TL;DR#

Tensor Product Representation (TPR) frameworks, while powerful for compositional generalization, struggle with decomposing unseen data into structured representations. This limits their ability to perform symbolic operations effectively. This decomposition problem hinders their applications in various fields requiring symbolic reasoning and systematic generalization.

The paper introduces a novel Discrete Dictionary-based Decomposition (D3) layer to solve this. D3 uses learnable key-value dictionaries to map input data to pre-learned symbolic features, thereby generating structured TPR representations. Experiments show that D3 significantly improves the systematic generalization of various TPR-based models across different tasks with minimal additional parameters, outperforming baselines on a combinatorial data decomposition task.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the decomposition problem in Tensor Product Representation (TPR)-based models, a significant hurdle in structured representation learning. By proposing a novel layer (D3) that leverages discrete dictionaries, it offers a practical solution to improve the systematic generalization of these models across various tasks. This work opens new avenues for enhancing the efficiency and interpretability of TPR-based approaches, making it relevant to researchers focusing on neuro-symbolic AI and compositional generalization.

Visual Insights#

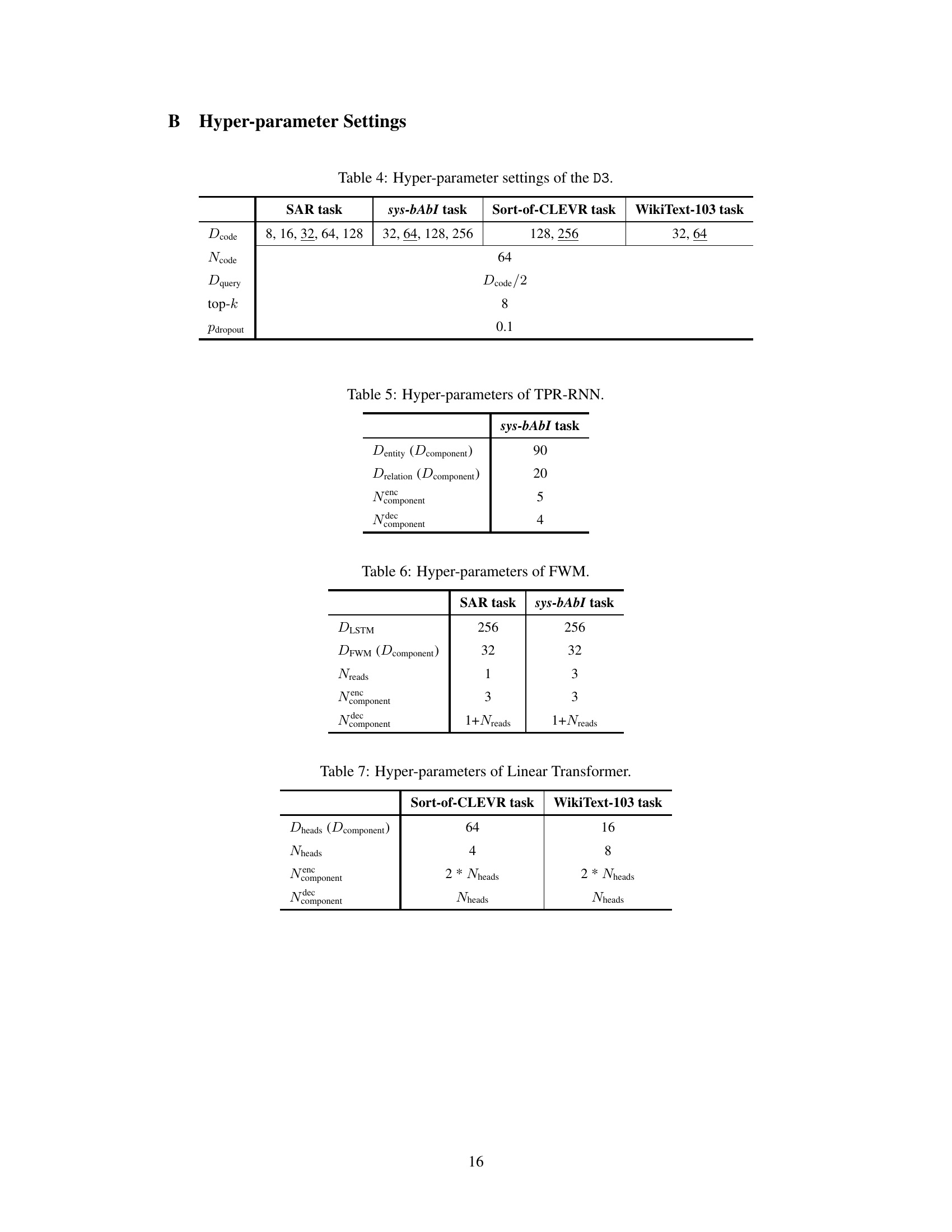

🔼 This figure illustrates the Discrete Dictionary-based Decomposition (D3) layer’s workflow. The D3 layer takes input data and generates queries for each TPR component (filler, role, and unbinding operator). These queries are used to access pre-learned symbolic features (codes) from separate key-value dictionaries. The selected codes are then aggregated to produce structured TPR representations. Note that the D3 layer uses shared dictionaries for roles and their corresponding unbinding operators.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of D3. D3 generates structured TPR representations by mapping input data to the nearest pre-learned symbolic features stored within discrete, learnable dictionaries. Each dictionary is linked explicitly to specific TPR components, such as roles, filler, and unbinding operators. Notably, D3 uses a shared dictionary configuration between the roles and unbinding operators. This figure illustrates, for example, that role₁ and unbind₁ share one dictionary, while role2 and unbind2 share another. T denotes a superimposed representation that represents multiple objects.

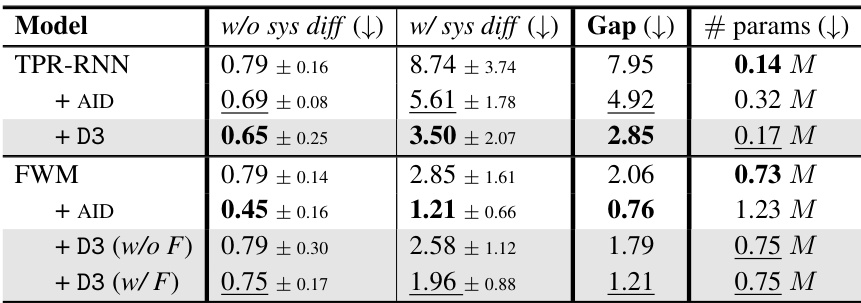

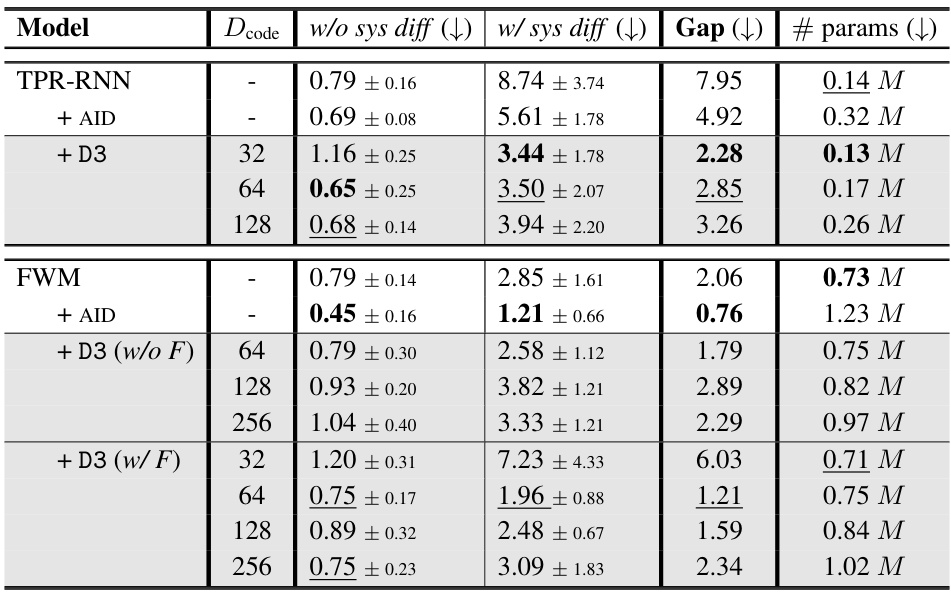

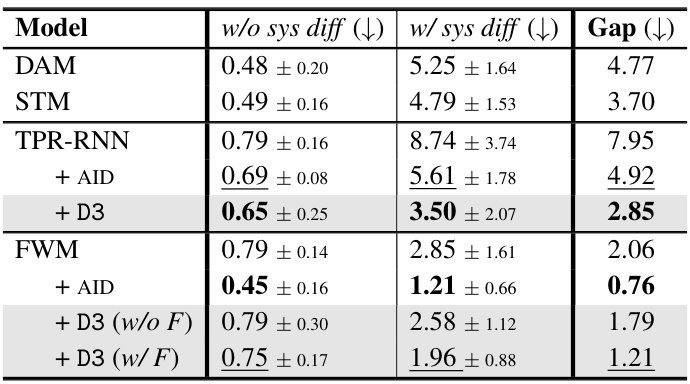

🔼 This table presents the results of the sys-bAbI task, a text understanding and reasoning task designed to assess systematic generalization. It shows the mean word error rate for different models: TPR-RNN, TPR-RNN with AID (attention-based iterative decomposition), and TPR-RNN with D3 (discrete dictionary-based decomposition). The results are broken down for in-distribution data (w/o sys diff) and out-of-distribution data with systematic differences (w/ sys diff), along with the gap between them and the number of parameters for each model. Lower error rates are better, indicating better systematic generalization.

read the caption

Table 1: The mean word error rate [%] on the sys-bAbI task for 10 seeds, with ± indicating SD.

In-depth insights#

TPR Decomposition#

The concept of “TPR Decomposition” centers on effectively breaking down input data into structured components suitable for processing within the Tensor Product Representation (TPR) framework. The challenge lies in accurately and consistently decomposing unseen data, which is crucial for the TPR’s compositional capabilities. Methods aiming to solve this often involve iterative refinement or attention-based mechanisms, yet these can struggle with diverse or complex data. A key area of improvement is developing robust and efficient decomposition layers that leverage learned features or dictionaries, allowing for mapping input data onto pre-defined symbolic representations. This approach can significantly enhance generalization and potentially reduce the computational burden associated with traditional iterative methods. Successful decomposition hinges on capturing the underlying symbolic structure of the data, necessitating techniques that go beyond simple feature extraction, potentially incorporating techniques like discrete representation learning. Overall, improvements in TPR decomposition are essential for advancing the framework’s utility in handling complex compositional tasks.

D3 Layer Design#

The core of the proposed approach lies in the novel D3 layer, a discrete dictionary-based decomposition layer designed to address the inherent decomposition challenges within TPR-based models. Instead of relying on complex iterative methods, D3 leverages the power of pre-trained, discrete, learnable key-value dictionaries. Each dictionary is specifically linked to a particular TPR component (role, filler, or unbinding operator), enabling it to learn the unique symbolic features necessary for generating that component. This explicit linkage enhances the model’s ability to effectively map input data to pre-learned representations. The integration is seamless; the D3 layer can be directly incorporated into existing TPR-based models simply by replacing the TPR component generation layer. This modular design is a significant strength, offering broad applicability and ease of integration. The use of discrete representations promotes efficiency and interpretability. By mapping to discrete features, computational costs are reduced, and the system’s decisions become more easily understood. The experimental results support the claims, demonstrating that D3 significantly boosts the systematic generalization capabilities of TPR-based models while requiring far fewer additional parameters. The shared dictionary configuration between roles and unbinding operators further enhances efficiency and leverages the inherent correlation between these elements within the TPR framework.

Systematic Generalization#

Systematic generalization, a crucial aspect of robust AI, focuses on a model’s ability to extrapolate learned knowledge to novel, unseen combinations of familiar concepts. This contrasts with simple generalization, where the model encounters similar instances to those in the training data. The core challenge lies in enabling models to compose knowledge in a structured and systematic manner, rather than relying on memorization or superficial pattern matching. Successfully achieving systematic generalization often requires incorporating explicit symbolic reasoning or compositional architectures that explicitly represent relationships between components, thereby addressing the limitations of purely data-driven approaches. Methods focusing on disentangled representations, where individual factors contributing to a concept are clearly separated, are promising avenues to enhance systematic generalization. Likewise, approaches explicitly modeling relationships between concepts, such as those based on graph neural networks or tensor product representations, have shown promise. Ultimately, successful systematic generalization depends on moving beyond simple pattern recognition towards a deeper, more structured understanding of the underlying data generating process.

Discrete Representation#

Discrete representations offer a compelling alternative to continuous representations in machine learning, particularly when dealing with symbolic or structured data. Discretization allows for the incorporation of prior knowledge and inductive biases, which can be particularly advantageous in scenarios where data is sparse or high-dimensional. This approach may also enhance interpretability by associating learned features with discrete categories or symbols. The use of discrete representations can lead to more efficient and memory-friendly models, and often allows for more explainable models where the decision-making process is clearer due to simpler calculations. However, the choice of discretization method and the representation of the discrete values can significantly affect the performance and efficiency of the model. Furthermore, working with discrete data introduces complexities in optimization and backpropagation, thus demanding specialized techniques. Finding the balance between the advantages of reduced dimensionality and the potential drawbacks of information loss during discretization remains a key challenge in successfully applying discrete representations to solve real-world problems.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this discrete dictionary-based decomposition layer (D3) for structured representation learning could explore several promising avenues. Extending D3’s applicability to a wider range of tasks and datasets beyond those considered in the paper is crucial. This includes evaluating its performance on more complex real-world problems and investigating its robustness across various data distributions. A deeper investigation into the theoretical properties of D3 could reveal insights into its generalization capabilities and potential limitations. Analyzing the interplay between the discrete dictionaries, the TPR framework’s underlying assumptions, and the system’s overall performance is a key area for future exploration. This includes a more detailed study of the hyperparameter selection process and its impact on the model’s behavior. Furthermore, research could focus on improving D3’s efficiency, particularly in handling large datasets, by exploring optimization techniques or architectural modifications. Finally, combining D3 with other recent advancements in compositional generalization and neuro-symbolic AI could unlock new possibilities for creating more powerful and interpretable AI systems. Investigating the interactions between D3 and other modules for handling complexity within the TPR framework would be of great value.

More visual insights#

More on figures

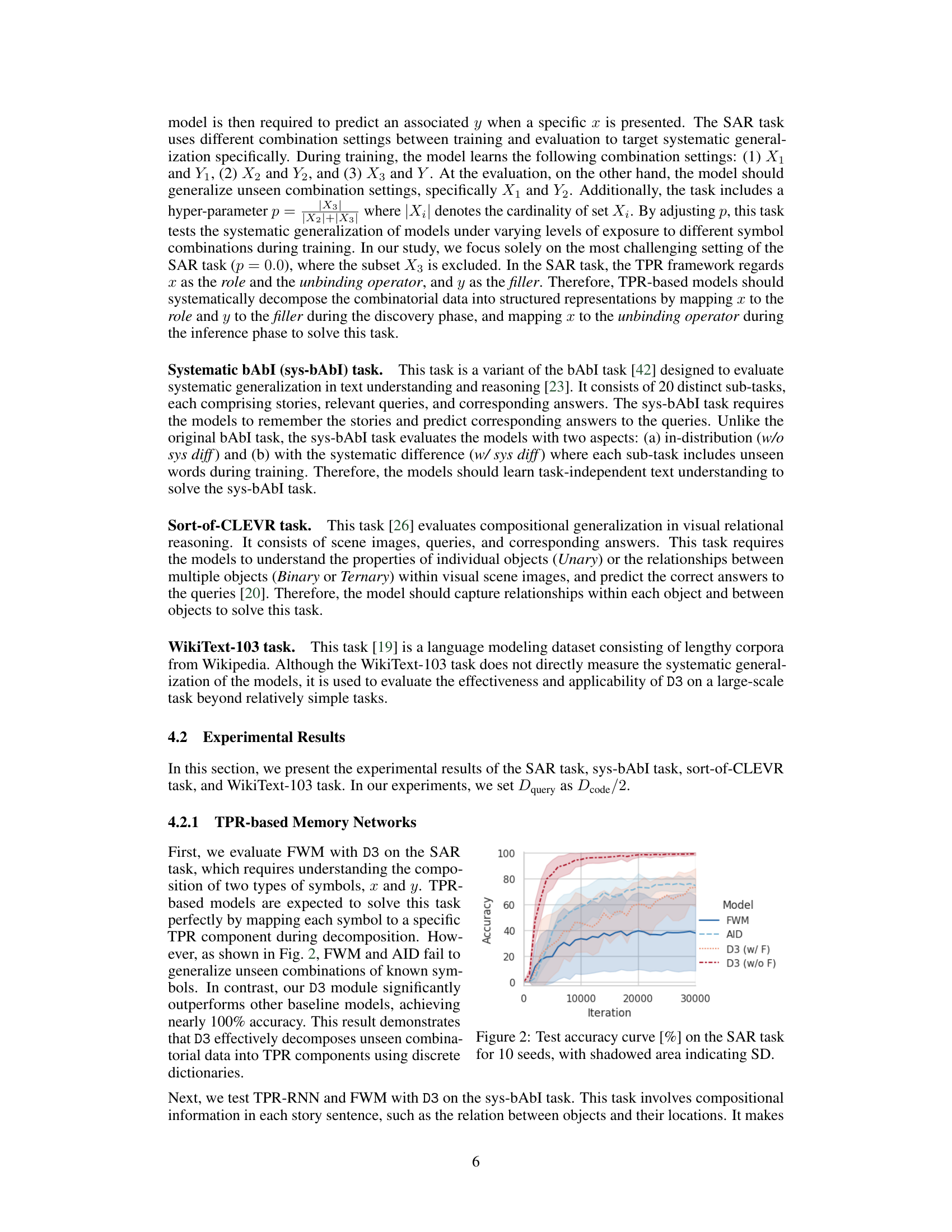

🔼 This figure shows the test accuracy curves for four different models (FWM, AID, D3 (w/ F), and D3 (w/o F)) on the SAR task across 30,000 iterations. The shadowed areas represent the standard deviation across 10 different seeds. The results show that D3 models significantly outperform the FWM and AID models, achieving nearly perfect accuracy. The difference between D3 (w/ F) and D3 (w/o F) suggests the impact of applying D3 to generate filler representations.

read the caption

Figure 2: Test accuracy curve [%] on the SAR task for 10 seeds, with shadowed area indicating SD.

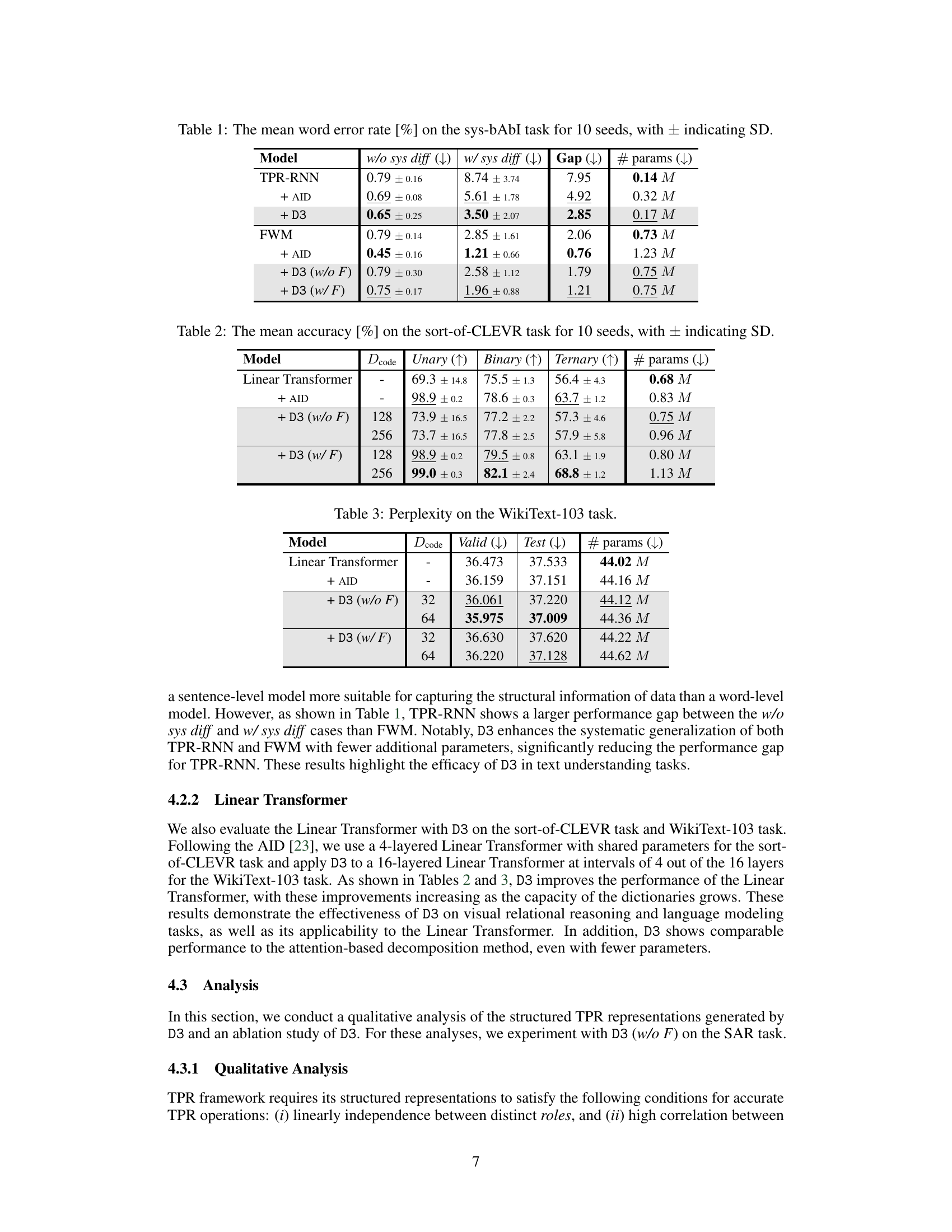

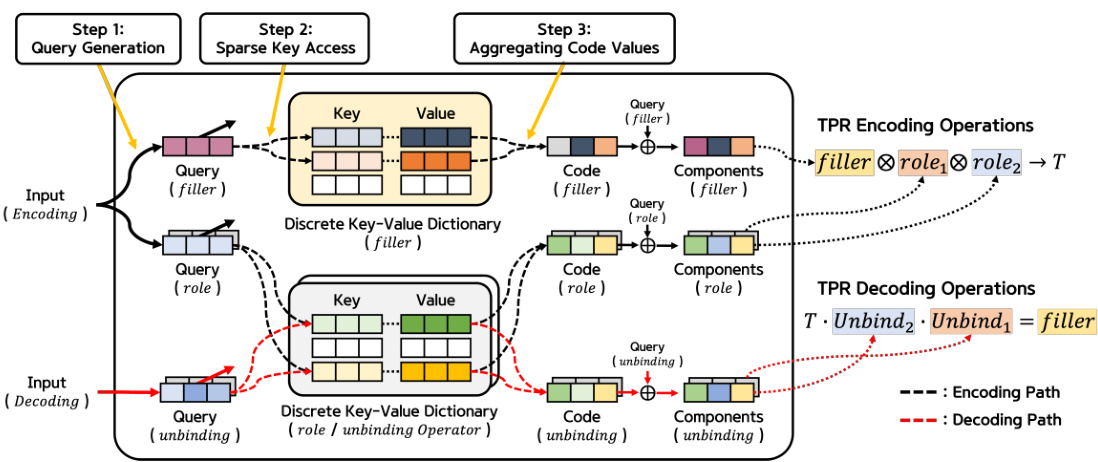

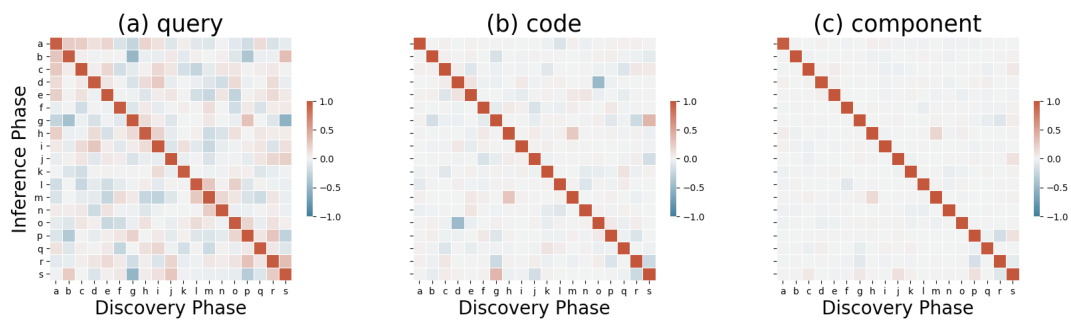

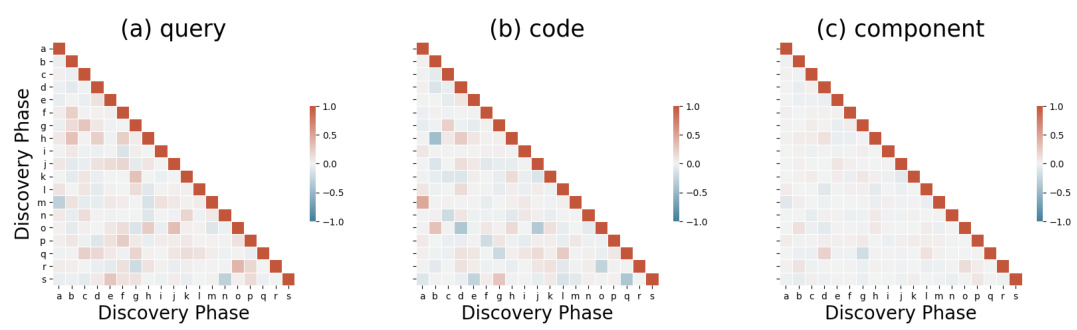

🔼 This figure shows heatmaps visualizing the cosine similarity between different representations generated during the discovery phase of the SAR task. Three heatmaps are presented, each showing the similarity between: (a) Queries of roles (b) Codes of roles (c) The roles themselves The heatmaps help illustrate how the different components of the D3 model (query generation, key access, code aggregation) interact to create structured representations.

read the caption

Figure 3: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles, (b) codes of roles, and (c) the roles themselves.

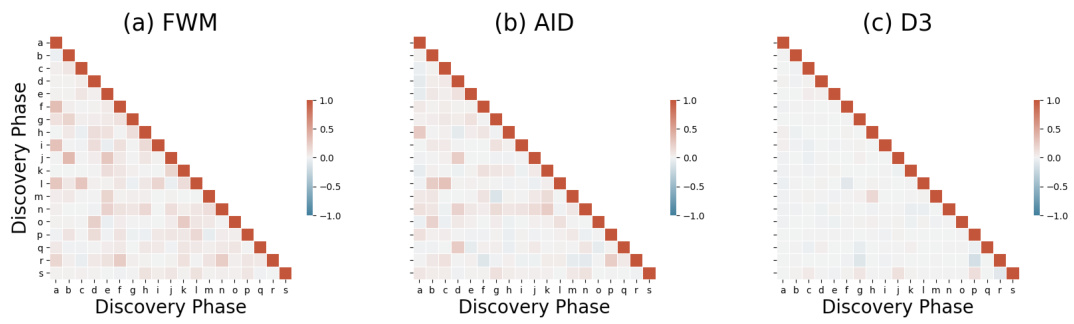

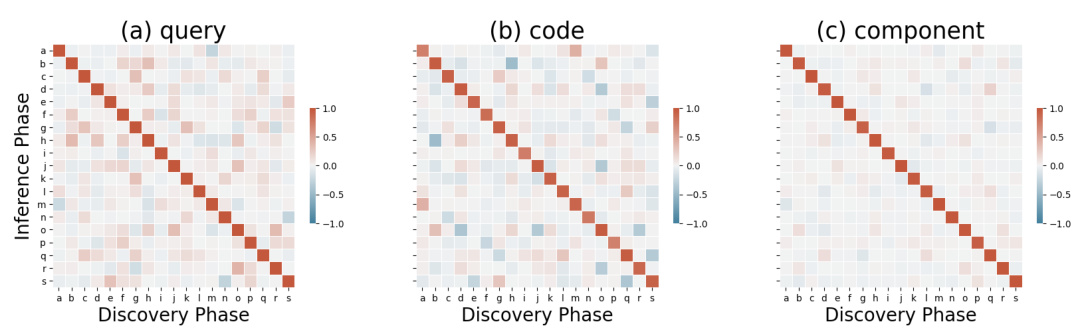

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between representations generated during the discovery and inference phases of the SAR task. It visualizes this similarity for queries, codes, and the actual roles and unbinding operators. The goal is to demonstrate that the learned representations in D3 satisfy the conditions required for accurate TPR operations. A high correlation between roles and unbinding operators is expected, signifying successful decomposition.

read the caption

Figure 4: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase (represented on the x-axis) and the inference phase (represented on the y-axis) for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles and unbinding operators, (b) codes of roles and unbinding operators, and (c) the roles and unbinding operators themselves.

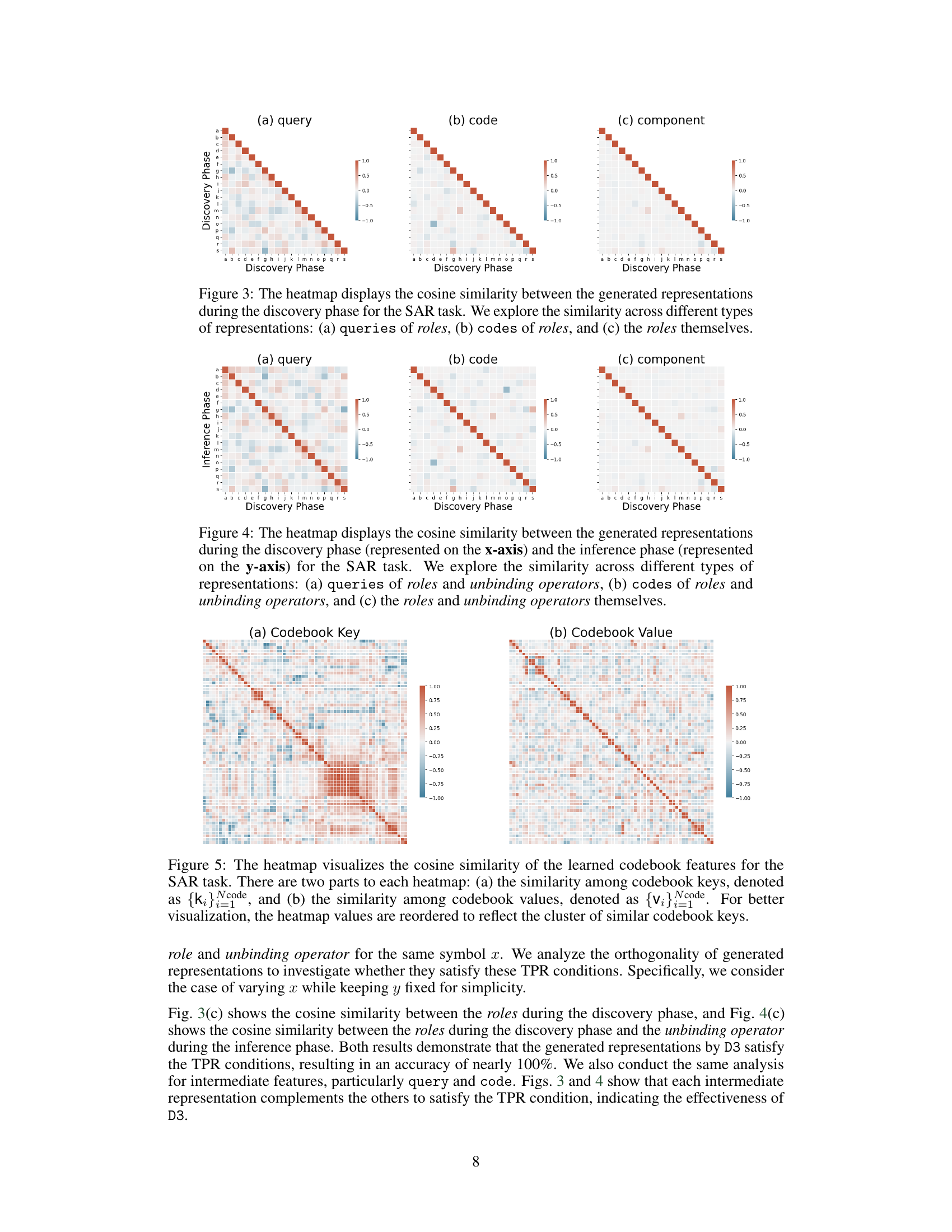

🔼 This figure shows heatmaps visualizing cosine similarity within and between learned codebook keys and values. The left heatmap displays similarity between keys, and the right heatmap shows similarity between values. The ordering of the keys and values has been adjusted to better show clusters of similar features.

read the caption

Figure 5: The heatmap visualizes the cosine similarity of the learned codebook features for the SAR task. There are two parts to each heatmap: (a) the similarity among codebook keys, denoted as {k}code, and (b) the similarity among codebook values, denoted as {v}code. For better visualization, the heatmap values are reordered to reflect the cluster of similar codebook keys.

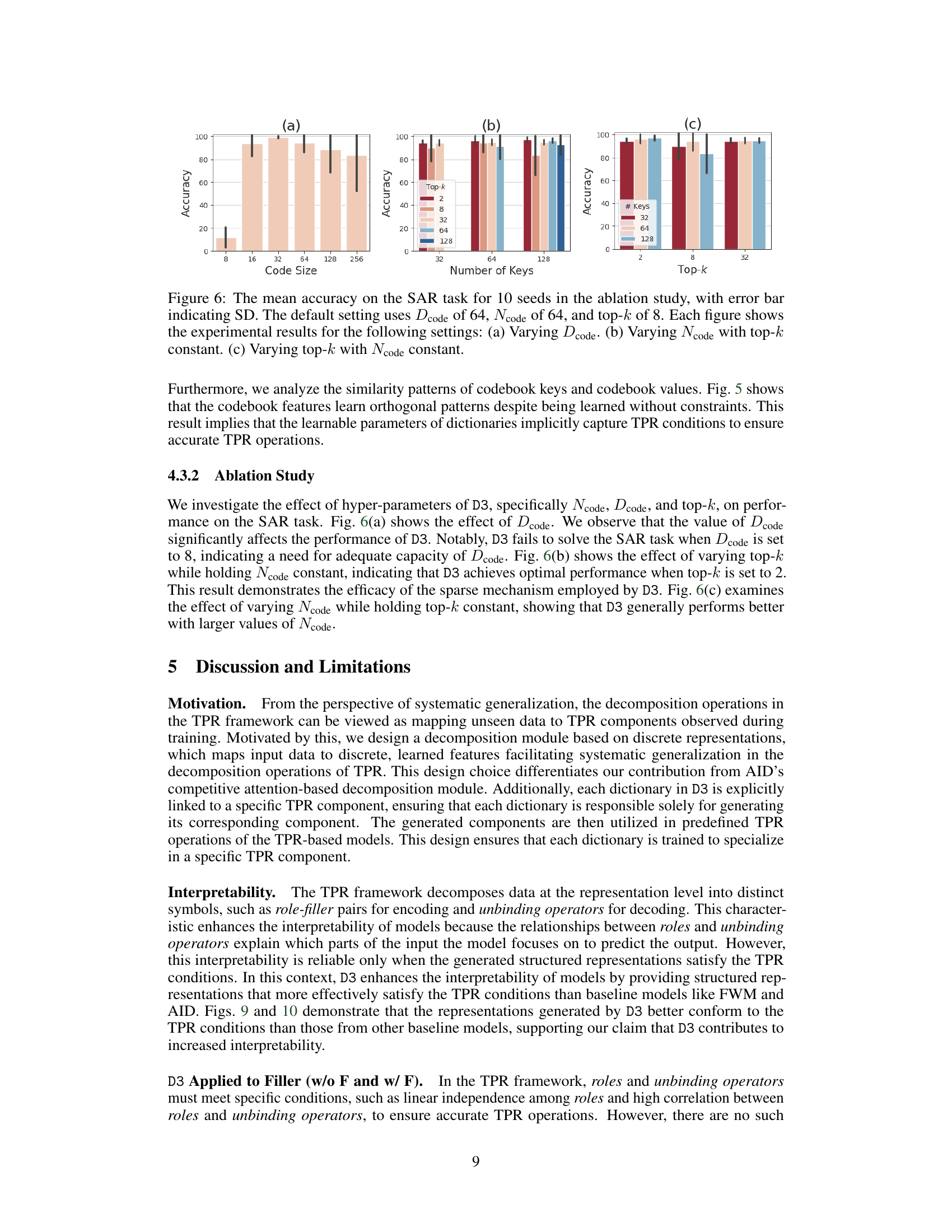

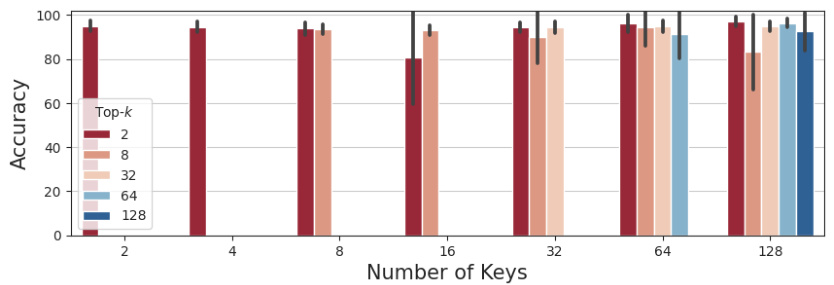

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study on the hyperparameters of the D3 model for the SAR task. It shows the impact of varying the code size (Dcode), the number of keys (Ncode), and the top-k value on the accuracy. The default settings were Dcode=64, Ncode=64, and top-k=8. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) depict the effect of varying each of these parameters individually while keeping the others constant, showing how each parameter affects the model’s performance in systematic generalization.

read the caption

Figure 6: The mean accuracy on the SAR task for 10 seeds in the ablation study, with error bar indicating SD. The default setting uses Dcode of 64, Ncode of 64, and top-k of 8. Each figure shows the experimental results for the following settings: (a) Varying Dcode. (b) Varying Ncode with top-k constant. (c) Varying top-k with Ncode constant.

🔼 This figure presents the ablation study results on the Systematic Associative Recall (SAR) task, investigating the impact of hyperparameters Dcode (codebook dimension), Ncode (number of keys), and top-k (number of selected keys) on the model’s accuracy. The default setting employs Dcode=64, Ncode=64, and top-k=8. The figure shows three subplots: (a) varies Dcode while keeping Ncode and top-k constant; (b) varies Ncode while keeping Dcode and top-k constant; and (c) varies top-k while keeping Dcode and Ncode constant. Each setting’s accuracy is evaluated using 10 different seeds, with error bars showing standard deviations.

read the caption

Figure 6: The mean accuracy on the SAR task for 10 seeds in the ablation study, with error bar indicating SD. The default setting uses Dcode of 64, Ncode of 64, and top-k of 8. Each figure shows the experimental results for the following settings: (a) Varying Dcode. (b) Varying Ncode with top-k constant. (c) Varying top-k with Ncode constant.

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of removing the residual connection from the D3 layer on the SAR and sys-bAbI tasks. The results show a significant performance drop when the residual connection is removed, demonstrating its importance for the effective training of the D3 layer and its contribution to the model’s ability to generalize well on the two tasks.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation study for the effect of the residual connection on (a) the SAR task and (b) the sys-bAbI task for 10 seeds.

🔼 This figure shows heatmaps visualizing the cosine similarity between different types of representations generated during the discovery phase of the SAR task. Three heatmaps are presented, each corresponding to a different representation type: (a) Queries of roles: Similarity between the query vectors generated for different roles. (b) Codes of roles: Similarity between the code vectors obtained from the dictionaries for different roles. (c) Roles themselves: Similarity between the final role representations. The heatmaps help to illustrate how well the different representations align and support the compositionality of the proposed method.

read the caption

Figure 3: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles, (b) codes of roles, and (c) the roles themselves.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Discrete Dictionary-based Decomposition (D3) layer. The D3 layer maps input data to pre-learned symbolic features stored in discrete, learnable dictionaries. Each dictionary is specifically linked to a TPR component (role, filler, or unbinding operator). The figure highlights that D3 uses shared dictionaries for roles and their corresponding unbinding operators, improving efficiency. The process is shown in two stages: encoding (mapping input to TPR components) and decoding (retrieving specific fillers from the combined representation).

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of D3. D3 generates structured TPR representations by mapping input data to the nearest pre-learned symbolic features stored within discrete, learnable dictionaries. Each dictionary is linked explicitly to specific TPR components, such as roles, filler, and unbinding operators. Notably, D3 uses a shared dictionary configuration between the roles and unbinding operators. This figure illustrates, for example, that role₁ and unbind₁ share one dictionary, while role2 and unbind2 share another. T denotes a superimposed representation that represents multiple objects.

🔼 This figure shows three heatmaps visualizing cosine similarity between different representations generated during the discovery phase of the SAR task. Each heatmap represents a different aspect of the generated representations: (a) queries of roles, (b) codes of roles, and (c) the roles themselves. The heatmaps provide a visual representation of how similar different parts of the generated representations are to each other.

read the caption

Figure 3: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles, (b) codes of roles, and (c) the roles themselves.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between the generated representations in the discovery and inference phases for the SAR task. It uses heatmaps to visualize the similarity for three different representation types: queries of roles and unbinding operators, their corresponding codes, and the roles and unbinding operators themselves. This helps to understand how the D3 layer generates structured representations that satisfy the necessary conditions for accurate TPR operations.

read the caption

Figure 4: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase (represented on the x-axis) and the inference phase (represented on the y-axis) for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles and unbinding operators, (b) codes of roles and unbinding operators, and (c) the roles and unbinding operators themselves.

🔼 This figure shows heatmaps visualizing the cosine similarity within the learned codebook features used in the Discrete Dictionary-based Decomposition (D3) layer for the SAR task. The left heatmap (a) displays the similarity between different codebook keys (k), while the right heatmap (b) displays the similarity between different codebook values (v). The values are reordered to highlight clusters of similar keys and values, making the patterns more apparent.

read the caption

Figure 5: The heatmap visualizes the cosine similarity of the learned codebook features for the SAR task. There are two parts to each heatmap: (a) the similarity among codebook keys, denoted as {k}code, and (b) the similarity among codebook values, denoted as {v}code. For better visualization, the heatmap values are reordered to reflect the cluster of similar codebook keys.

🔼 This figure shows heatmaps illustrating cosine similarity between different representation types generated during the discovery phase of the Systematic Associative Recall (SAR) task. Three heatmaps are presented, each focusing on a different aspect: (a) query: Shows similarity between the query vectors for each role. (b) code: Displays similarity between the code vectors derived from the key-value dictionaries for each role. (c) component: Illustrates the similarity between the final role representations generated after the aggregation of code values. The heatmaps visually demonstrate how the D3 layer maps input data (queries) to pre-learned symbolic features (codes) within dictionaries to generate structured TPR representations (components) for different roles in the SAR task.

read the caption

Figure 3: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles, (b) codes of roles, and (c) the roles themselves.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between representations generated during the discovery and inference phases of the SAR task. It displays three subplots. The first (a) shows the similarity between queries (input data mapped to represent roles and unbinding operators) in the discovery and inference phases. The second (b) does the same but for the codes (intermediate feature vectors representing roles and unbinding operators). The third (c) displays the similarity between the actual roles and unbinding operators themselves. The purpose is to illustrate that D3 generates representations that satisfy the requirements of the TPR framework for accurate TPR operations.

read the caption

Figure 4: The heatmap displays the cosine similarity between the generated representations during the discovery phase (represented on the x-axis) and the inference phase (represented on the y-axis) for the SAR task. We explore the similarity across different types of representations: (a) queries of roles and unbinding operators, (b) codes of roles and unbinding operators, and (c) the roles and unbinding operators themselves.

🔼 This figure shows two heatmaps visualizing the cosine similarity within the learned codebook keys and values used in the D3 model for the SAR task. Heatmap (a) displays the similarity between different codebook keys, while heatmap (b) shows the similarity between corresponding codebook values. The values have been reordered to emphasize clusters of similar features.

read the caption

Figure 5: The heatmap visualizes the cosine similarity of the learned codebook features for the SAR task. There are two parts to each heatmap: (a) the similarity among codebook keys, denoted as {k}code, and (b) the similarity among codebook values, denoted as {v}code. For better visualization, the heatmap values are reordered to reflect the cluster of similar codebook keys.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the mean accuracy and standard deviation of the Linear Transformer model and its variants (with AID and D3) on the sort-of-CLEVR task. The results are broken down by the type of reasoning required (Unary, Binary, Ternary) and the number of parameters in the model. Different Dcode values (128 and 256) are tested for the D3 models, and the results with and without D3 applied to the filler (w/ F, w/o F) are shown separately.

read the caption

Table 2: The mean accuracy [%] on the sort-of-CLEVR task for 10 seeds, with ± indicating SD.

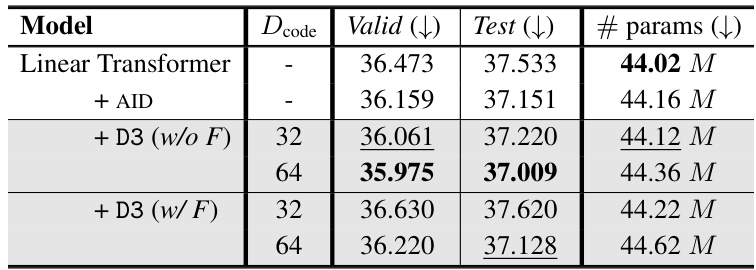

🔼 This table presents the perplexity scores achieved by different models on the WikiText-103 language modeling task. The models compared include the Linear Transformer baseline, the Linear Transformer with the AID module, and the Linear Transformer with the proposed D3 module (with and without applying D3 to filler generation). The table shows perplexity scores on both validation and test sets, and for different D3 configurations in terms of codebook size (Dcode). Lower perplexity indicates better performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Perplexity on the WikiText-103 task.

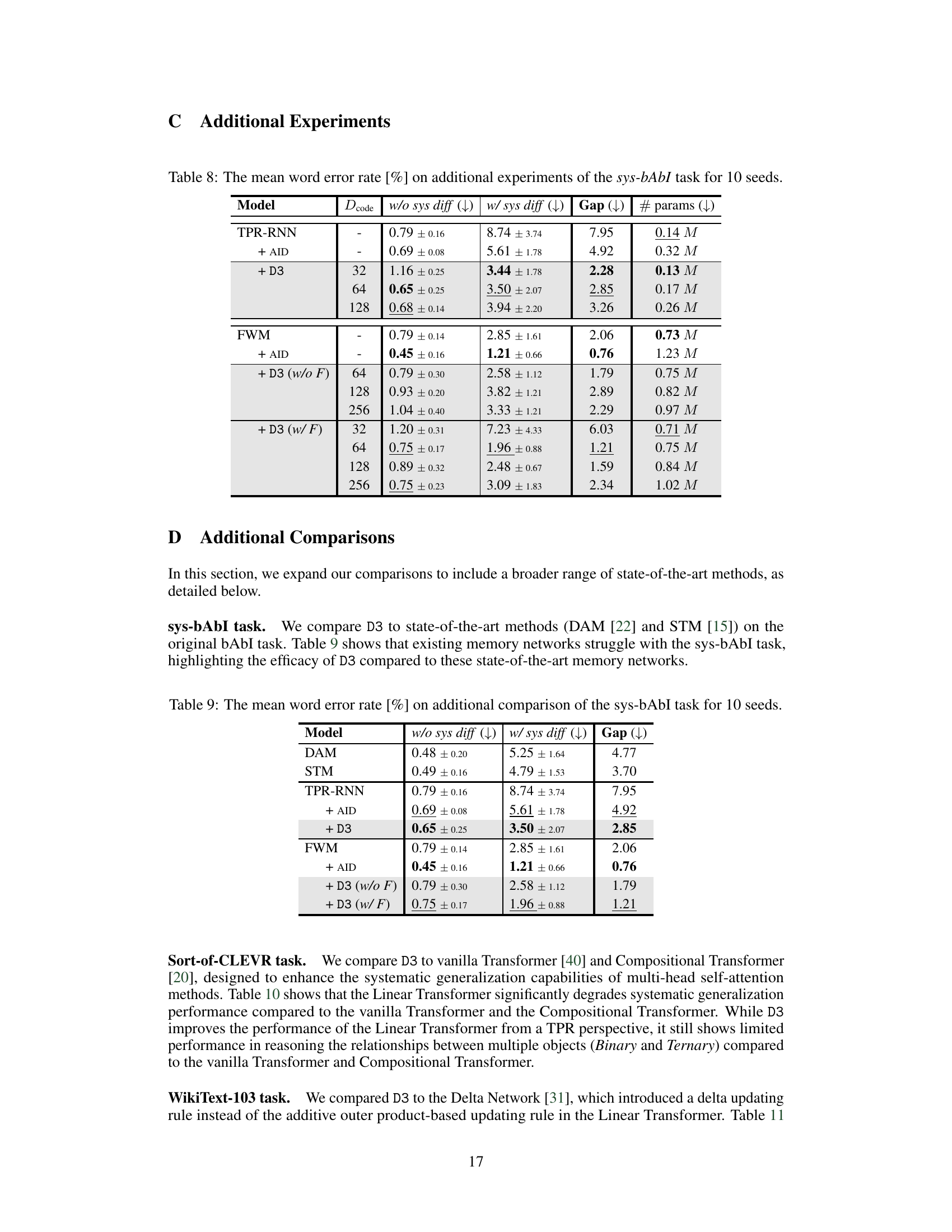

🔼 This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the proposed Discrete Dictionary-based Decomposition (D3) layer in the experiments conducted on four different tasks: SAR, sys-bAbI, Sort-of-CLEVR, and WikiText-103. For each task, it specifies the range of values explored for the code dimension (Dcode), the number of codebook entries (Ncode), the query dimension (Dquery), the number of top-k keys selected during sparse key access, and the dropout probability (Pdropout). Note that Dquery is dynamically determined as half the size of Dcode. The table illustrates the choices made in adjusting these parameters for optimal performance on each specific task.

read the caption

Table 4: Hyper-parameter settings of the D3.

🔼 This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the TPR-RNN model in the experiments. It specifies the dimensions of the entity and relation components (Dentity and Drelation), the number of encoding components (Nenc), and the number of decoding components (Ndec). These parameters control the model’s architecture and capacity for processing sequential data in the sys-bAbI task.

read the caption

Table 5: Hyper-parameters of TPR-RNN.

🔼 This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the Fast Weight Memory (FWM) model in the experiments. It lists the dimensions of the LSTM layer (DLSTM), the FWM component (DFWM), the number of reads (Nreads), encoding components (Nenc), and decoding components (Ndec) for both the SAR and sys-bAbI tasks. The numbers of components depend on the number of reads, reflecting the model’s dynamic memory operations.

read the caption

Table 6: Hyper-parameters of FWM.

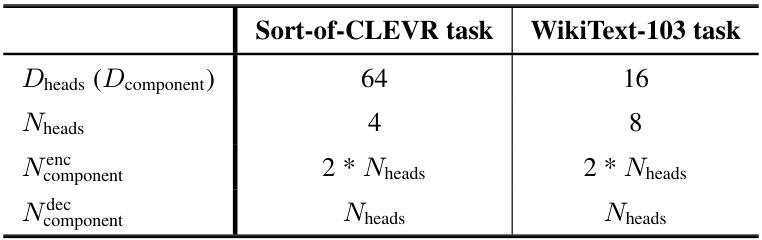

🔼 This table shows the hyperparameter settings for the Linear Transformer model used in the experiments for the Sort-of-CLEVR and WikiText-103 tasks. It specifies the dimensions of the heads (Dheads, which is equivalent to Dcomponent), the number of heads (Nheads), the number of encoding components (Nenc_component), and the number of decoding components (Ndec_component). Note that the number of encoding and decoding components are both set to twice the number of heads.

read the caption

Table 7: Hyper-parameters of Linear Transformer.

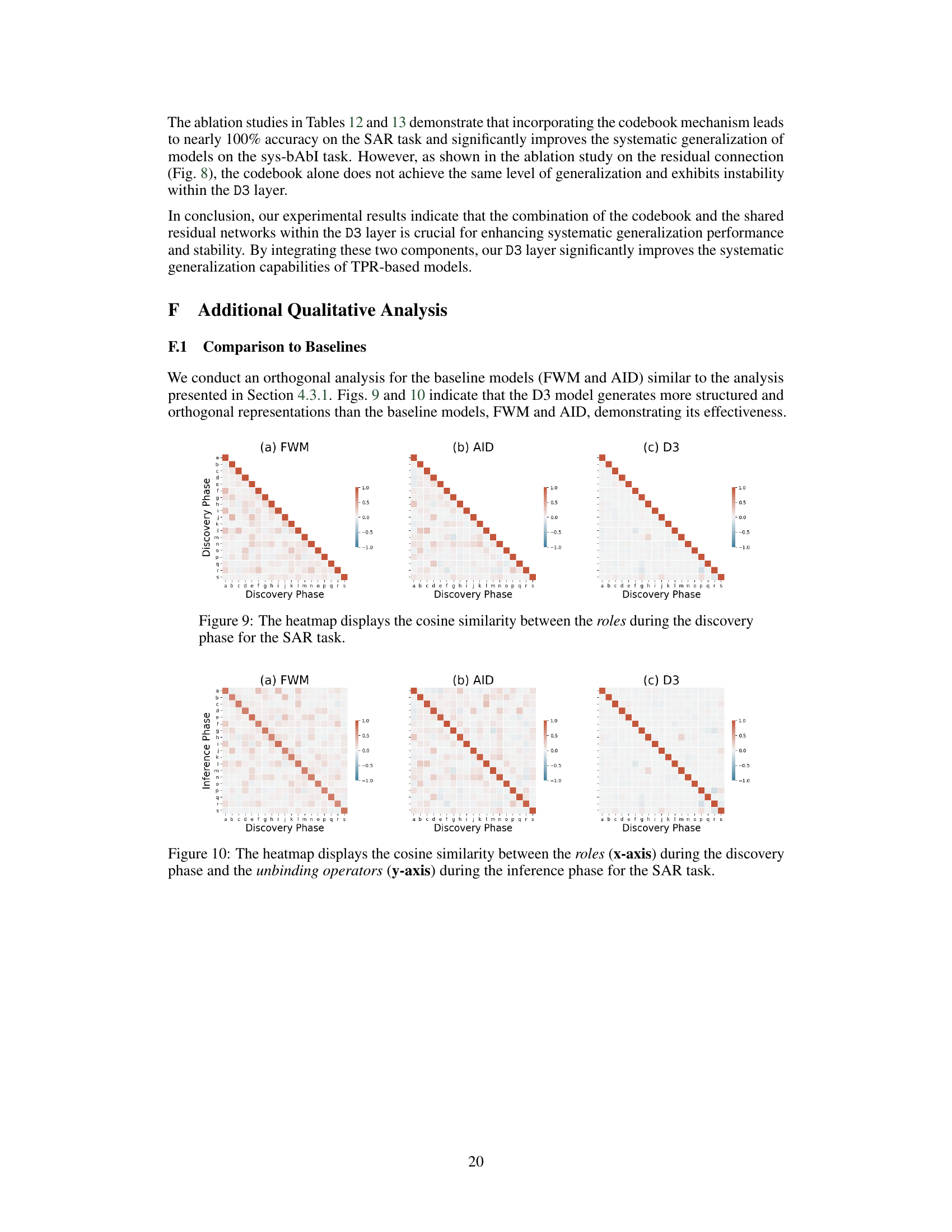

🔼 This table presents the results of the sys-bAbI experiment. It compares different models (TPR-RNN, FWM, and their variations with AID and D3) on two conditions: with and without systematic differences in the training data. The table shows the mean word error rate (%), standard deviation, the difference between the two conditions (Gap), and the number of parameters for each model. Lower word error rate and gap values indicate better performance. This showcases the ability of D3 to improve the systematic generalization of TPR-based models.

read the caption

Table 1: The mean word error rate [%] on the sys-bAbI task for 10 seeds, with ± indicating SD.

🔼 This table presents the results of the sys-bAbI experiment. It shows the mean word error rate and standard deviation for different models on two conditions: with and without systematic differences. The models compared include TPR-RNN, TPR-RNN with AID, TPR-RNN with D3, FWM, FWM with AID, FWM with D3 (without filler), and FWM with D3 (with filler). The table also indicates the difference in error rates between the two conditions (Gap) and the number of parameters for each model.

read the caption

Table 1: The mean word error rate [%] on the sys-bAbI task for 10 seeds, with ± indicating SD.

🔼 This table presents the mean accuracy and standard deviation achieved by different models on the sort-of-CLEVR task. The models tested include a baseline Linear Transformer, the same model augmented with AID (Attention-based Iterative Decomposition), and the model with the proposed D3 layer (with and without filler generation). The table shows results for three different levels of complexity in the task (Unary, Binary, and Ternary) and also shows the number of parameters used by each model. Different values for Dcode (dimension of the codebook) are also tested for the D3 models.

read the caption

Table 2: The mean accuracy [%] on the sort-of-CLEVR task for 10 seeds, with ± indicating SD.

🔼 This table presents the perplexity scores achieved by different models on the WikiText-103 task, a benchmark for language modeling. The models compared include a Linear Transformer baseline, the same model enhanced with the AID (Attention-based Iterative Decomposition) module, and the Linear Transformer with the proposed D3 (Discrete Dictionary-based Decomposition) layer, both with and without D3 applied to filler generation. The table shows the perplexity scores for both the validation and test sets, and also shows the model’s parameters. This allows for comparison of performance and parameter efficiency across the models.

read the caption

Table 3: Perplexity on the WikiText-103 task.

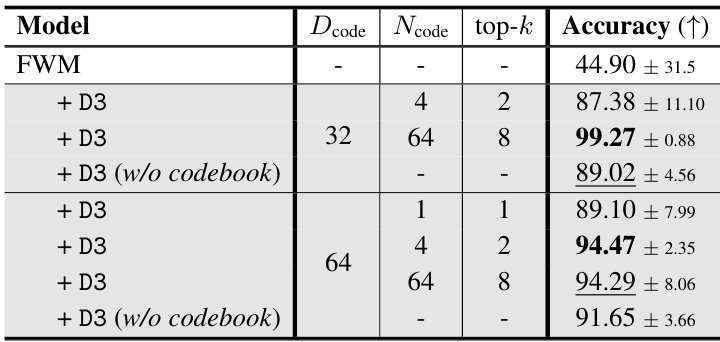

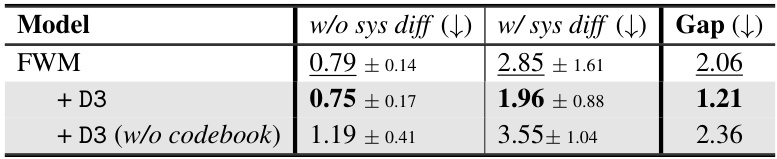

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the SAR task, investigating the impact of removing the codebook from the D3 layer. It shows the accuracy achieved by the baseline FWM model and several variations of the D3 model, including those with different numbers of codebook keys (Ncode) and those without a codebook. The results highlight the importance of the codebook in achieving high accuracy, particularly in the case of unseen combinatorial data.

read the caption

Table 12: Ablation study for the effect of the codebook on the SAR task for 10 seeds.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different models on the systematic bAbI (sys-bAbI) task, specifically focusing on the word error rate. It compares the baseline TPR-RNN and FWM models against versions incorporating the AID and D3 layers, both with and without the filler being processed by D3. The results are broken down for in-distribution (without systematic differences) and out-of-distribution (with systematic differences) scenarios, highlighting the generalization ability of each model. The ‘Gap’ column shows the difference in error rate between the in-distribution and out-of-distribution settings, indicating the model’s robustness to unseen data, while ‘#params’ reflects the number of model parameters used.

read the caption

Table 1: The mean word error rate [%] on the sys-bAbI task for 10 seeds, with ± indicating SD.

Full paper#