TL;DR#

Many real-world optimization problems involve M-concave functions, which are fundamental in economics and discrete mathematics. However, perfect knowledge of these functions is often unavailable, leading to interactive optimization based on feedback. This necessitates the study of online M-concave function maximization, a topic with limited prior research. This paper directly tackles this issue by investigating the problem under two different settings.

This research explores online M-concave function maximization in stochastic bandit and adversarial full-information settings. For stochastic settings, the paper presents novel algorithms achieving low regret, leveraging the robustness of greedy algorithms. In contrast, it proves that for the adversarial full-information setting, achieving sublinear regret is computationally hard, unless P=NP. These findings provide crucial insights for designing algorithms for online M-concave function maximization, establishing clear boundaries between computationally tractable and intractable scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the challenge of online M-concave function maximization, a prevalent problem in various fields like economics and operations research. By establishing both positive and negative results (efficient algorithms for stochastic settings and NP-hardness for adversarial ones), it provides a comprehensive understanding of this problem’s complexity and offers directions for future research. The paper’s findings significantly impact the design and analysis of online algorithms, especially in areas where function evaluations are noisy or only partially accessible.

Visual Insights#

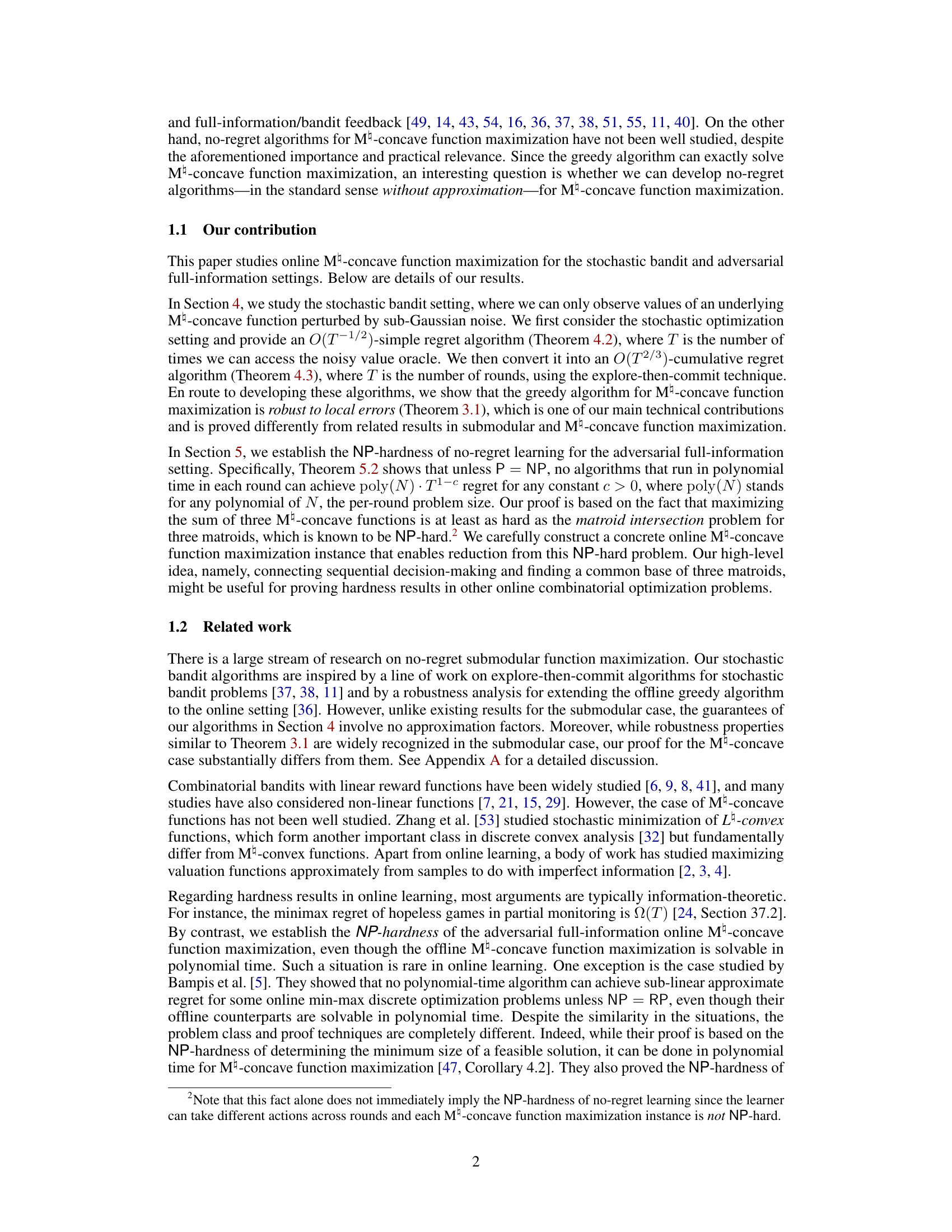

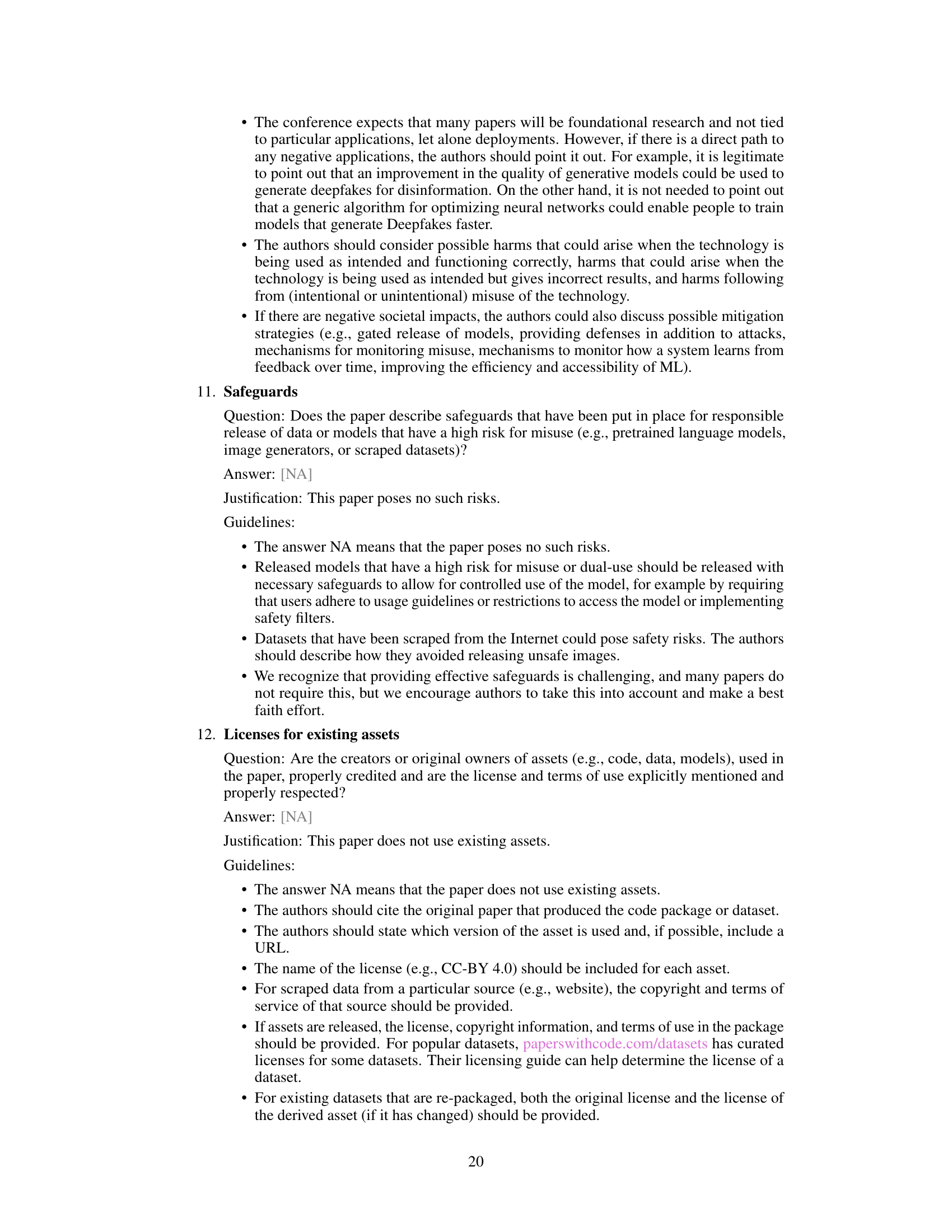

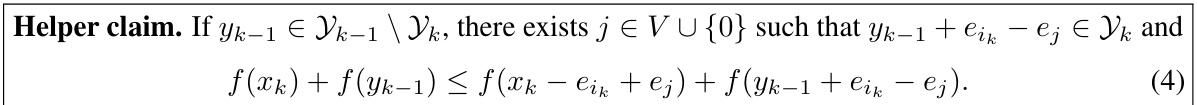

🔼 This figure shows the visualization of the sets Yk in a two-dimensional space (Z2). Each panel represents a different scenario, illustrating how the set of feasible points (Yk) changes depending on the choice of ik (update direction). The feasible region is a trapezoid, and the gray area represents the set of points reachable at each step of the algorithm. Case 1 shows the scenario where no update is made (ik = 0). Case 2 and 3 depict the scenarios when an update is performed (ik ≠ 0), showing the shift of Yk along the update direction ei₁. The figure aids in understanding the proof of Theorem 3.1, which establishes the robustness of the greedy algorithm to local errors in M-concave function maximization.

read the caption

Figure 1: Images of Yk on Z2. The set of integer points in the trapezoid is the feasible region X. Left: the gray area represents Yk−1 consisting of points reachable from Xk−1. Middle: if ik = 0 (case 1), Xk−1 = Xk holds and Yk−1 shrinks to Yk, the darker area, since the constraint on y(V) gets tighter. Right: if ik = i₁ (cases 2 and 3), the area, Yk, reachable from Xk = Xk−1 + ei₁ shifts along ei₁.

🔼 This figure illustrates the changes in the feasible region Yk as the algorithm progresses through iterations. It shows how the reachable area of feasible points shrinks (case 1, ik = 0) or shifts (cases 2 and 3, ik = i₁) depending on the choices made by the algorithm at each step.

read the caption

Figure 1: Images of Yk on Z². The set of integer points in the trapezoid is the feasible region X. Left: the gray area represents Yk−1 consisting of points reachable from Xk−1. Middle: if ik = 0 (case 1), Xk−1 = Xk holds and Yk−1 shrinks to Yk, the darker area, since the constraint on y(V) gets tighter. Right: if ik = i₁ (cases 2 and 3), the area, Yk, reachable from Xk = Xk−1 + ei₁ shifts along ei₁.

In-depth insights#

M-concave Maximization#

M-concave function maximization, a significant problem in discrete convex analysis and economics, presents unique challenges due to the function’s complex structure. Greedy algorithms, while effective for exact maximization under full information, become unreliable with noisy or adversarial data. This necessitates the development of robust algorithms that can handle uncertainty, particularly in stochastic bandit and adversarial full-information settings. The paper’s exploration of these settings reveals a stark contrast: positive results are achieved for stochastic bandits using an algorithm with O(T⁻¹/²) simple regret and O(T²/³) regret; however, the adversarial setting proves computationally intractable, demonstrating NP-hardness even with full-information feedback, unless P=NP. This highlights the fundamental difficulty of the problem and the critical need for further research, potentially exploring alternative algorithmic approaches or relaxing assumptions about data availability and quality.

Bandit Algorithm Robustness#

Analyzing the robustness of bandit algorithms is crucial for their real-world applicability, especially in settings with noisy or uncertain rewards. A robust algorithm should maintain a desired performance level even when faced with deviations from idealized assumptions. Understanding the sources of this robustness is essential, for example, whether it stems from the algorithm’s design or inherent properties of the underlying optimization problem. This includes investigating how sensitive the algorithm is to errors in reward observations, and evaluating its performance under various noise models. The exploration-exploitation trade-off also plays a significant role; robust algorithms often balance exploration to learn about the environment with exploitation to leverage existing knowledge, effectively navigating uncertainty. A key aspect is quantifying the robustness, perhaps through theoretical guarantees or empirical evaluations, to establish its effectiveness and reliability across different problem instances.

NP-Hardness Proof#

The NP-hardness proof section within a research paper would rigorously demonstrate that a specific problem related to online M-concave function maximization is computationally intractable unless P=NP. The core argument likely revolves around a reduction from a known NP-hard problem, such as the matroid intersection problem for three matroids. This reduction would involve a detailed construction showing how a solution to the matroid intersection problem can be efficiently transformed into a solution to the online M-concave function maximization problem and vice versa. The proof’s success hinges on demonstrating that this transformation preserves the problem’s computational complexity. A key aspect would be carefully constructing instances of the online problem that directly correspond to instances of the NP-hard problem, ensuring that the reduction works correctly for all possible inputs. The argument’s validity would rest upon demonstrating that a polynomial-time solution to the online problem would also yield a polynomial-time solution to the NP-hard problem, thus implying that P=NP (a widely believed false statement), and therefore the online problem is indeed NP-hard. The overall approach highlights the inherent complexity of this class of optimization problems in an online setting, even with full information available at each step.

Stochastic Regret Bounds#

Analyzing stochastic regret bounds in machine learning involves understanding the performance of algorithms under uncertainty. Stochasticity introduces noise or randomness into the learning process, impacting the accuracy of predictions. Regret, a measure of an algorithm’s cumulative performance relative to an optimal strategy, is crucial. Stochastic regret bounds mathematically quantify this performance gap, accounting for the probabilistic nature of the environment. Tight bounds are particularly valuable as they provide a clear understanding of achievable performance and inform algorithm design. In contrast, loose bounds may lack precision, failing to capture subtle complexities. The choice of bound (e.g., high probability or expectation) impacts the strength and interpretability. Research often focuses on developing algorithms that achieve optimal stochastic regret bounds, demonstrating theoretical efficiency. Furthermore, empirical validations are necessary to ensure theoretical results translate effectively to real-world scenarios and to evaluate performance in specific problem instances. Practical considerations include computational cost and robustness against various types of noise.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the stochastic bandit algorithms to handle more complex noise models beyond the sub-Gaussian assumption would enhance their practical applicability. Investigating the impact of different exploration-exploitation strategies within these algorithms is crucial for optimizing performance. On the theoretical front, closing the gap between the upper and lower bounds on the regret for stochastic settings remains an open problem and would improve understanding of algorithmic limits. Finally, given the NP-hardness result for the adversarial full-information setting, exploring approximation algorithms or alternative optimization techniques is vital to address the challenge of maximizing M-concave functions in adversarial scenarios. This could include developing methods that are robust to certain types of adversarial perturbations or exploring alternative learning paradigms, such as online convex optimization, for mitigating the computational challenges posed by the problem’s inherent complexity.

More visual insights#

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a visual illustration of how the feasible region Yk changes across different scenarios in the context of Algorithm 1. It depicts three scenarios: (1) where ik=0 and Yk−1 shrinks to Yk; (2) and (3) where ik≠0 and Yk shifts along ei₁. The table helps illustrate the concepts used in proving the robustness of Algorithm 1, specifically, showing the feasible points reachable from xk.

read the caption

Table 1: Images of Yk on Z2. The set of integer points in the trapezoid is the feasible region X. Left: the gray area represents Yk−1 consisting of points reachable from Xk−1. Middle: if ik = 0 (case 1), Xk−1 = Xk holds and Yk−1 shrinks to Yk, the darker area, since the constraint on y(V) gets tighter. Right: if ik = i₁ (cases 2 and 3), the area, Yk, reachable from Xk = Xk−1 + ei₁ shifts along ei₁.

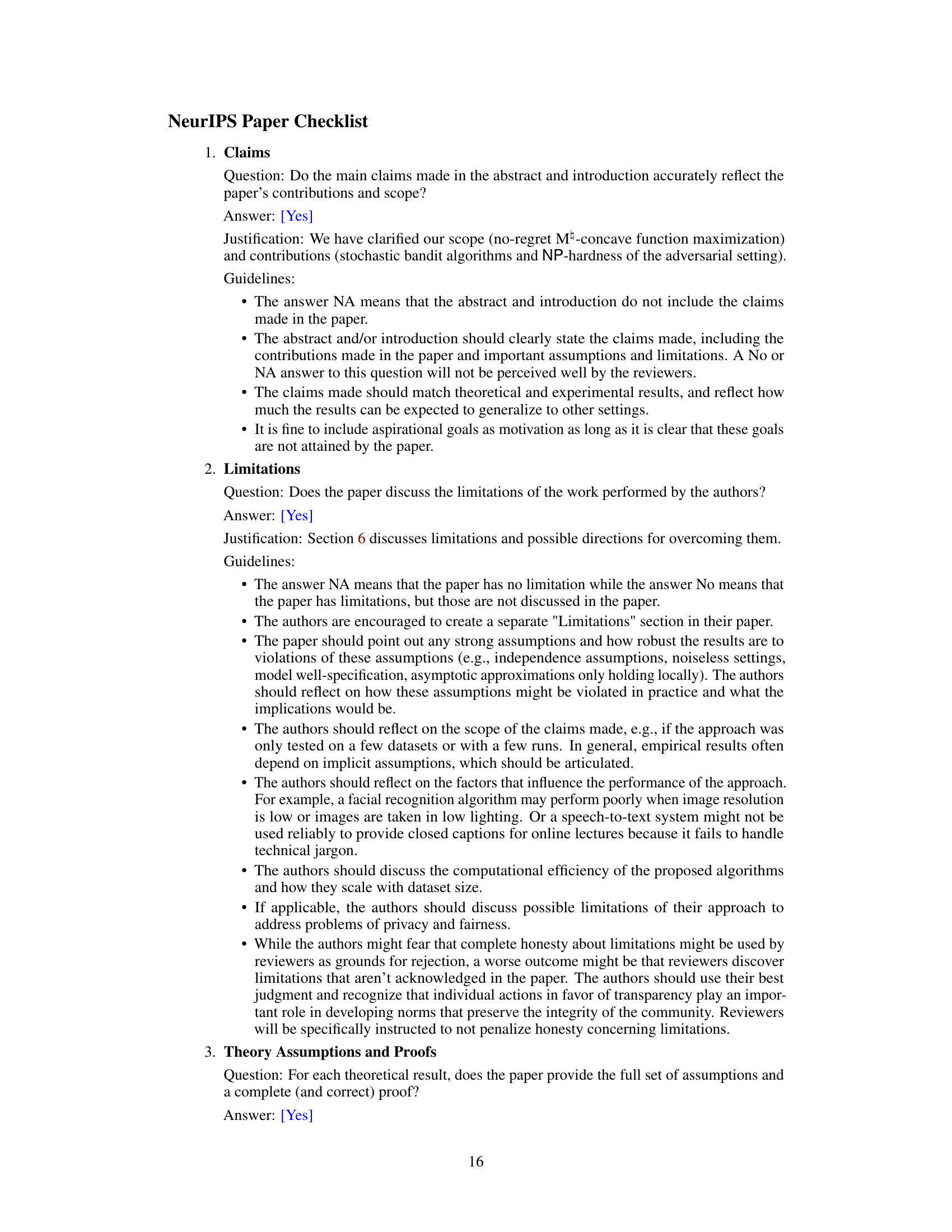

🔼 This table compares Theorem 3.1, which is about the robustness of greedy M-concave function maximization to local errors, with similar robustness results from the submodular case. It highlights key differences in the approaches and guarantees. The comparison focuses on the comparator used in the guarantees (optimal vs. approximate value), and the method of proof (analysis of solution space in M-concave case vs. direct analysis of objective values in submodular case).

read the caption

Table 1: Differences of Theorem 3.1 from robustness results in the submodular case

Full paper#