↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning tasks involve choosing between two states based on statistical evidence. This is often formulated as a constrained optimization problem, which can be challenging to solve. Existing approaches often tackle these problems individually, leading to fragmented solutions and a lack of unified understanding.

This research introduces a general framework for addressing such binary statistical decision-making problems. It offers a robust mathematical tool to derive optimal strategies for a wide array of problems, from well-established ones like the Neyman-Pearson problem to newer challenges such as selective classification in the presence of out-of-distribution data. The paper shows how this framework can easily derive known optimal solutions, underscoring its versatility and potential for future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on binary statistical decision-making (BDM) problems. It provides a unified mathematical framework that simplifies the process of solving various BDM problems, leading to more efficient and effective solutions. This framework is particularly useful in machine learning for tasks such as out-of-distribution (OOD) sample detection, selective classification, and other applications where optimal decision strategies are critical. The paper’s results offer a robust tool for addressing both existing and new BDM formulations, thus opening avenues for further research in this important area.

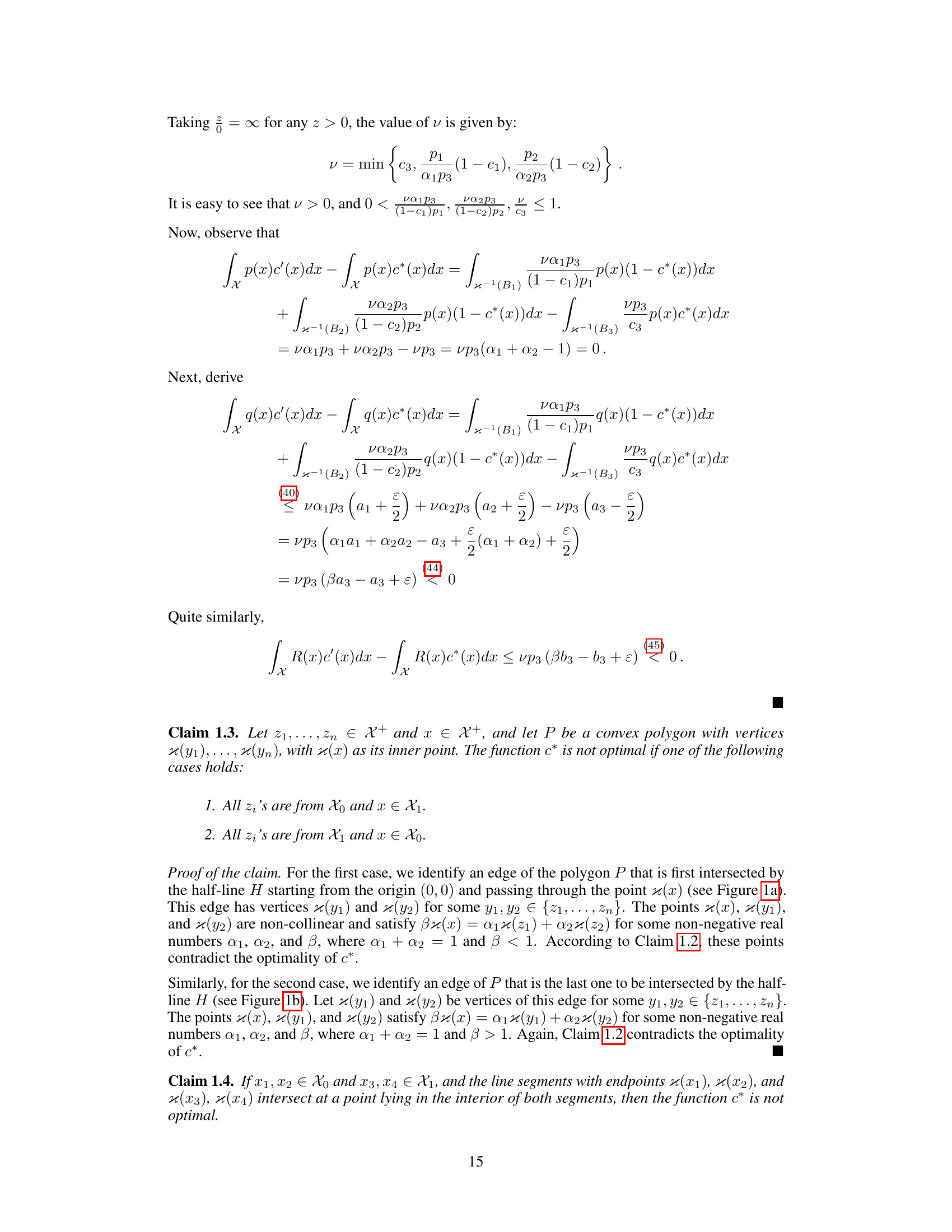

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates two scenarios showing infeasible configurations based on Claim 1.3 from the paper. Each scenario depicts a convex polygon in a two-dimensional space where the coordinates represent the ratios of functions R(x), p(x), and q(x). The points within the polygon represent elements from the sets X0, X1, and X2 (defined in the paper). The dashed lines highlight a separation based on the optimality of the decision strategy (c*) being analyzed. Scenario (a) shows an example where all vertices of the polygon are in X0 and the point x is in X1. Scenario (b) demonstrates a mirrored situation where the polygon’s vertices are in X1 and x is in X0. In both cases, these configurations violate the conditions of optimality for the strategy c*, as described in the paper’s Claim 1.3. The figure visually demonstrates a crucial part of the proof of the main theorem.

In-depth insights#

Optimal BDM Strategy#

The concept of an ‘Optimal BDM Strategy’ within the context of binary statistical decision-making (BDM) centers on identifying the best decision rule to minimize risk or maximize reward when choosing between two alternatives based on statistical evidence. This involves a constrained optimization problem, often formulated using Lebesgue integrals. Finding the optimal strategy often simplifies to approximating a specific likelihood ratio (comparing in-distribution vs out-of-distribution probabilities) and then determining an optimal threshold. The optimal strategy’s structure significantly reduces the complexity of solving the core problem. A robust mathematical framework provides a general solution applicable to diverse BDM scenarios like Neyman-Pearson detection or selective classification. The research emphasizes the importance of analyzing the optimal strategy’s structure to overcome challenges faced in learning robust and efficient detectors for various applications, leading to more precise and accurate classification and decision-making results.

SCOD Problem Variants#

The study delves into variations of the Selective Classification with Out-of-Distribution data (SCOD) problem, highlighting the importance of understanding the structure of optimal strategies in solving these problems. It explores how a generic BDM framework simplifies the analysis and derivation of solutions for various BDM problems. The paper then uses the framework to formulate and solve two novel SCOD variants. These variants address limitations of the original SCOD formulation, like the assumption that the prediction loss and OOD cost share the same units. The new formulations introduce a hard constraint on FPR instead of using a relative cost, and the use of precision instead of FPR, both offering practical advantages. By providing optimal solutions for these variations, the study underscores the power of a generic BDM approach in tackling complex machine learning problems.

Generic BDM Solution#

A generic BDM (Binary Decision Making) solution aims to provide a unified framework for solving a wide range of BDM problems. This approach is valuable because it avoids the need for problem-specific solutions, offering a more efficient and streamlined process. The core idea is to characterize the optimal decision strategies through a constrained optimization problem. This often involves expressing the objective and constraints using Lebesgue measurable functions, which allows for the inclusion of both continuous and discrete instance spaces. The solution often involves a crucial score function derived from the problem parameters. This function then determines the optimal decision strategy. The simplicity and generality of such a framework are significant advantages, allowing for easier derivation of optimal strategies for new or existing BDM instances. However, it’s important to note that determining the score function and other crucial parameters might still require careful consideration and possibly tuning. Therefore, while a generic solution offers significant simplification, a deep understanding of the underlying mathematical framework is still crucial for effective implementation.

BDM Applications#

Binary statistical decision-making (BDM) has a wide array of applications, particularly within machine learning. One key application is anomaly detection, where BDM helps distinguish between in-distribution and out-of-distribution data points. Another major application is in selective classification, aiming to improve the overall performance by abstaining from predictions on uncertain samples. This is particularly relevant in scenarios with high-stakes decisions where confident predictions are crucial. BDM also plays a significant role in the design of optimal detectors, where the goal is to maximize the probability of correct classification while controlling the rate of false positives or negatives. The optimal strategies derived from BDM can improve various aspects of machine learning models, leading to more robust and reliable systems. Finally, the flexible framework of BDM allows for adaptation to diverse scenarios and problem formulations, making it a powerful tool for addressing a broad range of machine learning challenges.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass more complex scenarios with multiple constraints or more intricate objective functions would enhance its applicability to a wider range of real-world problems. Investigating the computational efficiency of the proposed algorithms and developing more scalable methods are crucial. Exploring the practical implications of the findings in specific machine learning domains, such as selective classification and out-of-distribution detection, could yield significant improvements. A key area for future exploration involves developing robust methods for approximating the likelihood ratios and conditional risk functions, which are central components of the proposed optimal strategies. Finally, empirical validation on various datasets across diverse machine learning problems is necessary to assess the practical effectiveness of this generalized approach and further refine its application in real-world settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

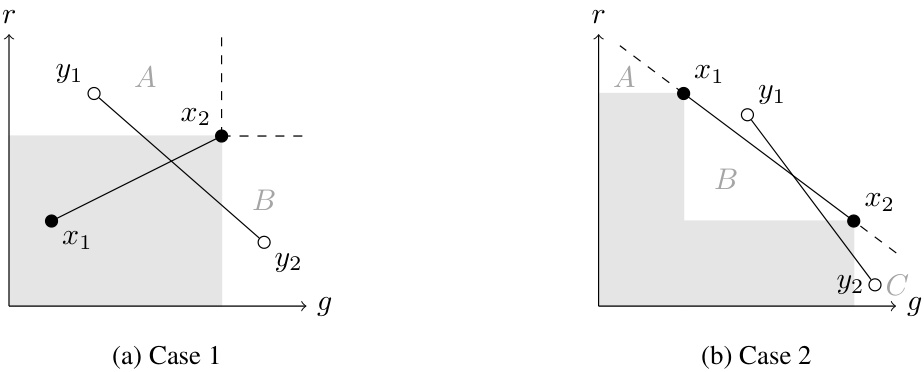

This figure illustrates two scenarios that contradict the optimality conditions derived in Claim 1.3 of the paper. In both cases, the placement of points in relation to the polygon and line segments demonstrates infeasible configurations, meaning these point arrangements cannot exist in an optimal solution to the problem presented.

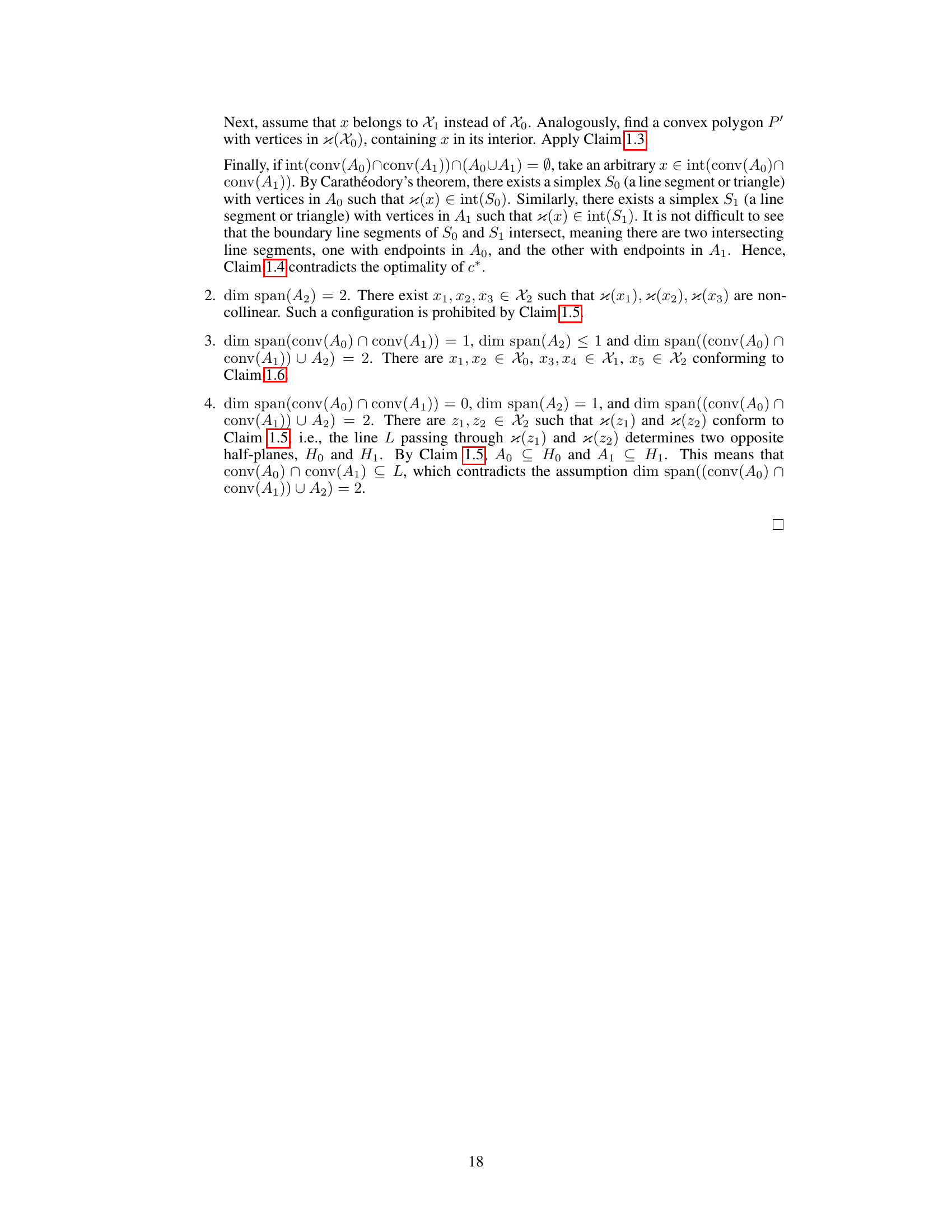

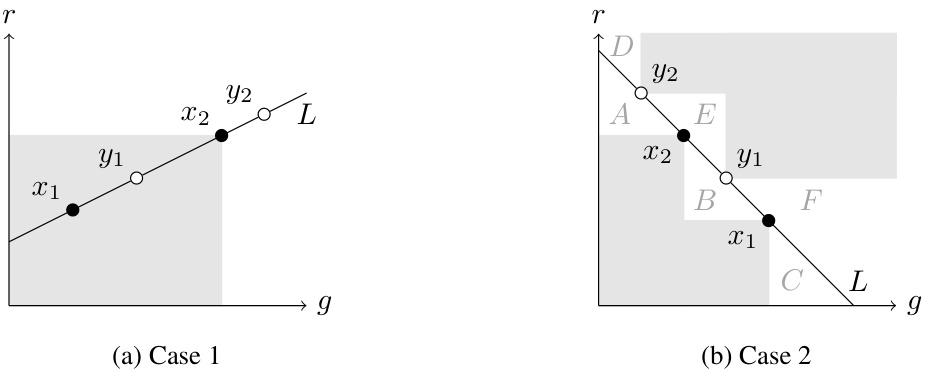

This figure illustrates two scenarios that contradict the optimality of the solution c in Claim 1.5. In both cases, the points κ(z1) and κ(z2) are distinct points from the set X2. The line L passes through these points and determines two open half-planes, H0 and H1. If the slope of L is positive (Case 1), it violates Claim 1.1. If the slope of L is not positive (Case 2), it violates Claim 1.1 because the open half-plane H0 does not contain any points from A0 U A2, and similarly, the opposite open half-plane H1 does not contain any points from A1 U A2.

This figure illustrates two scenarios showing infeasible configurations as described in Claim 1.3 of the Appendix. In both cases, the arrangement of points in the g-r plane (representing the functions g(x) and r(x)) contradicts the optimality conditions derived in the paper. The specific arrangement of points from sets X₀, X₁, and X₂ in the g-r plane leads to a contradiction of the optimality of the proposed solution.

Full paper#