↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Automatically creating interesting and original games is a difficult task due to the vast design space and challenges in computationally representing and evaluating game rules. Existing approaches often rely on limited rule representations and domain-specific heuristics, limiting their ability to produce truly novel and engaging games. This research addresses these challenges by introducing GAVEL, a system that combines a large language model (LLM) with evolutionary computation.

GAVEL uses the Ludii game description language, which is capable of encoding a wide variety of game rules, to represent games as code. The LLM is trained to intelligently modify and recombine game rules, acting as a mutation operator in an evolutionary algorithm. The system uses quality-diversity optimization to explore the game design space effectively. GAVEL has demonstrated the ability to generate novel and interesting games, including games that differ significantly from those used in its training data. Automatic evaluation metrics and human evaluations confirmed these games’ quality and novelty. GAVEL therefore offers a significant advance in automated game generation, by showing the effectiveness of LLMs in tackling complex design problems and opening exciting avenues for future research in AI-assisted game design.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents GAVEL, a novel approach to automatically generate board games, bridging the gap between human creativity and computational game design. It leverages large language models and evolutionary computation, offering a new direction for automated game design research and opening avenues for investigating novel game mechanics and diverse game genres. This work has significant implications for both the creative arts and AI research.

Visual Insights#

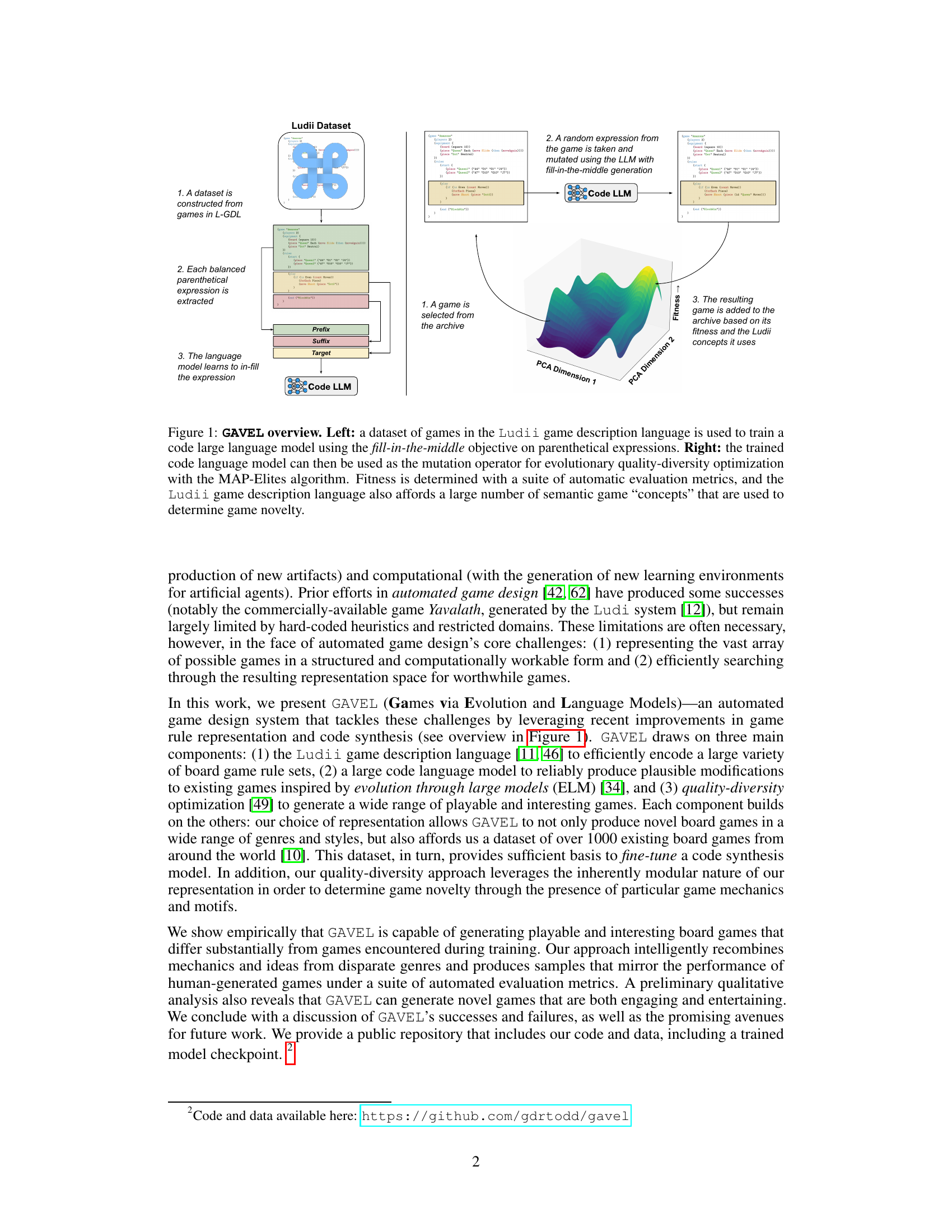

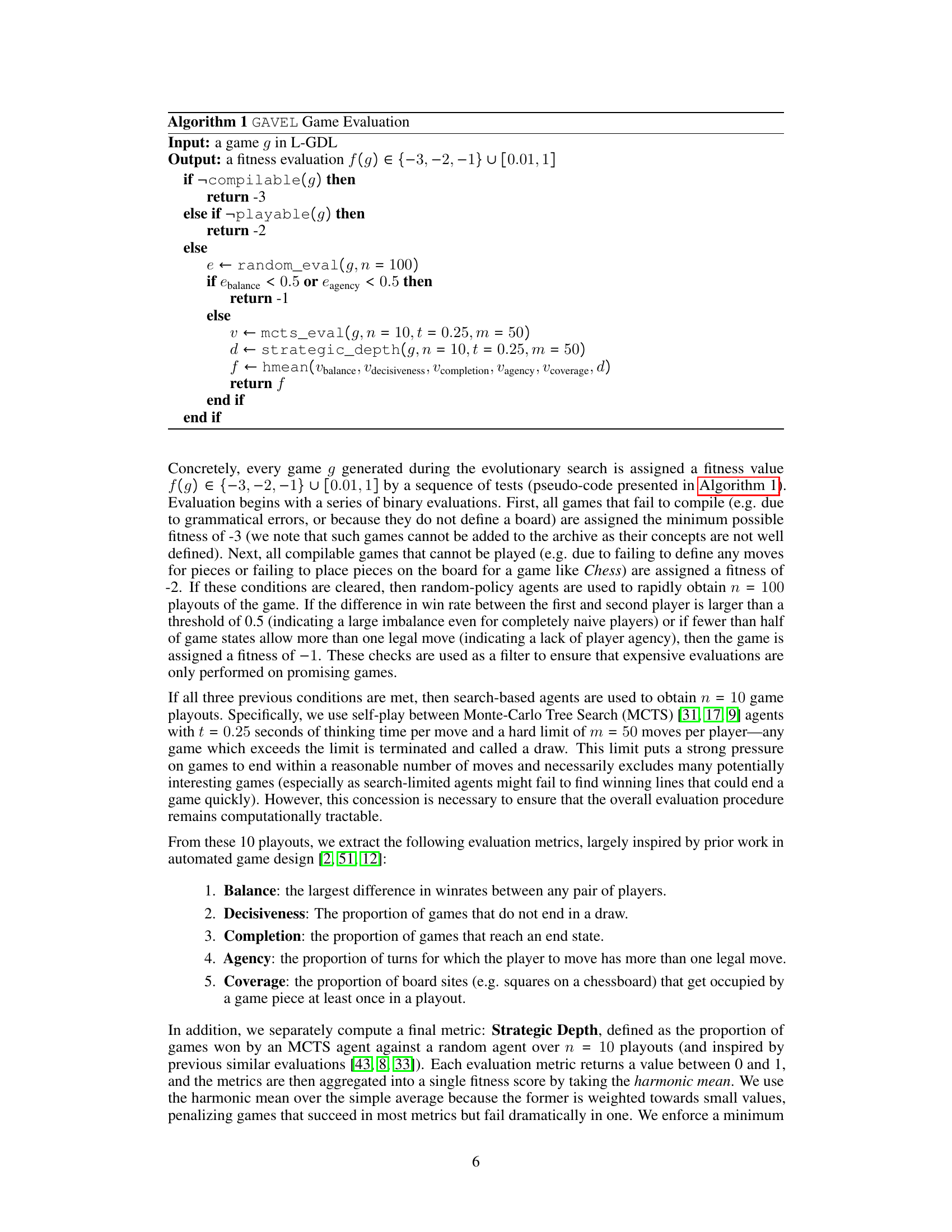

This figure shows a schematic overview of the GAVEL system. The left side illustrates the training process: a dataset of games in the Ludii language is used to train a large language model (LLM) using a fill-in-the-middle approach. This model learns to modify game rules expressed as code. The right side shows how the trained LLM is used within an evolutionary algorithm (MAP-Elites). The LLM acts as a mutation operator, generating new game variants which are then evaluated based on automatic metrics and novelty scores (Ludii concepts).

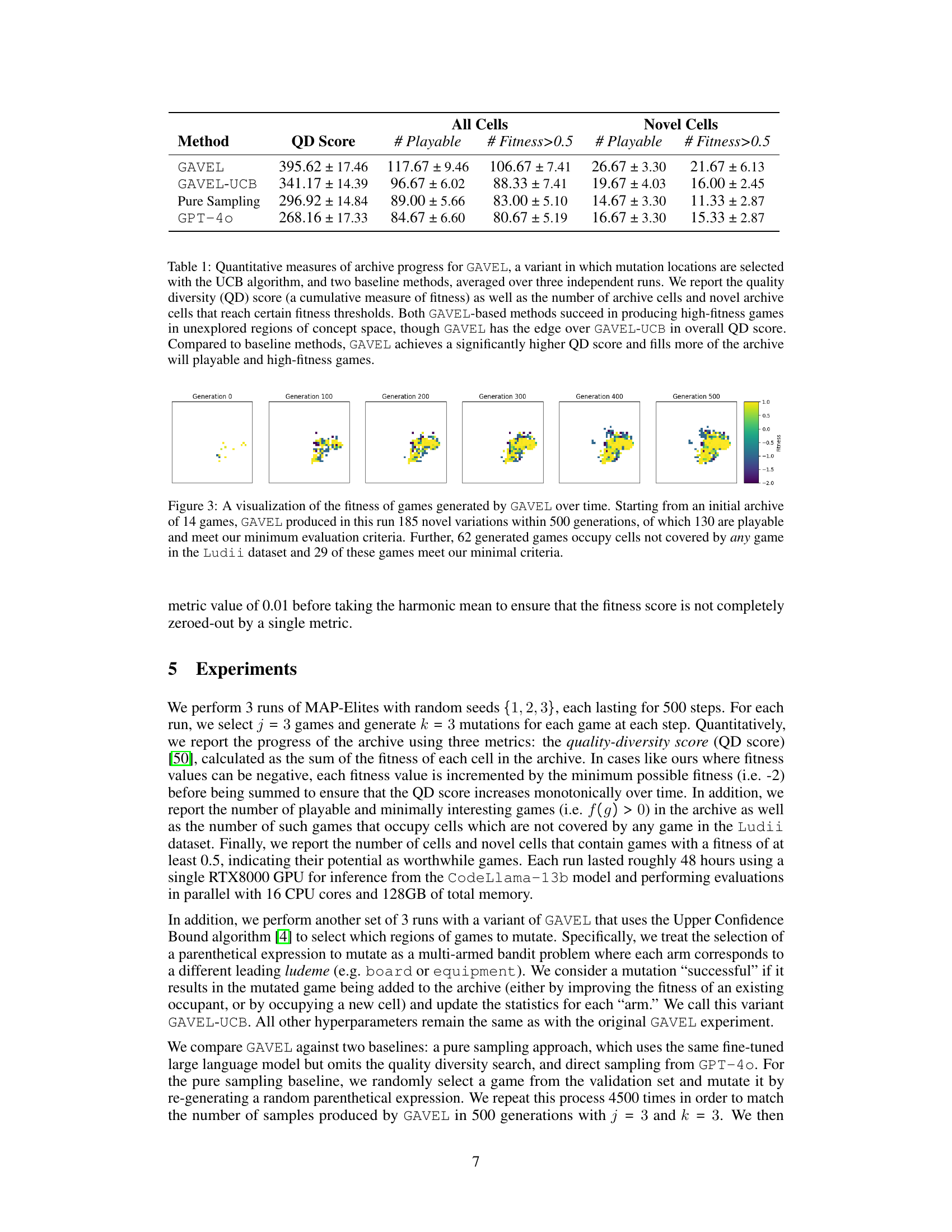

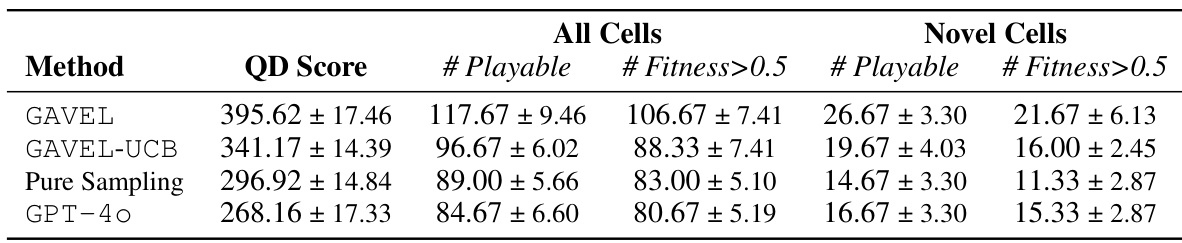

This table presents a quantitative comparison of GAVEL’s performance against two baseline methods (pure sampling and GPT-4). It shows the quality diversity score (QD), the number of playable games, and the number of games with fitness above 0.5, both in all cells of the archive and only in novel cells (cells not occupied by games in the initial dataset). The results are averaged across three independent runs and highlight GAVEL’s success in generating high-fitness games, especially in under-explored regions of the game space.

In-depth insights#

Evolving Game AI#

Evolving Game AI represents a significant advancement in artificial intelligence, particularly within the context of game development and playing. By utilizing evolutionary algorithms, researchers can develop AI agents capable of learning and adapting strategies in dynamic environments. This contrasts with traditional game AI, often based on handcrafted rules, which can struggle to adapt to unexpected situations. Evolutionary approaches, however, allow for the automatic generation of novel game strategies and even the creation of entirely new games. Genetic algorithms are frequently used to evolve populations of AI agents, where superior agents are selected for reproduction, creating new generations that exhibit improved gameplay capabilities. This process allows for the discovery of complex and unexpected strategies that may not be apparent using conventional methods. However, the scalability and computational cost of evolutionary AI remain major challenges. Efficient methods for evaluating the performance of evolved agents and managing the complexity of the evolutionary search space are essential for progress in this field. The application of evolutionary algorithms to game AI represents a powerful method for creating adaptable and innovative systems capable of surpassing human capabilities in specific game contexts, showcasing the potential of artificial evolution to solve complex problems.

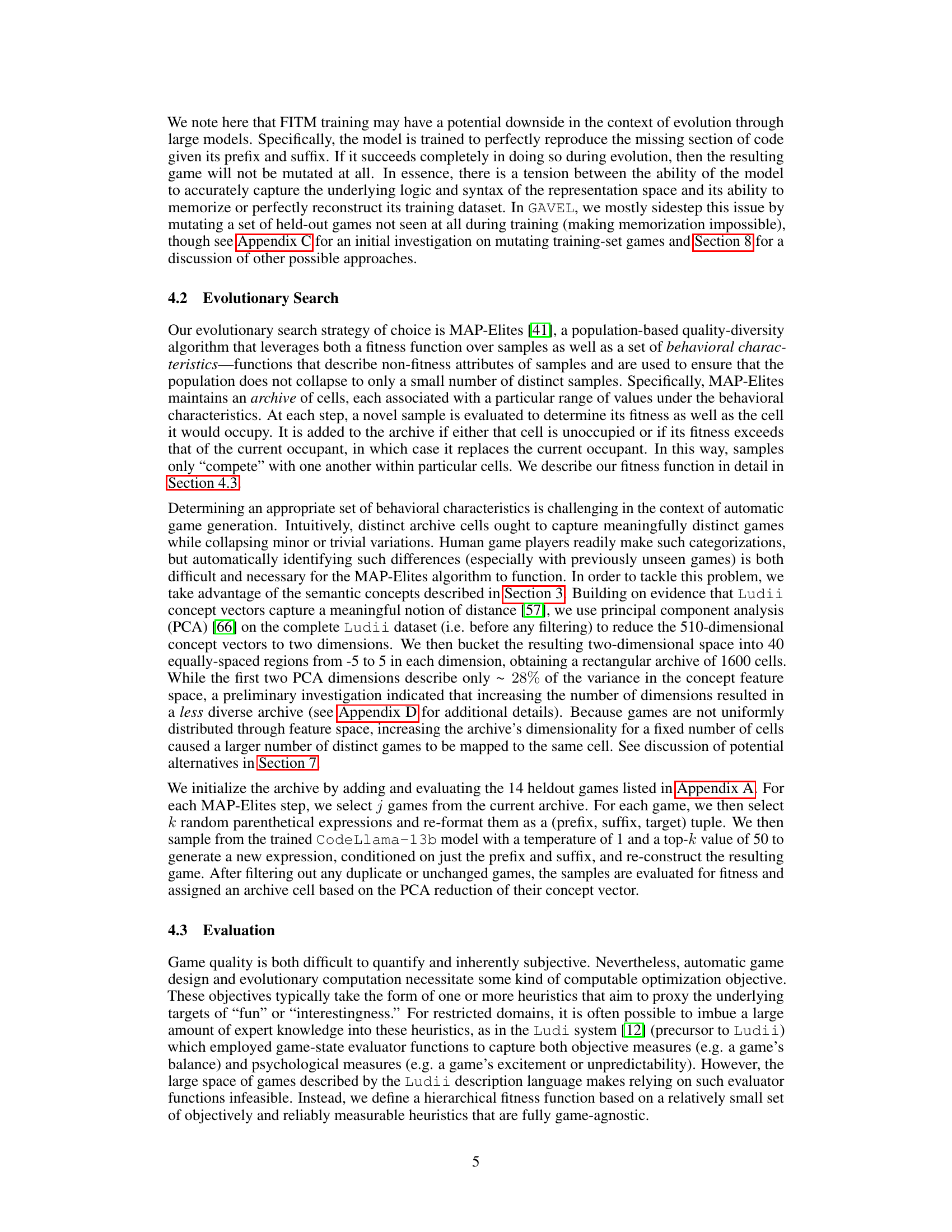

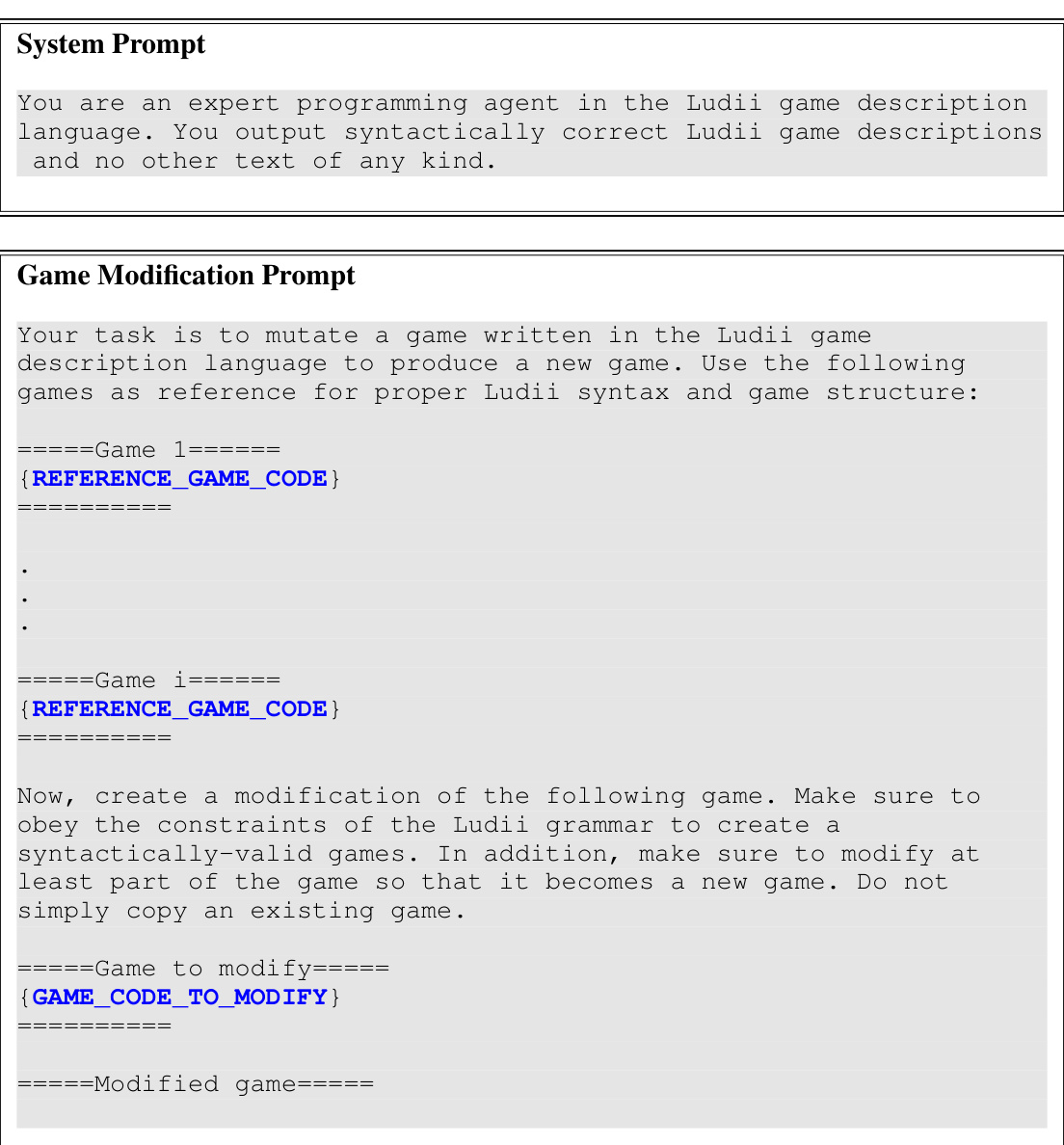

Ludii Language Model#

A hypothetical “Ludii Language Model” in the context of a research paper on automated game generation would likely be a large language model (LLM) specifically trained on the Ludii game description language (L-GDL). This LLM would serve as a core component of the game generation pipeline, capable of intelligently mutating and recombining game rules represented in L-GDL. The training process would likely involve a fill-in-the-middle objective to encourage generation of plausible rule modifications rather than complete regeneration. Its performance would be crucial to the success of the automated game generation system. The model’s ability to capture the nuances and structure of L-GDL would directly influence the quality and novelty of the generated games, making its design, training, and evaluation a critical focus of the research.

MAP-Elites Algorithm#

The MAP-Elites algorithm is a powerful quality-diversity optimization strategy particularly well-suited for complex, high-dimensional search spaces like those encountered in game design. Its core strength lies in its ability to simultaneously optimize for high fitness and diversity of solutions. Unlike traditional algorithms that focus solely on finding the single best solution, MAP-Elites maintains a diverse archive of solutions, each occupying a unique niche defined by a set of behavioral characteristics. This ensures that the resulting solutions aren’t just highly fit, but also meaningfully different from one another, leading to a more creative and robust set of outcomes. In the context of game generation, this translates to a wider variety of interesting and playable games, avoiding the pitfall of converging on a limited set of similar game mechanics. The use of PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the behavioral characteristics is a crucial step, enabling efficient exploration of the high-dimensional space of potential games. However, challenges remain in defining appropriate behavioral characteristics and handling the tradeoff between diversity and computational cost.

Game Novelty Metrics#

Defining and measuring game novelty is crucial for evaluating the success of automated game generation systems. Simple metrics like counting unique game mechanics or comparing rule sets against a database of existing games might fall short. A robust approach needs a multi-faceted evaluation, combining quantitative metrics (e.g., statistical measures of rule set similarity, feature vector distances in a semantic space of game properties) with qualitative assessments. Human evaluation becomes important here, judging playability, engagement, and overall originality through playtesting. The choice of metrics will also significantly depend on the specific game representation used, impacting the scope of novelty that can be measured. For example, abstract representations focused on high-level game properties may not capture novelty in intricate details of specific mechanics or visual elements. Therefore, a combination of automated analysis and human judgment is likely necessary to provide a reliable and comprehensive assessment of game novelty, acknowledging the inherent subjective nature of the ’novel’ and ‘interesting’ properties of a game.

Future of Game AI#

The future of Game AI is incredibly promising, with several key areas ripe for development. Large language models (LLMs) show immense potential for generating game content, rules, and even entire game designs. However, challenges remain such as controlling the creativity of LLMs, ensuring game balance, and evaluating the quality and playability of automatically generated games. Evolutionary computation will continue to be a valuable tool for optimizing game parameters and creating diverse game designs. Quality diversity algorithms are crucial for exploring the vast space of potential games and ensuring a rich variety of experiences. Addressing issues of algorithmic bias and promoting fairness in game AI will be essential to avoid unintended societal impacts. Future development will likely focus on integrating LLMs, evolutionary algorithms, and human feedback to generate games that are not only playable and interesting but also ethical and engaging. Human-in-the-loop systems, where human designers collaborate with AI, will probably become more common. This approach leverages the strengths of both human creativity and computational efficiency.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the GAVEL system’s architecture. The left side shows how a dataset of games in the Ludii language is processed to train a code large language model. This model learns to fill in missing parts of game rule expressions. The right side shows how this trained model is used within an evolutionary algorithm (MAP-Elites) to generate new games. The fitness of these games, along with their novelty (as measured by Ludii concepts), guides the evolutionary process.

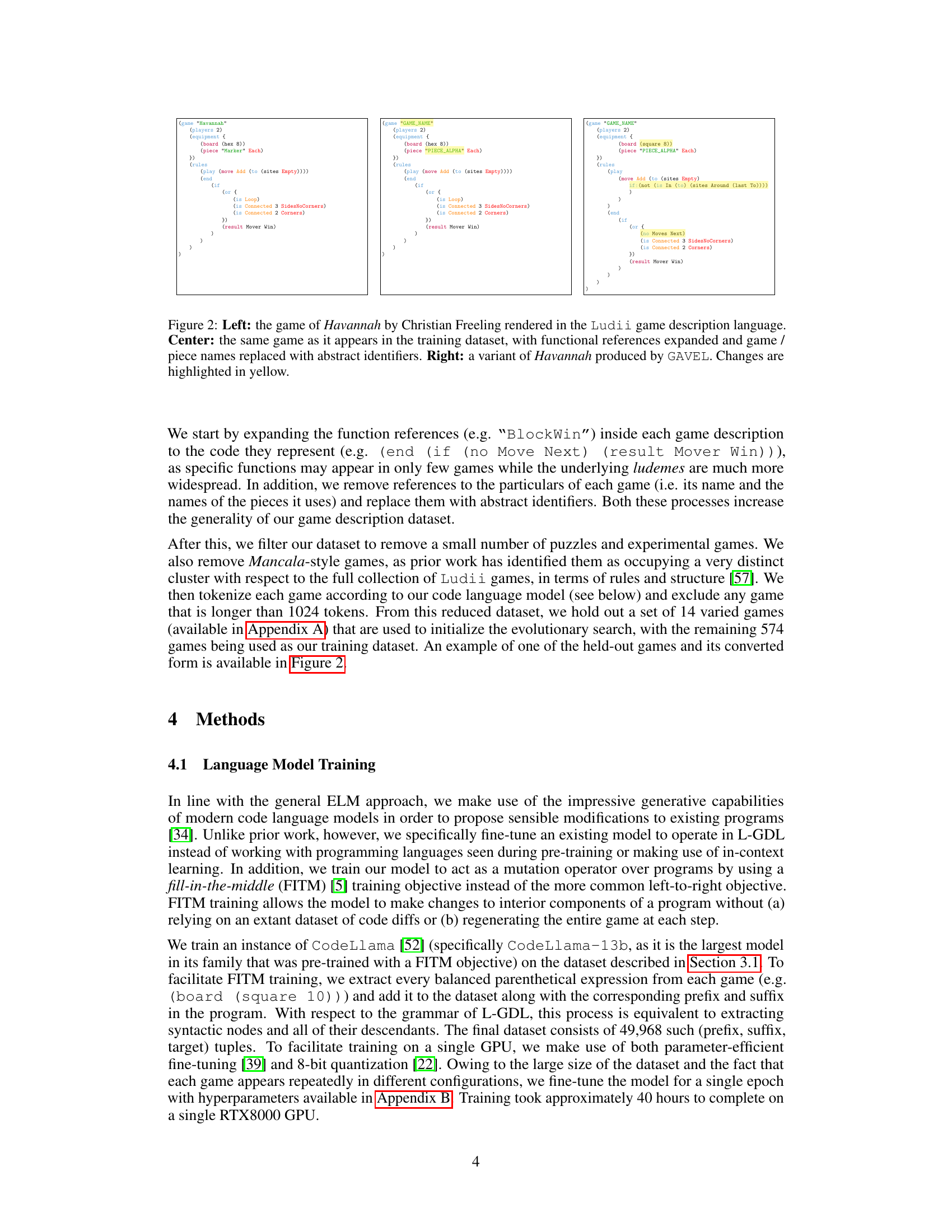

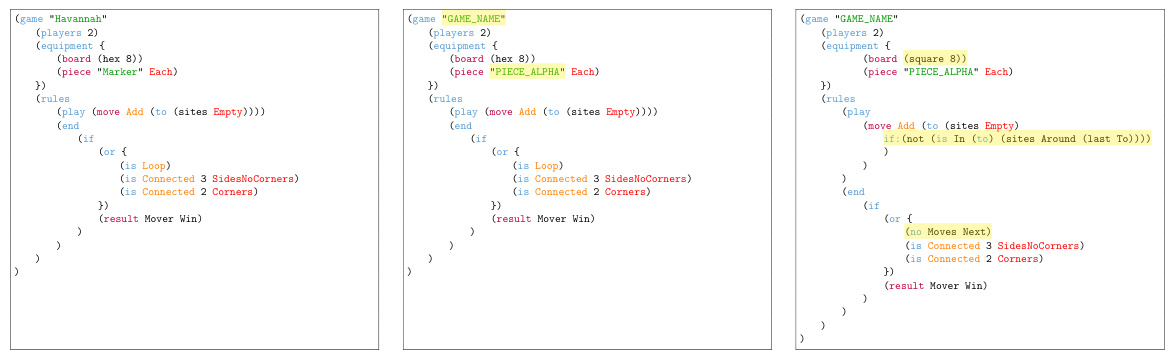

This figure shows three versions of the game Havannah. The leftmost image displays the original game in Ludii’s game description language. The middle image shows the same game but with function references expanded and game/piece names replaced with abstract identifiers to increase generality for the training dataset. The rightmost image is a variant of Havannah generated by GAVEL, highlighting the changes made by the model.

This figure shows the evolution of the game fitness over 500 generations using the GAVEL method. It starts with 14 initial games and generates 185 novel variations, with a significant portion meeting the minimum quality criteria. Notably, a subset of these games explores regions of the game space not covered by existing games in the Ludii dataset.

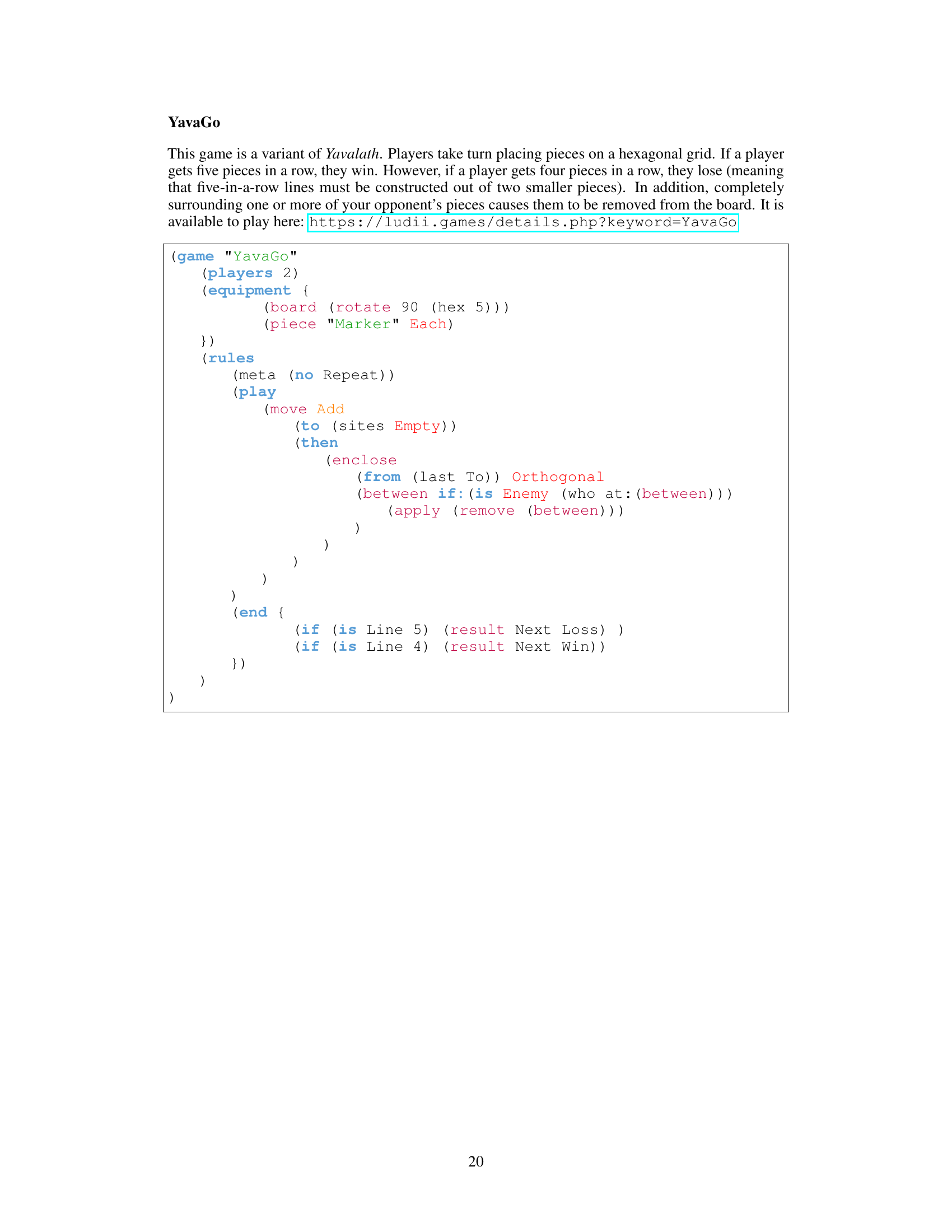

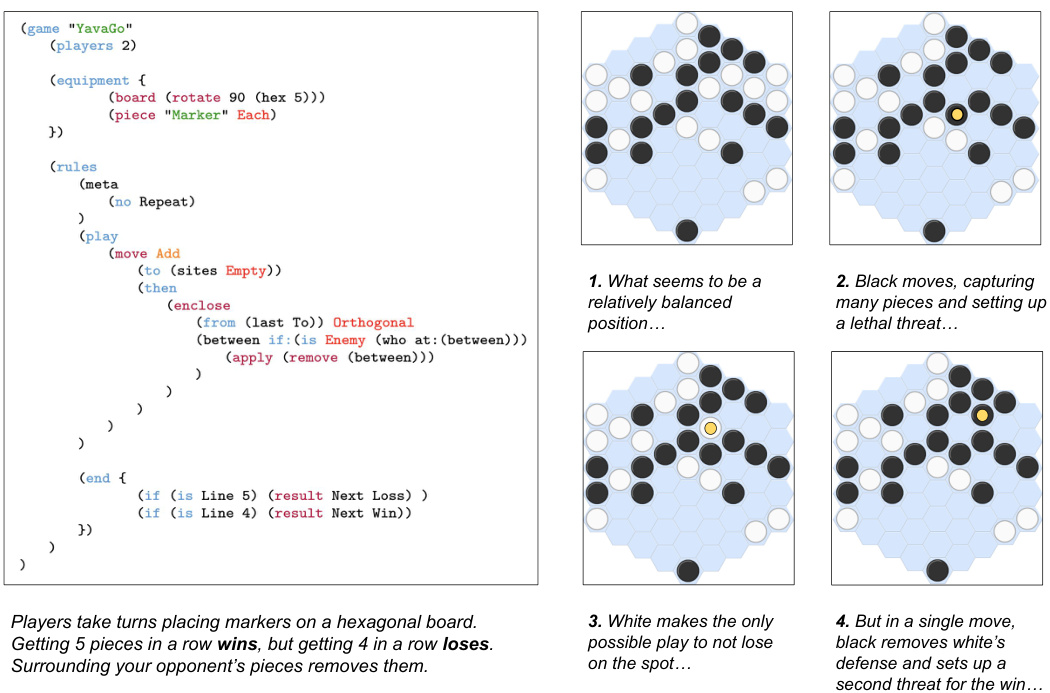

This figure shows an example of a game generated by the GAVEL system, illustrating gameplay between two Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) agents. The game combines mechanics from Yavalath (a game where players try to get n pieces in a row) and Go (which includes an enclosure mechanic where surrounding your opponent’s pieces removes them). The game demonstrates that GAVEL can create games with interesting and strategically complex situations.

The figure shows three versions of the game Havannah: the original game in Ludii game description language, the processed version used in training (abstract identifiers are used), and a modified version generated by GAVEL. The differences between the original and the GAVEL-generated version are highlighted in yellow.

This figure shows three versions of the game Havannah. The leftmost image displays the original game’s code. The middle image shows the same game after preprocessing for the training dataset, where functional references are expanded, and game and piece names are replaced with abstract identifiers to increase generality. The rightmost image presents a variant of Havannah generated by GAVEL, highlighting the changes introduced by the model in yellow.

This figure shows three versions of the game Havannah. The left shows the original game description in the Ludii language. The center shows the game after preprocessing for the training data, with functional references expanded and names replaced with abstract identifiers. The right shows a variant of the game generated by GAVEL, highlighting the changes made.

More on tables

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing mutations generated from training and validation datasets. It shows the proportion of mutations that are novel (not duplicates of original games), valid (compilable according to the Ludii grammar), and both novel and valid. The experiment was conducted using different sampling temperatures and top-k values.

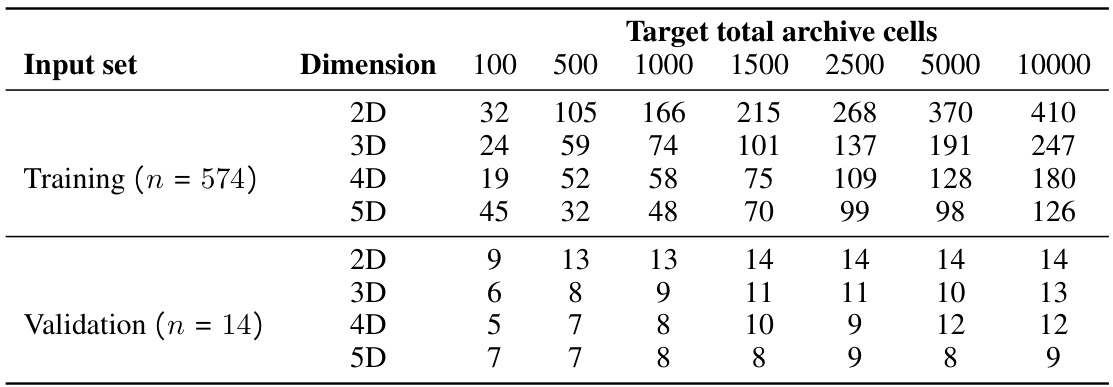

This table shows the result of an experiment to determine the optimal dimensionality and size of the archive used in the MAP-Elites algorithm. Different dimensionalities (2D, 3D, 4D, 5D) and target sizes (100, 500, 1000, 1500, 2500, 5000, 10000 cells) were tested, along with their impact on how many unique cells were occupied by the training and validation datasets. The results indicate that higher dimensionality leads to less unique cells being occupied for a fixed target archive size and a 2D archive with roughly 1500 cells provided a suitable balance.

This table shows the results of an experiment to determine how well a Centroidal Voronoi Tesselation (CVT) based archive can distinguish between games with varying numbers of cells. The experiment used 574 training games and 14 validation games from the Ludii dataset, and varied the total number of cells in the archive from 100 to 100000. The results show that even very large archives fail to distinguish between many of the games, collapsing them into a small number of unique cells.

Full paper#