TL;DR#

Traditional Bayesian methods struggle with large, streaming datasets because recalculating posteriors from scratch is computationally expensive. Variational inference (VI) offers a scalable solution, but existing VI methods are often analytically intractable for discrete parameter spaces. This is a major hurdle when working with discrete data, such as trees or graphs frequently used in machine learning, biology, and network analysis.

This paper introduces Streaming Bayes GFlowNets (SB-GFlowNets), a novel approach that efficiently addresses these challenges. SB-GFlowNets leverages GFlowNets, a powerful class of amortized samplers for discrete compositional objects, to approximate and update posteriors efficiently as new data arrives. The authors present two training schemes (streaming balance and divergence-based updates), analyze their theoretical properties, and demonstrate empirically that SB-GFlowNets is significantly faster than repeatedly training a standard GFlowNet, while maintaining comparable accuracy. This approach has notable implications for various fields that use discrete data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with streaming data and Bayesian inference, particularly in areas like phylogenetics and preference learning. It introduces a novel and efficient method, offering significant advancements in handling large datasets and dynamic environments. The proposed algorithm paves the way for real-time, adaptive models.

Visual Insights#

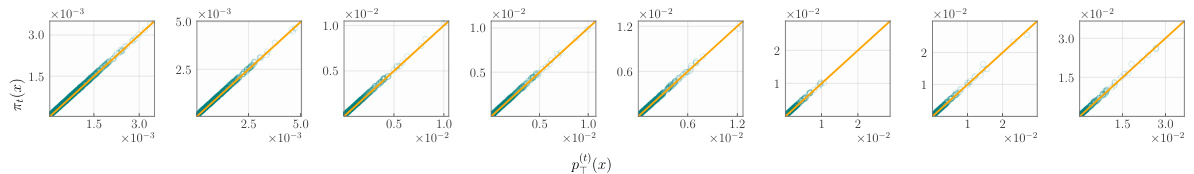

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying SB-GFlowNets to a linear preference learning problem with integer-valued features. Each subplot shows a comparison of the marginal distribution learned by the SB-GFlowNet and the true posterior distribution at a given stage in the streaming process. The leftmost subplot shows the comparison after the first update, and subsequent subplots show the comparisons after additional updates. The plots demonstrate how well the SB-GFlowNet’s learned distributions match the true posterior distributions as more data are processed during the streaming updates.

read the caption

Figure 2: SB-GFlowNet accurately learns the posterior over the utility’s parameters in a streaming setting. Each plot compares the marginal distribution learned by SB-GFlowNet (horizontal axis) and the targeted posterior distribution (vertical axis) at increasingly advanced stages of the streaming process, i.e., from π₁(·|D1) (left-most) to π₈(·|D1:₈) (right-most).

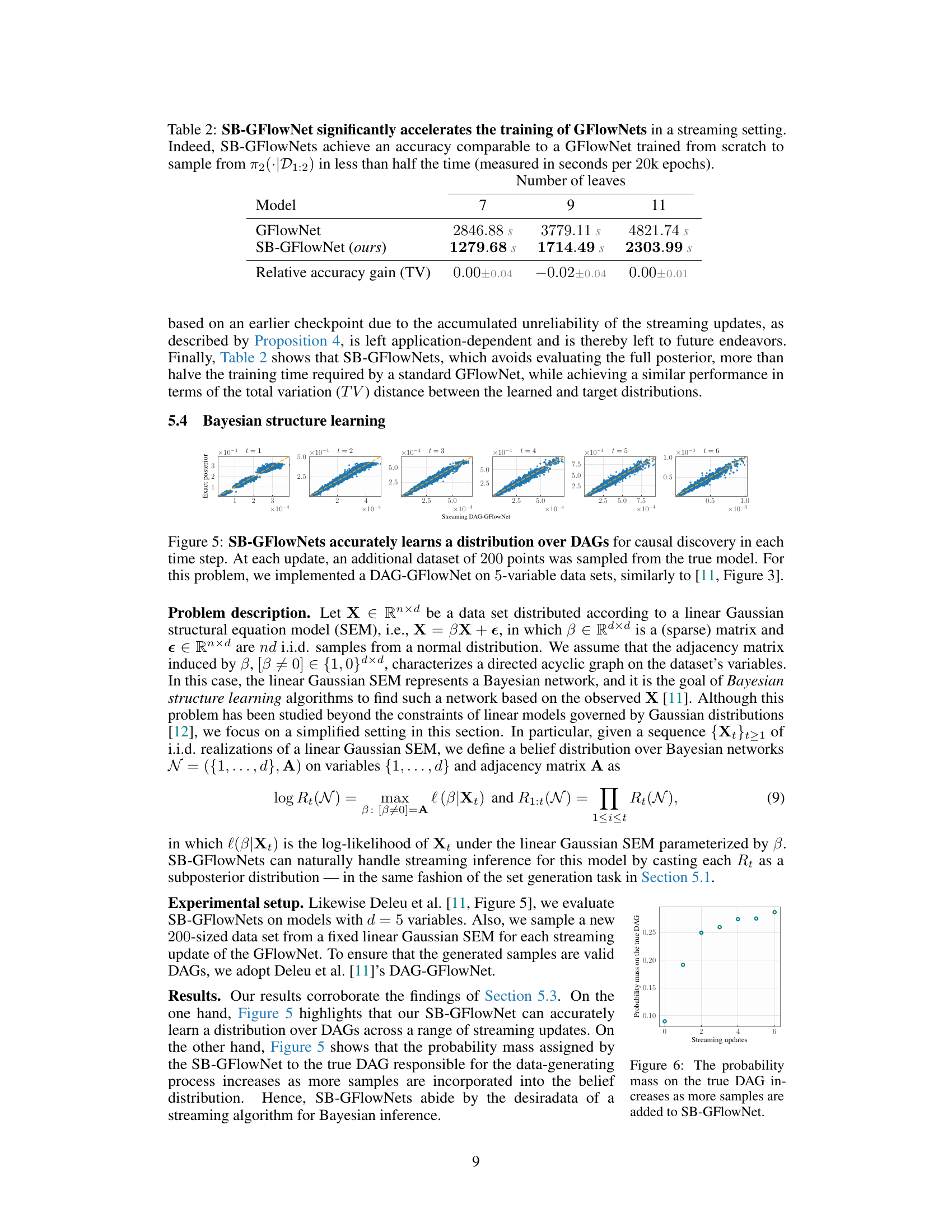

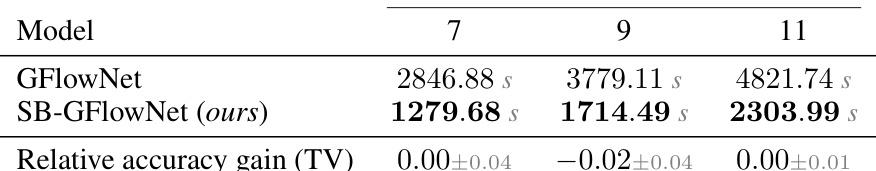

🔼 This table compares the training time and accuracy of SB-GFlowNets versus standard GFlowNets for phylogenetic inference with different numbers of leaves in the phylogenetic tree. SB-GFlowNets show a significant reduction in training time while maintaining comparable accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: SB-GFlowNet significantly accelerates the training of GFlowNets in a streaming setting. Indeed, SB-GFlowNets achieve an accuracy comparable to a GFlowNet trained from scratch to sample from π2(·|D1:2) in less than half the time (measured in seconds per 20k epochs).

In-depth insights#

Streaming Bayes#

Streaming Bayes methods offer a powerful paradigm for handling continuous data streams by incorporating new information incrementally without recomputing from scratch. This is particularly valuable in Big Data scenarios, where complete data reprocessing is computationally prohibitive. The core idea revolves around updating a prior distribution with each new data point, iteratively refining the posterior. Variational Inference (VI) is frequently employed to approximate the often intractable posterior distributions, making these methods computationally feasible. However, challenges remain in efficiently updating VI approximations in a streaming fashion, especially for discrete state spaces, where standard VI techniques often fall short. Furthermore, guaranteeing the accuracy and convergence of streaming Bayesian methods over prolonged updates is critical, as the accumulation of minor errors in each step could potentially escalate and affect overall accuracy. Finally, the choice of the appropriate approximation method, such as VI or other methods, influences the effectiveness and computational efficiency of the streaming Bayesian approach. Different methods’ performance may vary considerably depending on the nature of the data and the specific application.

GFlowNet’s Power#

GFlowNets demonstrate significant power in addressing challenges inherent in traditional Bayesian inference, particularly for high-dimensional discrete spaces. Their ability to learn policies for efficiently sampling from complex, unnormalized probability distributions is a major advantage. Unlike methods like MCMC, GFlowNets offer amortized inference, making them computationally more efficient for large datasets. The framework is flexible, adaptable to different problem structures and loss functions, and amenable to both exact and approximate inference. However, scalability remains a concern for extremely large state spaces, and further research is needed to refine training strategies and fully explore the theoretical implications of approximation error propagation in streaming settings. The effectiveness of GFlowNets heavily depends on appropriate model design and careful selection of hyperparameters, underscoring the importance of further investigation into these factors.

Streaming Updates#

The concept of “Streaming Updates” in the context of a research paper likely revolves around the ability of a model or system to incrementally incorporate new data without requiring a complete reprocessing of the entire dataset. This is crucial for handling large, continuously arriving streams of data, such as those encountered in real-time applications or with Big Data. Efficient streaming updates are essential for scalability and responsiveness, avoiding computationally expensive retraining procedures. The method for achieving streaming updates would likely be a core contribution of the paper, potentially involving novel algorithms or adaptations of existing techniques to maintain model accuracy while minimizing computational overhead. The analysis of the impact of incremental updates on model accuracy and efficiency, including a discussion of potential error accumulation, would also be a key aspect. Error bounds and strategies for mitigating the effects of data drift or concept drift would be important considerations. Overall, the section on Streaming Updates would provide a detailed description of how new data is integrated into the system, the associated computational complexities, and the effectiveness of the proposed approach in achieving accurate and efficient continuous learning from streaming data.

Theoretical Bounds#

A theoretical bounds section in a research paper would rigorously analyze the performance guarantees of proposed methods. It would likely involve deriving upper bounds on errors, demonstrating that the proposed method’s performance is within a certain margin of optimality. This section might also include lower bounds, proving that no algorithm can perform better than a specific threshold under given assumptions. The key is establishing a mathematically sound relationship between the theoretical results and the practical performance. The analysis often relies on simplifying assumptions such as data independence or specific distributional forms, and it’s crucial to acknowledge their limitations and potential impact on the validity of the bounds. A strong theoretical bounds section helps to build confidence in the method’s robustness and reliability, demonstrating a deeper understanding beyond empirical observations.

Future Extensions#

The concept of streaming Bayesian inference, while powerful, presents several avenues for future exploration. Improving the efficiency of the SB-GFlowNet update process is crucial; the current method, while faster than retraining from scratch, could benefit from more sophisticated optimization techniques. Theoretical analysis of error accumulation during streaming updates requires further investigation to provide tighter bounds and a more nuanced understanding of when checkpointing is necessary. The proposed SB-GFlowNet currently handles discrete parameter spaces; extending it to continuous spaces or hybrid models would significantly broaden its applicability. Additionally, developing robust methods for handling changes in the data distribution over time is paramount for ensuring long-term accuracy. Finally, exploring alternative architectures and training methods, beyond simple GFlowNet extensions, could unlock even greater performance gains and potentially address current limitations. Further investigation into applications in other domains, like reinforcement learning or time-series analysis, is highly encouraged.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy of SB-GFlowNet in learning the posterior distribution over a parameter in a streaming setting. Each subplot displays a comparison between the marginal distribution learned by the model and the true posterior at different stages of the streaming process. The plots show that the learned distribution closely matches the true posterior as more data is processed, demonstrating the model’s accuracy in learning the posterior distribution dynamically.

read the caption

Figure 2: SB-GFlowNet accurately learns the posterior over the utility's parameters in a streaming setting. Each plot compares the marginal distribution learned by SB-GFlowNet (horizontal axis) and the targeted posterior distribution (vertical axis) at increasingly advanced stages of the streaming process, i.e., from π₁(·|D1) (left-most) to π8(·|D1:8) (right-most).

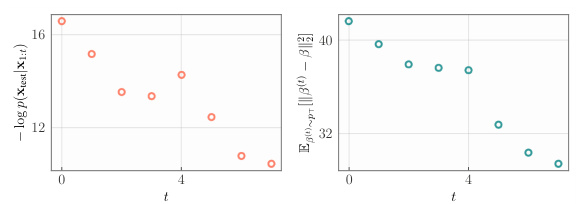

🔼 This figure shows the predictive performance of SB-GFlowNets in terms of predictive negative log-likelihood (NLL) and mean squared error (MSE). It demonstrates that as more data chunks are processed (indicating an increase in the amount of streaming data used for training), the predictive NLL decreases for both SB-GFlowNets and the ground truth. This shows the model’s ability to learn effectively from streaming data and maintain accuracy over time, and the similarity between the SB-GFlowNet’s performance and the ground truth.

read the caption

Figure 3: Predictive performance of SB-GFlowNets in terms of pred. NLL and avg. MSE. SB-GFlowNets behaves similarly to the ground-truth, wrt how the NLL evolves as a function of data chunks.

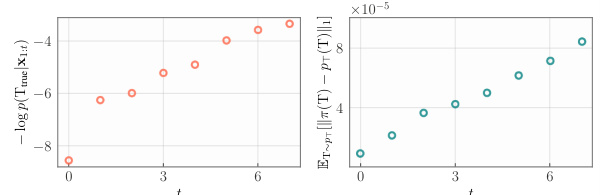

🔼 This figure shows two plots. The left plot shows the negative logarithm of the probability of the true phylogeny, which is a measure of how well the model’s learned distribution fits the true posterior distribution. The y-axis is the negative log probability and x-axis is the number of streaming updates. The right plot shows the expected L1 distance between the true and learned posterior distributions over the set of trees, which is another measure of how well the model is learning. The y-axis is the expected L1 distance and x-axis is the number of streaming updates. Both plots illustrate the performance of SB-GFlowNets over multiple streaming updates.

read the caption

Figure 4: SB-GFlowNet's accurate fit to the true posterior in terms of the probability of the true phylogeny (left) and of the learned model's accuracy (right).

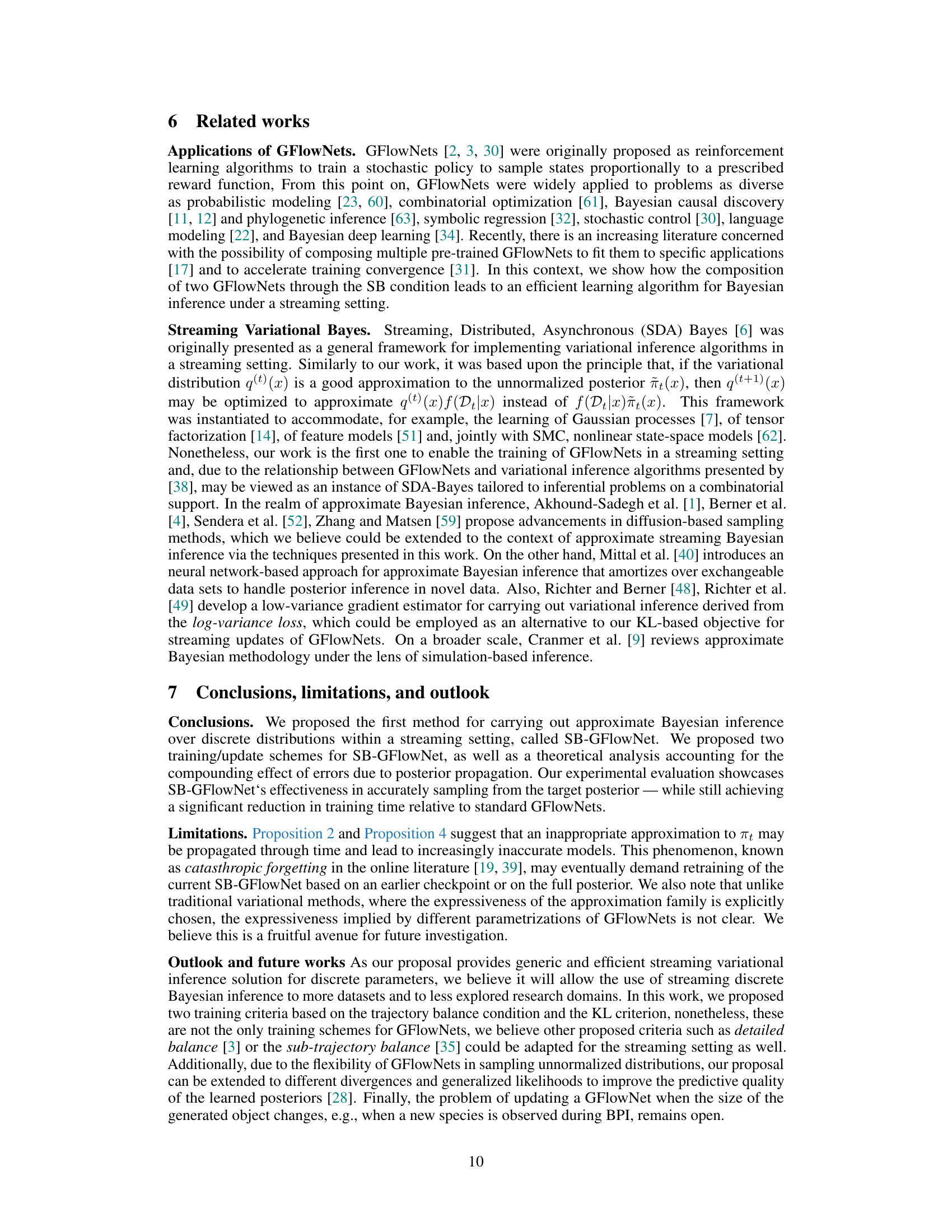

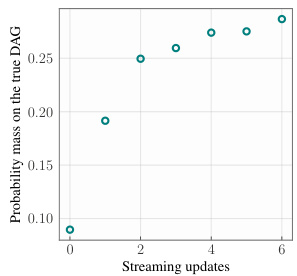

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy of SB-GFlowNets in learning the distribution over directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) for causal discovery. Each plot represents a different time step (t=1 to t=6), showing the learned distribution against the true posterior. As more data is added (each update adds 200 more data points), the accuracy of the learned distribution improves.

read the caption

Figure 5: SB-GFlowNets accurately learns a distribution over DAGs for causal discovery in each time step. At each update, an additional dataset of 200 points was sampled from the true model. For this problem, we implemented a DAG-GFlowNet on 5-variable data sets, similarly to [11, Figure 3].

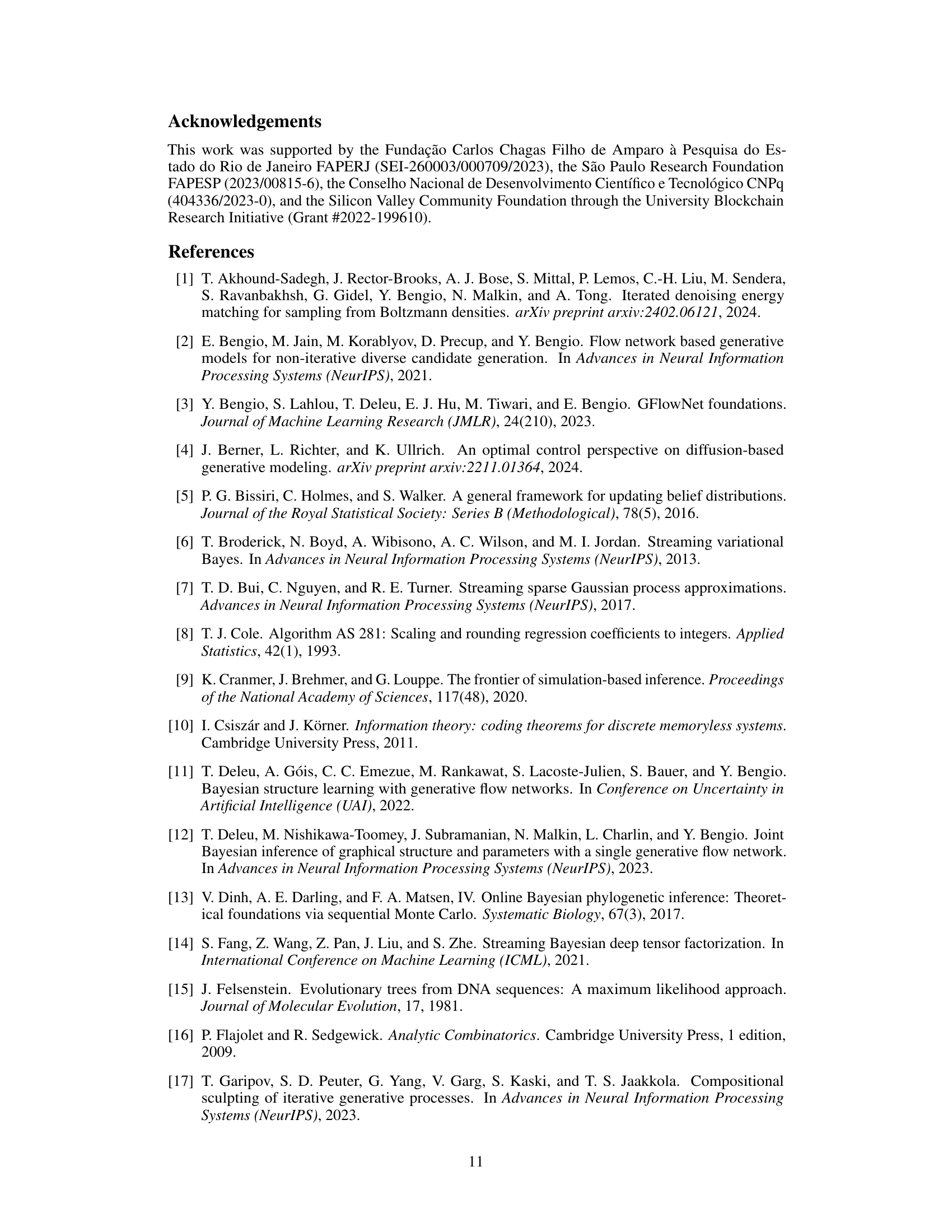

🔼 This figure shows how the probability mass assigned by the SB-GFlowNet to the true DAG that is responsible for generating the data increases with the number of streaming updates. It demonstrates the model’s ability to learn the true data-generating process more accurately as it receives more data.

read the caption

Figure 6: The probability mass on the true DAG increases as more samples are added to SB-GFlowNet.

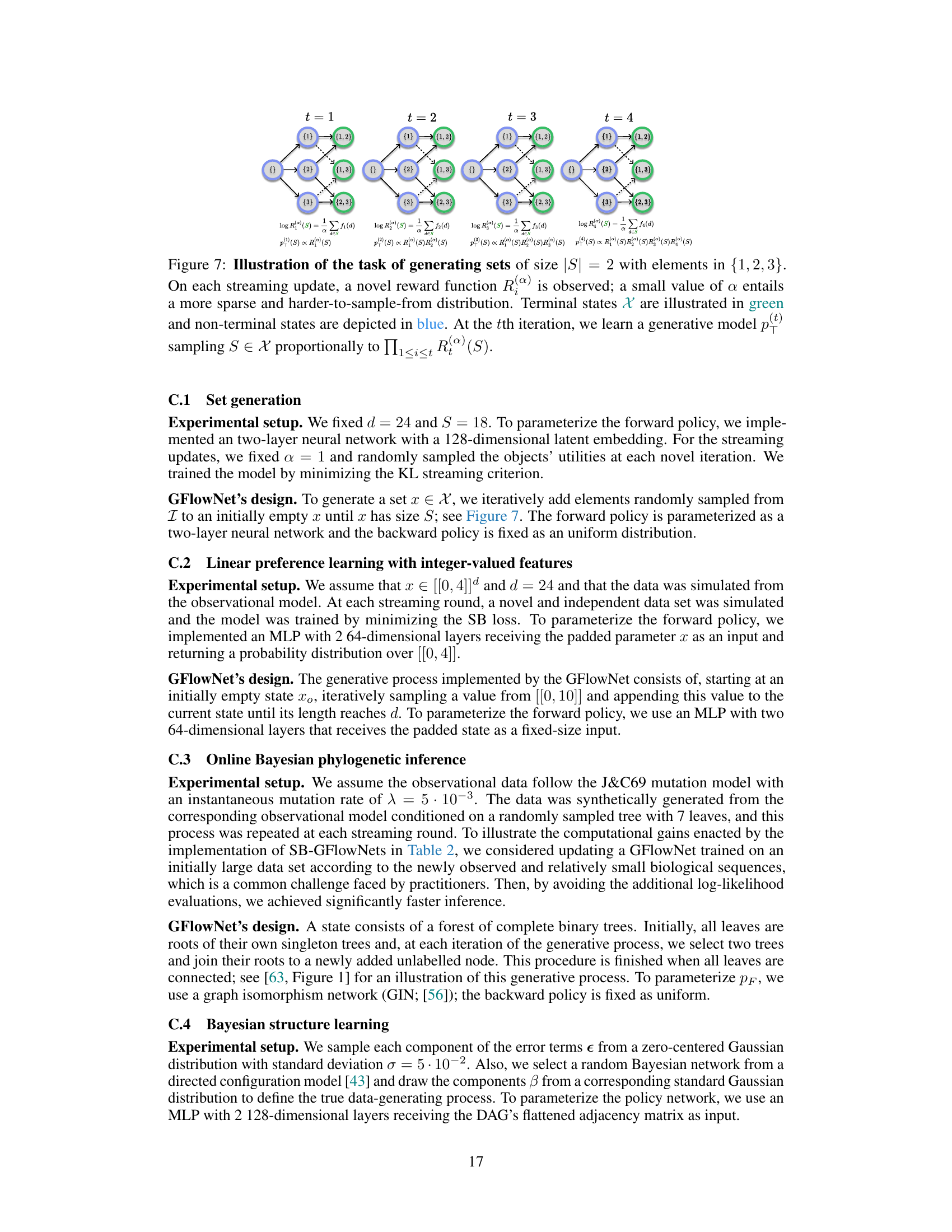

🔼 This figure illustrates the set generation task used in the paper to demonstrate the effectiveness of SB-GFlowNets. Each panel shows a different stage (t=1,2,3,4) of a streaming update where a novel reward function is introduced at each step. The goal is to learn a probability distribution over sets of size 2 from elements {1,2,3}. The nodes represent states in a generative model, with terminal states (sets) in green and non-terminal states in blue. The edges show transitions between states, and the associated reward functions (R(i)(S)) influence the learned probability distribution at each time step.

read the caption

Figure 7: Illustration of the task of generating sets of size |S| = 2 with elements in {1,2,3}. On each streaming update, a novel reward function R∞) is observed; a small value of a entails a more sparse and harder-to-sample-from distribution. Terminal states X are illustrated in green and non-terminal states are depicted in blue. At the tth iteration, we learn a generative model p(+) sampling S ∈ X proportionally to Π1≤i≤t R(i)(S).

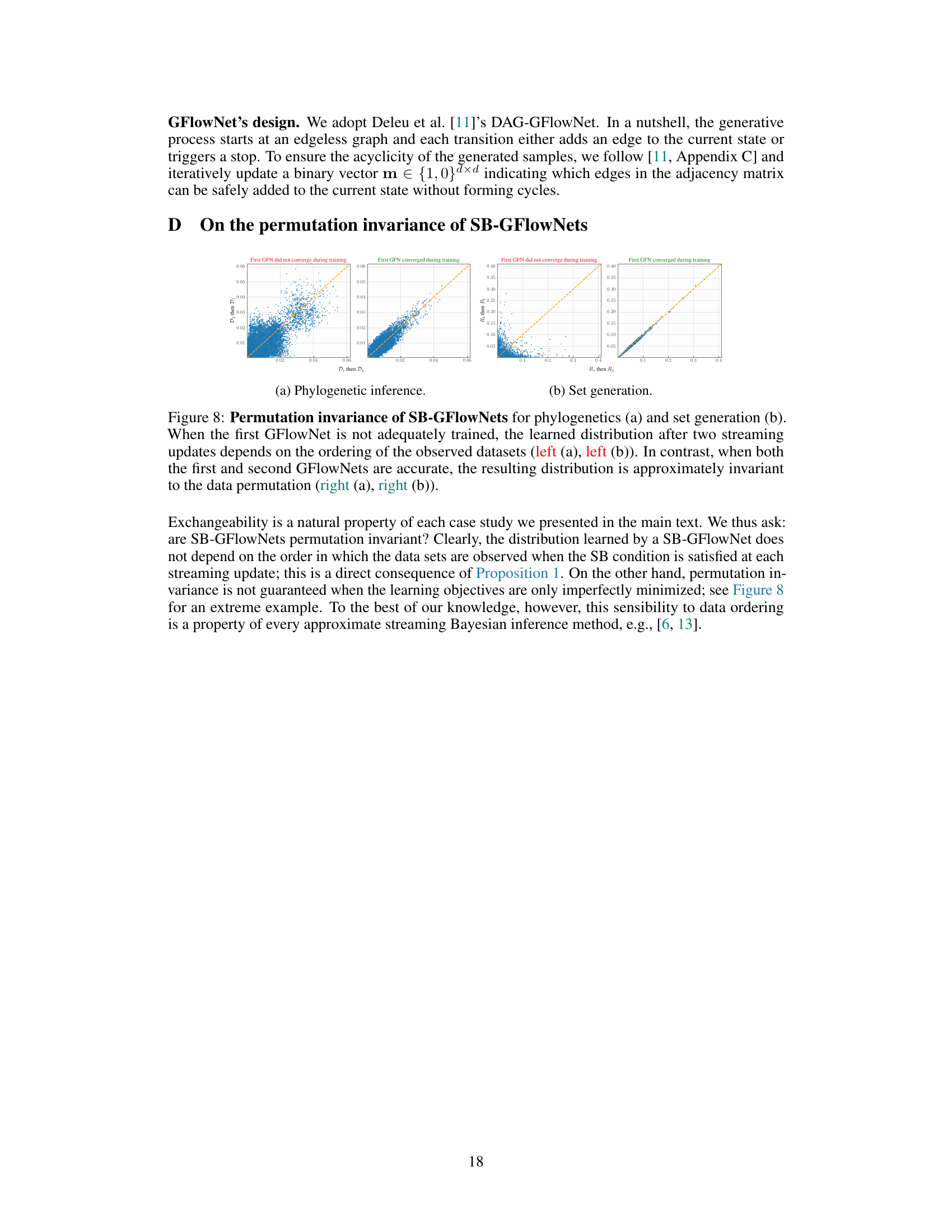

🔼 This figure demonstrates the permutation invariance property of SB-GFlowNets. The left-hand side plots show that if the initial GFlowNet is poorly trained, the final distribution after two updates depends on the order in which data arrives. The right-hand side plots show that when both the initial and subsequent GFlowNets are accurately trained, the final distribution is largely invariant to data order.

read the caption

Figure 8: Permutation invariance of SB-GFlowNets for phylogenetics (a) and set generation (b). When the first GFlowNet is not adequately trained, the learned distribution after two streaming updates depends on the ordering of the observed datasets (left (a), left (b)). In contrast, when both the first and second GFlowNets are accurate, the resulting distribution is approximately invariant to the data permutation (right (a), right (b)).

Full paper#