TL;DR#

Many existing second-order methods for solving minimax optimization problems require either a line search or solving auxiliary subproblems, which limits their applicability. Additionally, most methods rely heavily on knowing the Lipschitz constant of the Hessian. These requirements can significantly impact both efficiency and practical use.

This paper introduces adaptive second-order optimistic methods that cleverly address these issues. The proposed methods use a recursive, adaptive step size definition, eliminating the need for line search entirely. Further, a parameter-free variant is developed that eliminates the need for the Hessian’s Lipschitz constant, making these methods both efficient and widely applicable. The paper rigorously analyzes the proposed methods demonstrating that they achieve optimal convergence rates. Experimental results showcase superior performance compared to existing approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in minimax optimization because it presents novel adaptive, line-search-free second-order methods that achieve optimal convergence rates. These methods are simpler and more efficient than existing approaches, opening new avenues for research in this rapidly developing area of machine learning and optimization.

Visual Insights#

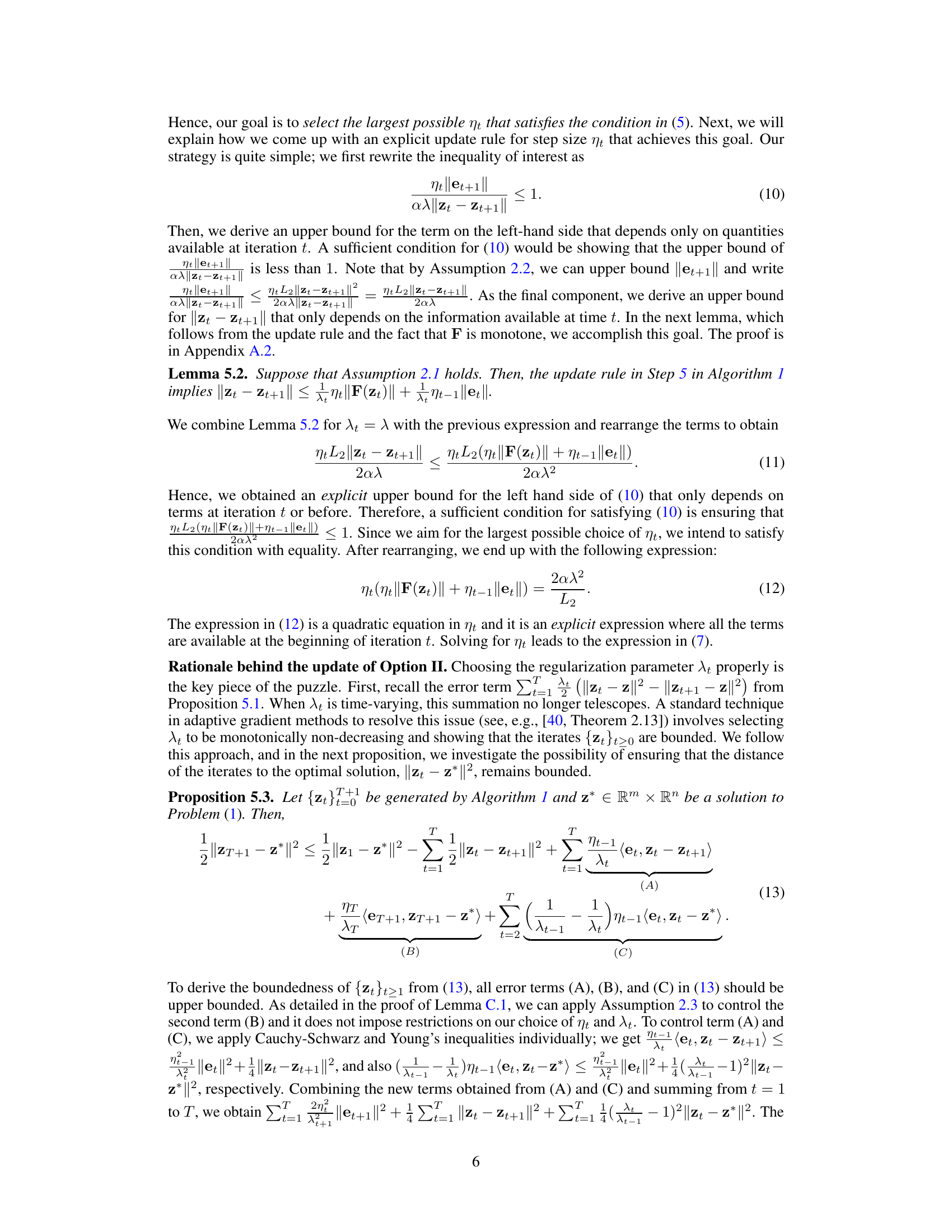

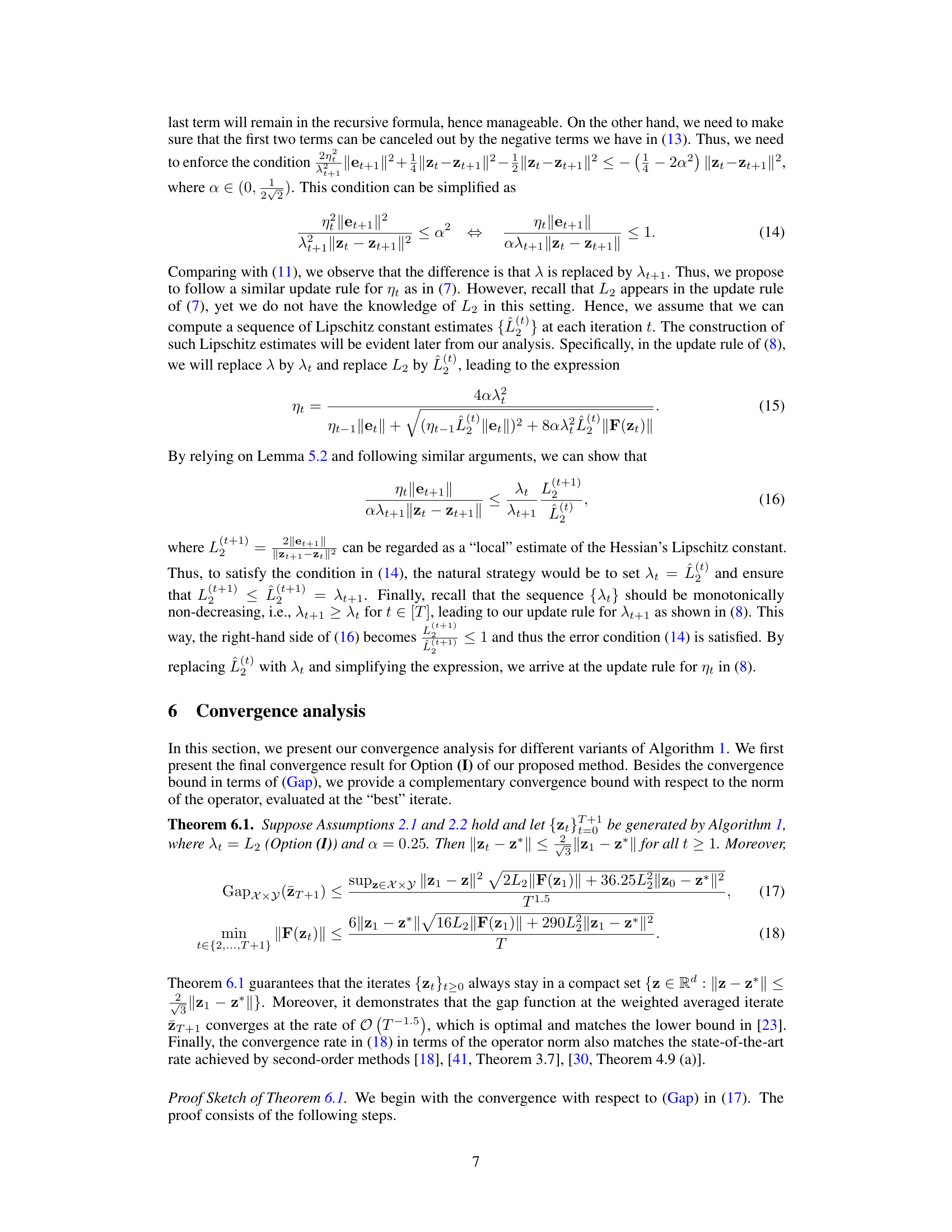

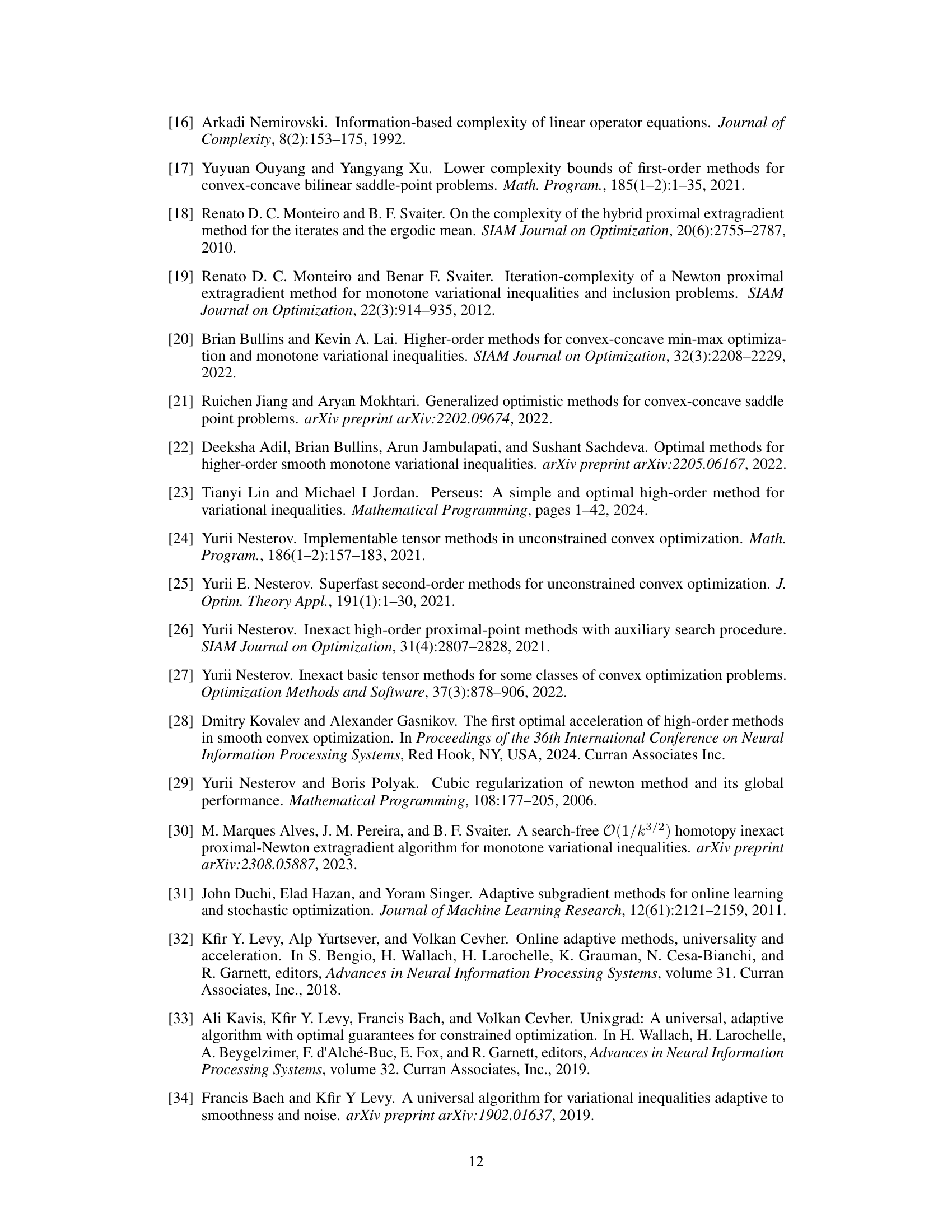

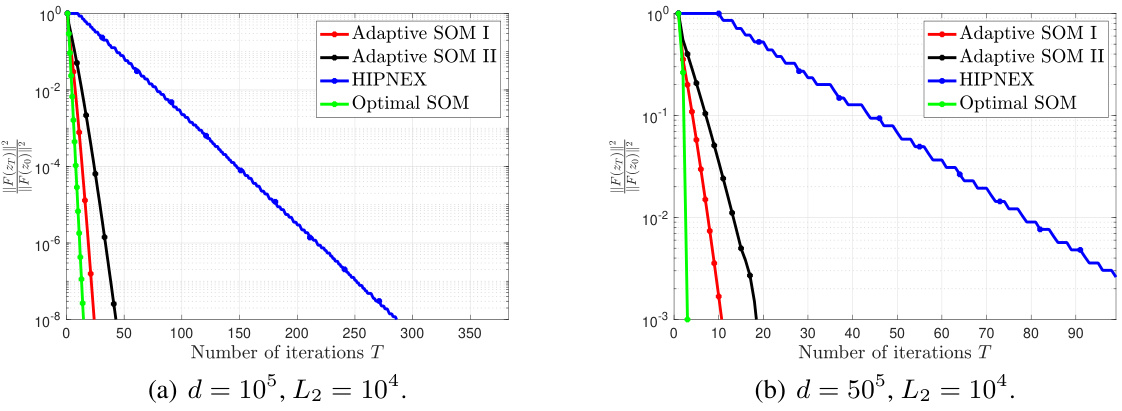

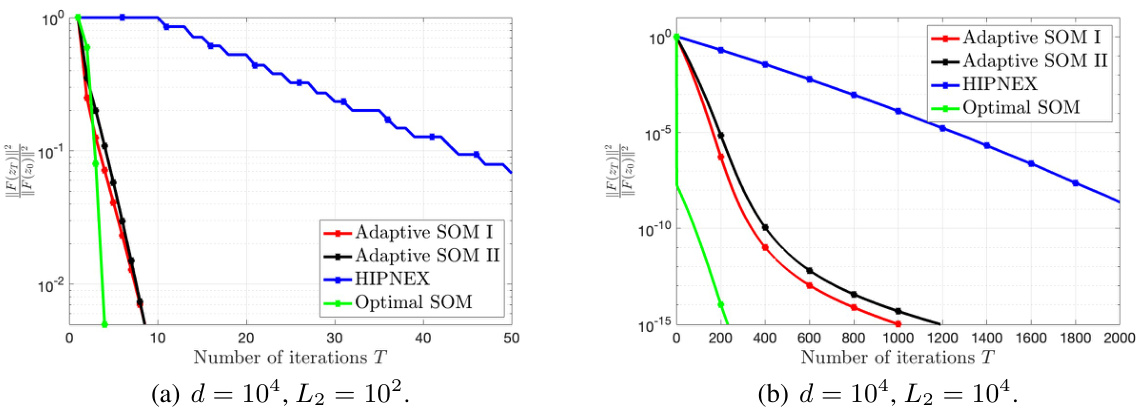

🔼 This figure compares the runtime performance of four different algorithms: Adaptive SOM I, Adaptive SOM II, HIPNEX, and Optimal SOM, on a synthetic min-max problem. The x-axis represents the runtime in seconds, and the y-axis shows the value of ||F(zT)||²/||F(z0)||², which measures the convergence of the algorithms. The figure shows two subplots: (a) with dimension d = 10⁵ and (b) with dimension d = 5 * 10⁵. The Lipschitz constant L2 is set to 10⁴ in both subplots. The results demonstrate the superior runtime performance of Adaptive SOM I and II, especially when the problem dimension is large.

read the caption

Figure 1: Synthetic min-max problem: Runtimes under large dimension regime with L2 = 104.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Minimax#

Adaptive minimax methods represent a significant advancement in optimization, addressing the challenges of solving minimax problems where the objective function is not fully known or changes over time. Adaptivity is crucial because it allows the algorithm to adjust its strategy based on the observed behavior of the function, leading to faster convergence and improved robustness. Unlike traditional minimax methods that rely on fixed parameters or strong assumptions, adaptive approaches dynamically adjust parameters such as step sizes and regularization terms, making them better suited for complex, real-world scenarios. Optimal convergence rates are a key feature, signifying that these algorithms are theoretically efficient; however, the practical performance is highly dependent on proper parameter tuning and careful implementation. The core ideas often involve recursively updating step sizes based on gradient information, prediction errors, or local curvature estimates. Parameter-free versions, eliminating the need for prior knowledge of problem parameters such as Lipschitz constants, are particularly desirable for practical applications. Challenges in adaptive minimax optimization include balancing exploration and exploitation, maintaining stability while adapting rapidly to change, and ensuring the algorithms remain efficient and robust across a wider range of problems.

Optimal Second-Order#

The concept of “Optimal Second-Order” methods in optimization signifies algorithms that leverage second-order derivative information (Hessian matrix) to achieve the best possible convergence rate for a given problem class. Optimality, in this context, often refers to achieving a theoretical lower bound on the number of iterations required to reach a solution within a specified tolerance. Second-order methods generally outperform first-order methods (which only use gradients) in terms of convergence speed, particularly for well-conditioned problems, but they come at the cost of higher computational complexity per iteration. Adaptivity is often a desirable feature, allowing the algorithm to adjust its step size or other parameters based on the problem’s characteristics, thus improving robustness and efficiency. Line search procedures are frequently employed but add computational overhead and can be problematic. Parameter-free methods represent an ideal scenario, requiring no prior knowledge of problem-specific parameters (like Lipschitz constants), making them more readily applicable in real-world scenarios. The research area focuses on designing algorithms that gracefully balance optimality, adaptivity, and computational efficiency to provide practical and effective solutions for various min-max or saddle point problems.

Line Search-Free#

The concept of ‘Line Search-Free’ in optimization algorithms is significant because line searches, while ensuring convergence, often add computational overhead. Eliminating the line search simplifies the algorithm’s update rule, making it more computationally efficient, especially in high-dimensional spaces. This is particularly crucial for second-order methods, where line searches are computationally more expensive. The trade-off lies in finding a suitable adaptive step size that guarantees convergence without the line search’s guarantees. The success of a line search-free method hinges on the robustness of its step-size selection mechanism, which must be adaptive and accurately reflect the local curvature of the objective function to achieve optimal convergence rates. A well-designed adaptive step size is paramount for the practicality and efficiency of these algorithms. While theoretical guarantees are important, the practicality of line search-free methods needs to be demonstrated empirically, which involves careful evaluation across a range of problem instances and dimensions.

Parameter-Free#

The concept of a “Parameter-Free” method in optimization is appealing due to its potential to reduce the reliance on hand-tuning hyperparameters which are often problem-specific and require extensive experimentation. A parameter-free approach promises greater ease of use and broader applicability across diverse problems. The absence of pre-defined parameters shifts the challenge from tuning to designing an algorithm that adapts effectively to the problem’s inherent characteristics, relying instead on data-driven mechanisms for adaptation. However, achieving this adaptive behavior can introduce complexities. Robustness becomes paramount, as the method needs to reliably handle various problem instances without manual intervention, requiring rigorous theoretical guarantees of convergence and stability. The tradeoff between parameter-free simplicity and adaptive complexity needs careful consideration. Parameter-free optimizers often use more sophisticated mechanisms, such as recursive step size updates that locally estimate problem-specific quantities, potentially leading to more computationally expensive iterations, although this could be offset by reduced tuning time. Therefore, the true efficacy of parameter-free optimization is context-dependent and should be assessed carefully.

Hessian Lipschitz#

The concept of “Hessian Lipschitz” in optimization refers to the Lipschitz continuity of the Hessian matrix of a function. This property implies a bound on the change in the curvature of the function, ensuring that the second derivatives do not vary too wildly. This is crucial in many second-order optimization algorithms, such as those based on Newton’s method or its variants, because it guarantees convergence properties and allows for step size selection. In the context of minimax optimization, where the objective function is often non-convex-non-concave, Hessian Lipschitz conditions are usually applied to either the individual components of the objective function (convex and concave parts) or the operator derived from the objective function. The Lipschitz constant itself quantifies the smoothness of the Hessian, and its value is critical in determining convergence rates and choosing appropriate step sizes in iterative algorithms. Algorithms that assume Hessian Lipschitz continuity often have better theoretical convergence properties but are sensitive to the accuracy of the Lipschitz constant estimate. Adaptive schemes that attempt to locally estimate or track the Lipschitz constant can be more robust in practice, but might require additional assumptions (e.g., Lipschitz continuous gradient). Therefore, the presence and careful consideration of the Hessian Lipschitz assumption are fundamental in creating efficient and provably convergent second-order methods for both convex and non-convex optimization problems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure compares the runtime of Adaptive SOM I, Adaptive SOM II, HIPNEX, and Optimal SOM for solving a synthetic min-max problem under different problem dimensions (d = 10^5 and d = 5 * 10^5). The Lipschitz constant of the Hessian is set to L2 = 10^4. The figure demonstrates that both Adaptive SOM algorithms significantly outperform HIPNEX and Optimal SOM in terms of runtime, particularly when the problem dimension is large (d = 5 * 10^5).

read the caption

Figure 1: Synthetic min-max problem: Runtimes under large dimension regime with L2 = 104.

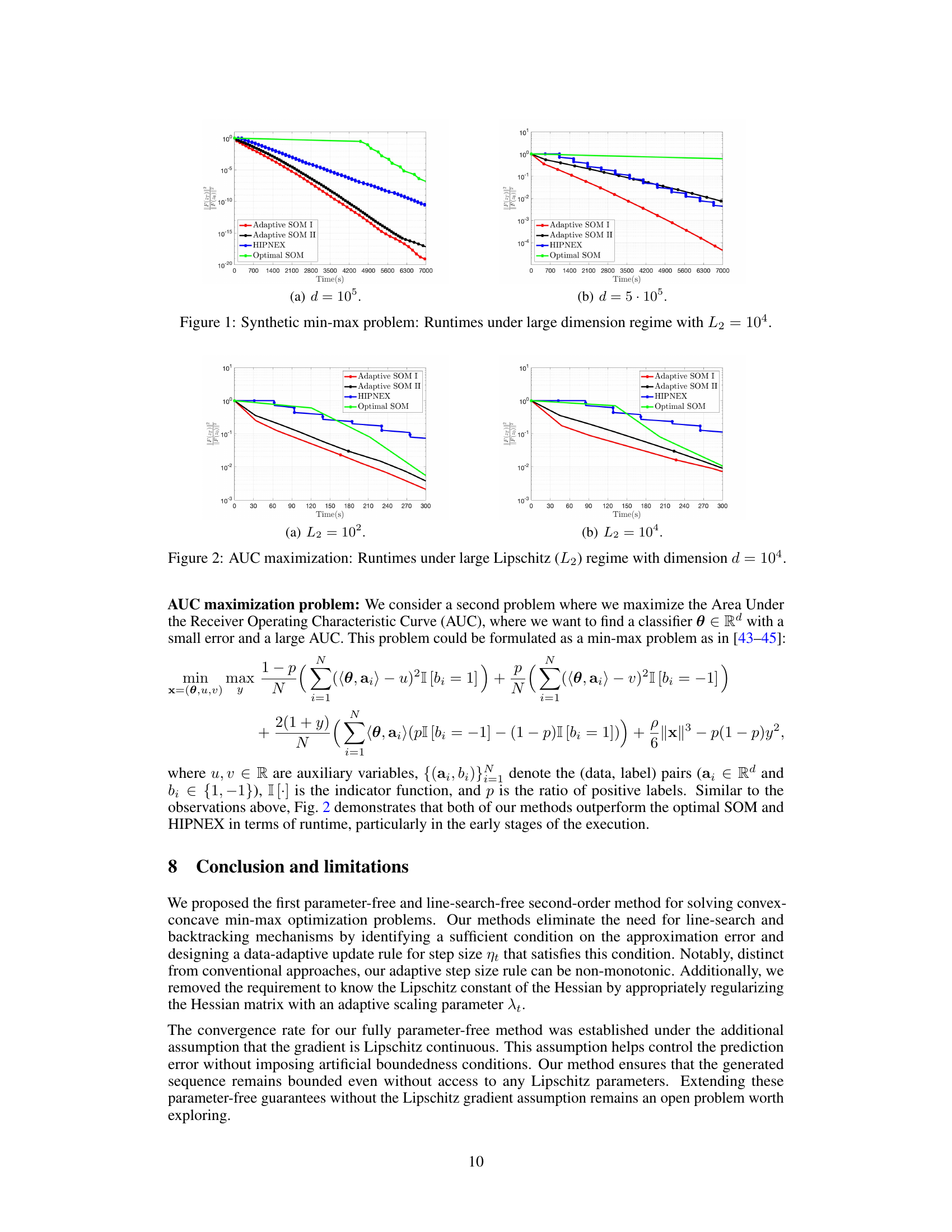

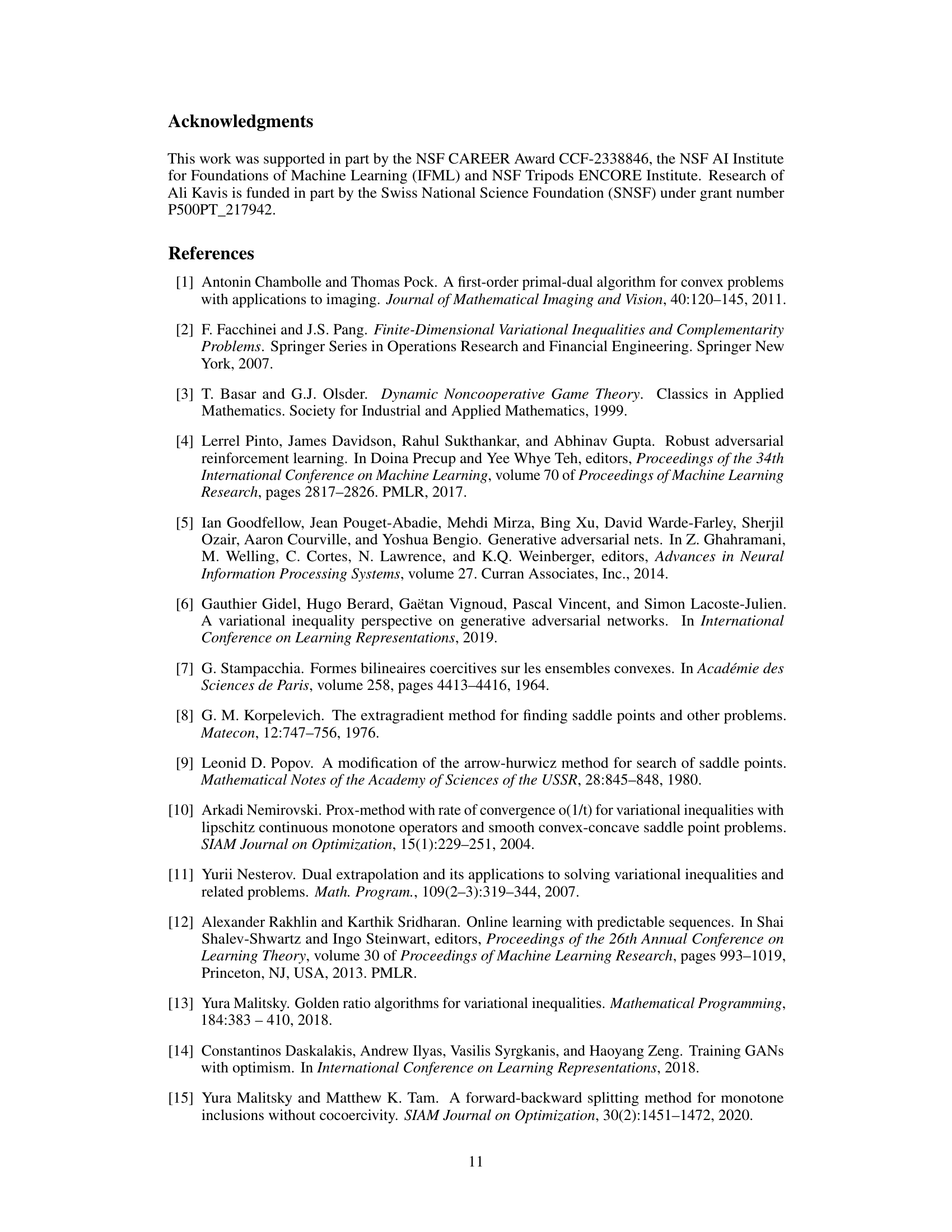

🔼 This figure compares the runtimes of five different algorithms for solving a synthetic min-max problem. The algorithms are Adaptive SOM I, Adaptive SOM II, HIPNEX, Optimal SOM, and a baseline method. The x-axis represents the runtime in seconds, and the y-axis represents the value of ||F(zT)||2/||F(z0)||2. The figure shows that Adaptive SOM I and Adaptive SOM II are significantly faster than the other algorithms, especially when the dimension of the problem is large (d = 5 * 10^5). This demonstrates the efficiency of the proposed adaptive second-order optimistic methods.

read the caption

Figure 1: Synthetic min-max problem: Runtimes under large dimension regime with L2 = 104.

🔼 The figure shows the runtime comparison of different second-order methods (Adaptive SOM I, Adaptive SOM II, HIPNEX, Optimal SOM) for solving a synthetic min-max problem with dimension d = 10^5 and d = 5 * 10^5. The Lipschitz constant L2 is set to 10^4. Adaptive SOM I and II are the proposed methods in the paper; HIPNEX represents the homotopy inexact proximal-Newton extragradient method, and Optimal SOM is the second-order optimistic method with line search. The plot demonstrates that the proposed methods significantly outperform the competing methods in terms of runtime, particularly in the high-dimensional case.

read the caption

Figure 1: Synthetic min-max problem: Runtimes under large dimension regime with L2 = 104.

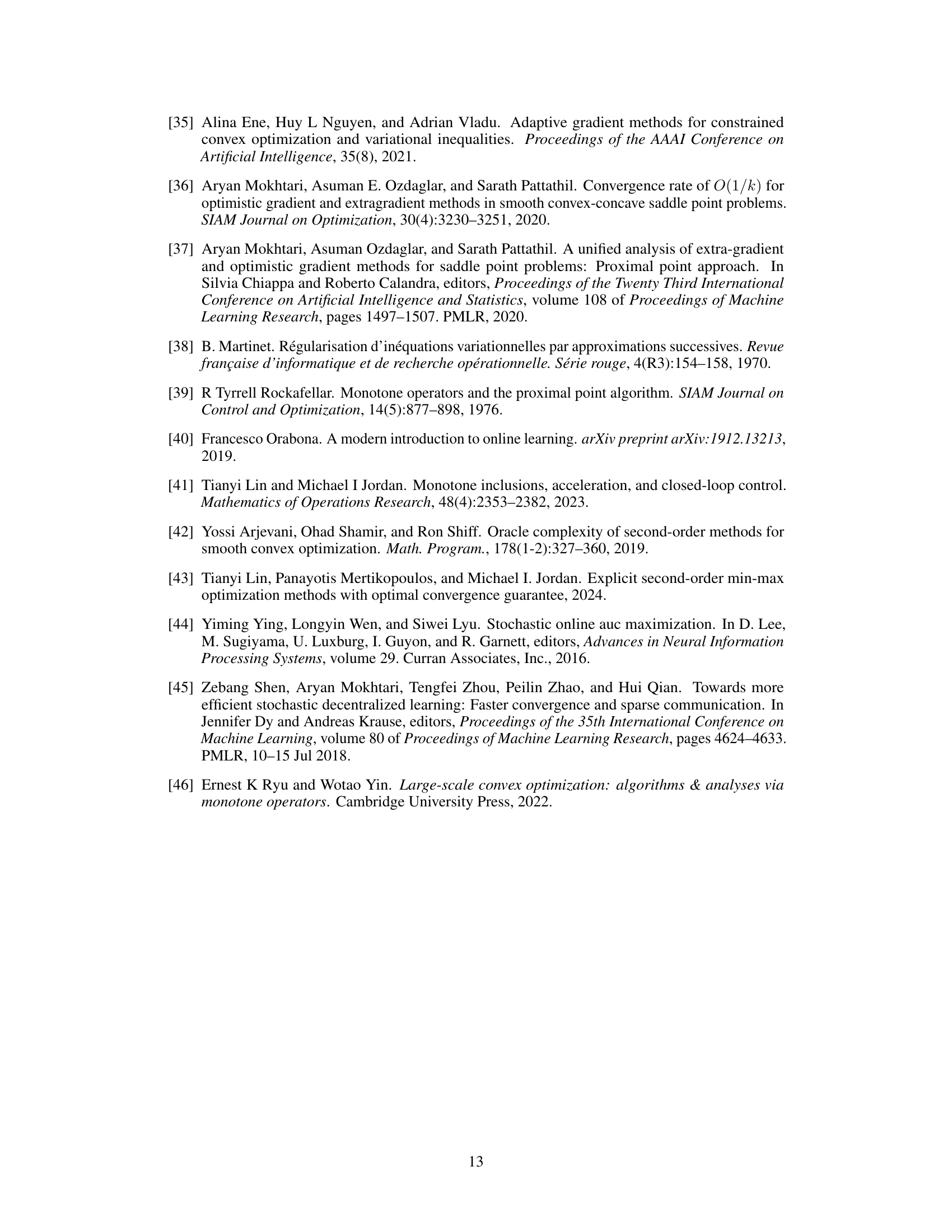

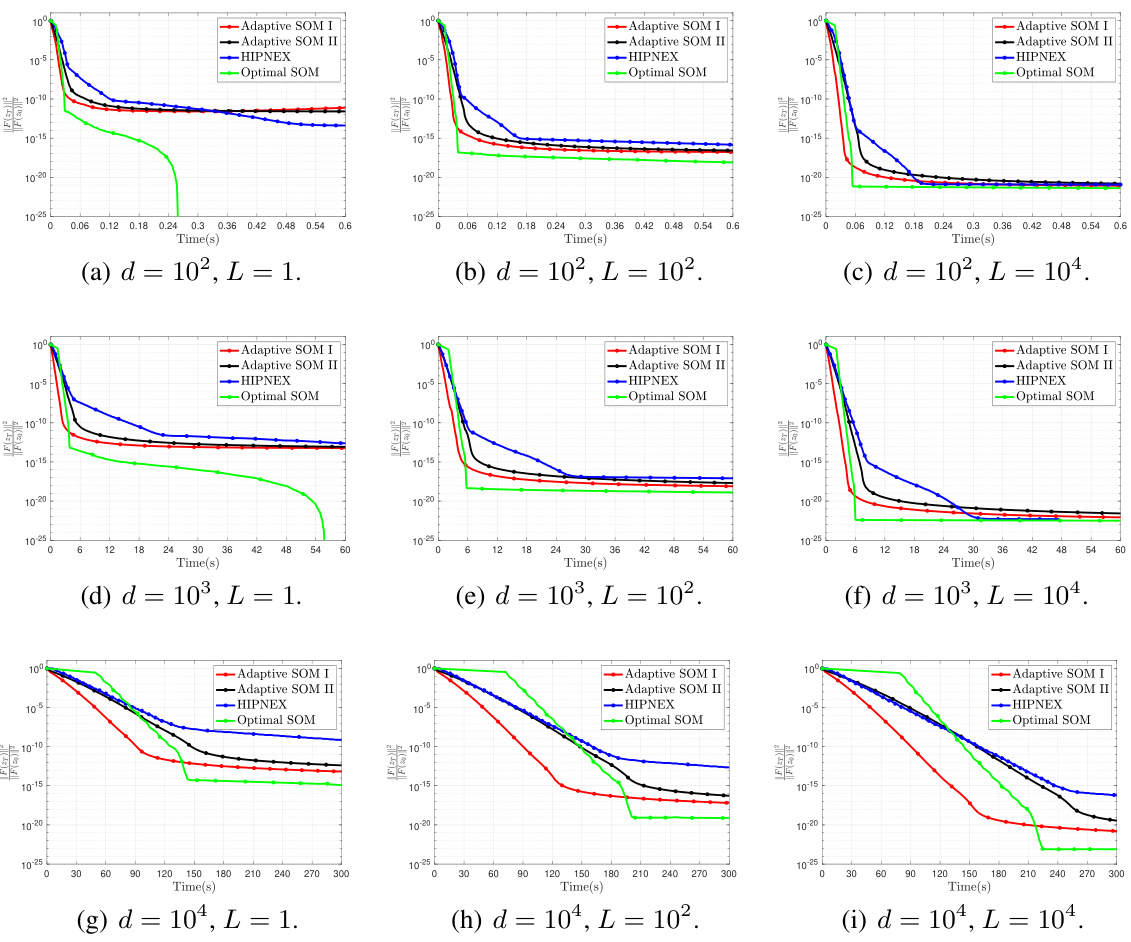

🔼 This figure presents additional plots of the convergence comparison with respect to runtime for the synthetic min-max problem. It expands on Figure 1 by providing a more detailed view of the performance of the different algorithms across various dimensions and Lipschitz constants. The plots show the convergence of the algorithms, highlighting the efficiency of the proposed Adaptive SOM I and II methods compared to the Optimal SOM and HIPNEX methods.

read the caption

Figure 5: Synthetic min-max problem: additional plots for the convergence comparison with respect to runtime.

🔼 The figure compares the performance of the parameter-free method (Option II) for different initializations of λ0 in solving the min-max problem in Section 7 with dimension d=102. The results show the robustness of the method to the choice of initial λ0, with consistent performance across different values of λ0. A heuristic strategy is also used for initialization, and it is shown to be competitive and works well across different settings.

read the caption

Figure 6: Runtime comparison for the parameter-free method (Option (II)) for solving the min-max problem in Section 7 (d = 102) with different initialization of λ0.

Full paper#