↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Preference learning aims to infer human preferences from choices, but existing models often oversimplify human decision-making. This leads to inaccurate predictions and limits the applicability of these models to real-world scenarios, especially when dealing with complex tasks and context-dependent choices. Context effects, such as decoy effects where introducing an inferior option alters preferences, are commonly observed but not well-captured by existing models.

This paper introduces a novel tractable surrogate model, CRCS, based on a state-of-the-art cognitive model of human choice. This model accounts for contextual effects and other complexities in human decision-making. The researchers demonstrate that CRCS produces significantly better inferences compared to existing methods. Furthermore, they propose LC-CRCS, an extension that leverages the benefits of a complementary model to improve performance. These improvements were empirically validated using large-scale human data and simulations of real-world scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in preference learning and human decision-making. It bridges the gap between realistic cognitive models and tractable preference learning methods, offering a novel approach to inferring latent utilities from human choices. This work significantly improves the accuracy of preference learning and opens new avenues for research in AI systems that learn from human feedback, particularly in complex tasks involving multiple objectives and contextual effects.

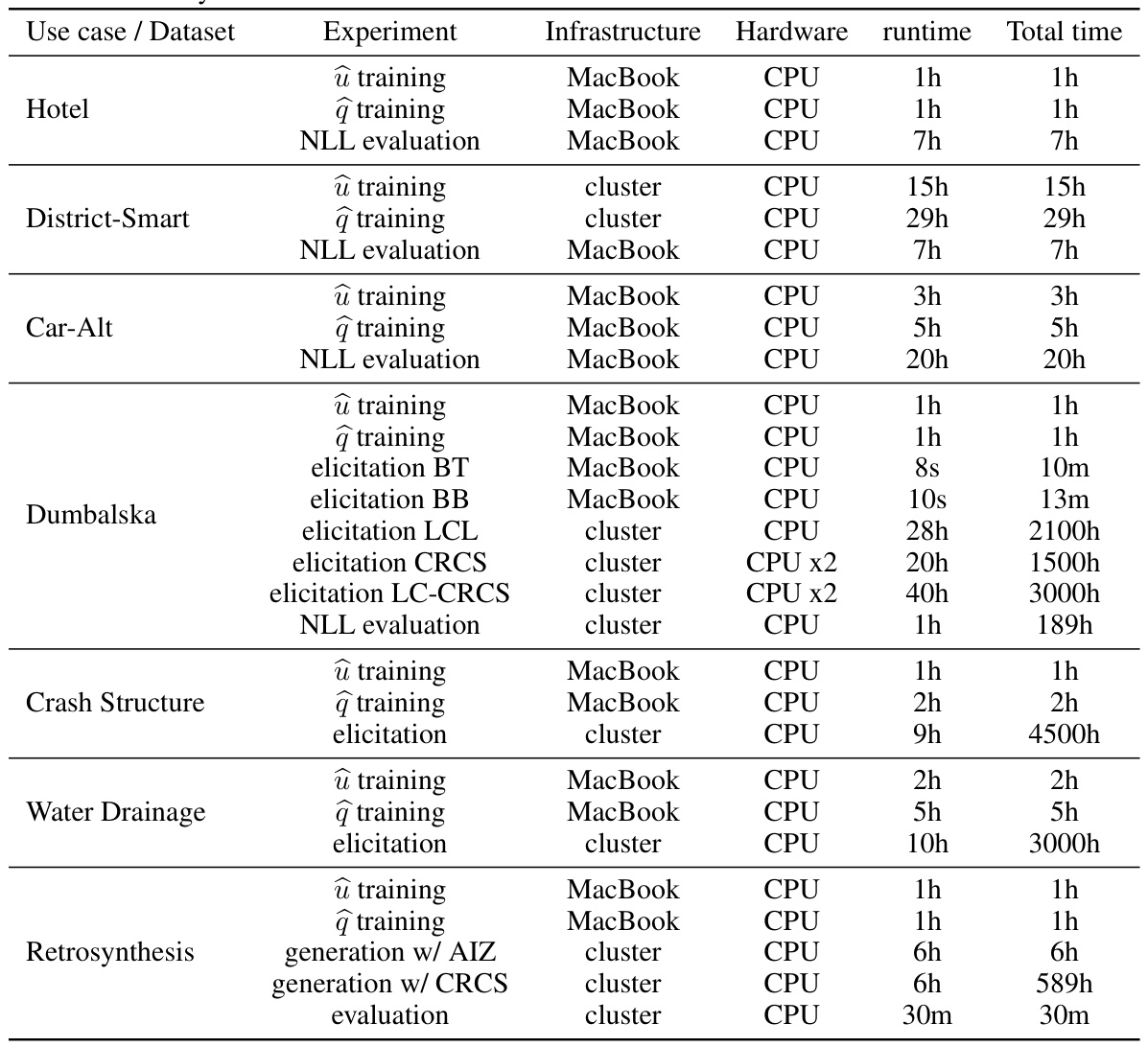

Visual Insights#

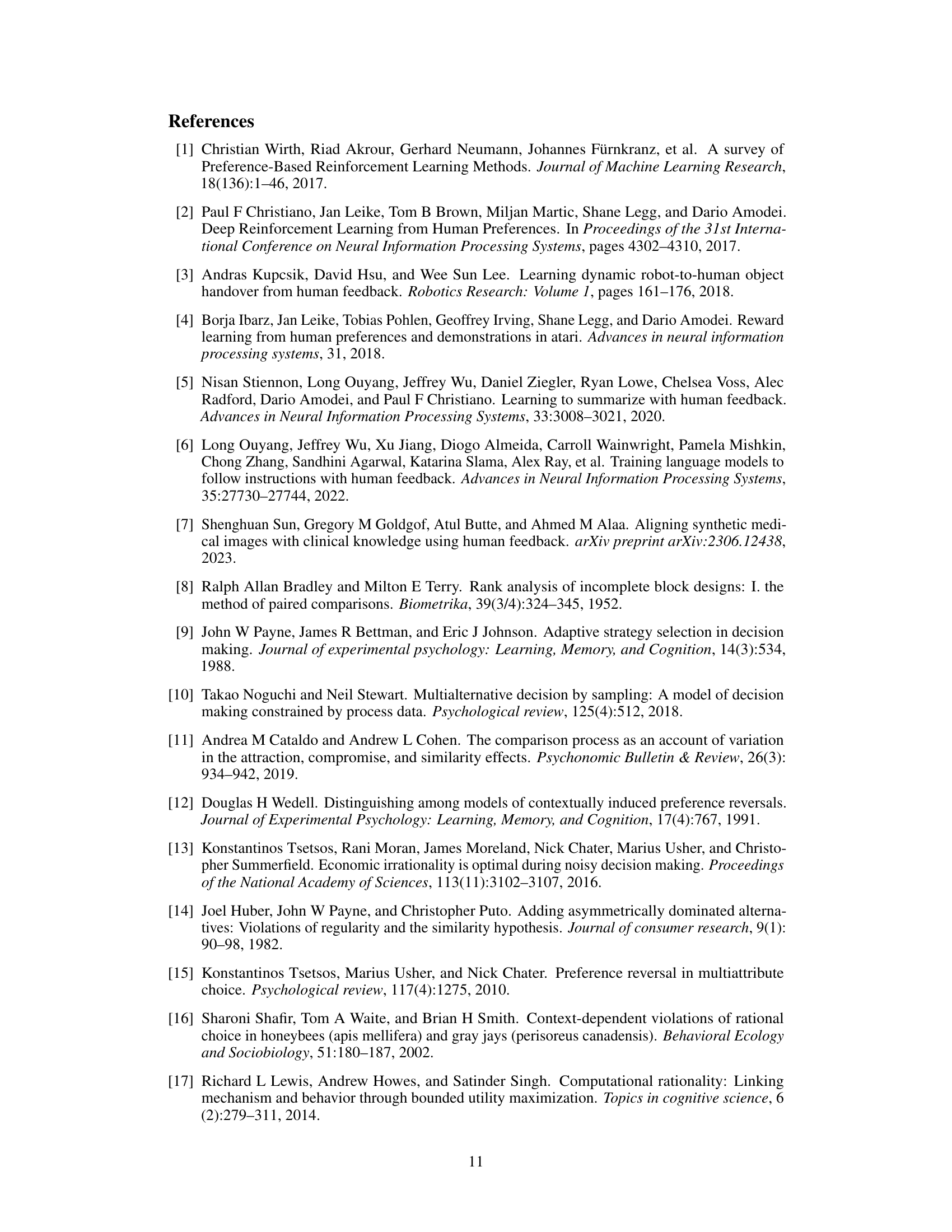

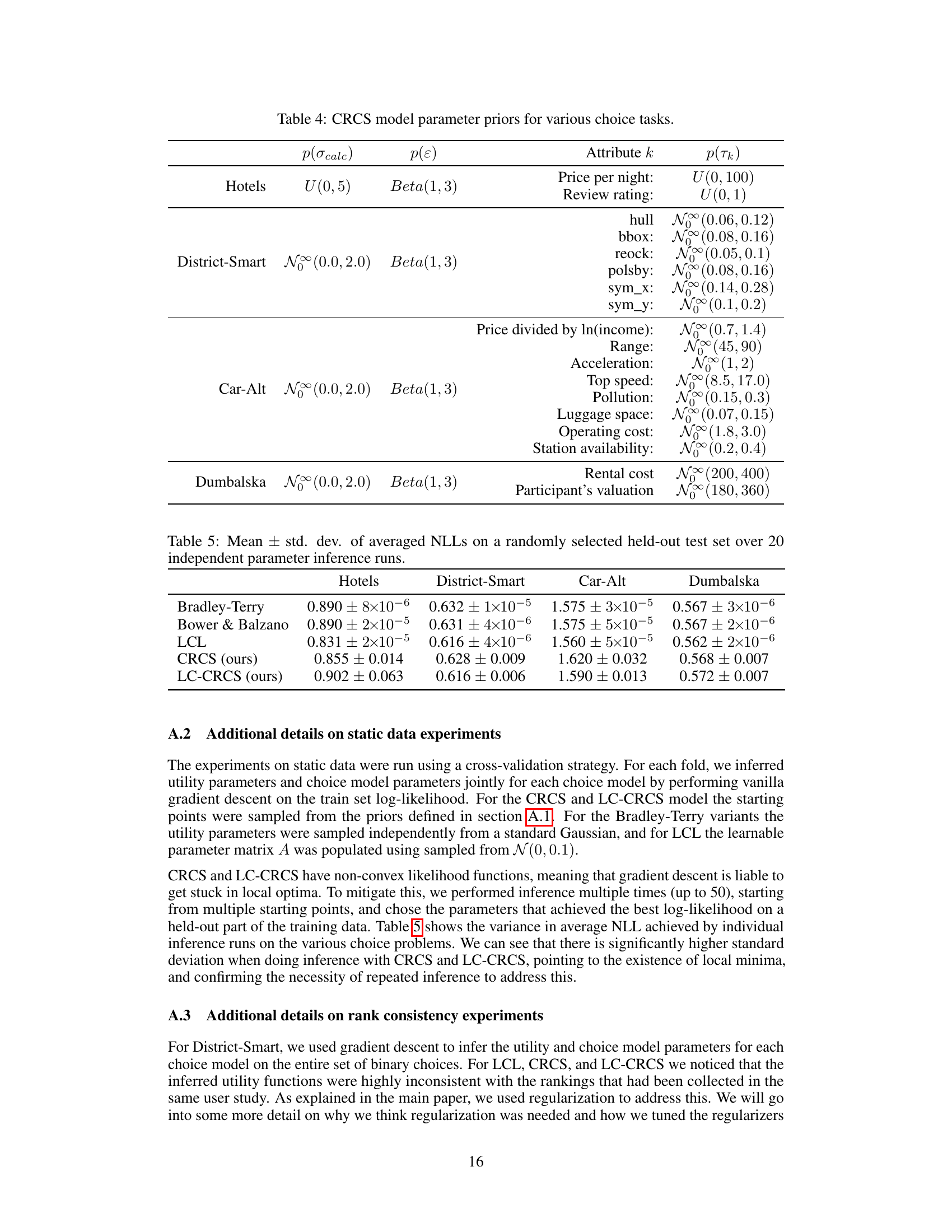

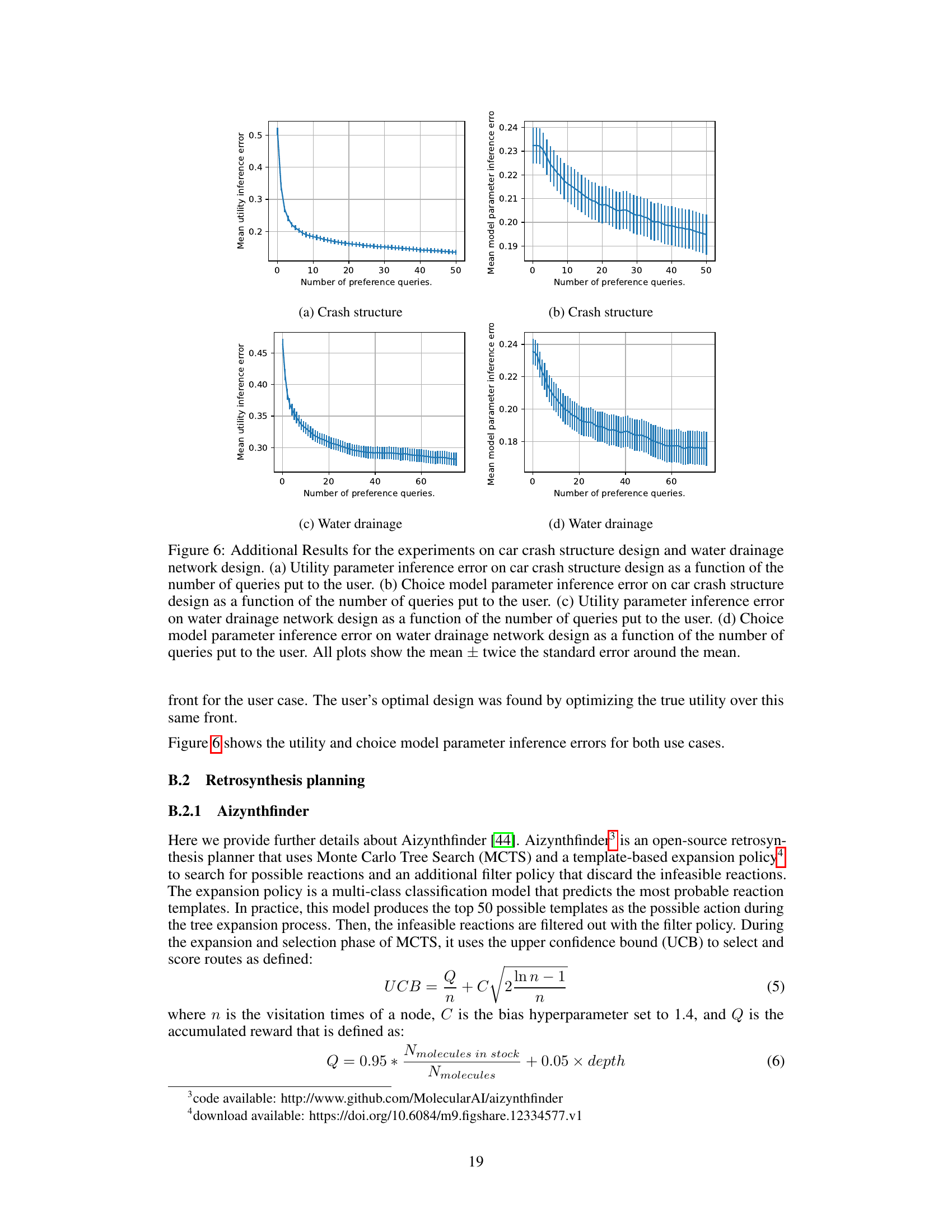

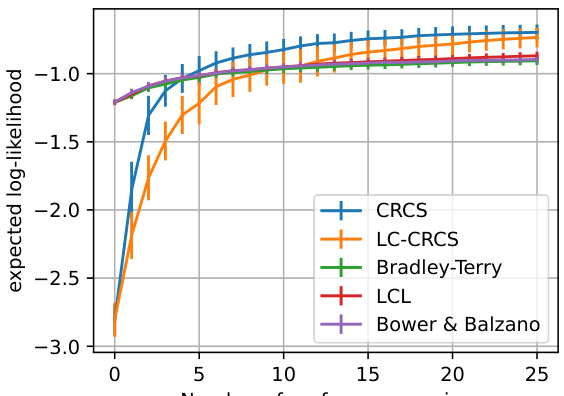

This figure presents the results of four different experiments. (a) shows the mean expected likelihood of unseen choice data as a function of the number of queries for various choice models in the Dumbalska elicitation task. (b) and (c) show the mean recommendation regret as a function of the number of queries for crash structure design and water drainage network design, respectively. (d) shows the maximum utility within the top k routes ranked by inferred utility as a function of k. Error bars represent twice the standard error.

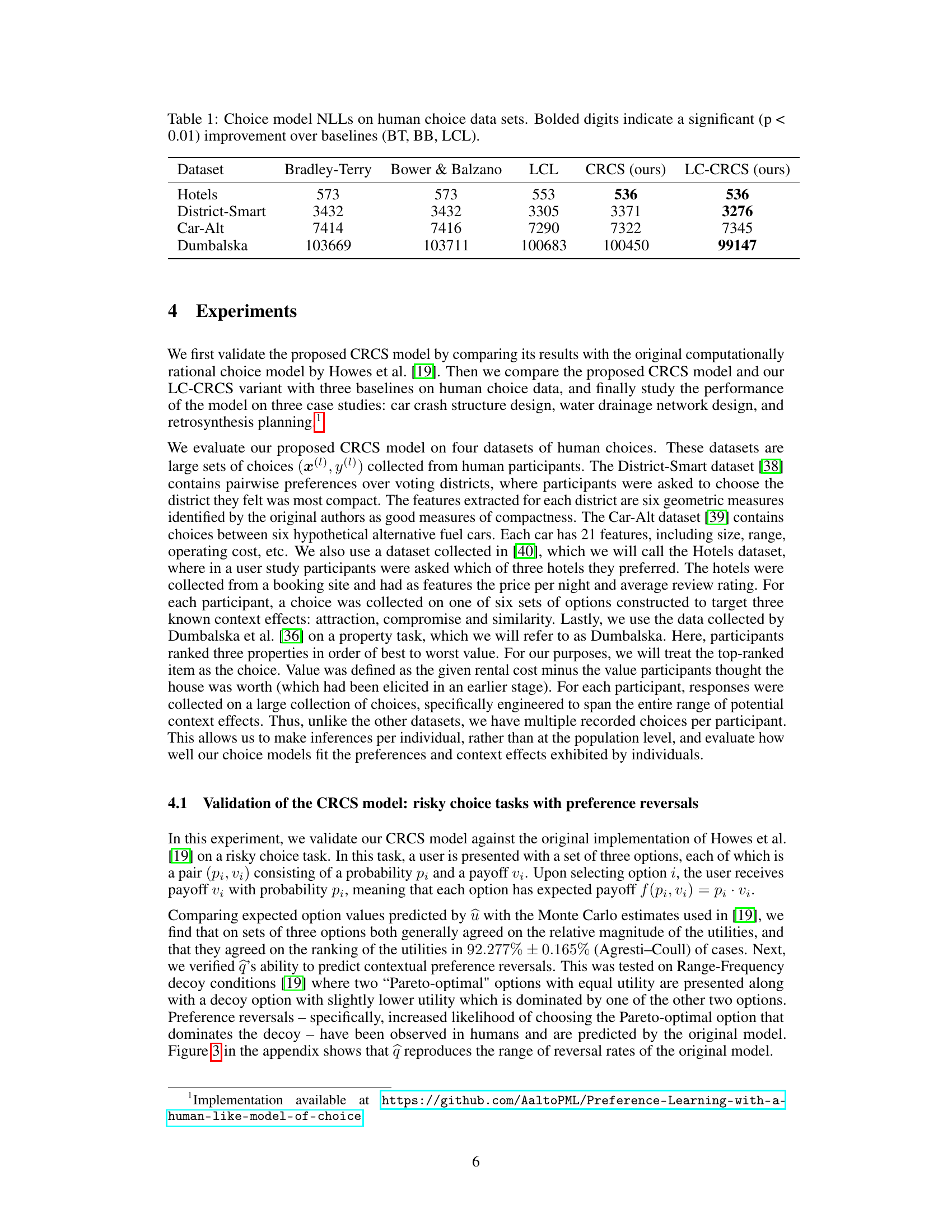

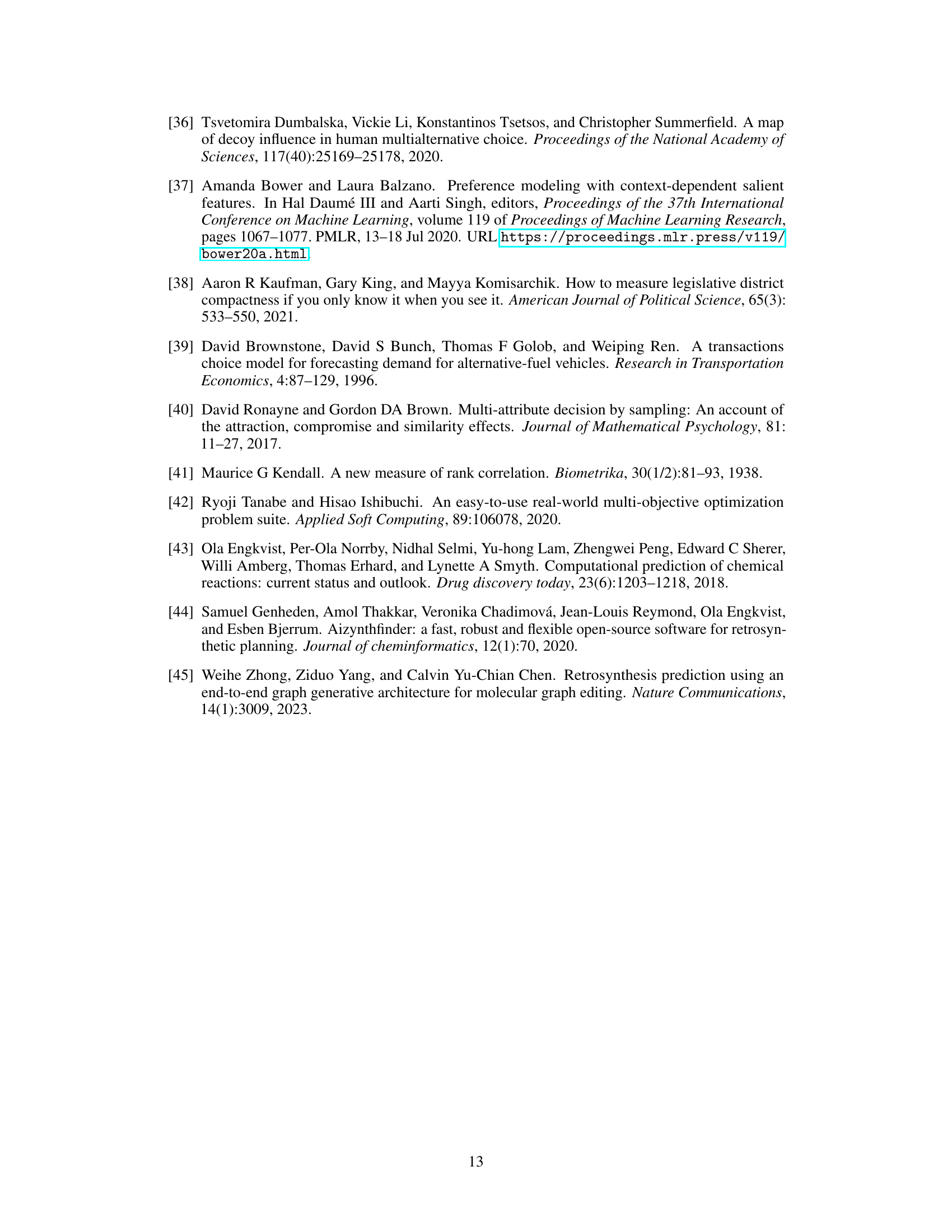

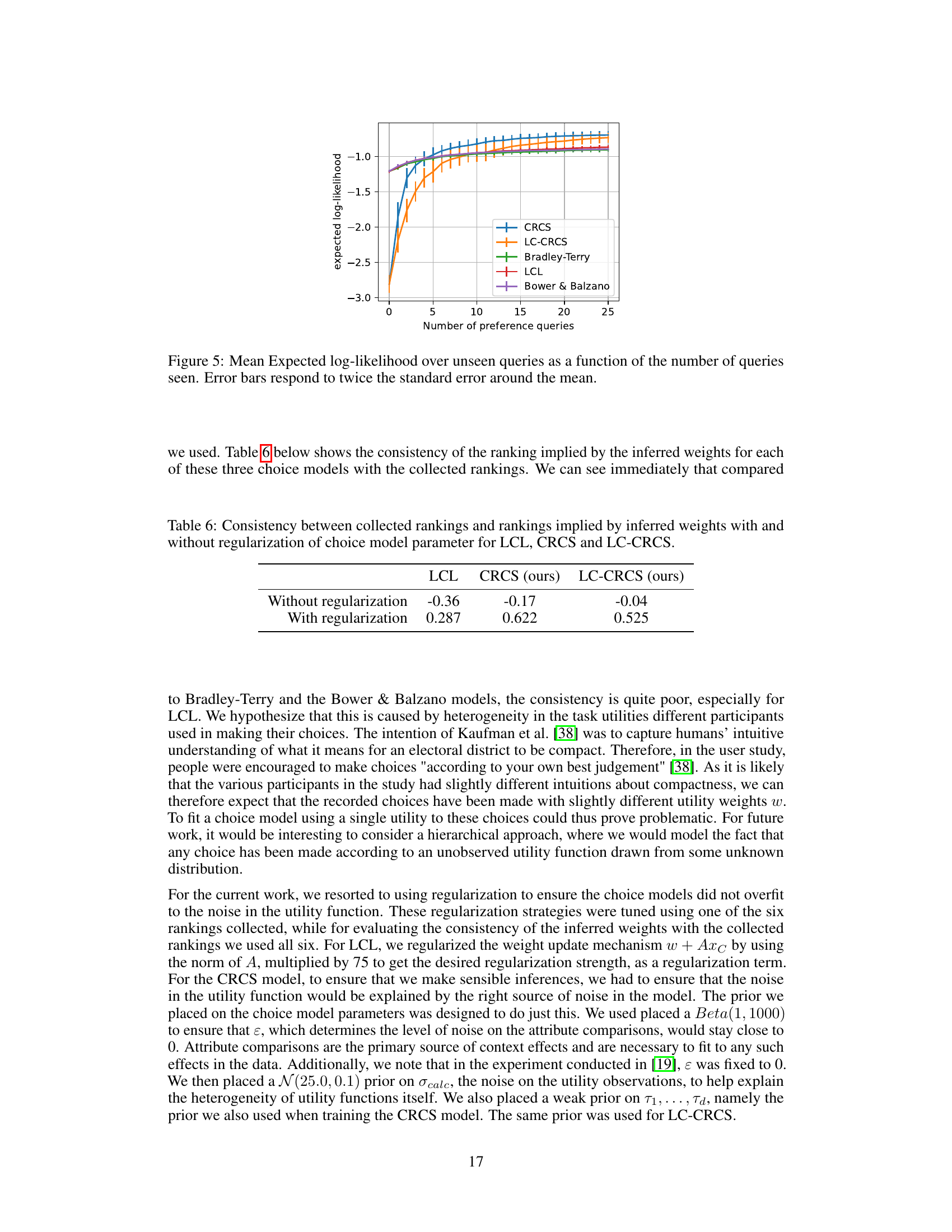

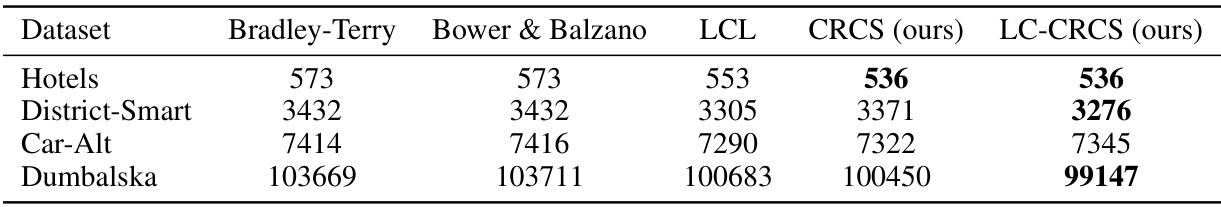

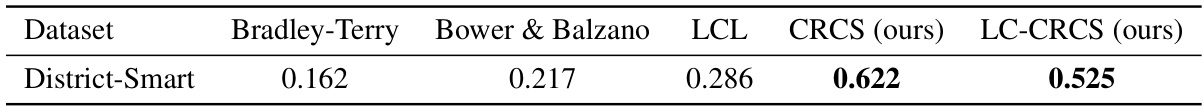

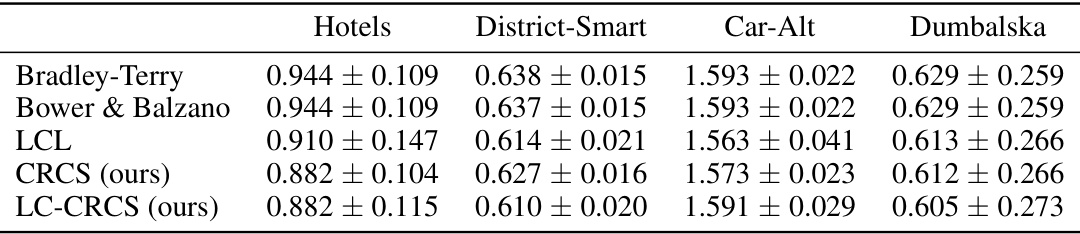

This table compares the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores of different choice models on four human choice datasets. The models compared are Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, LCL, CRCS, and LC-CRCS. Lower NLL scores indicate better model fit to the data. The table shows that CRCS and LC-CRCS models generally achieve lower NLL scores than the baseline models, indicating a better fit to the human choice data. The bolded numbers indicate statistically significant improvements (p<0.01) compared to the baseline models.

In-depth insights#

Latent Utility Inference#

Latent utility inference is a crucial aspect of preference learning, aiming to uncover the hidden preferences that drive human choices. The challenge lies in the indirect nature of the data: we observe choices, not the underlying utilities. The paper explores this challenge by proposing novel models that account for complex decision-making processes. Tractable surrogate models are introduced to address the computational hurdles of more realistic cognitive models, improving prediction accuracy and inference capabilities. A key contribution is the integration of computationally rational theory, capturing aspects of bounded rationality, and contextual effects, to better reflect real-world human decision-making. The paper shows that incorporating these elements leads to significant improvements over traditional Bradley-Terry model variants in various datasets and tasks, particularly in low-data scenarios. Active learning strategies enhance the practical utility of the models by efficiently querying users for preferences. This approach highlights the synergy between theoretical cognitive models and practical algorithms in creating systems that learn effectively from limited human feedback.

Context Effects Modeling#

Modeling context effects in choice is crucial for accurately reflecting human decision-making. Traditional models often assume independence between options, leading to inaccurate predictions when context influences preferences. However, cognitive models incorporate context effects, acknowledging that humans often compare options relative to each other and the surrounding choices. These models, while more accurate, can be computationally expensive. Therefore, the challenge is creating tractable approximations that capture the essence of context effects without sacrificing computational feasibility. This may involve simplifying cognitive models, using surrogate functions, or developing novel methods that leverage both psychological principles and machine learning techniques. Addressing this challenge is pivotal for developing preference learning systems that truly reflect and learn from human behaviour, potentially leading to more robust AI agents that align better with user preferences.

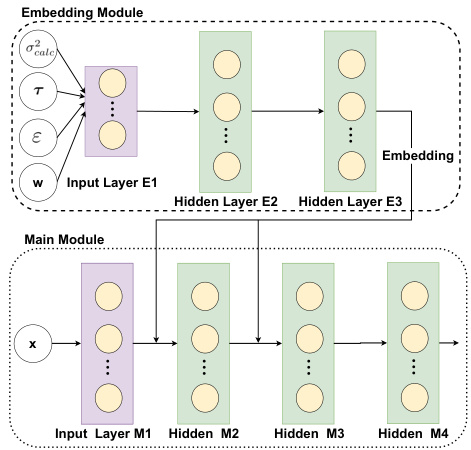

CRCS Model & Surrogates#

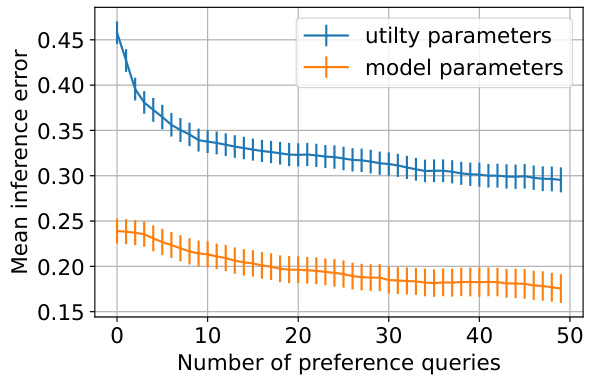

The core of this research paper revolves around creating a computationally tractable surrogate for a complex cognitive model of human choice. The authors introduce the Computationally Rational Choice Surrogate (CRCS) model as a solution to the intractability of existing models that accurately capture human decision-making nuances, including context effects. CRCS uses neural networks to approximate intractable calculations within the original model, making inference practical. This approximation allows for deployment within a preference learning framework. The model’s efficacy is demonstrated through large-scale human data experiments and simulations, highlighting its advantage over simpler models in both static and active data settings. A key contribution is the improvement in inference of latent utility functions, which are crucial for understanding human preferences and preferences learning applications. The paper also explores integrating cross-feature effects to enhance the model’s accuracy, leading to a refined LC-CRCS model.

Active Learning & Elicitation#

Active learning and elicitation are crucial for efficient preference learning, especially when dealing with complex, high-dimensional data or when obtaining human feedback. Active learning strategies intelligently select the most informative queries to maximize the information gained from each user interaction. This contrasts with passive approaches that simply use randomly selected or all available data. Elicitation methods focus on designing preference queries that are easy to understand and answer for users while providing rich information to the learning algorithm. Combining active learning with carefully designed elicitation techniques is key. This reduces the number of queries needed to obtain accurate preference models and improves user experience. The effectiveness of such a combined approach is highly dependent on the choice model used (e.g., Bradley-Terry vs. CRCS model discussed in the paper). The choice of a more sophisticated model capable of capturing context effects and human biases leads to better performance, especially when limited data is available, but adds computational complexity.

Real-World Applications#

The ‘Real-World Applications’ section of a research paper would ideally showcase the practical impact and versatility of the presented methodology. It should move beyond simulated environments and demonstrate successful implementation in tangible scenarios. Specific use cases should be detailed, illustrating the method’s effectiveness in solving real-world problems. A critical aspect would involve quantifiable results—demonstrating improved efficiency, accuracy, or other key metrics compared to existing approaches. Furthermore, a discussion of any challenges encountered during real-world implementation, including limitations and unexpected outcomes, would strengthen the analysis. The section should also highlight the generalizability and scalability of the method. In short, a robust ‘Real-World Applications’ section needs to convincingly demonstrate the practical value and broader applicability of the research, making a clear connection between theoretical findings and tangible outcomes.

More visual insights#

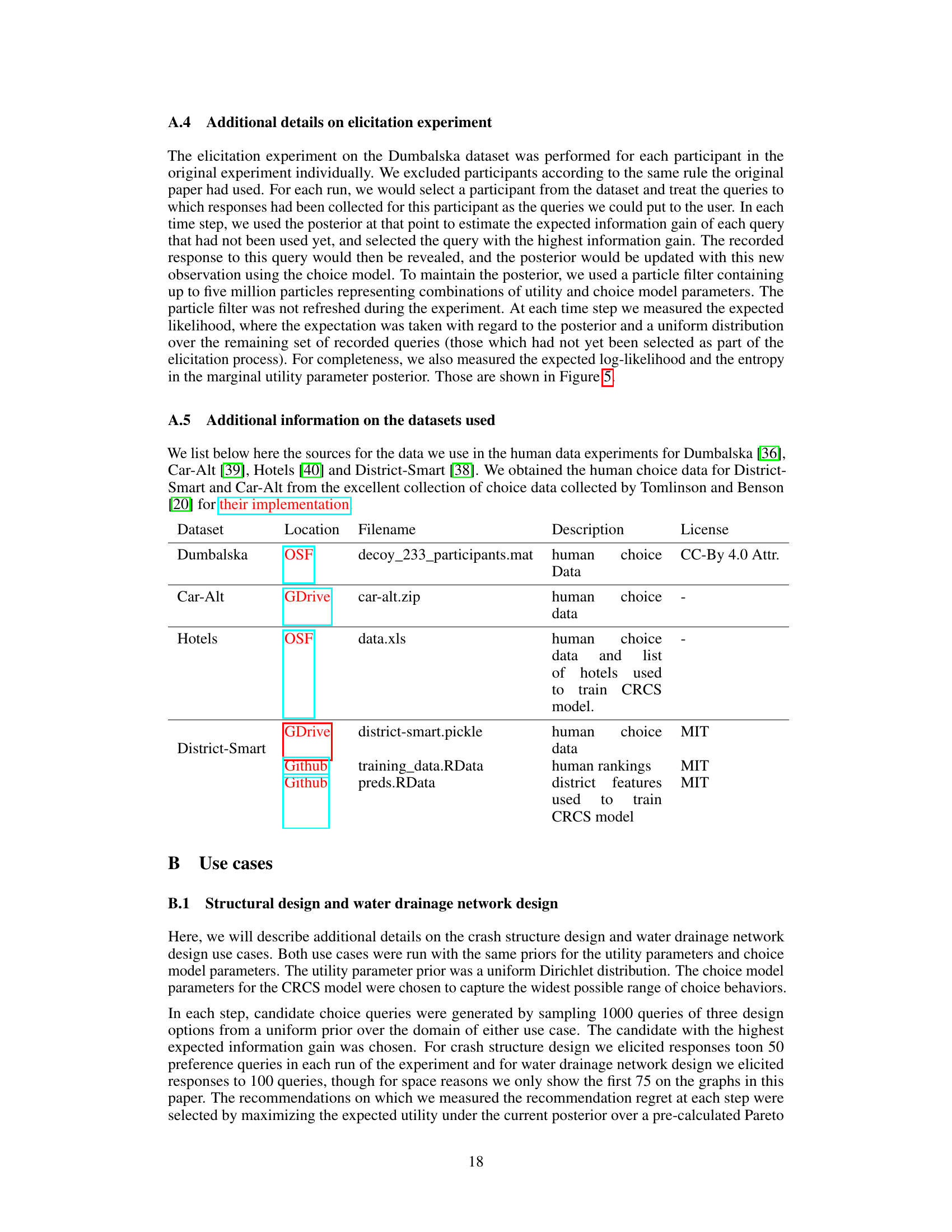

More on figures

The figure shows two graphical models. Model (a) illustrates the cognitive process underlying human choices, where individuals make decisions based on noisy observations of option utilities and attribute comparisons, rather than directly observing utilities. Model (b) depicts the preference learning problem, where an AI system aims to infer latent utilities from observed choices, treating the internal noisy observations as hidden variables.

The figure compares the reversal rate (the rate at which a user chooses the Pareto-optimal option that dominates the decoy) minus the inverse reversal rate (the rate at which the user chooses the other Pareto-optimal option) as a function of calculation noise standard deviation (σcalc) between the original model by Howes et al. [19] and the CRCS surrogate model. The CRCS model, despite being less sensitive to σcalc, successfully reproduces the range of reversal rates observed in the original model, validating its effectiveness.

This figure shows the empirical distribution of options in the Dumbalska dataset. Panel (a) displays the actual distribution of rental costs and participant valuations observed in the data, indicating a strong positive correlation between the two variables. Panel (b) shows the prior distribution p(xi) used to generate new sets of options for the experiment, showing a similar bivariate normal distribution designed to capture the correlation observed in the original data while providing sufficient support across the space of possible options.

This figure shows the results of four different experiments. (a) shows how well different models predict unseen choices in the Dumbalska dataset as the number of queries increases. (b) and (c) show how well different models recommend designs in crash structure and water drainage network design tasks as more user preferences are elicited. (d) shows how well different models rank retrosynthesis routes as the number of ranked options increases.

This figure presents the results of four different experiments. (a) shows the mean expected likelihood of unseen choices over time in the Dumbalska dataset for several models. (b) and (c) show the mean recommendation regret (difference between the optimal and recommended design) for crash structure design and water drainage network design, respectively. Finally, (d) illustrates the maximum utility achieved within the top k ranked routes (retrosynthesis task) as a function of k.

This figure shows the results of four experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of different choice models in different settings. Panel (a) shows the mean expected likelihood of unseen choices on the Dumbalska dataset as a function of the number of queries. Panels (b) and (c) show the mean recommendation regret for crash structure and water drainage design, respectively. Panel (d) shows the maximum utility within the top k routes, ranked by inferred utility, as a function of k for retrosynthesis planning. Error bars represent ± twice the standard error around the mean.

This figure shows two graphical models. (a) depicts the cognitive model for human choice behavior used in the paper. It shows how a human makes choices based on noisy observations of utilities (ũ) and ordinal relationships (õ) between option attributes. The true utilities (u) and options (x) are not directly observed. (b) shows the corresponding preference learning problem from the perspective of an AI system. The AI system observes choices (y) made over options (x) but does not observe the noisy observations (ũ, õ) used by the human. The goal is to infer the underlying utility function parameters (w) and choice model parameters (θ) from the observed data.

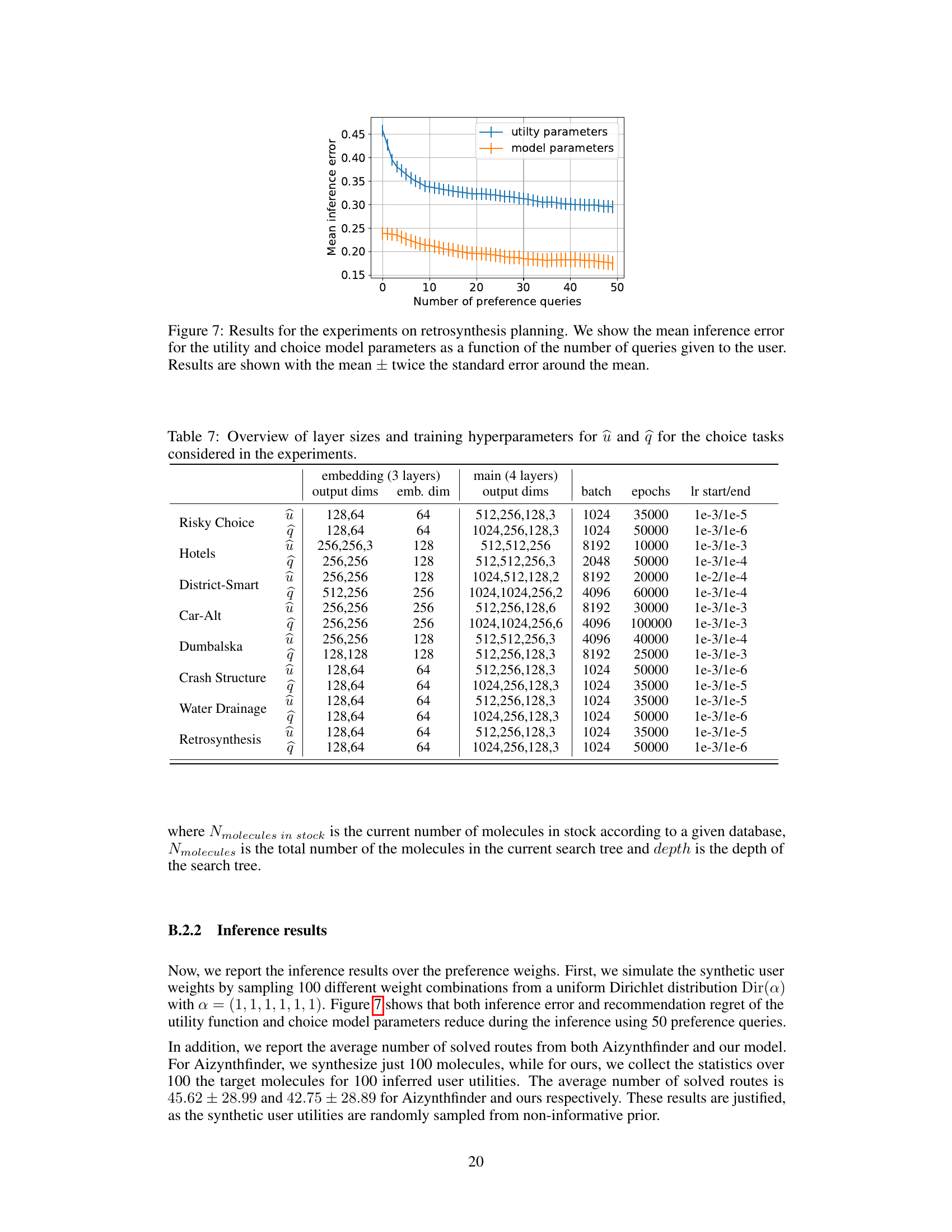

More on tables

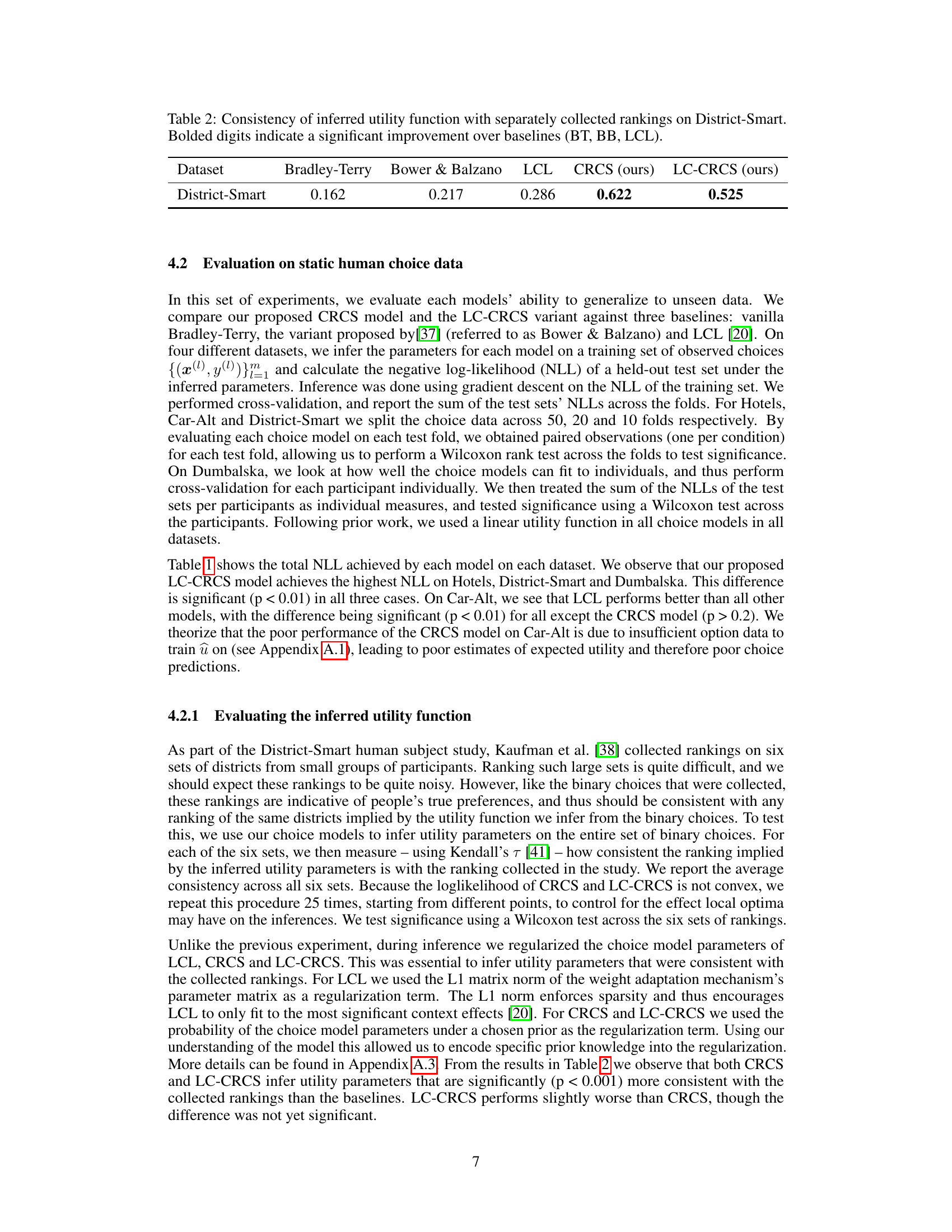

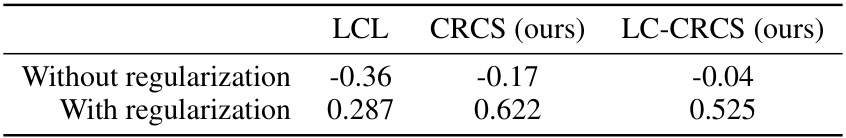

This table presents the consistency of utility functions inferred by five different choice models with separately collected rankings on the District-Smart dataset. The models are compared against baselines: Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, and LCL. The consistency is measured using Kendall’s tau, indicating how well the ranking implied by the inferred utility parameters aligns with the human-provided rankings. Bolded values highlight statistically significant improvements of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baselines.

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores achieved by different choice models on four human choice datasets. The models compared include Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, LCL, CRCS, and LC-CRCS. Lower NLL indicates better model fit. The table highlights statistically significant improvements (p<0.01) of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baseline models (Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, and LCL).

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores for four different choice models on four human choice datasets. The models compared are Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, LCL (Linear Context Logit), CRCS (Computationally Rational Choice Surrogate), and LC-CRCS (Linear Context + CRCS). Lower NLL indicates better model fit to the data. Bolded values highlight statistically significant improvements of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baselines.

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores for four different choice models on four human choice datasets. The models compared are Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, LCL, CRCS, and LC-CRCS. Lower NLL indicates better model fit to the data. The table highlights statistically significant improvements (p<0.01) achieved by CRCS and LC-CRCS compared to the baseline models (Bradley-Terry, Bower & Balzano, and LCL).

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores achieved by different choice models on four human choice datasets. The models compared are Bradley-Terry (BT), Bower & Balzano (BB), Linear Context Logit (LCL), the proposed CRCS model, and the LC-CRCS model. Lower NLL scores indicate better model fit. Bolded numbers highlight statistically significant improvements of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baselines.

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores achieved by different choice models on four distinct human choice datasets: Hotels, District-Smart, Car-Alt, and Dumbalska. The models compared are Bradley-Terry (BT), Bower & Balzano (BB), Linear Context Logit (LCL), the proposed Computationally Rational Choice Surrogate (CRCS), and the proposed LC-CRCS model. Lower NLL scores indicate better model fit to the data. Bolded values highlight statistically significant improvements (p<0.01) of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baselines.

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores achieved by different choice models on four distinct human choice datasets: Hotels, District-Smart, Car-Alt, and Dumbalska. The models compared include Bradley-Terry (BT), Bower & Balzano (BB), Linear Context Logit (LCL), Computationally Rational Choice Surrogate (CRCS), and LC-CRCS. Lower NLL scores indicate better model fit to the data. Bolded values highlight statistically significant improvements of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baselines.

This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) scores achieved by different choice models on four human choice datasets: Hotels, District-Smart, Car-Alt, and Dumbalska. The models compared are Bradley-Terry (BT), Bower & Balzano (BB), Linear Context Logit (LCL), the computationally rational choice surrogate (CRCS), and the combined LC-CRCS model. Lower NLL scores indicate better model fit to the data. Bolded values highlight statistically significant improvements of CRCS and LC-CRCS over the baselines.

Full paper#