↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Modeling multivariate time series is challenging due to the complexity of dependencies along both time and variate axes, and the need for efficient training and inference with very long sequences. Existing methods, including traditional state space models (SSMs) and deep learning models, struggle to capture both linear and non-linear dependencies efficiently, or have limited expressive power to handle complex patterns like seasonality. They often require significant manual pre-processing and model selection.

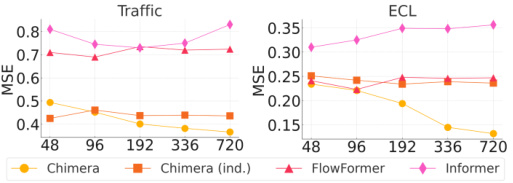

The proposed model, Chimera, is a novel variation of 2D SSMs designed to overcome these issues. It uses two SSM heads with different discretization processes and input-dependent parameters to learn long-term progressions, seasonal patterns, and dynamic autoregressive processes effectively. A fast training algorithm, based on a 2D parallel selective scan, is introduced to significantly improve efficiency. Extensive benchmarks, including ECG and speech time series classification, show Chimera’s superior performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with multivariate time series due to its novel approach of using 2D state space models. It offers a provably expressive model capable of handling complex dependencies, seasonal patterns, and long sequences efficiently. This addresses a critical limitation of existing methods, opening up avenues for improved forecasting, classification, and anomaly detection across various applications, such as healthcare and finance.

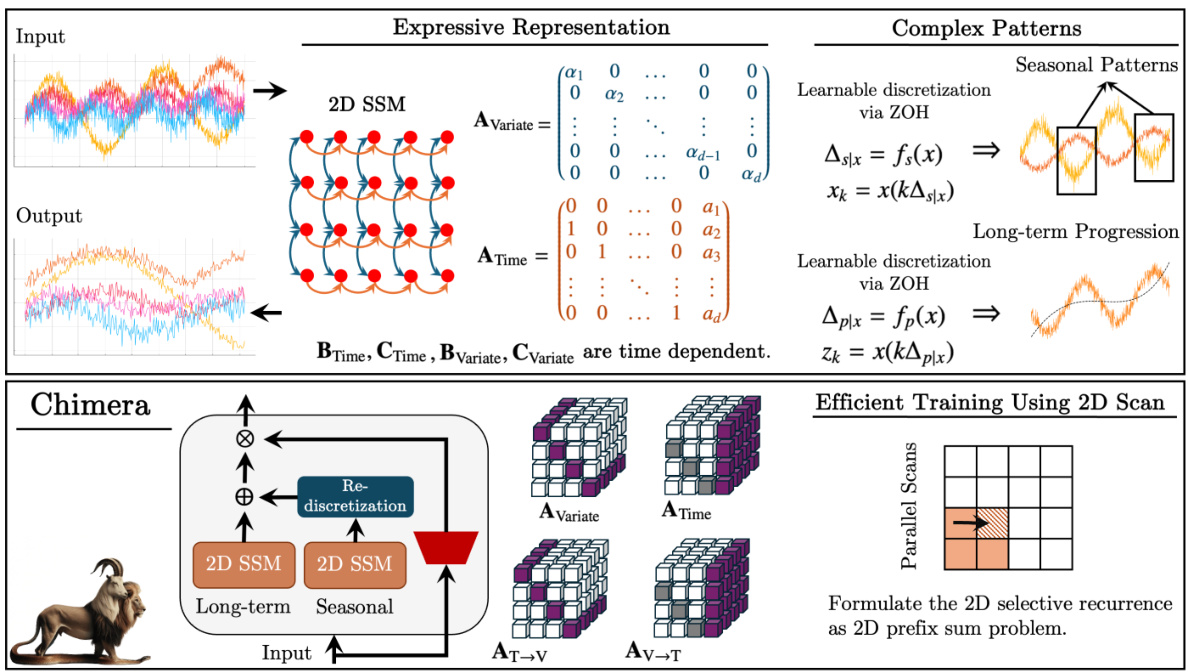

Visual Insights#

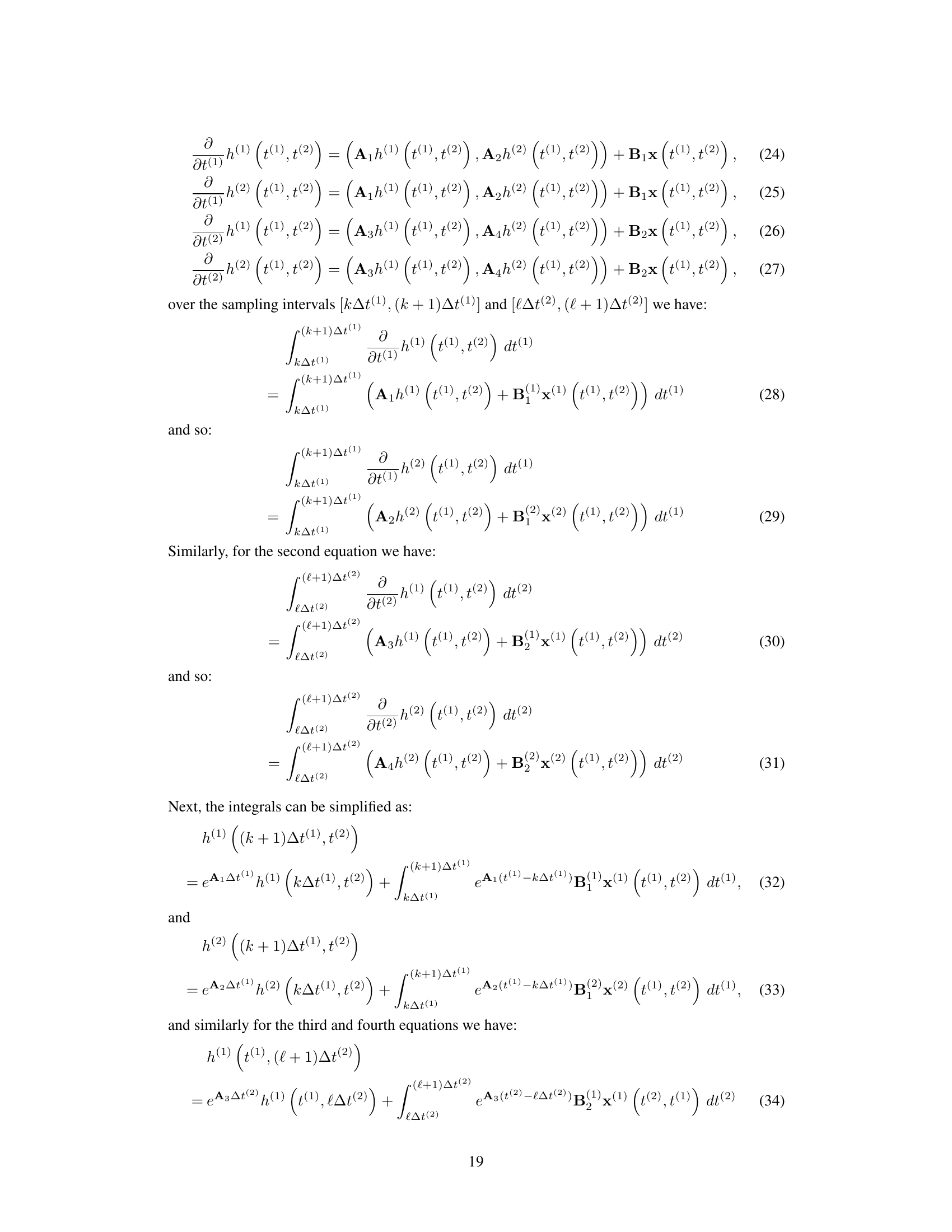

This figure provides a high-level overview of the Chimera architecture, highlighting its key components and how they work together. It shows the input multivariate time series, which is processed by a two-headed 2-dimensional state-space model (SSM). Each head uses a learnable discretization process (Zero-Order Hold) to capture seasonal and long-term patterns. The two SSM heads produce outputs that are combined to create a final, expressive representation of the time series. The figure also illustrates how the 2D recurrence is reformulated as a 2D prefix sum problem to enable efficient parallel training.

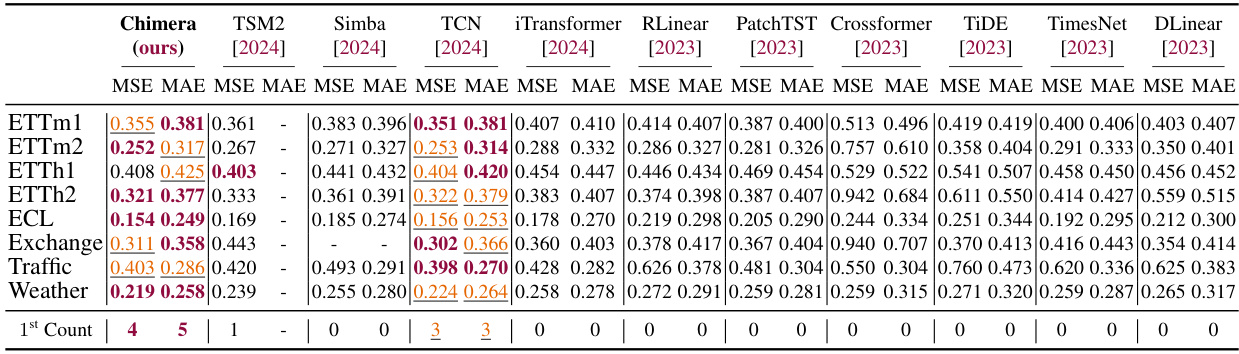

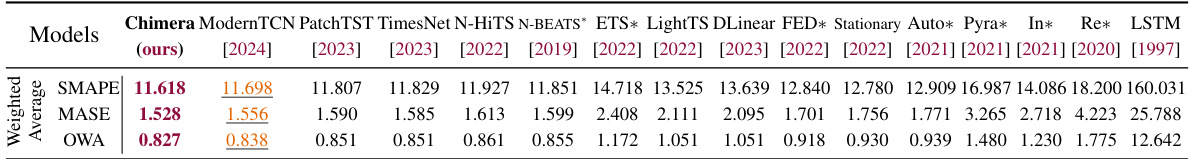

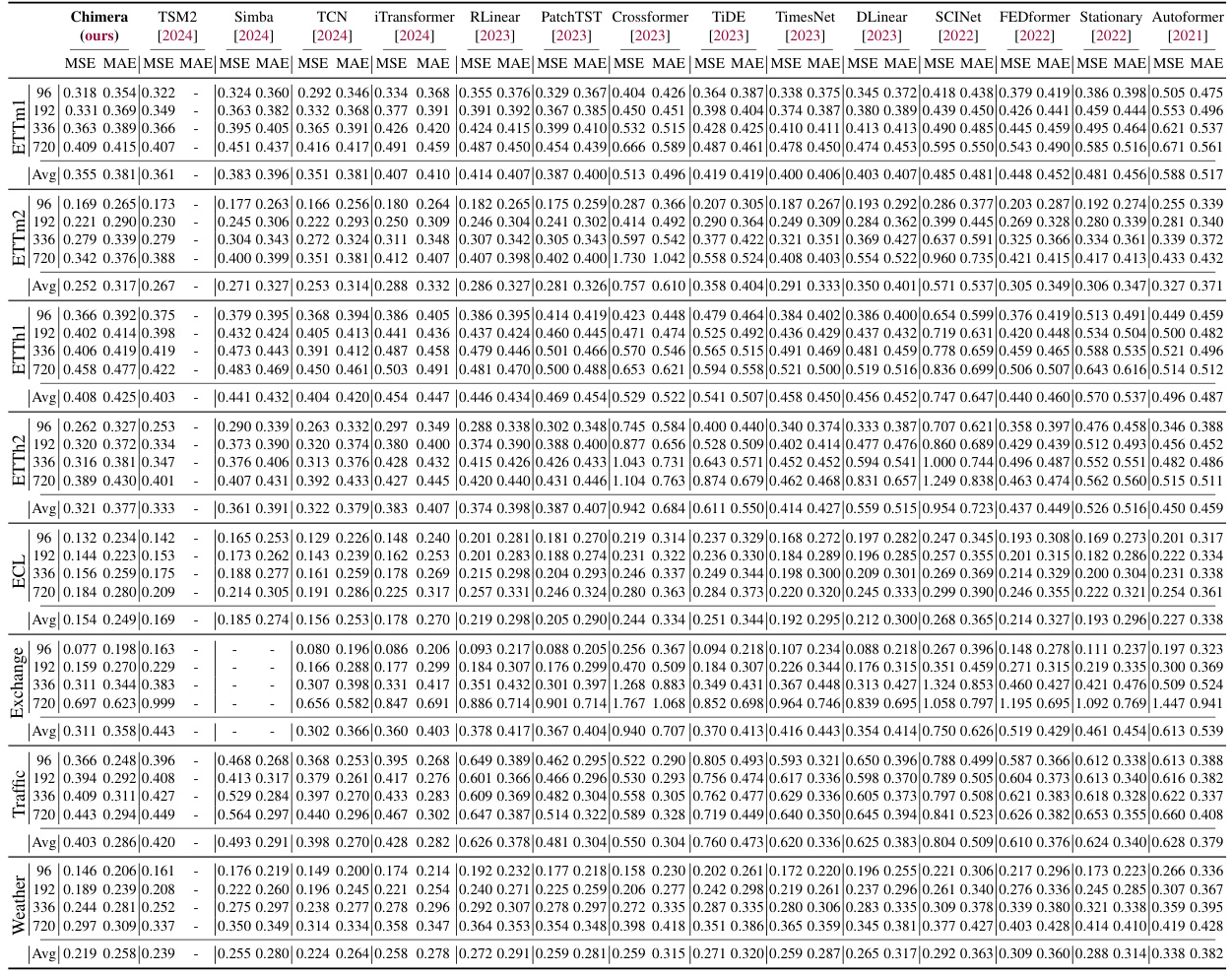

This table presents the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) achieved by Chimera and other state-of-the-art models on eight different long-term forecasting datasets. The best and second-best performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. The full results, including individual horizon results, are available in Appendix I.

In-depth insights#

2D SSM: A Deep Dive#

A hypothetical section titled ‘2D SSM: A Deep Dive’ in a research paper would likely delve into the intricacies of two-dimensional state-space models. It would likely begin by contrasting 1D SSMs with their 2D counterparts, highlighting the increased capacity of 2D SSMs to capture complex spatiotemporal dependencies present in multivariate time series data. The discussion would then move towards the mathematical foundations of 2D SSMs, exploring their state-space representations, transition matrices, and observation models. A key aspect would likely be a detailed examination of the challenges and opportunities associated with parameterization and training of these models, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data. The deep dive might also include discussions about efficient training algorithms, and explain how 2D SSMs can be leveraged within deep learning architectures. Finally, it could showcase practical applications across different domains and provide comparative analyses against other deep learning-based time series models, demonstrating the advantages and limitations of 2D SSMs in various contexts. The section would likely conclude by outlining potential areas for future research, such as exploring novel architectures or addressing scalability concerns for even larger datasets.

Chimera’s Architecture#

Chimera’s architecture is a novel three-headed, two-dimensional state-space model (SSM) designed for effective multivariate time series modeling. Its architecture incorporates multiple SSM heads to learn diverse temporal patterns. One head focuses on learning long-term progressions, while another is specifically designed for capturing seasonal patterns. The third head facilitates the adaptive selection of relevant variates, crucial for handling high-dimensional data. Each SSM leverages carefully parameterized transition matrices to control the length of dependencies learned. Importantly, Chimera employs a 2D parallel selective scan algorithm for efficient training, significantly improving computational efficiency compared to traditional methods. This efficient training stems from re-formulating the 2D recurrence as a prefix sum problem, enabling parallel processing. The input-dependent parameterization allows for dynamic adjustments of the model’s focus based on the input data, enhancing its adaptability and expressiveness. Chimera’s architecture represents a significant advancement, offering high expressive power with efficient training and inference for complex multivariate time series.

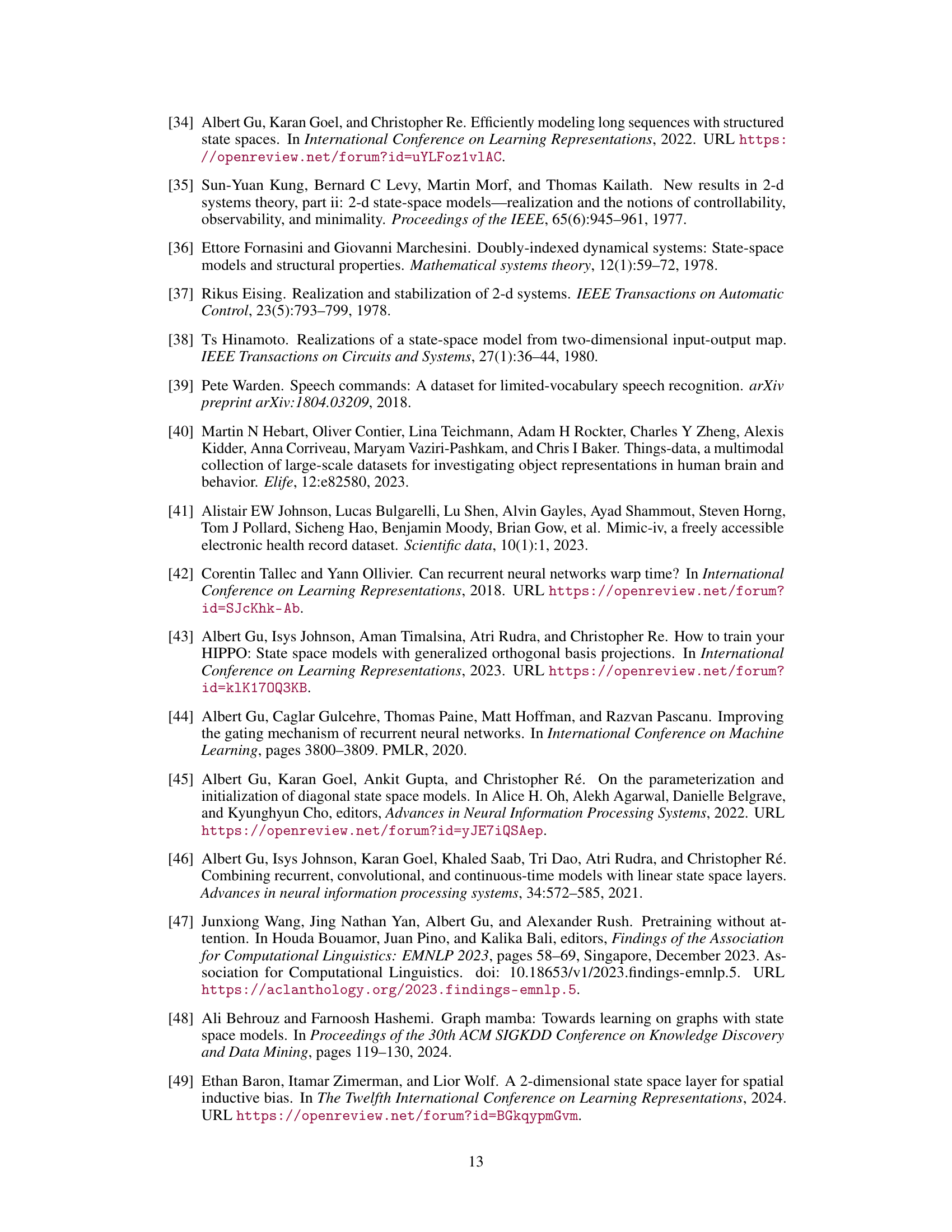

Experimental Results#

A thorough analysis of the ‘Experimental Results’ section requires a multifaceted approach. First, it’s crucial to assess the breadth and diversity of experiments conducted. Do they adequately cover the scope of the paper’s claims? Next, examining the methodology is essential: Are the datasets sufficiently varied and large? Are the baselines properly selected and described, providing a robust comparison? The statistical significance of reported results needs careful scrutiny. Are error bars or confidence intervals presented? Are the chosen metrics appropriate for evaluating the task? The reproducibility of results should be considered: is sufficient detail provided about experimental setup to allow replication? Finally, it is important to consider the interpretability and implications of the findings. Are the results clearly presented and easily understood? Do they offer meaningful insights that advance the state of the art?

Limitations & Future#

A research paper’s “Limitations & Future” section requires a nuanced approach. Limitations should honestly address shortcomings, such as the model’s dependence on specific data distributions, assumptions made during model development (like linearity or stationarity), or computational constraints hindering scalability to massive datasets. The discussion should also acknowledge potential biases and the impact on different demographic groups or applications. Future work should propose concrete and impactful extensions, like exploring alternative architectures to address identified limitations or adapting the model for different data modalities. Addressing model interpretability or generalizability to less-structured or noisy data is also crucial, as is investigating broader societal impacts and ethical considerations that might arise from applying this research. The key is to balance acknowledging limitations without undermining the paper’s value; demonstrating awareness of the model’s scope and potential avenues for improvement strengthens the overall contribution.

Theoretical Analysis#

A Theoretical Analysis section in a research paper would ideally delve into the mathematical underpinnings and formal justifications for the proposed model or algorithm. It would not merely state results, but rigorously prove key claims. Proofs of theorems, demonstrating the model’s properties (e.g., convergence, complexity, expressiveness), would be central. The analysis would ideally cover the model’s ability to learn complex patterns, the effects of various design choices (hyperparameters, architecture), and how these choices influence the model’s capacity to meet the study’s objectives. Comparative analysis against existing models would provide valuable context, and this section would show how the new approach surpasses limitations of previous work. Crucially, any assumptions made in the theoretical derivations would be clearly stated, along with a discussion of their potential impact on the validity and generalizability of the results. The overall goal is to build strong confidence in the reliability and soundness of the method by providing a clear, compelling, and well-supported theoretical framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

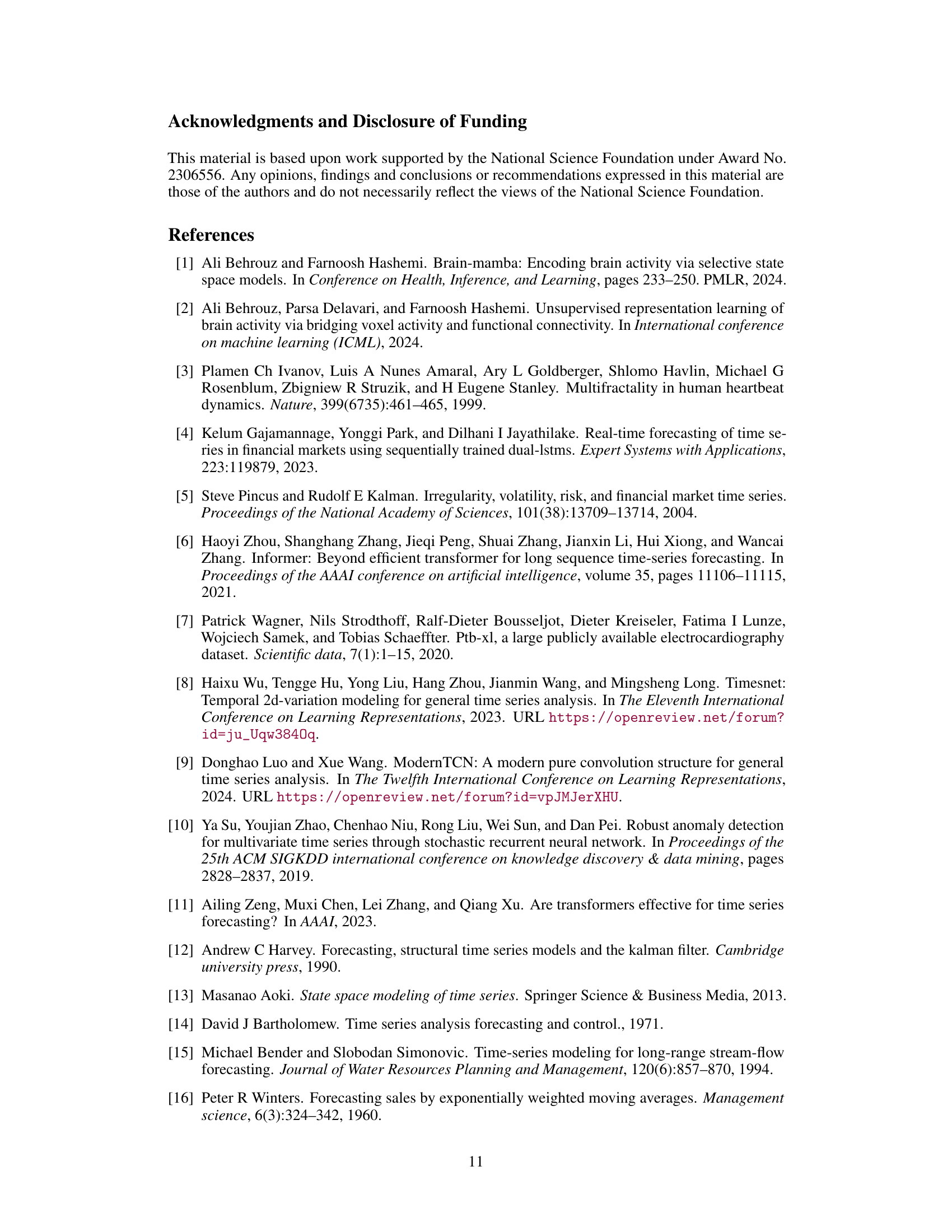

This figure provides a high-level overview of the Chimera model, a novel 2-dimensional state space model (SSM) for multivariate time series. The diagram showcases the key components: two SSM heads (one for seasonal and one for long-term patterns), learnable discretization processes to capture complex time dependencies, and the use of a parallel 2D scan for efficient training. It highlights Chimera’s ability to model seasonal and long-term patterns simultaneously while leveraging an efficient training process.

This figure illustrates three different perspectives of the Chimera model: a recurrence form showing the bi-directional flow of information along the variate axis, which can be efficiently computed as a convolution; a closed-loop architecture for multivariate forecasting which handles long time horizons; and a parallel 2D scan implementation enabled by data-dependent parameters for efficient training.

This figure demonstrates how the training time of different models scales with the length of the input time series. It shows that Chimera (using the 2D parallel scan method) scales linearly with sequence length, significantly outperforming other models like Transformer, S4, LSTM, and SpaceTime. The near-linear scaling of Chimera highlights the efficiency of its algorithm. The figure is used to support the claim that Chimera is efficient even for very long sequences.

This figure illustrates three different perspectives of the Chimera model. The top-left panel shows the model’s architecture, highlighting its bi-directional recurrence along variates, which can be efficiently computed as a global convolution during training. The top-right panel depicts the multivariate closed-loop used for forecasting, designed to improve long-horizon prediction accuracy. Finally, the bottom panel illustrates how the training process can be parallelized using a 2D scan when employing data-dependent parameters.

This figure illustrates different aspects of the Chimera model. The top-left panel shows the model’s recurrent structure, highlighting its bi-directional processing of variates and its equivalence to a global convolution during training for efficiency. The top-right panel depicts the multivariate closed-loop architecture used in forecasting, enabling improved long-horizon predictions. The bottom panel demonstrates how data-dependent parameters allow for efficient parallel 2D scanning during Chimera’s training process.

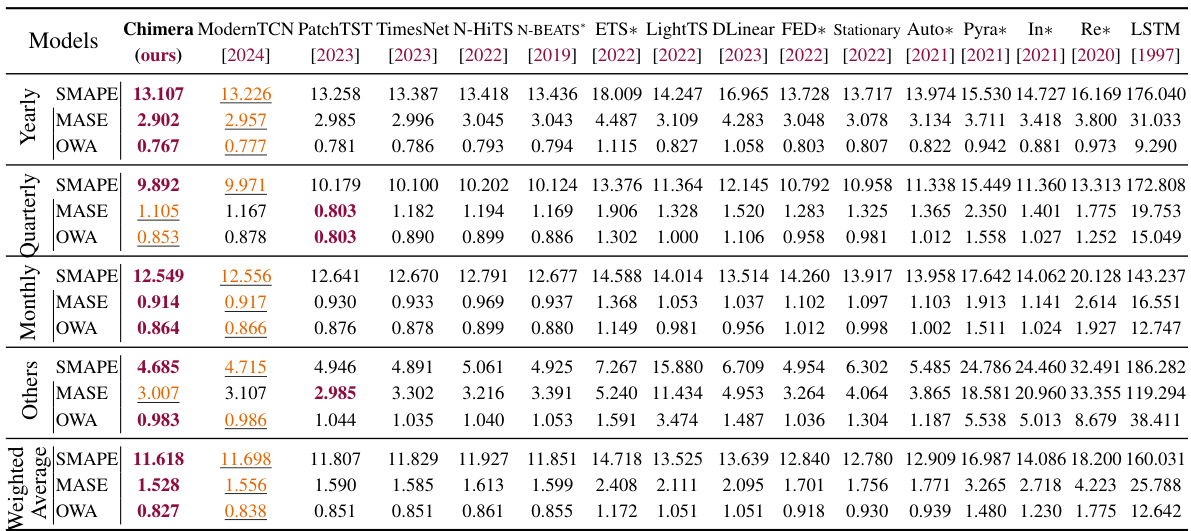

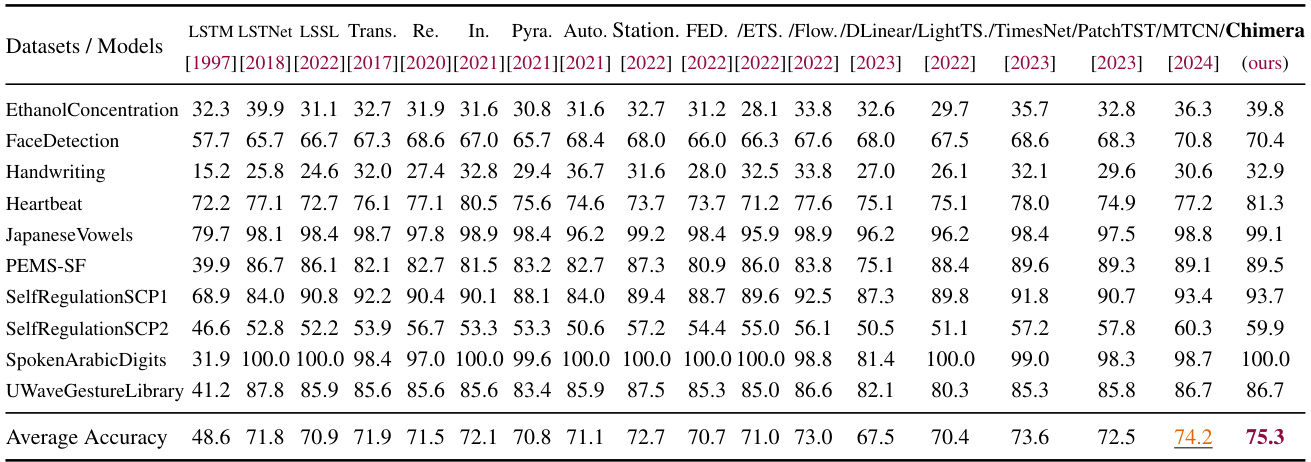

More on tables

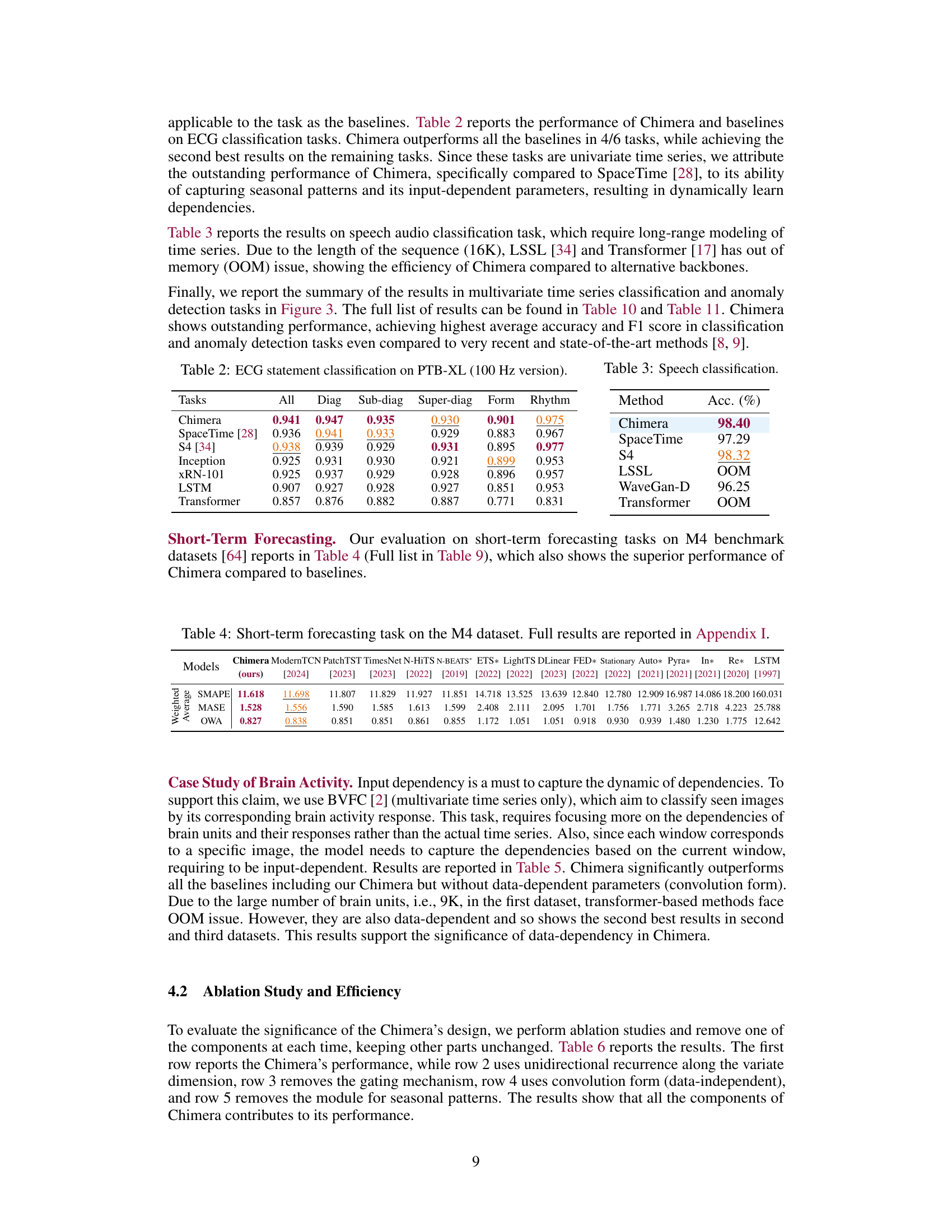

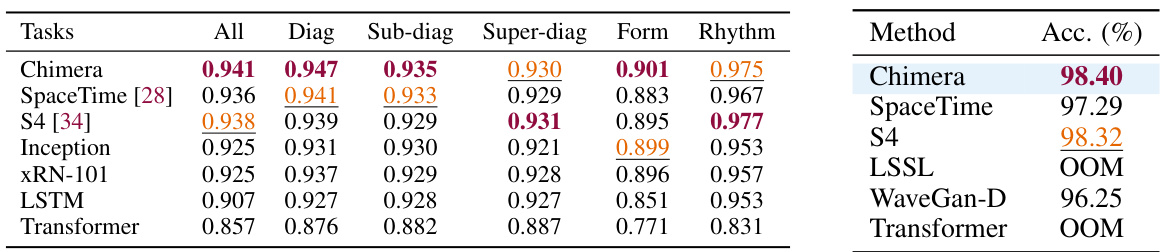

This table presents the performance of Chimera and several baseline methods on the ECG classification task using the PTB-XL dataset (100 Hz version). The results are broken down by different ECG statement categories: All, Diag, Sub-diag, Super-diag, Form, and Rhythm. The table shows that Chimera achieves state-of-the-art performance on most categories, highlighting its effectiveness in ECG classification.

This table presents a comparison of the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) achieved by Chimera and other state-of-the-art models on eight different long-term time series forecasting benchmark datasets. The best two performing models for each dataset are highlighted to emphasize Chimera’s competitive performance. The full results, including those for additional evaluation metrics, are available in Appendix I of the paper.

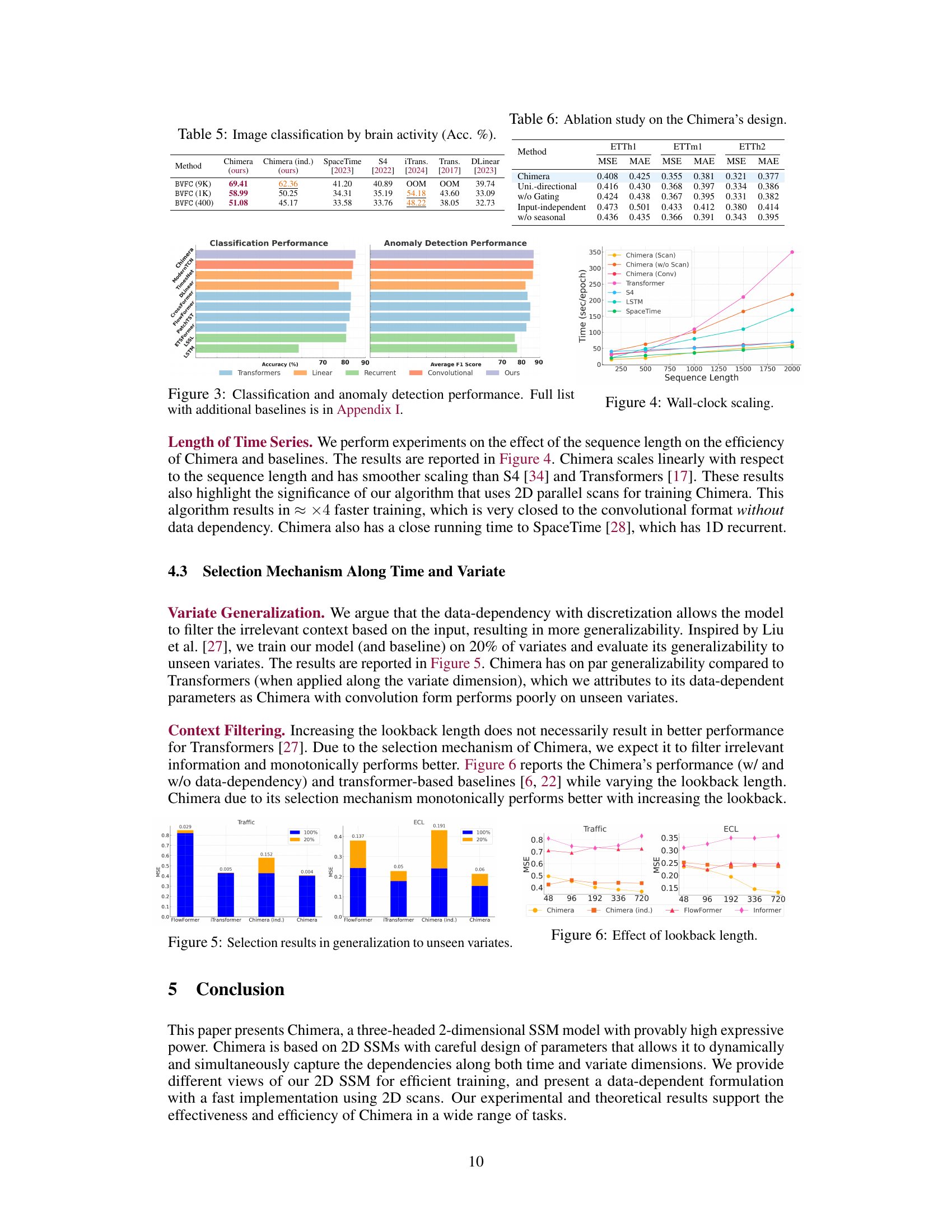

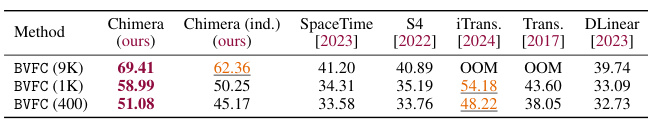

This table presents the results of image classification using brain activity data. It compares the performance of Chimera (with and without input-dependent parameters) against several baseline models (SpaceTime, S4, iTransformer, Transformer, and DLinear) on three different datasets of varying sizes (BVFC with 9K, 1K, and 400 brain units). The accuracy is reported for each model and dataset, highlighting the improvement achieved by Chimera, especially its data-dependent variant.

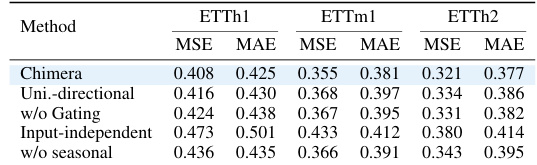

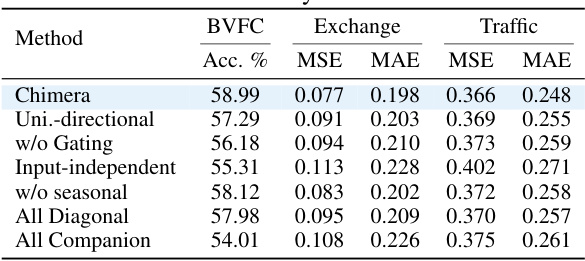

This ablation study evaluates the impact of each component of the Chimera model on its performance. The table shows the results for different variants of Chimera, each missing one component, on several metrics. By comparing the results, the table allows to assess the contribution of each component (e.g., bi-directionality, gating, etc.) to the overall performance of Chimera.

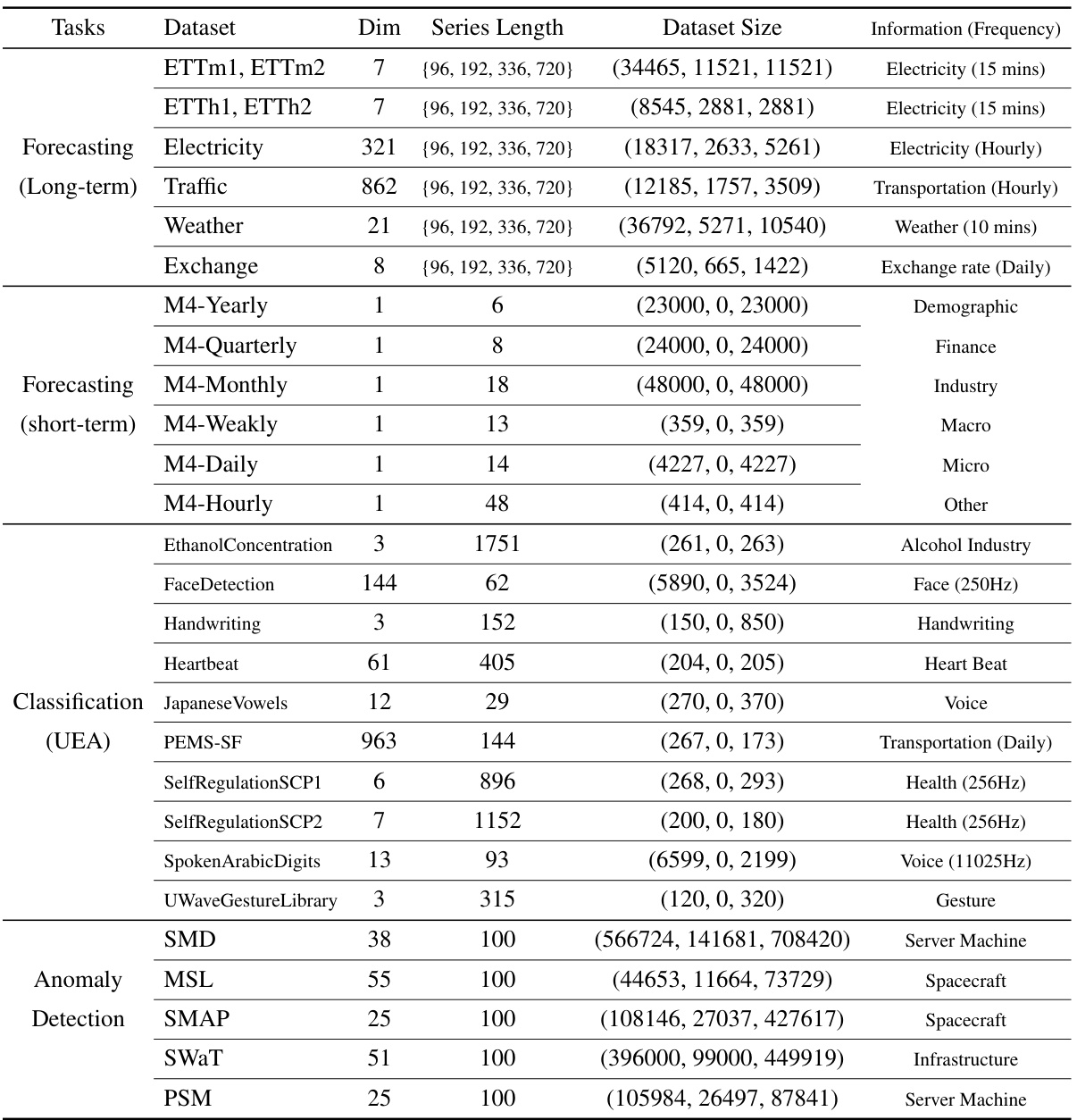

This table provides a comprehensive overview of the datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it lists the task (forecasting, classification, or anomaly detection), the dataset’s name, the dimensionality of the time series (Dim), the lengths of the time series (Series Length), the number of samples in the training, validation, and test sets (Dataset Size), and a brief description of the data’s characteristics (Information). The table allows readers to quickly grasp the scale and nature of each dataset used in evaluating the proposed Chimera model.

This table presents the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for various long-term forecasting models on eight different datasets. The models compared include Chimera (the proposed model) and several state-of-the-art baselines. The results are averaged across different forecasting horizons. The best and second-best results for each dataset are highlighted in the table for easy comparison.

This table presents the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for various long-term forecasting models across eight different datasets. The datasets represent diverse time series data, including electricity, traffic, weather, and financial data. The table compares Chimera’s performance against several state-of-the-art models. The best two performing models for each metric and dataset are highlighted. Complete results, including detailed error metrics for various forecasting horizons, are available in Appendix I.

This table presents the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) achieved by Chimera and several other state-of-the-art long-term forecasting models across eight benchmark datasets. The best-performing models in terms of MSE and MAE for each dataset are highlighted. The full results, including those for different forecasting horizons, are available in Appendix I.

This table presents the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for several long-term forecasting models on eight different benchmark datasets. The models are compared across four different time horizons (sequence lengths) for each dataset. The best and second-best results for each dataset and horizon are highlighted in red and orange, respectively. Detailed results are available in Appendix I of the paper.

This ablation study removes different components from Chimera and evaluates its performance on three datasets: BVFC, Exchange, and Traffic. The metrics used are accuracy (%) for BVFC and MSE and MAE for Exchange and Traffic. The results show the contribution of different components to Chimera’s performance.

Full paper#