↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Geographical districting, crucial for logistics and resource allocation, is computationally hard to solve optimally using traditional methods. Existing heuristics often yield suboptimal results, especially for large geographical areas. This paper addresses these limitations by proposing a novel method.

DISTRICTNET integrates a combinatorial optimization layer (Capacitated Minimum Spanning Tree problem) with a graph neural network architecture. It uses a decision-aware training approach, embedding target solutions in a suitable space and learning from them. Experiments show that DISTRICTNET significantly reduces costs compared to existing methods and generalizes well to various city sizes and parameters.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in optimization, machine learning, and geographic information systems because it introduces a novel structured learning approach that significantly outperforms existing methods for solving real-world districting problems. Its successful integration of a combinatorial optimization layer with a graph neural network offers a new paradigm for tackling complex combinatorial problems, and its demonstrated generalizability across various city sizes and parameters opens exciting new avenues for further research and application in related fields.

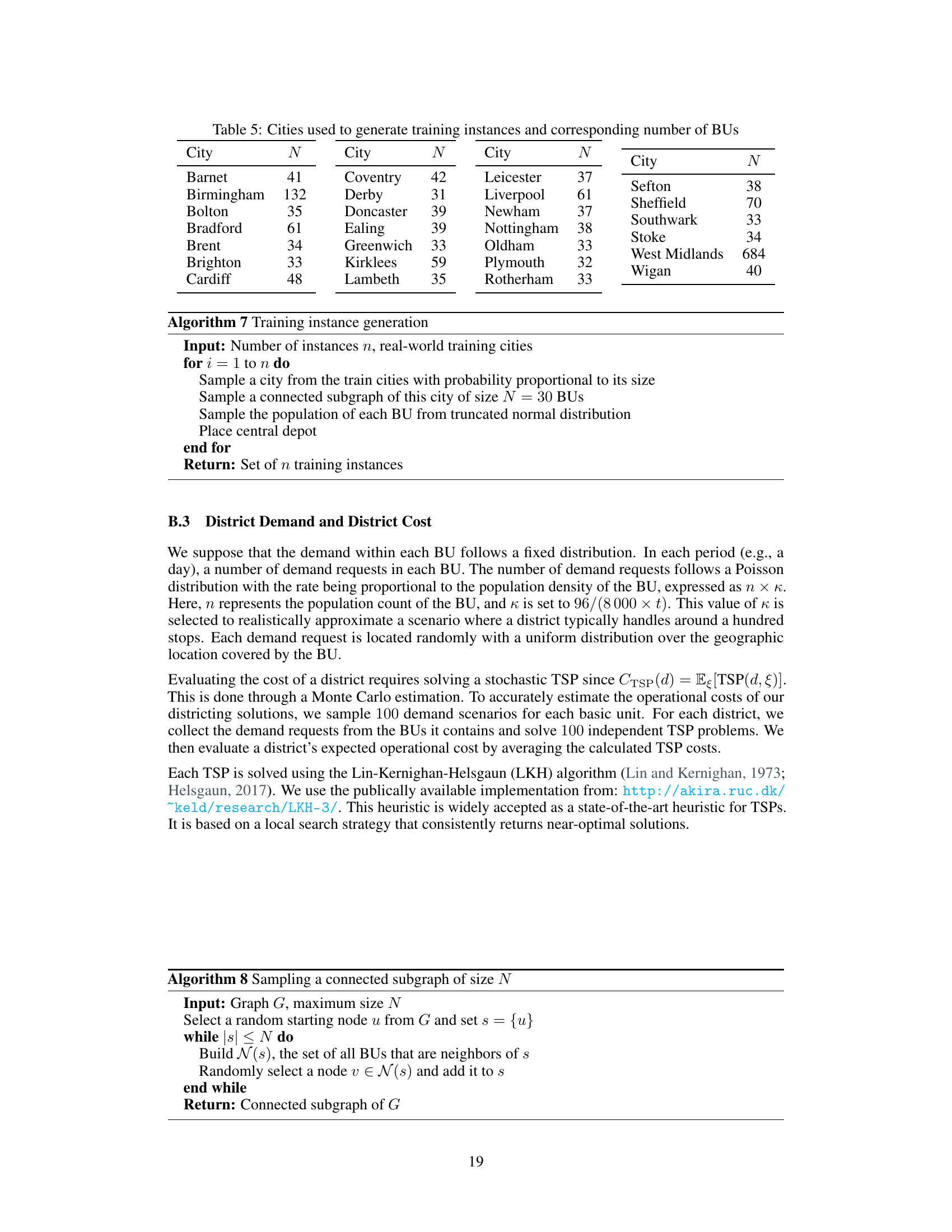

Visual Insights#

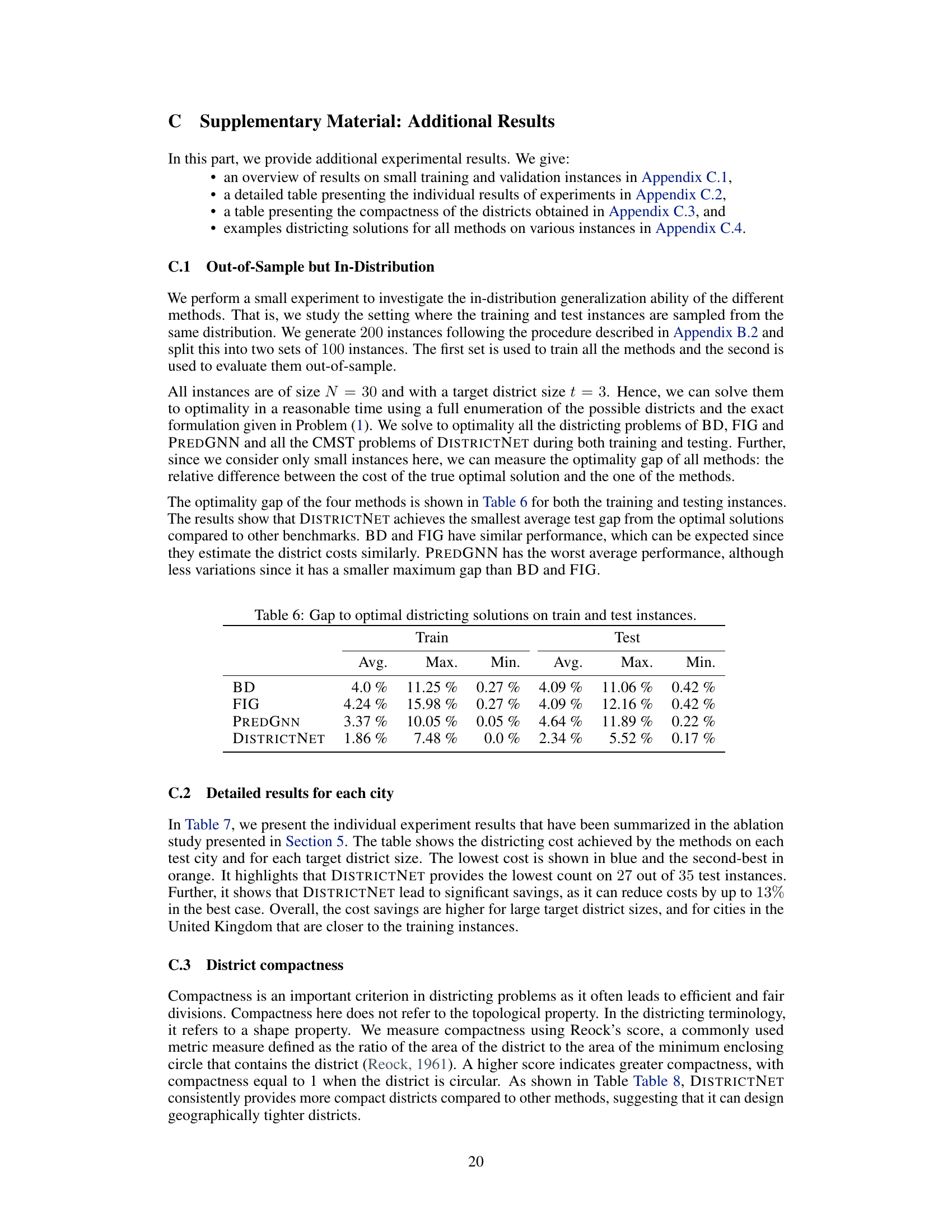

This figure illustrates the DISTRICTNET architecture. A graph instance (x) is fed into a Graph Neural Network (GNN) which outputs a vector of edge weights (θ). These weights define a Capacitated Minimum Spanning Tree (CMST) problem that’s solved by a solver. The CMST solution (ŷ) is then decoded into a districting solution (λ). The whole pipeline is trained in a decision-aware manner, meaning that the loss gradient is propagated back to the GNN to improve its predictions.

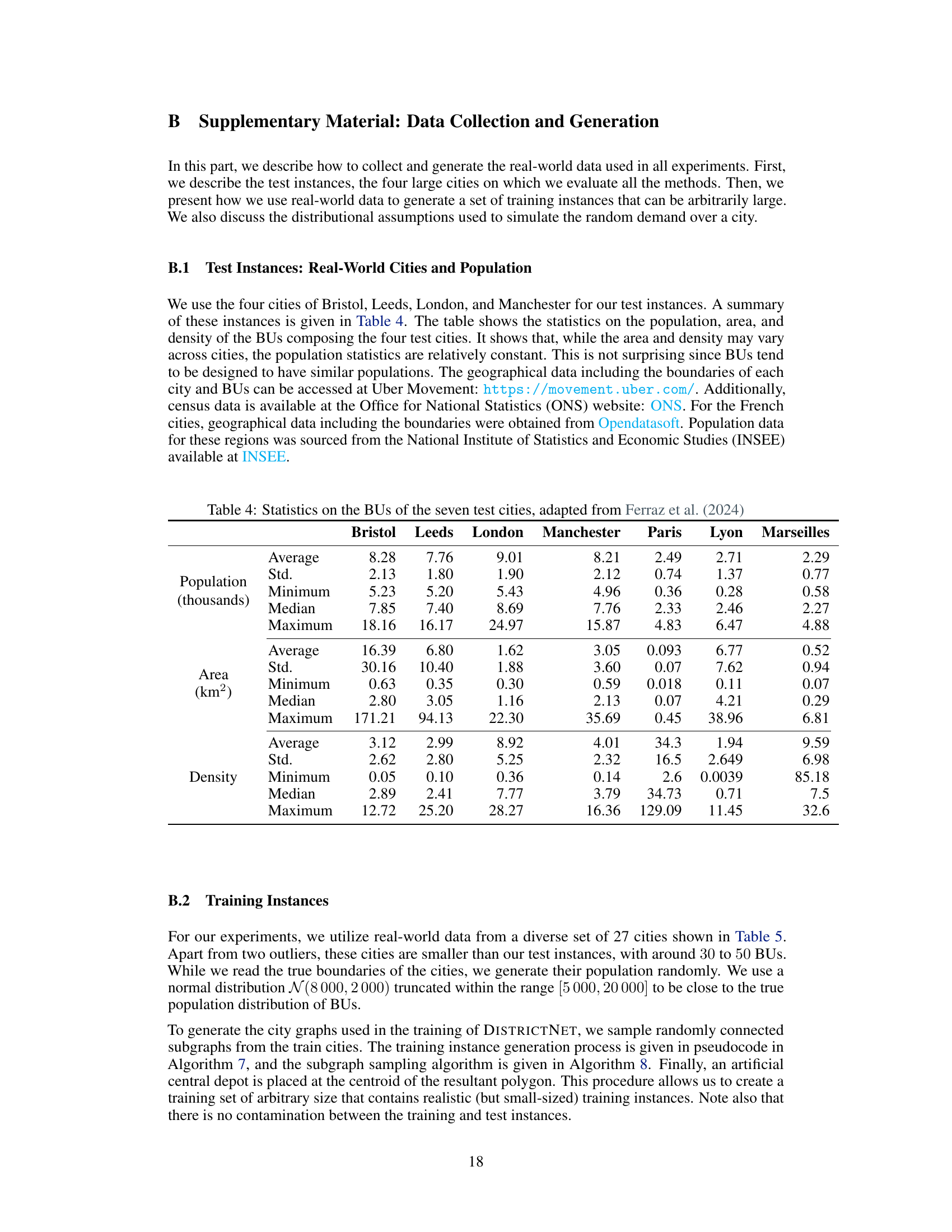

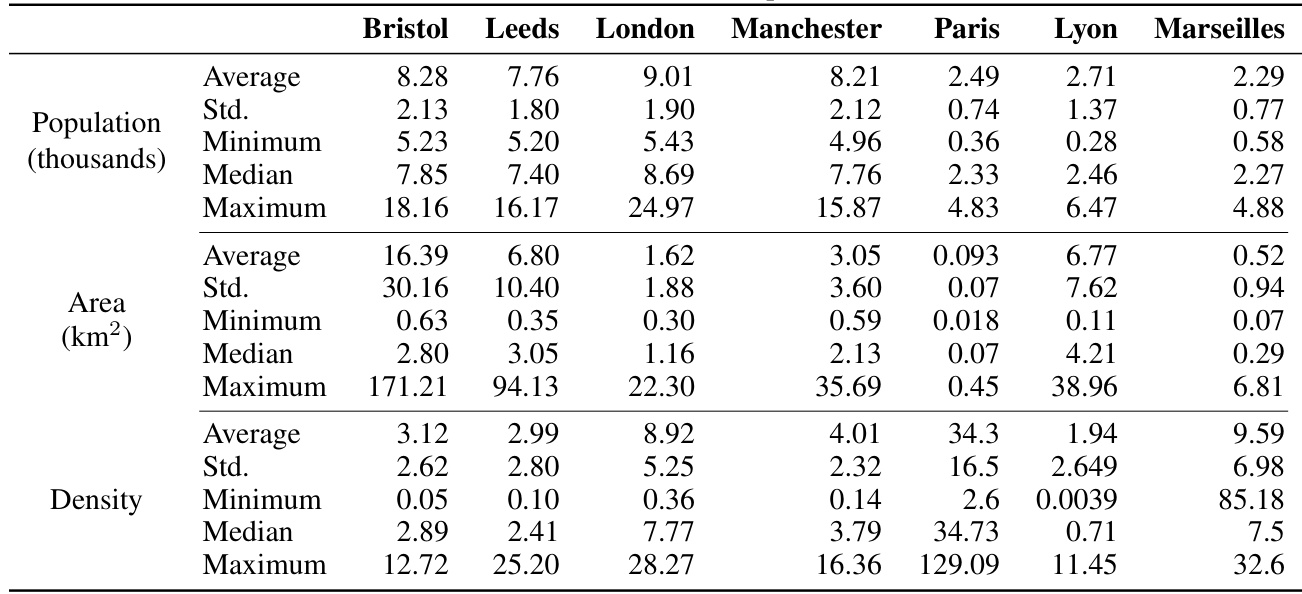

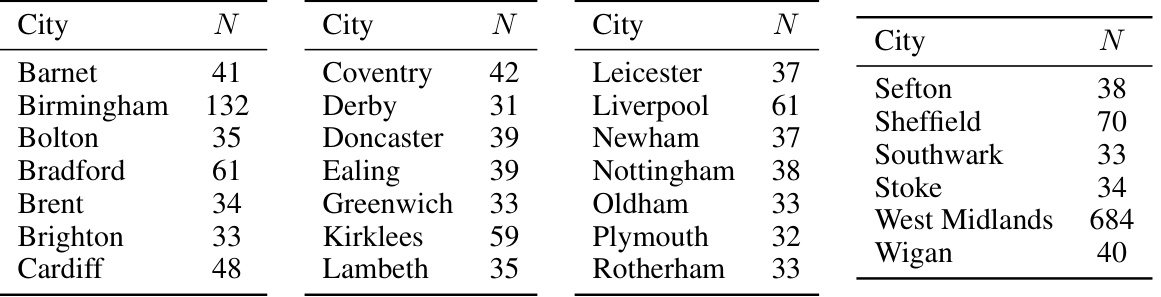

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of DISTRICTNET against four benchmark methods on a set of 35 test instances with varying target district sizes. The benchmarks include linear regression models (BD and FIG), an unstructured learning approach with GNN (PREDGNN), and a deterministic approximation (AVGTSP). The average relative cost and p-values of the Wilcoxon test are provided to assess the statistical significance of the results. The table demonstrates that DISTRICTNET consistently outperforms the benchmarks, showcasing the effectiveness of its structured learning approach.

In-depth insights#

CMST Surrogate#

The core idea of using a CMST (Capacitated Minimum Spanning Tree) as a surrogate for the complex geographical districting problem is a clever simplification that significantly improves tractability. The CMST, while still NP-hard, offers a structured, easier-to-optimize representation of the districting problem that captures key characteristics like connectivity and capacity constraints. By using a GNN to predict CMST edge weights and then solving the CMST optimally or heuristically, the approach cleverly leverages the strengths of both deep learning and combinatorial optimization. The surjection from the space of districting solutions to CMST solutions ensures that an optimal CMST solution will always correspond to at least one feasible and potentially optimal districting solution. The effectiveness of this surrogate is further highlighted by the successful generalization of the model to out-of-distribution problems with different parameters and geographical areas, demonstrating the power of the learning approach to capture underlying problem structure rather than simply memorizing specific instances.

Decision-aware GNN#

A decision-aware GNN integrates a combinatorial optimization layer into a graph neural network (GNN) architecture. This approach is particularly well-suited for problems where finding optimal solutions is computationally expensive, such as geographical districting. By incorporating the optimization layer, the GNN learns to directly predict high-quality solutions, rather than simply estimating costs. The decision-aware aspect is crucial for training, as it allows learning from optimal or near-optimal solutions, which are often difficult to obtain for complex problems. The CMST (Capacitated Minimum Spanning Tree) is used as a surrogate problem, simplifying the optimization while preserving structural characteristics relevant to the original problem. This surrogate allows the model to generalize well to larger instances. A key contribution is embedding CMST solutions into a suitable space to construct meaningful target solutions for training the GNN. The use of a Fenchel-Young loss further enhances training efficiency and robustness. The results demonstrate significant improvements compared to traditional cost estimation methods, highlighting the power of a decision-aware approach for learning optimal solutions to complex combinatorial problems.

Generalization Limits#

A critical aspect of any machine learning model is its ability to generalize to unseen data. Generalization limits explore the boundaries of this capability. For a model trained on a specific geographical area and population distribution for districting, limitations arise from extrapolation to different geographical contexts. The model might struggle with diverse urban planning structures, population densities, or road networks significantly different from its training data. Another key constraint is the size and structure of the input data: the model may fail to accurately generate appropriate districts if the number of basic units (BUs) or the connections between them differ substantially from the training examples. Further limitations exist in transferring the model to other applications like sales territory design or school zoning, which have their own unique constraints and requirements. The assumption of stationary demand in districting and routing is also a limitation. Real-world demand is dynamic and may change over time and this affects the model’s performance in long-term strategic decision making. Finally, the cost functions involved are complex approximations and model’s ability to capture these accurately limits its robustness.

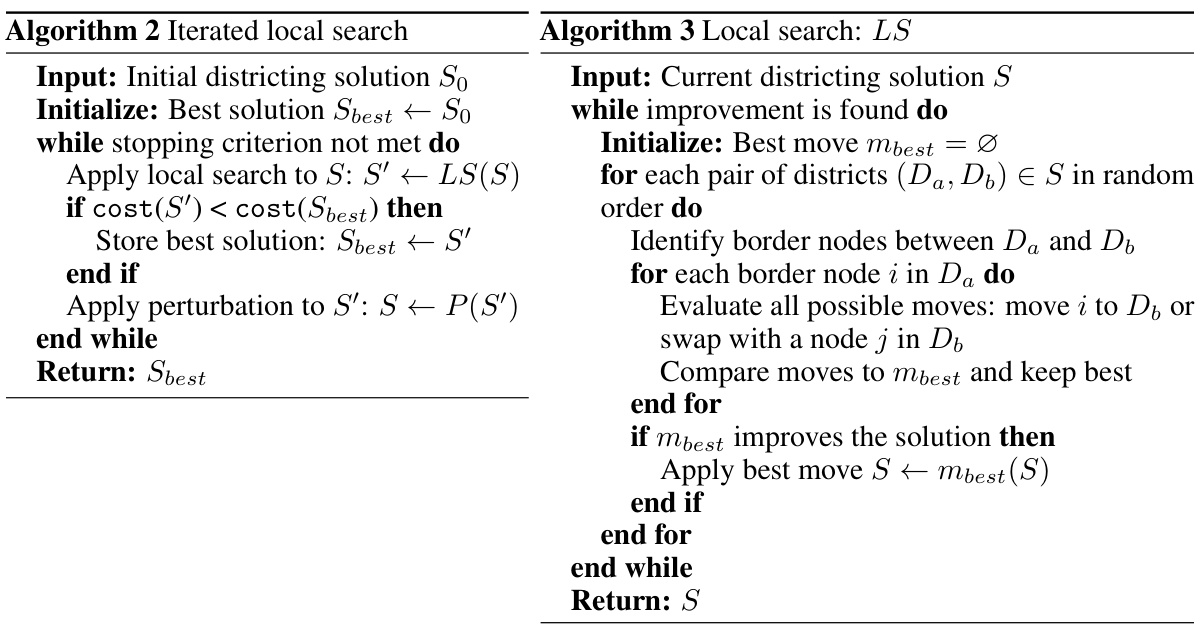

Scalability & ILS#

The scalability of the proposed approach is a critical aspect, especially considering the inherent complexity of districting problems. Iterated Local Search (ILS), while effective for smaller instances, faces challenges when handling large-scale problems with numerous basic units (BUs). The paper highlights the use of a surrogate optimization problem, the capacitated minimum spanning tree (CMST), to mitigate this complexity. The CMST significantly reduces the computational burden, allowing the algorithm to handle larger instances. However, the effectiveness of this approach hinges on the GNN’s ability to accurately parameterize the CMST, requiring sufficient training data and a well-designed model architecture to ensure that the simpler CMST effectively represents the more intricate districting problem. Generalization capabilities are essential for handling diverse real-world scenarios, implying a need for robust training that captures variations in city structures and problem parameters. While the paper demonstrates improved scalability using this approach, a detailed analysis of the computational cost scaling with problem size would strengthen the findings.

Future Extensions#

Future work could explore several promising avenues. Improving the CMST solver is crucial; while the current approach uses an exact solver for small instances and ILS for larger ones, more sophisticated techniques like branch-and-bound or approximation algorithms could yield significant speedups and potentially better solutions. Expanding the feature set used by the GNN to incorporate additional spatial, demographic, or social factors could enhance predictive accuracy. Addressing the stochastic nature of demand more directly, perhaps through more advanced sampling strategies or by modeling demand as a time series, may enhance the realism of the results. Finally, applying DISTRICTNET to other geographical partitioning problems beyond districting and routing, such as school zoning or electoral districting, would demonstrate its broader applicability and robustness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

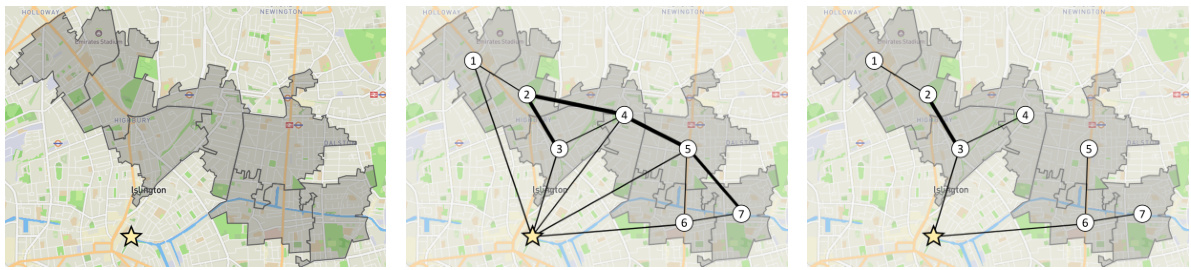

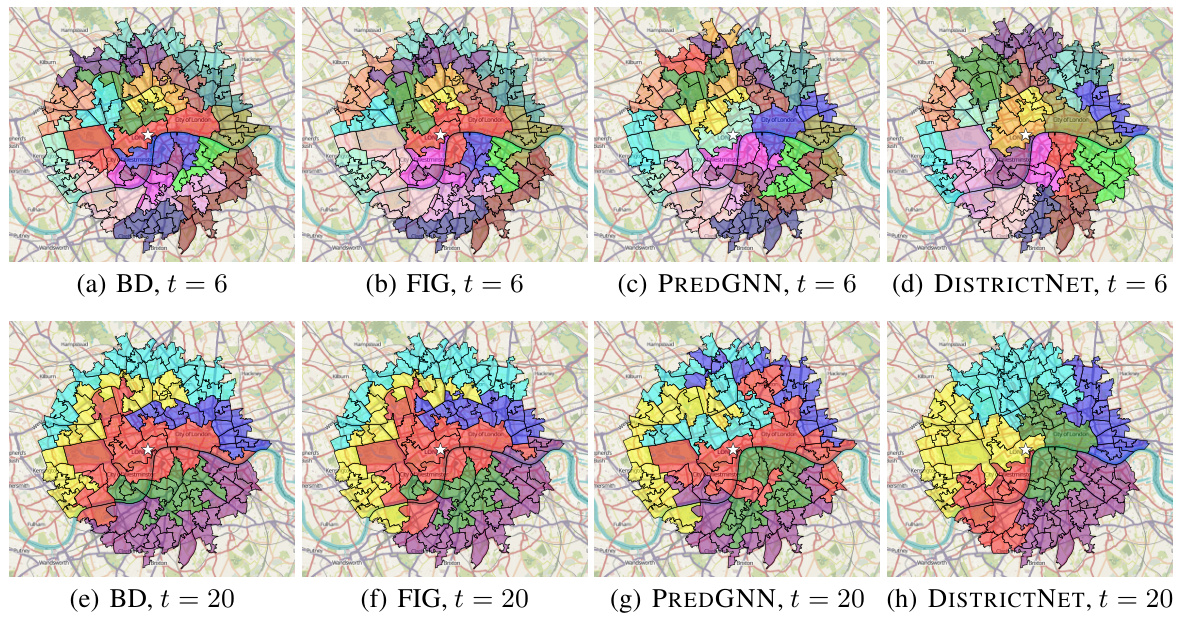

This figure compares the districting solutions produced by four different methods (BD, FIG, PREDGNN, and DISTRICTNET) for the city of Manchester. Each method aims to divide the city into districts, with a target size of 20 basic units (BUs). The resulting district shapes and their spatial distribution differ significantly between the methods, showcasing the varied approaches used in solving the geographical districting problem. The white star in each image represents the depot.

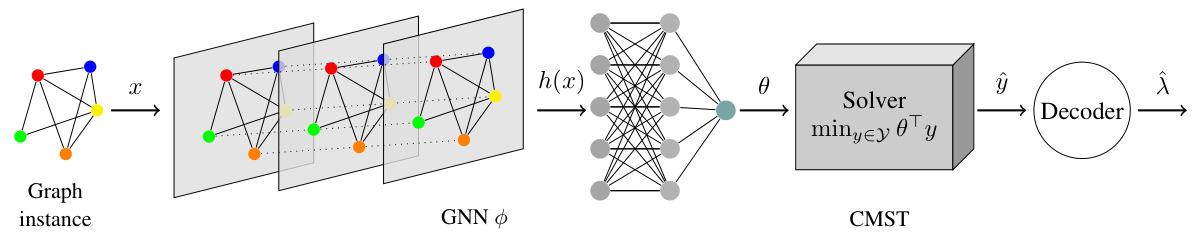

This figure compares the performance of different districting methods against DISTRICTNET for various city sizes, keeping the target district size constant at 20. The y-axis shows the relative cost of each method compared to DISTRICTNET (100%). Values above 100% indicate that the benchmark method performed worse than DISTRICTNET. The x-axis represents the number of BUs (city size). The graph shows how the relative performance of different methods changes as the size of the city increases. This illustrates the generalization ability and scalability of DISTRICTNET for larger instances.

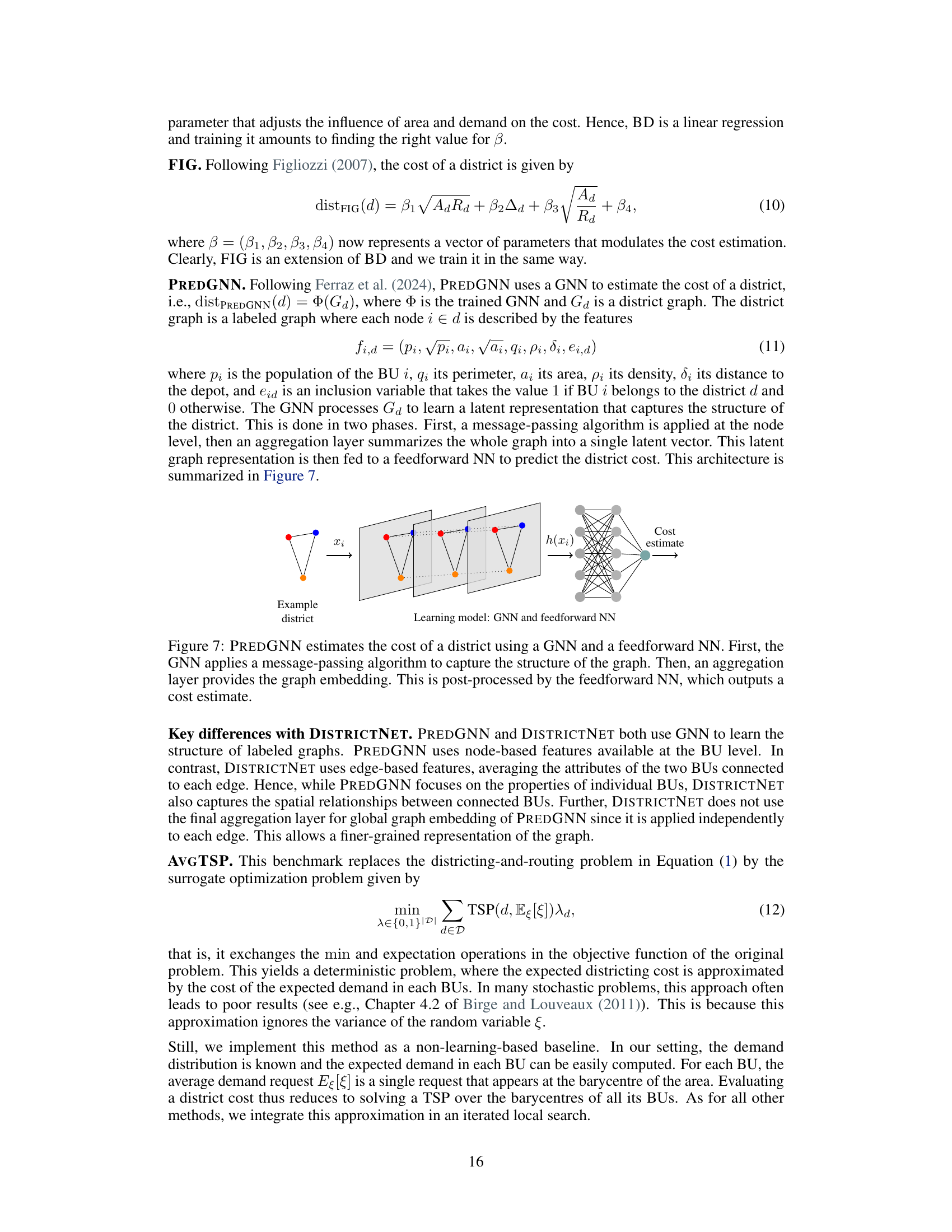

This figure shows box plots of the distribution of district costs for various target district sizes (t) across three different cities: Bristol, Leeds, and London. Each box plot represents the distribution of costs for a specific target size, with the median indicated by the line inside the box, and the interquartile range represented by the box itself. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Points outside this range are displayed as individual dots. The figure illustrates how the distribution of districting costs varies based on different target district sizes and cities.

This figure illustrates the architecture of DISTRICTNET. It shows how a graph neural network (GNN) takes an input graph representing a geographical area, processes it to produce edge weights, and then uses those weights as input to a capacitated minimum spanning tree (CMST) solver. The CMST solution is then decoded into a districting solution. The entire pipeline is trained in a decision-aware manner, enabling the model to learn from optimal districting solutions.

DISTRICTNET uses a graph neural network (GNN) to predict edge weights for a capacitated minimum spanning tree (CMST) problem, which acts as a surrogate for the complex districting problem. The CMST solution is then decoded into a districting solution. The entire pipeline is trained in a decision-aware manner, using gradients to optimize the GNN parameters.

This figure visualizes the districting solutions obtained by four different methods (BD, FIG, PREDGNN, and DISTRICTNET) for the city of Manchester, focusing on instances with a target district size of 20 BUs. Each subfigure displays a map of Manchester, with different colors representing the different districts created by each algorithm. The depot’s location is marked with a white star. This figure helps illustrate visually the differences in the districting strategies employed by each method.

This figure shows four different districting solutions for the city of Manchester, each generated by a different method: BD, FIG, PREDGNN, and DISTRICTNET. Each solution aims to divide the city into districts of approximately 20 basic units (BUs). The methods differ in their approach to optimizing districting, with DISTRICTNET incorporating a graph neural network and a combinatorial optimization layer. The depot location, from which vehicles begin service for each district, is shown as a white star in each map. Visual comparison of the districting solutions helps illustrate the difference in performance across the various methods.

More on tables

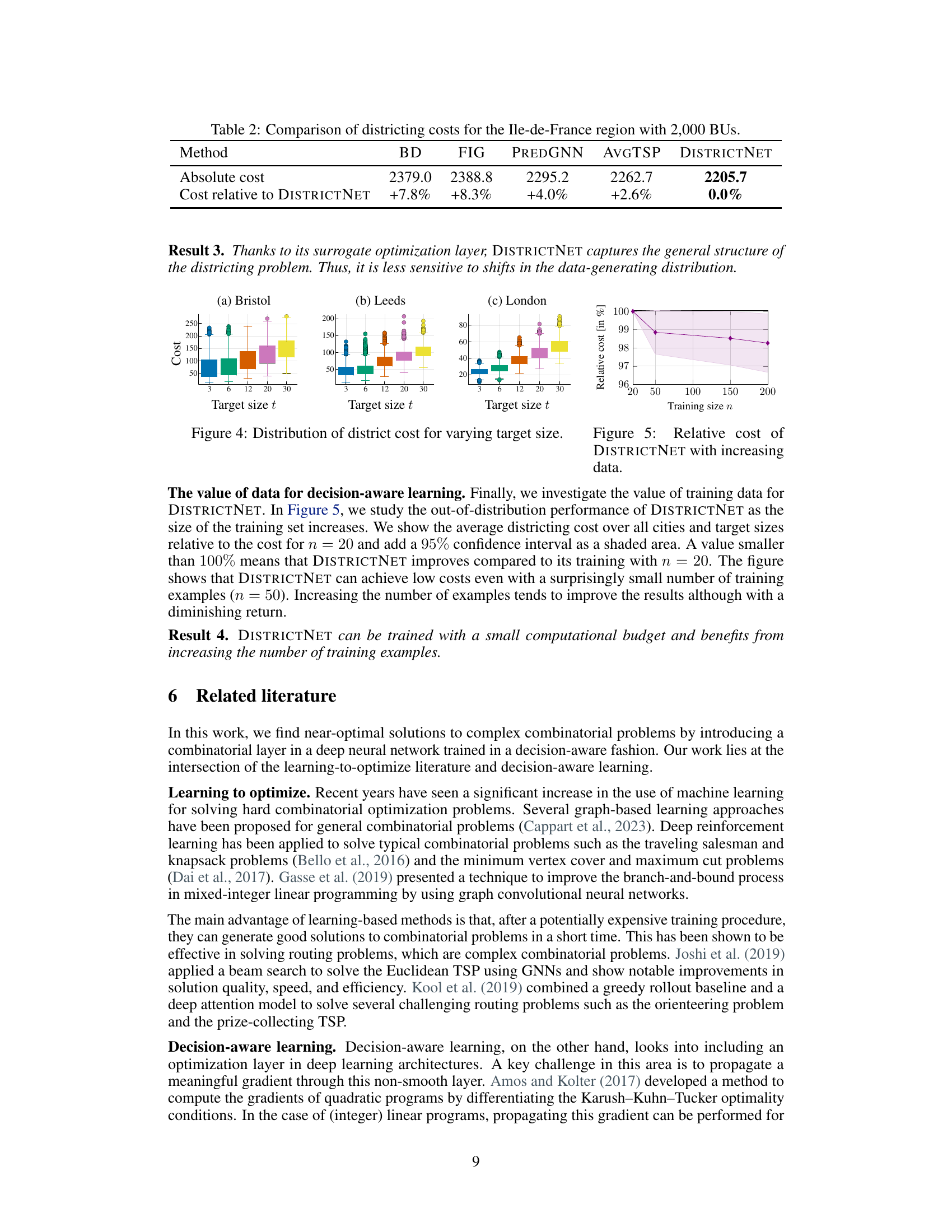

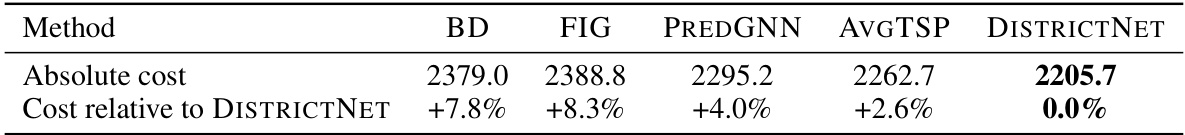

This table compares the total districting costs obtained by different methods for a large instance in Ile-de-France, with 2000 basic units and a target district size of 20. The costs are expressed as absolute values and as a percentage relative to the cost obtained by DISTRICTNET. DISTRICTNET achieves the lowest total cost.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of DISTRICTNET against four benchmark methods on a set of 35 test instances. The benchmarks vary in their approach to estimating district costs (using methods like linear regression, or GNNs without structured learning). DISTRICTNET consistently outperforms the benchmarks, highlighting the benefits of integrating a GNN and structured learning.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of DISTRICTNET against four benchmark approaches on a set of 35 test instances. The benchmarks represent different methods for estimating district costs, including linear regression models (BD, FIG), a graph neural network (PREDGNN), and a deterministic approximation (AVGTSP). DISTRICTNET consistently outperforms all benchmarks, demonstrating the significant improvement achieved by integrating a GNN and structured learning. The table shows the average relative cost and the p-value of a one-sided Wilcoxon test, indicating the statistical significance of the differences.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of different methods for solving the districting problem. The methods compared include linear regression models (BD, FIG), an unstructured learning approach with a GNN (PREDGNN), a method without learning (AVGTSP), and the proposed DISTRICTNET method which combines GNN and structured learning. The table shows the average relative cost achieved by each method, along with p-values from a Wilcoxon test, demonstrating the statistical significance of DISTRICTNET’s superior performance.

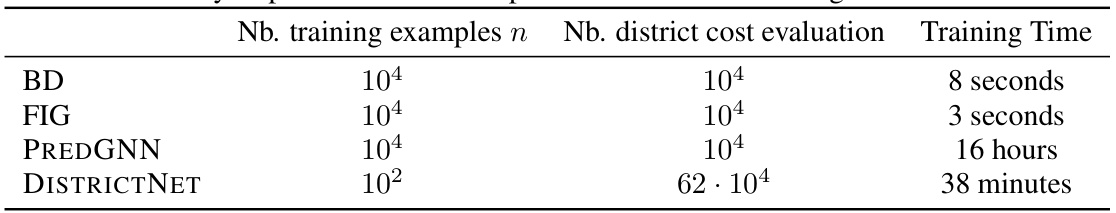

This table summarizes the computational cost for training each of the four models (BD, FIG, PREDGNN, and DISTRICTNET). It shows the number of training examples used, the number of district cost evaluations performed, and the total training time for each model. The table highlights that DISTRICTNET, despite requiring significantly more district cost evaluations, has a relatively short training time compared to PREDGNN, due to its efficient training process.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of DISTRICTNET against four benchmark approaches for solving real-world districting and routing problems. The benchmarks vary in how they estimate district costs (linear regression, a GNN without structured learning, a deterministic approximation). The results show that DISTRICTNET consistently outperforms all benchmarks across various city structures and for larger instances, due to the combination of a GNN and a differentiable optimization layer, demonstrating the value of structured learning.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of DISTRICTNET against four benchmark approaches on a set of 35 test instances. The benchmarks use different methods for estimating district costs, including linear regression (BD, FIG), a graph neural network (PREDGNN), and a deterministic approximation (AVGTSP). The table shows the average relative cost for each method compared to DISTRICTNET, demonstrating the superiority of DISTRICTNET’s combined GNN and structured learning approach. The p-values indicate the statistical significance of the differences.

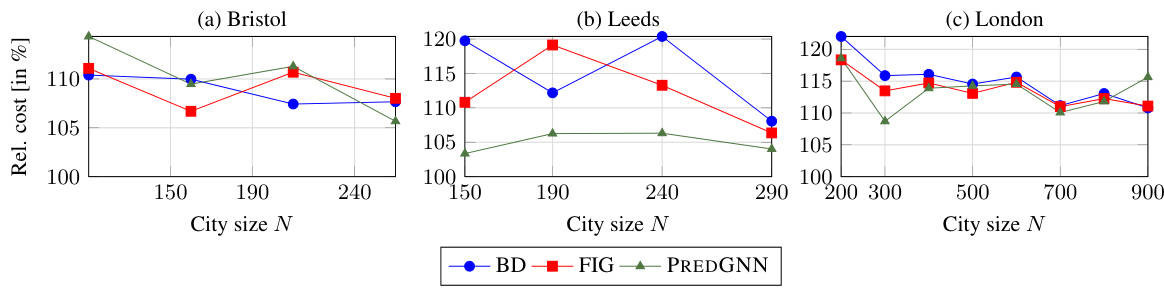

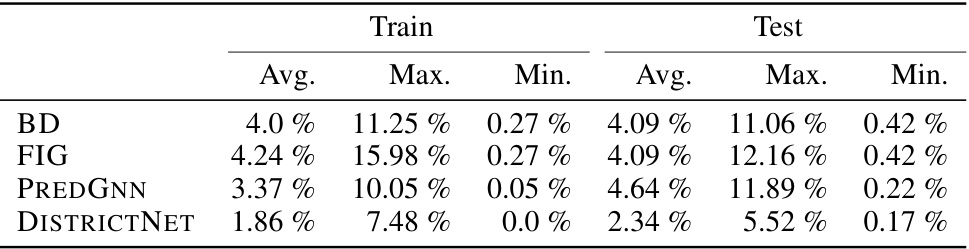

This table presents the optimality gap of four different methods (BD, FIG, PREDGNN, and DISTRICTNET) for solving districting problems. The optimality gap is calculated as the relative difference between the cost of the true optimal solution and the solution obtained by each method. The results are shown separately for both the training and testing instances. The table provides average, maximum, and minimum optimality gaps for each method and dataset.

This table presents the detailed results of the experiment comparing DISTRICTNET against other benchmark methods. For seven real-world cities and five different target district sizes, it shows the total districting cost calculated using Monte Carlo simulation. The best and second-best performing methods are highlighted in blue and orange, respectively. The final column indicates the percentage difference in cost between DISTRICTNET and the best or second-best method for each scenario.

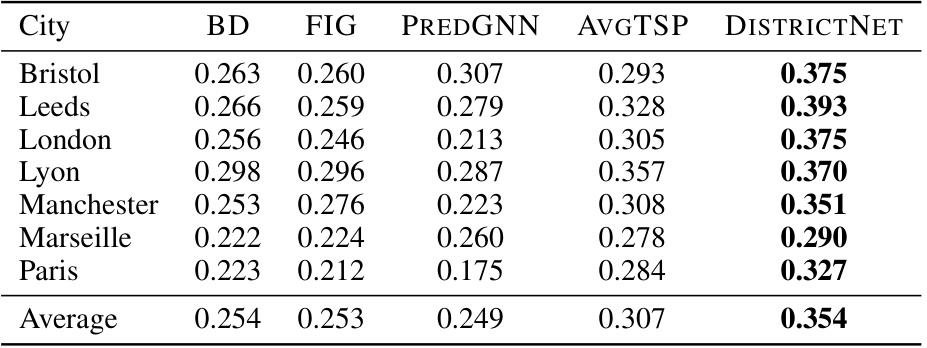

This table presents a comparison of the compactness of districts generated by different methods (BD, FIG, PREDGNN, AVGTSP, and DISTRICTNET) across seven different cities. Compactness is a measure of how geographically clustered the districts are, with a higher value indicating greater compactness (a perfect circle would have a compactness of 1). The table shows that DISTRICTNET consistently produces more compact districts than the benchmark methods.

Full paper#