Methodological transparency is key, with clear explanations of experimental procedures and data analysis techniques. Statistical significance tests determine if observed results are likely due to chance or a genuine effect, while error bars or confidence intervals quantify the uncertainty around measurements. The results should be presented clearly and concisely, often through tables and figures, showing the relationship between the observed data and theoretical predictions. Any discrepancies between empirical findings and theoretical models should be carefully discussed, and potential limitations of the empirical approach explicitly acknowledged. A strong empirical validation section builds confidence in the research’s conclusions by demonstrating its real-world applicability and robustness.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore context-sensitive extensions of the proposed framework, moving beyond context-free grammars to capture the complexities of real-world language. Investigating the interaction between hierarchical structure and other linguistic phenomena like long-distance dependencies would provide a more nuanced understanding. The impact of architectural choices in deep learning models on the acquisition of language structure requires further investigation, comparing different architectures systematically to determine their inductive biases. Additionally, analyzing how the emergence of specific language skills relates to scaling laws offers promising avenues, particularly focusing on the interplay between model size, data scale, and the complexity of tasks performed. Finally, applying this framework to study language evolution and cross-linguistic variation could reveal valuable insights into the universality and diversity of language acquisition.

More visual insights#

More on figures

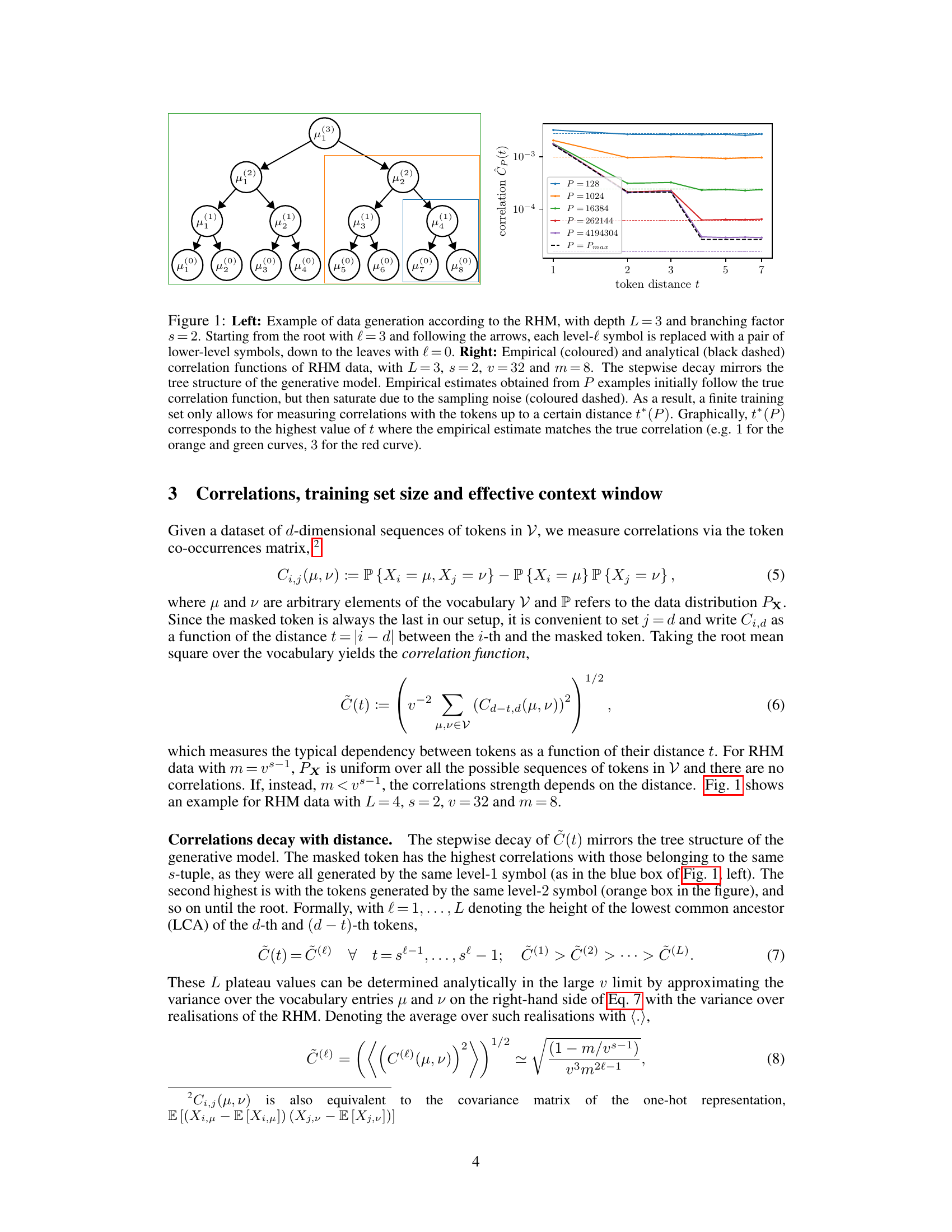

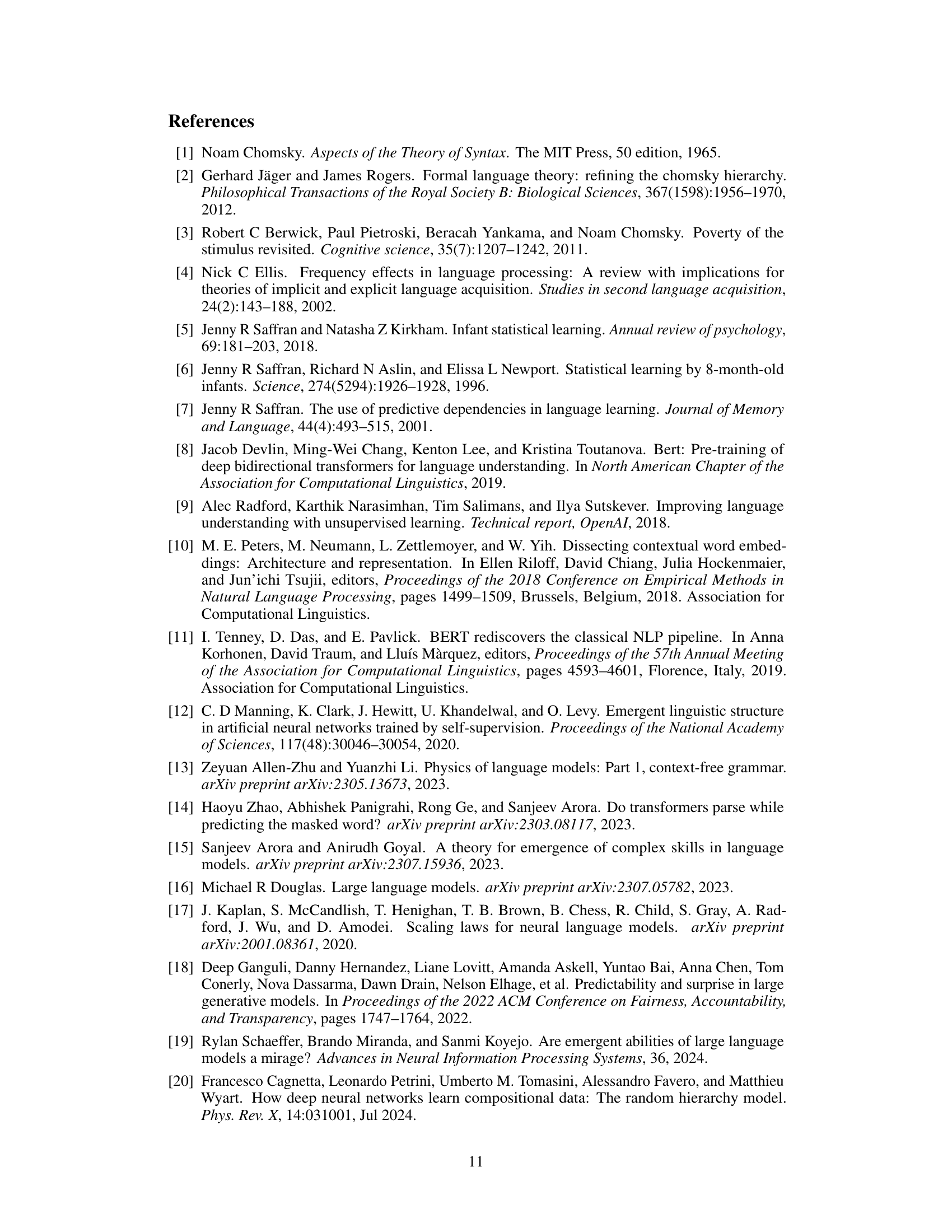

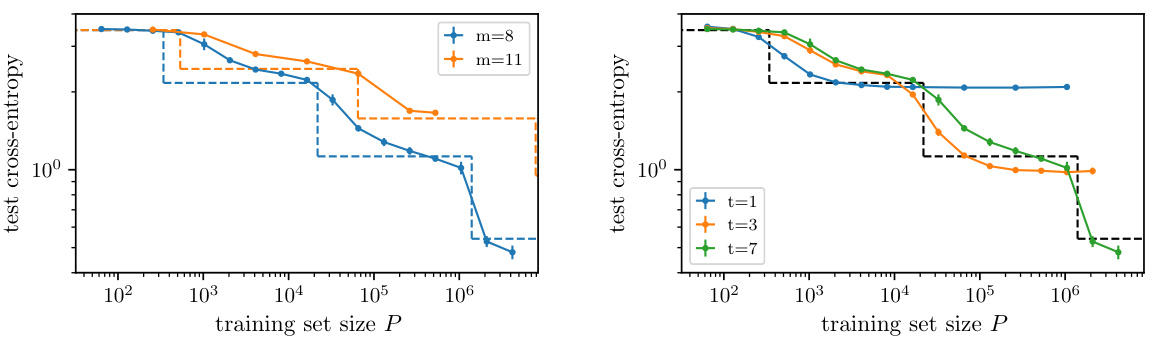

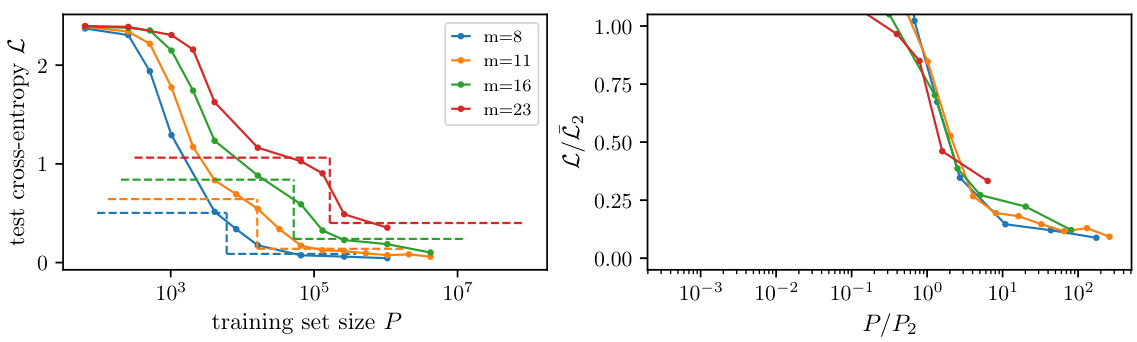

🔼 The left panel shows stepwise learning curves of depth-3 transformers trained on the Random Hierarchy Model (RHM) dataset. The steps correspond to the model learning progressively larger sub-trees of the data’s hierarchical structure, mirroring the stepwise decay of the correlation function. The right panel demonstrates how limiting the context window size saturates the test loss decay, highlighting the importance of context window size in learning hierarchical structures.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: Learning curves of depth-3 transformers trained on RHM data with L = 3, s = 2, v = 32 and m = 8 (blue) or 11 (orange, both are averaged over 8 independent realisations of the dataset and initialisations of the network), displaying a stepwise behaviour analogous to the correlation function. The vertical dashed lines mark the characteristic training set sizes Pk at which the correlation with tokens at distances up to t = sk−1 emerge from the sampling noise. Horizontal dashed lines represent (upper bounds on) the cross-entropy of the probability of the last token conditioned on the previous sk−1, suggesting that the steps correspond to the model learning a progressively larger sub-tree of the data structure. Right: Learning curves of transformers for m = 8 and different sizes t of the context window. The saturation of the loss decay due to the finite context window highlights that the decay is entirely due to the ability to leverage a larger portion of the context window.

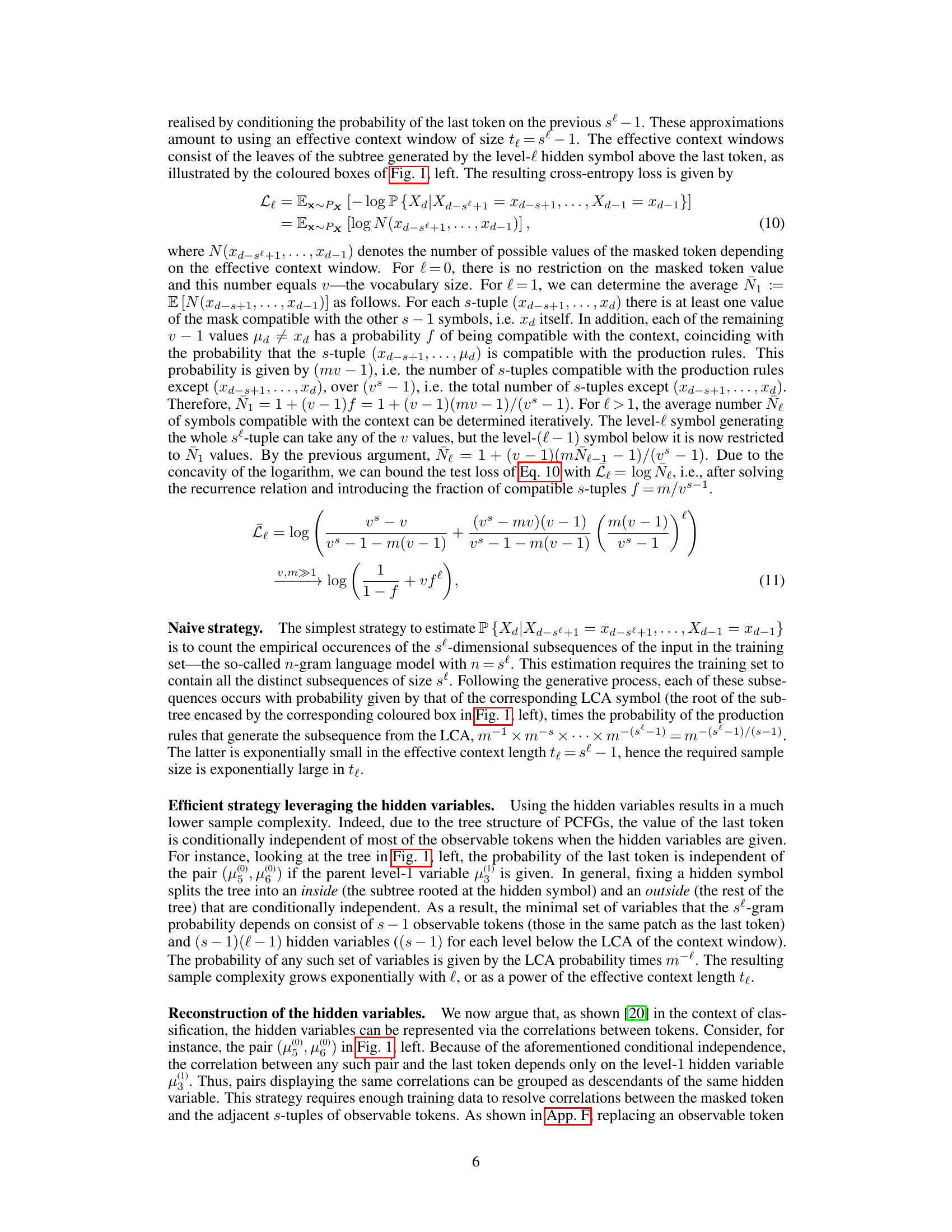

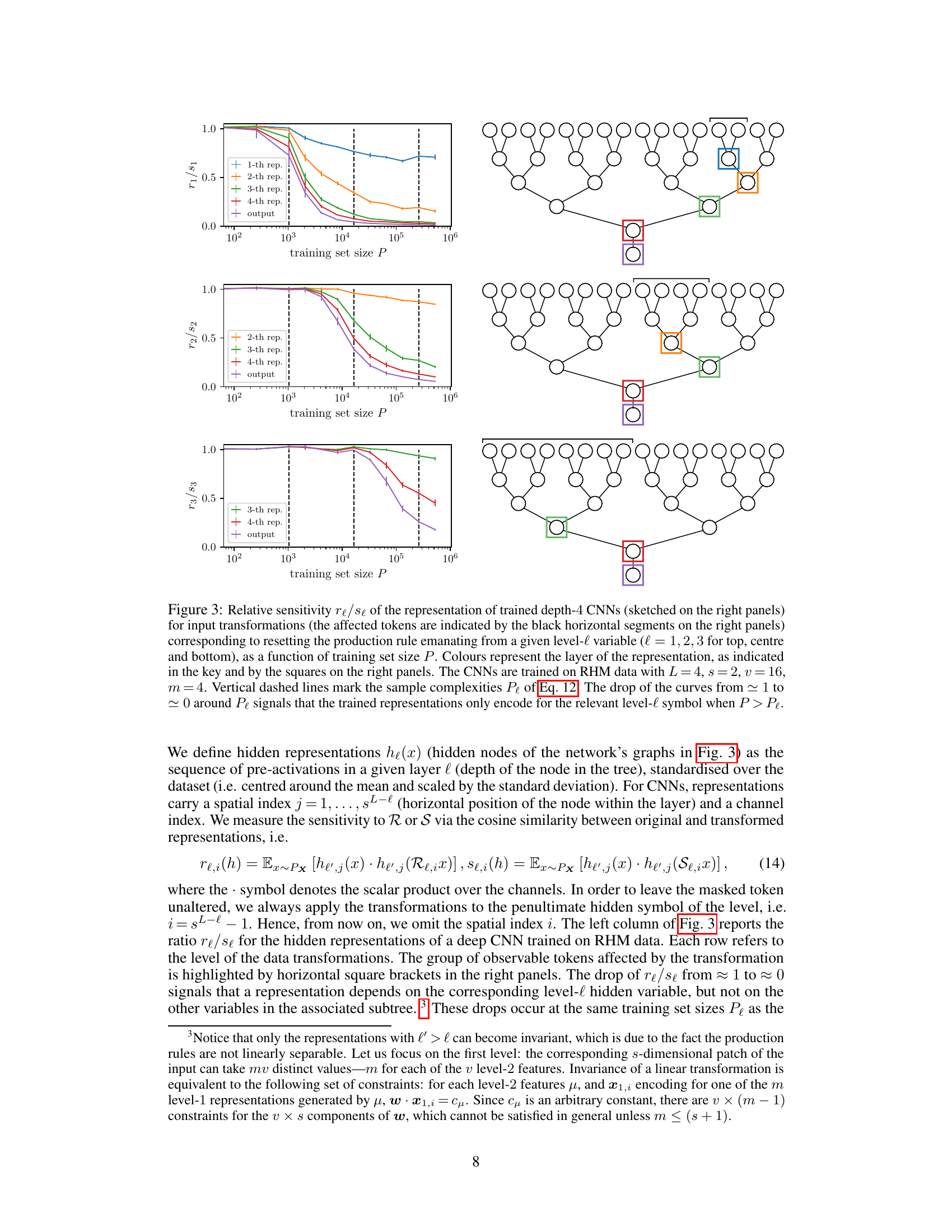

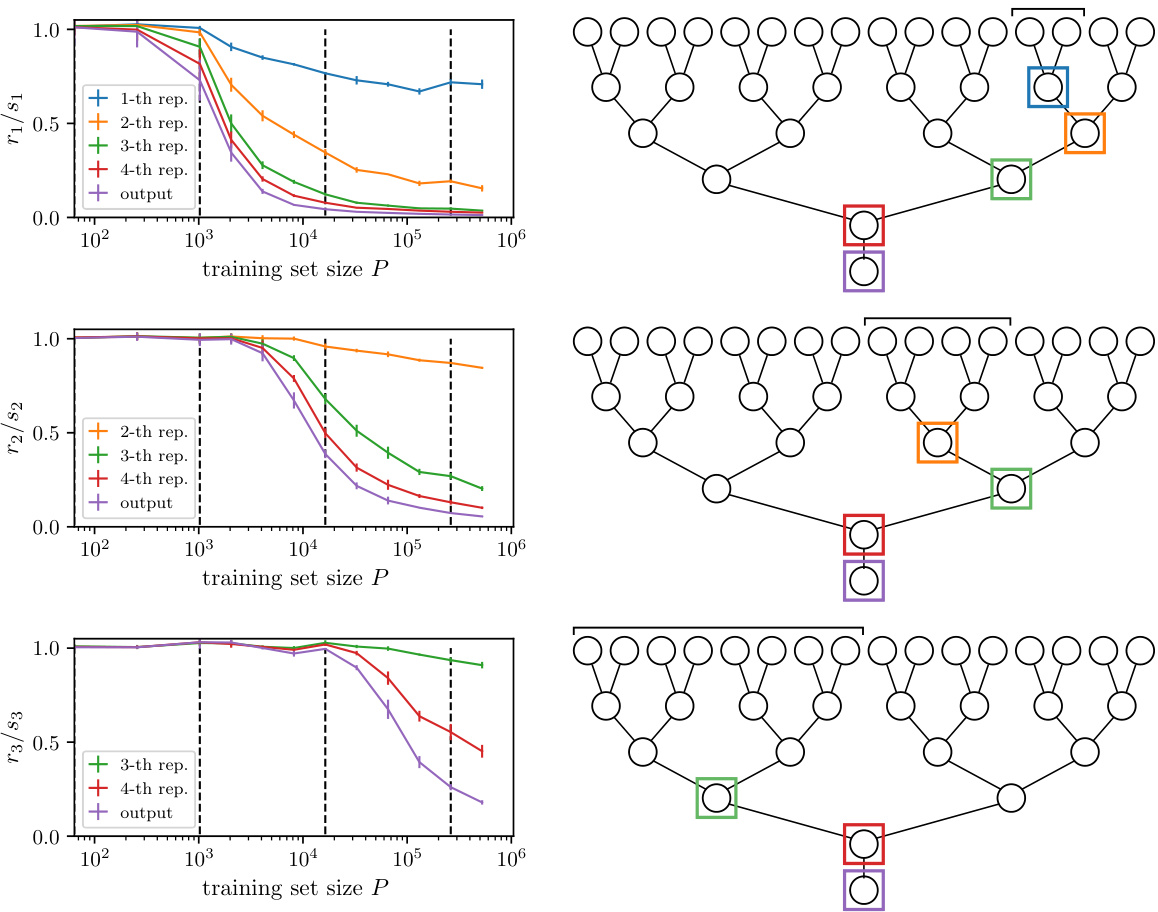

🔼 This figure shows the relative sensitivity of the representation of trained depth-4 CNNs to input transformations as a function of training set size. The transformations involve resetting the production rule emanating from a given level-l variable. The figure demonstrates that the trained representations only encode the relevant level-l symbol when the training set size (P) exceeds a certain threshold (Pe). This threshold, which is determined by the sample complexity, marks the emergence of deeper representations of the data structure in the model.

read the caption

Figure 3: Relative sensitivity re/se of the representation of trained depth-4 CNNs (sketched on the right panels) for input transformations (the affected tokens are indicated by the black horizontal segments on the right panels) corresponding to resetting the production rule emanating from a given level-l variable (l = 1, 2, 3 for top, centre and bottom), as a function of training set size P. Colours represent the layer of the representation, as indicated in the key and by the squares on the right panels. The CNNs are trained on RHM data with L = 4, s = 2, v = 16, m = 4. Vertical dashed lines mark the sample complexities Pe of Eq. 12. The drop of the curves from ~ 1 to ~0 around Pe signals that the trained representations only encode for the relevant level-l symbol when P > Pe.

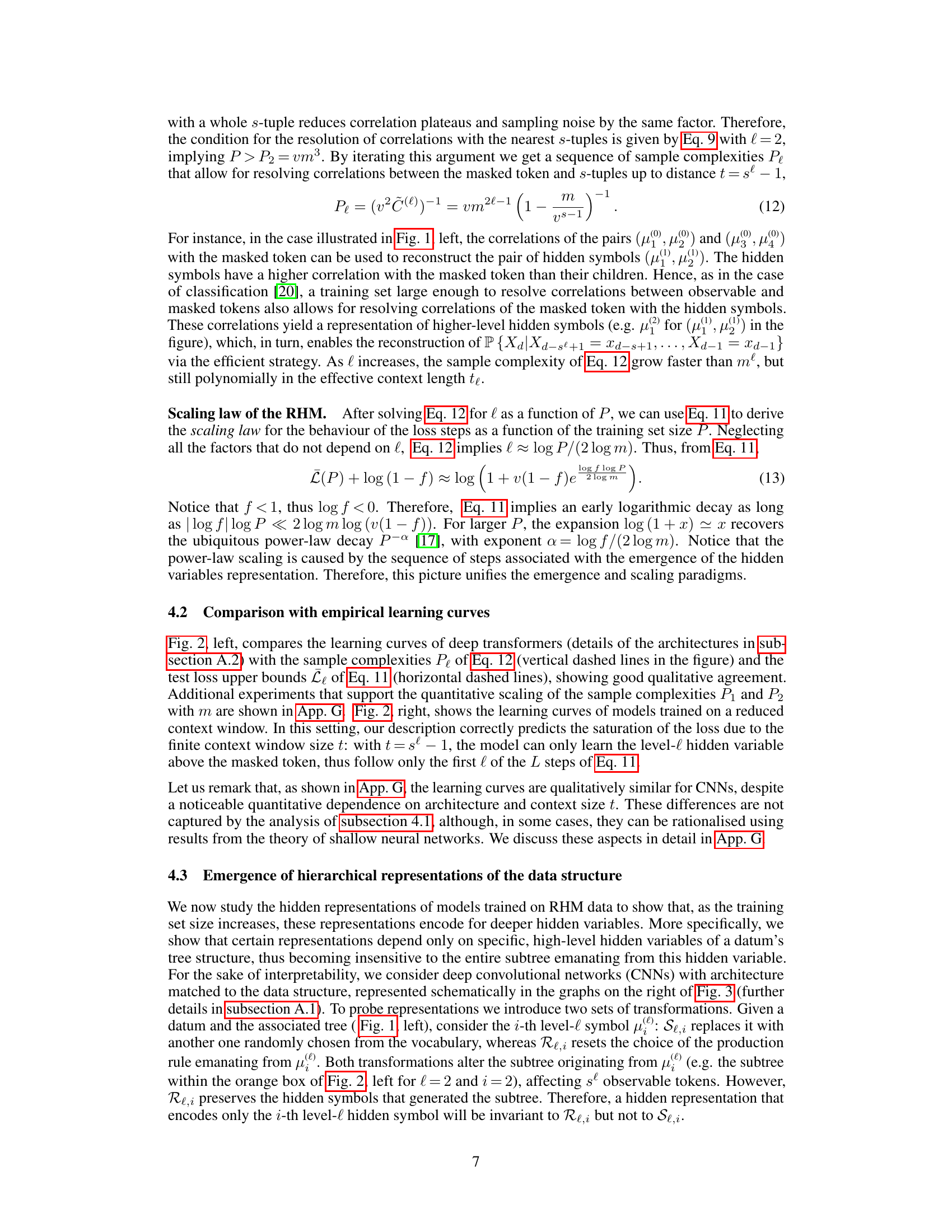

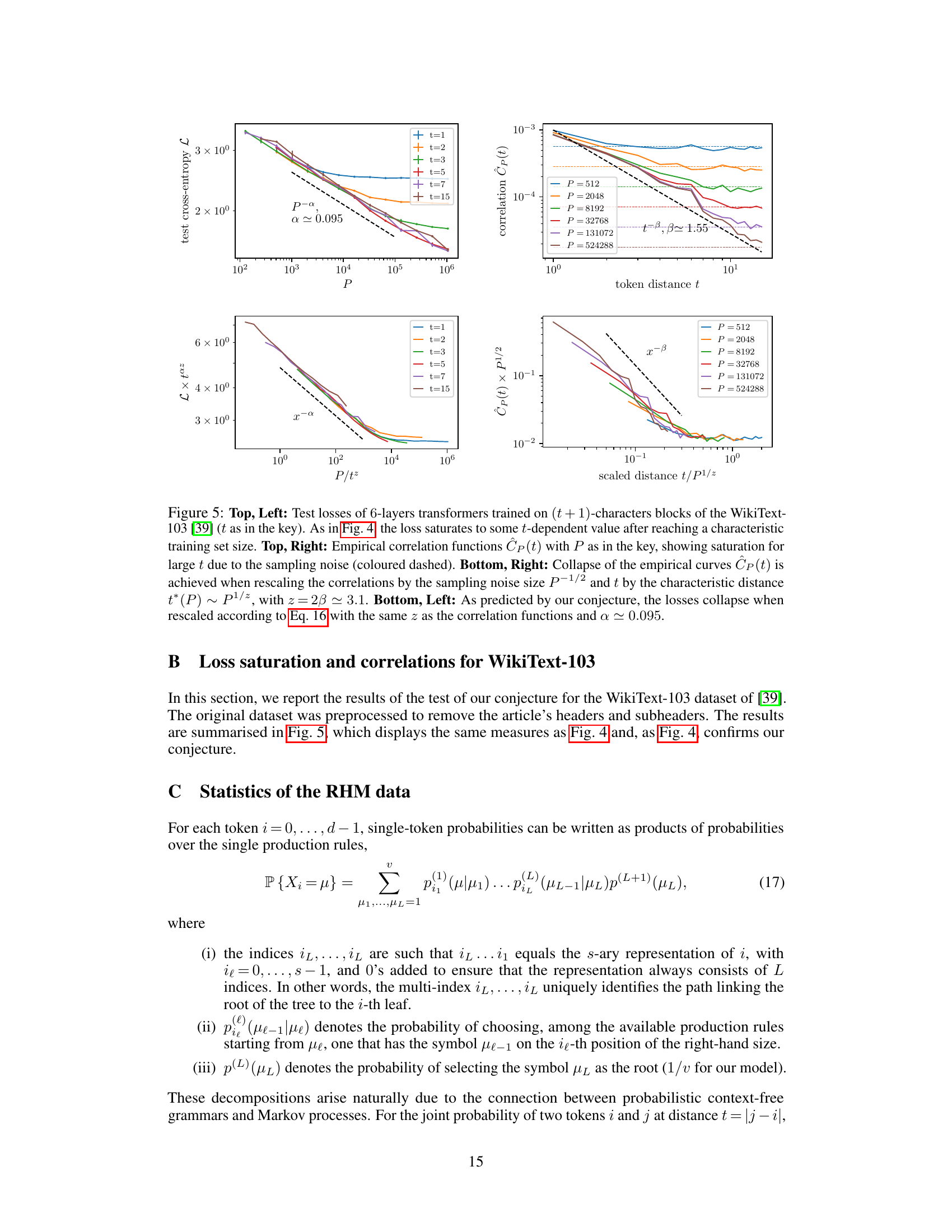

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments on the tiny Shakespeare dataset. The left panels show the test loss of 3-layer transformers trained on (t+1)-character blocks for different context window sizes (t). The loss saturates at a t-dependent value, indicating that larger context windows improve performance as more information is available. The right panels display empirical correlation estimates for different training set sizes, showing how correlation functions decay with distance, and how they can collapse when rescaled by sampling noise and characteristic distance.

read the caption

Figure 4: Top, Left: Test losses of 3-layers transformers trained on (t+1)-characters blocks of the tiny-Shakespeare dataset [38] (t as in the key). The saturation of the loss to some t-dependent value indicates that performance improves with P because the model can use information from a larger context window. Top, Right: Empirical estimates Ĉp(t) for different training set sizes P as in the key. The curves initially follow the true correlation C(t) (black dashed), but then saturate due to the sampling noise (coloured dashed). Bottom, Right: The empirical curves CP(t) collapse when rescaling correlations by the sampling noise size P-1/2 and t by the characteristic distance t* (P) ~ P1/2, with z ~ 2.8. Bottom, Left: As predicted by our conjecture, the losses collapse when rescaled according to Eq. 16 with the same z as the correlation functions.

🔼 The figure displays the results of experiments on the Tiny Shakespeare dataset. The leftmost plot shows the test loss of 3-layer transformers trained on character blocks of variable length. The test loss saturates to a value dependent on the context window size, which is consistent with the conjecture that only relevant information within a P-dependent effective context window can be extracted. The top-right plot shows empirical estimates of correlation functions for different training set sizes P, which initially follow the theoretical correlation function but saturate due to sampling noise. The bottom-right plot demonstrates data collapse of the empirical correlation curves after rescaling them by the sampling noise size and the characteristic distance. The bottom-left plot shows the same data collapse after rescaling the test losses according to the same characteristic distance.

read the caption

Figure 4: Top, Left: Test losses of 3-layers transformers trained on (t+1)-characters blocks of the tiny-Shakespeare dataset [38] (t as in the key). The saturation of the loss to some t-dependent value indicates that performance improves with P because the model can use information from a larger context window. Top, Right: Empirical estimates Ĉp(t) for different training set sizes P as in the key. The curves initially follow the true correlation C(t) (black dashed), but then saturate due to the sampling noise (coloured dashed). Bottom, Right: The empirical curves CP(t) collapse when rescaling correlations by the sampling noise size P-1/2 and t by the characteristic distance t* (P) ~ P1/2, with z ~ 2.8. Bottom, Left: As predicted by our conjecture, the losses collapse when rescaled according to Eq. 16 with the same z as the correlation functions.

🔼 The figure shows the learning curves of depth-3 transformers and their stepwise behavior. The left panel shows the learning curves when trained with different numbers of production rules. The right panel shows how the loss saturates as the context window increases.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: Learning curves of depth-3 transformers trained on RHM data with L = 3, s = 2, v = 32 and m = 8 (blue) or 11 (orange, both are averaged over 8 independent realisations of the dataset and initialisations of the network), displaying a stepwise behaviour analogous to the correlation function. The vertical dashed lines mark the characteristic training set sizes Pk at which the correlation with tokens at distances up to t = sk-1 emerge from the sampling noise. Horizontal dashed lines represent (upper bounds on) the cross-entropy of the probability of the last token conditioned on the previous sk-1, suggesting that the steps correspond to the model learning a progressively larger sub-tree of the data structure. Right: Learning curves of transformers for m = 8 and different sizes t of the context window. The saturation of the loss decay due to the finite context window highlights that the decay is entirely due to the ability to leverage a larger portion of the context window.

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves of depth-3 Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) trained on synthetic data generated by the Random Hierarchy Model (RHM). The RHM is a probabilistic context-free grammar model that captures many hierarchical structures found in natural languages. Different curves represent different values of m, which is a parameter in the RHM related to the number of production rules. The left panel displays the learning curves showing a stepwise behaviour. The right panel shows the same data after rescaling P (the training set size) with P₁ (the characteristic training set size at which the first step emerges) and L (test cross-entropy loss) with L₀ = log v (v is the vocabulary size). The collapse of the curves in the right panel supports the analytical prediction about the scaling behaviour of P₁ with m (the number of production rules).

read the caption

Figure 7: Learning curves of depth-3 CNNs trained on RHM data with L = 3, s = 3, v = 11 and m as in the key. Dashed curves highlight our prediction for the first step. In the right panel, the first step is made to collapse by rescaling P with P₁ and L with L₀ = log v. The collapse confirms our prediction on the behaviour of P₁ with m.

🔼 This figure displays the learning curves of depth-3 CNNs trained on data generated by the Random Hierarchy Model (RHM) with varying numbers of production rules (m). The left panel shows the learning curves for different values of m, with the dashed lines representing the theoretical predictions. The right panel shows the same data after rescaling the training set size (P) by the predicted sample complexity for the first step (P1) and the test loss (L) by the theoretical loss value at the first step (L0). The collapse of the curves in the right panel confirms the theoretical prediction of the scaling law for P1 with m.

read the caption

Figure 7: Learning curves of depth-3 CNNs trained on RHM data with L = 3, s = 3, v = 11 and m as in the key. Dashed curves highlight our prediction for the first step. In the right panel, the first step is made to collapse by rescaling P with P₁ and L with Lo = log v. The collapse confirms our prediction on the behaviour of P₁ with m.

🔼 The figure shows the results of experiments on the tiny-Shakespeare dataset. The left panels show the learning curves for different context window sizes, demonstrating how the test loss saturates at a value that depends on the context window size. The right panels illustrate the correlation functions, showing how they collapse when scaled appropriately, supporting the conjecture that a finite training set limits the resolution of correlations to an effective context window whose size increases with the size of the training set. The bottom panels further demonstrate this scaling behavior, showcasing that the loss curves collapse when rescaled using the theoretically predicted scaling law.

read the caption

Figure 4: Top, Left: Test losses of 3-layers transformers trained on (t+1)-characters blocks of the tiny-Shakespeare dataset [38] (t as in the key). The saturation of the loss to some t-dependent value indicates that performance improves with P because the model can use information from a larger context window. Top, Right: Empirical estimates Ĉp(t) for different training set sizes P as in the key. The curves initially follow the true correlation C(t) (black dashed), but then saturate due to the sampling noise (coloured dashed). Bottom, Right: The empirical curves CP(t) collapse when rescaling correlations by the sampling noise size P-1/2 and t by the characteristic distance t* (P) ~ P1/2, with z ~ 2.8. Bottom, Left: As predicted by our conjecture, the losses collapse when rescaled according to Eq. 16 with the same z as the correlation functions.

Full paper#