TL;DR#

Current multi-modal LLMs often require extensive fine-tuning for audio tasks, limiting efficiency and applicability. Existing methods often focus on specific tasks and lack the ability to handle unseen audio tasks effectively; they also typically require large-scale datasets for training. This necessitates a more efficient approach that can leverage the in-context learning capabilities of LLMs.

The paper proposes UniAudio 1.5, which leverages a novel LLM-driven audio codec to efficiently bridge audio and text modalities. This allows frozen LLMs to perform diverse audio tasks (including speech emotion classification, audio classification, text-to-speech generation, and speech enhancement) with only a few examples, bypassing the need for extensive fine-tuning. The effectiveness of this approach is experimentally validated across various audio understanding and generation tasks, highlighting its potential in efficient few-shot cross-modal learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to few-shot audio task learning, enabling frozen LLMs to handle diverse audio tasks. This opens new avenues for research in multi-modal LLMs, reduces reliance on extensive fine-tuning, and offers potential for efficiency gains in audio applications.

Visual Insights#

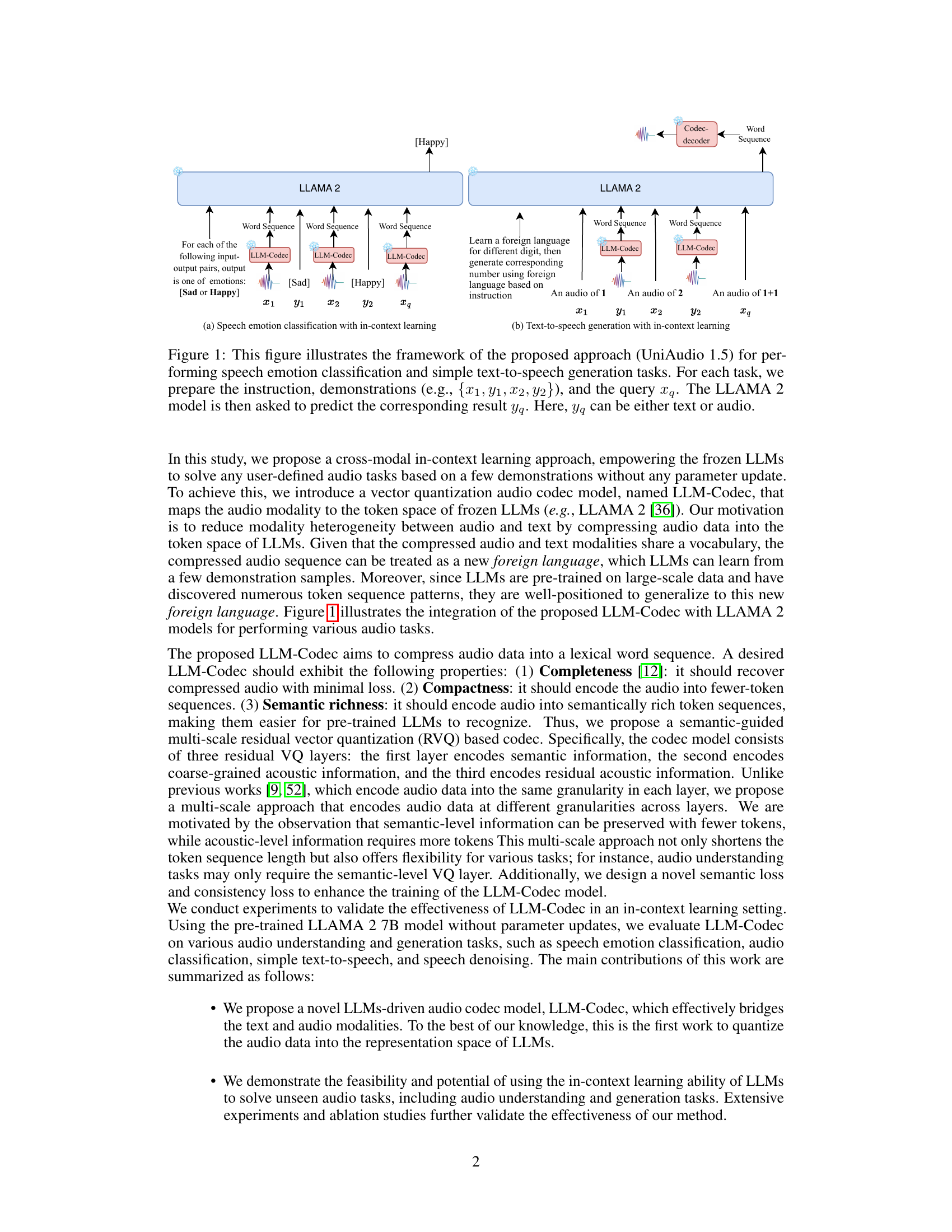

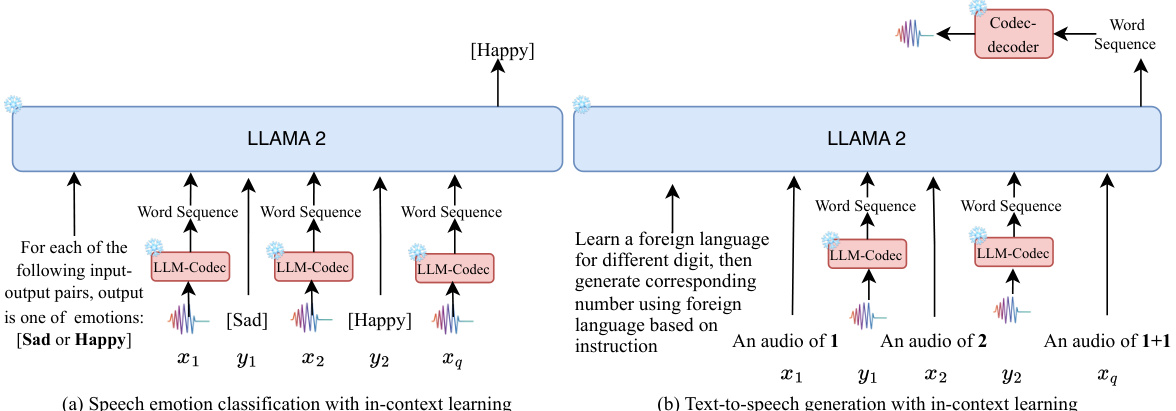

🔼 This figure shows how UniAudio 1.5, which uses LLAMA 2 and the proposed LLM-Codec, performs two tasks: speech emotion classification and text-to-speech generation. It highlights the in-context learning process; the model is given example input-output pairs (demonstrations) and a query, allowing it to predict the output without further training. The LLM-Codec is key to bridging the audio and text modalities, converting audio into a textual representation usable by LLAMA 2.

read the caption

Figure 1: This figure illustrates the framework of the proposed approach (UniAudio 1.5) for performing speech emotion classification and simple text-to-speech generation tasks. For each task, we prepare the instruction, demonstrations (e.g., {x1, Y1, x2, y2}), and the query xq. The LLAMA 2 model is then asked to predict the corresponding result yq. Here, yq can be either text or audio.

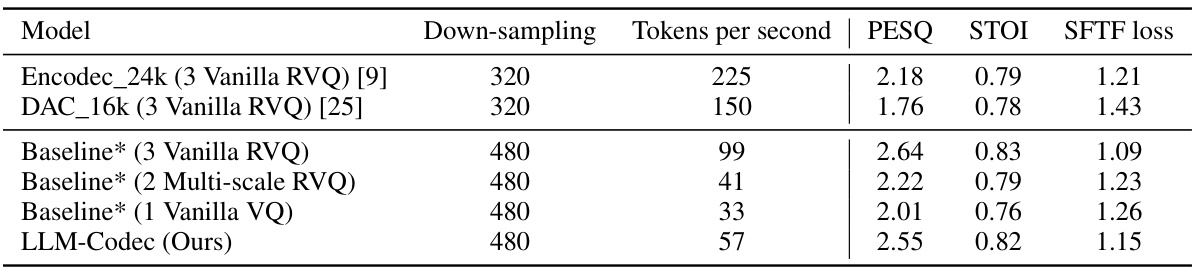

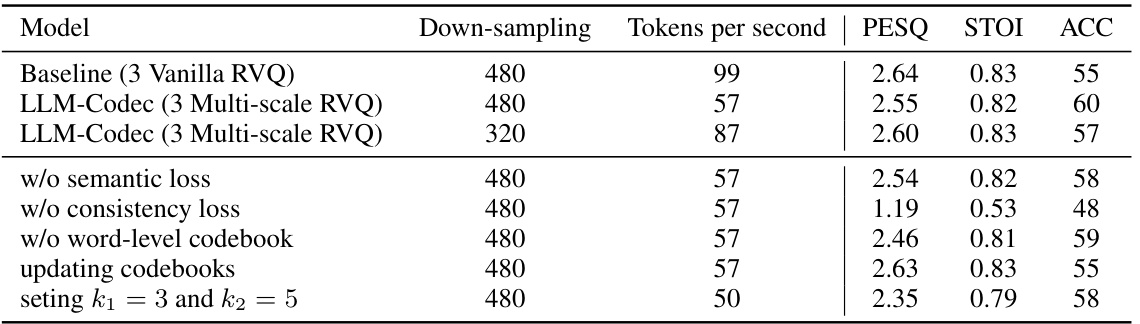

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed LLM-Codec model against several existing open-sourced audio codec models and baselines. The metrics used for comparison include tokens per second, PESQ, STOI, and SFTF loss. The baseline models use different configurations of vanilla and multi-scale residual vector quantization (RVQ). The results show that the LLM-Codec achieves competitive performance while significantly reducing the number of tokens needed.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison between open-sourced audio codec models, baselines, and the proposed LLM-Codec. * means the reproduced results by ourselves.

In-depth insights#

LLM-Codec Design#

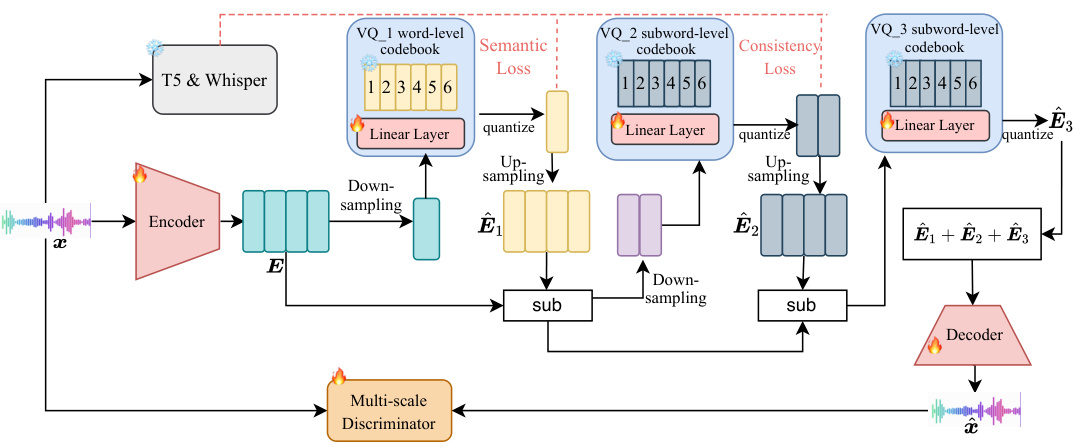

The LLM-Codec design is a novel approach to bridging the gap between audio and text modalities. It leverages vector quantization to efficiently compress audio data into a representation that can be directly understood by LLMs. The key innovation lies in the multi-scale residual vector quantization approach that compresses audio across different layers at varying granularities. This multi-scale approach intelligently balances the completeness of audio reconstruction with compactness of representation, crucial for effective few-shot learning. Further enhancing its capabilities, a semantic-guided approach ensures that the compressed audio tokens maintain semantic richness. This ensures better comprehension by the LLM, enabling superior performance in multiple audio tasks with minimal demonstration samples. Finally, the design incorporates semantic and consistency losses during training, improving the balance and stability of the overall model.

In-context Learning#

In-context learning (ICL) is a paradigm shift in machine learning, particularly impactful for large language models (LLMs). It leverages the model’s pre-trained knowledge to perform new tasks with only a few examples provided in the input prompt, avoiding explicit retraining or parameter updates. This ability to learn from context is crucial for enhancing the adaptability and efficiency of LLMs, making them more versatile. However, the effectiveness of ICL is highly dependent on the quality and relevance of the provided examples and the model’s architecture. Carefully chosen demonstrations are essential to guide the model’s inference towards the desired outcome. Moreover, research into ICL often focuses on achieving strong performance with minimal examples, pushing the boundaries of few-shot learning. Successfully applying ICL across diverse tasks and modalities, such as audio processing in this case, requires careful consideration of data representation and prompt engineering. Further research must explore the limitations of ICL, such as its sensitivity to noisy or irrelevant examples, and address the scalability challenges associated with handling increasingly complex tasks.

Multimodal RVQ#

Multimodal RVQ, or Multimodal Residual Vector Quantization, presents a powerful technique for encoding diverse data modalities into a shared, compressed representation. Its strength lies in the ability to handle heterogeneous data types (audio, text, images, etc.) effectively, bridging the semantic gap between modalities. The residual aspect is crucial, as it enables the model to learn finer-grained details progressively, improving the overall reconstruction quality. By incorporating a vector quantization layer, dimensionality reduction is achieved, making it computationally feasible to work with high-dimensional data. However, designing an effective multimodal RVQ architecture requires careful consideration of several factors: the choice of codebooks, the number of quantization layers, and the design of the loss function are critical to achieving both compression and maintaining semantic information. Furthermore, the efficacy of multimodal RVQ is tightly linked to the specific application. Its success depends on the ability to learn relevant cross-modal representations that capture meaningful relationships between modalities. Further research should focus on developing strategies for adapting codebooks dynamically, exploring different loss functions that better preserve semantic information during compression and investigating the generalization capabilities of multimodal RVQ across various datasets and applications.

UniAudio 1.5#

UniAudio 1.5 represents a significant advancement in audio processing, leveraging the power of Large Language Models (LLMs) for few-shot learning across various audio tasks. Its core innovation lies in the LLM-Codec, a novel vector quantization model that bridges the gap between audio and textual modalities. By representing audio as a ’new foreign language’ understandable by LLMs, UniAudio 1.5 bypasses the need for extensive fine-tuning. This allows it to effectively handle diverse tasks like speech emotion classification and text-to-speech generation with only a few examples. The multi-scale residual vector quantization within the LLM-Codec ensures both high audio reconstruction quality and compact representation, making it efficient for LLM processing. The success of UniAudio 1.5 validates the potential of cross-modal in-context learning for audio applications, opening avenues for efficient and versatile audio AI systems.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for enhancing the proposed LLM-Codec and its applications. Extending the model to handle more complex audio tasks, such as real-time speech translation or high-fidelity music generation, would be a significant advancement. Further research is needed to investigate the impact of different LLM architectures on the model’s performance. This includes comparing results using different LLMs as well as evaluating scaling effects when using larger language models. Improving the stability and efficiency of the training process is also crucial. Exploring alternative loss functions or training techniques could optimize the LLM-Codec’s performance and reduce the computational burden. Finally, a more thorough investigation into the theoretical underpinnings of the proposed method is warranted. This includes further analysis of the semantic richness, the relationship between codebook size and audio quality, as well as a deeper understanding of how the model bridges the gap between audio and text modalities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

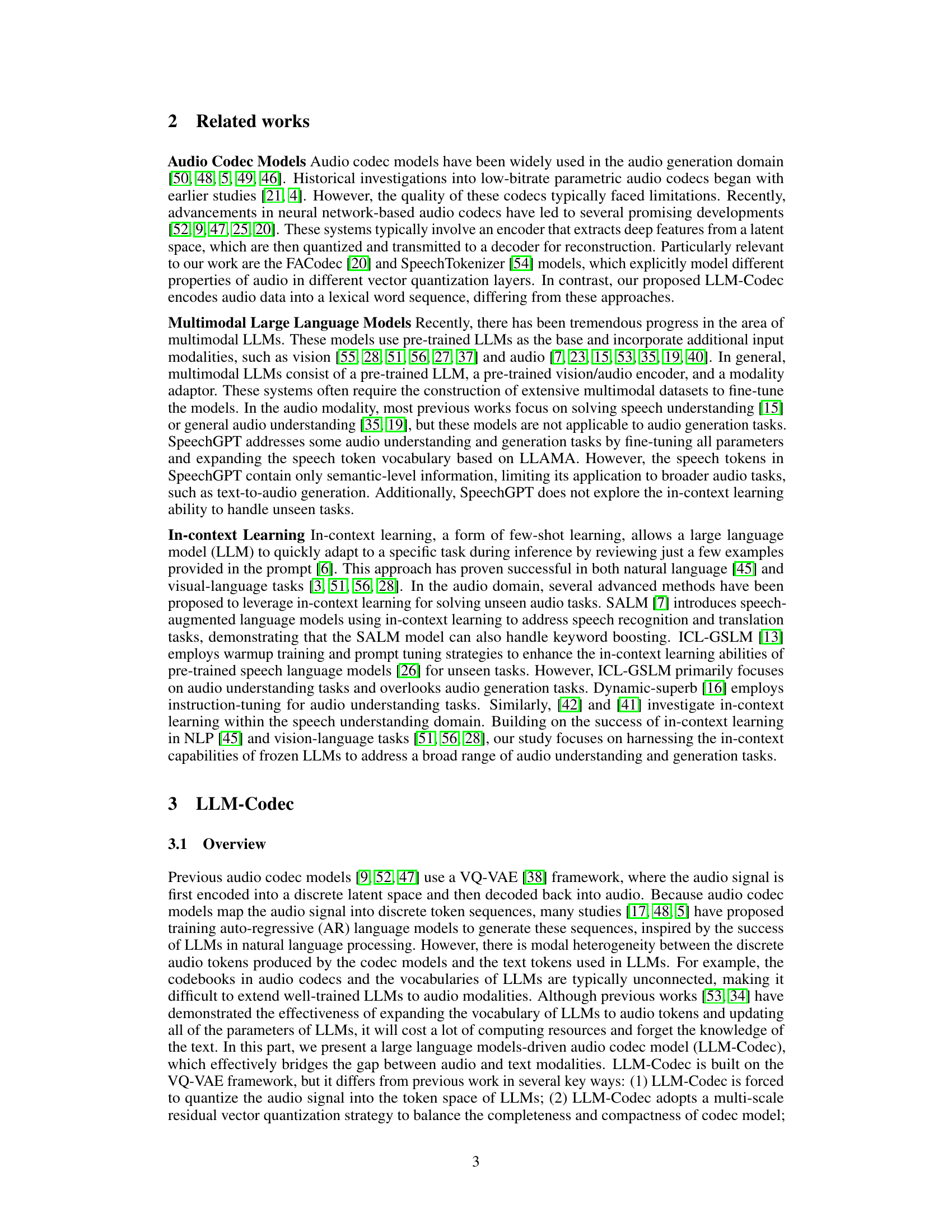

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the LLM-Codec model. The model consists of three main components: an encoder that converts the input audio signal into a latent representation, a multi-scale residual vector quantization (RVQ) module that quantizes the latent representation into a sequence of discrete tokens, and a decoder that reconstructs the audio signal from the quantized tokens. The RVQ module is composed of three layers, each with a different level of granularity. The first layer encodes semantic information, while the second and third layers encode acoustic information at different resolutions. The model also includes a multi-scale discriminator that helps to improve the quality of the reconstructed audio signal. Note that several components in the model, including the T5 and Whisper models, are frozen during training.

read the caption

Figure 2: This figure provides a high-level overview of LLM-Codec, including an encoder, a decoder, a multi-scale discriminator, and multi-scale residual VQ layers. Here, 'sub' denotes feature subtraction. Note that the modules marked with a snowflake are frozen during training.

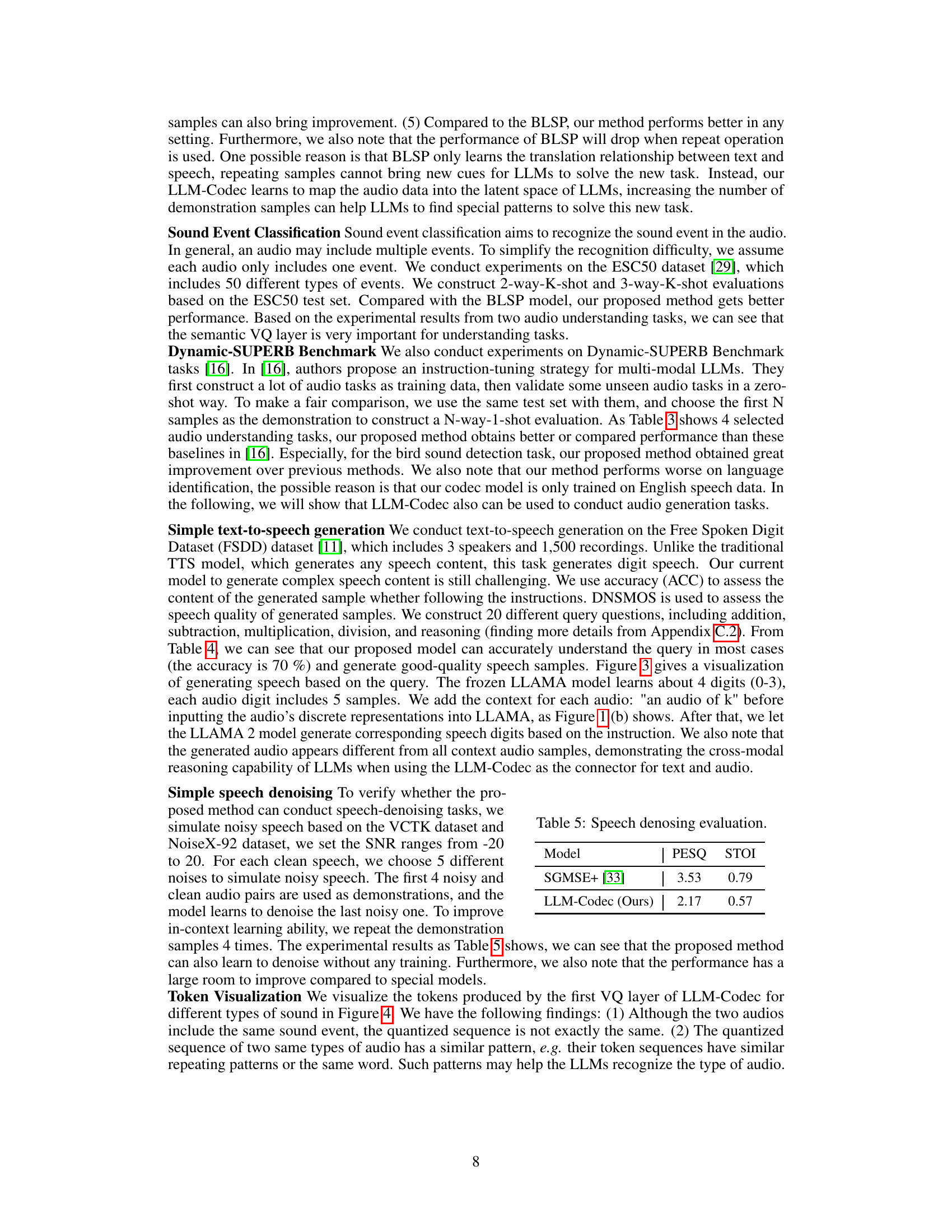

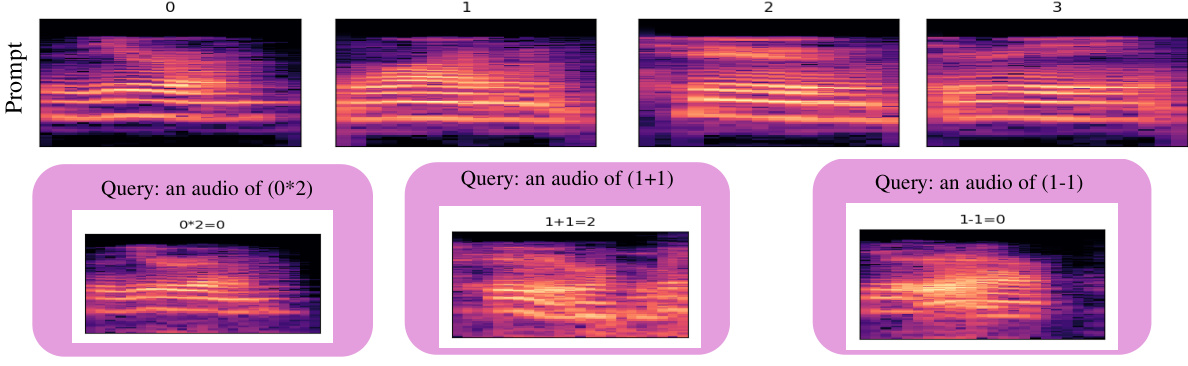

🔼 This figure shows three examples of simple text-to-speech generation using the LLM-Codec and LLAMA2 model. The top row displays mel-spectrograms of the audio prompts provided to the model. The prompts are simple mathematical equations (0*2, 1+1, and 1-1). The bottom row shows the mel-spectrograms of the audio generated by the model in response to these prompts, demonstrating the model’s ability to generate speech corresponding to the equation results.

read the caption

Figure 3: Examples of simple text-to-speech generation using LLM-Codec and LLAMA2 model.

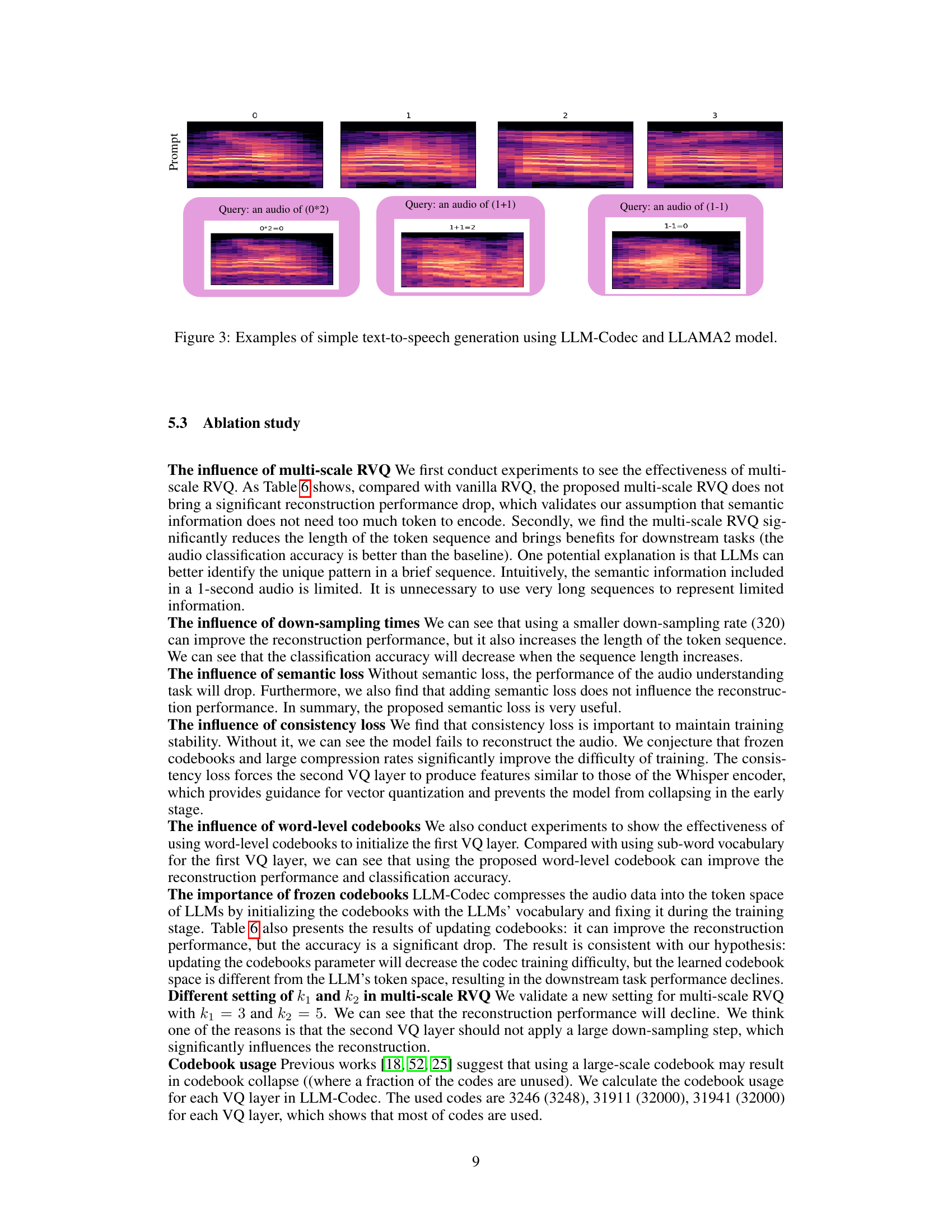

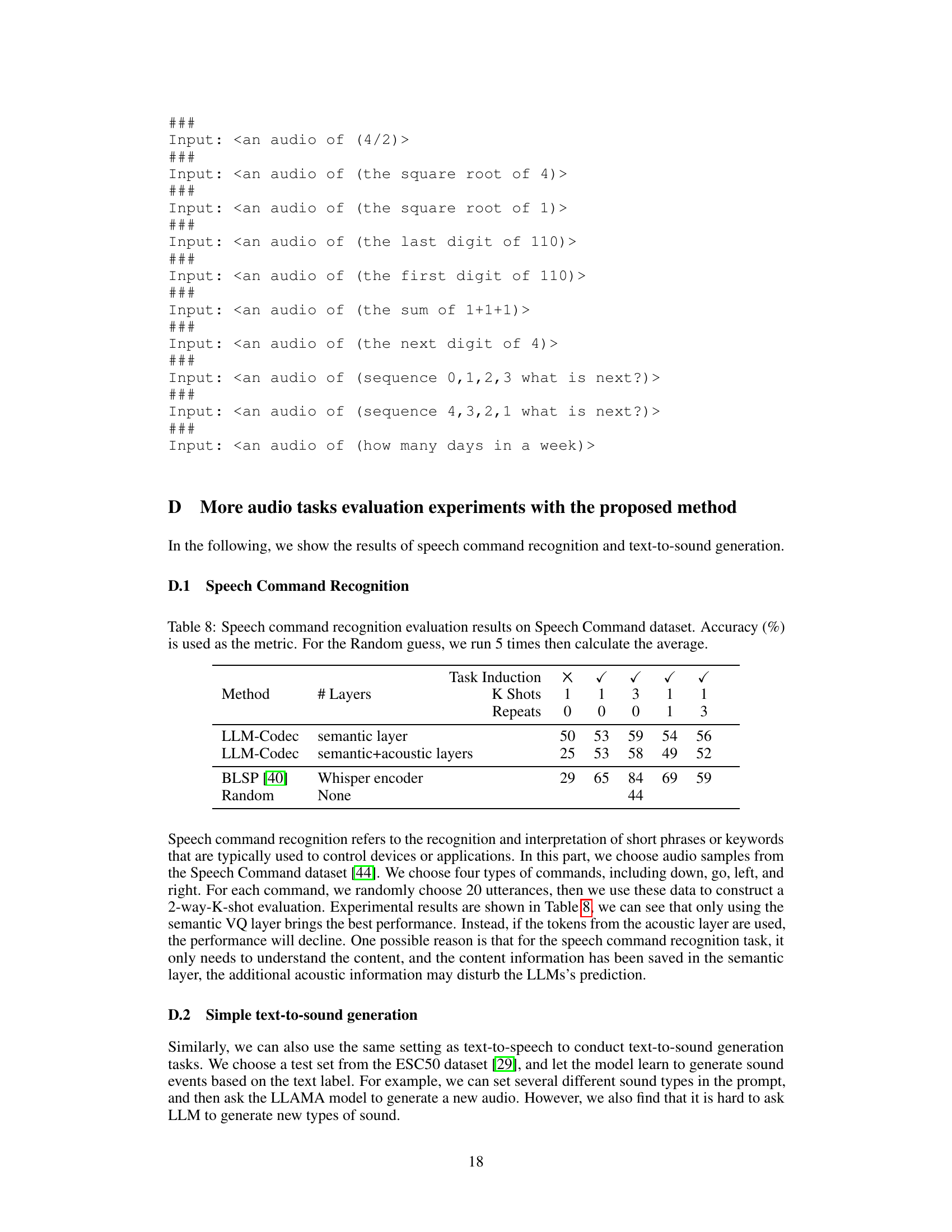

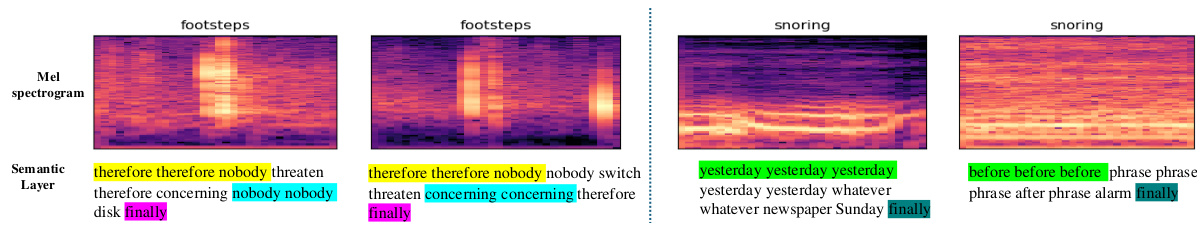

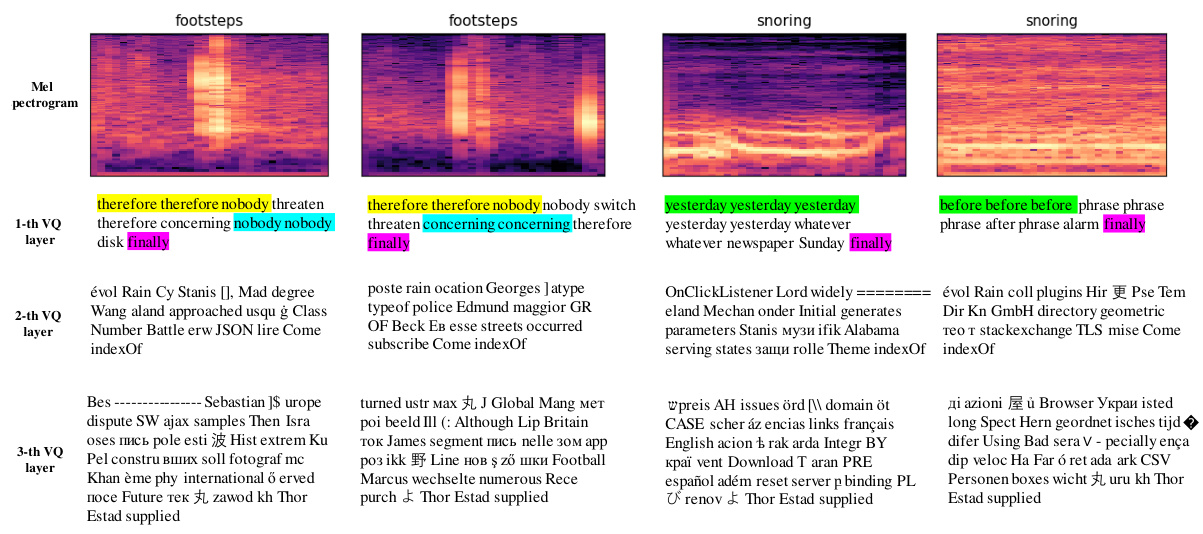

🔼 This figure visualizes the tokens generated by the semantic layer of the LLM-Codec for different audio samples. The figure shows that audio recordings of the same sound event tend to have similar token sequences, even if the acoustic conditions differ. The consistent token patterns across similar audio events suggest that the model effectively captures semantic meaning, which may explain its ability to learn new sound events quickly with minimal examples.

read the caption

Figure 4: The token visualization of the semantic layer of LLM-Codec is shown. We present two groups of samples, each containing two audio recordings with the same sound event label. In each group, we use the same color to highlight potentially similar patterns in the two audio recordings, such as identical token sub-sequences or token repeating frequencies. We speculate that these patterns can be easily recognized by LLMs, allowing them to learn new sound events quickly with just a few demonstrations.

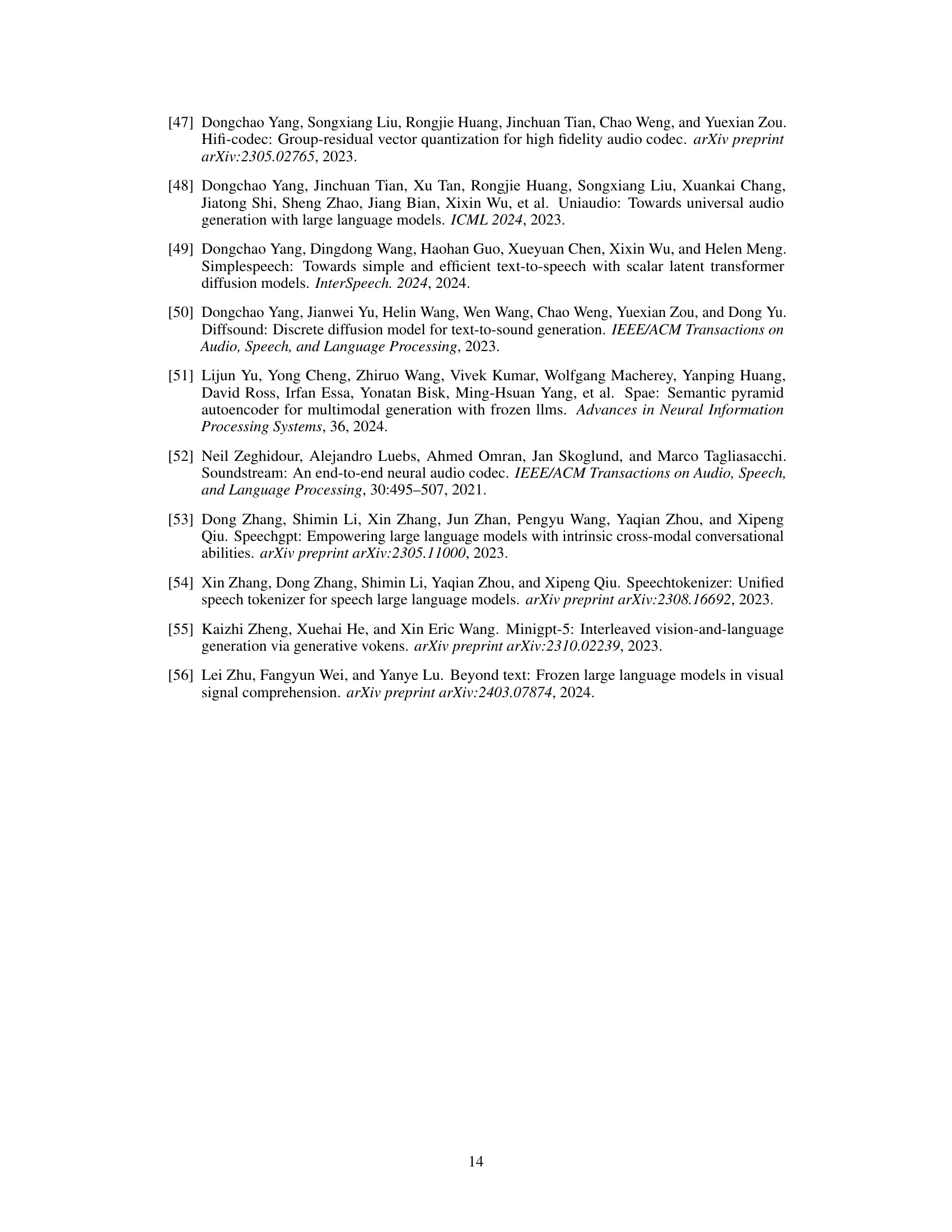

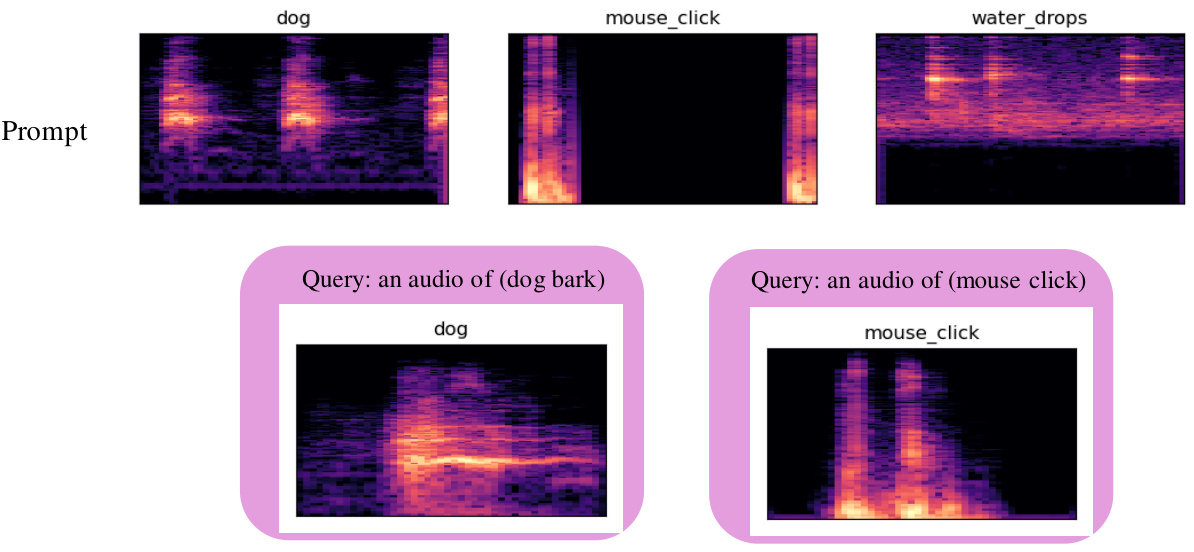

🔼 This figure shows examples of text-to-sound generation using the LLM-Codec and a frozen LLAMA2 7B model. The input is a text prompt describing the desired sound (e.g., ‘dog bark’, ‘mouse click’, ‘water drops’). The model generates a corresponding audio, and the mel-spectrograms of both the input audio prompts and the generated audio are displayed. This visualizes the model’s ability to generate new audio based on simple text instructions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Examples of simple text-to-sound generation on FSDD dataset using LLM-Codec with a frozen LLAMA2 7B model.

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the LLM-Codec, a model that compresses audio data into a lexical word sequence for use with LLMs. The model consists of three main components: an encoder that converts raw audio into latent representations; a multi-scale residual vector quantization (RVQ) module that compresses the latent representations into a sequence of discrete tokens (using three layers with different granularities); and a decoder that reconstructs the audio from the token sequence. A multi-scale discriminator is used during training. Note that some modules (indicated by snowflakes) are frozen during training, indicating that the model leverages pre-trained components.

read the caption

Figure 2: This figure provides a high-level overview of LLM-Codec, including an encoder, a decoder, a multi-scale discriminator, and multi-scale residual VQ layers. Here, 'sub' denotes feature subtraction. Note that the modules marked with a snowflake are frozen during training.

More on tables

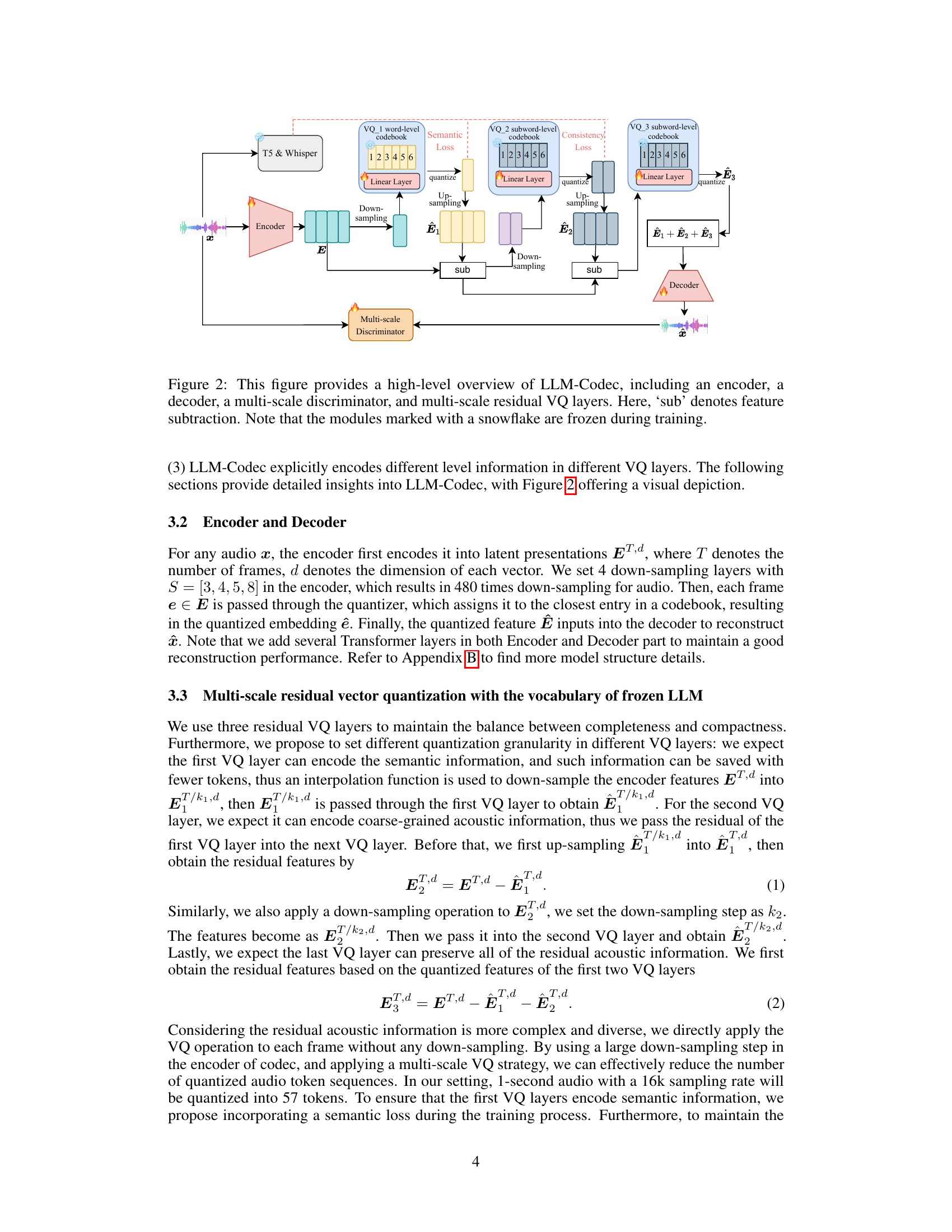

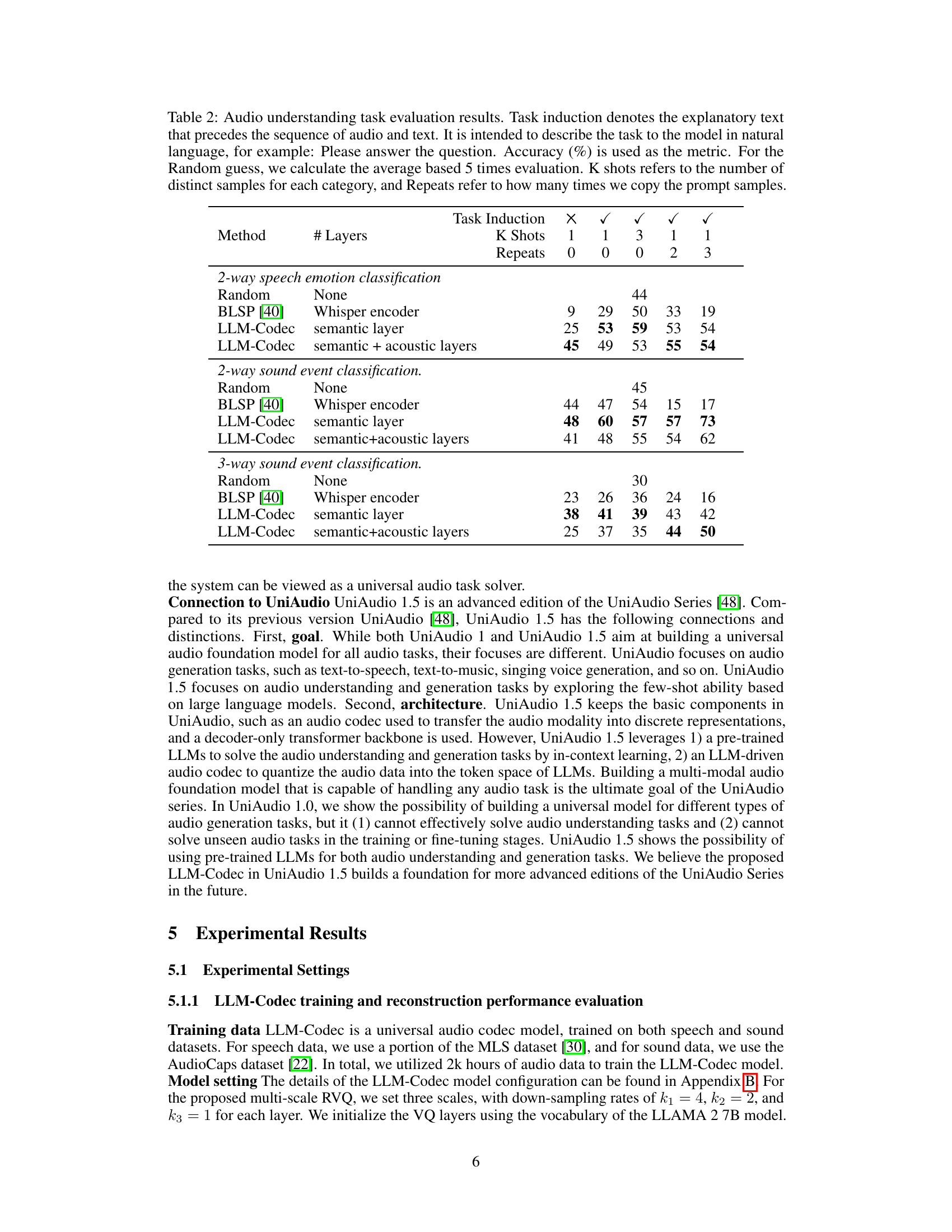

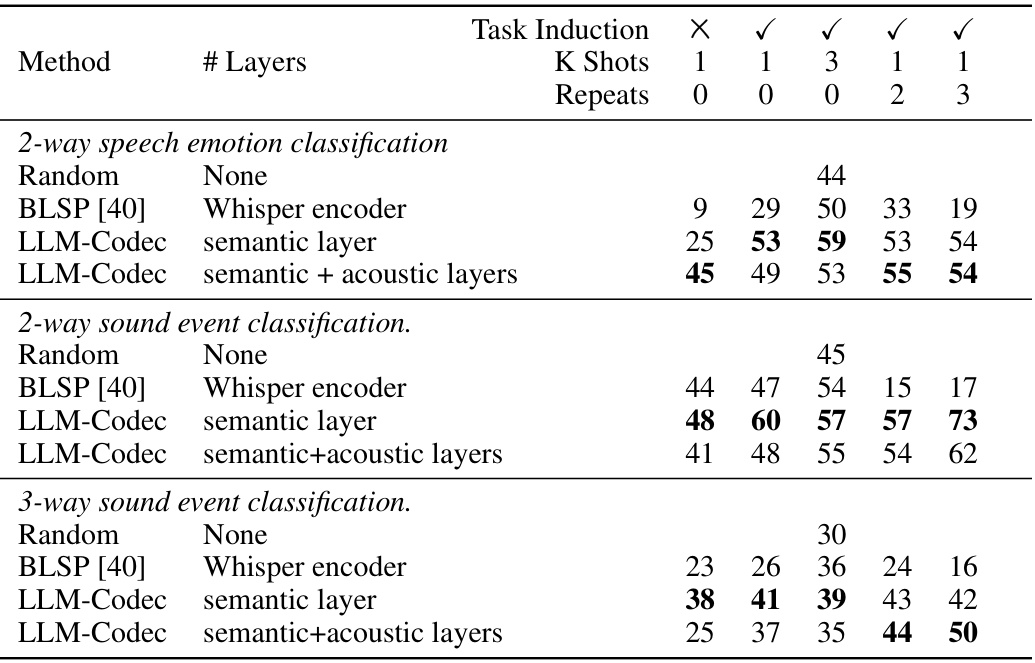

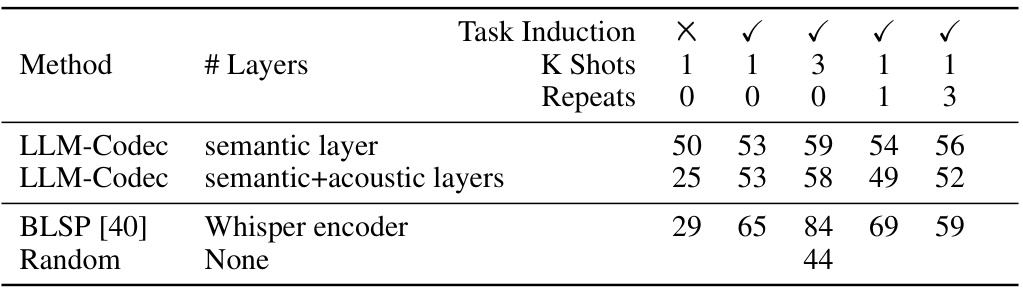

🔼 This table presents the results of audio understanding task evaluations, comparing different methods on speech emotion classification and sound event classification tasks. It shows the accuracy achieved by each method under various conditions: with/without task induction, different numbers of demonstration samples (K-shots), and repeated prompts. The goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed LLM-Codec in few-shot learning for audio understanding tasks.

read the caption

Table 2: Audio understanding task evaluation results. Task induction denotes the explanatory text that precedes the sequence of audio and text. It is intended to describe the task to the model in natural language, for example: Please answer the question. Accuracy (%) is used as the metric. For the Random guess, we calculate the average based 5 times evaluation. K shots refers to the number of distinct samples for each category, and Repeats refer to how many times we copy the prompt samples.

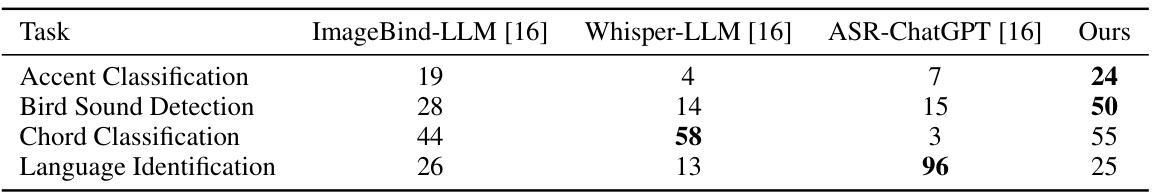

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of the proposed UniAudio 1.5 model against several baselines on the Dynamic-SUPERB benchmark. The benchmark consists of various audio understanding tasks, and the results show the accuracy achieved by each model, including ImageBind-LLM, Whisper-LLM, ASR-ChatGPT, and the UniAudio 1.5 model proposed in the paper. The accuracy is expressed as a percentage (%).

read the caption

Table 3: Evaluation on dynamic-superb benchmark tasks. Accuracy (%) is used as the metric.

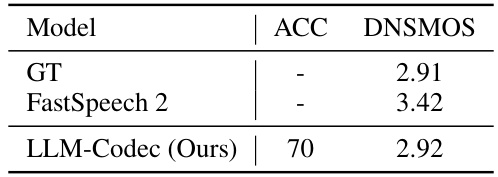

🔼 This table presents the performance of the proposed LLM-Codec model on a text-to-speech generation task. It compares the accuracy (ACC) and the DNSMOS (a speech quality metric) scores of the LLM-Codec model against a ground truth (GT) and the FastSpeech 2 model. The results demonstrate the LLM-Codec’s capability to generate speech with high quality and accuracy.

read the caption

Table 4: Text-to-speech generation performance.

🔼 This table presents the results of a speech denoising experiment, comparing the performance of the proposed LLM-Codec model against the state-of-the-art SGMSE+ model. The evaluation metrics used are PESQ and STOI, which measure the perceptual quality and intelligibility of the denoised speech, respectively. The results show that while LLM-Codec achieves lower scores compared to SGMSE+, indicating that its denoising performance is not as good as SGMSE+, but still represents a functional capability within the context of the broader in-context learning framework examined in the paper.

read the caption

Table 5: Speech denosing evaluation.

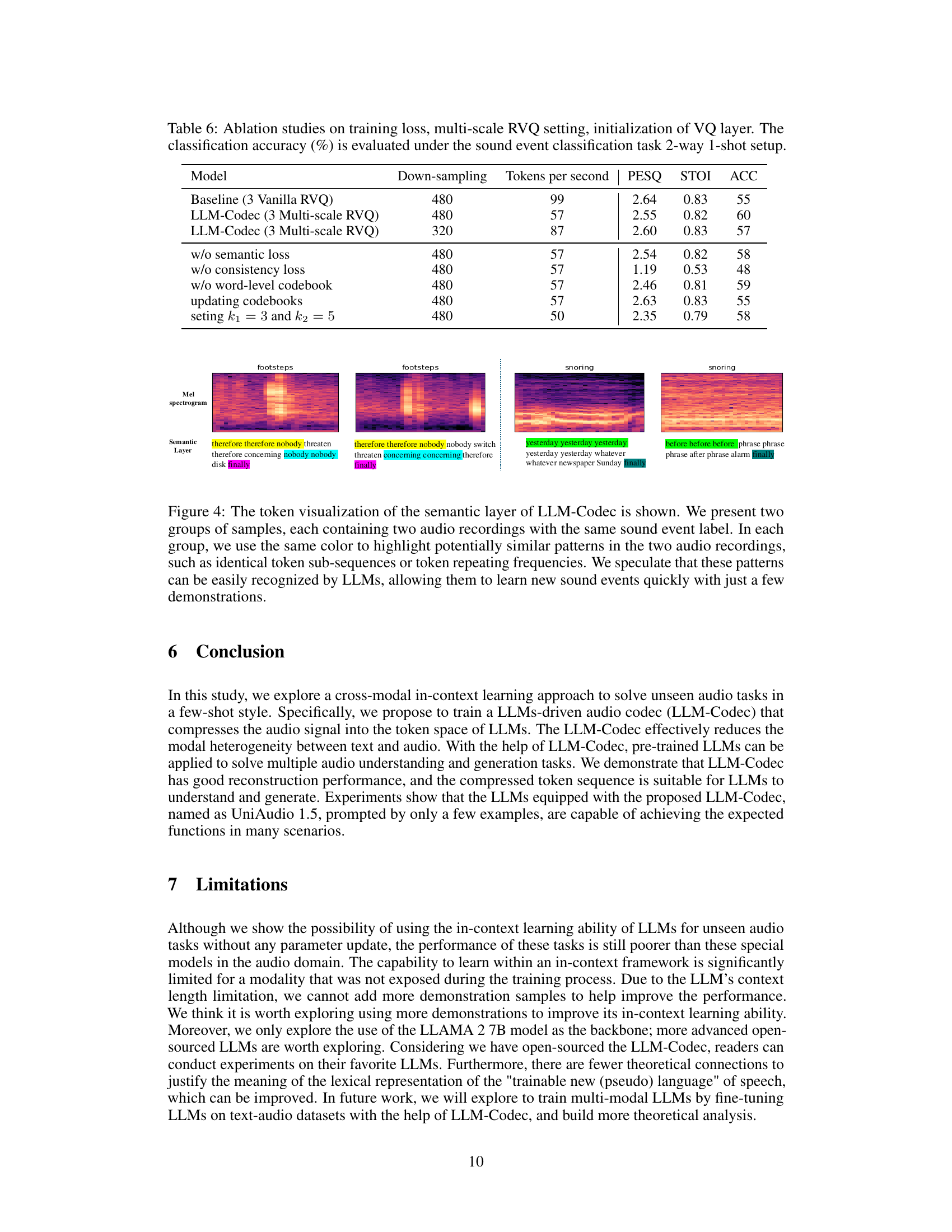

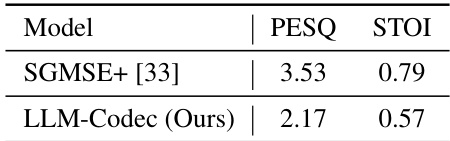

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of different design choices on the performance of the LLM-Codec model. Specifically, it investigates the effects of using multi-scale residual vector quantization (RVQ), the semantic loss, the consistency loss, the word-level codebook initialization, updating the codebooks during training, and different down-sampling settings (k1 and k2). The performance metric is the classification accuracy (%) evaluated using a 2-way 1-shot sound event classification task.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation studies on training loss, multi-scale RVQ setting, initialization of VQ layer. The classification accuracy (%) is evaluated under the sound event classification task 2-way 1-shot setup.

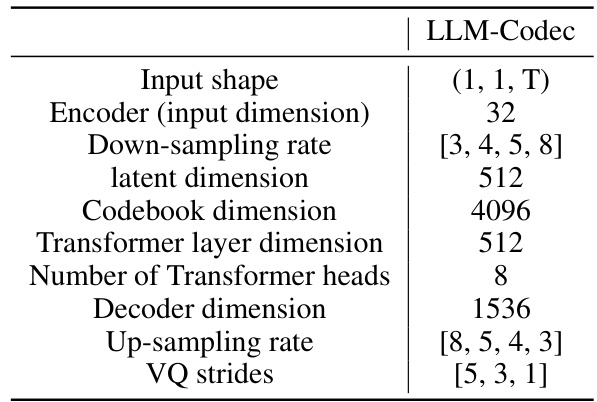

🔼 This table details the architecture of the LLM-Codec model, specifying the input shape, encoder and decoder dimensions, down- and up-sampling rates, codebook size, transformer layer dimensions, number of transformer heads, and VQ strides. This configuration results in a 160M parameter model.

read the caption

Table 7: LLM-Codec model backbone configurations

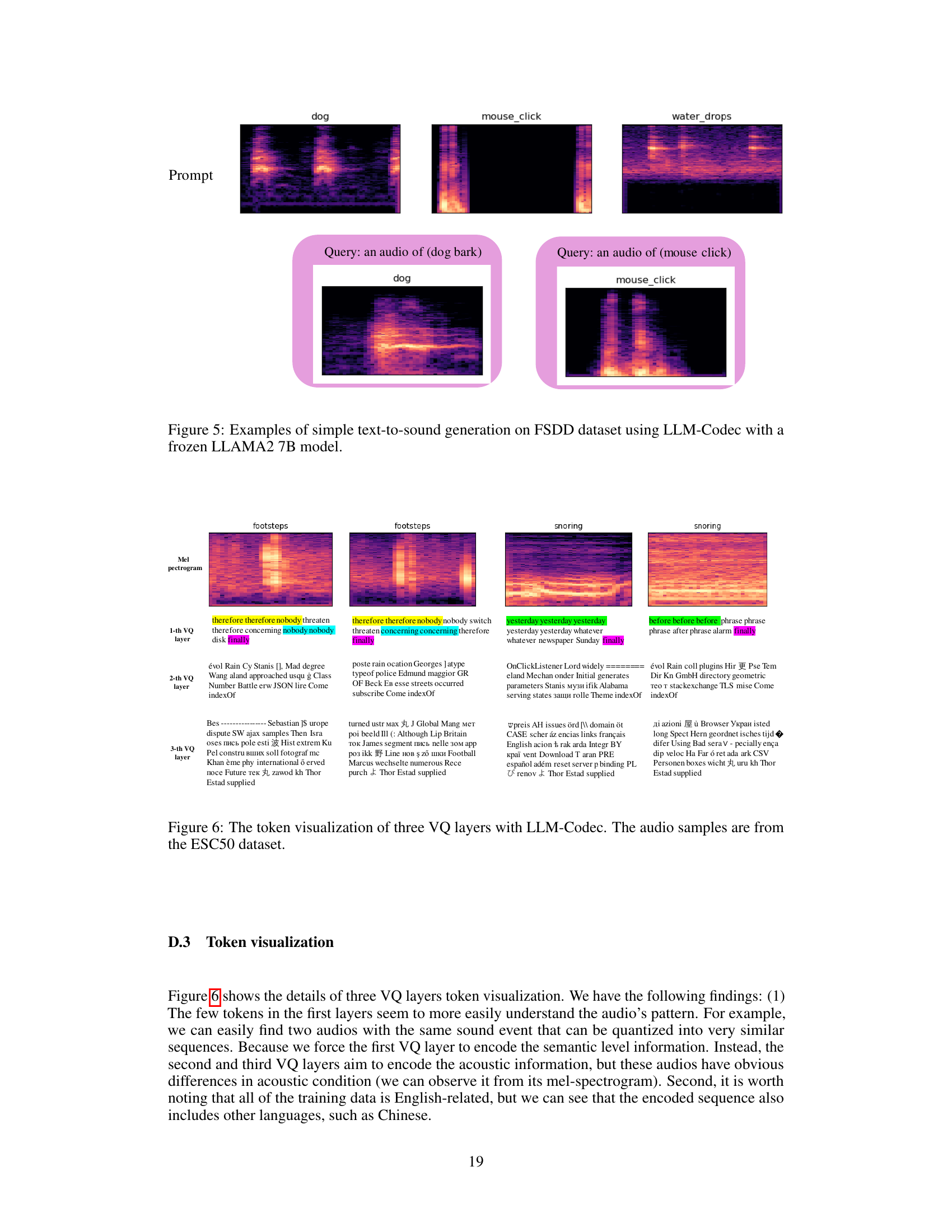

🔼 This table presents the results of audio understanding tasks, comparing the performance of different methods (LLM-Codec with different configurations, BLSP, and random guess) across various tasks and experimental settings (task induction, number of shots, number of repeated prompts). Accuracy is the primary metric, showing the effectiveness of the proposed LLM-Codec.

read the caption

Table 2: Audio understanding task evaluation results. Task induction denotes the explanatory text that precedes the sequence of audio and text. It is intended to describe the task to the model in natural language, for example: Please answer the question. Accuracy (%) is used as the metric. For the Random guess, we calculate the average based 5 times evaluation. K shots refers to the number of distinct samples for each category, and Repeats refer to how many times we copy the prompt samples.

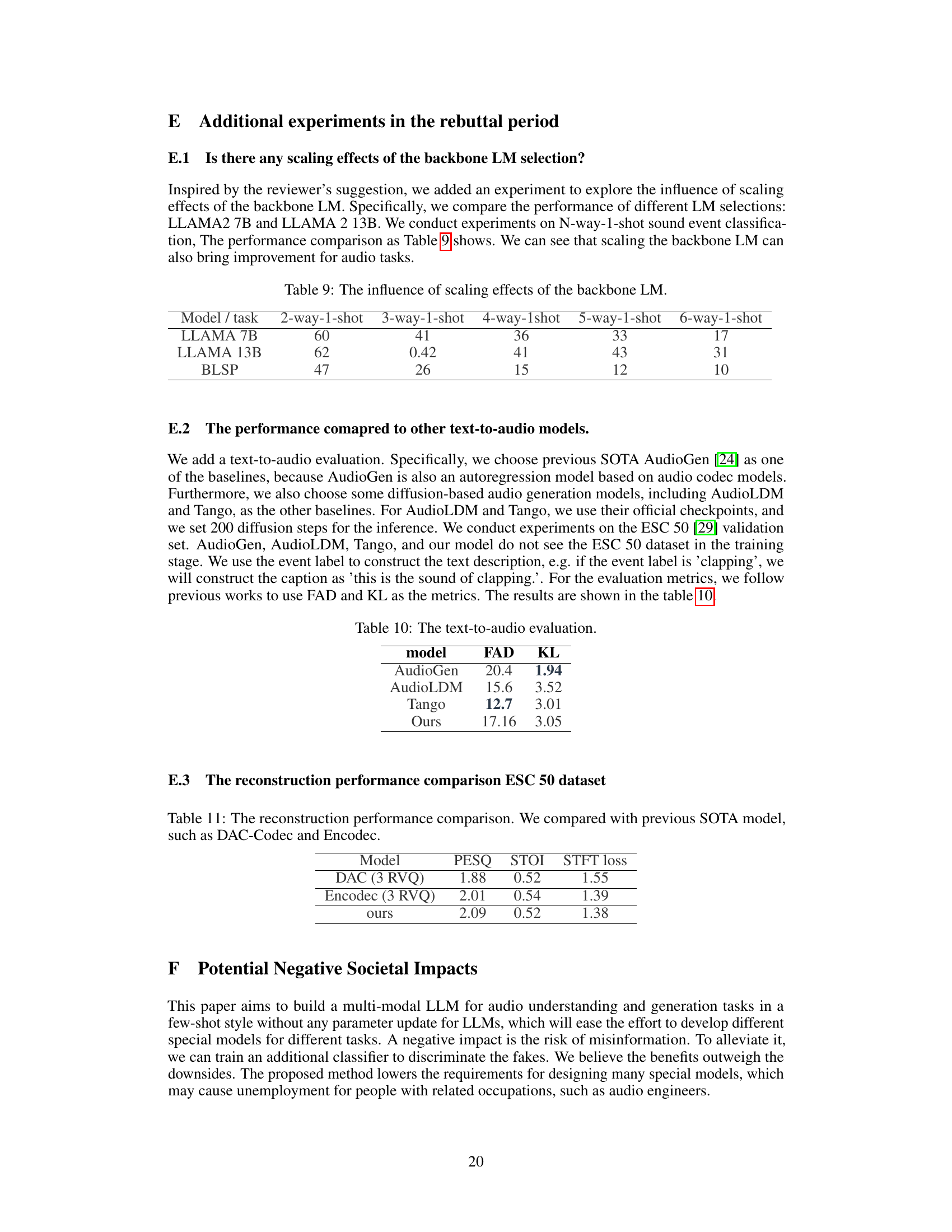

🔼 This table shows the impact of using different sizes of Large Language Models (LLMs) as backbones for the UniAudio 1.5 system. Specifically, it compares the performance of LLAMA 2 7B and LLAMA 2 13B models on a sound event classification task. The results are presented for various numbers of classes (2-way to 6-way) in a 1-shot setting (meaning only one example of each class is given to the model for learning before evaluation). The table demonstrates that increasing the LLM size improves the performance of the audio classification task.

read the caption

Table 9: The influence of scaling effects of the backbone LM.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed LLM-Codec model with several existing open-source audio codec models and baselines. The comparison is based on several metrics including the number of tokens per second, PESQ (Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality), STOI (Short-Time Objective Intelligibility), and the SFTF loss (a custom loss function). The results demonstrate that LLM-Codec achieves comparable or better reconstruction quality while using fewer tokens compared to the other methods. This highlights the effectiveness of the LLM-Codec in compressing audio data while preserving high-quality audio reconstruction.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison between open-sourced audio codec models, baselines, and the proposed LLM-Codec. * means the reproduced results by ourselves.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed LLM-Codec against existing open-source audio codecs (Encodec and DAC) and reproduced baselines. Metrics include the number of tokens produced per second, PESQ (Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality), STOI (Short-Time Objective Intelligibility), and the training loss (SFTF loss). The results showcase that LLM-Codec achieves comparable performance with fewer tokens, suggesting higher compression efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison between open-sourced audio codec models, baselines, and the proposed LLM-Codec. * means the reproduced results by ourselves.

Full paper#