TL;DR#

Temporal action segmentation (TAS) and long-term action anticipation (LTA) are crucial for understanding human actions in videos. However, they’ve been studied separately, leading to task-specific models with limited generalization. Current LTA benchmarks also unrealistically use ground-truth future action lengths.

This paper introduces ActFusion, a unified diffusion model that addresses both TAS and LTA simultaneously. ActFusion uses anticipative masking to integrate visible (TAS) and invisible (LTA) parts of the video sequence. Results show ActFusion outperforms task-specific models on both TAS and LTA, also demonstrating improved cross-task generalization and addressing the LTA evaluation issue.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on temporal action understanding because it presents ActFusion, a novel unified diffusion model that effectively tackles both action segmentation and anticipation. This unified approach outperforms task-specific models, highlighting the benefits of joint learning. The study also addresses a critical issue in current LTA evaluation by proposing a more realistic benchmark, thus advancing the field significantly.

Visual Insights#

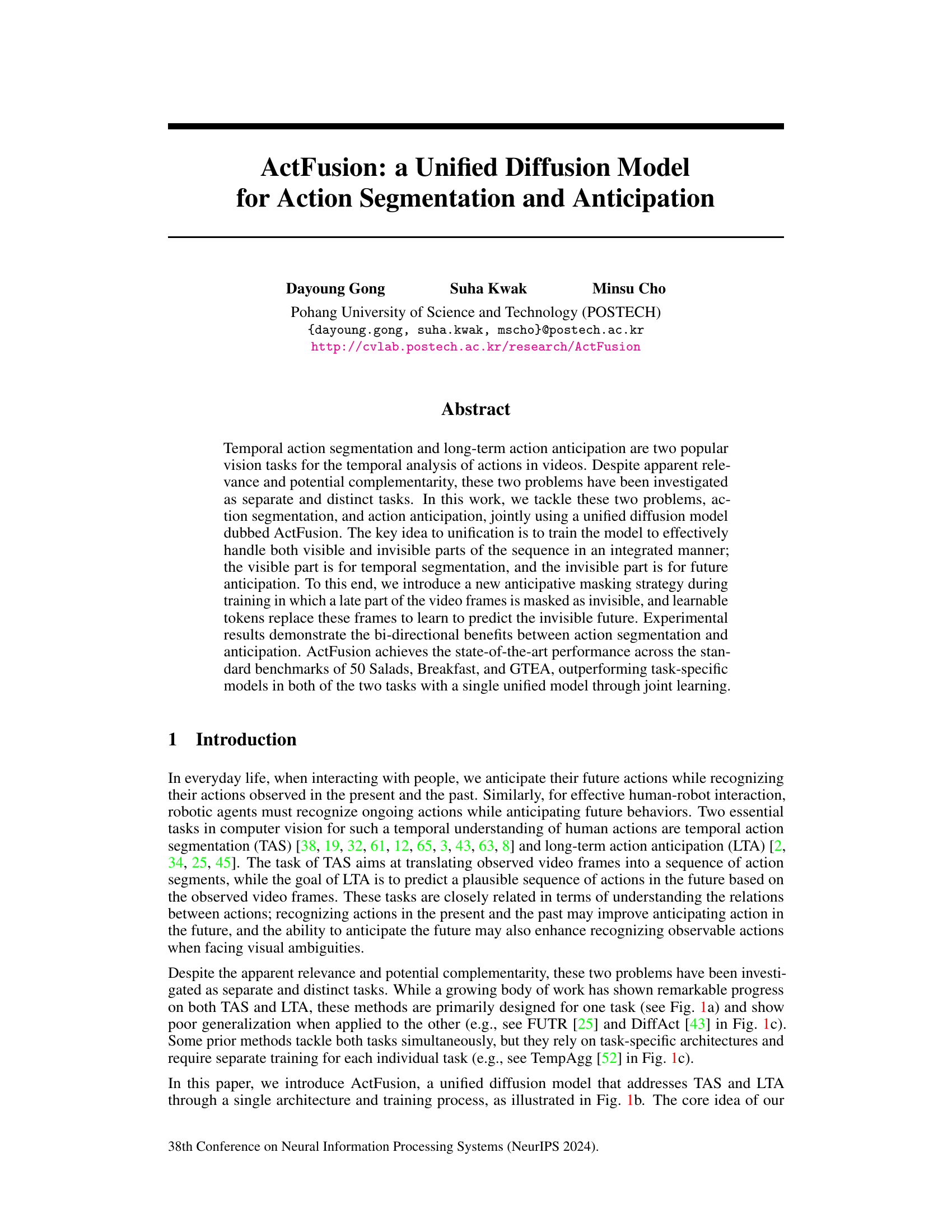

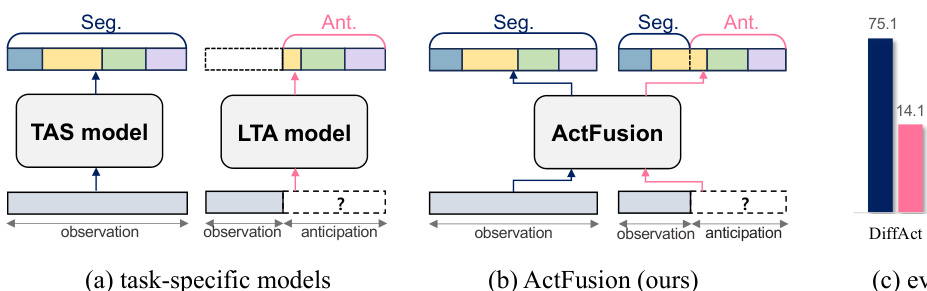

🔼 This figure compares task-specific models (DiffAct for TAS and FUTR for LTA) with a unified model (ActFusion). It shows that task-specific models perform poorly when applied to the other task. In contrast, ActFusion, which handles both action segmentation and anticipation jointly, significantly outperforms the task-specific models. The performance difference highlights the effectiveness of ActFusion’s unified architecture and training process.

read the caption

Figure 1: Task-specific models vs. ActFusion (ours). (a) Conventional task-specific models for TAS and LTA. (b) Our unified model ActFusion to address both tasks. (c) Performance comparison across tasks. Tasks-specific models such as DiffAct [43] for TAS and FUTR [25] for LTA exhibits poor performance on cross-task evaluations. ActFusion outperforms task-specific models on both TAS and LTA, including TempAgg [52], which trains separate models for each task. Note that the performance of ActFusion is evaluation result of a single model through a single training process.

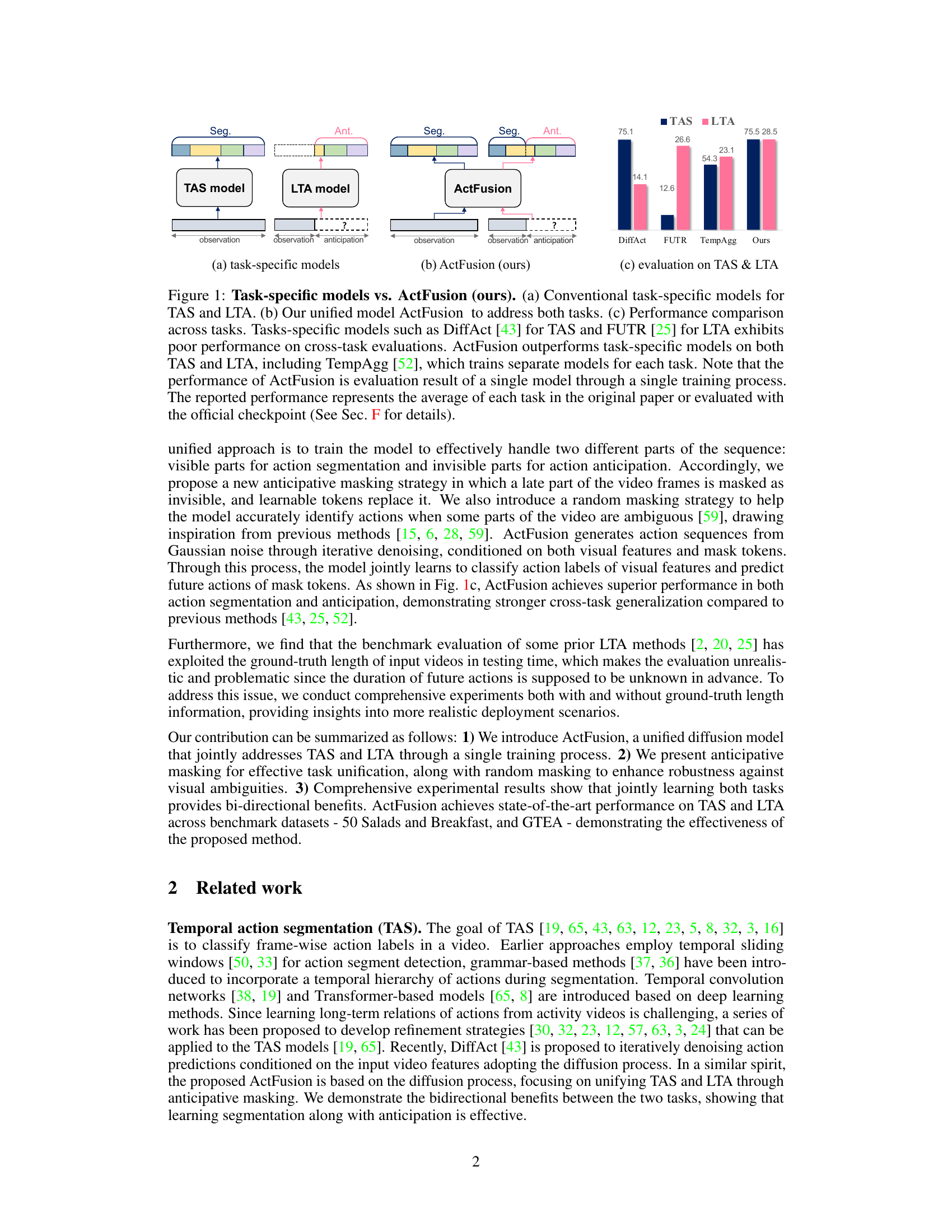

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion with other state-of-the-art methods on three benchmark datasets for Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS): 50 Salads, Breakfast, and GTEA. The metrics used for comparison include F1 scores at different thresholds (F1@{10, 25, 50}), edit score, and average accuracy. ActFusion’s performance is highlighted in bold where it achieves the best result for each metric and dataset, demonstrating its superior performance over existing methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with state of the art on TAS. The overall results demonstrate the efficacy of ActFusion on TAS, achieving state-of-the-art performance across benchmark datasets. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

In-depth insights#

Unified Diffusion#

A unified diffusion model presents a novel approach to address the challenges of temporal action segmentation and long-term action anticipation. By integrating both tasks within a single framework, it leverages the strengths of each to improve the overall accuracy and robustness of both action segmentation and anticipation. The key innovation is the use of an anticipative masking strategy, which allows the model to learn to predict future actions from partially observed sequences. This approach is different from conventional methods that treat these tasks separately, leading to potential performance gains and improved cross-task generalization. Joint learning through a shared architecture and training process further enhances the model’s ability to understand the temporal relationship between actions and improve the accuracy of prediction, especially for future actions. This unified model demonstrates the potential for significant advancements in the field of video understanding through a more holistic approach to temporal action modeling.

Anticipative Masking#

The concept of ‘Anticipative Masking’ presents a novel approach to unify action segmentation and anticipation tasks in video analysis. By strategically masking the latter portion of video frames during training, the model is forced to predict future actions based solely on the observed portion, effectively bridging these previously separate tasks. This technique is particularly insightful because it directly addresses the inherent temporal relationship between observing current actions and predicting future ones. The use of learnable tokens to replace the masked sections further enhances the model’s ability to learn and generate plausible future sequences, rather than simply filling in missing information. This approach is superior to task-specific methods that train on each task individually because it encourages the model to learn cross-task relationships, ultimately leading to better performance on both tasks. The success hinges on the model’s ability to learn meaningful representations from both visible and masked portions of the video, requiring a deep understanding of both temporal context and action dynamics.

Cross-Task Benefits#

The concept of “Cross-Task Benefits” in the context of a research paper on a unified diffusion model for action segmentation and anticipation suggests that jointly training a model for both tasks improves performance compared to training separate models. This improvement likely stems from shared representations and features learned by the unified model. The model might learn to recognize action patterns useful for both segmentation (identifying actions in visible frames) and anticipation (predicting actions in unseen frames). Furthermore, mutual reinforcement is expected: improved action segmentation potentially helps with better anticipation of future actions, and vice versa, leading to superior performance on both tasks. The degree of this improvement is an important aspect of the study’s findings, demonstrating the strength of the unified approach. Investigating how the model handles the transition between visible and invisible parts of the sequence (the boundary between segmentation and anticipation) would also be critical to explaining the cross-task benefits. Finally, analysis of specific components (e.g., attention mechanisms or learned embeddings) might reveal how information learned during one task aids performance in the other.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section in a research paper would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method against state-of-the-art techniques. It should clearly state the datasets used, the metrics employed (precision, recall, F1-score, accuracy, etc.), and provide a tabular or graphical comparison of the performance. Statistical significance testing is crucial for demonstrating the reliability of the results; p-values or confidence intervals would strengthen the claims. The discussion should go beyond simple numerical comparisons, offering a thoughtful analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed method relative to others. Contextualization is key; why are these particular benchmarks chosen? What are their limitations? Acknowledging limitations and discussing potential biases within the benchmarks enhances the credibility of the evaluation. Finally, a clear conclusion summarizing the main findings of the benchmark comparison is necessary. This section would be crucial to assess the overall contribution and impact of the research presented.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore weakly supervised learning approaches to reduce reliance on extensive manual annotation, thereby making the model more practical. Furthermore, integrating additional activity information, especially segment-wise action relations, could enhance the model’s understanding of temporal dynamics. Investigating how different conditioning features impact model performance is also worthwhile; perhaps incorporating multi-modal information would boost accuracy. Lastly, studying the effectiveness of reconstruction loss for both short-term and long-term anticipation tasks warrants further investigation to determine its optimal application. These explorations would enhance ActFusion’s robustness and expand its potential applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure compares the performance of task-specific models for Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS) and Long-term Action Anticipation (LTA) with the proposed unified model, ActFusion. (a) shows traditional approaches using separate models for TAS and LTA. (b) illustrates ActFusion, which combines both tasks into a single model. (c) presents a bar chart comparing the performance of ActFusion and other models on both TAS and LTA, demonstrating ActFusion’s superior performance and efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Task-specific models vs. ActFusion (ours). (a) Conventional task-specific models for TAS and LTA. (b) Our unified model ActFusion to address both tasks. (c) Performance comparison across tasks. Tasks-specific models such as DiffAct [43] for TAS and FUTR [25] for LTA exhibits poor performance on cross-task evaluations. ActFusion outperforms task-specific models on both TAS and LTA, including TempAgg [52], which trains separate models for each task. Note that the performance of ActFusion is evaluation result of a single model through a single training process. The reported performance represents the average of each task in the original paper or evaluated with the official checkpoint (See Sec. F for details).

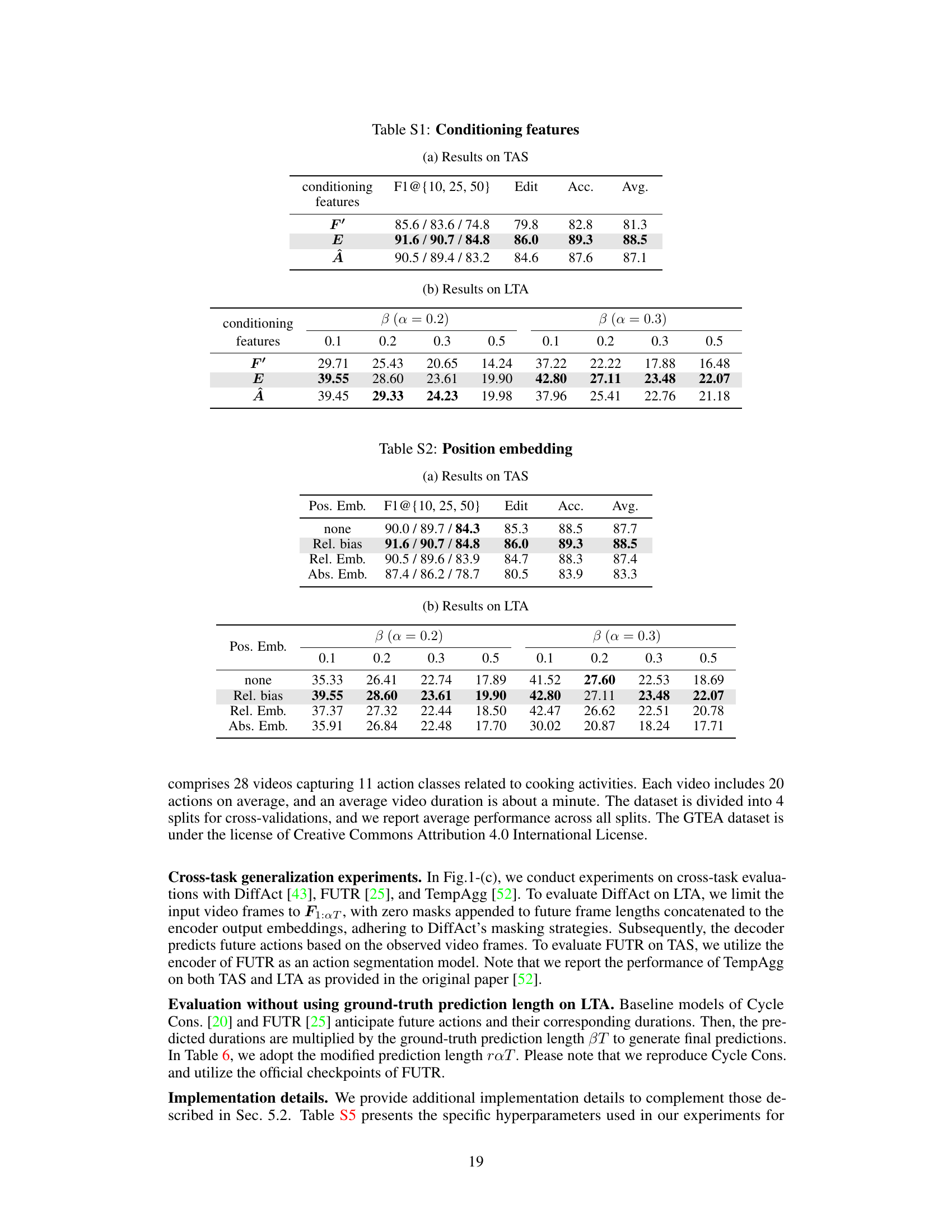

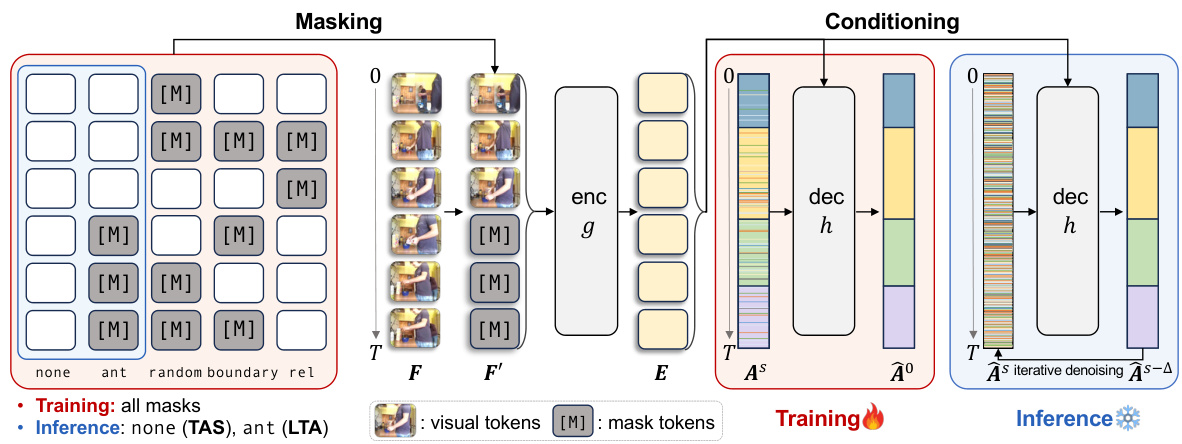

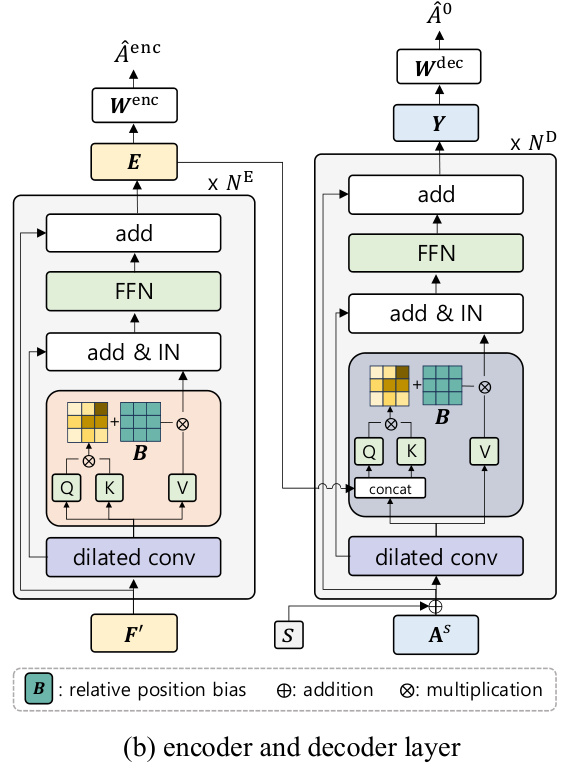

🔼 The figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the ActFusion model. During training, various masking strategies are randomly applied to the input video frames, replacing masked portions with learnable tokens. These masked features are then processed by an encoder to generate visual embeddings, which in turn condition a decoder. The decoder iteratively denoises action labels. During inference, different masking strategies are used for different tasks (no masking for action segmentation, anticipative masking for action anticipation). The decoder iteratively denoises the action labels to generate predictions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall pipeline of ActFusion. During training, we randomly select one of five masking strategies and apply it to input video frames F, replacing masked regions with learnable tokens to obtain masked features Fʹ. These features are processed by the encoder g to produce visual embeddings E, which condition the decoder h to denoise action labels from As to Aº at time-step s. For inference, we use different masking strategies depending on the task: no masking for TAS and anticipative masking for LTA. The decoder then iteratively denoises action labels following ÂS → ÂS-A → ... → º using the DDIM update rule [54].

🔼 This figure compares the performance of task-specific models (DiffAct for TAS and FUTR for LTA) against the unified ActFusion model. It highlights ActFusion’s superior performance on both tasks, demonstrating the benefits of a joint learning approach.

read the caption

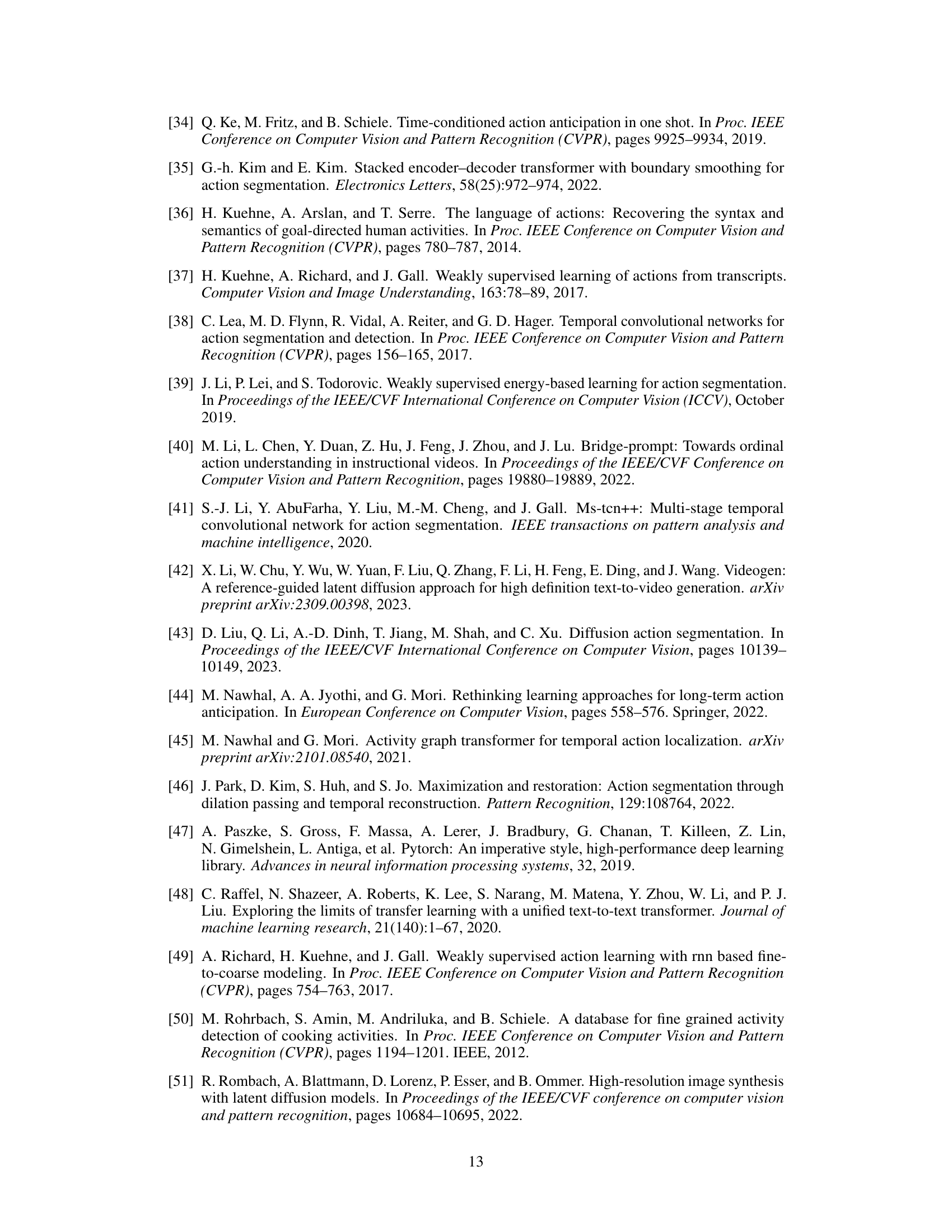

Figure 1: Task-specific models vs. ActFusion (ours). (a) Conventional task-specific models for TAS and LTA. (b) Our unified model ActFusion to address both tasks. (c) Performance comparison across tasks. Tasks-specific models such as DiffAct [43] for TAS and FUTR [25] for LTA exhibits poor performance on cross-task evaluations. ActFusion outperforms task-specific models on both TAS and LTA, including TempAgg [52], which trains separate models for each task. Note that the performance of ActFusion is evaluation result of a single model through a single training process. The reported performance represents the average of each task in the original paper or evaluated with the official checkpoint (See Sec. F for details).

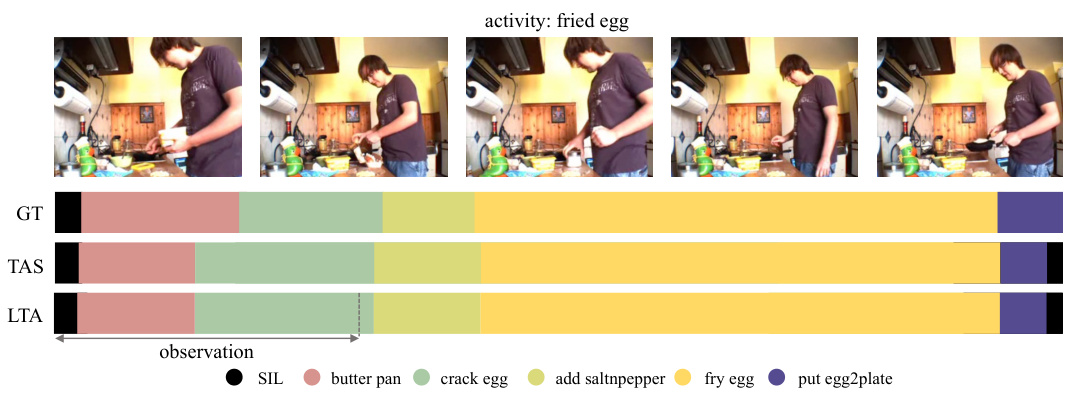

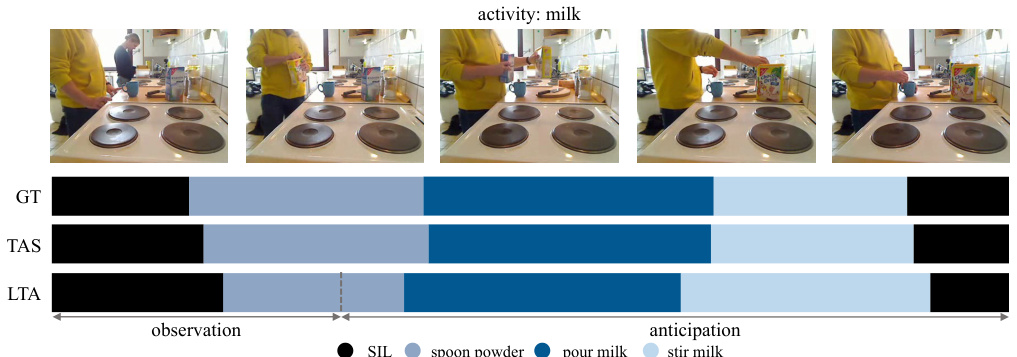

🔼 This figure shows the qualitative results of the ActFusion model on the tasks of temporal action segmentation (TAS) and long-term action anticipation (LTA). It displays video frames from three different datasets (Breakfast, 50 Salads, and GTEA). For each video sequence, the ground truth action labels (GT), the model’s predictions for action segmentation (TAS), and the model’s predictions for action anticipation (LTA) are displayed alongside. The dashed line indicates the boundary between the observed frames (used for segmentation) and the unobserved frames (used for anticipation). The figure visually demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately classify both currently occurring and future actions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative results

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the ActFusion model. It shows how the model uses different masking strategies during training and inference. During training, random masking helps the model to learn from incomplete data, while during inference, different masking is applied depending on whether the task is temporal action segmentation (TAS) or long-term action anticipation (LTA). The encoder processes the masked features, and the decoder iteratively refines the action labels through a denoising process. The diagram clearly shows the flow of information from input video frames to final action predictions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall pipeline of ActFusion. During training, we randomly select one of five masking strategies and apply it to input video frames F, replacing masked regions with learnable tokens to obtain masked features F'. These features are processed by the encoder g to produce visual embeddings E, which condition the decoder h to denoise action labels from As to Aˆ0 at time-step s. For inference, we use different masking strategies depending on the task: no masking for TAS and anticipative masking for LTA. The decoder then iteratively denoises action labels following AˆS → AˆS−∆ → ... → Aˆ0 using the DDIM update rule [54].

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the ActFusion model. It shows how the model uses different masking strategies during training and inference for action segmentation and anticipation. During training, five masking strategies are randomly selected and applied, replacing masked parts of the video with learnable tokens. The encoder processes these masked features and generates embeddings that condition the decoder. The decoder iteratively denoises action labels to reconstruct the ground truth. During inference, the masking strategy varies depending on whether action segmentation or action anticipation is the task.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall pipeline of ActFusion. During training, we randomly select one of five masking strategies and apply it to input video frames F, replacing masked regions with learnable tokens to obtain masked features Fʹ. These features are processed by the encoder g to produce visual embeddings E, which condition the decoder h to denoise action labels from As to Aº at time-step s. For inference, we use different masking strategies depending on the task: no masking for TAS and anticipative masking for LTA. The decoder then iteratively denoises action labels following ÂS → ÂS-A → ... → º using the DDIM update rule [54].

🔼 This figure presents qualitative results from ActFusion, evaluated on both TAS and LTA using a single model. The figure includes video frames, ground-truth action sequences, and predicted results for TAS and LTA. For LTA, only the visible parts (observed frames) are used as input. The results show that ActFusion effectively handles both visible and future segments, accurately classifying current actions and anticipating future ones.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative results

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the ActFusion model. It shows how the model uses different masking strategies during training and inference to handle both action segmentation and anticipation tasks. The training process involves randomly selecting one of five masking strategies and replacing masked regions with learnable tokens. The inference process uses different masking strategies depending on the task, either with no masking for action segmentation or anticipative masking for action anticipation. The encoder and decoder processes are also shown, with the decoder iteratively denoising action labels to generate predictions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall pipeline of ActFusion. During training, we randomly select one of five masking strategies and apply it to input video frames F, replacing masked regions with learnable tokens to obtain masked features Fʹ. These features are processed by the encoder g to produce visual embeddings E, which condition the decoder h to denoise action labels from As to Aº at time-step s. For inference, we use different masking strategies depending on the task: no masking for TAS and anticipative masking for LTA. The decoder then iteratively denoises action labels following ÂS → ÂS-A → ... → º using the DDIM update rule [54].

🔼 This figure showcases qualitative results from ActFusion, evaluated on both TAS and LTA using a single model. It displays video frames alongside ground truth action sequences and the model’s predictions for both TAS (action segmentation) and LTA (action anticipation). The LTA predictions are based solely on the visible (observed) portion of the video frames. The visualization highlights the model’s ability to accurately classify actions in the observed frames (TAS) and anticipate future actions in unseen portions (LTA).

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative results

🔼 This figure presents qualitative results from ActFusion, evaluated on both TAS and LTA using a single model. The figure includes video frames, ground-truth action sequences, and predicted results for TAS and LTA. For LTA, only the visible parts (observed frames) are used as input. The results show that ActFusion effectively handles both visible and future segments, accurately classifying current actions and anticipating future ones. Additional results are provided in Figures S3 and S4.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative results

More on tables

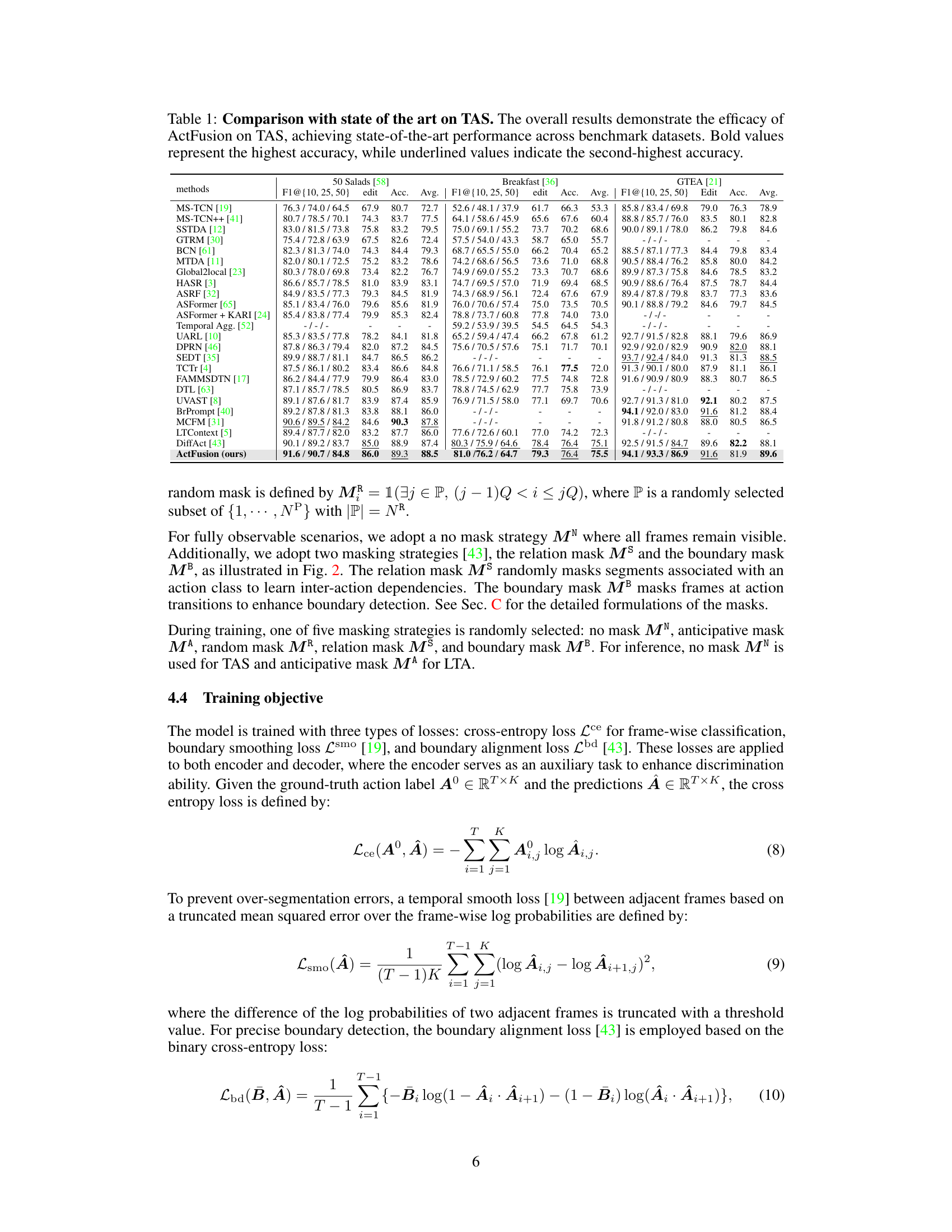

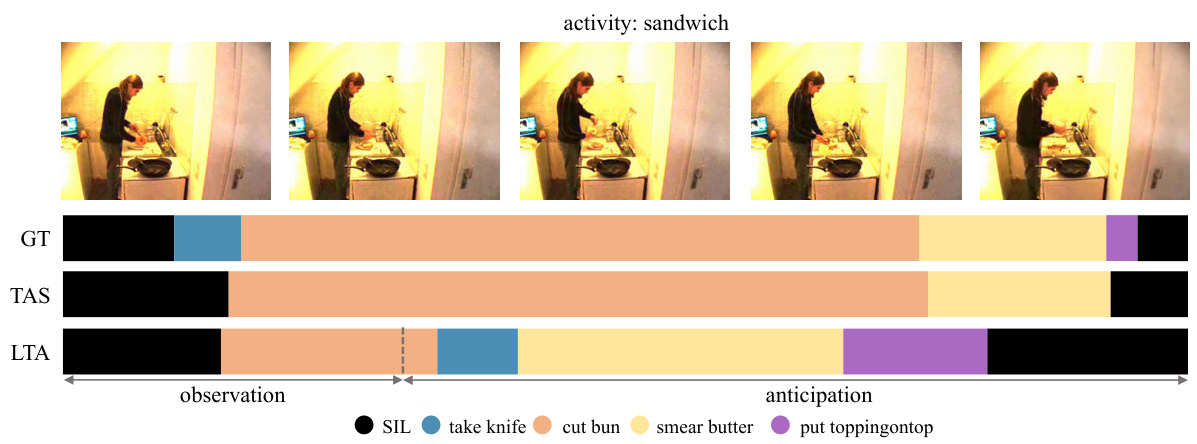

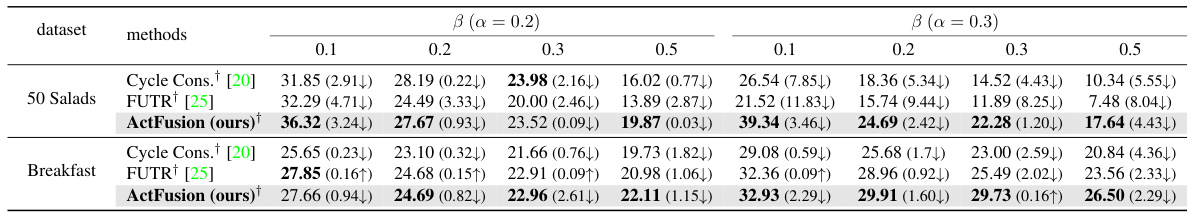

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion with other state-of-the-art models on the Long-term Action Anticipation (LTA) task. It shows the results for different datasets (50 Salads and Breakfast), input types (labels and features), and anticipation ratios (α and β). Bold values highlight the best performance for each setting, while underlined values indicate the second-best performance. This demonstrates ActFusion’s superior performance in LTA compared to other methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with the state of the art on LTA. The overall results demonstrate the effectiveness of ActFusion, achieving new SOTA performance in LTA. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

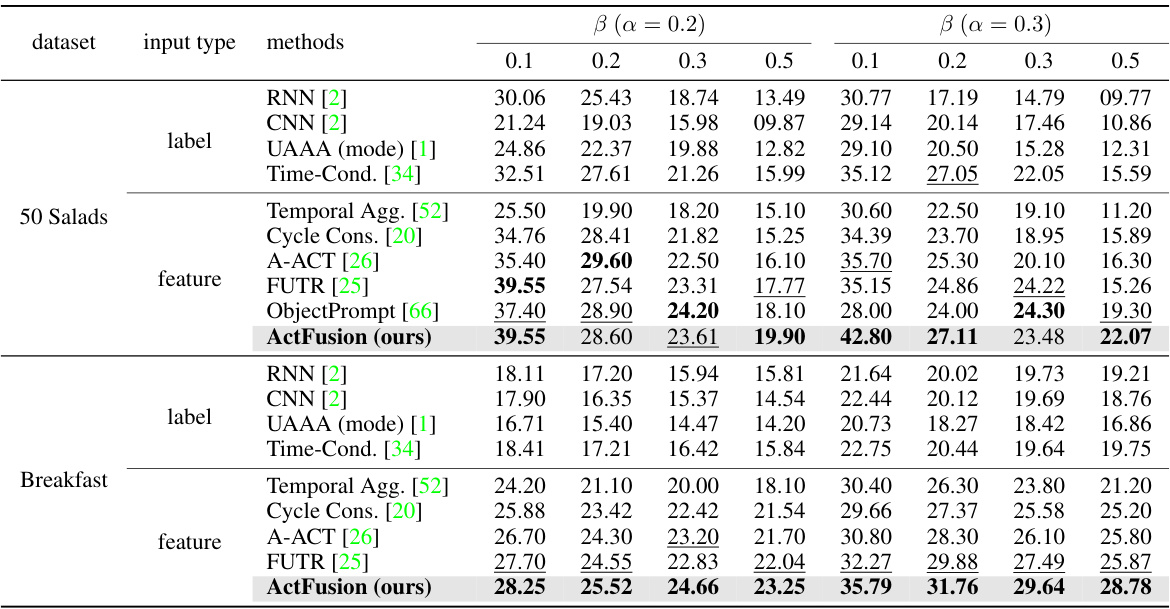

🔼 This table presents an ablation study demonstrating the impact of learning temporal action segmentation (TAS) on long-term action anticipation (LTA). It shows the results of experiments conducted on the 50 Salads dataset, where the action segmentation loss (Lenc) was selectively removed. The results indicate that learning action segmentation contributes significantly to the improvement of action anticipation performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Segmentation helps anticipation

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion with other state-of-the-art models on three benchmark datasets for Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS): 50 Salads, Breakfast, and GTEA. The metrics used for comparison include F1 scores at different thresholds (10, 25, 50), edit score, average accuracy, and frame-wise accuracy. ActFusion demonstrates superior performance, achieving state-of-the-art results on all three datasets. Bold values indicate the best performance, while underlined values indicate second-best performance for each metric and dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with state of the art on TAS. The overall results demonstrate the efficacy of ActFusion on TAS, achieving state-of-the-art performance across benchmark datasets. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion against other state-of-the-art Long-Term Action Anticipation (LTA) methods on benchmark datasets (50 Salads and Breakfast). It shows the accuracy of each method for different prediction lengths (beta values) and observation ratios (alpha values). ActFusion consistently achieves the highest or second-highest accuracy across all settings, showcasing its superior performance in LTA.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with the state of the art on LTA. The overall results demonstrate the effectiveness of ActFusion, achieving new SOTA performance in LTA. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion with other state-of-the-art methods on three benchmark datasets for Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS): 50 Salads, Breakfast, and GTEA. The metrics used for comparison include F1 scores at different thresholds (10, 25, 50), edit score, and average accuracy. ActFusion achieves the highest accuracy across all three datasets and metrics, outperforming other methods. Bold values represent the top accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-best accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with state of the art on TAS. The overall results demonstrate the efficacy of ActFusion on TAS, achieving state-of-the-art performance across benchmark datasets. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

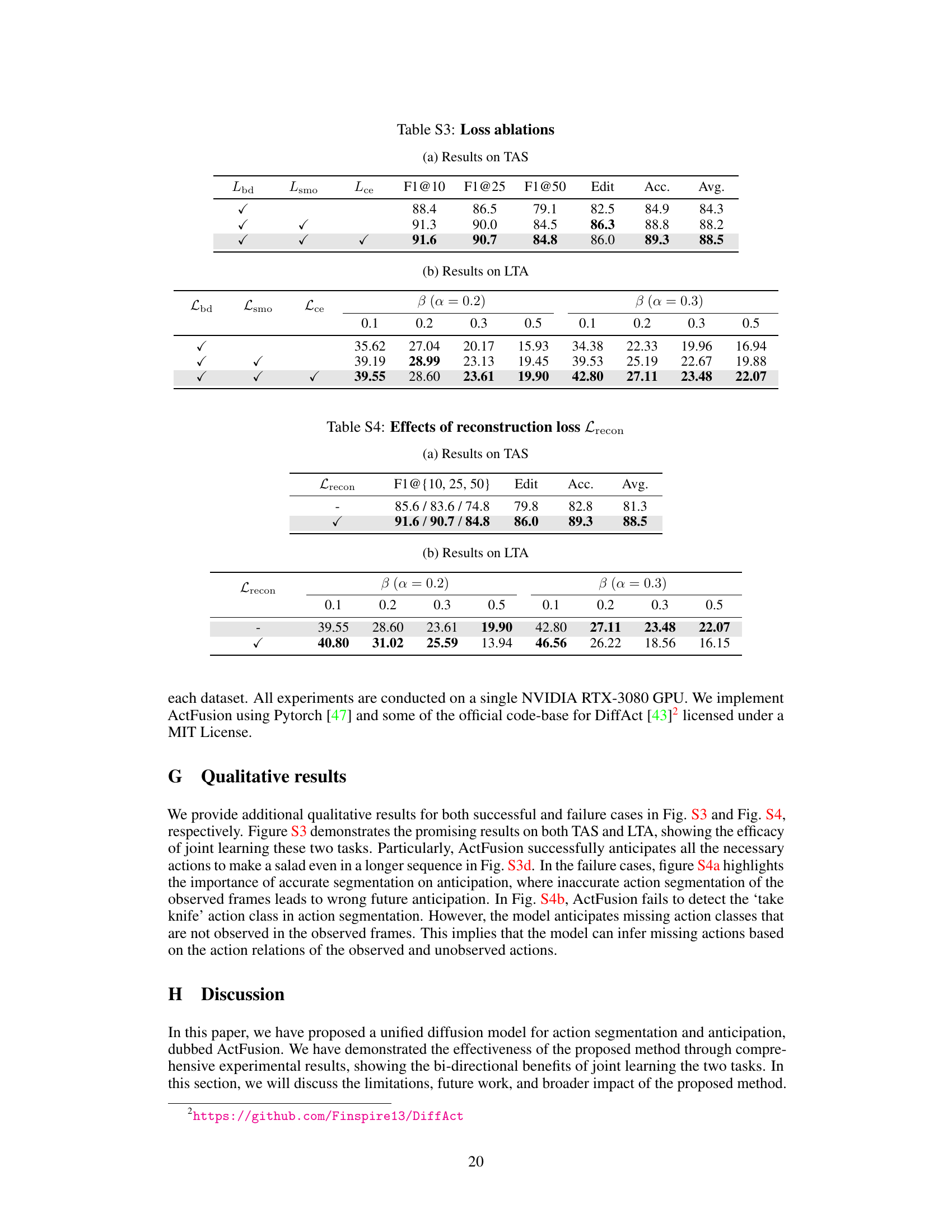

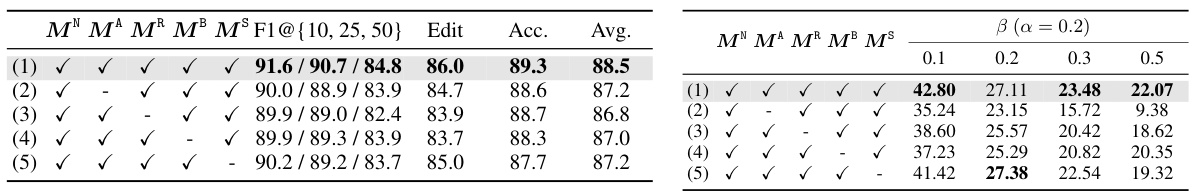

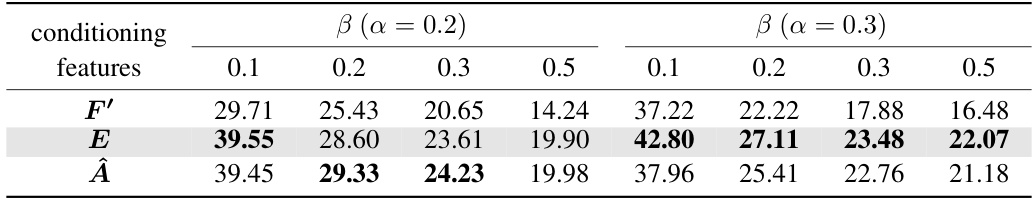

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on different types of conditioning features used in ActFusion. Part (a) shows the performance of the model on the Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS) task using three different conditioning features: masked features (F’), encoded features (E), and encoder predictions (Â). The table reports the F1-score at different thresholds (10, 25, 50), edit score, accuracy, and average performance. Part (b) shows the results of the same ablation study on the Long-Term Action Anticipation (LTA) task, for different anticipation ratios (α = 0.2 and α = 0.3) and future prediction lengths (β = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5). The table shows that using the encoded features (E) yields the best performance in both TAS and LTA.

read the caption

Table S1: Conditioning features. (a) Results on TAS (b) Results on LTA

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies on different types of conditioning features used in ActFusion. It shows the performance of the model on both TAS (Temporal Action Segmentation) and LTA (Long-Term Action Anticipation) tasks when using different input feature types for conditioning the decoder. The three conditioning features considered are: 1. F’: Masked visual features. 2. E: Embedded tokens generated by the encoder. 3. Â’: Action labels predicted by the encoder. The results indicate the effectiveness of using encoder-generated embeddings (E) for conditioning, outperforming the use of masked features or encoder predictions alone on both TAS and LTA.

read the caption

Table S1: Conditioning features

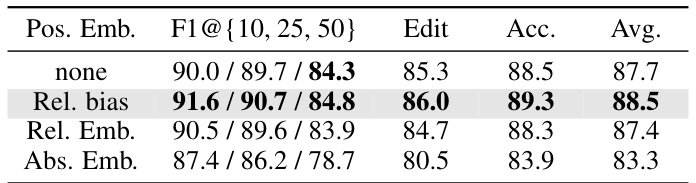

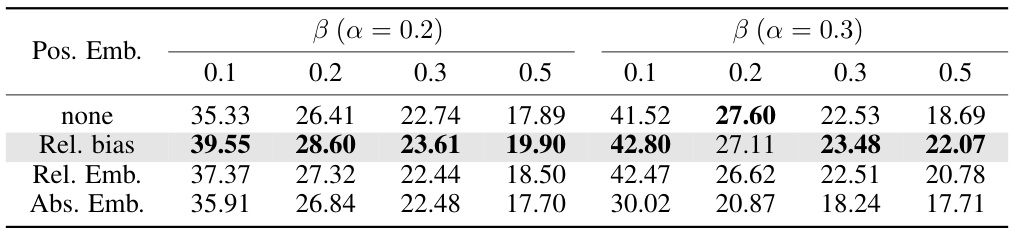

🔼 This table presents ablation study results on different types of position embeddings used in the ActFusion model. It compares the performance of the model using relative position bias, relative position embedding, absolute position embedding, and no position embedding across various metrics on the 50 Salads dataset for both TAS and LTA tasks. The results show that using relative position bias significantly improves the performance compared to other methods.

read the caption

Table S2: Position embedding

🔼 This table presents ablation study results on different types of position embeddings used in the ActFusion model. It compares the performance of using no position embedding, relative position bias, relative position embedding, and absolute position embedding on both the action segmentation (TAS) and action anticipation (LTA) tasks. The results are presented separately for different anticipation ratios (β) and observation ratios (α).

read the caption

Table S2: Position embedding

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion against other state-of-the-art models on three benchmark datasets for Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS). The metrics used include F1 scores at different thresholds (F1@{10, 25, 50}), edit score, average accuracy, and frame-wise accuracy. ActFusion’s superior performance across all metrics and datasets showcases its effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with state of the art on TAS. The overall results demonstrate the efficacy of ActFusion on TAS, achieving state-of-the-art performance across benchmark datasets. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

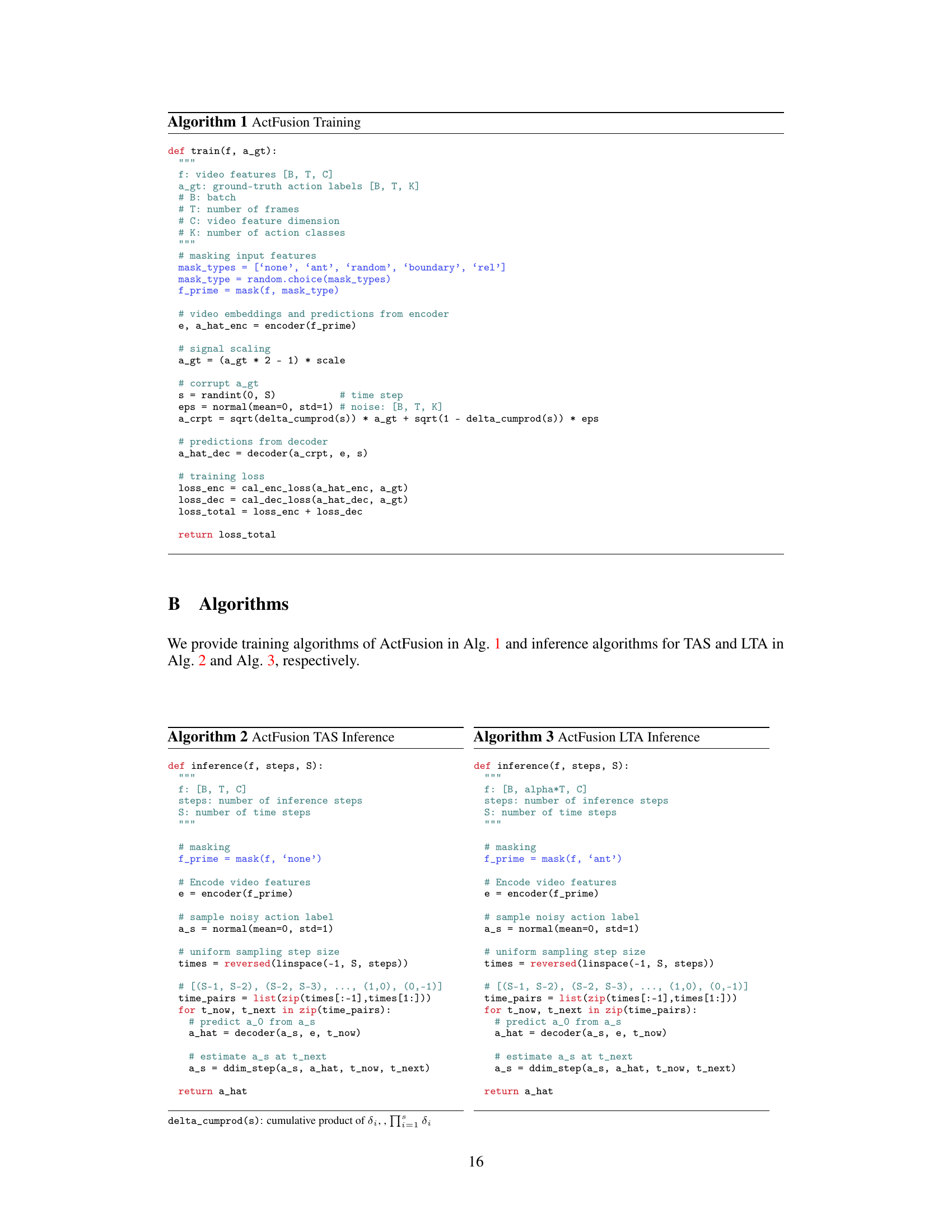

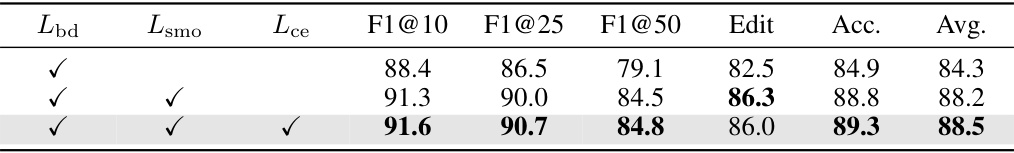

🔼 This table presents ablation study results on the effects of different loss functions (boundary loss, smoothing loss, and cross-entropy loss) on the performance of the ActFusion model. The results are shown for both action segmentation (TAS) and long-term action anticipation (LTA) tasks, with the performance measured across various anticipation ratios (β) and observation ratios (α). The table helps to understand the contribution of each loss component to the overall model performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Loss ablations

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion with other state-of-the-art methods on three benchmark datasets for temporal action segmentation (TAS): 50 Salads, Breakfast, and GTEA. The metrics used for comparison are F1 scores at different thresholds (10, 25, 50), edit score, and average accuracy. ActFusion achieves the highest accuracy across all three datasets and most metrics, demonstrating its superior performance in TAS.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with state of the art on TAS. The overall results demonstrate the efficacy of ActFusion on TAS, achieving state-of-the-art performance across benchmark datasets. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

🔼 This table compares the performance of ActFusion with other state-of-the-art models on three benchmark datasets for Temporal Action Segmentation (TAS): 50 Salads, Breakfast, and GTEA. The metrics used for comparison are F1 scores at different thresholds (10, 25, 50), edit score, and average accuracy. ActFusion achieves the highest accuracy across all datasets and metrics, demonstrating its superiority in TAS.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with state of the art on TAS. The overall results demonstrate the efficacy of ActFusion on TAS, achieving state-of-the-art performance across benchmark datasets. Bold values represent the highest accuracy, while underlined values indicate the second-highest accuracy.

Full paper#