↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

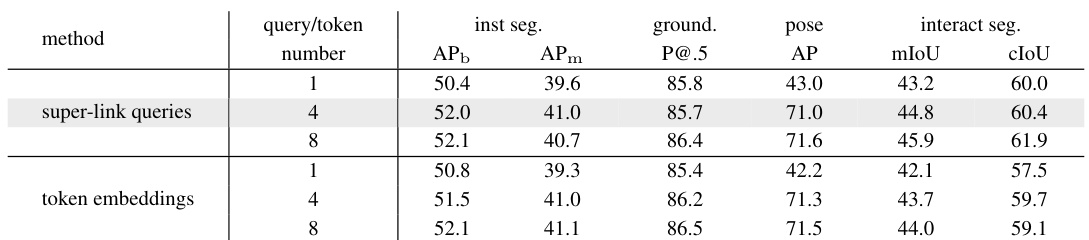

Current multimodal large language models (MLLMs) are often limited in their application scope, producing only text outputs and struggling with diverse visual tasks. The limitations arise from inefficient information transmission between the core MLLM and task-specific decoders, leading to training conflicts and suboptimal performance across multiple domains. This paper addresses these issues by introducing a new model and a novel information transmission method.

VisionLLM v2, introduced in this paper, overcomes these limitations with its end-to-end architecture and a new mechanism called “super link.” Super link enables flexible information transmission and gradient feedback between the core MLLM and multiple downstream decoders, addressing training conflicts effectively. The model’s performance is extensively evaluated on hundreds of public vision and vision-language tasks, showing that it achieves results comparable to task-specific models. The introduction of VisionLLM v2 thus represents a significant advancement in the generalization of MLLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents VisionLLM v2, a groundbreaking model that offers a new perspective on the generalization of multi-modal large language models (MLLMs). Its end-to-end design and ability to handle diverse visual tasks makes it highly relevant to current research trends in AI and opens up new avenues for future investigation. The detailed methodology and comprehensive evaluation presented provide a valuable resource for researchers seeking to advance MLLM capabilities.

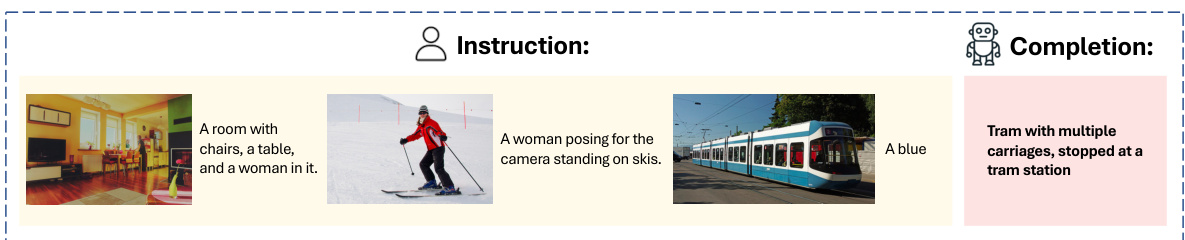

Visual Insights#

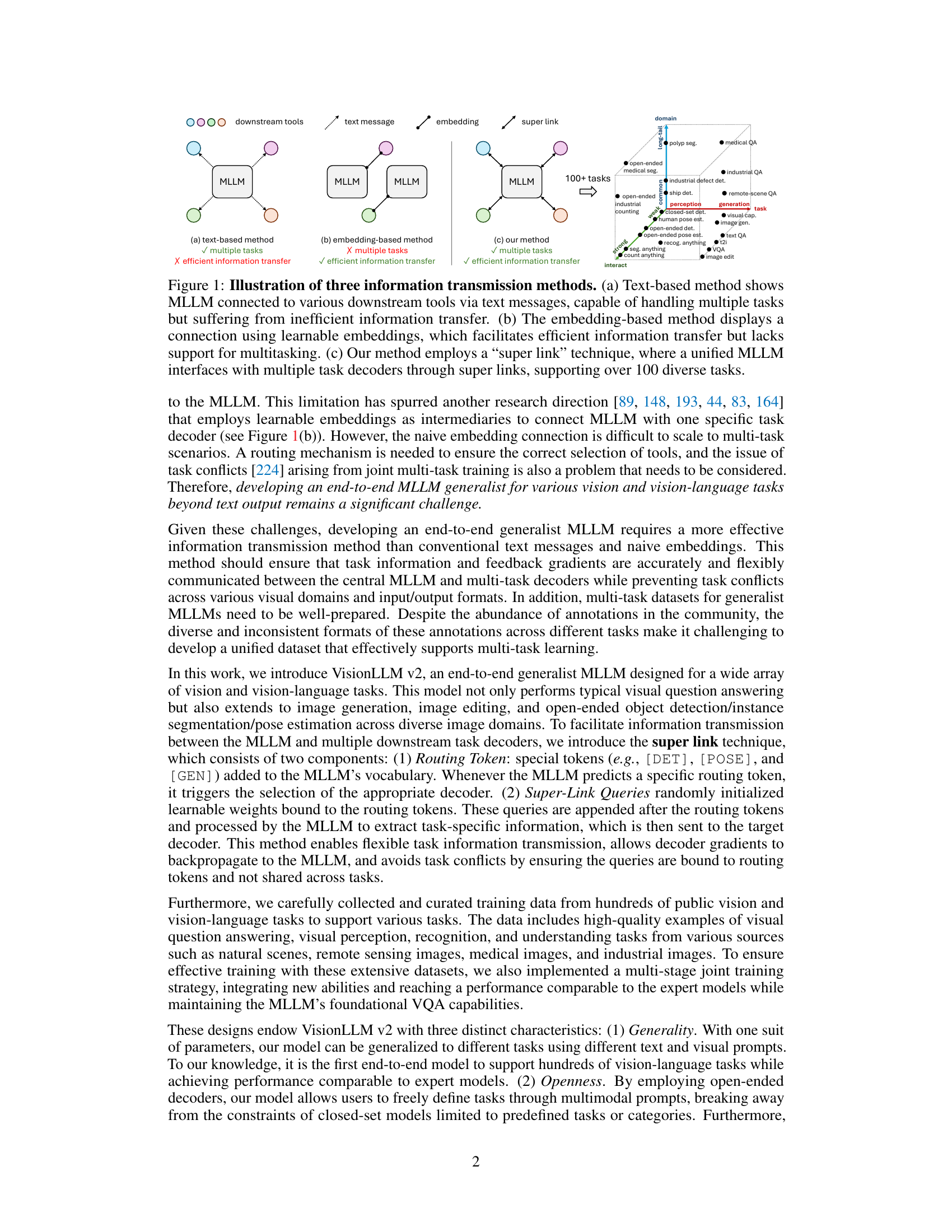

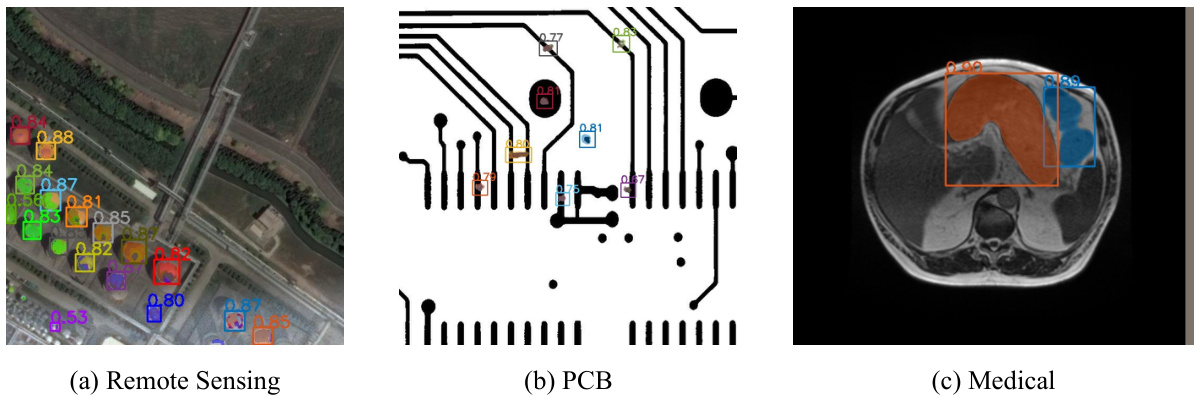

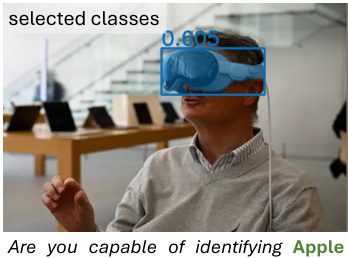

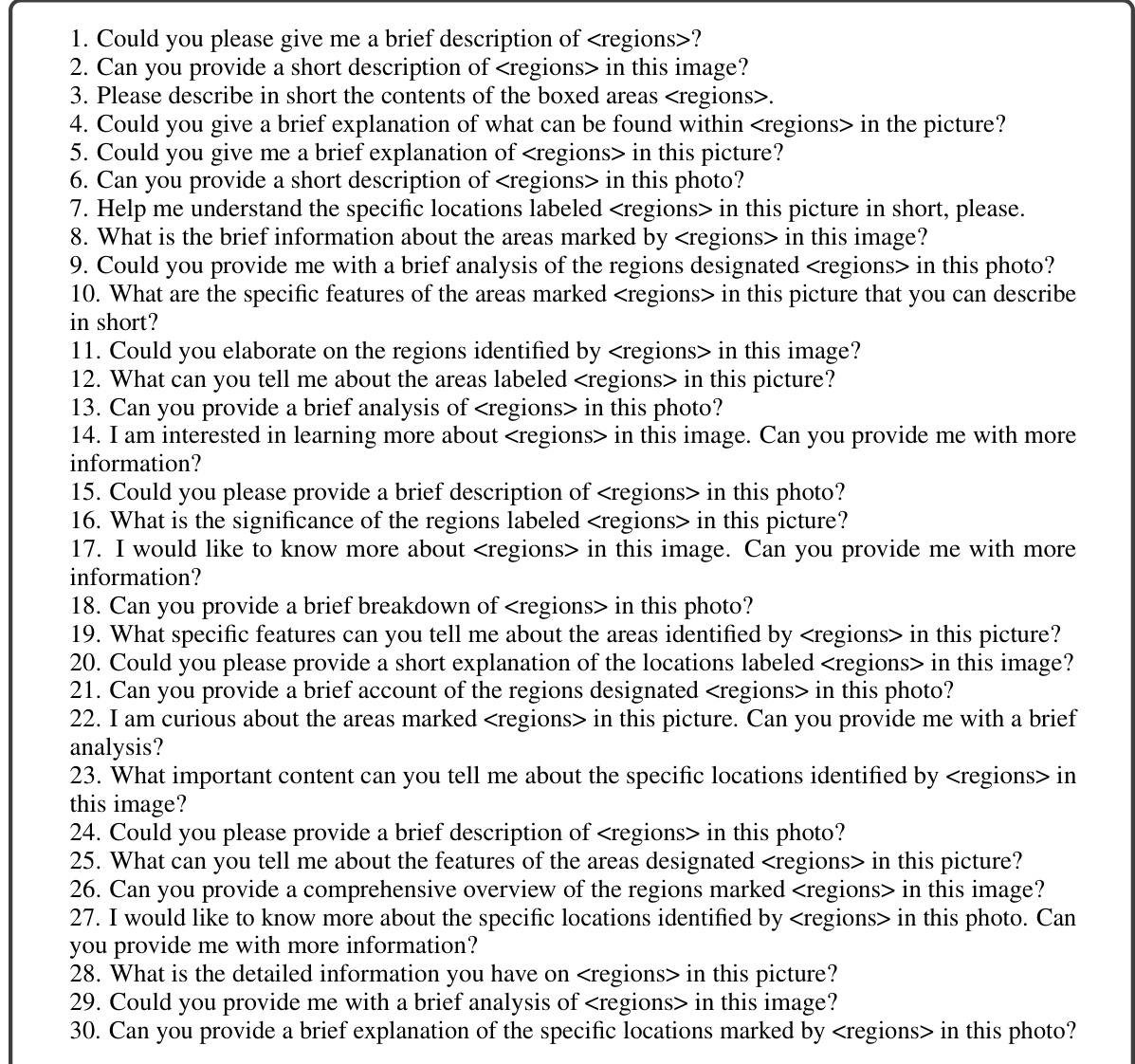

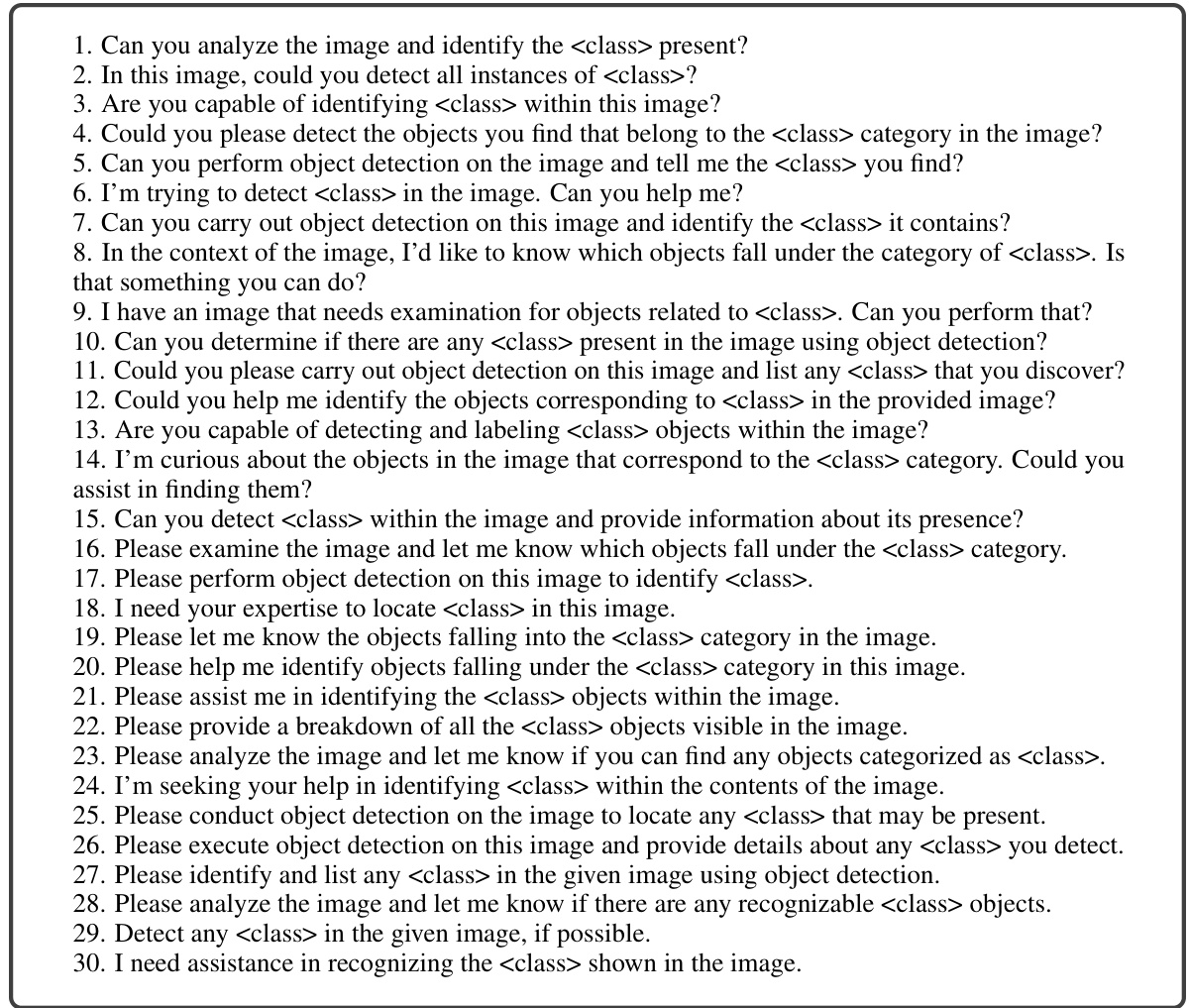

This figure illustrates three different approaches for information transmission between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. (a) shows a text-based method where the MLLM communicates through text messages. This is simple, but inefficient and lacks scalability for multiple tasks. (b) shows an embedding-based method, which improves efficiency via learnable embeddings but still lacks robust multi-tasking support. (c) Finally, the paper’s proposed ‘super link’ method is presented, enabling efficient information transfer and flexible integration with numerous (over 100) diverse tasks through a unified MLLM and multiple task-specific decoders.

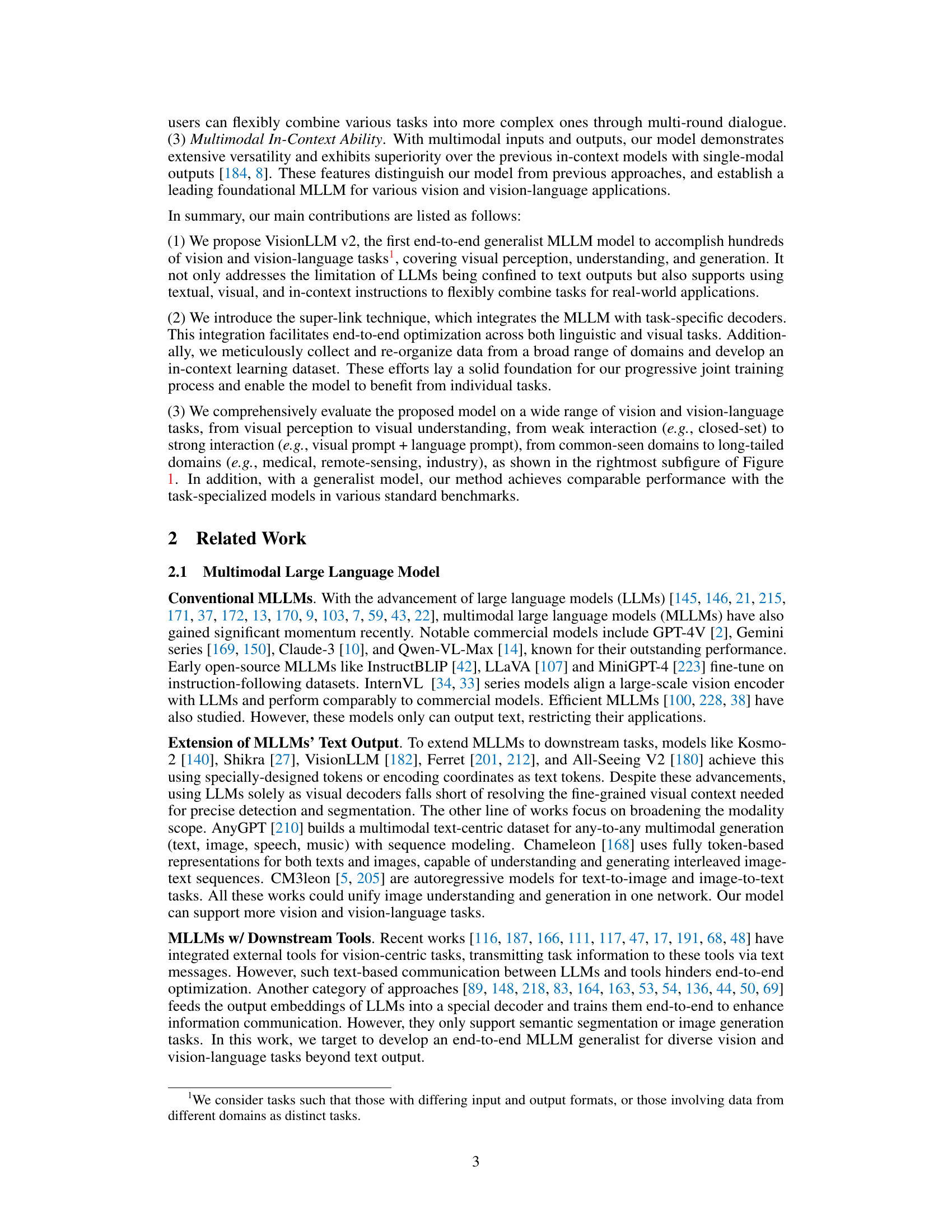

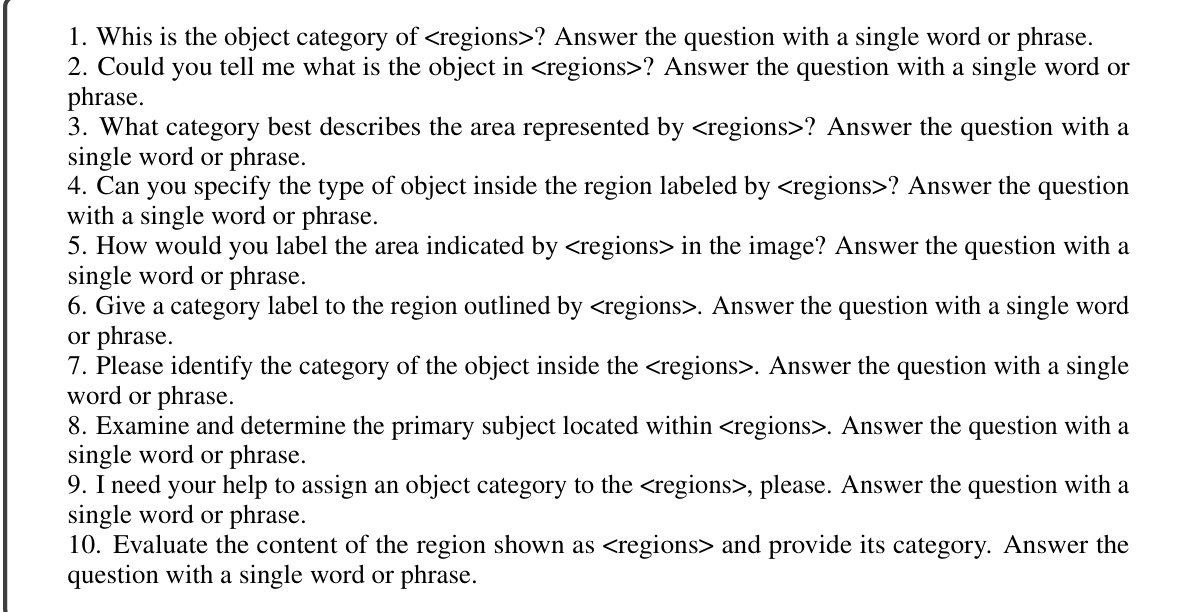

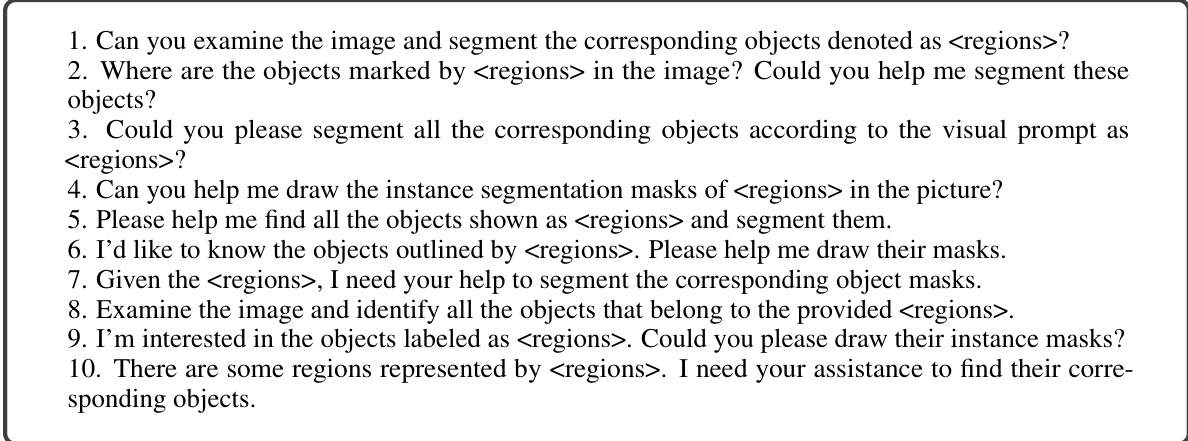

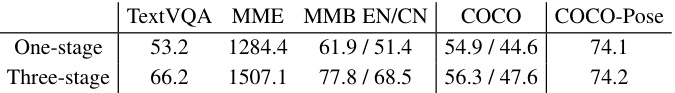

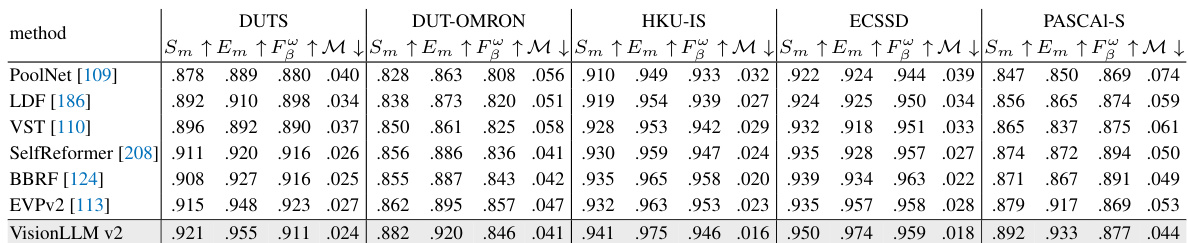

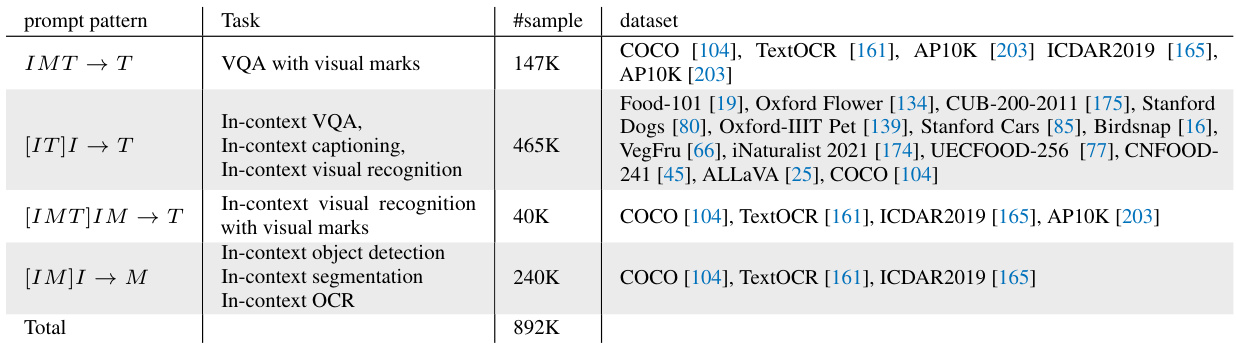

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SoTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. It breaks down the results across two types of datasets: academic-oriented datasets (focused on question answering and visual reasoning) and instruction-following datasets (assessing the model’s ability to follow instructions). The asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations for that dataset were visible to the model during its training, potentially influencing its performance. The table provides numerical scores for each model on various tasks within each dataset category.

In-depth insights#

VisionLLM v2 Overview#

VisionLLM v2 represents a significant advancement in multimodal large language models (MLLMs). Its end-to-end architecture unifies visual perception, understanding, and generation, unlike predecessors limited to text outputs. This enhanced scope broadens applications beyond conventional VQA to include object localization, pose estimation, image generation, and editing. A key innovation is the “super link” mechanism, enabling efficient information transmission and gradient feedback between the core MLLM and various task-specific decoders, thereby resolving training conflicts inherent in multi-tasking. The model’s ability to generalize across hundreds of tasks using a shared parameter set, facilitated by user prompts, is remarkable. This demonstrates impressive generalization capabilities and a new approach to MLLM design, offering a promising perspective on the future of multimodal AI.

Super Link Mechanism#

The proposed “Super Link Mechanism” appears to be a novel approach for efficient information transmission and gradient feedback in a multimodal large language model (MLLM). Instead of relying on less efficient text-based communication or the limitations of embedding-based methods for connecting the MLLM with task-specific decoders, this mechanism uses routing tokens to trigger decoder selection and learnable super-link queries to transfer task-specific information and gradients. This end-to-end architecture enhances the efficiency and flexibility of the system, allowing for seamless integration across diverse vision-language tasks. The mechanism seems particularly well-suited for handling open-ended tasks and avoids task conflicts common in multi-tasking scenarios. However, it’s worth noting that the effectiveness of this architecture hinges on the carefully designed and curated training data, as well as the appropriate selection of routing tokens and super-link query dimensions. Further evaluation and analysis are needed to fully assess the robustness and scalability of this approach across various tasks and domains. The method demonstrates a significant improvement over other strategies for multi-tasking with MLLMs.

Multi-Task Training#

Multi-task learning, while offering the potential for efficient model training and improved generalization, presents unique challenges. A naive approach of simply combining multiple tasks during training can lead to negative transfer, where learning in one task hinders performance in another. This is because different tasks may have conflicting gradients or require different optimal parameter settings. To mitigate this, various techniques are often employed, including task-specific decoders and curriculum learning. Task-specific decoders allow for tailored model outputs for individual tasks while preventing interference during training, ensuring efficient information transfer. Curriculum learning, on the other hand, focuses on carefully sequencing the introduction of tasks, starting with easier ones and gradually progressing to more difficult tasks. This helps alleviate the training instability often encountered in multi-task learning and promotes better overall performance. Additionally, regularization techniques play a crucial role in stabilizing the training process and improving the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Careful data curation and balancing across tasks is also essential to ensure that the model does not overemphasize any particular task and achieves optimal performance across all tasks.

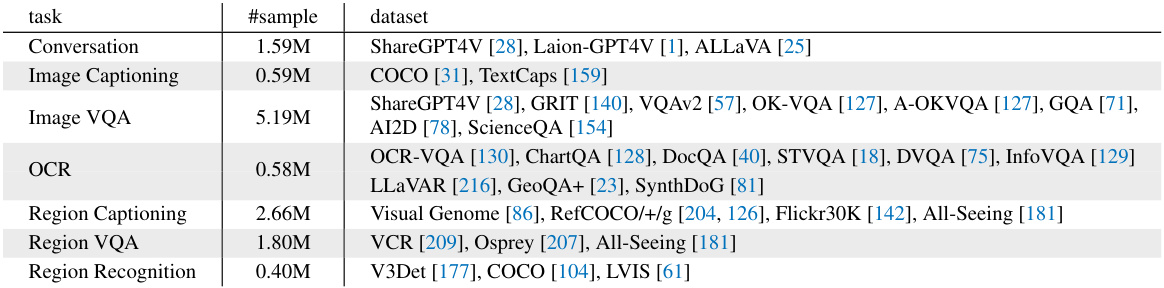

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section in a research paper is crucial for evaluating the model’s performance. It should present a comprehensive comparison against existing state-of-the-art models on standard benchmarks relevant to the paper’s focus. Quantitative metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, etc.) are essential and should be clearly presented, ideally with error bars or confidence intervals to show statistical significance. The choice of benchmarks should be justified, explaining why those specific datasets were selected and their relevance. Qualitative analysis can also offer valuable insights, providing concrete examples to support the quantitative results and illustrating the model’s behavior in challenging scenarios. A discussion of the limitations of the benchmark results is also crucial, acknowledging potential biases or shortcomings of the chosen benchmarks and how these might impact the overall performance assessment. This section shouldn’t simply report numbers but should provide a thoughtful interpretation, explaining any surprising or unexpected results and drawing meaningful conclusions based on the benchmark results which directly relates to the model’s strengths and weaknesses. Finally, it should clearly highlight the model’s advantages over the state-of-the-art in specific areas, providing substantial evidence for any claims of improvement.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the model’s capabilities to handle even more diverse visual tasks, such as complex scene understanding or video analysis, would be a significant step. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the training process is also crucial, perhaps through novel architectures or training techniques. Investigating the model’s robustness and limitations in various contexts, including handling noisy or incomplete data, is key to advancing its reliability. Further research should focus on the ethical implications and potential biases embedded within the model and its applications, especially considering its use in decision-making processes. Finally, developing methods for better interpretability and explainability is essential for building user trust and ensuring responsible deployment. This will allow for a deeper understanding of the model’s internal workings and enable detection of potential biases or unexpected behaviour.

More visual insights#

More on figures

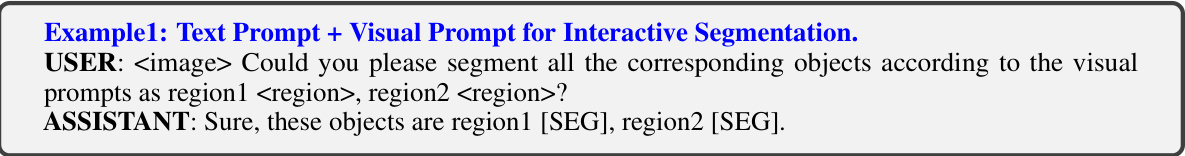

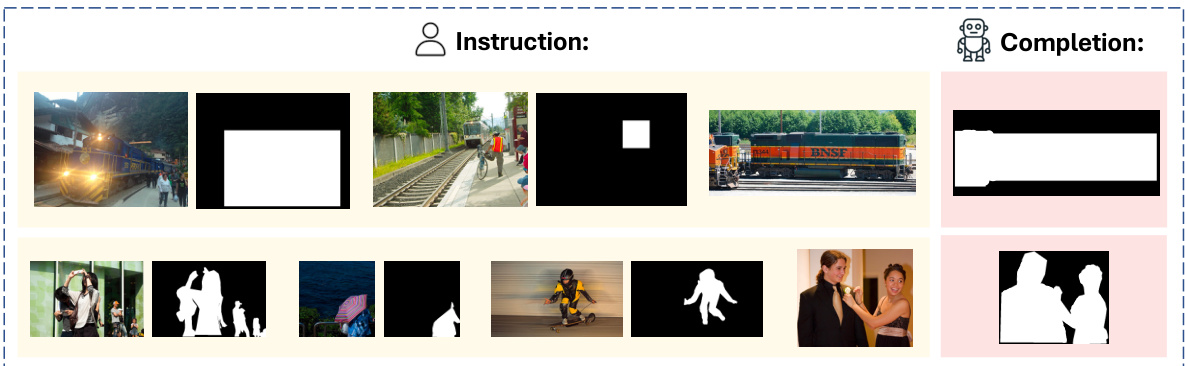

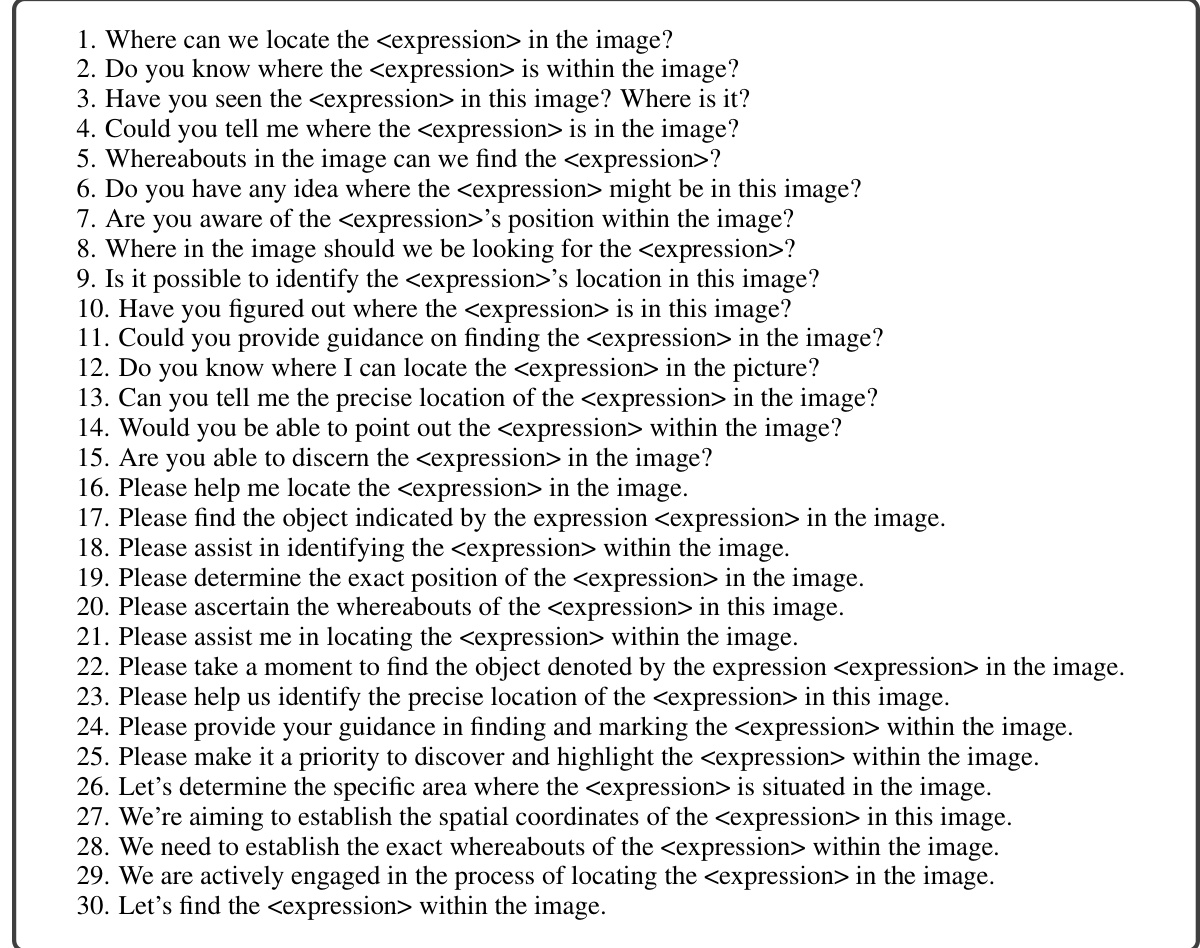

This figure presents the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model takes image and text/visual prompts as inputs. A central large language model (LLM) processes these inputs and generates text outputs. Importantly, the LLM can also produce special routing tokens ([DET], [SEG], [GEN]) that trigger the selection of specific downstream decoders (for detection, segmentation, generation, etc.). Super-link queries are appended after these routing tokens, providing task-specific information to the decoders, allowing for end-to-end training across diverse visual tasks. The detailed connection between the LLM and task-specific decoders is further explained in Figure A13.

This figure compares three different methods for information transmission between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools. The text-based method uses text messages which is inefficient and limits multitasking. The embedding-based method uses learnable embeddings for efficient transfer but still struggles with multiple tasks. The proposed ‘super link’ method, shown in (c), uses a unified MLLM with super links to connect to multiple task-specific decoders, enabling efficient information transfer and supporting over 100 diverse tasks.

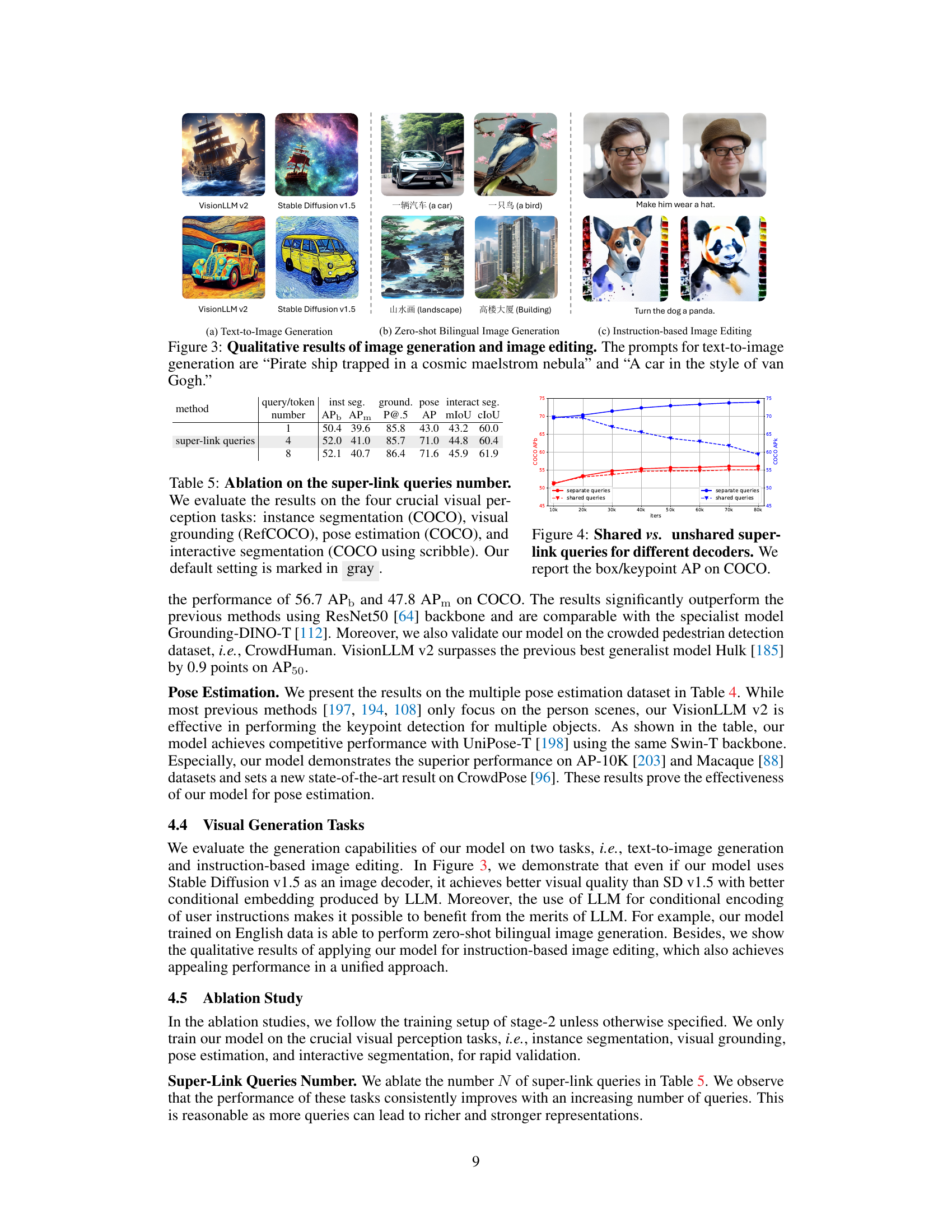

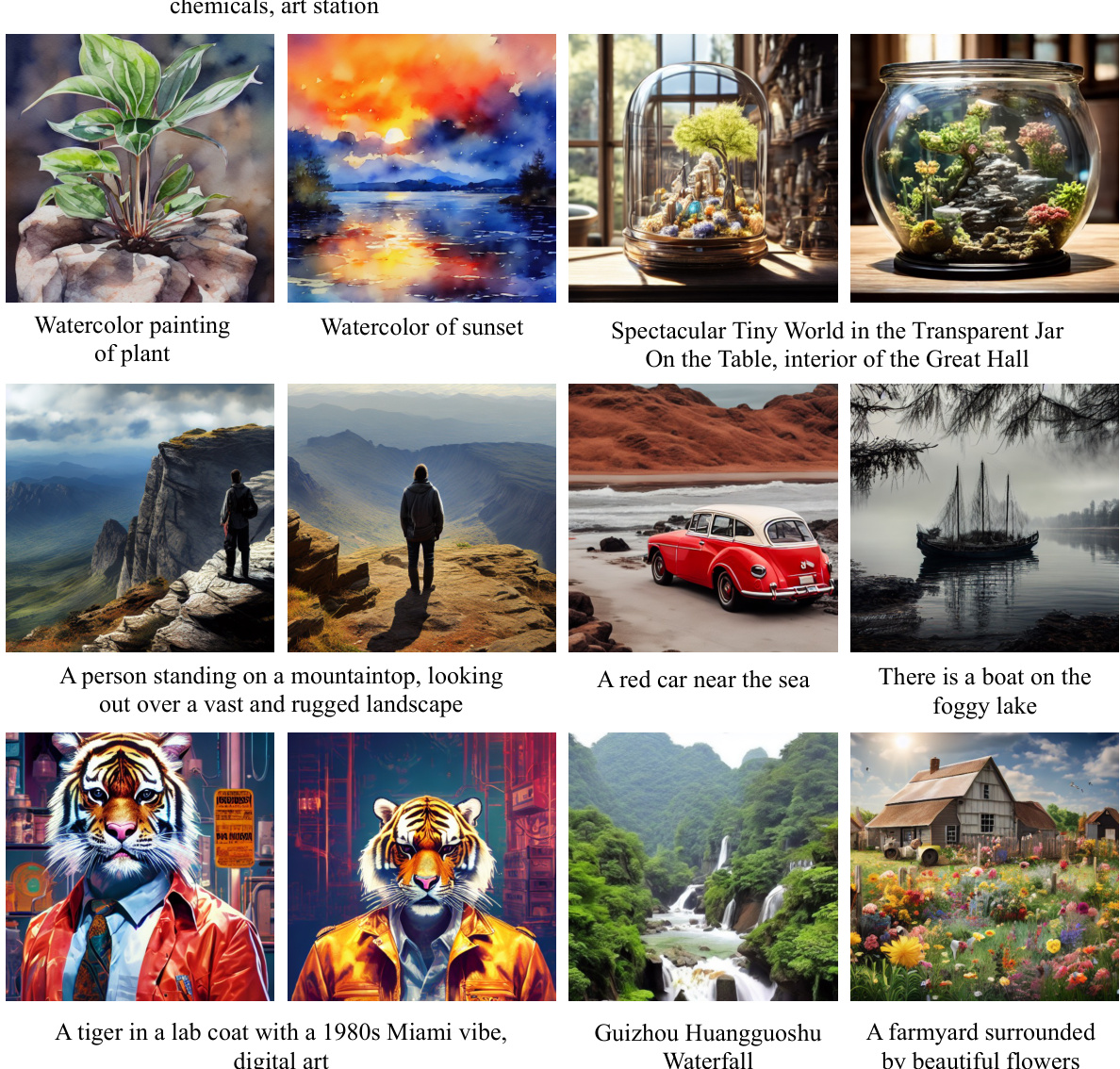

This figure displays qualitative results of VisionLLM v2’s image generation and editing capabilities. It shows three example outputs: (a) Text-to-image generation, showcasing two different images generated from two different text prompts (‘Pirate ship trapped in a cosmic maelstrom nebula’ and ‘A car in the style of van Gogh’), and a comparison with results from Stable Diffusion v1.5; (b) Zero-shot bilingual image generation, demonstrating the model’s ability to generate images from text prompts in different languages (Chinese and English); and (c) instruction-based image editing, illustrating how instructions can modify existing images (e.g., adding a hat to a person’s head, turning a dog into a panda). The figure highlights the model’s ability to generate high-quality, diverse images while following both textual and visual prompts.

This figure shows the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It illustrates how the model processes image and text/visual prompts, using a large language model (LLM) as the core component to generate text and trigger task-specific decoders via routing tokens and super-link queries. The super-link queries are additional learned embeddings appended to the routing tokens to efficiently transfer information between the LLM and the various decoders, enabling VisionLLM v2 to handle a wide range of visual tasks.

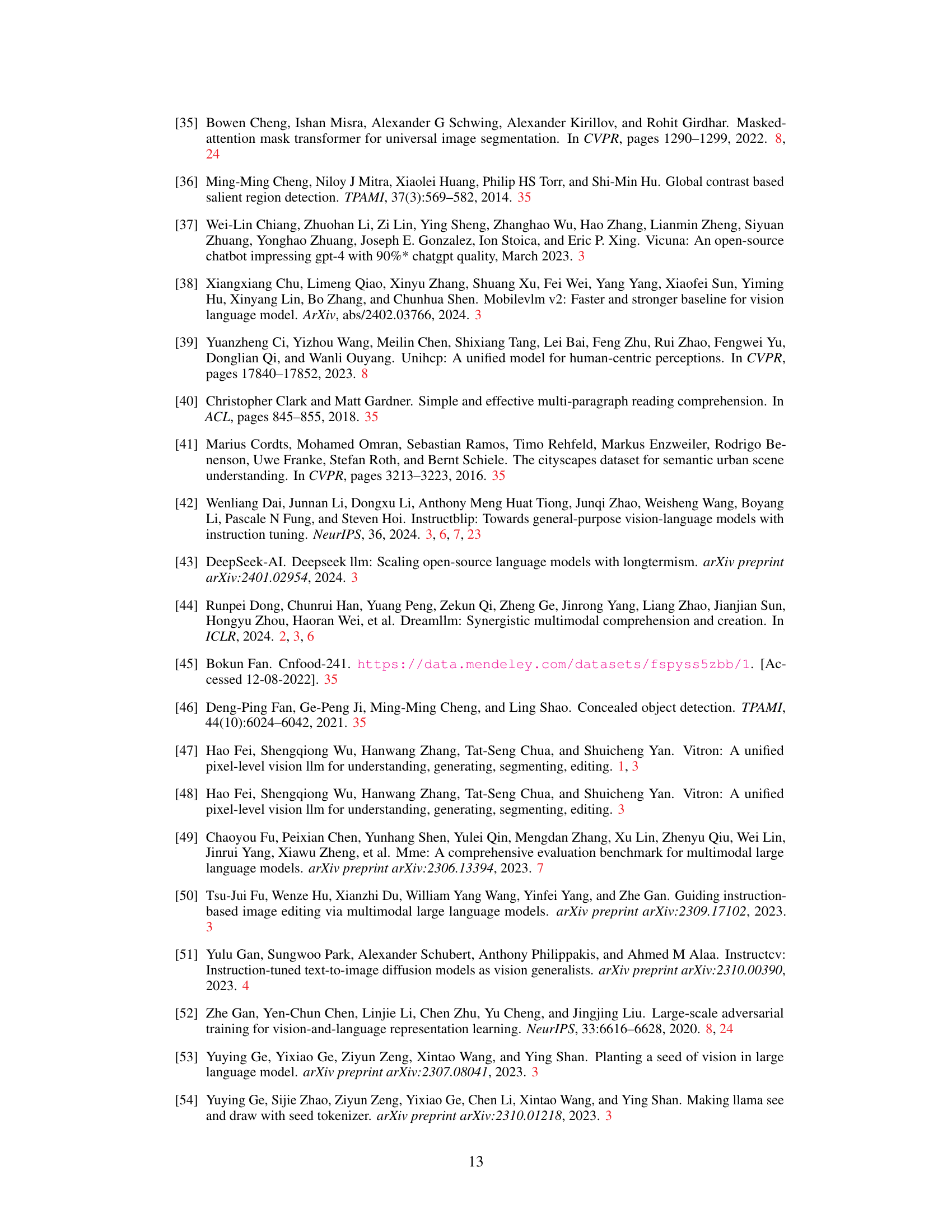

This figure compares the performance of using shared versus separate super-link queries for different downstream decoders in the VisionLLM v2 model. The experiment is conducted on the COCO dataset, measuring Average Precision (AP) for both bounding boxes (box AP) and keypoints (keypoint AP). The results show that using separate queries for each decoder leads to better performance, likely because it avoids conflicts between tasks and allows for more specialized information transfer. Using shared queries results in decreased performance, indicating that the naive method of sharing embeddings is not sufficient for effective multi-task learning.

This figure presents the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model processes image and text/visual prompts using a large language model (LLM) as the core component. The LLM interacts with various task-specific decoders via a mechanism called ‘super link.’ This enables the model to handle numerous visual tasks and generate various outputs beyond text, such as image generation, object detection, etc. The super link consists of routing tokens that signal which decoder to use and super-link queries that transmit relevant task information to the decoder. The figure highlights the model’s capacity to unify visual perception, understanding, and generation in an end-to-end fashion.

This figure shows the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. The model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. A large language model (LLM) processes these inputs and generates text outputs. Importantly, the LLM can also produce special routing tokens that trigger the selection of different task-specific decoders (e.g., for detection, segmentation, generation). Super-link queries are automatically appended to the routing tokens, further processed by the LLM, and act as a bridge between the LLM and the appropriate decoder, enabling efficient information transfer for a variety of visual tasks. The figure highlights the end-to-end design and multimodal capabilities of the model.

The figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model takes image and text/visual prompts as input, processes them using a large language model (LLM), and outputs text or triggers task-specific decoders via special routing tokens and super-link queries. The super-link queries act as a bridge between the LLM and the decoders, enabling the model to handle a wide variety of visual tasks. The figure highlights the end-to-end nature of the model and its ability to adapt to different tasks through flexible information transmission.

This figure shows the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It takes images and text/visual prompts as input. A large language model (LLM) processes the input and generates text responses. Crucially, the LLM can output special routing tokens which trigger the selection of different task-specific decoders (e.g., for object detection, segmentation, image generation). Super-link queries are appended to the routing tokens and further processed by the LLM to transmit task-specific information to the decoders, enabling end-to-end training across multiple tasks. This architecture allows the model to handle a wide range of vision and vision-language tasks.

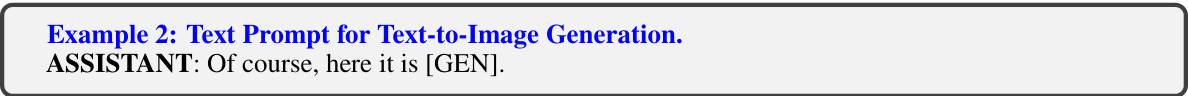

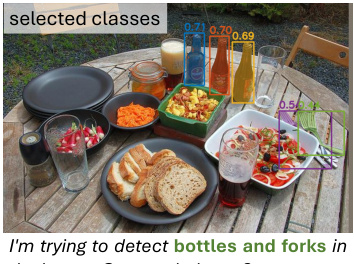

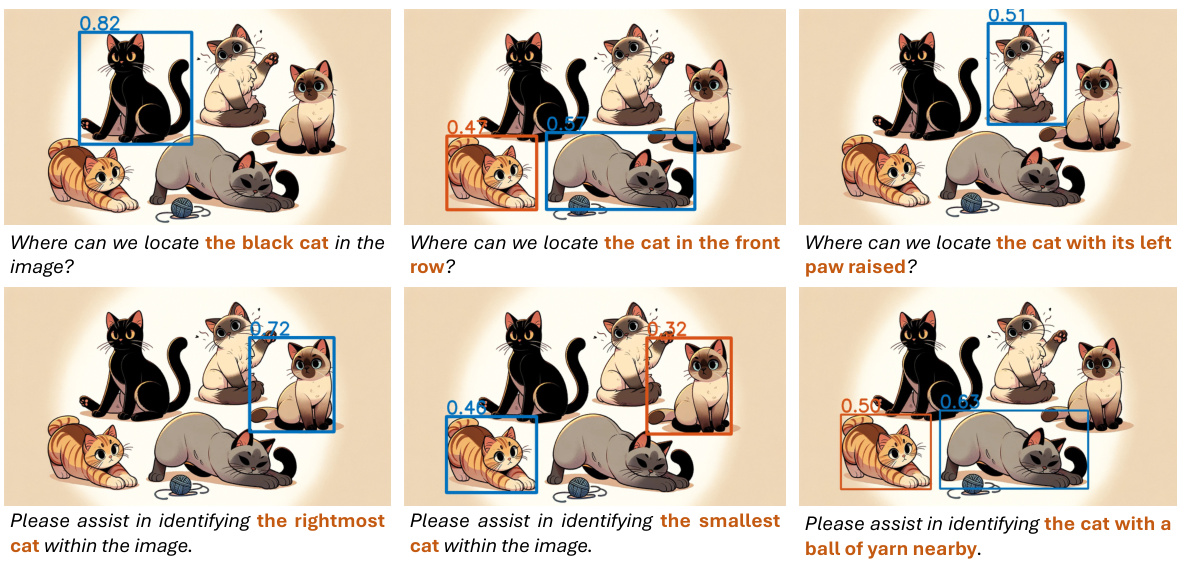

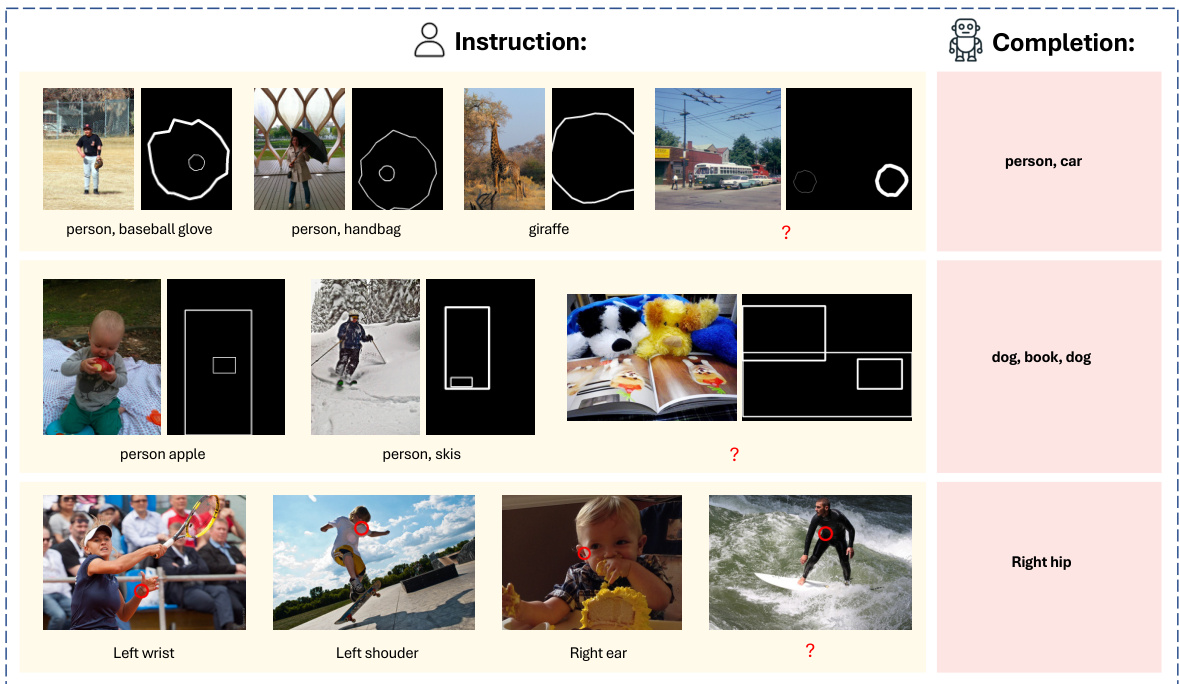

This figure shows several examples of object detection and instance segmentation results on various images. The key takeaway is that the VisionLLM v2 model can handle various scenarios, including crowded scenes and images with many objects. Importantly, it demonstrates the flexibility to detect only specific user-requested object categories (e.g., only ‘bottles’ and ‘forks’) and also identifies novel classes not explicitly seen during training.

This figure shows three examples of VisionLLM v2’s image generation and editing capabilities. The top row demonstrates text-to-image generation with two different prompts. The first generates a pirate ship in a cosmic setting, and the second generates a car in the style of Van Gogh, illustrating the model’s ability to understand and generate images based on complex descriptions and artistic styles. The bottom row shows examples of instruction-based image editing. A user prompt instructs the model to make various edits to existing images, such as changing an image’s color palette and adding or removing objects. This showcases VisionLLM v2’s capability to perform complex image manipulations in response to natural language commands.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model processes image and text/visual prompts using a large language model (LLM) as the core. The LLM generates text responses and can output special routing tokens to select appropriate downstream decoders (e.g., for object detection, segmentation, image generation). Super-link queries are automatically added, enabling flexible information transmission and gradient feedback between the LLM and decoders. This unified architecture allows VisionLLM v2 to handle hundreds of diverse visual tasks.

The figure shows the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It takes image and text/visual prompts as input and uses a central Large Language Model (LLM) to process instructions and generate responses. The LLM can output special routing tokens to indicate which task-specific decoder should be used. Super-link queries are added to routing tokens, processed by the LLM, and used to efficiently transfer information between the LLM and decoders, supporting hundreds of visual tasks. The detailed architecture of the connection between the LLM and task-specific decoders is shown in Figure A13.

This figure displays examples of the VisionLLM v2 model’s image generation and editing capabilities. The top row shows examples of text-to-image generation, where the model created images based on textual descriptions such as ‘Pirate ship trapped in a cosmic maelstrom nebula’ and ‘A car in the style of van Gogh.’ The bottom row showcases instruction-based image editing, demonstrating the model’s ability to modify existing images according to user instructions.

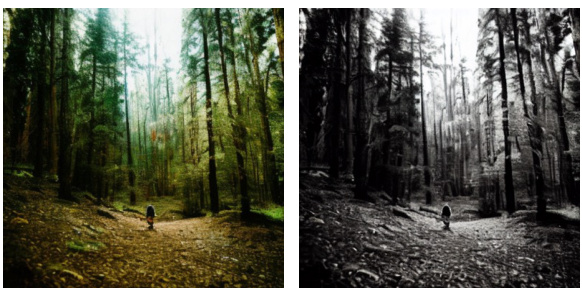

The figure shows the results of pose estimation on various images. The model successfully detects keypoints on different subjects, including humans and animals. Importantly, it demonstrates that the model can be prompted to focus on specific categories of subjects (e.g., only detecting humans) and even select specific keypoints, rather than all possible keypoints, for detection. This highlights the model’s flexibility and its ability to adapt to user-defined constraints.

This figure shows three examples of VisionLLM v2’s capabilities in image generation and editing. The top row demonstrates text-to-image generation, where natural language prompts are used to create images. The two examples are a pirate ship in a nebula and a car in the style of Van Gogh’s paintings. The bottom row displays examples of image editing, where instructions specify changes to be made to an existing image. The edits include turning a dog into a panda and altering the style of another image.

This figure shows examples of pose estimation results obtained using VisionLLM v2. The model demonstrates its ability to perform pose estimation on both human and animal images. Notably, the model can be instructed to either detect keypoints for specific categories (e.g., humans or animals only) or to only focus on individual keypoints within a specific category. This highlights VisionLLM v2’s flexibility and capacity to adapt to various user-specified instructions.

This figure shows several examples of pose estimation results obtained using VisionLLM v2. It highlights the model’s ability to detect keypoints not only in humans but also animals. Importantly, it demonstrates the model’s flexibility in two ways: First, the user can specify the type of object (human or animal) for which they want to obtain pose information. Second, users can specify which keypoints they wish to see (all keypoints or specific keypoints). Each example within the figure illustrates different situations to demonstrate the generality of the approach.

The figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. A central Large Language Model (LLM) processes these inputs and generates textual responses. Importantly, the LLM can generate special tokens to trigger task-specific decoders (e.g., for detection, segmentation, generation). Super-link queries, appended after the routing token embeddings, act as a bridge connecting the LLM to these specialized decoders. This design allows the single model to handle a wide variety of visual tasks.

This figure shows four examples of image generation and editing produced by the VisionLLM v2 model. The top row displays examples of text-to-image generation, where different prompts are given to the model to generate unique images. The bottom row shows examples of instruction-based image editing, where instructions are used to modify existing images. The images demonstrate the model’s ability to generate high-quality, creative images and to perform a variety of image editing tasks.

This figure displays qualitative results of the VisionLLM v2 model on image generation and editing tasks. The left column shows the results of text-to-image generation, where the model created images from textual descriptions (‘Pirate ship trapped in a cosmic maelstrom nebula’ and ‘A car in the style of van Gogh’). The right column demonstrates the model’s image editing capabilities, modifying existing images based on given instructions. The results showcase the model’s ability to generate and manipulate images based on varied and complex instructions.

This figure shows qualitative results of VisionLLM v2 on image generation and image editing tasks. The top row demonstrates text-to-image generation, showcasing the model’s ability to create images from textual descriptions that include stylistic elements. The bottom row showcases instruction-based image editing, highlighting the model’s ability to modify existing images according to specific instructions such as changing an object or applying a style. The examples illustrate VisionLLM v2’s capability to perform both image generation and editing tasks with high fidelity and stylistic consistency.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. A central Large Language Model (LLM) processes these inputs and generates text outputs. Crucially, the LLM can also output special routing tokens that trigger the use of different task-specific decoders (e.g., for object detection, image generation). Super-link queries are appended to the routing tokens and are processed by the LLM to provide task-specific information to the appropriate decoder. This allows VisionLLM v2 to handle hundreds of visual tasks with a single unified architecture.

This figure shows qualitative results of VisionLLM v2 on image generation and image editing tasks. The left column shows the original image or text prompt, while the right column displays the results generated by VisionLLM v2. The top row demonstrates text-to-image generation, showcasing the model’s ability to create images from textual descriptions, such as a pirate ship in a nebula or a car in the style of Van Gogh. The bottom row illustrates the instruction-based image editing capabilities of the model. It highlights VisionLLM v2’s ability to modify an existing image according to various instructions.

This figure shows qualitative results of VisionLLM v2 on image generation and image editing tasks. The top row displays examples of text-to-image generation, showcasing the model’s ability to generate images from textual descriptions. The bottom row shows instruction-based image editing, demonstrating the model’s capacity to manipulate existing images according to user instructions. The figure highlights the model’s versatility in handling various visual tasks and different artistic styles.

The figure shows the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. The model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. A large language model (LLM) processes these inputs and generates text-based responses. Crucially, the LLM can also output special routing tokens, triggering the use of specific task-oriented decoders (e.g., for detection, segmentation, generation). Super-link queries are appended to these tokens, providing task-specific information to the appropriate decoder. This design allows VisionLLM v2 to handle a wide variety of visual tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how image and text/visual prompts are processed by an image encoder and text tokenizer respectively. These are fed to a Large Language Model (LLM), which generates responses and can also output special routing tokens. These tokens trigger the selection of appropriate task-specific decoders via ‘super links’, allowing for flexible task handling and efficient information transmission. The super links consist of Routing Tokens and Super-Link Queries. The detailed decoder connections are shown in Figure A13. The system as a whole allows for the handling of hundreds of visual tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model processes image and text/visual prompts using a large language model (LLM) as the central component. The LLM generates text responses and can also output special routing tokens to select appropriate task-specific decoders. Super-link queries are added to the routing tokens to enable efficient information transfer between the LLM and the decoders, ultimately enabling the model to handle many visual tasks. Figure A13 provides further detail on the connections between the LLM and the various decoders.

The figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model processes image and text/visual prompts using a central Large Language Model (LLM). The LLM generates text responses and can also produce special routing tokens that trigger the selection of task-specific decoders. Super-link queries are appended to the routing tokens and processed by the LLM to transmit information to the appropriate decoder. This architecture allows the model to handle a wide range of visual tasks.

The figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model processes image and text/visual prompts. The core component is a large language model (LLM) that processes the inputs and generates text outputs. Crucially, the LLM can generate special tokens (e.g., [DET]) that trigger task-specific decoders. These decoders handle various vision tasks like object detection or image generation. Super-link queries are appended to routing tokens, acting as a bridge between the LLM and the decoders, enabling efficient information transfer.

This figure presents the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. The core component, a large language model (LLM), processes this input to generate textual responses. Importantly, the LLM can generate special routing tokens (like [DET]), which trigger the selection of a specific task decoder (for tasks like detection or segmentation). The super-link queries, added after routing tokens, enhance information transfer between the LLM and these specialized decoders. This design allows the single model to handle a large number of visual tasks.

The figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how image and text/visual prompts are processed. A central Large Language Model (LLM) interprets user instructions and generates responses. Crucially, the LLM can output special routing tokens ([DET], etc.), triggering the selection of task-specific decoders via ‘super links’. These super links use learnable queries that are appended after the routing tokens and processed by the LLM to effectively transmit information between the LLM and the task decoders, allowing support for diverse visual tasks. The detailed decoder connections are described in a supplementary figure.

This figure compares three different approaches for information transmission between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. The first approach uses text messages, which is simple but inefficient. The second approach uses learnable embeddings, which is more efficient but doesn’t scale well to multiple tasks. The third approach, proposed by the authors, uses a ‘super link’ mechanism, which combines the efficiency of embeddings with the ability to handle multiple tasks through unified interfaces.

This figure compares three different approaches for transmitting information between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. (a) shows a text-based method, where the MLLM communicates with tools via text messages. This approach is simple but suffers from inefficient information transfer. (b) illustrates an embedding-based method, using learnable embeddings to connect the MLLM to task-specific decoders. While efficient, this method doesn’t handle multiple tasks well. (c) presents the proposed ‘super link’ method, a unified MLLM using super links to connect with multiple task decoders, enabling efficient information transfer and multitasking.

This figure illustrates three different approaches for transmitting information between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. (a) shows a traditional text-based method, where the MLLM communicates via text messages, which is slow and inefficient for complex tasks. (b) demonstrates an embedding-based approach that improves efficiency but still struggles with multiple tasks. (c) presents the authors’ proposed ‘super link’ method, which uses a unified MLLM and multiple task-specific decoders connected by super links, offering both efficiency and support for a large number of diverse tasks. This highlights the key advantage of the proposed approach.

This figure illustrates three different approaches for information transmission between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. (a) shows a text-based approach, where the MLLM communicates with tools via text messages. This is simple but inefficient. (b) shows an embedding-based approach, using learnable embeddings for communication, which is efficient but not suitable for multiple tasks. (c) presents the authors’ proposed ‘super link’ method, a unified MLLM connected to multiple decoders via super links for efficient and flexible information transfer across numerous tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. The model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. A central Large Language Model (LLM) processes these inputs and generates text outputs. Importantly, the LLM can output special routing tokens which trigger the use of specific task decoders (e.g., for object detection, pose estimation, image generation). Super-link queries are appended to the routing tokens, acting as a bridge between the LLM and these decoders, enabling efficient information transfer and facilitating the handling of numerous visual tasks.

This figure compares three different approaches for information transmission between a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. The text-based method (a) uses text messages, which is inefficient for complex information and lacks multi-tasking support. The embedding-based method (b) employs learnable embeddings, which is efficient for transferring information but still lacks multi-tasking support. The proposed ‘super link’ method (c) uses a unified MLLM with multiple task-specific decoders connected via super links, efficiently handling over 100 tasks.

This figure illustrates three different approaches for information transmission between a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. The first approach (a) uses text messages, which are inefficient and hinder efficient information transfer. The second approach (b) leverages learnable embeddings, resulting in more efficient information transfer, but it still does not fully support multiple tasks effectively. The authors’ proposed method (c) uses a ‘super link’ approach to achieve both efficiency in information transfer and the capability to effectively manage over 100 diverse tasks by connecting the unified MLLM with multiple task-specific decoders.

This figure shows the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It details how the model processes image and text/visual prompts. The core is a large language model (LLM) that generates text responses. Importantly, the LLM can output special routing tokens that trigger the selection of specific downstream decoders (e.g., for object detection or image generation). These decoders are connected to the LLM via ‘super links’, which involve task-specific queries automatically appended to the routing token embedding. This design enables efficient information transmission and gradient backpropagation, allowing the model to handle a wide array of vision and vision-language tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. It shows how the model takes image and text/visual prompts as input, processes them using a Large Language Model (LLM), and outputs text responses or triggers task-specific decoders via routing tokens and super-link queries. The super-link mechanism allows flexible information transfer and gradient feedback between the LLM and the decoders for efficient multi-tasking. The figure highlights the model’s ability to handle hundreds of visual tasks through a unified framework.

This figure compares three different methods of information transmission between a multimodal large language model (MLLM) and downstream tools or decoders. Method (a) uses text messages, which are inefficient for complex information. Method (b) uses embeddings for efficient transfer but doesn’t handle multiple tasks well. Method (c), the authors’ proposed approach, uses a ‘super link’ to connect the MLLM to multiple task-specific decoders efficiently and supports over 100 different tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of VisionLLM v2, a multimodal large language model. The model takes image and text/visual prompts as input. A large language model (LLM) processes the input and generates text responses. Importantly, the LLM can output special routing tokens (e.g., [DET]) that trigger the use of specific task decoders (e.g., for object detection, segmentation, generation) connected via ‘super links’. These super links use learnable queries, appended after routing tokens, to efficiently transfer information and gradients between the LLM and the decoders, enabling efficient multi-tasking. The figure highlights the end-to-end nature of VisionLLM v2, capable of handling hundreds of vision-language tasks.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 and other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on a range of multimodal dialogue benchmarks. It shows performance across both academic-oriented datasets (requiring visual question answering and reasoning) and instruction-following datasets (measuring the model’s ability to complete various tasks given instructions). The asterisk indicates when models had access to training annotations for a given dataset.

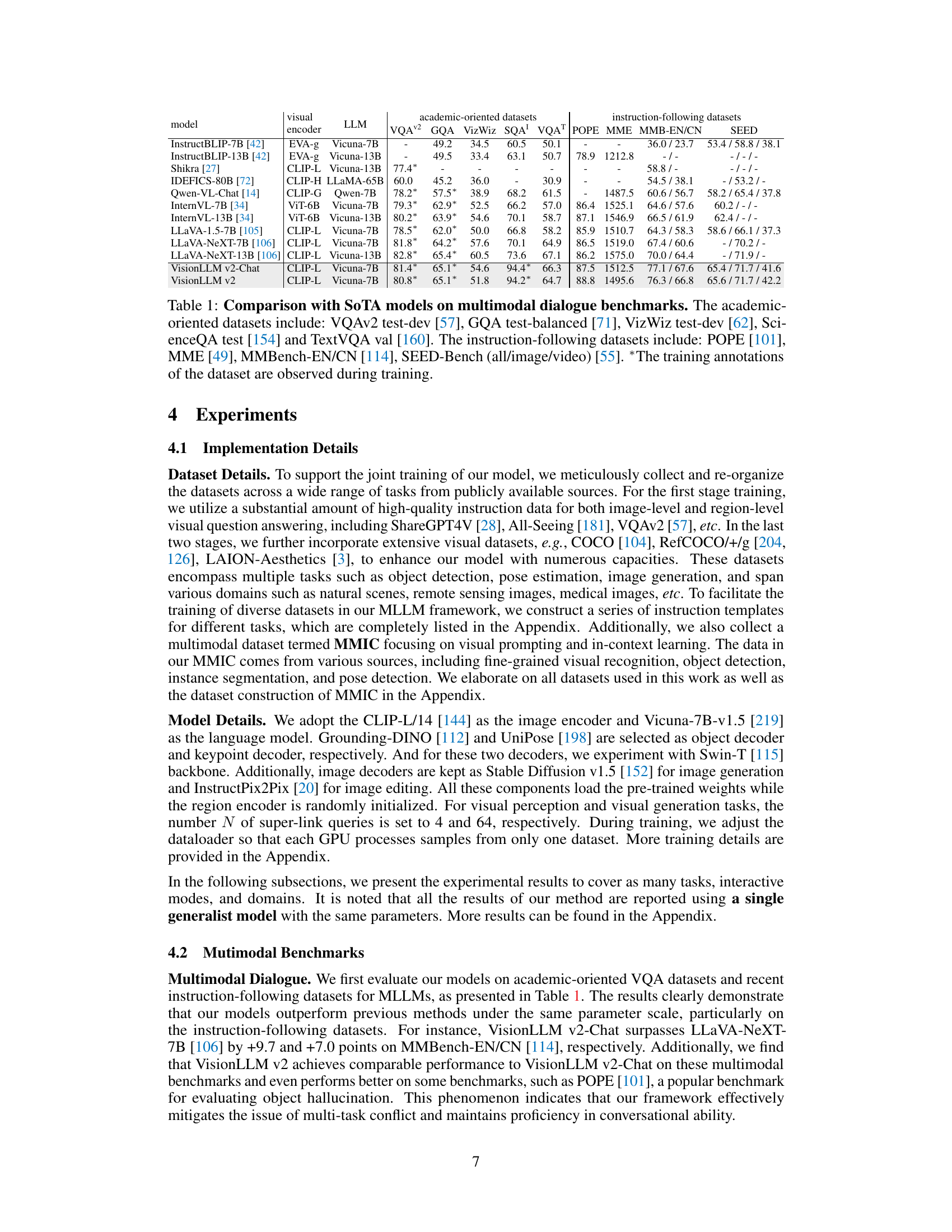

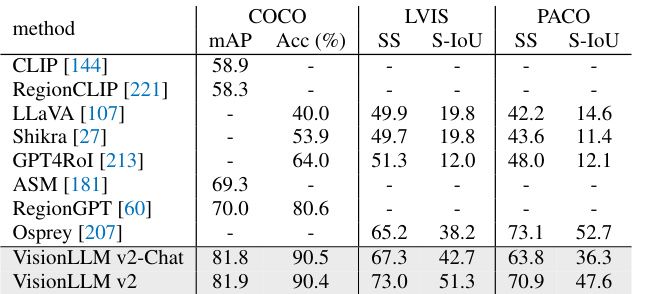

This table presents a comparison of the VisionLLM v2 model’s performance against other state-of-the-art models on two tasks: region recognition and visual commonsense reasoning. Region recognition evaluates the model’s ability to correctly identify objects within a given region of an image. Visual commonsense reasoning assesses the model’s capacity for complex reasoning and understanding of visual scenes, requiring it to select both the correct answer and rationale for a given question about an image. The table provides multiple metrics for both tasks, indicating the model’s performance across different datasets and conditions.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. These benchmarks are categorized into academic-oriented datasets (focused on visual question answering) and instruction-following datasets (testing the model’s ability to follow instructions). The table shows various metrics for each dataset, allowing for a comprehensive comparison of the models’ abilities across different types of multimodal tasks. The asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations for the dataset were accessible during training.

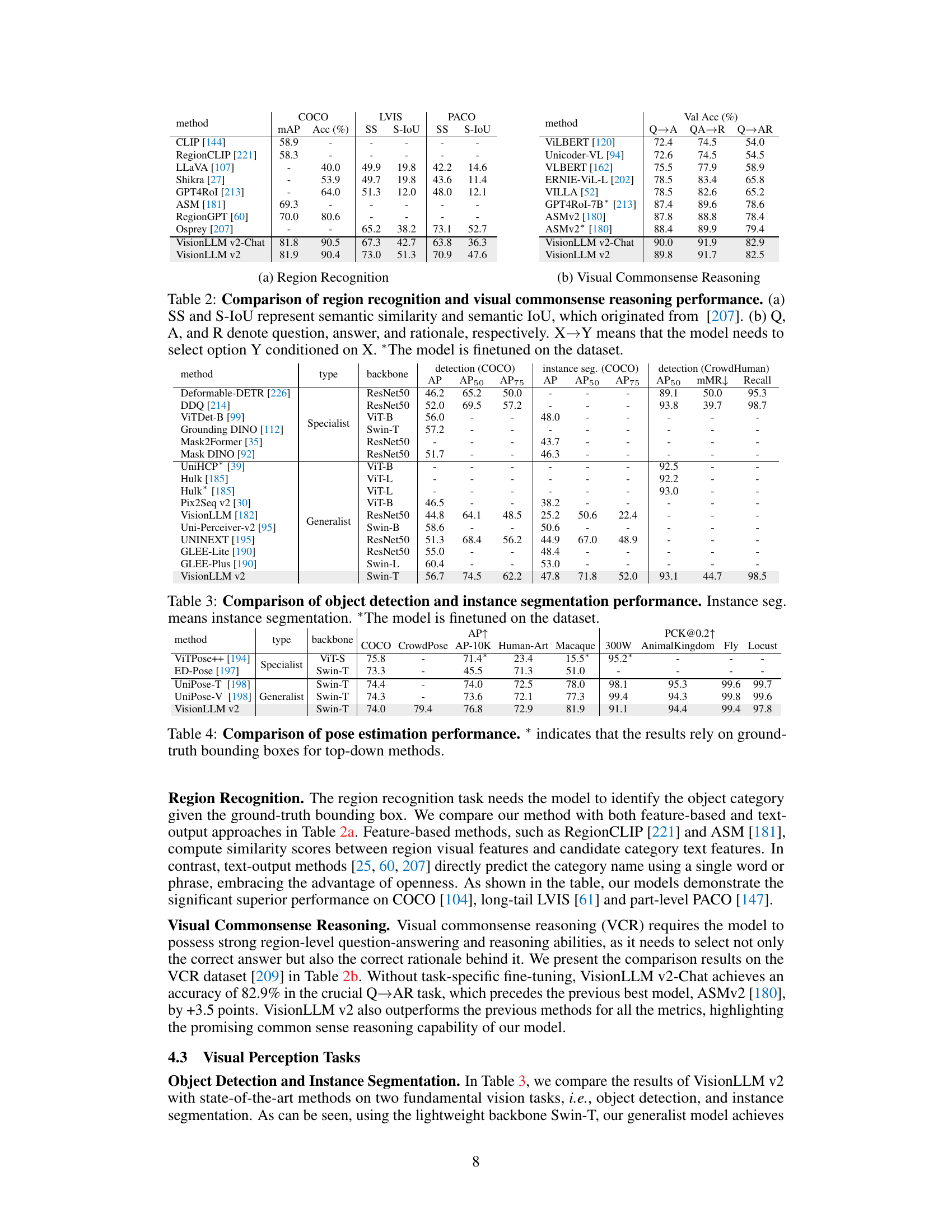

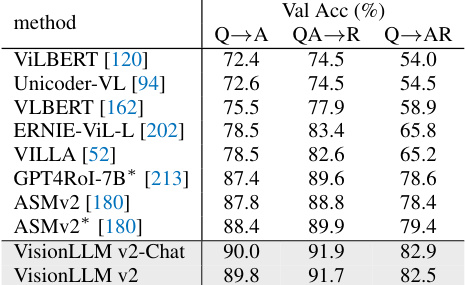

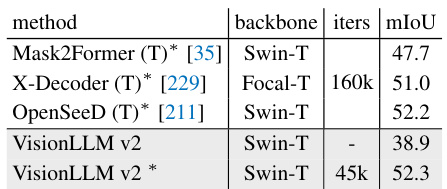

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 and other state-of-the-art models on object detection and instance segmentation tasks. The metrics used are Average Precision (AP), AP at 50% IoU (AP50), AP at 75% IoU (AP75), and mean Average Precision (mAP) for object detection. For instance segmentation, the metrics are AP, AP50, and AP75. The table shows that VisionLLM v2, while a generalist model, achieves comparable results to specialist models, particularly on the COCO dataset. Note that some models listed were finetuned on the dataset, while VisionLLM v2 was not.

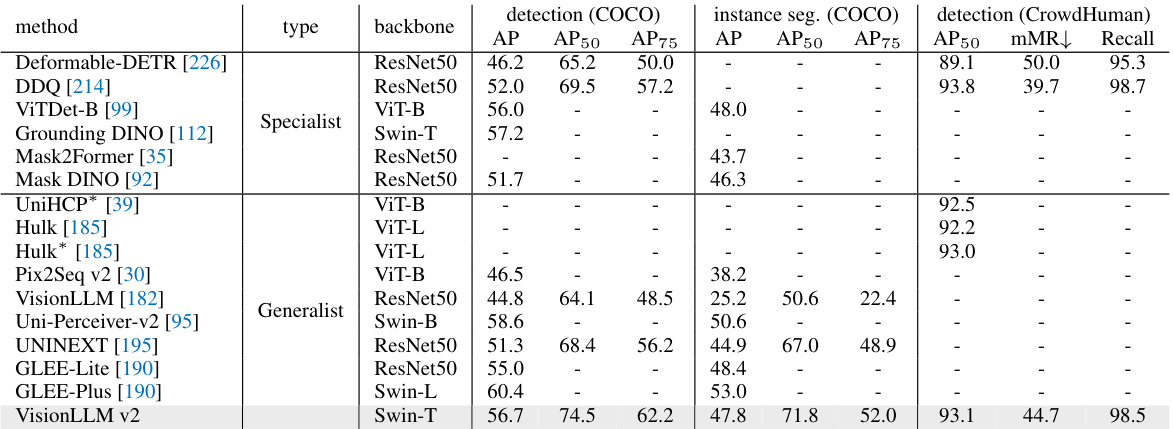

This table compares the performance of different pose estimation methods across various datasets. The metrics used are Average Precision (AP) at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds and Percentage of Correct Keypoints (PCK) at 0.2. The methods are categorized as either specialist (designed for specific tasks like human pose estimation) or generalist (able to handle multiple tasks). The backbone architecture used for each method is also specified. The asterisk (*) indicates that a method uses ground truth bounding boxes, a common approach in top-down pose estimation methods.

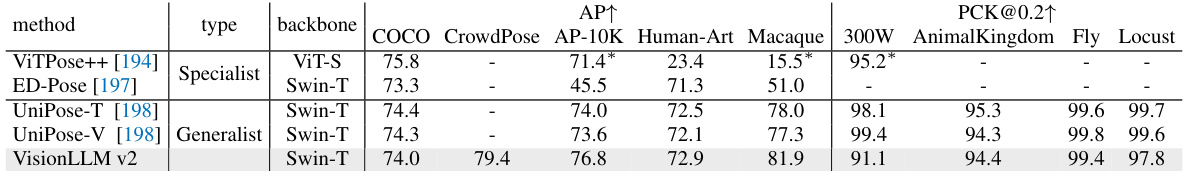

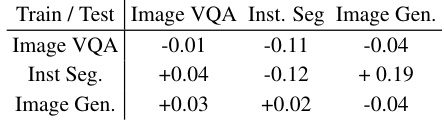

This table presents an ablation study on the multi-task influence in the VisionLLM v2 model. It shows how fine-tuning the model on a single task (Image VQA, Instance Segmentation, or Image Generation) affects the loss on all three tasks. Positive values indicate that training on one task improves performance on another, while negative values suggest a detrimental effect, indicating potential task conflicts.

This table shows the ablation study on the multi-task influence of VisionLLM v2. The model is fine-tuned on a single task (image VQA, instance segmentation, or image generation) for 1000 iterations. The table shows the loss change for all three tasks. A decrease in the loss value indicates beneficial training for the task, while an increase is detrimental. The results indicate the mutual influence of multi-task joint training, highlighting the advantages and disadvantages of training on specific tasks and the impact on overall performance across tasks.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on various multimodal dialogue benchmarks. It breaks down the results into two categories of datasets: academic-oriented and instruction-following. Academic-oriented datasets focus on visual question answering and reasoning, while instruction-following datasets evaluate the model’s ability to follow instructions across different tasks. The table highlights the VisionLLM v2’s performance relative to other models and notes when training annotations were observed during training.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. These benchmarks are categorized into academic-oriented datasets (focused on visual question answering) and instruction-following datasets (testing the model’s ability to follow instructions). The table shows the performance of each model on various metrics for each dataset, highlighting VisionLLM v2’s performance relative to others. The asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations were observed during training, possibly influencing the results.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art models on object detection and instance segmentation tasks using the COCO and CrowdHuman datasets. It shows the average precision (AP), AP at 50% IoU (AP50), AP at 75% IoU (AP75), and mMR (mean average precision) for different models and backbones (ResNet50, ViT-B, Swin-T, ViT-L, etc.). The table highlights VisionLLM v2’s performance against specialist models and demonstrates its capabilities in these visual perception tasks.

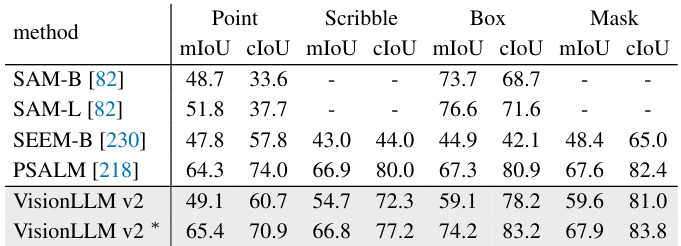

This table compares the performance of different models on the COCO-interactive dataset for interactive segmentation. The models are evaluated on metrics such as mIoU and cIoU (Intersection over Union). The table highlights the performance of VisionLLM v2, both before and after fine-tuning on the specific task, demonstrating its improvement after fine-tuning. It also shows the results of various other state-of-the-art methods.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art models on interactive segmentation using different visual prompts (point, scribble, box, mask). The mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) and cIoU (cumulative IoU) metrics are reported. The * indicates that VisionLLM v2 was fine-tuned for this specific task, showing a significant improvement in performance.

This table compares the performance of the VisionLLM v2 model with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. It breaks down the results across two types of datasets: academic-oriented datasets (designed for evaluating visual question answering and related tasks) and instruction-following datasets (focused on evaluating models’ ability to follow complex instructions in multimodal contexts). The table shows that VisionLLM v2 achieves competitive or better performance than other models, especially on instruction-following tasks.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art models for object detection and instance segmentation tasks on the COCO and CrowdHuman datasets. It shows the AP, AP50, AP75, and mMR metrics for both tasks and indicates whether the model was fine-tuned on the dataset. The table highlights VisionLLM v2’s competitive performance, especially given its use of a lightweight Swin-T backbone.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SoTA) multimodal large language models (MLLMs) on several benchmark datasets. It’s split into academic-oriented datasets (focused on visual question answering) and instruction-following datasets (assessing the model’s ability to follow complex instructions). The asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations of that dataset were observed during the training of the corresponding model. The table helps demonstrate VisionLLM v2’s performance against other models on a range of tasks.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art models on two tasks: region recognition and visual commonsense reasoning. Region recognition assesses the model’s ability to identify objects within a given bounding box, while visual commonsense reasoning tests its ability to answer questions and provide rationales based on images and language. The table shows performance metrics such as mAP (mean Average Precision), accuracy, semantic similarity (SS), semantic IoU (S-IoU), and question-answer-rationale (QAR) scores. The results indicate VisionLLM v2’s competitive performance compared to specialized models, especially on visual commonsense reasoning.

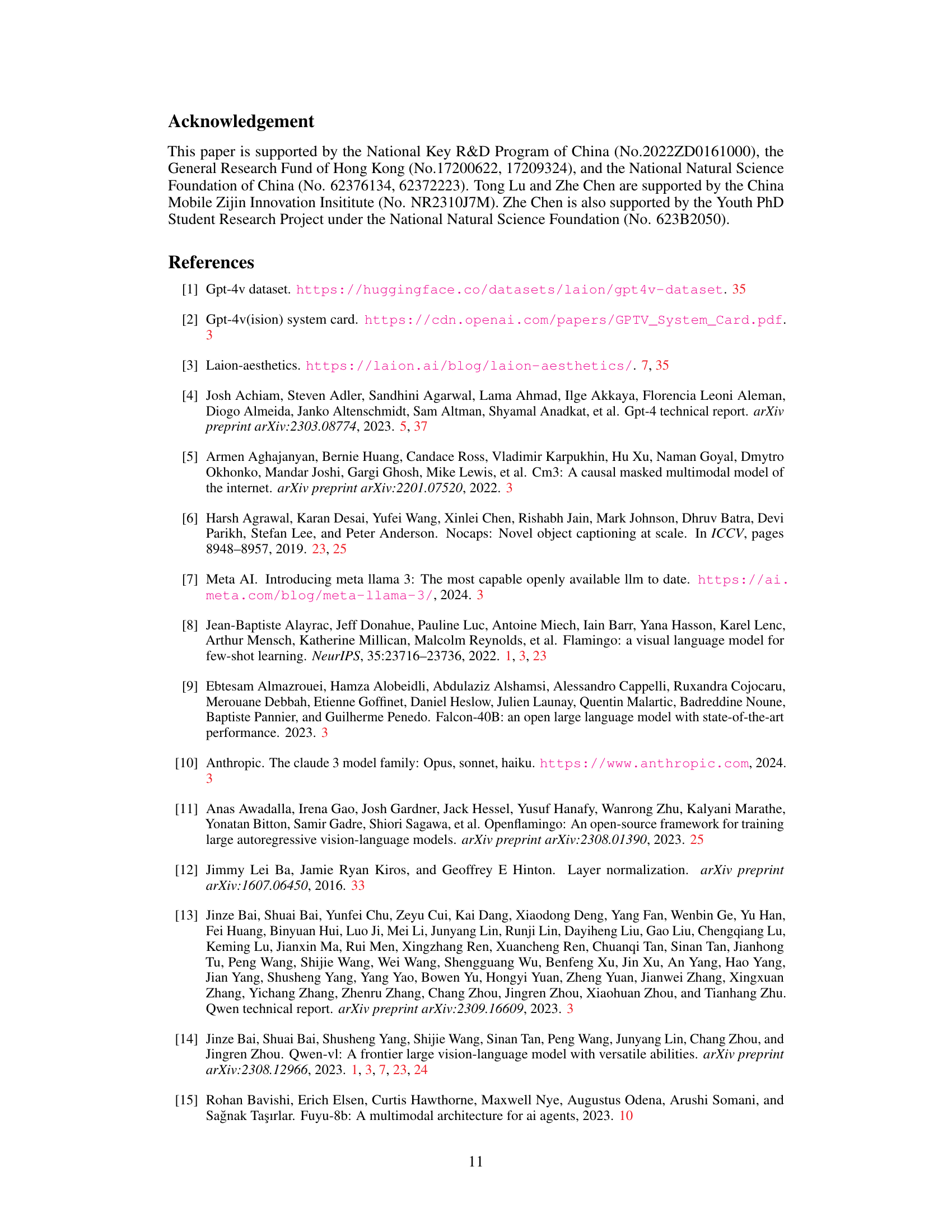

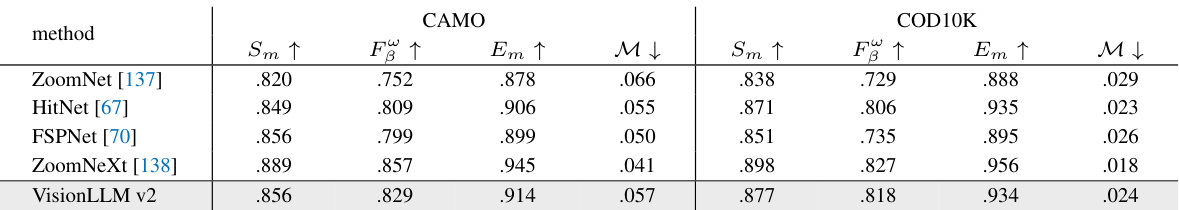

This table presents the ablation study on the number of super-link queries used in VisionLLM v2. It evaluates the impact of varying the number of queries on four key visual perception tasks: instance segmentation using the COCO dataset, visual grounding using the RefCOCO dataset, pose estimation using the COCO dataset, and interactive segmentation using scribbles on the COCO dataset. The results show that increasing the number of queries generally improves performance across all four tasks, indicating that richer representations lead to better results. The default setting (4 queries) is highlighted in gray.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with state-of-the-art (SoTA) models on various multimodal dialogue benchmarks. It breaks down the results across two types of datasets: academic-oriented datasets (VQA tasks) and instruction-following datasets. The academic datasets assess the model’s ability to answer questions about images, while the instruction-following datasets evaluate the model’s capability to follow instructions and perform tasks based on them. The asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations were visible to the model during training, highlighting a potential advantage for those models.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SoTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. These benchmarks are categorized into academic-oriented datasets (focused on visual question answering) and instruction-following datasets (assessing the model’s ability to follow instructions). The table shows that VisionLLM v2 achieves competitive or superior performance compared to SoTA models across various metrics, particularly on instruction-following datasets, even though the training annotations for some datasets were visible during training. The asterisk (*) indicates that the model’s training data included the annotations from the dataset being evaluated.

This table compares the performance of VisionLLM v2 with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. It breaks down the results across two types of datasets: academic-oriented datasets (VQAv2, GQA, VizWiz, ScienceQA, TextVQA) which focus on question-answering tasks, and instruction-following datasets (POPE, MME, MMBench-EN/CN, SEED-Bench) which evaluate the model’s ability to follow instructions. The asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations for the dataset were observed during training, signifying a potential advantage for models that have seen that data during training.

This table compares the performance of the VisionLLM v2 model with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on several multimodal dialogue benchmarks. These benchmarks are categorized into academic-oriented datasets (focused on visual question answering) and instruction-following datasets (testing the model’s ability to follow instructions). The table shows various metrics for each model on each dataset, highlighting the VisionLLM v2’s performance relative to the other models. An asterisk (*) indicates that the training annotations of the dataset were observed during training, implying potential data leakage.

Full paper#