TL;DR#

Generating and manipulating 3D deformable objects with diverse poses and identities remains challenging due to the need for large-scale datasets. Current methods often struggle to disentangle pose information from object identity or require explicit shape parameterization and correspondence supervision. This limits the ability to transfer poses between different objects and generate novel poses effectively.

This paper proposes a novel method to address these limitations by learning a disentangled pose representation using a keypoint-based hybrid approach and an implicit deformation field. The method does not need explicit shape parameterization, point-level or shape-level correspondence supervision, or variations of the target object. Experiments demonstrate state-of-the-art performance in pose transfer and diverse shape generation with various objects and poses, showing significant improvements over existing techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with 3D deformable objects because it introduces a novel method for learning pose representations that disentangles pose information from object identity, enabling diverse pose generation and transfer across different objects. This significantly reduces the reliance on large-scale datasets, opening new avenues for research in areas like character animation and 3D shape modeling. The proposed method’s efficiency and generalization capabilities advance the state-of-the-art and encourage further investigation into implicit pose representations and generative models for 3D shapes.

Visual Insights#

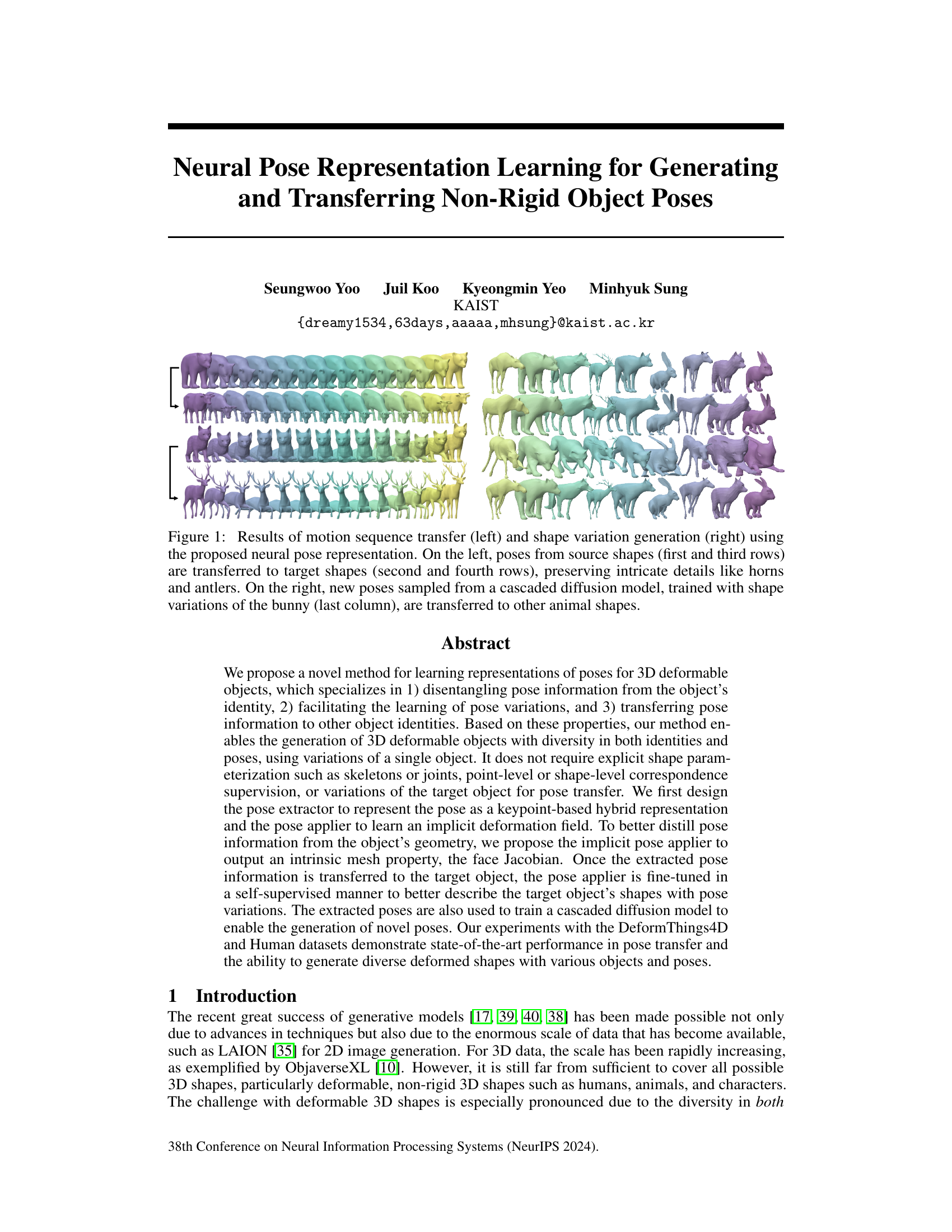

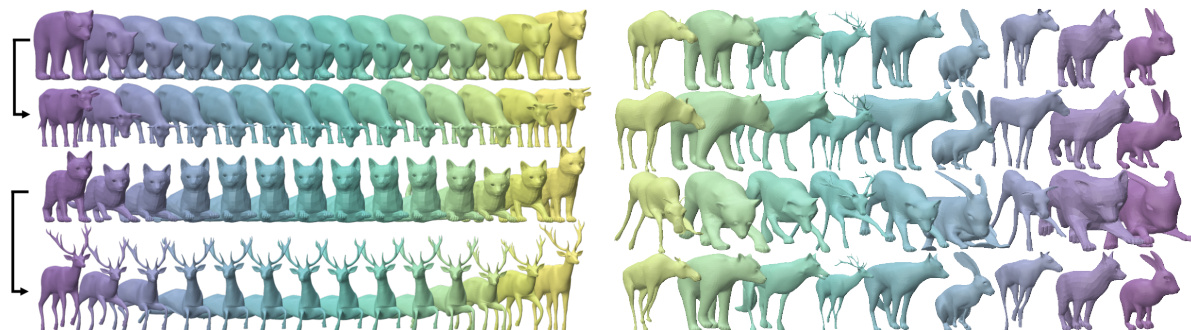

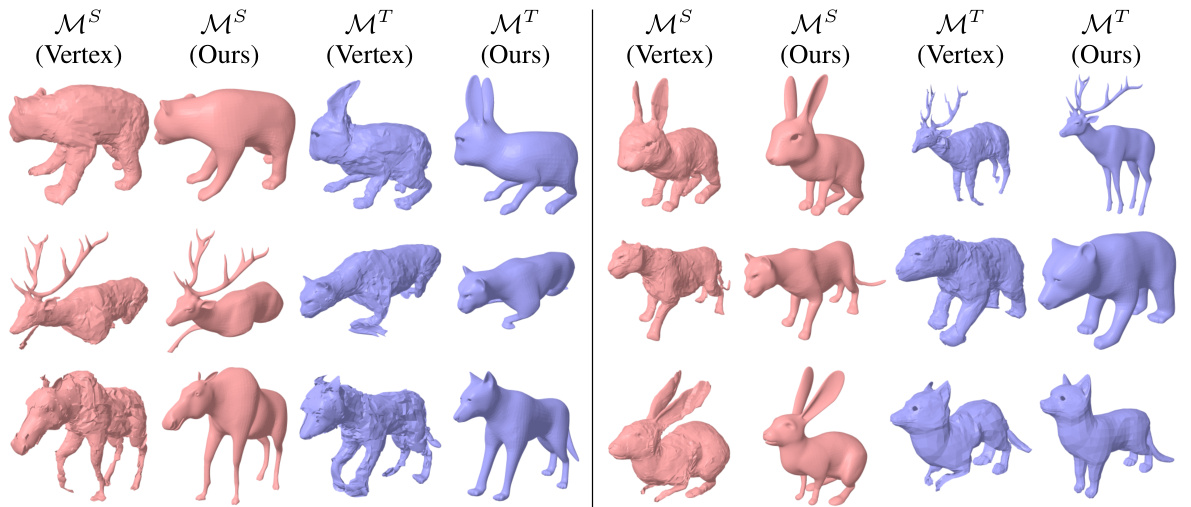

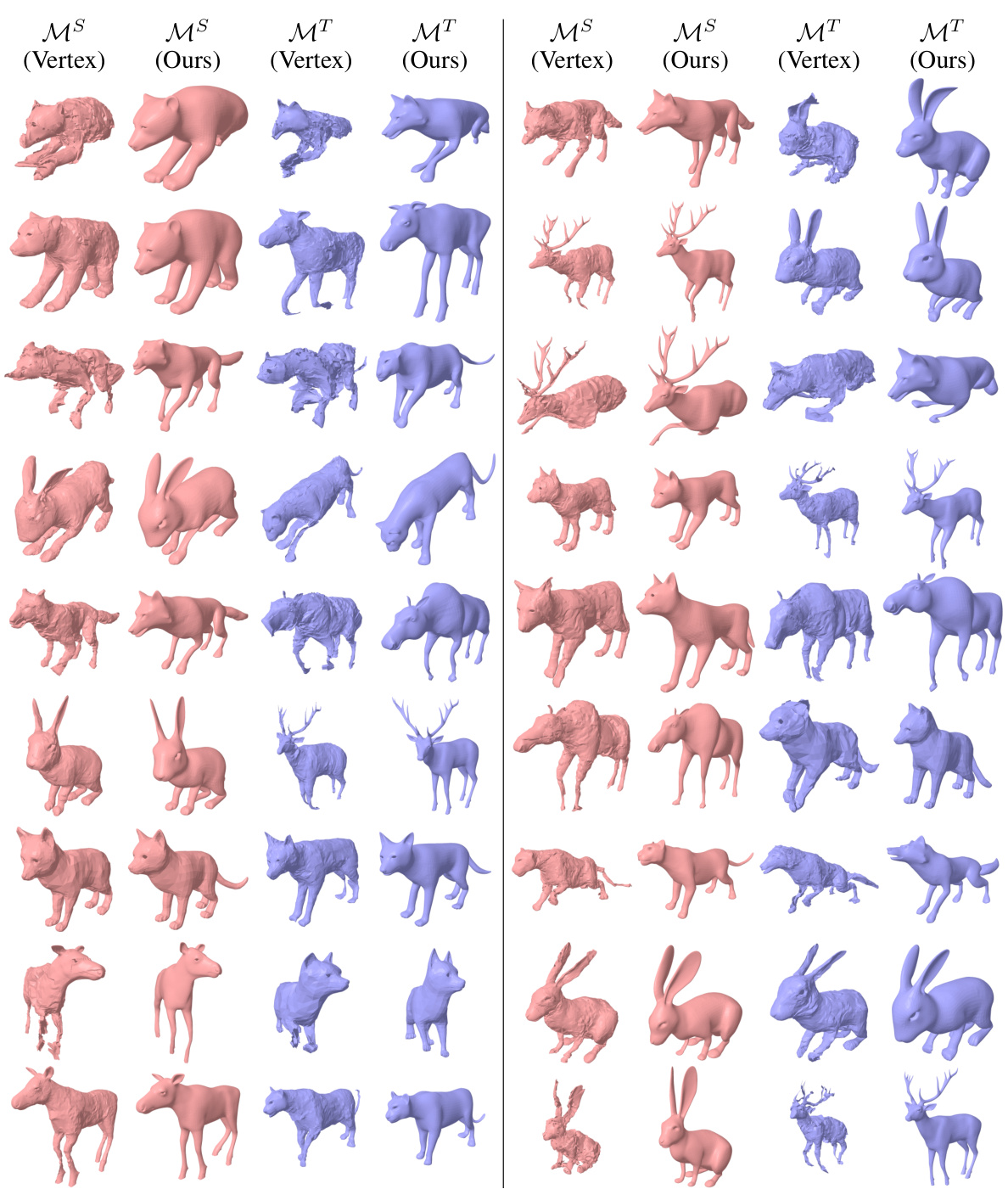

🔼 This figure demonstrates the results of the proposed method for transferring poses and generating shape variations. The left side shows pose transfer where poses from source animal shapes are successfully transferred to different target animal shapes, maintaining detailed features such as horns and antlers. The right side illustrates the shape variation generation where new poses are sampled from a diffusion model trained on a single bunny and applied to various other animals. This showcases the method’s ability to disentangle pose from identity and transfer pose information between different animal shapes.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of motion sequence transfer (left) and shape variation generation (right) using the proposed neural pose representation. On the left, poses from source shapes (first and third rows) are transferred to target shapes (second and fourth rows), preserving intricate details like horns and antlers. On the right, new poses sampled from a cascaded diffusion model, trained with shape variations of the bunny (last column), are transferred to other animal shapes.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against three baselines (NJF [2], SPT [24], and ZPT [48]) on two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL human shapes. For the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset, the metrics used are FID, KID, and ResNet accuracy. For the SMPL dataset, PMD (Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance), FID, KID, and ResNet accuracy are reported. Lower values for FID, KID, and PMD indicate better performance, while a higher ResNet accuracy indicates better performance. The results show that the proposed method outperforms the baselines in terms of pose transfer accuracy across both datasets.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

In-depth insights#

Pose Disentanglement#

Pose disentanglement, in the context of 3D deformable object pose representation learning, presents a significant challenge. The core idea is to separate pose information from the object’s identity. This disentanglement is crucial for enabling pose transfer between different objects, as it allows for the manipulation of pose without altering the underlying object shape or characteristics. A successful disentanglement method should generate pose representations that are object-agnostic, meaning they can be applied to different objects to produce diverse poses while preserving the identity of the target object. The difficulty arises from the complex interdependencies between pose and shape, which necessitates sophisticated methods like autoencoders or diffusion models to effectively learn and represent this distinct information. Keypoint-based methods have shown potential for achieving compact and transferable pose representations, but the challenge remains to create a representation that is both robust to variations in shape and identity, and generalizes effectively across diverse object categories.

Hybrid Pose Encoding#

A hybrid pose encoding method represents poses using a combination of techniques, likely merging the strengths of different approaches for a more robust and comprehensive representation. Keypoint-based methods offer a compact and easily transferable representation, capturing pose information efficiently, even for complex shapes. However, they might lack the detailed geometric information needed for accurate deformation. Implicit deformation fields provide detailed geometry information and handle complex deformations well, but they can be computationally expensive and less transferable. A hybrid approach might use keypoints to broadly define pose and then use deformation fields to refine the pose’s details, capturing both compactness and precision. This strategy could disentangle pose information from object identity, a critical aspect of pose transfer to novel objects. The hybrid approach is likely trained in an autoencoding fashion to learn a latent representation of the pose, enabling compact storage and generative modeling. This holistic encoding method enables better pose transferability and generation, significantly improving the performance compared to using either technique alone.

Diffusion Model for Pose#

A diffusion model for pose estimation in 3D shapes presents a powerful approach to disentangle pose from object identity. The core idea is to learn a latent representation of pose variations from a limited set of source object poses, making it transferable to novel objects. The model’s compactness is key, allowing for efficient training and generation of novel poses, overcoming limitations of data-hungry methods. This is achieved by using techniques that extract pose-specific information like Jacobian fields or keypoint-based hybrid representations, ensuring identity-agnostic pose encoding. A cascaded training approach often proves effective, allowing the model to capture complex pose relationships. The ability to generate new poses further enhances the model’s applicability, as it does not require exhaustive pose variations for each object. However, challenges remain in handling complex non-rigid deformations, especially for shapes with intricate geometries. Robustness to noise and outliers in the training data, as well as generalization across vastly different object morphologies, remain ongoing research avenues. Overall, diffusion models represent a promising area for advancing pose transfer and generation, especially when data is scarce.

Transferability Across Shapes#

The concept of “Transferability Across Shapes” in a 3D object pose research paper is crucial. It speaks to the ability of a learned pose representation to generalize beyond the specific shapes used during training. High transferability implies that a pose learned from one object can be successfully applied to another, significantly reducing the need for large, diverse datasets. This is a major advantage, especially when dealing with deformable objects. Effective transferability hinges on disentangling pose information from object identity. If the pose representation is entangled with shape specifics, it will fail to generalize. Therefore, a successful approach likely uses a hybrid representation that separates pose information from shape features. A keypoint-based hybrid representation is one possible solution, where keypoints capture pose and latent features disentangle identity, making the representation compact and transferable. The quality of pose transfer is then evaluated by metrics that capture the geometric fidelity of the transferred pose on various target shapes, assessing how well the intended pose is transferred without distorting the underlying shape identity.

Limitations and Future#

The research paper’s limitations section should thoroughly address any shortcomings or constraints impacting the study’s generalizability and reliability. A key limitation could involve the datasets used: were they sufficiently large and diverse to represent the complexity of real-world non-rigid object poses? The methodology’s robustness to unseen data should be critically assessed, exploring the extent of its generalizability across different object categories and pose variations. The reliance on specific models (e.g., diffusion models) for pose generation warrants attention; are the results solely dependent on these model’s limitations, or is there inherent value to the approach independent of these choices? The evaluation metrics employed should be critically examined for their suitability in assessing pose transfer and generation fidelity. A discussion of the computational costs and scalability of the proposed method is essential, considering its implications for wider adoption. Future work could focus on addressing these limitations through improved dataset diversity, exploring alternative generative models or incorporating robustness techniques, developing more nuanced evaluation metrics, and investigating more efficient computation methods. Furthermore, a discussion of the broader ethical implications of this research, especially concerning the potential misuse of the technology (e.g., deepfakes), is necessary.

More visual insights#

More on figures

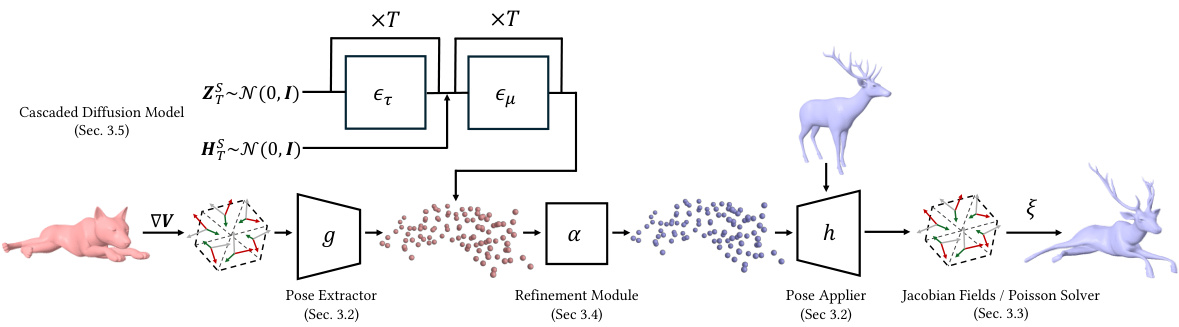

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed method for learning pose representations of 3D deformable objects. It shows how the pose extractor (g) processes the Jacobian fields to extract a keypoint-based hybrid pose representation. This representation is then refined by a refinement module (α) before being applied to the target object by the pose applier (h), which outputs a deformed mesh based on Jacobian fields. The latent pose representations are also used to train a cascaded diffusion model, enabling the generation of diverse poses.

read the caption

Figure 2: Method overview. Our framework extracts keypoint-based hybrid pose representations from Jacobian fields. These fields are mapped by the pose extractor g and mapped back by the pose applier h. The pose applier, conditioned on the extracted pose, acts as an implicit deformation field for various shapes, including those unseen during training. A refinement module α, positioned between g and h, is trained in a self-supervised manner, leveraging the target's template shape. The compactness of our latent representations facilitates the training of a diffusion model, enabling diverse pose variations through generative modeling in the latent space.

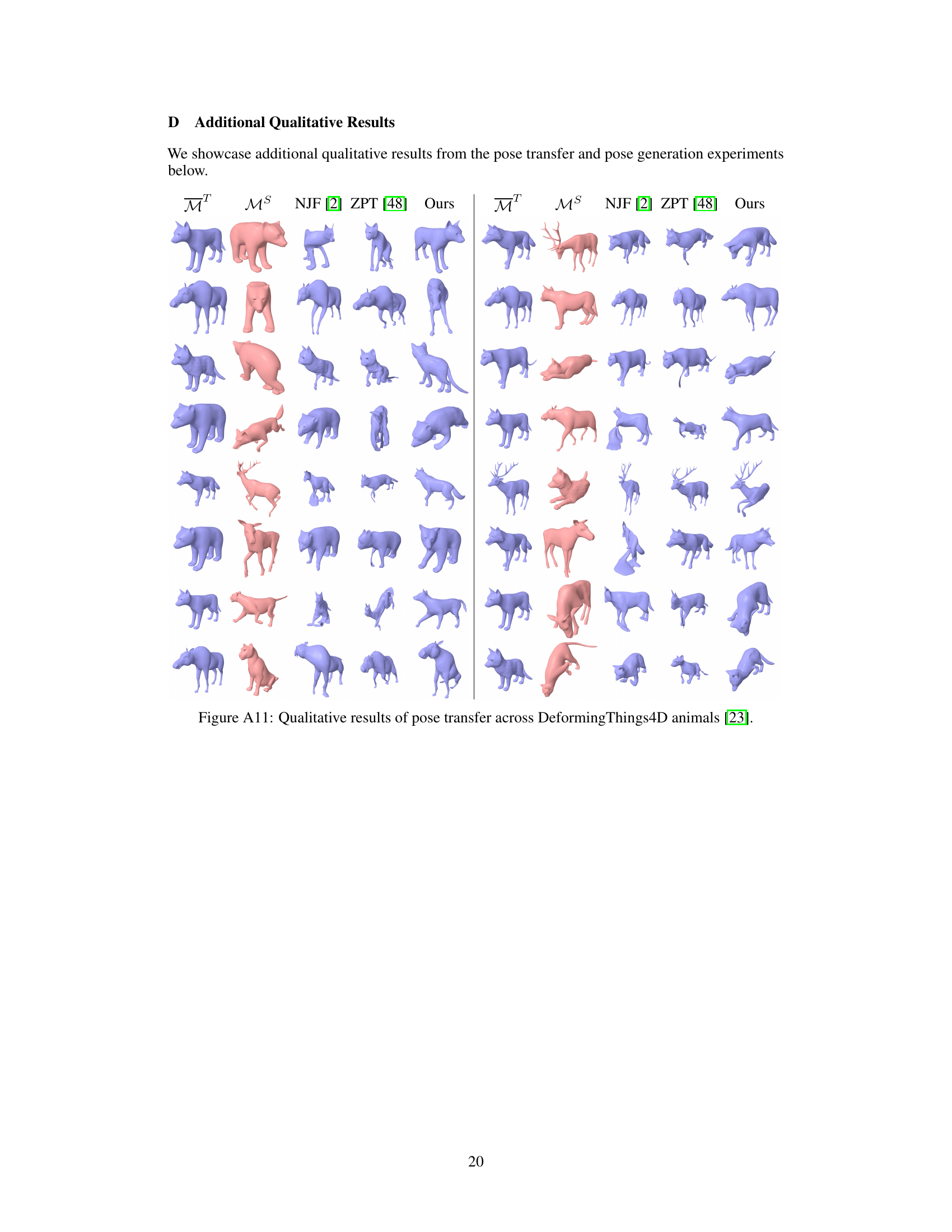

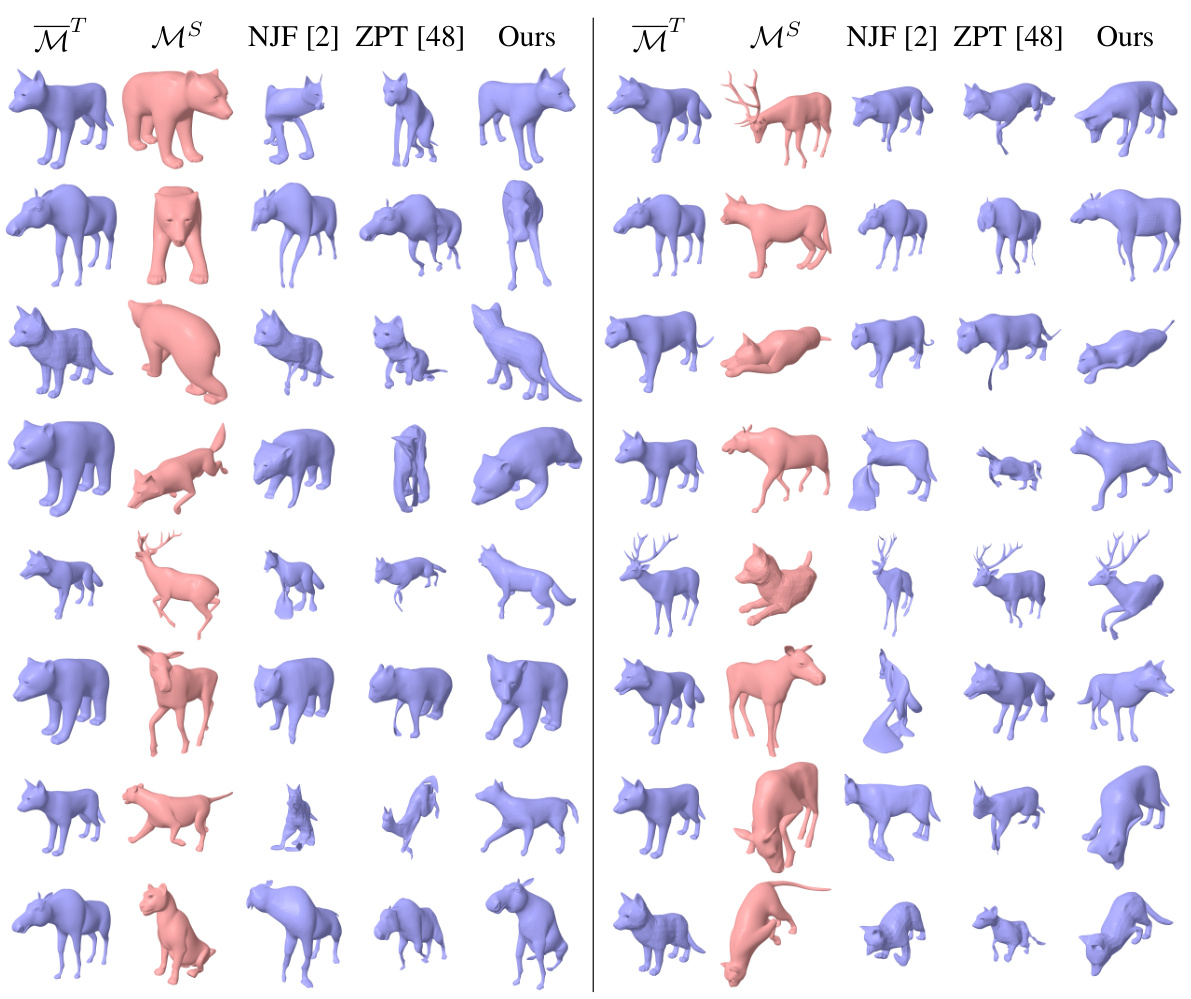

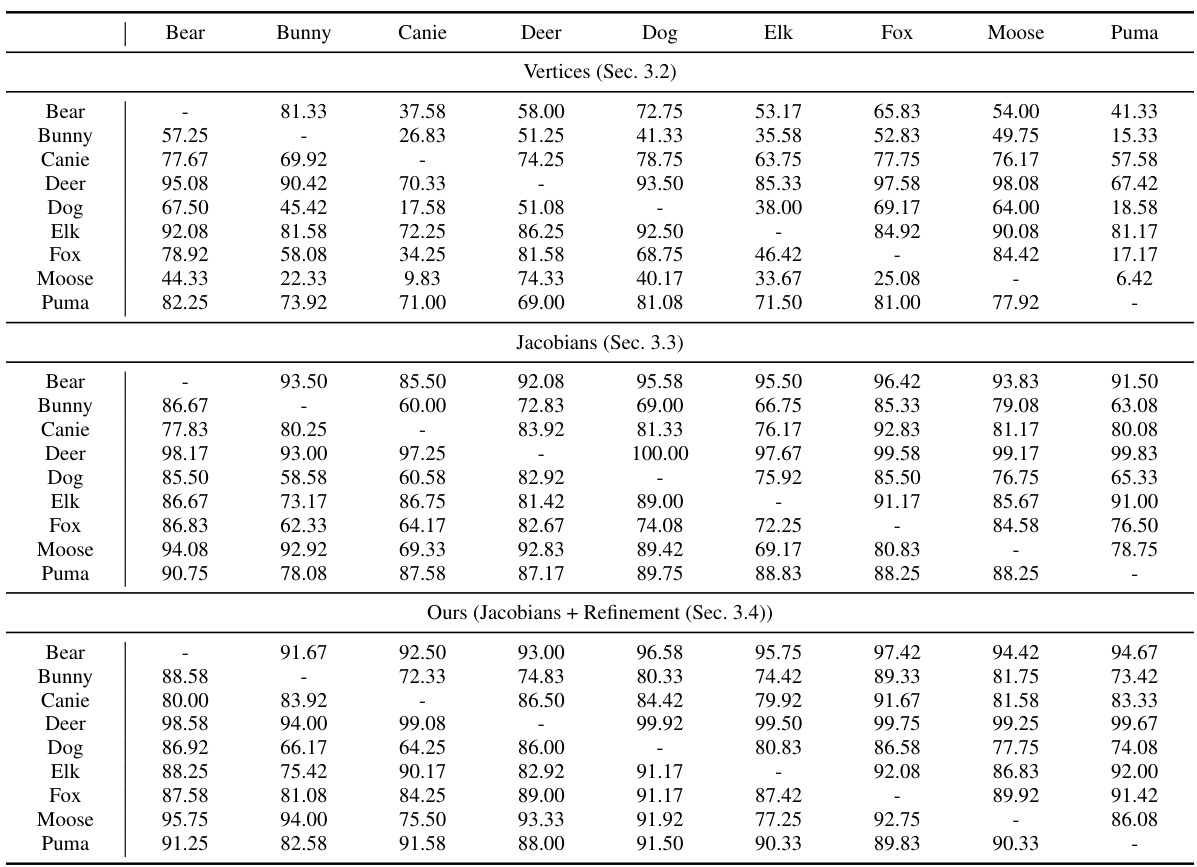

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of pose transfer results across different animal shapes using four different methods: NJF [2], ZPT [48], Ours (the proposed method), and a baseline approach. For each animal type, a source mesh (‘MS’) with a specific pose and a target template mesh (‘MT’) are shown. The results illustrate the capability of each method to transfer the pose from the source to the target while maintaining the target shape’s identity. The ‘Ours’ column showcases the proposed method’s ability to transfer poses effectively compared to the other methods.

read the caption

Figure A11: Qualitative results of pose transfer across DeformingThings4D animals [23].

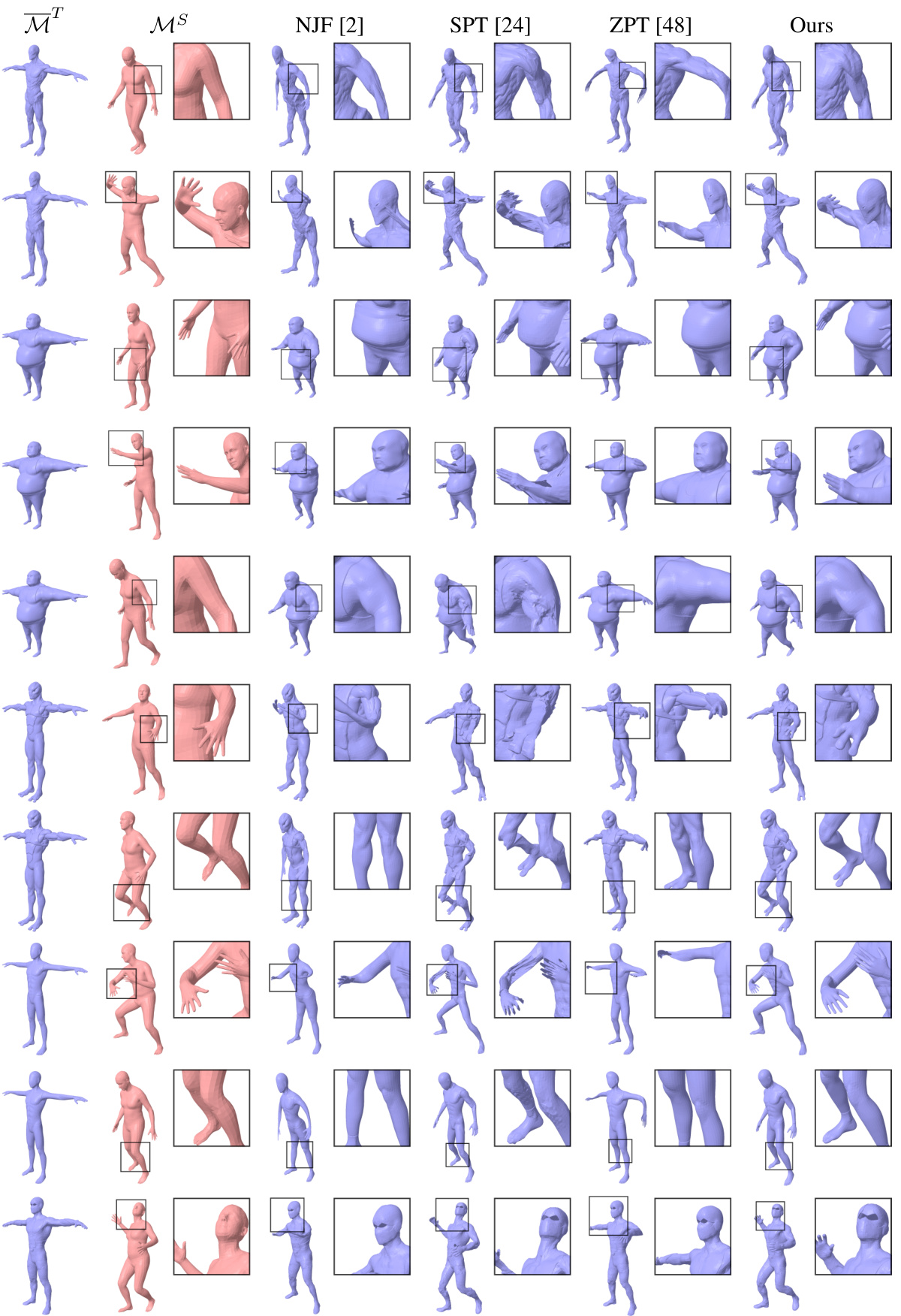

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of pose transfer results across different human body shapes from the SMPL dataset. It contrasts the performance of four different methods: NJF [2], SPT [24], ZPT [48], and the authors’ proposed method. The figure visually demonstrates how well each method transfers poses from a source mesh (MS) to various target meshes (MT), while also showing the ground truth target (MGT). The zoomed-in view is recommended for better appreciation of the details.

read the caption

Figure A13: Qualitative results of pose transfer across different SMPL [28] human body shapes. Best viewed when zoomed-in.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of pose transfer results from four different methods: NJF [2], SPT [24], ZPT [48], and the proposed method. The source meshes (red) are from the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23], and the target meshes (blue) are from the same dataset. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in accurately transferring poses while preserving local geometric details, in contrast to the other methods which show distortions.

read the caption

Figure 3: Qualitative results of transferring poses of the source meshes MS's (red) in the DeformingThings4D animals [23] to target templates M¹'s (blue). Best viewed when zoomed in.

🔼 This figure displays the results of an ablation study comparing different variations of the proposed method for pose transfer. The source shape (MS) is a deer, and the target template (MT) is a human-like shape. The different versions of the method are shown, highlighting the effect of using vertices only (a simplistic approach), Jacobian fields only (preserving surface geometry), and the complete method incorporating Jacobian fields and a refinement module. The goal is to demonstrate that the proposed complete method that uses Jacobian fields and a refinement module achieves better pose transfer than simpler alternatives.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative results from the ablation study where a pose of the source shape MS (red) in the DeformingThings4D-Animals [23] is transferred to the target template shape MT (blue).

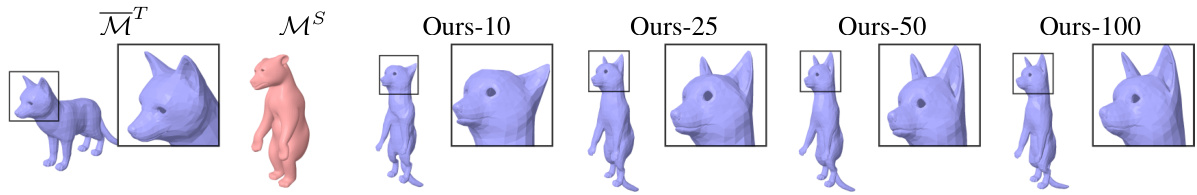

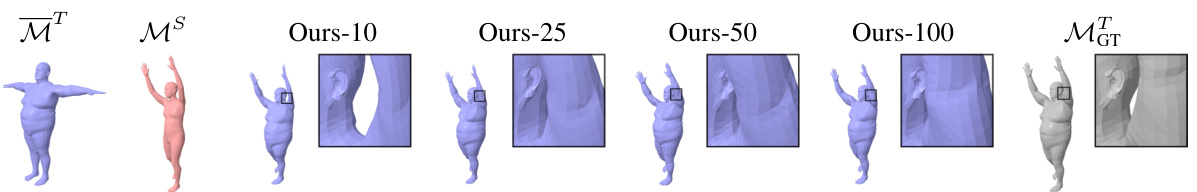

🔼 This figure shows the qualitative results of pose transfer experiments using different numbers of keypoints (10, 25, 50, and 100). The source mesh (red) and target template mesh (blue) are displayed, demonstrating how the pose is transferred with varying numbers of keypoints. It aims to show the impact of the number of keypoints on pose transfer quality, focusing on the visual differences in the transferred poses.

read the caption

Figure 7: Qualitative results of transferring a pose of the source shape MS (red) in the DeformingThings4D-Animals [23] to the target template shape MT (blue) using variants of our framework (Ours-N), trained to extract N keypoints.

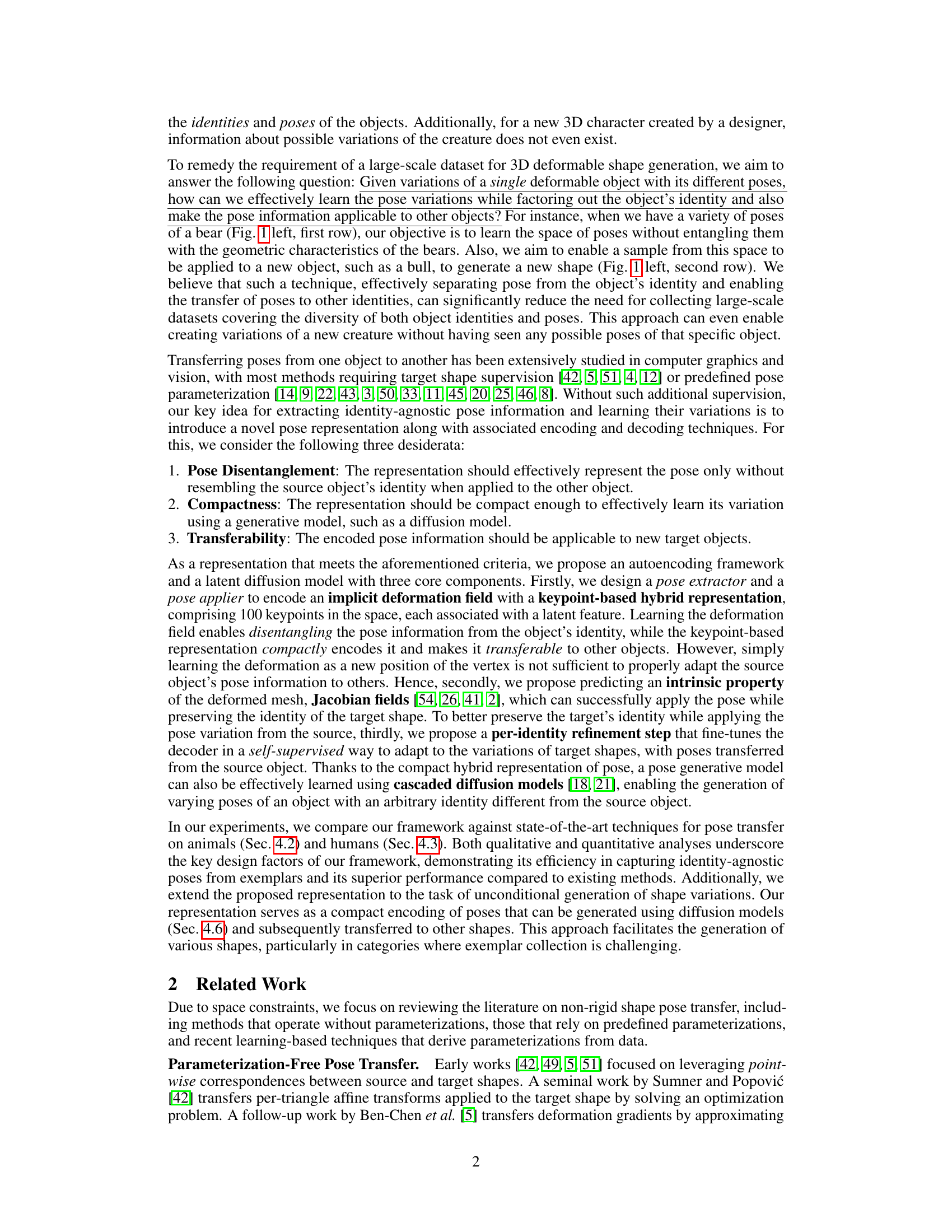

🔼 This figure displays the results of a pose transfer experiment using different numbers of keypoints extracted by the pose extractor. The source mesh (\mathcal{M}^S) (red) is a default human mesh. The target template mesh (\mathcal{M}^T) (blue) is also a human mesh, but with a different body shape. Four different variants of the method, trained with 10, 25, 50, and 100 keypoints, respectively, are shown. The ground truth target shape (\mathcal{M}^T_{GT}) is also shown in grey for comparison. This experiment aims to demonstrate the impact of the number of keypoints on the accuracy of pose transfer and the quality of the resulting shapes.

read the caption

Figure 8: Qualitative results of transferring a pose of the default human mesh \(\mathcal{M}^S\) (red) to the target template mesh \(\mathcal{M}^T\) (blue) using variants of our framework (Ours-N), trained to extract N keypoints.

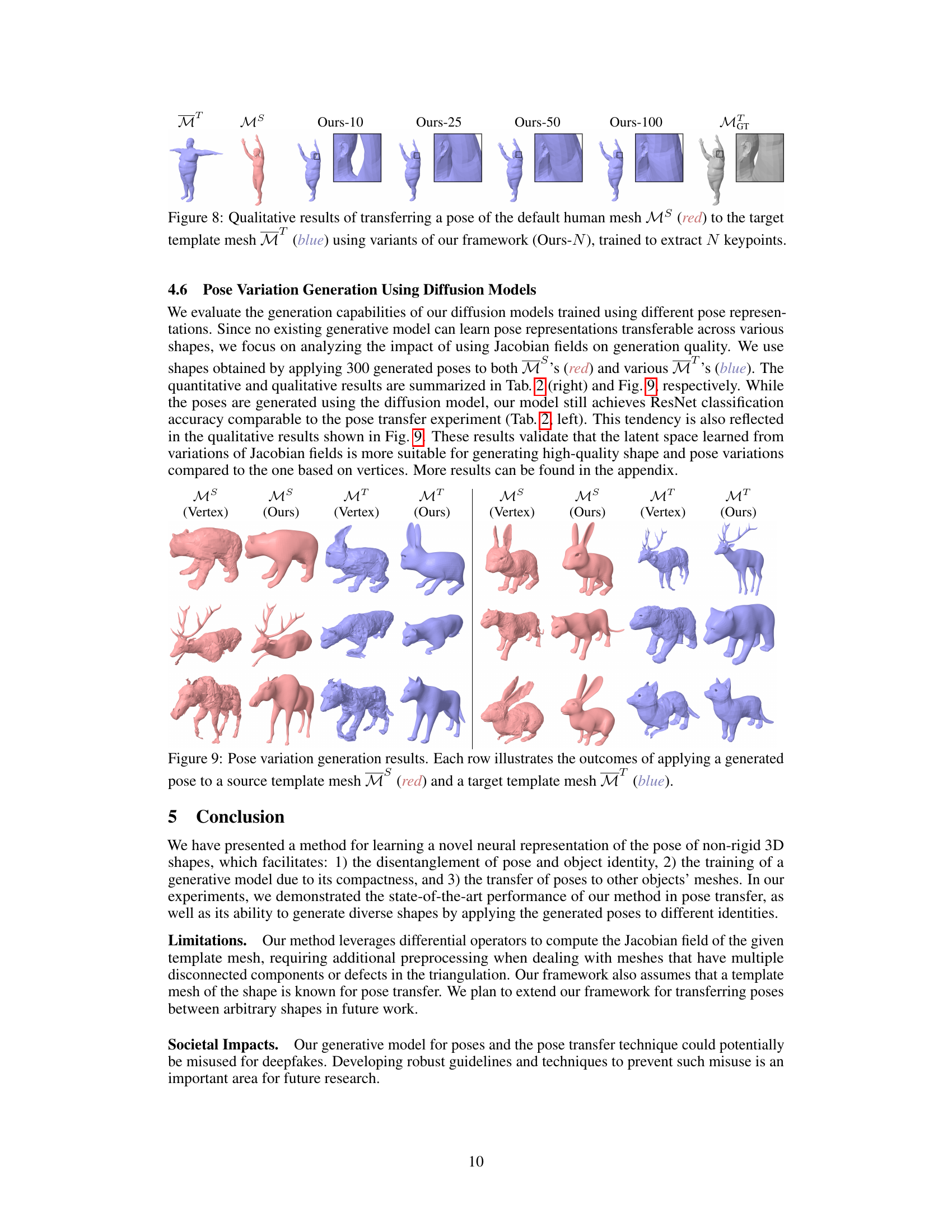

🔼 This figure shows the results of unconditional pose generation. For each row, a pose was generated and applied to the source shape (red), and then that same pose was transferred to various target shapes (blue). This demonstrates the ability of the method to generate novel poses and transfer them to different objects.

read the caption

Figure A14: Unconditional generation results. Each row illustrates the outcome of directly applying the generated poses to the source shape and then transferring them to various target shapes .

🔼 This figure shows the results of pose transfer from a source mesh to a target mesh from four different viewpoints. It supplements Figure 5 in the main paper by providing additional perspectives on the quality of the pose transfer. The viewpoints help to illustrate the 3D nature of the generated shape and confirm that the pose transfer is successful from multiple angles.

read the caption

Figure A10: A pose transfer example showcases in Fig. 5, rendered from 4 different viewpoints.

🔼 This figure shows qualitative results of pose transfer experiments on animal shapes from the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset. For each animal type, it shows the source shape (MS, in red), the target shape (MT, in blue), and the results of pose transfer using three different methods: NJF [2], ZPT [48], and the authors’ proposed method. The comparison demonstrates that the authors’ approach achieves more realistic and accurate pose transfer compared to the other methods.

read the caption

Figure A11: Qualitative results of pose transfer across DeformingThings4D animals [23].

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of pose transfer results from a SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear Model) mesh to Mixamo characters. The results from four different methods (NJF [2], SPT [24], ZPT [48], and the proposed method ‘Ours’) are displayed side-by-side, allowing for a visual comparison of pose accuracy and geometric fidelity. Each row represents a different source pose and target character, illustrating the methods’ ability to transfer the pose while maintaining the character’s identity. The caption suggests zooming in for better detail.

read the caption

Figure A12: Qualitative results of pose transfer from a SMPL [28] mesh to Mixamo characters [1]. Best viewed when zoomed in.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of pose transfer results across different SMPL human body shapes using four different methods: NJF [2], SPT [24], ZPT [48], and the authors’ proposed method. The results are presented for several different poses. The goal is to evaluate how well each method transfers the pose from a source mesh (MS) to various target meshes (MT) which represent different body shapes. The ground truth is also shown in the figure (MGT). The zoomed-in view is recommended for better visibility of the results.

read the caption

Figure A13: Qualitative results of pose transfer across different SMPL [28] human body shapes. Best viewed when zoomed-in.

🔼 This figure shows the results of unconditional pose generation. Poses are generated using a diffusion model and directly applied to a source shape. Then, these poses are transferred to different target shapes to illustrate the ability of the model to generate diverse poses that transfer well across different objects. The results demonstrate successful pose transfer, maintaining the identity of the target shape while applying the generated pose.

read the caption

Figure A14: Unconditional generation results. Each row illustrates the outcome of directly applying the generated poses to the source shape and then transferring them to various target shapes .

More on tables

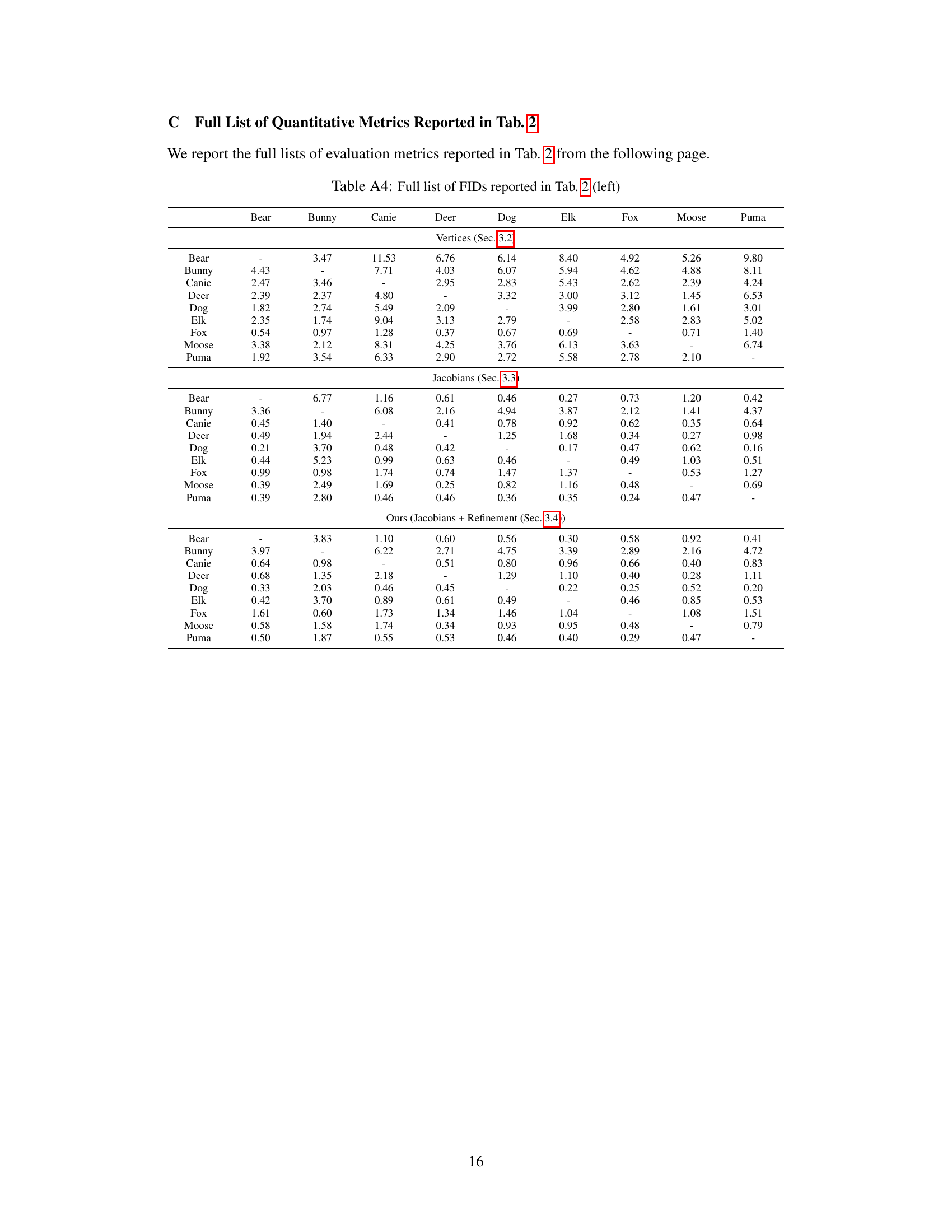

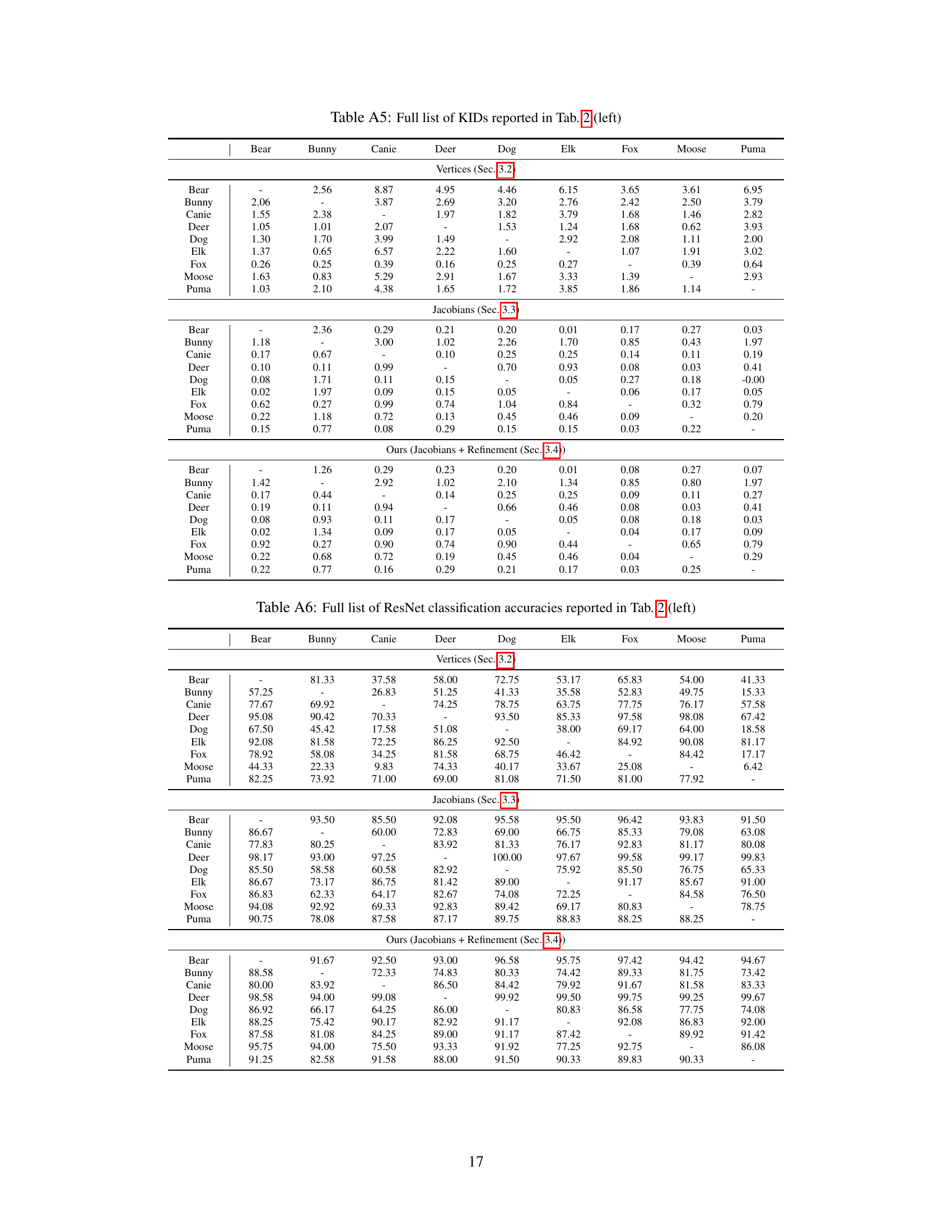

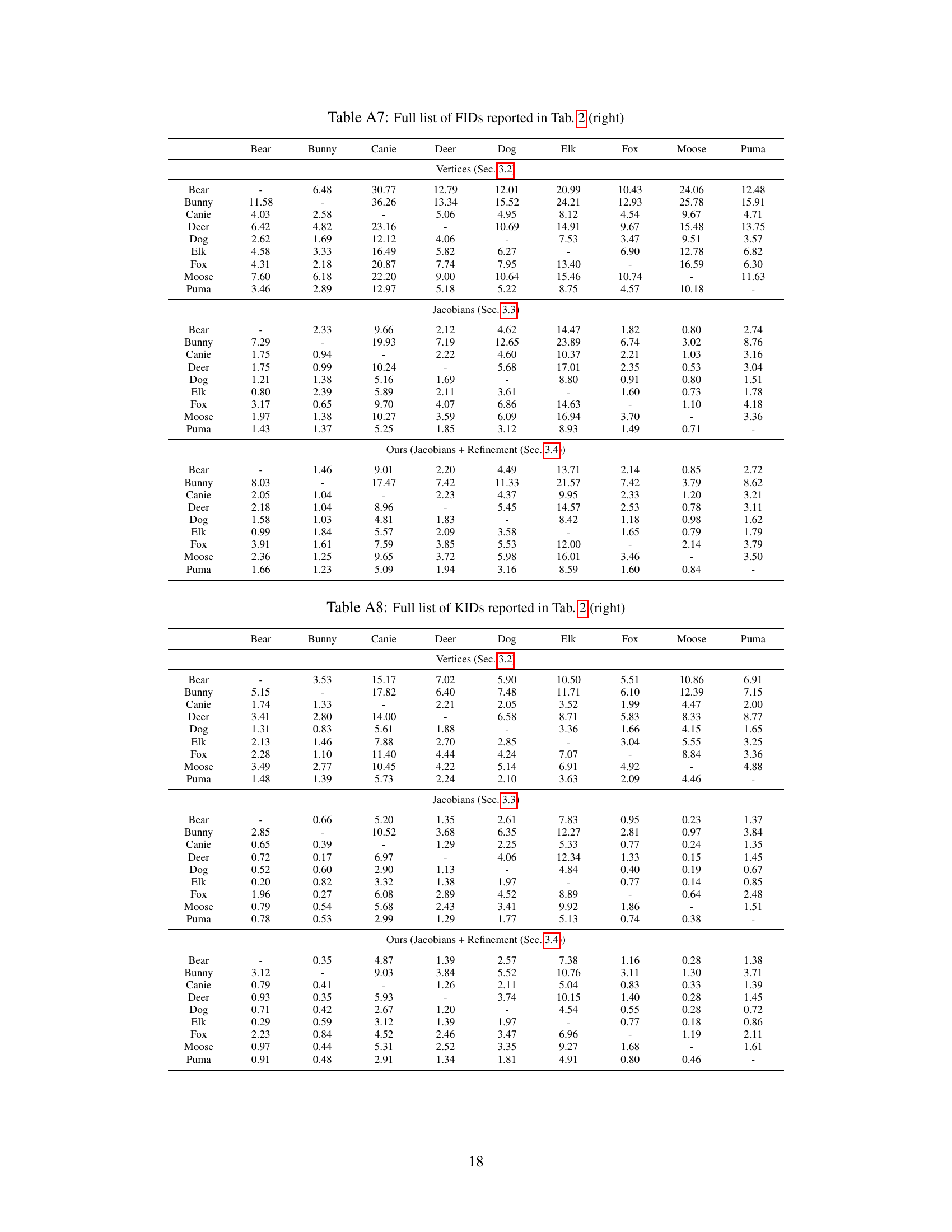

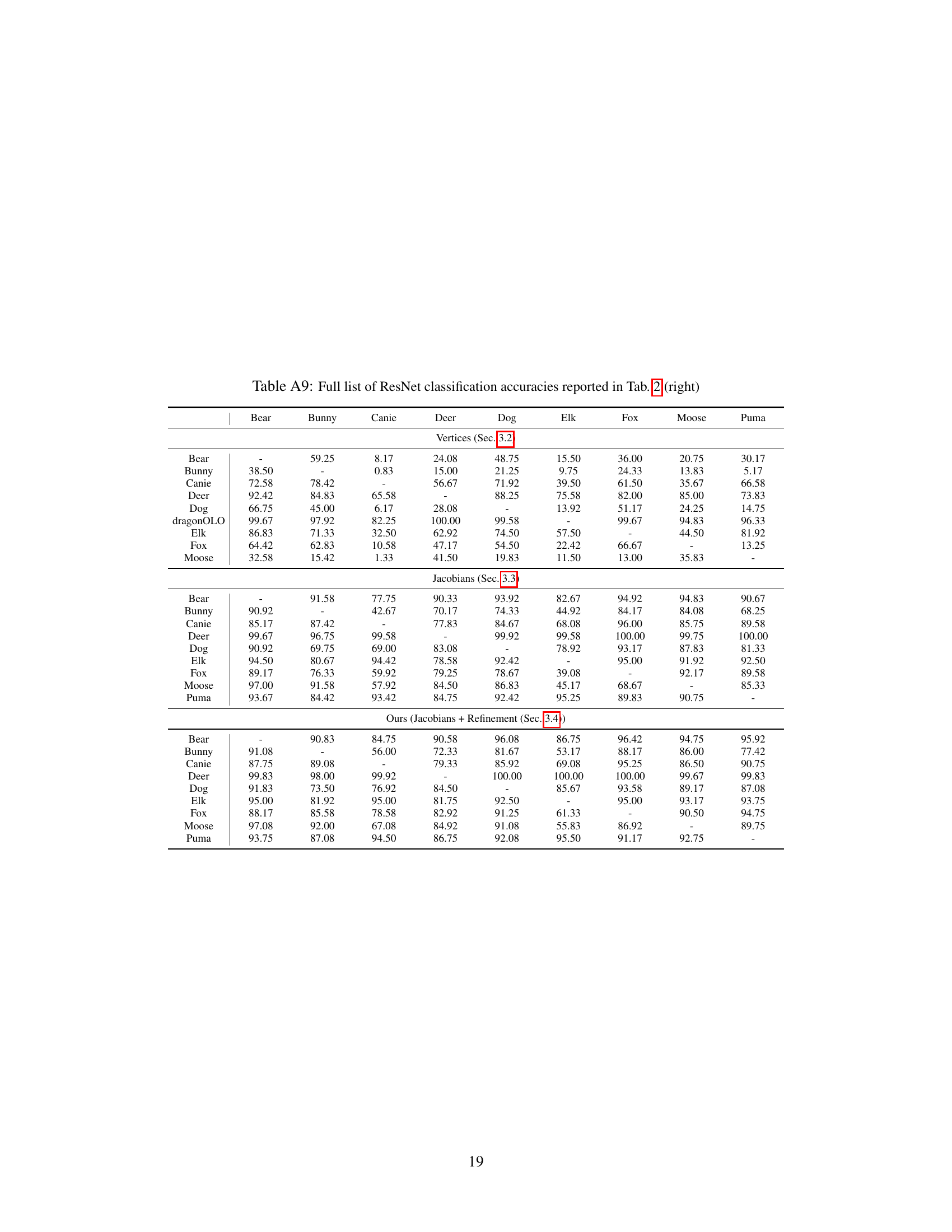

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different variations of the proposed framework for pose transfer. The left side shows results using poses from the source shapes in the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset. The right side shows results using poses generated by the cascaded diffusion model. The variations compared include using vertex-only representations versus Jacobian fields, and whether or not a per-identity refinement module was used. The metrics used for evaluation include FID, KID, and ResNet accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Ablation study using the poses from the source shapes in DeformingThings4D-Animals [23] dataset (left) and the poses generated from our cascaded diffusion model.

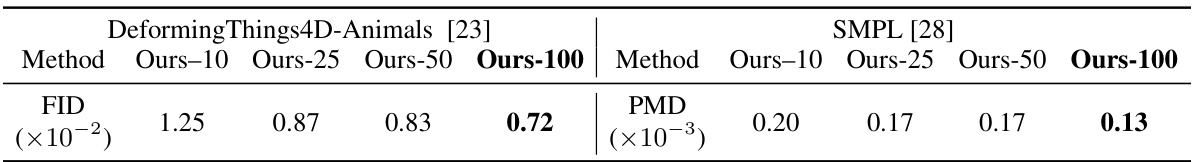

🔼 This table presents quantitative results obtained from different versions of the proposed framework. Each version varies in the number of keypoints extracted (10, 25, 50, and 100). The results are split for two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL. The metrics used are FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) for the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset and PMD (Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance) for the SMPL dataset. Lower FID and PMD scores indicate better performance. The table aims to demonstrate the robustness of the framework to variations in the number of keypoints extracted, showing that reducing this number doesn’t significantly impact performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Quantitative results from the variants of our framework trained to extract different number of keypoints. Ours-N denotes a variant of our network trained to extract N keypoints.

🔼 This table presents quantitative evaluation metrics for pose transfer experiments conducted on two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL. For the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset, the metrics used are Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Kernel Inception Distance (KID), and ResNet classification accuracy. For the SMPL dataset, PMD (Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance), FID, KID, and ResNet accuracy are reported. The table compares the performance of the proposed method against three baseline methods (NJF, SPT, ZPT). Lower FID and KID values indicate better visual quality, while a lower PMD and higher ResNet accuracy indicate better pose transfer accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against several baselines on two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL. For each dataset and method, it reports the FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), KID (Kernel Inception Distance), ResNet accuracy, and PMD (Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance) scores. Lower FID and KID scores indicate better visual quality, while higher ResNet accuracy implies better pose classification. Lower PMD indicates better geometric accuracy in pose transfer. The table demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method compared to the baselines across multiple metrics on both datasets.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against several baselines on two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL human shapes. The metrics used are FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), KID (Kernel Inception Distance), ResNet accuracy (classification accuracy using a ResNet-18 network), and PMD (Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance). Lower FID and KID scores indicate better visual quality, while higher ResNet accuracy and lower PMD indicate better pose transfer accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques for pose transfer, using two distinct datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL. It shows the performance metrics (FID, KID, ResNet Accuracy, PMD) achieved by each method on each dataset. Lower FID and KID values indicate better performance in terms of image similarity, while higher ResNet Accuracy reflects better preservation of pose identity. PMD represents Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance and applies only to the SMPL dataset, indicating the accuracy of pose transfer.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against other state-of-the-art methods for pose transfer on two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL. The metrics used for evaluation include FID, KID, ResNet accuracy, and PMD (for SMPL only). Lower FID and KID scores indicate better visual fidelity, higher ResNet accuracy represents better pose classification, and lower PMD signifies better geometric accuracy. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of both visual fidelity and geometric accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against several baselines for pose transfer on two datasets: DeformingThings4D-Animals and SMPL. The metrics used for comparison include FID, KID, ResNet accuracy, and PMD (for SMPL only). Lower FID and KID scores indicate better visual quality. Higher ResNet accuracy reflects better pose classification. Lower PMD (Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance) means better geometric accuracy of pose transfer. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of all metrics across both datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness in pose transfer and generalization.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the experiments using the DeformingThings4D-Animals dataset [23] and the human shape dataset populated using SMPL [28].

Full paper#