TL;DR#

Unsupervised point cloud registration struggles with reliable optimization objectives, often relying on strong geometric assumptions or producing poor-quality pseudo-labels due to inadequate integration of low-level geometric and high-level contextual information. Existing methods often fail in outdoor scenarios with low overlap and density variations.

The proposed method, INTEGER, addresses these issues by incorporating high-level contextual information for reliable pseudo-label mining using a novel Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining module. It dynamically adapts a teacher model for each mini-batch, discovering robust pseudo-labels by considering both high-level features and low-level geometry. Furthermore, Anchor-Based Contrastive Learning and a Mixed-Density Student are used to enhance the feature space robustness and learn density-invariant features. Extensive experiments demonstrate INTEGER’s superior accuracy and generalizability compared to state-of-the-art methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents INTEGER, a novel unsupervised method for point cloud registration that significantly outperforms existing methods, especially in challenging outdoor scenarios with low overlap and density variations. This advance is crucial for autonomous driving and robotics, and opens new avenues for research in reliable pseudo-label mining and density-invariant feature learning.

Visual Insights#

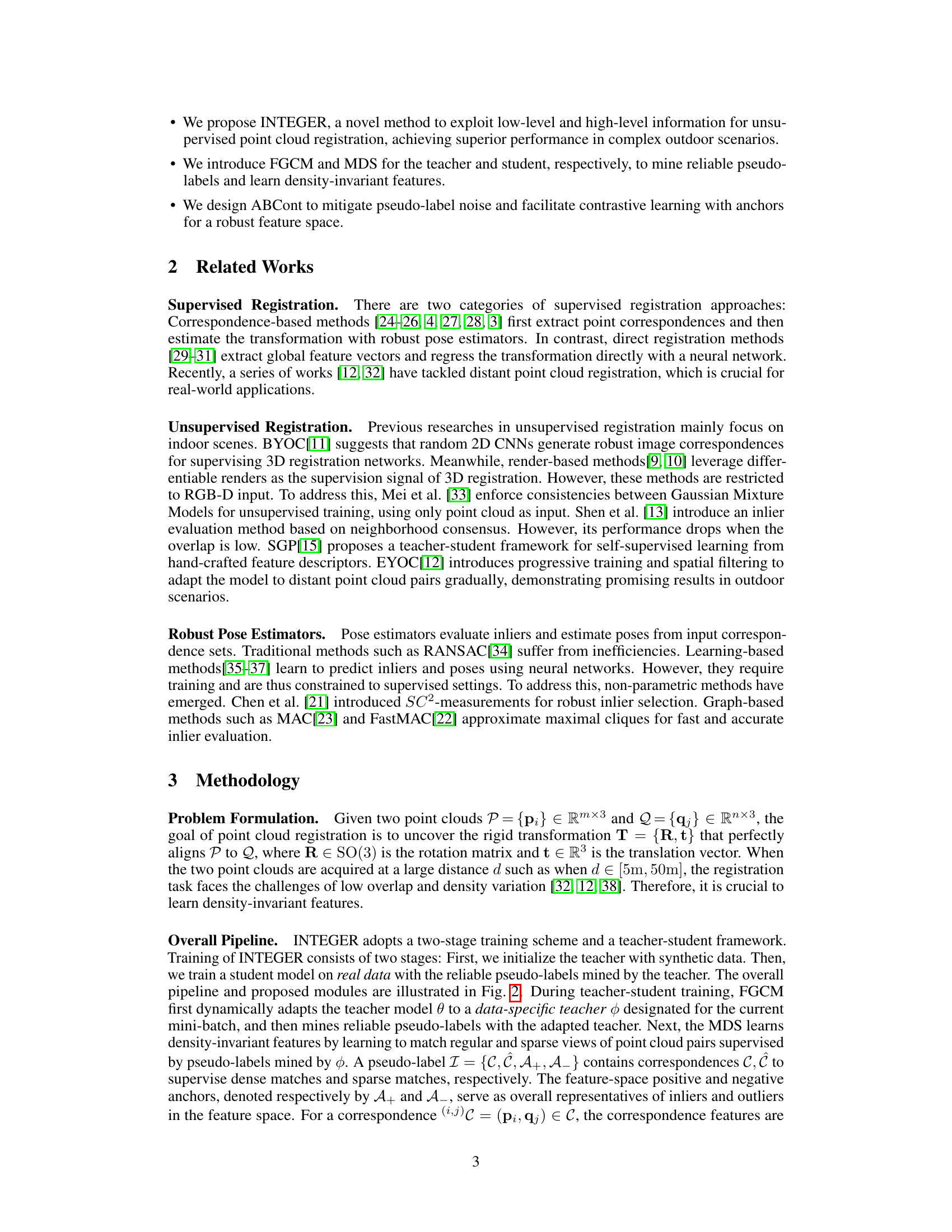

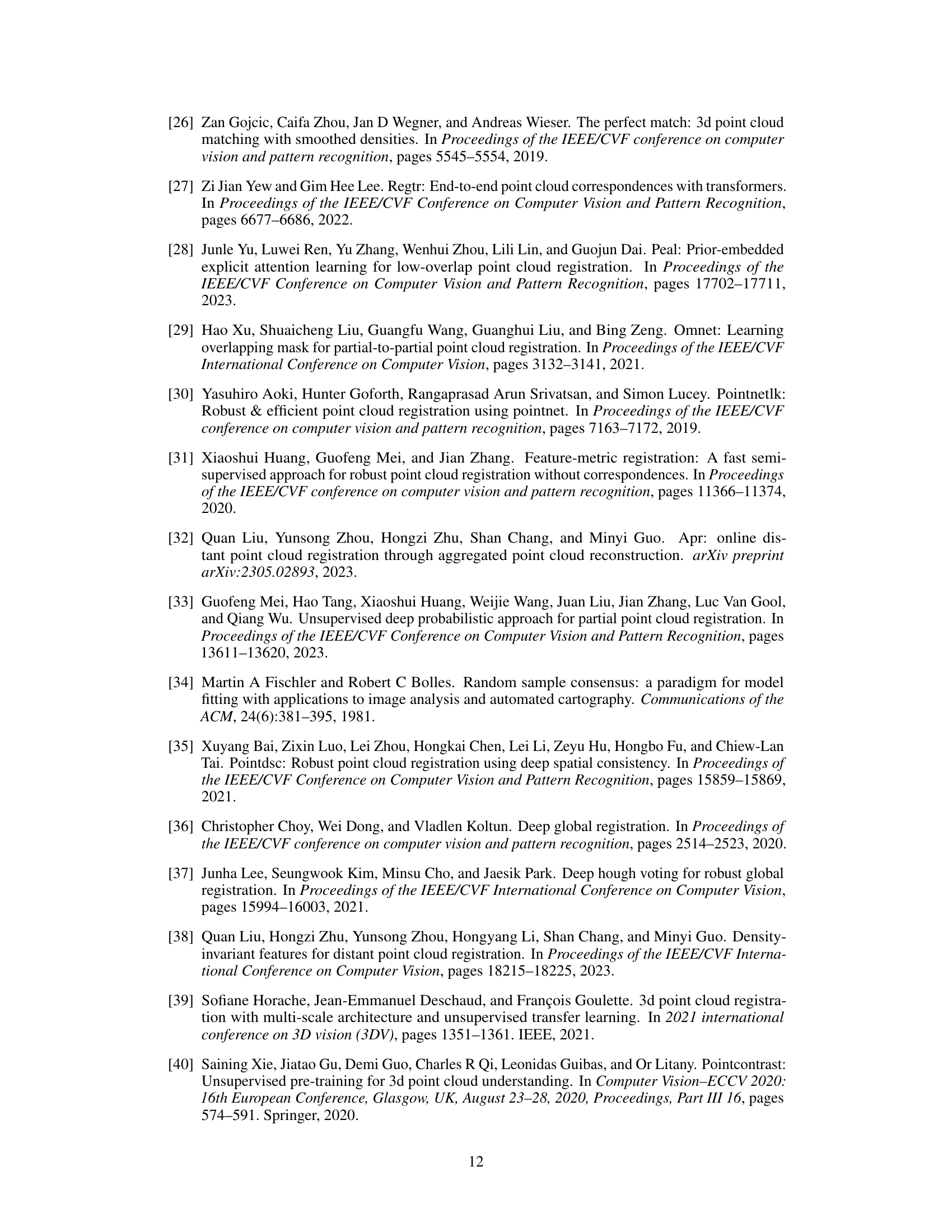

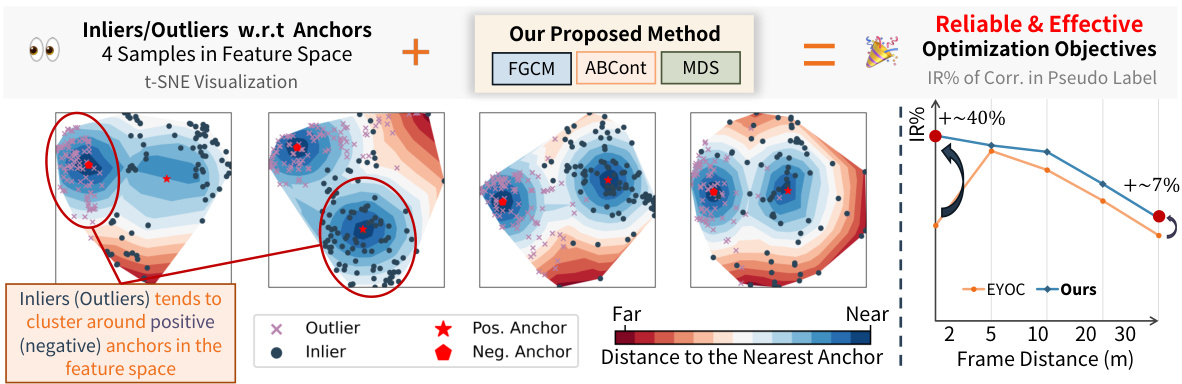

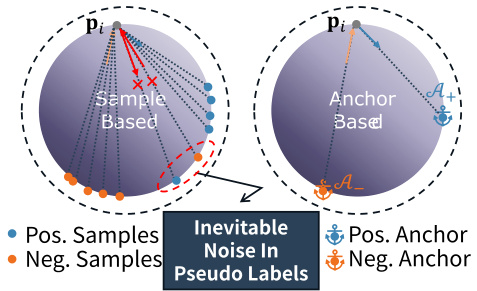

🔼 This figure demonstrates the core idea and performance of the proposed INTEGER method. The left panel shows that new inliers tend to cluster around positive anchors representing existing inliers in the feature space, while outliers cluster around negative anchors. This observation motivates the Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining (FGCM) module. The right panel compares the performance of INTEGER against the state-of-the-art EYOC method in terms of Inlier Ratio (IR%) within the pseudo-labels, showing a significant improvement of INTEGER, especially at larger distances.

read the caption

Figure 1: (1) Motivation: new inliers (outliers) tend to cluster around latent positive (negative) anchors that represent existing inliers (outliers) in the feature space, respectively. (2) Performance: pseudo-labels from INTEGER are more robust and accurate than the previous state-of-the-art EYOC[12].

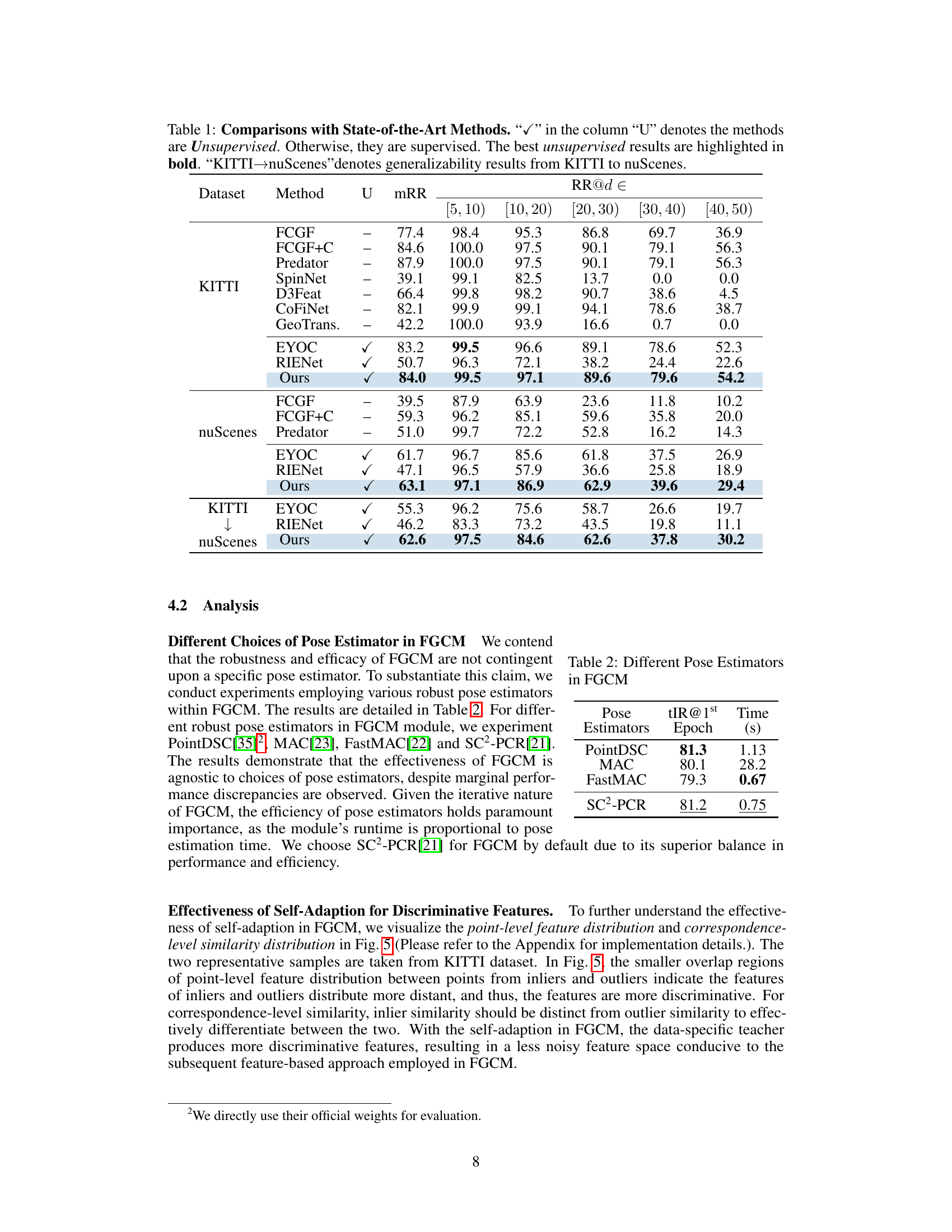

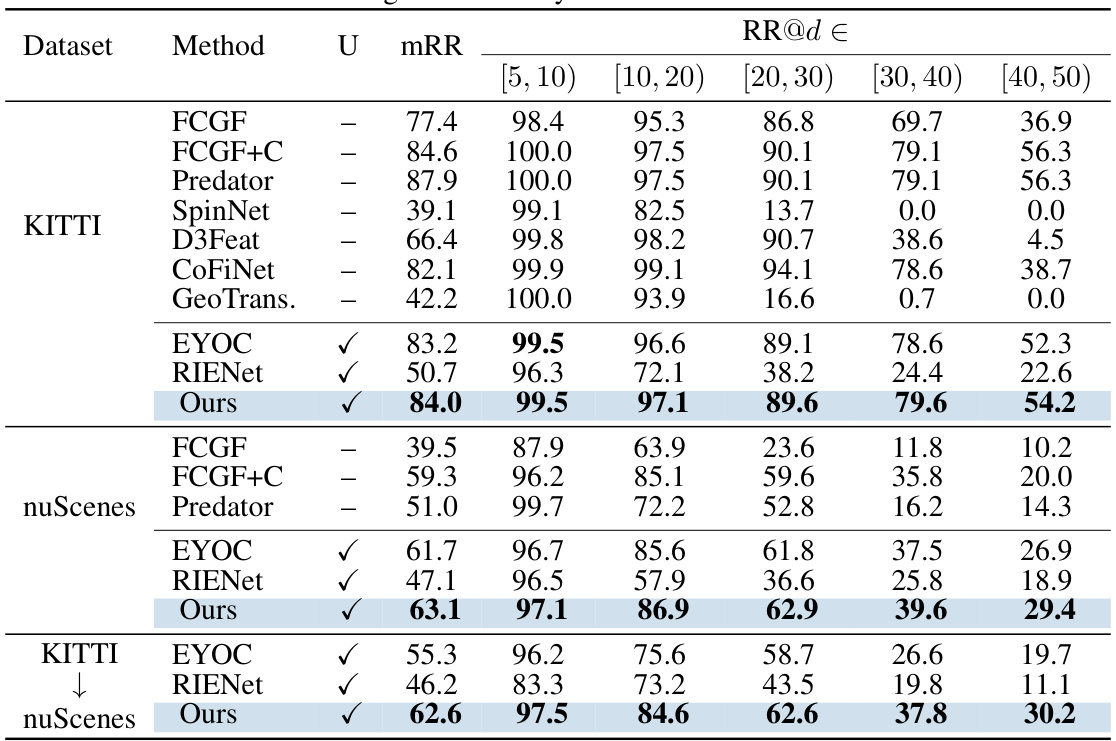

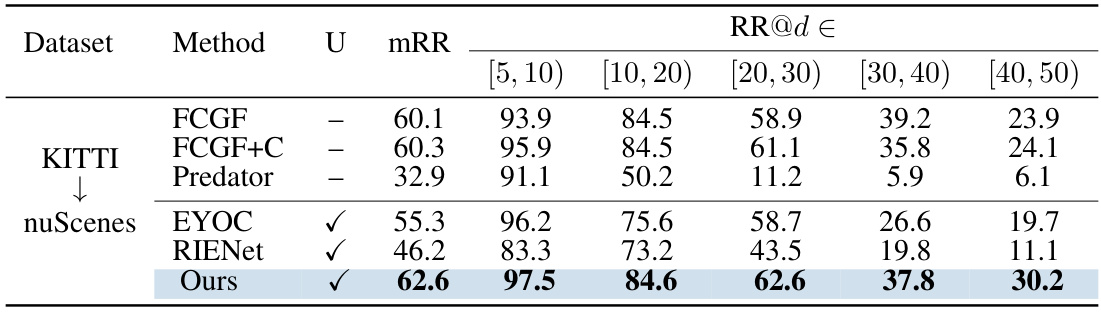

🔼 This table compares the proposed INTEGER method against various state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for point cloud registration, both supervised and unsupervised, on the KITTI and nuScenes datasets. The metrics used are mRR (mean Registration Recall), and RR@[d1, d2) (Registration Recall within specific distance ranges). The table also shows the generalizability of the model trained on KITTI dataset when applied to the nuScenes dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparisons with State-of-the-Art Methods. “√” in the column “U” denotes the methods are Unsupervised. Otherwise, they are supervised. The best unsupervised results are highlighted in bold. 'KITTI→nuScenes'denotes generalizability results from KITTI to nuScenes.

In-depth insights#

Feature-Geometry Mining#

Feature-Geometry Mining represents a novel approach to unsupervised point cloud registration by synergistically leveraging both low-level geometric cues and high-level feature representations. The core idea is that inlier correspondences tend to cluster around positive anchors in feature space, while outliers cluster around negative anchors. This observation motivates a dynamic adaptation of a teacher model for each mini-batch, enabling the identification of reliable pseudo-labels. This process dynamically adapts to data characteristics, enhancing the robustness of pseudo-label generation compared to methods solely relying on geometric information. By integrating contextual information, the method aims to achieve more reliable optimization objectives, thereby improving the overall accuracy and generalizability of the registration process. The effectiveness hinges on the ability to disentangle inliers and outliers in feature space, a task aided by the proposed anchor-based contrastive learning. This clever integration of feature and geometric information promises to address a critical challenge in unsupervised point cloud registration, specifically the difficulty of establishing dependable optimization objectives in the absence of ground truth pose data.

Anchor-Based Contrastive Learning#

Anchor-based contrastive learning is a technique that leverages anchor points to improve the effectiveness of contrastive learning, especially in scenarios with noisy or incomplete data. Instead of directly comparing all data points, anchor points, which represent the central tendency of clusters of similar data, act as proxies for the inliers/outliers. This method is particularly useful in point cloud registration because it helps to overcome the challenge of low overlap and density variation in outdoor scenes. By using anchors, the model can focus on learning discriminative features that distinguish inliers from outliers even when there is a significant amount of noise in the data. This technique allows for a more robust and reliable unsupervised training, reducing reliance on perfect or high-quality pseudo-labels, and boosting generalization capabilities. The anchor-based approach provides a clear and efficient optimization objective by establishing robust, data-driven, and reliable pseudo-labels for the student model to learn from. Therefore, anchor-based contrastive learning improves model robustness and efficiency in challenging scenarios like point cloud registration.

Density-Invariant Features#

The concept of “Density-Invariant Features” addresses a crucial challenge in point cloud registration, especially in outdoor environments: the varying density of point clouds at different distances from the sensor. Traditional methods often struggle with this, as feature extraction and matching are significantly affected by density variations. Density-invariant features aim to create representations that are robust to these variations, allowing for reliable registration even when point cloud density differs significantly between the scenes. This is achieved by either modifying existing feature extraction methods to be less sensitive to density or by learning features that explicitly encode spatial context in addition to point attributes. Effective strategies might involve downsampling higher-density regions, using features that are robust to data sparsity or learning density-invariant representations through dedicated network architectures or loss functions. Successful implementation of density-invariant features substantially improves the accuracy and generalizability of point cloud registration algorithms, particularly in challenging outdoor settings with significant density changes. This makes it a significant area of research in autonomous driving and robotics.

Unsupervised Registration#

Unsupervised point cloud registration methods aim to overcome the limitations of supervised approaches by eliminating the need for costly and time-consuming pose annotations. Existing methods often rely on overly simplistic geometric assumptions or struggle with the integration of low-level geometric and high-level contextual features, leading to unreliable optimization objectives. A key challenge lies in the effective mining of pseudo-labels for unsupervised training. Several strategies have emerged to address this, such as leveraging photometric and depth consistency or optimizing for global alignment and neighborhood consensus. However, these methods often struggle with real-world scenarios, including large-scale outdoor datasets characterized by low overlap and density variations. Future research will likely focus on more robust pseudo-label generation techniques and better fusion of multi-level information for improved accuracy and generalizability in challenging outdoor environments. Exploring new optimization objectives that are robust to noise and outliers while still effectively capturing the underlying geometry is also crucial.

Generalizability Challenges#

Generalizability in machine learning models, especially those applied to point cloud data, presents significant challenges. A model trained on one dataset might fail to perform well on another due to differences in data characteristics like sensor type, environment, density, and noise levels. These variations create a mismatch between the training distribution and the real-world deployment conditions, leading to poor generalization. Achieving robust generalizability requires careful consideration of these factors during model design and training, including the use of data augmentation techniques to broaden the training distribution, the development of domain adaptation methods to bridge the gap between datasets, and the design of invariance properties to make the model less sensitive to irrelevant variations in the input data. Careful evaluation across diverse and representative datasets is crucial to ensure a model’s generalizability and practical applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

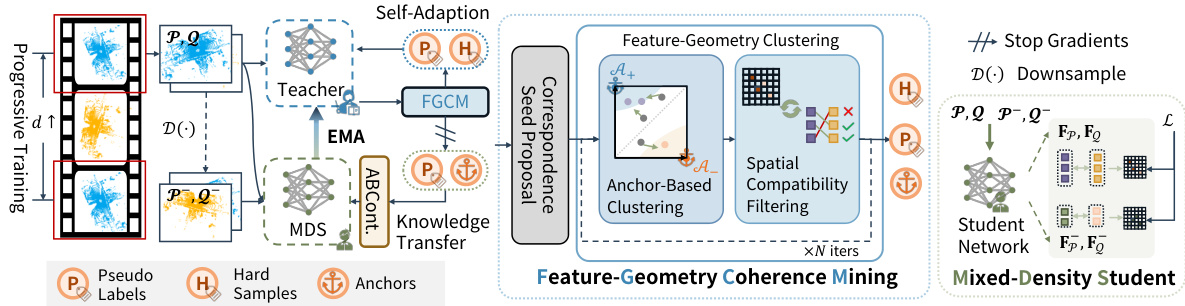

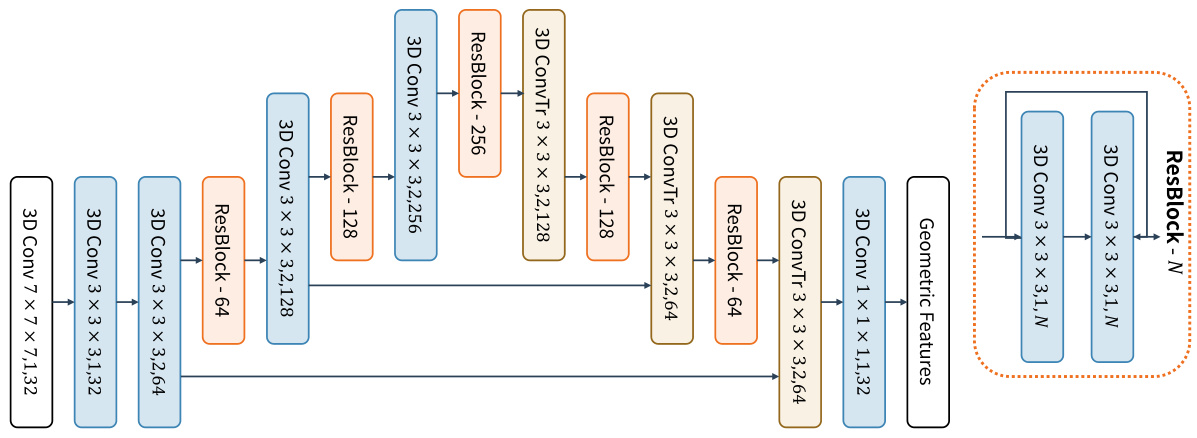

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the INTEGER method for unsupervised point cloud registration. It shows the two-stage training process with a teacher-student framework. The teacher model is first adapted to each mini-batch of data using Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining (FGCM) module, which produces reliable pseudo-labels. Then, the student model learns density-invariant features from these pseudo-labels using a Mixed-Density Student (MDS) module. Anchor-Based Contrastive Learning (ABCont) is used to facilitate contrastive learning with anchors, which helps to improve the robustness and accuracy of feature learning. The progressive training strategy is also shown, where the model is gradually adapted to handle pairs of point clouds with increasing distances.

read the caption

Figure 2: The Overall Pipeline. FGCM(Sec. 3.2) first adapt the teacher model to a data-specific teacher for the current mini-batch, and then mine reliable pseudo-labels. Next, MDS(Sec. 3.4) learns density-invariant features from pseudo-labels. ABCont(Sec. 3.3) is applied for adapting the teacher and transferring knowledge to the student in the feature space.

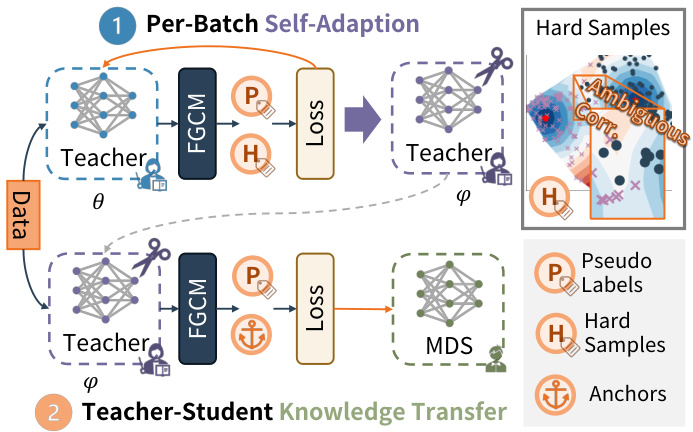

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the INTEGER method for unsupervised point cloud registration. It shows a two-stage teacher-student training framework. The first stage involves FGCM (Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining) adapting the teacher model to each mini-batch of data and mining pseudo-labels. The second stage uses these pseudo-labels to train the Mixed-Density Student (MDS) model, which learns density-invariant features. Anchor-Based Contrastive Learning (ABCont) is applied throughout to enhance the robustness and transferability of features from teacher to student. The figure highlights the key modules and information flow within the framework.

read the caption

Figure 2: The Overall Pipeline. FGCM(Sec. 3.2) first adapt the teacher model to a data-specific teacher for the current mini-batch, and then mine reliable pseudo-labels. Next, MDS(Sec. 3.4) learns density-invariant features from pseudo-labels. ABCont(Sec. 3.3) is applied for adapting the teacher and transferring knowledge to the student in the feature space.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core concept of Anchor-Based Contrastive Learning (ABCont). The left panel shows a sample-based contrastive learning approach where many pairwise relationships are formed between positive and negative samples, making it sensitive to noise in pseudo-labels. The right panel demonstrates ABCont, which uses anchors to represent inliers and outliers. By leveraging anchors, ABCont reduces the number of pairwise relationships, improving robustness against noisy pseudo-labels and leading to more effective contrastive learning. The figure highlights the benefits of using anchors for better distinguishing between positive and negative samples in the presence of noise.

read the caption

Figure 4: Toy Example for ABCont. Anchor-based methods introduce fewer pairwise relationships and are robust against inevitable label noise.

🔼 This figure visualizes the impact of the Per-Batch Self-Adaptation module within the Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining (FGCM) component of the INTEGER algorithm. It displays the distribution of features for inliers and outliers, both before and after the self-adaptation process. The top row shows the distributions before self-adaptation, revealing significant overlap between inliers and outliers in both feature space and similarity distribution. The bottom row shows that after self-adaptation, the distributions are more distinct, indicating that the process effectively enhances feature discriminability, leading to improved performance in identifying true correspondences.

read the caption

Figure 5: Before v.s. After Self-Adaption in FGCM: Point-wise Feature & Correspondence-wise Similarity Distribution indicate that the self-adaption results in more discriminative features.

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the INTEGER method for unsupervised point cloud registration. It shows the two-stage training process involving a teacher and a student network. The Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining (FGCM) module dynamically adapts the teacher to each mini-batch, mining reliable pseudo-labels. These pseudo-labels are then used to train the Mixed-Density Student (MDS), which learns density-invariant features. Anchor-Based Contrastive Learning (ABCont) facilitates contrastive learning using anchors, enabling robust feature space learning and knowledge transfer from teacher to student.

read the caption

Figure 2: The Overall Pipeline. FGCM(Sec. 3.2) first adapt the teacher model to a data-specific teacher for the current mini-batch, and then mine reliable pseudo-labels. Next, MDS(Sec. 3.4) learns density-invariant features from pseudo-labels. ABCont(Sec. 3.3) is applied for adapting the teacher and transferring knowledge to the student in the feature space.

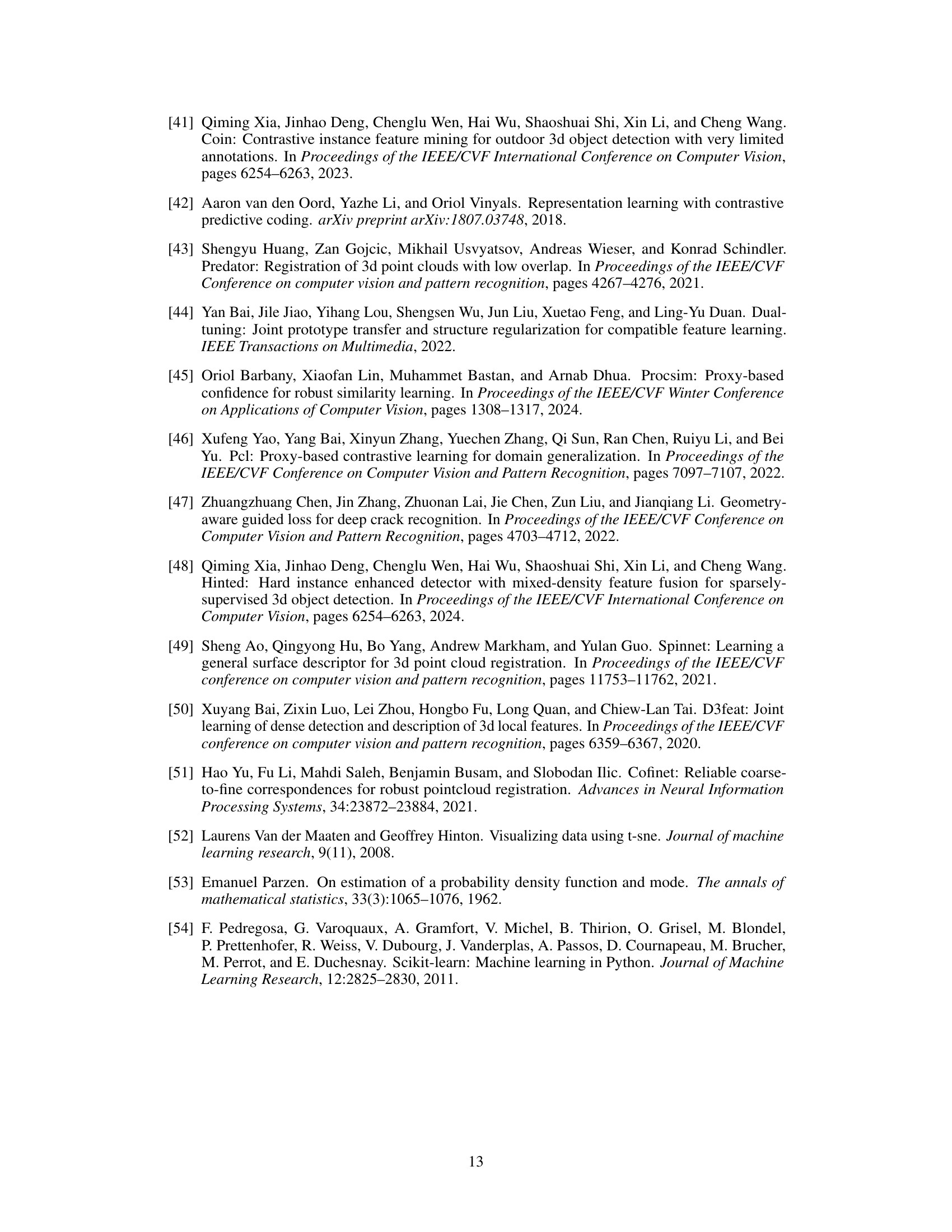

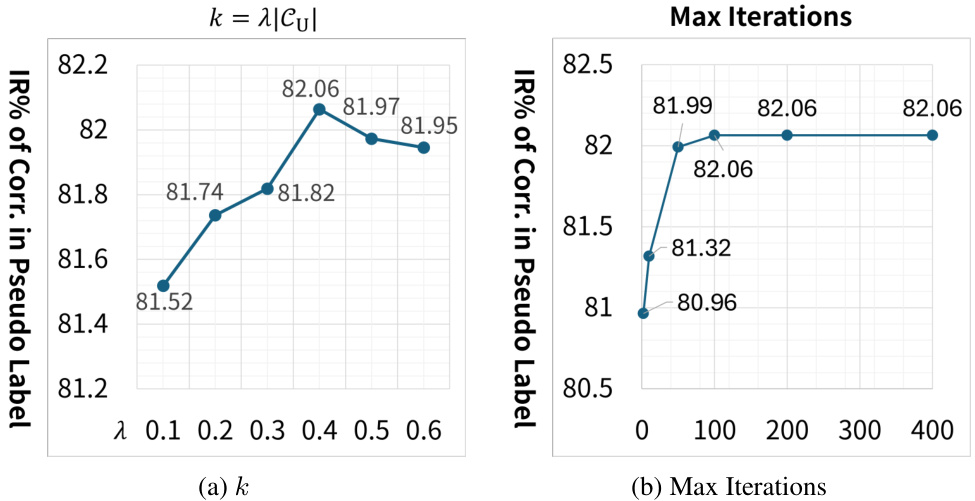

🔼 This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of two hyperparameters used in the Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining (FGCM) module: the number of putative correspondences (k) to enlarge the initial set of correspondences (Ci-1) and the maximum number of iterations. The x-axes represent different values of each hyperparameter, while the y-axes show the inlier ratio (IR) percentage in the pseudo-labels. The plots indicate that the performance of the FGCM module is relatively stable across a range of values for both hyperparameters, suggesting robustness to hyperparameter tuning. For optimal performance, k = 0.4|Cu| and max iterations = 100 were chosen.

read the caption

Figure 7: Sensitivity of hyperparameters in FGCM module.

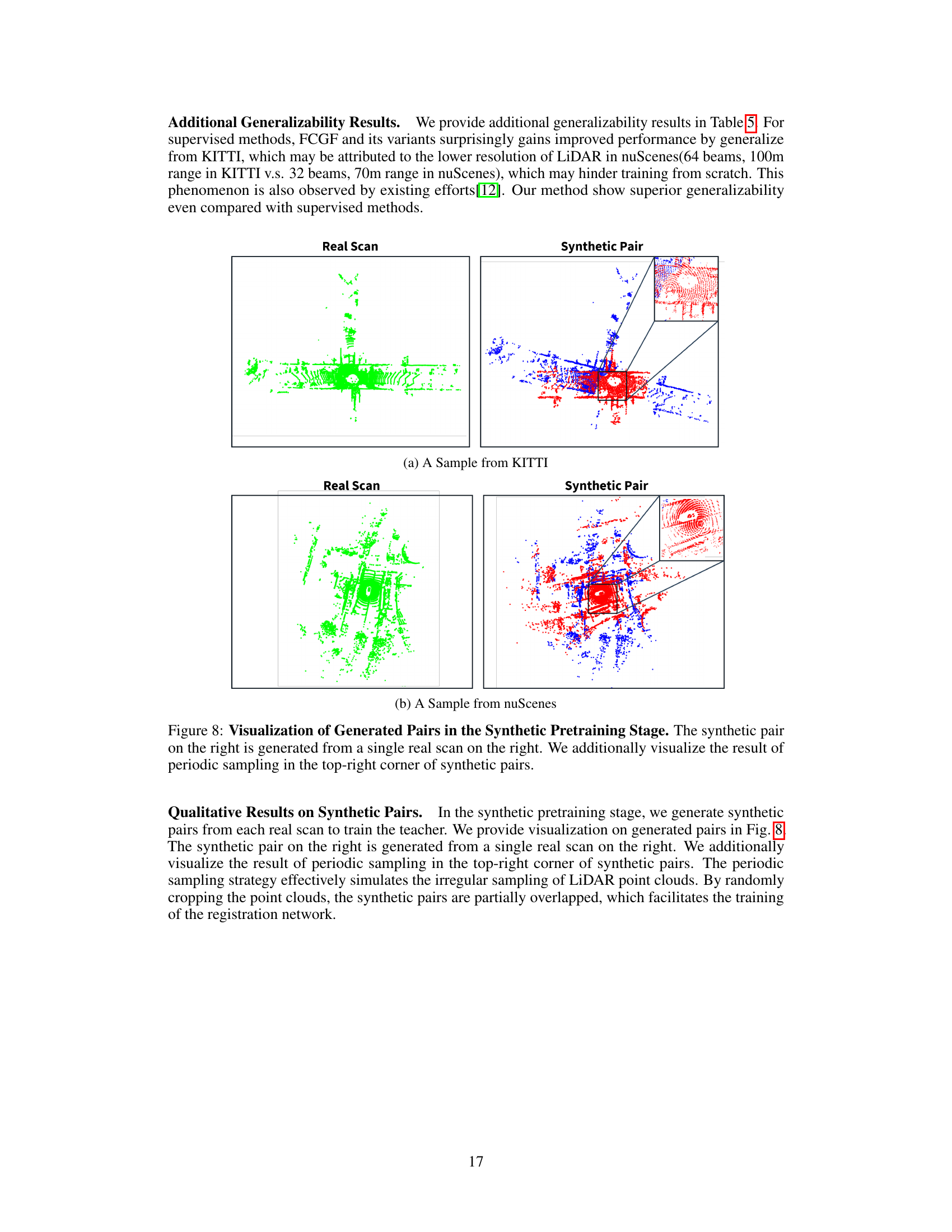

🔼 This figure shows examples of synthetic pairs generated for synthetic teacher pretraining. The left side displays a real LiDAR scan. The right side shows a synthetic pair generated from that scan, illustrating how the method creates partially overlapping point cloud pairs to simulate the irregularities of real-world LiDAR data acquisition. A zoomed-in section highlights the periodic sampling that simulates the sparsity and inconsistencies typical of real LiDAR data.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualization of Generated Pairs in the Synthetic Pretraining Stage. The synthetic pair on the right is generated from a single real scan on the right. We additionally visualize the result of periodic sampling in the top-right corner of synthetic pairs.

More on tables

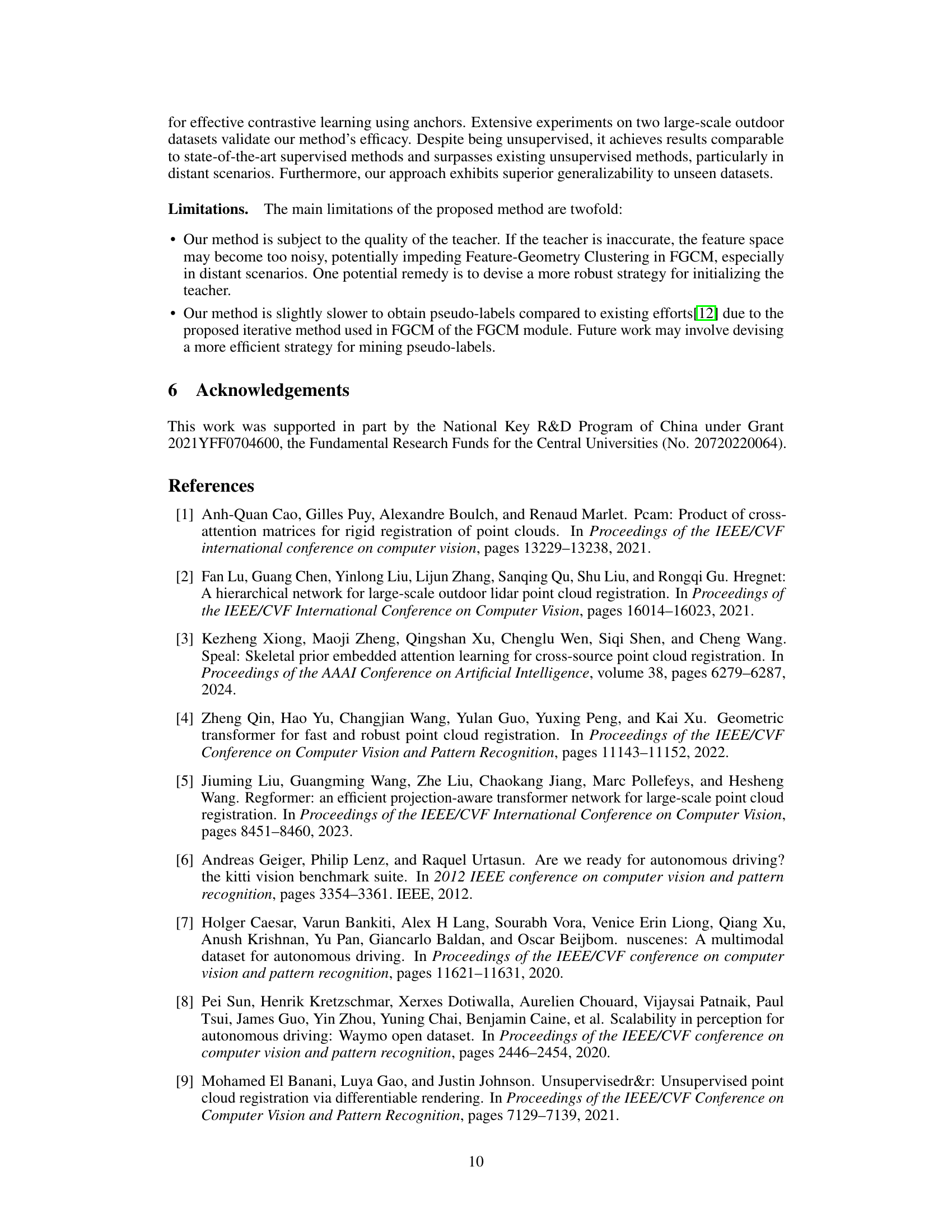

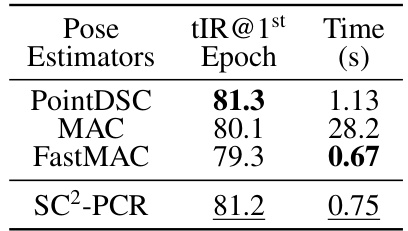

🔼 This table compares the performance of different pose estimators used within the Feature-Geometry Coherence Mining (FGCM) module. The metrics shown are the Inlier Ratio (tIR) at the first epoch and the time taken for the pose estimation. The results demonstrate that the effectiveness of FGCM is largely independent of the choice of pose estimator, although there are minor differences in performance and processing time. SC2-PCR shows a good balance of accuracy and speed.

read the caption

Table 2: Different Pose Estimators in FGCM

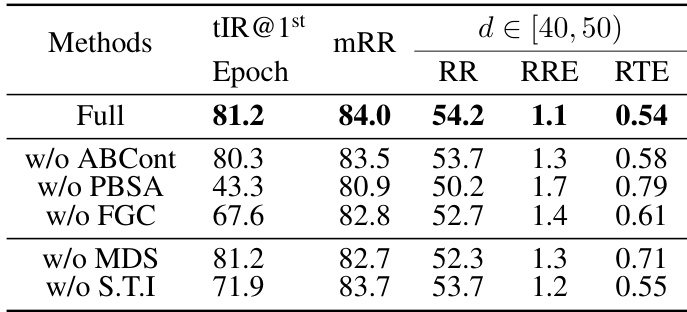

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results for the INTEGER method. It shows the impact of removing different components of the model (ABCont, PBSA, FGC, MDS, and S.T.I) on the performance metrics (mRR, RR, RRE, RTE) specifically for distant point cloud pairs (d ∈ [40, 50]). The tIR@1st Epoch column indicates the inlier ratio at the first epoch of training, showing the quality of pseudo-labels generated by the teacher. The results highlight the contribution of each component to the overall performance of the method.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation Study of INTEGER. S.T.I denotes synthetic teacher initialization. PBSA and FGC denote Per-Batch Self-Adaption and Feature-Geometry Clustering, respectively

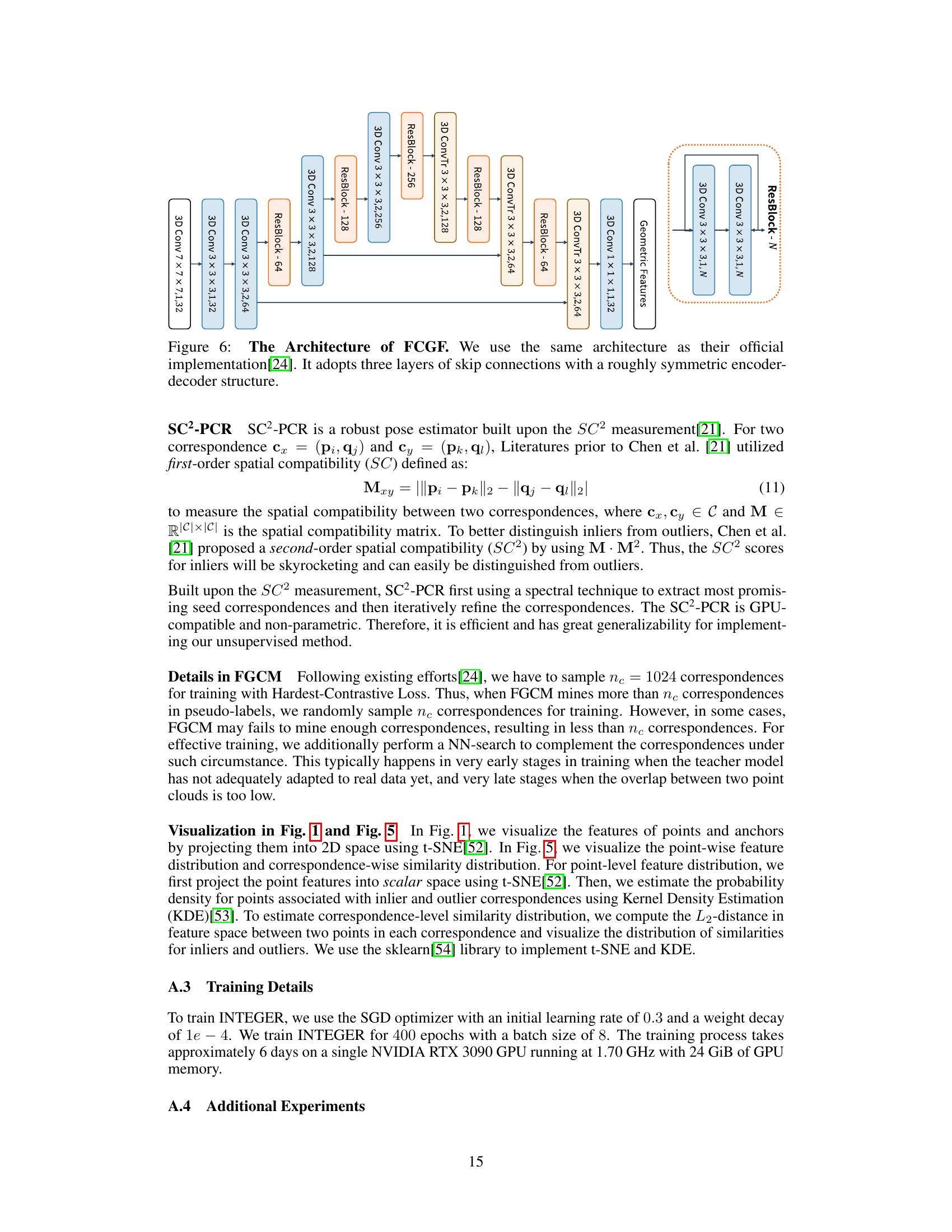

🔼 This table shows the performance of INTEGER when combined with different registration networks (FCGF and Predator). It demonstrates the adaptability of INTEGER across various network architectures by providing mRR (mean Registration Recall) and RR@[distance range] (Registration Recall at specific distance ranges). The results highlight INTEGER’s robustness and adaptability, while also showing some performance differences when used with more complex networks like Predator.

read the caption

Table 4: Adaptability of INTEGER for Different Registration Networks

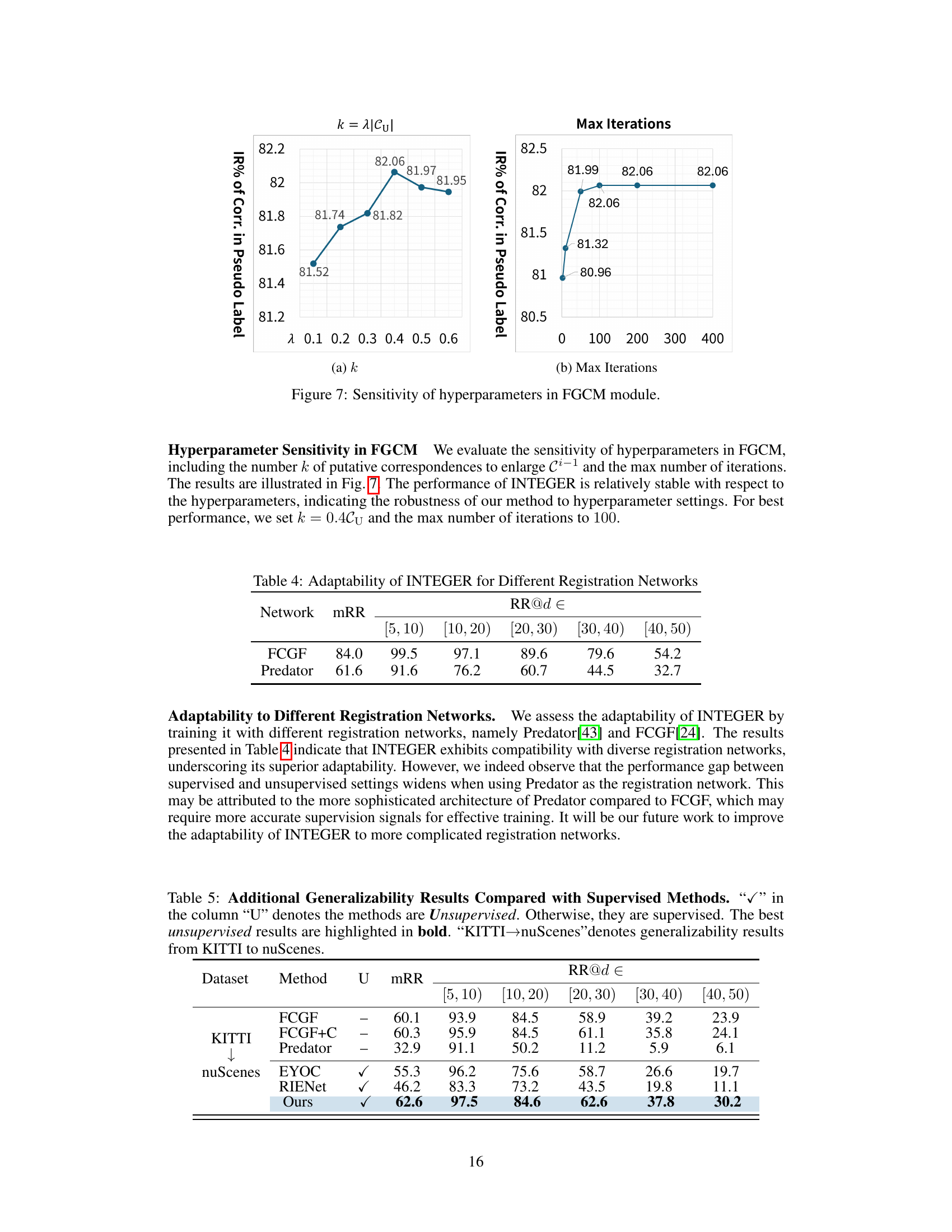

🔼 This table compares the proposed INTEGER method with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for point cloud registration on the KITTI and nuScenes datasets. It shows the performance (mRR and RR@d) of both supervised and unsupervised methods, highlighting INTEGER’s competitive performance, particularly in the unsupervised category and its generalizability when transferring knowledge from KITTI to nuScenes.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparisons with State-of-the-Art Methods. “√” in the column “U” denotes the methods are Unsupervised. Otherwise, they are supervised. The best unsupervised results are highlighted in bold. 'KITTI→nuScenes'denotes generalizability results from KITTI to nuScenes.

Full paper#