TL;DR#

Multi-instance partial-label learning (MIPL) faces challenges due to inexact supervision in both instance and label spaces, often resulting in suboptimal model performance. Existing algorithms struggle to manage margins between attention scores and predicted probabilities, leading to misclassifications as the highest prediction probability may fall on a non-candidate label. This problem is particularly crucial in applications like medical image analysis where misclassification could have severe consequences.

To address these issues, the paper proposes MIPLMA, which introduces a margin-aware attention mechanism to dynamically adjust margins for attention scores, and a margin distribution loss to constrain margins between candidate and non-candidate labels. Experiments demonstrate MIPLMA’s superior performance against existing MIPL, MIL, and PLL algorithms on benchmark datasets and a real-world colorectal cancer classification task. The algorithm effectively reduces margin violations, improves generalization, and tackles the dual inexact supervision challenge inherent in MIPL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in weakly supervised learning, particularly those working with multi-instance and partial-label data. It introduces a novel algorithm that significantly improves accuracy by addressing margin violations, a common problem in these settings. This opens avenues for enhancing model generalization and tackling real-world challenges where obtaining precise labels is expensive or impractical.

Visual Insights#

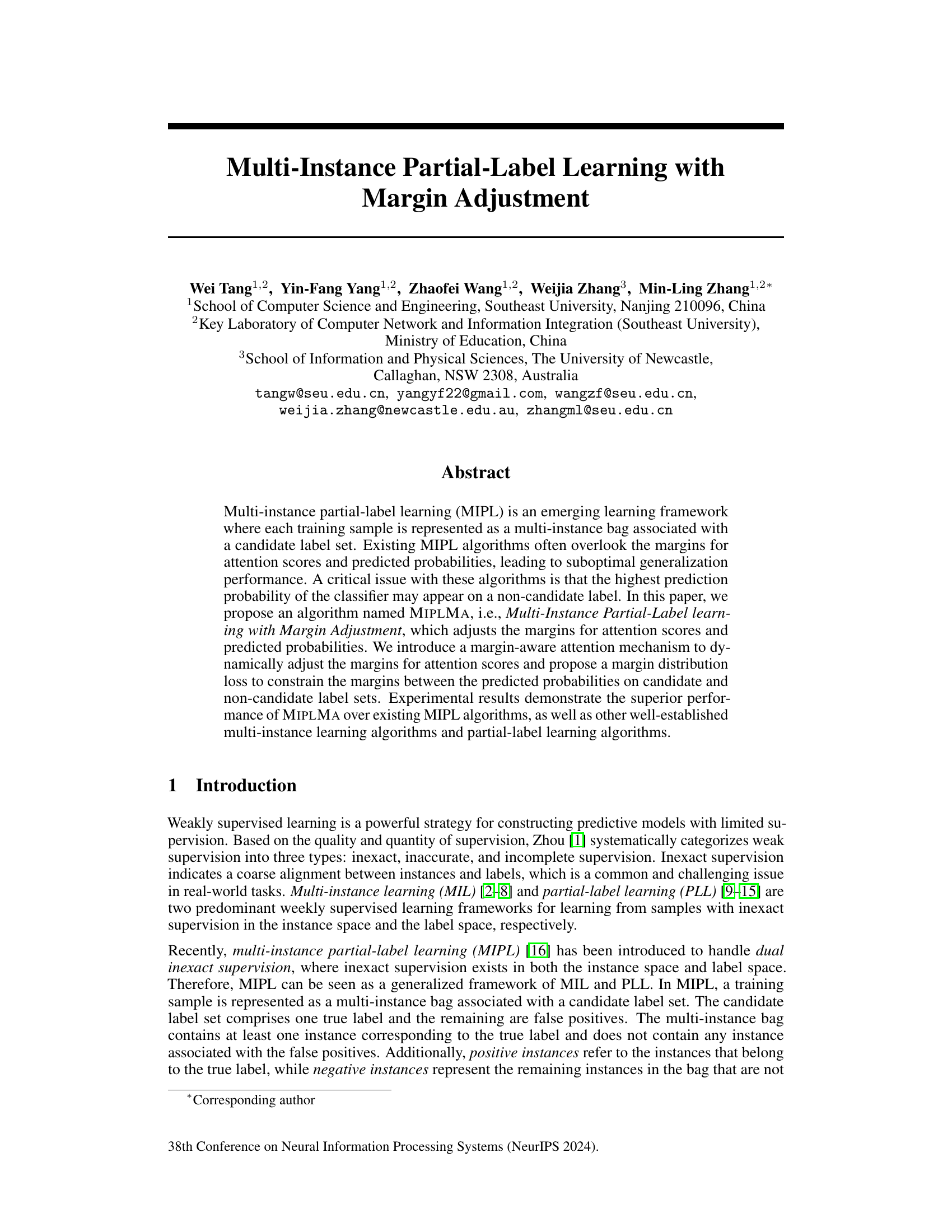

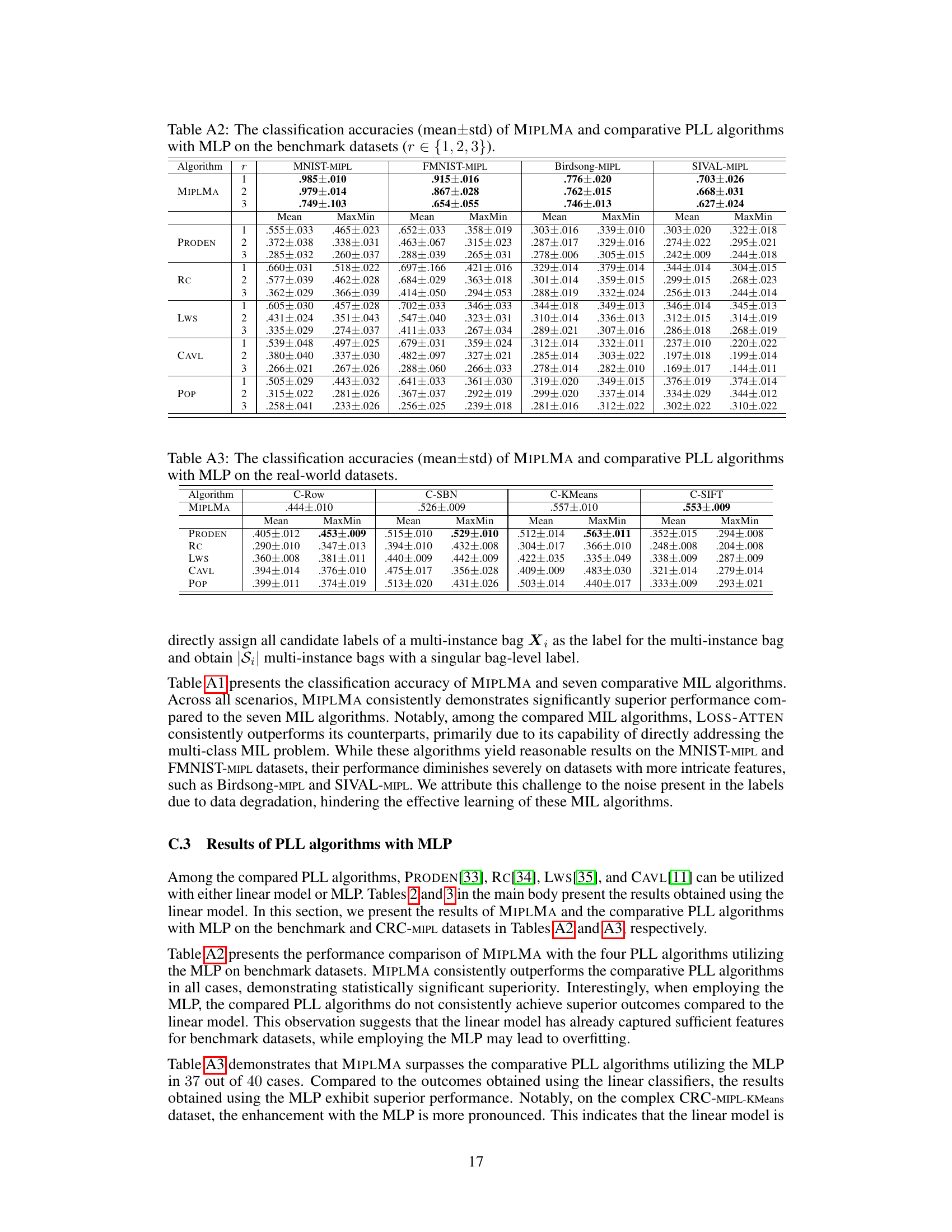

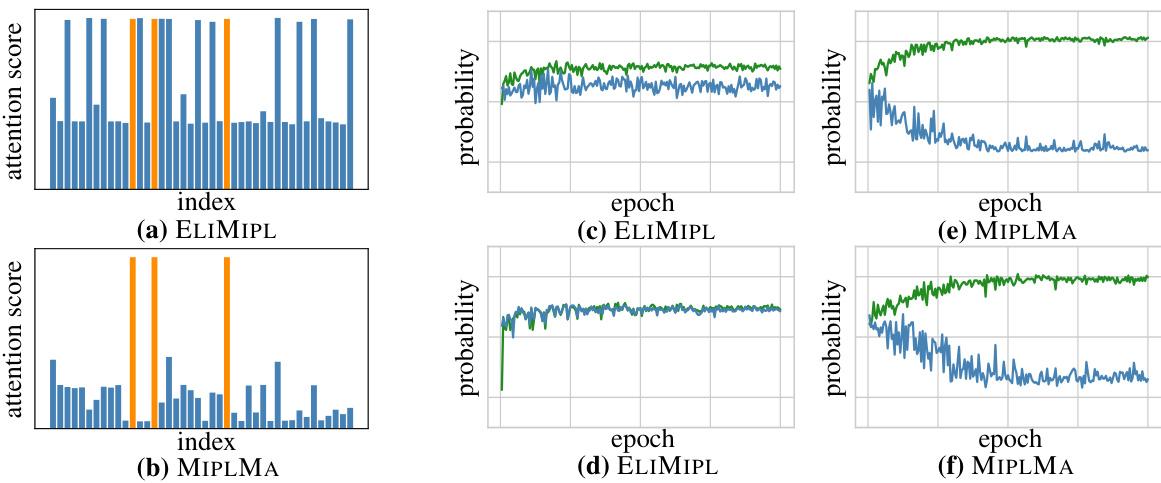

🔼 This figure illustrates the problem of margin violations in both instance and label space that existing MIPL algorithms suffer from. Subfigures (a) and (b) compare the attention scores given to positive and negative instances by ELIMIPL and MIPLMA, respectively. Subfigures (c) to (f) compare the highest predicted probabilities given to candidate and non-candidate labels by both algorithms across two different training bags. The comparison highlights how MIPLMA addresses the issue of margin violation by increasing the margin between positive and negative instances as well as candidate and non-candidate labels.

read the caption

Figure 1: Margin violations in the instance space and the label space. (a) and (b) depict the attention scores of ELIMIPL and MIPLMA for the same test bag in the FMNIST-MIPL dataset. Orange and blue colors indicate attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances, respectively. (c)-(f) show the highest predicted probabilities for candidate labels (green) and non-candidate labels (blue) by ELIMIPL or MIPLMA in the CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. (c) and (e) correspond to the same training bag, while (d) and (f) refer to another training bag.

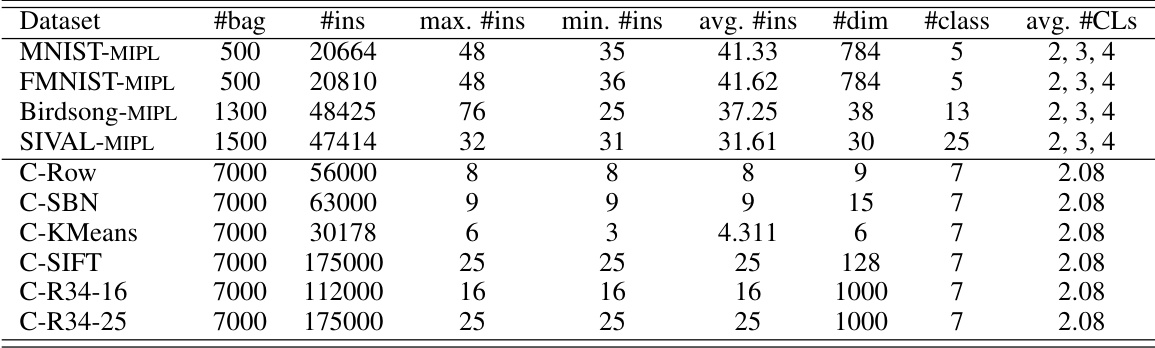

🔼 This table presents a detailed overview of the characteristics of eight datasets used in the paper’s experiments. These include four benchmark datasets (MNIST-MIPL, FMNIST-MIPL, Birdsong-MIPL, SIVAL-MIPL) and four real-world datasets derived from a colorectal cancer classification task (C-Row, C-SBN, C-KMeans, C-SIFT, C-R34-16, C-R34-25). For each dataset, the table lists the number of bags (#bag), the total number of instances (#ins), the maximum, minimum, and average number of instances per bag (max. #ins, min. #ins, avg. #ins), the dimensionality of the instance-level features (#dim), the number of classes (#class), and the average number of candidate labels per bag (avg. #CLs). This information is crucial for understanding the scale and complexity of the datasets used to evaluate the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and compare its performance against other methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Characteristics of the benchmark and real-world MIPL datasets.

In-depth insights#

Margin Violation Issue#

The concept of “margin violation” in the context of multi-instance partial-label learning (MIPL) refers to scenarios where the model’s predictions fail to maintain sufficient separation between relevant and irrelevant information. Specifically, margin violations occur when attention scores for negative instances surpass those of positive instances, or predicted probabilities for non-candidate labels exceed those of candidate labels. This undermines the model’s ability to accurately discriminate between the true label and false positives within a bag, leading to reduced generalization performance. Addressing margin violations is crucial as they hinder the learning process and compromise the model’s ability to reliably identify the true label from a set of candidate labels. Existing MIPL algorithms frequently overlook this issue, resulting in suboptimal results. The core idea behind the proposed margin adjustment mechanism is to dynamically control these margins, improving the classifier’s ability to differentiate between relevant and irrelevant information, leading to better generalization and increased accuracy.

MIPLMA Algorithm#

The MIPLMA algorithm tackles the challenges of Multi-instance Partial-Label Learning (MIPL) by directly addressing margin violations in both instance and label spaces. Margin violations, where attention scores for negative instances surpass those of positive instances, or where predicted probabilities for non-candidate labels exceed those for candidate labels, hinder model generalization. MIPLMA introduces a margin-aware attention mechanism to dynamically adjust margins for attention scores, ensuring positive instances receive higher attention. Furthermore, a margin distribution loss is introduced to constrain the margins between predicted probabilities on candidate and non-candidate labels, maximizing the margin and minimizing the variance. This dual margin adjustment significantly improves the algorithm’s performance, outperforming existing MIPL, MIL, and PLL algorithms in various experiments, showcasing its effectiveness in handling the complexities of dual inexact supervision inherent in MIPL problems. The algorithm’s end-to-end nature and the margin-aware adjustments form the core innovation, offering a novel and effective strategy for MIPL. Experimental results consistently demonstrate the superiority of MIPLMA. The algorithm’s ability to dynamically adapt margins based on the data significantly enhances its robustness and generalization capabilities.

Attention Mechanism#

The paper introduces a novel margin-aware attention mechanism to dynamically adjust attention scores, addressing limitations of existing methods. Existing methods often struggle to differentiate between positive and negative instances, especially in the early stages of training. The proposed mechanism uses a temperature parameter to control the distribution of attention scores, sharpening the focus on positive instances as training progresses. This dynamic adjustment enhances the model’s ability to distinguish between instances, improving overall performance. The use of a margin-aware approach is crucial for effectively handling the dual inexact supervision inherent in multi-instance partial-label learning (MIPL). The mechanism effectively reduces supervision inexactness by dynamically adjusting margins in both instance and label spaces, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability. The mechanism’s permutation invariance ensures the algorithm’s robustness to the order of instances within bags, a critical property for multi-instance learning algorithms. Overall, the proposed attention mechanism is a key component of the superior performance achieved by the new MIPL algorithm.

Margin Distribution Loss#

The proposed margin distribution loss is a crucial component of the MIPLMA algorithm, designed to address margin violations in the label space. It goes beyond simply maximizing the difference between the highest predicted probabilities for candidate and non-candidate labels (margin mean), by also minimizing the variance of these margins. This dual approach is key to enhancing model generalization, preventing overconfidence in predictions and improving robustness. The loss function dynamically adjusts margins, effectively reducing the impact of noisy or ambiguous label information. The integration of the margin distribution loss with the dynamic disambiguation loss demonstrates a synergistic approach to handling dual inexact supervision inherent in MIPL problems. The success of MIPLMA underscores the effectiveness of this novel loss function and its contribution to improving the accuracy and reliability of multi-instance partial-label learning models. The use of both mean and variance of margins in the loss function represents a significant advancement over previous methods that focused solely on the mean, making it more robust to variations in the distribution of probabilities.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on multi-instance partial-label learning (MIPL) with margin adjustment could involve several key areas. Extending the algorithm to handle larger datasets more efficiently is crucial, perhaps through exploring more sophisticated optimization techniques or distributed computing methods. Another promising avenue is improving the interpretability of the model, possibly by visualizing attention weights or developing methods for explaining individual predictions. Furthermore, investigating the sensitivity of the algorithm to hyperparameter choices and developing more robust and automated tuning methods would be beneficial. Finally, applying the margin adjustment technique to other weakly supervised learning paradigms, such as partial label learning or noisy label learning, and evaluating its effectiveness across different datasets and tasks could yield significant insights. Investigating the theoretical properties and generalization bounds of the proposed algorithm would provide a deeper understanding of its performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed MIPLMA algorithm. It shows how multi-instance bags (Xᵢ) and their associated candidate label sets (Sᵢ) are processed. The process starts with extracting instance-level features (Hᵢ) using a feature extractor (ψ). A margin-aware attention mechanism aggregates these features into a bag-level representation (zᵢ), dynamically adjusting margins for attention scores. Simultaneously, predicted probabilities (pᵢ) are generated and their margins are adjusted using a margin distribution loss (Lₘ) and a dynamic disambiguation loss (Lₐ). These losses guide the classifier in accurately predicting the true label from the candidate set.

read the caption

Figure 2: The MIPLMA framework processes an input comprising the multi-instance bag X₁ = {Xi,1, Xi,2,, X₁,9} and the candidate label set S₁ = {2, 3, 5, 7}, where La and Lm represent the dynamic disambiguation loss and the margin distribution loss, respectively.

🔼 This figure shows examples of margin violations in both instance and label spaces during the training process of two multi-instance partial-label learning (MIPL) algorithms, ELIMIPL and the proposed MIPLMA. The top row illustrates how attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances can be very close (a,b), whereas the bottom row depicts scenarios where the model assigns its highest predicted probability to a non-candidate label. MIPLMA aims to mitigate such violations.

read the caption

Figure 1: Margin violations in the instance space and the label space. (a) and (b) depict the attention scores of ELIMIPL and MIPLMA for the same test bag in the FMNIST-MIPL dataset. Orange and blue colors indicate attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances, respectively. (c)-(f) show the highest predicted probabilities for candidate labels (green) and non-candidate labels (blue) by ELIMIPL or MIPLMA in the CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. (c) and (e) correspond to the same training bag, while (d) and (f) refer to another training bag.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the margin violations in both instance and label spaces by comparing ELIMIPL and MIPLMA. The first row shows the attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances for a test bag in FMNIST-MIPL dataset. The second row shows the highest predicted probabilities for candidate and non-candidate labels by ELIMIPL and MIPLMA on two different training bags in CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. It visually illustrates how MIPLMA effectively addresses the margin violation issues, which were commonly observed in previous MIPL algorithms.

read the caption

Figure 1: Margin violations in the instance space and the label space. (a) and (b) depict the attention scores of ELIMIPL and MIPLMA for the same test bag in the FMNIST-MIPL dataset. Orange and blue colors indicate attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances, respectively. (c)-(f) show the highest predicted probabilities for candidate labels (green) and non-candidate labels (blue) by ELIMIPL or MIPLMA in the CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. (c) and (e) correspond to the same training bag, while (d) and (f) refer to another training bag.

🔼 This figure illustrates the problem of margin violations in both instance and label spaces that existing MIPL algorithms often suffer from. The top row shows attention scores for instances within a bag, highlighting how ELIMIPL assigns similar attention scores to positive and negative instances, while MIPLMA better distinguishes them. The bottom row shows predicted probabilities for candidate and non-candidate labels, demonstrating that ELIMIPL can assign higher probability to a non-candidate label than a candidate label, while MIPLMA shows better separation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Margin violations in the instance space and the label space. (a) and (b) depict the attention scores of ELIMIPL and MIPLMA for the same test bag in the FMNIST-MIPL dataset. Orange and blue colors indicate attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances, respectively. (c)-(f) show the highest predicted probabilities for candidate labels (green) and non-candidate labels (blue) by ELIMIPL or MIPLMA in the CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. (c) and (e) correspond to the same training bag, while (d) and (f) refer to another training bag.

🔼 This figure shows how the classification accuracy of the MIPLMA algorithm varies with different values of the hyperparameter λ (lambda) on the Birdsong-MIPL dataset for different numbers of false positive labels (r). The plot indicates that the optimal value of λ for achieving the highest accuracy depends on the number of false positives. The error bars represent the standard deviations of the accuracy across multiple runs.

read the caption

Figure A3: The classification accuracies (mean and std) of MIPLMA with varying λ on Birdsong-MIPL dataset (r ∈ {1, 2, 3}). The diameter of the circle represents the relative standard deviation.

🔼 The figure visualizes margin violations in instance and label spaces, comparing ELIMIPL and MIPLMA. Subfigures (a) and (b) show attention scores (positive instances in orange, negative in blue) for a test bag in the FMNIST-MIPL dataset, highlighting MIPLMA’s improved margin. Subfigures (c) to (f) display the highest predicted probabilities for candidate (green) vs. non-candidate (blue) labels in two different training bags from the CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. These demonstrate MIPLMA’s superior ability to maintain larger margins between candidate and non-candidate probabilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: Margin violations in the instance space and the label space. (a) and (b) depict the attention scores of ELIMIPL and MIPLMA for the same test bag in the FMNIST-MIPL dataset. Orange and blue colors indicate attention scores assigned to positive and negative instances, respectively. (c)-(f) show the highest predicted probabilities for candidate labels (green) and non-candidate labels (blue) by ELIMIPL or MIPLMA in the CRC-MIPL-Row dataset. (c) and (e) correspond to the same training bag, while (d) and (f) refer to another training bag.

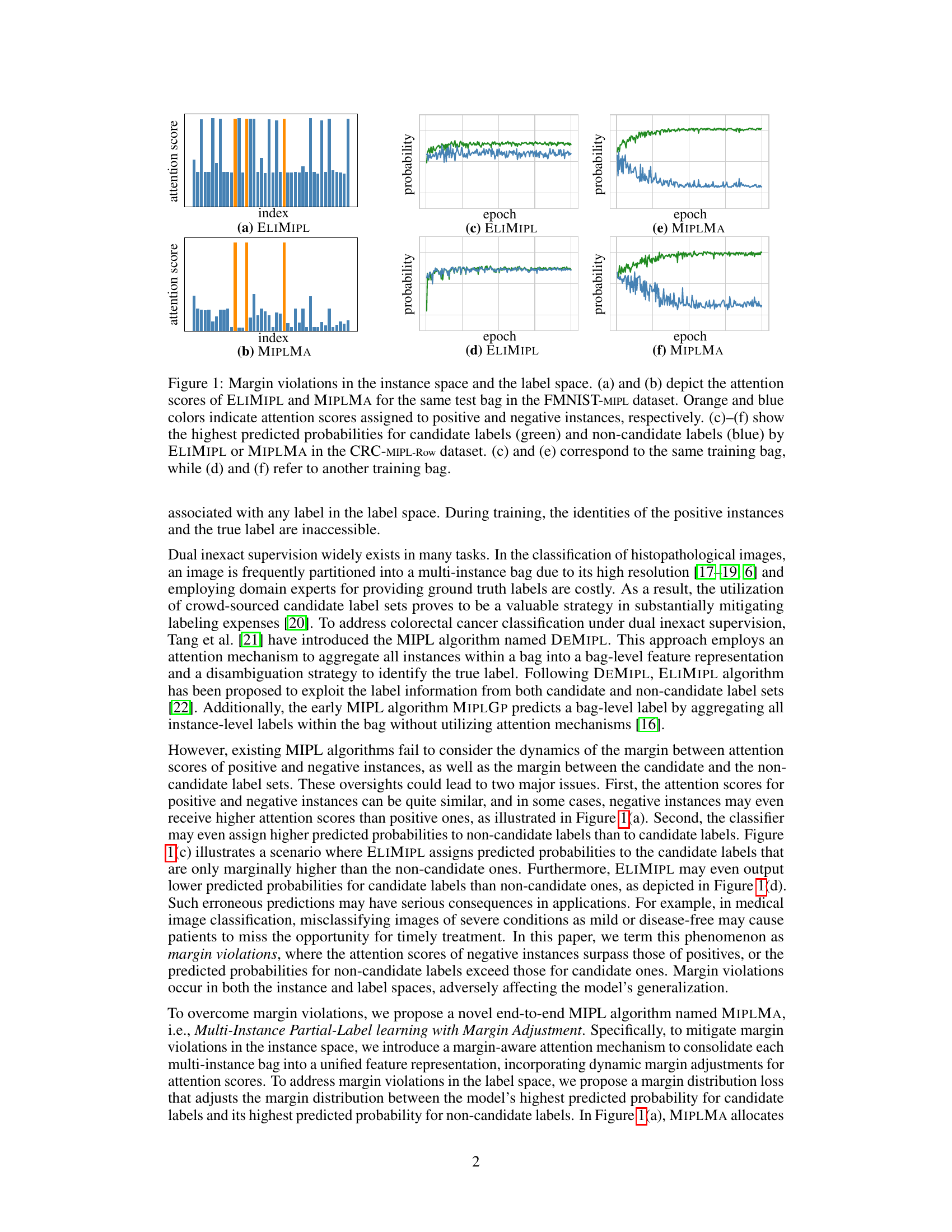

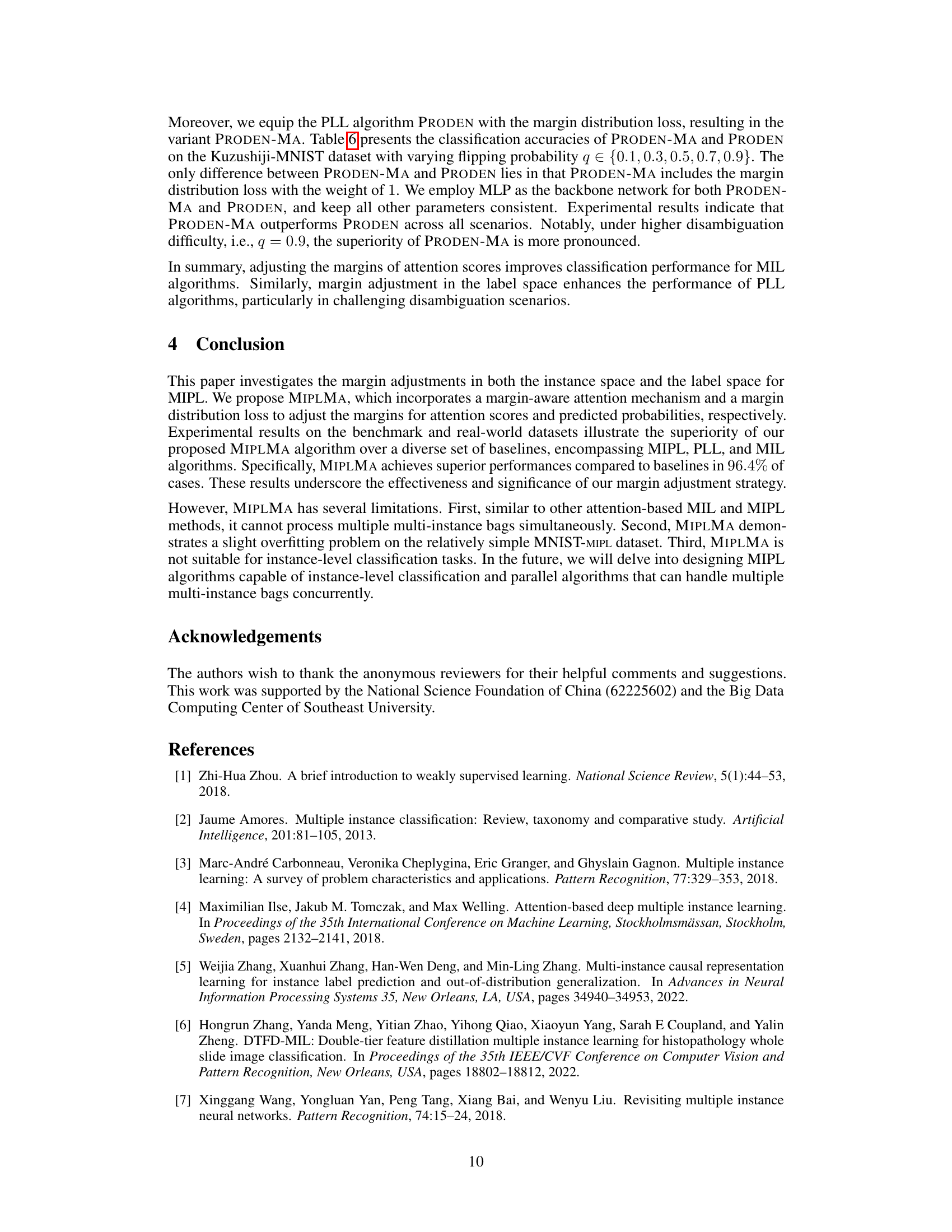

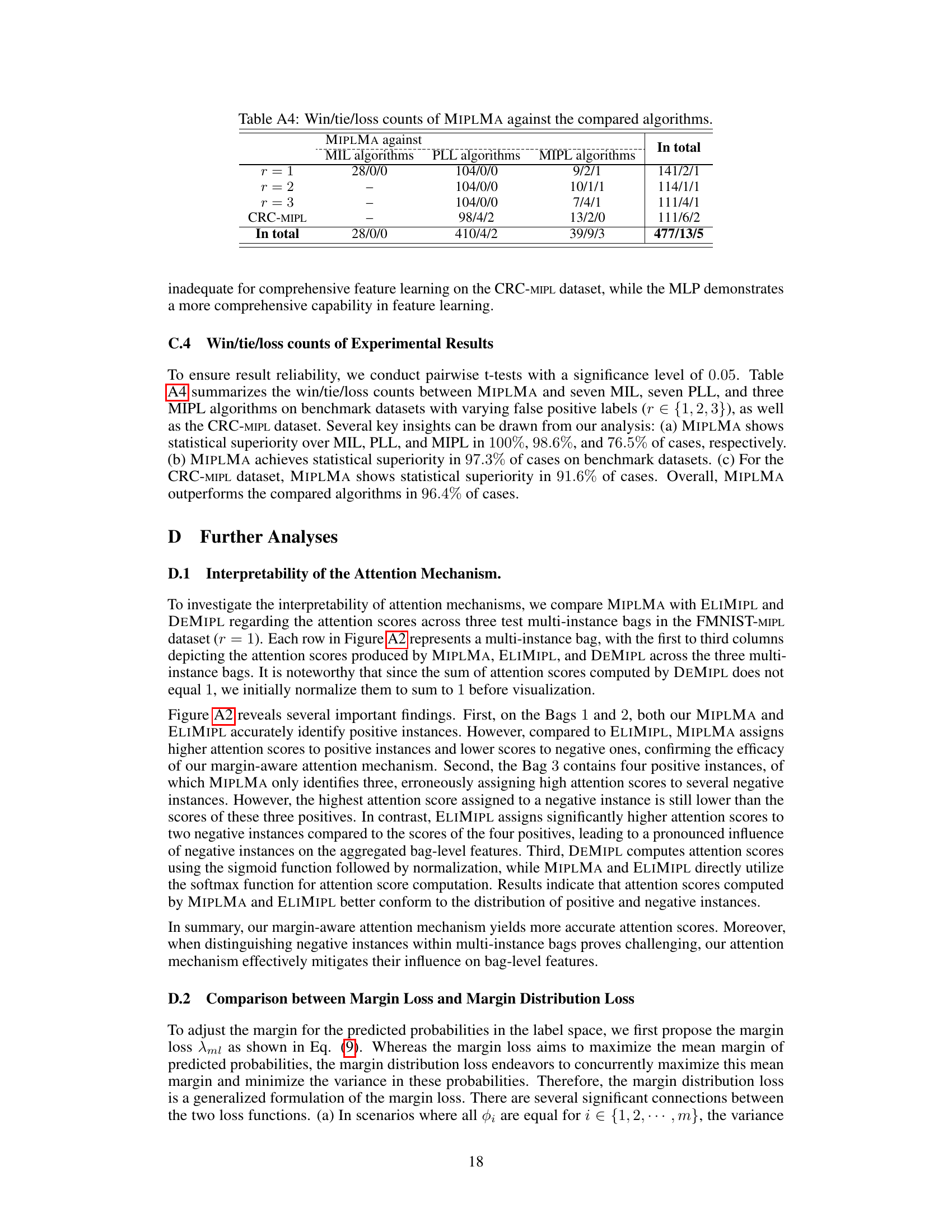

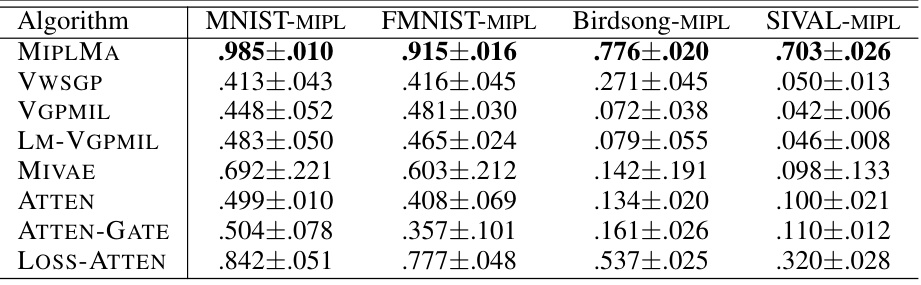

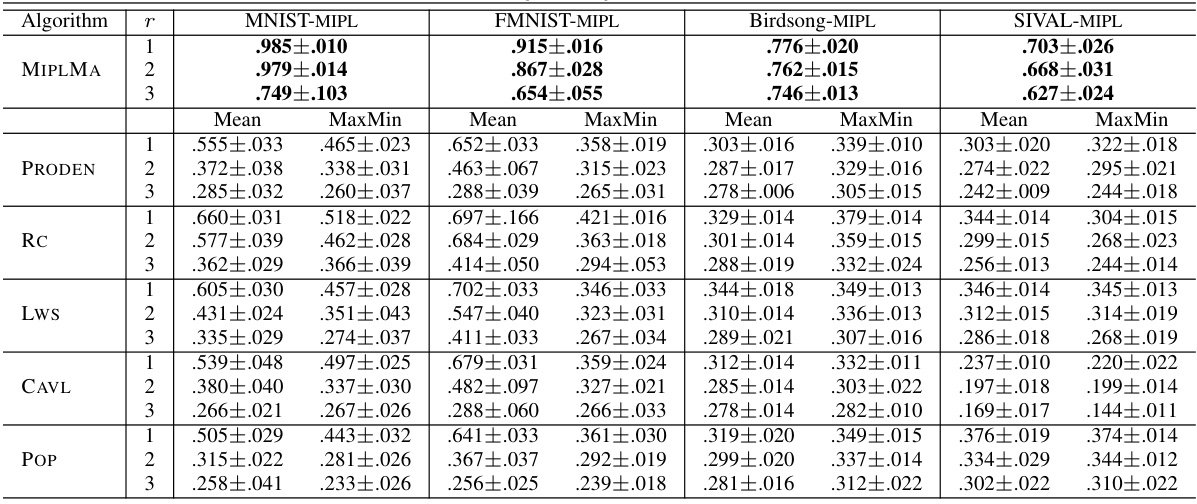

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the mean and standard deviation of classification accuracies achieved by the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and several other algorithms (ELIMIPL, DEMIPL, MIPLGP, PRODEN, RC, Lws, CAVL, POP, PL-AGGD) across four benchmark datasets (MNIST-MIPL, FMNIST-MIPL, Birdsong-MIPL, SIVAL-MIPL). The results are shown for different numbers of false positive labels (r = 1, 2, 3), offering a comparison of performance under varying levels of label noise.

read the caption

Table 2: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the benchmark datasets with the varying numbers of false positive labels (r ∈ {1, 2, 3}).

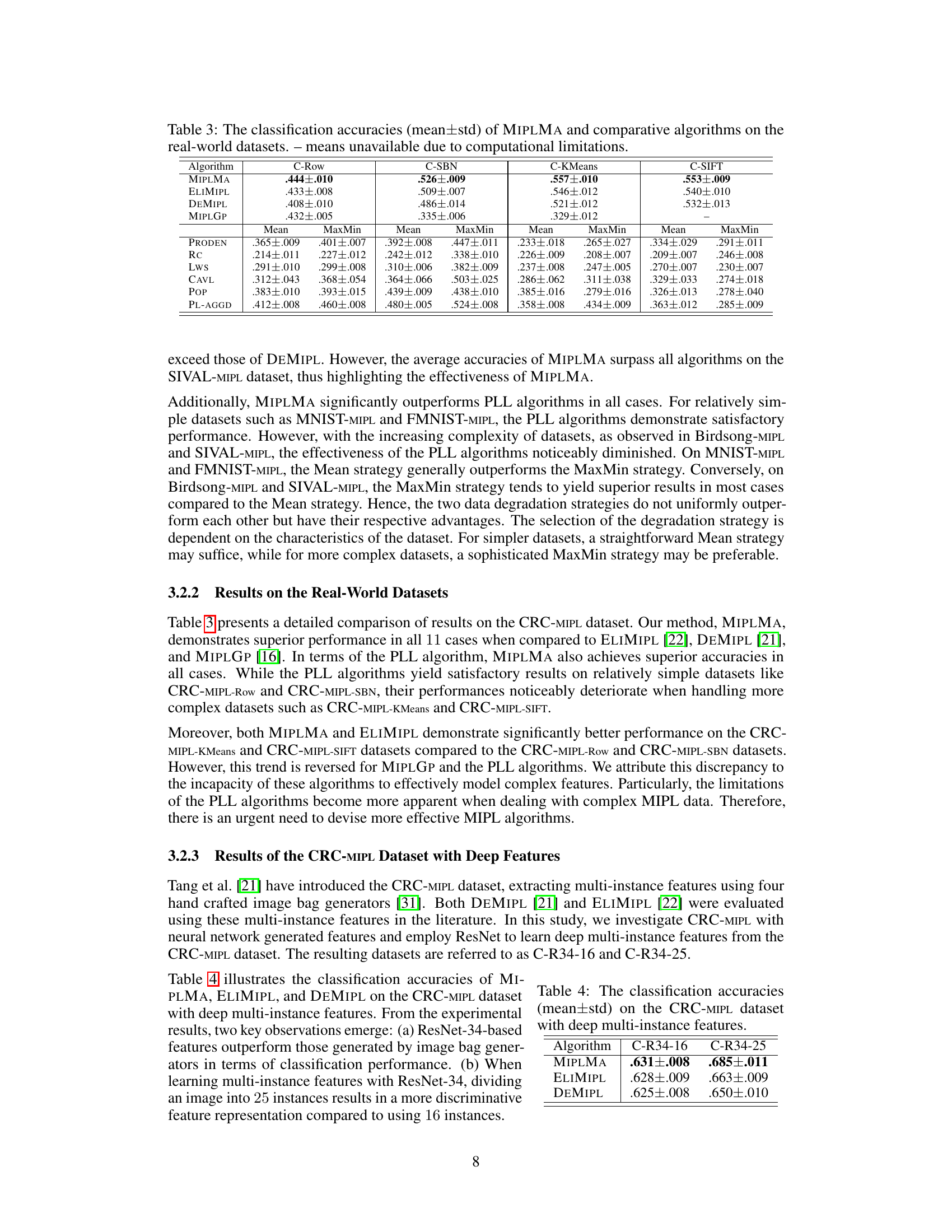

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracies achieved by the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and several other comparative algorithms on four real-world datasets. Each dataset is a variation of the CRC-MIPL dataset, which is based on colorectal cancer classification. The variations differ in how the multi-instance features are extracted. The table shows the average accuracy and standard deviation across multiple runs. It allows for comparison of MIPLMA against other algorithms including those based on Multi-Instance Learning (MIL) and Partial-Label Learning (PLL).

read the caption

Table 3: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the real-world datasets.

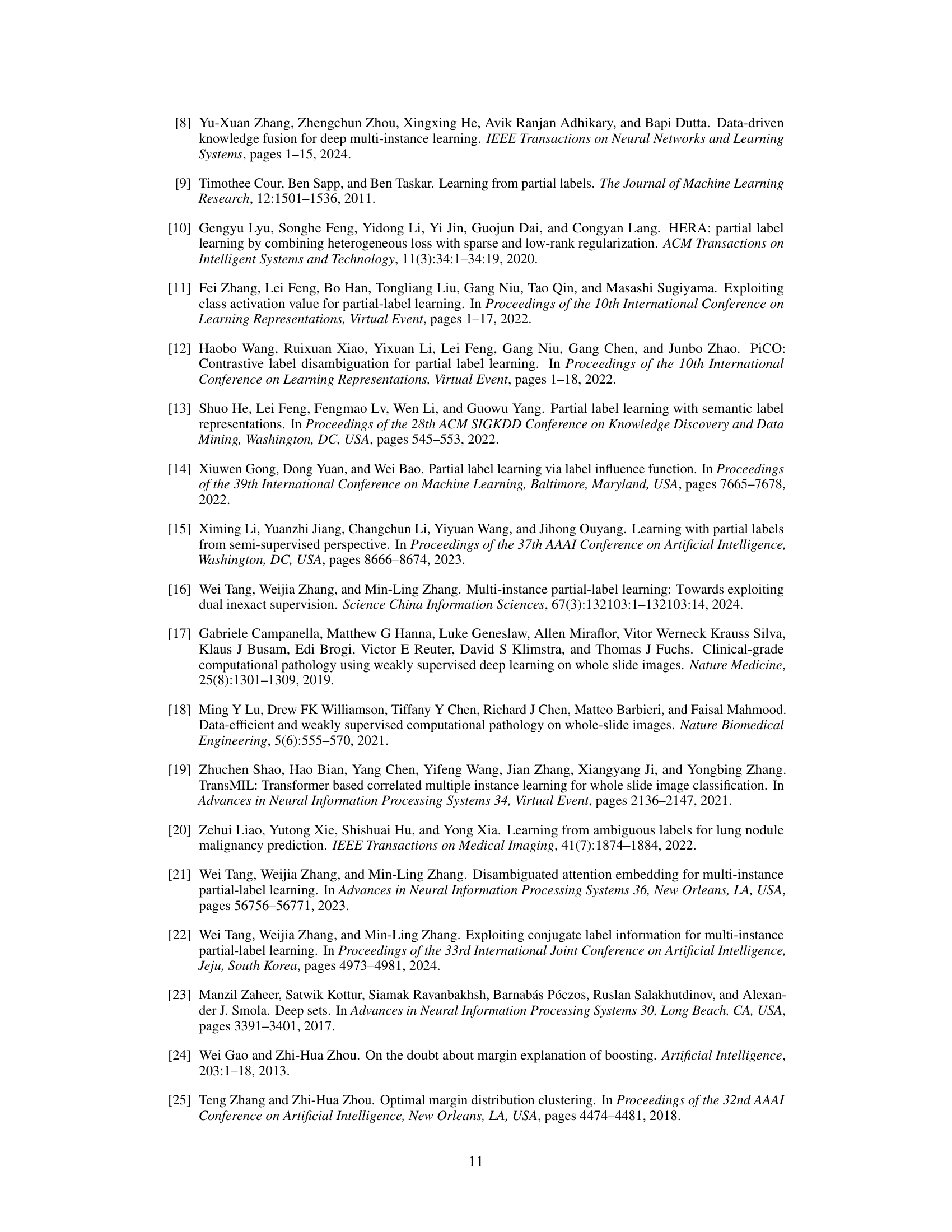

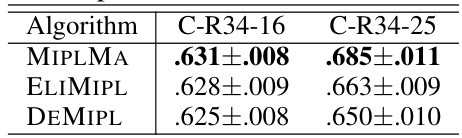

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracies achieved by MIPLMA, ELIMIPL, and DEMIPL on the CRC-MIPL dataset using deep multi-instance features extracted with ResNet-34. It shows the performance of the algorithms on two variations of the dataset: C-R34-16 (ResNet-34 with 16 image patches per image bag) and C-R34-25 (ResNet-34 with 25 image patches per image bag). The results demonstrate the superior performance of MIPLMA, which consistently outperforms the other two algorithms across both variations.

read the caption

Table 4: The classification accuracies (mean±std) on the CRC-MIPL dataset with deep multi-instance features.

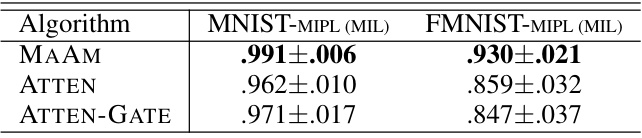

🔼 This table presents the mean and standard deviation of classification accuracies achieved by three different algorithms (MAAM, ATTEN, and ATTEN-GATE) on two MIL datasets (MNIST-MIPL and FMNIST-MIPL). The results show the performance of these algorithms when using only bag-level true labels, not the instance-level or candidate label set information used in other parts of the paper. MAAM significantly outperforms the other two algorithms.

read the caption

Table 5: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MAAM, ATTEN, and ATTEN-GATE on the MIL datasets with bag-level true labels.

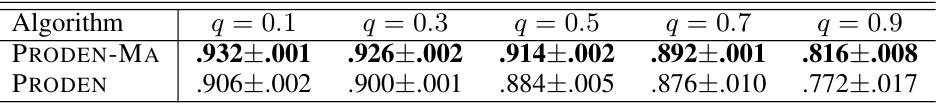

🔼 This table shows the classification accuracy comparison between two algorithms, PRODEN-MA and PRODEN, on the Kuzushiji-MNIST dataset under different levels of label noise. PRODEN-MA incorporates the margin distribution loss proposed in the paper, while PRODEN is the baseline algorithm. The results are presented in terms of mean accuracy and standard deviation across multiple runs for each flipping probability (q).

read the caption

Table 6: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of PRODEN-MA and PRODEN on the Kuzushiji-MNIST dataset with varying flipping probability q.

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracies of the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and several other algorithms (ELIMIPL, DEMIPL, MIPLGP, PRODEN, RC, Lws, CAVL, POP, PL-AGGD) across four benchmark datasets (MNIST-MIPL, FMNIST-MIPL, Birdsong-MIPL, SIVAL-MIPL). The results are shown for different numbers of false positive labels (r=1, 2, 3), demonstrating the performance of each algorithm under varying levels of label noise.

read the caption

Table 2: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the benchmark datasets with the varying numbers of false positive labels (r ∈ {1, 2, 3}).

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracy results of the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and several other algorithms (including ELIMIPL, DEMIPL, MIPLGP, PRODEN, RC, LWS, CAVL, POP, and PL-AGGD) on four benchmark datasets (MNIST-MIPL, FMNIST-MIPL, Birdsong-MIPL, and SIVAL-MIPL). The results are shown for different numbers of false positive labels (r=1, 2, 3), demonstrating the performance of each algorithm under varying levels of label noise.

read the caption

Table 2: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the benchmark datasets with the varying numbers of false positive labels (r ∈ {1, 2, 3}).

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracies achieved by MIPLMA and several other algorithms on four real-world datasets related to colorectal cancer classification. Each dataset has different types of multi-instance features extracted using different methods. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy across multiple runs of the algorithms, and it allows comparison of the performance of MIPLMA against other methods on the same datasets. Note that some values are marked as unavailable due to computational constraints.

read the caption

Table 3: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the real-world datasets.

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracies of the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and several other algorithms (ELIMIPL, DEMIPL, MIPLGP, PRODEN, RC, Lws, CAVL, POP, PL-AGGD) on four benchmark datasets (MNIST-MIPL, FMNIST-MIPL, Birdsong-MIPL, SIVAL-MIPL). The results are shown for different numbers of false positive labels (r = 1, 2, 3), indicating the robustness of each algorithm under varying levels of label noise. The mean and standard deviation of the accuracy across multiple runs are provided.

read the caption

Table 2: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the benchmark datasets with the varying numbers of false positive labels (r ∈ {1, 2, 3}).

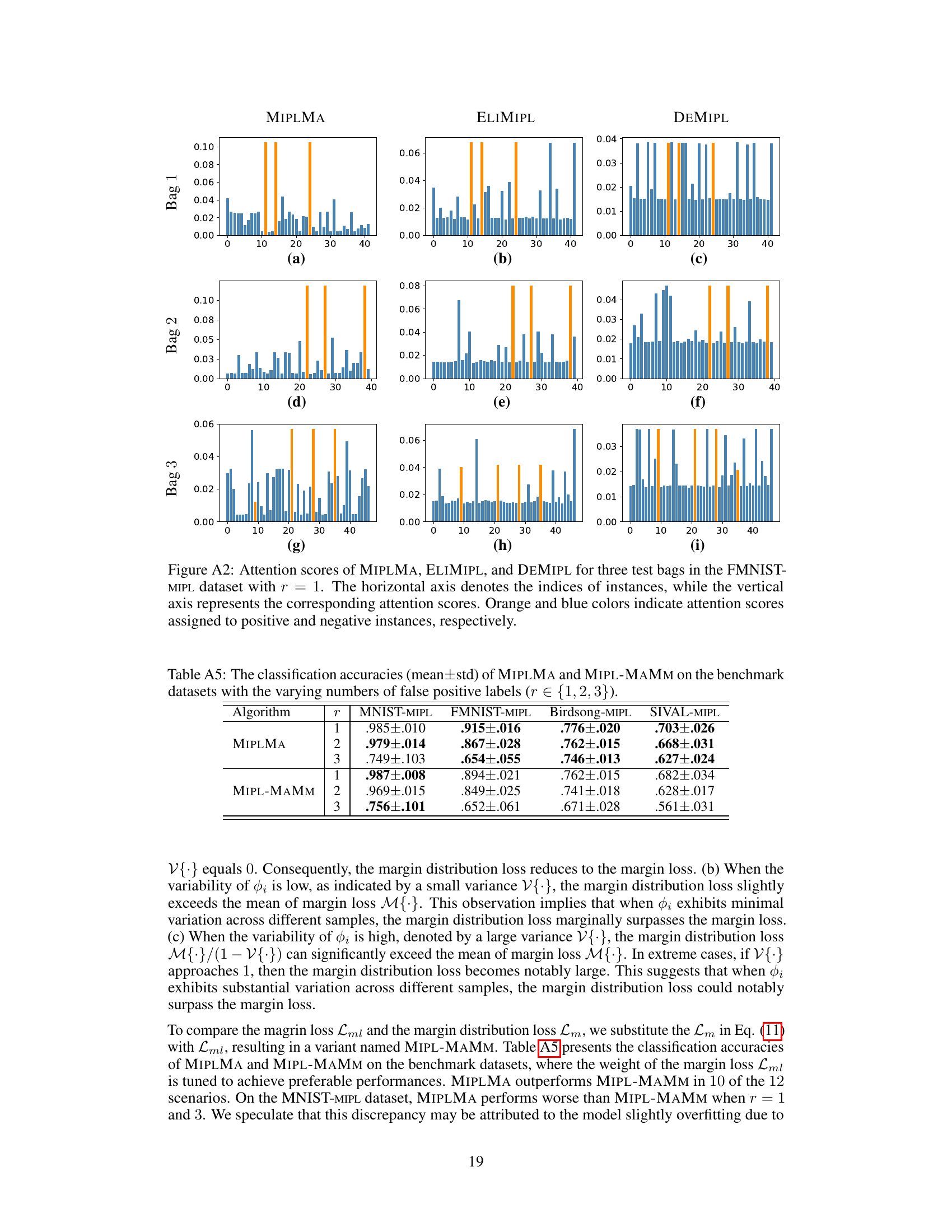

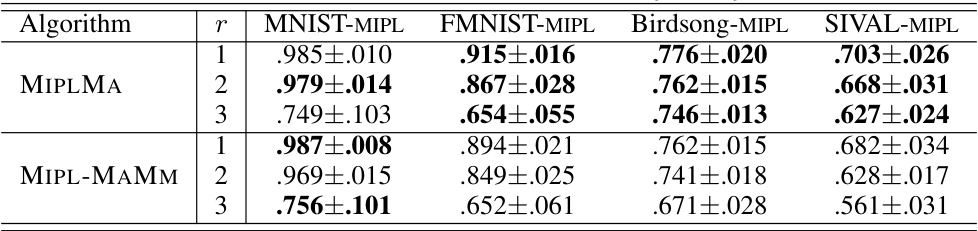

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracies achieved by MIPLMA and its variant MIPL-MAMM on four benchmark datasets. The performance is evaluated across different numbers of false positive labels (r). The results show the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy across multiple runs, providing a statistical assessment of the algorithm’s performance under different conditions. Comparing the results of MIPLMA and MIPL-MAMM allows for an evaluation of the impact of the margin distribution loss implemented in MIPLMA.

read the caption

Table A5: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and MIPL-MAMM on the benchmark datasets with the varying numbers of false positive labels (r ∈ {1,2,3}).

🔼 This table presents the classification accuracy results for the proposed MIPLMA algorithm and several other algorithms on four benchmark datasets (MNIST-MIPL, FMNIST-MIPL, Birdsong-MIPL, and SIVAL-MIPL). The results are shown for three different settings of the number of false positive labels (r = 1, 2, and 3). The table helps to demonstrate the performance of MIPLMA against other state-of-the-art algorithms in a multi-instance partial-label learning setting.

read the caption

Table 2: The classification accuracies (mean±std) of MIPLMA and comparative algorithms on the benchmark datasets with the varying numbers of false positive labels (r ∈ {1, 2, 3}).

Full paper#