TL;DR#

Many machine learning models suffer from spurious correlations, meaning they rely on easily-learnt but irrelevant features in the training data, leading to poor generalization to unseen data. Addressing this issue is particularly challenging when bias labels (information about the spurious correlations) are unavailable. This significantly limits the models’ fairness and reliability.

This research introduces a new method called DPR (Disagreement Probability based Resampling for debiasing) to tackle this issue. DPR leverages the disagreement between a biased model’s prediction and the true label to identify and upsample bias-conflicting samples. It does so without using any bias labels, making it more practical for real-world scenarios. Empirical evaluations on several benchmark datasets show that DPR significantly outperforms existing methods that don’t use bias labels, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing model robustness and fairness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical issue in machine learning: the problem of spurious correlations. It proposes a novel debiasing method (DPR) that doesn’t require bias labels, a significant advantage over existing techniques. This is highly relevant to researchers working on fairness, robustness, and generalization in machine learning models, opening avenues for improved model performance and trustworthiness across various applications.

Visual Insights#

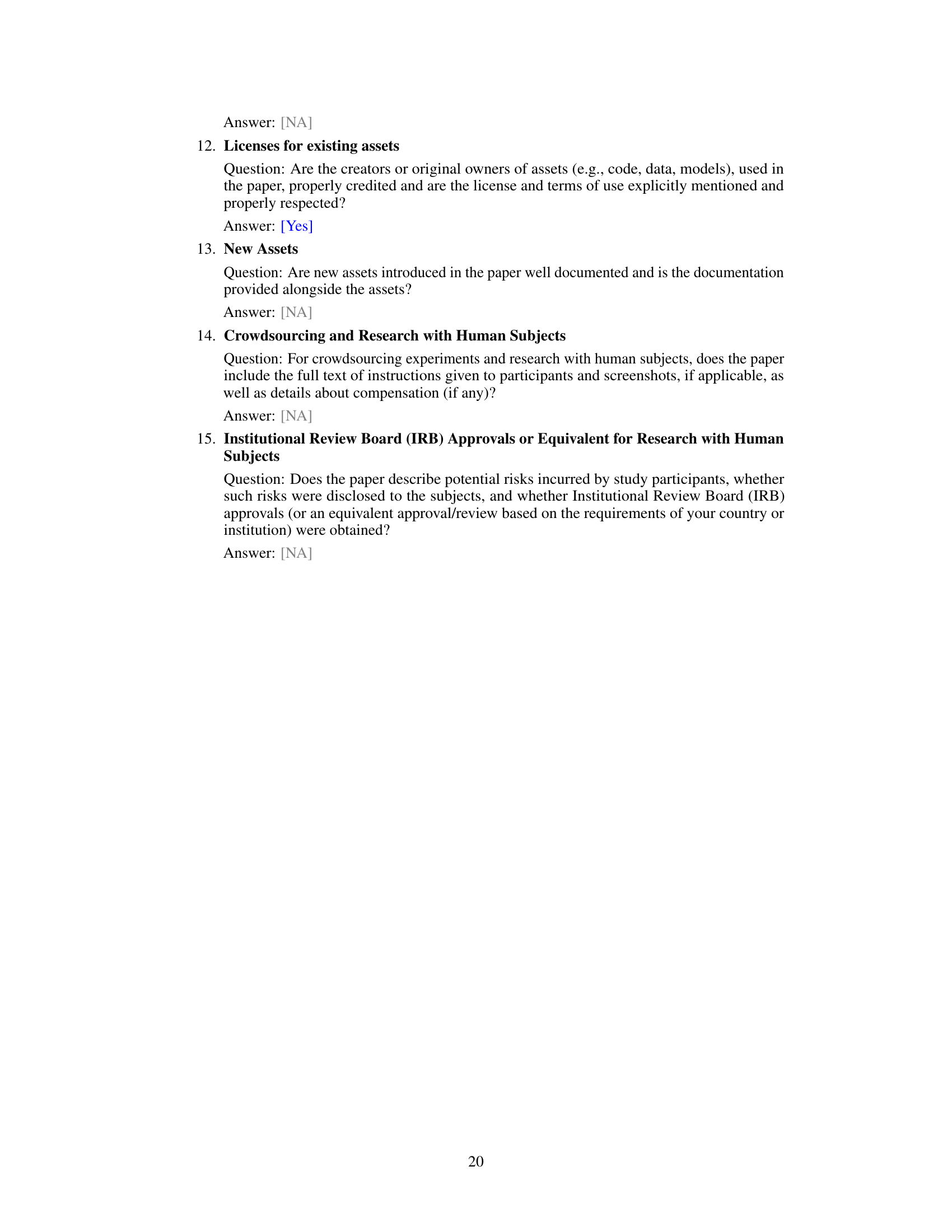

🔼 This figure shows examples of cow and camel images used in a classification task. The images are categorized by their background (desert or pasture). The red dotted boxes highlight examples where the typical spurious correlation (cow in pasture, camel in desert) does not hold, which is crucial for illustrating the concept of spurious correlations and the need for methods robust against them.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of the cow/camel classification task. Red dotted boxes indicate samples where spurious correlations do not hold.

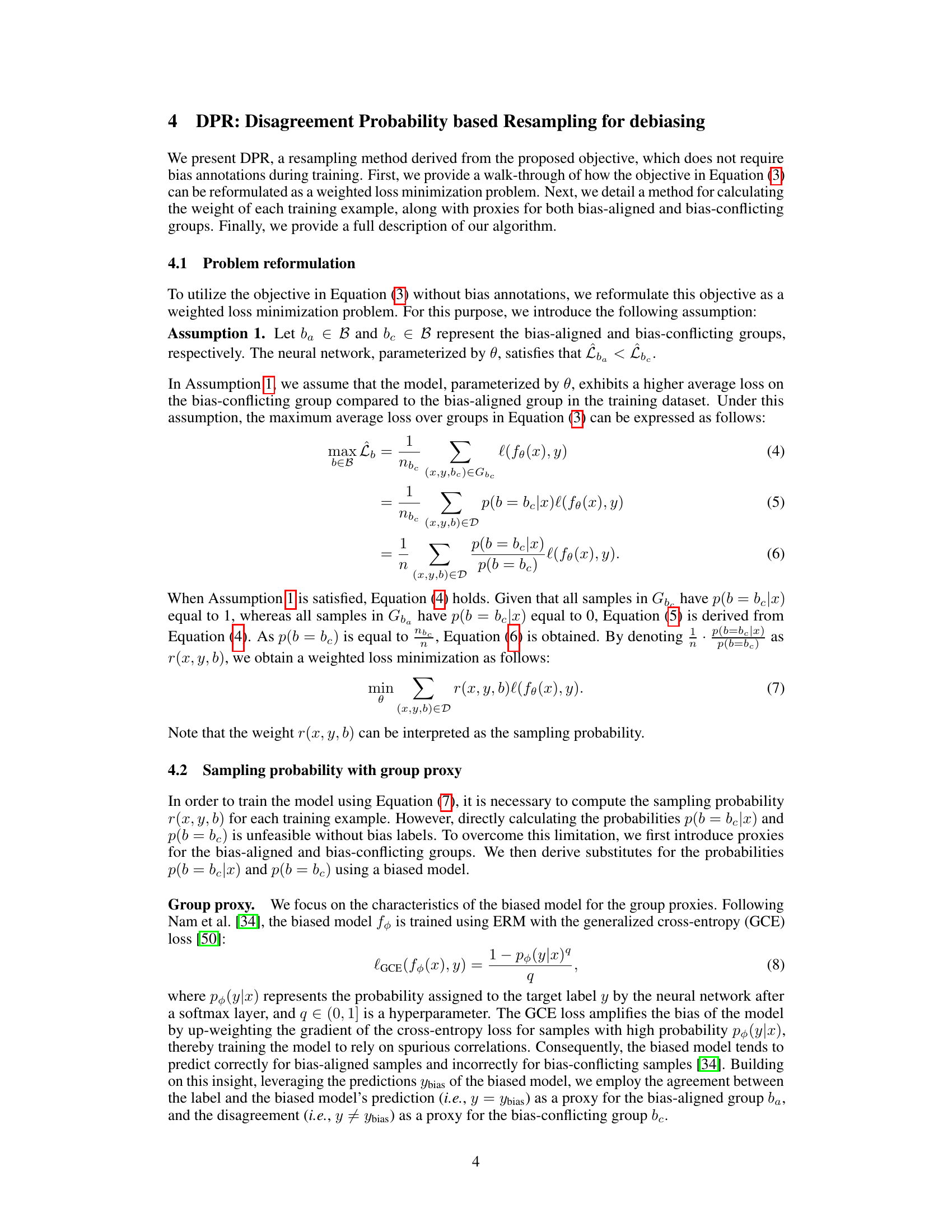

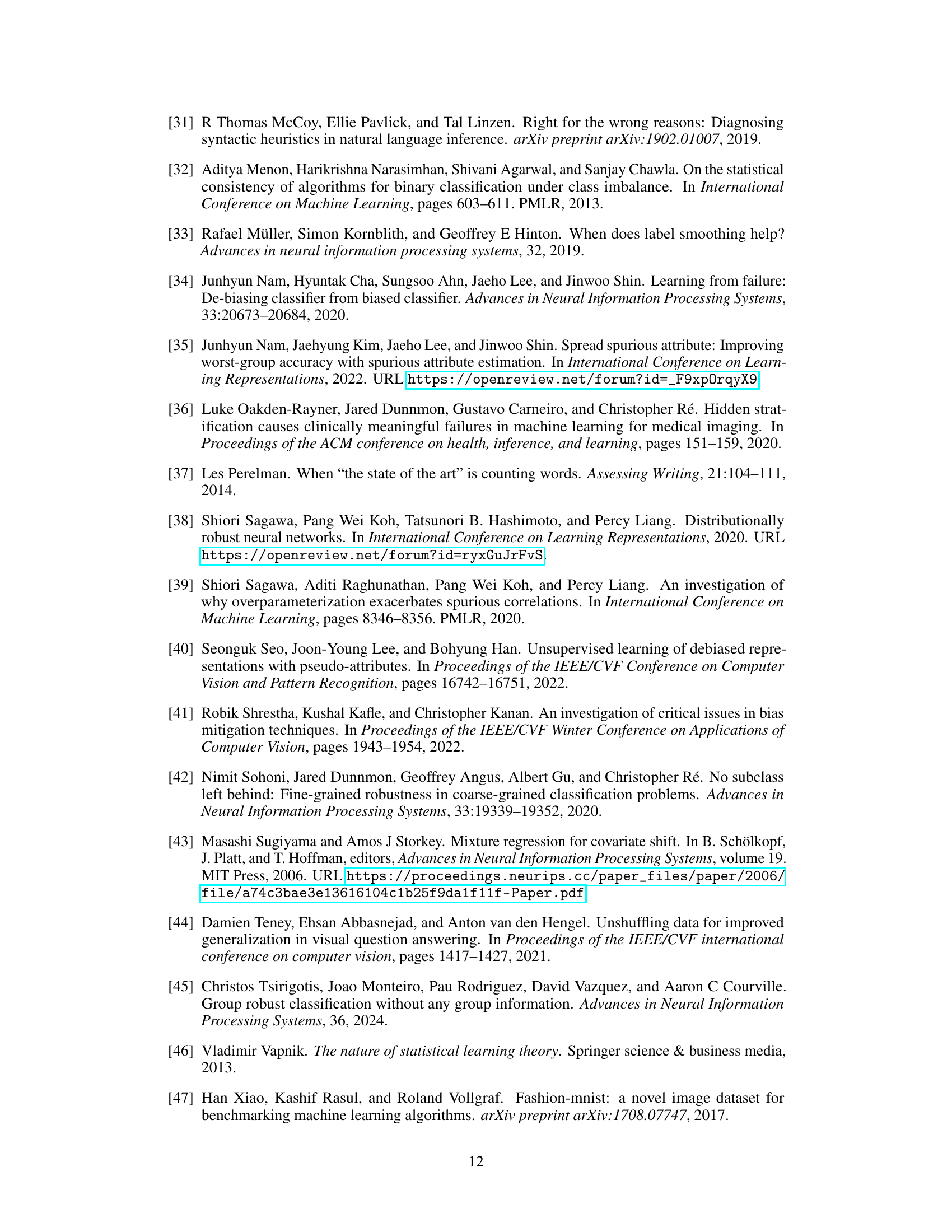

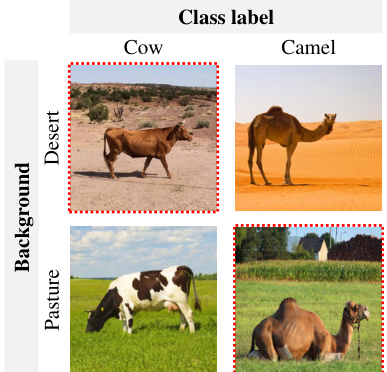

🔼 This table presents the average accuracies and standard deviations from three trials on the C-MNIST and MB-MNIST datasets with various bias-conflicting ratios. It compares the performance of the proposed DPR method against several baselines (ERM, JTT, DFA, PGD, LC) across different bias-conflicting sample ratios (0.5%, 1%, 5% for C-MNIST; 10%, 20%, 30% for MB-MNIST). The best-performing method for each scenario is highlighted in bold. The results from Ahn et al. [1] are used for comparison, except for the LC baseline.

read the caption

Table 1: Average accuracies and standard deviations over three trials on two synthetic image datasets, C-MNIST and MB-MNIST, under varying ratios (%) of bias-conflicting samples. Except for LC, the results of baselines reported in Ahn et al. [1] are provided. The best performances are highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

Spurious Correlation Bias#

Spurious correlation bias, a pervasive issue in machine learning, arises when models erroneously associate a feature with the target variable due to a coincidental relationship rather than a genuine causal link. This bias is particularly harmful because it leads to poor generalization on unseen data where the spurious correlation doesn’t hold. Models trained with empirical risk minimization (ERM) are especially susceptible as they optimize for overall performance, potentially overlooking the underlying flawed associations. The impact manifests as biased predictions, especially for underrepresented groups, whose data may lack the spurious correlation prevalent in the training set. Addressing this bias requires careful consideration of the dataset, looking for and mitigating misleading correlations. Techniques like data augmentation or resampling can help improve robustness, but a thorough understanding of the data generating process is crucial for effective bias mitigation. Ultimately, recognizing and correcting spurious correlation bias is key to building reliable and generalizable machine learning models.

DPR Debiasing Method#

The DPR (Disagreement Probability based Resampling) debiasing method offers a novel approach to mitigate the effects of spurious correlations in machine learning models without requiring bias labels. It leverages the disagreement between a biased model’s prediction and the true label to identify bias-conflicting samples—those lacking spurious correlations. DPR then strategically upsamples these samples, based on their disagreement probability, during training. This approach is particularly valuable when bias labels are unavailable or expensive to obtain. The theoretical analysis supports DPR’s effectiveness by showing it reduces reliance on spurious correlations and improves performance consistency across both bias-aligned and bias-conflicting groups. Empirical results demonstrate that DPR achieves state-of-the-art performance on multiple benchmarks, highlighting its practical utility. However, DPR’s success hinges on the quality of the biased model in accurately capturing spurious correlations; thus, the choice of architecture and training procedure for the biased model is crucial for DPR’s overall effectiveness.

Empirical Performance#

An empirical performance analysis section in a research paper would typically present the results of experiments designed to evaluate the proposed method. A strong analysis would go beyond simply reporting metrics; it should include comparisons against relevant baselines, demonstrating clear improvements. Statistical significance testing would be crucial to ensure that observed gains aren’t due to chance. The paper should also analyze performance across various subsets of the data to assess generalizability and robustness, particularly if the method targets issues like bias or spurious correlations. A thoughtful discussion of both the strengths and limitations of the empirical results is vital, potentially pointing to future research directions or explaining inconsistencies. Visualizations such as graphs and tables should clearly present the data, and the accompanying text should guide the reader to the most important insights.

Theoretical Analysis of DPR#

The theoretical analysis section of a paper on Disagreement Probability based Resampling for Debiasing (DPR) would likely focus on formally establishing DPR’s effectiveness in mitigating the effects of spurious correlations. This would probably involve proving bounds on the disparity between the loss on bias-aligned and bias-conflicting groups, demonstrating that DPR minimizes this gap. Key theorems might show that the overall expected loss is bounded, and potentially relate the bound’s tightness to the size of the bias-conflicting group. The analysis would rigorously justify the algorithm’s design choices, for instance, the use of disagreement probability as a proxy for bias labels and potentially link the choice of loss function to the theoretical guarantees. A core aspect would be proving the consistency of DPR’s performance across different groups, irrespective of spurious correlations, and perhaps showing how DPR reduces the model’s dependence on such correlations, ideally connecting the theoretical results to observed empirical improvements. The analysis might also address the assumptions made and discuss their practical implications, providing a stronger foundation for the empirical results and highlighting the generalizability of the DPR approach.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on mitigating spurious correlations could explore several promising avenues. Extending DPR to more complex scenarios involving multiple, intertwined bias attributes is crucial. The current approach excels with singular biases but requires refinement for situations with multifaceted spurious correlations. Another area ripe for investigation is developing more robust proxies for bias-conflicting samples. While the disagreement probability method shows promise, alternative approaches may improve accuracy and efficiency, especially in datasets lacking clear-cut spurious relationships. A deeper theoretical analysis could further illuminate DPR’s performance, ideally providing tighter bounds on its generalization error and exploring its effectiveness under varying data distributions. Finally, empirical evaluations on diverse, real-world datasets, beyond those used in this research, are essential to verify the generalizability and robustness of DPR across a broader spectrum of applications. In essence, enhancing DPR’s ability to handle complex bias structures and providing more theoretical justification for its performance should be prioritized.

More visual insights#

More on figures

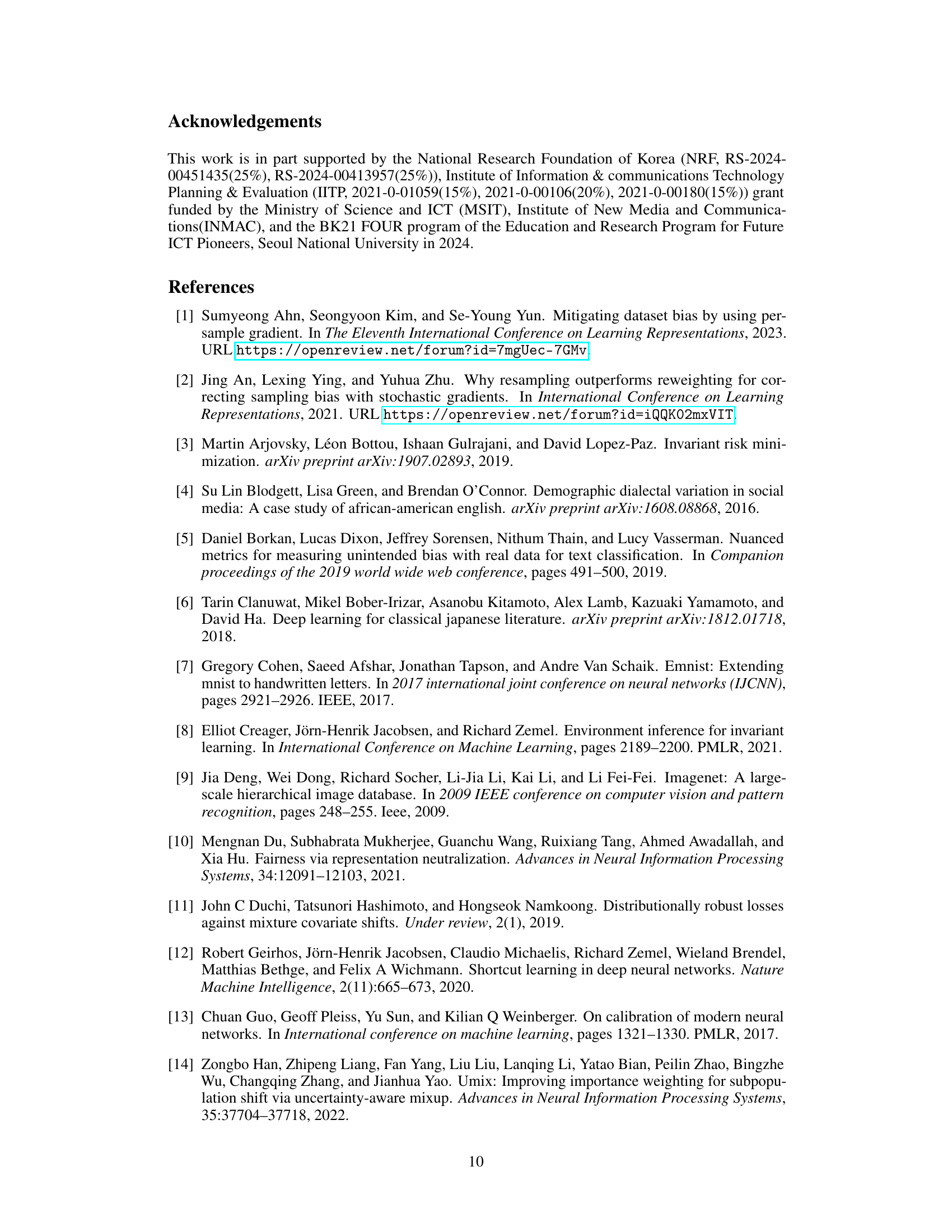

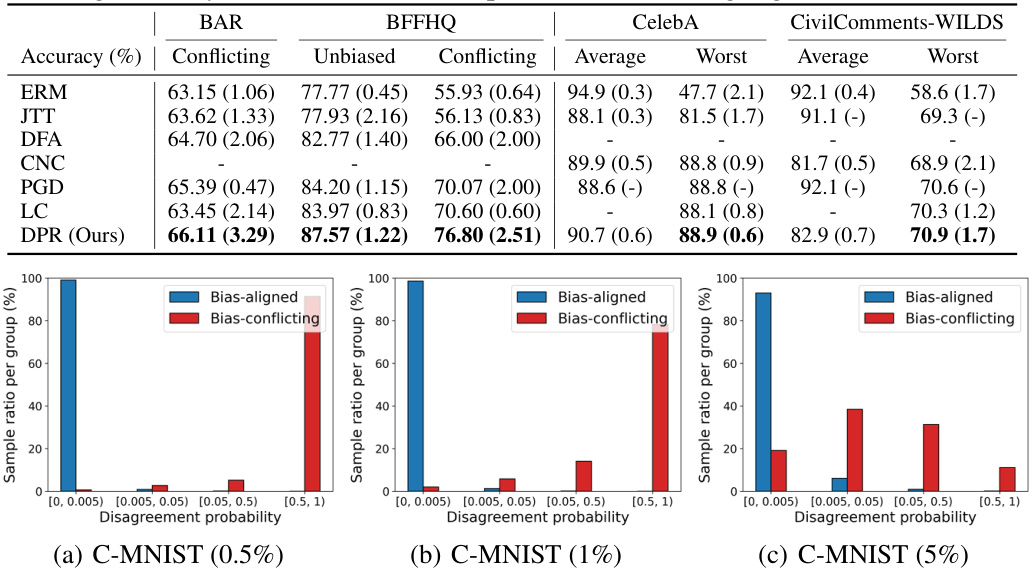

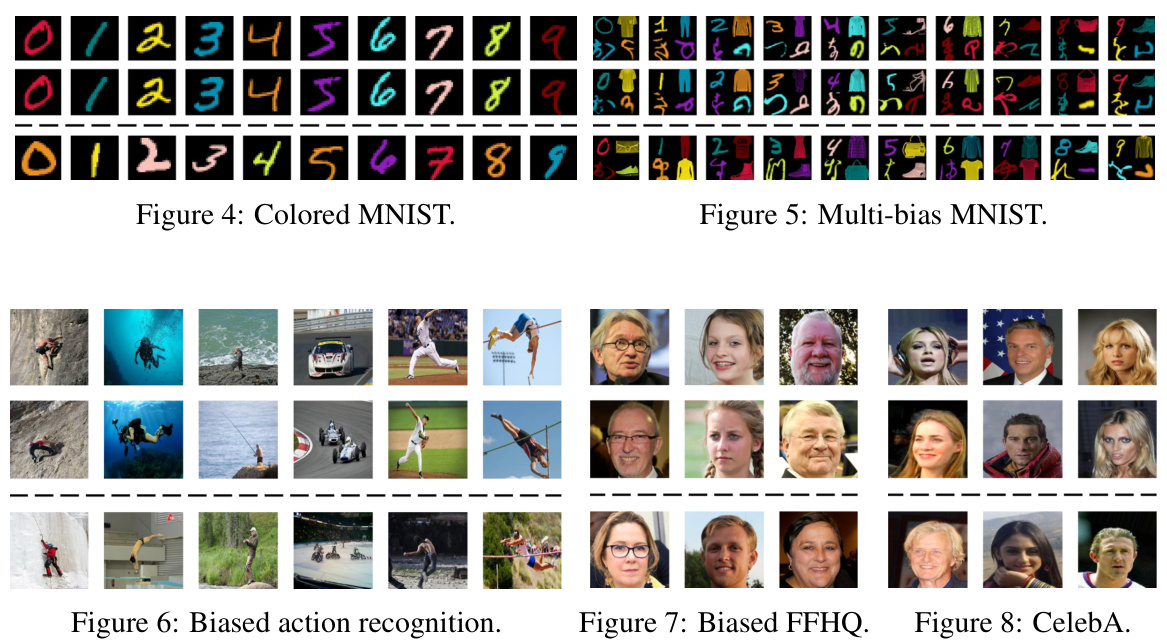

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of disagreement probabilities for bias-aligned and bias-conflicting samples in the C-MNIST dataset with different bias-conflicting ratios (0.5%, 1%, and 5%). The x-axis represents the disagreement probability, which is the probability that the prediction of a biased model disagrees with the true label. The y-axis represents the percentage of samples within each group that fall into each bin of disagreement probability. It demonstrates that the disagreement probability can effectively distinguish between bias-aligned and bias-conflicting samples, with bias-aligned samples having lower disagreement probabilities and bias-conflicting samples having higher disagreement probabilities. This supports the effectiveness of the proposed DPR method that leverages this disagreement probability to improve model robustness.

read the caption

Figure 2: Distributions of disagreement probabilities for each sample within bias-aligned and bias-conflicting groups.

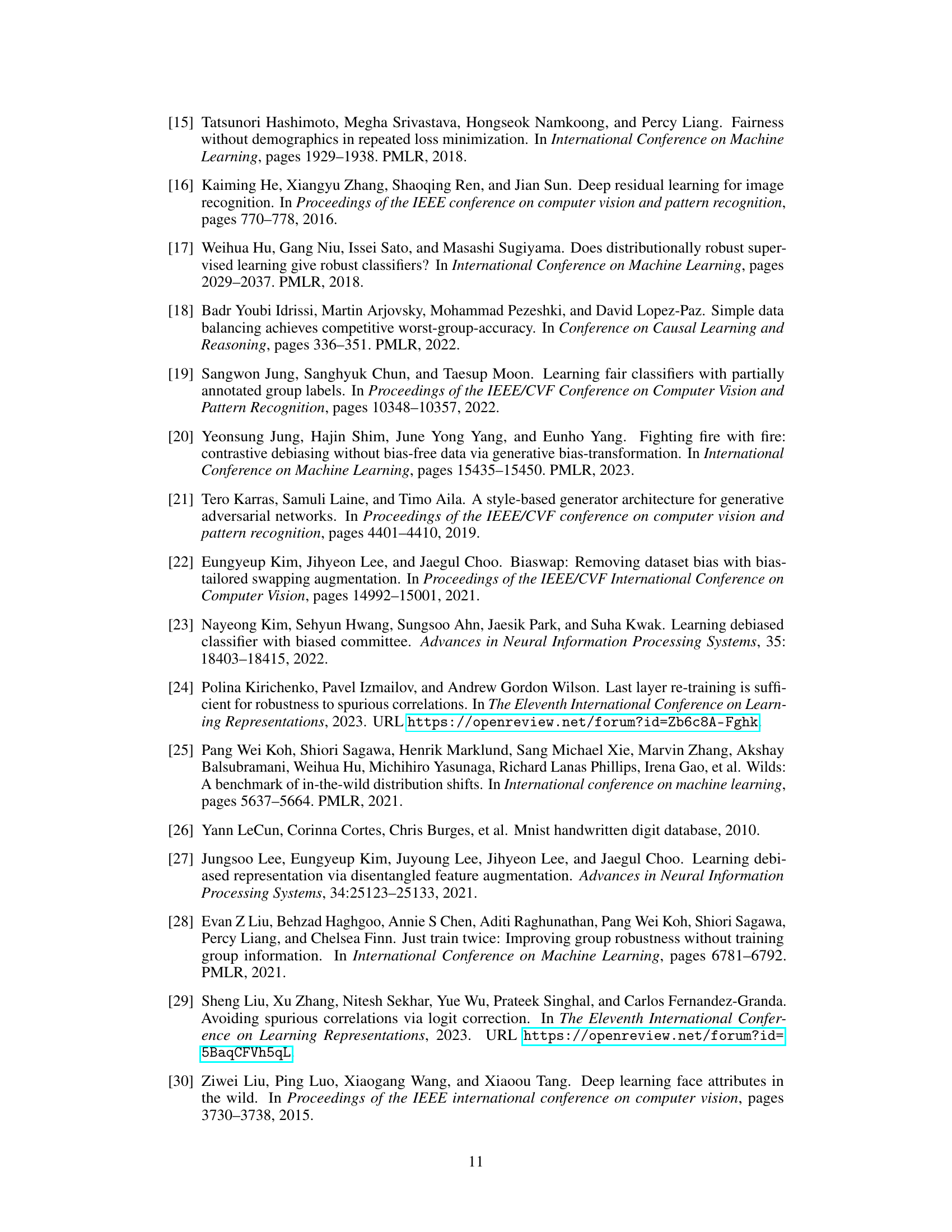

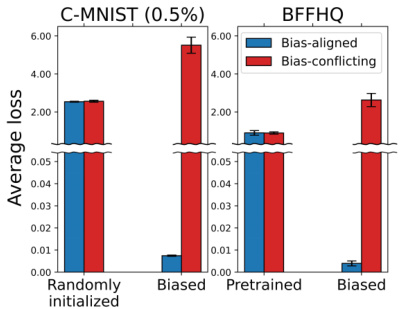

🔼 This figure shows the average loss of three different model types (randomly initialized, pretrained, and biased) on bias-aligned and bias-conflicting groups for two datasets (C-MNIST with 0.5% bias-conflicting samples and BFFHQ). The results illustrate that randomly initialized and pretrained models have similar average losses across both groups. In contrast, the biased model exhibits significantly higher average loss on the bias-conflicting group compared to the bias-aligned group, supporting the assumption made in the DPR method that biased models perform worse on bias-conflicting samples.

read the caption

Figure 3: Average loss of randomly initialized, pretrained, and biased models on bias-aligned and bias-conflicting groups. The error bars represent the standard deviations over three trials.

🔼 This figure illustrates the challenge of spurious correlations in image classification. The task is to classify images as either cows or camels. However, a significant number of cow images have a pasture background, while most camel images show a desert setting. This creates a spurious correlation, where the background becomes a strong predictor of the class label, rather than the actual animal characteristics. The red dotted boxes highlight examples where this spurious correlation does not hold – a camel in a pasture or a cow in a desert.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of the cow/camel classification task. Red dotted boxes indicate samples where spurious correlations do not hold.

More on tables

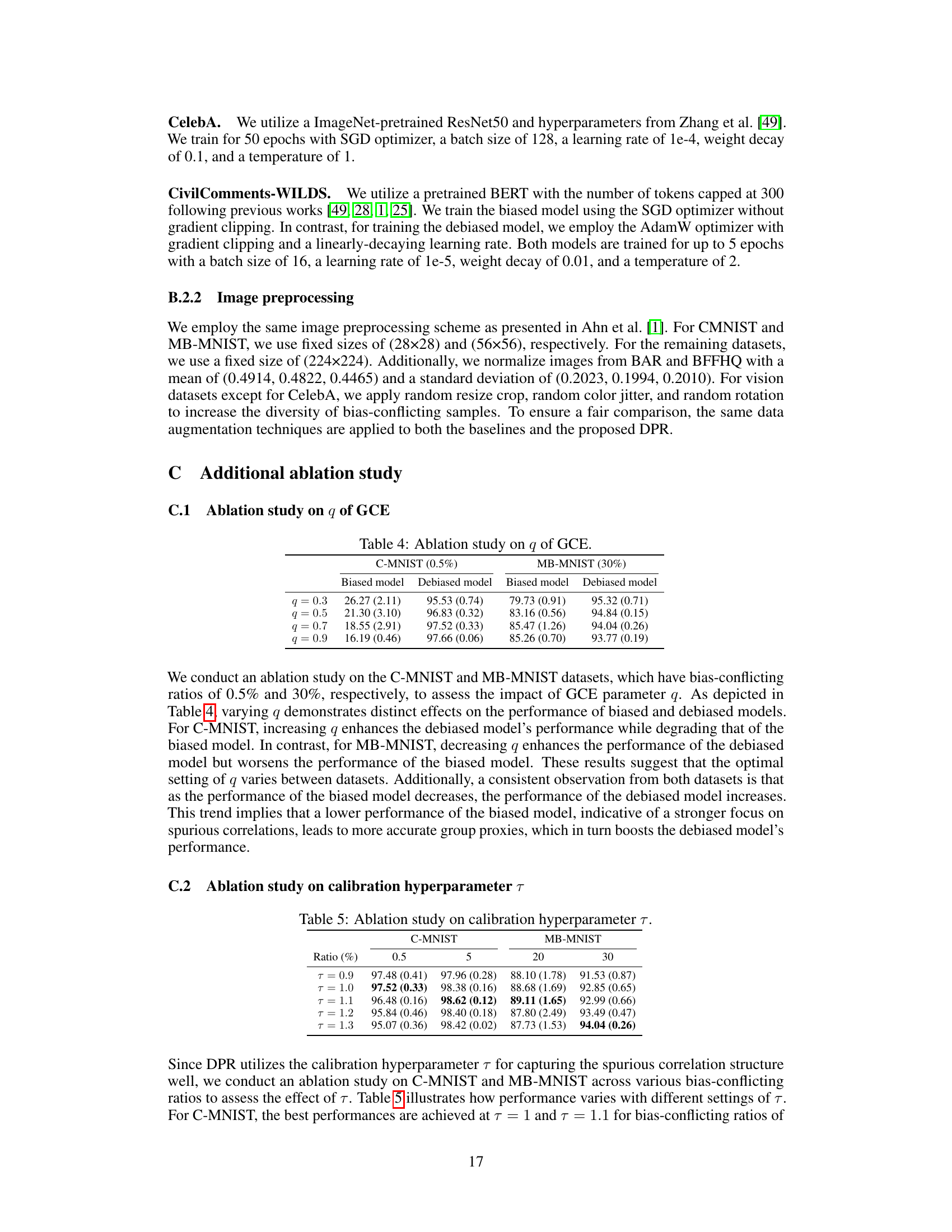

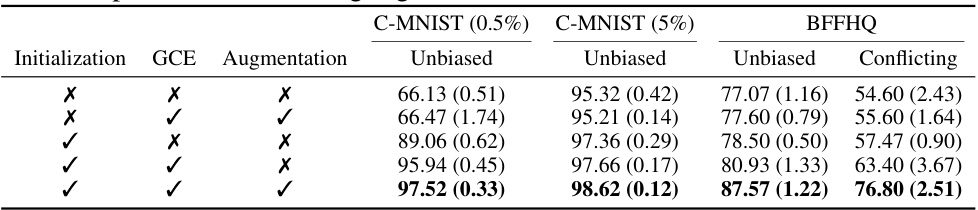

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results for the proposed DPR method. It shows the impact of different components of the method (initialization, GCE, and augmentation) on the performance (unbiased and conflicting accuracy) across two datasets (C-MNIST and BFFHQ). Each row represents a different combination of these components, enabling an analysis of their individual contributions.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation studies of the proposed method on the C-MNIST and BFFHQ datasets. We report the average test accuracies and standard deviations over three trials on unbiased and bias-conflicting test sets. A checkmark (✔) indicates the case where each component of the proposed method is applied. The best performances are highlighted in bold.

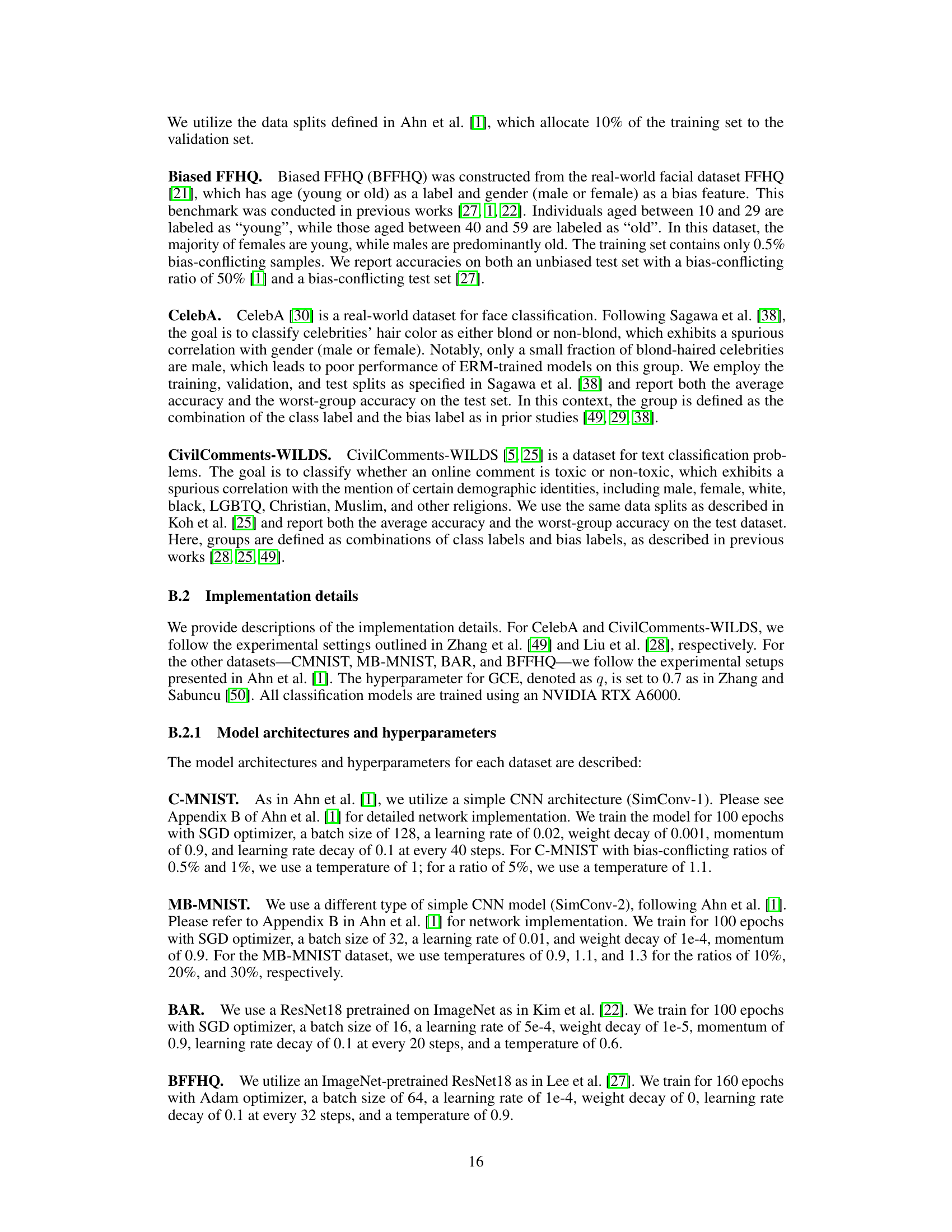

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the impact of the generalized cross-entropy (GCE) parameter ‘q’ on both the biased and debiased models. The study was performed on the C-MNIST (with a 0.5% bias-conflicting ratio) and MB-MNIST (with a 30% bias-conflicting ratio) datasets. The table shows the accuracy of the biased and debiased models for different values of ‘q’ (0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 0.9). The results demonstrate how varying the ‘q’ parameter affects the performance of both models on these two datasets, showcasing the interplay between this parameter and the model’s ability to learn from spurious correlations.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study on q of GCE.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of DPR and other baseline methods on C-MNIST and MB-MNIST datasets with varying bias-conflicting ratios (0.5%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%). The results show the average accuracy and standard deviation across three trials for each method and bias ratio. The best performing method for each scenario is highlighted in bold. Note that the results for some baselines are taken from a previous study (Ahn et al., 2023).

read the caption

Table 1: Average accuracies and standard deviations over three trials on two synthetic image datasets, C-MNIST and MB-MNIST, under varying ratios (%) of bias-conflicting samples. Except for LC, the results of baselines reported in Ahn et al. [1] are provided. The best performances are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This table compares the performance of DPR using resampling and reweighting strategies on the C-MNIST dataset with varying bias-conflicting ratios. It shows that resampling consistently outperforms reweighting across all ratios.

read the caption

Table 6: Comparison of resampling and reweighting.

Full paper#