TL;DR#

Prior research in adapting Large Language Models (LLMs) to the legal field faced challenges due to limited model size and data. This resulted in subpar performance compared to models trained on more general data. The legal field has unique needs that require high-performing LLMs.

This paper introduces SaulLM-54B and SaulLM-141B, significantly larger LLMs specifically trained for legal tasks using a large dataset of over 540 billion legal tokens. The researchers employed a three-pronged domain adaptation strategy: continued pretraining, an instruction-following protocol focusing on legal nuances, and aligning outputs with human preferences. This resulted in state-of-the-art performance and outperforming previous open-source models. The models are also publicly available to support further research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limited scale and data in previous legal LLMs. By scaling up model size and training data, and using a refined domain adaptation strategy, the research significantly advances legal NLP, opening avenues for improving legal reasoning in LLMs and potentially assisting legal professionals. The release of the models under the MIT license fosters collaboration and further research.

Visual Insights#

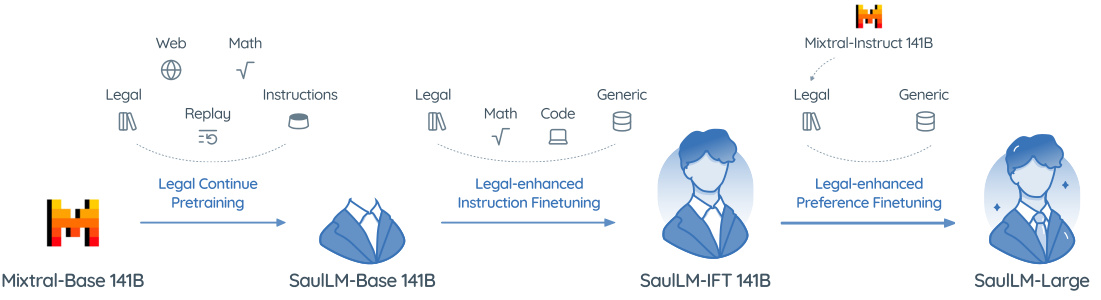

🔼 This figure illustrates the domain adaptation process used to create the SaulLM-141B model. It starts with a Mixtral-base 141B model, which undergoes three main stages of adaptation. First, legal-focused continued pretraining expands the model’s knowledge of legal concepts and language using a large corpus of legal data supplemented by general-purpose data (Web, Math, Replay). Second, legal-enhanced instruction fine-tuning refines the model’s ability to follow instructions related to legal tasks, using a combination of legal and generic instructions. Finally, legal-enhanced preference fine-tuning aligns the model’s outputs with human preferences for legal interpretations through preference filtering. The figure shows the progression from the initial Mixtral model, through the intermediate SaulLM-base and SaulLM-IFT stages, to the final SaulLM-Large model, highlighting the various data sources and adaptation techniques used in each phase.

read the caption

Figure 1: Domain adaptation method model for turning a Mixtral to a SaulLM-141B. Training involves different stages: legal domain pretraining, instruction filtering, and preference filtering.

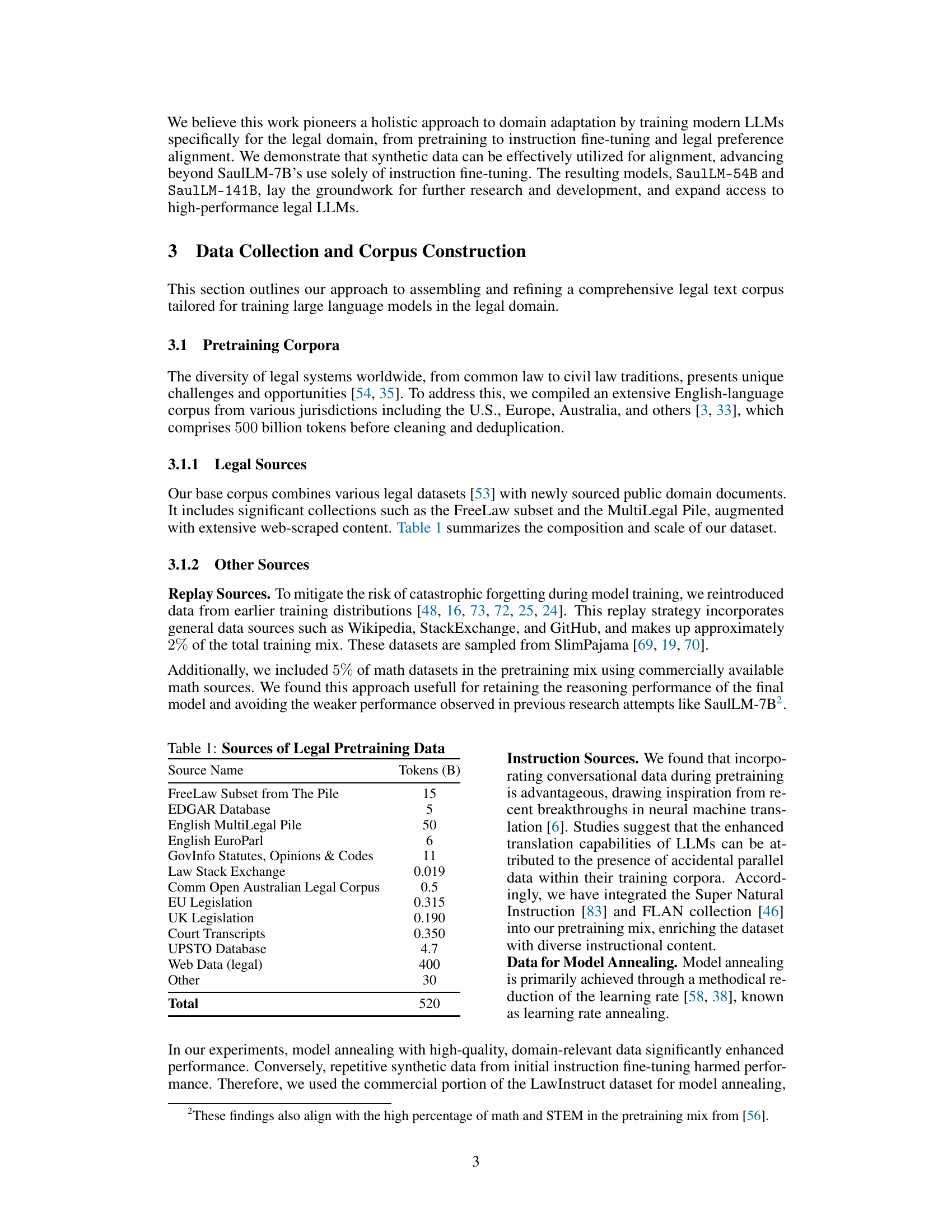

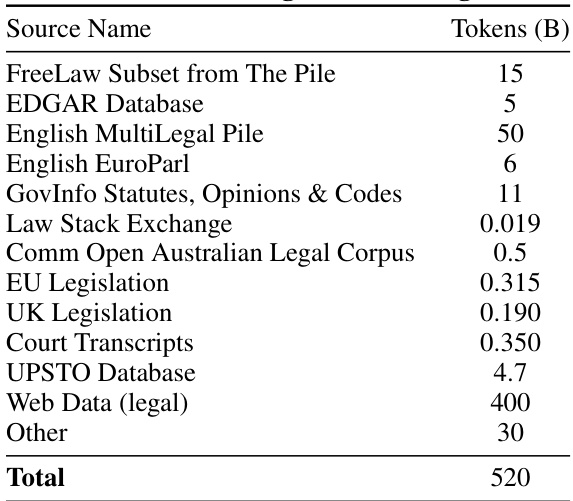

🔼 This table presents a breakdown of the sources used for the legal pretraining data, indicating the amount of data (in billions of tokens) contributed by each source. The sources include various legal databases (FreeLaw, EDGAR, MultiLegal Pile, EuroParl), government websites (GovInfo), community-based platforms (Law Stack Exchange), open legal corpora from various jurisdictions (Australia, EU, UK), specialized legal databases (UPSTO), and general web data. The inclusion of diverse sources aims to create a comprehensive and representative legal corpus for training the language models.

read the caption

Table 1: Sources of Legal Pretraining Data

In-depth insights#

Legal LLM Scaling#

Legal LLM scaling explores the challenges and opportunities in developing larger and more powerful language models specifically for legal applications. Increased model size offers potential benefits such as improved accuracy, reasoning capabilities, and the ability to handle more complex legal texts and nuanced arguments. However, scaling presents significant hurdles, including the need for massive amounts of high-quality legal data, substantial computational resources, and the management of increased model complexity. The research also needs to address ethical concerns, such as bias mitigation and ensuring fairness and transparency in legal decision-making processes. Successfully scaling legal LLMs requires a multi-faceted approach, combining advancements in model architecture, training techniques, data acquisition, and ethical considerations. Further research should investigate the optimal scaling strategies, explore the trade-offs between model size and performance, and focus on developing robust evaluation metrics that capture the specific needs and challenges of legal applications.

Domain Adaptation#

The research paper explores domain adaptation within the context of large language models (LLMs) for legal applications. The core challenge is bridging the gap between the general knowledge of an LLM and the specialized requirements of legal text interpretation and reasoning. The paper investigates a three-pronged approach. First, continued pretraining on a massive legal corpus significantly enhances the LLM’s understanding of legal terminology and concepts. Second, a specialized instruction-following protocol is implemented to refine the model’s ability to process legal tasks accurately. Finally, alignment of model outputs with human preferences ensures the model produces legal interpretations that align with human expert judgment. The authors meticulously detail the data sources, preprocessing techniques, and model training procedures. The results highlight the significant performance improvements achieved through this multi-stage domain adaptation process, outperforming existing open-source LLMs. Scalability is also addressed, with experiments conducted on models of varying sizes (54B and 141B parameters), indicating that the proposed approach is effective regardless of scale. This makes a valuable contribution to legal NLP.

MoE Model Use#

This research paper leverages Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, a crucial aspect of its methodology. The choice of MoE architecture is strategic, allowing for efficient scaling of the model’s capacity while maintaining computational efficiency. The authors specifically use MoE to enhance the model’s performance in the legal domain, a complex and nuanced area demanding high accuracy. The successful adaptation of MoE for this specific application suggests that MoE models are indeed effective for domain-specific large language models. However, the paper should provide a more in-depth analysis of the model’s specific architecture and how it contributes to the overall results. Further exploration is needed to determine whether the specific benefits of the MoE architecture outweighed any potential drawbacks, such as increased training complexity. Future research might examine the potential trade-offs between MoE and alternative architectures for similar legal NLP tasks. The impact of MoE on the model’s efficiency, resource utilization and final performance requires a deeper investigation. Ultimately, the paper’s findings support the effectiveness of MoE but lack the granular analysis needed to fully understand its contribution to the system’s success.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize enhancing the robustness and generalizability of legal LLMs. Addressing the limitations of current instruction fine-tuning and alignment methods is crucial, potentially through exploring alternative approaches like reinforcement learning or more sophisticated preference modeling techniques. Investigating the impact of model architecture choices on legal reasoning capabilities and exploring strategies to mitigate biases inherent in legal data is essential. The development of more comprehensive and nuanced evaluation benchmarks, encompassing a broader range of legal tasks and jurisdictions, is needed. Finally, research should focus on practical applications, developing tools and workflows that integrate these advanced LLMs into legal practice, while also carefully considering the ethical implications of AI in the legal system, particularly regarding issues of fairness, bias, and access to justice. The creation of more inclusive datasets is vital, to ensure these LLMs work effectively for a wider range of legal professionals and stakeholders.

Methodological Limits#

A methodological limits section for this research paper would critically examine the limitations of the domain adaptation strategies. It would delve into the challenges in obtaining a truly representative and comprehensive legal corpus, including biases stemming from data sources and inherent difficulties in capturing the nuances of legal language. The reliance on synthetic data for instruction fine-tuning and preference alignment is another crucial area to address, exploring the potential for these methods to introduce inaccuracies or overfitting. A discussion of the scaling limitations and associated computational costs, including energy consumption, is vital. Furthermore, the section should acknowledge the use of English language data primarily, limiting generalizability to other legal systems. The evaluation methodology, based on existing benchmarks such as LegalBench-Instruct, also presents limitations, which should be explicitly stated, particularly regarding the benchmarks’ inherent biases. Finally, the generalizability of findings across different model sizes and architectural choices (such as MoE models) needs a thorough discussion, specifying the extent to which the observed improvements can be reliably extrapolated.

More visual insights#

More on figures

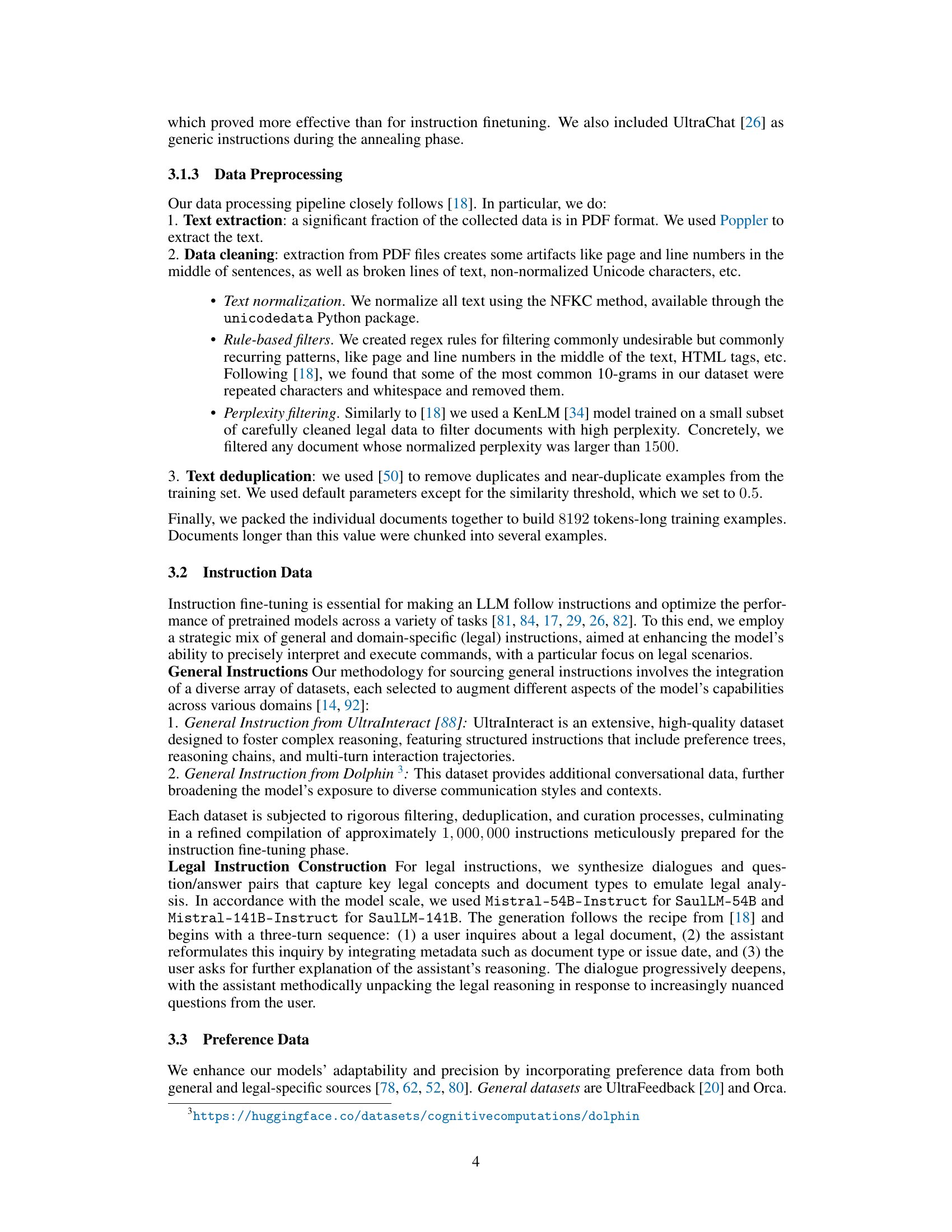

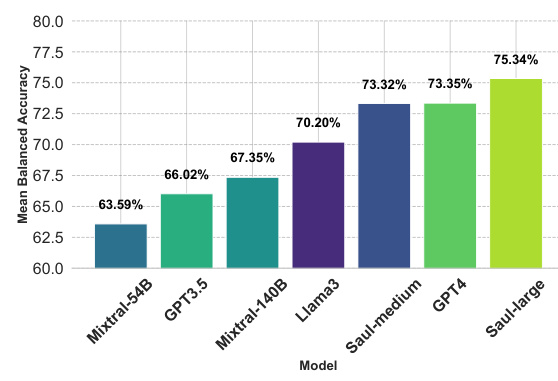

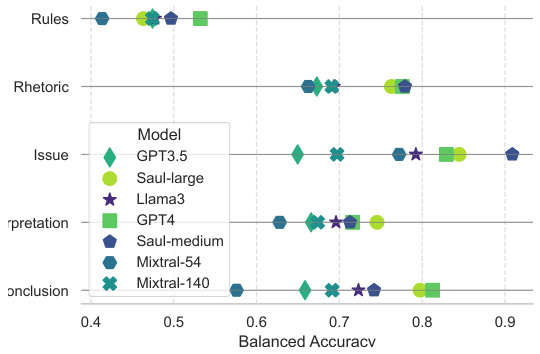

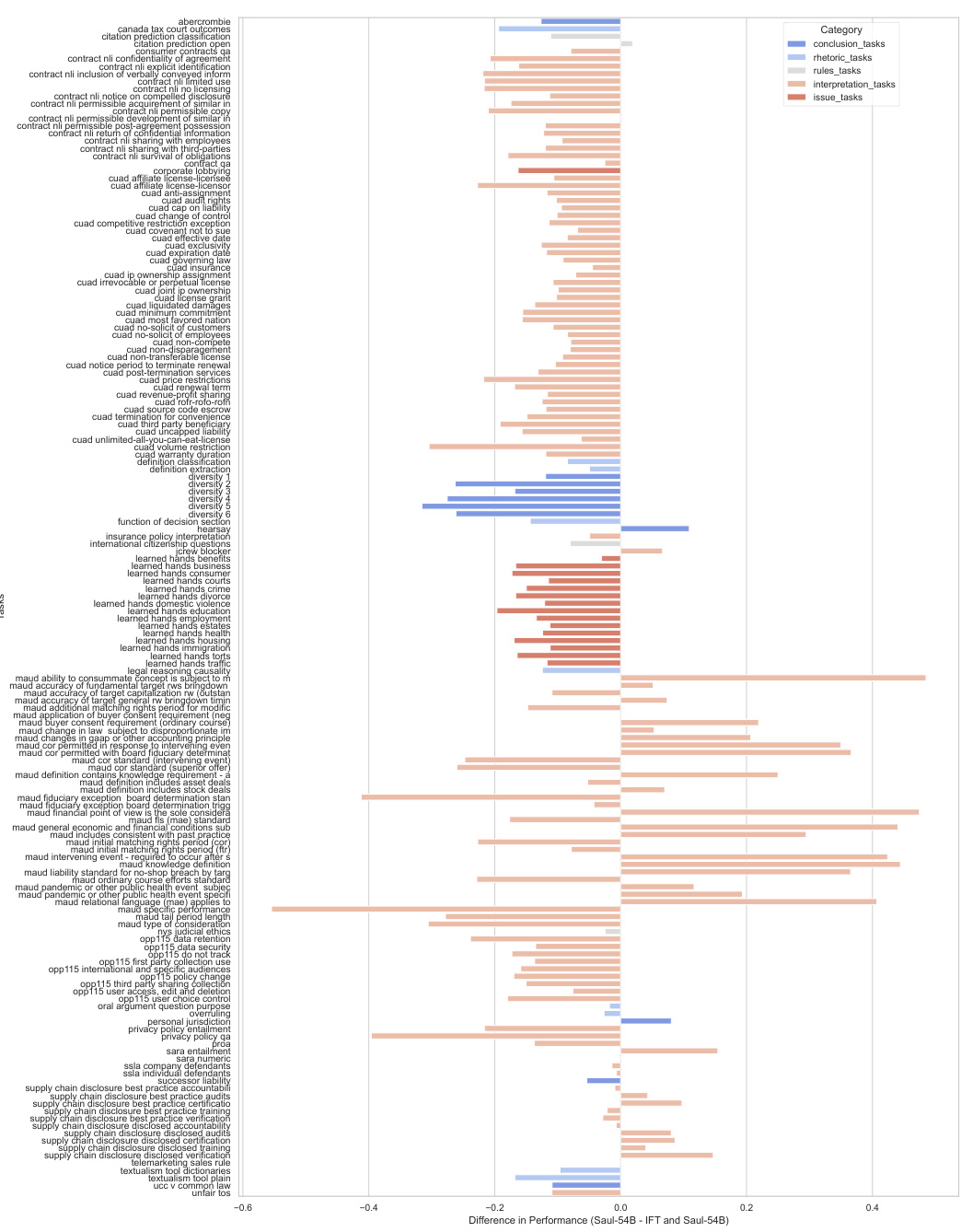

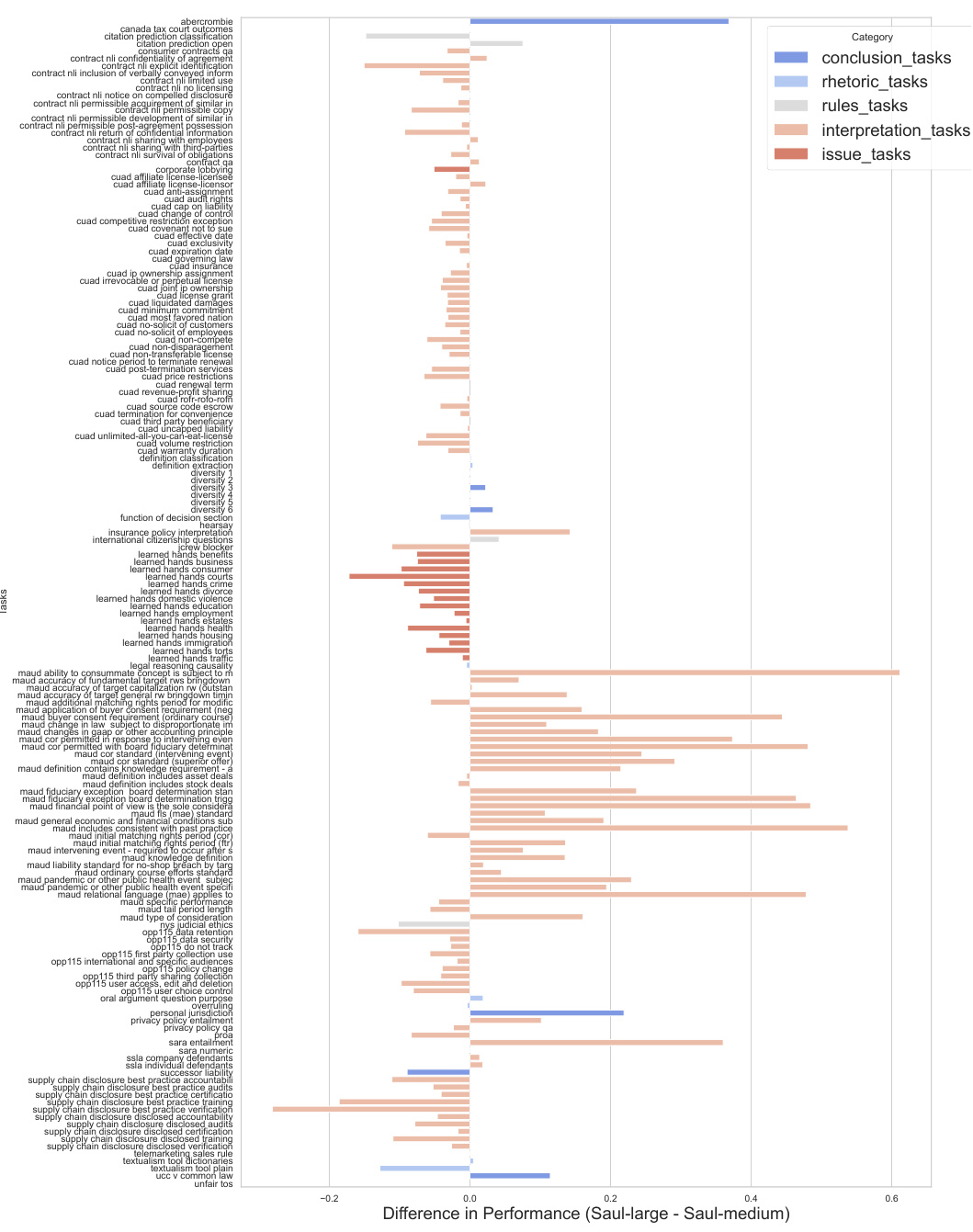

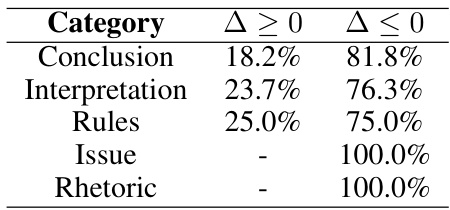

🔼 This figure presents a bar chart comparing the mean balanced accuracy achieved by various large language models (LLMs) on the LegalBench-Instruct benchmark. The LLMs compared include Mixtral-54B, GPT3.5, Mixtral-140B, Llama3, Saul-medium, GPT4, and Saul-large. Saul-large and Saul-medium are the models introduced in this paper. The chart visually demonstrates the performance improvement of SaulLM models over existing LLMs in legal reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall Results. Comparison of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium with existing models.

🔼 This figure presents the overall performance comparison of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium against other existing models such as Mixtral-54B, GPT3.5, Mixtral-140B, Llama3, GPT4 and Saul-medium on the mean balanced accuracy metric. The bar chart visually represents the performance of each model, allowing for easy comparison of their effectiveness in legal reasoning tasks. The results show that SaulLM-medium outperforms Mixtral-54B, and SaulLM-large outperforms Mixtral-141B. Interestingly, the smaller SaulLM models outperform larger models like GPT-4 and Llama3-70B. This highlights the effectiveness of the domain adaptation strategy employed.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall Results. Comparison of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium with existing models.

🔼 This figure displays a bar chart comparing the mean balanced accuracy scores achieved by various large language models (LLMs) on LegalBench-Instruct. The models compared include SaulLM-large, SaulLM-medium, Mixtral-54B, Mixtral-141B, GPT-3.5, Llama-3, and GPT-4. The chart visually demonstrates the relative performance of each model, showcasing the improved accuracy of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium compared to other models. This comparison highlights the effectiveness of the domain adaptation strategy used in developing SaulLM.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall Results. Comparison of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium with existing models.

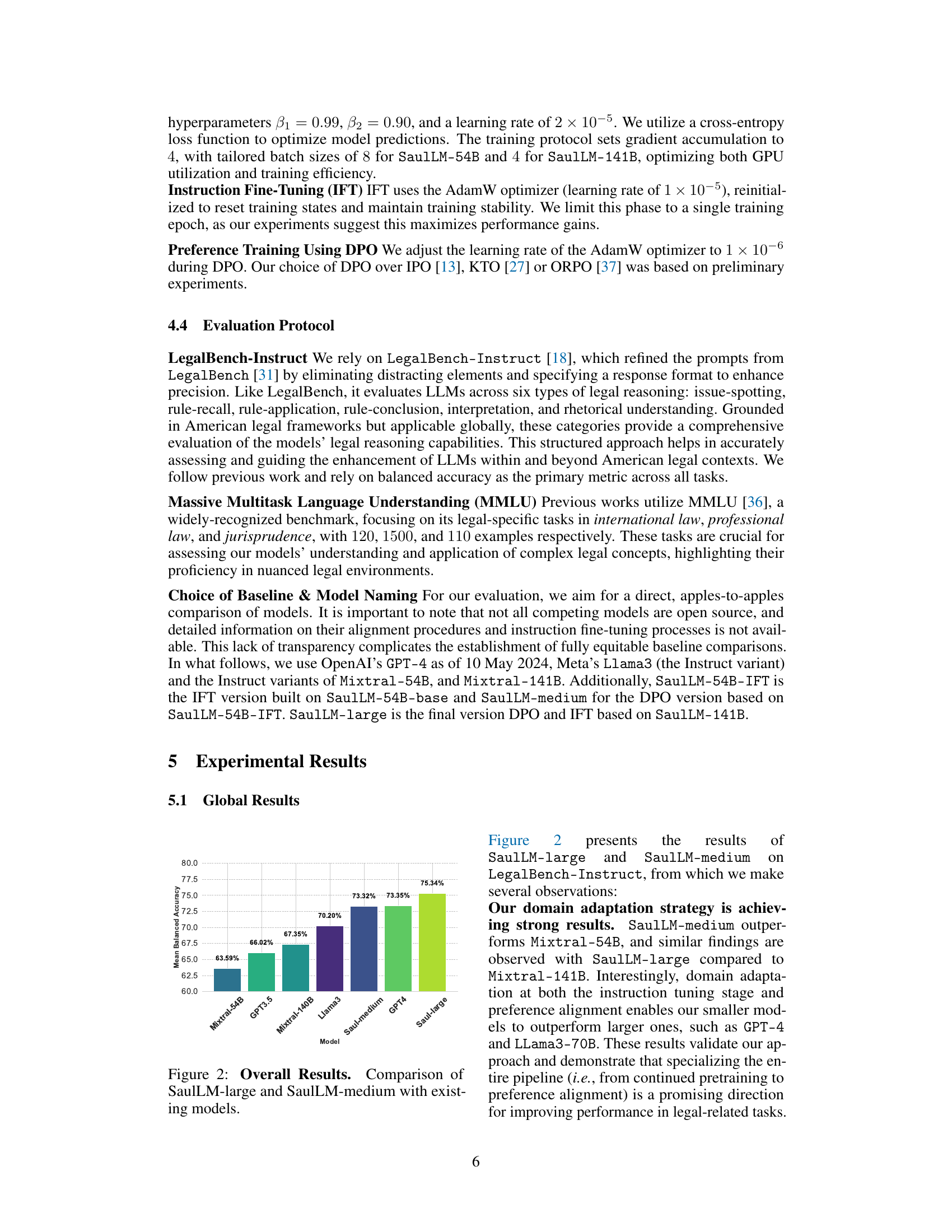

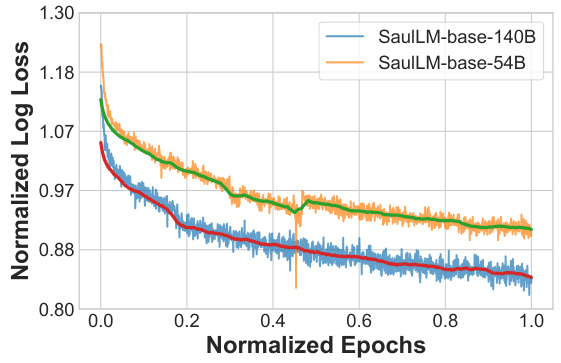

🔼 This figure displays the training loss curves for both SaulLM-141B-base and SaulLM-54B-base models plotted against normalized epochs. The curves show a consistent downward trend indicating that continued pretraining could potentially yield further performance improvements. Both raw and smoothed loss curves are presented.

read the caption

Figure 5: Continue Pretraining Analysis. Training loss for SaulLM-141B-base and SaulLM-54B-base over normalized epochs.

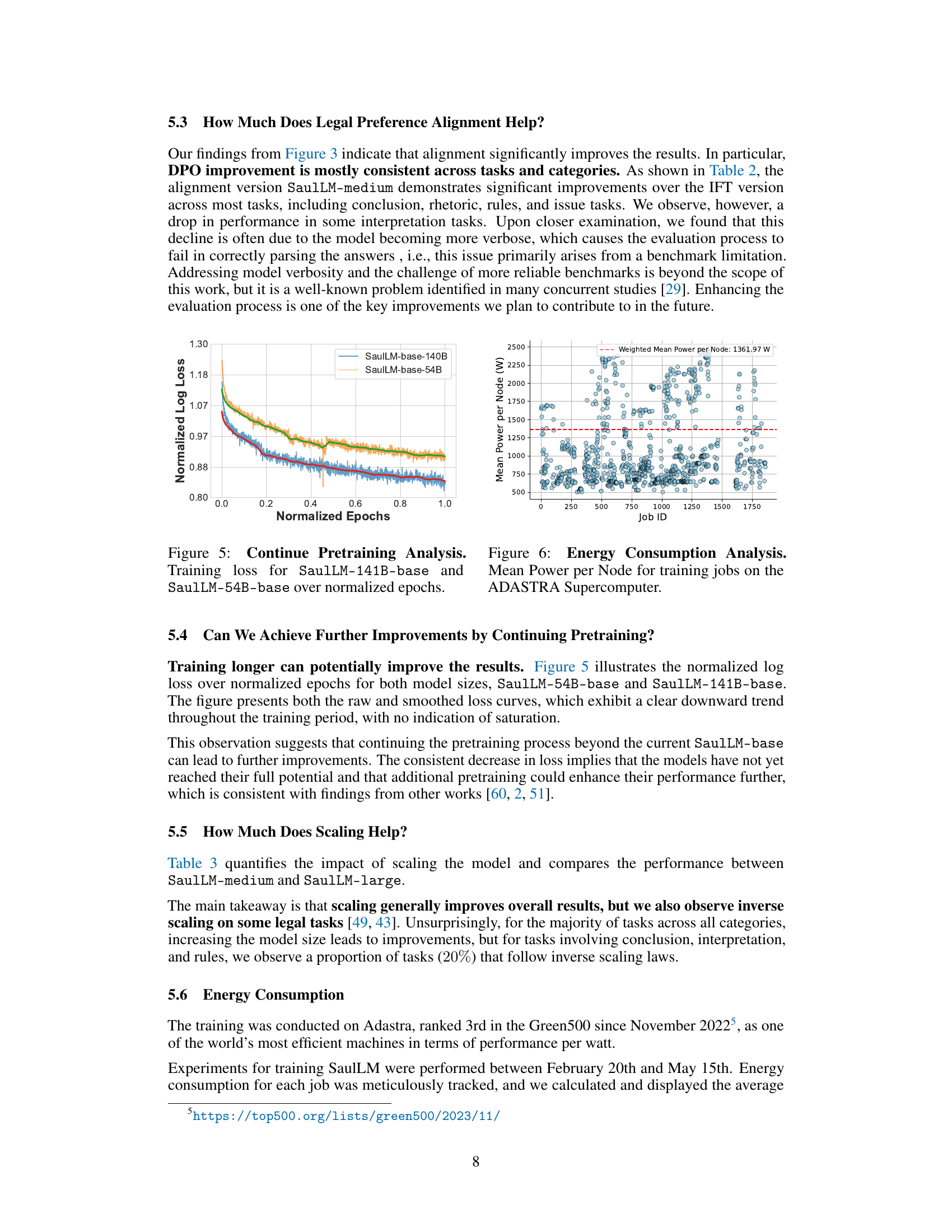

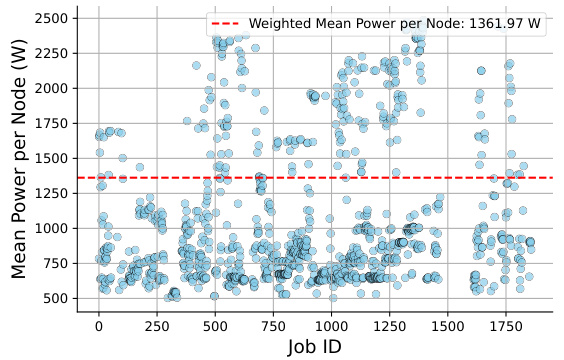

🔼 This figure shows the mean power consumption per node for each training job on the ADASTRA supercomputer. The weighted mean power per node is 1361.97W. The data points are scattered around the mean, showing the variability in power consumption for each job. The x-axis represents the job ID, and the y-axis represents the mean power per node in Watts (W).

read the caption

Figure 6: Energy Consumption Analysis. Mean Power per Node for training jobs on the ADASTRA Supercomputer.

🔼 This figure displays the relationship between GPU load and elapsed time during the training process, categorized by the number of nodes used. It visually represents the computational efficiency and resource utilization at different scales of parallelization. Higher GPU load generally indicates more intensive computation, while elapsed time shows the duration of the training process. The variation in both GPU load and time likely reflects differences in the training workload and resource allocation across various node configurations.

read the caption

Figure 7: Energy Analysis. GPU Load vs Elapsed Time for Different Numbers of Nodes.

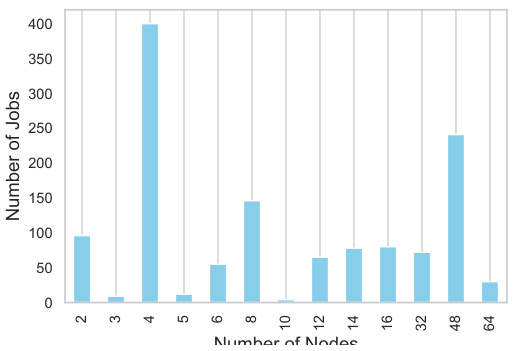

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the number of jobs and the number of nodes used in the energy consumption analysis of the SaulLM model training. The x-axis represents the number of nodes, and the y-axis represents the number of jobs run on those nodes. The data is presented as a bar chart, showing the distribution of jobs across different node counts. This provides insights into the scalability and resource utilization during the training process.

read the caption

Figure 8: Energy Analysis. Number of Jobs vs Number of Nodes.

🔼 This figure shows the training loss curves for both the SaulLM-141B-base and SaulLM-54B-base models over normalized epochs. The curves demonstrate a consistent downward trend throughout the training, indicating that the models haven’t yet reached their full potential and that further pretraining could lead to performance improvements. The raw and smoothed loss curves are presented for both models.

read the caption

Figure 5: Continue Pretraining Analysis. Training loss for SaulLM-141B-base and SaulLM-54B-base over normalized epochs.

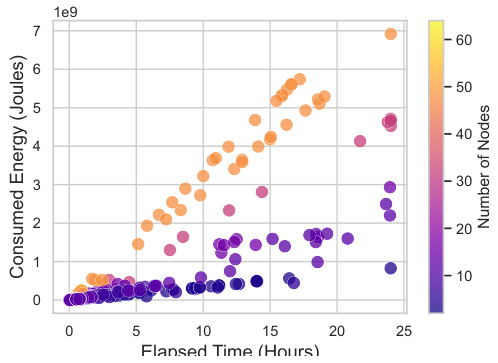

🔼 This figure displays the relationship between total power consumption (log-scaled) and GPU load for various numbers of nodes used in the training process. Different colors represent the different numbers of nodes used, allowing for a visual comparison of energy efficiency across varying computational scales. This analysis is crucial for understanding cost-effectiveness and resource allocation during large-scale model training.

read the caption

Figure 10: Energy Analysis. Log-Scaled Total Power Consumption vs GPU Load for Different Numbers of Nodes.

🔼 This figure presents a bar chart comparing the mean balanced accuracy achieved by different large language models (LLMs) on the LegalBench-Instruct benchmark. The LLMs compared are SaulLM-large, SaulLM-medium, GPT4, Mixtral-54B, and Mixtral-140B. The chart shows that SaulLM-medium outperforms Mixtral-54B, and SaulLM-large outperforms Mixtral-140B, demonstrating the effectiveness of the domain adaptation strategy employed in the SaulLM models. It also highlights that the SaulLM models (medium and large) achieve higher accuracy than Llama3-70B and GPT-3.5 models.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall Results. Comparison of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium with existing models.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium against other existing models (GPT3.5, GPT4, Llama3, Mixtral-54, and Mixtral-140) on LegalBench-Instruct. It shows the mean balanced accuracy achieved by each model across the six legal reasoning tasks. The figure highlights that SaulLM-medium outperforms Mixtral-54B, and SaulLM-large outperforms Mixtral-141B, demonstrating the effectiveness of the domain adaptation strategy. Interestingly, SaulLM’s smaller models even surpass larger models like GPT-4 and Llama3-70B, further supporting the value of the proposed domain adaptation approach.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall Results. Comparison of SaulLM-large and SaulLM-medium with existing models.

🔼 This figure shows a schematic representation of the domain adaptation process used to create the SaulLM-141B model. It starts with a base Mixtral model, which is then subjected to three main stages: 1) Legal Domain Pretraining: enhancing the model with a large corpus of legal text; 2) Instruction Fine-tuning: aligning model outputs with human-provided instructions, focusing on legal tasks; and 3) Preference Fine-tuning: refining the model’s outputs to align with human preferences regarding legal reasoning. The figure illustrates the flow of data and the transformation of the model at each stage.

read the caption

Figure 1: Domain adaptation method model for turning a Mixtral to a SaulLM-141B. Training involves different stages: legal domain pretraining, instruction filtering, and preference filtering.

🔼 This figure illustrates the domain adaptation process used to transform Mixtral models into SaulLM-141B. It highlights the three key stages involved in this process: 1. Legal Domain Pretraining: This stage involves training the model on a large corpus of legal data. 2. Instruction Filtering: This stage involves refining the model’s ability to follow instructions. 3. Preference Filtering: This stage involves aligning the model’s outputs with human preferences. The figure shows how these stages are combined to create a model that is better suited for legal tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Domain adaptation method model for turning a Mixtral to a SaulLM-141B. Training involves different stages: legal domain pretraining, instruction filtering, and preference filtering.

More on tables

🔼 This table details the sources and the amount of data (in billions of tokens) used for the pretraining phase of the SaulLM models. It breaks down the data into various categories of legal sources (e.g., FreeLaw, EDGAR, MultiLegal Pile), other legal corpora, and general-purpose data sources like Wikipedia and GitHub. The inclusion of general data is intended to mitigate catastrophic forgetting and help retain reasoning capabilities.

read the caption

Table 1: Sources of Legal Pretraining Data

🔼 This table shows the different sources of data used for pretraining the SaulLM models, along with the amount of data (in billions of tokens) contributed by each source. The sources include various legal datasets (FreeLaw, MultiLegal Pile, etc.), general-purpose datasets (Wikipedia, StackExchange, GitHub), and specialized datasets (math datasets, Super Natural Instruction). The table also provides context on the strategic inclusion of data sources to mitigate issues such as catastrophic forgetting and enhance the model’s overall capabilities.

read the caption

Table 1: Sources of Legal Pretraining Data

Full paper#