TL;DR#

Current large language models (LLMs) struggle with spoken dialogs, often relying on separate automatic speech recognition (ASR) and text-to-speech (TTS) systems, which creates inconsistencies. This paper addresses this issue by introducing the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM). Existing methods lack the ability to naturally model prosodic features crucial for natural conversation. The limitations of these methods also hinder the ability to capture cross-modal semantics of speech and text.

USDM tackles these problems by using a novel speech-text pretraining scheme that enhances the capture of cross-modal semantics and incorporates prosody information directly within speech tokens. The model is then fine-tuned on spoken dialog data, utilizing a multi-step dialog template to stimulate chain-of-reasoning. Evaluation results demonstrate that USDM significantly outperforms existing baselines, generating more natural-sounding spoken responses. The provided code and checkpoints make this approach easily reproducible and applicable to a wide range of future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to spoken dialog modeling, addressing the limitations of existing methods that rely on separate ASR and TTS systems. It introduces a unified speech-text LLM framework that directly understands and synthesizes speech, leading to more natural and coherent spoken responses. This opens new avenues for research in speech-enabled LLMs and improves the user experience in human-computer interaction.

Visual Insights#

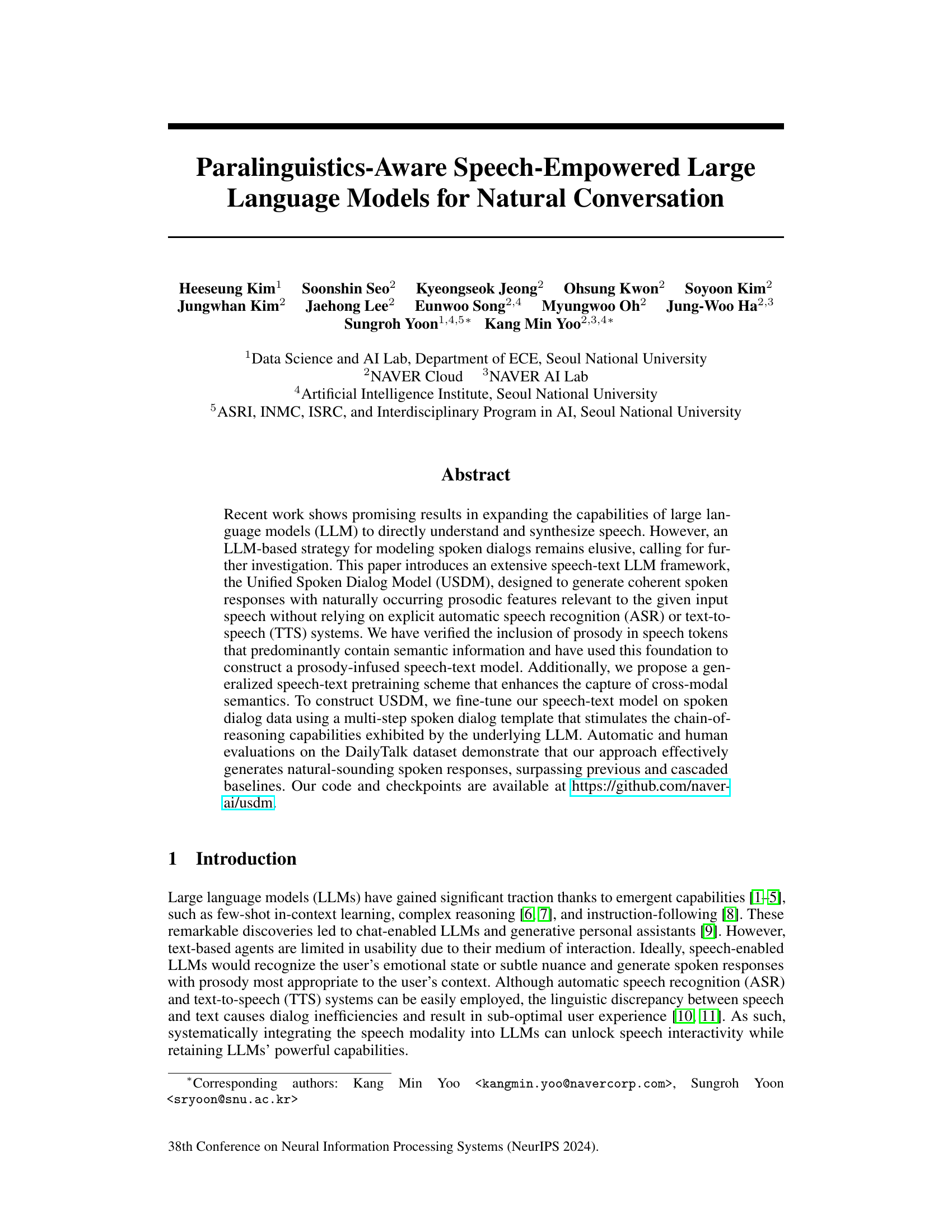

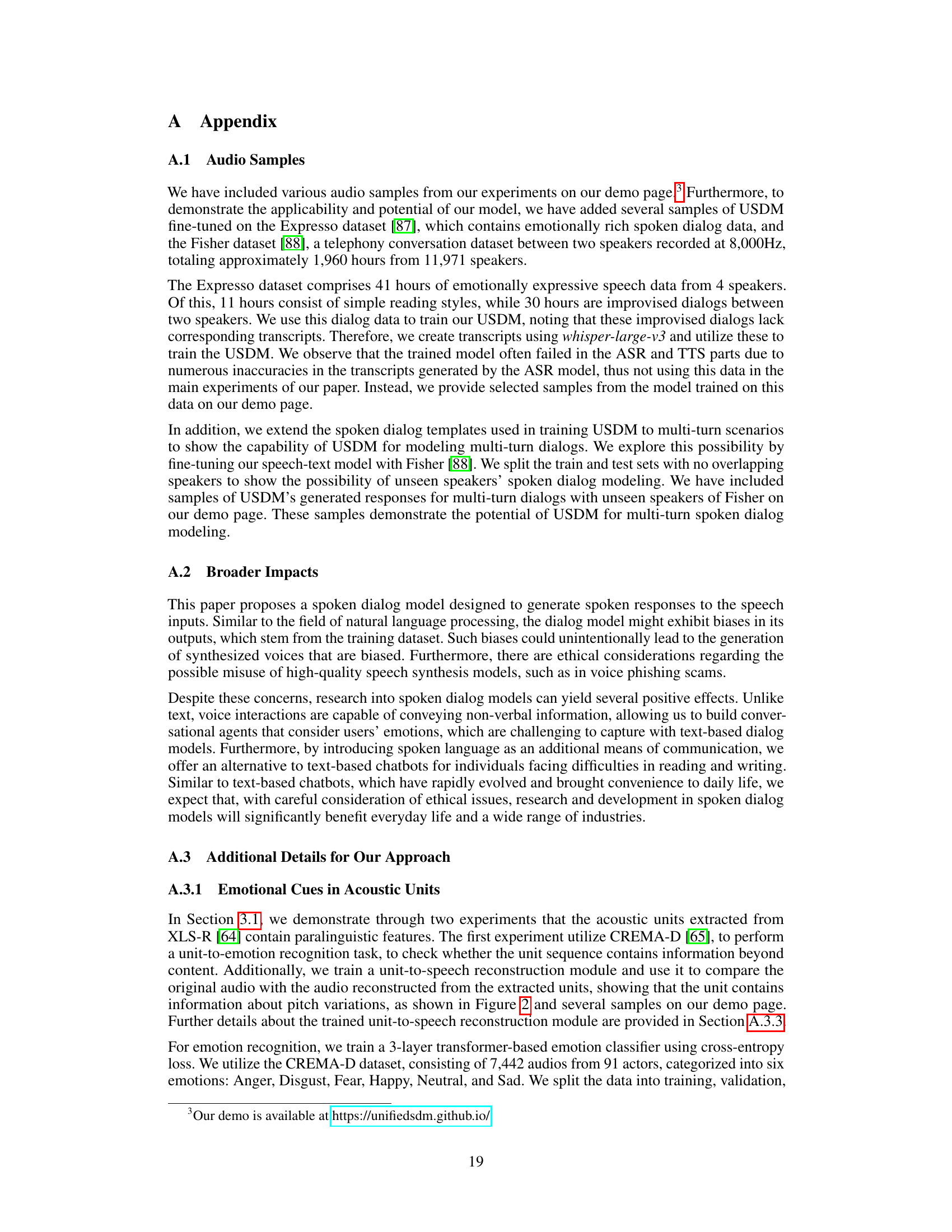

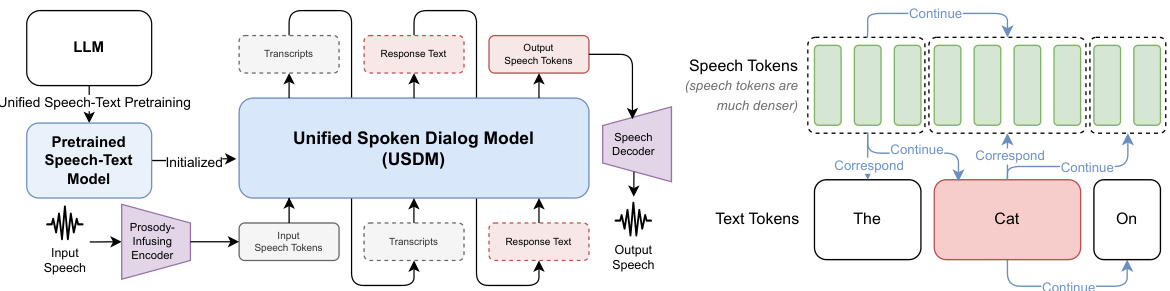

🔼 This figure illustrates the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) architecture. The left panel shows the overall framework, starting from input speech, which is processed by a prosody-infusing encoder and then fed into the USDM. The USDM generates response speech tokens, which are then decoded into raw waveforms. The right panel details the speech-text pretraining scheme used to enhance cross-modal understanding, showcasing how speech and text tokens are interleaved and processed to learn coherent relationships. It highlights the use of special tokens (<|continue|> and <|correspond|>) to guide the model’s generation process.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our spoken dialog modeling approach (Left). All possible self-supervised learning objectives from our speech-text pretraining scheme. (Right)

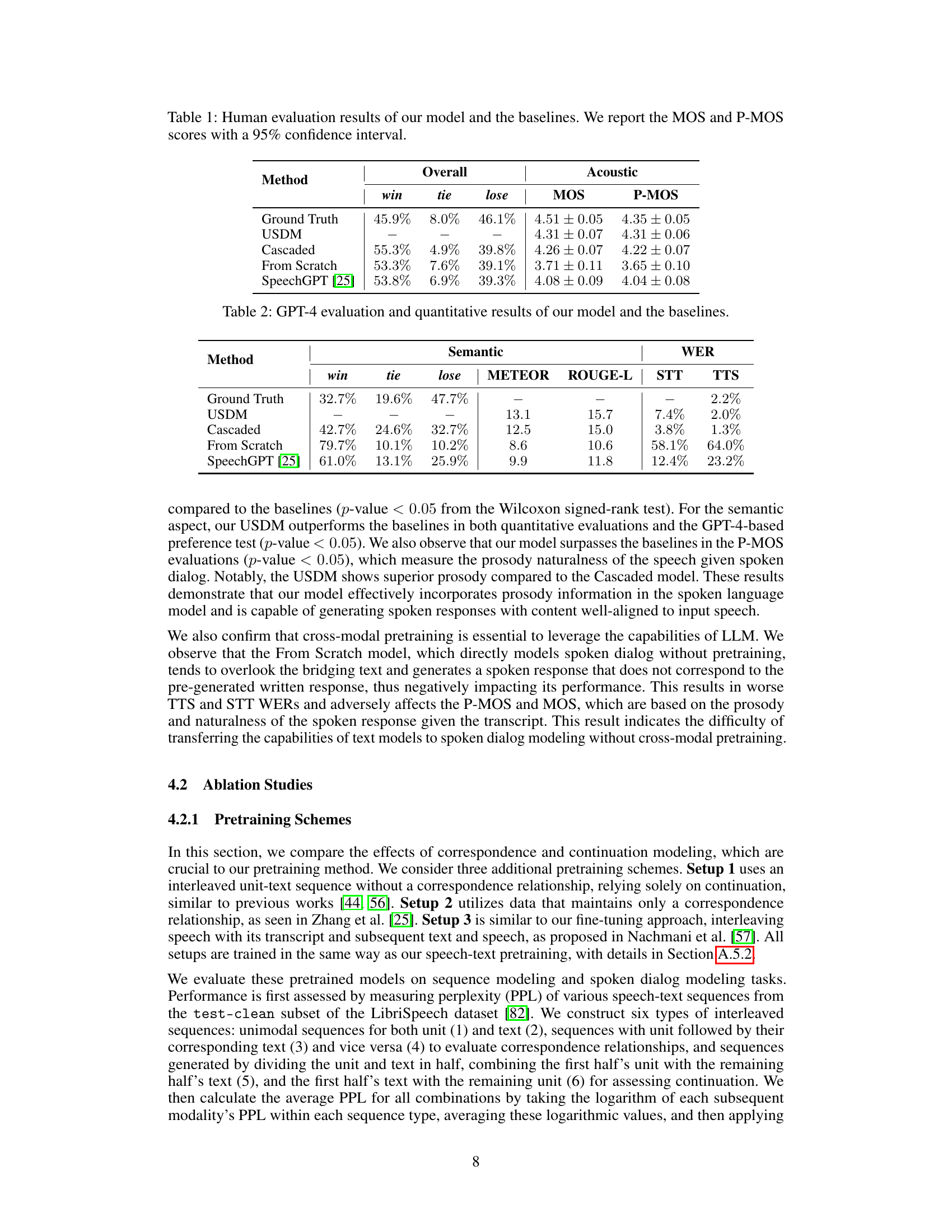

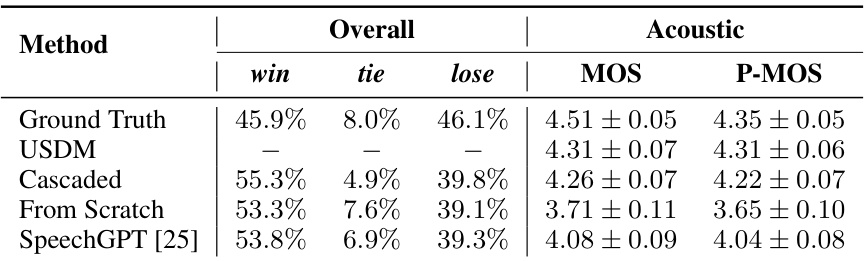

🔼 This table presents the results of a human evaluation comparing the proposed Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) against three baseline models: Cascaded, From Scratch, and SpeechGPT. The evaluation assesses overall preference, and specifically the acoustic quality (MOS) and prosody (P-MOS) of the generated spoken responses. Higher scores indicate better performance. The Ground Truth is included as a reference point. The ‘win’, ’tie’, and ’lose’ columns represent the percentage of times each model was preferred over the others in a pairwise comparison.

read the caption

Table 1: Human evaluation results of our model and the baselines. We report the MOS and P-MOS scores with a 95% confidence interval.

In-depth insights#

Speech-LLM Fusion#

Speech-LLM fusion represents a significant advancement in natural language processing, aiming to bridge the gap between human speech and the capabilities of large language models (LLMs). Effective fusion requires careful consideration of several key aspects: First, robust and accurate speech-to-text (STT) conversion is crucial to provide a reliable textual input for the LLM. Second, the LLM needs to be adapted or trained to effectively process and understand the nuances of spoken language, including paralinguistic cues like tone and intonation. Techniques such as incorporating prosodic information directly into the model’s embeddings or leveraging multi-modal training are particularly important. Third, generating natural-sounding speech from the LLM’s text output (text-to-speech or TTS) needs to be seamless and aligned with the context of the conversation. Furthermore, the system must be capable of handling real-time interactions, including dialogue management and turn-taking. Successful speech-LLM fusion holds enormous potential for applications requiring natural and intuitive human-computer interaction, such as virtual assistants, conversational AI systems, and accessibility tools. However, addressing challenges associated with speech variability, noise, and cross-modal alignment remains key to further advancing the field.

Prosody’s Role#

Prosody, the rhythm and intonation of speech, plays a crucial role in natural language understanding and generation. In speech-empowered large language models (LLMs), effectively incorporating prosodic information is vital for creating natural-sounding and contextually appropriate spoken responses. A model’s ability to understand and generate prosody impacts the perceived emotion, speaker identity, and overall fluency of speech. Simply relying on text-based representations limits a model’s ability to capture the nuances of spoken communication. Therefore, researchers are exploring innovative methods for representing and processing prosodic features, including advanced speech tokenization schemes that embed semantic and prosodic information within speech tokens. This approach promises to produce more human-like and engaging spoken dialog systems. Future work should continue to investigate the complex interplay between prosody and other linguistic factors to further enhance the realism and naturalness of speech synthesis in LLMs.

Multimodal Pretraining#

Multimodal pretraining is a crucial technique for enhancing the capabilities of large language models (LLMs). By training on diverse data encompassing text, images, and audio, LLMs learn to understand and generate information across different modalities. This approach helps bridge the gap between textual and non-textual data, thereby enabling a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the world. A key advantage lies in the development of cross-modal relationships, where the model can effectively transfer knowledge and contextual understanding from one modality to another. For example, an LLM trained on multimodal data might be able to generate image descriptions from textual prompts, or synthesize realistic speech given an image. Successful multimodal pretraining requires careful consideration of data selection, alignment, and model architecture. The choice of appropriate data is paramount, as it directly impacts the model’s ability to understand and represent different aspects of a given task. Effective data alignment strategies ensure that information across modalities is correctly linked, facilitating efficient knowledge transfer. Finally, specialized model architectures are often designed to seamlessly integrate and process data from various modalities. Overall, multimodal pretraining represents a powerful tool for building truly intelligent LLMs that can understand and interact with a rich and diverse range of information.

End-to-End Pipeline#

An end-to-end pipeline in a speech-related task aims to process audio input directly to a final output, such as text transcription or speech synthesis, without intermediate steps. This contrasts with traditional methods that separate the task into stages (e.g., acoustic modeling, language modeling, and text-to-speech conversion). The main benefit is the potential for improved performance and efficiency. By jointly optimizing all components within a single model, end-to-end systems can learn complex relationships between audio and output modalities more effectively, leading to higher accuracy and a more natural output. However, challenges remain. Training end-to-end models often requires substantial computational resources and large datasets. Furthermore, debugging and analysis can be more complex than in modular systems, where individual components can be evaluated separately. Despite these challenges, end-to-end approaches represent a significant advancement in the field, enabling more seamless and user-friendly speech technologies. They also open avenues for developing more powerful and robust models that can adapt better to diverse conditions and speaker variations.

Future: Cross-Lingual#

A cross-lingual future in this research implies extending the model’s capabilities beyond English. This necessitates multilingual data for both pretraining and fine-tuning, posing significant challenges in data acquisition and quality control. Successful cross-lingual adaptation would require careful consideration of linguistic variations, including morphology, syntax, and phonology, across different languages. Addressing potential biases inherent in multilingual datasets is crucial for fairness and equity. The evaluation methodology should also be adapted to accommodate linguistic diversity. Benchmarking the cross-lingual model’s performance against existing multilingual speech processing systems is essential to gauge its effectiveness. Furthermore, resource constraints, particularly in low-resource languages, need careful planning and efficient algorithms to optimize computational cost and achieve scalability. Ultimately, this ambitious goal presents a significant opportunity to improve cross-cultural communication and access to information globally.

More visual insights#

More on figures

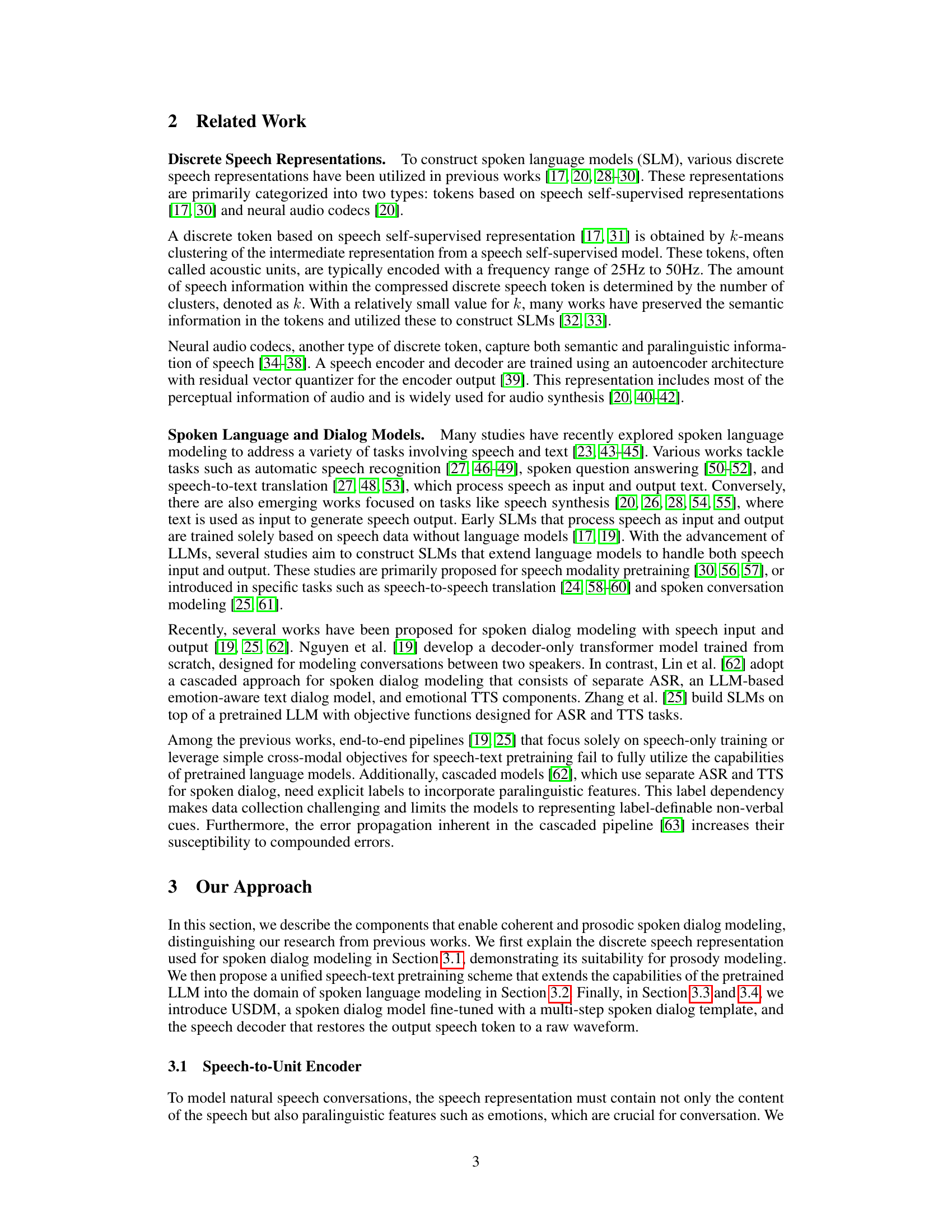

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of pitch contours between the original audio and two reconstructions from the extracted acoustic units. The stochastic nature of the reconstruction process is highlighted by showing two slightly different reconstructions. Despite this, both reconstructions closely follow the pitch changes of the original audio, indicating that the acoustic units effectively capture the pitch information present in the original speech.

read the caption

Figure 2: Pitch contour of the original audio and the audio reconstructed from extracted acoustic units. Due to the stochastic nature of the reconstruction model, we attempt reconstruction twice, demonstrating that the pitch variation closely mirrors the ground truth.

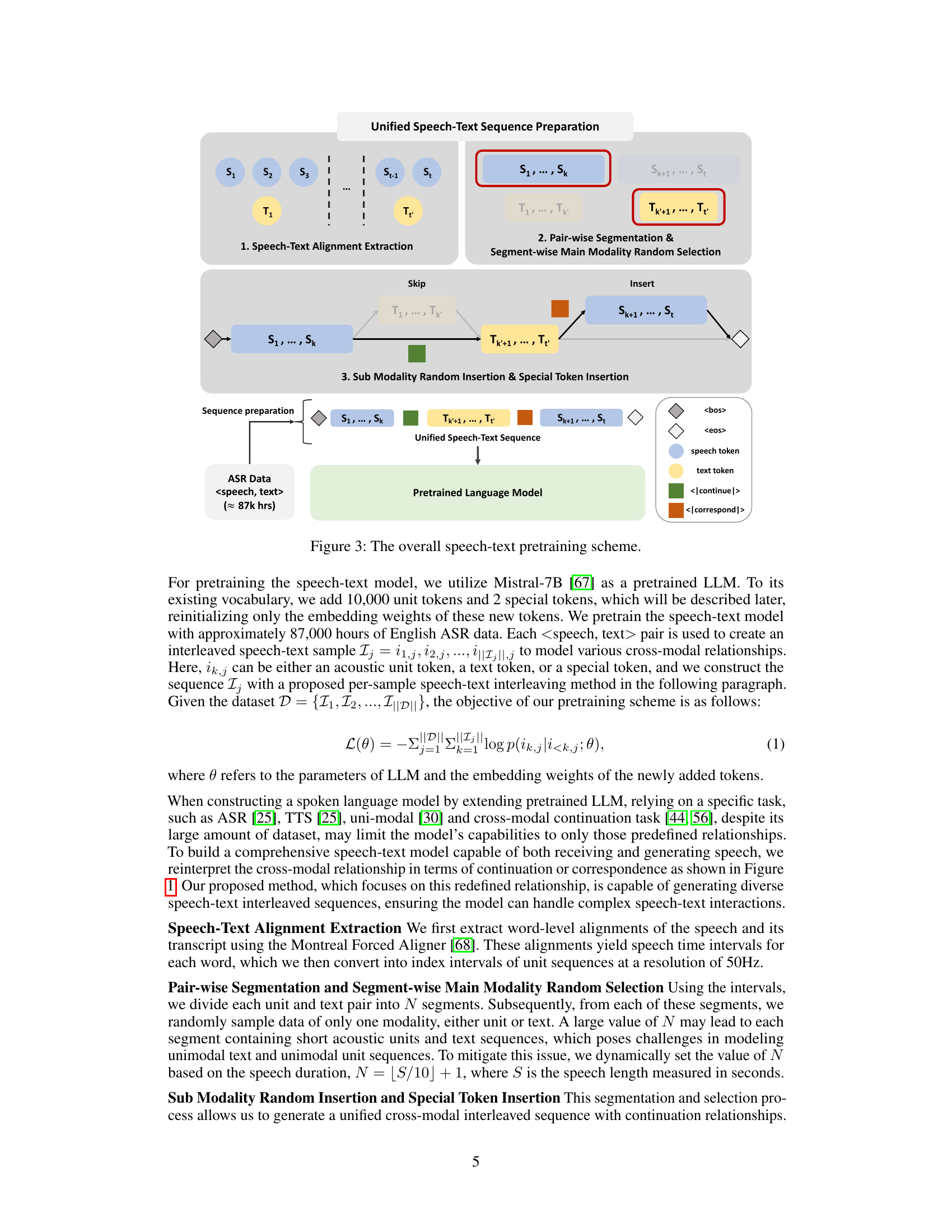

🔼 This figure shows the overall process of speech-text pretraining. It starts with speech-text alignment extraction, then pair-wise segmentation and segment-wise main modality random selection. Finally, sub-modality random insertion and special token insertion is performed to generate a unified speech-text sequence for training a pretrained language model. The figure also details the types of tokens used and what their purpose is in the process.

read the caption

Figure 3: The overall speech-text pretraining scheme.

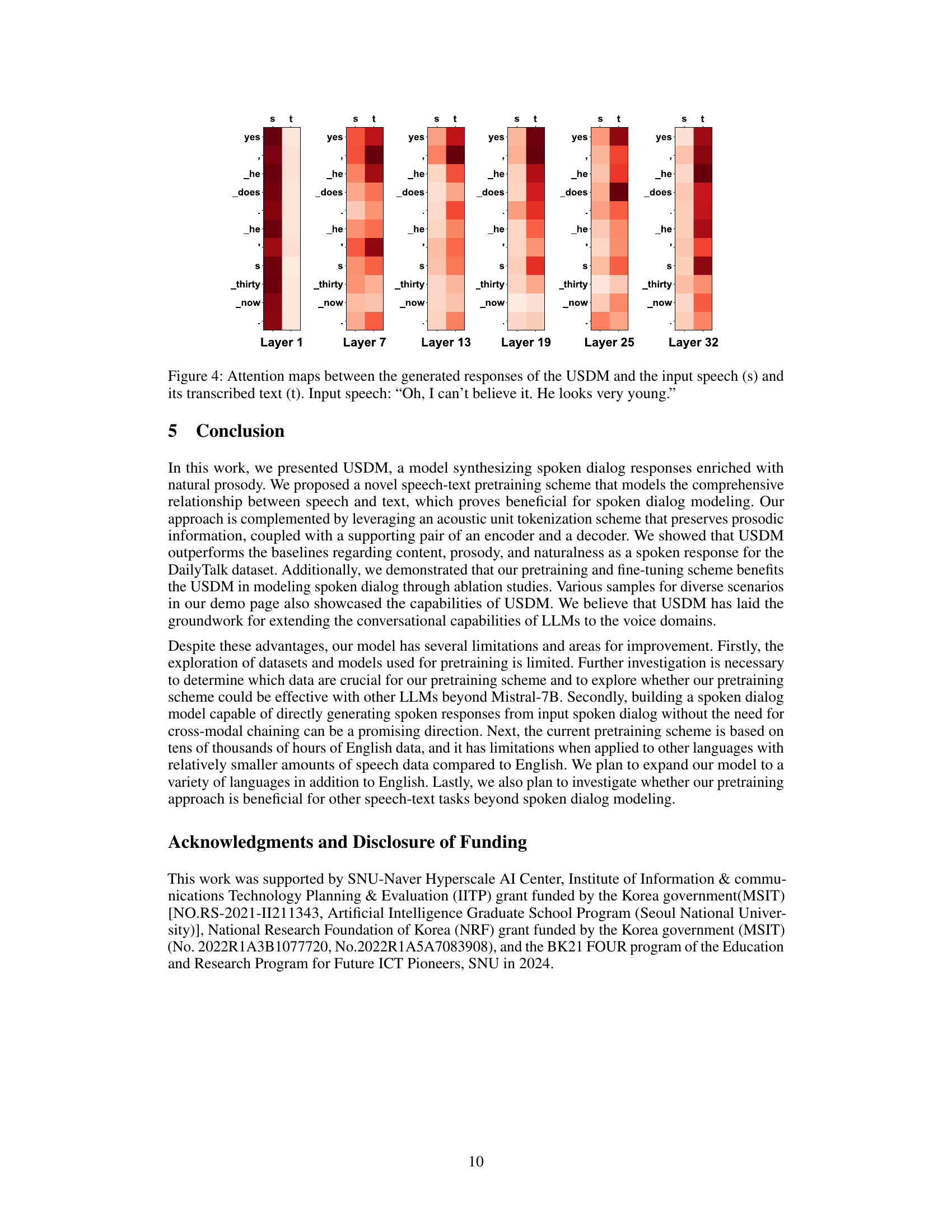

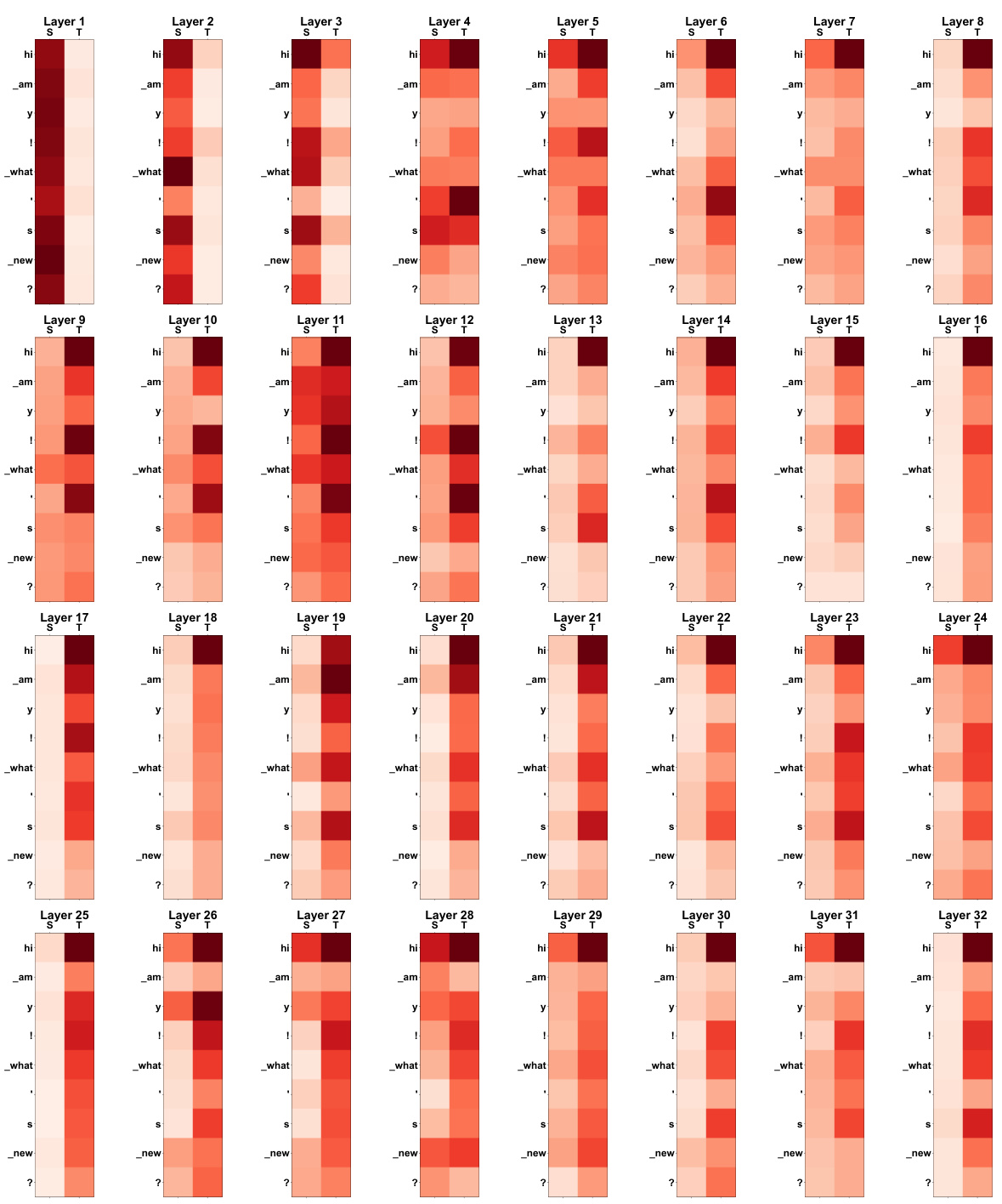

🔼 This figure displays the attention weights between the generated response tokens and both the input speech tokens and the corresponding transcribed text tokens at different layers of the USDM model. Warmer colors (reds) indicate higher attention weights. This visualization helps to understand how the model uses both the speech and text modalities to generate its responses, showing the interplay between the two modalities and the model’s cross-modal attention mechanism.

read the caption

Figure 4: Attention maps between the generated responses of the USDM and the input speech (s) and its transcribed text (t). Input speech: “Oh, I can’t believe it. He looks very young.”

🔼 This figure provides an overview of the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) and its training process. The left panel shows the overall architecture of the USDM, illustrating how input speech is processed through a prosody-infusing encoder, a pretrained speech-text model, and a speech decoder to generate coherent spoken responses. The right panel details all the self-supervised learning objectives used during speech-text pretraining to capture rich cross-modal semantics between speech and text. This multi-step approach aims to enhance the model’s ability to generate natural-sounding spoken responses within the context of spoken dialog.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our spoken dialog modeling approach (Left). All possible self-supervised learning objectives from our speech-text pretraining scheme. (Right)

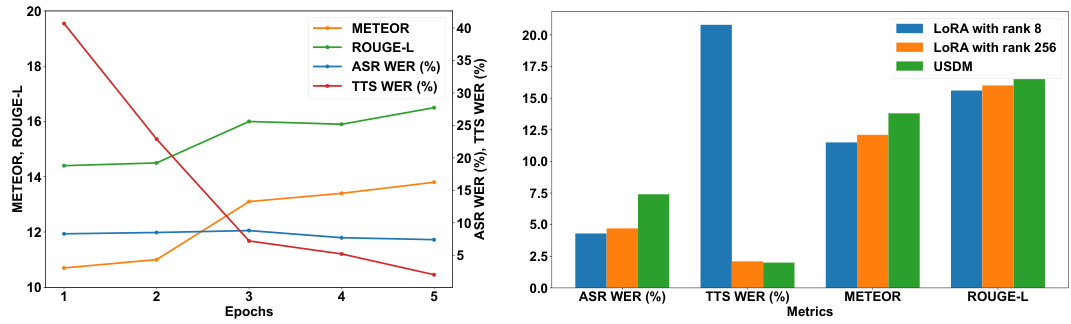

🔼 The left plot shows the performance of different metrics (METEOR, ROUGE-L, ASR WER, TTS WER) over epochs during the training of the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM). The right plot compares the performance of USDM trained with full fine-tuning against versions using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) with different ranks (8 and 256). It highlights the trade-offs between model size and performance on various metrics.

read the caption

Figure 7: Left is the quantitative results for each epoch of the USDM fine-tuned on DailyTalk. The figure on the right illustrates the performance of the Spoken Dialog Model when trained with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) versus full fine-tuning.

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of preparing unified speech-text sequences for pretraining a speech-text model. It involves three main steps: 1. Speech-Text Alignment Extraction: extracting word-level alignments between speech and text using the Montreal Forced Aligner; 2. Pair-wise Segmentation & Segment-wise Main Modality Random Selection: dividing the aligned speech and text into segments and randomly selecting one modality (speech or text) per segment; and 3. Sub-Modality Random Insertion & Special Token Insertion: inserting data from the non-selected modality with a certain probability and introducing special tokens to denote relationships between the modalities. The resulting unified sequences are used to train the speech-text model, enabling it to capture complex speech-text interactions.

read the caption

Figure 3: The overall speech-text pretraining scheme.

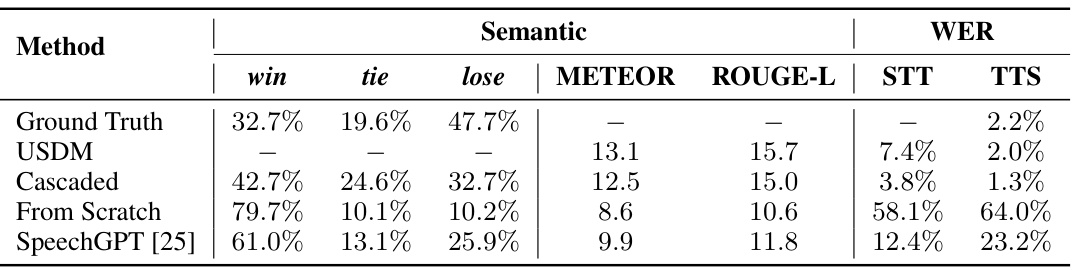

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) against three baselines (Cascaded, From Scratch, and SpeechGPT) using both qualitative and quantitative metrics. The qualitative evaluation utilizes GPT-4 to assess the semantic quality of generated responses, providing win/tie/lose percentages across all model comparisons. Quantitative analysis includes METEOR and ROUGE-L scores, which measure the semantic similarity between generated and ground truth responses, as well as STT (Speech-to-Text) and TTS (Text-to-Speech) Word Error Rates (WER). Lower WER values are better. This table summarizes how USDM outperforms the baselines in various aspects such as semantic similarity and naturalness of speech, while highlighting the importance of the proposed pretraining and fine-tuning techniques.

read the caption

Table 2: GPT-4 evaluation and quantitative results of our model and the baselines.

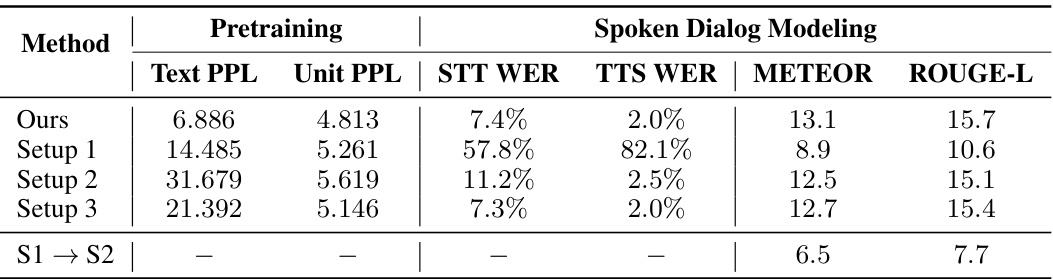

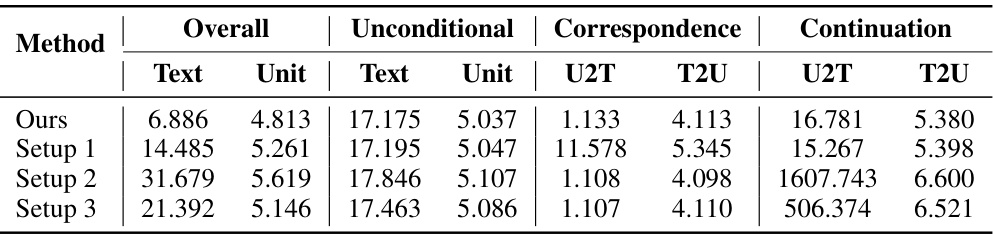

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of different pretraining and fine-tuning schemes on the model’s performance. The table shows the average perplexity (PPL) for both text and unit modalities, across six different combinations of interleaved speech-text sequences. It also shows the performance of the model on various downstream tasks like speech-to-text WER, text-to-speech WER, METEOR and ROUGE-L scores for spoken dialog modeling after different pretraining schemes. The comparison helps to understand which approach is the most effective.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of the ablation studies on the pretraining and fine-tuning schemes. For PPL, we report the average PPL for each modality across the six combinations described in the text.

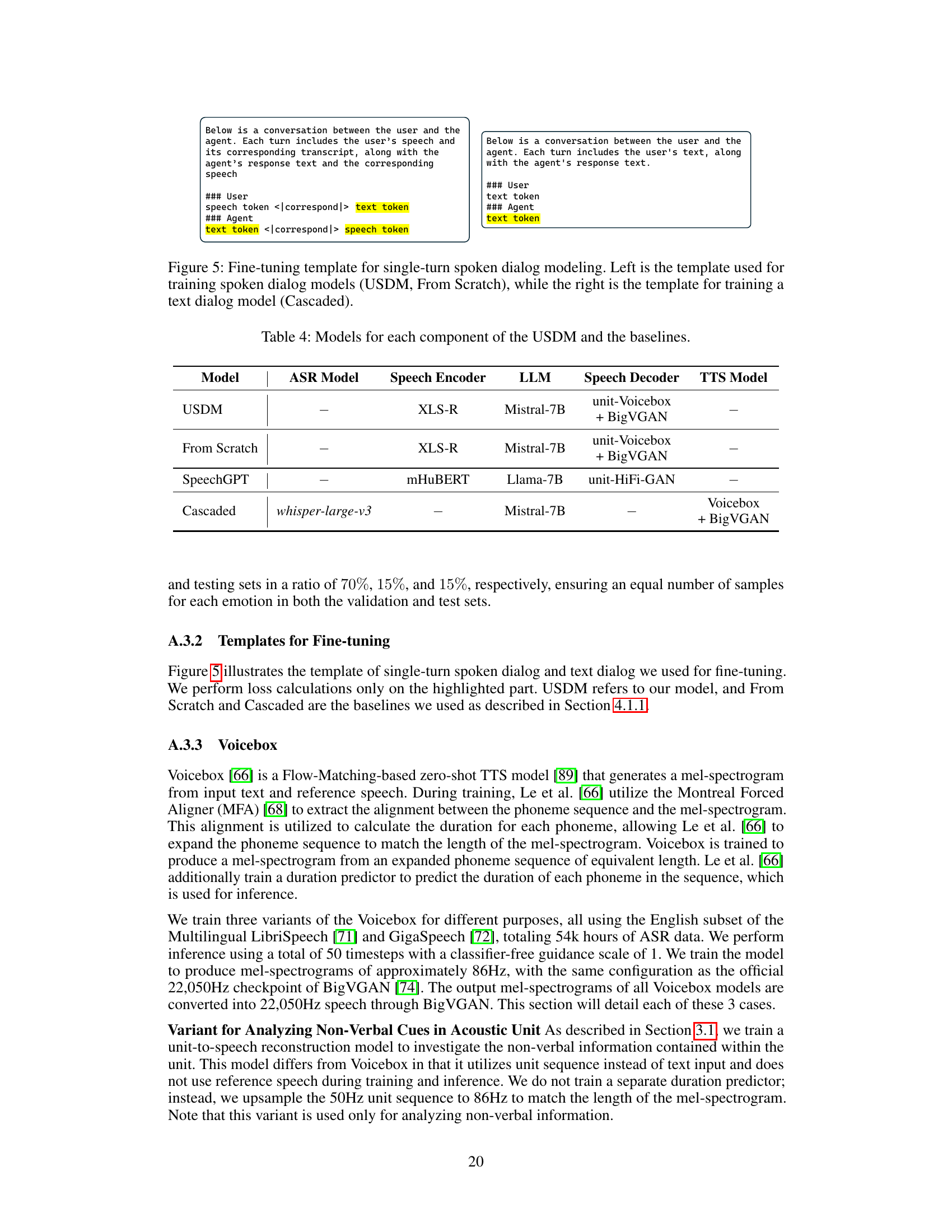

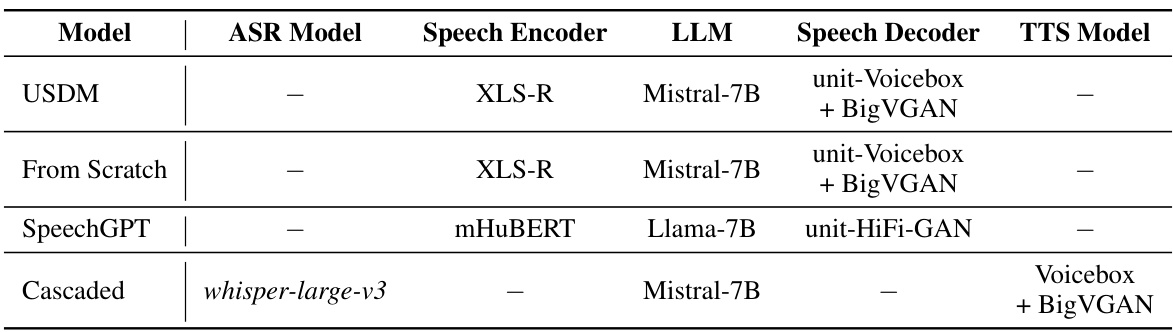

🔼 This table lists the specific models used for each component of the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) and three baseline models (From Scratch, Cascaded, and SpeechGPT). It shows the ASR model, speech encoder, language model (LLM), speech decoder, and TTS model used in each approach. This allows for a clear comparison of the different model architectures and their components.

read the caption

Table 4: Models for each component of the USDM and the baselines.

🔼 This table details the specific models used for each component of the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) and its three baselines: From Scratch, SpeechGPT, and Cascaded. For each model, it lists the ASR model (if applicable), the speech encoder, the large language model (LLM), the speech decoder, and the text-to-speech (TTS) model. This allows for a clear comparison of the architecture and components used in each model.

read the caption

Table 4: Models for each component of the USDM and the baselines.

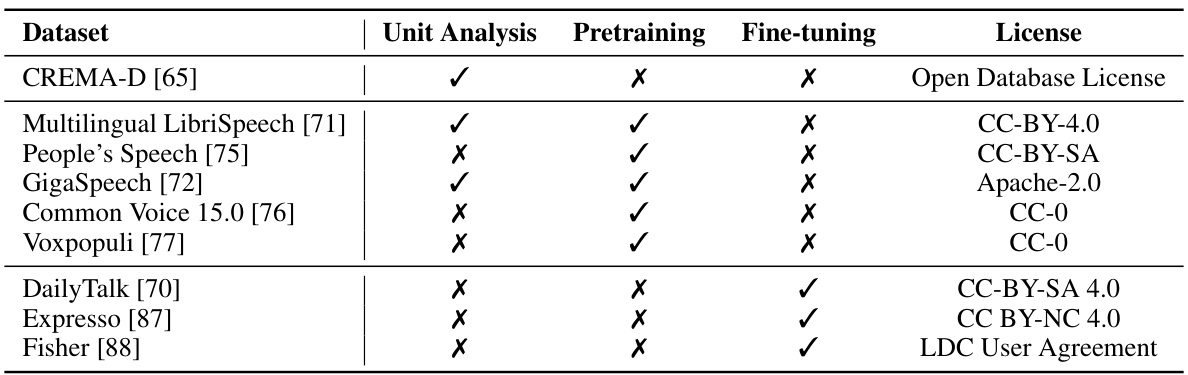

🔼 This table presents the licenses associated with each dataset used in the research. The datasets are categorized by their use in the study: acoustic unit analysis, pretraining, and fine-tuning of the model. This allows readers to quickly understand the legal permissions and restrictions associated with the data used in the experiments.

read the caption

Table 5: License of each dataset we used for acoustic unit investigation, pretraining, and fine-tuning.

🔼 This table lists the specific models used for each component of the Unified Spoken Dialog Model (USDM) and its baseline models. It shows the ASR model, speech encoder, language model (LLM), speech decoder, and TTS model used in each setup. This allows for a clear understanding of the different components and their configurations in each experimental setup.

read the caption

Table 4: Models for each component of the USDM and the baselines.

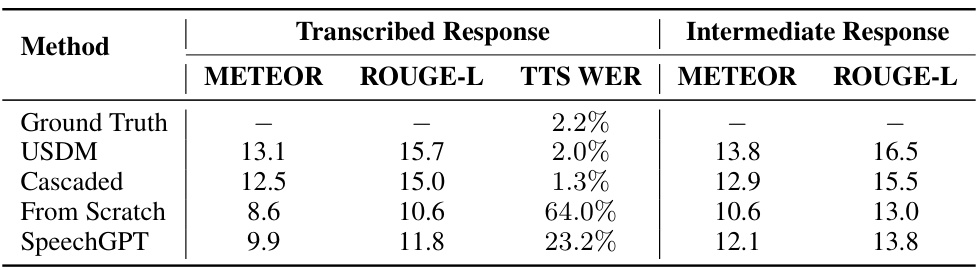

🔼 This table compares the performance of different models (USDM, Cascaded, From Scratch, and SpeechGPT) on two different evaluation methods for semantic quality. The ‘Transcribed Response’ results used automatic speech recognition (ASR) to convert the spoken responses into text before calculating METEOR and ROUGE-L scores, which measure semantic similarity. The ‘Intermediate Response’ results used the intermediate text generated by the model before speech synthesis, providing a direct comparison of the model’s text generation capabilities. The TTS WER (text-to-speech word error rate) is also included to assess the quality of the speech generated by each model.

read the caption

Table 7: METEOR and ROUGE-L results measured using the text obtained from ASR of the spoken response (Transcribed Response) and results measured using the intermediate text response (Intermediate Response).

🔼 This table presents six different types of interleaved speech-text sequences used to evaluate the performance of the pretrained model. The sequences are designed to test various relationships between speech and text, including unconditional, correspondence, and continuation relationships. For sequences testing continuation, the speech and text are split into two halves, and each half is combined with the other modality’s second half. The table also provides the templates used for calculating the perplexity (PPL) for each type of sequence.

read the caption

Table 8: Six types of speech-text interleaved sequences used to evaluate the performance of the pretrained model, along with the templates used for measuring PPL. For sequences with a continuation relationship, the speech and text data are split in half, combining one modality from the first half (e.g., speech1 token or text1 token) with the remaining modality from the second half (e.g., text2 token or speech2 token).

🔼 This table presents the perplexity (PPL) scores achieved by different pretraining schemes on the LibriSpeech dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed unified speech-text pretraining approach against three ablation studies: Setup 1 (continuation only), Setup 2 (correspondence only), and Setup 3 (a different interleaving strategy). The PPL is calculated separately for text and unit modalities, and overall. Lower PPL indicates better model performance. The results show that the unified approach outperforms the ablation studies.

read the caption

Table 9: PPL of various pretraining schemes for diverse unit and text combinations for the test-clean subset of LibriSpeech. T2U represents text-to-unit, and U2T represents unit-to-text, with PPL measured only for the subsequent modality. Lower is better.

Full paper#